Study on the Mechanism and Modification of Carbon-Based Materials for Pollutant Treatment

Highlights

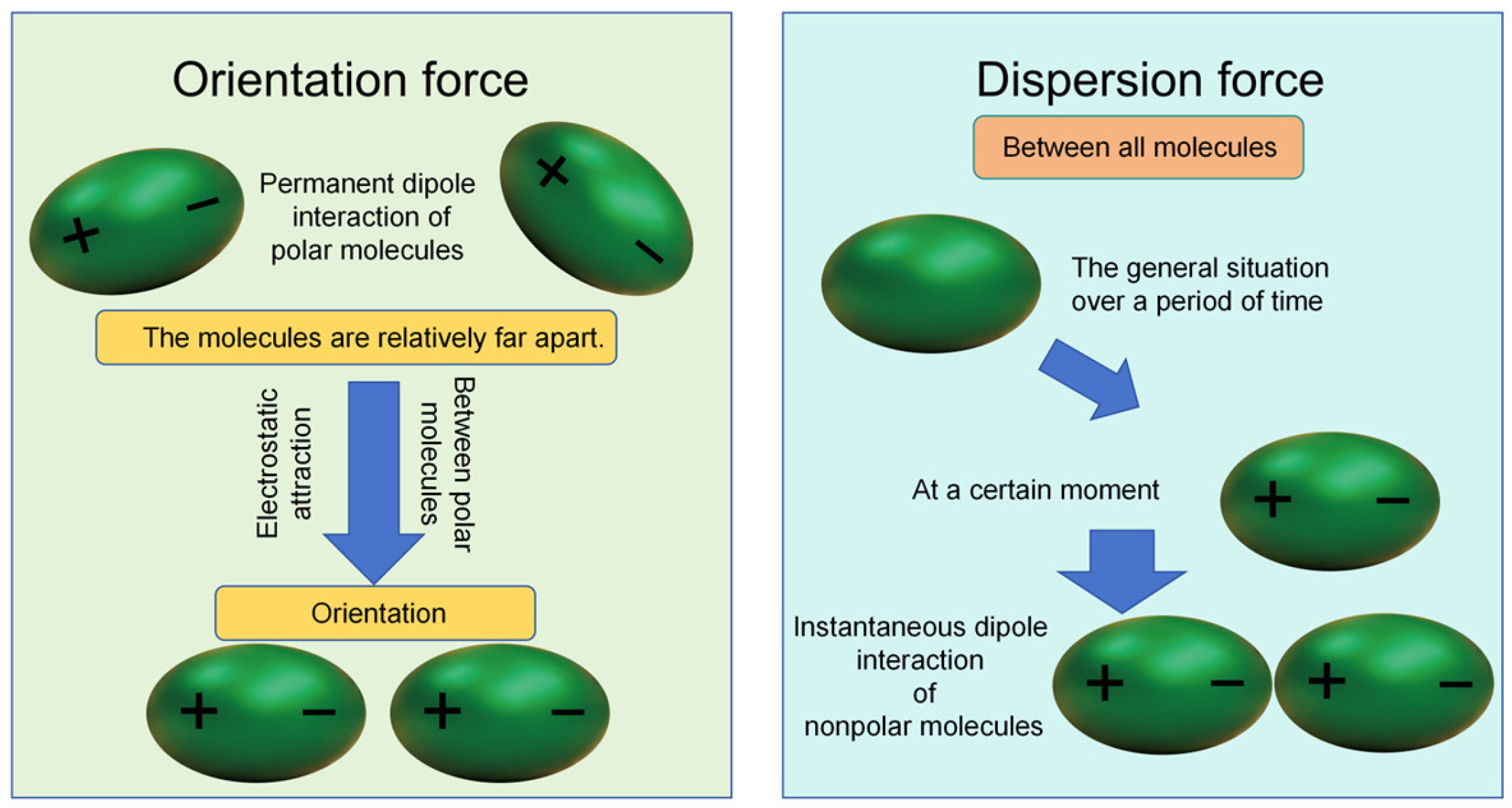

- The core mechanisms by which carbon-based materials treat water, atmospheric, and soil pollutants have been elucidated, including adsorption mechanisms (clearly distinguishing between physical and chemical adsorption) and physicochemical degradation mechanisms. Concurrently, the degradation characteristics of different carbon-based materials and their specific impacts on pollutant treatment efficacy have been analyzed.

- Integrating new findings in the field, targeted physicochemical modification strategies have been proposed to effectively overcome the limitations of existing carbon-based materials in pollutant treatment.

- Practical Application Value: The modified carbon-based materials developed through this modification strategy significantly enhance pollutant adsorption efficiency and improve material regeneration capacity while reducing industrial application costs. This achieves a balance between environmental protection requirements and practical production needs.

- Technical and Engineering Value: This work charts the course for carbon-based material technology development, outlines the prospects for green intelligent modification techniques, and proposes equipment optimization solutions aligned with industrial needs. It delivers engineered solutions for multi-media synergistic pollutant remediation, propelling the technology from laboratory research to practical industrial application.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Application of Carbon-Based Materials in Pollutant Treatment

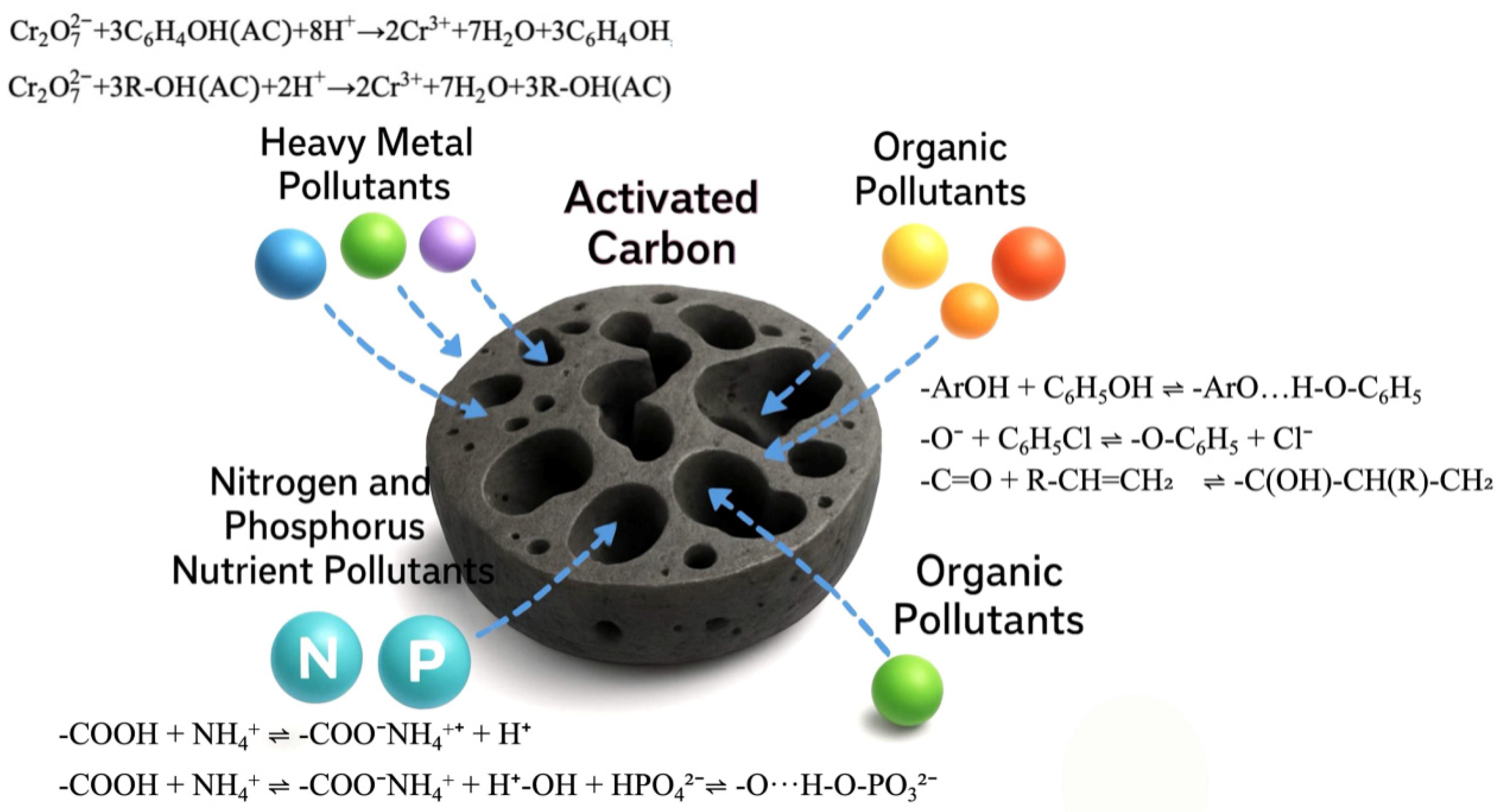

2.1. Treatment of Water Environmental Pollutants

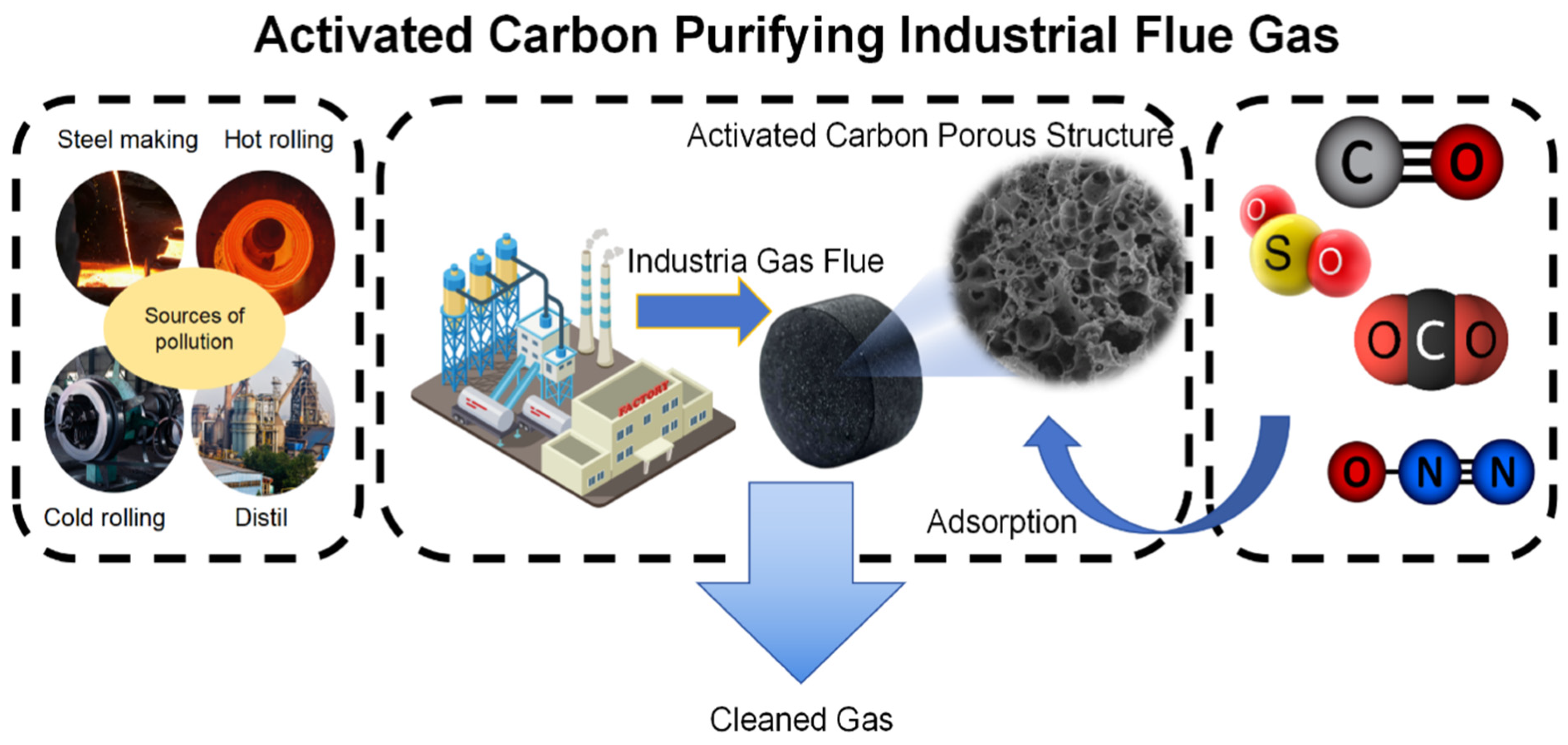

2.2. Air Pollutant Treatment

2.3. Soil Pollutant Treatment

3. Loss Mechanism of Carbon-Based Materials in the Pollutant Treatment Process

3.1. Carbon-Based Material Loss Overview

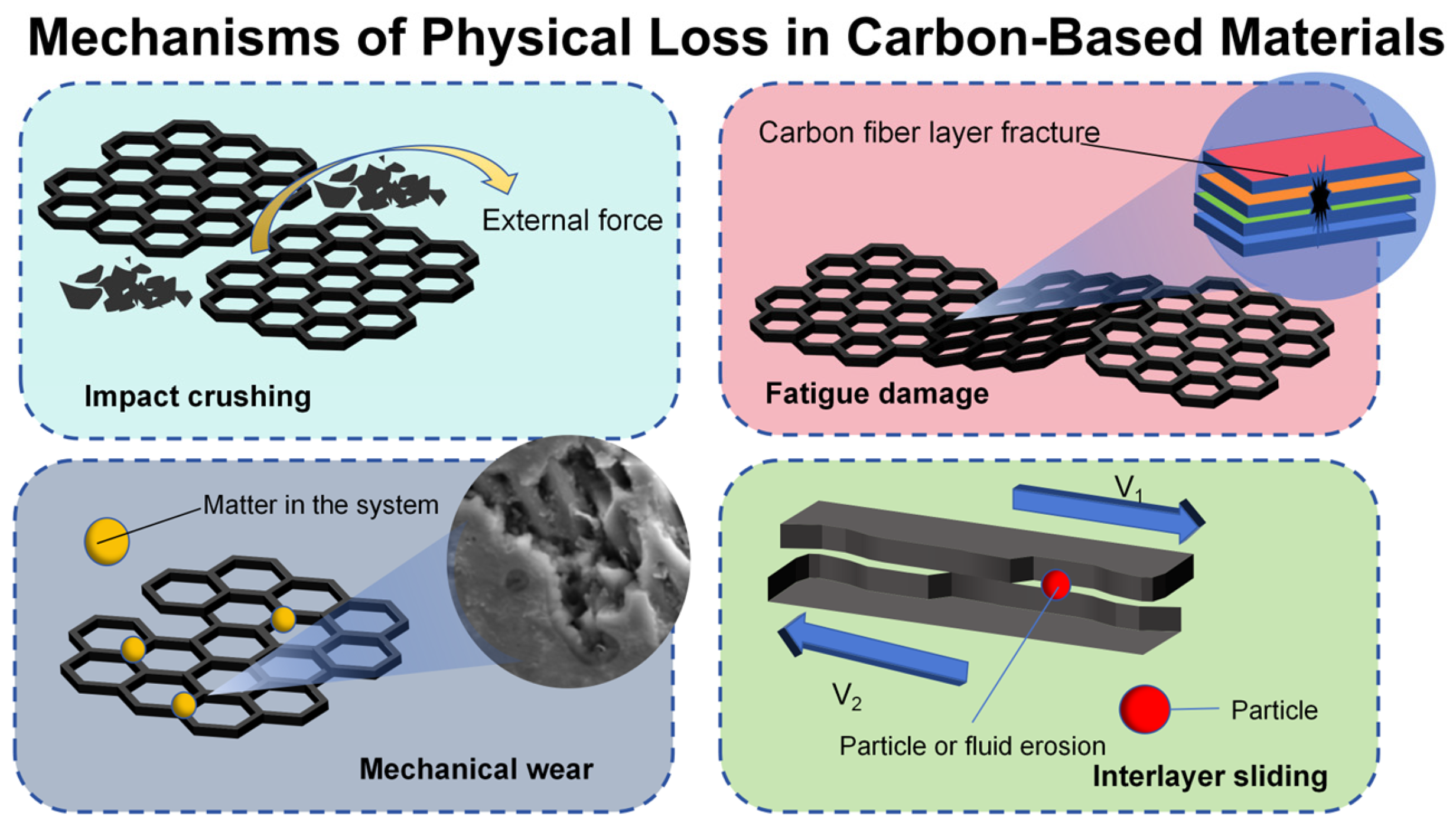

3.2. Physical Loss Mechanism

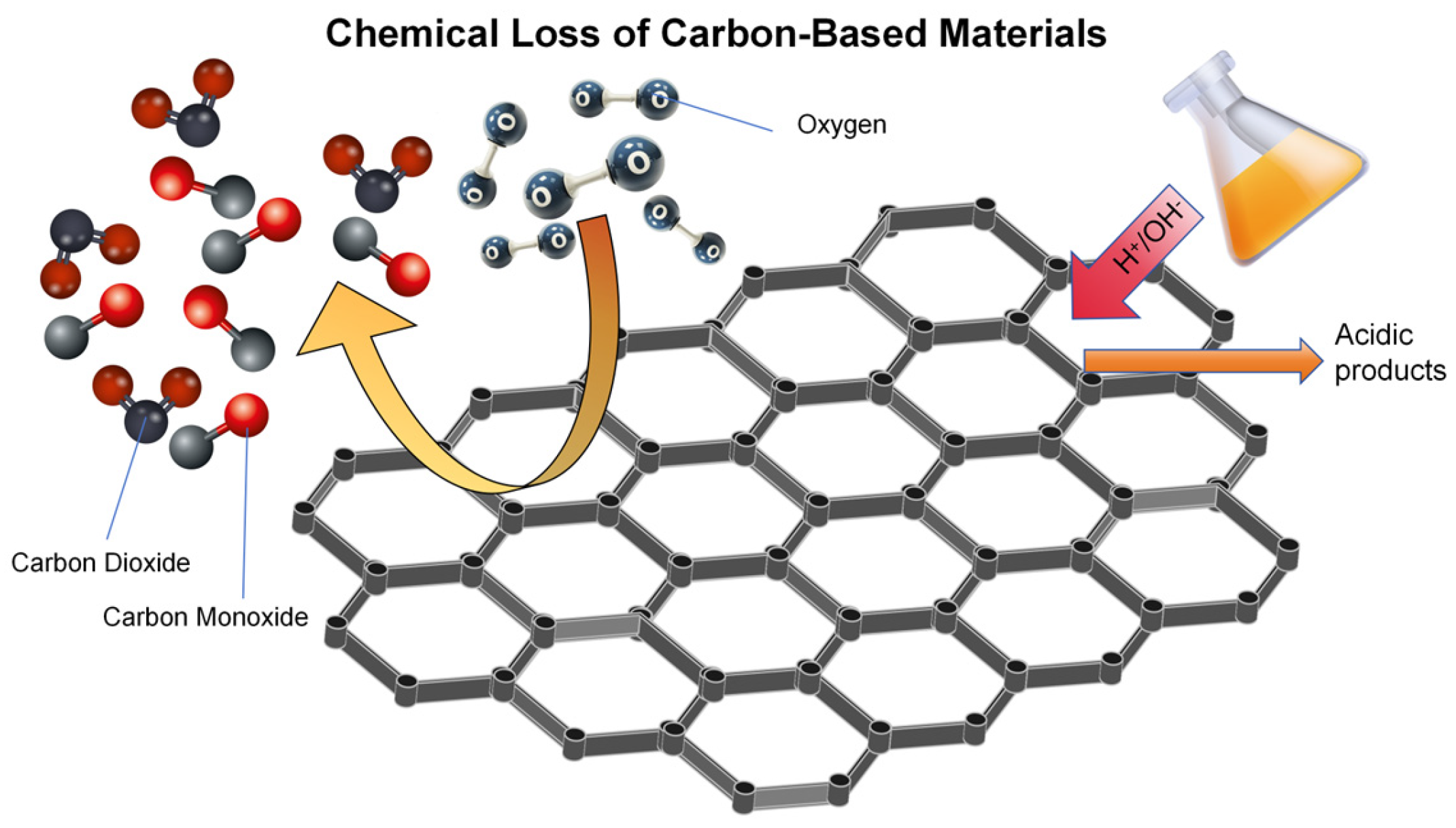

3.3. Chemical Loss Mechanism

4. Strategy of Modification of Carbon-Based Materials

4.1. Necessity of Modification of Carbon-Based Materials

4.2. Physical Modification

4.3. Chemical Modification

5. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. 2024 China Ecological Environment Status Bulle-tin. 2025. Available online: https://mee.gov.cn/hjzl/sthjzk/zghjzkgb/202506/P020250604527010717462.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Ruan, R.; Bashir, M.J.K. (Eds.) Environmental Pollution Governance and Ecological Remediation Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-25284-6 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Yang, W.; Jiang, B.; Che, S.; Yan, L.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. Research progress on carbon-based materials for electromagnetic wave absorption and the related mechanisms. New Carbon Mater. 2021, 36, 1016–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xie, P.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y. Preparation of graphene-based active carbons from petroleum asphalt for high-performance supercapacitors without added conducting materials. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2022, 65, 2866–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Pei, J. The characteristic of competitive adsorption of HCHO and C6H6 on activated carbon by molecular simulation. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2023, 73, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Zhu, J. Application and Development Prospects of Activated Carbon in Heavy Metal Pollution Treatment. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 2025, 125, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhachemi, M. Adsorption of organic compounds on activated Carbons. In Sorbents Materials for Controlling Environmental Pollution; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, J. Cd2+ Adsorption Property of Modified Activated Carbon Prepared from Beet Pulp. Chem. Ind. For. Prod. 2013, 33, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Xu, Q.; Abou-Elwafa, S.F.; Alshehri, M.A.; Zhang, T. Hydrothermal Carbonization Technology for Wastewater Treatment under the “Dual Carbon” Goals: Current Status, Trends, and Challenges. Water 2024, 16, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurali, M.; Rajan, M. Coconut shells based MrGO@CMC adsorbent for the chromium (VI) ion removal from contaminated water through batch adsorption method. Results Surf. Interfaces 2024, 17, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y. Research progress on preparation of magnetic activated carbon and its application in water treatment. Chin. J. Process Eng. 2024, 24, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, M.; He, J.; Wu, Y.; Sun, J.; Wen, X. Waste cotton-based activated carbon with excellent adsorption performance towards dyes and antibiotics. Chemosphere 2025, 376, 144292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheraz, N.; Shah, A.; Haleem, A.; Iftikhar, F.J. Comprehensive assessment of carbon-, biomaterial- and inorganic-based adsorbents for the removal of the most hazardous heavy metal ions from wastewater. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 11284–11310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.-M.; Xu, Z.-X.; Zhang, C.-M.; Wang, J.-L.; Li, K.-X. Surface modification of activated carbon for CO2 adsorption. Carbon 2014, 76, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zhang, C.; Liu, C.; He, G.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Chu, B.; He, H. A review on the heterogeneous oxidation of SO2 on solid atmospheric particles: Implications for sulfate formation in haze Chemistry. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 1888–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z. Effect of Acid Rain on Human Living Environment and Human Self. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 69, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Xu, S.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, F.; Sun, Q.; Wennersten, R.; Yang, L. The Effect of Nitrogen- and Oxygen-Containing Functional Groups on C2H6/SO2/NO Adsorption: A Density Functional Theory Study. Energies 2023, 16, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.K.; Vivekanandhan, S.; Das, O.; Millán, L.M.R.; Klinghoffer, N.B.; Nzihou, A.; Misra, M. Biocarbon Materials. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2024, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lou, C.; Zhao, W. Modification of the adsorption model for the mixture of odor compounds and VOCs on activated Carbon: Insights from pore size distribution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 339, 126669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, L.; Li, F.; He, P.; Cao, Y.; Li, H.; Guo, K. Preparation of Kapok-Based Activated Carbon Fibers and Their Adsorption Per-formance for Volatile Organic Compounds. J. Beijing Univ. Chem. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 43, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeguirim, M.; Belhachemi, M.; Limousy, L.; Bennici, S. Adsorption/reduction of nitrogen dioxide on activated carbons: Textural properties versus surface chemistry—A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 347, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Y. NO removal activity and surface characterization of activated carbon with oxidation modification. J. Energy Inst. 2017, 90, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Ma, W.; Zeng, Z.; Ma, X.; Xu, X.; Guo, Y.; Li, H.; Li, L. Experimental and DFT study on the adsorption of VOCs on activated carbon/metal oxides composites. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 372, 1122–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Biomass carbon-based composites for adsorption/photocatalysis degradation of VOCs: A comprehensive review. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2023, 57, 100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhu, M. Manipulating the structure of covalent organic frameworks through P-π resonance toward excellent tribological properties. Carbon 2025, 238, 120307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Feng, Y.; Xiao, Y. Interaction between biochar of different particle sizes and clay minerals in changing biochar physicochemical properties and cadmium sorption capacity. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428, 139348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, D.; Zou, W.; Feng, X.; Wang, R.; Zheng, R.; Luo, S.; Chu, Z.; Chen, H. Mechanistic insights into the synergetic remediation and amendment effects of zeolite/biochar composite on heavy metal-polluted red soil. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2024, 18, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, W.; Zhou, L.; Cai, D.; Ren, C. H3PO4-activated biochars derived from different agricultural biomasses for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous solution. Particuology 2023, 75, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Effects and Mechanisms of Phosphorus-Modified Biochar on Organic Carbon Sequestration in Manga-nese-Contaminated Soils. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Greenberg, I.; Ludwig, B.; Hippich, L.; Fischer, D.; Glaser, B.; Kaiser, M. Effect of biochar and compost on soil properties and organic matter in aggregate size fractions under field conditions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 295, 106882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Li, X. Application and Prospects of Modified Biochar in Cadmium-Contaminated Paddy Soils. Shandong Chem. Ind. 2025, 5416, 37–41+45. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Cao, H.; Gao, Y.; Qiu, S.; Chen, S.; Yue, C.; Zhou, J. Study on the Remediation of Organically Polluted Soils Using Magnetic/Solubilized Biochar Adsorption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 48, 165–172+190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Feng, H.; Tang, L.; Pang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zou, J.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Y.; Feng, C.; Wang, J. Insight into the key factors in fast adsorption of organic pollutants by hierarchical porous biochar. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Science and Technology Museum. Biochar’s “Money-Sucking Tricks”. 2019. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1652072921573950866&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Abulikemu, G.; Wahman, D.G.; Sorial, G.A.; Nadagouda, M.; Stebel, E.K.; Womack, E.A.; Smith, S.J.; Kleiner, E.J.; Gray, B.N.; Taylor, R.D.; et al. Role of grinding method on granular activated carbon characteristics. Carbon Trends 2023, 11, 100261, ISSN 2667-0569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Hou, F.; Bai, Z. Macro–Micro Damage and Failure Behavior of Creep Gas-Bearing Coal Subjected to Drop Hammer Impact. Nat. Resour. Res. 2024, 33, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Ge, D.; Lin, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, G.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tian, X.; Sun, J.; et al. Hollow Co9S8-carbon fiber hierarchical heterojunction with Schottky contacts for tunable microwave absorption. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 671, 160708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahle-Demessie, E.; Han, C.; Varughese, E.; Acrey, B.; Zepp, R. Fragmentation and release of pristine and functionalized carbon nanotubes from epoxy-nanocomposites during accelerated weathering. Environ. Sci. Nano 2023, 10, 1812–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinharoy, A.; Lens, P.N.L. Biological Removal of Selenate and Selenite from Wastewater: Options for Selenium Recovery as Nanoparticles. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2020, 6, 230–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Xie, W.; Yang, Q.; Xu, C.; Yang, F.; Gao, B.; Meng, S. Ablation and mechanical behaviour of C/C composites under an oxyacetylene flame and tensile loading environment. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 6321–6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpenev, A.; Muravyeva, T.; Shkalei, I.; Kulakov, V.; Golubkov, A. The study of the surface fracture during wear of C/C fiber composites by SPM and SEM. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2020, 28, 1702–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toribio, J.; Matos, J.-C.; González, B. Corrosion-Fatigue Crack Growth in Plates: A Model Based on the Paris Law. Materials 2017, 10, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohgami, T.; Kimpara, I.; Kageyama, K.; Suzuki, T.; Ohsawa, I. Computational modeling for dynamic fracture process of FRP laminates under multiaxial impact loading. Adv. Compos. Mater. 1994, 3, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Leal, E.; Martínez-Guerra, E.; Chavez-Valdez, A.; Arizmendi-Morquecho, A. Effect of the reinforcement phase on the electrical and mechanical properties of Cu–SWCNTs nanocomposites. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 142, 110765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, F.S.; Dusenbury, J.S.; Paulsen, P.D.; Singh, J.; Mazyck, D.W.; Maurer, D.J. Advanced oxidant regeneration of granular activated carbon for controlling air-phase VOCs. Ozone Sci. Eng. 1996, 18, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruffi, C.; Brandl, C. Vacancy segregation and intrinsic coordination defects at (1 1 1) twist grain boundaries in diamond. Acta Mater. 2023, 260, 119253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhu, C.; Gao, S.; Guan, C.; Huang, Y.; He, W. N-doped porous carbon nanoplates embedded with CoS2 vertically anchored on carbon cloths for flexible and ultrahigh microwave absorption. Carbon 2020, 163, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moguchikh, E.; Paperj, K.; Pavlets, A.; Alekseenko, A.; Danilenko, M.; Nikulin, A. Influence of Composition and Structure of Pt-Based Electrocatalysts on Their Durability in Different Conditions of Stress-Test. In Springer Proceedings in Materials; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, X.; Zhou, S.; He, Z.; Ji, G.; Ge, N. Molecular dynamics study on oxidation mechanism of carbon-based ablative ma-terials under high temperature. J. Sichuan Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 60, 34003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Du, C. Nitrogen-Doped Biochar for Enhanced Peroxymonosulfate Activation to Degrade Phenol through Both Free Radical and Direct Oxidation Based on Electron Transfer Pathways. Langmuir 2024, 40, 8520–8532. Available online: https://www.x-mol.com/paperRedirect/1778972345666019328 (accessed on 25 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Chen, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y. Cotton-Based Activated Carbon Fiber with High Specific Surface Area Prepared by Low-Temperature Hydrothermal Carbonization with Urea Enhancement. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 8744–8753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Yang, L.; Shao, P.; Shi, H.; Chang, Z.; Fang, D.; Wei, Y.; Feng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yu, K.; et al. Proton Self-Enhanced Hydroxyl-Enriched Cerium Oxide for Effective Arsenic Extraction from Strongly Acidic Wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 10412–10422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Chi, W.; Shen, Z.; Hu, L. Effects of Different Alkali and Acid Treatments on the Structure and Morphology of Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon Technol. 2008, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J. Study on oxygen loss of activated carbon during its desorption process. Energy Conserv. 2025, 44, 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, S.; Bai, Y.; Gao, F.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, P.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; et al. Carbon nanotube films with ultrahigh thermal-shock and thermal-shock-fatigue resistance characterized by ultra-fast ascending shock testing. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 6777–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Current Status of Activated Carbon Application in Integrated Treatment of Sintering Flue Gas. National Energy Information Platform. 2020. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1664627409508071209&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Chinese Academy of Engineering, Division of Chemical Engineering, Metallurgy and Materials Engineering; Chinese Materials Research Society. Report on the Application of New Materials Technology in China; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2022; p. 373. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Ge, L.; Li, X.; Zuo, M.; Xu, C.; Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C. Effects of the carbonization temperature and intermediate cooling mode on the properties of coal-based activated carbon. Energy 2023, 273, 127177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Xing, Z.-J.; Duan, Z.-K.; Li, M.; Wang, Y. Effects of steam activation on the pore structure and surface chemistry of activated carbon derived from bamboo waste. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 315, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Villegas, J.; Durán-Valle, C. Pore structure of activated carbons prepared by carbon dioxide and steam activation at different temperatures from extracted rockrose. Carbon 2002, 40, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Jiang, X.; Song, Y.; Jing, X.; Xing, X. The effect of activation temperature on the structure and properties of blue coke-based activated carbon by CO2 activation. Green Process. Synth. 2019, 8, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Peng, J.; Li, W.; Yang, K.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Xia, H. Effects of CO2 activation on porous structures of coconut shell-based activated carbons. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 8443–8449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinke, P.; van der Eijk, M.; Verbree, M.; Voskamp, A.; van Bekkum, H. Modification of the surfaces of a gasactivated carbon and a chemically activated carbon with nitric acid, hypochlorite, and ammonia. Carbon 1994, 32, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, N.; Setyadhi, L.; Wibowo, D.; Setiawan, J.; Ismadji, S. Adsorption of benzene and toluene from aqueous solutions onto activated carbon and its acid and heat treated forms: Influence of surface chemistry on adsorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 146, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

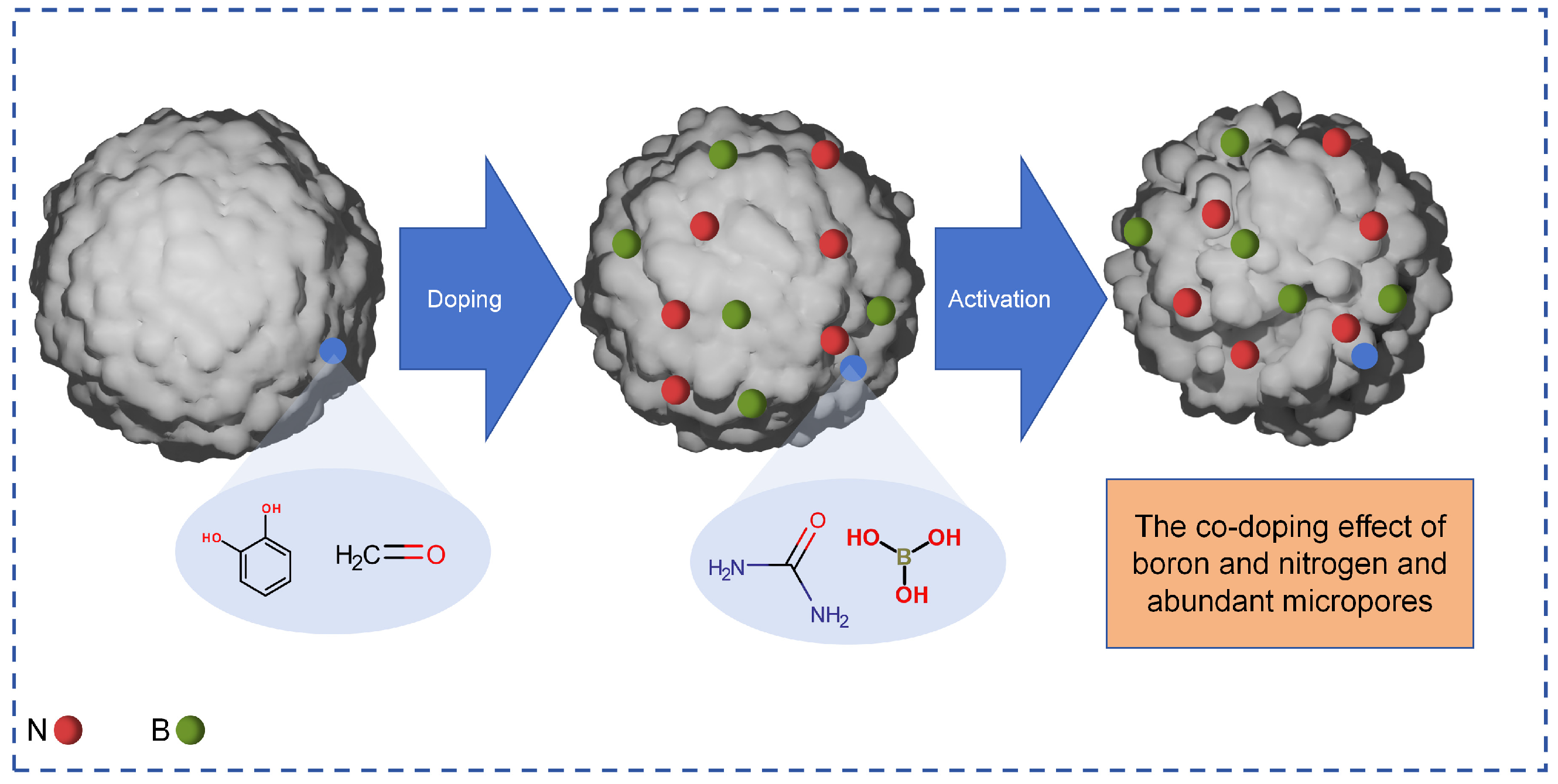

- Sun, T.; Liu, Y.; Xu, D.; Xu, G.; Ding, Y.; Fan, B.; Liu, D. Boosting supercapacitor performance through the facile synthesis of boron and nitrogen co-doped resin-derived carbon electrode material. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 138, 110258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Zhao, M.; Xu, M.; Chen, S.; Wu, H.; Luo, J.; Zhu, K. Study on Adsorption of Toluene Waste Gas by Acid-base Modified Waste Activated Carbon. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transportation, Shanghai, China, 17–19 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D.; Yi, X. Preparation, characterization, and adsorption performance of FeCl3-modified activated carbon. J. Trop. Biol. 2023, 14, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, J.; Koprivica, M.; Ercegović, M.; Simić, M.; Dimitrijević, J.; Bugarčić, M.; Trifunović, S. Synthesis and Application of FeMg-Modified Hydrochar for Efficient Removal of Lead Ions from Aqueous Solution. Processes 2025, 13, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pollution Type | Main Components and Sources | Environmental Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Heavy metal ion pollution | Pb, Cd, Hg, Cr, As, etc., source: industrial wastewater, mining, electronic waste, etc. | Disrupts soil structure and affects water quality |

| Organic pollutant pollution | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pesticides (DDT and organophosphorus), plasticizers (phthalates), microplastics, etc.; source: industrial wastewater, agricultural pesticide use, plastic waste, etc. | Difficult to degrade, prone to causing compound pollution. |

| Nitrogen and phosphorus nutrient pollution | Nutrient elements such as N and P; source: agricultural fertilizer loss, domestic sewage, industrial wastewater (such as food processing and detergent). | Water bodies are eutrophic, and water quality is deteriorating. |

| Contaminant | Hazard Performance | Harm Principle |

|---|---|---|

| SO2 | 1. Forming sulfuric acid rain. 2. Participate in the formation of secondary particulate matter. 3. Reducing atmospheric visibility. | 1. Oxidation in the atmosphere to form SO3, combined with water vapor to form H2SO3 aerosol or acid rain. 2. React with ammonia and metal ions in the atmosphere to produce secondary particles such as ammonium sulfate and iron sulfate, aggravating haze. 3. Particles scatter and absorb light to reduce atmospheric visibility. |

| NOx | 1. Forming nitric acid rain. 2. Drive photochemical smog formation. 3. Participate in ozone pollution. 4. Promoting the formation of secondary particles. | 1. NO2 reacts with water vapor to form HNO3 and NO, and HNO3 participates in the formation of acid rain. 2. Photochemical reaction occurs with VOCs under ultraviolet light irradiation, generating strong oxidizing pollutants such as O3, PAN, and forming photochemical smog. 3. As a key precursor of ozone formation, it promotes the increase in tropospheric O3 concentration. |

| VOCs | 1. Participate in the generation of photochemical smog and ozone. 2. Promoting the formation of secondary organic aerosol (SOA). 3. Some VOCs have a greenhouse effect. | 1. As the core precursor of photochemical reaction, it reacts with NO under light to continuously generate O3 and other oxidizing species. 2. Low volatile organic compounds are generated by oxidation reaction, and SOA is formed through condensation, adsorption, and other processes to increase the concentration of atmospheric particulate matter. 3. Some VOCs, such as methane and freon, can absorb infrared radiation and aggravate the greenhouse effect. |

| Indicator | Biochar | Clay Minerals | Zeolite Composite Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption mechanism | Chemical complexation, ion exchange, and precipitation to prevent migration | Cation exchange, complexation | Ion exchange and adsorption binding |

| Adsorption capacity | Affected by functional group density and preparation conditions | Higher, but easily constrained by acidic or alkaline environments | Highest capacity, but relatively high cost |

| Environmental Adaptability | With changes in pyrolysis conditions and pH value | Performance declines under acidic or high-salt conditions. | Structures may become unstable in acidic and strongly saline environments. |

| Preparation and Cost | The preparation technology is mature and low-cost. | Abundant natural resources, low costs | Complex manufacturing process, high cost |

| Application Prospects | High repair efficiency, with modified technology to adapt to varying pollution conditions | Suitable for rapid repair under neutral conditions | It performs exceptionally well in water treatment and can be extended to specific complex systems. |

| Material Type | Main Loss Modes | Embodiment |

|---|---|---|

| carbon fiber composite | mechanical wear | The fiber and resin interface debonding and fiber fracture result in a decrease in material strength. |

| environmental erosion | Humidity, salt fog, and so on lead to resin degradation and fiber oxidation corrosion. | |

| Fatigue damage | Micro-cracks are generated and propagated under cyclic loading, causing structural failure. | |

| Carbon nanotube materials | Dispersion loss | The agglomeration of nanotubes leads to a decrease in electrical/thermal conductivity, and an improper dispersion process leads to performance degradation. |

| Chemical oxidation | Strong oxidant destroys the structure of carbon nanotubes and affect the electrical properties. | |

| High temperature degradation | When the temperature exceeds the tolerance temperature, the carbon tube structure collapses or transforms into other carbon forms. | |

| Graphene materials | Layer increase/defect generation | In the preparation process, the number of stacked layers increases, or mechanical stripping produces lattice defects, resulting in performance degradation. |

| Physical adsorption saturation | As an adsorption material, the surface functional groups are occupied by pollutants and lose their adsorption capacity. | |

| Interlayer sliding loss | Multilayer graphene has interlayer dislocations under the action of shear force, which affects the overall mechanical and electrical properties. | |

| activated charcoal | pore plugging | During the adsorption process, micropores are filled with macromolecular contaminants, resulting in a decrease in adsorption capacity. |

| Mechanical crushing | In a high flow rate fluid or vibration environment, granular activated carbon is worn and broken, which reduces the efficiency of use. | |

| Regenerative failure | In the process of high temperature or chemical regeneration, the structure of activated carbon collapses, and the adsorption performance cannot be restored. | |

| Diamond (carbon material) | heat injury | At high temperatures, it reacts with oxygen to form CO2, resulting in a decrease in hardness and optical properties. |

| impact crusher | Brittle fracture leads to the collapse of diamond particles and the loss of cutting ability. | |

| chemical corrosion | In a strong acid/base environment, the carbon atoms on the surface of the diamond are eroded, and the crystal structure is destroyed. |

| Loss Type | Mechanism of Action | Related Formulas and Principles |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical wear | Friction causes surface particles to peel off, deform, or break. | Archers equation: Q = kFL/H Adhesive wear: shear separation after plastic deformation of asperities |

| Fatigue damage | Microcrack propagation induced by cyclic loading | Paris law: da/dN = C(ΔK)^m |

| Impact crushing | Instantaneous impact induced stress super strength limit | Stress wave theory: When the amplitude of the stress wave exceeds the dynamic strength of the material, the fracture occurs. |

| Interlayer sliding loss | The shear force makes the multi-layer materials dislocated between layers. | Shear force timeout sliding. |

| Depletion Type | Mechanism of Action | Typical Conditions | The Impact of Performance | Common Carbon-Based Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidation loss | Carbon materials react with oxygen/oxidant to produce CO2, CO, or carbon oxides. | High temperature, strong oxidant, combustion environment | Mass loss, strength decrease, surface roughness increase, and conductivity decrease | Carbon fiber, graphene, diamond, carbon nanotubes |

| Acid/base corrosion | Carbon materials react with strong acids/alkalis (such as oxidation and proton exchange). | Strong acid, strong alkali | Structural fragmentation, introduction of functional groups, and increased porosity | Activated carbon, carbon felt, carbon composite materials |

| Hydrolysis loss | Water molecules react with functional groups (such as ester groups and hydroxyl groups) on the surface of carbon materials. | High humidity environment, high temperature water/steam, acidic/alkaline aqueous solution | Interface debonding (composite material), polymer chain fracture, and mechanical properties degradation | Carbon-polymer composites |

| Photochemical degradation | Light energy (ultraviolet/visible light) triggers electronic excitation or free radical reaction of carbon materials. | UV irradiation (e.g., outdoor environment), presence of photosensitizer | Structural defects (such as vacancies and broken bonds), increased oxidation, and changes in optical properties | Graphene film, carbon-based optoelectronic devices |

| Electrochemical corrosion | The electrochemical reaction of carbon materials in the electrolyte solution occurs. | Electrochemical environment | The mass loss of electrode materials and the reduction in electrochemically active sites | Carbon electrode |

| Biodegradation | Microbial decomposition of carbon-based materials | Wet soil, in vivo environment, microbial-rich medium | The molecular chain breaks, and the mass gradually disappears | Bio-based carbon materials |

| Irradiation chemical damage | High-energy rays cause carbon bond breakage or cross-linking | Nuclear radiation environment, particle accelerator, space radiation | Free radical formation, structural disorder, and mechanical properties degradation | Nuclear graphite, aerospace carbon materials |

| Modification Method | Modification Principle | Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| High-temperature heat treatment | The activated carbon was heated under the protection of inert gas to promote the decomposition of unstable groups in the activated carbon, adjust the pore structure, reduce the surface heteroatoms, and improve the degree of graphitization. | It can significantly improve the thermal stability and chemical stability of activated carbon, expand the pore size and optimize the pore distribution, enhance the adsorption capacity of macromolecular substances, and there is no chemical pollution in the modification process. |

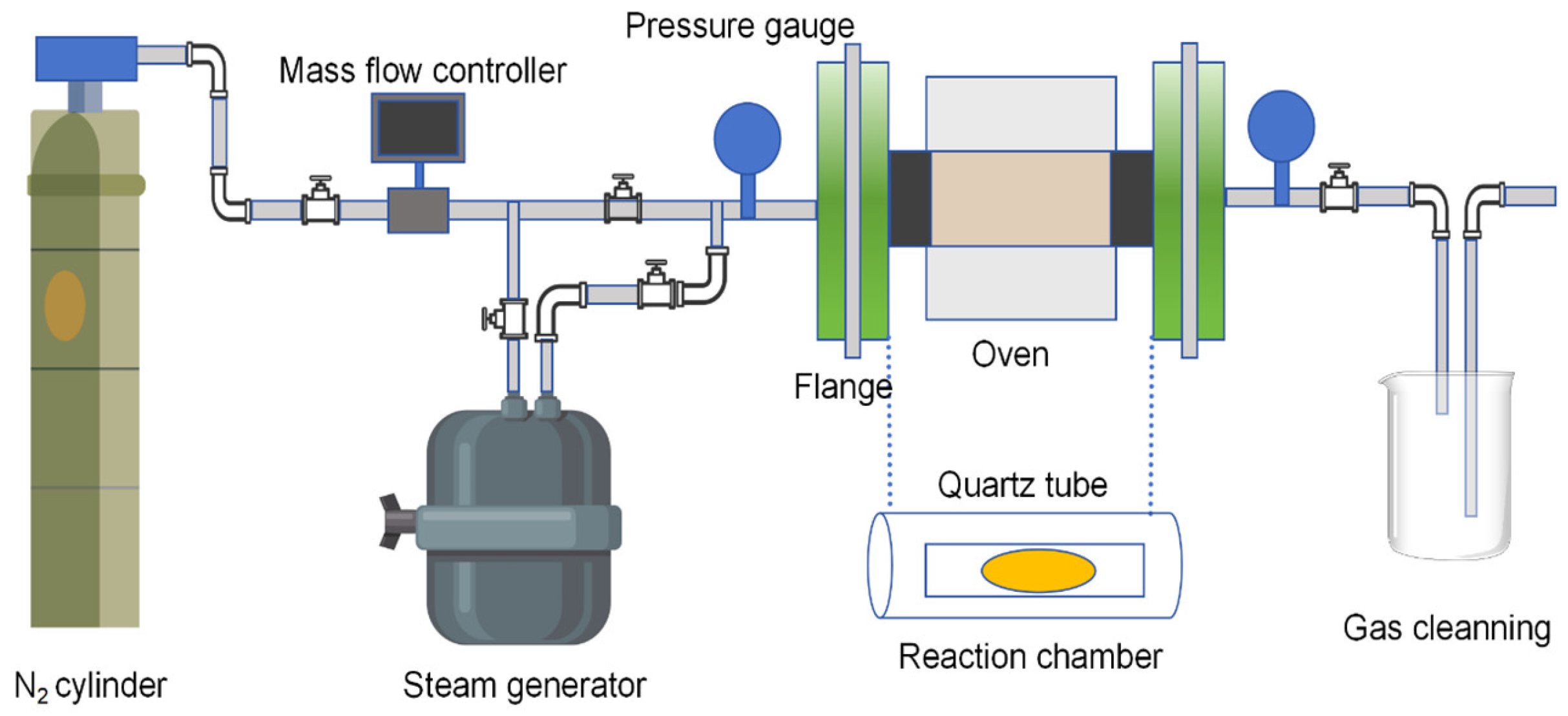

| Steam activation method | Using water vapor to react with carbon atoms on the surface of activated carbon at high temperature, new pores are formed on the etched surface, or the original pores are expanded to increase the specific surface area. | It can effectively increase the specific surface area and total pore volume, generate abundant micropores and mesopores, and have good adsorption effects on polar and non-polar substances. The process is mature and easy to scale. |

| CO2 activation method | At high temperature, CO2 reacts with carbon atoms in activated carbon, expands pores by selective etching, and regulates pore size and distribution. | It can precisely control the pore structure, generate more uniform micropores and mesopores, and has strong adsorption selectivity and excellent adsorption performance for non-polar substances. |

| Microwave modification method | The thermal effect of microwave is used to rapidly heat up the interior of activated carbon, causing a local high temperature to lead to pore structure reconstruction and promoting surface impurity desorption. | The heating speed is fast and uniform, which can shorten the modification time and avoid the thermal hysteresis of traditional heating. The adsorption rate of activated carbon after modification is significantly improved. |

| Classification | Core Principle | Main Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Oxidation modification | Oxygen-containing functional groups such as hydroxyl (-OH), carboxyl (-COOH), and carbonyl (C=O) were introduced by the reaction of oxidants (such as HNO3, H2O2, and O3) with carbon on the surface of activated carbon, and pores can be etched at the same time. | It significantly improves the adsorption capacity of polar substances (such as heavy metal ions and polar organic matter). The operation is relatively simple, and the introduction efficiency of functional groups is high. |

| Reduction modification | Some oxygen-containing groups were removed by the reaction of the reducing agent with oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of activated carbon, or reducing functional groups, such as amino (-NH2), were introduced to adjust the surface charge properties. | Enhance the adsorption and reduction ability of oxidizing pollutants (such as Cr6+ and NO3−), and improve the adsorption selectivity of non-polar substances. |

| Load modification | Metal ions or metal oxides were loaded on the pore and surface of activated carbon by impregnation and precipitation, and the adsorption was enhanced by the coordination of metal ions or the catalysis of metal oxides. | It has both adsorption and catalytic properties, and the adsorption capacity and degradation efficiency of specific pollutants (such as VOCs and dyes) are greatly improved, and the selectivity is strong. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meng, L.; Shao, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Hu, C.; Yang, G.; Shi, Y. Study on the Mechanism and Modification of Carbon-Based Materials for Pollutant Treatment. Materials 2025, 18, 5345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235345

Meng L, Shao Z, Li W, Wang J, Hu C, Yang G, Shi Y. Study on the Mechanism and Modification of Carbon-Based Materials for Pollutant Treatment. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235345

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Lingyi, Zitong Shao, Wenqi Li, Jianxiong Wang, Changqing Hu, Guangqing Yang, and Yan Shi. 2025. "Study on the Mechanism and Modification of Carbon-Based Materials for Pollutant Treatment" Materials 18, no. 23: 5345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235345

APA StyleMeng, L., Shao, Z., Li, W., Wang, J., Hu, C., Yang, G., & Shi, Y. (2025). Study on the Mechanism and Modification of Carbon-Based Materials for Pollutant Treatment. Materials, 18(23), 5345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235345