Laboratory Quantification of Gaseous Emission from Alternative Fuel Combustion: Implications for Cement Industry Decarbonization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Experimental Setup and Methodology

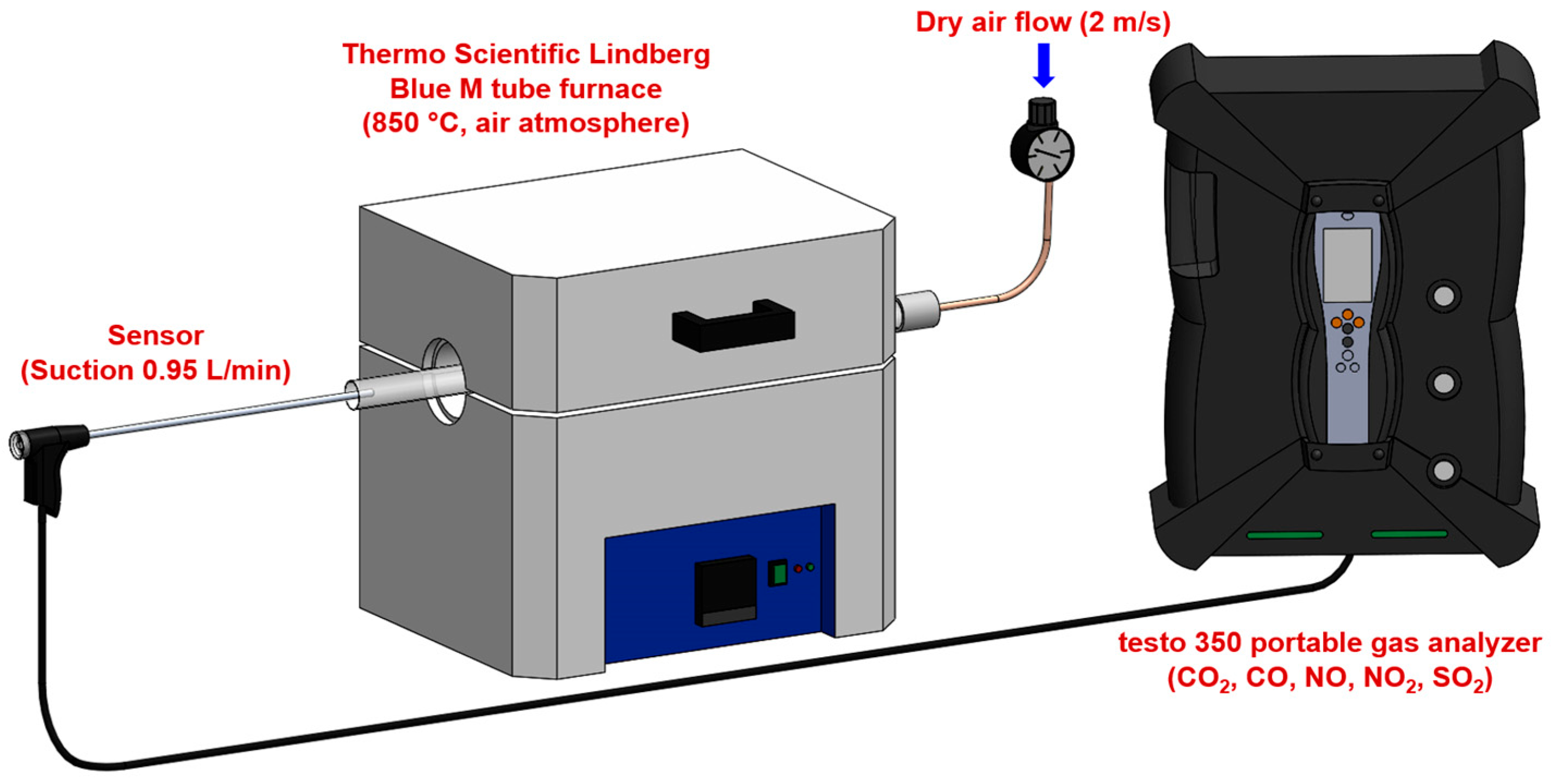

2.3.1. Combustion System Design

- Furnace specifications: a maximum operating temperature of 1200 °C with a temperature stability of ±5 °C, a heating rate of 10 °C/min to reach 850 °C, and isothermal hold capability for consistent combustion conditions. The temperature of 850 °C was selected to replicate the conditions in the precalciner zone of cement kilns, where alternative fuels are typically injected. At an industrial scale, the precalciner operates at temperatures between 800–900 °C, and alternative fuels introduced at this point undergo rapid combustion to provide heat for calcium carbonate decomposition [5]. This temperature represents the primary combustion environment for alternative fuels in modern cement production systems. The tube furnace’s circumferential heating elements create a uniform temperature profile within the isothermal zone (±5 °C), verified using a calibrated K-type thermocouple. Heat transfer to samples occurs primarily through radiation from furnace walls (dominant at 850 °C), supplemented by conduction and convection. Samples were consistently positioned at the center of the 15 cm isothermal zone to ensure identical thermal conditions across all experiments.

- Gas supply system: a dry air supply with flow velocity control at 2 m/s, flow rate monitoring using mass flow controllers, air composed of 21% O2 and 79% N2 (standard atmospheric composition), and an excess air (λ) ratio maintained at 1.5 to ensure complete combustion. The excess air ratio of λ = 1.5 was selected to represent typical industrial precalciner operating conditions (λ = 1.3–1.7) and to ensure adequate oxygen availability for complete combustion across all fuel types, while maintaining comparability between experiments.

- Literature data (Table 1) demonstrate that excess air ratio significantly influences combustion completeness and pollutant formation, though specific responses vary by fuel type and combustion system. For CO emissions, insufficient excess air (λ < 1.3) consistently results in elevated concentrations due to incomplete oxidation, while λ values above 1.5 typically provide diminishing returns in CO reduction [20,21]. NOx formation exhibits more complex behavior: at moderate temperatures (850 °C), fuel-NOx dominates over thermal-NOx, with emissions generally increasing 15–40% as λ increases from 1.3 to 1.8 due to enhanced oxidative conditions for nitrogen conversion [22,23,24]. The selected value of λ = 1.5 represents a practical compromise that ensures complete combustion (minimizing CO) while avoiding excessive oxygen that could exacerbate NOx formation, particularly for nitrogen-rich fuels. Systematic parametric investigation of λ effects for each alternative fuel would provide valuable optimization guidance but was beyond this study’s scope, which focused on establishing baseline emission factors under standardized, industrially relevant conditions for direct fuel comparison.

- Sample handling: quartz boats for sample containment during combustion, a sample mass of 1.000 ± 0.001 g for all experiments, and a positioning system for consistent sample placement within the furnace.

2.3.2. Gas Concentration Measurement

- Measurement parameters: CO2 (0–50% vol., resolution 0.01% (0–25 vol.%) and 0.1 vol.% (>25 vol.%)), CO (0–10,000 ppm, resolution 1 ppm), NO (0–4000 ppm, resolution 1 ppm), NO2 (0–500 ppm, resolution 0.1 ppm), and SO2 (0–5000 ppm, resolution 1 ppm). Note that NOx measurements are the sum of individual NO and NO2 measurements.

- Data acquisition: a sampling interval of 1 s, response time t90 < 40 s for all measured gases, continuous monitoring throughout the entire combustion process, and real-time data logging for subsequent analysis. The sampling interval of 1 s substantially exceeds the Nyquist criterion relative to the instrument response time (t90 < 40 s) and observed combustion time scales (60–960 s), ensuring accurate representation of concentration profiles without aliasing artifacts.

2.3.3. Experimental Protocol

2.3.4. Data Processing and Analysis

- Gas concentration profiles: raw concentration data (ppm) recorded as a function of time, baseline correction applied to account for background concentrations, and peaks identified and integrated using Simpson’s rule [28].

- Mass-based emission factors (kg gas/kg fuel): calculated using Equation (1) [15].

- Energy-based emission factors (kg gas/GJ): calculated using Equation (2) [15].

2.3.5. Lower Heating Value Determination

2.3.6. Validation and Calibration

- System validation: the system validation was performed using bituminous coal as a reference fuel. The measured CO2 emission factor for coal (18.5 kg CO2/GJ) falls within the literature range for bituminous coal (17.5–20.2 kg CO2/GJ), and the CO emission factor (71.5 g/kg) is consistent with published values for similar combustion temperatures [27]. Carbon mass balance calculations verified that measured CO2 and CO emissions accounted for the fuel carbon content within ±8% for all samples, confirming complete carbon accounting. Gas species identification was consistent with our previous TGA-MS analysis [10], providing independent analytical validation of the measurement system.

- Calibration procedures: the gas analyzer was calibrated daily using NIST-traceable certified span gases, with zero calibration performed using nitrogen. Regular maintenance and calibration checks were conducted according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Measurement reliability was ensured through these routine calibrations, triplicate testing (n = 3 per fuel), complementary TGA-MS analysis [10], and carbon mass balance verification (±8%). This integrated approach minimized systematic measurement errors and validated the reported emission factors.

3. Results

3.1. Time-Dependent Concentration of Gaseous Emissions

3.1.1. Carbon Dioxide Emissions

3.1.2. Carbon Monoxide Emissions

3.1.3. Nitrogen Oxide Emissions

3.1.4. Sulfur Dioxide Emissions

3.2. Mass-Based Emission Factors

3.3. Energy-Based Emission Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA). Concrete Future. The GCCA 2050 Cement and Concrete Industry Roadmap for Net Zero Concrete; Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA): London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA). Global Cement and Concrete Industry Announces Roadmap to Achieve Groundbreaking ‘Net Zero’ CO2 Emissions by 2050; Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA): London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA). GCCA Sustainability Guidelines for the Monitoring and Reporting of CO2 Emissions from Cement Manufacturing; Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA): London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zieri, W.; Ismail, I. Alternative Fuels from Waste Products in Cement Industry. In Handbook of Ecomaterials; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alsop, P.A. Cement Plant Operations Handbook: For Dry Process Plants; Tradeship Publications Ltd.: Luxembourg, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, A.A. Rotary Kilns: Transport Phenomena and Transport Processes; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.B.; Saidur, R.; Hossain, M.S. A review on emission analysis in cement industries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2252–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Elyazeed, O.S.M.; Nofal, M.; Ibrahim, K.; Yang, J. Co-combustion of RDF and biomass mixture with bituminous coal: A case study of clinker production plant in Egypt. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2021, 3, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Sasso, O.; Carreño Gallardo, C.; Soto Castillo, D.M.; Ojeda Farias, O.F.; Bojorquez Carrillo, M.; Prieto Gomez, C.; Herrera Ramirez, J.M. Valorization of Biomass and Industrial Wastes as Alternative Fuels for Sustainable Cement Production. Clean Technol. 2024, 6, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Sasso, O.; Carreño Gallardo, C.; Ledezma Sillas, J.E.; Robles Hernandez, F.C.; Ojeda Farias, O.F.; Prieto Gomez, C.; Herrera Ramirez, J.M. Thermal Behavior and Gas Emissions of Biomass and Industrial Wastes as Alternative Fuels in Cement Production: A TGA-DSC and TGA-MS Approach. Energies 2025, 18, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, P.; Shrestha, P.; Tamrakar, C.; Bhattarai, P. Studies on Potential Emission of Hazardous Gases due to Uncontrolled Open-Air Burning of Waste Vehicle Tyres and their Possible Impacts on the Environment. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 6555–6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cereceda-Balic, F.; Toledo, M.; Vidal, V.; Guerrero, F.; Diaz-Robles, L.A.; Petit-Breuilh, X.; Lapuerta, M. Emission Factors for PM2.5, CO, CO2, NOx, SO2 and Particle Size Distributions from the Combustion of Wood Species Using a New Controlled Combustion Chamber 3CE. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Albina, D.O.; Abdul Salam, P. Emission factors of wood and charcoal-fired cookstoves. Biomass Bioenergy 2002, 23, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A.W.; Astrup, T. CO2 emission factors for waste incineration: Influence from source separation of recyclable materials. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggleston, H.S.; Buendia, L.; Miwa, K.; Ngara, T.; Tanabe, K. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; IPCC: Kanagawa, Japan, 2006.

- Gómez, D.R.; Watterson, J.D. Stationary Combustion. In IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; IPCC: Kanagawa, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- GCC. 2022 GCC Sustainability Report; GCC: Chihuahua, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moiceanu, G.; Paraschiv, G.; Voicu, G.; Dinca, M.; Negoita, O.; Chitoiu, M.; Tudor, P. Energy Consumption at Size Reduction of Lignocellulose Biomass for Bioenergy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losaladjome Mboyo, H.; Huo, B.; Mulenga, F.K.; Mabe Fogang, P.; Kaunde Kasongo, J.K. Distribution of Operating Costs Along the Value Chain of an Open-Pit Copper Mine. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadamgahi, M.; Ölund, P.; Andersson, N.Å.I.; Jönsson, P. Numerical Study on the Effect of Lambda Value (Oxygen/Fuel Ratio) on Temperature Distribution and Efficiency of a Flameless Oxyfuel Combustion System. Energies 2017, 10, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warguła, Ł.; Kaczmarzyk, P.; Wieczorek, B.; Gierz, Ł.; Małozięć, D.; Góral, T.; Kostov, B.; Stambolov, G. Identification of the Problem in Controlling the Air–Fuel Mixture Ratio (Lambda Coefficient λ) in Small Spark-Ignition Engines for Positive Pressure Ventilators. Energies 2024, 17, 4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.; Hagen, F.P.; Büttner, L.; Hartmann, J.; Velji, A.; Kubach, H.; Koch, T.; Bockhorn, H.; Trimis, D.; Suntz, R. Influence of Global Operating Parameters on the Reactivity of Soot Particles from Direct Injection Gasoline Engines. Emiss. Control. Sci. Technol. 2022, 8, 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Su, D.; Zhong, M. The effect of functional forms of nitrogen on fuel-NOx emissions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Peckham, M.; Hall, J.; Jiang, C. A Comprehensive Experimental Investigation of NOx Emission Characteristics in Hydrogen Engine Using an Ultra-Fast Crank Domain Measurement. Energies 2024, 17, 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, T. CO2 Emissions from Stationary Combustion of Fossil Fuels. In Good Practice Guidance and Uncertainty Management in National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, J.F. Flame and Combustion; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, E.D.; Calvo, A.I.; Alves, C.; Blanco-Alegre, C.; Candeias, C.; Rocha, F.; Sánchez de la Campa, A.; Fraile, R. Residential Combustion of Coal: Effect of the Fuel and Combustion Stage on Emissions. Chemosphere 2023, 340, 139870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, B.H.; Valentine, D.T. Chapter 14—Introduction to Numerical Methods. In Essential MATLAB for Engineers and Scientists, 6th ed.; Hahn, B.H., Valentine, D.T., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 295–323. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D5865/D5865M-19; Standard Test Method for Gross Calorific Value of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Ozer, M.; Basha, O.M.; Stiegel, G.; Morsi, B. Effect of Coal Nature on the Gasification Process. In Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) Technologies, Wang, T., Stiegel, G., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 257–304. [Google Scholar]

- Racero-Galaraga, D.; Rhenals-Julio, J.D.; Sofan-German, S.; Mendoza, J.M.; Bula-Silvera, A. Proximate Analysis in Biomass: Standards, Applications and Key Characteristics. Results Chem. 2024, 12, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbone, D.; Turan, A. Thermodynamics of Combustion. In Advanced Thermodynamics for Engineers; Winterbone, D.E., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 182–207. [Google Scholar]

- Tillman, D.A. The combustion of solid fuels and wastes. In Combustion of Solid Fuels & Wastes; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 275–317. [Google Scholar]

- Riaza, J.; Gibbins, J.; Chalmers, H. Ignition and Combustion of Single Particles of Coal and Biomass. Fuel 2017, 202, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Dally, B.B. Solid Fuels Flameless Combustion. In Fundamentals of Low Emission Flameless Combustion and Its Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 505–552. [Google Scholar]

- Speight, J.G. Assessing Fuels for Gasification: Analytical and Quality Control Techniques for Coal. In Gasification for Synthetic Fuel Production. Fundamentals, Processes and Applications; Luque, R., Speight, J.G., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 175–198. [Google Scholar]

- Haberle, I.; Skreiberg, Ø.; Łazar, J.; Haugen, N.E.L. Numerical Models for Thermochemical Degradation of Thermally Thick Woody Biomass, and their Application in Domestic Wood Heating Appliances and Grate Furnaces. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2017, 63, 204–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Lou, C.; Xiao, B.; Lim, M. Visualization of Combustion Phases of Biomass Particles: Effects of Fuel Properties. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 27702–27710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Wu, C.; Williams, P.T. Pyrolysis of Waste Materials using TGA-MS and TGA-FTIR as Complementary Characterisation Techniques. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2012, 94, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo-Calado, L.; Hermoso-Orzáez, M.J.; Mota-Panizio, R.; Guilherme-Garcia, B.; Brito, P. Co-Combustion of Waste Tires and Plastic-Rubber Wastes with Biomass Technical and Environmental Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mianowski, A.; Robak, Z.; Tomaszewicz, M.; Stelmach, S. The Boudouard–Bell reaction analysis under high pressure conditions. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2012, 110, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Choi, Y.; Stenger, H.G. Kinetics, Simulation and Insights for CO Selective Oxidation in Fuel Cell Applications. J. Power Sources 2004, 129, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentes, D.; Tóth, C.E.; Nagy, G.; Muránszky, G.; Póliska, C. Investigation of gaseous and solid pollutants emitted from waste tire combustion at different temperatures. Waste Manag. 2022, 149, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.-C.; Escofet-Martin, D.; Dunn-Rankin, D. CO Emission from an Impinging Non-premixed Flame. Combust. Flame 2016, 174, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Bastiaans, R.J.M. A Comparison of Combustion Properties in Biomass–Coal Blends Using Characteristic and Kinetic Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbas, A.; Yuhana, N.Y. Recycling of Rubber Wastes as Fuel and Its Additives. Recycling 2021, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Song, Q.; He, B.; Yao, Q. Oxidation behavior of a kind of carbon black. Sci. China Ser. E Technol. Sci. 2009, 52, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lei, M.; Li, M.; Liu, C.; Xue, B.; Xiao, R. Comprehensive Estimation of Combustion Behavior and Thermochemical Structure Evolution of Four Typical Industrial Polymeric Wastes. Energies 2022, 15, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, F.; Andersson, K.; Leckner, B.; Johnsson, F. Emission control of nitrogen oxides in the oxy-fuel process. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2009, 35, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillman, S. The Relation between Ozone, NOx and Hydrocarbons in Urban and Polluted Rural Environments. Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 1821–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakomcic-Smaragdakis, B.; Cepic, Z.; Senk, N.; Doric, J.; Radovanovic, L. Use of Scrap Tires in Cement Production and their Impact on Nitrogen and Sulfur Oxides Emissions. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2016, 38, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdoğan, S. Estimation of CO2 Emission Factors of Coals. Fuel 1998, 77, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyo, R.; Wongwiwat, J.; Sukjai, Y. Numerical and Experimental Investigation on Combustion Characteristics and Pollutant Emissions of Pulverized Coal and Biomass Co-Firing in a 500 kW Burner. Fuels 2025, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieré, R.; Smith, K.; Blackford, M. Chemical Composition of Fuels and Emissions from a Coal+Tire Combustion Experiment in a Power Station. Fuel 2006, 85, 2278–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Jensen, A.D.; Glarborg, P. NO Formation during Oxy-Fuel Combustion of Coal and Biomass Chars. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 4684–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downard, J.; Singh, A.; Bullard, R.; Jayarathne, T.; Rathnayake, C.; Simmons, D.L.; Wels, B.R.; Spak, S.N.; Peters, T.; Beardsley, D.; et al. Uncontrolled Combustion of Shredded Tires in a Landfill—Part 1: Characterization of Gaseous and Particulate Emissions. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 104, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, S.; Sherif, Z.; Drewniok, M.; Bolson, N.; Cullen, J.; Purnell, P.; Jolly, M.; Salonitis, K. Potentials for Energy Savings and Carbon Dioxide Emissions Reduction in Cement Industry; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 765–773. [Google Scholar]

- Szczerba, J. Chemical corrosion of basic refractories by cement kiln materials. Ceram. Int. 2010, 36, 1877–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaivi, D.; Jibatswen, T.; Michael, O. Effect of Chlorine and Sulphur on Stainless Steel (AISI 310) Due To High Temperature Corrosion. Am. J. Eng. Res. 2016, 5, 266–270. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, L.J.R.; Matias, J.C.O.; Catalão, J.P.S. Biomass combustion systems: A review on the physical and chemical properties of the ashes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fuel Type | λ Range | CO Trend * | NOx Trend * | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bituminous coal | 1.2–1.8 | Decreases 60–80% as λ increases from 1.2 to 1.5; minimal change above λ = 1.5 | Increases 20–40% from λ = 1.3 to 1.8 due to enhanced oxidation conditions | [20,22] |

| Wood biomass | 1.3–2.0 | Sharp decrease below λ = 1.5 (incomplete combustion); stable above λ = 1.5 | Low overall (<50 ppm); slight increase (10–20%) at λ > 1.7 | [20,24] |

| Tire-derived fuel | 1.4–1.8 | High baseline CO; decreases 40–50% from λ = 1.4 to 1.6; modest further reduction at higher λ | Increases linearly ~ 15–25% per 0.1 λ increment due to fuel-N oxidation | [21,23] |

| Mixed waste | 1.3–2.0 | Highly variable; optimal range λ = 1.5–1.7 for CO minimization | Moderate sensitivity; increases 30–50% from λ = 1.5 to 2.0 | [20,21,24] |

| Sample | CO2 | CO | NOx | SO2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | 0.0400 ± 0.0022 | 2.3669 ± 0.0478 | 0.0082 ± 0.0005 | 0.4852 ± 0.0098 | * | 0.0006 ± (*) | - | - |

| PNS | 0.0507 ± 0.0011 | 2.8167 ± 0.0569 | 0.0219 ± 0.0001 | 1.2167 ± 0.0246 | * | 0.0022 ± (*) | - | - |

| WBW | 0.0468 ± 0.0010 | 4.0696 ± 0.0822 | 0.0190 ± 0.0004 | 1.6522 ± 0.0334 | 0.0001 ± (*) | 0.0087 ± 0.0002 | - | - |

| IHW | 0.3476 ± 0.0071 | 10.2235 ± 0.2065 | 0.0606 ± 0.0012 | 1.7824 ± 0.0360 | 0.0007 ± (*) | 0.0191 ± 0.0004 | - | - |

| TDF | 0.2319 ± 0.0048 | 6.3534 ± 0.1283 | 0.1112 ± 0.0023 | 3.0466 ± 0.0615 | 0.0018 ± (*) | 0.0496 ± 0.0010 | 0.0016 ± (*) | 0.0430 ± (*) |

| PW | 0.2405 ± 0.0049 | 8.2931 ± 0.1675 | 0.01812 ± 0.0004 | 0.6248 ± 0.0126 | 0.0002 ± (*) | 0.0062 ± 0.0001 | - | - |

| ASR | 0.0838 ± 0.0017 | 3.8091 ± 0.0769 | 0.0079 ± 0.0002 | 0.3591 ± 0.0073 | 0.0002 ± (*) | 0.0082 ± 0.0002 | - | - |

| Coal | 0.5406 ± 0.0112 | 19.4460 ± 0.3928 | 0.0715 ± 0.0015 | 2.5719 ± 0.0520 | 0.0005 ± (*) | 0.0191 ± 0.0004 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivera Sasso, O.; Ramirez Espinoza, E.; Carreño Gallardo, C.; Ledezma Sillas, J.E.; Diaz Diaz, A.; Ojeda Farias, O.F.; Prieto Gomez, C.; Herrera Ramirez, J.M. Laboratory Quantification of Gaseous Emission from Alternative Fuel Combustion: Implications for Cement Industry Decarbonization. Materials 2025, 18, 4859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214859

Rivera Sasso O, Ramirez Espinoza E, Carreño Gallardo C, Ledezma Sillas JE, Diaz Diaz A, Ojeda Farias OF, Prieto Gomez C, Herrera Ramirez JM. Laboratory Quantification of Gaseous Emission from Alternative Fuel Combustion: Implications for Cement Industry Decarbonization. Materials. 2025; 18(21):4859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214859

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivera Sasso, Ofelia, Elias Ramirez Espinoza, Caleb Carreño Gallardo, Jose Ernesto Ledezma Sillas, Alberto Diaz Diaz, Omar Farid Ojeda Farias, Carolina Prieto Gomez, and Jose Martin Herrera Ramirez. 2025. "Laboratory Quantification of Gaseous Emission from Alternative Fuel Combustion: Implications for Cement Industry Decarbonization" Materials 18, no. 21: 4859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214859

APA StyleRivera Sasso, O., Ramirez Espinoza, E., Carreño Gallardo, C., Ledezma Sillas, J. E., Diaz Diaz, A., Ojeda Farias, O. F., Prieto Gomez, C., & Herrera Ramirez, J. M. (2025). Laboratory Quantification of Gaseous Emission from Alternative Fuel Combustion: Implications for Cement Industry Decarbonization. Materials, 18(21), 4859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214859