Effect of Deep Cryogenic Treatment on Aging Strength of Mg–Al–Ca–Mn Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

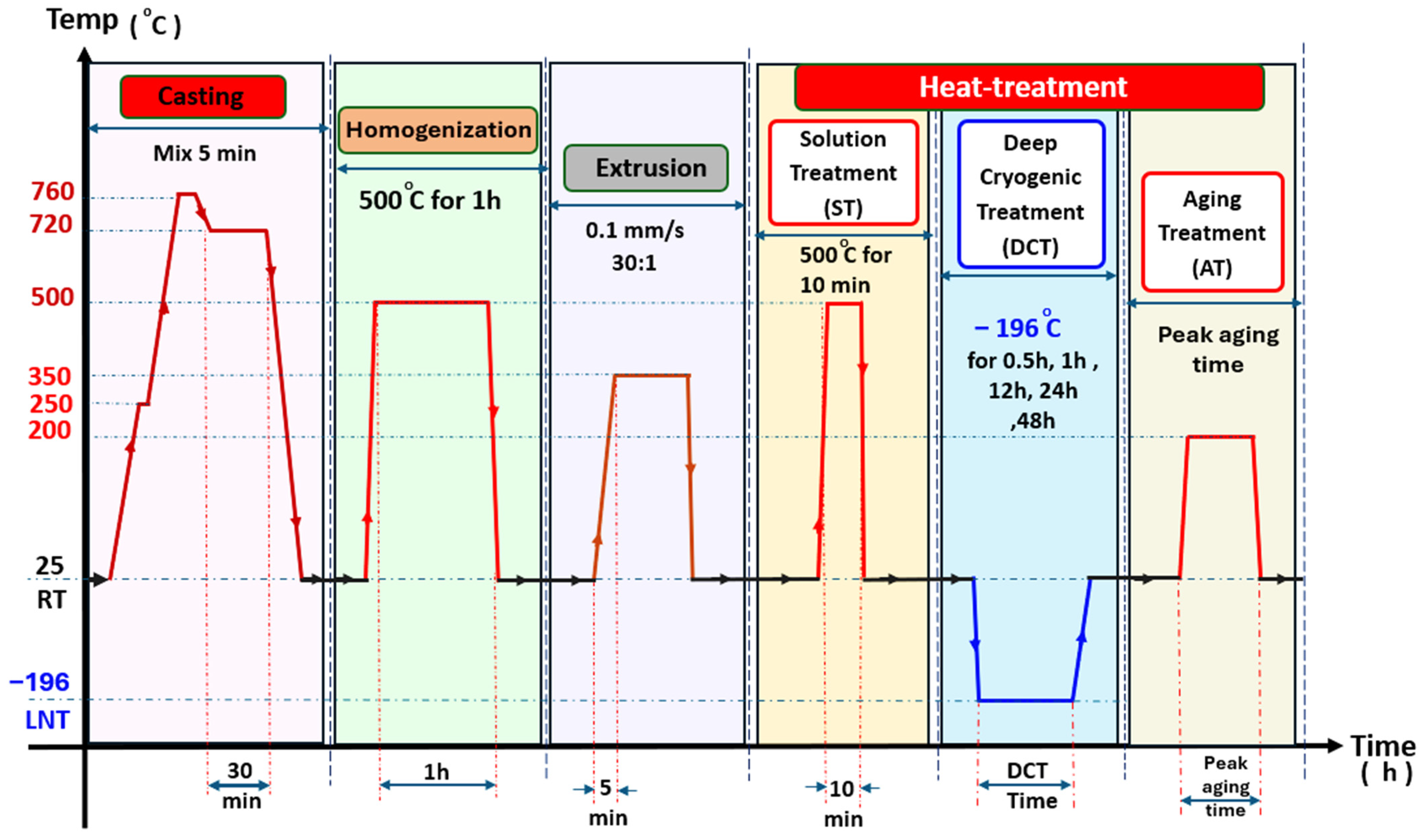

2.1. Alloy Preparation and Heat Treatment

2.2. Mechanical Testing and Microstructural Characterization

2.2.1. Mechanical Testing

2.2.2. Microstructural Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Mechanical Properties and Microstructural Characterizations

3.1.1. Mechanical Properties

3.1.2. Microstructural Characterizations

3.2. Precipitation Behavior

3.3. Fracture Characterization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Optimal Treatment Duration: A 12 h DCT through sequential treatment provided the most favorable mechanical property balance, yielding a peak hardness of 79 HV, tensile strength of 343 MPa (+18.3%), and elongation to failure of 27.3% (+5%). Longer durations enhanced strength but reduced ductility, highlighting the need for optimized cryogenic exposure time.

- Synergistic Strengthening Mechanisms: Strength improvements arose from refined (~29 nm) precipitates uniformly distributed within the matrix, nanoscale grain formation (with a range of 30–120 nm), grain boundary strengthening, and elevated dislocation density, which collectively contributed to substantial hardening.

- Ductility Enhancement Mechanisms: Improved ductility was linked to enhanced grain rotation, activation of non-basal slip systems, and suppression of premature microcrack initiation during deformation, enabling greater strain accommodation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nakata, T.; Xu, C.; Ajima, R.; Shimizu, K.; Hanaki, S.; Sasaki, T.T.; Ma, L.; Hono, K.; Kamado, S. Strong and Ductile Age-Hardening Mg-Al-Ca-Mn Alloy That Can Be Extruded as Fast as Aluminum Alloys. Acta Mater. 2017, 130, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Shin, K.S. Improved Stretch Formability of AZ31 Sheet via Grain Size Control. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 688, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, J.D.; Stanford, N.; Barnett, M.R. Effect of Precipitate Shape on Slip and Twinning in Magnesium Alloys. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 1945–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Jiao, Q.; Kecskes, L.J.; El-Awady, J.A.; Weihs, T.P. Effect of Basal Precipitates on Extension Twinning and Pyramidal Slip: A Micro-Mechanical and Electron Microscopy Study of a Mg–Al Binary Alloy. Acta Mater. 2020, 189, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandlöbes, S.; Pei, Z.; Friák, M.; Zhu, L.F.; Wang, F.; Zaefferer, S.; Raabe, D.; Neugebauer, J. Ductility Improvement of Mg Alloys by Solid Solution: Ab Initio Modeling, Synthesis and Mechanical Properties. Acta Mater. 2014, 70, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, J.; Kobayashi, T.; Mukai, T.; Watanabe, H.; Suzuki, M.; Maruyama, K.; Higashi, K. The Activity of Non-Basal Slip Systems and Dynamic Recovery at Room Temperature in Fine-Grained AZ31B Magnesium Alloys. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 2055–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlen, J.; Yi, S.; Letzig, D.; Kainer, K.U. Effect of Rare Earth Elements on the Microstructure and Texture Development in Magnesium-Manganese Alloys during Extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 7092–7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samman, T.; Li, X. Sheet Texture Modification in Magnesium-Based Alloys by Selective Rare Earth Alloying. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 3809–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Yin, B.; Wu, Z.; Curtin, W.A. Designing High Ductility in Magnesium Alloys. Acta Mater. 2019, 172, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.U.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, S.H. Effects of Homogenization Time on Aging Behavior and Mechanical Properties of AZ91 Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 714, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyanwu, I.A.; Kamado, S.; Kojima, Y. Aging Characteristics and High Temperature Tensile Properties of Mg-Gd-Y-Zr Alloys. Mater. Trans. 2001, 42, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, D.; Tang, T.; Yu, D.; Xu, J.; Pan, F. Effect of Aging Treatment before Extrusion on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AZ80 Magnesium Alloy. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2017, 46, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, J.; Fu, G.; Zong, L.; Guo, B.; Yu, Y.; Su, Y.; Hao, Y. Different Precipitation Hardening Behaviors of Extruded Mg–6Gd–1Ca Alloy during Artificial Aging and Creep Processes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 715, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, S.H. Acceleration of Aging Behavior and Improvement of Mechanical Properties of Extruded AZ80 Alloy through (10–12) Twinning. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, H.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Gu, K.; Zhang, H. Nanocrystalline Microstructure in AZ91 Magnesium Alloy Prepared with Cryogenic Treatment. Key Eng. Mater. 2014, 575–576, 386–389. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.D.; Kumar, S.S. Effect of Heat Treatment Conditions and Cryogenic Treatment on Microhardness and Tensile Properties of AZ31B Alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 8786–8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, B.; Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Teng, J.; Chen, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, L.; Wu, Z. Investigation on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Hot-Rolled AZ31 Mg Alloy with Various Cryogenic Treatments. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 4557–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.R.; Wang, H.M.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, Y.T.; Wang, J.J.; Gill, S.P.A. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AZ91 Magnesium Alloy Subject to Deep Cryogenic Treatments. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2013, 20, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhale, P.; Shastri, H.; Mondal, A.K.; Masanta, M.; Kumar, S. Effect of Deep Cryogenic Treatment on Microstructure and Properties of AE42 Mg Alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2016, 25, 3590–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, E.; Zhang, H.; Ma, K.; Ai, C.; Gao, Q.; Lin, X. Effect of Deep Cryogenic Treatment on Microstructures and Performances of Aluminum Alloys: A Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 3661–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mónica, P.; Bravo, P.M.; Cárdenas, D. Deep Cryogenic Treatment of HPDC AZ91 Magnesium Alloys Prior to Aging and Its Influence on Alloy Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 239, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Hua, X.; Ren, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, J. Effect of Deep Cryogenic Treatment and Aging Treatment on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Mg7.5Li-3.5Zn-2Y Alloy Sheet. Foundry Technol. 2019, 40, 633–638. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Yang, G.; Liu, Z.; Fu, S.; Gao, H. Effects of Deep Cryogenic Treatment on Microstructure, Mechanical, and Corrosion of ZK60 Mg Alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 3686–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Z.; Xiong, X.; Qiu, W.; Chen, J.; Ren, X.; Lu, L. Influence of Ca Content on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Extruded Mg–Al–Ca–Mn Alloys. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2023, 36, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.T.; Zhang, X.D.; Zheng, M.Y.; Qiao, X.G.; Wu, K.; Xu, C.; Kamado, S. Effect of Ca/Al Ratio on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Mg-Al-Ca-Mn Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 682, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Jiang, X.; Sun, H.; Fang, Y.; Mo, D.; Li, X.; Shu, R. Effect Mechanism of Cryogenic Treatment on Ferroalloy and Nonferrous Alloy and Their Weldments: A Review. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Chen, X.; Pan, F.; Gao, S.; Zhao, D.; Liu, X. Effect of Sn Content on Strain Hardening Behavior of As-Extruded Mg-Sn Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 713, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Li, D.; Wu, H.; Miao, K.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, W.; Xu, C.; Geng, L.; Wu, P.; et al. Insights into the Deformation Mechanisms of an Al1Mg0.4Si Alloy at Cryogenic Temperature: An Integration of Experiments and Crystal Plasticity Modeling. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 200, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokkalingam, R.; Mishra, S.; Cheethirala, S.R.; Muthupandi, V.; Sivaprasad, K. Enhanced Relative Slip Distance in Gas-Tungsten-Arc-Welded Al0.5CoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloy. Met. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Met. Mater. Sci. 2017, 48, 3630–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Valle, J.A.; Carreño, F.; Ruano, O.A. Influence of Texture and Grain Size on Work Hardening and Ductility in Magnesium-Based Alloys Processed by ECAP and Rolling. Acta Mater. 2006, 54, 4247–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, B.; Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Ma, M.; Wang, L.; Qi, F. Effects of Cryogenic Treatment on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy Rolled at Different Paths. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 832, 142475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagnotto, M.; Ponge, D.; Demir, E.; Raabe, D. Orientation Gradients and Geometrically Necessary Dislocations in Ultrafine Grained Dual-Phase Steels Studied by 2D and 3D EBSD. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 2738–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A.; Field, D.P. Geometrically Necessary Dislocation Density Evolution in Interstitial Free Steel at Small Plastic Strains. Met. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Met. Mater. Sci. 2018, 49, 3274–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Cui, Y.; Bian, H.; Li, Q.; Chiba, A. Grain Refinement and Weak-Textured Structures Based on the Dynamic Recrystallization of Mg–9.80Gd–3.78Y–1.12Sm–0.48Zr Alloy. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Liu, C.; Gao, Y.; Han, X.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Z. Microstructure and Mechanical Anisotropy of the Hot Rolled Mg-8.1Al-0.7Zn-0.15Ag Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 701, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, P.G. The Crystallography and Deformation Modes of Hexagonal Close-Packed Metals. Metall. Rev. 1967, 12, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjas, J.; Roura, P. Modification of the Kolmogorov-Johnson-Mehl-Avrami Rate Equation for Non-Isothermal Experiments and Its Analytical Solution. Acta Mater. 2006, 54, 5573–5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Liu, H.; Yang, G.; Ma, M.; Jiang, B.; Jing, L.; Wang, X.; Tang, L.; Lu, L. Influence of Cryogenic Treatment Time on the Mechanical Properties of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy Sheets after Cross-Rolling. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 986, 174096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, C.C.; Li, P.J.; Huang, Z.Q.; Liu, P.T.; Xu, H.J.; Jia, W.T.; Ma, L.F. Effect of Cryogenic Time on Microstructure and Properties of TRCed AZ31 Magnesium Alloy Sheets Rolled during Cryogenic Rolling. Metals 2023, 13, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Y.; Liu, F.; Yang, N.; Zhai, X.B.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Ma, E.; Nie, J.F.; et al. Large Plasticity in Magnesium Mediated by Pyramidal Dislocations. Science 2019, 365, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S.; Reddy, S.T.; Majhi, J.; Nasker, P.; Mondal, A.K. Enhancing Mechanical Properties of Squeeze-Cast AZ91 Magnesium Alloy by Combined Additions of Sb and SiC Nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 799, 140341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, C.; Xin, Y.; Chapuis, A.; Huang, X.; Liu, Q. The Mechanism for the High Dependence of the Hall-Petch Slope for Twinning/Slip on Texture in Mg Alloys. Acta Mater. 2017, 128, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alloy Composition | Al | Ca | Mn | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designed content | 0.80 | 0.2 | 0.20 | Bal. |

| Actual content (Mean ± SD) | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | Bal. |

| TYS (MPa) | UTS (MPa) | εf (%) | HV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAT | 230 ± 5.0 | 290 ± 4.0 | 26.0 ± 1.0 | 72.8 ± 0.8 |

| SCAT-0.5 h | 250 ± 3.5 | 320 ± 4.0 | 28.2 ± 0.9 | 73.5 ± 0.6 |

| SCAT-1 h | 272 ± 2.5 | 332 ± 6.0 | 27.7 ± 0.5 | 75.4 ± 1.0 |

| SCAT-12 h | 280 ± 4.0 | 343 ± 5.0 | 27.3 ± 1.2 | 79.0 ± 1.0 |

| SCAT-24 h | 285 ± 2.5 | 345 ± 3.0 | 25.8 ± 0.8 | 78.5 ± 0.7 |

| SCAT-48 h | 288 ± 4.5 | 348 ± 4.5 | 25.2 ± 0.5 | 79.5 ± 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fouad, M.; Nakata, T.; Xu, C.; Zuo, J.; Wu, Z.; Geng, L. Effect of Deep Cryogenic Treatment on Aging Strength of Mg–Al–Ca–Mn Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 4769. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204769

Fouad M, Nakata T, Xu C, Zuo J, Wu Z, Geng L. Effect of Deep Cryogenic Treatment on Aging Strength of Mg–Al–Ca–Mn Alloy. Materials. 2025; 18(20):4769. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204769

Chicago/Turabian StyleFouad, Mohamed, Taiki Nakata, Chao Xu, Jing Zuo, Zelin Wu, and Lin Geng. 2025. "Effect of Deep Cryogenic Treatment on Aging Strength of Mg–Al–Ca–Mn Alloy" Materials 18, no. 20: 4769. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204769

APA StyleFouad, M., Nakata, T., Xu, C., Zuo, J., Wu, Z., & Geng, L. (2025). Effect of Deep Cryogenic Treatment on Aging Strength of Mg–Al–Ca–Mn Alloy. Materials, 18(20), 4769. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204769