Advances in High-Voltage Power Electronics Using Ga2O3-Based HEMT: Modeling

Abstract

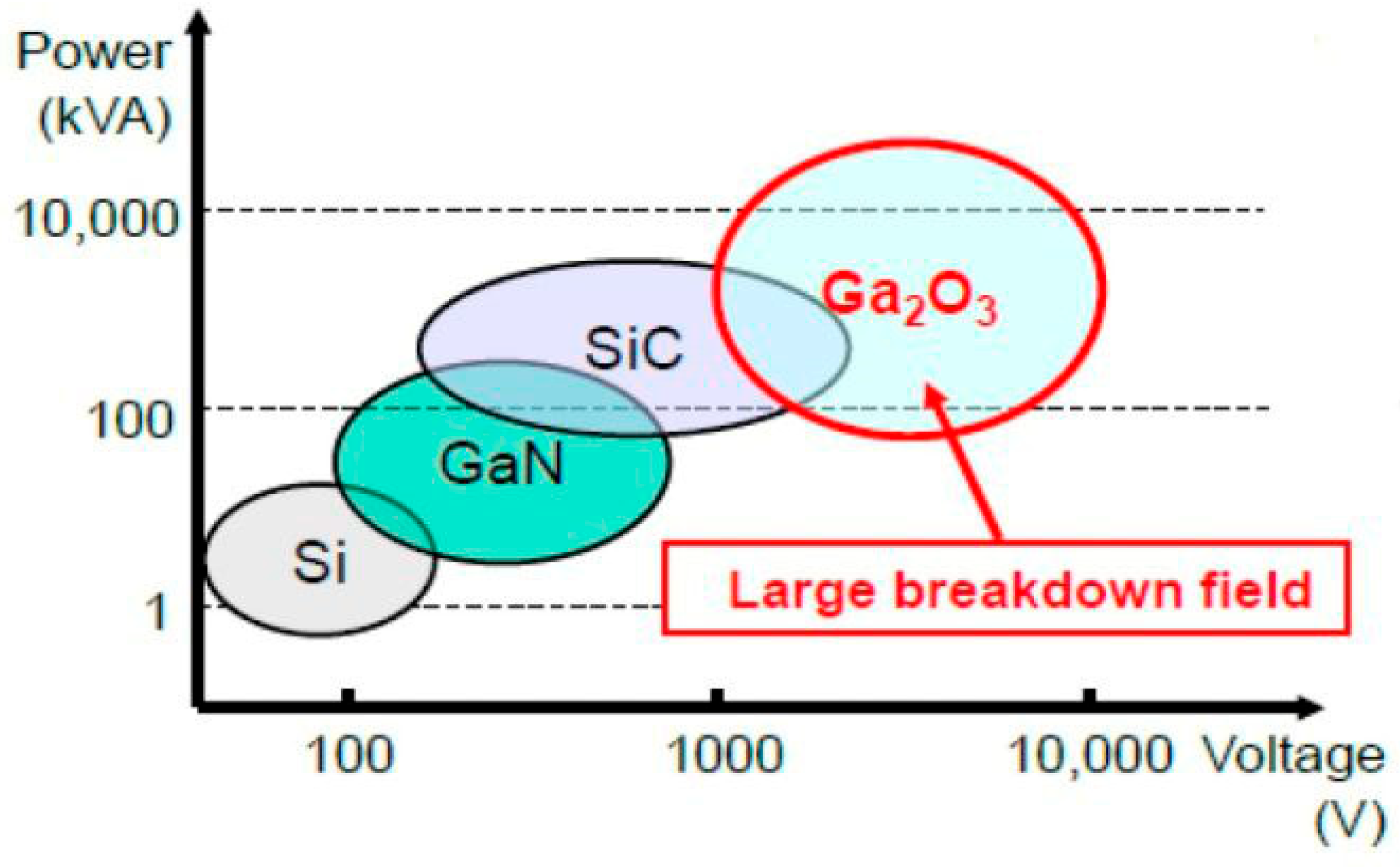

1. Introduction

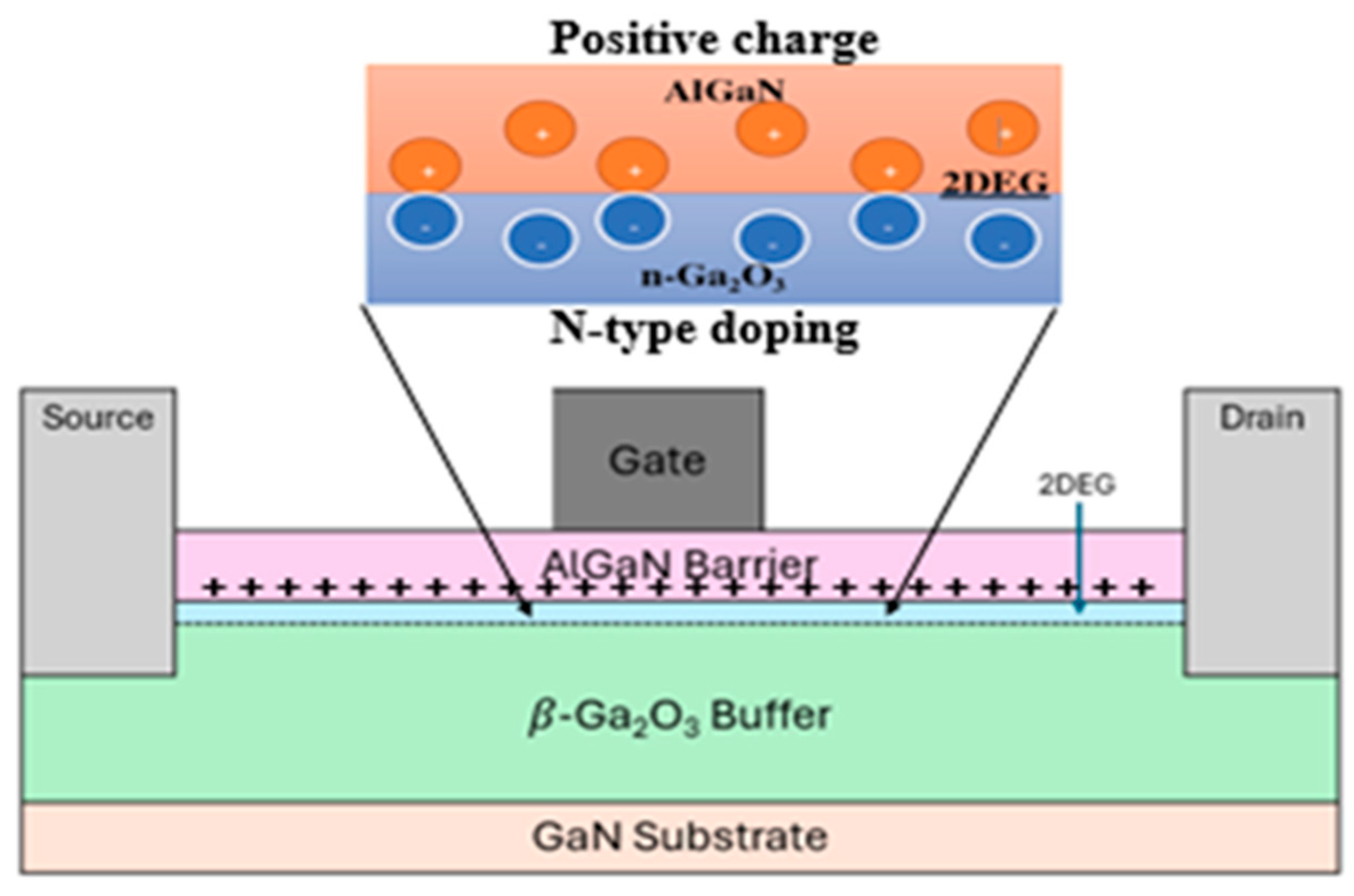

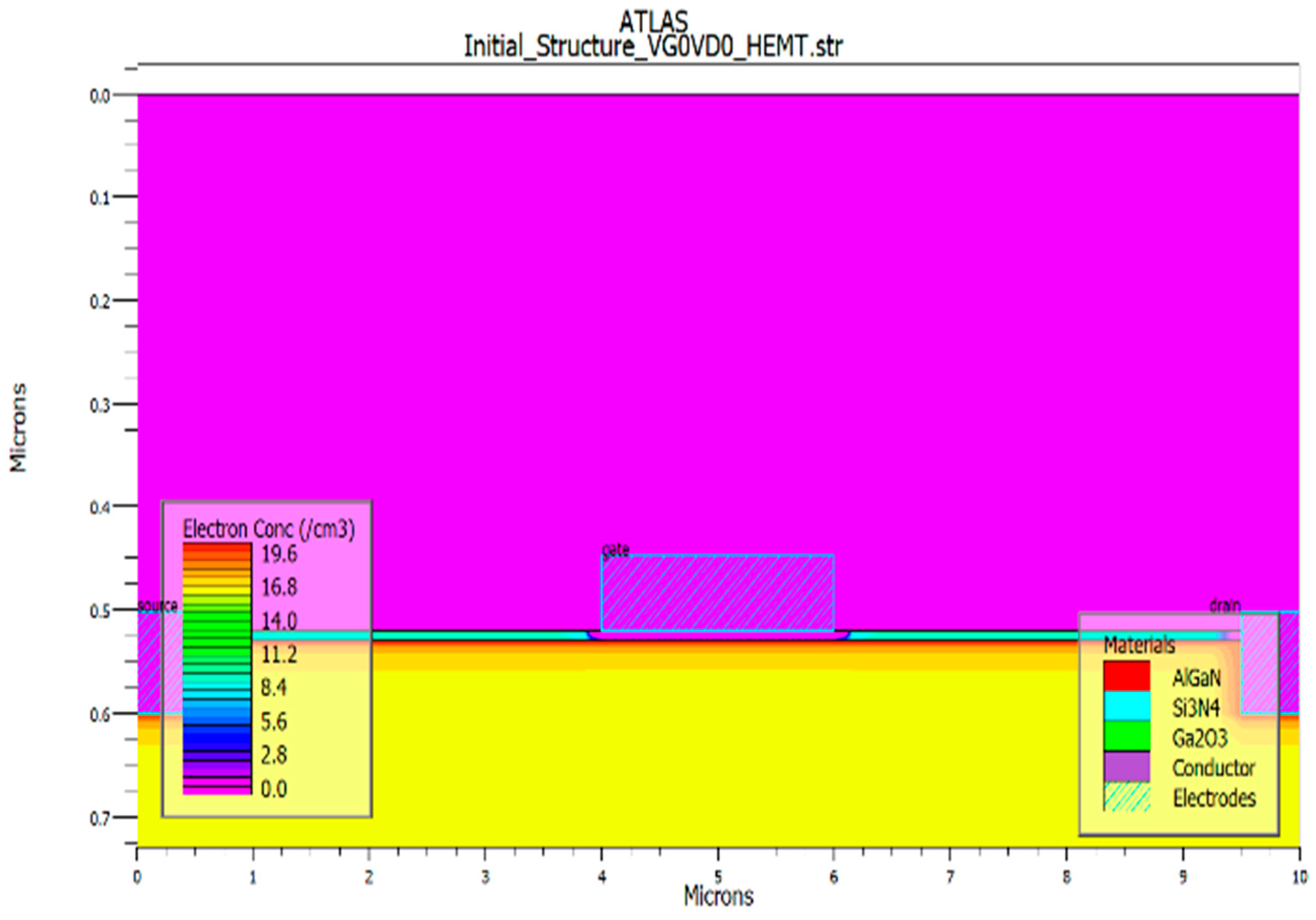

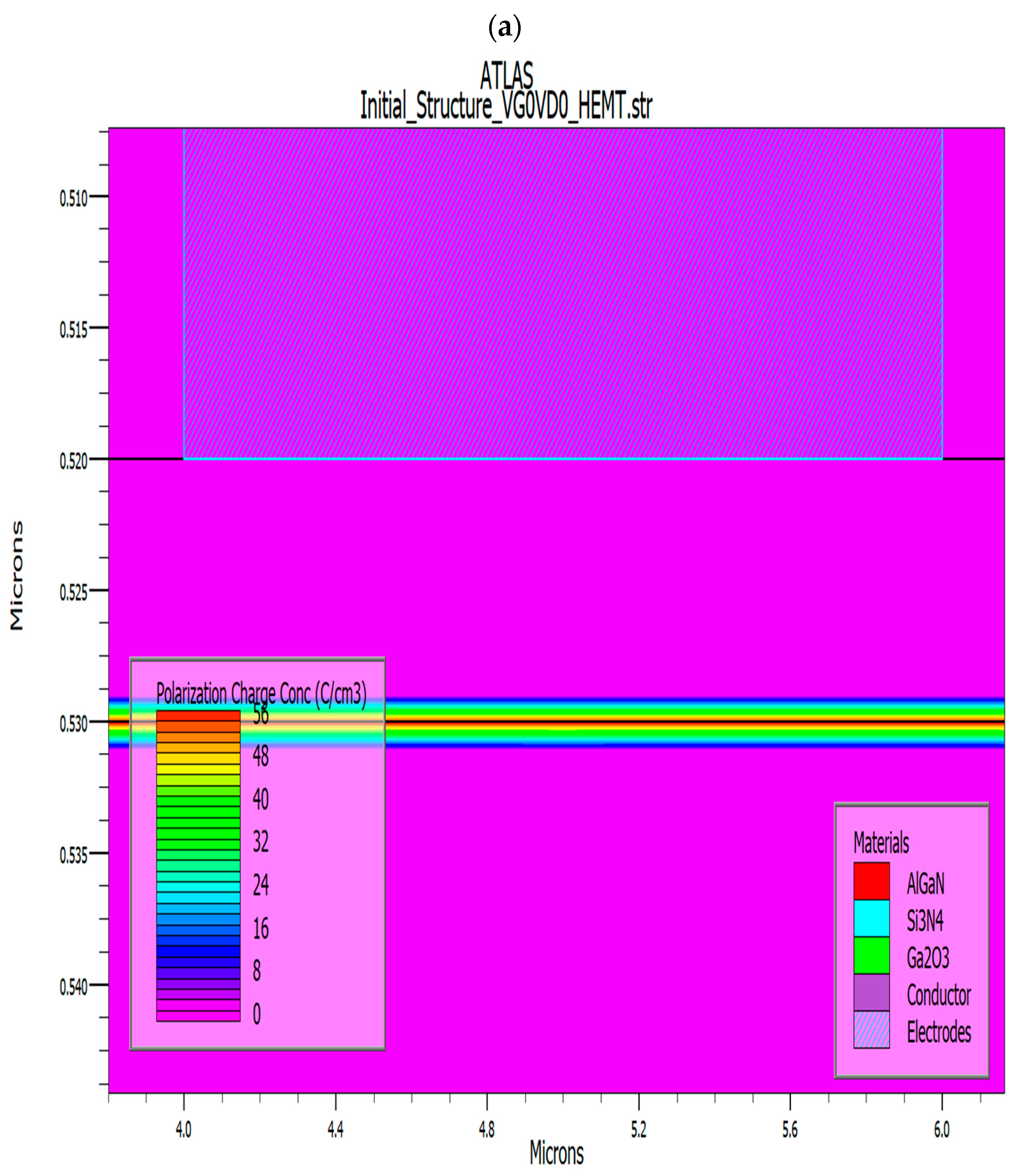

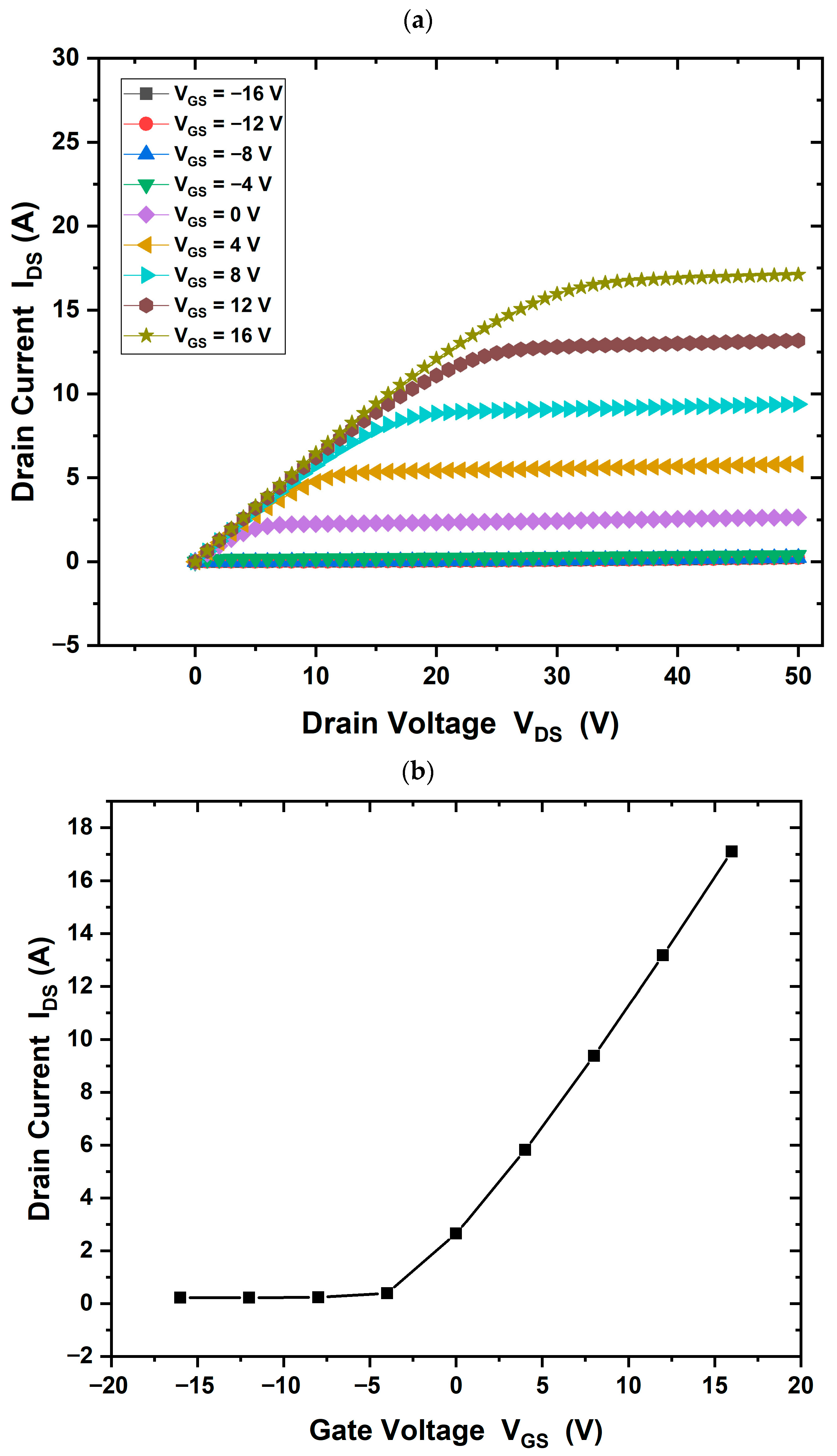

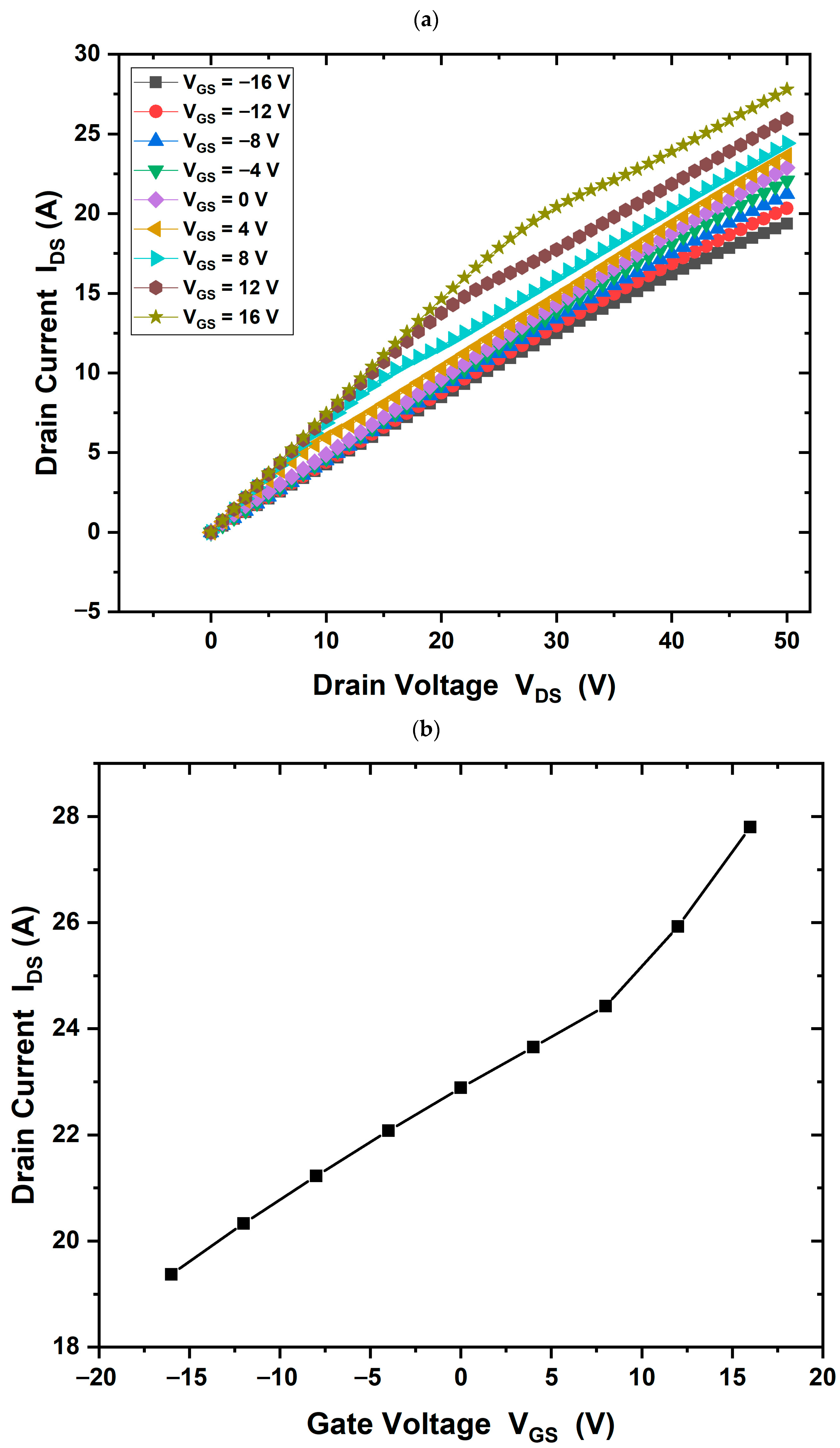

2. Methodologies

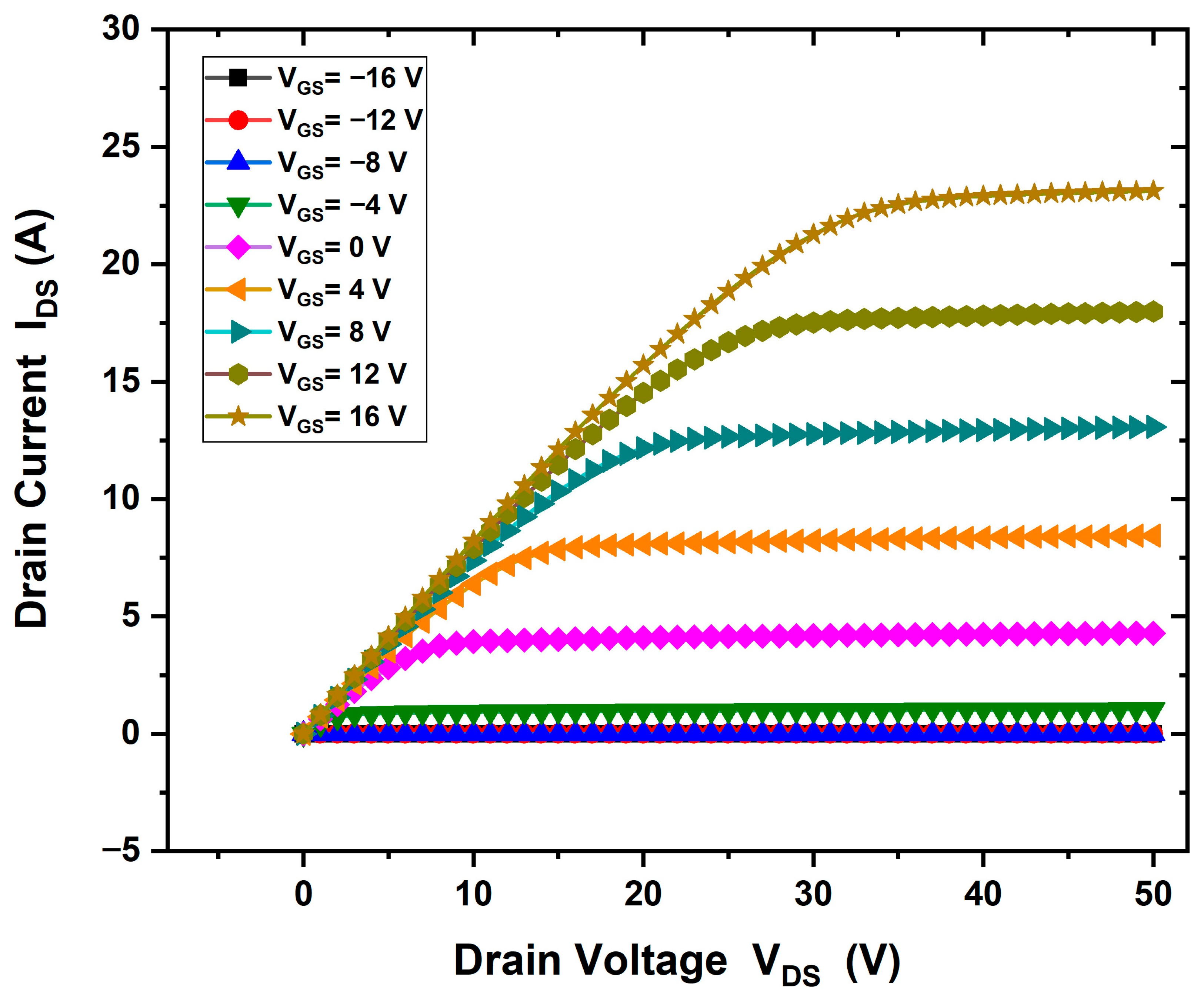

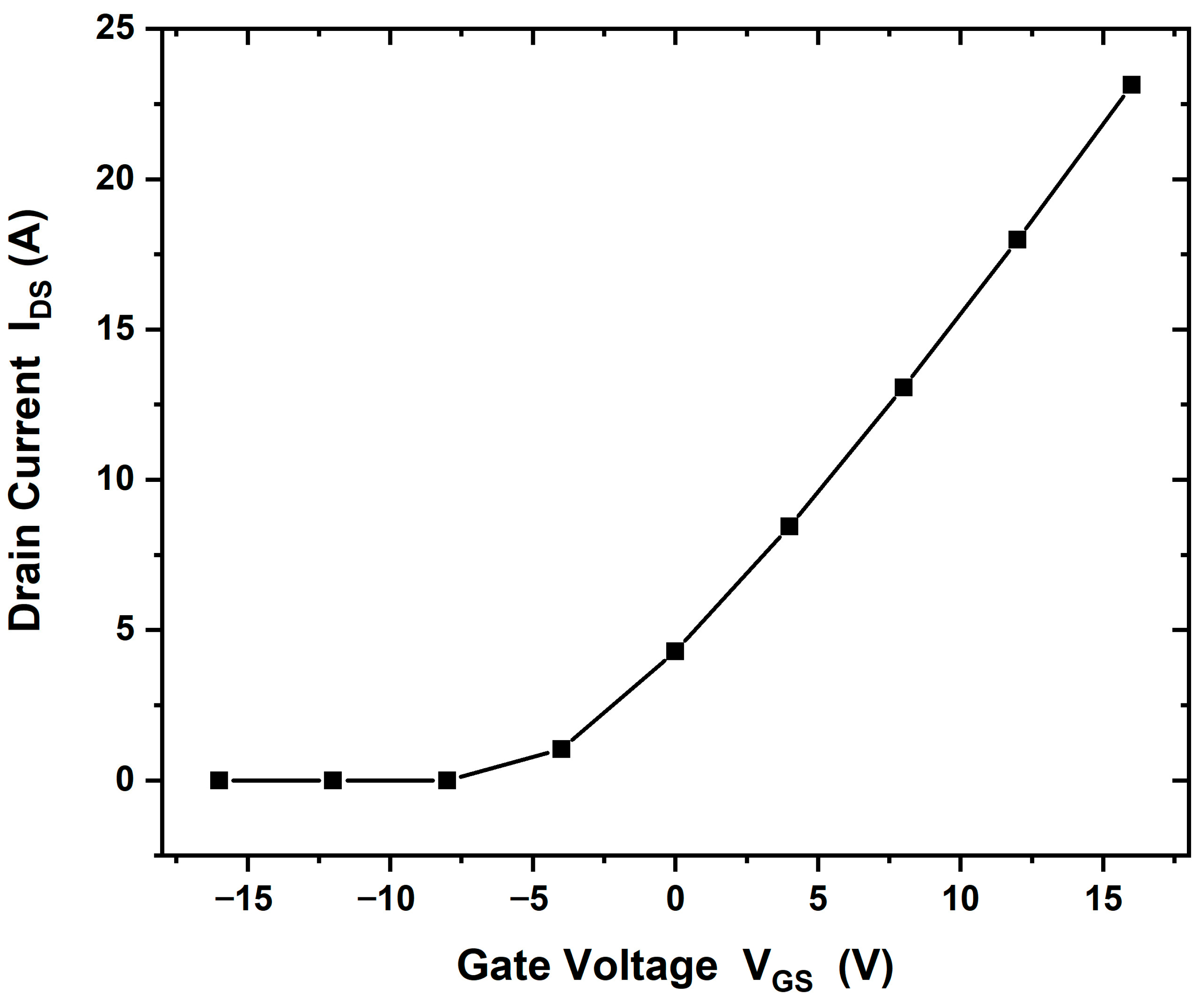

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pearton, S.J.; Yang, J.; Cary, P.H., IV; Ren, F.; Kim, J.; Tadjer, M.J.; Mastro, M.A. A review of Ga2O3 materials, processing, and devices. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2018, 5, 011301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, R.; Murugapandiyan, P.; Vigneshwari, N.; Mohanbabu, A.; Ravi, S. Investigation of different buffer layer impact on AlN/GaN/AlGaN HEMT using silicon carbide substrate for high-speed RF applications. Micro Nanostruct. 2024, 189, 207815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revathy, A.; Thangam, R.; Haripriya, D.; Maheswari, S.; Murugapandiyan, P. Ultra-scaled 55 nm InAlN/InGaN/GaN/AlGaN HEMT on β-Ga2O3 substrate: A TCAD-Based performance analysis for high-frequency power applications. Micro Nanostruct. 2025, 204, 208169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makeswaran, N.; Battu, A.K.; Swadipta, R.; Manciu, F.S.; Ramana, C.V. Spectroscopic characterization of the electronic structure, chemical bonding, and band gap in thermally annealed polycrystalline Ga2O3 thin films. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, Q3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Sekiya, T.; Miyokawa, N.; Watanabe, N.; Kimoto, K.; Ide, K.; Kamiya, T. Conversion of an ultra-wide bandgap amorphous oxide insulator to a semiconductor. NPG Asia Mater. 2017, 9, e359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, S.; Li, K.; Chen, X.; Shan, C. Bandgap engineering of Gallium oxides by crystalline disorder. Mater. Today Phys. 2021, 18, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Swenson, B.L.; Wong, M.H.; Mishra, U.K. Current status and scope of gallium nitride-based vertical transistors for high-power electronics application. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2015, 30, 034003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, J.; Godignon, P.; Perpina, X.; Perez-Tomas, A.; Rebollo, J. A survey of wide bandgap power semiconductor devices. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 29, 2155–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Wei, M.; Yu, R.; Ohta, H.; Katayama, T. Significant suppression of cracks in freestanding perovskite oxide flexible sheets using a capping oxide layer. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 21013–21019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibe, T.; Tomeda, A.; Komatsubara, Y.; Kitaura, R.; Uenuma, M.; Uraoka, Y.; Nakamura, Y. Carrier and phonon transport control by domain engineering for high-performance transparent thin film thermoelectric generator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 151601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, L. Tuning Electrical and Optical Properties of SnO2 Thin Films by Dual-Doping Al and Sb. Coatings 2025, 15, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashiwaki, M.; Sasaki, K.; Kuramata, A.; Masui, T.; Yamakoshi, S. Gallium oxide (Ga2O3) transistors: A review of current status and future prospects. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2016, 31, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Chabak, K.D.; Baldini, M.; Moser, N.; Gilbert, R.C.; Fitch, R.C.; Wagner, G.; Galazka, Z.; Mccandless, J.; Crespo, A.; et al. β-Ga2O3 MOSFETs for radio frequency operation. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 2016, 37, 902–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, H. Increased thermal conductivity of β-Ga2O3 using AI substitution: Full spectrum phonon engineering. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 137, 105701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, W.; Zhang, X. Extremely low thermal conductivity of β-Ga2O3 with high temperature stability. J. App. Phys. 2021, 130, 115103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kaneko, K.; Fujita, S. Homoepitaxial growth of beta Ga2O3 films by mist chemical vapor deposition. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 55, 1202B8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, K.; Mori, Y.; Masumoto, K.; Murakami, H.; Imabayashi, H.; Takazawa, Y.; Todoroki, Y. Monitoring of Ga-Na melt electrical resistance and its correlation with crystal growth on the Na Flux method. Appl. Phys. Express 2019, 12, 065502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, B. Growth and characterization of 2-inch (-102) plane of β-Ga2O3 crystal by edge-defined film-fed growth method. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 2025, 27, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Alhasan, R.; Yabe, T.; Iyama, Y.; Oi, N.; Imanishi, S.; Nguyen, Q.; Kawarada, H. An Enhanced Two-Dimensional Hole Gas (2DHG) C-H Diamond with Positive Surface Charge Model for Advanced Normally-Off MOSFET Devices. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; He, Q.; Jiang, G.; Shi, L.; Pang, T.; Liu, M. An overview of the ultrawide bandgap Ga3O3 semiconductor-based Schottky barrier diode for bower electronis application. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 4137–4154. [Google Scholar]

- Amano, H.; Baines, Y.; Beam, E.; Borga, M.; Bouchet, T.; Chalker, P.R.; Zang, Y. Wide bandgap semiconductor devices. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 163001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Rao, G.P.; Lenka, T.R.; Prasad, S.V.S.; Boukortt, N.E.I.; Crupi, G.; Nguyen, H.P.T. Design and simulation of T-gate AlN/β-Ga2O3 HEMT for DC, RF and high-power nanoelectronics switching applications. Int. J. Numer. Model. Electron. Netw. Devices Fields 2024, 37, e3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, T.R.; Rahman, T.; Muthu, M.; Emu, I.H.; Nguyen, H. A novel AlN/β-Ga2O3 high electron mobility transistor with 2 kV and 600 GHz operation. Microsyst. Technol. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, A.; Pal, P.; Kabra, S. Performance enhancement of asymmetric gate graded-AlGaN/GaN HEMT on β-Ga2O3 substrate for RF applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 321, 118514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthiga, R.; Ravi, S.; Manasa, B.M.R.; Sivamani, C.; Vinodhkumar, N. Exploring progress in β-(AlxGa1-x)2O3/β-Ga2O3 heterojunction technology: A critical analysis of emerging power electronics and high-frequency applications. Micro Nanostruct. 2025, 207, 208289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, H.; Zou, X.; Lau, K.M.; Wang, G. Vertical β-Ga2O3 Schottky barrier diodes with enhanced breakdown voltage and high switching performance. Phys. Status Solidi A 2020, 3, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Cui, J.; Liang, T.; Yang, L.; Xu, K.; Liu, J.; Zhai, T. Solar-blind ultraviolet photodetectors based on wide bandgap semiconductors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2107214. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, G.; Liu, Z.; Tang, K.; Sha, S.; Li, L.; Tan, C.; Guo, Y.; Tang, W. Highly responsivity and fast-response 8×8 β-Ga2O3 solar-blind ultraviolet imagimg photodetector array. Sci. Chain Tecnol. Sci. 2023, 66, 3259–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Kurashima, Y.; Matsumae, T. Room-temperature wafer bonding using in-situ Si thin films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 57, 05FA05. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, A.; Tsuchiya, T.; Ueno, K.; Fujita, S.; Fujita, S. Low-temperature deposition of amorphous Ga2O3 films and application to flexible electronics. J. Mater. Chem. 2018, 6, 3132–3137. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H. Growth and characterization of β-Ga2O3 epitaxial films on various substrates by MOCVD. CrystEngComm 2019, 21, 5161–5168. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Pulsed laser deposition of β-Ga2O3 thin films on different substrates. Thin Solid Film. 2012, 520, 3895–3900. [Google Scholar]

- SILVACO Int. ATLAS User’s Manual; Device Simulation Software: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Usseinov, A.; Platonenko, A.; Koishybayeva, Z.; Akilbekov, A.; Zdorovets, M.; Popov, A.I. Pair vacancy defects in β-Ga2O3 crystal: Ab initio study. Opt. Mater. X 2022, 16, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Liu, T. Formation and Transport of Polarons in β-Ga2O3: An Ab Initio Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 8464–8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Niu, J.; Bai, L.; Jing, X.; Gao, D.; Deng, J.; Wang, W. Preparation of β-Ga2O3/ε-Ga2O3 type II phase junctions by atmospheric pressure chemical vapor deposition. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 10395–10401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Xu, W.; Gong, H.; You, T.; Han, G. Gallium oxide (Ga2O3) heterogeneous and heterojunction power devices. Fundam. Res. 2025, 5, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmala Devi, K.; Keerthiga, G.; Ravi, S.; Murugapandiyan, P. High-performance GaN-based HEMTs with β-Ga2O3 buffer layer engineering for millimeter-wave applications. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2025, 87, 787–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safieddine, F.; Hassan, F.E.H.; Kazan, M. Theoretical investigation of the thermal conductivity of Ga2O3 polymorphs. Solid State Commun. 2024, 394, 115715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkov, A.; Mishra, A.; Cattelan, M.; Field, D.; Pomeroy, J.; Kuball, M. Electrical and thermal characterisation of liquid metal thin-film Ga2O3–SiO2 heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ranga, P.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Huang, H.L.; Santia, M.D.; Choi, S. Thermal conductivity of β-phase Ga2O3 and (AlxGa1–x)2O3 heteroepitaxial thin films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 38477–38490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwejkowski, C.J.; Creange, N.C.; Sun, K.; Giri, A.; Donovan, B.F.; Constantin, C.; Hopkins, P.E. Size effects in the thermal conductivity of gallium oxide (β-Ga2O3) films grown via open-atmosphere annealing of gallium nitride. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 117, 084308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Montgomery, R.; Mauze, A.; Shi, J.; Graham, S. Thermal management of β-Ga2O3 current aperture vertical electron transistors. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 11, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Song, X.; Hu, Z.; Tian, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Fenf, Q.; Zhou, H.; et al. Demonstration of the normally off β-Ga2O3 MOSFET with high threshold voltage and high current density. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 123, 193501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhara, S.; Kalarickal, N.K.; Dheenan, A.; Rahman, S.I.; Joishi, C.; Rajan, S. β-Ga2O3 trench Schottky barrier diodes by novel low-damage Ga-flux etching. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.04870. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, H.; Lu, X. Ga2O3 vertical FinFETs with integrated Schottky barrier diode for low power application high. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2024, 71, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Li, Q.; Xia, G.; Yu, H. Modeling, simulations, and optimizations of gallium oxide on gallium-nitride Schottky barrier diodes. Chin. Physics B 2021, 30, 027301. [Google Scholar]

- Sze, S.M.; Li, Y.; Ng, K.K. Physics of Semiconductor Devices; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Swinnich, E.; Seo, J. Investigation of Thermal Properties of β-Ga2O3 Nanomembranes on Diamond Heterostructure Using Raman Thermometry. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 055007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinselman, K.; Walker, P.; Norman, A.G.; Parilla, P.; Ginley, D.S.; Zakutayev, A. Performance and reliability of β-Ga2O3 Schottky barrier diodes at high temperature. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2021, 39, 040402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layer | Material | Thickness (nm) | Doping Concentration (cm−3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barrier layer | AlGaN | 10 | Undoped |

| Buffer layer | -Ga2O3 | 200 | n-type 1 × 1018 cm−3 |

| Substrate | GaN | 1200 | p-type 1 × 1017 cm−3 |

| Substrate | SiC | 1200 | Undoped |

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

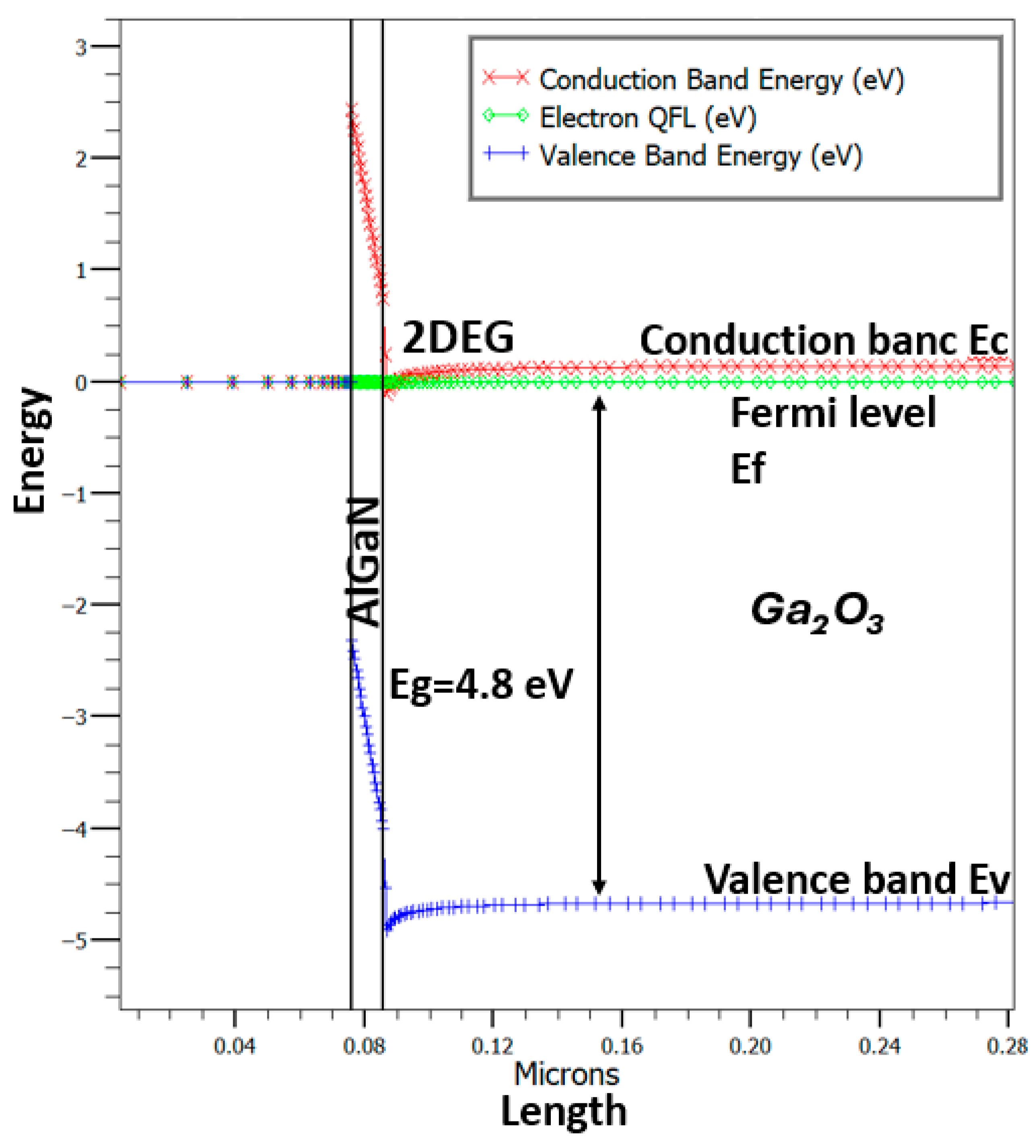

| -Ga2O3 Bandgap | Eg | eV | 4.8 |

| Permittivity | ɛr | - | 10 |

| Effective conduction band density of state | nc300 | cm−3 | 3.72 × 1018 |

| Effective valence band density of state | nv300 | cm−3 | 3.72 × 1018 |

| Electron mobility in the surface region | μn | s | 118 cm−2/Vs |

| Hole mobility in the surface region | μp | s | 50 cm−2/Vs |

| Electron affinity | EA | eV | 4.0 |

| Contact gate work function | WFg | eV | 5 |

| Contact drain and source | WFd | eV | 3.93 |

| Interface sheet charge Qf (positive) | Qf | cm−2 | 1 × 1010 |

| Structural Aspect | Included | How It Is Modelled in Silvaco TCAD |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed interface charge | Yes | interface with qf = 1 × 1010 |

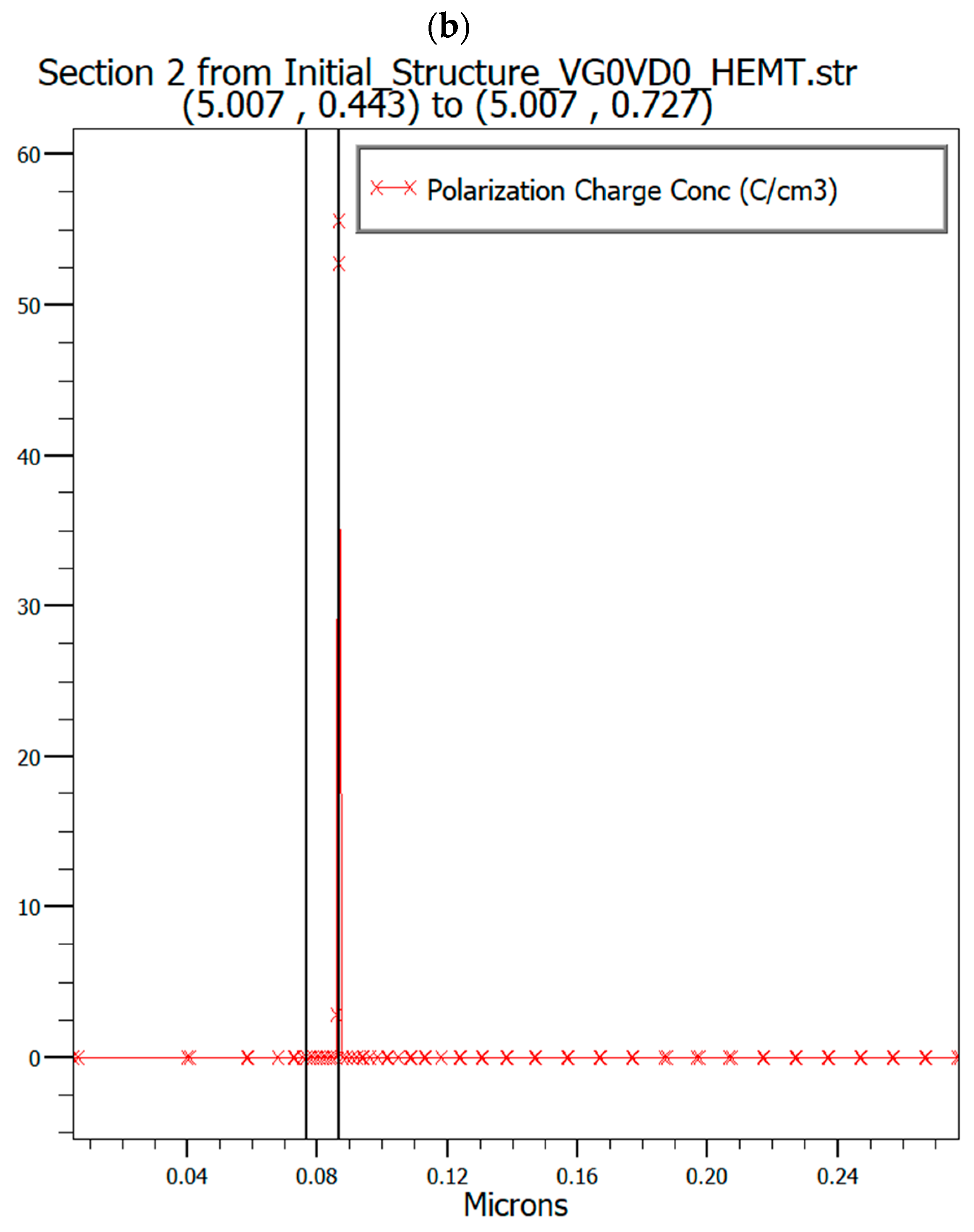

| Polarization and strain | Yes | model polarization calc.strain |

| Basic material structure | Yes | custom material definitions |

| SRH recombination | Yes | models srh |

| Carrier mobility | Partial | tmun |

| Traps/defects | Yes | maxtrap = 20 |

| Interface traps | Yes | defined |

| Thermal effects | Yes | low thermal conductivity input for Ga2O3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhasani, R.; Hussain, H.; Alkhamisah, M.A.; Hiazaa, A.; Alharbi, A. Advances in High-Voltage Power Electronics Using Ga2O3-Based HEMT: Modeling. Materials 2025, 18, 4770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204770

Alhasani R, Hussain H, Alkhamisah MA, Hiazaa A, Alharbi A. Advances in High-Voltage Power Electronics Using Ga2O3-Based HEMT: Modeling. Materials. 2025; 18(20):4770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204770

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhasani, Reem, Hadba Hussain, Mohammed A. Alkhamisah, Abdulrhman Hiazaa, and Abdullah Alharbi. 2025. "Advances in High-Voltage Power Electronics Using Ga2O3-Based HEMT: Modeling" Materials 18, no. 20: 4770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204770

APA StyleAlhasani, R., Hussain, H., Alkhamisah, M. A., Hiazaa, A., & Alharbi, A. (2025). Advances in High-Voltage Power Electronics Using Ga2O3-Based HEMT: Modeling. Materials, 18(20), 4770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204770