Characterization of Bricks from Baroque Monuments in Northeastern Poland: A Comparative Study of Hygric Behavior and Microstructural Properties for Restoration Applications

Highlights

- Physical, hygric, and mechanical properties of Baroque bricks were investigated

- Knowledge of historical masonry systematized to support effective restoration

- Relationship identified between moisture transport and bricks microstructure

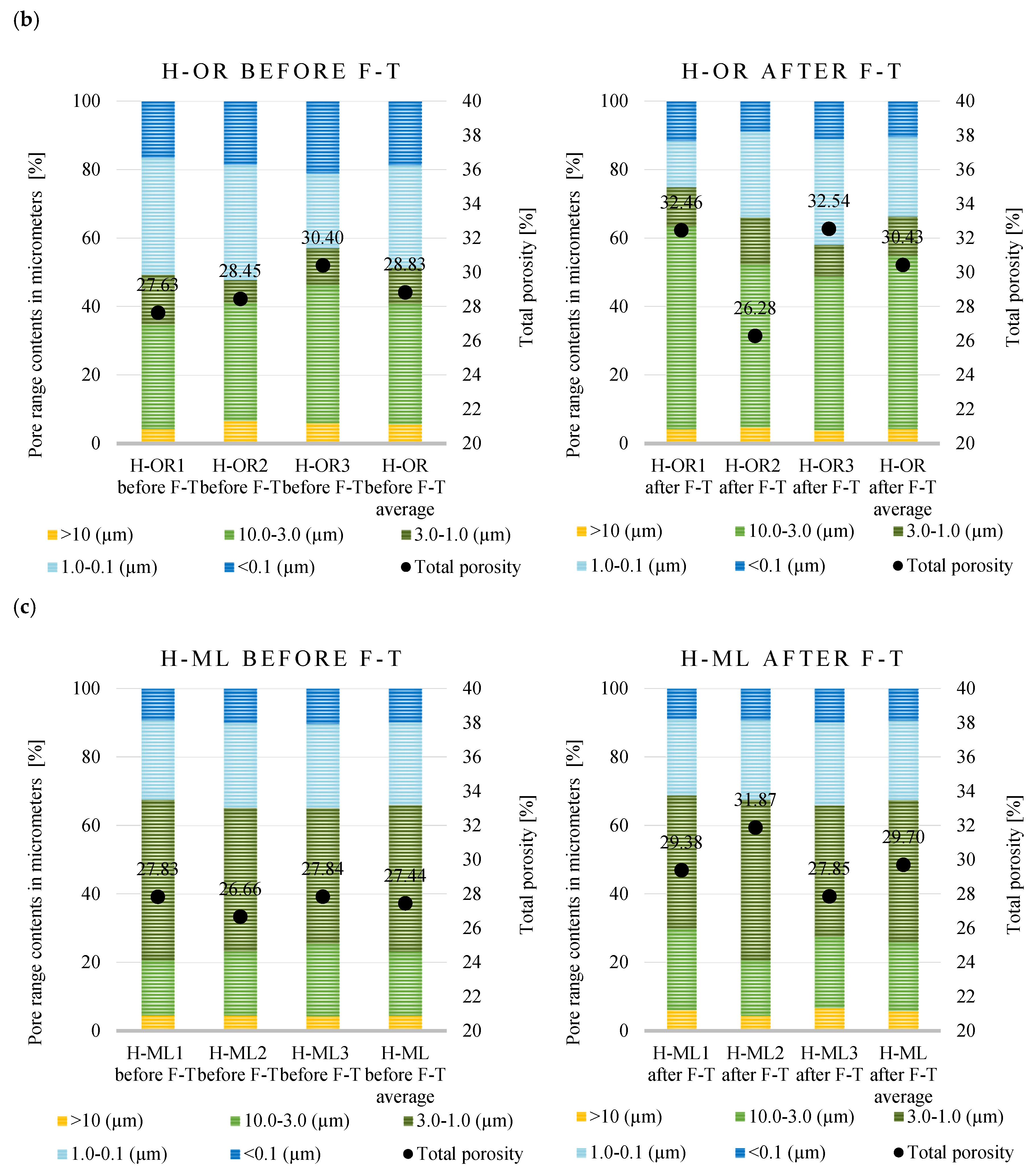

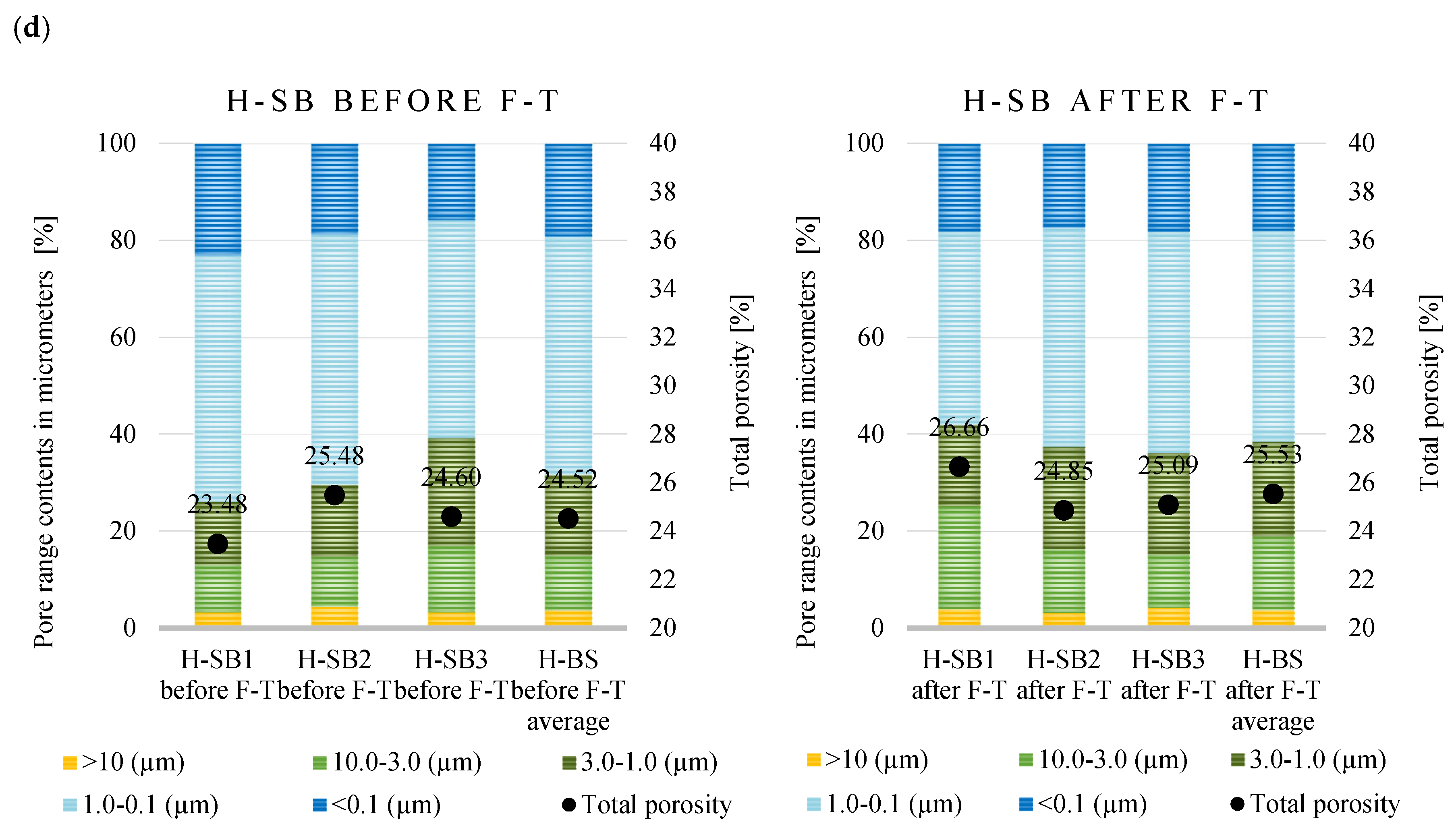

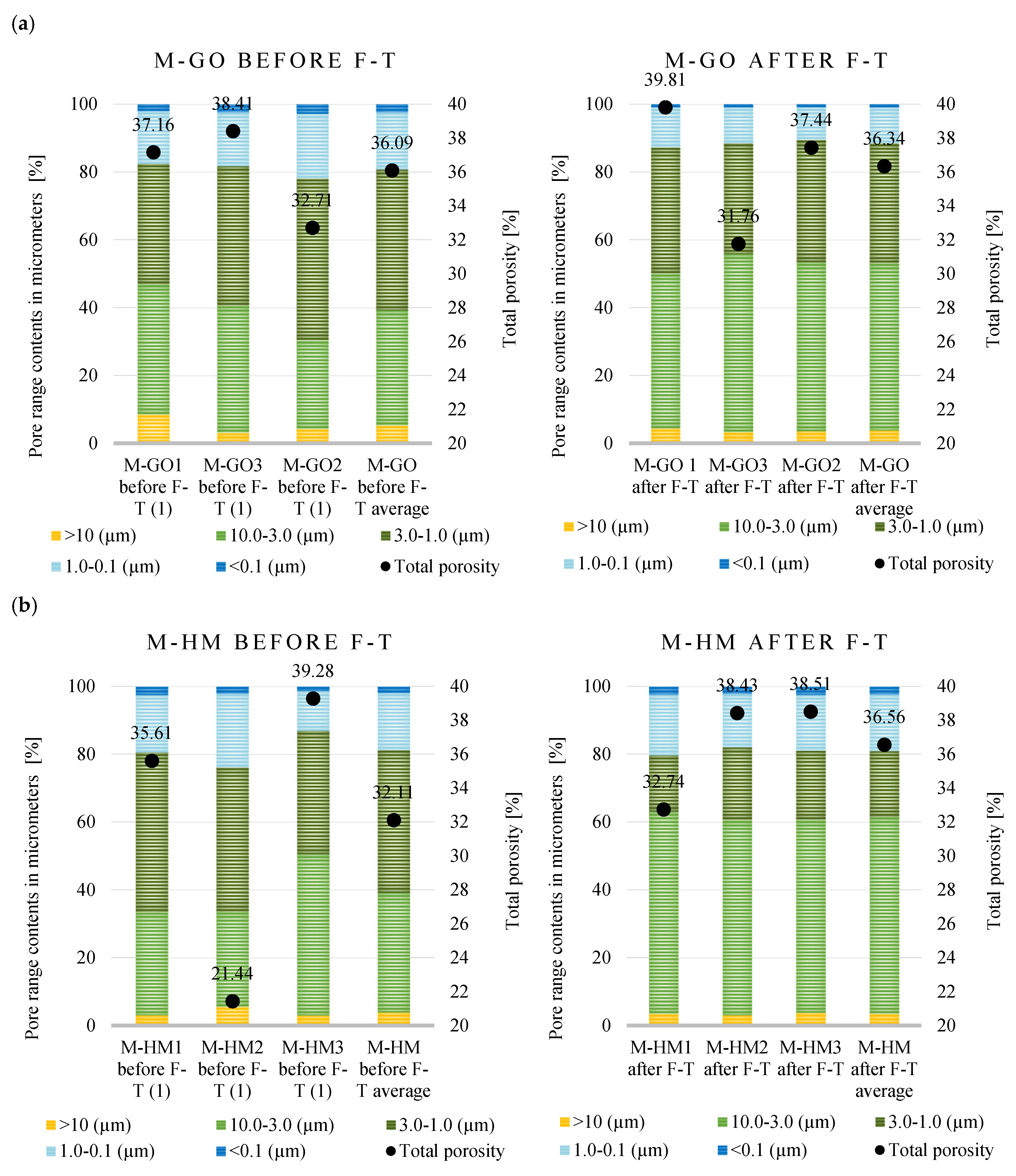

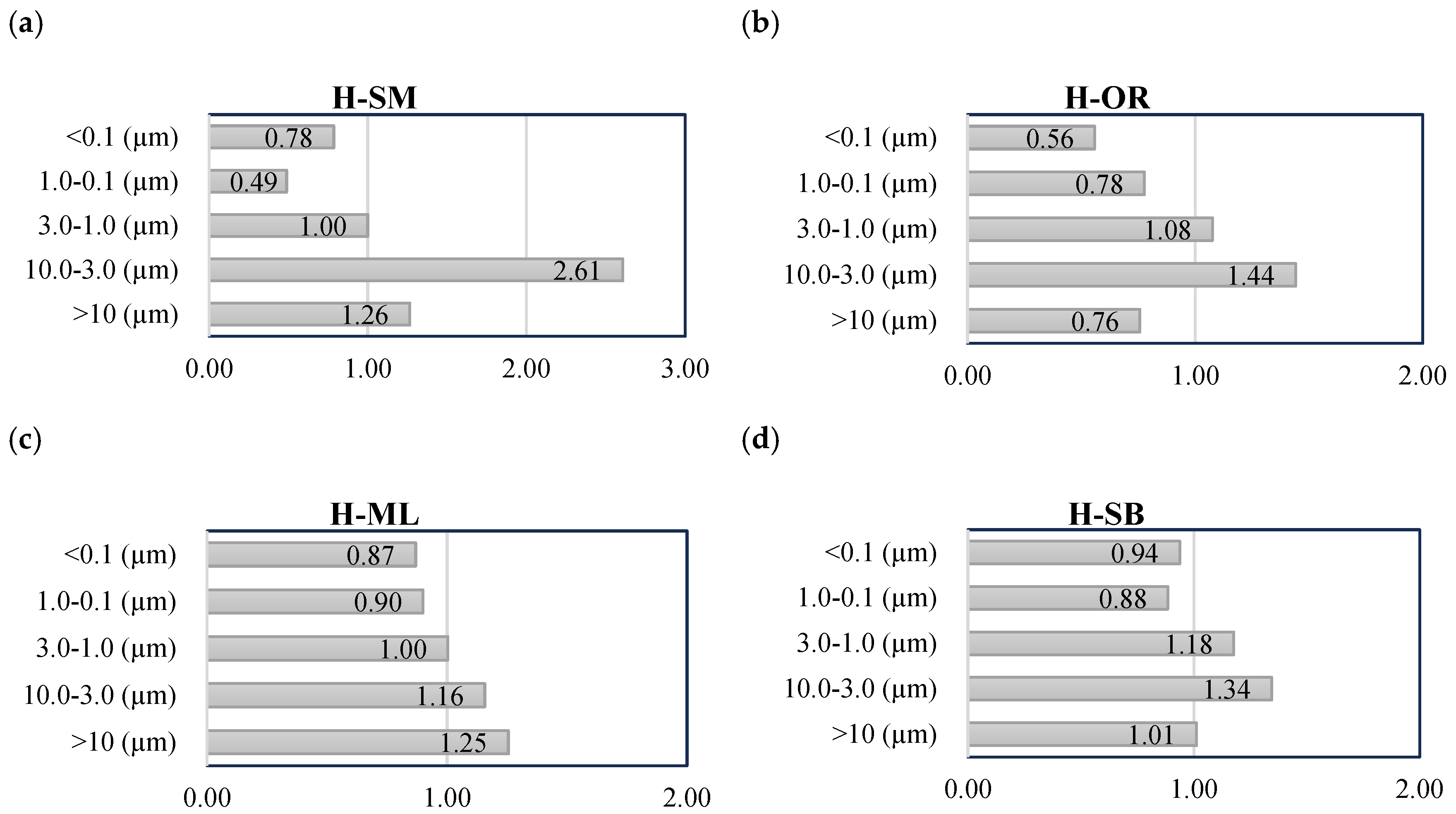

- Freeze–thaw cycles cause repeatable changes in brick microstructure

- Porosity transformation factor introduced to assess durability of historic bricks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To conduct a detailed characterization of the physical, hygric, microstructural, and mechanical properties of Baroque bricks from the 18th and 19th centuries.

- To assess the compatibility between modern restoration bricks and their historical counterparts based on key technical parameters, including porosity, water absorption, compressive strength, and freeze–thaw resistance.

- To develop preliminary guidelines for selecting contemporary restoration materials that align with conservation requirements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Materials

- −

- The Synagogue in Barczewo (Figure 1a): Established in 1847, this two-story, rectangular brick building is the only preserved former synagogue in the Olsztyn district. Its sale to private owners in 1937 contributed to its preservation, as it remained undamaged during Kristallnacht. The structure was constructed in the Neoclassical style, featuring a decorative façade articulated by pilasters and large, semicircular-arched windows.

- −

- The Church of the Holy Cross and Our Lady of Sorrows in Międzylesie (Figure 1b): This Baroque church was constructed from stone and brick between 1752 and 1753 by rebuilding a small 1722 chapel, preserving some of the original walls. Side towers were added in 1755, and a perimeter wall with four corner chapels was completed by 1775. Its distinct features include a triangular bell-shaped gable, a masonry turret for the sanctus bell, and a sundial.

- −

- The Bishop’s Palace in Smolajny (Figure 1c): Situated on a high escarpment along the Łyna River, on the site of a former fortified manor. Constructed between 1741 and 1743 at the behest of Bishop Adam Stanisław Grabowski, the building served as a summer residence for the Bishops of Warmia. Designed in the Baroque style, it is a masonry structure with plastered surfaces, characterized by architectural simplicity enhanced with numerous decorative elements. The palace has a slightly elongated rectangular layout, comprises two stories, and is topped with a hipped roof covered with red ceramic tiles.

- −

- The monastery building in Orneta (Figure 1d): Situated within the defensive walls of the historic town, along the southeastern bend of Olsztyńska Street. The convent of the Sisters of St. Catherine was founded at this location in 1581 by Bishop Marcin Kromer. Archival records from 1565 and 1581 refer to the building as an older structure comprising ten cells. Prior to 1586, it underwent complete reconstruction and was adapted to accommodate the needs of the newly established convent. The edifice is a four-winged masonry structure with plastered facades, arranged around a rectangular internal courtyard. The front wing, on the western side, has walls and cellars dating back to 1586. The remaining wings date from 1776, with the southern wing constructed on the former defensive wall.

2.2. Description of Testing Methods

2.2.1. Physical Characterization

2.2.2. Mineralogical Composition and Thermal Gravimetric Analysis

2.2.3. Microstructure Studies: Microscopy and Mercury Porosimetry Method (MIP)

2.2.4. Hygric Characterization

2.2.5. Compressive Strength Tests

2.2.6. Freezing and Thawing Resistance

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Physical and Geometric Properties

3.2. Mineralogical and Chemical Composition

3.3. Microstructure Studies

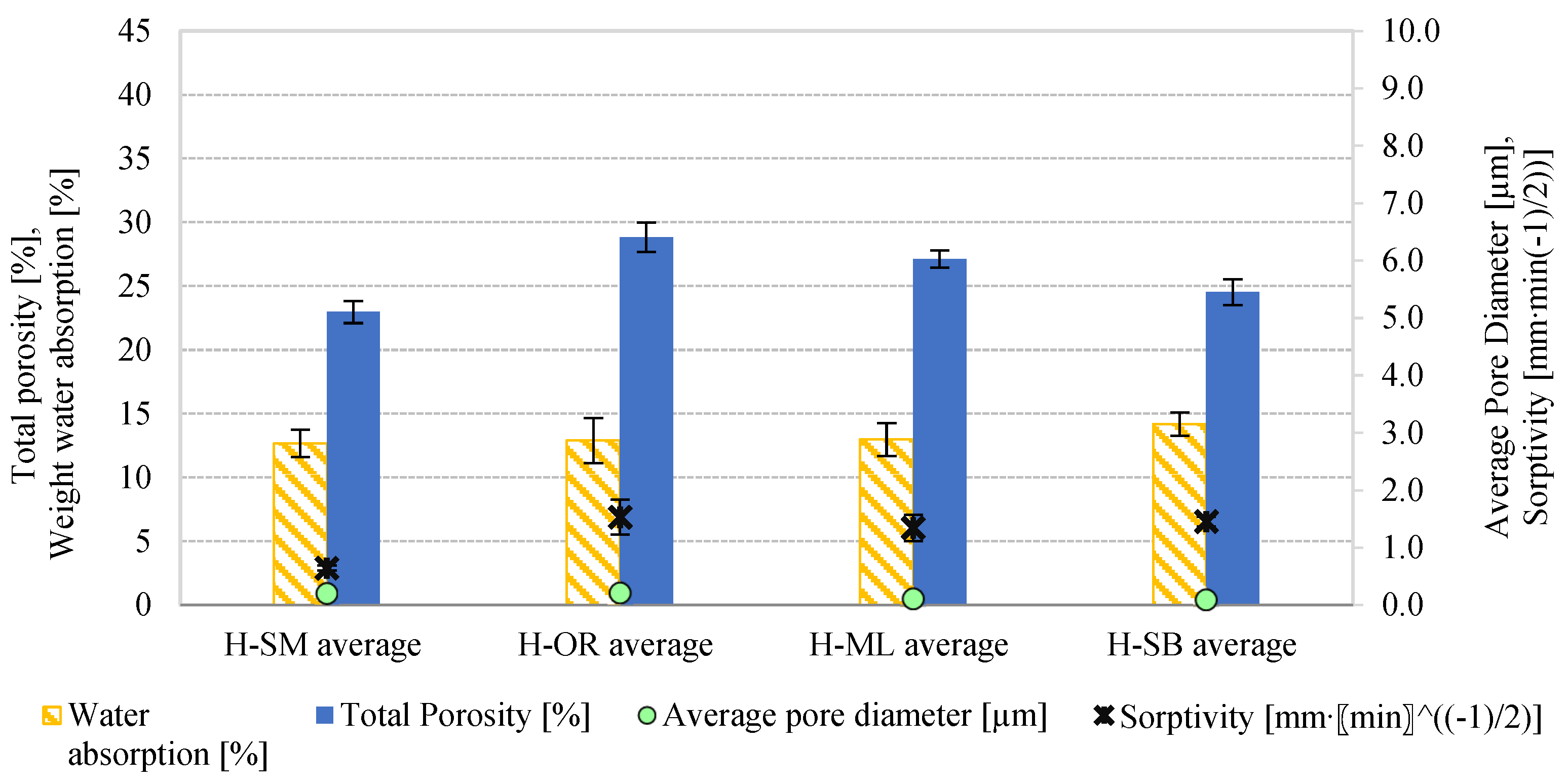

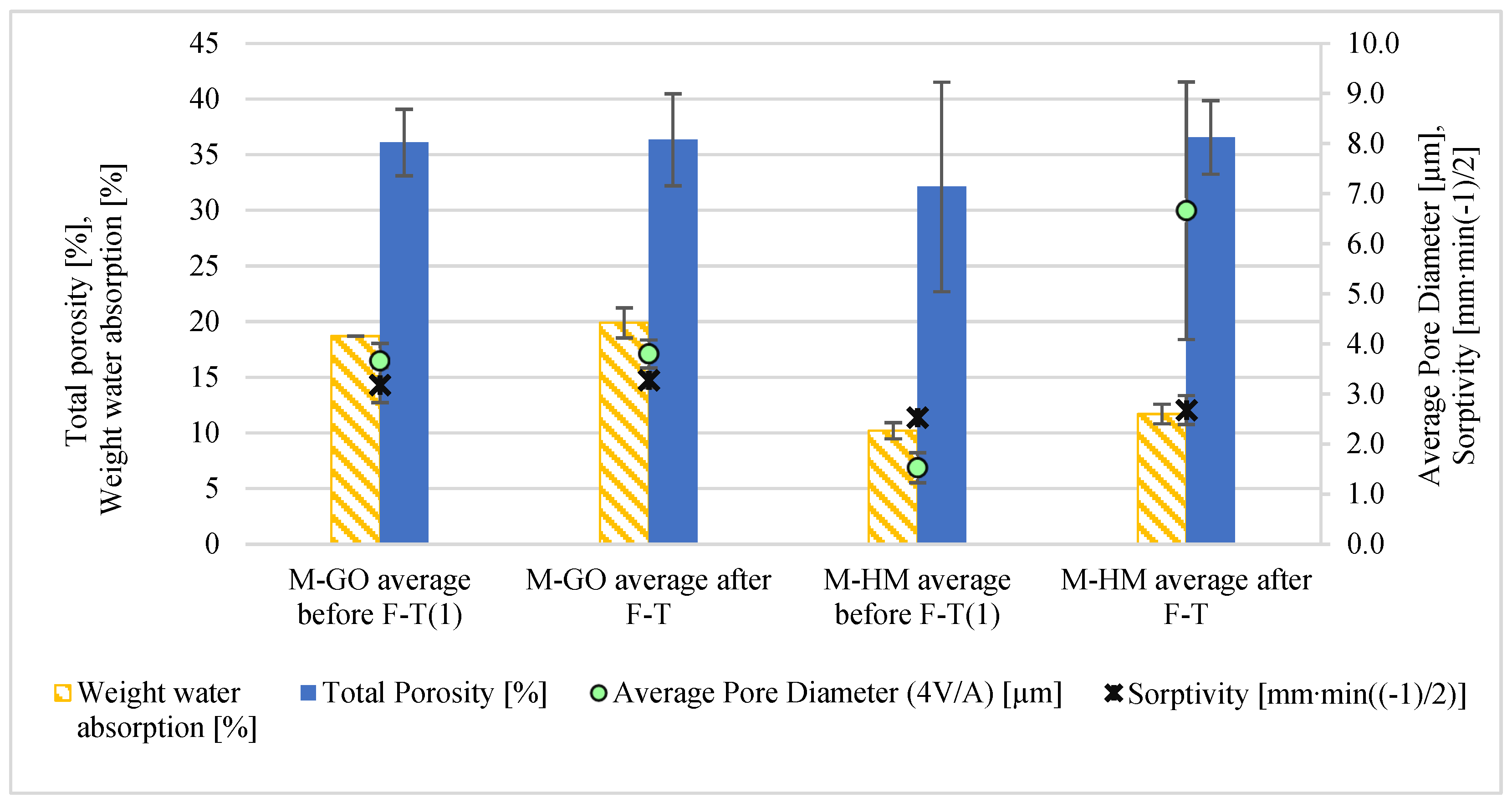

3.4. Hygric Properties Characterization

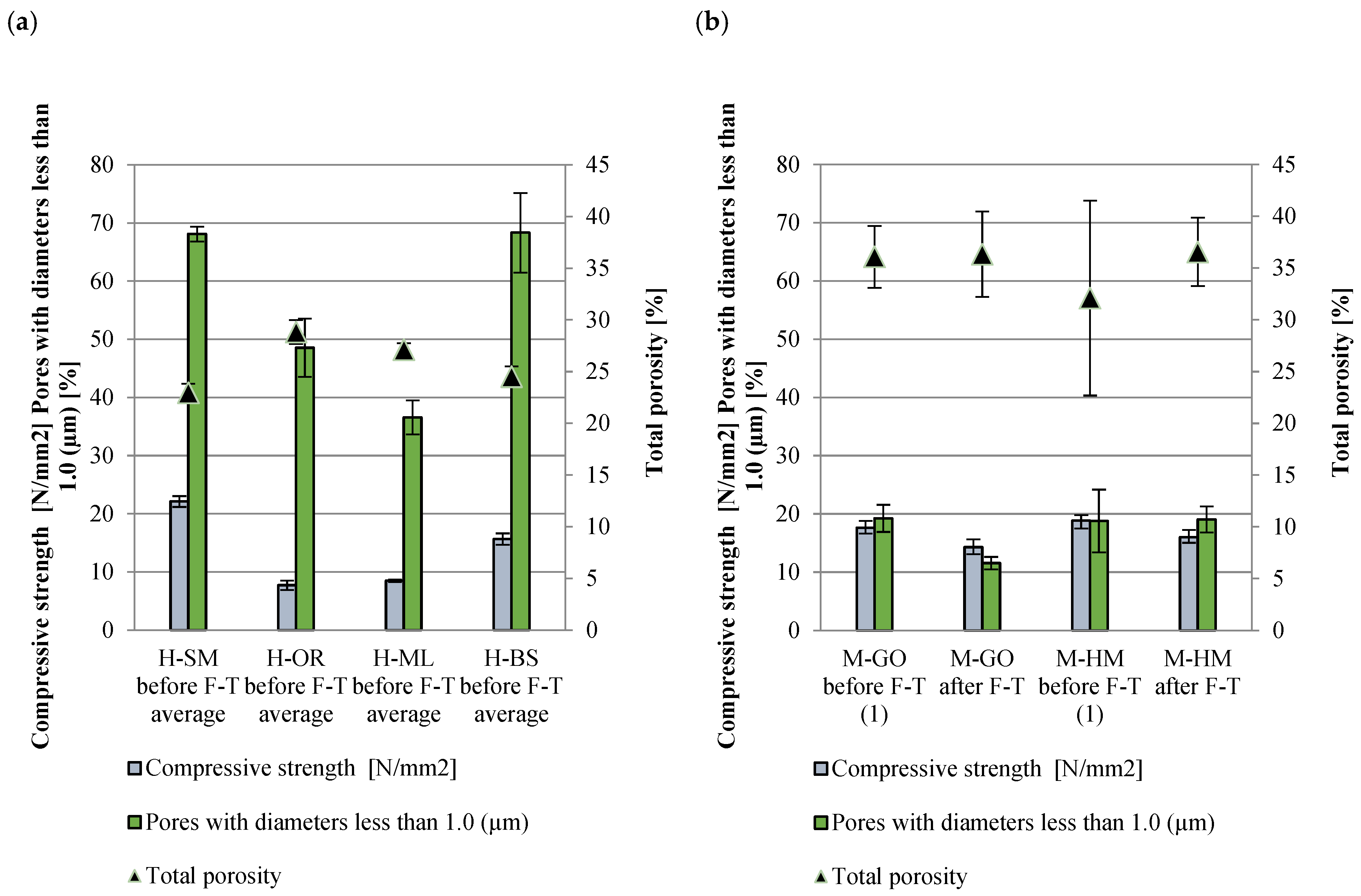

3.5. Compressive Strength Tests

3.6. Assessment of Frost Resistance

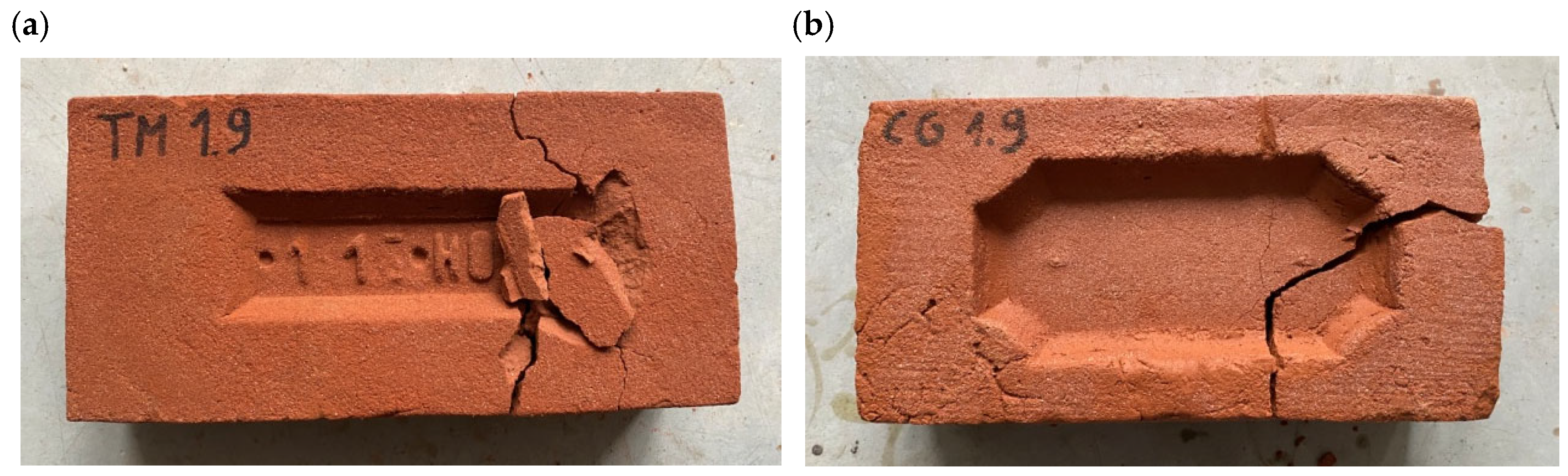

4. Conclusions

- A

- Freeze–thaw cycles led to a statistically significant reduction in compressive strength in both modern brick types (M-GO and M-HM), confirming their vulnerability to frost-induced mechanical degradation.

- B

- The pore size range of 10.0–3.0 µm was identified as particularly sensitive to freeze–thaw damage, indicating its relevance as a key durability indicator for ceramic building materials exposed to cyclic thermal stress. This range exhibited consistent changes across tested bricks, supported by statistical significance (p < 0.01).

- C

- Despite systematic comparative analysis, no consistent relationship was found between the physical, hygric, and mechanical parameters of historical and modern bricks. This highlights the high heterogeneity of historical ceramic materials and underscores the limitations of direct substitution with contemporary analogues.

- D

- The results provide new experimental data on pore structure and the moisture-related behavior of heritage bricks, which may serve as input parameters for numerical modeling of hygrothermal performance in historic masonry structures.

- E

- Future studies should incorporate a broader sample pool and apply advanced material characterization methods, such as SEM and micro-CT, to better understand complex degradation mechanisms—particularly those beyond freeze–thaw action, including salt crystallization, chemical weathering, and biological colonization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Płuska, I. 800 years of brickmaking in Poland—Historic development in its technological and aesthetic aspects. Conserv. News 2009, 26, 26–54. [Google Scholar]

- Benavente, D.; Linares-Fernández, L.; Cultrone, G.; Sebastián, E. Influence of microstructure on the resistance to salt crystallisation damage in brick. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2006, 39, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultrone, G.; Sebastián, E.; Elert, K.; de la Torre, M.J.; Cazalla, O.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C. Influence of mineralogy and firing temperature on the porosity of bricks. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2004, 24, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, M.P.; Messiga, B.; Duminuco, P. An approach to the dynamics of clay firing. Appl. Clay Sci. 1999, 15, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavía, S. The determination of brick provenance and technology using analytical techniques from the physical sciences. Archaeometry 2006, 48, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultrone, G.; Sidraba, I.; Sebastián, E. Mineralogical and physical characterization of the bricks used in the construction of the ‘Triangul Bastion’, Riga (Latvia). Appl. Clay Sci. 2005, 28, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero, M.I.; Dondi, M.; Fabbri, B.; Raimondo, M. The influence of shaping and firing technology on ceramic properties of calcareous and non-calcareous illitic-chloritic clays. Appl. Clay Sci. 2002, 20, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Arce, P.; Garcia-Guinea, J. Weathering traces in ancient bricks from historic buildings. Build. Environ. 2005, 40, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omari, A.; Brunetaud, X.; Beck, K.; Al-Mukhtar, M. Climatic conditions and limestone decay in Al-Namrud monuments, Iraq: Review and discussion. In Proceedings of the 2012 First National Conference for Engineering Sciences (FNCES 2012), Baghdad, Iraq, 7–8 November 2012; pp. 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponziani, D.; Ferrero, E.; Appolonia, L.; Migliorini, S. Effects of temperature and humidity excursions and wind exposure on the arch of Augustus in Aosta. J. Cult. Herit. 2012, 13, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiassi, P.B.; Lourenço, B. Long-Term Performance and Durability of Masonry Structures: Degradation Mechanisms, Health Monitoring and Service Life Design; Woodhead: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Giaccone, D.; Santamaria, U.; Corradi, M. An experimental study on the effect of water on historic brickwork masonry. Heritage 2020, 3, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koronthalyova, O. Moisture storage capacity and microstructure of ceramic brick and autoclaved aerated concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, C.J.W.P.; Gunneweg, J.T.M. The influence of materials characteristics and workmanship on rain penetration in historic fired clay brick masonry. Heron 2010, 55, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Stępień, P.; Spychał, E.; Skowera, K. A Comparative Study on Hygric Properties and Compressive Strength of Ceramic Bricks. Materials 2022, 15, 7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Midany, A.A.; Mahmoud, H.M. Mineralogical, physical and chemical characteristics of historic brick-made structures. Mineral. Petrol. 2015, 109, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.Y.; Chau, C.K. New Life of the Building Materials-Recycle, Reuse and Recovery. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 2884–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. Ineducable us: The applications and contexts of microscopy used for the characterisation of historic building materials. RILEM Tech. Lett. 2017, 2, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elert, K.; Cultrone, G.; Navarro, C.R.; Pardo, E.S. Durability of bricks used in the conservation of historic buildings-Influence of composition and microstructure. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.; Lourenco, F.M.; Castro, P.B. Ancient Clay Bricks: Manufacture and Properties Material, Technologies and Practise in Historic Heritage Structure, in Dordrecht; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysek, M.; Witkowski, P. A Comparative Study on the Compressive Strengthof Bricks from Different Historical Periods. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2016, 10, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumeziane, Y.A.; Pierre, A.; El Mankibi, F.; Lepiller, V.; Gasnier, M.; Désévaux, P. Hygrothermal properties of an early 20th century clay brick from eastern France: Experimental characterization and numerical modelling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrak, K.; Kubiś, M.; Cieślikiewicz, Ł.; Furmański, P.; Seredyński, M.; Wasik, M.; Wiśniewski, T.; Łapka, P. Measurement of Thermal, Hygric and Physical Properties of Bricks and Mortar Common for the Polish Market. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 660, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roles, S.; Carmeliet, J.; Plagge, R.; Roles, S.; Carmeliet, J.; Hens, H.; Adan, O.; Brocken, H.; Cerny, R.; Pavlik, Z.; et al. Interlaboratory Comparison of Hygric Properties of Porous Building Materials. J. Build. Phys. 2004, 27, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oti, J.E.; Kinuthia, J.M.; Bai, J. Freeze–thaw of stabilised clay brick. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.—Waste Resour. Manag. 2010, 163, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryszewska, T.; Kańka, S. Forms of damage of bricks subjected to cyclic freezing and thawing in actual conditions. Materials 2019, 12, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaberi, M.E.Z.; Gheni, A.; Myers, J.J. Ability to Resist Different Weathering Actions of Eco-Friendly Wood Fiber Masonry Blocks. In Proceedings of the 16th International Brick and Block Masonry Conference, Padova, Italy, 26–30 June 2016; pp. 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mallidi, S.R. Application of mercury intrusion porosimetry on clay bricks to assess freeze-thaw durability-a bibliography with abstracts. Constr. Build. Mater. 1996, 10, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, M.R.P. Porosity and Frost Resistance of Clay Bricks. In Brick and Block Masonry (8 th IBMAC) London; Elsevier Applied Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Raimondo, M.; Dondi, M.; Gardini, D.; Guarini, G.; Mazzanti, F. Predicting the initial rate of water absorption in clay bricks, Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 2623–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummerson, W.D.H.R.J.; Hall, C. Water movement in porous building materials—II. Hydraulic suction and sorptivity of brick and other masonry materials. Build. Environ. 1980, 15, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.A.; Hoff, W.D.; Hall, C. Water movement in porous building materials-XIV Absorption into a two-layer composite (SA < SB). Build. Environ. 1995, 30, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Arce, P.; Garcia-Guinea, J.; Gracia, M.; Mercedes; Obis, J. Bricks in historical buildings of Toledo City: Characterization and restoration. Mater. Charact. 2003, 50, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, K.B.; Vasudevan, V.; Ramamurthy, K. Water permeability assessment of alternative masonry systems. Build. Environ. 2003, 38, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, M.M.R.; El-Dieb, A.S.; Shrive, N.G. Sorptivity: A reliable measurement for surface absorption of masonry brick units. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2001, 34, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Janssen, H. Hygric properties of porous building materials (III): Impact factors and data processing methods of the capillary absorption test. Build. Environ. 2018, 134, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, L. Novel method of pore space interpretation based on joint Mercury Intrusion Porosimetr. Nafta-Gaz 2020, 5, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anovitz, L.M.; Cole, D.R. Characterization and analysis of porosity and pore structures. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2015, 80, 61–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.H.M.; Shariff, K.A.; Wahjuningrum, D.A.; Bakar, M.H.A.; Mohamad, H. A comprehensive review of the effects of porosity and macro- and micropore formations in porous β-TCP scaffolds on cell responses. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 59, 865–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilán, A.B.R.; Esteban, M.A.R.; Iglesias, M.N.A.; Perez, M.P.S.; Olea, M.S.C.; Valdizán, J.C. Experimental Study of the Mechanical Behaviour of Bricks from 19th and 20th Century Buildings in the Province of Zamora (Spain). Infrastructures 2018, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borusiewicz, W. Konserwacja Zabytków Budownictwa Murowanego; Wydawnictwo Arkady: Warsaw, Poland, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Misiewicz, J.; Wójcik, R.; Tunkiewicz, M.; Sikora, P. Medieval and Restoration Bricks: Water Transport (Hygric) and Microstructural Properties—A Compatibility Study. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunkiewicz, M.; Misiewicz, J.; Sikora, P.; Chung, S.Y. Hygric properties of machine-made, historic clay bricks from north-eastern poland (Former east prussia): Characterization and specification for replacement materials. Materials 2021, 14, 6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 772-21:2011; Methods of Test for Masonry Units—Part 21: Determination of Water Absorption of Clay and Calcium Silicate Masonry Units by Cold Water Absorption. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2011.

- Wójcik, R.; Tunkiewicz, M. Pory butelkowe—Charakterystyka, sposoby wyznaczania na przykładzie zaprawy cementowo-wapiennej. Mater. Bud. 2017, 10, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 15901-1:2016; Evaluation of Pore Size Distribution and Porosity of Solid Materials by Mercury Porosimetry and Gas Adsorption Part 1: Mercury Porosimetry. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Operator Manual for Autopore IV. Available online: https://www.micromeritics.com/Repository/Files/AutoPore_IV_9500_Operator_Manual_Rev_-_Mar_2018.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Künzel, H.M.; Kiessl, K. Calculation of heat and moisture transfer in exposed building components. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1996, 40, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 772-1+A1:2015-10; Methods of Test for Masonry Units—Part 1: Determination of Compressive Strength. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2015.

- PN-B-12012:2022-07; Test Methods for Ceramic Construction Products—Determination of Resistance to Freezing-Defrosting by Whole Product Testing Method. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2022.

- PN-EN 771-1+A1:2015; Specification for Masonry Units—Part 1: Clay Masonry Units. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2015.

- Walter, A.; Gallipoli, D. Effect of freezing-thawing cycles on the physical and mechanical properties of fired and unfired earth bricks. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deprez, M.; De Kock, T.; De Schutter, G.; Cnudde, V. A review on freeze-thaw action and weathering of rocks. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 203, 103143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šveda, M.; Sokolář, R. The Effect of Firing Temperature on the Irreversible Expansion, Water Absorption and Pore Structure of a Brick Body During Freeze-Thaw Cycles. Mater. Sci. 2013, 19, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Durgesh, C.R. Bricks and mortars in Lucknow monuments of c. 17–18 century. Curr. Sci. 2013, 104, 238–244. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Mishra, A. Geochemical characterization of bricks used in historical monuments of 14–18th century CE of Haryana region of the Indian subcontinent: Reference to raw materials and production technique. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranto, M.; Barba, L.; Blancas, J.; Bloise, A.; Cappa, M.; Chiaravalloti, F.; Crisci, G.M.; Cura, M.; De Angelis, D.; De Luca, R.; et al. The bricks of Hagia Sophia (Istanbul, Turkey): A new hypothesis to explain their compositional difference. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 38, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podoba, R.; Kaljuvee, T.; Štubňa, I.; Podobník, Ľ. Research on historical bricks from a Baroque Church. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2014, 118, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sharma, S. Thermal and spectroscopic characterization of archeological pottery from Ambari, Assam. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2016, 5, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paama, L.; Pitkãnen, I.; Perämäki, P. Analysis of archaeological samples and local clays using ICP-AES, TG-DTG and FTIR techniques. Talanta 2000, 51, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiano, P.; Ioppolo, S.; De Stefano, C.; Pettignano, A.; Sergi, S.; Piraino, P. Study and characterization of the ancient bricks of monastery of ‘San Filippo di Fragalà’ in Frazzanò (Sicily). Anal. Chim. Acta 2004, 519, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubna, I.; Podoba, R.; Bacík, P.; Podobník, Ľ. Romanesque and Gothic bricks from church in Pác—Estimation of the firing temperature. Építöanyag 2013, 65, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesołowska, M.; Kaczmarek, A. Dependence of Capillary Properties of Contemporary Clinker Bricks on Their Microstructure. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 022045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, P. Determinación de las características mecánicas de los muros de fábrica de ladrillo en la arquitectura doméstica sevillana de los siglos XVIII Y XIX. Inf. Construcción 2009, 61, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Matysek, P.; Stryszewska, T.; Kańka, S.; Witkowski, M. The influence of water saturation on mechanical properties of ceramic bricks—Tests on 19th- century and contemporary bricks. Mater. Construcción 2016, 66, e095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidou, M.; Papayianni, I.; Pachta, V. Analysis and characterization of Roman and Byzantine fired bricks from Greece. Mater. Struct. 2015, 48, 2251–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netinger-Grubeša, I.; Benšic, M.; Vračevic, M. New methods for assessing brick resistance to freeze-thaw cycles. Mater. Constr. 2021, 71, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Cui, Y.J.; Dupla, J.C.; Canou, J. Soil-water retention behaviour of fine/coarse soil mixture with varying coarse grain contents and fine soil dry densities. Can. Geotech. J. 2022, 59, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gu, Z.; Guo, P.; Zhao, W. Comparative Laboratory Wettability Study of Sandstone, Tuff, and Shale Using 12-MHz NMR T1-T2 Fluid Typing: Insight of Shale. SPE J. 2024, 29, 4781–4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Dimensions | Color-Code | Color Name | Color | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L [mm] | W [mm] | H [mm] | ||||

| H-SM | 308.0 | 145.0 | 65.0 | 7.5YR 3/8 | Dark strong reddish brown |  |

| H-OR | 300.5 | 146.5 | 74.5 | 7.5YR 5/6 | Reddish brown |  |

| H-ML | 308.0 | 155.0 | 77.5 | 5YR 4/6 | Moderate to strong reddish brown |  |

| H-SB | 295.5 | 135.0 | 68.0 | 5YR 5/6 | Reddish brown |  |

| M-GO | 280.0 | 140.0 | 85.0 | 7.5YR 4/8 | Strong reddish brown |  |

| M-HM | 250.0 | 120.0 | 65.0 | 7.5YR 4/6 | Moderate reddish brown |  |

| Samples | Bulk Density Before F–T Cycles [kg/m3] | Bulk Density After F–T Cycles [kg/m3] | Water Absorption Before F–T Cycles [% m/m] | Water Absorption After F–T Cycles [% m/m] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-SM | 1900.7 ± 21.64 | 1829.0 ± 4.77 | 12.7 ± 1.07 | - |

| H-OR | 1800.5 ± 52.22 | 1717.7 ± 50.73 | 12.9 ± 1.76 | - |

| H-ML | 1845.4 ± 1.86 | 1818.8 ± 27.00 | 13.0 ± 1.29 | - |

| H-SB | 1860.80 ± 27.37 | 1685.1 ± 130.85 | 14.2 ± 0.90 | - |

| M-GO | 1521.0 ± 2.38 (1) | 1664.9 ± 2.24 | 18.7 ± 0.12 (1) | 19.9 ± 1.35 |

| M-HM | 1518.0 ± 2.26 (1) | 1564.0 ± 2.47 | 10.2 ± 0.72 (1) | 11.7 ± 0.88 |

| Brick Type | % SiO2 | %Fe2O3 | %K2O | % CaO | % TiO2 | %ZrO2 | MnO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-SM | 53.76 | 29.79 | 7.27 | 6.25 | 2.09 | 0.36 | 0.30 |

| H-OR | 55.89 | 30.92 | 7.11 | 2.74 | 2.24 | 0.41 | 0.25 |

| H-ML | 60.62 | 24.04 | 8.33 | 3.77 | 2.24 | 0.37 | 0.25 |

| H-SB | 53.36 | 25.98 | 6.89 | 10.42 | 2.37 | 0.39 | 0.30 |

| M-GO | 68.83 | 11.46 | 3.61 | 11.53 | 2.16 | 0.53 | 0.24 |

| M-HM | 65.25 | 13.09 | 4.87 | 13.02 | 2.19 | 0.95 | 0.27 |

| Brick Type | Quartz (w/w%) | Hematite (w/w%) | Illite (w/w%) | Albite (w/w%) | Geotite (w/w%) | Calcite (w/w%) | Amorphous (w/w%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-SM | 44.78 | 4.11 | - | 10.04 | 15.52 | - | 28.10 |

| H-OR | 48.49 | 11.54 | - | 21.00 | - | - | 18.95 |

| H-ML | 44.80 | 3.85 | 17.59 | 11.71 | 1.88 | - | 20.15 |

| H-SB | 42.23 | - | 11.45 | 14.2 | - | 7.65 | 25.73 |

| M-GO | 60.35 | 4.35 | - | 17.10 | 2.95 | - | 15.25 |

| M-HM | 59.15 | 4.75 | - | 16.85 | 2.90 | - | 16.31 |

| Brick Type | Total Porosity [%] | Total Pore Area [m2/g] | Average Pore Diameter (4V/A) [µm] | t (Paired) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-SM before F–T | 22.97 ± 0.87 | 2.41 ± 0.11 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | −12.254 | 0.007 |

| H-SM after F–T | 28.69 ± 1.13 | 1.12 ± 0.17 | 0.57 ± 0.06 | - | - |

| H-OR before F–T | 28.83 ± 1.16 | 3.05 ± 0.29 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | −0.802 | 0.507 |

| H-OR after F–T | 30.43 ± 3.59 | 1.63 ± 0.70 | 0.47 ± 0.14 | - | - |

| H-ML before F–T | 27.13 ± 0.62 | 5.21 ± 0.52 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | −1.713 | 0.229 |

| H-ML after F–T | 29,70 ± 2.03 | 4.81 ± 0.20 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | - | - |

| H-SB before F–T | 24.52 ± 1.00 | 6.70 ± 0.43 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | −0.896 | 0.465 |

| H-SB after F–T | 25.53 ± 0.98 | 5.92 ± 0.42 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | - | - |

| Brick Type | Total Porosity [%] | Total Pore Area [m2/g] | Average Pore Diameter (4V/A) [µm] | t (Paired) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-GO before F–T | 36.09 ± 2.99 (1) | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 3.66 ± 0.35 | −0.707 | 0.95 |

| M-GO after F–T | 36.34 ± 4.13 | 0.43 ± 0.06 | 3.80 ± 0.28 | - | - |

| M-HM before F–T | 32.11 ± 9.42 (1) | 0.55 ± 0.14 | 1.53 ± 0.30 | −0.07 | 0.553 |

| M-HM after F–T | 36.56 ± 3.30 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 6.66 ± 2.57 | - | - |

| Brick Type | Sorptivity | Capillary Absorption Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| H-SM | 0.647 ± 0.043 | 0.083 |

| H-OR | 1.532 ± 0.303 | 0.197 |

| H-ML | 1.347 ± 0.230 | 0.174 |

| H-SB | 1.458 ± 0.084 | 0.188 |

| M-GO before F–T | 3.1807 ± 0.351 (1) | 0.410 |

| M-HM before F–T | 2.5354 ± 0.146 (1) | 0.327 |

| M-GO after F–T | 3.276 ± 0.121 | 0.422 |

| M-HM after F–T | 2.688 ± 0.289 | 0.346 |

| Brick Type | Compressive Strength [N/mm2] |

|---|---|

| H-SM | 22.11 ± 0.94 |

| H-OR | 7.72 ± 0.82 |

| H-ML | 8.49 ± 0.24 |

| H-BS | 15.66 ± 0.98 |

| M-GO before F–T (1) | 17.61 ± 1.18 |

| M-GO after F–T | 14.27 ± 1.35 |

| M-HM before F–T (1) | 18.85 ± 0.94 |

| M-HM after F–T | 15.99 ± 1.25 |

| Brick Type/Property | Gothic Style Brick (M-GO) | Handmade Building Brick (M-HM) |

|---|---|---|

| Compressive strength before exposure to freeze/thaw cycles (N/mm2) | 17.61 ± 2.36 (1) | 18.85 ± 1.88 (1) |

| Compressive strength after exposure to freeze/thaw cycles (N/mm2) | 14.27 ± 1.39 | 15.39 ± 1.06 |

| Ratio of compressive strength after and before exposure to freeze/thaw cycles | 0.81 | 0.82 |

| t (paired)/p-value | 4.38/0.048 | 10.74/0.009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Misiewicz, J.; Tunkiewicz, M.; Ballai, G.; Kukovecz, Á. Characterization of Bricks from Baroque Monuments in Northeastern Poland: A Comparative Study of Hygric Behavior and Microstructural Properties for Restoration Applications. Materials 2025, 18, 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18133023

Misiewicz J, Tunkiewicz M, Ballai G, Kukovecz Á. Characterization of Bricks from Baroque Monuments in Northeastern Poland: A Comparative Study of Hygric Behavior and Microstructural Properties for Restoration Applications. Materials. 2025; 18(13):3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18133023

Chicago/Turabian StyleMisiewicz, Joanna, Maria Tunkiewicz, Gergő Ballai, and Ákos Kukovecz. 2025. "Characterization of Bricks from Baroque Monuments in Northeastern Poland: A Comparative Study of Hygric Behavior and Microstructural Properties for Restoration Applications" Materials 18, no. 13: 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18133023

APA StyleMisiewicz, J., Tunkiewicz, M., Ballai, G., & Kukovecz, Á. (2025). Characterization of Bricks from Baroque Monuments in Northeastern Poland: A Comparative Study of Hygric Behavior and Microstructural Properties for Restoration Applications. Materials, 18(13), 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18133023