Clinician’s Guide to Material Selection for All-Ceramics in Modern Digital Dentistry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. An Updated Overview of Dental Ceramics

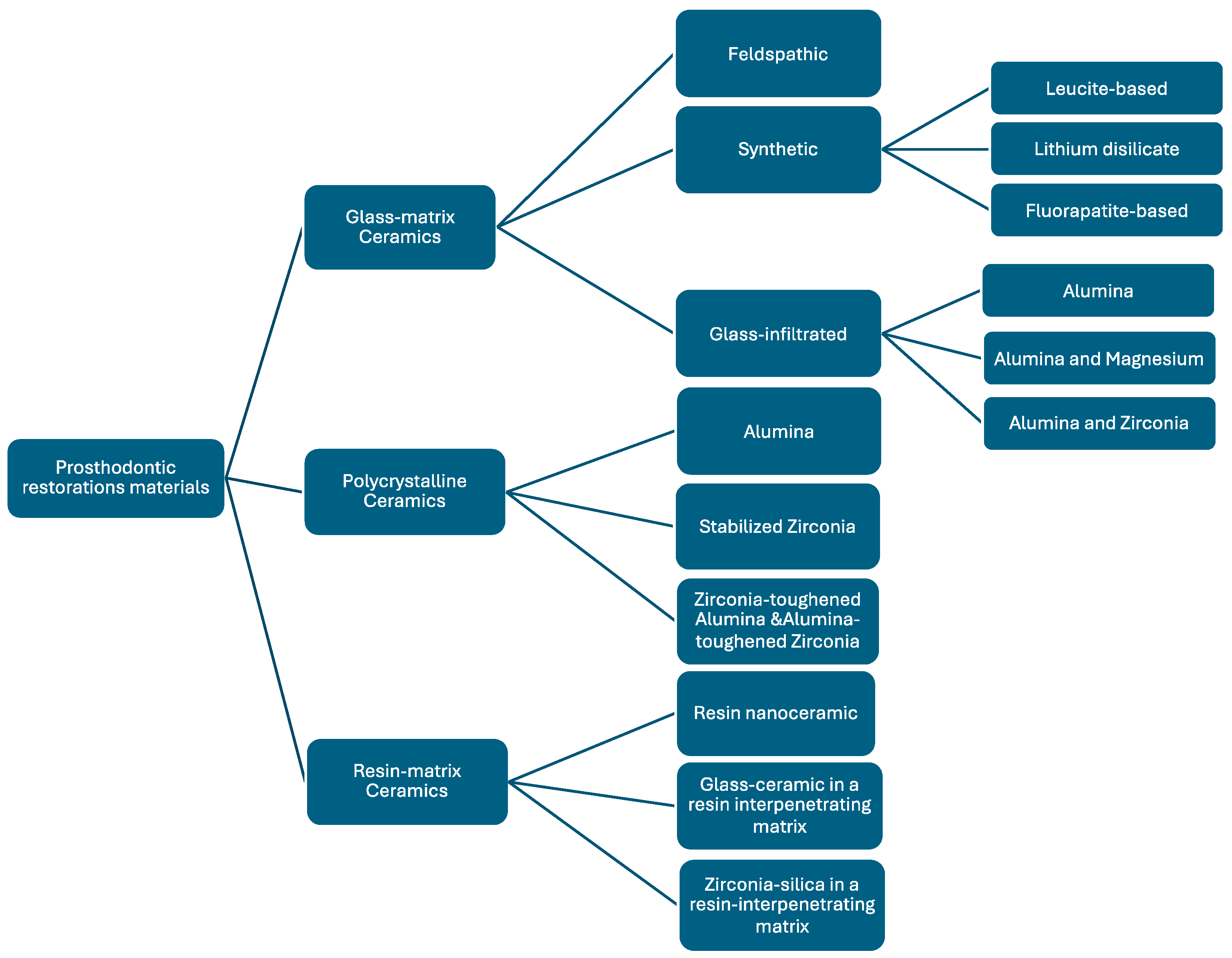

3.1. Classification of Dental Ceramics According to Material Composition

- 1.

- Glass matrix ceramics are a class of inorganic, non-metallic materials created through specifically crystallising glasses using a variety of processing methods [34]. These ceramics are divided into three subgroups: glass-infiltrated, synthetic, and feldspathic ceramics [35]. Their ability to replicate dental tissues and their biocompatibility and chemical endurance in the oral environment, along with their favourable mechanical qualities, make them popular for use in aesthetic restorations for anterior teeth [36].1.1. Felspathic ceramic (e.g., IPS Classic by Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein; Vitadur, Vita VMK 68, Vitablocs Mark II, and specific Vitablocs from VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany). These materials are still used as veneers on ceramic and metal alloy frames [37] and as an aesthetic material bonded to dental structures [6,23,38]. Dental ceramics are made of feldspar, quartz, and kaolin, with quartz [39] being the primary component for restoration translucency. Alumina is added to increase strength, while kaolin, a hydrated aluminium silicate, binds ceramic particles together [14]. VITABLOCS from VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany, a feldspar-based CAD/CAM ceramic, is widely used for its ability to replicate natural tooth colours. VITA has introduced new generations, such as TriLuxe (2003) and TriLuxe forte (2007), which have three and four layers with varying shade intensities, making them indicated for partial or full coverage crowns and veneers [40]. VITABLOCS RealLife (2010) VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany enhances the shade gradient with multichromatic feldspar ceramic. VITA Mark II, after hydrofluoric acid surface etching, exhibits micropores and channels with irregular ceramic particles, making it suitable for composite luting cement [41].1.2. Synthetic ceramics are popular due to their chemical stability, biocompatibility, translucency, and mechanical strength, making them ideal for non-retentive bonded restorations [36]. Examples include lithium disilicate, leucite-reinforced, fluorapatite-based ceramics, and zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate.

- Leucite-based ceramic (e.g., IPS Empress Esthetic, Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein; IPS Empress CAD Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein; OPC 3G Kerr Dental (Envista Corporation), Brea, CA, USA) made by processing two basic glasses has a 45% crystalline content of leucite and is fired at 1200 °C, pressed in moulds, and stabilised in cubic form. Its application is limited to veneers, onlays, inlays, and single crowns [42].

- Lithium disilicate ceramic and derivates (e.g., IPS e.max CAD, IPS e.max Press from Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein; Obsidian from Glidewell Laboratories, Newport Beach, CA, USA; VITA Suprinity from VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany; Celtra Duo, Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC, USA). The IPS Empress 2 from Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein, introduced in 1998, is a ceramic material derived from the crystallisation of a SiO2-Li2O precursor glass into lithium disilicate and smaller amounts of lithium metasilicate [42]. These crystals make up about 70% of the glass ceramic volume, with a thickly interlocked microstructure contributing to its strength. These materials show improved mechanical characteristics that make them suitable for use in crowns in the anterior and posterior area, inlays, onlays, monolithic infrastructures, and anterior three-unit restorations. Its layered crystals and interlocked microstructure contribute to its strength [43].

- Fluorapatite-based ceramic (e.g., IPS e.max Ceram, ZirPress, Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein) as a glass ceramic material with fluorapatite crystals for highly aesthetic qualities is suitable for veneers and glazing lithium disilicate frameworks [37].

- Zirconia-reinforced lithium disilicate (e.g., Celtra Duo, Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC, USA; Vita Suprinity, VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany). Adding up to 10% zirconium oxide to precursor glass has been used since 2013 to reinforce synthetic glass ceramics. These blocks are either partly crystallised, which need further heat treatment, or totally crystallised [44]. These materials exhibit superior aesthetic properties, translucency, opalescence, and fluorescence, making their indications [14] comparable to those of lithium disilicate glass ceramics due to their similarity.1.3. Glass-infiltrated ceramic (e.g., In-Ceram Alumina, VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany); alumina and magnesium (e.g., In-Ceram Spinell, VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany); alumina and zirconia (e.g., In-Ceram Zirconia, VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany). These dental ceramics are ceramic glass composites with two interpenetrating phases, with aesthetic and strength properties determined by porous core chemical composition [6]. The opaque aspect requires the application of a porcelain veneer to enhance aesthetics. The use of this class of materials decreases as zirconia and lithium disilicate have become more common, particularly for CAD/CAM manufacturing [14].

- 2.

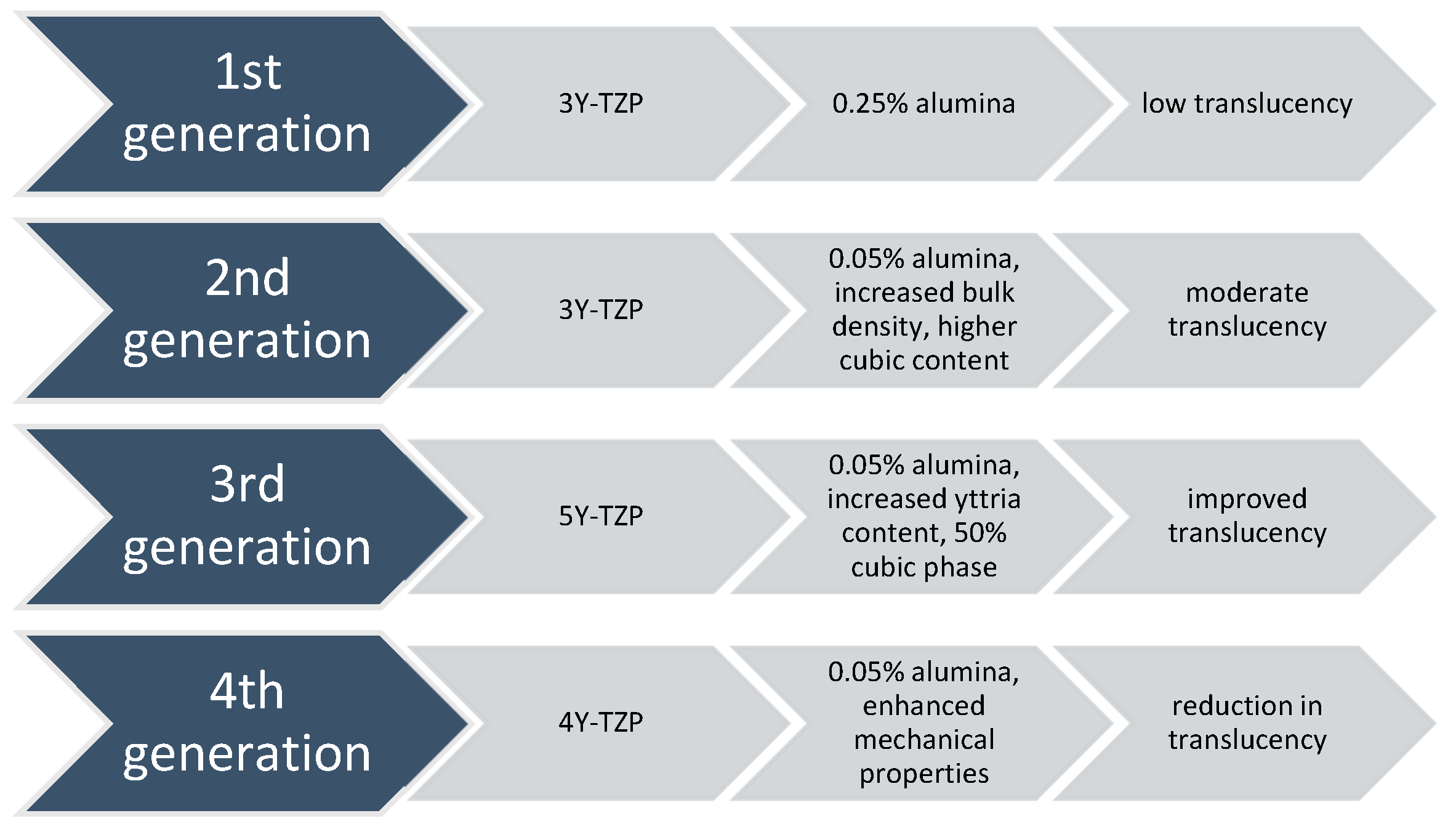

- Polycrystalline ceramics are restorative materials with a microstructure consisting of tightly packed crystalline grains, providing superior mechanical properties like increased strength and fracture toughness. The absence of a glassy phase results in distinct poor translucency and aesthetic qualities [45]. Researchers are exploring modifications to enhance properties, balancing strength with aesthetics for optimal clinical performance.2.1. Alumina (e.g., Procera AllCeram and Nobel Biocare, Göteborg, Sweden; In-Ceram AL, VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany). Al2O3, the material’s primary component, has a 99.5% purity level. It was first introduced as the primary component for CAD/CAM manufacturing by Nobel Biocare, Göteborg, Sweden in the middle of the 1990s. Although it is a highly strong and resistant material, its high elastic modulus has made it more susceptible to fractures among all dental ceramics. This vulnerability to core fracture and the development of materials with improved mechanical properties—such as stabilised zirconia’s transformation toughening properties—have led to a decrease in the use of alumina [22,33,46].2.2. Stabilised zirconia (e.g., NobelProcera Zirconia, Nobel Biocare, Göteborg, Sweden; Lava/Lava Plus, 3M ESPE, (3M Oral Care), St. Paul, MN, USA; In-Ceram YZ, VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany; Zirkon, DCS Dental AG, Buchs, Switzerland; Katana Zirconia ML, Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc., Tokyo, Japan; Cercon ht, Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC, USA; Prettau Zirconia, Zirkonzahn GmbH, Gais, Italy; IPS e.max ZirCAD, Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein; Zenostar, Wieland Dental (Ivoclar Vivadent AG after acquisition), Pforzheim, Germany). Zirconia (ZrO2) is a common material for dental restorations because of its excellent mechanical and aesthetic qualities, particularly transformation toughening. Modern chairside milling and rapid-sintering technologies have contributed to the efficiency of the manufacturing process [47]. However, zirconia’s opaque white colour can make it look less desired, so it is often veneered with porcelain to improve aesthetics [48]. Zirconia is a crystalline substance including three main phases: monoclinic, tetragonal, and cubic [49,50]. As it cools, it undergoes a transformation from cubic to monoclinic, leading to a 5% volumetric expansion [51]. This can cause fractures and make it brittle, making it unsuitable for biomedical, structural, or functional applications. Metal oxides like yttrium oxide stabilise the tetragonal phase, with Y2O3 being the most commonly used. Transformation toughening enhances the material’s physical properties, providing high flexural strength and fracture toughness [52]. However, it still has drawbacks like translucency level, radiopacity, and limited light transmission [53]. 3Y-TZP, a traditional zirconia dental material with 0.25–0.5 wt.% alumina, has been used for over 25 years due to its high mechanical properties and biocompatibility, making it suitable for core materials and multi-unit restorations [54]. Nevertheless, its high opacity limits its aesthetic considerations. In 2013, improved versions were introduced by reducing alumina content [47] and enhancing translucency through high-temperature sintering. The development of highly translucent 3Y-TZP with less than 0.05% alumina and the introduction of 5Y-PSZ, which contains 5 mol% yttria and approximately 50% cubic phase [55], further improved translucency, allowing for monolithic zirconia restorations in anterior teeth [50]. Nonetheless, increasing the cubic phase content can negatively impact mechanical properties like flexural strength and fracture toughness. Efforts to optimise material properties for monolithic zirconia restorations led to the introduction of 4Y-PSZ in 2017, which has a reduced yttria content (4 mol%) compared to 5Y-PSZ, resulting in improved mechanical properties but compromised optical characteristics. 4Y-PSZ is suitable for both anterior and posterior crowns and short-span fixed partial dentures [55], while 5Y-PSZ is mainly for anterior crowns [56]. Higher yttria content enhances optical properties but reduces mechanical strength [57]. Among yttria-stabilised zirconia, 3Y-TZP has the highest mechanical strength but is opaque, limiting its use to non-aesthetic areas. 5Y-PSZ offers better aesthetic outcomes but lower strength, making 4Y-PSZ a balanced option. Increasing the cubic phase in zirconia improves translucency but decreases strength (Figure 2) [58].Overall, while third-generation zirconia excels in optical properties, fourth-generation zirconia offers better restoration longevity [59]. The introduction of polychromatic or colour-gradient blocks, which replicate natural tooth colour transitions, combines high strength and enhanced translucency, with high-strength zirconia in the dentin region and high translucency in the incisal or occlusal areas for improved aesthetics. Dental zirconia is now classified into three types: monochromatic zirconia ceramics with uniform composition, polychromatic multilayered zirconia ceramics, and polychromatic hybrid-structured multilayered zirconia ceramics [60].2.3. Zirconia-toughened alumina (ZTA) and alumina-toughened zirconia (ATZ) are composite materials where the ratio of zirconia and alumina can be adjusted during manufacturing to achieve specific properties. The quantity of zirconia or alumina in the composite may be adjusted and modified according to customer preferences or production techniques to improve resistance to low-temperature degradation [61]. Notably, the clinician should distinguish between ZTA, which has an alumina matrix with zirconia particles, and ATZ, which has a zirconia matrix with alumina particles, as this significantly influences the resulting material properties. In comparison to Y-TZP, these composite materials claim benefits such as resistance to low-temperature deterioration, superior strength and fracture toughness, and cyclic fatigue strength exceeding twice that of Y-TZP [62,63], while the actual performance is highly dependent on the precise composition and processing of the composite.

- 3.

- Resin matrix ceramics are hybrid materials composed of organic polymers and inorganic fillers, typically ground ceramics [64]. They have unique properties due to the interpenetrating nature of organic and inorganic elements. The inorganic component makes up over 60% of the weight, while the organic component consists of a polymer matrix [42]. In contrast to traditional ceramics, the aim of the development of these materials is to more closely replicate the dentin’s elastic modulus. At the same time, the goal was to produce a material that was easier to refine and mill than glass matrix ceramics, making composite resin easier to use for repair or modification [6]. According to Bajraktarova-Valjakova et al. [14], this class of ceramics includes two types of materials: dispersed-phase materials and polymer-infiltrated ceramics. Dispersed-phase materials, first introduced in conservative dentistry in the 2000s, are made from composite resins inserted in a plastic phase. Two composites, nanoceramic resins (NCR) and zirconia–silica, differ in the size of their ground ceramic particles. NCR has nanometric ceramic particles and micrometre-sized zirconia–silica components. Polymerisation is carried out at high temperatures [65]. NCR’s elastic properties make it convenient for intraoral milling and repair with less pulpal damage risk, emphasising clinical performance [66].3.1. Resin nanoceramic (e.g., Lava Ultimate, 3M ESPE (3M Oral Care), St. Paul, MN, USA) consisting of nanoscale ceramic particles dispersed within a resin matrix;3.2. Resin-infiltrated glass ceramic (e.g., Enamic, VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany) where a glass ceramic network is infiltrated with a polymer;3.3. Resin-infiltrated zirconia–silica nanoceramics (e.g., Paradigm MZ100 Blocks, 3M ESPE (3M Oral Care), St. Paul, MN, USA), which combine zirconia–silica nanoparticles within a resin matrix.

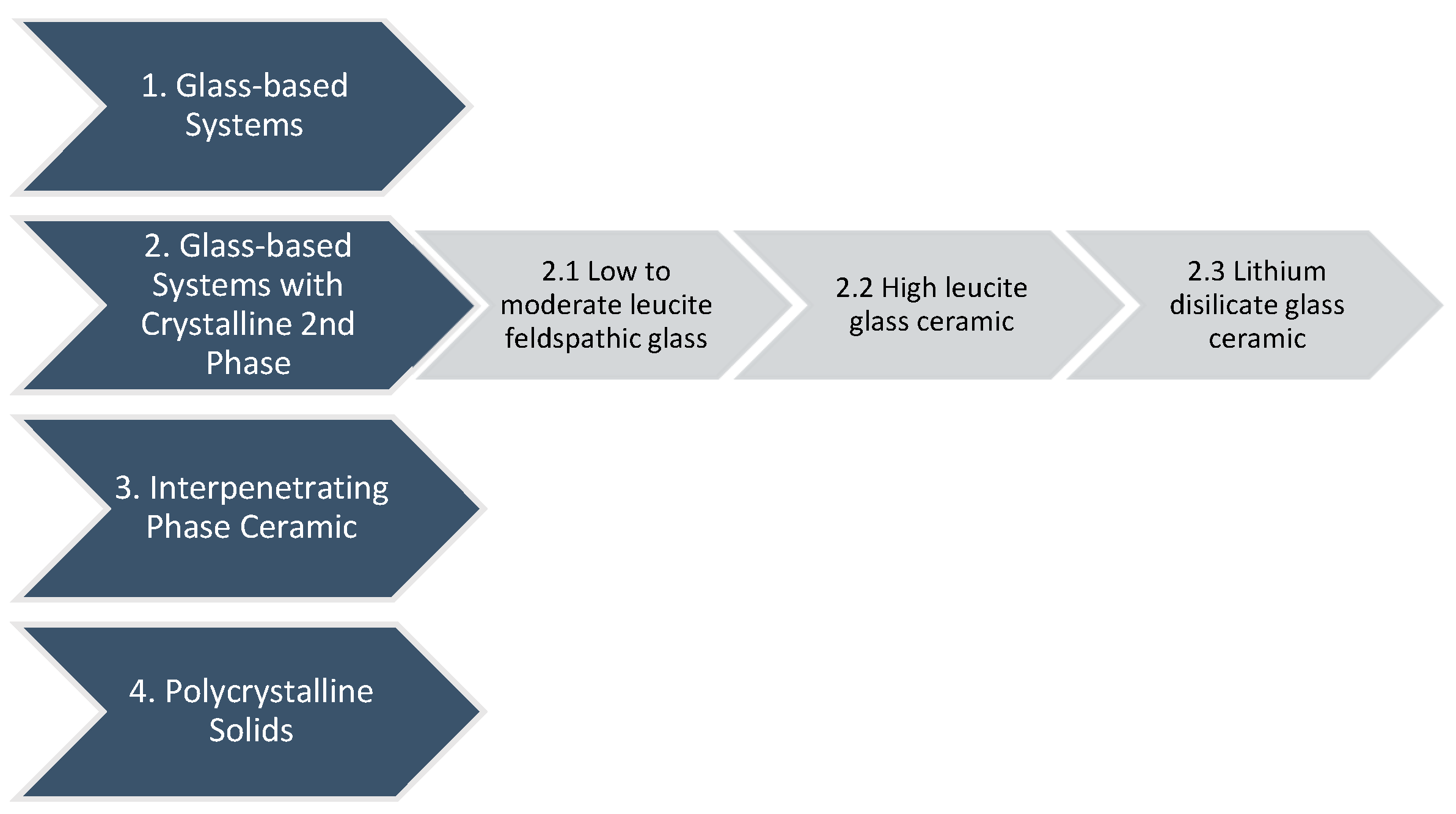

- First Category: Glass-based systems

- Second Category: Glass-based systems with a crystalline second phase, porcelain

- 2.1. Subcategory: Low to moderate leucite-containing feldspathic glass

- 2.2. Subcategory: High leucite-containing (approximately 50%) glass

- 2.3. Subcategory: Lithium disilicate glass ceramic

- Third Category: Interpenetrating phase ceramic

- Fourth Category: Polycrystalline solids

3.2. Manufactoring Techniques of Dental Ceramics

3.3. The Applicability and Clinical Considerations of Dental Ceramics

3.4. Properties of Ceramic Materials

4. Adhesive Materials in All-Ceramic Dentistry

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tennert, C.; Suárez Machado, L.; Jaeggi, T.; Meyer-Lueckel, H.; Wierichs, R.J. Posterior Ceramic Versus Metal Restorations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 1623–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.H.D.; Lima, E.; Miranda, R.B.P.; Favero, S.S.; Lohbauer, U.; Cesar, P.F. Dental Ceramics: A Review of New Materials and Processing Methods. Braz. Oral Res. 2017, 31, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulaiman, T.A. Materials in Digital Dentistry-A Review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2020, 32, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghodsi, S.; Arzani, S.; Shekarian, M.; Aghamohseni, M. Cement Selection Criteria for Full Coverage Restorations: A Comprehensive Review of Literature. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2021, 13, e1154–e1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.A.; Bergeron, C.; Diaz-Arnold, A. Cementing All-Ceramic Restorations: Recommendations for Success. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2011, 142, 20S–24S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracis, S.; Thompson, V.P.; Ferencz, J.L.; Silva, N.R.; Bonfante, E.A. A New Classification System for All-Ceramic and Ceramic-Like Restorative Materials. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2015, 28, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzic, C.; Pricop, M.O.; Jivanescu, A.; Ursoniu, S.; Negru, R.M.; Romînu, M. Assessment of Different Techniques for Adhesive Cementation of All-Ceramic Systems. Medicina 2022, 58, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zortuk, M.; Bolpaca, P.; Kilic, K.; Ozdemir, E.; Aguloglu, S. Effects of Finger Pressure Applied By Dentists during Cementation of All-Ceramic Crowns. Eur. J. Dent. 2010, 4, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraçoğlu, A.; Cura, C.; Cötert, H.S. Effect of Various Surface Treatment Methods on the Bond Strength of the Heat-Pressed Ceramic Samples. J. Oral Rehabil. 2004, 31, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersu, B.; Yuzugullu, B.; Ruya Yazici, A.; Canay, S. Surface Roughness and Bond Strengths of Glass-Infiltrated Alumina-Ceramics Prepared Using Various Surface Treatments. J. Dent. 2009, 37, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.B.; Quinn, G.D. Material Properties and Fractography of an Indirect Dental Resin Composite. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, P.J.; Alla, R.K.; Alluri, V.R.; Datla, S.R.; Konakanchi, A.; Konakanchi, A. Dental Ceramics: Part I—An Overview of Composition, Structure and Properties. Am. J. Mater. Eng. Technol. 2015, 3, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- al Edris, A.; al Jabr, A.; Cooley, R.L.; Barghi, N. SEM Evaluation of Etch Patterns by Three Etchants on Three Porcelains. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1990, 64, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajraktarova Valjakova, E.; Lj, G.; Korunoska Stevkovska, V.; Gigovski, N.; Kapusevska, B.; Mijoska, A.; Bajevska, J.; Bajraktarova Misevska, C.; Grozdanov, A. Dental Ceramic Materials, Part I: Technological Development of All-Ceramic Dental Materials. Maced. Stomatol. Rev. 2018, 41, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Perdigão, J.; Araujo, E.; Ramos, R.Q.; Gomes, G.; Pizzolotto, L. Adhesive Dentistry: Current Concepts and Clinical Considerations. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Hipólito, V.; Rodrigues, F.P.; Piveta, F.B.; Azevedo, L.d.C.; Bruschi Alonso, R.C.; Silikas, N.; Carvalho, R.M.; De Goes, M.F.; Perlatti D’Alpino, P.H. Effectiveness of Self-Adhesive Luting Cements in Bonding to Chlorhexidine-Treated Dentin. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmage, P.; Nergiz, I.; Herrmann, W.; Özcan, M. Influence of Various Surface-Conditioning Methods on the Bond Strength of Metal Brackets to Ceramic Surfaces. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2003, 123, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.C., Jr.; Santos, M.J.; Rizkalla, A.S. Adhesive Cementation of Etchable Ceramic Esthetic Restorations. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2009, 75, 379–384. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, N.S.A.; Perdigão, J.H. Adhesive Resin Cements for Bonding Esthetic Restorations: A Review. Quintessence Dent. Technol. 2011, 34, 40–66. [Google Scholar]

- Aker Sagen, M.; Dahl, J.E.; Matinlinna, J.P.; Tibballs, J.E.; Rønold, H.J. The Influence of the Resin-Based Cement Layer on Ceramic-Dentin Bond Strength. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2021, 129, e12791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jivanescu, A.; Bara, A.; Sallai, M.; Candea, A.; Cuzic, C. Clinica Protezarii Fixe; Editura Victor Babes: Timisoara, Romania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guess, P.C.; Schultheis, S.; Bonfante, E.A.; Coelho, P.G.; Ferencz, J.L.; Silva, N.R. All-Ceramic Systems: Laboratory and Clinical Performance. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 55, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi, R.; Powers, J. Craig’s Restorative Dental Materials; Elsevier Inc.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, J.W.; Hughes, T.H. The Reinforcement of Dental Porcelain with Ceramic Oxides. Br. Dent. J. 1965, 119, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alla, R.K. Dental Materials Science; Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anusavice, K.J. Phillips’ Science of Dental Materials, 11th ed.; Elsevier, A division of Reed Elsevier India Pvt Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- IL, D. Recent Advances in Ceramics for Dentistry. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1996, 7, 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy, A.; Shenoy, N. Dental Ceramics: An Update. J. Conserv. Dent. 2010, 13, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.R.; Benetti, P. Ceramic Materials in Dentistry: Historical Evolution and Current Practice. Aust. Dent. J. 2011, 56, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiu, J.; Belli, R.; Lohbauer, U. Contemporary CAD/CAM Materials in Dentistry. Curr. Oral Health. Rep. 2019, 6, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Nakamura, T.; Matsumura, H.; Ban, S.; Kobayashi, T. Current Status of Zirconia Restoration. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2013, 57, 236–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinke, S.; Fischer, C. Range of Indications for Translucent Zirconia Modifications: Clinical and Technical Aspects. Quintessence Int. 2013, 44, 557–566. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Ahn, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, W.C. Effects of the Sintering Conditions of Dental Zirconia Ceramics on the Grain Size and Translucency. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2013, 5, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deubener, J.; Allix, M.; Davis, M.J.; Duran, A.; Höche, T.; Honma, T.; Komatsu, T.; Krüger, S.; Mitra, I.; Müller, R.; et al. Updated Definition of Glass-Ceramics. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2018, 481, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helvey, G.A. Classification of Dental Ceramics. Inside Dent 2013, 13, 62–76. [Google Scholar]

- de Freitas Vallerini, B.; Dantas Silva, L.D.; Villas-Bôas, M.O.C.; Peitl Filho, O.; Zanotto, E.D.; Pinelli, L.A.P. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of an Experimental Lithium Disilicate Dental Glass-Ceramic. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazerian, M.; Baino, F.; Fiume, E.; Migneco, C.; Alaghmandfard, A.; Sedighi, O.; DeCeanne, A.V.; Wilkinson, C.J.; Mauro, J.C. Glass-Ceramics in Dentistry: Fundamentals, Technologies, Experimental Techniques, Applications, and Open Issues. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 132, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, W.J. (Ed.) Dental Materials and Their Selection, 4th ed.; Quintessence Pub. Co.: Hanover Park, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.Y.; Pang, R.; Yang, J.; Fan, D.; Cai, H.; Jiang, H.B.; Han, J.; Lee, E.S.; Sun, Y. Overview of Several Typical Ceramic Materials for Restorative Dentistry. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 8451445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutejo, I.A.; Kim, J.; Zhang, S.; Gal, C.W.; Choi, Y.J.; Park, H.; Yun, H.S. Fabrication of Color-Graded Feldspathic Dental Prosthetics for Aesthetic and Restorative Dentistry. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warreth, A.; Elkareimi, Y. All-Ceramic Restorations: A Review of the Literature. Saudi. Dent. J. 2020, 32, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorulska, A.; Piszko, P.; Rybak, Z.; Szymonowicz, M.; Dobrzyński, M. Review on Polymer, Ceramic and Composite Materials for CAD/CAM Indirect Restorations in Dentistry-Application, Mechanical Characteristics and Comparison. Materials 2021, 14, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denry, I.; Holloway, J.A. Ceramics for Dental Applications: A Review. Materials 2010, 3, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traini, T.; Sinjari, B.; Pascetta, R.; Serafini, N.; Perfetti, G.; Trisi, P.; Caputi, S. The Zirconia-Reinforced Lithium Silicate Ceramic: Lights and Shadows of a New Material. Dent. Mater. J. 2016, 35, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriamporn, T.; Thamrongananskul, N.; Busabok, C.; Poolthong, S.; Uo, M.; Tagami, J. Dental zirconia can be etched by hydrofluoric acid. Dent. Mater. J. 2014, 33, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, S.S.; Quinn, G.D.; Quinn, J.B. Fractographic failure analysis of a Procera AllCeram crown using stereo and scanning electron microscopy. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrabeah, G.; Al-Sowygh, A.H.; Almarshedy, S. Use of Ultra-Translucent Monolithic Zirconia as Esthetic Dental Restorative Material: A Narrative Review. Ceramics 2024, 7, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, L.; Grădinaru, M.; Rîcă, R.; Mărășescu, P.; Stan, M.; Manolea, H.; Ionescu, A.; Moraru, I. Zirconia Use in Dentistry—Manufacturing and Properties. Curr. Health. Sci. J. 2019, 45, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Binici Aygün, E.; Kaynak Öztürk, E.; Tülü, A.B.; Turhan Bal, B.; Karakoca Nemli, S.; Bankoğlu Güngör, M. Factors Affecting the Color Change of Monolithic Zirconia Ceramics: A Narrative Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, S. Development and Characterization of Ultra-High Translucent Zirconia Using New Manufacturing Technology. Dent. Mater. J. 2023, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano Ii, R. Ceramics Overview. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 232, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Ghulam, O.; Krsoum, M.; Binmahmoud, S.; Taher, H.; Elmalky, W.; Zafar, M.S. Revolution of Current Dental Zirconia: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, S.; Jafarian, Z. A Review on Translucent Zirconia. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2018, 26, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Denry, I.; Kelly, J.R. State of the Art of Zirconia for Dental Applications. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güth, J.F.; Stawarczyk, B.; Edelhoff, D.; Liebermann, A. Zirconia and Its Novel Compositions: What Do Clinicians Need to Know? Quintessence Int. 2019, 50, 512–520. [Google Scholar]

- Kui, A.; Manziuc, M.; Petruțiu, A.; Buduru, S.; Labuneț, A.; Negucioiu, M.; Chisnoiu, A. Translucent Zirconia in Fixed Prosthodontics—An Integrative Overview. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshpooy, M.; Pournaghi Azar, F.; Alizade Oskoee, P.; Bahari, M.; Asdagh, S.; Khosravani, S.R. Color Agreement Between Try-In Paste and Resin Cement: Effect of Thickness and Regions of Ultra-Translucent Multilayered Zirconia Veneers. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospects. 2019, 13, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardhaman, S.; Borba, M.; Kaizer, M.R.; Kim, D.K.; Zhang, Y. Optical and Mechanical Properties of the Multi-Transition Zones of a Translucent Zirconia. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2024, 37, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano Moncayo, A.M.; Peñate, L.; Arregui, M.; Giner-Tarrida, L.; Cedeño, R. State of the Art of Different Zirconia Materials and Their Indications According to Evidence-Based Clinical Performance: A Narrative Review. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongkiatkamon, S.; Rokaya, D.; Kengtanyakich, S.; Peampring, C. Current Classification of Zirconia in Dentistry: An Updated Review. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamo, E.T.P.; Cardoso, K.B.; Lino, L.F.O.; Campos, T.M.B.; Monteiro, K.N.; Cesar, P.F.; Genova, L.A.; Thim, G.P.; Coelho, P.G.; Bonfante, E.A. Alumina-Toughened Zirconia for Dental Applications: Physicochemical, Mechanical, Optical, and Residual Stress Characterization After Artificial Aging. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2021, 109, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, S. Reliability and Properties of Core Materials for All-Ceramic Dental Restorations. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2008, 44, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, T.; Tasaka, A.; Yoshinari, M.; Sakurai, K. Fatigue Strength of Ce-TZP/Al2O3 Nanocomposite with Different Surfaces. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ille, C.-E.; Jivănescu, A.; Pop, D.; Stoica, E.T.; Flueras, R.; Talpoş-Niculescu, I.-C.; Cosoroabă, R.M.; Popovici, R.-A.; Olariu, I. Exploring the Properties and Indications of Chairside CAD/CAM Materials in Restorative Dentistry. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lawn, B.R. Novel Zirconia Materials in Dentistry. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Hamdi, K.; Ali, A.I.; Al-Zordk, W.; Hasab Mahmoud, S. Clinical Performance Comparison Between Lithium Disilicate and Hybrid Resin Nano-Ceramic CAD/CAM Onlay Restorations: A Two-Year Randomized Clinical Split-Mouth Study. Odontology 2024, 112, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano Ii, R. Ceramics Overview: Classification by Microstructure and Processing Methods. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2010, 31, 682–684. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, B.; Reiss, W.W. Ereignisanalyse und Klinische Langzeitergebnisse mit Cerec-Keramikinlays. Dtsch. Zahnarztl. Z. 1998, 53, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Höland, W.; Schweiger, M.; Frank, M.; Rheinberger, V. A comparison of the microstructure and properties of the IPS Empress 2 and the IPS Empress Glass Ceramics. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 53, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guazzato, M.; Albakry, M.; Ringer, S.P.; Swain, M.V. Strength, Fracture Toughness and Microstructure of a Selection of All-Ceramic Materials. Part I. Pressable and Alumina Glass-Infiltrated Ceramics. Dent. Mater. 2004, 20, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albakry, M.; Guazzato, M.; Swain, M.V. Biaxial Flexural Strength, Elastic Moduli, and X-Ray Diffraction Characterization of Three Pressable All-Ceramic Materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 89, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarczyk, A.; Lauer, H.C.; Sorensen, J.A. In Vitro Shear Bond Strength of Cementing Agents to Fixed Prosthodontic Restorative Materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2004, 92, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.R. Interpenetrating Phase Composites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1992, 75, 739–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, R.; Catapano, S.; D’Elia, A. A Clinical Evaluation of In-Ceram Crowns. Int. J. Prosthodont. 1995, 8, 320–323. [Google Scholar]

- Pröbster, L.; Diehl, J. Slip casting alumina ceramics for crown and bridge restorations. Quintessence Int. 1992, 23, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, E.A.; McLaren, S.J. High Strength Alumina Crown and Bridge Substructures Generated Using Copy Milling Technology. Quintessence Dent. Technol. 1995, 18, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, E.A.; White, S.N. Survival of In-Ceram Crowns in a Private Practice: A Prospective Clinical Trial. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2000, 83, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, M.; Razzoog, M.E.; Odén, A.; Hegenbarth, E.A.; Langer, B. Procera Aluminum Oxide Ceramics: A New Way to Achieve Stability, Precision, and Esthetics in All-Ceramic Restorations. Quint. Dent. Technol. 1996, 20, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sailer, I.; Fehér, A.; Filser, F.; Gauckler, L.; Lüthy, H.; Hämmerle, C.H. Five-Year Clinical Results of Zirconia Frameworks for Posterior Fixed Partial Dentures. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2007, 20, 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- Raigrodski, A.J.; Chiche, G.J.; Potiket, N.; Hochstedler, J.L.; Mohamed, S.E.; Billiot, S.; Mercante, D.E. The Efficacy of Posterior Three-Unit Zirconium-Oxide–Based Ceramic Fixed Partial Dental Prostheses: A Prospective Clinical Pilot Study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2006, 96, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlwend, A.; Schärer, P. Die Empress-Technik—Ein Neues Verfahren zur Herstellung von Vollkeramischen Kronen, Inlays und Facetten. Quintessenz Zahntech. 1990, 16, 966–978. [Google Scholar]

- Höland, W.; Frank, M. IPS Empress Glaskeramik. In Metallfreie Restaurationen aus Presskeramik; Haller, B., Bischoff, H., Eds.; Quintessenz: Berlin, Germany, 1993; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzberger, C.; Apel, E.; Höland, W.; Peschke, A.; Rheinberger, V. Properties and Clinical Application of Three Types of Dental Glass-Ceramics and Ceramics for CAD-CAM Technologies. Materials 2010, 3, 3700–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duret, F.; Blouin, J.-L.; Duret, B. CAD-CAM in Dentistry. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1988, 117, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarone, F.; Russo, S.; Sorrentino, R. From Porcelain-Fused-to-Metal to Zirconia: Clinical and Experimental Considerations. Dent. Mater. 2011, 27, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizkalla, A.S.; Jones, D.W. Mechanical Properties of Commercial High Strength Ceramic Core Materials. Dent. Mater. 2004, 20, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizkalla, A.S.; Jones, D.W. Indentation Fracture Toughness and Dynamic Elastic Moduli for Commercial Feldspathic Dental Porcelain Materials. Dent. Mater. 2004, 20, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venclíkova, Z.; Benada, O.; Bártova, J.; Joska, L.; Mrklas, L. Metallic Pigmentation of Human Teeth and Gingiva: Morphological and Immunological Aspects. Dent. Mater. J. 2007, 26, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehulic, K.; Prlić, A.; Komar, D.; Prskalo, K. The Release of Metal Ions in the Gingival Fluid of Prosthodontic Patients. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2005, 39, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zarone, F.; Di Mauro, M.I.; Ausiello, P.; Ruggiero, G.; Sorrentino, R. Current Status on Lithium Disilicate and Zirconia: A Narrative Review. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sailer, I.; Lawn, B.R. Fatigue of Dental Ceramics. J. Dent. 2013, 41, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, I.; Hämmerle, C.H. Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial of Zirconia Ceramic and Metal-Ceramic Posterior Fixed Dental Prostheses: A 3-Year Follow-Up. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2009, 22, 553–560. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, M. Ten-Year Outcome of Three-Unit Fixed Dental Prostheses Made from Monolithic Lithium Disilicate Ceramic. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2012, 143, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, C.; Sailer, I.; Hämmerle, C.H. 10-Year Clinical Outcomes of Fixed Dental Prostheses with Zirconia Frameworks. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2011, 14, 183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Damage Accumulation and Fatigue Life of Particle-Abraded Ceramics. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2006, 19, 442–448. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Deep-Penetrating Conical Cracks in Brittle Layers from Hydraulic Cyclic Contact. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2005, 73, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, P.K. Non-Metallic Biomaterials for Tooth Repair and Replacement. In Processing and Bonding of Dental Ceramics; Cattell, M.J., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 125–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jbeniany, M. Bonding Protocol for Indirect Ceramic Restorations in Posterior Teeth: Recommendations for Success. Master’s Dissertation, Instituto Universitário Egas Moniz, Almada, Portugal, 2024. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/52270 (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Saint-Jean, S. Dental Glasses and Glass-Ceramics. In Advanced Ceramics for Dentistry; Cattell, M.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2014; pp. 255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Papanagiotou, H.P.; Morgano, S.M.; Giordano, R.A.; Pober, R. In Vitro Evaluation of Low-Temperature Aging Effects and Finishing Procedures on the Flexural Strength and Structural Stability of Y-TZP Dental Ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2006, 96, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarczyk, A.; Ottl, P.; Lauer, H.C.; Kuretzky, T. A Clinical Report and Overview of Scientific Studies and Clinical Procedures Conducted on the 3M ESPE Lava All-Ceramic System. J. Prosthodont. 2005, 14, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucena, M.; Relvas, A.; Lefrançois, M.; Azevedo, M.; Sotelo, P.; Sotelo, L. Resin Matrix Ceramics—Mechanical, Aesthetic and Biological Properties. RGO—Rev. Gaúcha Odontologia 2021, 69, e20210018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, E.; Göktepe, B. Optical Properties of Novel Resin Matrix Ceramic Systems at Different Thicknesses. Cumhuriyet Dent. J. 2019, 22, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sita Ramaraju, D.V. A Review of Conventional and Contemporary Luting Agents Used in Dentistry. Am. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Farias, D.C.S.; Gonçalves, L.M.; Walter, R.; Chung, Y.; Blatz, M.B. Bond Strengths of Various Resin Cements to Different Ceramics. Braz. Oral Res. 2019, 33, e095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K. Influence of Cleaning Methods on the Bond Strength of Resin Cement to Saliva-Contaminated Lithium Disilicate Ceramic. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 2091–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzic, C.; Jivanescu, A.; Negru, R.M.; Hulka, I.; Rominu, M. The Influence of Hydrofluoric Acid Temperature and Application Technique on Ceramic Surface Texture and Shear Bond Strength of an Adhesive Cement. Materials 2023, 16, 4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, G.; Hardan, L.; Kassis, C.; Bourgi, R.; Cuevas-Suárez, C.E.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M.; Mancino, D.; Haikel, Y.; Kharouf, N. Shelf Life and Storage Conditions of Universal Adhesives: A Literature Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josic, U.; Mazzitelli, C.; Maravic, T.; Radovic, I.; Jacimovic, J.; Mancuso, E.; Florenzano, F.; Breschi, L.; Mazzoni, A. The Influence of Selective Enamel Etch and Self-Etch Mode of Universal Adhesives’ Application on Clinical Behavior of Composite Restorations Placed on Non-Carious Cervical Lesions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdigão, J. Current Perspectives on Dental Adhesion: (1) Dentin Adhesion—Not There Yet. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2020, 56, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miotti, L.L.; Follak, A.C.; Montagner, A.F.; Pozzobon, R.T.; da Silveira, B.L.; Susin, A.H. Is Conventional Resin Cement Adhesive Performance to Dentin Better Than Self-Adhesive? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Laboratory Studies. Oper. Dent. 2020, 45, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, A.P.; Carvalho, R.M. Dental Cements for Luting and Bonding Restorations: Self-Adhesive Resin Cements. Dent. Clin. North Am. 2017, 61, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltoukhy, R.I.; Elkaffas, A.A.; Ali, A.I.; Mahmoud, S.H. Indirect Resin Composite Inlays Cemented with a Self-Adhesive, Self-Etch or a Conventional Resin Cement Luting Agent: A 5 Years Prospective Clinical Evaluation. J. Dent. 2021, 112, 103740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegoraro, T.A.; da Silva, N.R.; Carvalho, R.M. Cements for Use in Esthetic Dentistry. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 51, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovic, I.; Monticelli, F.; Goracci, C.; Vulicevic, Z.R.; Ferrari, M. Self-Adhesive Resin Cements: A Literature Review. J. Adhes. Dent. 2008, 10, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Marghalani, H.Y. Resin-Based Dental Composite Materials. In Handbook of Bioceramics and Biocomposites; Antoniac, I., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, G.; Braga, R.R.; Cesar, P.F.; Lopes, G.C. Correlation Between Clinical Performance and Degree of Conversion of Resin Cements: A Literature Review. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2015, 23, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshabib, A.A. A Comprehensive Review of Resin Luting Agents: Bonding Mechanisms and Polymerisation Reactions. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidalgo-Pereira, R.; Torres, O.; Carvalho, Ó.; Silva, F.S.; Catarino, S.O.; Özcan, M.; Souza, J.C.M. A Scoping Review on the Polymerization of Resin-Matrix Cements Used in Restorative Dentistry. Materials 2023, 16, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhafyan, M.; Silikas, N.; Watts, D.C. Influence of Curing Modes on Monomer Elution, Sorption and Solubility of Dual-Cure Resin-Cements. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falacho, R.I.; Marques, J.A.; Palma, P.J.; Roseiro, L.; Caramelo, F.; Ramos, J.C.; Guerra, F.; Blatz, M.B. Luting Indirect Restorations with Resin Cements Versus Composite Resins: Effects of Preheating and Ultrasound Energy on Film Thickness. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 34, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magne, P.; Razaghy, M.; Carvalho, M.A.; Soares, L.M. Luting of Inlays, Onlays, and Overlays with Preheated Restorative Composite Resin Does Not Prevent Seating Accuracy. Int. J. Esthet. Dent. 2018, 13, 318–332. [Google Scholar]

| Components | Functions |

|---|---|

| Feldspar | The lowest fusing component melts and flows first during firing, enabling these components to solidify. |

| Silica | Strengthens the prosthodontic ceramic restoration and maintains its original form at the temperature typically used to fire porcelain, adding stability to the mass during heating by acting as a framework for the other components. |

| Kaolin | It is used as a bond; at the same time, it acts on unfired porcelain by making it more mouldable and gives opacity to finished porcelain. |

| Glass modifiers | They function as flux and compromise the silica network’s integrity. |

| Colour pigments | To create the restoration, the suitable shade. |

| Zr/Ce/Sn oxides and uranium oxide | To generate the right amount of opacity. |

| Composition | Strength | Translucency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VITA In-Ceram™ SPINELL | Alumina and magnesia | 400 MPa | High translucency |

| VITA In-Ceram™ ALUMINA | 80%, alumina | 500 MPa | Optimal translucency |

| VITA In-Ceram™ ZIRCONIA | Alumina and zirconia | 600 MPa | High opacity |

| Material | Fabrication Method | Etchable |

|---|---|---|

| Glass matrix ceramics | ||

| Felspathic ceramics | Refractory die, platinum foil, press | YES |

| Synthetic ceramics | ||

| Leucite-based | Press or CAD/CAM | YES |

| Lithium disilicate and derivatives | Press or CAD/CAM | YES |

| Fluorapatite-based | Press or layering | YES |

| Glass-infiltrated | ||

| Alumina | CAD/CAM or Slipcasting | YES |

| Alumina and magnesium | CAD/CAM or Slipcasting | YES |

| Alumina and zirconia | CAD/CAM or Slipcasting | YES |

| Polycrystalline ceramics | ||

| Alumina | CAD/CAM | NO |

| Stabilised zirconia | CAD/CAM | NO |

| Zirconia-toughened alumina and alumina-toughened zirconia | CAD/CAM | NO |

| Resin matrix ceramics | ||

| Resin nanoceramics | CAD/CAM | NO |

| Glass ceramics in a resin interpenetrating polymer network | CAD/CAM | YES |

| Zirconia–silica in a resin interpenetrating polymer network | CAD/CAM | NO |

| Ceramic | Manufacturer | Clinical Indications |

|---|---|---|

| Feldspar | VITABLOCS, VITA Zahnfabrik: Mark I (1985); Mark II (1991); VITA Triluxe (2003); VITA Trilux forte (2007); VITA Real Life (2010). | Veneers, inlays, onlays, partial crowns, crowns (anterior and posterior area), veneering CAD/CAM material for multi-unit fixed partial restoration substructure made from oxide ceramic |

| Leucite | IPS Empress CAD, Ivoclar Vivadent (2006); IPS Empress CAD Multi | Veneers, inlays, onlays, partial crowns, and crowns (anterior and posterior area) |

| Lithium disilicate | IPS e.max CAD, Ivoclar Vivadent (2006) | Veneers, inlays, onlays, partial crowns, crowns (anterior and posterior area), hybrid abutments and crowns, 3-unit fixed partial dentures (anterior and premolar area), veneering CAD/CAM material for multi-unit fixed partial restoration substructure made from IPS e.max ZirCAD |

| Zirconia-lithium silicate | Celtra Duo, Dentsply (2013); VITA Suprinity VITA Zahnfabrik (2013) | Veneers, inlays, onlays, partial crowns, crowns (anterior and posterior area), implant-supported crown |

| Zirconia | Vita In-Ceram YZ VITA Zahnfabrik (2002); IPS e.max ZirCAD Ivoclar Vivadent (2006) | Crowns and multiple-unit fixed partial dentures (anterior and posterior area, curved and long-span), cantilever bridges, implant abutments, adhesive anterior bridges, primary telescope crowns, inlay bridge framework |

| All zirconia | Lava Plus High Translucency Zirconia 3M ESPE (2012); Cercon True Color, Dentsply, Degudent (2015); Zenostar Full Contour Zirconia Wieland Dental lvoclar Vivadent (2013). | Crowns and multiple-unit fixed partial dentures (anterior and posterior area, curved and long-span), inlay bridge framework, primary telescope crowns, cantilever bridges, implant abutments, and adhesive anterior bridges |

| Hybrid | Lava Ultimate CAD/CAM Restorative, 3M ESPE (2011); VITA Enamic, VITA Zahnfabrik (2013); Vita Enamic multiColor (2017); CERASMART GC (2014). | Veneers, inlays, onlays, partial crowns, crowns (anterior and posterior area), implant-supported crowns |

| Material | Mechanical Properties | Optical Properties | Bonding | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Strength Resistance (MPa) | Toughness (MPa/m2) | Elesticity (GPa) | |||

| Feldspathic ceramics | 60–70 | 1.26 | 70 | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Lithium disilicate | 360 | 2.25–2.75 | 95–102 | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Leucite-based | 160 | 1.3 | 62–70 | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Fluorapatite-based | 90 | 0.7–1 | 60–80 | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate | 370–420 | 2.6 | 70–108 | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Ceramic Composition | Filler | Ceramic Surface Treatment Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Predominantly Glass Ceramic | Aluminium oxide | 10% HF for 1 min, rinse and dry, silane for 1 min, air dry |

| Particle-Filled Glass Ceramic | Leucite | 5% HF for 1 min, rinse and dry, silane for 1 min, air dry |

| Lithium disilicate | 5% HF for 20 s, rinse and dry, silane for 1 min, air dry | |

| Glass-infiltrated alumina | Air abrasion with tribochemical silica coating/aluminium oxide, 10MDP agent, air dry | |

| Polycrystalline Ceramic | Aluminium oxide | Air abrasion with aluminium oxide, 10MDP agent, air dry |

| Zirconium oxide | Air abrasion with 50-micrometre aluminium powder at 7 pounds per square inch, 10MDP agent, air dry |

| Resin Cement | Clinical Protocol | Materials Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Total-etch | Demineralization with 30–40% phosphoric acid, followed by adhesive application |

|

| Self-etch | Self-demineralizing primer, followed by pre-mixed cement application |

|

| Self-adhesive | A single component, phosphoric acid is included in the resin |

|

| Resin Cement | Polymerization Mechanism | Characteristics | Indications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photopolymerizable | Light-activated photo-initiators |

|

|

| Self-polymerizable | Chemical reaction |

|

|

| Dual dental cement | Light-activated photo-initiators and chemical reaction |

|

|

| Ceramic Material | Translucency and Opacity Characteristics | Cement Shade Considerations | Colour Management Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feldspathic Ceramics | High translucency, closely to the optical properties of natural enamel | Highly influenced by underlying tooth structure and cement shade. Neutral/slightly lighter shades are often preferred unless masking is needed | Tooth substrate shade modification with opaquer may be necessary if underlying discoloration is present. Thin veneers require precise cement shade selection |

| Leucite-Reinforced Ceramics | Moderate translucency, slightly more opaque than feldspathic | Cement shade still plays a significant role | May require opaquer in cases of significant underlying discoloration |

| Lithium Disilicate | Varies in translucency, from high translucency CAD/CAM blocks to high opacity blocks | Shade selection depends heavily on the block translucency. High translucency requires careful cement matching. Medium/high opacity offer more masking potential but can still be influenced by cement | For high translucency blocks, consider the underlying colour of the prepared tooth shade carefully, as it can significantly affect the final shade |

| Zirconia (Monolithic) | Opaquer than glass ceramics. Newer generations can have higher translucency | Cement shade has less of a dramatic effect due to higher opacity but can still influence the final value and subtle colour nuances, especially with more translucent zirconia. Consider shades that complement the ceramic | Surface staining of the zirconia can be used to achieve desired shade effects. Opaque cements can be used without significant risk of negatively impacting the aesthetic outcome in most cases |

| Zirconia (Veneered) | The veneering porcelain’s translucency dictates the final aesthetic | The cement primarily affects the underlying zirconia coping’s influence on the veneer’s colour. Opaque cements block out the zirconia substructure and allow the veneer’s shade to dominate. Cement at the margins can still be visible and should be considered | Opaque cements are often preferred for the coping. The veneering ceramics shade and thickness are the primary determinants of the final visible colour |

| Alumina | High opacity | Cement shade has the least impact. The material masks the underlying tooth colour, but at the restoration margins, where if visible, the resin cement can impact the final appearance | Surface staining can be used for final shade adjustments |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuzic, C.; Rominu, M.; Pricop, A.; Urechescu, H.; Pricop, M.O.; Rotar, R.; Cuzic, O.S.; Sinescu, C.; Jivanescu, A. Clinician’s Guide to Material Selection for All-Ceramics in Modern Digital Dentistry. Materials 2025, 18, 2235. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18102235

Cuzic C, Rominu M, Pricop A, Urechescu H, Pricop MO, Rotar R, Cuzic OS, Sinescu C, Jivanescu A. Clinician’s Guide to Material Selection for All-Ceramics in Modern Digital Dentistry. Materials. 2025; 18(10):2235. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18102235

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuzic, Cristiana, Mihai Rominu, Alisia Pricop, Horatiu Urechescu, Marius Octavian Pricop, Raul Rotar, Ovidiu Stefan Cuzic, Cosmin Sinescu, and Anca Jivanescu. 2025. "Clinician’s Guide to Material Selection for All-Ceramics in Modern Digital Dentistry" Materials 18, no. 10: 2235. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18102235

APA StyleCuzic, C., Rominu, M., Pricop, A., Urechescu, H., Pricop, M. O., Rotar, R., Cuzic, O. S., Sinescu, C., & Jivanescu, A. (2025). Clinician’s Guide to Material Selection for All-Ceramics in Modern Digital Dentistry. Materials, 18(10), 2235. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18102235