Realizing the Creep and Damage Effect on Masonry Panel Design Based on Reliability Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

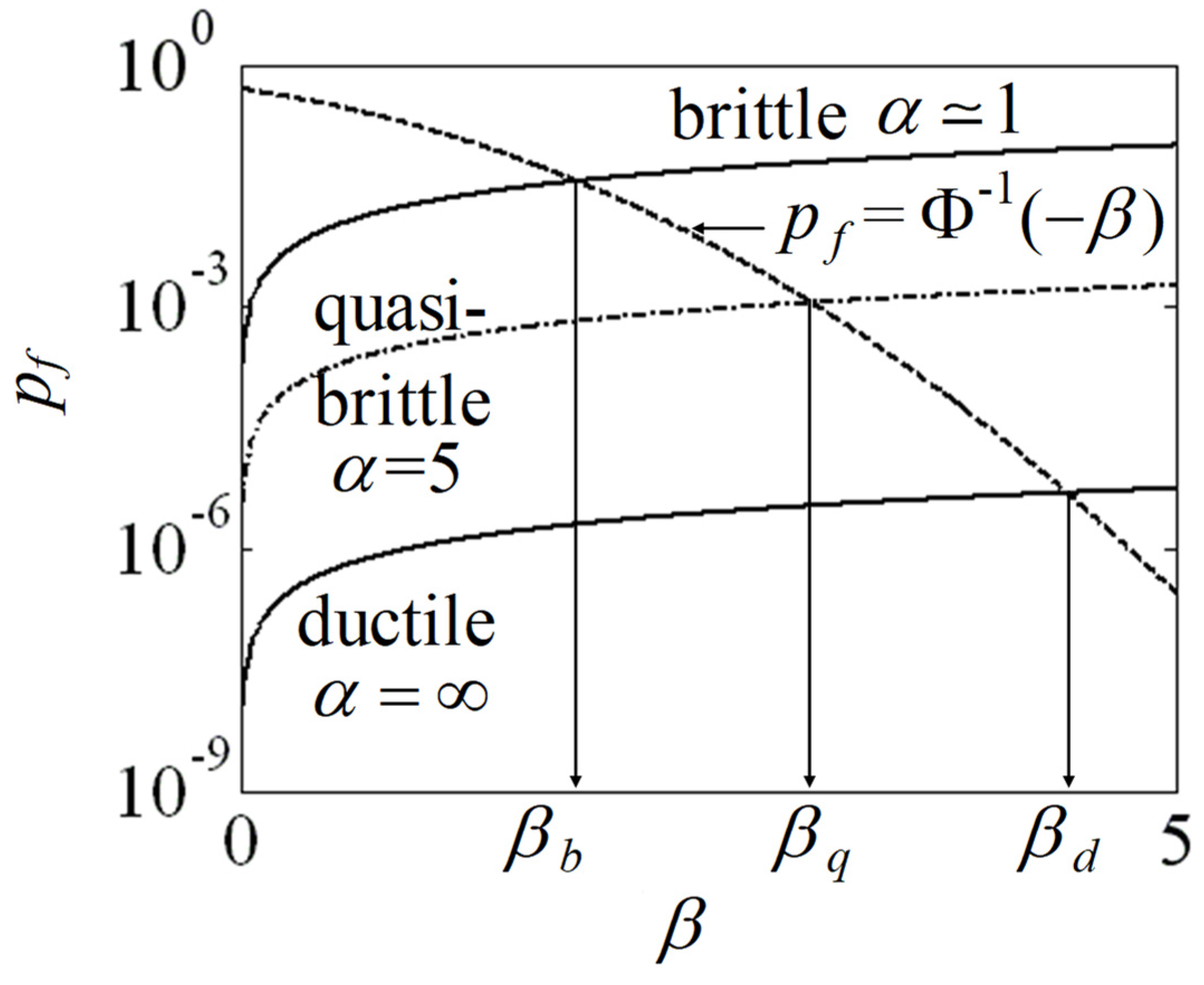

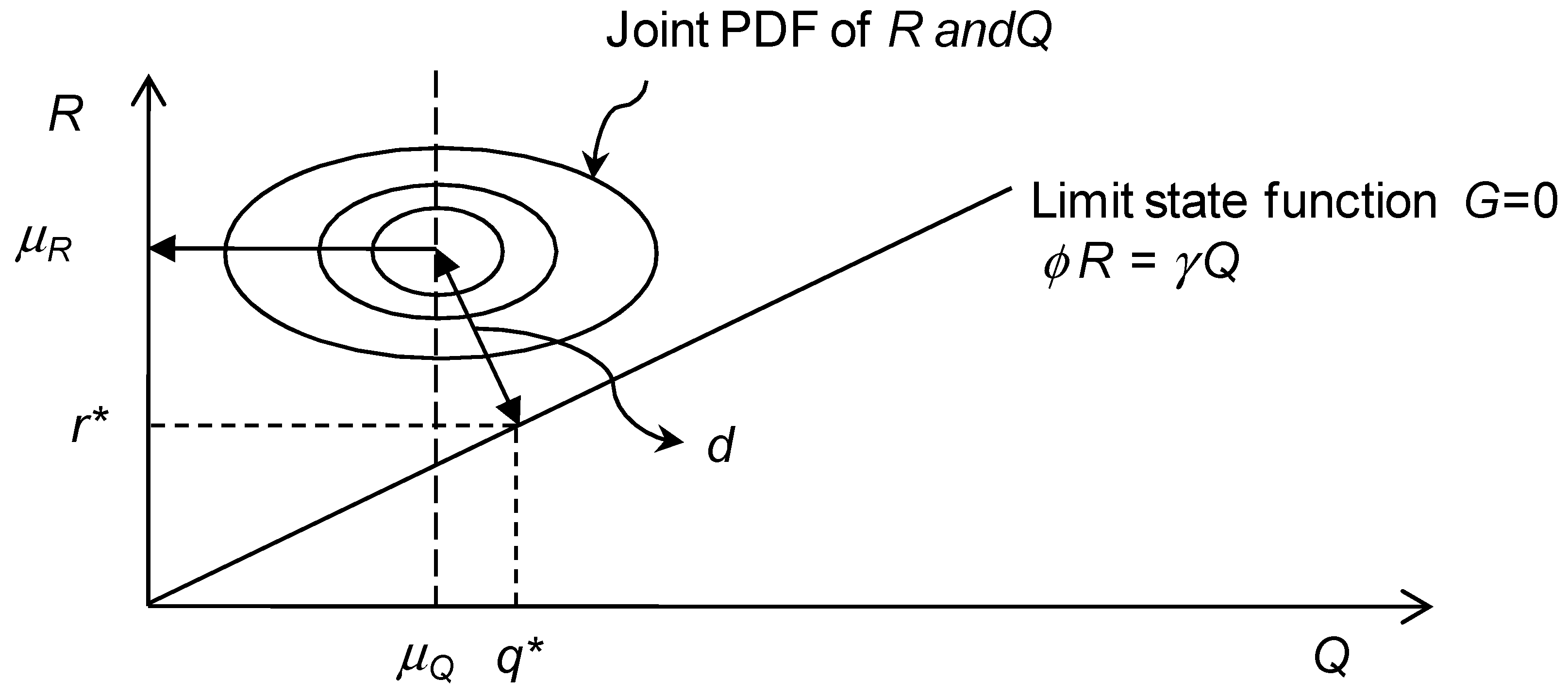

System Reliability Analysis

- BS1 = survival of B1 (brick in Part 1), MS1 = survival of M1 (mortar in Part 1);

- BS2 = survival of B2 (brick in Part 2), MS2 = survival of M2 (mortar in Part 2).

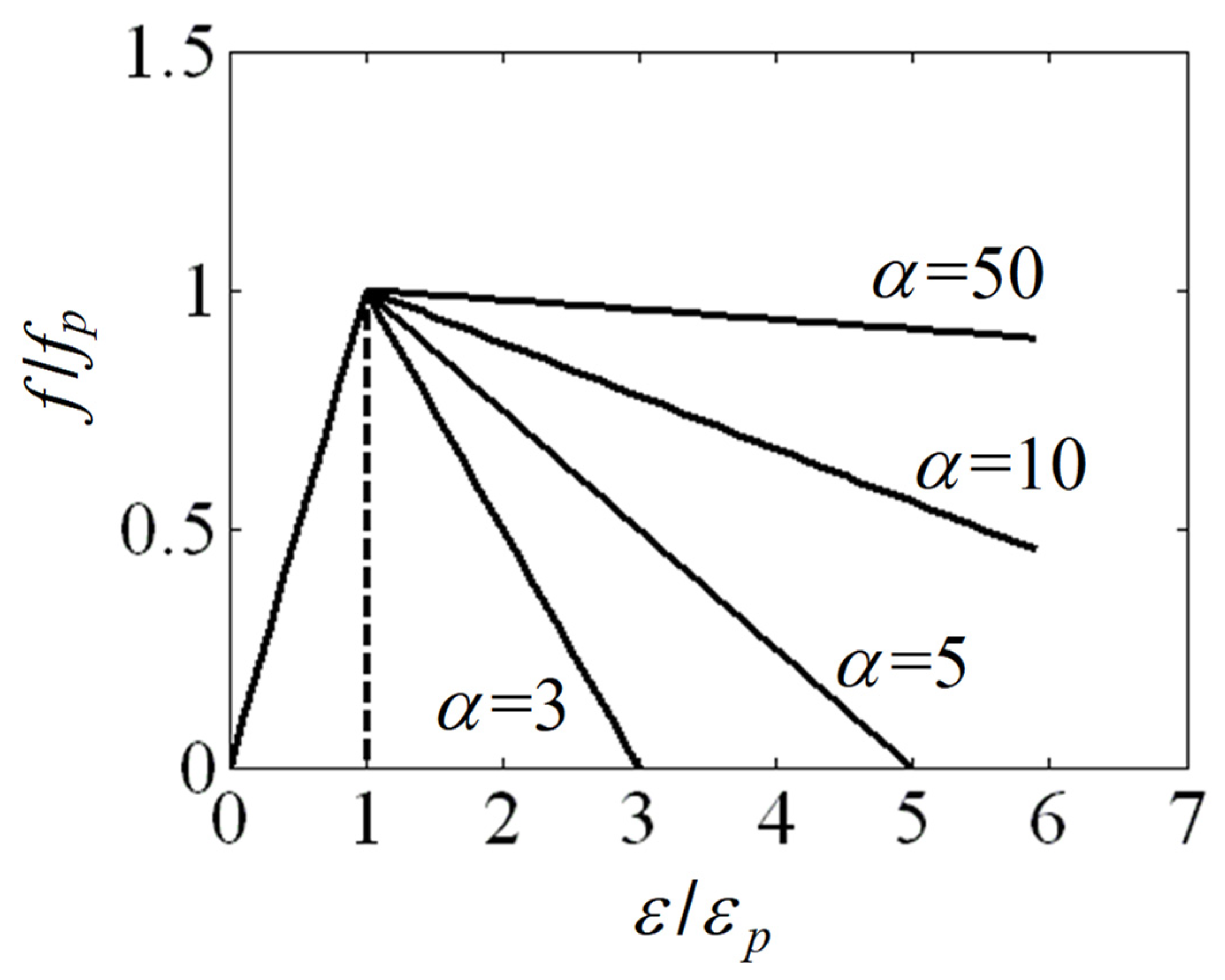

3. Composite Materials Incorporating Creep

4. Transformation Method to Calibrate Partial Safety Factors

5. Case Study

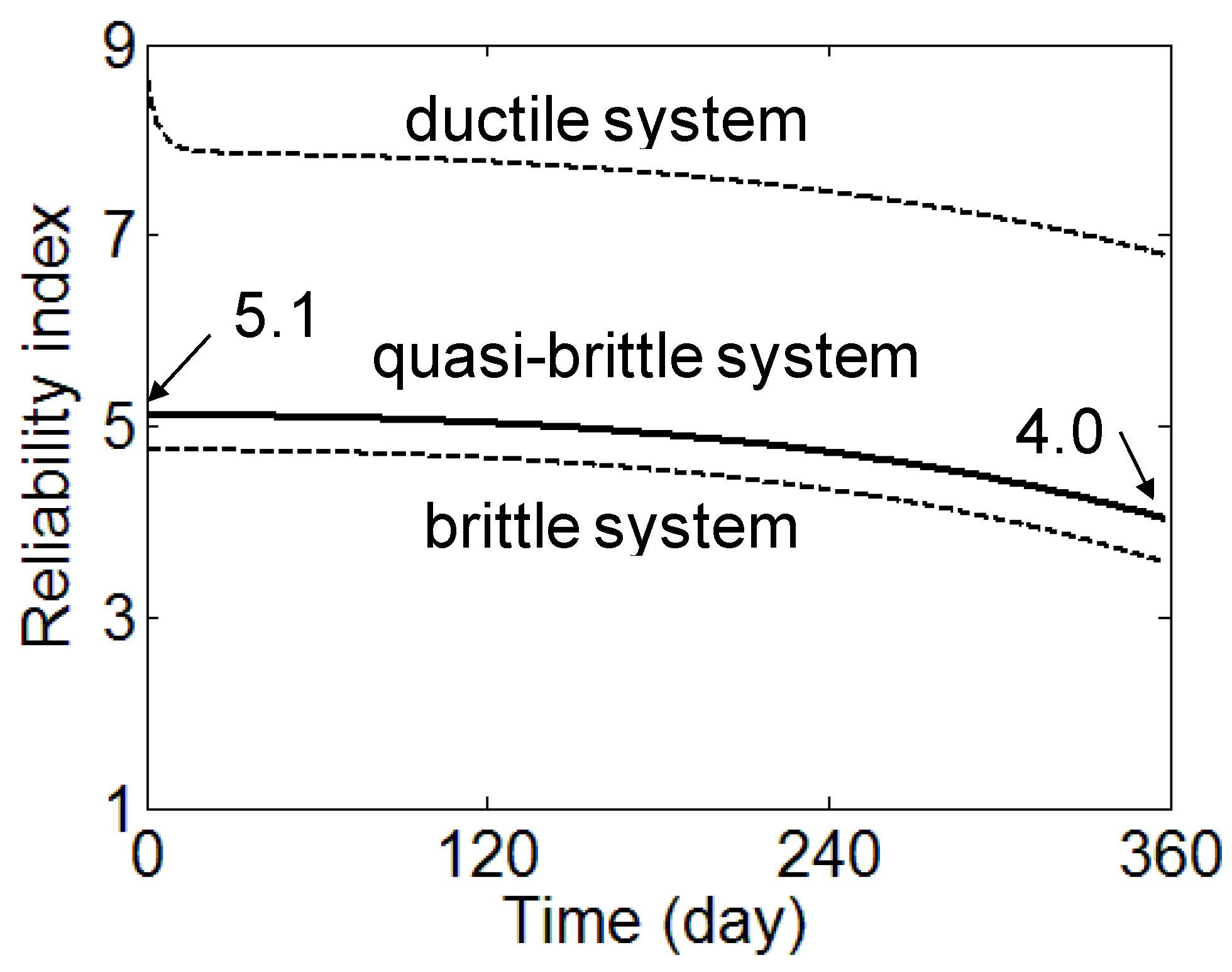

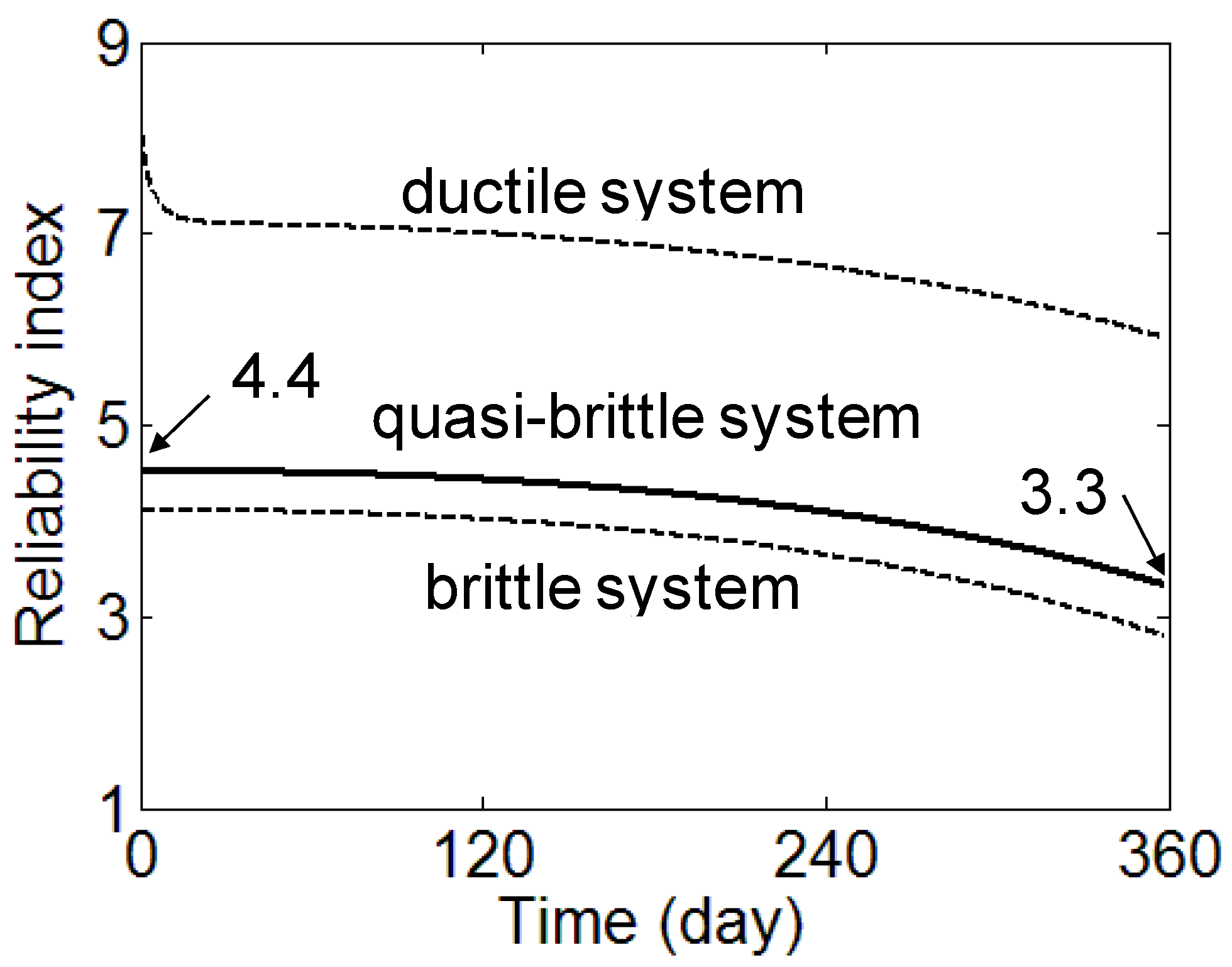

6. Results and Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghali, A.; Favre, R. Concrete Structures: Stresses and Deformation, 2nd ed.; E & FN SPON: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Binda, L.; Anzani, A.; Gioda, G. An Analysis of The Time-Dependent Behaviour of Masonry Walls. In Proceedings of the 9th International Brick/Block Masonry Conference, Berlin, Germany, 13–16 October 1991; Volume 2, pp. 1058–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Wallo, E.; Kesler, C. Prediction of creep in structural concrete. In Engineering, Materials Science; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Shrive, N.; Taha, M. Effects of Creep on New Masonry Structures. In Engineering, Materials Science; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.S.; Wang, Y.F.; Mao, Z.K. Creep effects on dynamic behavior of concrete filled steel tube arch bridge. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2011, 37, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, D. Creep-Effect on Mechanical Behavior of Concrete Confined by FRP under Axial Compression. In Engineering, Materials Science; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Neville, A.M.; Dilger, W.H.; Brooks, J.J. Creep of Plain and Structural Concrete, 1st ed.; Construction Press: England, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Lenczner, D. Creep in Model Brickwork. In Proceedings of Designing Engineering and Construction with Masonry Products; Johnston, F.B., Ed.; Gulf Publishing Company: Houston, TX, USA, 1969; pp. 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Shrive, N.G. Effects of Time Dependent Movements in Composite and Post-tensioned Masonry. Mason. Int. 1988, 2, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Shrive, N.G.; Sayed-Ahmed, E.Y.; Tilleman, D. Creep Analysis of Clay Masonry Assemblages. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 1997, 24, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda Taha, M.M.; Noureldin, A.; El-Sheimy, N.; Shrive, N.G. Artificial Neural Networks for Predicting Creep with An Example Application to Structural Masonry. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2003, 30, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zijl, G.P.A.G. A Numerical Formulation for Masonry Creep, Shrinkage and Cracking; Series 11, Engineering Mechanisms 01; Delft University Press: Delft, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shrive, N.G.; England, G.L. Elastic, creep and shrinkage behaviour of masonry. Int. J. Mason. Constr. 1981, 1, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- England, G.L. Steady-State Stresses in Concrete Structures Subjected to Sustained Loads and Temperatures, Parts I and II. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1966, 3, 547–65 & 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, T.J. Fuzzy Logic with Engineering Applications, 2nd ed.; WILEY: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Melchers, R.E. Structural Reliability Analysis and Prediction, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, J.G. Safety and Limit States Design for Reinforced Concrete. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 1976, 3, 484–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.S.; Collins, K. Reliability of Structures; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, A.; Murray, D.W. Time Dependent Reinforced Concrete Slab Deflections. J. Struct. Div. 1974, 100, 1911–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda Taha, M.M.; Shrive, N.G. A Model of Damage and Creep Interaction in A Quasi-Brittle Composite Material Under Axial Loading. J. Mech. 2006, 22, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Reda Taha, M.M. Integrating Creep and Damage in Modeling Historical Masonry: A Numerical Investigation. In Proceedings of the 5th ASCE International Engineering and Construction Conference (IECC’5), Irvine, CA, USA, 27–29 August 2008; pp. 291–297. [Google Scholar]

- ACI 530-05; Building Code Requirements for Masonry Structures. ACI: Miami, FL, USA, 2005.

- Glanville, J.I.; Hatzinikolas, M.A.; Ben-Omran, H.A. Engineered Masonry Design, Limit States Design; Winston House: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.J.; Reda Taha, M.M. Time-Dependent Reliability Analysis of Masonry Panels Under High Permanent Compressive Stresses. In Proceedings of the 11th Canadian Masonry Symposium, Toronto, ON, Canada, 30 May–3 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, J.G.; Wight, J.K. Reinforced Concrete: Mechanics and Design, 4th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Massart, T.J.; Peerlings RH, J.; Geers MG, D.; Gottcheiner, S. Mesocopic Modeling of Failure in Brick Masonry Ac-counting for Three-Dimensional Effects. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2005, 72, 1238–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Distribution | COV | Bias Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q | Normal | 14% | 1.1 |

| R | Normal | 12% | 1.1 |

| Material Properties and Geometries | Calculated Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

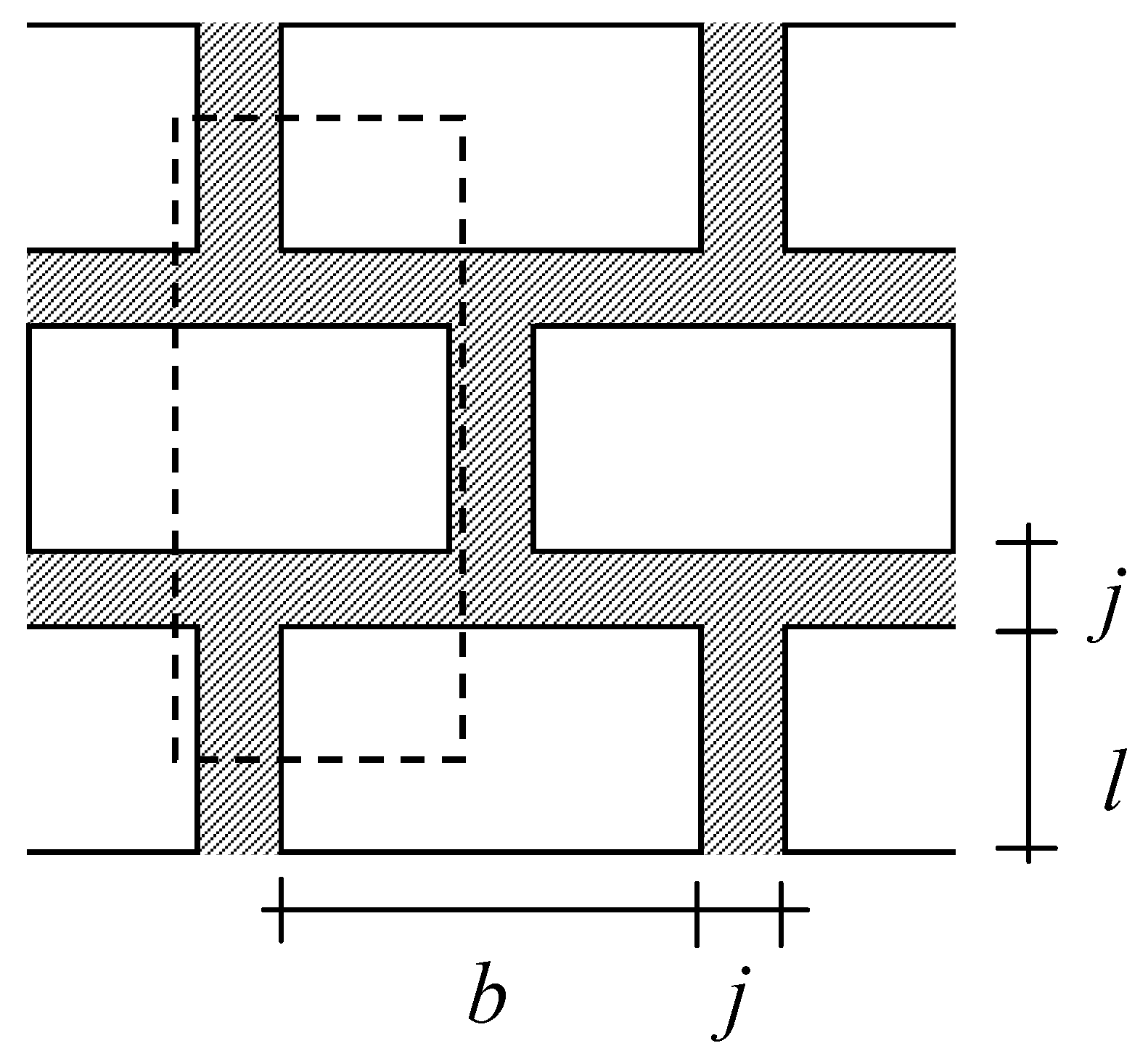

| B | 190 mm | c(t0) = Eb/Em(t0) | 5 |

| L | 57 mm | s1 = l/j | 5.7 |

| W | 90 mm | s2 = b/j | 19 |

| J | 10 mm | g(t0) | 0.113 |

| fm | 10 MPa | h(t0) | 9.258 |

| fb | 50 MPa | f1(t0) | 2.04 MPa |

| Em | 5 GPa | f2(t0) | 4.22 MPa |

| Eb | 25 GPa | Elastic strain | 269 μ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.J. Realizing the Creep and Damage Effect on Masonry Panel Design Based on Reliability Analysis. Materials 2024, 17, 2643. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112643

Kim JJ. Realizing the Creep and Damage Effect on Masonry Panel Design Based on Reliability Analysis. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2643. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112643

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jung Joong. 2024. "Realizing the Creep and Damage Effect on Masonry Panel Design Based on Reliability Analysis" Materials 17, no. 11: 2643. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112643

APA StyleKim, J. J. (2024). Realizing the Creep and Damage Effect on Masonry Panel Design Based on Reliability Analysis. Materials, 17(11), 2643. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112643