Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Biological Evaluation of Novel 5-Hydroxymethylpyrimidines

Abstract

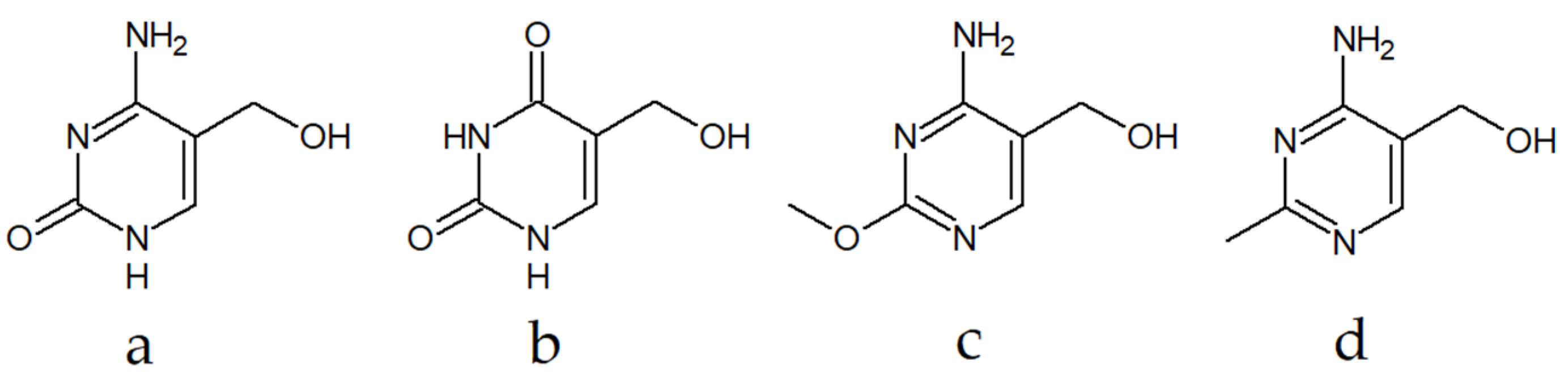

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis

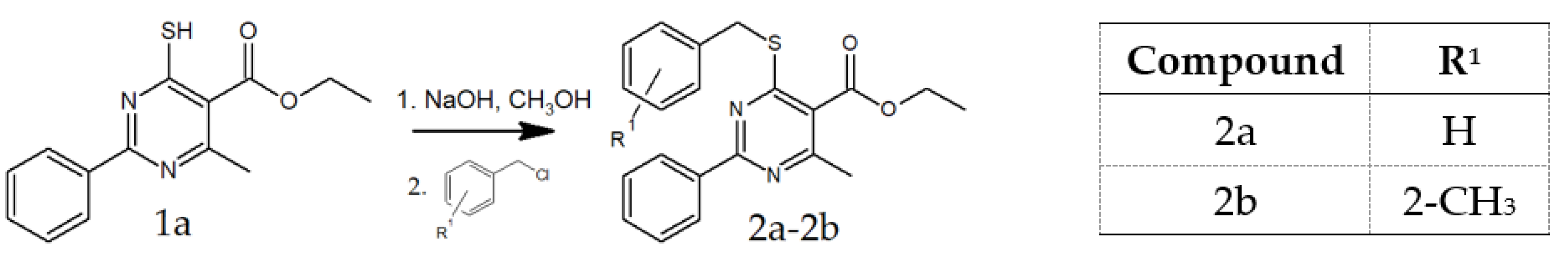

2.1.1. General Procedure for the Preparation of 2a and 2b

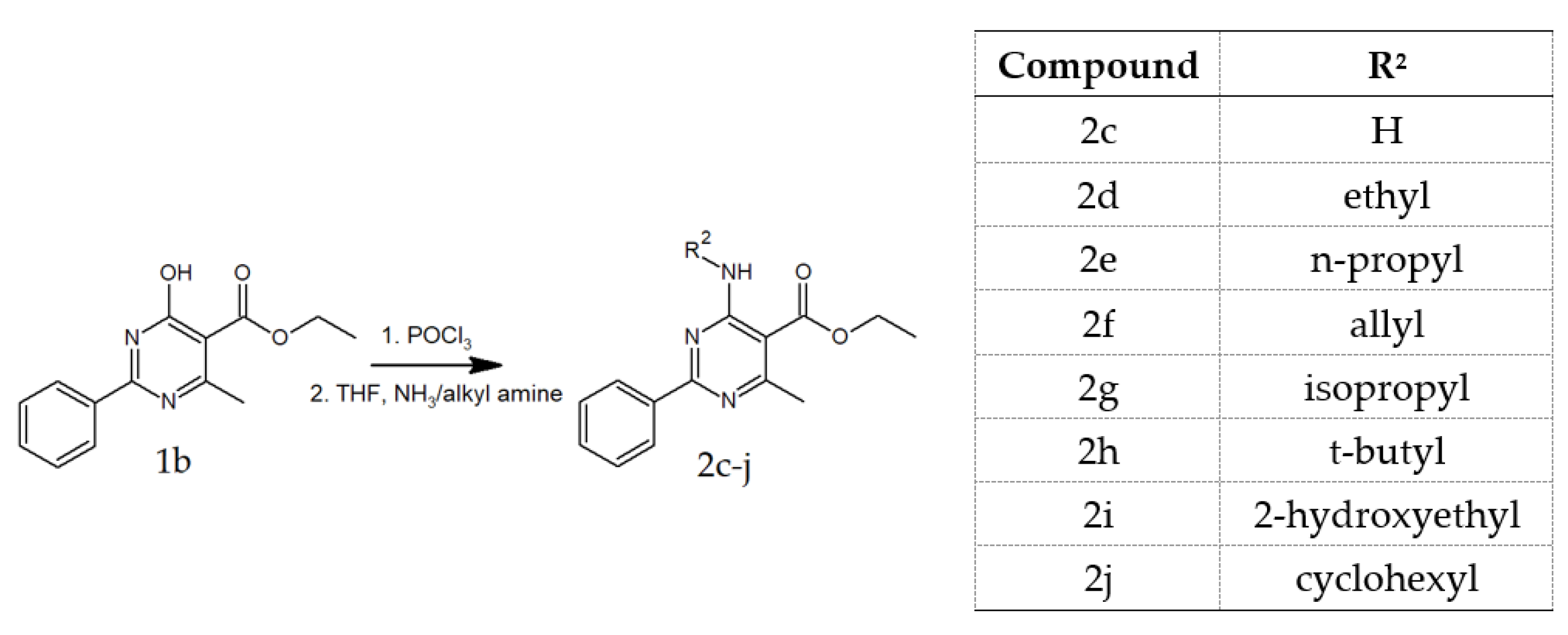

2.1.2. Preparation of Compounds 2c and 2d–2j

2.1.3. General Procedure for the Preparation of 2d–2j

2.1.4. General Procedure for the Preparation of 3a–3h

2.2. X-ray Structural Studies

2.3. Biological Activity Assays

2.3.1. Chemicals

2.3.2. Cell Culture

2.3.3. Neutral Red Uptake Assay

2.3.4. Microbiology

2.3.5. Statistical Analysis

2.4. In Silico Analysis

2.4.1. ADME Analysis

2.4.2. Molecular Docking Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. Crystal Structures of Compounds 3c and 3e–3h

3.3. Biological Activity Analysis

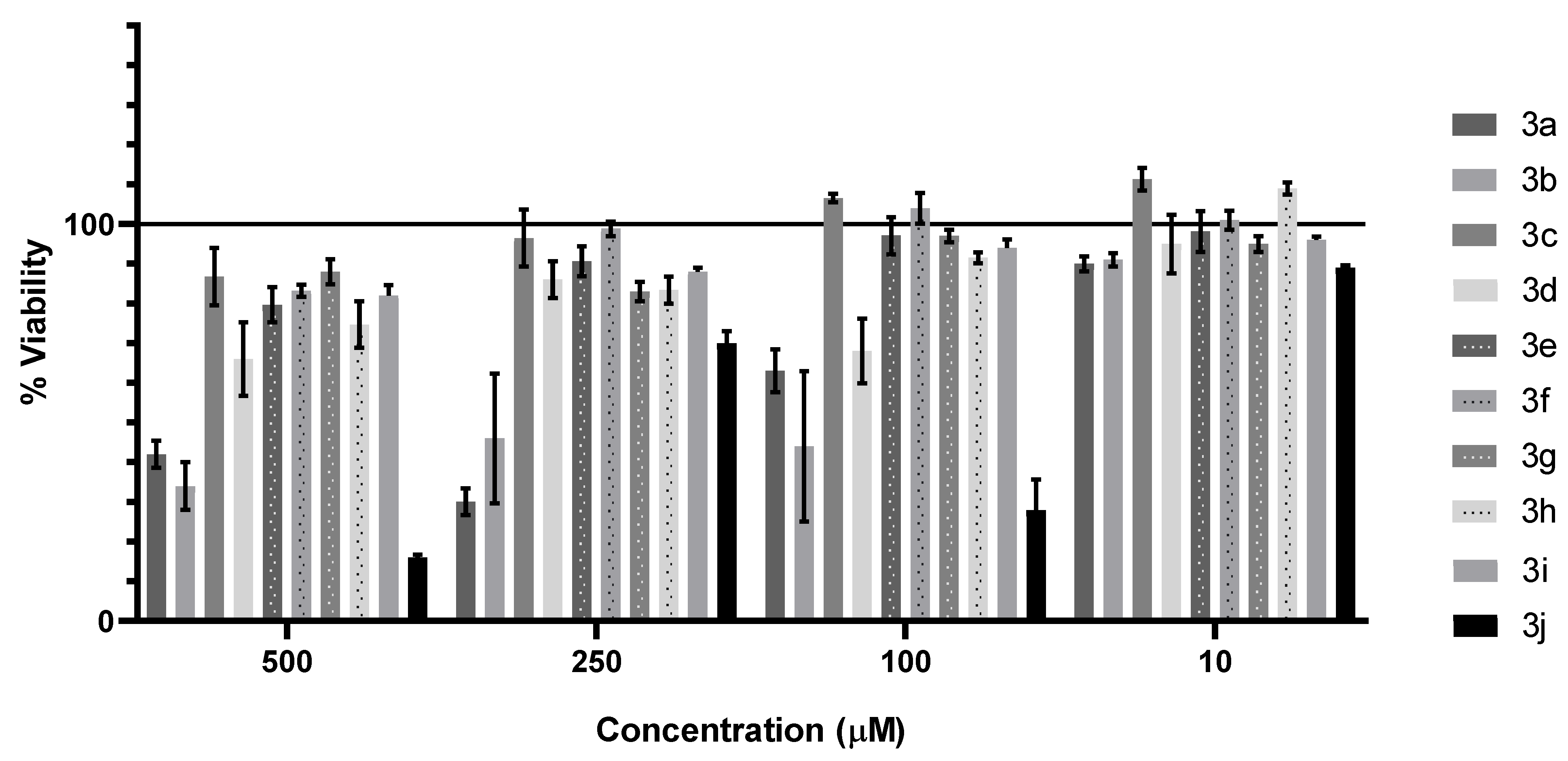

3.3.1. Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Effect

3.3.2. Antimicrobial Activity

3.4. In Silico Studies

3.4.1. ADME Analysis

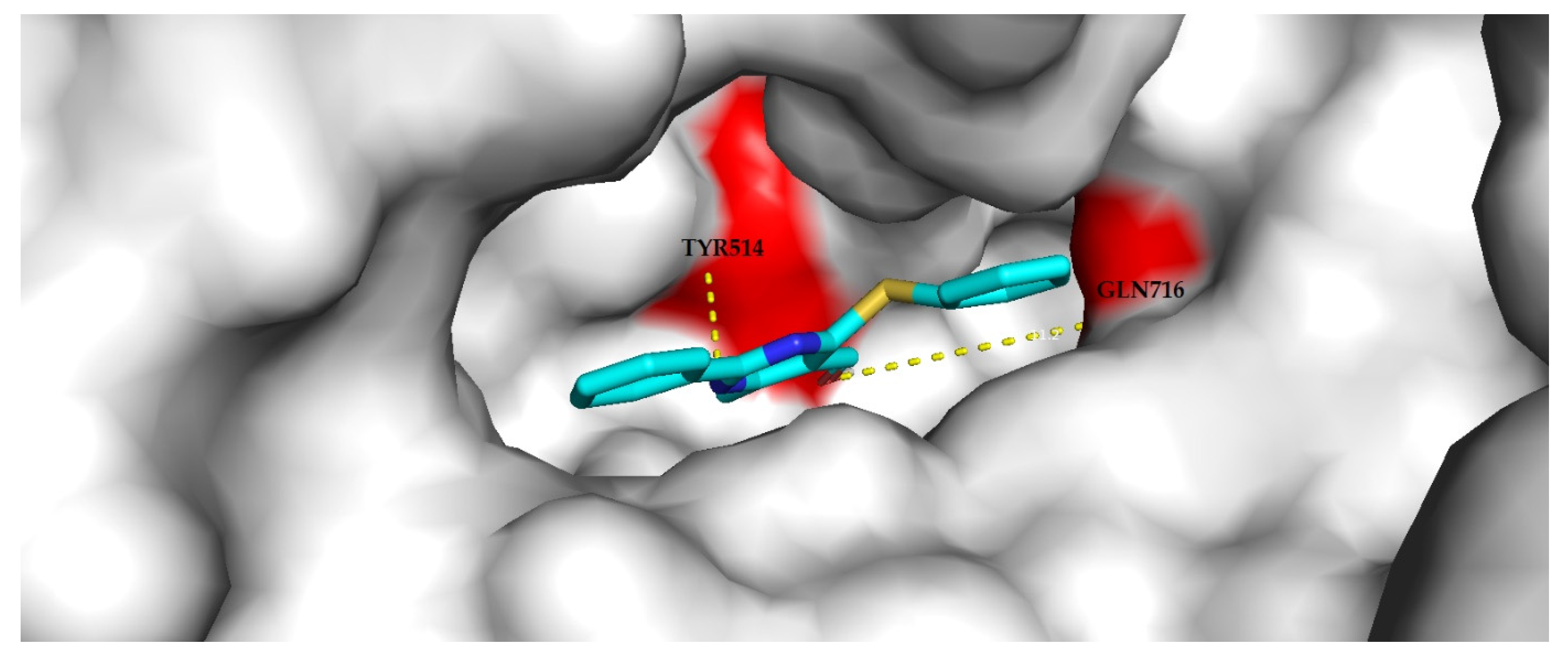

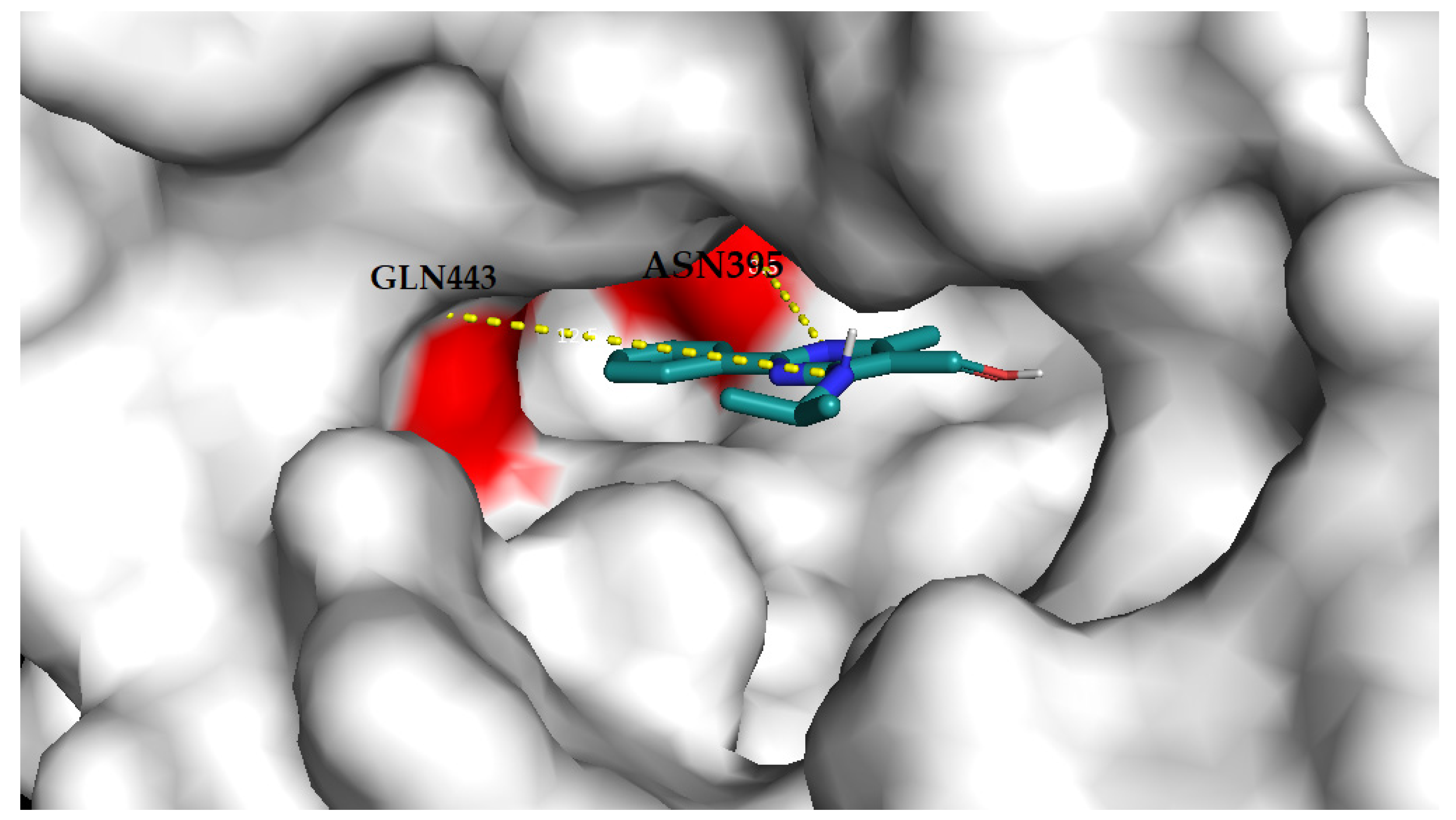

3.4.2. Molecular Docking Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lagoja, I.M. Pyrimidine as constituent of natural biologically active compounds. Chem. Biodivers. 2005, 2, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.; Martines, M.A.U.; Duarte, A.P.; Jorge, J.; Rasool, S.; Muhammad, R.; Ahmad, N.; Umar, M.N. Research developments in the syntheses, anti-inflammatory activities and structure–activity relationships of pyrimidines. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 6060–6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eicher, T.; Hauptmann, S.; Speicher, A. The Chemistry of Heterocycles; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2003; ISBN 978-3-527-30720-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S.; Shen, L.; Dai, Q.; Wu, S.C.; Collins, L.B.; Swenberg, J.A.; He, C.; Zhang, Y. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science 2011, 333, 1300–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branco, M.R.; Ficz, G.; Reik, W. Uncovering the role of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the epigenome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 13, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjelland, S.; Eide, L.; Time, R.W.; Stote, R.; Eftedal, I.; Volden, G.; Seeberg, E. Oxidation of thymine to 5-formyluracil in DNA: Mechanisms of formation, structural implications, and base excision by human cell free extracts. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 14758–14764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, D.-M.; Schmitz, K.-M.; Petersen-Mahrt, S.K. 5-methylcytosine DNA demethylation: More than losing a methyl group. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012, 46, 419–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Bai, F.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Ma, S.-H.; Liu, J.; Xu, Z.-D.; Zhu, H.-G.; Ling, Z.-Q.; Ye, D.; et al. Tumor development is associated with decrease of TET gene expression and 5-methylcytosine hydroxylation. Oncogene 2013, 32, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, H.; Jiang, X.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Song, C.-X.; He, C.; Sun, M.; Chen, P.; Gurbuxani, S.; Wang, J.; et al. TET1 plays an essential oncogenic role in MLL-rearranged leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 11994–11999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tanaka, F.; Takeuchi, S.; Tanaka, N.; Yonehara, H.; Umezawa, H.; Sumiki, Y. Bacimethrin, a new antibiotic produced by B. megatherium. J. Antibiot. 1961, 14, 161–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddick, J.J.; Saha, S.; Melnick, J.S.; Perkins, J.; Begley, T.P. The mechanism of action of bacimethrin, a naturally occurring thiamin antimetabolite. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 2245–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, T.L.V.; Price, C.C. The synthesis of some pyrimidine metabolite analogs1. J. Org. Chem. 1956, 21, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieplik, J.; Stolarczyk, M.; Pluta, J.; Gubrynowicz, O.; Bryndal, I.; Lis, T.; Mikulewicz, M. Synthesis and antibacterial properties of pyrimidine derivatives. Acta Pol. Pharm 2015, 72, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stolarczyk, M.; Bryndal, I.; Matera-Witkiewicz, A.; Lis, T.; Królewska-Golińska, K.; Cieślak, M.; Kaźmierczak-Barańska, J.; Cieplik, J. Synthesis, crystal structure and cytotoxic activity of novel 5-methyl-4-thio pyrimidine derivatives. Acta Crystallogr. C 2018, 74, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goerdeler, J.; Pohland, H.W. Darstellung und cyclisierung von α-acyl-β-amino-thiocrotonamiden. Chem. Ber. 1963, 96, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, A.H.; Assy, M.G.; Amr, E.A.; Saber, R.M. Studies on the chemical reactivity of ethyl 4-sulfanyl-6-methyl-2-phenylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate. Curr. Org. Chem. 2011, 15, 1661–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorokhov, V.A.; Gordeev, M.F.; Komkov, A.V.; Bogdanov, V.S. Synthesis of 4-amino-5-alkoxycarbonyl(acyl)pyrimidines from β-dicarbonyl compounds and n-cyanoamidines. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1990, 39, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlis PRO; Agilent Technologies Ltd.: Yarnton, Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.rigaku.com/products/crystallography/crysalis (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, K. DIAMOND; Crystal Impact GbR: Bonn, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Spek, A.L. Structure validation in chemical crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 2009, 65, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetto, G.; del Peso, A.; Zurita, J.L. Neutral red uptake assay for the estimation of cell viability/cytotoxicity. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silicos-It|Filter-ItTM. Available online: http://silicos-it.be.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/software/filter-it/1.0.2/filter-it.html (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: Updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W357–W364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolinsky, T.J.; Nielsen, J.E.; McCammon, J.A.; Baker, N.A. PDB2PQR: An automated pipeline for the setup of poisson-boltzmann electrostatics calculations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, W665–W667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernstein, J.; Davis, R.E.; Shimoni, L.; Chang, N.-L. Patterns in hydrogen bonding: Functionality and graph set analysis in crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1995, 34, 1555–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, P.; Rohde, B.; Selzer, P. Fast calculation of molecular polar surface area as a sum of fragment-based contributions and its application to the prediction of drug transport properties. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 20, 3714–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannhold, R.; Poda, G.I.; Ostermann, C.; Tetko, I.V. Calculation of molecular lipophilicity: State-of-the-art and comparison of log P methods on more than 96,000 compounds. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 861–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Lin, F.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Lai, L. Computation of octanol-water partition coefficients by guiding an additive model with knowledge. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 2140–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildman, S.; Crippen, G. Prediction of physicochemical parameters by atomic contributions. J. Chem. Inform. Comput. Sci. 1999, 5, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, I.; Hirono, S.; Liu, Q.; Nakagome, I.; Matsushita, Y. Simple Method of calculating octanol/water partition coefficient. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1992, 40, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moriguchi, I.; Hirono, S.; Nakagome, I.; Hirano, H. Comparison of reliability of log p values for drugs calculated by several methods. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1994, 42, 976–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. iLOGP: A simple, robust, and efficient description of n-octanol/water partition coefficient for drug design using the GB/SA approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 3284–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, J.S. ESOL: Estimating aqueous solubility directly from molecular structure. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004, 44, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, J.; Camilleri, P.; Brown, M.; Hutt, A.J.; Kirton, S.B. Revisiting the general solubility equation: In silico prediction of aqueous solubility incorporating the effect of topographical polar surface area. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, R.O.; Guy, R.H. Predicting skin permeability. Pharm. Res. 1992, 9, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, C.R.; Smith, G.; Smith, R.L. Science, medicine, and the future: Pharmacogenetics. BMJ 2000, 320, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, L. The role of drug metabolizing enzymes in clearance. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2014, 10, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Fenney, P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 46, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arup, G.; Viswanadhan, V.N.; Wendoloski, J.J. A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Comb. Chem. 1999, 1, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veber, D.F.; Johnson, S.R.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Smith, B.R.; Ward, K.W.; Kopple, K.D. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates available. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, W.J.; Merz, K.M.J.; Baldwin, J.J. Prediction of drug absorption using multivariate statistics. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3867–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muegge, I.; Heald, S.L.; Brittelli, D. Simple selection criteria for drug-like chemical matter. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 1841–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baell, J.B.; Holloway, G.A. New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2719–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brenk, R.; Schipani, A.; James, D.; Krasowski, A.; Gilbert, I.H.; Frearson, J.; Wyatt, P.G.W. Lessons learnt from assembling screening libraries for drug discovery for neglected diseases. ChemMedChem 2008, 3, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Willet, P.; Glen, R.C.; Leach, A.R.; Taylor, R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stolarczyk, M.; Wolska, A.; Mikołajczyk, A.; Bryndal, I.; Cieplik, J.; Lis, T.; Matera-Witkiewicz, A. A new pyrimidine schiff base with selective activities against enterococcus faecalis and gastric adenocarcinoma. Molecules 2021, 26, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compounds | D–H···A | D–H | H···A | D···A | D–H···A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3c | O1–H1···N1 i | 0.84 | 2.01 | 2.825 (2) | 162 |

| N4–H41···N3 ii | 0.88 | 2.31 | 3.151 (2) | 159 | |

| N4–H42···O1 | 0.88 | 2.29 | 2.834 (2) | 120 | |

| 3e | O1–H1···N1 i | 0.84 | 2.13 | 2.9525 (14) | 165 |

| N4–H4···O1 ii | 0.88 | 2.48 | 3.1361 (14) | 132 | |

| N4–H4···O1 | 0.88 | 2.41 | 3.0116 (13) | 126 | |

| 3f | O1–H1···N1 i | 0.84 | 2.09 | 2.9199 (16) | 172 |

| N4–H4···O1 ii | 0.88 | 2.13 | 2.9434 (16) | 154 | |

| 3g | O1–H1···N1 i | 0.84 | 2.08 | 2.9009 (12) | 164 |

| N4–H4···O1 ii | 0.88 | 2.50 | 3.3210 (13) | 155 | |

| N4–H4···O1 | 0.88 | 2.55 | 3.0577 (14) | 118 | |

| C43–H431···O1 ii | 0.98 | 2.62 | 3.4038 (16) | 138 | |

| 3h | O1A–H1A···N1A i | 0.84 | 1.97 | 2.772 (5) | 159 |

| N4A–H4A···O1A | 0.88 | 2.18 | 2.767 (5) | 124 | |

| O1B–H1B···N1C ii | 0.84 | 2.01 | 2.78 (2) | 152 | |

| N4B–H4B···O1B | 0.88 | 2.21 | 2.773 (16) | 122 | |

| O1C–H1C···N1B ii | 0.84 | 1.95 | 2.77 (2) | 163 | |

| N4C–H4C···O1C | 0.88 | 2.20 | 2.78 (3) | 123 |

| HeLa | HepaRG | Caco-2 | AGS | A172 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | >250 µM | 200.8 µM | >250 µM | 209.2 µM | >250 µM |

| 3c | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM |

| 3d | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM |

| 3e | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM |

| 3f | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM |

| 3g | 209.4 µM | 183.3 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | 146.7 µM |

| 3h | >250 µM | 132.3 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM |

| 3i | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM | >250 µM |

| Staurosporine | 1 µM | 1 µM | 1 µM | 1 µM | 1 µM |

| 3a | 3c | 3d | 3e | 3f | 3g | 3h | 3i | Standard Agent (µg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. baumannii | - | - | - | 256 | - | 256 | 256 | - | Levofloxacin: 0.5 |

| P. aeruginosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Levofloxacin: 1 |

| E. coli | - | - | - | - | 128 | - | - | Gentamicin: 2 | |

| E. faecalis | - | - | - | 256 | - | - | - | - | Levofloxacin: 4 |

| K. pneumoniae | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Gentamicin: 2 |

| MRSA | - | - | - | - | 256 | - | - | - | Levofloxacin: 1 |

| C. albicans | 256 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Amphotericin B: 1 |

| 3a | 3g | 3h | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiochemical properties | The compound has a molecular weight of 308.40 g/mol; number of heavy atoms and number of aromatic heavy atoms: 22 and 11, respectively; number of rotatable bonds: 4; number of H-bond acceptors and donors: 3 and 1, respectively. The value of the polar surface area (PSA) calculated using the topological polar surface area (TPSA), considering sulfur and phosphorus as polar atoms, is 71.32 Å2 [31]. | The compound has a molecular weight of 257.33 g/mol; number of heavy atoms and number of aromatic heavy atoms: 19 and 12, respectively; number of rotatable bonds: 4; number of H-bond acceptors and donors: 3 and 2, respectively. The value of the polar surface area (PSA) calculated using the topological polar surface area (TPSA), considering sulfur and phosphorus as polar atoms, is 58.04 Å. | The compound has a molecular weight of 271.36 g/mol; number of heavy atoms and number of aromatic heavy atoms: 20 and 12, respectively; number of rotatable bonds: 4; number of H-bond acceptors and donors: 3 and 2, respectively. The value of the polar surface area (PSA) calculated using the topological polar surface area (TPSA), considering sulfur and phosphorus as polar atoms, is 58.04 Å. |

| Lipophilicity | The value partition coefficient between n-octanol and water (log Po/w) is 3.72 [32]. It is an average value of five freely available predictive models (i.e., XLOGP3 [33], WLOGP [34], MLOGP [35,36], SILICOS-IT [25], and iLOGP) [37]. | The consensus value partition coefficient between n-octanol and water (log Po/w) is 2.68. | The consensus value partition coefficient between n-octanol and water (log Po/w) is 2.92. |

| Water solubility | Estimated by three predictors. The value of Log S (ESOL) [38] is −4.47, which makes a compound moderately soluble. The predicted value of solubility is 1.03∙10−2 mg/mL. The value of log S (Ali) [39] is −4.97, which also classifies the compound as moderately soluble. The value of solubility is 3.30 × 10−3 mg/mL. The value of log S (SILICOS-IT) [25] is −7.00, which classifies the compound as poorly soluble. The predicted value of solubility is 3.09 × 10−5 mg/mL. | The value of Log S (ESOL) is −3.56, which classifies a compound as soluble. The predicted value of solubility is 7.08 × 10−2 mg/mL. The value of log S (Ali) is −3.94, which also classifies the compound as soluble. The value of solubility is 2.99 × 10−2 mg/mL. The value of log S (SILICOS-IT) is −5.26, which classifies the compound as moderately soluble. The predicted value of solubility is 1.40 × 10−3 mg/mL. | The value of Log S (ESOL) is −3.74, which classifies a compound as soluble. The predicted value of solubility is 4.97 × 10–2 mg/mL. The value of log S (Ali) is −4.12, which classifies the compound as moderately soluble. The predicted value of solubility is 2.05 × 10–2 mg/mL. The value of log S (SILICOS-IT) is −5.65, which also classifies the compound as moderately soluble. The predicted value of solubility is 6.09 × 10–4 mg/mL. |

| Pharmacokinetics | One of the estimated predictors relates to skin permeability coefficient (Kp) [40]. The more negative Kp is, the less permeant a molecule is. The predicted Kp value of compound 3a is −5.50 cm/s, the predicted interaction of a molecule with cytochromes P450 [41,42]. The inhibition of five isoforms, CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4, may cause pharmacokinetics-related drug–drug interactions. Compound 3a is predicted to be an inhibitor of all of the five enzyme isoforms. | The predicted Kp value of compound 3g is −5.70 cm/s. Compound 3g is predicted to be an inhibitor of CYP1A2 and CYP2D6. | The predicted Kp value of compound 3h is −5.66 cm/s. Compound 3g is predicted to be an inhibitor of CYP1A2 and CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. |

| Druglikeness | Estimation of the chance to be an oral drug. The Swiss ADME software bases on five different predictors. Originally used by major pharmaceutical companies aiming to improve the quality of their chemical substances. The Lipinski (Pfizer) rule of five [43], Ghose (Amgen) [44], Veber (GSK) [45], Egan (Pharmacia) [46], and Muegge (Bayer) [47]. According to all of the predictors, compound 3a is predicted to have a chance to be an oral drug. | According to all of the five predictors, compound 3g is predicted to have a chance to be an oral drug. | According to all of the five predictors, compound 3h is predicted to have a chance to be an oral drug. |

| Medicinal chemistry | Two complementary pattern recognition methods allow for the identification of potentially problematic fragments—assay interference compounds (PAINS) [48] and Brenk Structural alert [49]. Zero predicted alerts assist in creating a good druglike molecule. | Compound 3g has zero predicted structural problematic fragments. | Compound 3h has zero predicted structural problematic fragments. |

| Compound | Target Class | Target Name | Protein Data Bank (PDB) Accession Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | Phosphodiesterase | Phosphodiesterase 10A | 5B4L |

| Oxidoreductase | Cyclooxygenase-1 | 6Y3C | |

| 3g | Phosphodiesterase | Phosphodiesterase 4B | 1ROR |

| Family A G protein-coupled receptor | Adenosine A1 receptor | 5UEN | |

| 3h | Family A G protein-coupled receptor | Adenosine A1 receptor | 5UEN |

| Family A G protein-coupled receptor | Adenosine A2a receptor | 5IU4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stolarczyk, M.; Matera-Witkiewicz, A.; Wolska, A.; Krupińska, M.; Mikołajczyk, A.; Pyra, A.; Bryndal, I. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Biological Evaluation of Novel 5-Hydroxymethylpyrimidines. Materials 2021, 14, 6916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14226916

Stolarczyk M, Matera-Witkiewicz A, Wolska A, Krupińska M, Mikołajczyk A, Pyra A, Bryndal I. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Biological Evaluation of Novel 5-Hydroxymethylpyrimidines. Materials. 2021; 14(22):6916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14226916

Chicago/Turabian StyleStolarczyk, Marcin, Agnieszka Matera-Witkiewicz, Aleksandra Wolska, Magdalena Krupińska, Aleksandra Mikołajczyk, Anna Pyra, and Iwona Bryndal. 2021. "Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Biological Evaluation of Novel 5-Hydroxymethylpyrimidines" Materials 14, no. 22: 6916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14226916

APA StyleStolarczyk, M., Matera-Witkiewicz, A., Wolska, A., Krupińska, M., Mikołajczyk, A., Pyra, A., & Bryndal, I. (2021). Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Biological Evaluation of Novel 5-Hydroxymethylpyrimidines. Materials, 14(22), 6916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14226916