New Zn3Mg-xY Alloys: Characteristics, Microstructural Evolution and Corrosion Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Corrosion Behavior Analysis

2.3. Microhardness Investigation

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results of the Samples

3.2. Immersion Tests

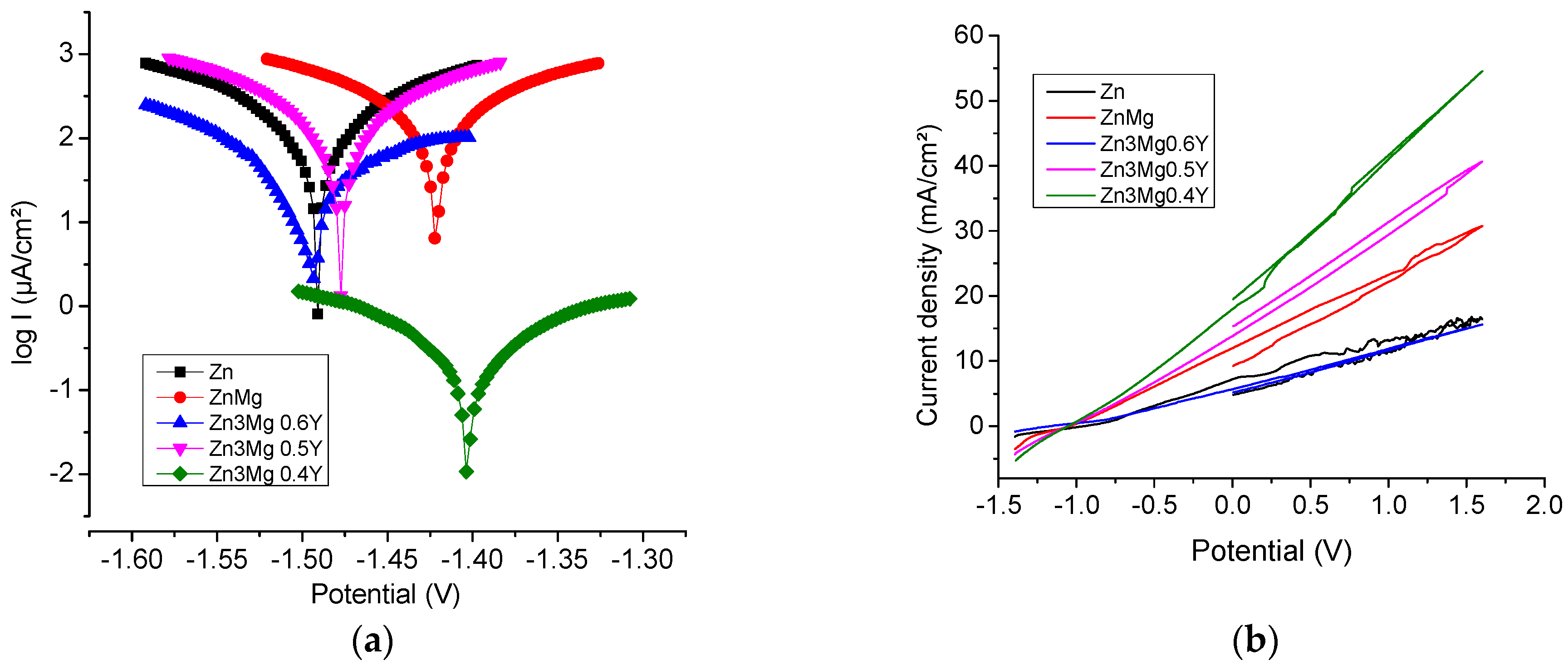

3.3. Potentiodynamic Polarization Curves

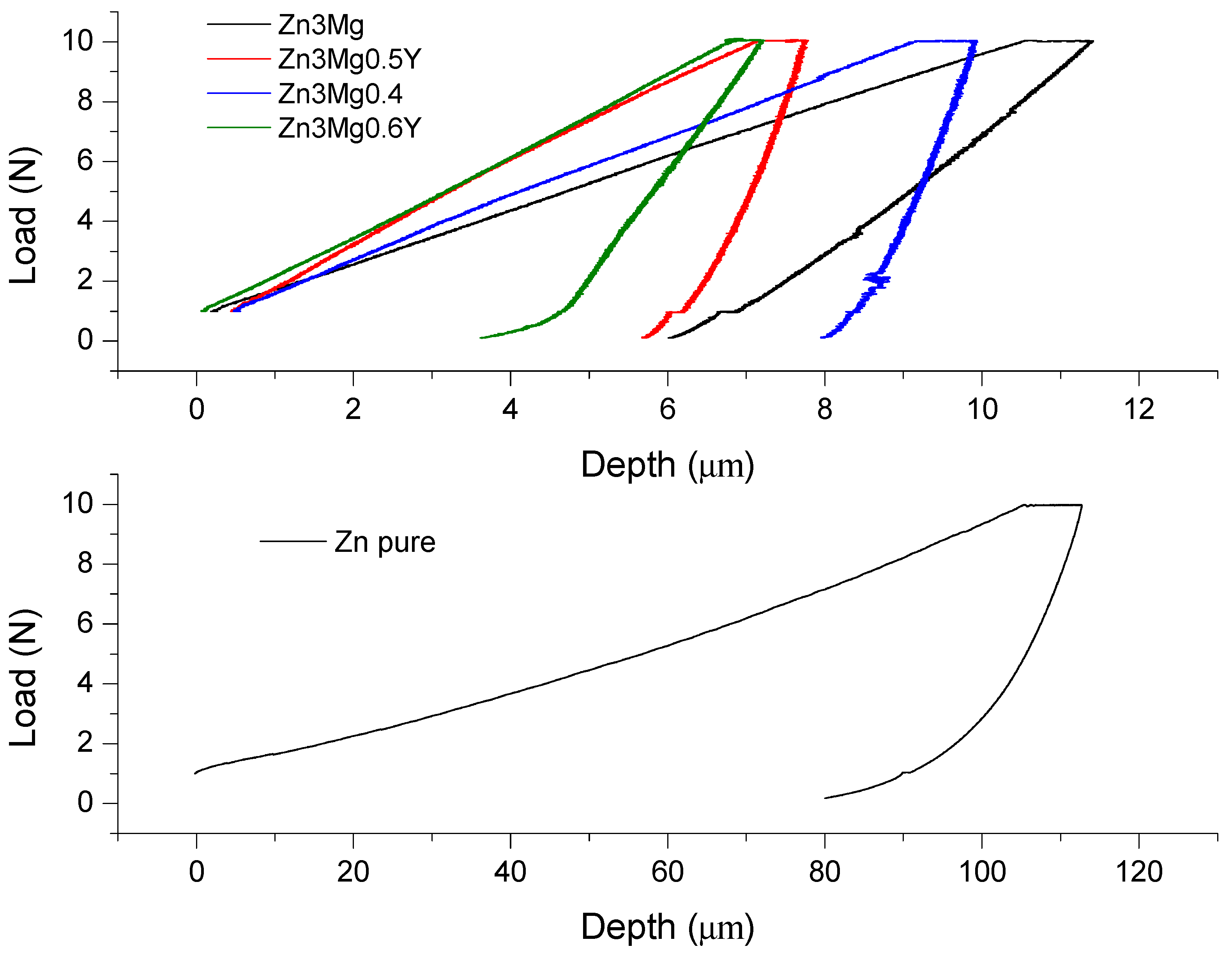

3.4. Micro-Hardness Characterization of the Samples

4. Conclusions

- The Mg and Y addition to pure Zn improves mechanical properties as microhardness, Young’s modulus, and contact stiffness.

- The appearance of YZn12 and Mg12ZnY intermetallic phases among ZnMg compounds has the most significant importance concerning the modification of Zn properties.

- The growth of the Zn3PO4 layer on the surface alloys provides protective corrosion resistance effect.

- Y participation in formation of YZn12 intermetallic phase elements gives the new alloy a more noble potential than pure Zinc.

- Formation of YZn12 intermetallic compound has been correlated with a more aggressive galvanic corrosion between Mg2Zn11 and YZn12 with the Zn matrix.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Witte, F. The history of biodegradable magnesium implants: A review. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1680–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Gu, X.N.; Witte, F. Biodegradable metals. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2014, 77, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, H. Biodegradable Metals from Concept to Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, J.M.; Durisin, M.; Goldman, J.; Drelich, J.W. Recent advances in biodegradable metals for medical sutures: A critical review. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015, 4, 1915–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiden, M.; Walker, E.; Stanciu, L. Magnesium, iron and zinc alloys, the trifecta of bioresorbable orthopaedic and vascular implantation–A review. Biotechnol. J. Biomater. 2015, 5, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zheng, Y.; Qin, L. Progress of biodegradable metals. Proc. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2014, 24, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.H.; Jung, Y.; Kim, S.H. Current status and future direction of biodegradable metallic and polymeric vascular scaffolds for next-generation stents. Acta Biomater. 2017, 60, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, H. Updates on the research and development of absorbable metals for biomedical applications. Prog. Biomater. 2018, 7, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, P.K.; Drelich, J.; Goldman, J. Zinc exhibits ideal physiological corrosion behavior for bioabsorbable stents. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 2577–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtech, D.; Kubasek, J.; Serak, J.; Novak, P. Mechanical and corrosion properties of newly developed biodegradable Zn-based alloys for bone fixation. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 3515–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Wu, Y.; Han, J.; Jia, Z.; Lin, W.; Zhang, D.; Li, W.; et al. Evolution of the degradation mechanism of pure zinc stent in the one-year study of rabbit abdominal aorta model. Biomaterials 2017, 145, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghiri, M.A.; Asatourian, A.; Orangi, J.; Sorenson, C.M.; Sheibani, N. Functional role of inorganic trace elements in angiogenesis-Part II: Cr, Si, Zn, Cu, and S. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2015, 96, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purushothaman, M.; Gudrun, R.; Michal, T.; Bernhard, H. Zinc modulates PPARc signaling and activation of porcine endothelial cells. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3058. [Google Scholar]

- Kaji, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yamamoto, C.; Sakamoto, M.; Kozuka, H. Stimulation by zinc of cultured vascular endothelial cell proliferation: Possible involvement of endogenous basic fibroblast growth factor. Life Sci. 1994, 55, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, P.J.; Bhattacharya, R.; Moreyra, A.E.; Korichneva, I.L. Zinc and cardiovascular disease. Nutrition 2010, 26, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, F.; Qiu, K.; Wang, X. Design and characterizations of novel biodegradable ternary Zn-based alloys with IIA nutrient alloying elements Mg, Ca and Sr. Mater. Des. 2015, 83, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Yu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D.; Yin, Y.; Wang, L. Effects of Ag, Cu or Ca addition on microstructure and comprehensive properties of biodegradable Zn-0.8Mn alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 99, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y.; Shi, Z.; Wang, K.; Lin, J.; Li, Y.; Lin, J.; Wen, C. Microstructure, mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and in vitro corrosion and degradation behavior of a new Zn-5Ge alloy for biodegradable implant materials. Acta Biomater. 2018, 82, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venezuela, J.; Dargusch, M.S. The influence of alloying and fabrication techniques on the mechanical properties, biodegradability and biocompatibility of zinc: A comprehensive review. Acta Biomater. 2019, 87, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Shao, X.; Dai, T.; Xu, F.; Zhou, J.G.; Qu, G.; Tian, L.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y. In vivo study of the efficacy, biosafety, and degradation of a zinc alloy osteosynthesis system. Acta Biomater. 2019, 92, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostaed, E.; Sikora-Jasinska, M.; Mostaed, A.; Loffredo, S.; Demir, A.G.; Previtali, B.; Mantovani, D.; Beanland, R.; Vedani, M. Novel Zn-based alloys for biodegradable stent applications: Design, development and in vitro degradation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 60, 581–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhou, J.; Virtanen, S. Fabrication of ZnO nanotube layer on Zn and evaluation of corrosion behavior and bioactivity in view of biodegradable applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 494, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallot, E.; Nedelec, J.M.; Grimault, A.S.; Chassot, E.; Grandjean-Laquerriere, A.; Laquerriere, P.; Laurent-Maquin, D. STEM and EDXS characterisation of physico-chemical reactions at the periphery of sol–gel derived Zn-substituted hydroxyapatites during interactions with biological fluids. Colloid Surface B 2005, 42, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Cockerill, I.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Chang, L.; Zheng, Y. Zinc-based biomaterials for regeneration and therapy. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 37, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torne, K.B. Zn–Mg and Zn–Ag degradation mechanism under biologically relevant conditions. Surf. Innov. 2017, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambe, T.; Tsuji, T.; Hashimoto, A.; Itsumura, N. The physiological, biochemical, and molecular roles of zinc transporters in zinc homeostasis and metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 95, 749–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunan High Broad New Material, Co.Ltd. Available online: http://www.hbnewmaterial.com/supplier-129192-master-alloy (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- Baciu, E.R.; Cimpoesu, R.; Vitalariu, A.; Baciu, C.; Cimpoesu, N.; Sodor, A.; Zegan, G.; Murariu, A. Surface analysis of 3D (SLM) Co-Cr-W dental metallic materials. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, G.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Nash, P.; Pan, Y.Y.; Nash, A. Binary alloy phase diagrams (Ni-Sb; Ni-Sc; Ni-Se; Ni-Si; Ni-Sm; Ni-Sn). In ASM Handbook. Volume 3. Alloys Phase Diagrams; ASM International: Russell Township, OH, USA, 1991; pp. 317–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.-Y.; Liu, L.M.; Wang, S.Q. The microstructure, stability, and elastic properties of 14H long-period stacking-ordered phase in Mg–Zn–Y alloys: A first-principles study. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoi, T.; Suzuki, T.; Kawamura, Y.; Hirohashi, M. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-Zn-Y rolled sheet with a Mg12ZnY phase. Mater. Trans. 2010, 51, 1536–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobner, J.; Kozlov, A.; Fang, X.Y.; Geng, J.; Nie, J.F.; Schmid-Fetzer, R. Phase equilibria and transformations in ternary Mg-rich Mg–Y–Zn alloys. Acta Mater. 2012, 60, 5948–5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.; Varsani, V.; Fan, Z. Thermodynamic modelling of the Y–Zn and Mg–Zn–Y systems. Comput. Coupling Phase Diagr. Thermochem. 2006, 30, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, X.H.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.Y.; Liu, Z.K.; Liu, J.X.; Hui, X.D. High strength Mg-Zn-Y alloys reinforced synergistically by Mg12ZnY phase and Mg3Zn3Y2 particle. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 703, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagihara, K.; Kinoshita, A.; Sugino, Y.; Yamasaki, M.; Kawamura, Y.; Yasuda, H.Y.; Umakoshi, Y. Plastic deformation behavior of Mg89Zn4Y7 extruded alloy composed of long-period stacking ordered phase. Intermetallics 2010, 18, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagihara, K.; Yokotani, N.; Umakoshi, Y. Plastic deformation behavior of Mg12YZn with 18R long-period stacking ordered structure. Intermetallics 2010, 18, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Hu, W.; Li, J.; Le, Q.; Bao, L.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, J. Microstructures, mechanical properties and corrosion behaviors of Mg-Y-Zn-Zr alloys with specific Y./Zn mole ratios. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 624, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egami, M.; Ohnuma, I.; Enoki, M.; Ohtani, H.; Abe, E. Thermodynamic origin of solute-enriched stacking-fault in dilute Mg-ZnY alloys. Mater. Des. 2020, 188, 108452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Lin, F.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Virtanen, S. Corrosion behavior of biodegradable metals in two different simulated physiological solutions: Comparison of Mg, Zn and Fe. Corros. Sci. 2021, 182, 109278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, P.; Guo, H.; Huang, H.H.; Zheng, Y. Comparative studies on degradation behavior of pure zinc in various simulated body fluids. JOM 2019, 71, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagener, V.; Faltz, A.S.; Killian, M.S.; Schmuki, P.; Virtanen, S. Protein interactions with corroding metal surfaces: Comparison of Mg and Fe. Faraday Discuss. 2015, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.N.; Zheng, Y.F.; Chen, L.J. Influence of artificial biological fluid composition on the biocorrosion of potential orthopedic Mg-Ca, AZ31, AZ91 alloys. Biomed. Mater. 2009, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamesh, M.I.; Wu, G.; Zhao, Y.; McKenzie, D.R.; Bilek, M.M.M.; Chu, P.K. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of biodegradable Mg-Y-RE and Mg-Zn-Zr alloys in Ringer’s solution and simulated body fluid. Corros. Sci. 2015, 91, 160–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Hu, T.; Chu, P.K. In vitro studies of biomedical magnesium alloys in a simulated physiological environment: A review. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yua, H.; Xu, J.; Xu, Q.; Cuic, G.; Gu, G. Electrostatic self-assembly of Zn3(PO4)2/GO composite with improved anticorrosive properties of water-borne epoxy coating. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 119, 108015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Zhai, S.; Liu, Z.; Teng, F. Effect of coordination interaction between water and zinc on photochemistry property of Zn3(PO4)2·2H2O. Chem. Phys. 2020, 536, 110811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastiukas, G.; Zhou, X.; Asce, M.; Neyazi, B.; Wan, K.T. Sustainable calcination of magnesium hydroxide for magnesium oxychloride cement production. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2019, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Wang, Z.; Tay, S.L.; Zhu, T.; Gao, W. Effects of Mg on microstructure and corrosion properties of Zn–Mg alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 602, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.; Brito, C.; Bertelli, F.; Rocha, O.L.; Garcia, A. Interconnection of thermal parameters, microstructure, macrosegregation and microhardness of unidirectionally solidified Zn-rich Zn–Ag peritectic alloys. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements/Analysis Points | Zn | Mg | Y | |||

| wt% | at% | wt% | at% | wt% | at% | ||

| x1 | 89.11 | 91.76 | – | – | 10.88 | 8.24 | |

| x2 | 99.2 | 98.4 | 0.52 | 1.4 | 0.28 | 0.2 | |

| x3 | 96.28 | 92.16 | 2.79 | 7.19 | 0.93 | 0.65 | |

| x4 | 99.12 | 99.19 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.8 | 0.59 | |

| x5 | 99.43 | 98.48 | 0.57 | 1.52 | – | – | |

| EDS err. | 2.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | ||||

| Materials/Elements | Zn | Mg | Y | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt% | at% | wt% | at% | wt% | at% | |

| Zn pure | 99.99 | 99.99 | − | − | − | − |

| Zn3Mg | 97.02 | 92.63 | 2.98 | 7.37 | − | − |

| Zn3Mg0.4Y | 96.8 | 92.90 | 2.78 | 6.74 | 0.42 | 0.26 |

| Zn3Mg0.5Y | 96.75 | 92.96 | 2.75 | 6.59 | 0.50 | 0.35 |

| Zn3Mg0.6Y | 96.55 | 86.93 | 2.82 | 5.74 | 0.63 | 0.42 |

| EDS error | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | |||

| Samples | Initial Weight [g] | Weight After Immersion [g](mg) | Weight After Ultrasound Cleaning [g](mg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn | 24H | 4.1888 | 4.1906 (+1.8) | 4.1902 (+1.4/−0.4) |

| 48H | 3.9416 | 3.9431 (+1.5) | 3.9428 (+1.2/−0.3) | |

| 72H | 4.1369 | 4.1391 (+2.2) | 4.1387 (+1.8/−0.4) | |

| ZnMg | 24H | 2.6388 | 2.6410 (+2.2) | 2.6401 (+1.3/−0.9) |

| 48H | 3.4378 | 3.4394 (+1.6) | 3.4386 (+0.8/−0.8) | |

| 72H | 2.4310 | 2.4328 (+1.8) | 2.4326 (+1.6/−0.2) | |

| Zn3Mg0.4Y | 24H | 2.2969 | 2.2981 (+1.2) | 2.2979 (+1.0/−0.2) |

| 48H | 2.9427 | 2.9437 (+1.0) | 2.9434 (+0.7/−0.3) | |

| 72H | 1.9240 | 1.9266 (+2.6) | 1.9258 (+1.8/−0.8) | |

| Zn3Mg0.5Y | 24H | 2.4688 | 2.4755 (+6.7) | 2.4753 (+6.5/−0.2) |

| 48H | 2.5858 | 2.5870 (+1.2) | 2.5869 (+1.1/−0.1) | |

| 72H | 2.2160 | 2.2174 (+1.4) | 2.2167 (+0.7/−0.7) | |

| Zn3Mg0.6Y | 24H | 2.2581 | 2.2605 (+2.4) | 2.2604 (+2.3/−0.1) |

| 48H | 2.2529 | 2.2548 (+1.9) | 2.2547 (+1.8/−0.1) | |

| 72H | 2.1964 | 2.1981 (+1.7) | 2.1976 (+1.2/−0.5) | |

| Material | Zn | Mg | Y | O | P | Cl | K | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt% | at% | wt% | at% | wt% | at% | wt% | at% | wt% | at% | wt% | at% | wt% | at% | |

| Zn pure | 55.42 | 26.97 | – | – | – | – | 28.76 | 57.17 | 12.88 | 13.23 | 02.93 | 02.63 | – | – |

| Zn3Mg | 51.60 | 24.26 | 1.09 | 1.38 | – | – | 29.91 | 57.45 | 15.66 | 15.54 | – | – | 1.74 | 1.37 |

| Zn3Mg0.4Y | 51.29 | 23.96 | 0.67 | 0.85 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 30.65 | 58.51 | 15.70 | 15.48 | – | – | 1.44 | 1.12 |

| Zn3Mg0.5Y | 51.54 | 24.25 | 0.92 | 1.16 | 0.64 | 0.22 | 30.18 | 58.03 | 15.43 | 15.32 | – | – | 1.29 | 1.01 |

| Zn3Mg0.6Y | 53.25 | 26.80 | 0.55 | 0.74 | 01.36 | 00.50 | 25.05 | 51.50 | 17.26 | 18.33 | – | – | 2.53 | 2.13 |

| EDS error | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.75 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |||||||

| Sample | −Ecor mV | ba mV | bc mV | Rp ohm.cm2 | Jcorr µA/cm2 | Vcorr mm/Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn | 1491.4 | 122.2 | −141.1 | 168.97 | 210.09 | 3.36 |

| Zn3Mg | 1469.8 | 106.0 | −132.0 | 167.01 | 253.8 | 2.85 |

| Zn3Mg0.4Y | 1402.3 | 134.5 | −135.6 | 78.25 | 575.7 | 6.46 |

| Zn3Mg0.5Y | 1477.9 | 117.9 | −129.1 | 146.06 | 311.6 | 3.49 |

| Zn3Mg0.6Y | 1497.0 | 133.9 | −95.8 | 851.46 | 66.55 | 0.74 |

| Alloys | Indentation Young Modulus (GPa) | Hardness (GPa) | Contact Stiffness (N/µm) | Maximum Load (N) | Maximum Displacement (µm) | Contact Depth (µm) | Contact Area (µm2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn pure | Average | 2.51 | 0.14 | 0.79 | 8.96 | 65.48 | 57.29 | 7,8807.47 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.51 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 26.59 | 26.86 | 5,3656.28 | |

| Zn3Mg | Average | 17.10 | 1.01 | 1.95 | 9.01 | 10.80 | 7.31 | 9022.66 |

| Std. Dev. | 1.73 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 599.36 | |

| Zn3Mg0.4Y | Average | 59.64 | 0.79 | 7.23 | 8.79 | 9.91 | 8.95 | 1,1002.22 |

| Std. Dev. | 12.95 | 0.04 | 1.47 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 507.04 | |

| Zn3Mg0.5Y | Average | 81.37 | 1.22 | 7.94 | 9.01 | 6.88 | 6.03 | 7459.77 |

| Std. Dev. | 10.01 | 0.16 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 841.89 | |

| Zn3Mg0.6Y | Average | 39.26 | 1.25 | 3.77 | 9.02 | 7.51 | 5.70 | 7062.93 |

| Std. Dev. | 1.34 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 430.67 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panaghie, C.; Cimpoeșu, R.; Istrate, B.; Cimpoeșu, N.; Bernevig, M.-A.; Zegan, G.; Roman, A.-M.; Chelariu, R.; Sodor, A. New Zn3Mg-xY Alloys: Characteristics, Microstructural Evolution and Corrosion Behavior. Materials 2021, 14, 2505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14102505

Panaghie C, Cimpoeșu R, Istrate B, Cimpoeșu N, Bernevig M-A, Zegan G, Roman A-M, Chelariu R, Sodor A. New Zn3Mg-xY Alloys: Characteristics, Microstructural Evolution and Corrosion Behavior. Materials. 2021; 14(10):2505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14102505

Chicago/Turabian StylePanaghie, Catalin, Ramona Cimpoeșu, Bogdan Istrate, Nicanor Cimpoeșu, Mihai-Adrian Bernevig, Georgeta Zegan, Ana-Maria Roman, Romeu Chelariu, and Alina Sodor. 2021. "New Zn3Mg-xY Alloys: Characteristics, Microstructural Evolution and Corrosion Behavior" Materials 14, no. 10: 2505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14102505

APA StylePanaghie, C., Cimpoeșu, R., Istrate, B., Cimpoeșu, N., Bernevig, M.-A., Zegan, G., Roman, A.-M., Chelariu, R., & Sodor, A. (2021). New Zn3Mg-xY Alloys: Characteristics, Microstructural Evolution and Corrosion Behavior. Materials, 14(10), 2505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14102505