3-D Cell Culture Systems in Bone Marrow Tissue and Organoid Engineering, and BM Phantoms as In Vitro Models of Hematological Cancer Therapeutics—A Review

Abstract

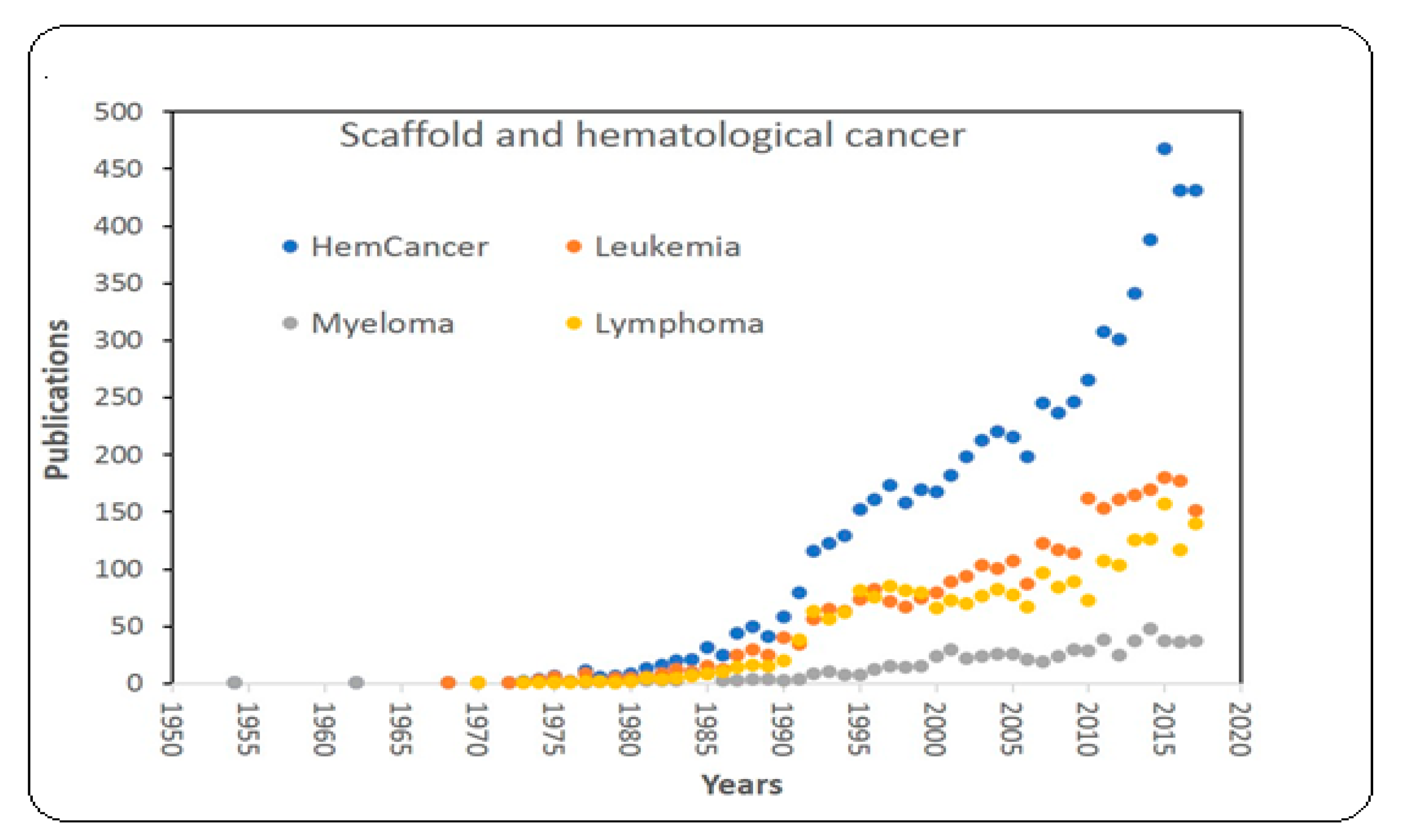

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

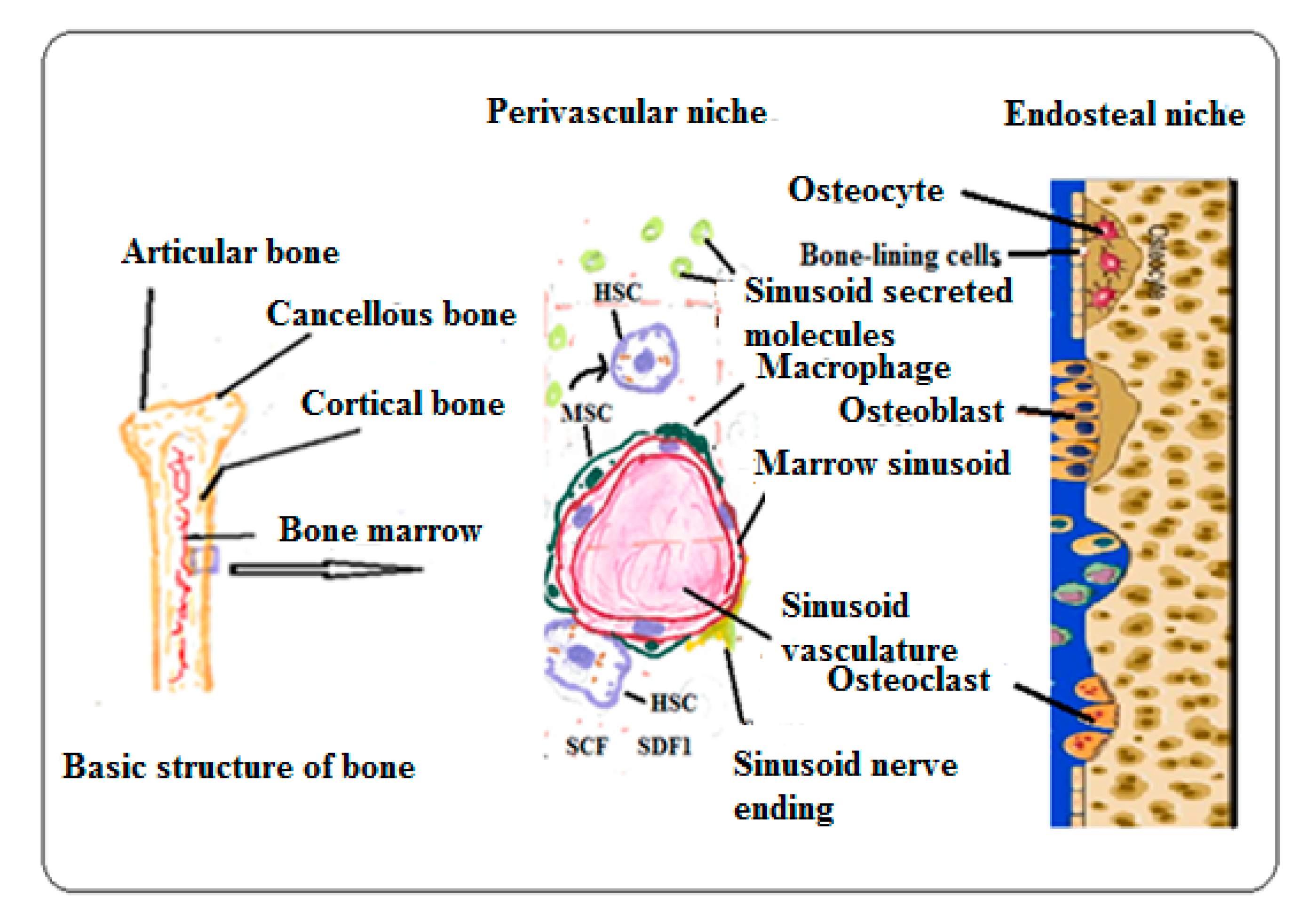

3.1. Bone Marrow Microenvironmental Niches

3.1.1. Interactions of Various Cell Types to Maintain HSC Niches

3.1.2. Therapeutic Radiation and Chemotherapy Damage Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells (HSPC) and Recovery Strategies

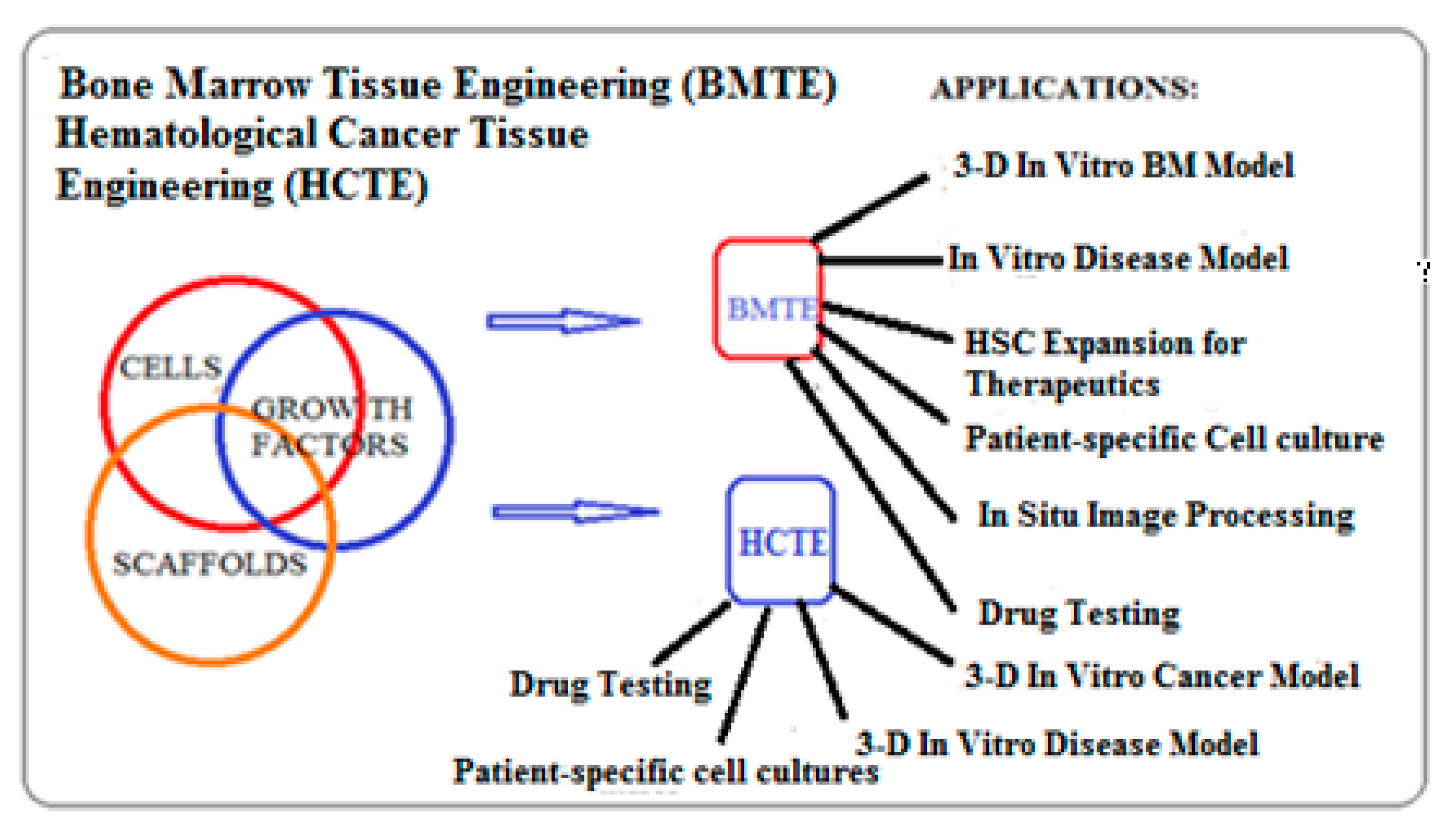

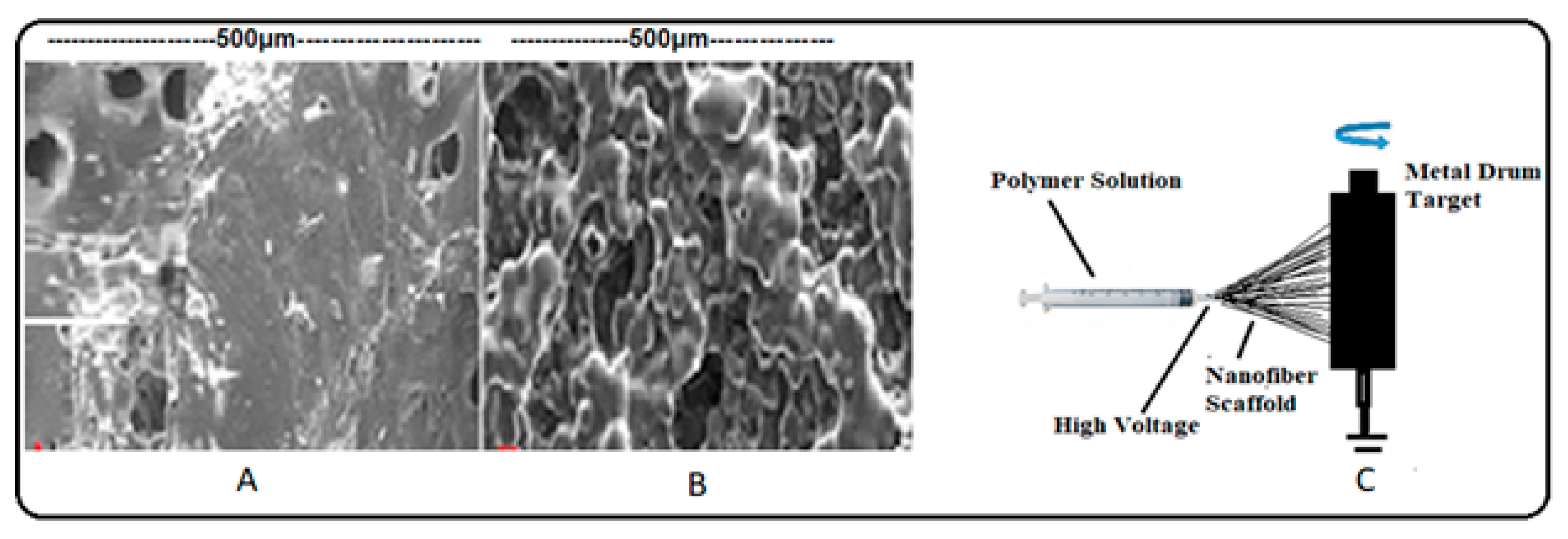

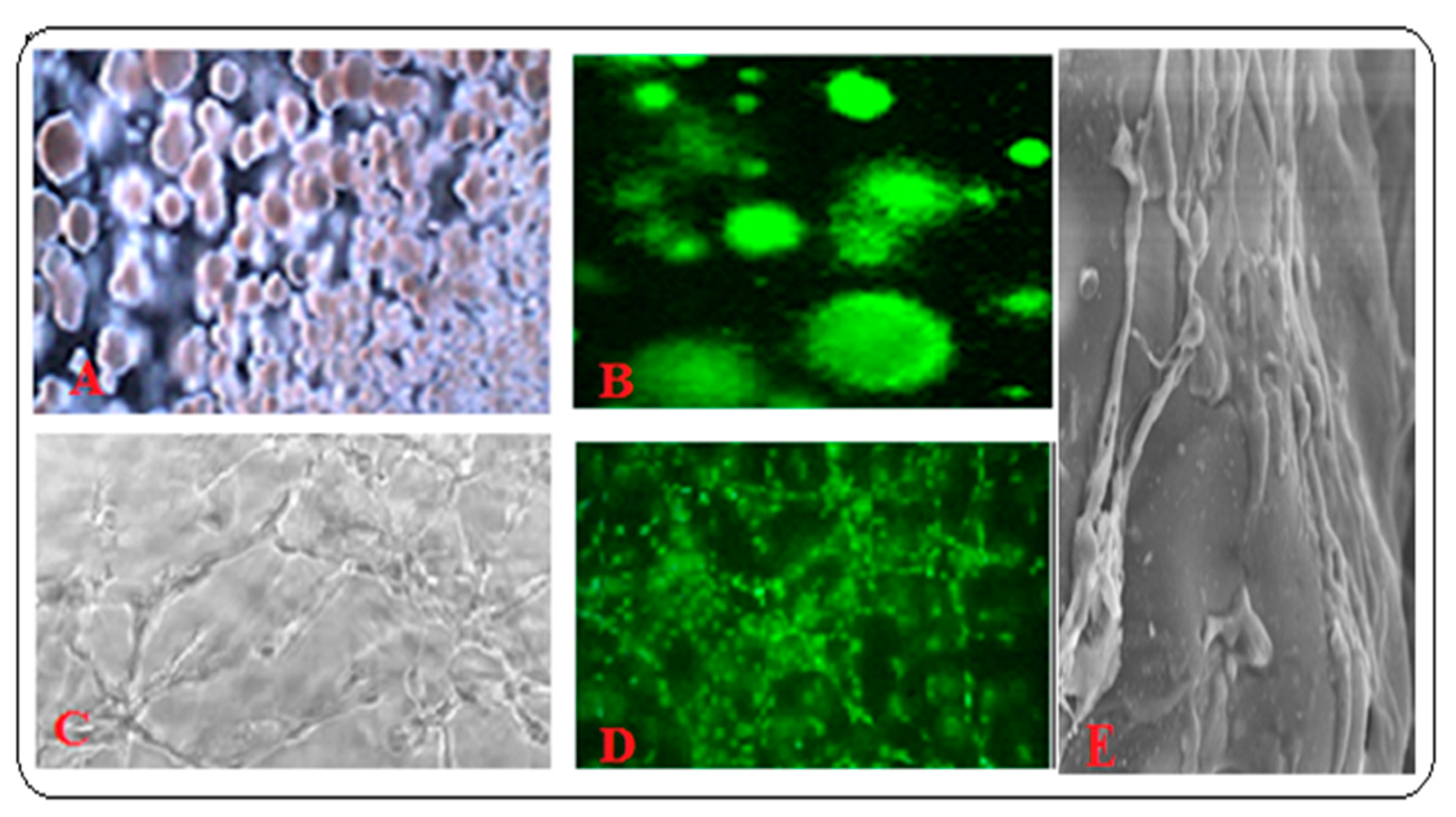

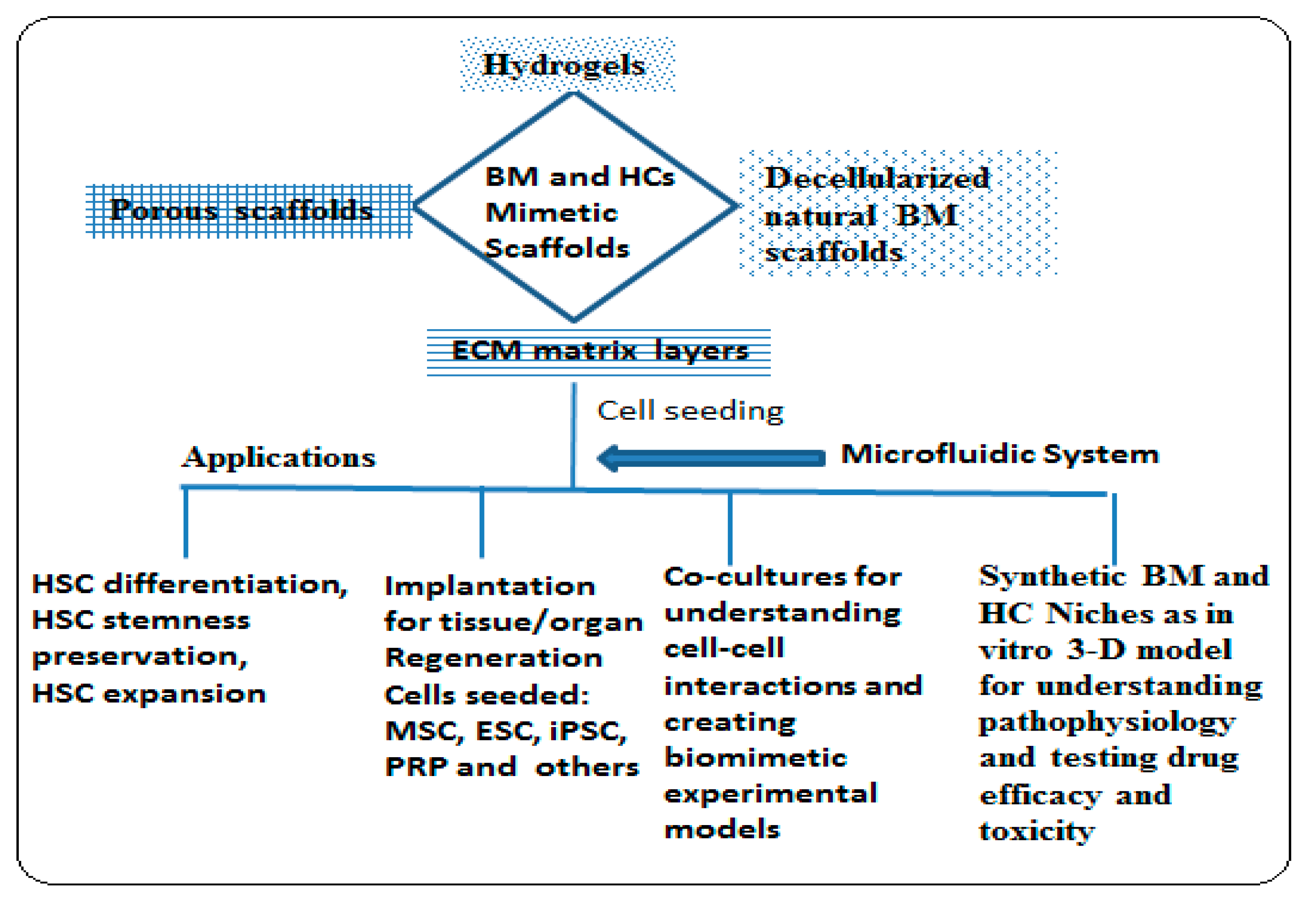

3.2. Biomimetic 3-D Scaffold for Bone Marrow and Hematological Cancer Niches

3.3. Porosity

3.4. Mechanical Sterngth and Stiffness Characterization of Bone Marrow

3.5. Application of Biomimetic Scaffolds in Reconstion of BM and HCs Niches

3.5.1. Co-Cultured Hematopoietic Stem Cells with Other BM Component Systems Modeling the BM Niche Compartments In Vitro with In Vivo Conditions

3.5.2. Biomimetic Scaffold Implantation, Not as a Prosthesis, for Desired BM Tissue Repair and Development

3.5.3. Scaffold for Studying Hematological Cancers

3.5.4. Interaction between Hematological Cancer and Bone Marrow Niche

3.6. Choice of Materials and Advanced Fabrication Technologies for Scaffold Preparation

3.7. Future Perspectives and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALL | Acute lymphoid leukemia | HSPC | Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia | HUVEC | Human umbilical vein endothelial cell |

| BC | Breast cancer | LN | Laminin |

| BLC | Bone lining cells | LTC-IC | long-term culture-initiating cell |

| BM | Bone marrow | MSC | Mesenchymal stem cell |

| BMTE | Bone and marrow tissue engineering | MVs | Microvessels |

| CAR | CXCL12-abundant reticular | NP | Nanoparticle |

| CFU | Colony forming unit | PCL | Polycaprolactone |

| CLL | Chronic lymphoid leukemia | PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| CML | Chronic myeloid leukemia | PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| COL | Collagen | PEGDA | Polyethylene (glycol) Diacrylate |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer | PLA | Poly-L-lactic acid |

| CS | Chitosan | PLAGA | Poly (lactic acid -co-glycolic acid) |

| EBM | Engineered bone marrow | PLGA | Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) copolymer |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix | PRP | Platelet rich plasma |

| ESC | Embryonic stem cell | PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| FN | Fibronectin | ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| GAG | Glycosaminoglycan | SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| HA | Hydroxyapatite | SCF | Stem cell factor |

| HCs | Hematological cancers | SDF1 | Stromal derived factor 1 |

| HCTE | Hematological cancer tissue engineering | TCPS | Tissue culture polystyrene |

| hiPSC | Human induced pluripotent stem cell | TE | Tissue engineering |

| HPC | Hematopoietic progenitor cell | TEB | Tissue engineered bone |

| HSC | Hematopoietic stem cell |

References

- Day, C.P.; Carter, J.; Bonomi, C.; Hollingshead, M.; Merlino, G. Preclinical therapeutic response of residual metastatic disease is distinct from its primary tumor of origin. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voskoglou-Nomikos, T.; Pater, J.L.; Seymour, L. Clinical predictive value of the in vitro cell line, human xenograft, and mouse allograft preclinical cancer models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 4227–4239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asghar., W.; El Assal, R.; Shafiee, H.; Pitteri, S.; Paulmurugan, R.; Demirci, U. Engineering cancer microenvironments for in vitro 3-D tumor models. Mater. Today 2015, 18, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamba, L.; Harrison, M.; Lien, C.-L. Cardiac regeneration in model organisms. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2014, 16, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.V.; Ng, N.C.Y.; Yu, Z.Y.; Casco-Robles, M.M.; Maruo, F.; Tsonis, P.A.; Chiba, C. A developmentally regulated switch from stem cells to dedifferentiation for limb muscle regeneration in newts. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadsetan, M.; Hefferan, T.E.; Szatkowski, J.P.; Mishra, P.K.; Macura, S.I.; Lu, L.; Yaszemski, M.J. Effect of hydrogel porosity on marrow stromal cell phenotypic expression. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2193–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musey, P.I. Dasharatham Janagama and Niranjan K Talukdar. Immunodetection of vascular cells cultured on porus biodegradable scaffolds. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Med. Med. Sci. 2005, 5, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rho, J.-Y.; Kuhn-Spearing, L.; Zioupos, P. Mechanical properties and the hierarchical structure of bone. Med. Eng. Phys. 1998, 20, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, X.; Yeung, K.W.; Liu, C.; Yang, X. Biomimetic porous scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2014, 80, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benders, K.E.; van Weeren, P.R.; Badylak, S.F.; Saris, D.B.; Dhert, W.J.; Malda, J. Extracellular matrix scaffolds for cartilage and bone regeneration. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekaran, A.; Garcia, A.J. Extracellular matrix-mimetic adhesive biomaterials for bone repair. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2011, 96, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, M.; Nör, J.E. The perivascular niche and self-renewal of stem cells. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-García, M.; Yañez, R.M.; Sánchez-Domínguez, R.; Hernando-Rodriguez, M.; Peces-Barba, M.; Herrera, G.; O’Connor, J.E.; Segovia, J.C.; Bueren, J.A.; Lamana, M.L. Mesenchymal stromal cells enhance the engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells in an autologous mouse transplantation model. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, M. The impact of mesenchymal stem cells on differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2015, 5, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulai, P.E.; Frenette, P.S. Making sense of hematopoietic stem cell niches. Blood 2015, 125, 2621–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, I.G.; Sims, N.A.; Pettit, A.R.; Barbier, V.; Nowlan, B.; Helwani, F.; Poulton, I.J.; van Rooijen, N.; Alexander, K.A.; Raggatt, L.J.; et al. Bone marrow macrophages maintain hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niches and their depletion mobilizes HSCs. Blood 2010, 116, 4815–4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, A.; Lucas, D.; Hidalgo, A.; Méndez-Ferrer, S.; Hashimoto, D.; Scheiermann, C.; Battista, M.; Leboeuf, M.; Prophete, C.; van Rooijen, N. Bone marrow CD169+ macrophages promote the retention of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the mesenchymal stem cell niche. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M.Z.; Suszynska, M. Emerging strategies to enhance homing and engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2016, 12, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysoczynski, M.; Reca, R.; Ratajczak, J.; Kucia, M.; Shirvaikar, N.; Honczarenko, M.; Mills, M.; Wanzeck, J.; Janowska-Wieczorek, A.; Ratajczak, M.Z. Incorporation of CXCR4 into membrane lipid rafts primes homing-related responses of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells to an SDF-1 gradient. Blood 2005, 105, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditadi, A.; Sturgeon, C.M.; Keller, G. A view of human haematopoietic development from the Petri dish. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Stemig, M.E.; Takahashi, Y.; Hui, S.K. Radiation response of mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow and human pluripotent stem cells. J. Radiat. Res. 2014, 56, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.-F.; Lin, C.-T.; Chen, W.-C.; Yang, C.-T.; Chen, C.-C.; Liao, S.-K.; Liu, J.M.; Lu, C.-H.; Lee, K.-D. The sensitivity of human mesenchymal stem cells to ionizing radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006, 66, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolay, N.H.; Perez, R.L.; Saffrich, R.; Huber, P.E. Radio-resistant mesenchymal stem cells: Mechanisms of resistance and potential implications for the clinic. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 19366–19380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay-Ghosh, S. Bone as a collagen-hydroxyapatite composite and its repair. Trends Biomater. Artif. Organs 2008, 22, 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. (Ed.) Bone as a Ceramic Composite Material. In Materials Science Forum; Trans. Tech. Publ.: Kapellweg, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, D.A.; Czernuszka, J.T. Collagen-Hydroxyapatite Composites for Hard Tissue Repair. Eur. Cells Mater. 2006, 11, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, L.L.; Jones, J.R. Biomaterials, Artificial Organs and Tissue Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, Z.; Najeeb, S.; Khurshid, Z.; Verma, V.; Rashid, H.; Glogauer, M. Biodegradable Materials for Bone Repair and Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials 2015, 8, 5744–5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.; Gilabert, U.; Garrido, L.; Rosenbusch, M.; Ozols, A. Functionalization of Hydroxyapatite Scaffolds with ZnO. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2015, 9, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ronen, A.; Semiat, R.; Dosoretz, C. Antibacterial Efficiency of a Composite Spacer Containing Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Procedia Eng. 2012, 44, 581–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugdaohsingh, R. Silicon and bone health. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2007, 11, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Annabi, N.; Nichol, J.W.; Zhong, X.; Ji, C.; Koshy, S.T.; Khademhosseini, A.; Dehghani, F. Controlling the Porosity and Microarchitecture of Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2010, 16, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuboki, Y.; Takita, H.; Kobayashi, D.; Tsuruga, E.; Inoue, M.; Murata, M.; Nagai, N.; Dohi, Y.; Ohgushi, H. BMP-induced osteogenesis on the surface of hydroxyapatite with geometrically feasible and nonfeasible structures: Topology of osteogenesis. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 1998, 39, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgiou, V.; Kaplan, D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5474–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decaris, M.L.; Leach, J.K. Design of Experiments Approach to Engineer Cell-Secreted Matrices for Directing Osteogenic Differentiation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 39, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decaris, M.L.; Binder, B.Y.; Soicher, M.A.; Bhat, A.; Leach, J.K. Cell-Derived Matrix Coatings for Polymeric Scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Part A 2012, 18, 2148–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decaris, M.L.; Mojadedi, A.; Bhat, A.; Leach, J.K. Transferable cell-secreted extracellular matrices enhance osteogenic differentiation. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, F.; Nath, J.; Bartholomew, E. Development and inheritance. Fundam. Anat. Physiol. 2004, 20, 1123. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, A.; Frenette, P.S. Hematopoietic stem cell niche maintenance during homeostasis and regeneration. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitropoulos, A.; Piccinini, E.; Brachat, S.; Braccini, A.; Wendt, D.; Barbero, A.; Jacobi, C.; Martin, I. Expansion of Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells from Fresh Bone Marrow in a 3D Scaffold-Based System under Direct Perfusion. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walenda, T.; Bork, S.; Horn, P.; Wein, F.; Saffrich, R.; Diehlmann, A.; Eckstein, V.; Ho, A.D.; Wagner, W. Co-culture with mesenchymal stromal cells increases proliferation and maintenance of haematopoietic progenitor cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009, 14, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.A.; Davaine, J.-M.; Layrolle, P. Pre-vascularization of bone tissue-engineered constructs. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2013, 4, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itkin, T.; Gur-Cohen, S.; Spencer, J.A.; Schajnovitz, A.; Ramasamy, S.K.; Kusumbe, A.P.; Ledergor, G.; Jung, Y.; Milo, I.; Poulos, M.G.; et al. Distinct bone marrow blood vessels differentially regulate haematopoiesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 532, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, A.F.; Whyte, M.; Genever, P.G. Effects of endothelial cells on human mesenchymal stem cell activity in a three-dimensional in vitro model. Eur. Cells Mater. 2011, 22, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaraj, K.K.; Adams, R.H. Blood vessel formation and function in bone. Development 2016, 143, 2706–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, O.H.; Panicker, L.M.; Lu, Q.; Chae, J.J.; Feldman, R.A.; Elisseeff, J.H. Human iPSC-derived osteoblasts and osteoclasts together promote bone regeneration in 3D biomaterials. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; O’Neill, L.A.J. Metabolic reprogramming in macrophages and dendritic cells in innate immunity. Cell Res. 2015, 25, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, S.; Ema, H.; Karlsson, G.; Yamaguchi, T.; Miyoshi, H.; Shioda, S.; Taketo, M.M.; Karlsson, S.; Iwama, A.; Nakauchi, H. Nonmyelinating Schwann Cells Maintain Hematopoietic Stem Cell Hibernation in the Bone Marrow Niche. Cell 2011, 147, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, D.; Scheiermann, C.; Chow, A.; Kunisaki, Y.; Bruns, I.; Barrick, C.A.; Tessarollo, L.; Frenette, P.S. Chemotherapy-induced bone marrow nerve injury impairs hematopoietic regeneration. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuljapurkar, S.R.; McGuire, T.R.; Brusnahan, S.K.; Jackson, J.D.; Garvin, K.L.; Kessinger, M.A.; Lane, J.T.; Kane, B.J.O.; Sharp, J.G. Changes in human bone marrow fat content associated with changes in hematopoietic stem cell numbers and cytokine levels with aging. J. Anat. 2011, 219, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signer, R.A.; Morrison, S.J. Mechanisms that Regulate Stem Cell Aging and Life Span. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, T.; Takubo, K.; Semenza, G.L. Metabolic Regulation of Hematopoietic Stem Cells in the Hypoxic Niche. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 9, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, S.; Wirth, L.; Cavak, N.; Koenigsmark, M.; Marx, U.; Lauster, R.; Rosowski, M. Bone marrow-on-a-chip: Long-term culture of human haematopoietic stem cells in a three-dimensional microfluidic environment. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2018, 12, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, M.R.; Roy, K. Bone-marrow mimicking biomaterial niches for studying hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 3490–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rödling, L.; Schwedhelm, I.; Kraus, S.; Bieback, K.; Hansmann, J.; Lee-Thedieck, C. 3D models of the hematopoietic stem cell niche under steady-state and active conditions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljitawi, O.S.; Li, D.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ramachandran, K.; Stehno-Bittel, L.; Van Veldhuizen, P.; Lin, T.L.; Kambhampati, S.; Garimella, R. A novel three-dimensional stromal-based model for in vitro chemotherapy sensitivity testing of leukemia cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 2014, 55, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.-H.; Zeng, D.-F.; Wang, X.-Y.; Ma, Y.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Kong, P.-Y. Targeting of the leukemia microenvironment by c(RGDfV) overcomes the resistance to chemotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia in biomimetic polystyrene scaffolds. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 3278–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, L.J.; Binner, M.; Körner, Y.; Von Bonin, M.; Bornhäuser, M.; Werner, C. A three-dimensional ex vivo tri-culture model mimics cell-cell interactions between acute myeloid leukemia and the vascular niche. Haematologica 2017, 102, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, M.R.; Mishima, Y.; Glavey, S.V.; Zhang, Y.; Manier, S.; Lu, Z.N.; Memarzadeh, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sacco, A.; Aljawai, Y.; et al. Investigating osteogenic differentiation in multiple myeloma using a novel 3D bone marrow niche model. Blood 2014, 124, 3250–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whang, K.; Healy, K.E.; Elenz, D.R.; Nam, E.K.; Tsai, D.C.; Thomas, C.H.; Nuber, G.W.; Glorieux, F.H.; Travers, R.; Sprague, S.M. Engineering Bone Regeneration with Bioabsorbable Scaffolds with Novel Microarchitecture. Tissue Eng. 1999, 5, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janagama, D.G.; Basson, M.D.; Bumpers, H.L. Abstract 2026: Targeted delivery of therapeutic NefM1 peptide with single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) suppresses growth of 3-D cultures of breast and colon cancers. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 72, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskar, V.; Marion, N.W.; Mao, J.J.; Gemeinhart, R.A. In VitroEvaluation of Macroporous Hydrogels to Facilitate Stem Cell Infiltration, Growth, and Mineralization. Tissue Eng. Part A 2009, 15, 1695–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palocci, C.; Barbetta, A.; La Grotta, A.; Dentini, M. Porous Biomaterials Obtained Using Supercritical CO2—Water Emulsions. Langmuir 2007, 23, 8243–8251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annabi, N.; Mithieux, S.M.; Boughton, E.A.; Ruys, A.J.; Weiss, A.S.; Dehghani, F. Synthesis of highly porous crosslinked elastin hydrogels and their interaction with fibroblasts in vitro. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 4550–4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Woo, D.G.; Sun, B.K.; Chung, H.-M.; Im, S.J.; Choi, Y.M.; Park, K.; Huh, K.M.; Park, K.-H. In vitro and in vivo test of PEG/PCL-based hydrogel scaffold for cell delivery application. J. Control. Release 2007, 124, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Black, L.; Santacana-Laffitte, G.; Patrick, C.W. Preparation and assessment of glutaraldehyde-crosslinked collagen–chitosan hydrogels for adipose tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2007, 81, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, S.; Tuszynski, M.H. The fabrication and characterization of linearly oriented nerve guidance scaffolds for spinal cord injury. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 5839–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.-H.; Kuo, P.-Y.; Hsieh, H.-J.; Hsien, T.-Y.; Hou, L.-T.; Lai, J.-Y.; Wang, D.-M. Preparation of porous scaffolds by using freeze-extraction and freeze-gelation methods. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.-W.; Tabata, Y.; Ikada, Y. Fabrication of porous gelatin scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, N.; Nair, P.D. Polyvinyl alcohol-poly(caprolactone) Semi IPN scaffold with implication for cartilage tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2008, 84, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasam, A.R.; Samli, A.I.; Hess, L.; Ihnat, M.A.; Madihally, S.V. Blending Chitosan with Polycaprolactone: Porous Scaffolds and Toxicity. Macromol. Biosci. 2007, 7, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarkhan-Hagvall, S.; Schenke-Layland, K.; Dhanasopon, A.P.; Rofail, F.; Smith, H.; Wu, B.M.; Shemin, R.; Beygui, R.E.; MacLellan, W.R. Three-dimensional electrospun ECM-based hybrid scaffolds for cardiovascular tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2907–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Gao, P.-L.; Wang, K.; Wang, J.; Zhong, Y.; Luo, Y. Fibrous scaffolds potentiate the paracrine function of mesenchymal stem cells: A new dimension in cell-material interaction. Biomaterials 2017, 141, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellamkonda, R.V.; Kim, Y.-T.; Kumar, S.; Janagama, D.G. Nanofilament Scaffold for Tissue Regeneration. Google Patents No 8,652,215 B2, 18 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, H.-H.; Lee, K.-R.; Lai, H.-M.; Tsai, C.-C.; Chang, Y.-C. Method of Making Porous Biodegradable Polymers. Google Patents No 6,673,286, 26 February 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, L.E.; Birch, N.P.; Schiffman, J.D.; Crosby, A.J.; Peyton, S.R. Mechanics of intact bone marrow. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 50, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buxboim, A.; Rajagopal, K.; Brown, A.E.; Discher, D.E. How deeply cells feel: Methods for thin gels. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2010, 22, 194116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, T.; Ishii, Y.; Ishikawa, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Sato, M. Experimental and numerical analyses of local mechanical properties measured by atomic force microscopy for sheared endothelial cells. Bio-Med. Mater. Eng. 2002, 12, 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- Engler, A.J.; Richert, L.; Wong, J.Y.; Picart, C.; Discher, D.E. Surface probe measurements of the elasticity of sectioned tissue, thin gels and polyelectrolyte multilayer films: Correlations between substrate stiffness and cell adhesion. Surf. Sci. 2004, 570, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-W.; Buxboim, A.; Spinler, K.R.; Swift, J.; Christian, D.A.; Hunter, C.A.; Léon, C.; Gachet, C.; Dingal, P.D.P.; Ivanovska, I.L.; et al. Contractile Forces Sustain and Polarize Hematopoiesis from Stem and Progenitor Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, A.J.; Sen, S.; Sweeney, H.L.; Discher, D.E. Matrix Elasticity Directs Stem Cell Lineage Specification. Cell 2006, 126, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, J.M.; Stokes, R.; Irvine, E.; Graham, D.; Amro, N.A.; Sanedrin, R.G.; Jamil, H.; Hunt, J.A. Introducing dip pen nanolithography as a tool for controlling stem cell behaviour: Unlocking the potential of the next generation of smart materials in regenerative medicine. Lab Chip 2010, 10, 1662–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.M.; Havenstrite, K.L.; Magnusson, K.E.G.; Sacco, A.; Leonardi, N.A.; Kraft, P.; Nguyen, N.K.; Thrun, S.; Lutolf, M.P.; Blau, H.M. Substrate Elasticity Regulates Skeletal Muscle Stem Cell Self-Renewal in Culture. Science 2010, 329, 1078–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, R.J.; Gadegaard, N.; Tsimbouri, P.M.; Burgess, K.V.; McNamara, L.E.; Tare, R.S.; Murawski, K.; Kingham, E.; Oreffo, R.O.C.; Dalby, M.J. Nanoscale surfaces for the long-term maintenance of mesenchymal stem cell phenotype and multipotency. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Harley, B.A.C. Marrow-inspired matrix cues rapidly affect early fate decisions of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1600455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankevicius, V.; Kunigenas, L.; Stankunas, E.; Kuodyte, K.; Strainiene, E.; Cicenas, J.; Samalavičius, N.E.; Suziedelis, K. The expression of cancer stem cell markers in human colorectal carcinoma cells in a microenvironment dependent manner. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 484, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Xiao, Z.; Meng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Han, J.; Su, G.; Chen, B.; Dai, J. The enhancement of cancer stem cell properties of MCF-7 cells in 3D collagen scaffolds for modeling of cancer and anti-cancer drugs. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Z.; Mikheikin, A.; Krasnoslobodtsev, A.; Lv, Z.; Lyubchenko, Y. Novel polymer linkers for single molecule AFM force spectroscopy. Methods 2013, 60, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jing, D.; Fonseca, A.-V.; Alakel, N.; Fierro, F.A.; Muller, K.; Bornhauser, M.; Ehninger, G.; Corbeil, D.; Ordemann, R. Hematopoietic stem cells in co-culture with mesenchymal stromal cells - modeling the niche compartments in vitro. Haematologica 2010, 95, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Zhu, B.; Wang, X.; Xiao, R.; Wang, C. Three-dimensional co-culture of mesenchymal stromal cells and differentiated osteoblasts on human bio-derived bone scaffolds supports active multi-lineage hematopoiesis in vitro: Functional implication of the biomimetic HSC niche. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 38, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasko, T.; Frobel, J.; Lubberich, R.; Goecke, T.W.; Wagner, W. iPSC-derived mesenchymal stromal cells are less supportive than primary MSCs for co-culture of hematopoietic progenitor cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ludin, A.; Itkin, T.; Gur-Cohen, S.; Mildner, A.; Shezen, E.; Golan, K.; Kollet, O.; Kalinkovich, A.; Porat, Z.; D’Uva, G.; et al. Monocytes-macrophages that express α-smooth muscle actin preserve primitive hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travnickova, J.; Chau, V.T.; Julien, E.; Mateos-Langerak, J.; Gonzalez, C.; Lelievre, E.; Lutfalla, G.; Tavian, M.; Kissa, K. Primitive macrophages control HSPC mobilization and definitive haematopoiesis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, S.; Khademhosseini, A.; Yang, Y. Creation of bony microenvironment with CaP and cell-derived ECM to enhance human bone-marrow MSC behavior and delivery of BMP-2. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 6119–6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, N.; Pham, Q.P.; Sharma, U.; Sikavitsas, V.I.; Jansen, J.A.; Mikos, A.G. In vitro generated extracellular matrix and fluid shear stress synergistically enhance 3D osteoblastic differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 2488–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, A.; Hoch, A.I.; Decaris, M.L.; Leach, J.K. Alginate hydrogels containing cell-interactive beads for bone formation. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 4844–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubikova, J.; Cholujova, D.; Hideshima, T.; Gronesova, P.; Soltysova, A.; Harada, T.; Joo, J.; Kong, S.-Y.; Szalat, R.E.; Richardson, P.G.; et al. A novel 3D mesenchymal stem cell model of the multiple myeloma bone marrow niche: Biologic and clinical applications. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 77326–77341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torisawa, Y.-S.; Spina, C.S.; Mammoto, T.; Mammoto, A.; Weaver, J.C.; Tat, T.; Collins, J.J.; Ingber, D.E. Bone marrow–on–a–chip replicates hematopoietic niche physiology in vitro. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijal, G.; Bathula, C.; Li, W. Application of Synthetic Polymeric Scaffolds in Breast Cancer 3D Tissue Cultures and Animal Tumor Models. Int. J. Biomater. 2017, 2017, 8074890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.-E.; Kim, C.G.; Kim, J.S.; Jin, S.; Yoon, S.; Bae, H.-R.; Kim, J.-H.; Jeong, Y.H. Three-dimensional culture and interaction of cancer cells and dendritic cells in an electrospun nano-submicron hybrid fibrous scaffold. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.J.; Husmann, A.; Hume, R.D.; Watson, C.J.; Cameron, R.E. Development of three-dimensional collagen scaffolds with controlled architecture for cell migration studies using breast cancer cell lines. Biomaterials 2017, 114, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, H.; Suda, T. Cancer stem cells and their niche. Cancer Sci. 2009, 100, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattazzo, F.; Urciuolo, A.; Bonaldo, P. Extracellular matrix: A dynamic microenvironment for stem cell niche. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 2506–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzer, C.; Yang, Y.; Hass, R. Interaction of MSC with tumor cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 2016, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-S.; Carter, B.Z.; Andreeff, M. Bone marrow niche-mediated survival of leukemia stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia: Yin and Yang. Cancer Biol. Med. 2016, 13, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konopleva, M.Y.; Jordan, C.T. Leukemia Stem Cells and Microenvironment: Biology and Therapeutic Targeting. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quail, D.F.; Joyce, J.A. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konopleva, M.; Konoplev, S.; Hu, W.; Zaritskey, A.Y.; Afanasiev, B.V.; Andreeff, M. Stromal cells prevent apoptosis of AML cells by up-regulation of anti-apoptotic proteins. Leukemia 2002, 16, 1713–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreeff, M.; Zeng, Z.; Tabe, Y.; Samudio, I.; Fiegl, M.; Watt, J.; Dietrich, M.; Mcqueen, T.; Frolova, O.; Battula, L. Microenvironment and leukemia: Ying and Yang. Ann. Hematol. 2008, 87, S94–S98. [Google Scholar]

- Tabe, Y.; Konopleva, M.Y. Advances in understanding the leukaemia microenvironment. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 164, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houshmand, M.; Soleimani, M.; Atashi, A.; Saglio, G.; Abdollahi, M.; Zarif, M.N. Mimicking the Acute Myeloid Leukemia Niche for Molecular Study and Drug Screening. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2017, 23, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, T.M.; Mantalaris, A.; Bismarck, A.; Panoskaltsis, N. The development of a three-dimensional scaffold for ex vivo biomimicry of human acute myeloid leukaemia. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 2243–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Koo, B.-K.; Knoblich, J.A. Human organoids: Model systems for human biology and medicine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 2020, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, K.; Kotaki, M.; Ramakrishna, S. Guided bone regeneration membrane made of polycaprolactone/calcium carbonate composite nano-fibers. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 4139–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.A.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, K.-S.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, J.-T.; Kim, S.-Y.; Chang, N.-H.; Park, S.-Y. In Vivo Evaluation of 3D-Printed Polycaprolactone Scaffold Implantation Combined with β-TCP Powder for Alveolar Bone Augmentation in a Beagle Defect Model. Materials 2018, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, L.; Alfonsi, R.; Francescangeli, F.; Signore, M.; De Angelis, M.L.; Addario, A.; Costantini, M.; Flex, E.; Ciolfi, A.; Pizzi, S.; et al. Organoids as a new model for improving regenerative medicine and cancer personalized therapy in renal diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrektsson, T.; Johansson, C. Osteoinduction, osteoconduction and osseointegration. Eur. Spine J. 2001, 10, S96–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaky, S.H.; Cancedda, R. Engineering Craniofacial Structures: Facing the Challenge. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 1077–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Lim, G.J.; Lee, J.-W.; Atala, A.; Yoo, J.J. In vitro evaluation of a poly(lactide-co-glycolide)–collagen composite scaffold for bone regeneration. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3466–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yin, D.; Cheng, W. Manufacture of layered collagen/chitosan-polycaprolactone scaffolds with biomimetic microarchitecture. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 113, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Cai, Y.; Xu, G.; Tong, T.; Zhang, W.; Wang, L.; Ji, J.; Shi, P.; et al. Bi-layer collagen/microporous electrospun nanofiber scaffold improves the osteochondral regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 7236–7247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanungo, B.P.; Gibson, L.J. Density–property relationships in collagen–glycosaminoglycan scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ramay, H.R.; Hauch, K.D.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, M. Chitosan–alginate hybrid scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3919–3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.S.; Daniels, A.U.; Andriano, K.P.; Heller, J. Six bioabsorbable polymers:In vitro acute toxicity of accumulated degradation products. J. Appl. Biomater. 1994, 5, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaz, A.; Vadivelu, R.K.; John, J.S.; Barton, M.; Kamble, H.; Nguyen, N.-T. Three-dimensional printing of biological matters. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2016, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.E.L.; Wheadon, H.; Lewis, N.; Yang, J.; Mullin, M.; Hursthouse, A.; Stirling, D.; Dalby, M.J.; Berry, C.C. A Quiescent, Regeneration-Responsive Tissue Engineered Mesenchymal Stem Cell Bone Marrow Niche Model via Magnetic Levitation. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 8346–8354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumpers, H.L.; Janagama, D.G.; Manne, U.; Basson, M.D.; Katkoori, V. Nanomagnetic levitation three-dimensional cultures of breast and colorectal cancers. J. Surg. Res. 2015, 194, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, T.; D’Amora, U.; Gloria, A.; Tunesi, M.; Sandri, M.; Rodilossi, S.; Albani, D.; Forloni, G.; Giordano, C.; Cigada, A.; et al. Systematic Analysis of Injectable Materials and 3D Rapid Prototyped Magnetic Scaffolds: From CNS Applications to Soft and Hard Tissue Repair/Regeneration. Procedia Eng. 2013, 59, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Selimović, Š.; Gauvin, R.; Bae, H. Organ-On-A-Chip: Development and Clinical Prospects Toward Toxicity Assessment with an Emphasis on Bone Marrow. Drug Saf. 2015, 38, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmal, O.; Seifert, J.; Schäffer, T.E.; Walter, C.B.; Aicher, W.K.; Klein, G. Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Expansion in Contact with Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in a Hanging Drop Model Uncovers Disadvantages of 3D Culture. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 4148093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Embryo-Derived Stem Cells: Of Mice and Men. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001, 17, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.N.; Ingber, D.E. Microfluidic organs-on-chips. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, W.L.; Kaplan, D.L.; Georgakoudi, I. Quantitative biomarkers of stem cell differentiation based on intrinsic two-photon excited fluorescence. J. Biomed. Opt. 2007, 12, 060504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Georgakoudi, I.; Rice, W.L.; Hronik-Tupaj, M.; Kaplan, D.L. Optical Spectroscopy and Imaging for the Noninvasive Evaluation of Engineered Tissues. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2008, 14, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, K.P.; Bellas, E.; Fourligas, N.; Lee, K.; Kaplan, D.L.; Georgakoudi, I. Characterization of metabolic changes associated with the functional development of 3D engineered tissues by non-invasive, dynamic measurement of individual cell redox ratios. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 5341–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, W.L.; Kaplan, D.L.; Georgakoudi, I. Two-Photon Microscopy for Non-Invasive, Quantitative Monitoring of Stem Cell Differentiation. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, A.R.; Laurencin, C.T.; Nukavarapu, S.P. Bone Tissue Engineering: Recent Advances and Challenges. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 40, 363–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reizabal, A.; Brito-Pereira, R.; Fernandes, M.M.; Castro, N.; Correia, V.; Ribeiro, C.; Costa, C.; Perez, L.; Vilas, J.L.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Silk Fibroin magnetoactive nanocomposite films and membranes for dynamic bone tissue engineering strategies. Materialia 2020, 12, 100709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BM Components, Architecture and Environmental Niches | BM and HC Components Functions | Scaffolds Components Mimicking the BM and HC Microenvironment | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bone Bones comprise mainly collagen type I and hydroxyapatite (HA). | Creating synthetic BM and HCs niches to mimic the natural BM and HCs environments using the structural components. | Bones support the body and hold the soft organs. Marrow is a site of hematopoietic stem cells. | Convenient to fabricate artificial BM and cancer mimicking scaffolds for BM and HC studies. | [7,24,25,26] |

| 1a. Mineral component of bone 1a. Calcium component Heterogeneous composite mineral, 70% by weight of bone is a modified form of HA. | HA synthesized wet by direct precipitation of calcium and phosphate ions, and used up to 40% of HA in the scaffold fabrication. PLGA and PCL are ECM like polymers that render mechanical strength. | The hardness and rigidity of bone are due to the crystalline complex of calcium and phosphate, known as hydroxyapatite (HA). | Required amounts can be incorporated to build up structure. | [27,28] |

| 1b. Trace elements Zinc, Silicon, Copper, Fluorine, Manganese, Magnesium, Iron, Boron and others elements are present. | Incorporating these trace elements into tissue engineered bone (TEB) scaffold at the time of fabrication. Doping the scaffolds with silicon, carbonate, and zinc simulate the natural bone environment. | Zinc contributes to tissue remodeling, protein and nucleic acid synthesis, cell proliferation, and remodeling ECM. Silicon is essential for bone, cartilage, organ, and connective tissues. Other elements such as copper, fluorine, manganese, magnesium, iron, and boron influence bone function. | Trace elements needed for the healthy functioning of bone cell viability and survival. | [29,30,31] |

| 1c. Porous architecture Spongy and porous nature of the bone. | Desired pore sizes and pore microarchitecture can be created using appropriate size porogens at the time of scaffold fabrication. | Cell distribution interconnection, diffusion of nutrients and oxygen, especially in the absence of a functional vascular system. | Permeability as a function of porosity. Controlled porosity can be created in the 3-D scaffolds. | [32] |

| 2.Extracellular matrix Collagen constitutes 90% of the matrix proteins, and accounts for 25 to 30% of the dry weight of bone Collagen type 1 is the predominant fraction of collagen, together with other proteins and mucopolysaccharides. | Synthesis of ECM like matrix Collagen type I and other mucopolysaccharides can be added to TEB scaffold at the time of synthesis Chitosan (CS) is another ECM-like material. It is a nontoxic, biocompatible, biodegradable cationic polysaccharide. It can be incorporated to TEB scaffold. Incorporating native or synthetic ECM into 3-D scaffolds. | Collagen with its triple helix tertiary structure and high mineralization imparts high tensile strength and high flexibility to bone. It is essential for tissue morphological organization and physiological function. Chitosan simulates the marrow environment. It also promotes electrostatic interactions with anionic glycos- aminoglycans (GAG) and proteoglycans. Incorporating native or synthetic ECM into 3-D scaffolds. | An important structural protein Chitosan is a natural biopolymer. It is easily available and widely used in tissue engineering. Direct transfer of native physio- logical and biochemical cues. | [33,34,35,36,37] |

| 3. BM cells Osteoblasts, bone lining cells (BLC), osteocytes, osteoclasts, MSC, CAR cells, adipocytes, macrophages, and other cell types. | BM cells are in dynamic state of interactions with various cell types in BM environment. Studying the interactions of these different cell types help in understanding the mechanisms of their influence on HSC behavior. Varying combinations of these bone marrow cells in co-culture systems can be used for culturing in BM TE scaffold. | Osteoblasts involved in mineralization of bone and matrix proteins. Play a role in calcium homeostasis and bone resorption. Bone lining cells (BLC) function as a barrier for certain ions and induced osteogenic cells. | BM cellular functional interactions. HSC maintenance. | [16,38,39] |

| 4. Interaction of BM cellular components | Co-cultures in 3-D with MSC increased proliferation and maintained HSC. | To maintain the microenvironment of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell function. | Simulate the in vivo condition in vitro cultures. | [40,41] |

| 5.Blood vessels-forming cells Interactions of multiple cell types in BM to form blood vessels. | HUVEC and MSC in perivascular niches self-assemble and form organized structures. | Blood vessel formation provides niches for hematopoietic stem cells that reside within the BM. | Vascularization facilitates the proliferation and maintenance of HSC. | [42,43,44,45] |

| 6. Macrophages Macrophages are distributed in tissues throughout the body and contribute to both homeostasis and disease | Co-culture of human induced (hiPSC)—mesenchymal stem cells and macrophages recapitulate the tissue remodeling process of bone formation. | Macrophages help to retain the HC niche Through various cellular and molecular mechanisms. | HSC maintenance is performed by BM macrophages by mobilizing depleted HSC. | [16,17,46,47] |

| 7.BM Sympathetic nerves They involve in BM hematopoietic homeostasis by regulating HSC maintenance genes expression. Schwann cells localize close to HSCs and maintain HSC quiescence. Chemotherapy-induced bone marrow nerve injury. | Scope for studying co-cultures of neuronal cells with HSC supporting cells. Scope for creation of nerve tissue in BM environment. | Hematopoietic stem cell hibernation in the BM niche. Involve in BM function. Adult BM cells are sources of Schwann cells | Maintain HSC quiescence Repair of impaired hematopoietic regeneration. | [48,49] |

| 8 Bone marrow fat The intimate relationship among adipocytes, osteoblasts, and hematopoietic stem. Lipid rafts, the glycoprotein microdomains. | Fat components can be incorporated to the scaffolds at the time of fabrication for creating BM environment in co-culture systems. | Fat primes homing-related response of HSC/PHSC to SDF-1, through CXCR4. Fat also binds bone with calcium and forms bone grease. Play a role in signaling process, enhance the responsiveness of HSPC to homing. | The association between bone, fat, hematopoietic stem cell numbers, cytokine levels, and aging has been demonstrated. | [18,19,50,51] |

| 9. HSC cellular stress Oxidative stress and hypoxia. | Study of these conditions and induced effects of radiation and cytotoxic chemotherapy in 3-D scaffold. | Understanding the damage caused by external agents to the biology of HSC. | In vitro model of HSC cellular Stress. | [52] |

| 10. BM niche model of tissue and fluids. | Engineered bone marrow (eBM) on ‘bone marrow-on-a-chip’ microfluidic device is extended 3-D culture model. | Long term cultures of Bone HSC and PHSC. Myeloid toxicity studies. | Advanced stem Cell therapeutics. | [53,54,55] |

| 11. Hematopoietic malignancies CLL, ALL, CML, AML, MML leukemia and multiple myeloma | Fabrication of BM and HC environments mimicking 3-D scaffolds. | BM and cancer in vitro drug testing models. | In vitro disease model. | [56,57,58,59] |

| 3-D Scaffold | Materials | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Scaffold | PLGA, PCL, PGDA, PVA and other polymers, fats, minerals, and microelements. | Solvent casting and porogen leaching, gas foaming, freeze-drying, electrospinning, and 3-D scaffold printing. |

| Hydrogel | Hyaluronic acid, Chitosan, Alginate, Collagen, Gelatin, Agarose, and others | Gel casting and use of molecular cross-linkers. |

| Matrigel | Basement membrane extract. | Gel casting. |

| Biocomposite scaffold | polymers, cells, growth factors. | Bioprinting using ink-jet, laser, valve, and acoustic based. |

| Scaffold-free systems | No scaffold material required. Delivery of cells and active biomolecules. | Magnetic levitation and self-assembly hanging drop method for spheroid formation. |

| Process | Polymer | Pore Size (µm) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional gas foaming | PEGDA | 100–400 | [61,62] |

| CO2-water emulsion templating | Dextran | 6.25–7 | [63] |

| Dense gas CO2 + cross-linker | Elastin | 80 | [64] |

| Dense gas CO2 + cross-linker | Gelatin | 80–120 | [75] |

| Porogen leaching | PEG/PCL | 180–400 | [65] |

| Porogen leaching | PLGA | 250–500 | [6] |

| Freeze-drying | Collagen/Chitosan | 50 | [66] |

| Freeze-drying | Agarose | 71–187 | [67] |

| Freeze-drying | Chitosan, alginate | 60–150 | [68] |

| Freeze-drying | Gelatin | 40–500 | [69] |

| Freeze-drying | PVA/PCL | 30–300 | [70] |

| Freeze-drying | Chitosan/PCL | 10–100 | [72] |

| Electrospinning | Gelatin/PCL | 20–80 | [72,74] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janagama, D.; Hui, S.K. 3-D Cell Culture Systems in Bone Marrow Tissue and Organoid Engineering, and BM Phantoms as In Vitro Models of Hematological Cancer Therapeutics—A Review. Materials 2020, 13, 5609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13245609

Janagama D, Hui SK. 3-D Cell Culture Systems in Bone Marrow Tissue and Organoid Engineering, and BM Phantoms as In Vitro Models of Hematological Cancer Therapeutics—A Review. Materials. 2020; 13(24):5609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13245609

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanagama, Dasharatham, and Susanta K. Hui. 2020. "3-D Cell Culture Systems in Bone Marrow Tissue and Organoid Engineering, and BM Phantoms as In Vitro Models of Hematological Cancer Therapeutics—A Review" Materials 13, no. 24: 5609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13245609

APA StyleJanagama, D., & Hui, S. K. (2020). 3-D Cell Culture Systems in Bone Marrow Tissue and Organoid Engineering, and BM Phantoms as In Vitro Models of Hematological Cancer Therapeutics—A Review. Materials, 13(24), 5609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13245609