DFT Insights into the Role of Relative Positions of Fe and N Dopants on the Structure and Properties of TiO2

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

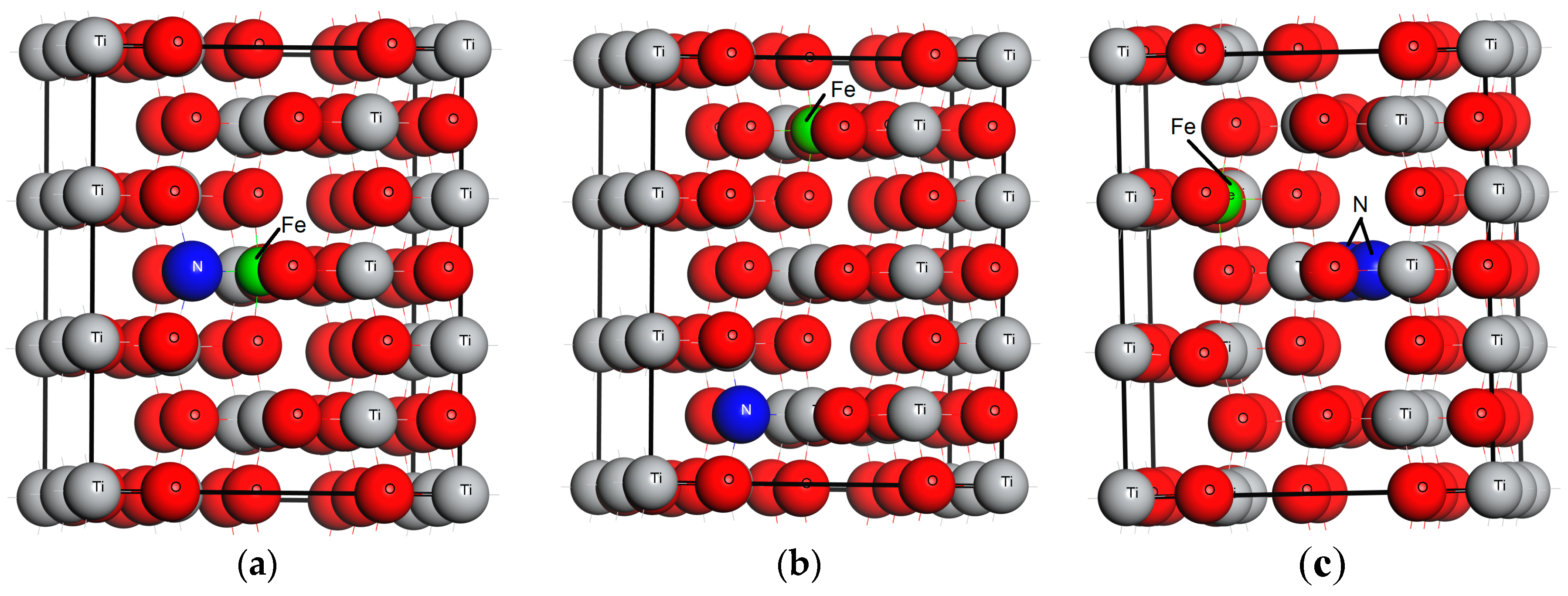

3.1. Geometrical Structure of the Modeled Systems

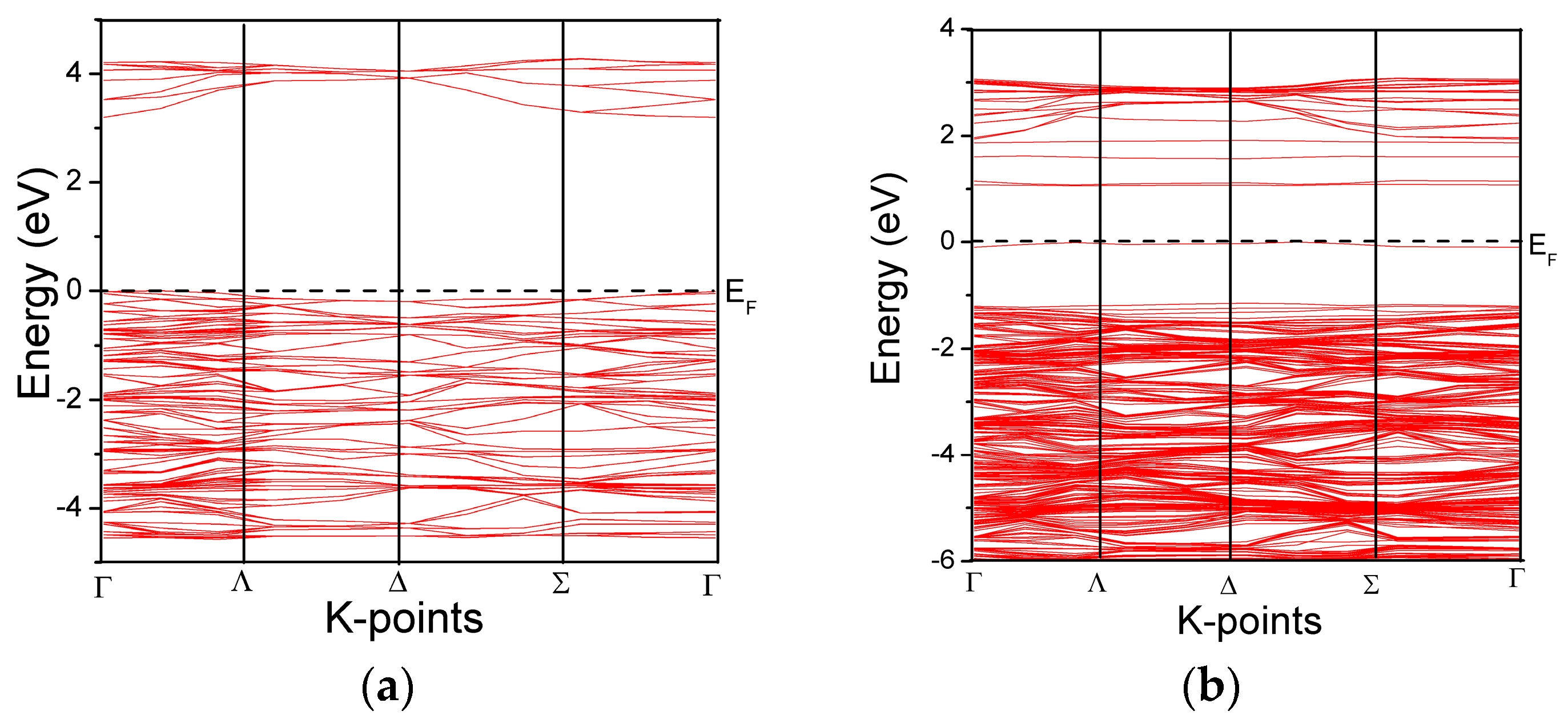

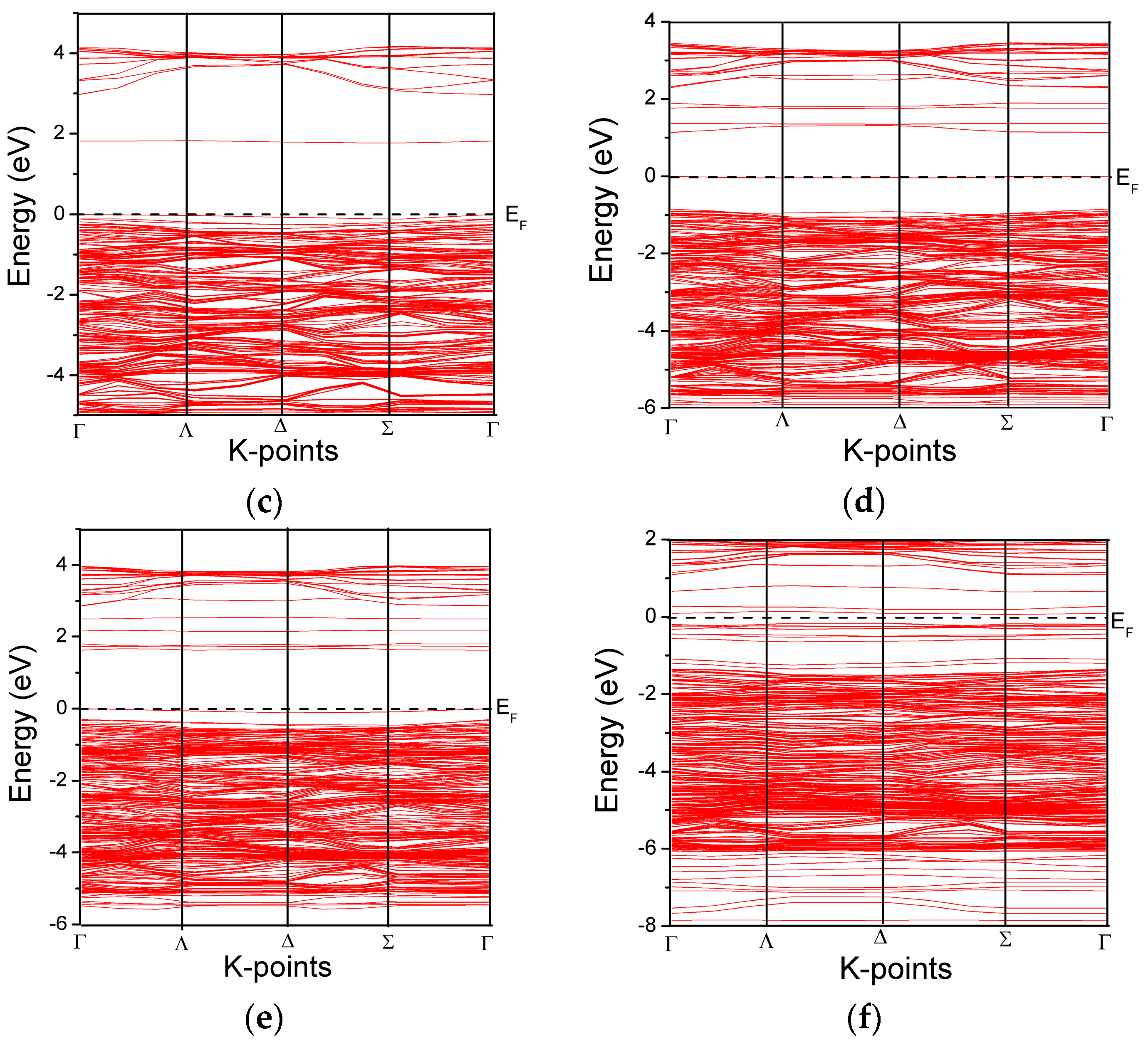

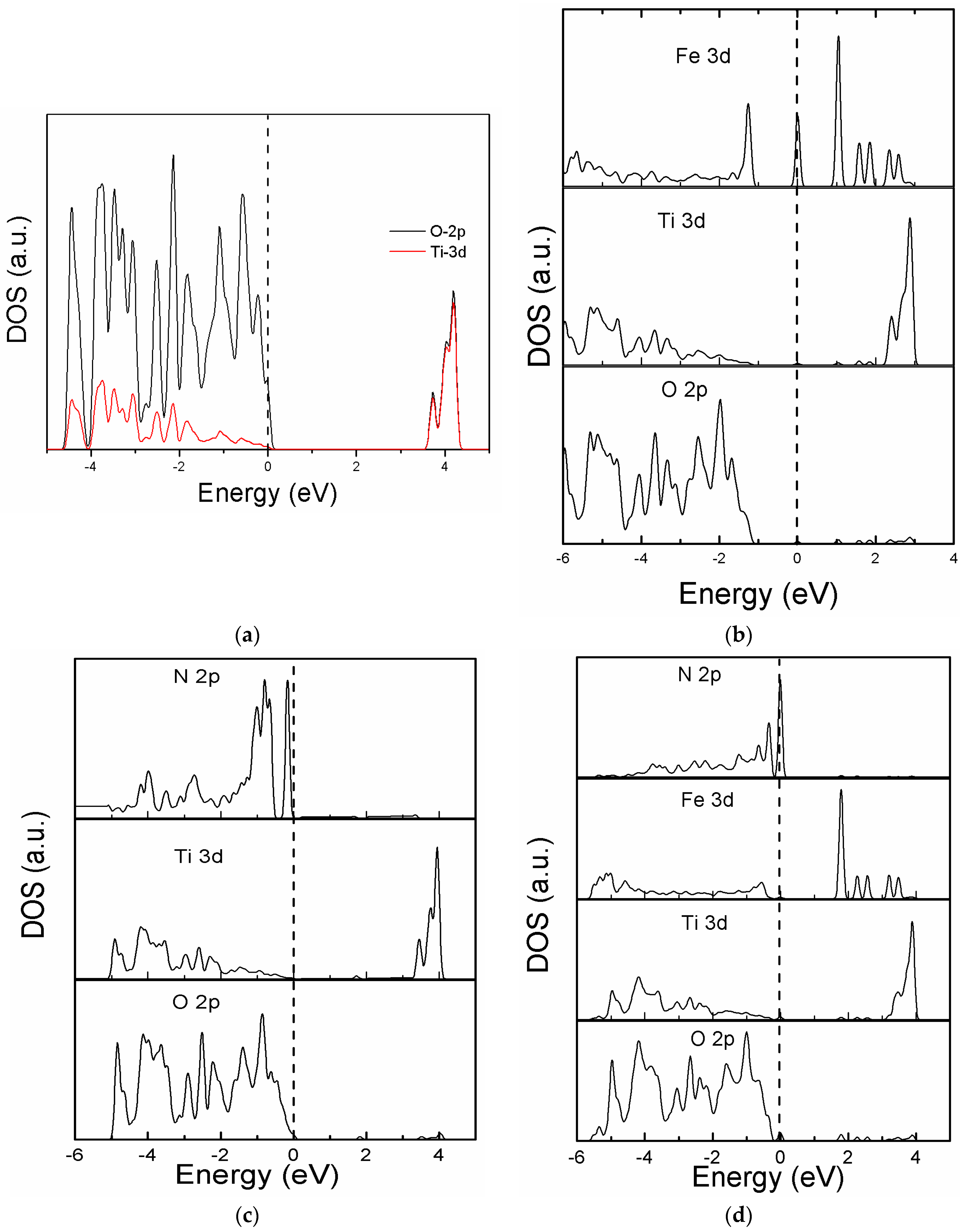

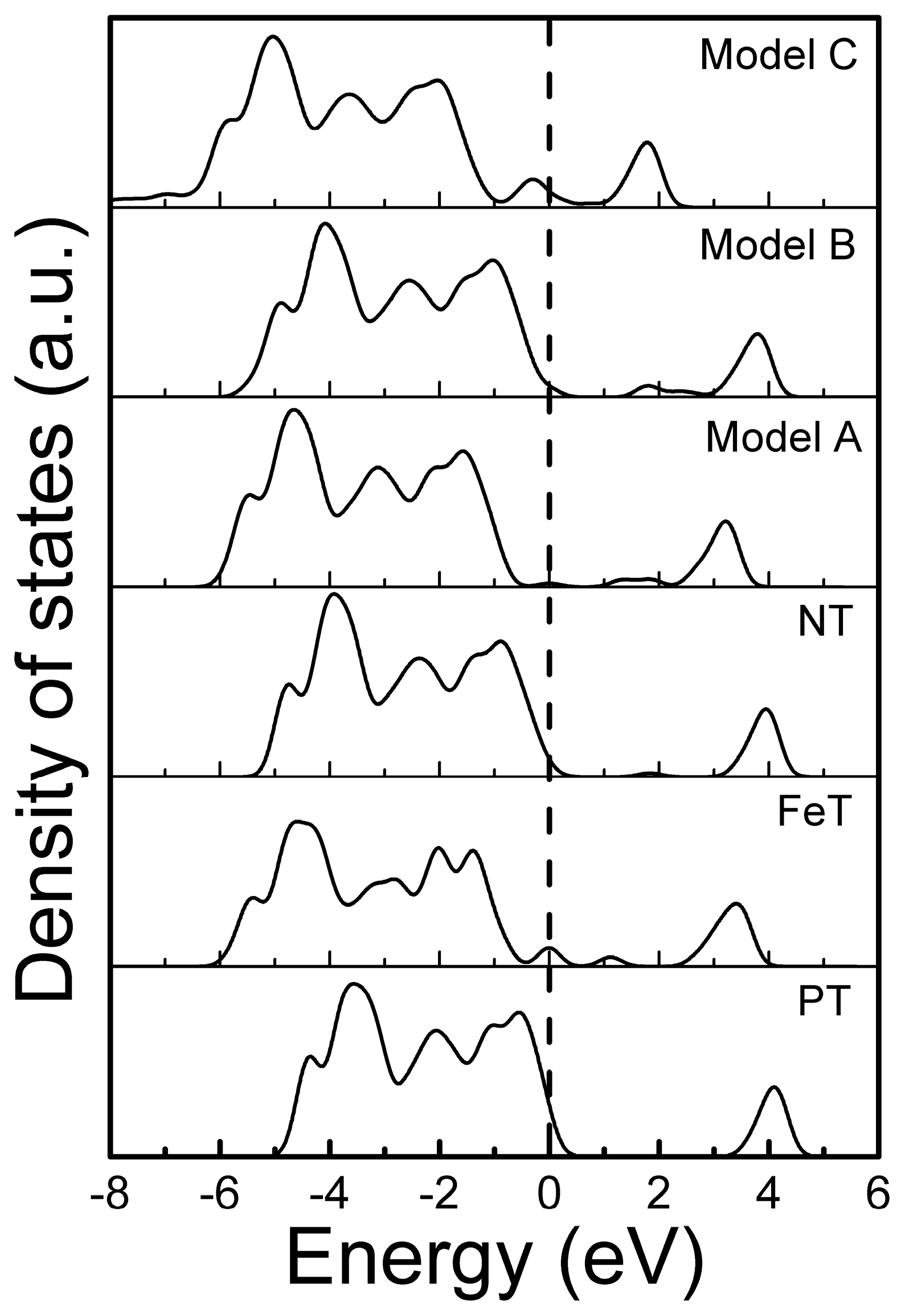

3.2. Band Structure and Partial Density of States of the Modeled Systems

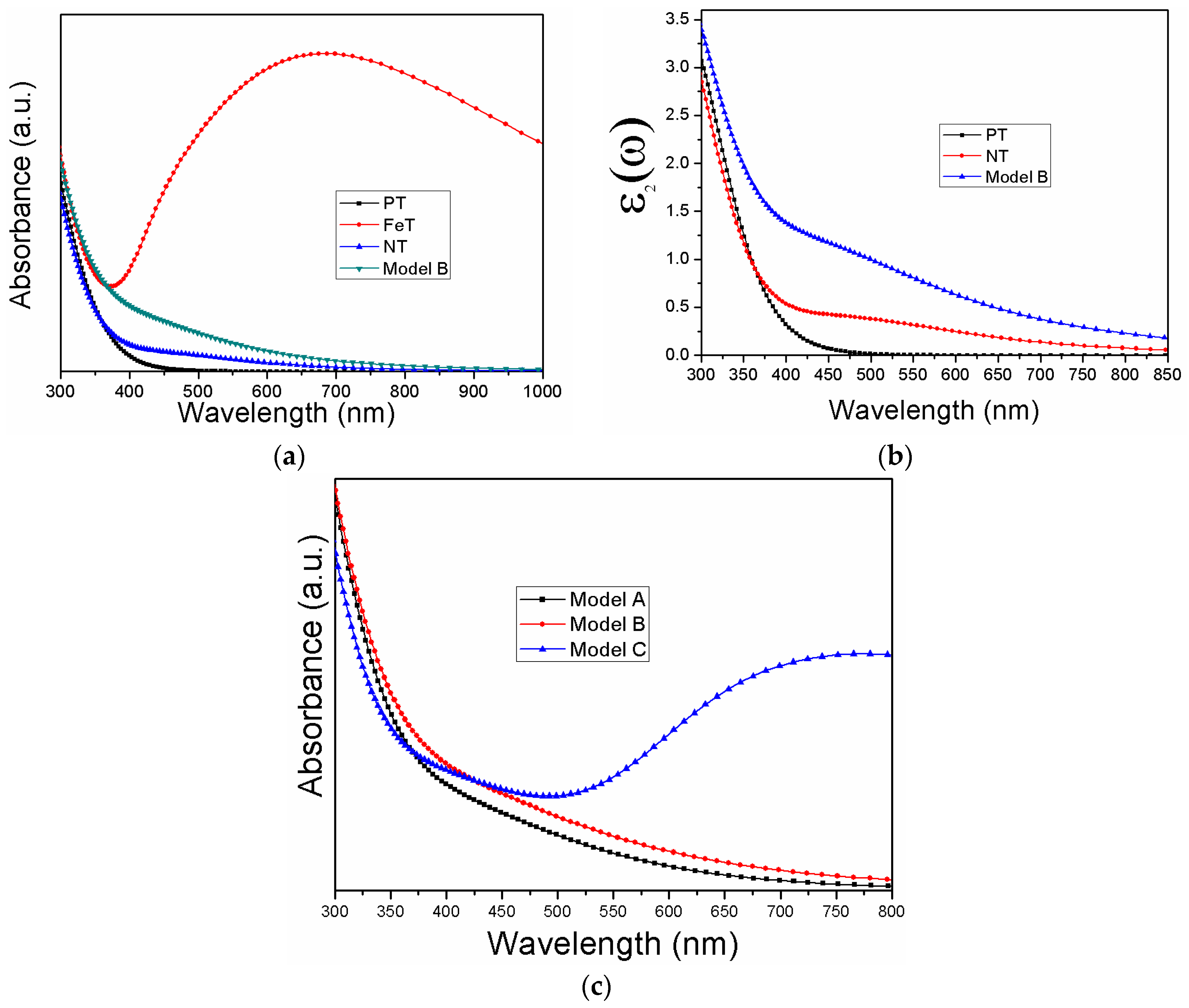

3.3. Photo-Response of the Modeled Systems

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sato, S. Photocatalytic activity of NOx-doped TiO2 in the visible light region. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1986, 123, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Xiong, T.; Li, T.; Yang, K. Tungsten and nitrogen co-doped TiO2 nano-powders with strong visible light response. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2008, 83, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Yi, Z.; Gul, S.R.; Wang, Y.; Fawad, U. Visible-light-active silver-, vanadium-codoped TiO2 with improved photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 5634–5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, J.; Yan, X.; Li, D.; Chen, S.; Chu, W. Characteristics of N-doped TiO2 nanotube arrays by N2-plasma for visible light-driven photocatalysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 9970–9976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonch-Bruevich, V.L.K.; Robert, S. The Electronic Structure of Heavily Doped Semiconductors; American Elsevier Pub. Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1966; pp. 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Di Valentin, C.; Pacchioni, G.; Selloni, A.; Livraghi, S.; Giamello, E. Characterization of paramagnetic species in N-doped TiO2 powders by EPR spectroscopy and DFT calculations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 11414–11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, H.; Xue, X.; Liu, Z. Doping TiO2 with boron or/and cerium elements: Effects on photocatalytic antimicrobial activity. Vacuum 2016, 131, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Khan, M.; Liu, W.; Xiang, W.; Guan, M.; Jiang, P.; Cao, W. Synthesis of nanocrystalline Ga–TiO2 powders by mild hydrothermal method and their visible light photoactivity. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 3075–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalow, K.A.; Otal, E.H.; Burnat, D.; Fortunato, G.; Emerich, H.; Ferri, D.; Heel, A.; Graule, T. Flame-made visible light active TiO2:Cr photocatalysts: Correlation between structural, optical and photocatalytic properties. Catal. Today 2013, 209, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukalova, M.; Bousa, M.; Bastl, Z.; Jirka, I.; Kavan, L. Electrochemical doping of compact TiO2 thin layers. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 25970–25977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Yi, Z.; Gul, S.R.; Fawad, U.; Muhammad, W. Anomalous photodegradation response of Ga, N codoped TiO2 under visible light irradiations: An interplay between simulations and experiments. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2017, 110, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzwigaj, S.; Arrouvel, C.; Breysse, M.; Geantet, C.; Inoue, S.; Toulhoat, H.; Raybaud, P. DFT makes the morphologies of anatase-TiO2 nanoparticles visible to IR spectroscopy. J. Catal. 2005, 236, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Cao, W. Development of photocatalyst by combined nitrogen and yttrium doping. Mater. Res. Bull. 2014, 49, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Gao, L. One-step hydrothermal synthesis of C, W-codoped mesoporous TiO2 with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 551, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Herrmann, J.-M.; Pichat, P. Room temperature photocatalytic oxidation of liquid cyclohexane into cyclohexanone over neat and modified TiO2. Catal. Lett. 1989, 3, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lu, Z.; Yue, L.; Liu, J.; Gan, Z.; Shu, C.; Zhang, T.; Shi, J.; Xiong, R. (Mo + N) codoped TiO2 for enhanced visible-light photoactivity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 9355–9361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Cao, C.; Erickson, L.; Hohn, K.; Maghirang, R.; Klabunde, K. Photo-catalytic degradation of Rhodamine B on C-, S-, N-, and Fe-doped TiO2 under visible-light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 91, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Wu, C.; Han, S.; Yao, N.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Chi, B.; Pu, J.; Jian, L. Theoretical study on the electronic and optical properties of (N, Fe)-codoped anatase TiO2 photocatalyst. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 6067–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.J.; Segall, M.D.; Pickard, C.J.; Hasnip, P.J.; Probert, M.I.J.; Refson, K.; Payne, M.C. First principles methods using CASTEP. Zeitschrift für Kristallographie 2005, 220, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Song, Y.; Chen, N.; Cao, W. Effect of V doping concentration on the electronic structure, optical and photocatalytic properties of nano-sized V-doped anatase TiO2. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2013, 142, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Cao, W. Cationic (V, Y)-codoped TiO2 with enhanced visible light induced photocatalytic activity: A combined experimental and theoretical study. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 114, 183514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Xu, J.; Chen, N.; Cao, W. First principle calculations of the electronic and optical properties of pure and (Mo, N) co-doped anatase TiO2. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 513, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdett, J.K.; Hughbanks, T.; Miller, G.J.; Richardson, J.W.; Smith, J.V. Structural-electronic relationships in inorganic solids: Powder neutron diffraction studies of the rutile and anatase polymorphs of titanium dioxide at 15 and 295 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 3639–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiullah Khan, J.X.; Cao, W.; Liu, Z.-K. Mo-doped TiO2 with Enhanced Visible Light Photocatalytic Activity: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2013, 14, 6865–6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Cao, W.; Chen, N.; Asadullah; Iqbal, M.Z. Ab-initio calculations of synergistic chromium–nitrogen codoping effects on the electronic and optical properties of anatase TiO2. Vacuum 2013, 92, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Jiang, P.; Li, J.; Cao, W. Enhanced photoelectrochemical properties of TiO2 by codoping with tungsten and silver. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 153103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafizas, A.; Crick, C.; Parkin, I.P. The combinatorial atmospheric pressure chemical vapour deposition (cAPCVD) of a gradating substitutional/interstitial N-doped anatase TiO2 thin-film; UVA and visible light photocatalytic activities. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2010, 216, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.-N. First-principles study of the hydrogen doping influence on the geometric and electronic structures of N-doped TiO2. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2008, 458, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umebayashi, T.; Yamaki, T.; Itoh, H.; Asai, K. Analysis of electronic structures of 3d transition metal-doped TiO2 based on band calculations. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2002, 63, 1909–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Cao, W.; Chen, N.; Usman, Z.; Khan, D.F.; Toufiq, A.M.; Khaskheli, M.A. Influence of tungsten doping concentration on the electronic and optical properties of anatase TiO2. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2013, 13, 1376–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, H.-T.; He, J.; Tian, Y. Ab initio investigations of optical properties of the high-pressure phases of ZnO. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 125132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Systems | O-Ti | O-O | O-Fe | Fe-Ti | O-N | N-Ti | Fe-N | Ti-Ti | N-N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | 1.9622 | 2.6346 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FeT | 1.9488 | 2.6990 | 1.8900 | 2.9945 | - | - | - | - | - |

| NT | 1.9473 | 2.6945 | - | - | 2.6675 | 2.0390 | - | - | - |

| Model A | 1.9479 | 2.6766 | 1.9289 | 2.9684 | 2.8328 | 2.0059 | 2.9684 | - | - |

| Model B | 1.9520 | 2.7025 | 1.8739 | - | 2.8018 | 1.8951 | - | 2.9780 | - |

| Model C | 1.9479 | 2.7035 | 1.8940 | 2.8534 | 2.2241 | 2.7725 | - | 2.9377 | 2.2207 |

| PT | FeT | NT | Model A | Model B | Model C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band gap (eV) | 3.20 | 2.061 | 2.867 | 1.851 | 1.798 | 0.527 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramin Gul, S.; Khan, M.; Yi, Z.; Wu, B. DFT Insights into the Role of Relative Positions of Fe and N Dopants on the Structure and Properties of TiO2. Materials 2018, 11, 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11020313

Ramin Gul S, Khan M, Yi Z, Wu B. DFT Insights into the Role of Relative Positions of Fe and N Dopants on the Structure and Properties of TiO2. Materials. 2018; 11(2):313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11020313

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamin Gul, Sahar, Matiullah Khan, Zeng Yi, and Bo Wu. 2018. "DFT Insights into the Role of Relative Positions of Fe and N Dopants on the Structure and Properties of TiO2" Materials 11, no. 2: 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11020313

APA StyleRamin Gul, S., Khan, M., Yi, Z., & Wu, B. (2018). DFT Insights into the Role of Relative Positions of Fe and N Dopants on the Structure and Properties of TiO2. Materials, 11(2), 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11020313