Numerical Study of Combustion in a Methane–Hydrogen Co-Fired W-Shaped Radiant Tube Burner

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Methodologies

2.1. CFD Models

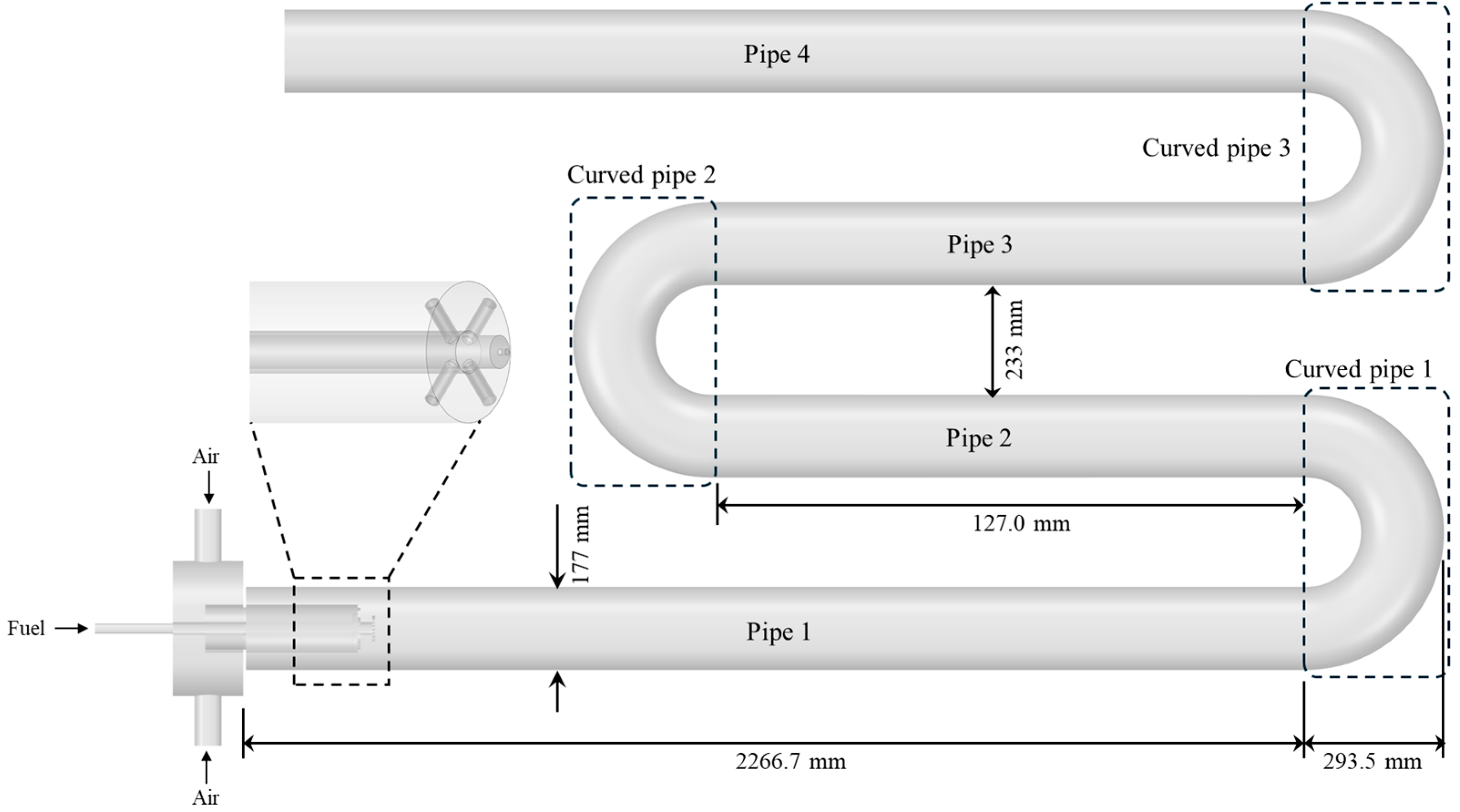

2.2. Geometry Modeling for Radiant Tube Burner

3. Results and Discussion

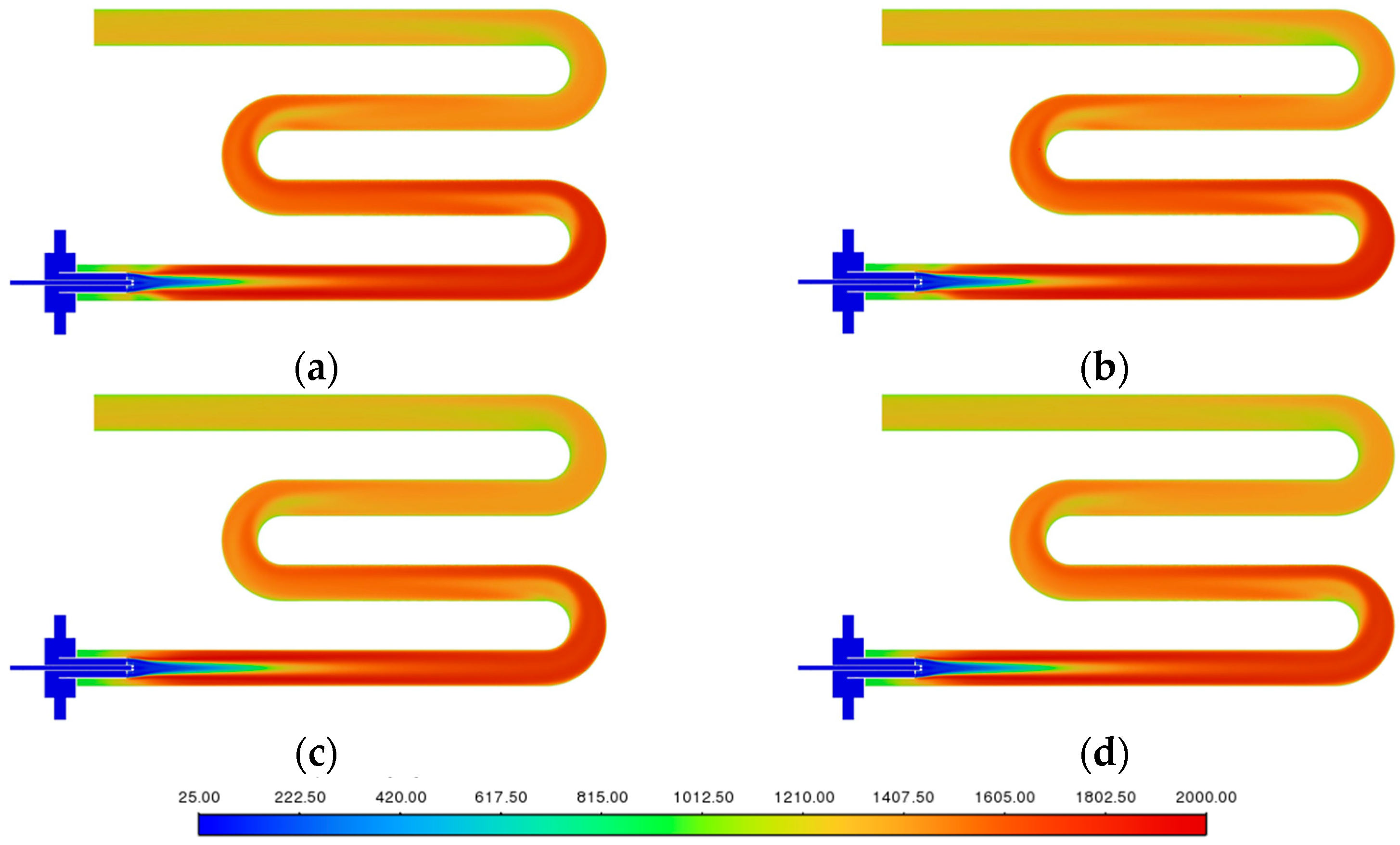

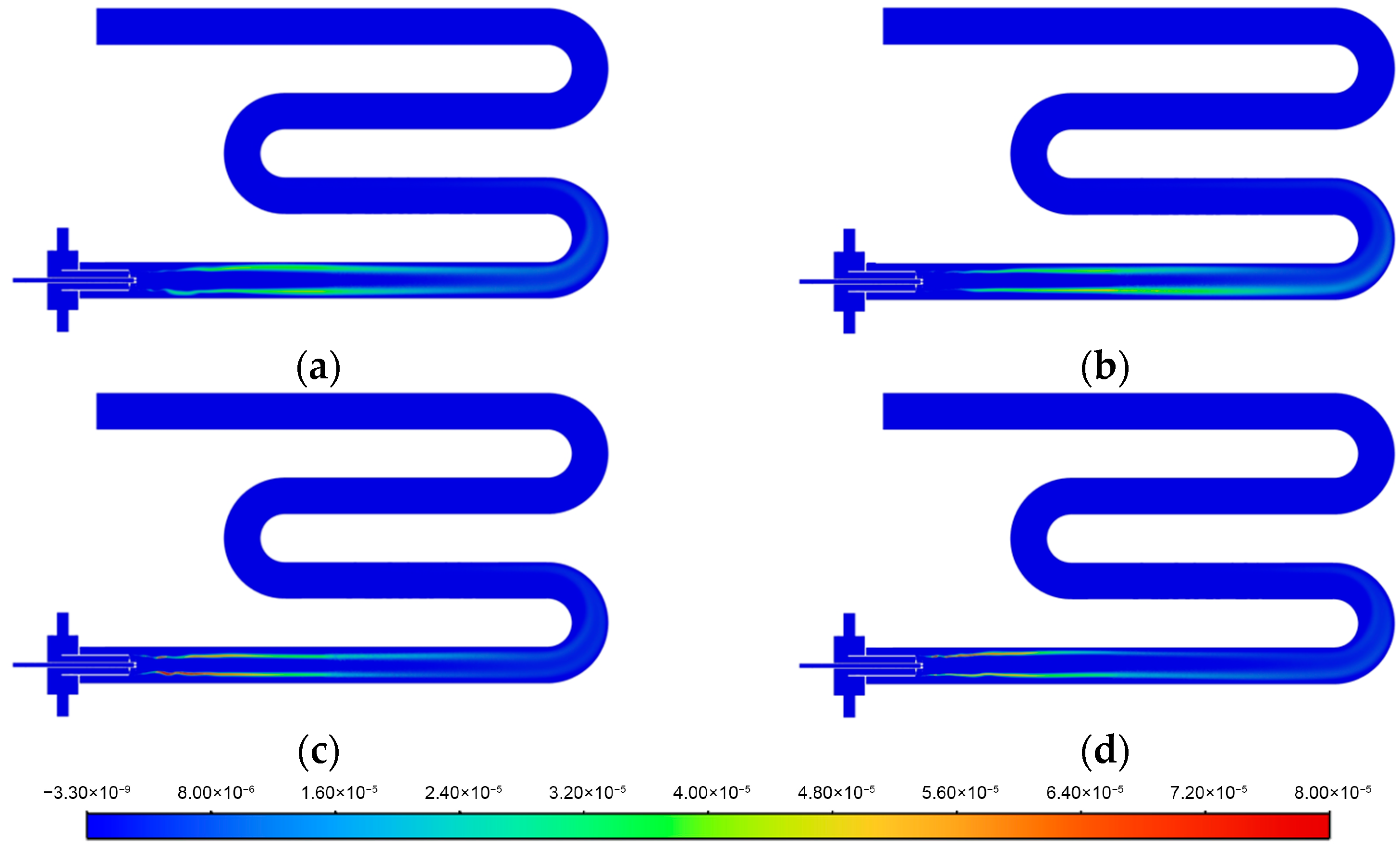

3.1. Selection of CH4 Reaction Mechanism

3.2. Flame Shape near the Injector

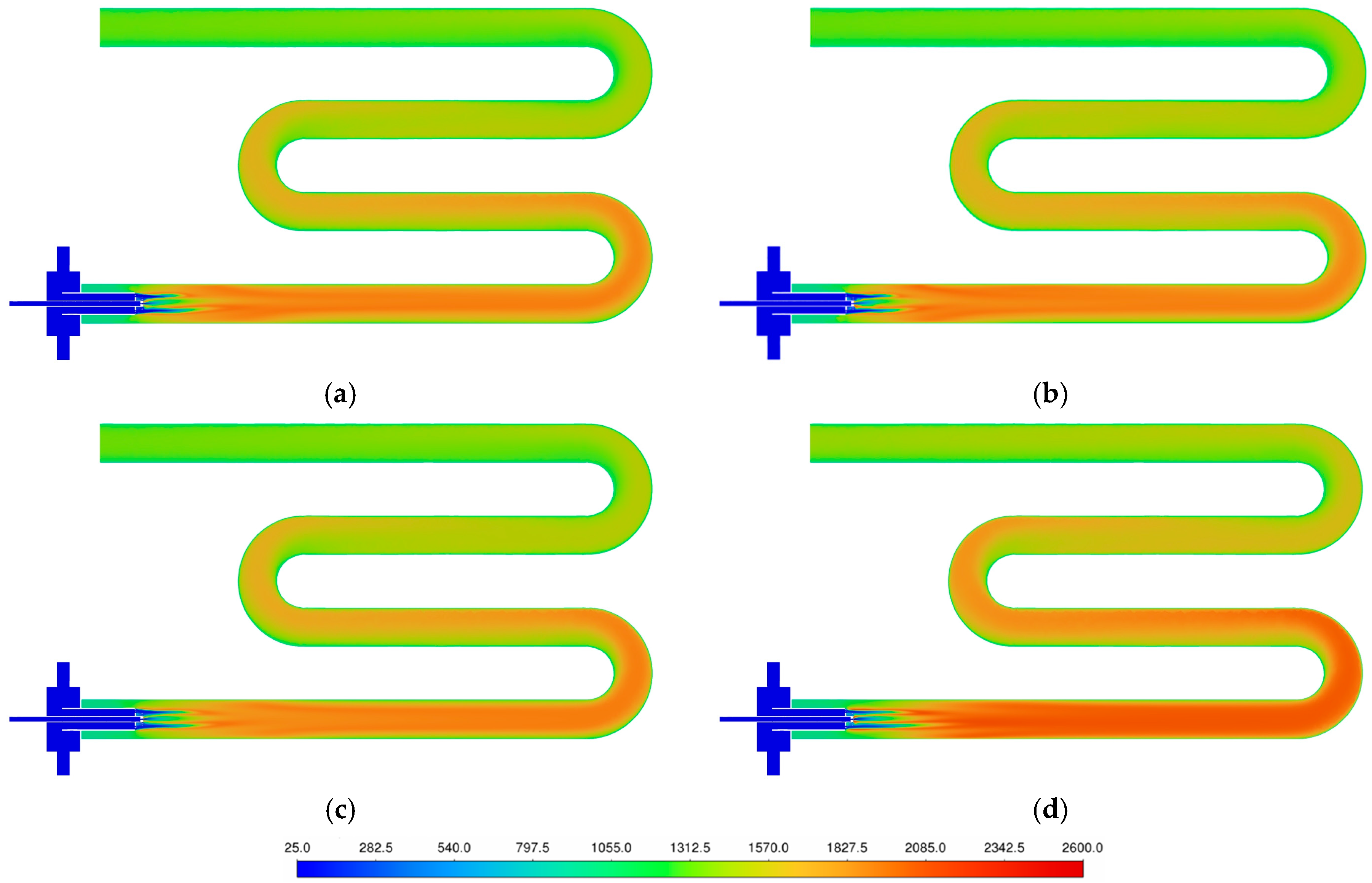

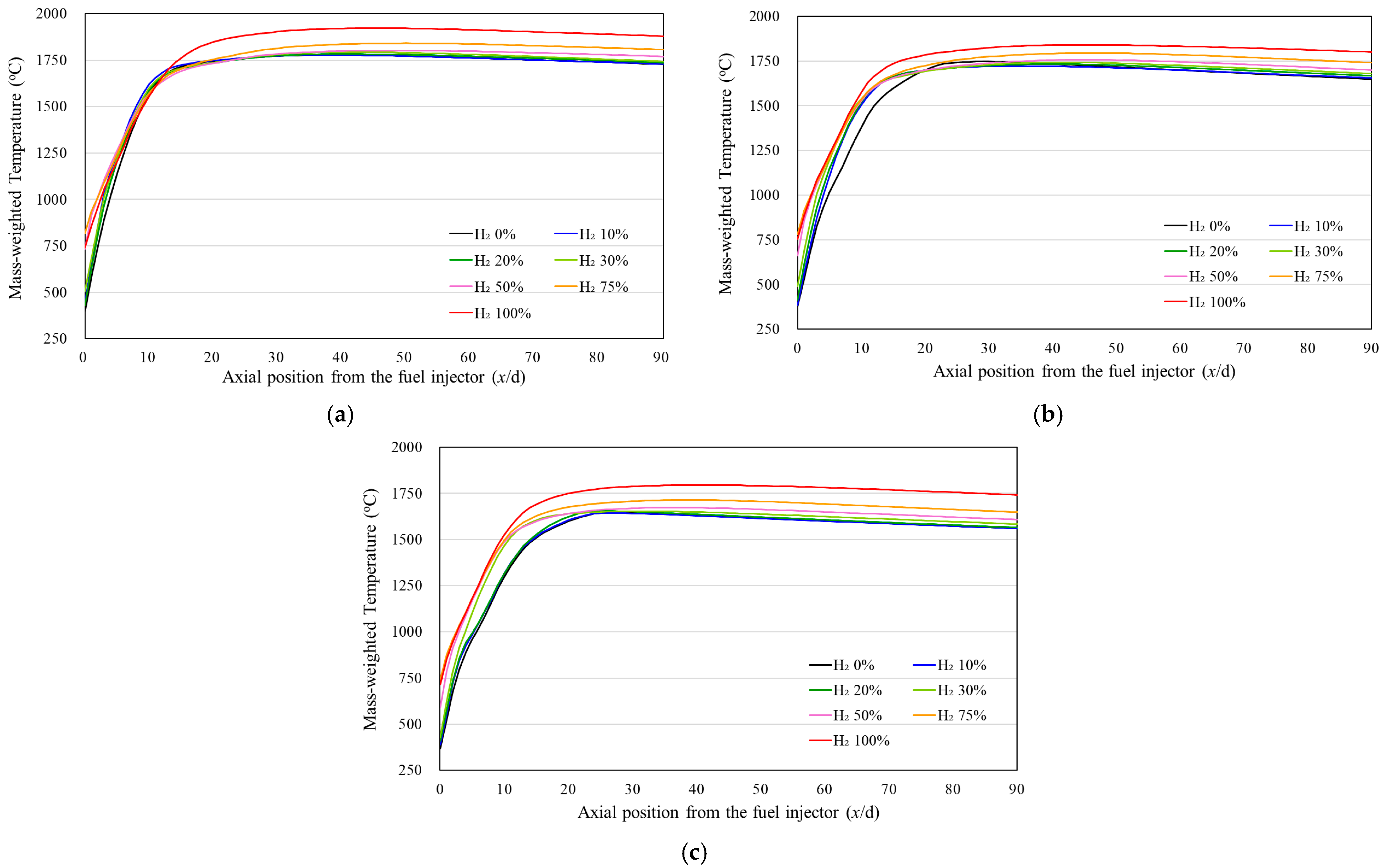

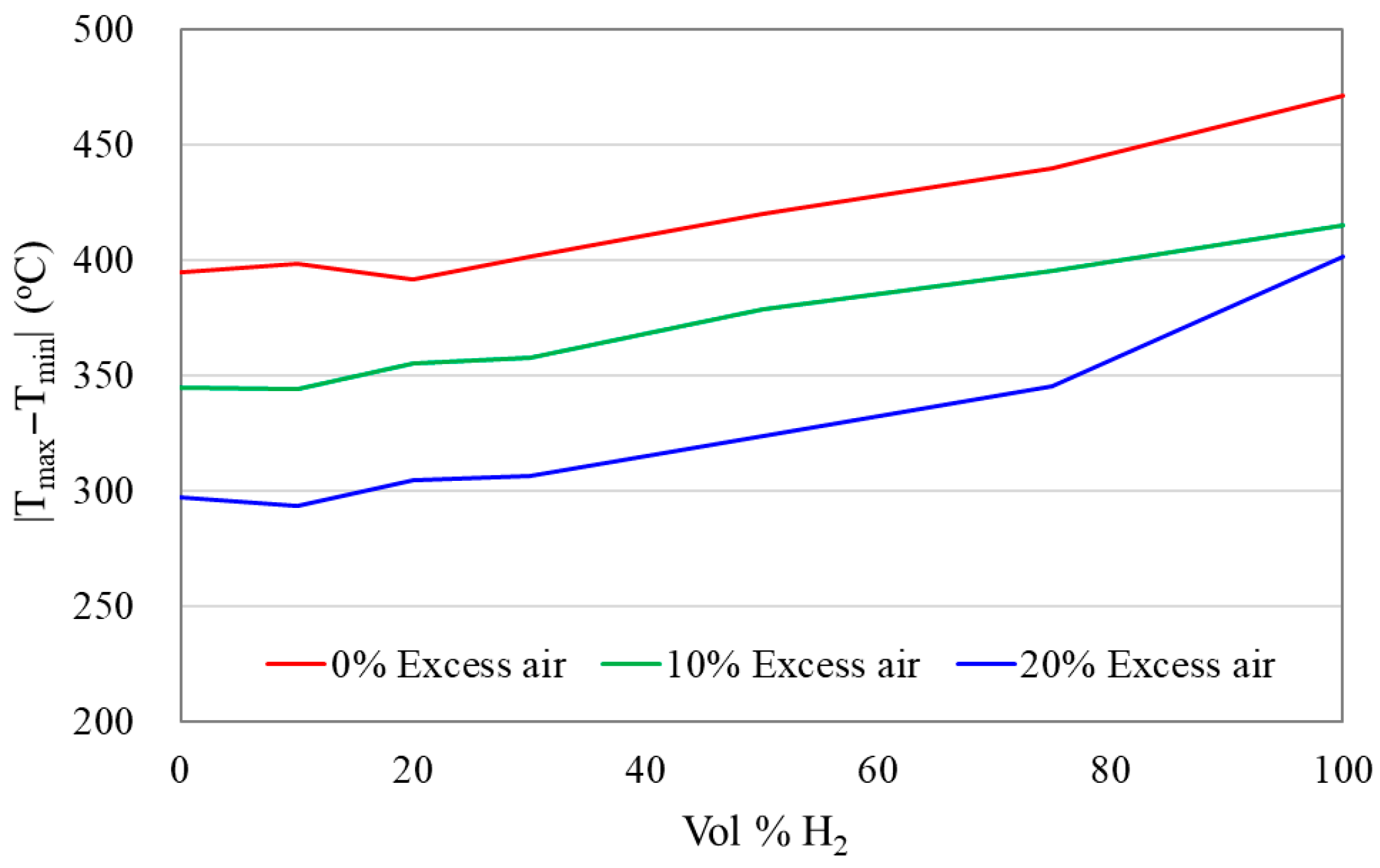

3.3. Temperature Uniformity

3.4. Effects of Hydrogen Enrichment and Excess-Air Ratio on Emission

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| EDC | Eddy dissipation concept |

| ISAT | In situ adaptive tabulation |

| RTB | Radiant tube burner |

References

- Fan, H.; Feng, J.; Bai, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; Gao, J.; Liu, C.; Jia, L. Numerical simulation on heating performance and emission characteristics of a new multi-stage dispersed burner for gas-fired radiant tubes. Therm. Sci. 2022, 26, 3787–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsioumanis, N.; Brammer, J.G.; Hubert, J. Flow processes in a radiant tube burner: Combusting flow. Energy Conv. Manag. 2011, 52, 2667–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Pang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Z. Modeling approach and numerical analysis of a roller-hearth reheating furnace with radiant tubes and heating process optimization. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 28, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamme, M.; Milani, A.; Wünning, J.G.; Blasiak, W.; Yang, W.; Szewczyk, D.; Sudo, J.; Mochida, S. Radiant tube burners. In Industrial Combustion Testing, 1st ed.; Baukal, C.E., Ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 487–504. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; De, S.; Zhang, H. Comparative performance assessment of a U-shaped recuperative radiant tube using MILD combustion. J. Energy Eng. 2018, 144, 04018029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Guahk, Y.T.; Ko, C. Numerical simulation of an industrial radiant tube burner using OpenFOAM. Fuel Commun. 2024, 19, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Tong, J.; Lu, X. Experimental studies on the heating performance and emission characteristics of a W-shaped regenerative radiant tube burner. Fuel 2014, 135, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. Performance analysis of a novel W-type radiant tube. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 152, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, W.; Ha, J.; Roh, Y.; Lee, Y. Improvement of Radiant Heat Efficiency of the Radiant Tube Used for Continuous Annealing Line by Application of Additive Manufacturing Technology. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.M.; Millera, A.; Bilbao, R.; Alzueta, M.U. Combustion model evaluation in a CFD simulation of a single-ended radiant-tube burner. Fuel 2020, 276, 118013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandadi, V.; Park, C.; Kaviany, M. Superadiabatic radiant porous burner with preheater and radiation corridors. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 64, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Li, Z.; Jia, L.; Dou, Y. Numerical Simulation Study on the Performance of a New Gas Burner for Radiant Heating. Fluids 2025, 10, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, E.; Li, X.; Hu, Z.; Liu, D.; Yu, Y. Numerical Investigation and Improvement of Coke Oven Gas-Fired W-Shaped Radiant Tubes for NOx Reduction. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 4925–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glarborg, P.; Miller, J.A.; Ruscic, B.; Klippenstein, S.J. Modeling nitrogen chemistry in combustion: A review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 67, 31–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS) in Global Energy and Climate Model. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-and-climate-model/stated-policies-scenario-steps (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Boushaki, T.; Dhué, A.; Gökalp, I.; Halter, F. Effects of hydrogen and steam addition on laminar burning velocity of methane–air mixtures: Experimental and numerical analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 6941–6952. [Google Scholar]

- Dirrenberger, P.; Le Gall, P.; Bounaceur, R.; Herbinet, O.; Glaude, P.A.; Konnov, A.; Battin-Leclerc, F. Measurements of laminar flame velocity for components of natural gas. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 3875–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, T.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, C.; Lu, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Numerical simulation and field experimental study of hydrogen-enriched natural gas combustion in industrial boilers. Processes 2024, 12, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Persis, S.; Idir, M.; Molet, J.; Pillier, L. Effect of hydrogen addition on NOx formation in high-pressure counter-flow premixed CH4/air flames. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 23484–23502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houshfar, E.; Løvås, T.; Skreiberg, Ø. Effect of excess air ratio and temperature on NOx emission from grate combustion of biomass fuels. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 4145–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Ahn, B.; Kang, D.; Hwang, J.; Park, Y.; Choi, M. CFD study on combustion and emissions characteristics of methane-hydrogen co-firing in an EV burner. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 73, 106596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Zhou, S.; Qiu, H.; Zhao, J.; Fan, Y. Experiment and numerical study of the combustion behavior of hydrogen-blended natural gas in swirl burners. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 39, 102468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS Inc. Ansys Fluent Theory Guide; ANSYS Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørn, F. Magnussen, On the Structure of Turbulence and a Generalized Eddy Dissipation Concept for Chemical Reaction in Turbulent Flow. In Proceedings of the 19th AIAA Aerospace Science Meeting, St. Louis, MO, USA, 12–15 January 1981. [Google Scholar]

- University of California, Berkeley. GRI-Mech 3.0. Available online: http://combustion.berkeley.edu/gri-mech/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Westbrook, C.K.; Dryer, F.L. Simplified reaction mechanisms for the oxidation of hydrocarbon fuels in flames. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1981, 27, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Kazakov, A.; Dryer, F.L. An updated comprehensive kinetic model of hydrogen combustion. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 2004, 36, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Pope, S.B. An improved algorithm for in situ adaptive tabulation. J. Comput. Phys. 2009, 228, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldovich, Y.B. The oxidation of nitrogen in combustion and explosions. J. Acta Physicochim. 1946, 21, 577–628. [Google Scholar]

- Hermanns, R.T.E. Laminar Burning Velocities of Methane-Hydrogen-Air Mixtures. Ph.D. Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, F. The Effect of Hydrogen Concentration on the Flame Stability and Laminar Burning Velocity of Hydrogen-Hydrocarbon-Carbon Dioxide Mixtures. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koroll, G.W.; Kumar, R.K.; Bowles, E.M. Burning velocities of hydrogen–air mixtures. Combust. Flame 1993, 94, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Dai, P.; Gou, X.; Chen, Z. A review of laminar flame speeds of hydrogen and syngas measured from propagating spherical flames. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2020, 1–4, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitu, M.; Razus, D.; Schroeder, V. Laminar Burning Velocities of Hydrogen-Blended Methane–Air and Natural Gas–Air Mixtures, Calculated from the Early Stage of p(t) Records in a Spherical Vessel. Energies 2021, 14, 7556. [Google Scholar]

- Warnatz, J.; Mass, U.; Dibble, R.W. Combustion: Physical and Chemical Fundamentals, Modeling and Simulation, Experiments, Pollutant Formation; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 107–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gran, I.R.; Magnussen, B.F. A Numerical study of a bluff-body stabilized diffusion flame. Part 2. influence of combustion modeling and finite-rate chemistry. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1996, 119, 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, F.M. Viscous Fluid Flow, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Singapore, 1991; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

| Case * | Excess Air (%) | %Vol H2 | Case * | Excess Air (%) | %Vol H2 | Case * | Excess Air (%) | %Vol H2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA00-H000 | 0 | 0 | EA10-H000 | 10 | 0 | EA20-H000 | 20 | 0 |

| EA00-H010 | 0 | 10 | EA10-H010 | 10 | 10 | EA20-H010 | 20 | 10 |

| EA00-H020 | 0 | 20 | EA10-H020 | 10 | 20 | EA20-H020 | 20 | 20 |

| EA00-H030 | 0 | 30 | EA10-H030 | 10 | 30 | EA20-H030 | 20 | 30 |

| EA00-H050 | 0 | 50 | EA10-H050 | 10 | 50 | EA20-H050 | 20 | 50 |

| EA00-H075 | 0 | 75 | EA10-H075 | 10 | 75 | EA20-H075 | 20 | 75 |

| EA00-H100 | 0 | 100 | EA10-H100 | 10 | 100 | EA20-H100 | 20 | 100 |

| Vol% of H2 | 0% Excess Air | 10% Excess Air | 20% Excess Air |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (CH4) | 0.364 | 0.330 | 0.281 |

| 10 | 0.392 | 0.355 | 0.305 |

| 20 | 0.423 | 0.383 | 0.332 |

| 30 | 0.470 | 0.415 | 0.360 |

| 50 | 0.628 | 0.567 † | 0.489 † |

| 75 | 1.040 | 0.940 † | 0.810 † |

| 100 (H2) | 2.633 | 2.378 † | 2.051 † |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jeong, D.; Ha, S.; Seo, J.; Ahn, J.; Lee, D.; Bae, B.; Kwon, J.; Lee, G.G. Numerical Study of Combustion in a Methane–Hydrogen Co-Fired W-Shaped Radiant Tube Burner. Energies 2026, 19, 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020557

Jeong D, Ha S, Seo J, Ahn J, Lee D, Bae B, Kwon J, Lee GG. Numerical Study of Combustion in a Methane–Hydrogen Co-Fired W-Shaped Radiant Tube Burner. Energies. 2026; 19(2):557. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020557

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Daun, Seongbong Ha, Jeongwon Seo, Jinyeol Ahn, Dongkyu Lee, Byeongyun Bae, Jongseo Kwon, and Gwang G. Lee. 2026. "Numerical Study of Combustion in a Methane–Hydrogen Co-Fired W-Shaped Radiant Tube Burner" Energies 19, no. 2: 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020557

APA StyleJeong, D., Ha, S., Seo, J., Ahn, J., Lee, D., Bae, B., Kwon, J., & Lee, G. G. (2026). Numerical Study of Combustion in a Methane–Hydrogen Co-Fired W-Shaped Radiant Tube Burner. Energies, 19(2), 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020557