This chapter interprets the observed permeability evolution of fractured-porous carbonate rocks under coupled temperature and effective stress conditions. We first explain the stress-controlled exponential-type permeability decay and its microphysical origin, and then discuss why the temperature sensitivity is progressively attenuated by increasing effective stress within the investigated 20–80 °C conditions. Based on these observations, two full-path conceptual models are proposed for permeability evolution under effective-stress loading or temperature loading. Finally, we discuss the engineering relevance of the proposed exponential model and clarify its current applicability and limitations.

5.1. Stress-Controlled Permeability Decay and Full-Path Conceptual Model

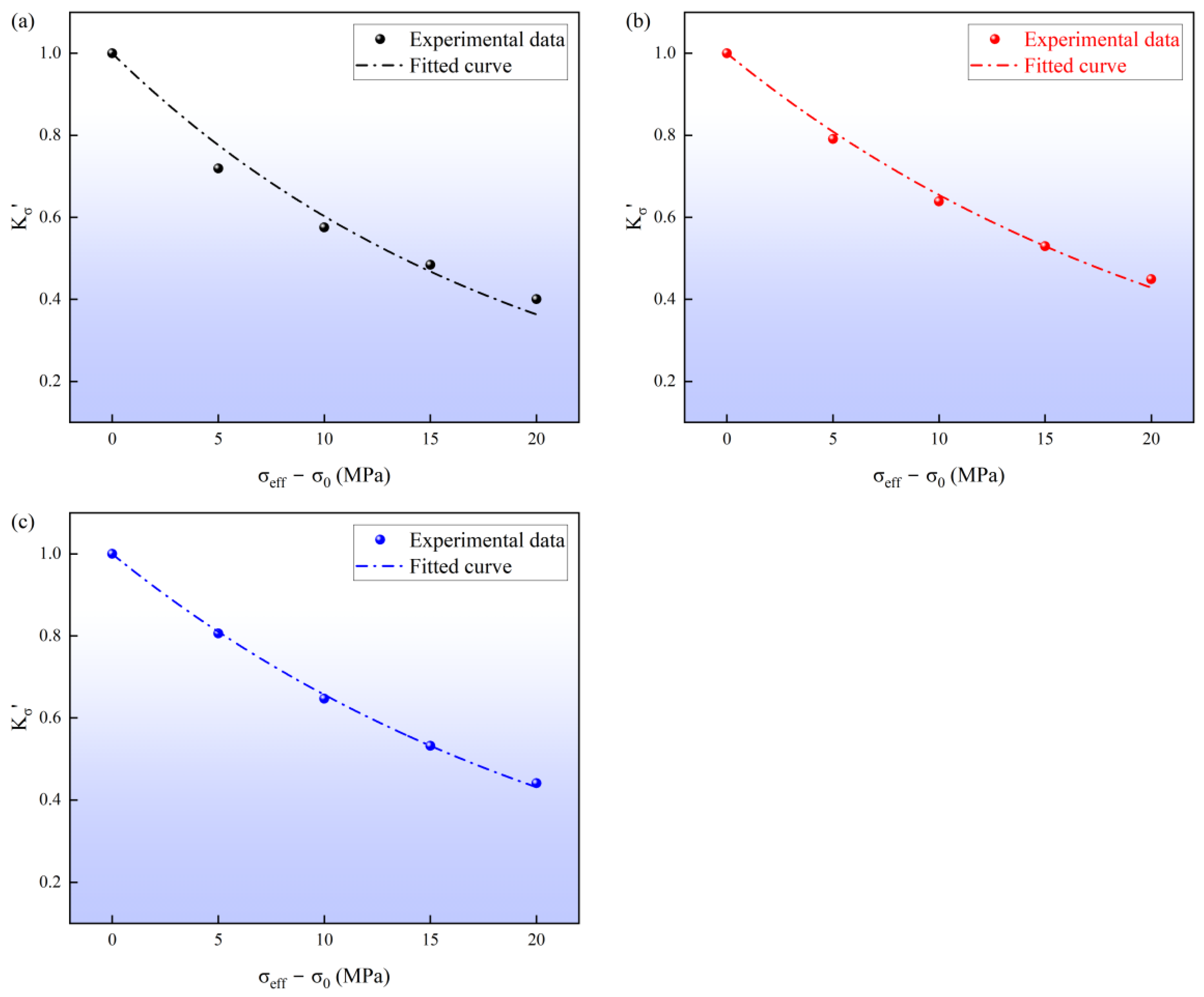

Table 7 shows that the fitted stress-related exponential decay parameter

for the North, Middle, and South cores is 0.0459, 0.0384, and 0.0376 MPa

−1. This level of stress sensitivity is comparable to that reported for carbonate cores from the Malm geothermal reservoir in Germany [

50] and is also consistent with observations in tight gas sandstones, where permeability decreases markedly as effective stress increases [

51].

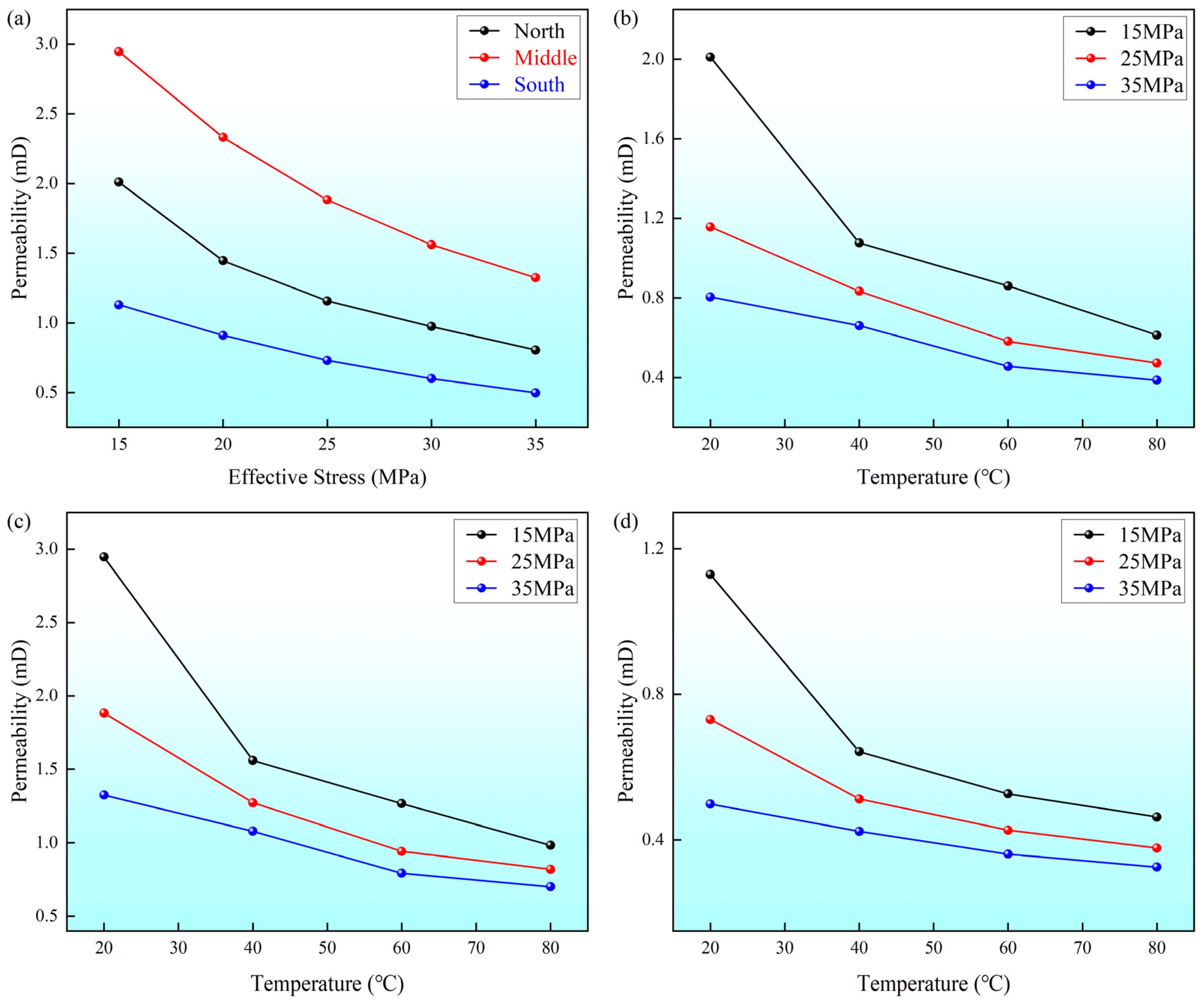

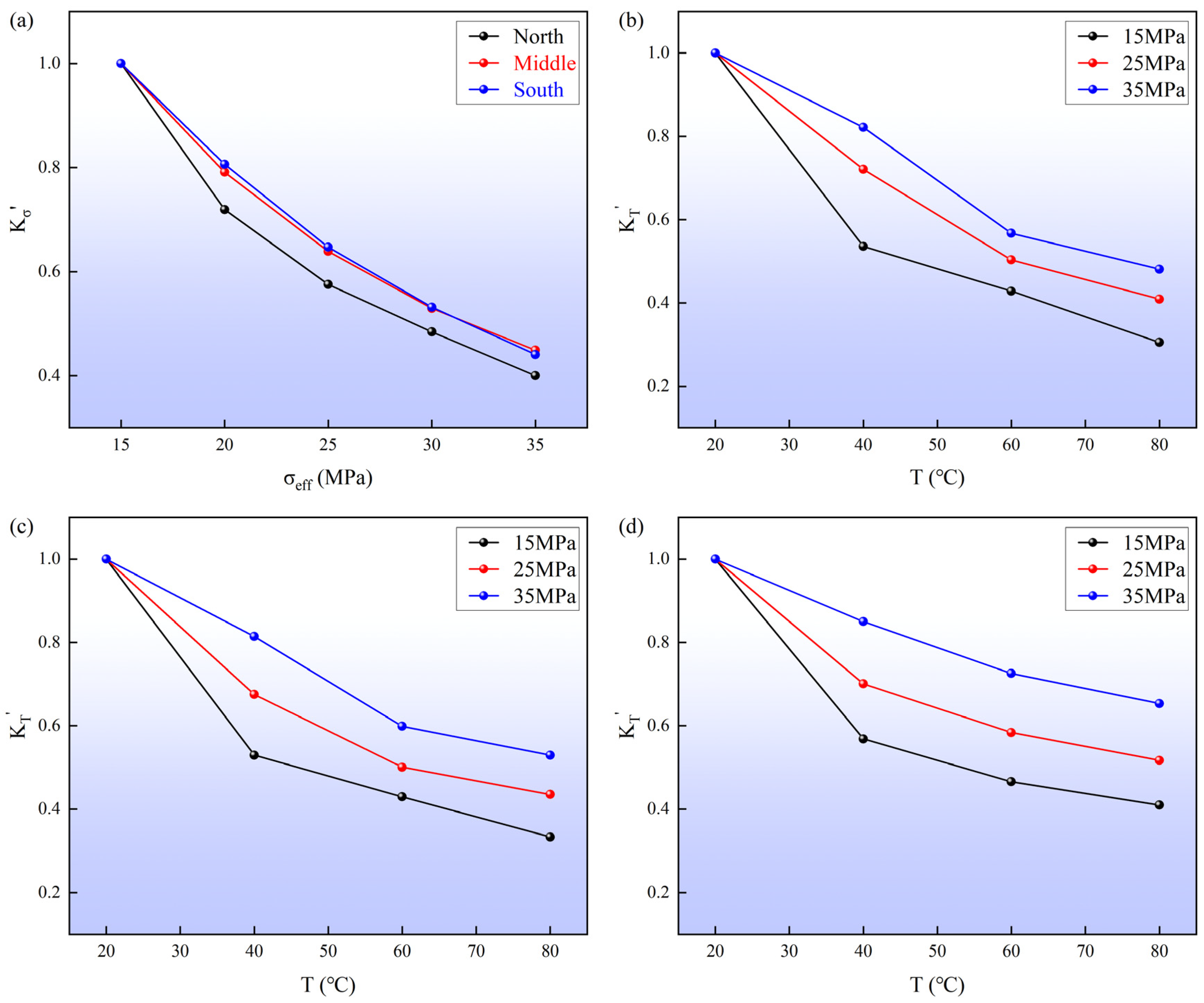

The exponential-type decay of permeability with increasing effective stress (

Figure 7) can be interpreted as a non-uniform progressive closure of the fracture-pore network. Farahani et al. [

52] suggested that flow pathways in fractured-porous rocks can be conceptualized as a network composed of highly compliant fractures (soft hydraulic units) connected with less compliant matrix pores (stiff hydraulic units). At relatively low effective stress, wide fractures and large-aperture channels accommodate most deformation. Their rapid closure and geometric rearrangement lead to a steep reduction in flow capacity. As effective stress increases further, the dominant fracture pathways become increasingly restricted, and the remaining flow is progressively carried by smaller pores and stiff contact areas. Consequently, additional stress increments cause smaller permeability changes, and the curve transitions to a gentler decay regime. This interpretation is consistent with the theoretical analysis of Zimmerman and Bodvarsson [

43], who showed that the transmissivity of a single fracture decreases approximately with the cube of its mechanical aperture, revealing the microphysical origin of the macroscopic nonlinear stress sensitivity observed in this study.

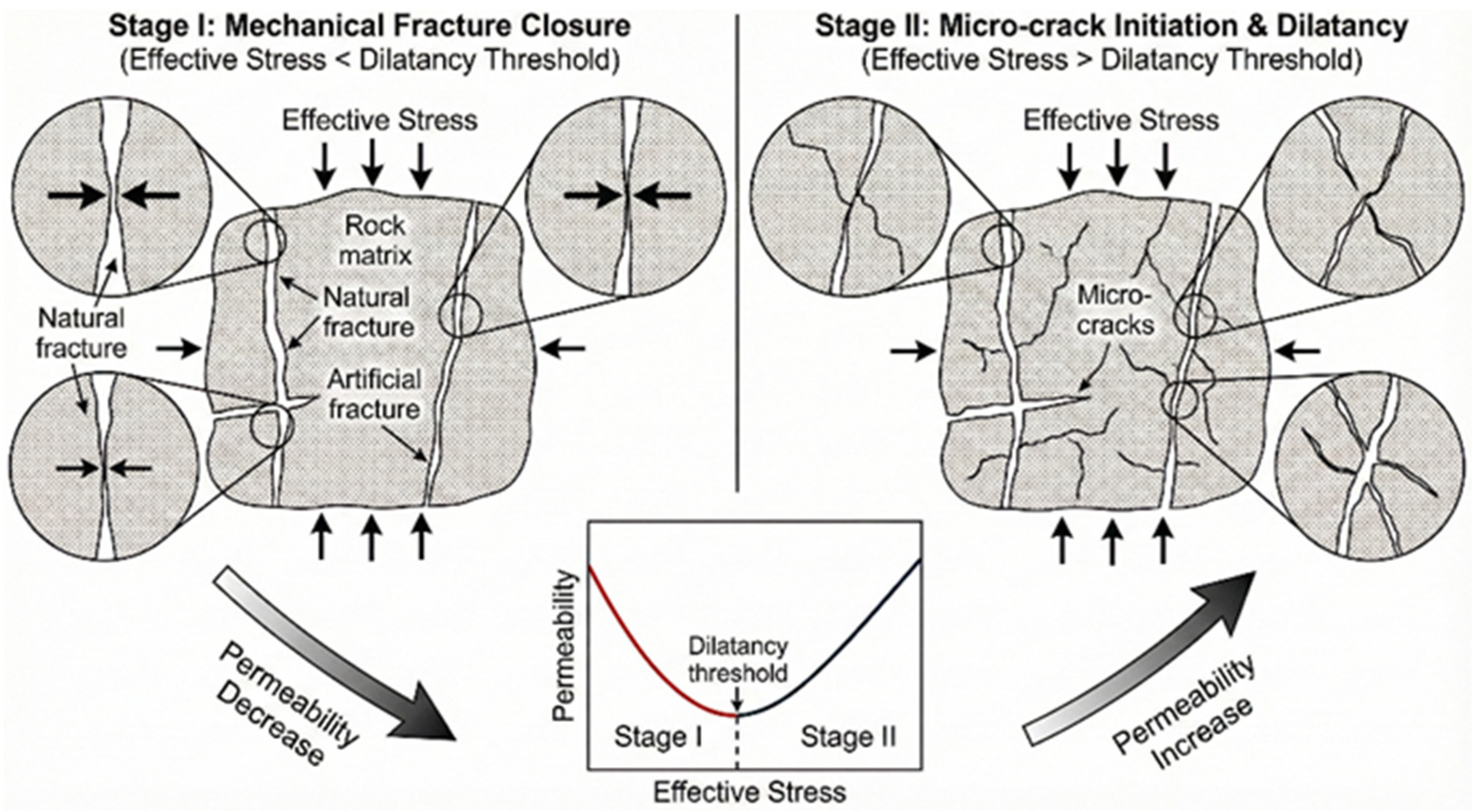

Building on this interpretation, a conceptual model is proposed to describe permeability evolution along a broader effective-stress path (

Figure 11). Two competing stages can be distinguished:

Stage I (mechanical compaction zone): When the effective stress has not yet reached the dilatancy threshold of the rock, the dominant mechanism is the mechanical closure of pre-existing fractures and pores. Macroscopically, permeability decreases monotonically and rapidly with increasing effective stress. The stress range covered by the present experiments falls within this stage.

Stage II (damage-induced dilatancy zone): If the effective stress continues to increase beyond the rock’s dilatancy threshold, micro-crack initiation and propagation are triggered. As experimentally demonstrated by Zoback and Byerlee [

53], microcrack dilatancy in the vicinity of the failure stress can cause a substantial increase in permeability, potentially exceeding initial values by several times, due to the formation of new flow channels. While our current data reside strictly within the mechanical compaction regime (Stage I), this inclusion of Stage II provides a comprehensive roadmap for reservoir behavior under extreme stress loading.

This model captures the entire nonlinear competitive evolution from “mechanical fracture closure” to “micro-crack initiation and dilatancy” and provides a theoretical framework for understanding reservoir behavior under more extreme loading conditions.

5.2. Temperature Sensitivity of Permeability Under Effective-Stress Regulation and Full-Path Conceptual Model

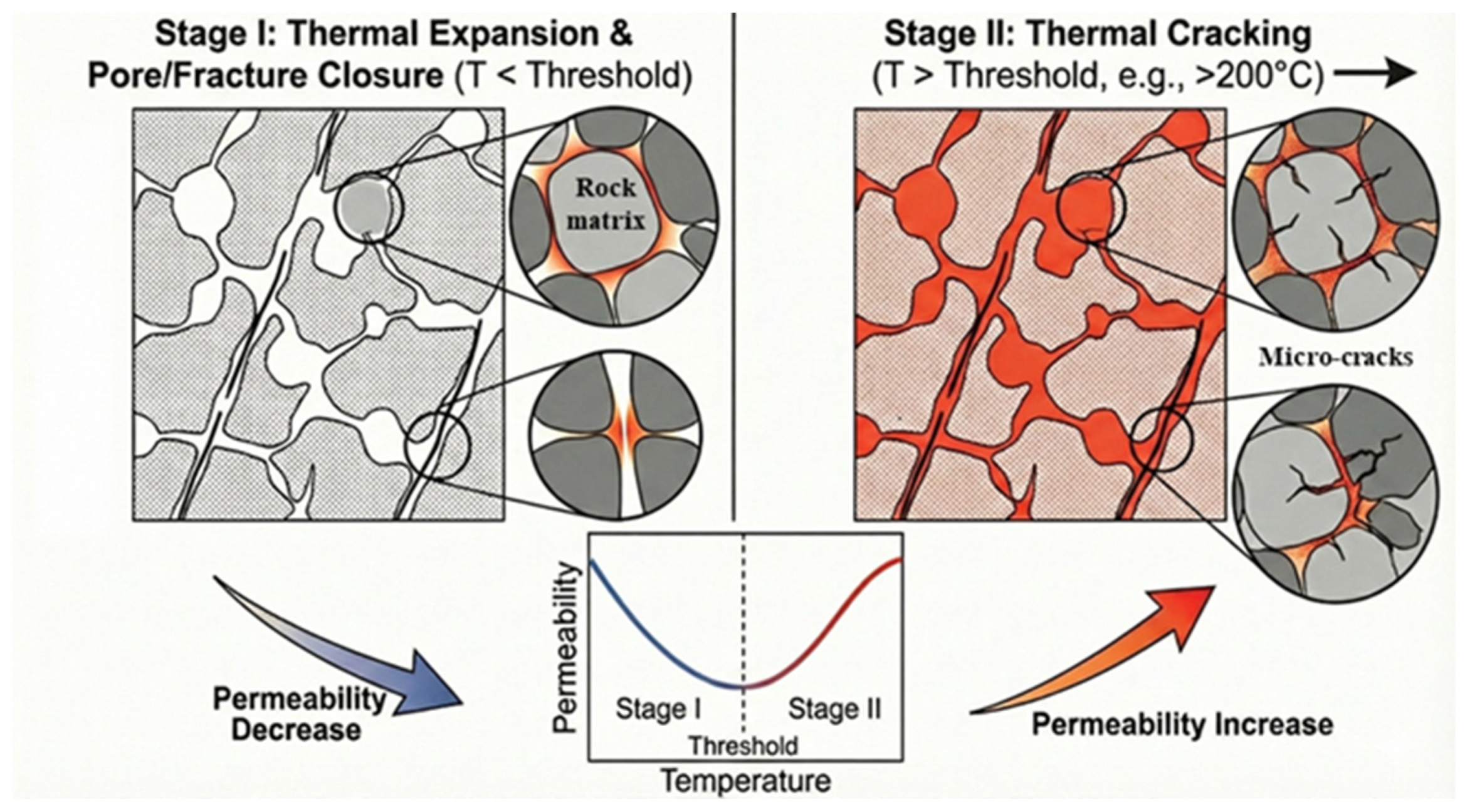

From a mechanistic perspective, the maximum temperature in this study is 80 °C, which is well below the threshold for extensive thermal cracking commonly reported in heating-induced fracturing experiments (typically 200–300 °C) [

22,

54]. Therefore, within 20–80 °C, the observed permeability reduction is mainly attributed to thermoelastic deformation of the rock skeleton and microstructural rearrangement driven by mismatched thermal expansion among mineral constituents. When pre-existing fractures are not fully closed, heating tends to impose additional compression on relatively wide fracture segments, whereas the geometric adjustment of pore throats and smaller fractures is comparatively limited; as a result, the effective flow channels shrink without generating new fracture surfaces. Consistent behaviors have been reported in temperature-stress-permeability experiments on sandstones and granites, where permeability commonly decreases slowly with temperature at low to intermediate temperatures and increases sharply only after pervasive thermal cracking develops at higher temperatures [

23,

49,

54,

55]. This indicates that the present experiments primarily capture the stage dominated by thermoelastic expansion-compression rather than thermal cracking.

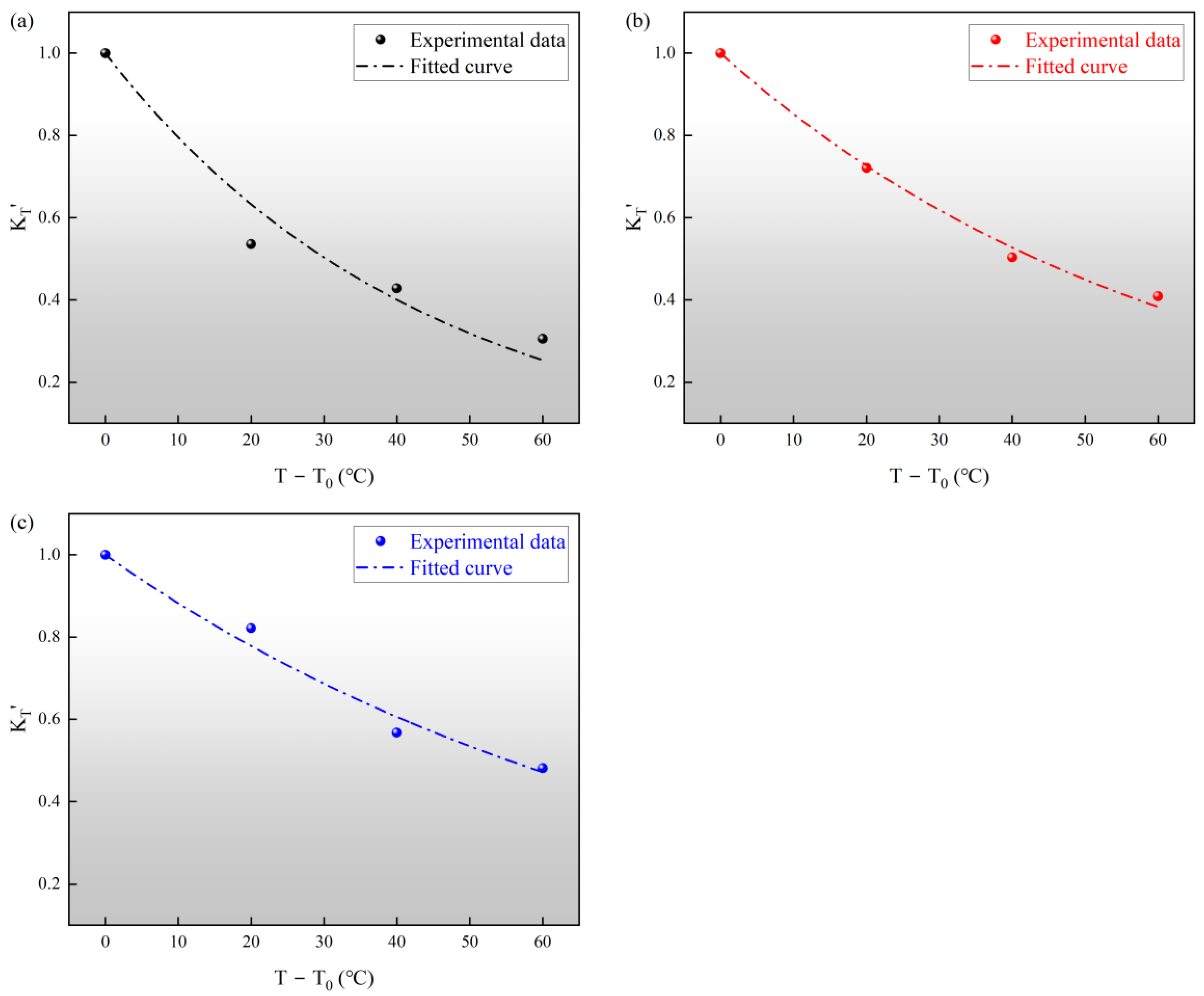

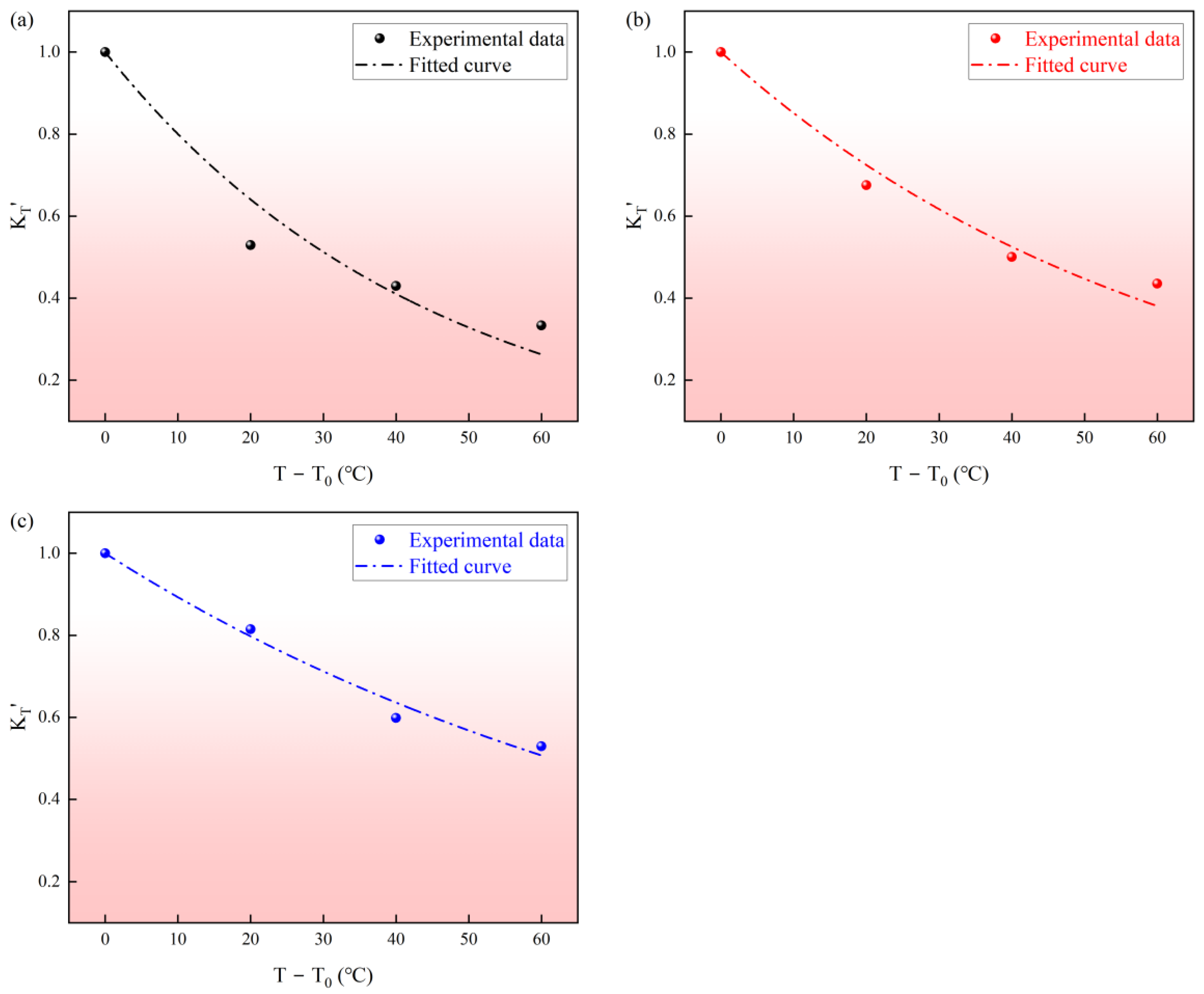

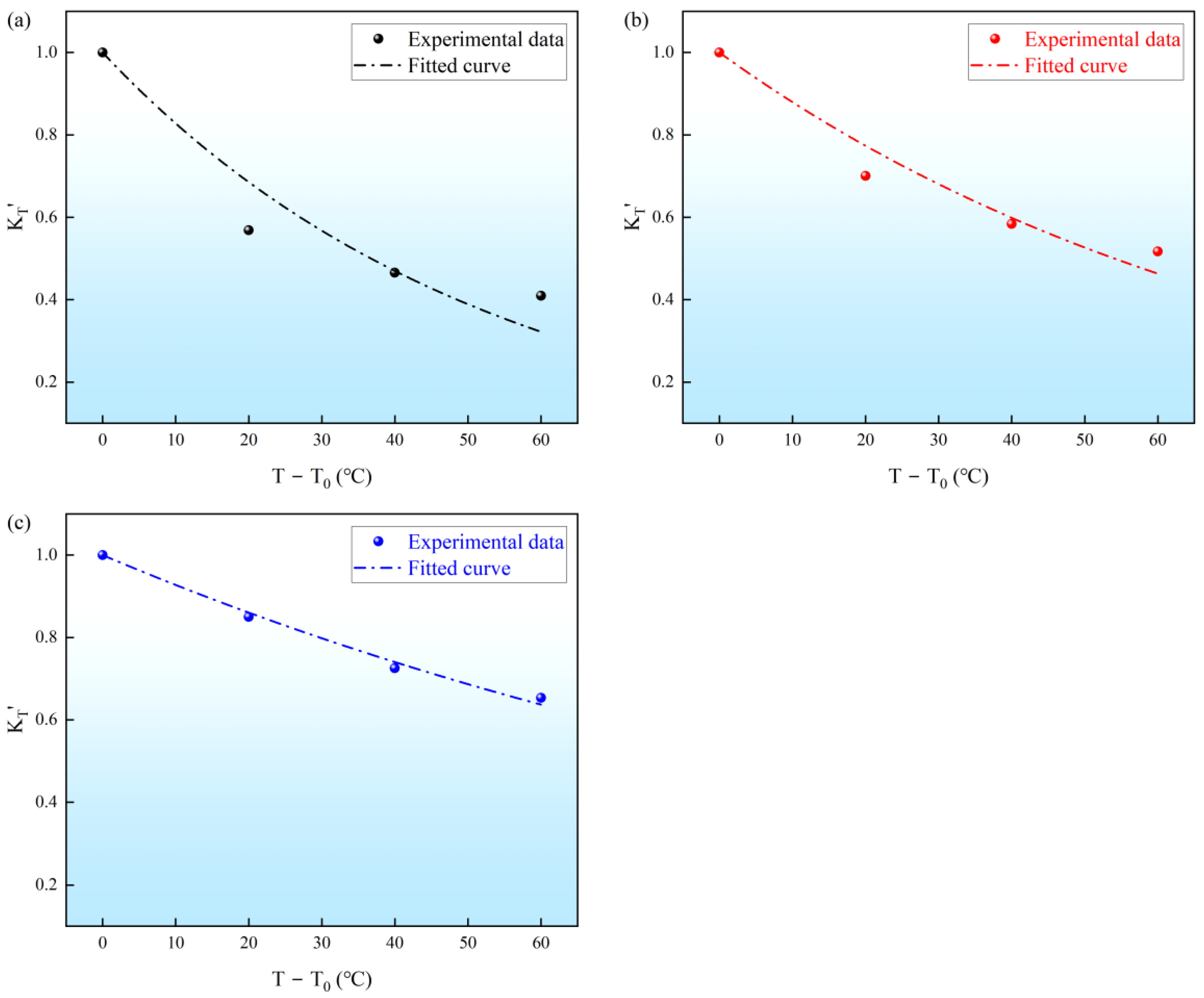

As shown in

Figure 6b–d, the temperature-caused permeability reduction is stronger at low effective stress and becomes progressively weaker at higher effective stress. For example, at

= 15 MPa, heating from 20 to 80 °C reduces permeability by roughly 60% for the North, Middle, and South cores, whereas at

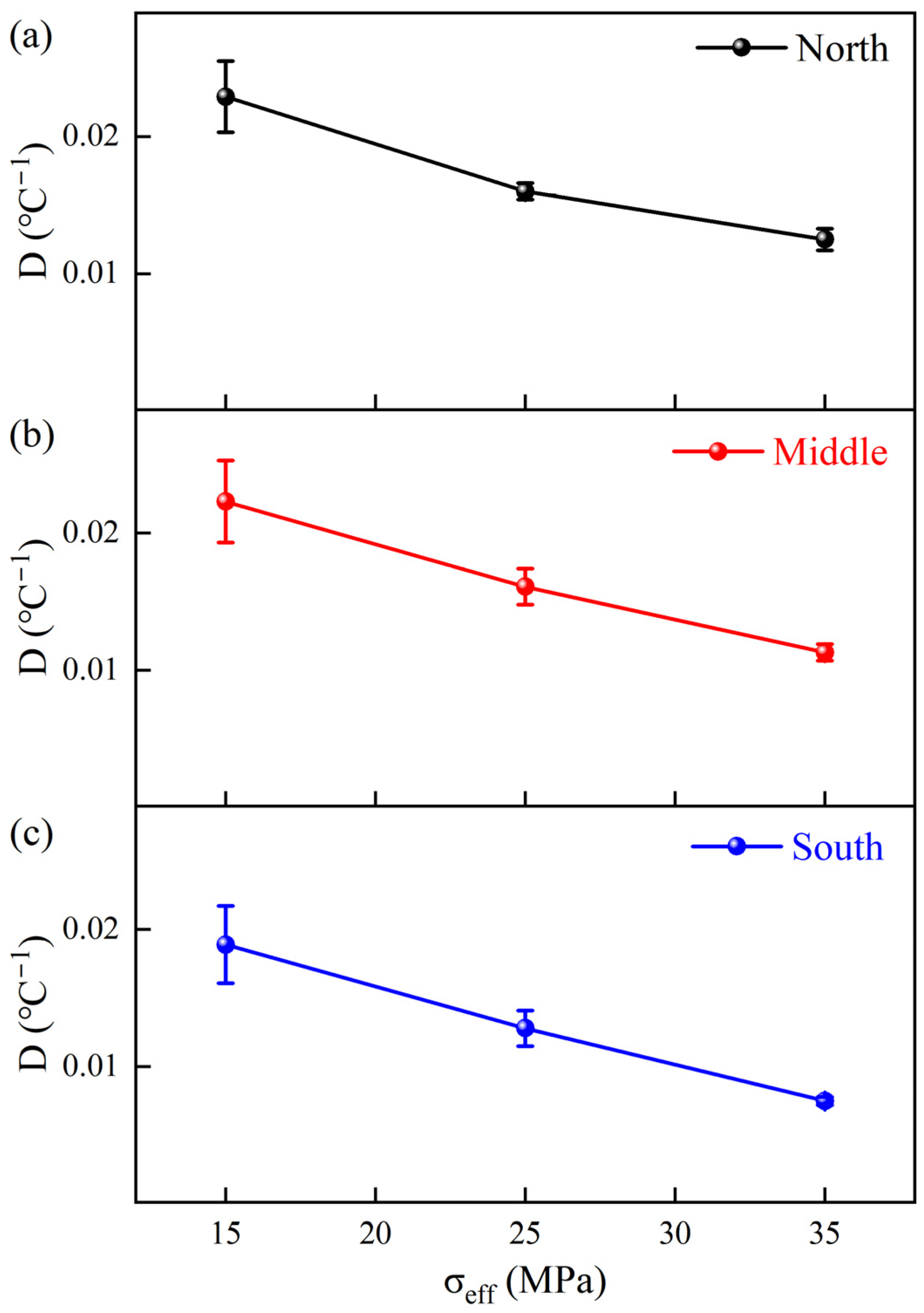

= 35 MPa the reduction is only about 30%. The experimental results provide a clear quantitative link between mechanical confinement and the attenuation of temperature sensitivity. Specifically, as shown in

Table 6 and

Figure 12, the temperature-related decay parameter

D drops by approximately 45.4% to 60.3% across the three specimens as the effective stress increases from 15 to 35 MPa. This systematic reduction in

D quantifies the passivation effect: at 15 MPa, the unclosed and compliant fractures maximize the permeability response to thermoelastic expansion, leading to higher sensitivity. However, as the effective stress triples to 35 MPa, the mechanical pre-closure of these primary conduits, which accounts for an initial 55–60% permeability loss (

Section 3.2), leaves a stiffer skeleton dominated by less-compressible matrix pores. This transition from fracture-dominated to matrix-dominated flow significantly weakens the capacity of mineral expansion to further restrict the seepage pathways, thereby numerically reducing the temperature sensitivity of the bulk rock. A comparable “passivation” of temperature sensitivity at higher effective stresses has also been reported for Beishan granite and several Chinese sandstones [

23,

55].

Based on the experimental results and rock thermophysical theory, we propose a full path mechanistic model for permeability evolution under temperature loading (

Figure 13). The model comprises two competing stages.

Stage I (thermal expansion induced permeability reduction zone): Within the operational temperature conditions of this study (20–80 °C), permeability decreases mainly because matrix minerals undergo thermoelastic expansion. Owing to mismatched thermal expansion among mineral constituents and the confinement imposed by external stresses, the expanding grains progressively encroach on pre-existing pore and fracture space, narrowing effective flow paths, especially relatively wide fractures. This mechanism provides a microphysical explanation for the exponential type permeability decay with increasing temperature observed here, and it represents the dominant response for XGS-UGS operating conditions.

Stage II (thermal cracking induced permeability enhancement zone): If temperature continues to rise beyond the thermal cracking threshold (typically > 200 °C) [

22,

54], thermally induced stresses may exceed intergranular cohesive strength, triggering intergranular microcrack initiation and the propagation of pre-existing fractures [

49,

54,

55]. According to the study on carbonates by Yang et al. [

56], increasing temperature leads to the progressive development of internal micro-fractures and a decrease in the elastic modulus. This real-time thermal cracking can enhance network connectivity and potentially reverse the permeability reduction trend. Although the temperatures in this study (20–80 °C) remain within the Stage I closure regime, the model reflects the well-documented thermo-mechanical evolution of carbonate reservoirs under higher thermal loads.

5.3. Limitations

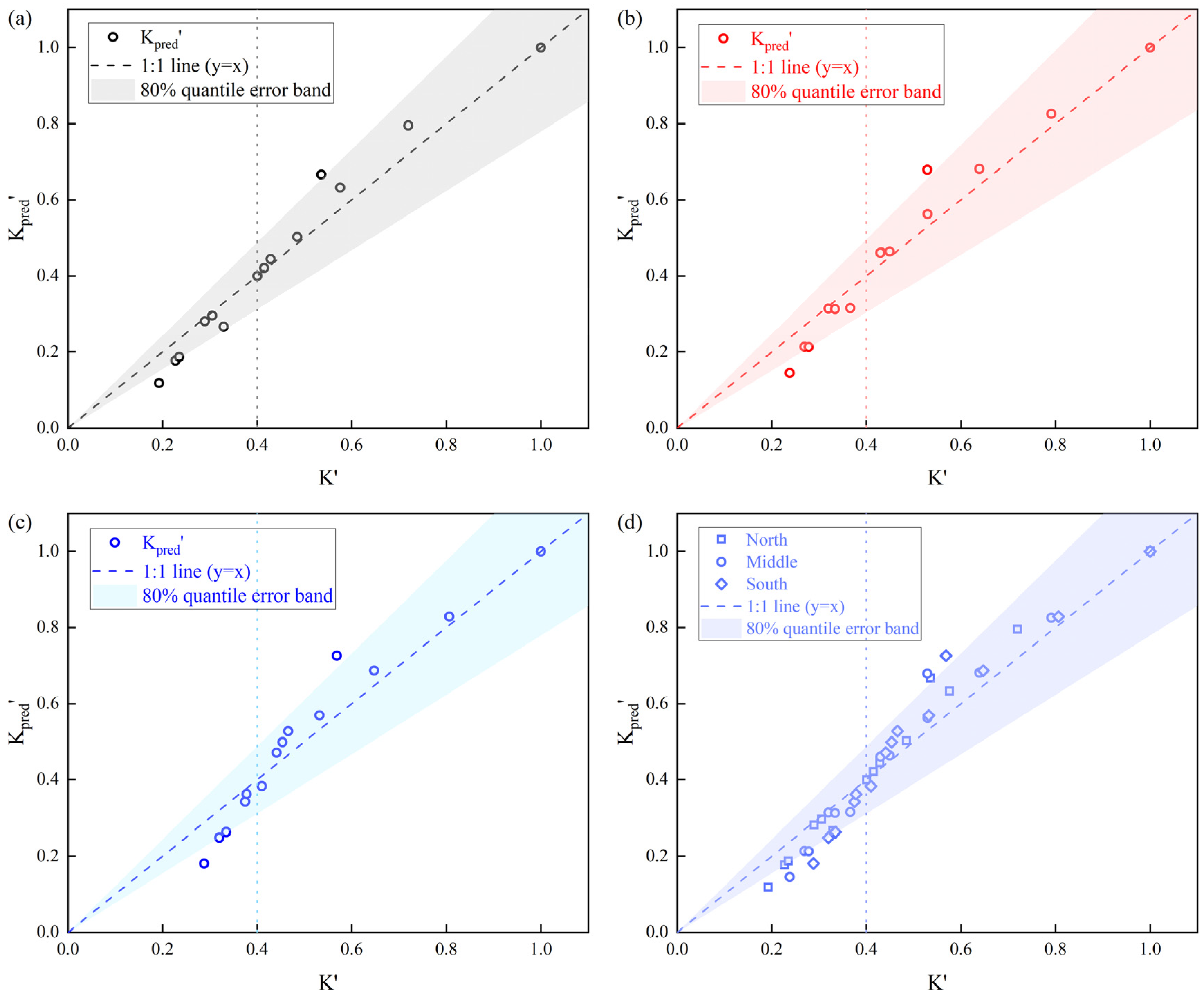

The 1:1 comparison between modeled and measured values, together with the 80% error band, are presented in

Figure 14, which indicates a systematic bias of the model: in the range

= 0–0.4 (usually corresponding to high temperatures and high effective stresses), most predicted values fall below the 1:1 line (slight underestimation), whereas in the range

= 0.4–1.0 (corresponding to low temperatures and low effective stresses), the model tends to overestimate permeability. This suggests that the actual temperature-stress coupling does not strictly follow a single exponential law with constant parameters, but exhibits piecewise nonlinearity: at low temperatures and low effective stresses, fractures are only partially closed and highly compliant; as temperature and effective stress increase, most fractures become nearly closed, additional load is mainly borne by matrix pores, and permeability changes become less pronounced. Therefore, an exponential model with constant

and

cannot fully capture the “initially steep then gradually gentle” curve shape. To further mitigate this systematic bias, future model development could benefit from adopting a piecewise parameterization or a stress-dependent formulation (e.g.,

and

). Such an approach would allow the decay parameters to evolve with the mechanical state of the rock: using higher sensitivity values in the low-stress regime to represent compliant fracture closure and lower values at high stresses to reflect the dominance of stiffer matrix pores. By explicitly accounting for the varying stiffness of the hydraulic units, such refinements could effectively reduce the current overestimation at high normalized permeability values and the underestimation at low values. In addition, Equation (9) assumes separability and does not include higher-order coupling terms; at higher temperatures and larger stresses, or in scenarios involving pronounced dissolution-precipitation and thermally induced fracture development [

57], a separable exponential form may be insufficient to describe strongly nonlinear coupling. With broader experimental data covering wider conditions and controlling factors, more flexible constitutive forms incorporating explicit cross terms could be developed to further refine and generalize the present exponential model. While more complex constitutive forms incorporating explicit cross-terms could potentially reduce residuals further, the current separable model provides a robust balance between mathematical simplicity and predictive accuracy. The consistency shown in the 1:1 comparison (

Figure 14) confirms that for fractured-porous carbonates in XGS-UGS, the independent parameterization of

C and

D is sufficient to reproduce the overall permeability trends across diverse temperature and stress conditions.

Another limitation is the reliance on macroscopic seepage measurements to infer micro-scale deformation processes. While the current flow-based results accurately quantify the hydraulic aperture response, which is essential for evaluating UGS injectivity and deliverability, they do not provide direct visual evidence of the internal geometric evolution. High-resolution micro-CT imaging would be invaluable for visualizing localized fracture closure, asperity damage, and thermally induced micro-cracking under loading. However, performing high-resolution in-situ scans at the investigated moderate temperatures and high stresses (80 °C; 35 MPa) remains a significant technical challenge. Moreover, ex-situ measurements may introduce stress-release artifacts that alter the fracture contact state. Consequently, microstructural changes are currently absorbed into the fitted exponential parameters rather than being parameterized explicitly. Future research incorporating specialized in-situ CT scanning systems will be prioritized to provide more rigorous geometric validation for the proposed thermo-mechanical coupling mechanisms.

Furthermore, the use of a single throughgoing artificial fracture to represent the flow path (

Section 2.1) introduces certain scale-dependent simplifications. While this approach ensures experimental repeatability and allows for clear quantification of thermo-mechanical coupling mechanisms, it simplifies the multi-scale nature of natural fracture networks. In natural reservoirs, fractures exhibit diverse orientations relative to the core axis, varying surface roughness, and heterogeneous mineral infillings (e.g., calcite or clay). These features not only define the initial seepage capacity but also significantly influence the local mechanical stiffness and thermal expansion response of the rock skeleton. Additionally, natural fractured specimens are often susceptible to structural damage during the high-precision machining process, making it technically challenging to prepare high-quality samples that meet strict laboratory standards. Furthermore, while the axial orientation of the artificial fractures maximizes the initial seepage capacity of the core plugs, it does not account for the tortuosity and connectivity losses inherent in multi-scale fracture networks. Consequently, when extrapolating these findings to field-scale simulations, the proposed model should be viewed as a fundamental characterization of the ‘hydraulic unit’ response, which must be coupled with reservoir-scale geological models to account for the structural complexity and network-scale amplification of thermo-mechanical effects. Despite these simplifications, the proposed exponential parameters provide a consistent baseline for characterizing the response of primary seepage conduits in the XGS-UGS, serving as a critical input for upscale multiphysics simulations.

The transition from a single laboratory-scale fracture to a complex reservoir-scale network can be achieved through the equivalent permeability () concept. In this framework, the laboratory-derived parameters C and D serve as the fundamental constitutive response for the individual hydraulic conduits. When integrated into Discrete Fracture Network (DFN) or equivalent continuum models, the macroscopic permeability of a reservoir grid block can be expressed as an assembly of these responsive units. As the effective stress and temperature evolve during UGS operations, the aperture of each fracture within the network follows the calibrated exponential decay, collectively driving the evolution of the field-scale equivalent permeability. However, it is important to note that network-scale connectivity and the cooperative deformation of fractured-vuggy clusters may introduce additional nonlinearities. Therefore, reservoir-scale simulations should utilize these laboratory results as a calibrated baseline while accounting for broader statistical variations in the coefficients to address the impact of complex heterogeneity.

The sensitivity parameters C and D are intrinsically linked to the mechanical state of the rock skeleton. In actual UGS facilities, gas injection increases pore pressure and reduces effective stress, potentially enhancing the reactivity of compliant fractures to both mechanical loading and thermal expansion. If the pore-pressure term in Equation (2) is neglected under high-pressure injection conditions, the model would likely underestimate the rate of permeability recovery. Therefore, for engineering implementation, the exponential model (Equation (9)) should be coupled with a dynamic effective stress calculation that explicitly accounts for localized pore pressure variations.

It is also worth noting that while apparent gas permeability was used without Klinkenberg correction, the identified sensitivity trends remain robust. In the low-mD range of XGS-UGS carbonates, the magnitude of permeability decay caused by fracture closure and mineral thermal expansion far outweighs potential slip-flow deviations. This ensures that the derived exponential parameters (C and D) accurately reflect the relative seepage response of the reservoir skeleton to operational fluctuations.

Another limitation of the current study is the use of monotonic loading paths to calibrate the exponential parameters

C and

D. While these parameters successfully quantify the sensitivity of the reservoir skeleton to initial stress and temperature perturbations, actual UGS operations involve high-frequency cycles of gas injection and withdrawal. Previous studies have indicated that multi-cycle effective stress perturbations can cause irreversible structural damage to the pore-fracture network, leading to permeability hysteresis where the unloading path deviates from the loading path. Such hysteresis often leads to cumulative permeability loss as fracture asperities undergo non-elastic deformation or mechanical fatigue over time. Therefore, the values of

C and

D reported here (

Table 7) specifically represent the loading-path behavior. While they provide a robust upper-bound estimate for permeability decay during initial reservoir adjustment, they may not fully capture the long-term rock fatigue or the partial recovery of flow channels under cyclic conditions. Future research incorporating long-term cyclic testing is needed to extend the exponential model into a full-cycle constitutive relation for UGS performance prediction.

Finally, it is essential to acknowledge the indicative nature of the derived exponential parameters. The ranges identified for the stress-related decay parameter C (0.038–0.046 MPa−1) and the temperature-related decay parameter D (0.016–0.020 °C−1) provide a calibrated baseline for the fractured-porous units within the XGS-UGS under the investigated conditions (20–80 °C; 15–35 MPa). These parameters are representative of the coupled thermo-mechanical response of the primary flow conduits; however, reservoir-scale simulations should account for broader statistical variations in these coefficients to fully address the impact of complex heterogeneity on long-term UGS deliverability.

5.4. Engineering Significance

Within the investigated range (20–80 °C and the tested effective-stress levels), the proposed exponential model offers a concise engineering-scale tool to quantify coupled temperature and stress effects and to compare sensitivity among cores or reservoir intervals using fitted parameters ( and ) in a consistent manner. The identified sensitivity provides a mechanistic basis for understanding field-scale permeability fluctuations in UGS facilities. During the gas injection phase, the rising pore pressure reduces effective stress, and the injection of relatively cold gas typically leads to localized cooling near the wellbore. Our experimental results confirm that both of these thermo-mechanical shifts favor the recovery of flow conduits, which is consistent with field observations where reservoir permeability is generally higher during injection than during the production phase. However, the macroscopic impact on well performance is governed by the synergistic coupling of the sensitivity parameters (C and D) and the spatial extent (radius) of the stress and temperature disturbance zones. While extreme permeability variations are primarily concentrated in the near-wellbore region, they act as a dynamic skin factor that dictates the Injectivity Index. Incorporating these localized and cyclic effects into reservoir simulations allows for a more accurate prediction of deliverability evolution and operational optimization over the entire UGS service life, preventing over-optimistic forecasts that fail to account for localized thermo-mechanical seepage restriction.

To illustrate the practical impact of the proposed model on UGS operations, a representative case study was conducted based on the operating parameters of the XGS-UGS. This facility typically operates with pore pressures between 12 and 30 MPa and formation temperatures ranging from 30 to 60 °C. During a withdrawal phase, as the pore pressure decreases from 30 MPa to 12 MPa, the effective stress acting on the rock skeleton increases by approximately 18 MPa. Concurrently, geothermal heat transfer can cause the localized near-wellbore temperature to rise from the injection state (30 °C) to the formation equilibrium state (60 °C). According to the calibrated exponential model and the sensitivity parameters derived in this study (C ≈ 0.042 MPa−1 and D ≈ 0.019 °C−1), this coupled thermo-mechanical loading leads to a localized permeability reduction of approximately 73% within the primary seepage conduits during a single withdrawal cycle. Such a substantial decay acts as a dynamic skin effect that significantly constrains the well’s deliverability index.

From an engineering perspective, the proposed constitutive model can be integrated into reservoir simulators through two primary pathways:

Direct Analytical Embedding: The exponential relation can be implemented as a dynamic multiplier within the simulator’s constitutive subroutines. This allows the solver to update the permeability of each grid block at every time step based on the instantaneous local stress and temperature fields.

Multi-dimensional Lookup Tables: For commercial simulators with restricted constitutive flexibility, the model can generate a 2D lookup table ( vs and ). The simulator then utilizes bilinear interpolation to determine the effective permeability multiplier during predictive calculations.

By accounting for these localized cyclic variations, the proposed model provides a quantitative tool for optimizing injection-production schedules and ensuring the long-term deliverability of fractured-porous carbonate reservoirs.