CFD Analysis of Diesel Pilot Injection for Dual-Fuel Diesel–Hydrogen Engines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Setup

3. Numerical Setup

3.1. Turbulence and Spray Modeling

3.2. Combustion Modeling

3.2.1. Tabulated Well Mixed (TWM)

3.2.2. Representative Interactive Flamelets (RIFs)

3.3. Computational Mesh

3.3.1. Vessel Grid

3.3.2. Engine Grid

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Vessel Simulation: Pilot-Main Strategy

4.2. Engine Simulations

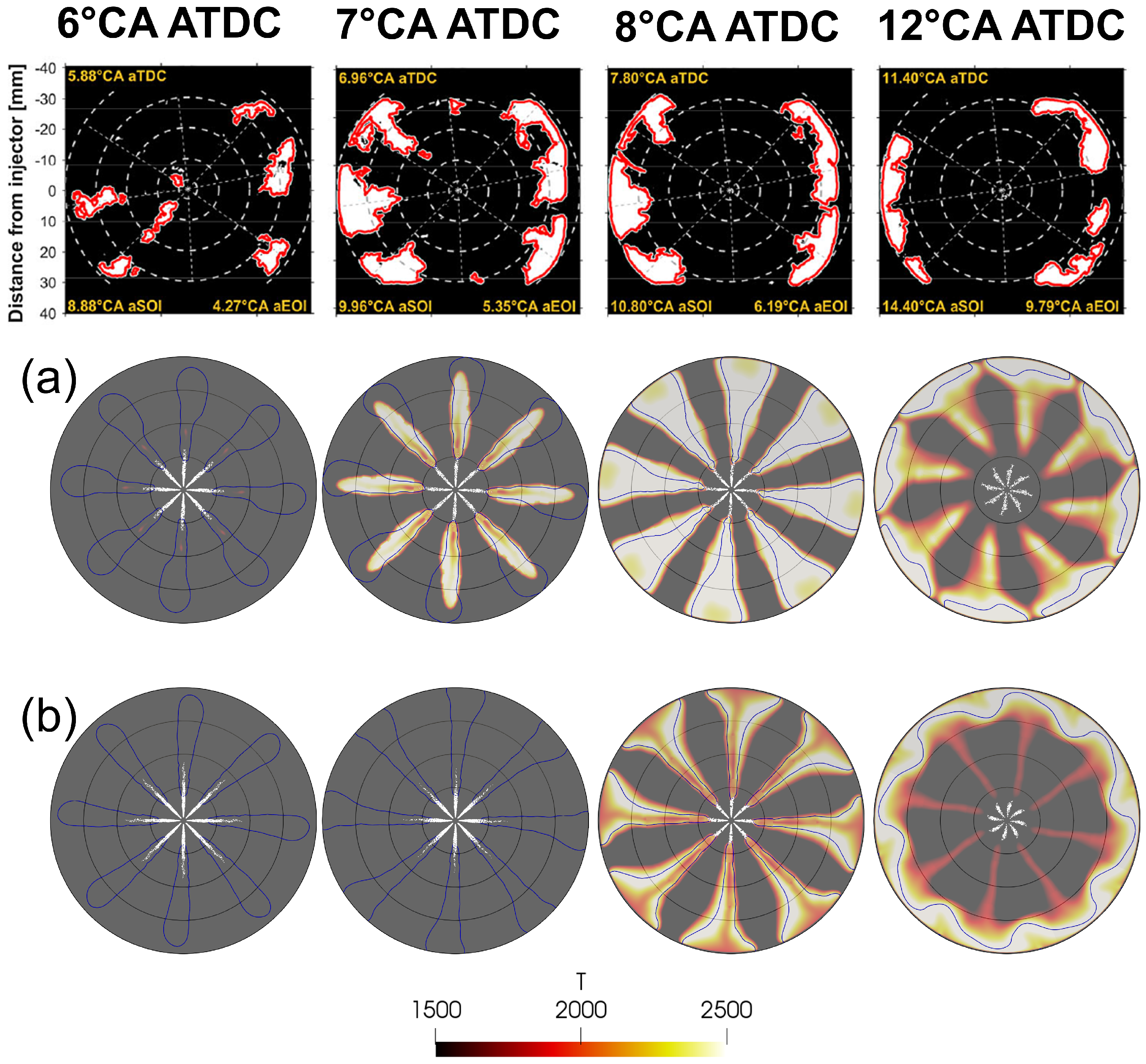

4.2.1. Energy Input Level EIL-100

4.2.2. Energy Input Level EIL-70

4.2.3. Energy Input Level EIL-25

4.2.4. Energy Input Level EIL-10

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHRR | Apparent heat release rate |

| aTDC | After top dead center |

| bTDC | Before top dead center |

| CA | Crank angle |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| CVCC | Constant volume combustion chamber |

| Carbon dioxide | |

| DI | Direct injection |

| EGR | Exhaust gas recirculation |

| EIL | Energy input level |

| EMFC | Eulerian Monte Carlo fields |

| FGM | Flamelet generated manifolds |

| GDI | Gasoline direct injection |

| Hydrogen | |

| ICE | Internal combustion engine |

| IVC | Intake valve closing |

| NOx | Nitrogen oxides |

| Dioxygen | |

| Probability density function | |

| PFI | Port fuel injection |

| PISO | Pressure-implicit with splitting of operators |

| RANS | Reynolds-averaged Navier Stokes equations |

| RIF | Representative Interactive Flamelet |

| SI | Spark ignition |

| SOI | Start of injection |

| TDC | Top dead center |

| TWM | Tabulated well mixed |

| C | Progress variable |

| Number of species | |

| Unburned gas temperature | |

| i-th species mass fraction | |

| Z | Mixture fraction |

| Mixture fraction variance | |

| c | Normalized progress variable |

| Unburned enthalpy | |

| Enthalpy of formation | |

| Density | |

| Scalar dissipation term | |

| Reaction rate |

References

- Prussi, M.; Laveneziana, L.; Testa, L.; Chiaramonti, D. Comparing e-Fuels and Electrification for Decarbonization of Heavy-Duty Transports. Energies 2022, 15, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboa-Espinoza, V.; Segura-Salazar, J.; Hunt, C.; Aitken, D.; Campos, L. Comparative life cycle assessment of battery-electric and diesel underground mining trucks. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 139056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, R.D.; Ogawa, H.; Payri, R.; Fansler, T.; Kokjohn, S.; Moriyoshi, Y.; Agarwal, A.; Arcoumanis, D.; Assanis, D.; Bae, C.; et al. IJER editorial: The future of the internal combustion engine. Int. J. Engine Res. 2020, 21, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Hydrogen Strategy for a Climate-Neutral Europe. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0301 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. Hydrogen Shot. 2021. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-shot (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Volvo Trucks. Volvo to Launch Hydrogen-Powered Trucks. 2024. Available online: https://www.volvotrucks.com/en-en/news-stories/press-releases/2024/may/Volvo-to-launch-hydrogen-powered-trucks.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Cummins, Inc. Cummins Inc. Debuts 15-Liter Hydrogen Engine at ACT Expo. 2023. Available online: https://www.cummins.com/news/releases/2022/05/09/cummins-inc-debuts-15-liter-hydrogen-engine-act-expo (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Liebherr. World Premiere: Liebherr Debuts Crawler Excavator with a Hydrogen Engine. 2022. Available online: https://www.liebherr.com/en-us/n/world-premiere-liebherr-debuts-crawler-excavator-with-a-hydrogen-engine-27129-3782185 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Accardo, A.; Costantino, T.; Malagrinò, G.; Pensato, M.; Spessa, E. Greenhouse Gas Emissions of a Hydrogen Engine for Automotive Application through Life-Cycle Assessment. Energies 2024, 17, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahchian Tabrizi, M.; Cerri, T.; Bonalumi, D.; Lucchini, T.; Brenna, M. Retrofit of Diesel Engines with H2 for Potential Decarbonization of Non-Electrified Railways: Assessment with Lifecycle Analysis and Advanced Numerical Modeling. Energies 2024, 17, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onorati, A.; Payri, R.; Vaglieco, B.; Agarwal, A.; Bae, C.; Bruneaux, G.; Canakci, M.; Gavaises, M.; Günthner, M.; Hasse, C.; et al. The role of hydrogen for future internal combustion engines. Int. J. Engine Res. 2022, 23, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kim, Y.; Byun, C.; Lee, J. Feasibility of compression ignition for hydrogen fueled engine with neat hydrogen-air pre-mixture by using high compression. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrignoli, F.; Pisapia, A.M.; Savioli, T.; Mancaruso, E.; Mattarelli, E.; Rinaldini, C.A. Exploring Hydrogen–Diesel Dual Fuel Combustion in a Light-Duty Engine: A Numerical Investigation. Energies 2024, 17, 5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramognino, F.; Sforza, L.; D’Errico, G.; Gomez-Soriano, J.; Onorati, A.; Novella, R. CFD Modelling of Hydrogen-Fueled SI Engines for Light-Duty Applications. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Engines & Vehicles, Capri, Italy, 10–14 September 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.Z.; Sun, B.G.; Luo, Q.H. Experimental investigation of the achieving methods and the working characteristics of a near-zero NOx emission turbocharged direct-injection hydrogen engine. Fuel 2022, 319, 123746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srna, A.; von Rotz, B.; Herrmann, K.; Boulouchos, K.; Bruneaux, G. Experimental investigation of pilot-fuel combustion in dual-fuel engines, Part 1: Thermodynamic analysis of combustion phenomena. Fuel 2019, 255, 115642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchini, T.; Schirru, A.; Mehl, M.; D’Errico, G.; Rorimpandey, P.; Chan, Q.N.; Kook, S.; Hawkes, E.R. Modeling hydrogen–diesel dual direct injection combustion with FGM and transported PDF. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2024, 40, 105213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhou, D.; Yang, W.; Qian, Y.; Mao, Y.; Lu, X. Investigation on the potential of using carbon-free ammonia in large two-stroke marine engines by dual-fuel combustion strategy. Energy 2023, 263, 125748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, C.; Dinesh, K.R. Numerical modelling of a heavy-duty diesel–hydrogen dual-fuel engine with late high pressure hydrogen direct injection and diesel pilot. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 674–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, C.J. Large-eddy simulations for internal combustion engines—A review. Int. J. Engine Res. 2011, 12, 421–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasse, C. Scale-resolving simulations in engine combustion process design based on a systematic approach for model development. Int. J. Engine Res. 2016, 17, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egüz, U.; Leermakers, N.; Somers, B.; de Goey, P. Modeling of PCCI combustion with FGM tabulated chemistry. Fuel 2014, 118, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barths, H.; Antoni, C.; Peters, N. Three-Dimensional Simulation of Pollutant Formation in a DI Diesel Engine Using Multiple Interactive Flamelets; SAE Technical Paper; Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE): Warrendale, PA, USA, 1998; p. 982459. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, A.G.; Chan, Q.N.; Kook, S. The influence of hydrogen injection timing and energy proportion on flame developments in a dual direct injection optical diesel engine. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2025, 24, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, S.B. An explanation of the turbulent round-jet/plane-jet anomaly. AIAA J. 1978, 16, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, R.D. Modeling Atomization Processes in High Pressure Vaporizing Sprays. At. Spray Technol. 1987, 3, 309–337. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtiniemi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Rawat, R.; Mauss, F. Efficient 3-D CFD Combustion Modeling with Transient Flamelet Models; SAE Technical Paper 2008-01-0957; Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE): Warrendale, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, N. Laminar Flamelet Concepts in Turbulent Combustion. Symp. Combust. 1988, 21, 1231–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Lee, C.F.F. Investigation on soot emissions from diesel-CNG dual-fuel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 9438–9449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsch, H.; Barths, H.; Peters, N. Three Dimensional Modeling of NOx and Soot Formation in DI-Diesel Engines Using Detailed Chemistry Based on the Interactive Flamelet Approach. SAE Trans. 1996, 105, 2010–2024. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, N. Laminar diffusion flamelet models in non-premixed turbulent combustion. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 1984, 10, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchini, T.; Torre, A.D.; D’Errico, G.; Montenegro, G.; Fiocco, M.; Maghbouli, A. Automatic Mesh Generation for CFD Simulations of Direct-Injection Engines; SAE Technical Paper 2015-01-0376; Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE): Warrendale, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Displacement Volume [cc] | 1133 |

| Stroke [mm] | 126 |

| Bore [mm] | 107 |

| Connecting Rod [mm] | 200 |

| Compression Ratio [-] | 17.4 |

| Engine Speed [rpm] | 1200 |

| Swirl Ratio [-] | 2 |

| IVC [CAD] | −175 |

| Piston bowl diameter [mm] | 77.90 |

| Piston bowl depth [mm] | 10.60 |

| Fuel injection setup | |

| Hydrogen | Diesel |

| Modified Bosch HDEV6 spray guided GDI | G4S direct injector (Denso from Kariya, Japan) |

| Protech boost pump | CP4 common rail (Bosch from Gerlingen, Germany) |

| 1 mm single-hole nozzle cap | 8 × mm holes |

| Steady state flow rate: g/s at 350 bar | |

| Optical diagnostic setup | |

| High-speed camera | NOVA S20 (Photron from Tokyo, Japan) |

| Lens | Nikkor 200 mm f/4D (Nikon from Tokyo, Japan) |

| Aperture | f/8 |

| Exposure | 1/frame (16.6 s) |

| Frame rate [kHz] | 60 |

| Frame interval [°CA/frame] | 0.12 |

| Imaging resolution [pixel] | 512 × 512 |

| Pixel resolution [m/pixel] | 156 |

| Neutral density filter | OD 1 (Edmund Optics from Barrington, IL, USA) #65-817) |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Turbulence model | RANS |

| 1.5 | |

| Injection model | Cone injection |

| Discharge coefficient | 0.99 |

| Size distribution | Uniform 120 m |

| Breakup model | KH-RT |

| KH-RT B0 | 0.61 |

| KH-RT B1 | 25 |

| KH-RT | 0.05 |

| Fuel Energy [J] | 1200 | 840 | 300 | 120 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy input level EIL [%] | 100 | 70 | 25 | 10 |

| Injection duration [s] | 775 | 640 | 407 | 284 |

| Injection pressure [bar] | 750 | |||

| Injection timing [°CA aTDC] | −3 | |||

| Engine speed [rpm] | 1200 | |||

| Coolant temperature [K] | 363 | |||

| Intake temperature [K] | 303 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

D’Errico, G.; Gianetti, G.G.; Lucchini, T.; Heaton, A.G.; Kook, S. CFD Analysis of Diesel Pilot Injection for Dual-Fuel Diesel–Hydrogen Engines. Energies 2026, 19, 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020380

D’Errico G, Gianetti GG, Lucchini T, Heaton AG, Kook S. CFD Analysis of Diesel Pilot Injection for Dual-Fuel Diesel–Hydrogen Engines. Energies. 2026; 19(2):380. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020380

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Errico, Gianluca, Giovanni Gaetano Gianetti, Tommaso Lucchini, Alastar Gordon Heaton, and Sanghoon Kook. 2026. "CFD Analysis of Diesel Pilot Injection for Dual-Fuel Diesel–Hydrogen Engines" Energies 19, no. 2: 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020380

APA StyleD’Errico, G., Gianetti, G. G., Lucchini, T., Heaton, A. G., & Kook, S. (2026). CFD Analysis of Diesel Pilot Injection for Dual-Fuel Diesel–Hydrogen Engines. Energies, 19(2), 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020380