1. Introduction

The current regulatory and industrial framework is strongly oriented toward ecological transition and the decarbonization of the transportation sector. The European Green Deal and the “Fit for 55” package set ambitious targets for reducing CO

2 emissions related to transport. In this context, hydrogen produced from renewable sources (commonly referred to as

green hydrogen) is emerging as one of the most promising options for replacing conventional fossil-based fuels [

1,

2].

However, its use in internal combustion engines (ICEs) presents several technical, performance, and operational safety challenges, primarily due to its low density, its high reactivity [

3], and some material compatibility issues, particularly with respect to hydrogen embrittlement [

1]. Although several studies have demonstrated that hydrogen can be effectively used as a fuel in internal combustion engines [

1,

4,

5,

6,

7], a critical issue is its high tendency to knock when operating near stoichiometric conditions. This phenomenon can severely compromise system reliability and rapidly cause engine failure. To mitigate the risk of dangerous knock events in spark-ignition engines fueled with hydrogen, the use of lean mixtures (λ ≥ 1.25) has proven effective [

6,

8]. Furthermore, the adoption of leaner mixtures (λ = 1.9), also allows for the combustion of hydrogen without significant NOx formation [

8].

The use of lean mixtures, however, leads to a marked reduction in engine specific performance [

8], thereby decreasing the competitiveness of internal combustion engines compared to other propulsion systems. In this perspective, the use of synthetic hydrocarbons (e-fuels) is considered a potential pathway toward transport decarbonization that does not compromise engine performance. These fuels are characterized by properties like those of gasoline, such as a similar knock resistance [

9]. This, however, entails the risk of severe knock phenomena under full-load conditions, which are typically avoided by employing retarded combustion phasing and very rich mixtures (λ = 0.80). Such operating conditions lead to high CO and HC emissions, which are only poorly reduced by the exhaust after-treatment system due to its low conversion efficiency under rich mixture conditions.

One of the most promising solutions to address knock-related issues that may arise when adopting stoichiometric mixtures with hydrogen or e-fuel combustion is water injection, which can be implemented either directly, into the cylinder (Direct Water Injection, DWI), or indirectly, into the intake ducts (Port Water Injection, PWI) [

10,

11].

Port water injection allows for improved water vaporization due to the longer time available for mixing with air; the evaporation process, during which the latent heat of vaporization is absorbed from the intake air, leads to a significant reduction in the in-cylinder temperature, thus avoiding knock events or reducing their intensity. Port water injection can be performed at low injection pressures and has the advantage of easy integration and implementation in modern engines; these advantages have recently attracted interest from leading manufacturers in the automotive sector, such as Bosch. Reference paper [

12] reports the implementation of a continuous (port) water injection system on a spark-ignition CFR engine, with the aim to quantify both the NOx emission reduction and the knock resistance increment obtainable on refinery intermediate products characterized by low Research Octane Number (RON); the main reported results showed that, with water/fuel ratio from 0.5 to 1.5, the fuel RON was increased from 70 to 95, while NOx emissions were reduced by more than 50%. The effectiveness of port water injection in suppressing knocking has also been confirmed by numerical studies, such as reference [

13], where a gasoline direct-injection (GDI) engine was employed, demonstrating that increasing the water-to-fuel ratio leads to lower in-cylinder temperatures and, consequently, a reduced knock tendency.

In reference paper [

14] the authors conducted an experimental study on the effect, of PWI on the combustion and emissions of a 2.0 L four-cylinder Miller cycle, fueled with standard gasoline, with engine speeds ranging from 2500 to 5000 rpm; knock intensity was evaluated in terms of Maximum Amplitude of in-cylinder Pressure Oscillation (MAPO); without water injection, MAPO values between 1 bar and 2.5 bar were observed, whereas, with water injection, knocking was suppressed and MAPO values decreased to approximately 0.5 bar, thus confirming the beneficial effects of PWI in cancelling knock phenomena. However, the study reported in reference paper [

14] does not investigate operating conditions characterized by high number of knocking cycles, such as those tested in the present work, and the tested fuel was not a low-octane fuel comparable to hydrogen [

1,

2].

Reference paper [

15] reports a study involving a 550 cm

3 single-cylinder direct-injection gasoline engine operating at 1500 rpm, fueled by two different gasolines (RON92 and RON98), tested under incipient knock conditions. The results again showed that port water injection effectively mitigates knock tendency of the engine, although the study was limited only to mild knock conditions. In reference paper [

16], an experimental and numerical CFD study is carried out on a turbocharged engine with the aim of evaluating the fuel consumption improvements obtainable thanks to the knock suppression effect produced by port water injection. The study focuses on knock-limited spark advance operation (i.e., incipient knock condition), regarding only a low-reactive fuel (standard gasoline), and a single water injection pressure.

Finally, in review papers [

10,

11], which analyze and reports extensive information on water injection in internal combustion engines, the advantages and drawbacks of the two technologies, PWI and DWI, are compared. In particular, it is noted that direct water injection:

Similar conclusions are drawn in reference paper [

17], in which the potential of water injection is tested on HCCI engines, and in [

21], which reports an experimental study on the application of water injection in a Wankel engine.

Apart from the configuration adopted, PWI or DWI, water injection always provides additional significant benefits in terms of nitrogen oxide (NOx) emission reduction. The mechanism which allows water injection to reduce intensity of knock phenomena is, in fact, mainly related to the cooling effect produced by the evaporation of the injected water within the intake duct and/or inside the cylinder; the resulting temperature decrease also leads to reduced dissociation of nitrogen and oxygen, and, consequently, to a lower formation of thermal nitrogen oxides. For instance, as reported in [

12], the injection of water, up to 150% with respect to fuel mass, resulted in NOx reductions of up to 50%. Similarly, ref. [

15] reports experimentally measured NOx reductions up to 43% achieved through PWI in a single-cylinder GDI engine. Numerical studies on turbocharged SI engines [

16] also indicate NOx reductions in the range of 40–50% due to water injection, values consistent with experimental results published in [

22] for a hydrogen-fueled SI engine. It is worth mentioning that the combustion of hydrocarbon fuels may cause the formation of prompt NOx, according to a secondary NOx formation mechanism, whose concentration in the exhaust gas becomes significant when fuel concentration in the combustion zone is high, i.e., with rich air–fuel mixtures. Considering that prompt NOx can occur at even lower temperatures than thermal NOx, it is probable that port water injection is less effective against this second formation mechanism.

Based on the reported literature, no studies have quantitatively assessed the effects of water injection under heavy knocking conditions, such as those that may arise from the combustion of hydrogen or e-fuels in stoichiometric proportion with air, or in turbocharged engines. These considerations induced the authors of the present work to carry out an experimental investigation on the effectiveness of port water injection, both in terms of heavy knocking suppression (i.e., high number of knocking cycles) and in terms of reducing NOx emissions, which represent the only pollutant generated by the combustion of hydrogen, especially under stoichiometric conditions. To evaluate the possible influence of injection pressure [

23], which affects the degree of atomization of the water spray, the experimental tests were repeated for three different injection pressure levels.

The authors opted for port water injection, not only for practical reasons related to the implementation on the selected engine, but also because, given the current state of research, port water injection represents the most suitable solution, given the numerous and non-negligible issues associated with direct injection, as previously discussed. Conversely, port water injection offers several advantages in terms of ease of implementation and operational reliability. One of its main benefits lies in the greater time available for water evaporation, which starts in the intake duct. This condition enables a well-timed evaporation of the water injected, drastically reducing the presence of liquid water in the cylinder [

10,

13,

24]. It is worth mentioning that the scope of the present investigation is limited to ascertaining the knock suppression and the NOx reduction obtained by port water injection, without measuring any engine performance or efficiency variations. The water evaporation in the intake duct may have effects on both engine efficiency (reduced temperatures) and engine performance (reduced volumetric efficiency) and should be further explored.

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the present study, compared to previously published papers.

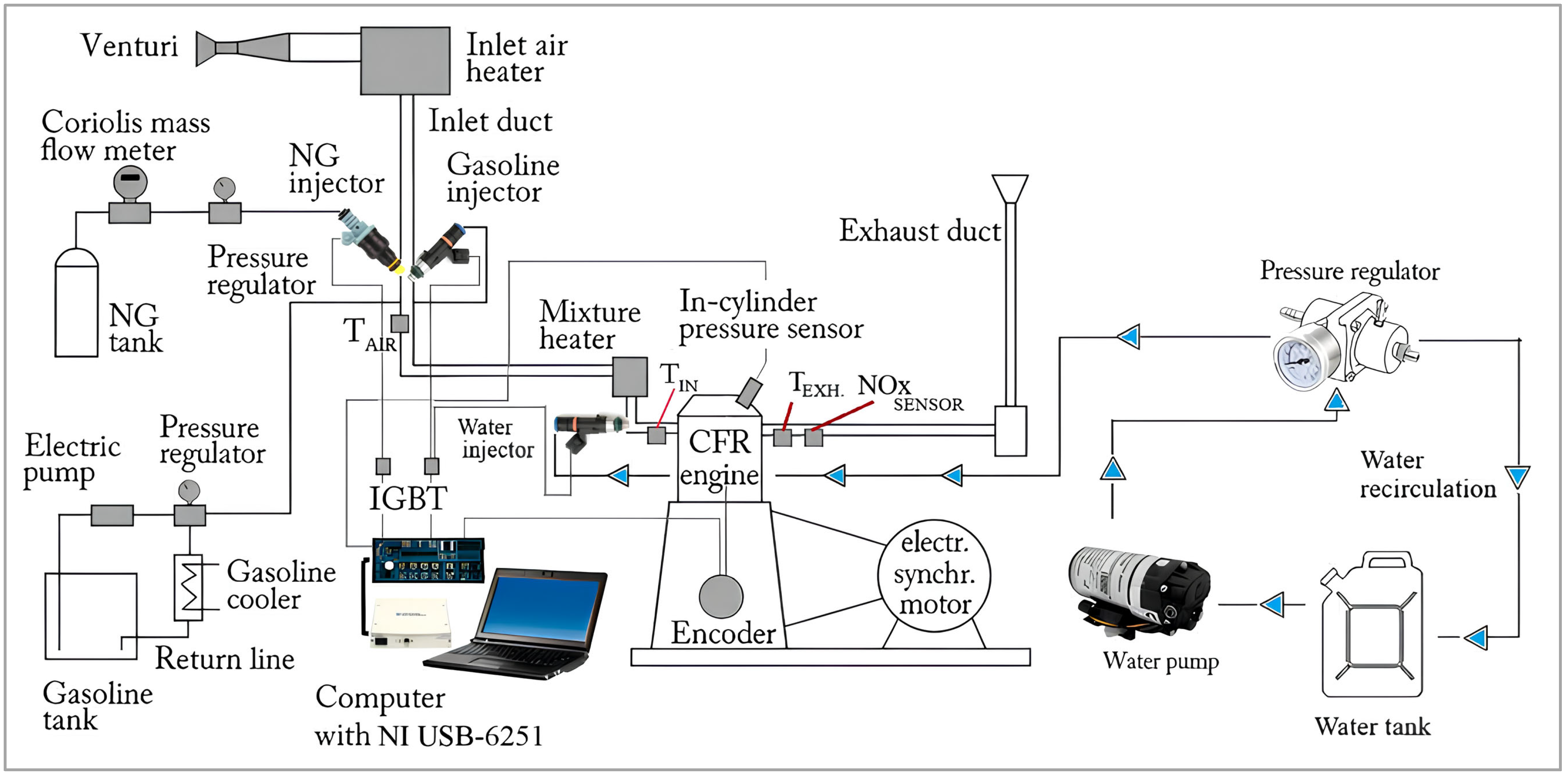

2. Experimental Setup

To assess the effectiveness of port water injection in the suppression of heavy knocking phenomena, tests were carried out on a CFR F1/F2 engine, the standard engine used for octane number rating (engine specifications are reported in

Table 2). This engine is specifically designed to operate continuously under severe knock conditions. Owing to its distinctive characteristics [

25,

26], it allows inducing knock events that would be unacceptable in series production engines, thereby enabling an in-depth evaluation of the potential benefits achievable through port water injection.

In order to reproduce conditions as close as possible to those of hydrogen combustion, the tests were carried out employing a Primary Reference Fuel with an octane number of 60 (PRF60), consisting of 60% iso-octane and 40% n-heptane by volume, which has been shown to adequately represent the knocking tendency of hydrogen [

27]; since the knock phenomenon is related to the temperature reached by the end-gas, a similar knock resistance also means a similar reaction to temperatures, which means that the in-cylinder temperatures realized in the test are similar to the temperatures required to produce the same knocking behavior with hydrogen.

The CFR engine used in the tests is a single-cylinder, four-stroke spark-ignition engine with two overhead valves. It features a disc-shaped combustion chamber and allows adjustment of the compression ratio over the wide range 4.5 ÷ 16, thanks to a specific design that allows vertical movements of the cylinder head with respect to the piston [

8,

25].

The intake air temperature

TAIR and the air–fuel mixture temperature

TMIX were measured using K-type thermocouples and modulated using electric resistors controlled by Omega CN4116 PID automatic controllers. To allow for the electronic injection control of both gaseous and liquid fuels, the CFR engine used in the tests was equipped with a double-injection system. The injectors dedicated to the two fuel types were installed in the intake manifold immediately downstream of the heating resistor that regulates the intake air temperature

TAIR (see

Figure 1).

The original ignition system was updated with an electronic circuit to allow digital control of combustion phase. To enable port water injection, the CFR engine used in the tests

Figure 2 was equipped with a third injection system, positioning a dedicated injector in the intake duct immediately upstream of the intake valve. The main specifications of the engine used in the tests are reported in

Table 2.

For the PWI system installed on the CFR engine employed in the present work, a Bosch EV14CL injector, identical to the one employed for the liquid fuel injection, was selected; this injector can be operated with injection pressures up to 8 bar (gauge) and is characterized by a conical spray pattern; this feature was exploited through a precise installation of the injector, which was oriented to direct the spray toward the intake valve opening, thereby preventing unnecessary water accumulation in the intake duct walls.

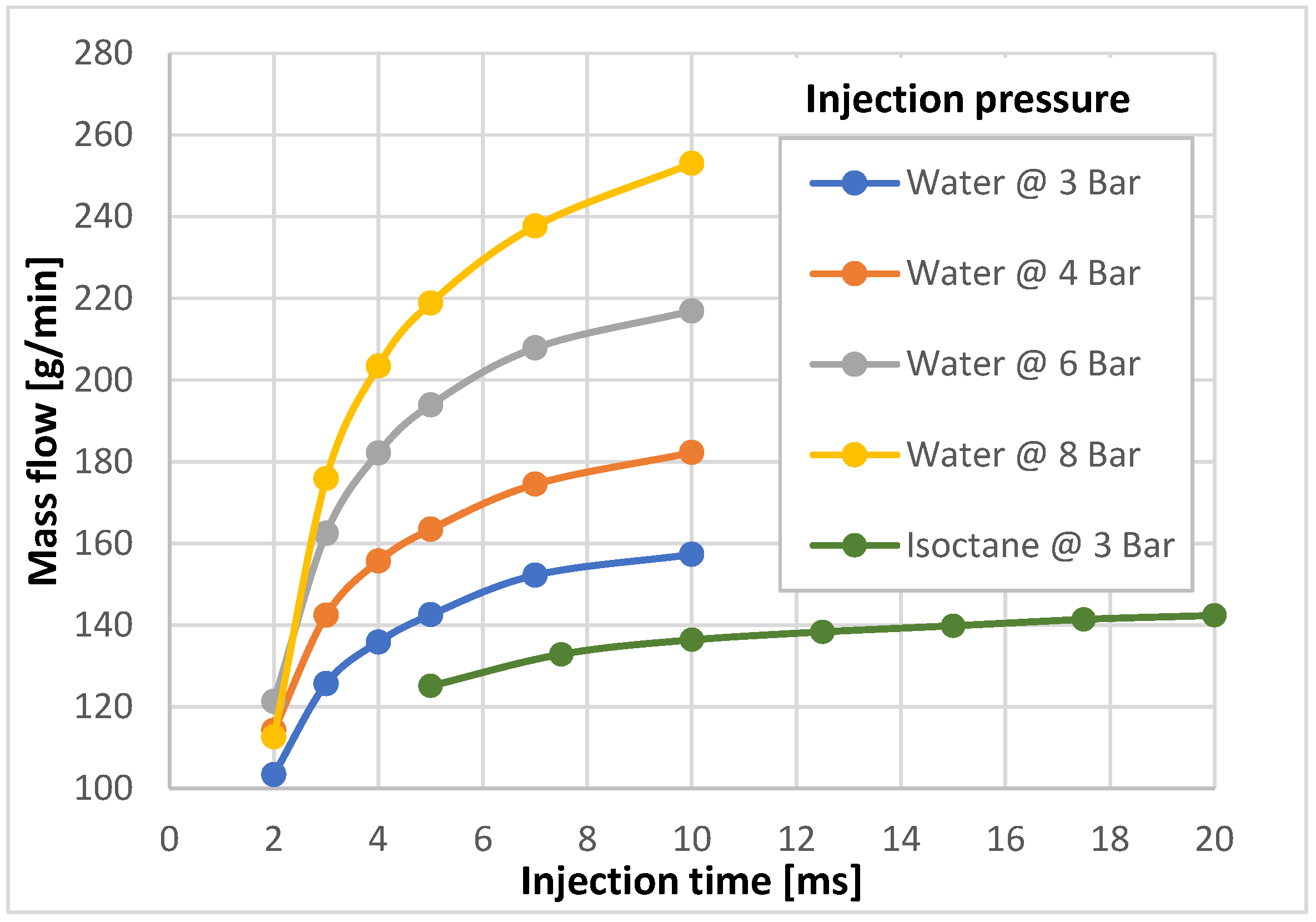

The injection pressure was modulated by means of an adjustable pressure regulator, whose nominal operating range is 1–10 bar. The pump used for water injection is a diaphragm-type pump capable of operating at pressures up to 10 bar. The system also includes a 5-L tank, used to store the demineralized water used for injection. The flow rate of both fuels and injected water was determined using injector calibration maps (see

Figure 3), which were previously obtained experimentally through the gravimetric method, employing an Orma EL-1000 laboratory balance.

The flow rate delivered by the fuel injector was calibrated using iso-octane (the main component of PRF60) with an injection pressure of 3 bar (gauge); the calibration map for the water injector was instead obtained with pressures of 3, 4, 6, and 8 bar (gauge). No calibration of the injector was performed with n-heptane, since its density is very close to that of iso-octane.

Figure 3 shows the experimentally measured flow curves for water injection and iso-octane injection. The liquid fuel was injected using a gasoline pump and a fixed-pressure regulator (3 bar gauge). The control of the injection systems was performed by means of virtual instruments (VI) developed in LabVIEW environment; in particular, a closed-loop control was performed on the fuel injection using the feedback of the measured air–fuel ratio.

3. Data Acquisition and Instrumentation

The data acquisition and the control of fuel and water injections were performed using a National Instruments USB-6251 multifunction board, connected through a BNC2120 Connector Block to a personal computer and programmed in LabVIEW.

The in-cylinder pressure signal was acquired using a Kistler piezoelectric sensor connected to an AVL microIFEM Piezo 4P4x charge amplifier, with a sampling frequency of 160 kHz. The precise determination of top dead center (TDC) position was performed using a Kistler 2629B capacitive sensor, whose accuracy is 0.1 crank angle degrees (CADs). An incremental optical encoder mounted on the engine crankshaft was used to generate the single pulse per revolution employed to trigger both data acquisition and pulse generation for injections and ignition. IGBT transistors, activated by digital pulses generated by the NI USB-6251 board, were employed to this purpose.

The use of a 200 MHz 4-channel digital oscilloscope (Siglent SDS 2204X HD) was fundamental for checking the correct phasing among the cylinder pressure signal, the trigger signal, and digital pulses for fuel and water injections. The measure of the exhaust gas NOx was carried out by means of an ECM NOx 5210 laboratory sampling system, equipped with a probe measuring both NOx concentration and oxygen (O2) content, hence allowing the verification of the engine operating air–fuel ratio.

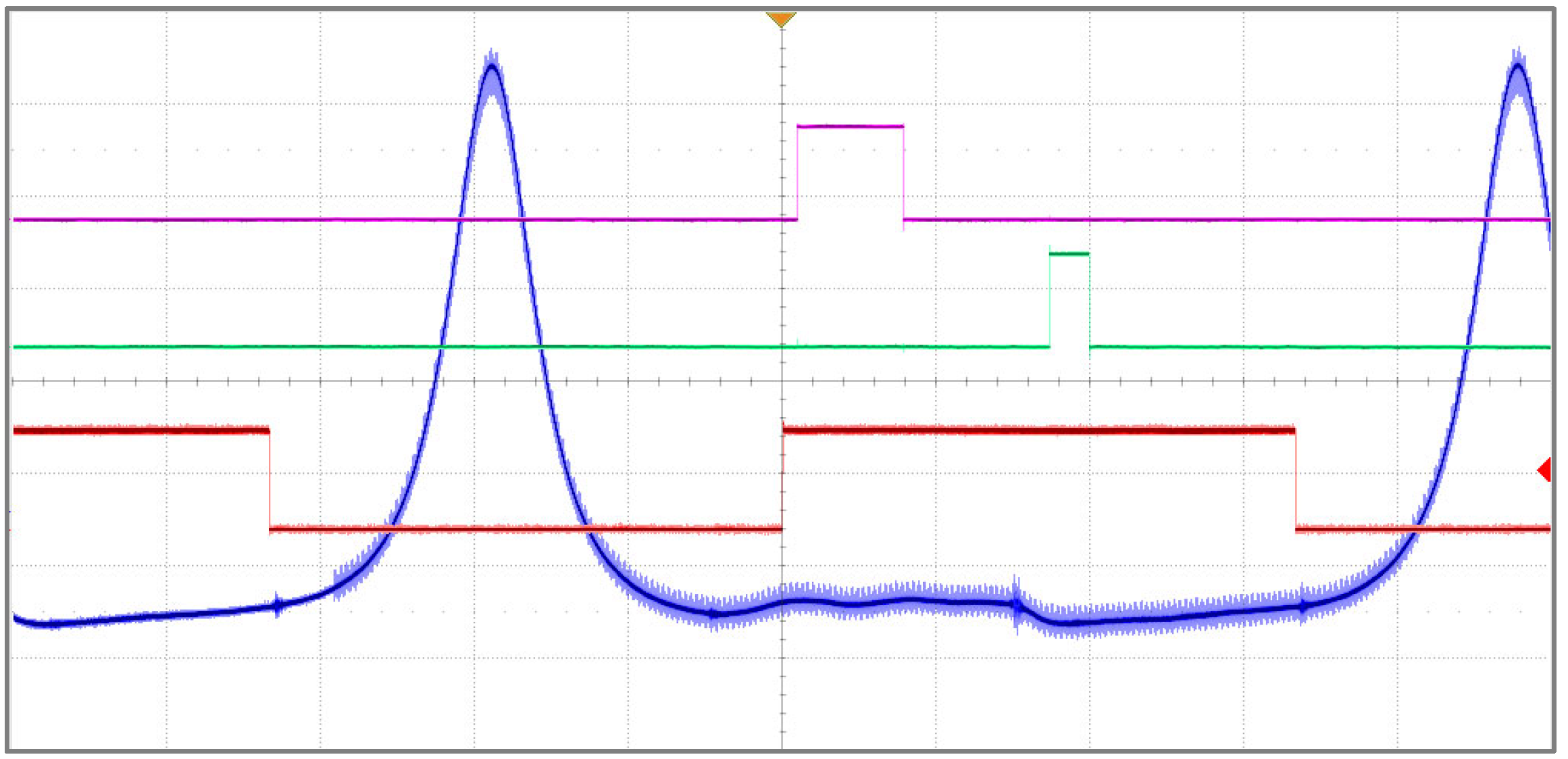

The

Figure 4 shows a screen captured from the 4-channel digital oscilloscope during the experiments, clearly distinguishing the cylinder pressure signal (blue), the trigger signal (red), the fuel injection pulse (purple), and the water injection pulse (green). The water injection pulse was phased in time with the starting of the intake phase.

4. Test Methods

The operating conditions adopted in the experimental tests carried out are resumed in

Table 2. The CFR engine is not endowed with a throttle valve and is connected to an electric motor which maintains a constant speed of rotation, under both motored and fired conditions (acting hence as motor or brake). This implies that CFR engine load and speed of rotation cannot be changed, and that the torque produced by the engine cannot be measured, thus forbidding correlating the water injection with engine performance variations. It is worth mentioning, however, that slow speed of rotation and full load represent the most critical conditions under which to test the knock suppression effect of port water injection (that is, the scope of the present work), since they induce heavy knocking (more time for autoignition to occur and slow flame front propagation) and are less favorable for the evaporation of the water injected (less turbulence).

As shown in

Table 3, water injection was performed at 3 different pressure levels (3, 5, and 7 bar gauge). For each injection pressure, the amount of water injected was varied from zero (no water injection) up to 40% with respect to fuel mass, in steps of 10%. The condition without water injection corresponded to the maximum knock intensity, while, with water injection, knock intensity decreased in proportion to the amount of water injected.

For each operating condition, 100 pressure cycles were sampled, together with all the relevant engine parameters. Each individual pressure signal was filtered using a 2nd-order band-pass Butterworth filter (3 to 20 kHz) to remove undesired low- and high-frequency components not related to the knock phenomenon.

Figure 5 shows a sampled cylinder pressure trace and a filtered signal.

The filtered signal was then truncated, selecting a 50 CAD window starting from the knock event. Knock intensity (KI) was evaluated for each individual engine cycle as the root mean square (

RMS) value calculated on the windowed filtered signal, as follows:

where the vector

X, whose dimension is

N, contains the whole windowed filtered pressure signal.

The knock intensity calculated for each individual pressure cycle was compared with the knock intensity measured in the complete absence of knock events (referred to as the base knock intensity, KIB), a condition achieved by properly reducing spark advance. A generic pressure cycle was then considered a knocking cycle when the ratio between its knock intensity (KI) and the base intensity exceeded a predetermined threshold value. The number of cycles classified as knocking within the matrix of 100 sampled cycles defines the percentage of knocking cycles. The higher the percentage of knocking cycles, the heavier the knocking operating condition. In series production engines, the condition of incipient knock (i.e., the knock level considered tolerable) corresponds to a percentage of knocking cycles below 10%, whereas a relevant knock level (i.e., requiring immediate intervention such as spark advance reduction) corresponds to 10% to 20% of knocking cycles.

The threshold value was established through proper measurements in the setup phase, employing the amplitude spectrum of the in-cylinder pressure signal (monitored through the LabVIEW virtual instrument developed). The amplitude power spectrum is a powerful tool, which allows revealing the frequency content of the analyzed signal. Under knocking conditions, the CFR in-cylinder pressure signal is characterized by a sharp dominance of the 6 kHz components, which is the CFR knocking frequency [

28,

29]. Starting from a knock-safe condition (whose knock intensity is the KIB), the spark timing was increased until the 6 kHz component was revealed to be sharply and clearly predominant over the entire observed amplitude spectrum (i.e., 3–20 kHz); this condition was considered as a knocking condition, and its knock intensity KI was compared to the base knock intensity, revealing the ratio of 2.5, which was hence assumed as the threshold value to rank a pressure cycle as knocking cycle. As confirmation of this threshold value, in reference paper [

14], a MAPO value exceeding 1 bar was considered the knock limit above which significant knocking occurred, while MAPO values below 0.5 bar were measured in knock-free combustions; the resulting threshold is then around 2. The same conclusion can be drawn from reference paper [

30], where the normalized knock indicator assumes the value of 2 when the knocking condition is reached.

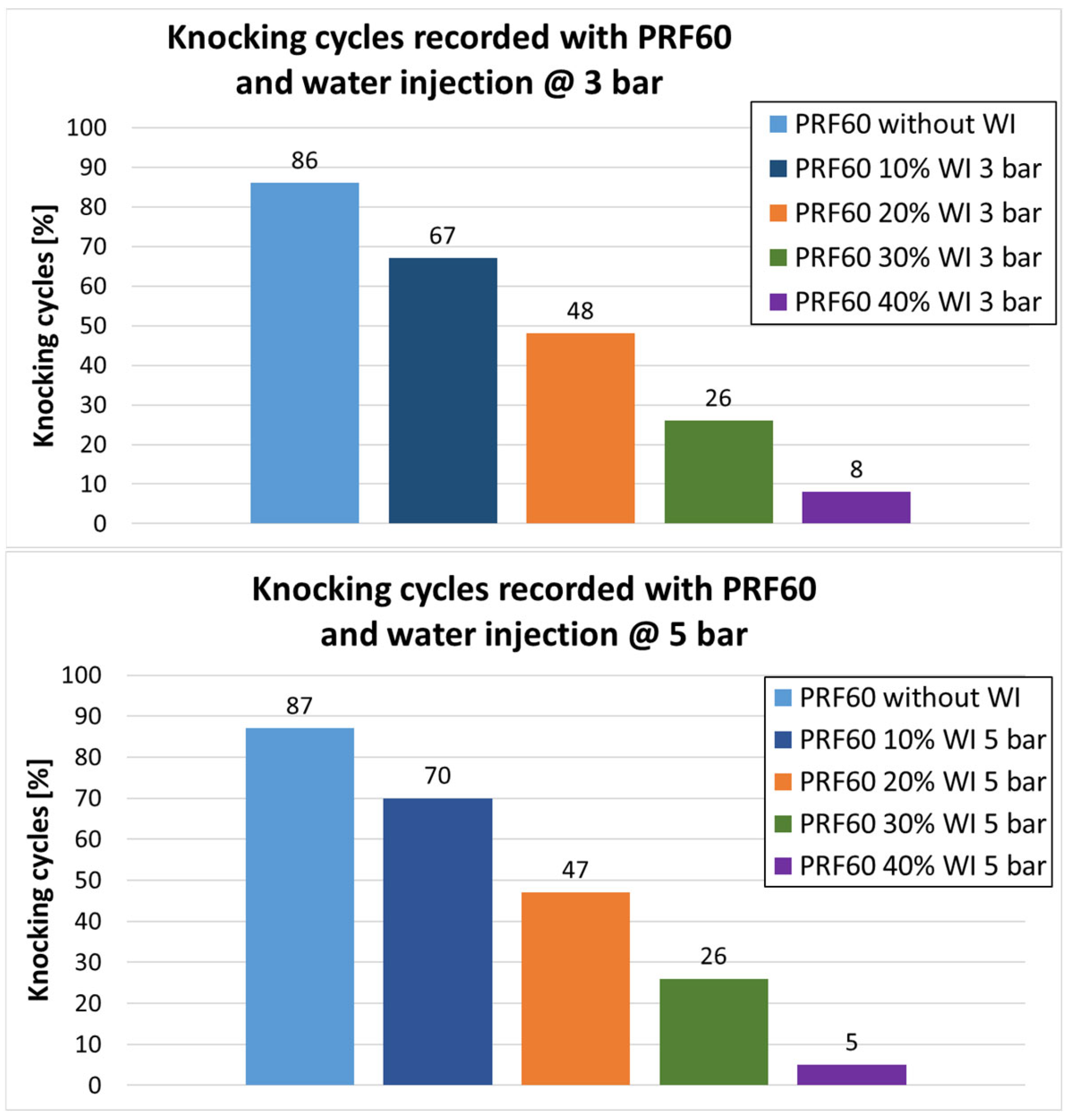

Once the base knock intensity was established (i.e., without knocking), ignition timing was advanced to achieve the heavy knock condition, i.e., a condition characterized by a high number of knocking cycles, approximately between 80% and 90%. Such a condition could not be replicated in production engines without causing serious and irreparable damage. The effect of the water injection was quantified by measuring the percentage of knocking cycles obtained for each amount of water injected. The knock conditions tested in this study are not easy to reproduce unless a properly designed engine is used, and this peculiarity makes the present study particularly relevant in the scientific literature.

5. Results and Discussion

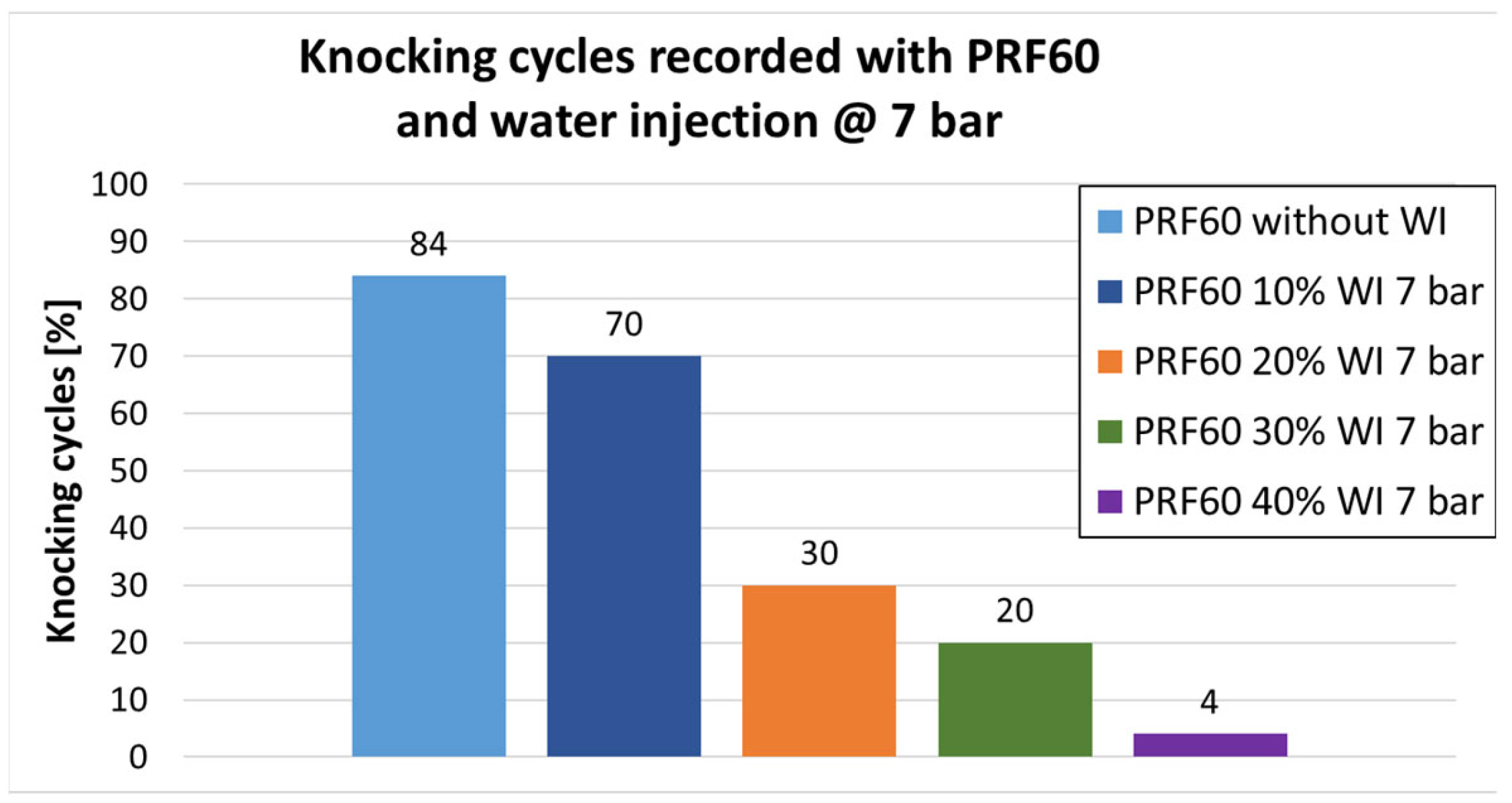

The results of the tests are shown in the graphs of

Figure 6. As observed, in the absence of water injection, percentages of knocking cycles exceeding 80% were recorded. It can also be noted that the knock suppression effect of the first 10% of water injection is approximately the same regardless of the injection pressure. The effects obtained with higher water quantities (20%, 30%, and 40% of fuel mass) appear to be nearly identical at injection pressures of 3 and 5 bar (gauge), while a different result was observed at an injection pressure of 7 bar (gauge). This may be explained by the higher degree of atomization achieved at 7 bar (gauge), which could have improved water evaporation, thus enhancing the cooling effect on the intake charge.

For all the three injection pressure cases, near-complete suppression of heavy knocking was achieved by injecting water quantities equal to 40% of fuel mass. The residual knock events can be considered negligible and could be completely removed with a minimal further increase in the water injected; for example, in the 3 bar gauge test, a linear proportionality allows for estimating that an additional 4% of water would be required to completely reduce knocking cycles to zero. The experimental campaign confirmed the effectiveness of port water injection, showing a progressively decreasing trend in knocking cycles as the amount of injected water increased, regardless of the injection pressure.

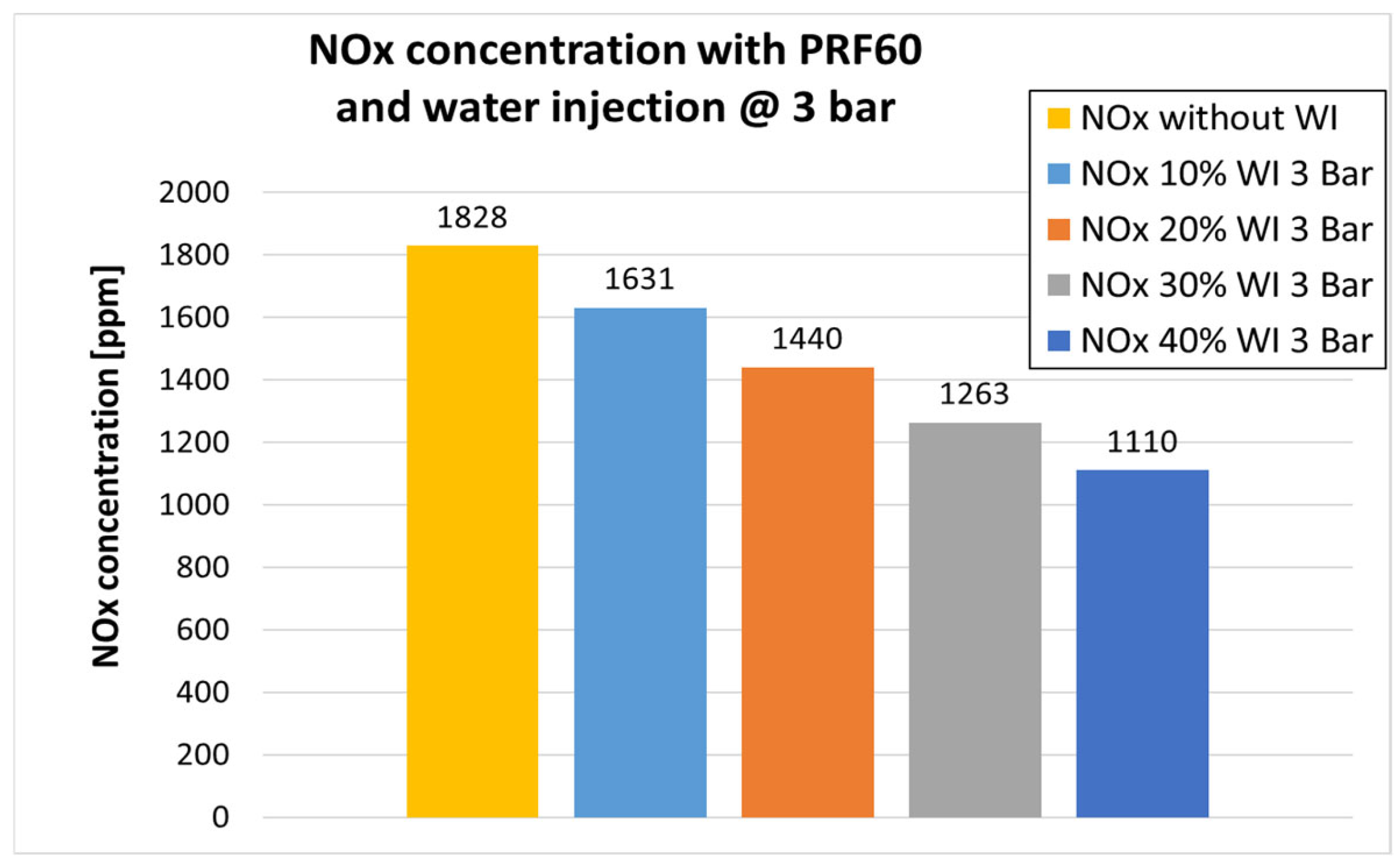

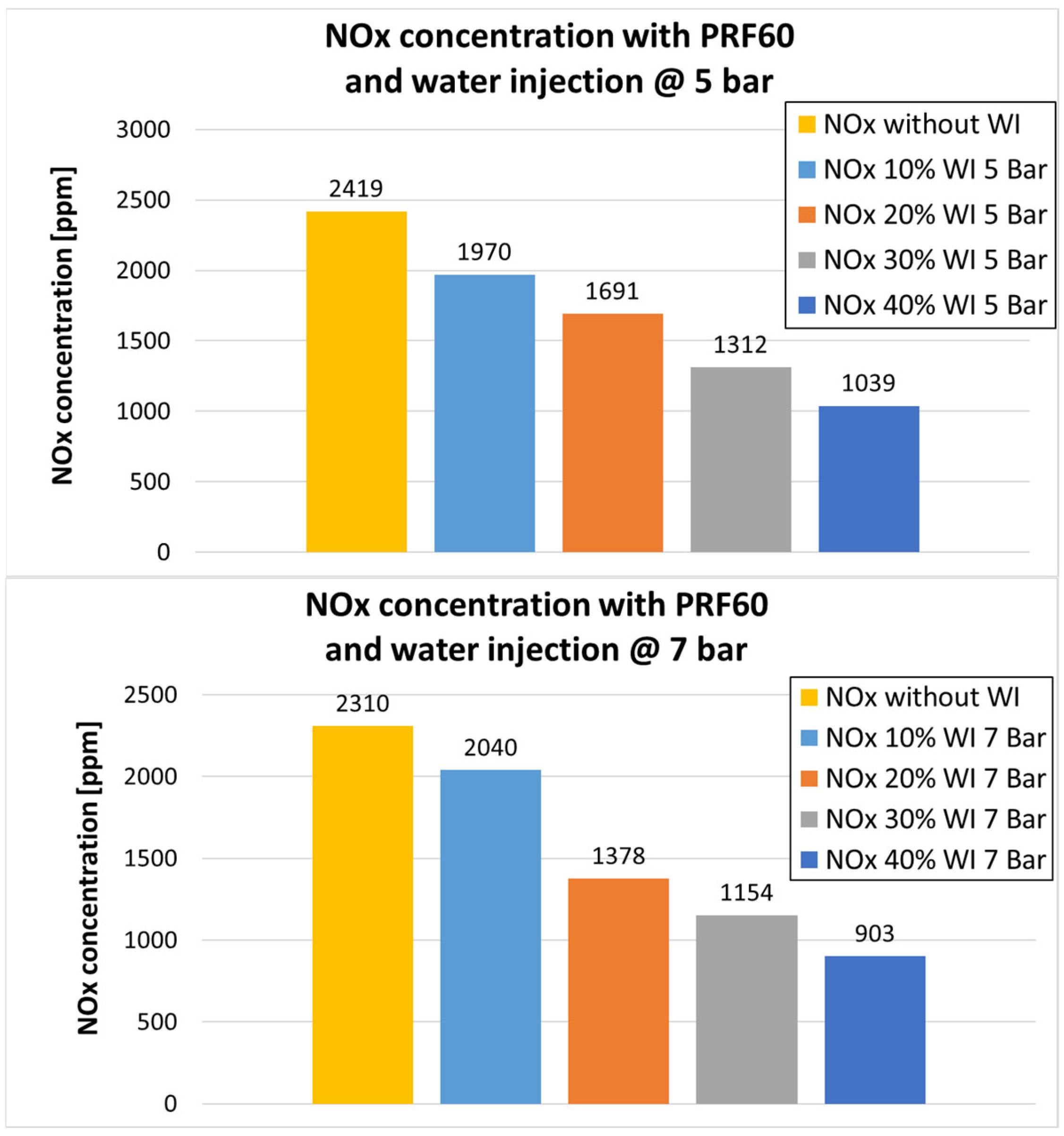

As already mentioned, NOx concentrations in the exhaust gases were also recorded for each operating condition tested. The results of these measurements are shown in the graphs of

Figure 7. As can be observed, under the heavy knock conditions achieved, the cooling effect produced by water injection into the intake duct was also highly effective in reducing nitrogen oxide emissions. Regardless of the injection pressure, NOx emissions showed a clearly decreasing trend as the amount of injected water increased. The results obtained under heavy knocking conditions, therefore, confirm the reductions between 40% and 50% observed under less severe knock conditions and reported in the scientific literature [

12,

15,

16,

22,

31,

32]. The most pronounced reduction (−62%) was recorded with the injection pressure of 7 bar (gauge), also confirming the result observed in the reduction in knocking cycles.

6. Corrected NOX Emissions

As performed by most of the lab equipment usually employed for internal combustion engine exhaust emission measurement, the equipment employed in the experiments carried out in the present study (the ECM NOx 5210 system) measured the level of NOx in terms of volumetric concentration (ppm). It should be noted, however, that injecting water in the intake duct could have modified the composition of the total mass aspirated by the engine. In particular, the addition of a certain amount of water in the intake charge may have changed the total number of molecules aspirated by the engine, and, consequently, the number of molecules in the combustion products. Considering the relevant reduction observed in the concentration of NOx molecules in the combustion products, it is reasonable to ask whether this result may be produced, even partially, from the alteration of the total number of molecules present in the combustion products. In other words, it is reasonable to ask whether water injection increased the total number of molecules in the combustion products, and, if so, is the observed reduction in NOX concentration a consequence of this increment? To address this question, the authors estimated the ratio between the number of molecules present in the combustion products with water injection (NWI) and without water injection (NWO).

Considering that the fuel used, PRF60, is composed of a 60% volumetric fraction of iso-octane C

8H

18 and a 40% volumetric fraction of n-heptane C

7H

16, the equivalent hydrocarbon molecule can be determined through a simple mass balance of carbon and hydrogen:

The balanced redox reaction between the fuel and the combustion air under stoichiometric conditions can, hence, be written as follows:

Considering the water injected into the intake duct and introduced into the engine, and assuming that it does not react, the reaction becomes the following:

where ϕ represents the number of water molecules injected (and introduced into the engine) per molecule of the equivalent hydrocarbon C

7.6 H

17.2. Approximating the molecular weight of water to 18 g/mol, and that of the equivalent hydrocarbon to 108.4 g/mol, the ratio

between the masses of injected water and fuel (from 0% to 40% in this work) is related to the parameter ϕ by the following relation:

Therefore, the number of water molecules injected per molecule of fuel can be calculated as follows:

From Equations (3) and (4), it can be inferred that, for each molecule of equivalent hydrocarbon burned, the number of molecules present in the combustion products without water injection (

NWO) is:

While, with water injection, it becomes

NWI, as follows:

Given the ratio

ψ between the mass of water and the mass of fuel aspirated by the engine, the ratio between the number of molecules in the exhaust gases with and without water injection can be evaluated as follows:

Considering that, in the present work, the parameter

ψ varied between 0% and 40% (i.e., between 0 and 0.4), the following can be deduced:

A fair comparison of the volumetric concentrations of NOx, measured with and without water injection, should be performed on the basis of an equal number of molecules in the combustion products; to accomplish this, the NOx concentration measured with water injection should be corrected by the ratio

NWI/NWO, as follows:

As indicated by relation Equation (10), this correction amounts to a maximum of 4% in the case of 40% water injection. The diagrams reported in

Figure 7 already account for this correction. For the purpose of simple information,

Table 4 reports the measured and corrected NOx concentrations for the case of 40% water injection at a pressure of 7 bar (gauge).

It is worth noting that the proposed correction is based on the assumption that the added water is fully vaporized in the exhaust duct, where the NOx concentration is measured. If the measuring sensor is placed not far from the engine exhaust port (as in the case of the experimental layout of this study), the exhaust gas will be at a temperature sufficiently high to maintain the total mass of water (i.e., the one produced by the combustion, plus the one added by injection) in the vapor phase, thus making the correction procedure valid. In the test bench employed, the thermocouple for the exhaust temperature is placed near the NOx sensor; since the exhaust temperature remained around 500 °C under all the operating conditions tested, no water condensation could occur where the NOx was measured.

7. Conclusions

Water injection is considered a viable option for the implementation of the stoichiometric combustion of hydrogen or e-fuels in internal combustion engines. Although several studies report the main advantages of port water injection, its capacity to suppress high-intensity knocking phenomena is not documented in the scientific literature, above all, with highly reactive fuels. On account of this lack, the authors experimentally investigated the effectiveness of port water injection in suppressing heavy knock phenomena employing a CFR engine, properly modified to allow electronic control of both fuel and water injection; as unique characteristics of this study were carried out, the operating conditions explored were characterized by more than 80% of knocking cycles for extended periods, which could not be replicated in series production engines without causing irreparable damages. Moreover, aiming to approximate hydrogen reactivity, measurements were carried out using a fuel with the same knock resistance, namely a PRF60 (60% iso-octane and 40% n-heptane). Water injection was performed at three different pressures (3, 5, and 7 bar gauge) to assess the importance and effect of jet atomization, and with four different mass fractions (expressed as percentages of fuel mass): 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%.

The experimental results clearly demonstrate that port water injection is highly effective in suppressing severe knock phenomena. As expected, the knock-suppressing effect increased with the amount of water injected. A nearly complete suppression of knock events was achieved with 40% of water injection. Moreover, the most significant knock attenuation was observed when employing the higher injection pressure (7 bar gauge); the finer atomization probably improved and accelerated water evaporation, producing a more effective cooling of the intake air and, thus, reducing or preventing knock.

The effect of port water injection was also investigated on the NOx concentrations in the exhaust gases; a marked reduction was observed as the amount of injected water increased (−62% NOx with 40% water injection). To eliminate the diluting effect of the injected water on the measured NOx concentration, an original correction methodology was applied, allowing for a direct comparison of emissions measured both under dry conditions and with water injection.

Considering the high levels of knock intensities tested, the reactivity of the fuel employed, and the adoption of three different water injection pressures, the present study constitutes a unique reference in the scientific literature, enclosing relevant and archival information.

From an application standpoint, port water injection emerges as a practical solution to enable stoichiometric combustion of hydrogen in internal combustion engines. Industrial adoption of this technology is already attracting interest from key industry players, and recent research confirms its relevance, even in advanced configurations such as GDI engines.