Probabilistic Power Flow Estimation in Power Grids Considering Generator Frequency Regulation Constraints Based on Unscented Transformation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Consideration of the Generator Frequency Regulation Constraint Model

2.1. Generator Frequency Regulation Model

2.2. Frequency Regulation Capacity Constraint Model

2.3. Probabilistic Power Flow Modeling

- Decoupling the relationship between active power and phase angle, as well as between reactive power and voltage magnitude, with the premise that active power is exclusively related to voltage phase angles while reactive power is solely dependent on voltage magnitudes.

- A maximum deviation of nodal voltage magnitudes from the nominal value (1 p.u.) not exceeding 5%, allowing for the simplification of power flow equations to a linear form by disregarding higher-order nonlinear voltage terms.

- Construction of coefficient matrices for active and reactive power flow based on the real and imaginary components of the nodal admittance matrix, respectively. These coefficient matrices remain invariant to system operating conditions, thereby exhibiting a “state-independent” characteristic.

- When conventional units and AGC units adjust active power output for frequency regulation, the reactive power regulation margin changes in accordance with the PQ operational curve characteristics. Concurrently, active power flow redistribution leads to dynamic variations in line reactive power losses (I2X), which are more pronounced in fluctuating areas such as wind power nodes. This, in turn, affects nodal reactive power injection and voltage levels. The model linearizes this indirect influence by embedding reactive–active power coupling factors into the piecewise power flow coefficient matrix, treating reactive power injection as a “correlated variable of active power regulation output”.

- When frequency regulation causes voltage deviations from the rated value, system voltage control devices (e.g., AVR, SVG) prioritize reactive power regulation to maintain voltage stability by adjusting nodal reactive power injection. However, reactive power injection adjustments alter the nodal equivalent admittance characteristics, thereby slightly modifying the active power flow distribution coefficients and affecting the allocation ratio of unbalanced power among regulating units. By establishing the response logic that “voltage control takes precedence over secondary frequency regulation allocation”, the model incorporates voltage deviation thresholds during segment partitioning, ensuring that voltage control corrections to reactive power injection precede power flow calculations, aligning with actual system control logic.

- Focusing on the objective of steady-state probabilistic power flow analysis, transient dynamic coupling between frequency regulation and voltage control (e.g., AVR response delays, generator transient reactive power characteristics) is temporarily neglected. Instead, only the steady-state coupling relationship is characterized—namely, the steady-state reactive power adjustments corresponding to steady-state active power variations, and the steady-state corrections to active power allocation triggered by voltage deviations through reactive power compensation. This simplification not only fits the linearized framework of the DLPF model but also demonstrates its accuracy and reliability in steady-state scenarios through comparative validation with full AC power flow (voltage magnitude error ≤ 0.32%).

- When voltage deviations exceed 5% of the nominal value, computational accuracy decreases, making it difficult to capture active-reactive power coupling effects.

- Its adaptability is limited in strongly nonlinear power grids featuring high-impedance lines, weakly connected nodes, or dense integration of distributed generation.

- It is only applicable to steady-state analysis and cannot characterize transient dynamic coupling relationships.

- The influence of voltage magnitude on active power transmission is neglected, which may introduce minor errors at nodes with high concentrations of voltage-sensitive loads.

3. Power System Probabilistic Analysis Under Unit Frequency Regulation Constraints Based on Unscented Transformation

3.1. The Principle of Unscented Transform

3.2. Unscented Transformation Accounting for Frequency Regulation Constraints

- Calculate the power deviation and match it to the corresponding interval.

- 2.

- State Variable Mapping of the System

- 3.

- Statistical Properties of the Structural State Variables:

4. Case Study Analysis

4.1. Computational Case Configuration

4.1.1. Hardware and Software Environment

4.1.2. Critical Simulation Parameters Configuration

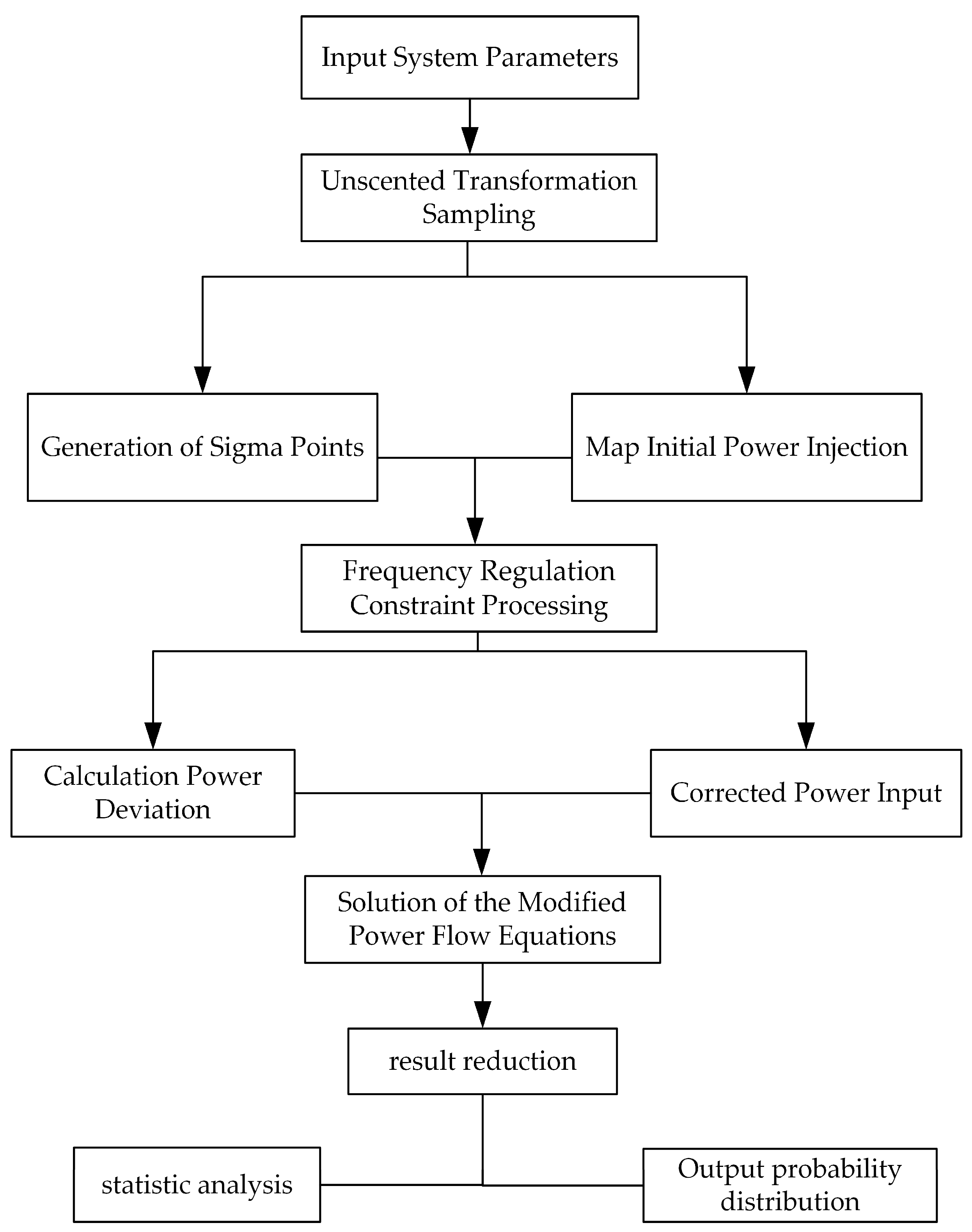

4.2. Algorithm Implementation Workflow

- Input System Parameters

- 2.

- UT Sampling

- 3.

- Frequency Regulation Constraint Processing

- 4.

- Solution of Power Flow Equations

- 5.

- Result Reduction

4.3. Analysis of Simulation Results

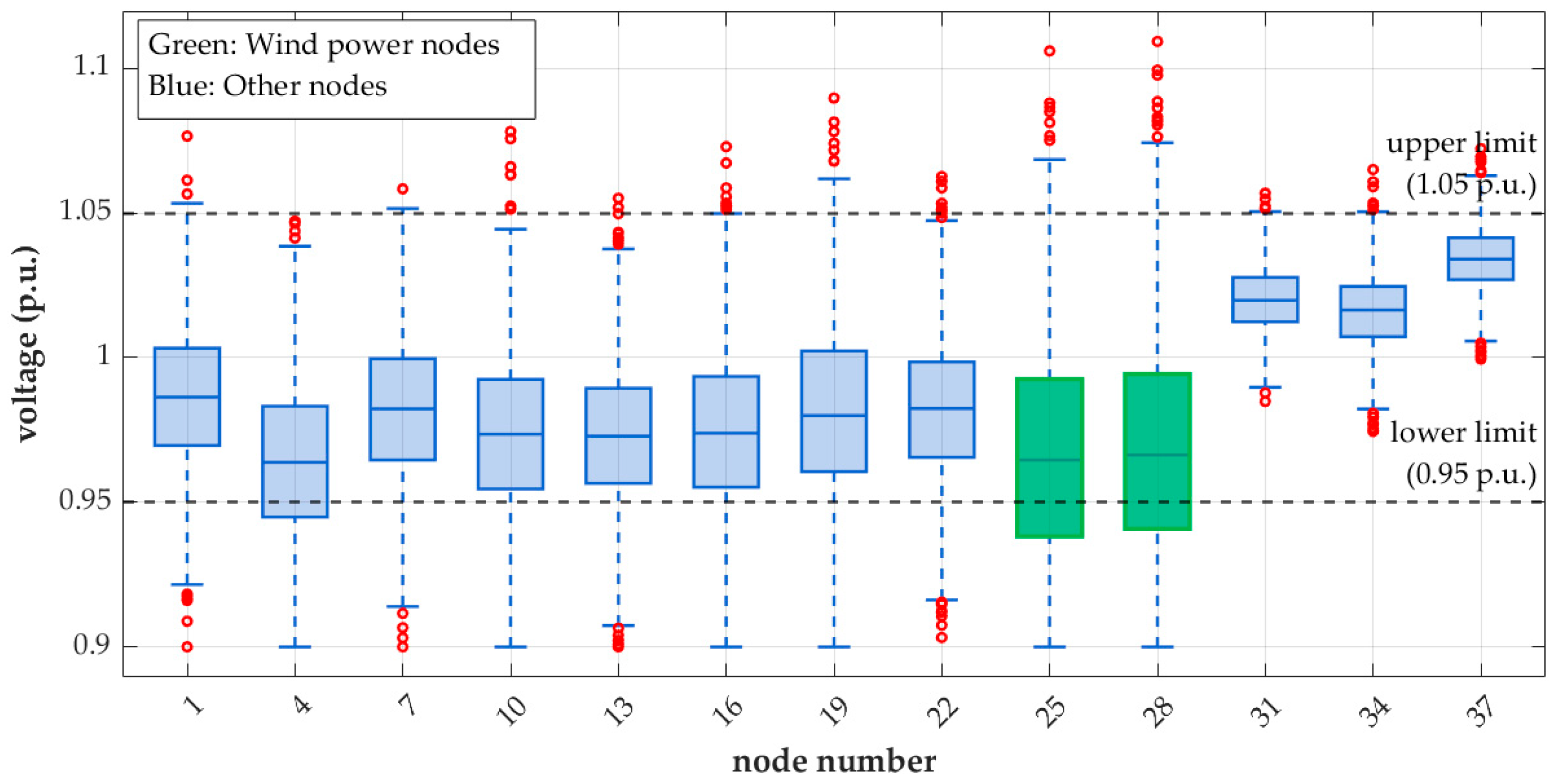

4.3.1. Characteristics of Voltage Distribution and Precision Validation

4.3.2. Computational Efficiency Comparison

4.4. Accuracy Verification and Applicability Criteria of the DLPF Model

4.4.1. Accuracy Comparison Between the DLPF Model and the AC Power Flow Model

- Overall Error Statistics

- 2.

- Key Scenario Error Analysis

4.4.2. Accuracy Limitations and Applicability Conditions of the DLPF Model

- Sources of Accuracy Limitations

- When voltage magnitudes deviate excessively from nominal values (e.g., below 0.9 p.u. or above 1.08 p.u.), the influence of voltage magnitude on active power cannot be ignored, and the decoupling assumption causes a sharp rise in active power flow calculation errors.

- When line flows approach thermal stability limits (e.g., transmission power exceeds 90% of rated capacity), the system exhibits strong nonlinear behavior, making linear approximations inadequate for capturing power flow dynamics.

- When renewable energy outputs experience severe reactive power fluctuations (e.g., the power factor varies substantially within 0.7–0.95), the linear relationship between reactive power and voltage breaks down, compromising voltage magnitude estimation accuracy.

- 2.

- Applicable Operating Conditions

- Renewable energy output characteristics: dominated by active power fluctuations, with relatively stable reactive power output (power factor variation within ±0.05), or equipped with reactive power compensation devices to suppress fluctuations;

- Voltage operating range: all nodal voltages remain within the nominal range of 0.95–1.05 p.u., without severe voltage violations;

- Power flow stability margin: line transmission power does not exceed 85% of rated capacity, avoiding proximity to stability limits;

- Frequency regulation operation: system frequency regulation actions do not trigger widespread, large-scale adjustments in power distribution coefficients across the grid (e.g., no more than three AGC units simultaneously hitting limits).

4.5. Sensitivity Analysis

4.5.1. Sensitivity Analysis of Key UT Parameters

4.5.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Regulation Capacity Constraints

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, L.; Lyu, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Jiang, T.; Shen, J.; Wang, Q. Low-Carbon Energy Automation Dispatching Algorithm Accounting for Stochasticity in Large-Scale Renewable Energy Grid Integration. Electr. Autom. 2024, 46, 17–19+23. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W.; Huo, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhong, K. A Reactive Power Optimization Method for Wind Farm Collector Grids Considering Wind Power Output Uncertainty. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2025, 41, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, H.; Yan, Z.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, S. Uncertainty Representation Method of Power Flow in Distribution Network with High Percentage of Renewable Energy Based on the Multi-fidelity Model. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 2965–2978. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowska, B. Probabilistic load flow. IEEE Trans. Power Appar. Syst. 1974, 93, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwongwanich, A.; Blaabjerg, F. Monte Carlo Simulation with Incremental Damage for Reliability Assessment of Power Electronics. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 7366–7371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, S.; Raiti, S. Probabilistic load flow using Monte Carlo techniques for distribution networks with photovoltaic generators. Sol. Energy 2007, 81, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.M.L.; de Castro, A.M. Risk assessment in probabilistic load flow via Monte Carlo simulation and cross-entropy method. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.J.C.; Moura, R.A.; Assis, F.A.; Schroeder, M.A.O.; Yuan, X.; Hooshyar, A. Evaluation of lightning overvoltages for overhead transmission lines using unscented transform. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2022, 38, 746–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aien, M.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Aminifar, F. Probabilistic Load Flow in Correlated Uncertain Environment Using Unscented Transformation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2012, 27, 2233–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Zhou, S. Comparing Unscented Transformation and Point Estimate Method for Probabilistic Power Flow Computation. COMPEL 2018, 37, 1290–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, O.; Ozgonenel, O.; Thomas, D.W.; Ataseven, M.S. Probabilistic Load Flow of Unbalanced Distribution Systems with Wind Farm. Teh. Vjesn. 2019, 26, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Xia, D.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Lu, W.; Wu, X.; Li, Y. Probabilistic load flow calculation of AC/DC hybrid system based on cumulant method. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 139, 107998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, W.; Fu, X.; He, W.; Wang, W.; Yuan, B. Probability power flow calculation for electric-thermal interconnected integrated energy system based on analytical method. Electr. Power Eng. Technol. 2021, 40, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wang, T.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, B.; Zhang, Y. Analytical method based on improved Gaussian mixture model for probabilistic load flow. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2020, 48, 146–155. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Tang, F.; Liu, D.; Zhou, Y. A Scenario-Based Analytical Method for Probabilistic Load Flow Analysis. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 181, 106193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Ning, Y.; Gu, Y. Calculation of Distribution Network Probabilistic Load Flow Considering Uncertainty of Distributed Generation. Electr. Autom. 2021, 43, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, T.; Lin, X.; Peng, S.; Du, X.; Chen, H.; Li, F.; Tang, J.; Li, W. Probabilistic power flow analysis for hybrid HVAC and LCC-VSC HVDC system. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 142038–142052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Cao, Q.; Xu, S.; Cai, H.; Xie, Z.; Shen, C. Analytical Probabilistic Load Flow Algorithm for Transmission Networks Considering the Constraints of Frequency Regulation Capacity. Proc. CSEE 2023, 43, 8592–8602. [Google Scholar]

| Comparative Dimension | This Study | Reference [17] | Reference [18] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Object of Study | AC transmission network (including new energy and conventional/AGC units) | Hybrid HVAC-LCC-VSC HVDC system | AC transmission network (including new energy and conventional/AGC units) |

| Frequency Regulation Capacity Constraint | Yes (conventional + AGC units, limit-reaching + dynamic allocation) | No (only converter coordination control, no frequency regulation constraints) | Yes (conventional + AGC units, limit-reaching, static allocation) |

| PPF Core Method | UT, DLPF segmented power flow | Nataf transformation, LHS-MCS (simulation method) | GMM, segmented linear analytical method |

| Segmentation Modeling Logic | Frequency deviation interval grading, unit limit-reaching sequence (dual dynamic) | No segmentation, only converter control mode switching | Unit limit-reaching state (single static segmentation) |

| Regulation Activation Sequence | Load ➔ Conventional units ➔ AGC units (hierarchical trigger) | No (no frequency regulation allocation) | Conventional units and AGC units in parallel (sequence is vague) |

| Power Allocation Characteristics | Dynamically update allocation coefficients after limit-reaching | No power allocation, only fixed converter output | Fixed remaining unit coefficients after limit-reaching |

| Core Application Scenarios | Online steady-state probabilistic power flow analysis, risk assessment | Hybrid DC system planning and design | Offline precise probabilistic power flow calculation |

| Node Types | Node Number | ACMC | UT | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Load Bus | 1 | 0.00086 | 0.00085 | 1.16% |

| 10 | 0.00092 | 0.00091 | 1.06% | |

| Wind Power Bus | 25 | 0.00157 | 0.00155 | 1.27% |

| 28 | 0.00163 | 0.00161 | 1.23% | |

| Generator Bus | 30 | 0.00032 | 0.00031 | 3.12% |

| Slack Bus | 39 | 0.00011 | 0.00011 | 0.00% |

| Node Number | Quantile | ACMC | UT | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5th | 0.932 | 0.931 | 0.11% |

| 50th | 0.965 | 0.965 | 0.00% | |

| 90th | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.10% | |

| 25 (Wind Power) | 5th | 0.925 | 0.924 | 0.43% |

| 50th | 0.972 | 0.971 | 0.10% | |

| 90th | 1.015 | 1.010 | 0.47% | |

| 30 (Generator) | 5th | 1.002 | 1.001 | 0.10% |

| 50th | 1.021 | 1.021 | 0.00% | |

| 90th | 1.038 | 1.037 | 0.09% | |

| 39 (Slack) | 5th | 1.010 | 1.010 | 0.00% |

| 50th | 1.018 | 1.018 | 0.00% | |

| 90th | 1.025 | 1.025 | 0.00% |

| Node Types | Node Number | ACMC | UT | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Load Bus | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Wind Power Bus | 25 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.01 |

| 28 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.01 | |

| Generator Bus | 30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Slack Bus | 39 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Calculation Link | ACMC | UT | Efficiency Improvement Multiple |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Power Flow Calculation Time (ms) | 12.8 | 13.1 | 0.97 |

| Total Sampling/Sigma Point Calculation Time (s) | 128.0 (10,000 times × 12.8 ms) | 0.275 (21 times × 13.1 ms) | 465.5 |

| Data Statistics and Result Processing Time (s) | 8.3 | 0.12 | 69.2 |

| Total Calculation Time (s) | 136.3 | 0.395 | 345.1 |

| Indicator | Relative Error of Voltage Magnitude (%) | Relative Error of Voltage Phase Angle (rad) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Value | 0.32 | 0.018 |

| 95th Percentile | 0.78 | 0.029 |

| Maximum Value | 1.17 | 0.035 |

| Engineering Allowable Error Threshold | ≤3.0 | ≤0.05 |

| Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Group | 0.01 | 0 | 2 |

| Group 1 | 0.001 | 0 | 3 |

| Group 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 2 |

| Group 3 | 0.01 | 1 | 2 |

| Group 4 | 0.01 | 0 | 3 |

| Node Type | Node Number | Indicator | Group 1 () | Group 2 () | Group 3 () | Group 4 () |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Load Node | 1 | Mean Value | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Variance | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.43 | 0.31 | ||

| 95th Percentile | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.06 | ||

| Wind Power Node | 25 | Mean Value | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Variance | 1.02 | 1.35 | 0.68 | 0.52 | ||

| 95th Percentile | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.11 | ||

| Generator Node | 30 | Mean Value | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Variance | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.29 | 0.22 | ||

| 95th Percentile | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Scenario | Conventional Unit Regulation Capacity | AGC Unit Regulation Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Scenario | 10% of rated output | 15% of rated output |

| Scenario 1 | 80% of rated output (−20%) | 12% of rated output (−20%) |

| Scenario 2 | 120% of rated output (+20%) | 18% of rated output (+20%) |

| Scenario 3 | 60% of rated output (−40%) | 9% of rated output (−40%) |

| Scenario 4 | 140% of rated output (+40%) | 21% of rated output (+40%) |

| Node Number | Indicator | Baseline Scenario | Scenario 1 (−20%) | Scenario 2 (+20%) | Scenario 3 (−40%) | Scenario 4 (+40%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 (Wind Power) | Voltage Violation Probability (%) | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 0.52 | 0.18 |

| Voltage Variance (p.u.2) | 0.00155 | 0.00162 | 0.00149 | 0.00173 | 0.00142 | |

| 28 (Wind Power) | Voltage Violation Probability (%) | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.57 | 0.20 |

| Voltage Variance (p.u.2) | 0.00161 | 0.00168 | 0.00155 | 0.00180 | 0.00147 | |

| 1 (Load) | Voltage Violation Probability (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Voltage Variance (p.u.2) | 0.00085 | 0.00087 | 0.00083 | 0.00091 | 0.00080 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Miao, Y. Probabilistic Power Flow Estimation in Power Grids Considering Generator Frequency Regulation Constraints Based on Unscented Transformation. Energies 2026, 19, 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020301

Chen J, Miao Y. Probabilistic Power Flow Estimation in Power Grids Considering Generator Frequency Regulation Constraints Based on Unscented Transformation. Energies. 2026; 19(2):301. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020301

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jianghong, and Yuanyuan Miao. 2026. "Probabilistic Power Flow Estimation in Power Grids Considering Generator Frequency Regulation Constraints Based on Unscented Transformation" Energies 19, no. 2: 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020301

APA StyleChen, J., & Miao, Y. (2026). Probabilistic Power Flow Estimation in Power Grids Considering Generator Frequency Regulation Constraints Based on Unscented Transformation. Energies, 19(2), 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020301