1. Introduction

The transition toward decentralised energy systems is reshaping how households interact with electricity. Community microgrids, localised networks that integrate renewable generation, storage, and peer-to-peer exchange, are increasingly recognised as a pathway toward resilient and equitable energy transitions [

1,

2,

3]. Nevertheless, despite growing policy support, household participation in such systems remains uneven. Understanding the behavioural and structural mechanisms that drive or inhibit the adoption of PV systems within these communities is therefore essential for designing effective interventions [

4,

5,

6].

Recent research highlights that PV adoption decisions arise from the joint influence of economic, infrastructural, and social factors [

7,

8,

9]. Economic considerations such as upfront cost, access to incentives, and income remain central, although their impact is strongly context-dependent [

10,

11,

12]. In some settings, expected revenues rather than costs dominate adoption motives, while in other contexts, inadequate access to financing or regressive subsidy schemes limit participation [

7,

8]. Infrastructural factors, including grid hosting capacity, building type, and regulatory design, frequently constrain adoption opportunities, especially in dense urban contexts [

3,

13,

14]. At the same time, social dynamics such as peer effects, community trust, and local leadership amplify economic incentives and facilitate collective action [

15,

16,

17].

Evidence across the recent literature indicates that these three dimensions, economic, infrastructural, and social, interact nonlinearly. Financial incentives may accelerate adoption only when technical and social conditions align [

4,

5,

9]. Moreover, recent reviews emphasise persistent equity and governance challenges, where low-income or apartment-dwelling households remain underrepresented in adoption [

18,

19]. Studies also point to the growing relevance of peer-to-peer (P2P) trading, community governance, and cost-sharing mechanisms, which can redistribute benefits more equitably but remain underexplored empirically [

2,

20].

Despite these insights, existing modelling approaches remain fragmented. Statistical and econometric studies identify correlations but cannot capture dynamic feedback among households. At the same time, most agent-based models (ABMs) lack mathematical transparency, standardised parameterisation, or validation against established diffusion theories [

21,

22,

23]. Only a handful of ABMs explicitly represent the interdependence of financial, infrastructural, and social variables in community microgrid contexts. Even fewer make their structure and data openly available [

2,

24,

25,

26]. This limits the reproducibility of the results and the comparability of policy scenarios across studies.

As highlighted in recent ABM and diffusion studies, these limitations persist due to the lack of full mathematical transparency and reproducibility, the absence of explicit social-influence saturation mechanisms, and the scarce use of global sensitivity analysis.

This study addresses this gap by asking how financial, infrastructural, and social mechanisms jointly shape PV adoption dynamics in community microgrids. To answer this question, we introduce a fully specified and open-source agent-based model that integrates economic, infrastructural, and social drivers of PV adoption within a fuzzy-utility decision framework. The model simulates household decisions under varying levels of financial incentives, grid reliability, and peer influence and evaluates the resulting adoption trajectories under multiple policy scenarios. Validation is performed through comparison with Bass diffusion and discrete choice models, and the parameter influence is quantified using Sobol global sensitivity indices [

27,

28,

29].

Despite substantial progress, existing agent-based models of PV adoption still exhibit three recurring limitations: (i) incomplete mathematical specification of the behavioural, financial, and infrastructural mechanisms, which restricts reproducibility; (ii) limited integration of economic, technical, and social drivers within a unified decision framework; and (iii) scarce application of global sensitivity analysis to quantify the parameter influence on long-term adoption outcomes. These gaps reduce the comparability across studies and limit the explanatory power of ABMs in community microgrid contexts.

This study addresses these gaps through the following contributions:

- 1.

A fully reproducible open-source agent-based model with explicit mathematical specification of all adoption components and decision rules.

- 2.

A fuzzy-utility behavioural formulation integrating financial, infrastructural, and social variables into a unified adoption index.

- 3.

An explicit social-saturation mechanism capturing bounded peer influence in community networks.

- 4.

A ten-year multi-scenario evaluation framework for examining policy, feasibility, and behavioural interventions in community microgrids.

- 5.

A Sobol global sensitivity analysis quantifying the relative importance of six socio-technical parameters affecting long-term adoption.

Table 1 presents a concise comparison of representative PV adoption studies. A more extensive synthesis of the broader literature reviewed for this study is provided in

Appendix A Table A1, which summarises additional empirical, econometric, and agent-based contributions. This appendix offers a comprehensive reference that complements the focused comparison shown in

Table 1 and clarifies the empirical and modelling foundations upon which the framework developed in this paper is built.

By openly publishing the model code and datasets, this research advances transparency in adoption modelling and provides a reproducible benchmark for future studies on sustainable community microgrids. In alignment with the Energies Special Issue on “Advances in Power System and Green Energy”, this work contributes to understanding how decentralised decision-making and behavioural factors interact with infrastructure and policy design to accelerate renewable energy transitions.

To guide the reader,

Section 2 details the model structure, mathematical formulation, and simulation design, including the network topology, decision rules, and validation procedures.

Section 3 presents the scenario experiments, diffusion outcomes, and sensitivity results.

Section 3.5 interprets the implications for policy and community microgrid design, and

Section 4 concludes with the limitations and future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Overview

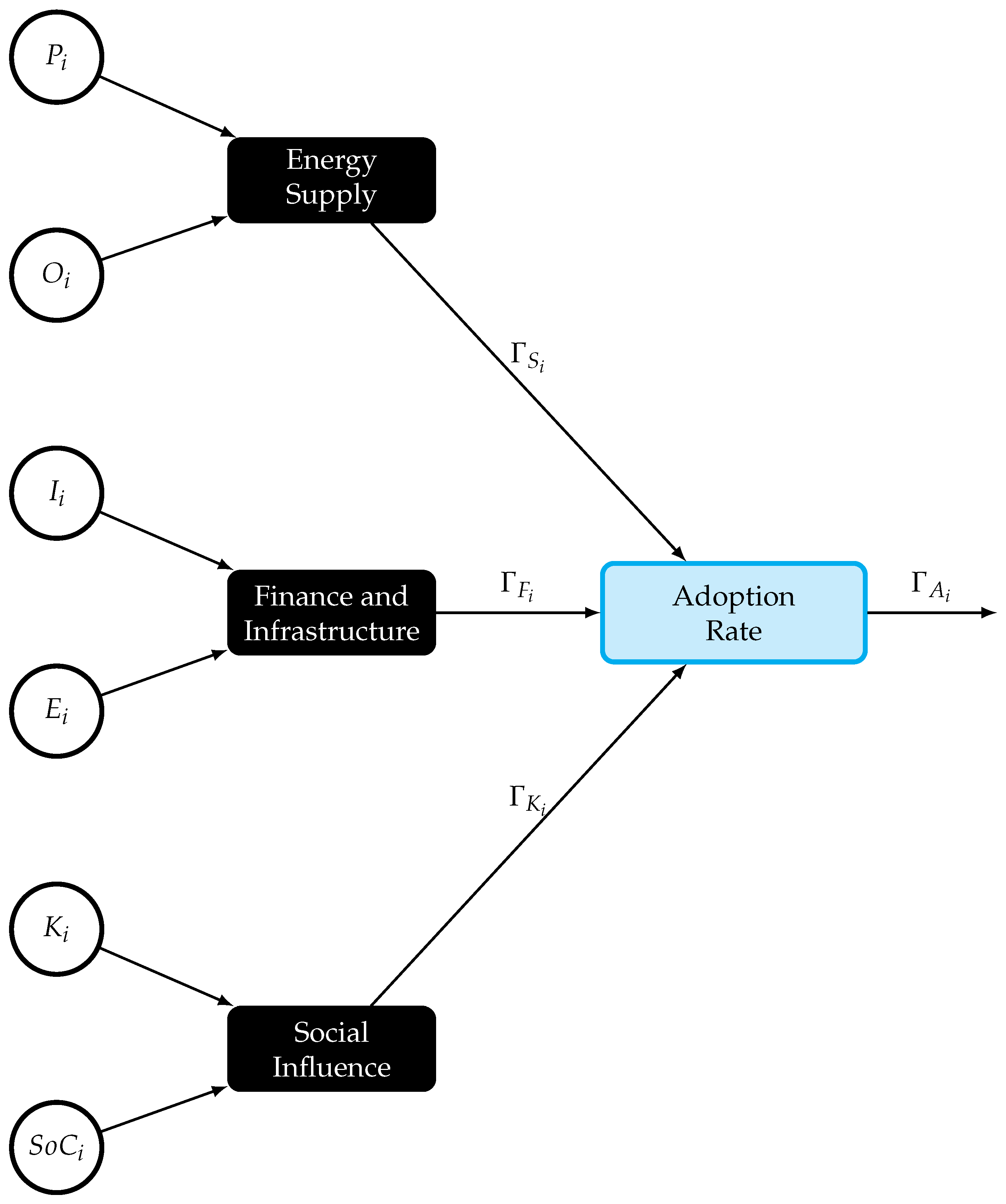

This study develops an ABM to simulate the household adoption of residential PV systems within a community microgrid context. Each household is represented as an autonomous agent, whose decision to adopt PV arises from the interaction among three decision domains: (i) energy supply and reliability, (ii) financial and infrastructural capacity, and (iii) social influence and knowledge diffusion. The model operates on a monthly time step, enabling households to periodically re-evaluate their decisions as external factors (such as subsidies, grid upgrades, or inflation) evolve.

The conceptual structure of the model (

Figure 1) integrates household-level decision variables, policy and market signals, and peer influence feedbacks. This work builds upon the socio-technical adoption framework introduced in [

24], extending it through an explicit mathematical formulation and an open-source Python 3.12.11 implementation to enhance transparency and reproducibility.

2.2. Model Structure and Decision Framework

Each household agent

i evaluates whether to adopt a PV system based on a composite decision function that integrates three key domains:

energy supply,

financial capacity, and

social influence. The overall adoption index

is expressed as

where

,

, and

represent the partial contributions of the energy supply, financial, and social sub-models, respectively. Each sub-model aggregates a set of input variables that are normalised through fuzzy membership functions, allowing the integration of quantitative and qualitative parameters within a unified decision scale.

Table 2 summarises the main input variables and their interpretations.

2.3. Mathematical Formulation

The three sub-models describe how each domain contributes to the overall adoption index.

- (a)

Energy supply domain.

This component reflects how cost and reliability shape the household’s perception of energy quality:

where the first term captures the effect of price and inflation, and the second term represents reliability improvements or losses due to grid performance. The use of reliability and cost components as determinants of perceived energy quality aligns with prior modelling of distributed energy decisions in agent-based simulations [

30].

- (b)

Financial and infrastructural domain.

This sub-model measures the household’s economic and technical readiness to adopt PV:

The first term (

) reflects structural feasibility, while the second term quantifies the interaction between internal financial strength (

) and external support (

). The inclusion of financial capacity and external incentives as multiplicative drivers is consistent with prior ABM formulations of energy technology adoption, which emphasise the joint effect of structural feasibility and economic readiness [

30].

- (c)

Social and behavioural domain.

This component captures peer learning, social norms, and community influence:

Knowledge and exposure to prior adopters (

) enhance confidence in the technology, while social belonging and peer influence encourage imitation within the network. The representation of peer effects and social learning follows empirical and modelling evidence from residential energy adoption studies, particularly in agent-based frameworks [

30,

31].

- (d)

Aggregation and decision rule.

The aggregated adoption index is computed as a weighted sum of the three sub-models:

This linear weighted aggregation follows the classical Multi-Attribute Utility Theory (MAUT) structure described in Keeney and Raiffa (1976) [

32] and the standard Simple Additive Weighting (SAW) approach used in multi-criteria decision analysis, as discussed in Dodgson (2009) [

33].

A household adopts when the aggregate index exceeds a calibrated threshold

:

Binary adoption based on surpassing a minimum feasibility threshold is consistent with utility-based decision rules used in both MAUT frameworks [

32] and energy technology ABMs [

30].

The resulting adoption probabilities are classified into four fuzzy linguistic categories,

unlikely,

uncertain,

probable, and

very probable, based on the membership functions defined in

Appendix B. The membership functions follow standard fuzzy decision-modelling practice, mapping raw variables onto the

interval with trapezoidal and sigmoid shapes to represent low, medium, and high levels of energy quality, financial capacity, and social support (see, e.g., [

24,

34,

35]). The weighted aggregation in Equation (

5) assigns relative importance to the three domains through

, while the threshold

in Equation (

6) determines the minimum combined feasibility required for adoption. Together, the domain-specific membership functions, weights, and threshold fully specify the adoption index

used throughout the simulations. Each non-adopting household re-evaluates Equations (

2)–(

6) in every simulation step, as the external conditions (e.g., incentives or grid upgrades) evolve.

In the simulation, the continuous adoption index

produced by the fuzzy aggregation in Equation (

5) is passed to the logistic rule in Equation (

7). Conceptually, the crisp threshold

is embedded in the intercept–slope pair

, while the fuzzy categories are retained for interpretive analysis of household propensities. This ensures consistency between the behavioural formulation and the probabilistic decision mechanism used in the model.

To ensure full reproducibility of the adoption mechanism, all parameters involved in (i) the membership-function blocks

, (ii) the aggregation operator in Equation (

5), and (iii) the logistic decision rule in Equation (

7) are summarised in

Table 3. The table reports the domain weights, feasibility thresholds, saturation coefficient, logistic parameters, review cadence, and the formal definition of the peer-share term. Together, these elements fully specify how the adoption index

is constructed and how it is mapped into adoption probabilities in the simulation.

2.4. Simulation Setup

This section describes the structural environment, social network, decision timing, scenario design, and parameter settings used in the simulations. The model represents a stylised community microgrid composed of heterogeneous households. All agents differ in financial capacity, infrastructure readiness, knowledge, and social influence, which are drawn from continuous distributions to reflect the household variability.

2.4.1. Population and Time Horizon

Each simulation runs for months (ten years). Agents reconsider adoption monthly, subject to a scenario-specific review cooldown of either 3 or 6 months. All simulations use ten stochastic replicates per scenario with distinct random seeds to ensure reproducibility. The results are reported as the mean adoption trajectories with standard deviation envelopes, and the final adoption shares include 95% confidence intervals.

2.4.2. Network Interaction Structure

Peer interactions occur on a Watts–Strogatz (WS) small-world network with nodes, mean degree , and rewiring probability . This configuration captures neighbourhood-scale diffusion patterns: most connections are local, while a minority of long-range ties accelerate the information spread. All edges are undirected and unweighted in the baseline configuration.

Short sensitivity checks with and produced qualitatively similar diffusion trajectories (changes below 5–7%), indicating that the adoption dynamics are robust to reasonable changes in the network density and randomness.

Peer influence enters the community decision block as the fraction of adopting neighbours (the peer-share). Social saturation is implemented through the subtractive plateau term in the adoption utility:

where

is the fraction of adopters at time

t. This introduces diminishing returns from social imitation as adoption accumulates.

2.4.3. Decision Updating and Logistic Adoption

At each time step, the model aggregates the outputs of three decision blocks—

supply,

finance, and

community—into a single adoption index

. This index is mapped to an adoption probability using the logistic function

where

sets the baseline propensity to adopt, and

controls the sensitivity to the combined utility. This specification follows standard discrete-choice and diffusion models in energy adoption studies [

6,

22]. Households that do not adopt after an evaluation defer their next review by the scenario’s cooldown period.

2.4.4. Scenarios and Outputs

Five scenarios are examined: (a) Baseline, (b) Policy ON, (c) Cooldown + Sat 0.5, (d) Strict Feasibility, and (e) Pessimistic Constraints. These scenarios vary the social saturation, feasibility thresholds, learning mechanisms, and network weighting.

All outputs (adoption trajectories, scenario summaries, and replicate-level CSV files) are generated automatically and stored for reproducibility. Parameter files, scripts, and configuration sweeps are available in the public repository [

36].

2.4.5. Model Parameters

Table 4 and

Table 5 list the structural, network, behavioural, and feasibility parameters used in the simulations.

Table 4 summarises the model scale, network topology, logistic parameters, decision weights, cooldown periods, and saturation strengths.

Table 5 presents the feasibility thresholds, policy and learning switches, randomness settings, and output files.

2.4.6. Feasibility Thresholds

The feasibility thresholds and represent the structural and financial constraints at the household level. Lower values correspond to dwellings with a suitable roof area and straightforward installation conditions, whereas higher values correspond to limited surface or complex retrofitting requirements. The range specified for captures variations in credit access, income stability, and debt tolerance. Households falling below either threshold are unable to adopt even under favourable policy conditions, reflecting real-world barriers that cannot be overcome solely through incentives.

Taken together, these elements ensure that the simulation design balances computational efficiency with behavioural realism. Sensitivity checks confirmed that the core diffusion patterns remain stable under reasonable variations in network parameters and feasibility thresholds, supporting the internal consistency of the configuration.

2.5. Baseline Calibration and Validation

The basic setup was designed to reflect real-world solar panel adoption in a typical community microgrid without any added policy support. The parameter values were derived from prior empirical and modelling studies on household and community solar PV diffusion. The selections incorporate social, infrastructural, and financial determinants identified in the literature [

5,

6,

7,

11,

15,

21,

22,

27,

28,

29,

37,

38]. These values were fine-tuned to produce reasonable adoption index over time under conditions with little financial support. Key behavioural coefficients (

,

) and feasibility thresholds (

,

) were calibrated through iterative simulations. This ensured that adoption emerged from agent interactions and not through externally imposed targets. The model was executed for 120 months (10 years) with

agents. It incorporated heterogeneity in financial capacity, infrastructure readiness, and peer-learning behaviour.

To strengthen the calibration transparency, we explicitly benchmarked the baseline trajectory against the empirical PV adoption ranges reported in recent studies and linked this to the Bass diffusion validation presented in

Section 2.7, which yields a high goodness-of-fit (

). This combined calibration–validation step clarifies that the baseline configuration reproduces realistic diffusion dynamics while remaining exploratory rather than predictive.

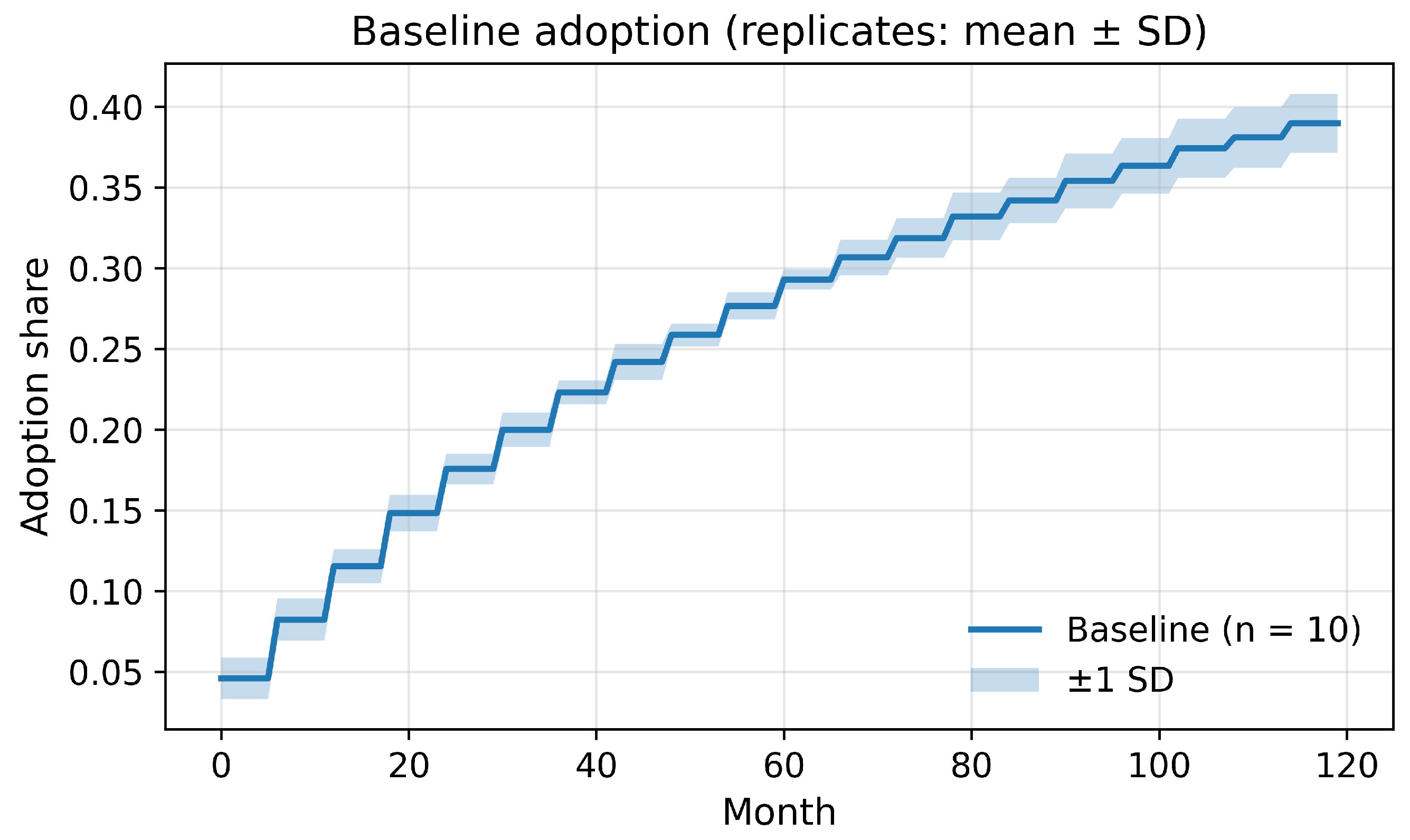

The simulation results, shown in

Figure 2, display the average adoption path across ten runs, with the shaded area marking

standard deviation above and below the mean. The resulting curve shows the S-shaped diffusion pattern seen in community PV studies. Initial slow uptake is due to innovators and early adopters. Acceleration follows as peer learning and visibility accumulate. A saturation tendency appears as eligible households are exhausted.

After ten years, the mean adoption share stabilises around 0.35–0.45. This matches the reported penetration for community solar initiatives with moderate incentives and gradual infrastructure improvements.

This baseline configuration serves as the reference scenario for policy and sensitivity experiments, providing a consistent benchmark to assess the effects of interventions such as stronger subsidies, accelerated grid upgrades, or enhanced peer programs. The variation envelope quantifies the degree of stochasticity in decentralised adoption, illustrating how different intervention scenarios can lead to varied adoption outcomes.

2.6. Python Implementation

The simulation framework was designed for transparency and reproducibility. Model parameters are stored in structured.json files, allowing systematic scenario generation and batch execution. Each run produces time-series outputs in CSV format, which are automatically aggregated into summary statistics and plots (.png) for analysis. The modular structure enables rapid parameter sweeps, parallelised scenario testing, and integration with validation routines such as the Bass model fit and Sobol sensitivity analysis.

2.7. Model Validation

The present model is designed as an exploratory and reproducible benchmark rather than as a calibrated forecasting tool. Because household characteristics are generated from synthetic distributions, and empirical adoption data are not included in this version, external predictive validity is intentionally limited. The objective is to isolate and evaluate the mechanistic contributions of financial, infrastructural, and social drivers under controlled conditions, providing a transparent foundation for future calibration and empirical cross validation.

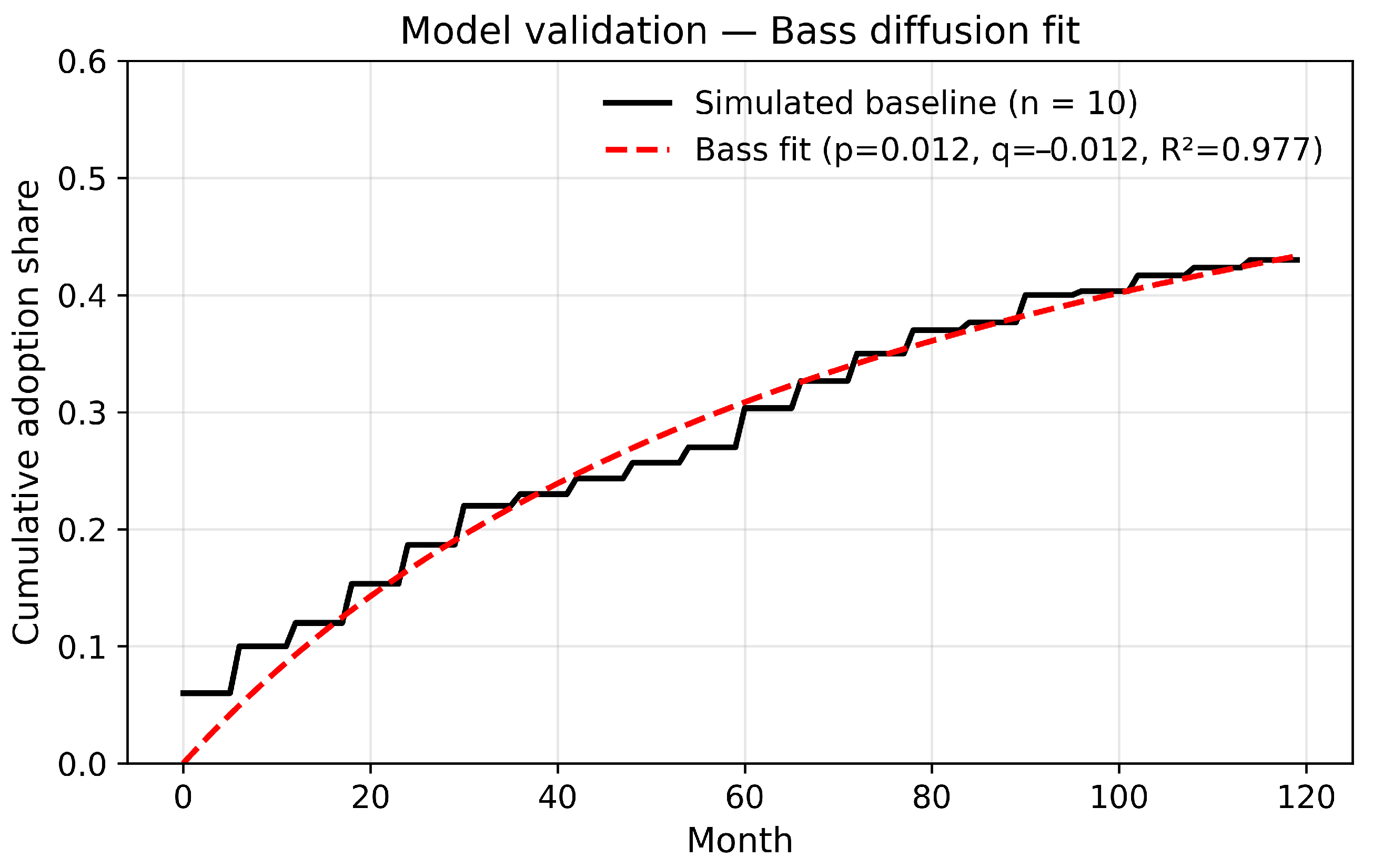

Model validation was performed in two complementary steps to evaluate both the temporal adoption dynamics and parameter influence on model outcomes.

2.7.1. Comparison with Bass Diffusion

The baseline scenario was fitted to the classical Bass diffusion model [

27] using nonlinear least squares optimisation. The estimated parameters were

,

, and

, yielding a high goodness of fit (

), as shown in

Figure 3. This strong correlation confirms that the simulated adoption trajectory reproduces the expected S-shaped cumulative growth observed in empirical technology diffusion studies. The slight negative imitation coefficient (

) reflects a slower-than-exponential social contagion effect, consistent with scenarios dominated by financial and infrastructural constraints.

2.7.2. Global Sensitivity Analysis

A Sobol global sensitivity analysis [

28,

29] was conducted to quantify the contribution of six uncertain parameters to the variance in the final adoption share at the end of the simulation horizon (month 120). Let

denote the model output, where

represents the

j-th input parameter and

. Following the variance–decomposition framework of Sobol, the total variance of

Y can be expanded as

where

denotes the partial variance attributed to parameter

,

the variance due to the interaction between

and

, and higher–order terms capture deeper interactions.

The

first–order Sobol sensitivity index for parameter

is defined as

and measures the direct (main) effect of

on the output variance. The

total–order index

captures both the main effect of

and all its interaction effects with the remaining parameters:

where

denotes the set of all inputs except

.

The indices

and

were estimated using the Saltelli sampling design [

29] with a base sample size of

, resulting in

model evaluations. This approach yields unbiased estimates of both first-order and total-order effects while efficiently exploring the parameter interactions.

The resulting indices (

Figure 4) indicate that

(minimum infrastructure threshold) and

(saturation strength) are the dominant drivers of outcome variability, jointly explaining over 60% of the total variance. The baseline propensity (

) and financial feasibility (

) have moderate effects, while

(utility sensitivity) and

(innovator fraction) contribute minimally. These findings confirm that economic feasibility and infrastructure constraints outweigh social contagion in determining long-term adoption levels.

2.7.3. Summary of Validation Metrics

Table 6 summarises the key validation indicators derived from both analyses.

Overall, these results demonstrate that the model reproduces realistic adoption dynamics and that its behavioural outputs respond systematically to parameter variation, supporting both the validity and interpretability.

Taken together, these validation results establish both the internal consistency and behavioural coherence of the model. Building on this foundation, the next section outlines the key assumptions and structural boundaries that frame the interpretation of all subsequent scenario outcomes.

2.8. Limitations and Assumptions

The model incorporates several simplifying assumptions to enhance the transparency and computational tractability.

Model simplifications: Tariffs, grid reliability, and incentive conditions are assumed to be homogeneous across all agents, excluding spatial or demographic heterogeneity in policy exposure. The agent population and network topology (Watts–Strogatz small-world structure) remain constant throughout the simulation, precluding network evolution or demographic turnover. External factors such as incentive presence and grid upgrades are treated as exogenous stochastic processes updated annually, without endogenous policy feedback or adaptive learning decay over time.

Data and representation limitations: Agents’ characteristics, including financial capacity, infrastructure readiness, and knowledge level, are synthetically generated from Beta distributions to reproduce plausible diversity without relying on proprietary datasets. No empirical household data are directly used for calibration in this version of the model.

Given these simplifications, the results should be interpreted as exploratory rather than predictive. The model’s purpose is to provide a reproducible transparent benchmark for evaluating the systemic interaction of financial, infrastructural, and social mechanisms in PV adoption rather than to forecast specific market outcomes. Future work will extend this framework by incorporating empirical household data, observed adoption records, and policy-specific heterogeneity to calibrate and cross validate model parameters under real-world conditions. In addition, coupling this behavioural framework with techno-economic optimisation models could support integrated assessments of distributed energy policy and microgrid design, aligning with the objectives of the Energies Special Issue on sustainable power systems.

4. Conclusions

This study developed and validated a reproducible agent-based model to simulate the household adoption of PV systems in community microgrids. The model integrates economic, infrastructural, and social dimensions, advancing previous work by combining transparent mathematical formulation, open-source Python implementation, and systematic sensitivity analysis.

The simulation results show that adoption follows the characteristic S-shaped diffusion pattern. The final penetration levels are strongly influenced by financial feasibility and saturation reinforcement. Policy and behavioural-learning interventions accelerate diffusion, while restrictive feasibility conditions or limited incentives constrain adoption. Across all scenarios, affordability and infrastructure readiness are the primary drivers, with behavioural contagion and innovation seeding playing secondary roles.

Validation against the Bass diffusion model confirmed high temporal fidelity (). Sobol indices show that the minimum investment threshold and saturation strength together explain over 60% of the total variance. These results establish the model’s internal consistency and its ability to capture the interplay of behavioural and structural factors in decentralised energy transitions.

Beyond methodological contributions, this work highlights the need for integrated policy design. Financial accessibility should be combined with social engagement and infrastructural reliability to sustain adoption in community energy systems. Future extensions will incorporate empirical household datasets, policy heterogeneity, and spatial network evolution to enhance predictive realism and policy relevance.