A Critical Review of Green Hydrogen Production by Electrolysis: From Technology and Modeling to Performance and Cost

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Examining hydrogen production, applications, and associated challenges;

- Comparing major electrolyzer technologies in terms of maturity, performance, and integration potential;

- Reviewing recent advances in the modeling of electrolyzers and their integration into energy systems;

- Identifying research gaps and future directions to scale up green hydrogen sustainably.

2. Hydrogen in the Energy Transition

2.1. Hydrogen Production Pathways

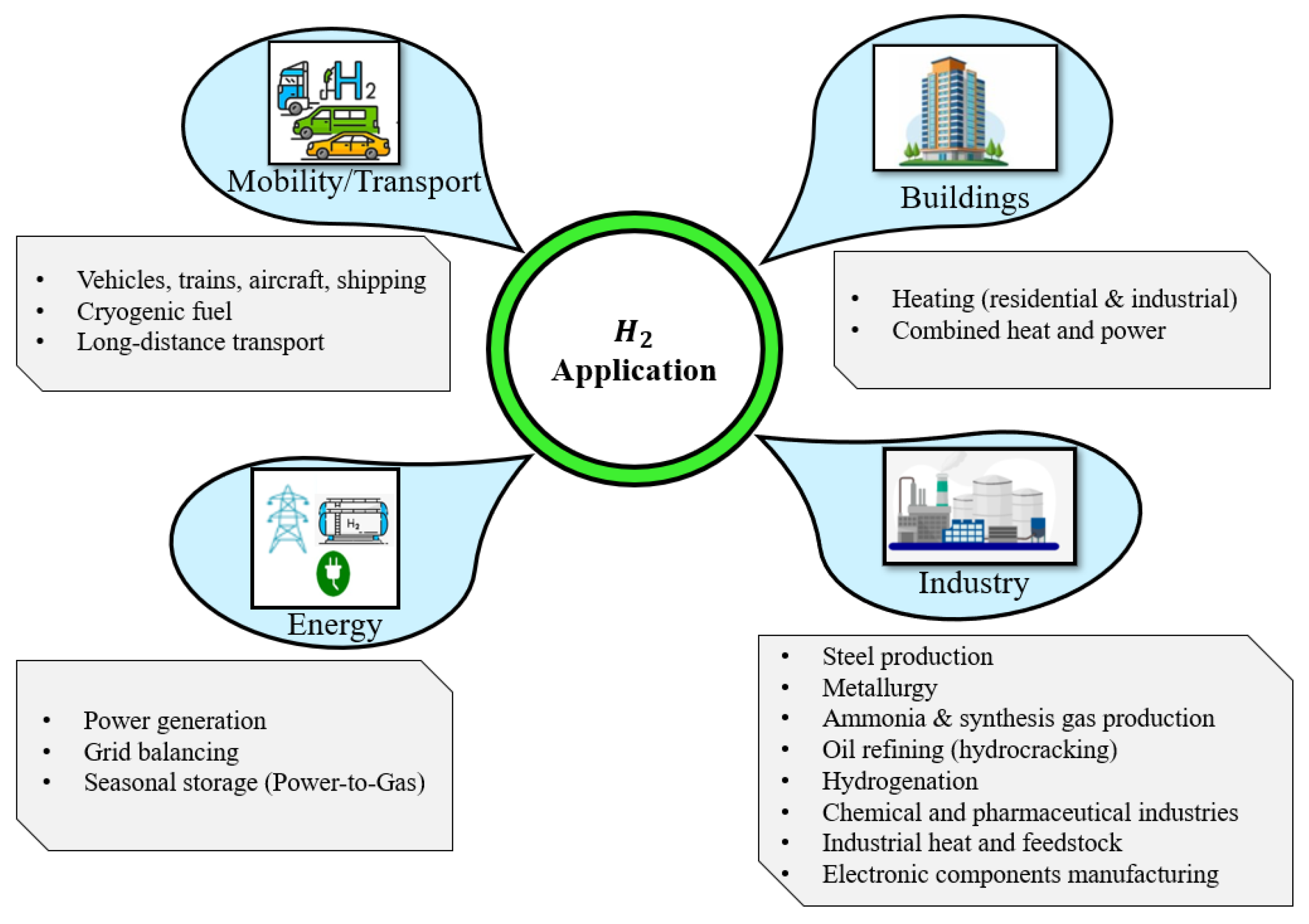

2.2. Hydrogen Integration and Applications

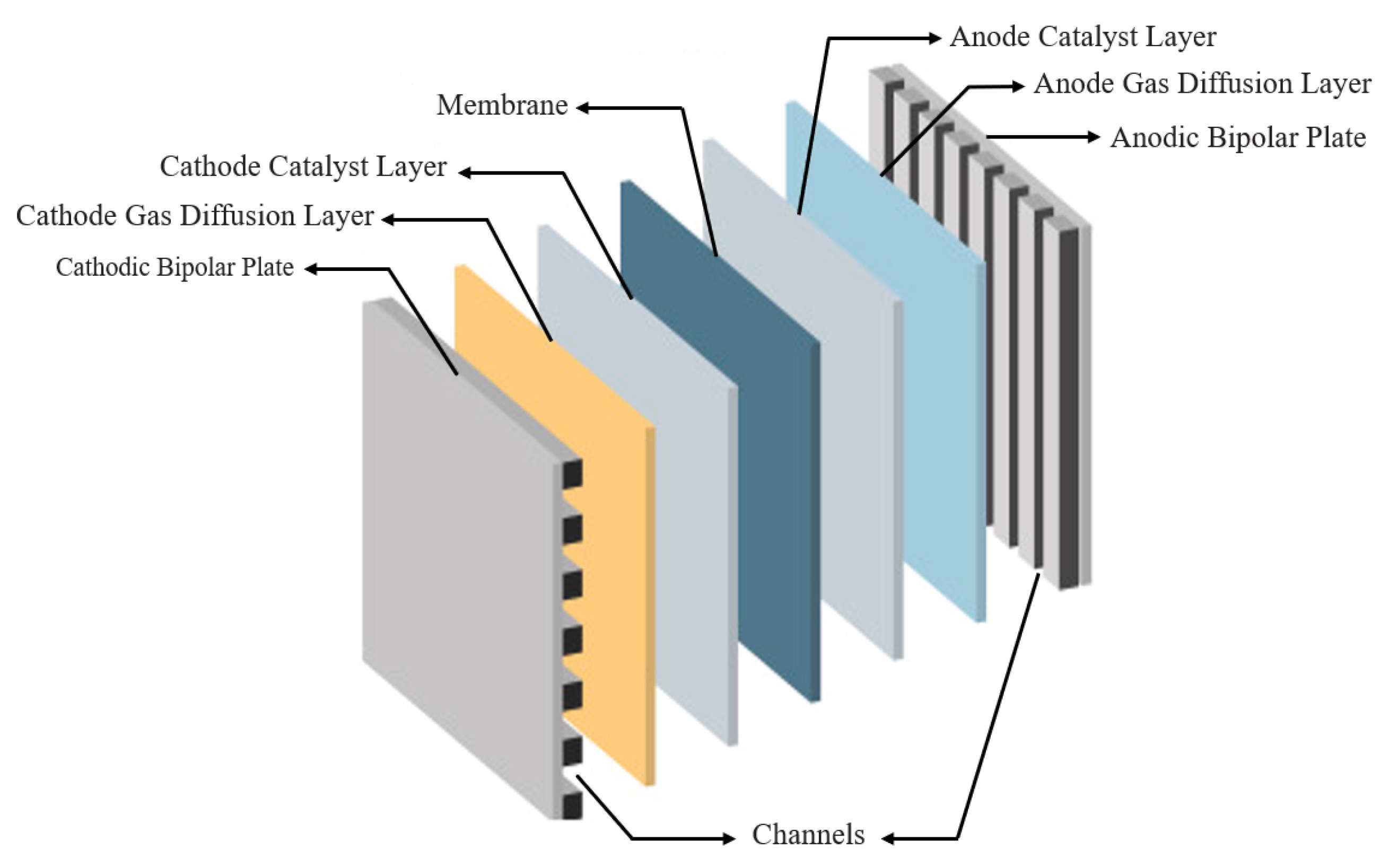

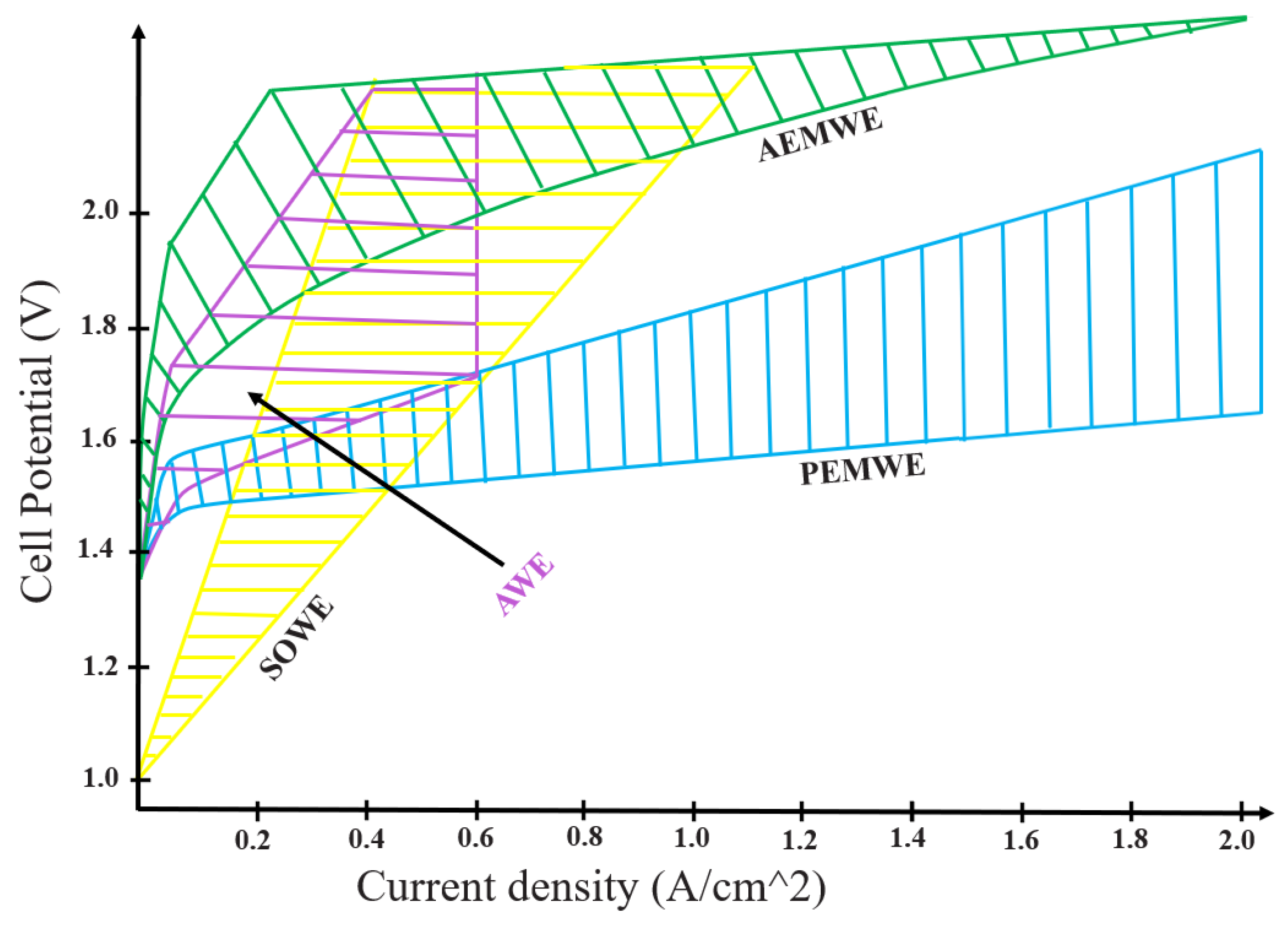

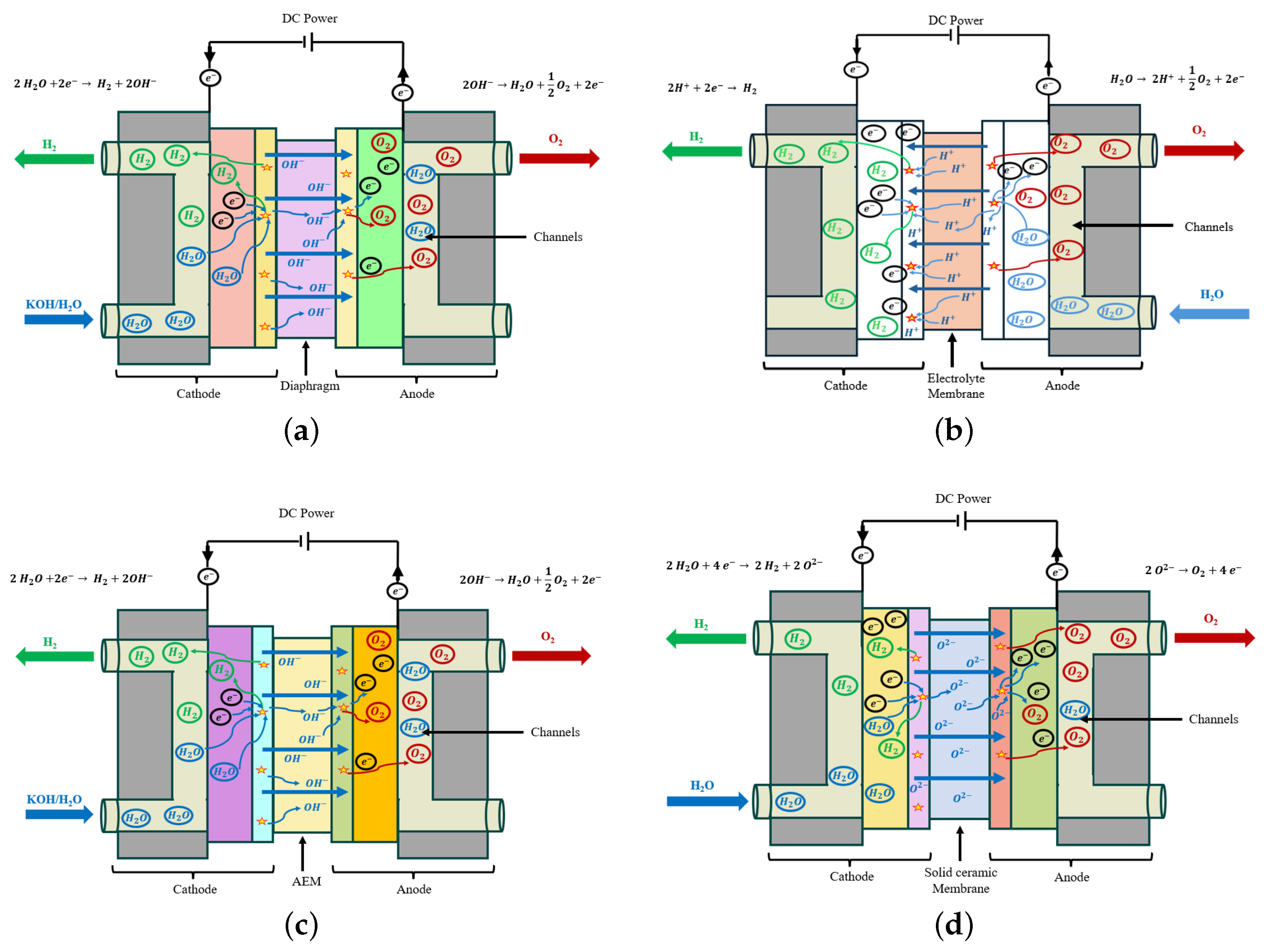

2.3. Electrolysis Technologies

| Specification | PEMWE | AWE | AEMWE | SOWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maturity | Commercial | Commercial | early commercial | early commercial |

| Charge carrier | H+ | Hydroxide ions OH– or hydronium ions H3O+ | OH– | O2– |

| Electrolyte | Perfluoro Sulfonic Acid (PFSA) polymer membrane | Concentrated aqueous alkaline solution (25–40 wt% KOH/NaOH) | Anion-exchange polymer membrane | Solid oxide ceramic electrolyte (oxygen-ion conductor, e.g., YSZ) |

| Working fluid | Ultrapure water (conductivity < 1 µS/cm) | Aqueous alkaline electrolyte | Deionized water or low-concentration alkaline solution | High-temperature steam (H2O(g)) |

| Operating temperature | 30–90 °C | 60–90 °C | 50–70 °C | 650–1000 °C |

| Operating pressure | Can operate at elevated pressure; the membrane ensures very low gas crossover even under pressure differentials | Typically limited to low pressure and requires balanced pressure between electrodes to prevent gas mixing | Capable of operating at moderate to high pressure, depending on membrane stability | Usually operated at near-atmospheric or moderate pressure, with pressure mainly applied at the stack level |

| Volume | Compact stack design with high power density (small footprint) | Bulkier stack due to thicker components and liquid electrolyte management | Similar to PEM in principle, but current prototypes are generally less compact | Typically larger and more complex stack, often requiring thermal insulation and balance-of-plant volume |

| Production scale | kW to multi MW (modular, flexible deployment) | MW to GW (suitable for large scale plants) | kW to low MW (currently limited in scale) | kW to pilot scale MW |

| Response time | Fast response; can rapidly follow fluctuations in power supply | Slower response due to liquid electrolyte dynamics and gas liquid mass transfer limitations | Generally fast response, similar to PEM | Limited flexibility; high temperature operation constrains rapid load changes |

| Application | Highly suitable for renewable energy integration due to fast response and high energy efficiency | Less suitable for intermittent RESs; frequent start–stop cycles accelerate electrode degradation. Preferably operated in stable, grid-connected, large scale systems | Potentially suitable for renewable coupling, but long term durability under dynamic conditions is still under investigation | Best suited for high temperature, continuous operation (e.g., industrial waste heat); limited compatibility with highly fluctuating renewable input |

| Maintenance | Moderate maintenance due to electrocatalyst degradation in acidic environment; solid electrolyte reduces mechanical upkeep | Requires regular maintenance because of corrosive liquid electrolyte, scaling, and gas–liquid management | Potential for lower maintenance (solid electrolyte), but long term chemical stability remains a concern | High maintenance requirements due to high temperature operation, thermal cycling stress, and material degradation |

| Stack lifetime | <40,000 h | <90,000 h | >10,000 h | <40,000 h |

| Efficiency, HHV | 67–84% | 62–82% | Similar to PEM (currently 60–75%) | ∼90% |

| Current density | 0.2–2 A/cm2 | 0.2–0.6 A/cm2 | 0.2–1 A/cm2 | 0.3–1 A/cm2 |

| Key market actors | Siemens Energy, ITM Power, Plug Power, Nel Hydrogen, Cummins | Nel Hydrogen, Light Bridge, McPhy, H2Planet | Enapter, John Cockerill, Leancat | Sunfire, Topsoe, Bloom Energy, Genvia, Plug Power |

| Advantages | Compact and simple stack design; fast response and start-up; high hydrogen purity; capable of operating at high current densities | Low capital cost; technologically mature and well-established; no use of noble metals | Combines benefits of PEM and alkaline systems; suitable for dynamic operation and load fluctuations; uses low-cost, non-corrosive electrolyte and cheap components | Can operate reversibly as a fuel cell; very high efficiency due to high-temperature operation; low noble metal usage reduces capital cost |

| Drawbacks | High capital cost due to expensive membranes and noble metal catalysts; limited lifetime; sensitivity to water purity; historically limited to small and medium scale applications | Lower current densities; larger footprint; slower dynamic response; requires corrosive liquid electrolyte management; risk of gas crossover at low loads | Membrane stability and durability still limited; performance and lifetime lower than PEM; technology not yet fully optimized; sensitivity to contamination of electrolyte | Requires very high operating temperatures; material degradation due to thermal cycling; sealing and interface challenges; complex BoP; currently limited operational flexibility |

2.4. Techno-Economic Comparison of Electrolyzer Technologies

2.5. Materials in Electrolyzer Technologies: Functional Roles, Selection Criteria, and Supply Considerations

| Functional Layer | PEMWE | AWE | AEMWE | SOWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anodic Bipolar Plate | Titanium (uncoated or TiN/Pt-coated) | Nickel or stainless steel | Nickel or stainless steel | Ferritic stainless steel (e.g., Crofer 22 APU) |

| Cathodic Bipolar Plate | Titanium or coated Ti | Nickel or stainless steel | Nickel or stainless steel | Ferritic stainless steel or Ni-based alloys |

| Anodic GDL/PTL | Sintered titanium or Ti felt (often coated) | Nickel foam or mesh | Nickel foam or mesh | Porous ceramic (e.g., LSM or lanthanum ferrite) |

| Cathodic GDL/PTL | Carbon paper/felt or Pt-coated Ti mesh | Nickel mesh or foam | Stainless steel, Ni mesh or carbon-based materials | Ni-based porous cermet |

| Anode catalyst | Iridium or ruthenium on titanium substrate | Nickel, Raney Ni, or Ni-based alloys | NiFeOx, Co-based spinels, or MnOx | LSM or LSCF (perovskite-type oxides) |

| Cathode catalyst | Platinum or Pt alloys on carbon support | Nickel or Ni alloys | Ni, Ag, or MnCo2O4 | Ni-YSZ (cermet) |

| Membrane/Separator | Nafion (PFSA) or other proton-conducting membrane | Zirfon (porous diaphragm) (zirconia/polysulfone) | Anion-exchange membrane (quaternary ammonium functionalized polymer) | Ceramic YSZ electrolyte layer |

| Electrolyte | Solid polymer electrolyte (e.g., Nafion) | KOH or NaOH aqueous solution (25–40 wt%) | Anion-exchange membrane + dilute KOH or NaOH | YSZ (Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia) ceramic |

3. Degradation Mechanisms Across Electrolyzer Technologies

4. Comparison and Evaluation of Electrolyzer Modeling Approaches

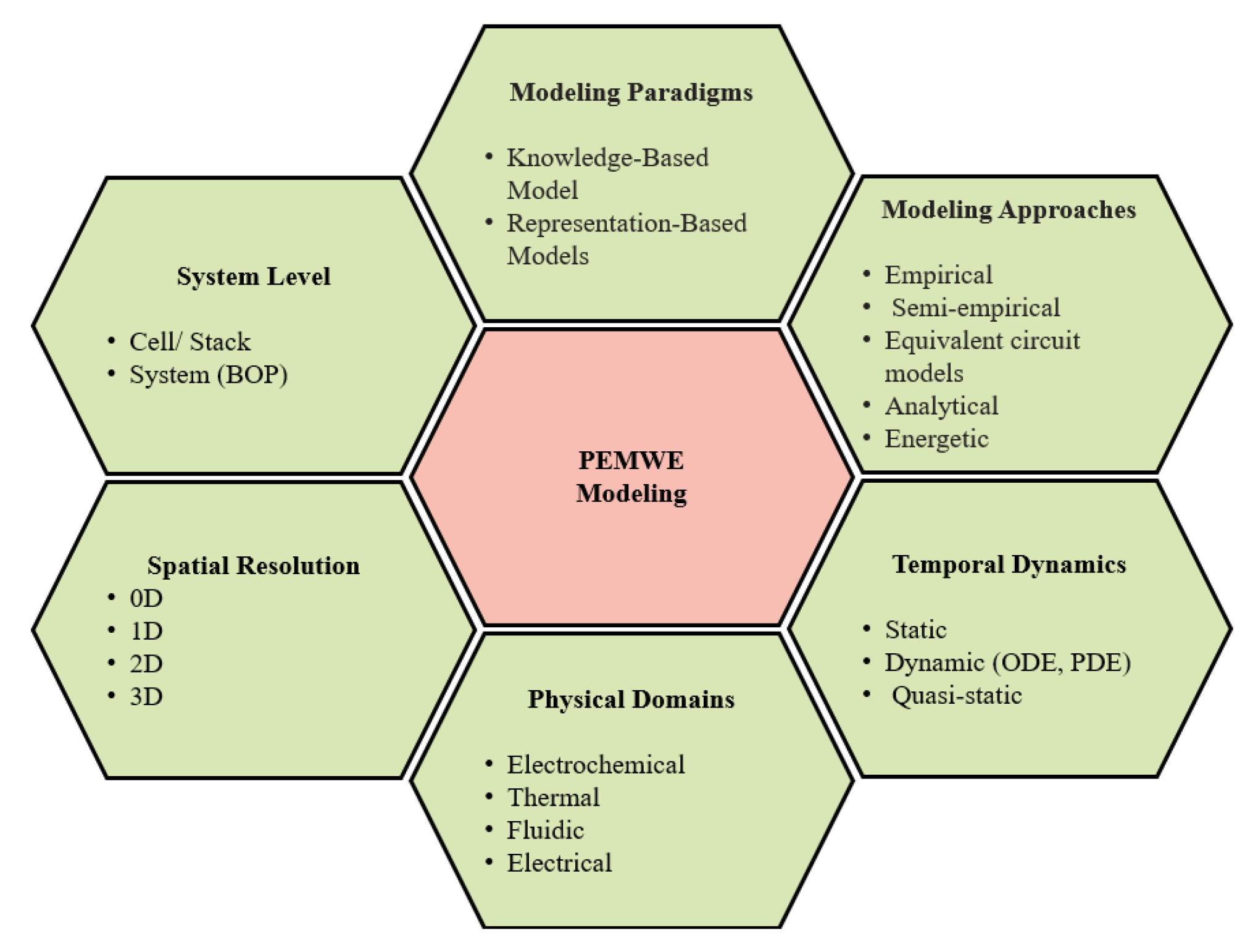

4.1. Modeling Paradigms

4.2. Modeling Approaches

4.3. Model Dynamics

4.4. System Level

4.5. Multiphysics Domains

4.6. Multidimensional Modeling

5. Integration of WE with Renewable Energy Sources and the Power Grid

5.1. Coupling with Renewable Energy Sources

5.2. Integration into the Power Grid

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEC | Alkaline Electrolyzer Cell |

| PEMEC | Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer Cell |

| AEMEC | Anion Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer Cell |

| SOEC | Solid Oxide Electrolyzer Cell |

| PEMWE | Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer |

| PFSA | PerFluorosulfonic acid membrane |

| BoP | Balance-of-Plant |

| EMS | Energy Management System |

| ESS | Energy Storage System |

| HIL | Hardware-In-the-Loop |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| PMC | Power Management Controller |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| SoC | State of Charge |

| HPAL | high-pressure acid leaching |

| YSZ | Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia |

| EIS | Electrochemical Impedence Spectroscopy |

| SDES | Short Duration Energy Storage |

| LDES | Long Duration Energy Storage |

| P2G | Power to Gas |

References

- Elalfy, D.A.; Gouda, E.; Kotb, M.F.; Bureš, V.; Sedhom, B.E. Comprehensive review of energy storage systems technologies, objectives, challenges, and future trends. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 54, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.; Said, A.; Saad, M.H.; Farouk, A.; Mahmoud, M.M.; Alshammari, M.S.; Alghaythi, M.L.; Aleem, S.H.A.; Abdelaziz, A.A.; Omar, A.I. A review of water electrolysis for green hydrogen generation considering PV/wind/hybrid/hydropower/geothermal/tidal and wave/biogas energy systems, economic analysis, and its application. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 87, 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, M.; Megahed, T.F.; Ookawara, S.; Hassan, H. A review of water electrolysis–based systems for hydrogen production using hybrid/solar/wind energy systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 86994–87018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Projet ROSTOCK-H. État des connaissances sur le stockage de l’hydrogène en cavité saline et apport du projet ROSTOCK-H. Rapport technique, France, 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382152344 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- David, M.; Ocampo-Martínez, C.; Sánchez-Peña, R. Advances in alkaline water electrolyzers: A review. J. Energy Storage 2019, 23, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavendish, H. Three Papers Containing Experiments on Factitious Air. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 1766, 56, 141–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoisier, A.L. Mémoire sur la Combustion en Général; Académie Royale des Sciences: Paris, France, 1783. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Research Service. Hydrogen: Production, Uses, and Policy Considerations. Technical Report; United States Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R48196 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Hydrogen Review. 2021. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2021 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ullah, I.; Amin, M.; Zhao, P.; Qin, N.; Xu, A.W. Recent advances in inorganic oxide semiconductor-based S-scheme heterojunctions for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 1329–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Zhao, P.; Qin, N.; Chen, S.; Li, J.H.; Xu, A.W. Emerging Trends in CdS-Based Nanoheterostructures: From Type-II and Z-Scheme toward S-Scheme Photocatalytic H2 Production. Chem. Rec. 2024, 24, e202400127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitta, S. Sustainability of hydrogen manufacturing: A review. RSC Sustain. 2024, 2, 3202–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuluhong, A.; Chang, Q.; Xie, L.; Xu, Z.; Song, T. Current Status of Green Hydrogen Production Technology: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I.; Acar, C. Review and evaluation of hydrogen production methods for better sustainability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 11094–11111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiffer, E.; Williams, R.; Ba-aoum, M.; Hudson-Heck, E.; Aranda, I. Evaluation of New Opportunities for Marine Energy to Power the Blue Economy: Green Hydrogen and Marine Carbon Dioxide Removal. Technical Report; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy24osti/89475.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Kumar, S.S.; Lim, H. An overview of water electrolysis technologies for green hydrogen production. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 13793–13813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Emerging Technologies Review: Carbon Capture and Conversion to Methane and Methanol; Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL): Richland, WA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.A. Renaissance of ammonia synthesis for sustainable production of energy and fertilizers. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 29, 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; He, L.; Jiang, L.; Jiang, S.; Yu, R.; Lau, H.C.; Xie, C.; Chen, Z. The role of hydrogen in the energy transition of the oil and gas industry. Adv. Appl. Energy 2024, 3, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, W.A. Apollo Experience Report: The Cryogenic Storage System. Technical Report; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1973. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19730017162/downloads/19730017162.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Emam, A.S.; Hamdan, M.O.; Abu-Nabah, B.A.; Elnajjar, E. A review on recent trends, challenges, and innovations in alkaline water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 64, 599–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, D.S.; Pinto, A.M. A review on PEM electrolyzer modelling: Guidelines for beginners. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qi, F.; Ren, R.; Gu, Y.; Gao, J.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Kong, X.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Recent Advances in Green Hydrogen Production by Electrolyzing Water with Anion-Exchange Membrane. Research 2025, 8, 0677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vostakala, M.F.; Ozcan, H.; El-Emam, R.S.; Horri, B.A. Recent Advances in High-Temperature Steam Electrolysis with Solid Oxide Electrolysers for Green Hydrogen Production. Energies 2023, 16, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.E. An Overview of Different Water Electrolyzer Types for Hydrogen Production. Energies 2024, 17, 4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trattner, A.; Höglinger, M.; Macherhammer, M.G.; Sartory, M. Renewable Hydrogen: Modular Concepts from Production over Storage to the Consumer. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2021, 93, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, R.; Bilgen, E.; Koca, A. Electrode modifications with electrophoretic deposition methods for water electrolyzers. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 81, 675–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flis, G.; Wakim, G. Solid Oxide Electrolysis: A Technology Status Assessment. Technical Report; Clean Air Task Force: Boston, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.catf.us/resource/solid-oxide-electrolysis-technology-status-assessment/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Aminaho, E.N.; Aminaho, N.S.; Aminaho, F. Techno-economic assessments of electrolysers for hydrogen production. Appl. Energy 2025, 399, 126515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Green Hydrogen Cost Reduction: Scaling up Electrolysers to Meet the 1.5°C Climate Goal; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020; ISBN 978-92-9260-295-6. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, S.; Koning, V.; de Groot, M.T.; de Groot, A.; Mendoza, P.G.; Junginger, M.; Kramer, G.J. Present and future cost of alkaline and PEM electrolyser stacks. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 32313–32330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younus, H.A.; Al Hajri, R.; Ahmad, N.; Al-Jammal, N.; Verpoort, F.; Al Abri, M. Green hydrogen production and deployment: Opportunities and challenges. Discov. Electrochem. 2025, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA); Bluerisk. Water for Hydrogen Production; International Renewable Energy Agency and Bluerisk: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Making the Breakthrough: Green Hydrogen Policies and Technology Costs; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IEAGHG. Analysis of Electrolytic Hydrogen Technologies with a Comparative Perspective on Low-Carbon (CCS-Abated) Hydrogen Pathways; IEAGHG: Cheltenham, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaya, N.; Gloser-Chahoud, S. A Review of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Studies for Hydrogen Production Technologies through Water Electrolysis: Recent Advances. Energies 2024, 17, 3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedrtnam, A.; Kalauni K, K.; Pahwa, R. Water Electrolysis Technologies and Their Modeling Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. Eng 2025, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, C.; Lavacchi, A.; Mustarelli, P.; Noto, V.D.; Elbaz, L.; Dekel, D.R.; Jaouen, F. What is Next in Anion-Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzers? Bottlenecks, Benefits, and Future. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202200027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebbahi, S.; Assila, A.; Belghiti, A.A.; Laasri, S.; Kaya, S.; Hlil, E.K.; Rachidi, S.; Hajjaji, A. A comprehensive review of recent advances in alkaline water electrolysis for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 82, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, M.; Müller, K.; Bensmann, B.; Hanke-Rauschenbach, R.; Aili, D.; Franken, T.; Chromik, A.; Peach, R.; Freiberg, A.T.S.; Thiele, S. Review and Prospects of PEM Water Electrolysis at Elevated Temperature Operation. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 9, 2300281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.H.A.; Tijani, A.S.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Hanapi, S. An overview of polymer electrolyte membrane electrolyzer for hydrogen production: Modeling and mass transport. J. Power Sources 2016, 309, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, M.; Fritz, D.L.; Mergel, J.; Stolten, D. A comprehensive review on PEM water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 4901–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, C. Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer: Electrode Design, Lab-Scaled Testing System and Performance Evaluation. EnergyChem 2022, 4, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiao, J.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Cao, B.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, B.; Wang, M. Materials and flow fields of bipolar plates in polymer electrolyte membrane water electrolysis: A review. Energy Rev. 2025, 4, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.; Torrubia, J.; Valero, A.; Valero, A. Non-Renewable and Renewable Exergy Costs of Water Electrolysis in Hydrogen Production. Energies 2025, 18, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikeng, E.; Makhsoos, A.; Pollet, B.G. Critical and Strategic Raw Materials for Electrolysers, Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 71, 433–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025. Technical Report; IEA: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2025 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Natural Resources Canada. Platinum Facts, 2025. Available online: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/minerals-mining/mining-data-statistics-analysis/minerals-metals-facts/platinum-facts (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Johnson Matthey. PGM Prices and Trading—PGM Management, 2025. Available online: https://matthey.com/products-and-markets/pgms-and-circularity/pgm-management (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Jiang, X.; Deng, C.; Niu, S.; Mao, J.; Zeng, W.; Liu, M.; Liao, H. Mechanism of corrosion and sedimentation of nickel electrodes for alkaline water electrolysis. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 303, 127806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.C.; Larrazábal, G.O.; Egelund, S.D.; Chatziaristodoulou, C. Nickel anode evolution and mass loss during intermittent alkaline water electrolysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 525, 169990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, R.A.; Bender, J.T.; Aleman, A.M.; Kalokowski, E.; Le, T.V.; Williamson, C.L.; Frederiksen, M.L.; Kawashima, K.; Chukwuneke, C.E.; Dolocan, A.; et al. Insights into catalyst degradation during alkaline water electrolysis under variable operation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 7170–7187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.; Moradizadeh, L.; Murugaiah, D.K.; Khalid, M.; Farooq Lala, S.R.; Shahgaldi, S. Exploring the degradation of catalyst layer and porous transport layer in proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers. EES Catal. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoulida, F.; Guilbert, D.; Camara, M.B.; Dakyo, B. Dynamic electrical degradation of PEM electrolyzers under renewable energy intermittency: Mechanisms, diagnostics, and mitigation strategies—A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 225, 116170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Chao, Y.; Tao, L.; Ji, H.; Lu, C.; Ke, C.; Zhuang, X.; Shao, J. Stability challenges of anion-exchange membrane water electrolyzers from components to integration level. Chem. Catal. 2024, 4, 1145–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Andrew, R.; Mortz, T.; Bae, C.; Fujimoto, C.Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, K.; Ayers, K.E.; Kim, Y.S. Durability of anion exchange membrane water electrolyzers. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 3393–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Hou, H.; Yuan, X.; Fu, Q.; Fang, R.; Liu, H.; Kong, J.; Wang, J. Understanding and resolving the heterogeneous degradation of anion exchange membrane water electrolysis for large-scale hydrogen production. Carbon Neutrality 2024, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Ma, L.; Li, W.; Liu, X. Degradation of solid oxide electrolysis cells: Phenomena, mechanisms, and emerging mitigation strategies—A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Xu, X.; Knibbe, R.; Zhu, Z. Air electrodes and related degradation mechanisms in solid oxide electrolysis and reversible solid oxide cells. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerrougui, I.; Li, Z.; Hissel, D. Toward optimal operations of long-lifetime PEM electrolysis: Degradation mechanisms, modeling, diagnostics, and control. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 193, 152297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallnöfer-Ogris, E.; Grümmer, I.; Ranz, M.; Höglinger, M.; Kartusch, S.; Raub, J.; Machhammerl, M.G.; Günther, B.; Trattner, A. A review on understanding and identifying degradation mechanisms in PEM water electrolysis cells: Insights for stack application, development, and research. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 65, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, E.; Pahon, E.; Yousfi-Steiner, N.; Guillou, M. Accelerated stress testing in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis—Critical review. J. Power Sources 2024, 623, 235451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarteroni, A.; Gervasio, P.; Regazzoni, F. Combining physics-based and data-driven models: Advancing the frontiers of research with Scientific Machine Learning. Math. Model. Methods Appl. Sci. (M3AS) 2025, 35, 905–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Kim, N.H.; Choi, J.H. Practical options for selecting data-driven or physics-based prognostics algorithms with reviews. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2015, 133, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbli, K.S.; Péra, M.C.; Hissel, D.; Rallières, O.; Turpin, C.; Doumbia, I. Multiphysics simulation of a PEM electrolyser: Energetic Macroscopic Representation approach. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 1382–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, S.; Prakash, O.; Boukerdja, M.; Dieulot, J.Y.; Ould-Bouamama, B.; Bressel, M.; Gehin, A.L. Generic Dynamical Model of PEM Electrolyser under Intermittent Sources. Energies 2020, 13, 6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, P.; Bourasseau, C.; Bouamama, B. Low-temperature electrolysis system modelling: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmehel, A.; Chabch, S.; Do Nascimento Rocha, A.L.; Chepy, M.; Kousksou, T. PEM water electrolyzer modeling: Issues and reflections. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 24, 100738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-López, M.; Darras, C.; Poggi, P.; Glises, R.; Baucour, P.; Rakotondrainibe, A.; Besse, S.; Serre-Combe, P. Modelling and experimental validation of a 46 kW PEM high pressure water electrolyzer. Renew. Energy 2018, 119, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louli, R.; Giurgea, S.; Salhi, I.; Badji, A.; Laghrouche, S.; Li, Z.; Djerdir, A. Optimized Multiphysics Model for a Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer. Renew. Energy 2025, 256, 124452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, Z.; Li, H.; Yang, B.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, T.; Jin, L.; Zhang, C. Optimization of alkaline electrolyzer operation in renewable energy power systems: A universal modeling approach for enhanced hydrogen production efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louli, R.; Chabane, D.; Giurgea, S.; Salhi, I.; Djerdir, A. A 3D Multiphysics Study of Different Channel Designs of PEM Electrolyzer. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC), Washington, DC, USA, 7–10 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salaberri, P.A. 1D two-phase, non-isothermal modeling of a proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer: An optimization perspective. J. Power Sources 2022, 521, 230915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Zausch, J. 1D multiphysics modelling of PEM water electrolysis anodes with porous transport layers and the membrane. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 253, 117600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubras, F.; Deseure, J.; Kadjo, J.A.; Dedigama, I.; Majasan, J.; Grondin-Perez, B.; Chabriat, J.; Brett, D.J.L. Two-dimensional model of low-pressure PEM electrolyser: Two-phase flow regime, electrochemical modelling and experimental validation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 26203–26216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Ouyang, T.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Qin, C.; Ye, D.; Chen, R.; Zhu, X.; et al. Progresses on two-phase modeling of proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer. Energy Rev. 2024, 3, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wu, L.; Bao, Z.; Zu, B.; Jiao, K. A 3-D multiphase model of proton exchange membrane electrolyzer based on open-source CFD. Digit. Chem. Eng. 2021, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahir, O.; Aboduraz, I.; Arjdla, E.H.; Elyaqouti, M.; Mellouli, E.M.; Souaid, F.E.; Maiall, S. Improved ADRC-based control of industrial alkaline electrolyzers for green hydrogen production in PV-battery microgrids. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 190, 151925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.; Raźniak, A.; Sada, U.M.; Iliev, I.; Markowski, J.; Dudek, P. Investigations of an Off-Grid System Based on a Hybrid Photovoltaic and Wind Turbine System with Integrated Hydrogen Production Located in Poland. E3S Web Conf. 2025, 638, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.; Raźniak, A.; Markowski, J.; Sada, U.M.; Iliev, I. Technical Assessment of Green Hydrogen Production in Anion Exchange Membrane Electrolyzers Integrated with Off-Grid Renewable Energy Systems at Different Scales. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Communications, Information, Electronic and Energy Systems (CIEES), Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louli, R.; Badji, A.; Giurgea, S.; Salhi, I.; Laghrouche, S.; Djerdir, A. Energy Management of a Green Hydrogen Production Autonomous System. In Proceedings of the International Conference Electrical Systems and Automation (ICESA), Troyes, France; Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zong, Y.; You, S.; Træholt, C. Economic model predictive control for multi-energy system considering hydrogen-thermal-electric dynamics and waste heat recovery of MW-level alkaline electrolyzer. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 265, 115697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, Y.; Sun, Z.; Peng, Y. A predictive control method for multi-electrolyzer off-grid hybrid hydrogen production systems with photovoltaic power prediction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 84, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urhan, B.B.; Erdoğmuş, A.; Şakir Dokuz, A.; Gökçek, M. Predicting green hydrogen production using electrolyzers driven by photovoltaic panels and wind turbines based on machine learning techniques: A pathway to on-site hydrogen refuelling stations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 101, 1421–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.D.; Martínez, L.A.; Peña, R.R.; Mantz, R.J. Electrolyzers as smart loads, preserving the lifetime. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuinema, B.W.; Adabi, E.; Ayivor, P.K.; García Suárez, V.; Liu, L.; Perilla, A.; Ahmad, Z.; Rueda Torres, J.L.; van der Meijden, M.A.; Palensky, P. Modelling of large-sized electrolysers for real-time simulation and study of the possibility of frequency support by electrolysers. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 1985–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Haas, M.; Elliot, I.; Nazari, S. Control and control-oriented modeling of PEM water electrolyzers: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 30621–30641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monopoli, D.; Semeraro, C.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Alalami, A.H.; Olabi, A.G.; Dassisti, M. How to build a Digital Twin for operating PEM-Electrolyser system—A reference approach. Annu. Rev. Control 2024, 57, 100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.S.; Rituraj, G.; Bauer, P.; Vahedi, H. Real-time digital twin implementation of power electronics-based hydrogen production system. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 5006–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruuskanen, V.; Koponen, J.; Huoman, K.; Kosonen, A.; Niemelä, M.; Ahola, J. PEM water electrolyzer model for a power-hardware-in-loop simulator. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 10775–10784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.; Ko, R.; Ha, D.; Han, J. Development of Model-Based PEM Water Electrolysis HILS (Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation) System for State Evaluation and Fault Detection. Energies 2023, 16, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Production Method | Primary Energy Source | Environmental Characteristics | Color Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steam methane reforming (SMR) without carbon capture | Natural gas (CH4) | High emissions | Grey |

| Steam methane reforming with CCS (SMR + CCS) | Natural gas (CH4) | Lower emissions, not carbon-neutral | Blue |

| Coal gasification | Coal | Very high carbon footprint | Black or Brown |

| Methane pyrolysis | Natural gas | Produces solid carbon instead of | Turquoise |

| Water electrolysis (renewable electricity) | Wind, solar, hydroelectric power | Low or zero emissions | Green |

| Water electrolysis (fossil-based electricity) | Coal, gas, or mixed grid | Depends on electricity source; often high emissions | Yellow or Grey |

| Water electrolysis (powered by nuclear energy) | Water + Nuclear | Low emissions; depends on nuclear lifecycle impacts | Purple or Pink |

| Biomass reforming/gasification | Organic waste, agricultural residues | Can be carbon-neutral if sustainably sourced | Orange |

| Natural (geologic) hydrogen | Underground reservoirs (natural/geological) | Potentially renewable, very low emissions (emissions from extraction only) | White or Gold |

| Methane pyrolysis | Natural gas | Solid carbon byproduct; depends on process energy source | Turquoise |

| Material | Main Producers | Extraction Methods | Indicative Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel (Ni) | Indonesia, Philippines, New Caledonia, Canada, Russia, Australia | Laterites via HPAL (high-pressure acid leaching); sulfide ores via flotation then electrorefining | ∼ USD /g |

| Cobalt (Co) | Democratic Republic of the Congo (mainly; byproduct of Ni/Cu), Canada, Russia | Byproduct recovery: solvent extraction, precipitation, electrowinning | ∼ USD /g |

| Platinum (Pt) | South Africa, Russia, Canada | Complex PGM refining: aqua regia dissolution and selective precipitation | ∼ USD 45/g (2025) |

| Iridium (Ir) | South Africa, Russia (very low global output, ∼8 t/yr) | PGM byproduct; selective refining; notable corrosion/heat resistance | > USD 160/g |

| Titanium (Ti) | Australia, South Africa, Canada | From ilmenite/rutile; chlorination followed by the Kroll process | < USD /g |

| Graphite (natural/synthetic) | China, Brazil, Canada | Natural: mining; Synthetic: high-temperature treatment of carbon-rich precursors; ultra-high-purity requires costly purification | Variable (UHP grades higher) |

| Nafion® (PFSA) | (commercial membrane) | Proton-conducting PFSA membrane for acidic environments; specialized membrane fabrication | ∼ USD 2000/m2 |

| Model | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0D | Represents the system using lumped global balances without any spatial resolution. | Very fast computation, suitable for real-time use, simple parameter identification. | Cannot describe spatial heterogeneities, unable to capture local transport limits or flooding/dry-out phenomena. | Control-oriented modeling, EMS integration, HIL/PHIL testing, system-level studies. |

| 1D | Resolves through-plane variations across the MEA, including ionic/electronic potentials, species transport, and temperature. | Captures the dominant electrochemical and thermal mechanisms with moderate computational cost. | Assumes in-plane uniformity; cannot reproduce channel effects, flow-field influence, or lateral gradients. | MEA-level analysis, parametric studies, and development of reduced-order models. |

| 2D | Introduces in-plane spatial resolution, enabling the representation of channel-level gradients and flow-field effects. | Predicts in-plane heterogeneities, useful for flow-field analysis. | Still simplified, transient 2D expensive, limited validation. | Flow-field optimization, local current density analysis. |

| 3D | Fully resolves the three-dimensional geometry and all coupled multiphysics phenomena (electrochemical, thermal, fluidic, and two-phase transport). | Highest spatial fidelity; captures hotspots, flow maldistribution, bubble dynamics, and detailed channel/porous-media interactions. | Extremely high computational cost; requires advanced meshing and HPC resources, not suitable for control, real-time simulation, or large-scale system studies. | Cell and flow-field design, diagnostic analysis, two-phase flow characterization, and scale-up investigations. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Louli, R.; Giurgea, S.; Salhi, I.; Laghrouche, S.; Djerdir, A. A Critical Review of Green Hydrogen Production by Electrolysis: From Technology and Modeling to Performance and Cost. Energies 2026, 19, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010059

Louli R, Giurgea S, Salhi I, Laghrouche S, Djerdir A. A Critical Review of Green Hydrogen Production by Electrolysis: From Technology and Modeling to Performance and Cost. Energies. 2026; 19(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleLouli, Rafika, Stefan Giurgea, Issam Salhi, Salah Laghrouche, and Abdesslem Djerdir. 2026. "A Critical Review of Green Hydrogen Production by Electrolysis: From Technology and Modeling to Performance and Cost" Energies 19, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010059

APA StyleLouli, R., Giurgea, S., Salhi, I., Laghrouche, S., & Djerdir, A. (2026). A Critical Review of Green Hydrogen Production by Electrolysis: From Technology and Modeling to Performance and Cost. Energies, 19(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010059