1. Introduction

The importance of power electronic converters is globally increasing year after year because of the widespread usage of renewable energy sources (RES), energy storage systems (ESS), Electric Vehicles (EVs), consumer electronics, aerospace and defense, and massive electrification of manufacturing structures [

1,

2,

3]. Due to particular electric requirements across different applications, a significant amount of generated or consumed power needs are expected to be processed using some type of power electronic converter [

4,

5]. Many power electronic converter topologies are only able to provide unidirectional power flow according to the application requirements. Nevertheless, in a worldwide search for clean and renewable power sources and energy efficiency, because of the climate and energy crisis, the demand for advancing the development of converter topologies with bidirectional power flow capabilities has become increasingly imperative. This is particularly important in the transportation sector, where bidirectional power flows enable the application of traction and energy recovery during various routes, thereby optimizing energy resources [

6,

7]. This aspect is also crucial in the energy sector, where the effective implementation of local or decentralized smart-grids or microgrids is only possible due to power electronic converters with the ability to provide the bidirectional power transfer feature [

8,

9]. Furthermore, it is common to employ power electronic converters for auxiliary purposes, such as ensuring voltage stability and equalization, load regulation, compensating for reactive power and harmonics, or implementing filtering capabilities, among other possibilities [

10,

11].

Several bidirectional isolated and non-isolated types of power electronic converter topologies have been proposed for several

AC and

DC applications over the last years [

12,

13]. Regarding isolated bidirectional

DC-DC converters, some of the most popular topologies are the bidirectional Dual Active Bridge (

DAB), Flyback, Cuk or Sepic/Zeta, Push-Pull, Forward, and resonant converters [

14,

15]. Most of those topologies are also obtained from traditional isolated

DC-DC converters. Despite their higher cost, isolated topologies typically offer two power conversion stages with galvanic separation through a high-frequency transformer [

16,

17,

18]. This will lead to converters that have a higher component count and cost, exhibiting increased size and weight. In fact, high power density cannot be expected from isolated

DC-DC converters due to their capacitive, magnetic, and thermal management components [

19]. The number of power devices can be relatively significant in some isolated DAB topologies. However, DAB is an established topology known for its high-voltage gain capability [

20,

21,

22]. Thus, in solutions that require galvanic isolation, this converter is one of the most important options [

23]. It is important to mention that the DAB topology is not inherently limited to isolated versions [

24,

25,

26]. In a non-isolated configuration, for example, the two active bridges and the transformer can be replaced with two active bridges connected directly through a single inductor. This structure still preserves the fundamental operating principle of the DAB: transferring power by controlling the phase shift between the square-wave voltages generated by the two active bridges across the inductor.

Regarding non-isolated bidirectional

DC-DC converters, most known topologies were derived from traditional unidirectional

DC-DC converters. This type of converter, on the other hand, features simpler designs, a smaller size, higher power density, and control systems compared to isolated topologies, making them suitable for applications where isolation is not required [

20]. Indeed, they can be used in battery-powered devices, intermediate bus architectures, automotive electronics, telecom/datacom applications, and for boosting or lowering voltage within a common ground system. References [

27,

28,

29,

30] contain information on several well-known bidirectional non-isolated

DC-DC converters. These include the Buck-Boost, Cuk, Sepic/Zeta, switched-capacitor, interleaved and coupled-inductor topologies, and others. Typically, devoid of high-frequency isolation transformers, these

DC-DC converters are characterized by their simplicity and low cost. A comprehensive assessment of bidirectional non-isolated

DC-DC converters featuring operation in

ZVS (Zero Voltage Switching) or in ZCS (Zero Current Switching) can be found in [

29]. Other modified topologies have been developed and presented over the last years based on those topologies, such as cell modified/hybrid switched-capacitor converters [

31,

32,

33], soft-switching current fed

LCL resonant converters [

34], soft-switching coupled-inductor converters [

35], and other modified topologies derived from the conventional Buck-Boost converter [

36,

37]. Those topologies are commonly used in low or medium power applications where safety concerns are not critical. Another focal aspect is the development of topologies with wide voltage gain, as shown, for example, in [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Most of these topologies are modified versions of the traditional bidirectional

DC-DC converters, incorporating supplementary active and passive components. On the other hand, it should be noted that most of these converters offer step-down gain in forward power transfer and step-up gain in the reverse direction.

Multilevel bidirectional non-isolated

DC-DC topologies can also be found in the literature, such as the flying capacitor based multilevel

DC-DC converters (

FCMDC) [

45], the multilevel modular capacitor clamped

DC-DC converter (

MMCCC) [

46], or bidirectional three-level cascaded (

BTLC) converter [

47]. Compared to the abovementioned non-multilevel converters, the magnetic-less flying or modular capacitor-based multilevel

DC-DC present several advantages, including a reduced component count (switching devices and capacitors), lower voltage stress on power devices, and higher voltage gains. Still, these multilevel converters do have limited and unsymmetrical step-up and step-down conversion ratios. Certain multilevel solutions can achieve a continuous voltage gain range by adjusting the duty cycle. However, the control is complex, and the continuous range is limited due to significant dependency on parasitic resistance in the capacitor’s charging and discharging paths, as well as on the switching frequency. Furthermore, these multilevel converters exhibit pulsed input/output currents, which significantly diminish the lifespan of energy storage systems or energy sources [

45]. Despite the multiple available solutions, there is still a need in most applications to develop new bidirectional

DC-DC converters offering high-voltage gain and bidirectional variable range at a reduced component count. This requirement justifies ongoing research and development efforts in this field. A drawback of these converters is that a significant number of switches and passive components are typically needed when relatively high-voltage gains are required. Consequently, there is also a requirement to develop converters that can achieve high-voltage gain with reduced component counts.

In this paper, a novel bidirectional DC-DC converter is introduced, featuring high-voltage gain while reducing the switch and passive component count. The proposed topology is well-suited for applications needing bidirectional power flow and adjustable voltage range in both directions. One of the key characteristics of the proposed topology is its ability to operate in a bidirectional Buck-Boost mode, simultaneously offering continuous input and output current. This feature proves to be advantageous for numerous applications, including RES and ESS. To validate the hereafter theoretical assumptions, this paper presents several experimental results obtained from a laboratory prototype. These results show the performance effectiveness of the proposed converter.

2. Operation and Analysis of the Proposed Bidirectional DC-DC Converter

With Boost characteristics in reverse power flow and Buck characteristics in forward power flow, existing bidirectional

DC-DC converters need cascaded structures to achieve high-voltage gain, which raises the number of switches and passive components and reduces efficiency. Consequently, a new bidirectional

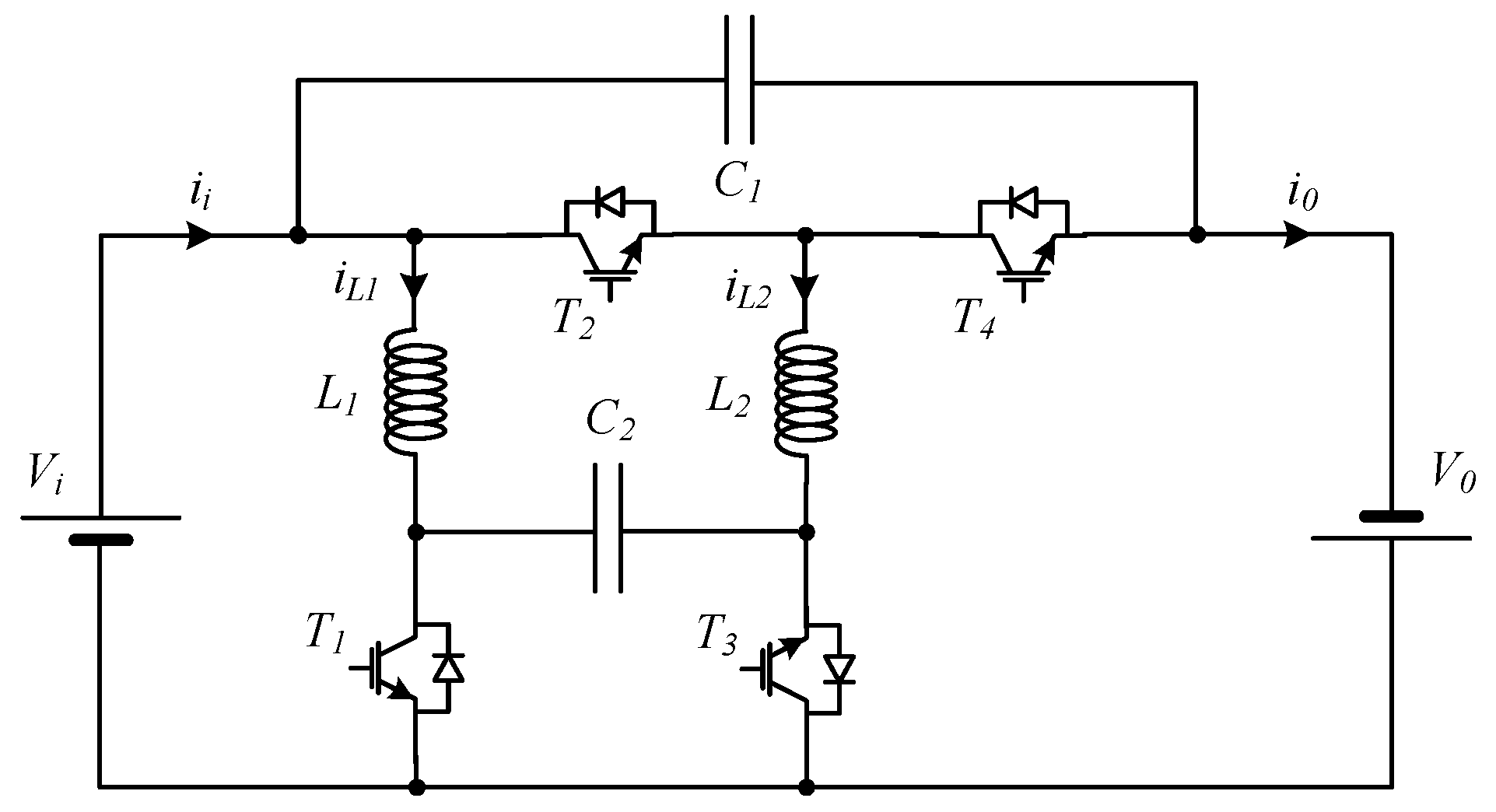

DC-DC converter is proposed in this paper with the goal of enabling Buck-Boost characteristics in both power flow directions while maintaining the simplicity and low component count of a single structure. The proposed structure only needs four transistors with antiparallel diodes, two inductors, and two capacitors, as shown in

Figure 1. Due to the type and quantity of passive components, this converter is based on a

2L2C structure. It should be noted that the continuous currents in the input and output terminals (

Vi and

Vo) are also a key feature of the proposed converter.

The power semiconductors will be assumed to be ideal, and the series resistances of the inductors, capacitors and voltage sources will be assumed to be zero, helping to analyze and calculate the appropriate relationships between the converter input and output. The source/output capacitor voltages Vi and Vo are also considered constants.

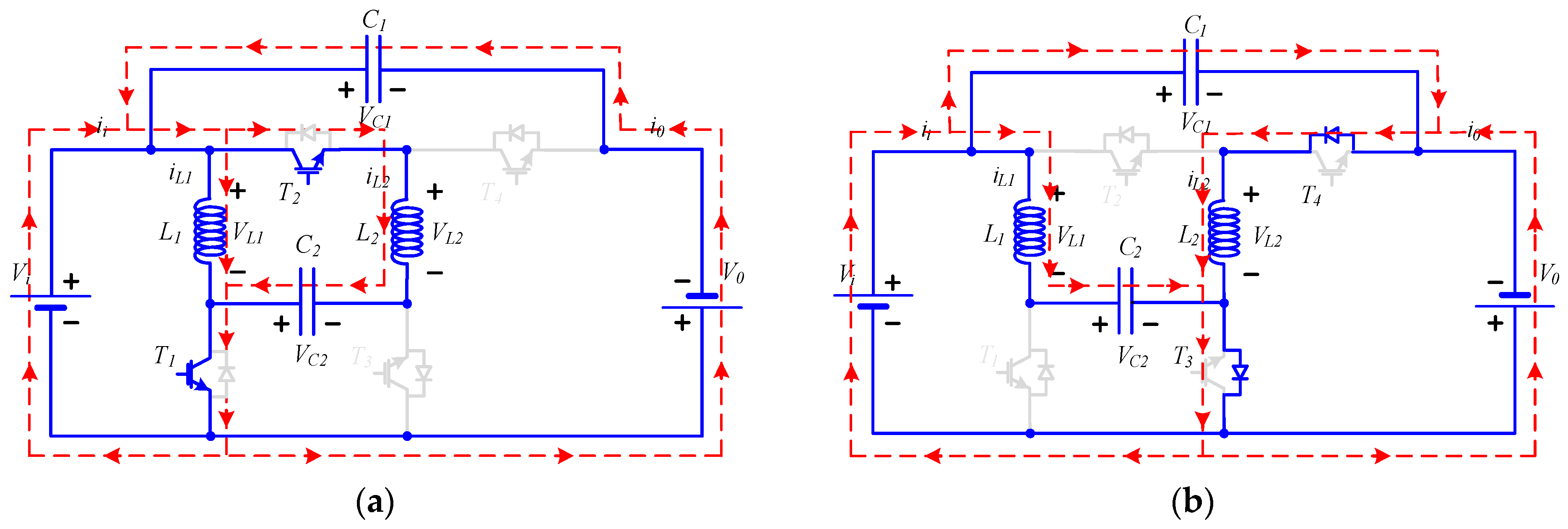

2.1. Forward Energy Transfer Operation

When power is transferred from the

Vi input to the

Vo output (forward transfer mode), the operation of the proposed

DC-DC converter with bidirectional Buck-Boost mode is characterized by two modes. During Mode 1, transistors

T1 and

T2 are turned

ON, and all other power semiconductors are turned

OFF (

Figure 2a). During Mode 2, diodes

D3 and

D4 are in

ON state and all other power semiconductors are turned

OFF (

Figure 2b). Considering that the converter should operate in the continuous conduction mode (

CCM), in steady state the converter operation and timing in Modes 1 and 2 can be described as:

Mode 1—The control signal for transistors T1 and T2 is δi-o (t) = 1, meaning that T1 and T2 are in the ON state while the remaining semiconductors are all in the OFF state. Therefore, both inductors will be charged by the input voltage source Vi and capacitor C2. Capacitor C1 will release energy into the load.

Mode 2—The control signal for transistors T1 and T2 is δi-o (t) = 0, meaning all power transistors are turned OFF, while only diodes D3 and D4 are conducting (ON state). As a result, the energy stored in the inductors will be released to the capacitor C2, the load, and C1.

To obtain the static voltage gain of the converter, the volt-second balance principle will be applied to the inductors [

48]. Thus, the average voltage across the inductor (

L) over one switching cycle must be zero, which means that:

In this way, by applying this principle to the inductors

L1 and

L2 and considering Modes 1 and 2 (see the voltages applied to the inductors in

Figure 2), we have a positive voltage during the

δi-o TS and a negative voltage during (1 −

δi-o)

TS. This can be expressed as follows:

where

δi-o represents the converter duty cycle in the forward energy transfer (

δi-o = 〈

δi-o (

t)〉). From (2), the intermediate capacitor voltage

C2 can be determined as:

Combining Expressions (3) and (4), the static voltage gain of this bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter, operating in the forward energy transfer mode, is given as:

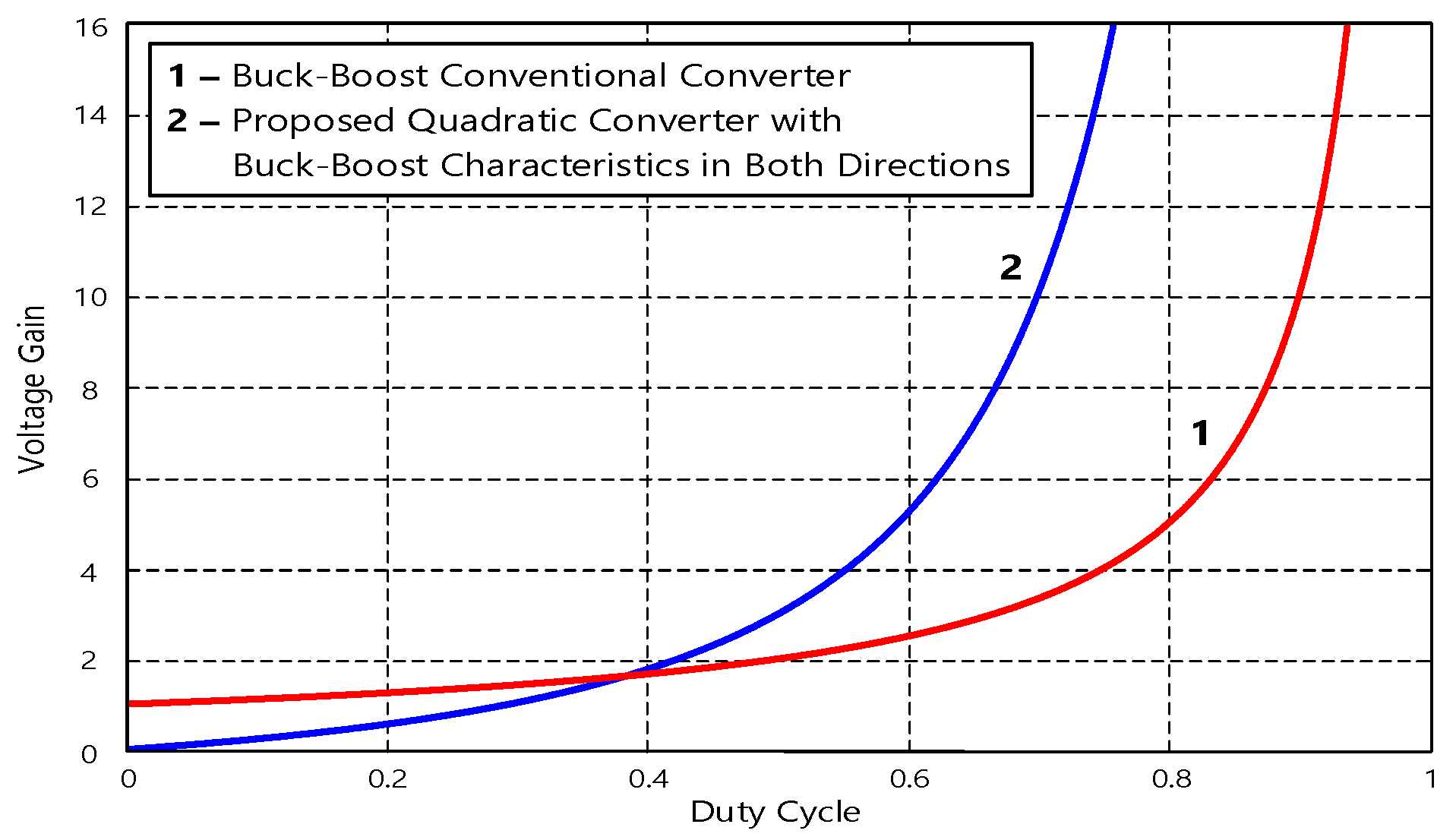

It is clear from the analysis of the output/input static voltage gain in Expression (5) that the proposed bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter, in the forward energy transfer mode, can be operated in either the Buck or in the Boost regions. Additionally, Expression (5) shows that the proposed bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter can present high-voltage gains, due to the quadratic

δi-o term. This is illustrated in

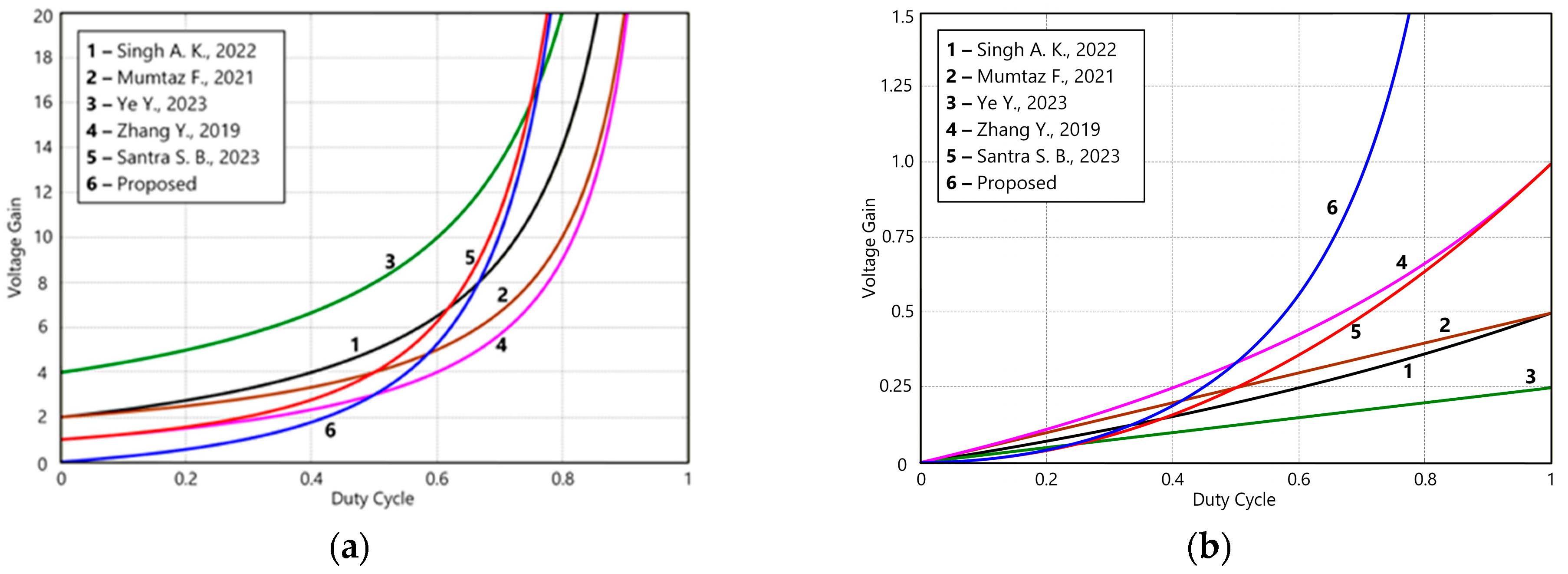

Figure 3, which compares the voltage gains of the present converter and the conventional bidirectional Buck-Boost converter. The figure clearly shows that the conventional bidirectional Buck-Boost converter is limited to Boost operation when energy is transferred from input to output. Conversely, the proposed converter supports Buck-Boost mode operation.

2.2. Reverse Energy Transfer Operation

In this operation mode, power is transferred from the

Vo output to the

Vi input (reverse transfer mode). In this scenario, transistors

T3 and

T4 will be turned

ON during Mode 1, with all other power semiconductors turned

OFF (

Figure 4a). During Mode 2, diodes

D1 and

D2 are

ON and all other power semiconductors are

OFF (

Figure 4b). The converter operation in reverse energy transfer and timing in Modes 1 and 2 can be described as:

Mode 1—The control signal for transistors T3 and T4 is δo-t (t) = 1, meaning that T3 and T4 are turned ON, while the remaining semiconductors are turned OFF. Therefore, both inductors will be charged by the bus (Vo) and capacitor C2. On the other hand, capacitor C1 will discharge to the input side and inductor L2.

Mode 2—In this second operation mode, the power diodes D1 and D2 are turned ON, while all other power semiconductors will be turned OFF. In this way, the energy that was stored in the inductors will be released to the input power source, capacitors C1 and C2.

Supposing

CCM and steady state, the volt-second balance on the inductors

L1 and

L2, considering the reverse energy transfer Modes 1 and 2, gives:

where

δo-t (

δo-t = 〈

δo-t (

t)〉) is the converter duty cycle in the reverse energy transfer. From (6), the intermediate capacitor

C2 voltage is written as:

Thereby, from the expressions in (6), the static voltage gain of this bidirectional Buck-Boost

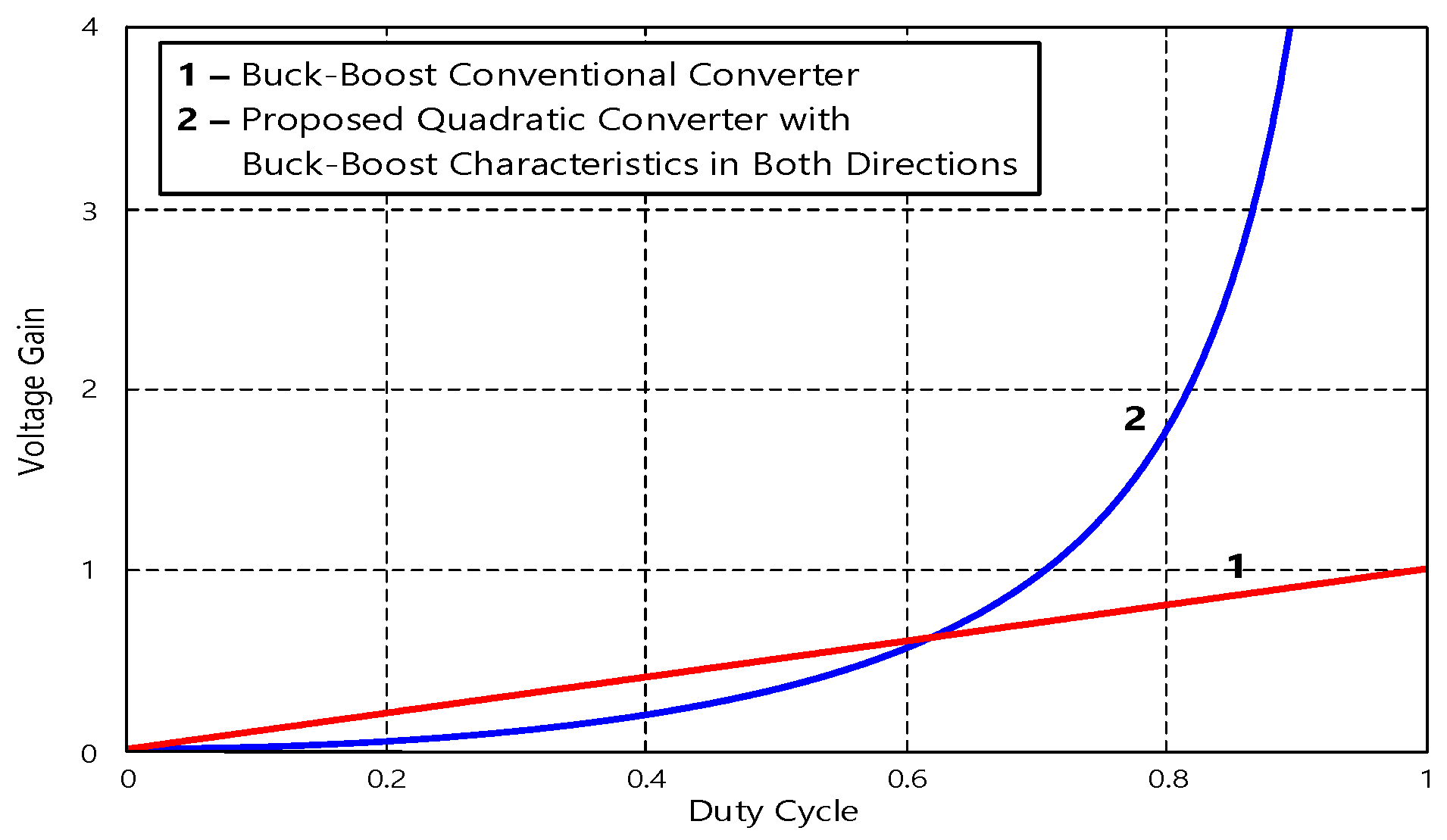

DC-DC converter, operating in the reverse energy transfer mode, is given as:

Expression (9) shows that the static voltage gain of the input and output in the reverse energy transfer mode exhibits Buck-Boost characteristics with high gain as well (

Figure 5). For comparison, the input-output static voltage gain of the conventional Buck-Boost converter is also shown in

Figure 5. As in the previous case, this figure shows the limitations of the conventional bidirectional Buck-Boost converter, as it only operates in Buck mode when energy is transferred from output to input. In contrast, the proposed converter allows for Buck-Boost mode operation.

4. Comparison to Similar Topologies

In this section, a comparative study is carried out to evaluate the benefits and drawbacks of the proposed non-isolated bidirectional

DC-DC converter. Several aspects are considered as a basis for comparison, including voltage gain in forward and reverse energy transfer operation, control complexity, maximum voltage and current stress, the number of power switches, capacitors, inductors, and coupled inductors.

Table 1 contains the summary of this comparative study. One feature that can be seen in

Table 1 is that the proposed topology allows for a wide voltage gain range in both directions. It is also distinguished by its low control complexity, as only the duty cycle needs to be adjusted. Additionally, it is one of the topologies that require the least number of passive components, when compared to other solutions. In this comparison, the control complexity is related with the modulation adopted and requirement of multiple switching stages to achieve ZVS or the multiple combination of power devices. Also, the control complexity of the converters is considered high when specific designed blocks are required, or they need independent control loops (for power sharing, voltage, current, etc.), increasing the number of interacting control variables, or even when they require advanced control strategies (e.g., decoupling, multi-variable control, or model predictive control).

To analyze the static voltage gain versus duty cycle between the proposed and the other bidirectional Buck-Boost converters described in

Table 1,

Figure 6 presents a chart illustrating this relation for both forward and reverse energy transfer operations. Thus, analyzing

Figure 6a for the forward energy transfer mode, it is evident that the proposed topology ranks as the one with the highest static voltage gain. However, when compared to the topology with the highest static voltage gain, it is possible to see that the proposed design exhibits Buck-Boost characteristics, while the other does not. Additionally, beyond this characteristic, the proposed design also presents a wider range. On the other hand, analyzing the reverse energy transfer mode shown in

Figure 6b, it is evident that it is one of the top configurations allowing for greater reduction due to the quadratic gain. The topology that presented higher static voltage gain in the forward energy transfer operation, does not present a reduction as high as the one proposed in Buck mode. On the other hand, the proposed topology still presents Buck-Boost characteristics, even in this reverse energy transfer mode.

5. Simulation Tests

Several simulation tests under different operating conditions were performed on a computer simulation platform to validate the theoretical assumptions. The proposed bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter was implemented in PLECS

® simulation software Version 4.9.8.

Table 2 shows the parameters of the converter components as well as the operation specifications adopted in the simulation. It is important to mention that, as previously verified, the adopted switching frequency is a function of the design of the components. In this case, optimization was not performed, as the objective is to validate the proof of concept.

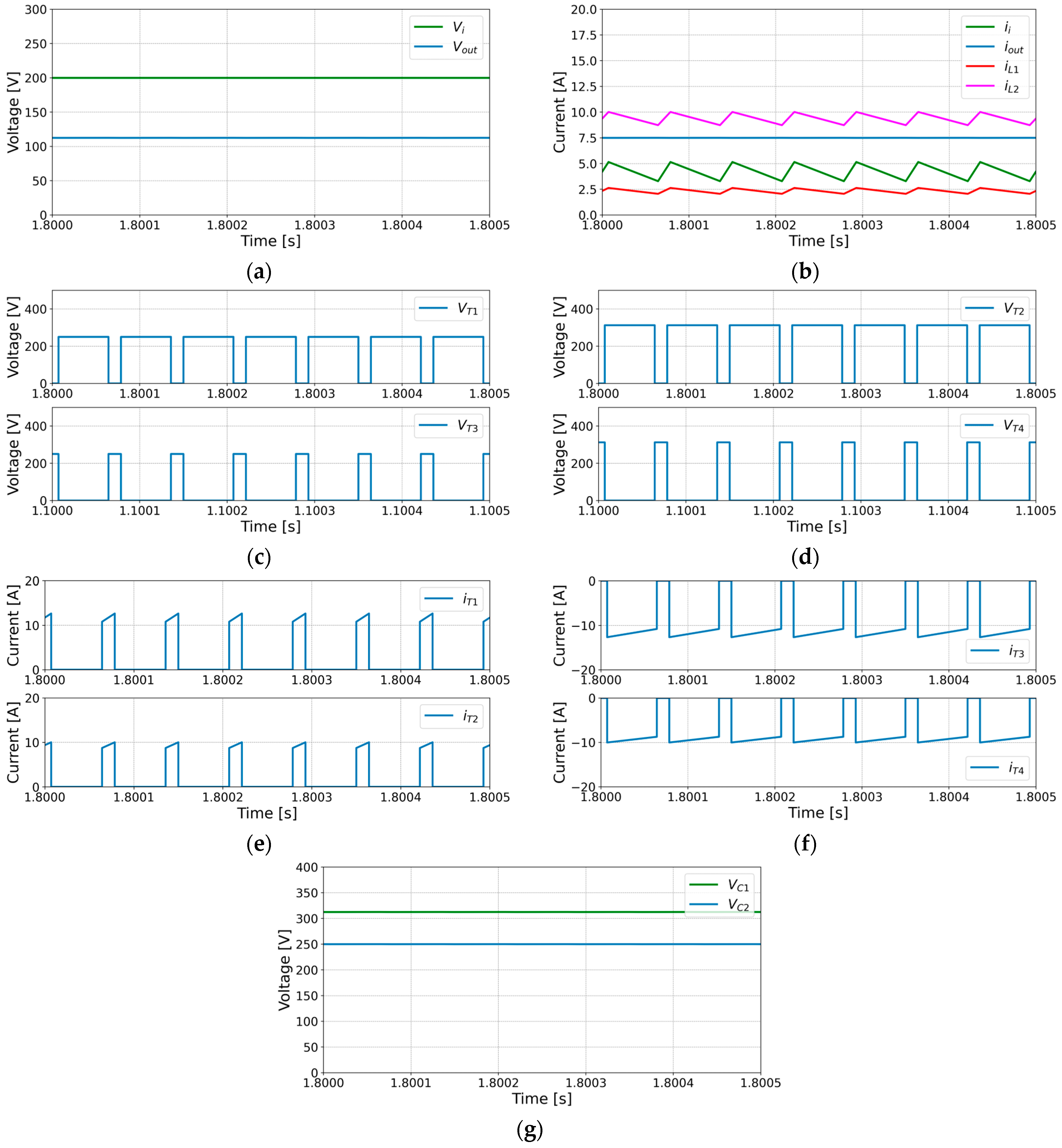

In the first set of simulations, the proposed bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter topology was simulated in forward energy transfer mode. The waveforms obtained from this test in steady state and for the operation specifications of

Table 2 can be seen in

Figure 7. For this test, a duty cycle of 0.67 was used for transistors

T1 and

T2.

Figure 7a illustrates that the input and output voltages show agreement with the converter parameters and duty cycle of the transistors

T1 and

T2, in accordance with the voltage gain given by Equation (5). Moreover, the input current presents no discontinuities (continuous current,

Figure 7b. This is an important feature in applications where the input contains an energy storage battery, for example. Another advantage is that the output current is also continuous. The current inductors can also be seen in

Figure 7b, illustrating their continuous waveforms. The transistors

T1 and

T2 voltage waveforms are also shown in

Figure 7c,d, confirming that the transistor

T2 must withstand the output voltage, while transistor

T1 must withstand a much lower voltage. It is also possible to observe that

T1 and

T2 operate synchronously, as the transistor voltage waveforms illustrate. The currents through the transistors are also shown in

Figure 7e. Since only transistors

T1 and

T2 operate in this mode, the currents in the other transistors flow through their internal diodes. As a result, they show negative values, as illustrated in

Figure 7f These waveforms confirm that the transistor with the highest current is

T1. The voltages across the capacitors are also displayed in

Figure 7g. These waveforms show that capacitor C1 experiences the most voltage stress, while capacitor C2 experiences significantly reduced voltage stress.

As mentioned in the study of the proposed DC-DC converter, one of its characteristics is its capability to operate in Buck-Boost mode in both directions. Thus, another simulation test was performed to verify this operability.

Figure 8 shows the results obtained under conditions where the duty cycle is 0.2 and the input voltage is 120 V. From this figure, it is possible to see that, contrary to the previous test, the circuit now operates in Buck condition. The behavior of the voltages across the transistors and the currents through them is similar, as verified by the previous test. The same applies to the voltage stress across the capacitors, confirming that it is again higher for capacitor

C1.

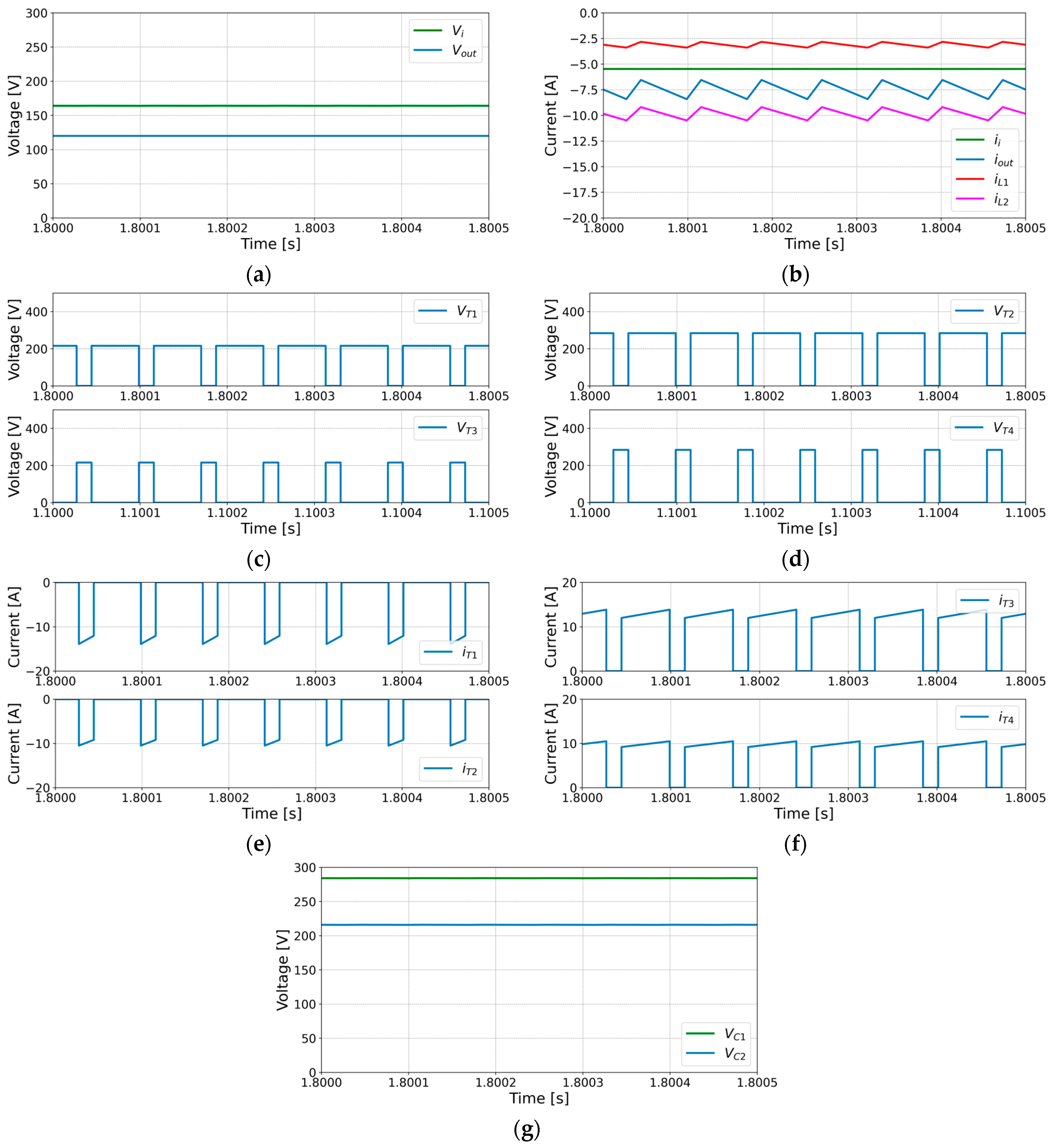

Simulations with the bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter operating in reverse energy transfer mode were also performed, using the same converter parameters listed in

Table 2.

Figure 9 shows the waveforms obtained for these tests in steady state and with a duty cycle of 0.33. When seen from the converter output (

Vo) side to the input (

Vi) side, a high-voltage gain reduction is noticed (see

Figure 9a). The current injected into the input voltage source remains continuous, indicating that this converter is suitable for battery applications or other applications requiring continuous currents. The current at the output terminals is also continuous, as are the currents in the inductors. The inversion of the currents presented in

Figure 9b indicates the reverse energy transfer mode. The blocking voltages in transistors

T3 and

T4 are also visible, showing that transistor

T3 needs to withstand a lower voltage while transistor

T4 needs to withstand a higher voltage, namely the capacitor

C1 voltage. The current waveforms in all the transistors and voltage over capacitors are available in

Figure 9e–g.

Additional simulation tests were performed to confirm the Buck-Boost characteristic of this converter in reverse energy transfer mode.

Figure 10 shows the results obtained for the condition in which the duty cycle is 0.67. From this figure, it is possible to see that, in contrast to the previous test, the circuit now operates in Boost mode. Despite different average current and voltage values and different duty cycle, the waveforms have similar behavior when compared to

Figure 9.

Additionally, the proposed bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter was also simulated in different transient conditions. In this context, the first test was performed with the converter operating in the forward energy transfer mode, where several step changes in the duty cycle were considered, specifically from 0 to 0.4, 0.5, 0.6 and ending at 0.45. The resulting waveforms of this test can be seen in

Figure 11, confirming the changes in the output voltages in response to duty cycle variations (see

Figure 11a) and the input and output continuous currents (see

Figure 11b), which also change their values in response to the respective duty cycle variations, while always remaining without discontinuities. The bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter was also simulated in transient conditions in the reverse energy transfer mode. Again, similar step changes in the duty cycle were considered, ranging from 0 to 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, and ending at 0.45.

Figure 12 shows the obtained simulation waveforms in such conditions. When compared to the previous transient test, the input and output currents in this figure are inverted, confirming the reverse energy flow. These currents are continuous in all operating regions, as expected. Nevertheless, in this condition only the input voltage changes, as expected (see

Figure 12a).

A final transient test was conducted by applying sudden changes to the input

Vi voltage source during forward-mode operation and to the

Vo voltage source during reverse-mode operation.

Figure 13a presents the obtained results for the input and output voltages for the forward-mode operation test with a duty cycle of 0.4. This simulation test started with an input voltage (

Vi) of 24 V, which was subsequently stepped to 48 V, then to 72 V, and finally to 42 V. A resistor load was used at the output to verify that the voltage gain is maintained and to observe the transient behavior of the output voltage in such conditions. In fact, the output voltage stepped from 43 V to 85 V, then to 128 V, and finally to 74 V, confirming that the voltage gain ratio was maintained. There were also some oscillations immediately after the step change in the

Vi voltage source, as expected considering the two inductors and capacitors. The results obtained for the reverse-mode operation are presented in

Figure 13b. In this case, a duty cycle of 0.45 was used, and the output voltage source was sequentially stepped from 200 V to 160 V, then to 120 V, and finally to 170 V. Identical to the previous test, a resistor load was employed, but it was placed at the input of the converter to see the transient operation. Again, the voltage gain was maintained, as the input voltage stepped from 50 V to 40 V, then to 30 V, and finally to 43 V, following the sequence of the output variation. As verified in the previous case, there are also some oscillations immediately after the step change in the output

Vo voltage source.

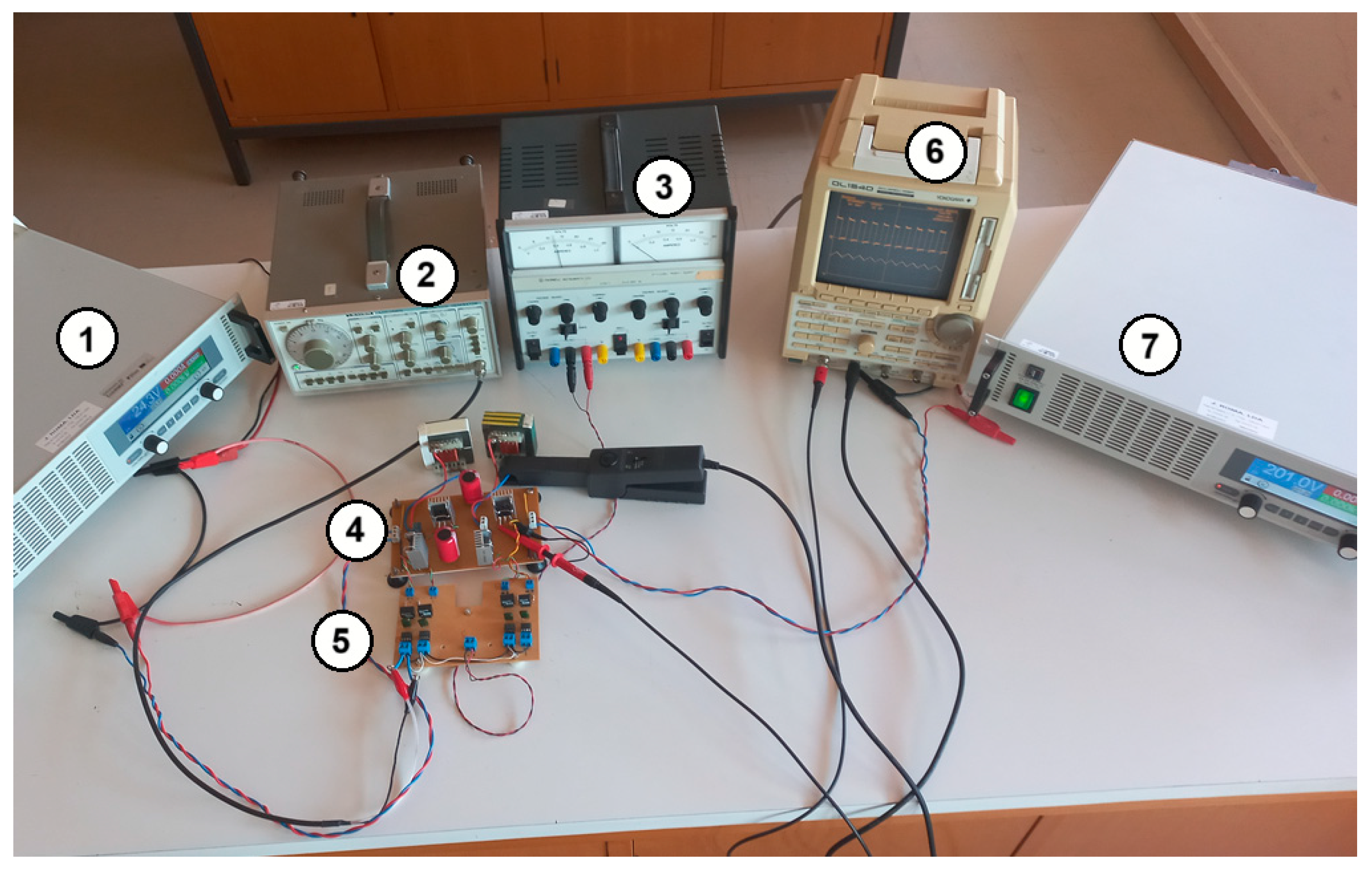

6. Experimental Tests

To experimentally verify the performance of the proposed bidirectional DC-DC converter, a laboratory prototype with 1 kW based on the topology presented in

Figure 1 was developed and tested. From the low voltage side, this

DC-DC converter was supplied with an initial voltage of 24 V

DC. From the high-voltage side, this

DC-DC converter was connected to DC Electronic Load with Inverter Function (EA-ELR 10200-25 2U 1500 W).

Figure 14 shows the experimental test bench with the proposed laboratory prototype, where the most relevant equipment is identified. In this figure, it is possible to see: 1—controlled voltage sources (EA PS8360-30 2U); 2—waveform generator for the proposed bidirectional DC-DC converter; 3—auxiliary power source for the gate drive circuits; 4—proposed DC-DC converter topology using SiC MOSFETs (UJ4SC075006K4S–Onsemi manufacturer); 5—gate drive circuits and protections based on UCC21520 circuit; 6—DL1540 Yokogawa oscilloscope; and 7—DC Electronic Load with Inverter Function (EA-ELR 10200-25 2U 1500 W).

Several experimental tests under operating conditions analogous to the simulated ones proposed in the previous section were also performed in a laboratory environment. A laboratory prototype of the proposed bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter was implemented and used for this purpose.

Table 3 shows the parameters and details of the converter components as well as the operation specifications.

The proposed bidirectional Buck-Boost DC-DC converter laboratory prototype was tested as close as possible to the simulation tests to validate the theoretical considerations. Thus, the first experimental test was also conducted in forward energy transfer mode. For this test, a duty cycle of 0.67 was used for transistors

T1 and

T2. The corresponding obtained oscilloscope waveforms can be seen in

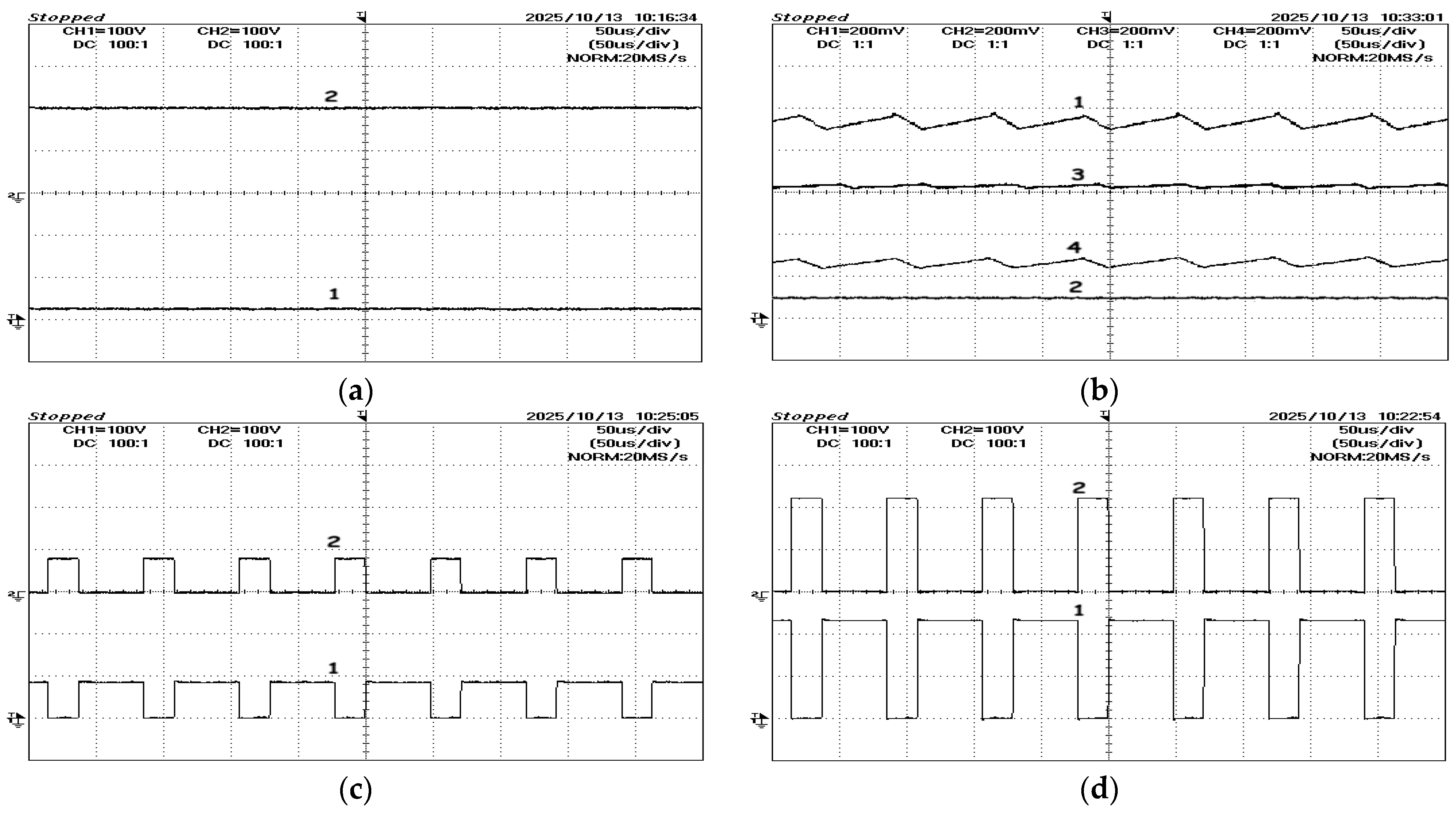

Figure 15. The voltage gains of each channel and time base are described in each figure caption.

Figure 15a illustrates the input (Ch1) and output voltages (Ch2) showing agreement with the converter parameters and duty cycle of the transistors

T1 and

T2, in accordance with the voltage gain ratio given by Equation (5). The input (Ch1) and output currents (Ch2) as well as the current in the inductors (IL1 in Ch3 and IL2 in Ch4) are represented in

Figure 15b illustrating continuous waveforms in all the currents. It is also possible to confirm that

T1 and

T2 operate synchronously, as the transistor voltage waveforms illustrate, namely VT1 in Ch2 of

Figure 15c and VT2 in Ch2 of

Figure 15d. The transistors

T1 and

T2 voltage waveforms also confirm that the transistor

T2 must withstand the maximum output voltage, while transistor

T1 must withstand a much lower voltage, as expected by the theoretical considerations and simulation results.

In DC-DC converters, attention should be addressed to the ripple in the inductors. Excessive ripple can affect the core losses in the inductors (high ripple current means the magnetic flux swings more widely each cycle, thus core losses (hysteresis + eddy currents) increase roughly with both frequency and ΔB (proportional to ΔIL) and conduction losses in capacitors (due to ESR) and power devices. The switching losses of power devices can also degrade the efficiency of the DC-DC power converter due to higher currents or voltages/overvoltages during the turn-on and turn-off process. On the other hand, to reduce the ripple, it is necessary to increase the switching frequency of the power devices, maintaining the same current average value. This will reduce the conduction losses of power devices but increase their switching losses inversely. The same goes for core losses. Reducing the higher current is important to reduce core losses but increasing the frequency creates an opposite effect. Since we cannot escape from power losses, the best we can do is to balance the parameters and operation of the converter to obtain acceptable efficiency and proper operation. In the design of the proposed converter, a ripple from 10 to 15% (which happens in the current of L2) was considered acceptable as it happens with most converters of this type.

Like the simulation results, several experiments tests with the proposed bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter prototype operating in forward energy transfer mode and Buck operation were also performed, using again the parameters listed in

Table 3.

Figure 16 shows the oscilloscope waveforms obtained in steady state and with a duty cycle of 0.2. Analyzing the converter from the input (

Vi) (see Ch2 in

Figure 16a) to the output (

Vo) (see Ch1 in

Figure 16a), a high-voltage gain reduction can be noticed in this condition, confirming the Buck operation in forward energy transfer mode. The current injected into the output voltage source (see Ch2 in

Figure 16b) provided by the input voltage source (Ch1 in

Figure 16b) and the currents in the inductors (IL1 as Ch3 in

Figure 16b and IL2 as Ch4 in

Figure 16b) are consistent with the simulation results and all of them remain continuous. In this condition, the transistors

T1 and

T2 are used to transfer energy and the blocking voltages in transistors

T1 and

T2 are presented in

Figure 16c-Ch2 and

Figure 16d-Ch2, respectively. Similarly, these figures show that transistor

T1 needs to withstand a lower voltage, while transistor

T2 needs to withstand a higher voltage, namely the capacitor

C1 voltage. Again, the voltage gains of each channel and time base are described in each figure caption.

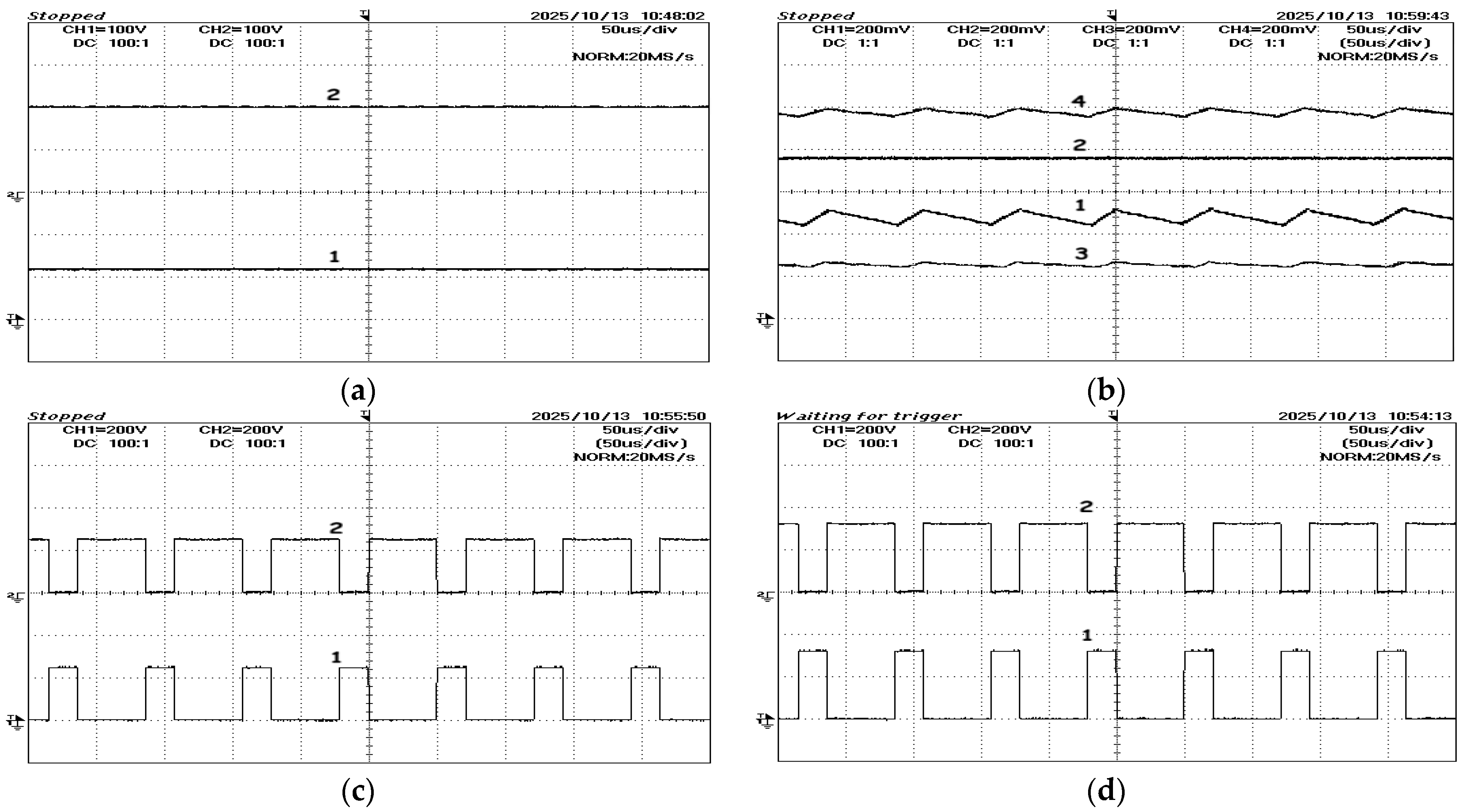

Experimental results with the proposed bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter operating in reverse energy transfer mode were also performed.

Figure 17 shows the waveforms obtained for these experimental tests in steady state and with a duty cycle of 0.33. When seen from the converter output (

Vo) side (see Ch2 in

Figure 17a) to the input (

Vi) side (see Ch1 in

Figure 17a), a high-voltage gain reduction is noticed. In this situation, the current injected into the input voltage source (see Ch1 in

Figure 17b) remains continuous, indicating that this converter is suitable for battery applications or other applications requiring continuous currents. The current at the output terminals (see Ch2 in

Figure 17b) is also continuous, as well as the currents in the inductors L1 (see Ch3 in

Figure 17b) and L2 (see Ch4 in

Figure 17b). The inversion of the currents presented in

Figure 17b checks the reverse energy transfer mode. The blocking voltages in transistors

T3 and

T4 are also visible, showing that transistor

T3 (see Ch1 in

Figure 17c) needs to withstand a lower voltage, while transistor

T4 (see Ch1 in

Figure 17d) needs to withstand a higher voltage, namely the capacitor

C1 voltage (see Ch2 in

Figure 17e). The voltage waveforms in all the transistors and capacitors are available from

Figure 17c–e.

Another experimental test to confirm the Boost operation of this converter in reverse energy transfer mode, was also performed.

Figure 18 shows the results in this situation in which the duty cycle is 0.67. From this figure, it is possible to see that, in contrast to the previous test, the circuit now operates in Boost mode since the input voltage (see Ch2 in

Figure 18a) is higher than the output voltage (see Ch1 in

Figure 18a). The remaining waveforms are like the previous experimental test, where the inversion of the currents with different average values can be seen again due to the Boost operation (

Figure 18b).

Figure 18c,d present the blocking voltages in all the transistors, showing that transistor

T3 (see Ch1 in

Figure 18c) needs to withstand a lower voltage, while transistor

T4 (see Ch1 in

Figure 18d) needs to withstand a higher voltage, namely the capacitor

C1 voltage (see Ch2 in

Figure 18e).

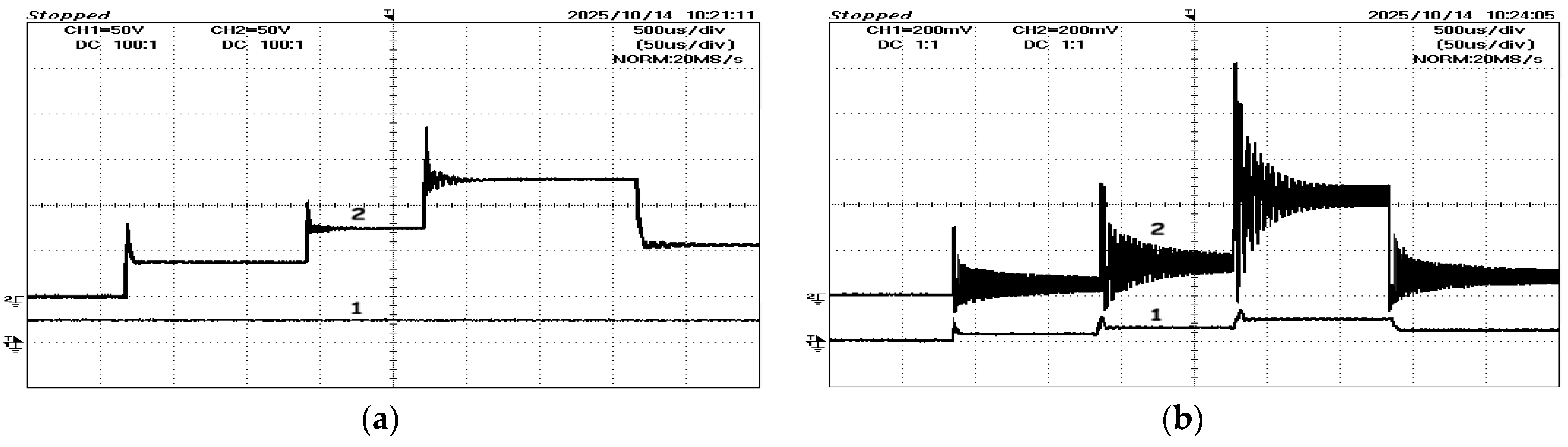

In addition, the proposed bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter was also experimentally tested in several transient conditions. Similarly to the simulation results, these experimental tests were performed with the converter operating in forward and reverse energy transfer mode, where step changes in the duty cycle were considered, specifically from 0 to 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, and ending at 0.45. The resulting waveforms of this test can be seen in the next figure, confirming the changes in the output voltages (see Ch2 in

Figure 19a), and the variation in both input (see Ch2 in

Figure 19b) and output (see Ch1 in

Figure 19b) currents because of these duty cycle variation steps. This figure also confirms the intended input and output continuous currents. They also change their value in response to step changes in the duty cycle while remaining without discontinuities. Similarly, the proposed bidirectional Buck-Boost

DC-DC converter prototype was also subjected to transient tests also in the reverse energy transfer mode. Again, step changes in the duty cycle were considered, ranging from 0 to 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, ending at 0.45.

Figure 20 shows the obtained experimental waveforms in such conditions. In this mode, only the input voltage changes in response to the duty cycle variation. When compared to the previous test, the input and output currents in this figure reverse their direction, confirming the reverse energy flow. These currents are continuous in all operating regions. Such voltage variations were made thanks to the analog remote control interface available in the power sources of the laboratory.

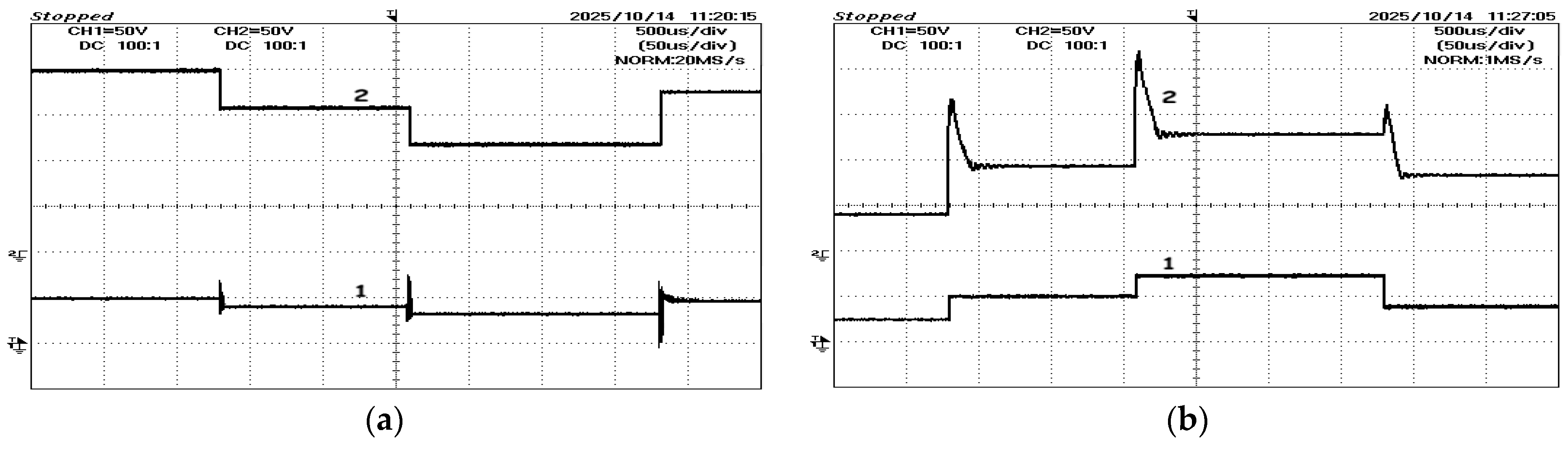

Finally, some experimental tests in transient mode were also conducted by applying step changes to the input voltage source (

Vi) during the forward-mode operation and step changes to the output voltage source (

Vo) during reverse-mode operation.

Figure 21a presents the obtained results for the input and output voltages for the forward-mode operation test with a duty cycle of 0.4, considering multiple step input voltage changes. Similarly,

Figure 21b presents the obtained results for the input and output voltages for the reverse-mode operation test with a duty cycle of 0.45, considering multiple step output voltage changes, which is the reverse condition. As verified in the previous case, there are also some transient oscillations immediately after the step changes in the input or output voltage source. These oscillations are the natural consequence of the parameters of the components adopted in these experimental tests. Despite not being performed in this prototype version, some optimizations can be performed if necessary to mitigate these oscillations and overvoltages.