1. Introduction

Lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries have become the cornerstone of energy storage for electric vehicles (EVs) and other high-performance applications due to their superior energy density, long cycle life, efficiency, reliability, and affordability [

1,

2,

3]. Ensuring safe and efficient operation of these batteries requires continuous monitoring by a battery management system (BMS) [

4,

5,

6], with accurate state-of-charge (SOC) estimation being especially critical because SOC errors can compound into reduced lifespan or safety risks [

7,

8]. Among the various SOC indicators, the open-circuit voltage (OCV) measured at (quasi-)equilibrium is widely used because OCV exhibits a near-monotonic relationship with SOC and the OCV–SOC map is relatively stable against ageing and temperature variations [

1,

9]. At the same time, TTE studies highlight chemistry- and condition-specific complications that can bias OCV-based estimation, including plateau regions and temperature-dependent deviations that introduce OCV–SOC curve errors (e.g., in LiFePO

4 cells) [

10], as well as ageing-induced shifts that must be anticipated over long service lifetimes, where physics-guided machine learning has shown promise in forecasting degradation trajectories and knee points [

11]. Consequently, establishing an accurate, temperature- and ageing-aware OCV–SOC characterization remains fundamental for both offline calibration and real-time SOC estimation in modern EV BMS.

Over the years, numerous approaches have been developed to model the nonlinear OCV-SOC relationship for use in BMS algorithms. Among these, the Galvanostatic Intermittent Titration Technique (GITT) and the low-rate cycling method are important ones [

12]. In the GITT approach, individual OCV-SOC points are measured intermittently and recorded in a way that the resulting OCV-SOC data spans the entire SOC range. Here, the SOC is changed by applying a constant current [

13]. Existing standards stipulate discharging the cell in 10% steps and applying a 10 s charge/discharge pulse at each step to estimate other battery parameters such as the resistance and RC components. The 1 h rest is standardized to allow the battery to achieve cell equilibrium potential. Just before the next discharge step, the OCV is measured. In the low-rate cycling approach (see [

14] for a review), a battery is discharged and then charged using the same low C-Rate while continuously collecting the voltage and current data. Owing to the low current rate, the low-rate cycling method is also called the Coulomb titration (CT) technique. The advantage of the low-rate OCV modeling approach over the GITT method is that the former enables high resolution OCV-SOC data in a relatively short time.

The focus of the present paper is on the low-rate OCV testing approach. It is shown in this paper that this conventional method suffers from notable shortcomings when applied at low temperatures. Increased internal resistance at subzero conditions causes the battery voltage to prematurely reach cutoff thresholds, leading to early termination of charging and discharging steps. Consequently, the measured voltage profiles are truncated, resulting in underestimated usable capacity and a compressed SOC window. This ultimately distorts the OCV-SOC curve, which can bias SOC estimation and degrade BMS performance. While several studies have proposed strategies such as redefining SOC limits or adjusting for capacity loss [

9], the specific issue of voltage truncation caused by polarization effects remains inadequately addressed. In practice, truly capturing the entire OCV-SOC curve at sub-freezing conditions would require either extremely long relaxation periods at many intermediate SOC points (as part of the GITT procedure) or accepting a truncated curve and then applying elaborate post hoc corrections. A clear gap remains for a simple yet effective procedure to retain the complete OCV-SOC profile under cold-temperature testing without resorting to impractical protocols.

In this paper, we introduce a novel offsetting-based correction method to address the low-temperature OCV truncation problem. The key idea is to extrapolate the OCV curve beyond the points where the standard test had to stop by applying an appropriate voltage offset to the end-of-charge and end-of-discharge portions of the measured curve. In essence, the method projects what the terminal voltage would have been at 100% SOC (above the upper cutoff) and at 0% SOC (below the lower cutoff) if the cell were not limited by polarization. This can be implemented in a straightforward manner: for example, by linearly extrapolating the tail end of the discharge voltage vs. time curve to estimate the missing segment beyond the lower cutoff. While overcharging or overdischarging the battery is not feasible in live systems due to risks like thermal runaway [

15,

16], degradation [

17], and uncertain safe margins, such extrapolation can be performed safely in an offline modeling context. Our method accounts for the voltage drop induced by internal resistance and effectively restores the full OCV range (e.g., 3.0 V to 4.2 V) without modifying the standard testing procedure.

The proposed offsetting approach utilizes simple models—such as estimating the IR drop based on internal resistance—to reconstruct portions of the OCV curve that are truncated at low temperatures. Since the correction is applied entirely in post-processing (i.e., without physically overcharging or undercharging the battery), linear or model-based voltage offsets can be safely introduced at the SOC boundaries. This enables recovery of the true OCV limits— at 0% SOC and at 100% SOC—which effectively compensates for the voltage range lost due to low-temperature polarization. The effectiveness of this method is validated using experimental data from Samsung EB575152 lithium-ion cells tested across a wide temperature range from −25 °C to 50 °C.

The corrected curves show that the intended voltage span is restored at all temperatures. To quantify the improvements, we introduce three performance metrics: (i) the voltage offset at SOC boundaries, which directly measures the recovered voltage gap at low/high SOC; (ii) the cell-to-cell (C2C) variation in OCV, indicating whether the correction increases measurement consistency across different cells; and (iii) the temperature-induced OCV variation, evaluating how much the OCV curve shifts with temperature before and after applying the offset. These metrics provide a rigorous basis to assess the accuracy and robustness of the corrected OCV profiles. The results show that the offsetting approach significantly reduces the apparent capacity loss at low temperatures and narrows the disparity between OCV curves at different temperatures, thereby enhancing the fidelity of OCV-SOC modeling for BMS applications.

The primary contributions of this paper are as follows:

For the first time, this paper reports that traditional low-rate OCV testing introduces a subtle but systematic bias in the OCV–SOC curve due to internal resistance, particularly at the SOC boundaries. This bias, although often overlooked, can significantly impact state-of-charge estimation in low-temperature environments.

The paper proposes a novel offsetting-based correction method that compensates for polarization-induced truncation in low-temperature OCV testing. The method employs simple linear extrapolation and is implemented entirely in post-processing, requiring no changes to standard test protocols.

The effectiveness of the proposed method is experimentally validated using Samsung EB575152 Li-ion cells tested across a wide temperature range (−25 °C to 50 °C), demonstrating recovery of the full intended OCV range (3.0–4.2 V) otherwise lost at extreme temperatures.

The paper introduces three performance metrics—boundary voltage offset, cell-to-cell variation, and temperature-induced variation—to quantify improvements in OCV–SOC curve consistency.

The analysis shows that compared to traditional low-rate testing, the proposed method significantly improves voltage span recovery and modeling fidelity, particularly in the mid-to-high SOC region.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the OCV measurement procedure and analyzes the effect of temperature on low-rate OCV testing, highlighting the problem of truncated curves at cold temperatures.

Section 3 details the proposed offsetting methodology, including the extrapolation technique and implementation considerations.

Section 4 presents a theoretical analysis and justification of the proposed method.

Section 5 presents and discusses the experimental results and

Section 6 concludes the paper with a summary of contributions and suggestions for future work.

2. Problem Description

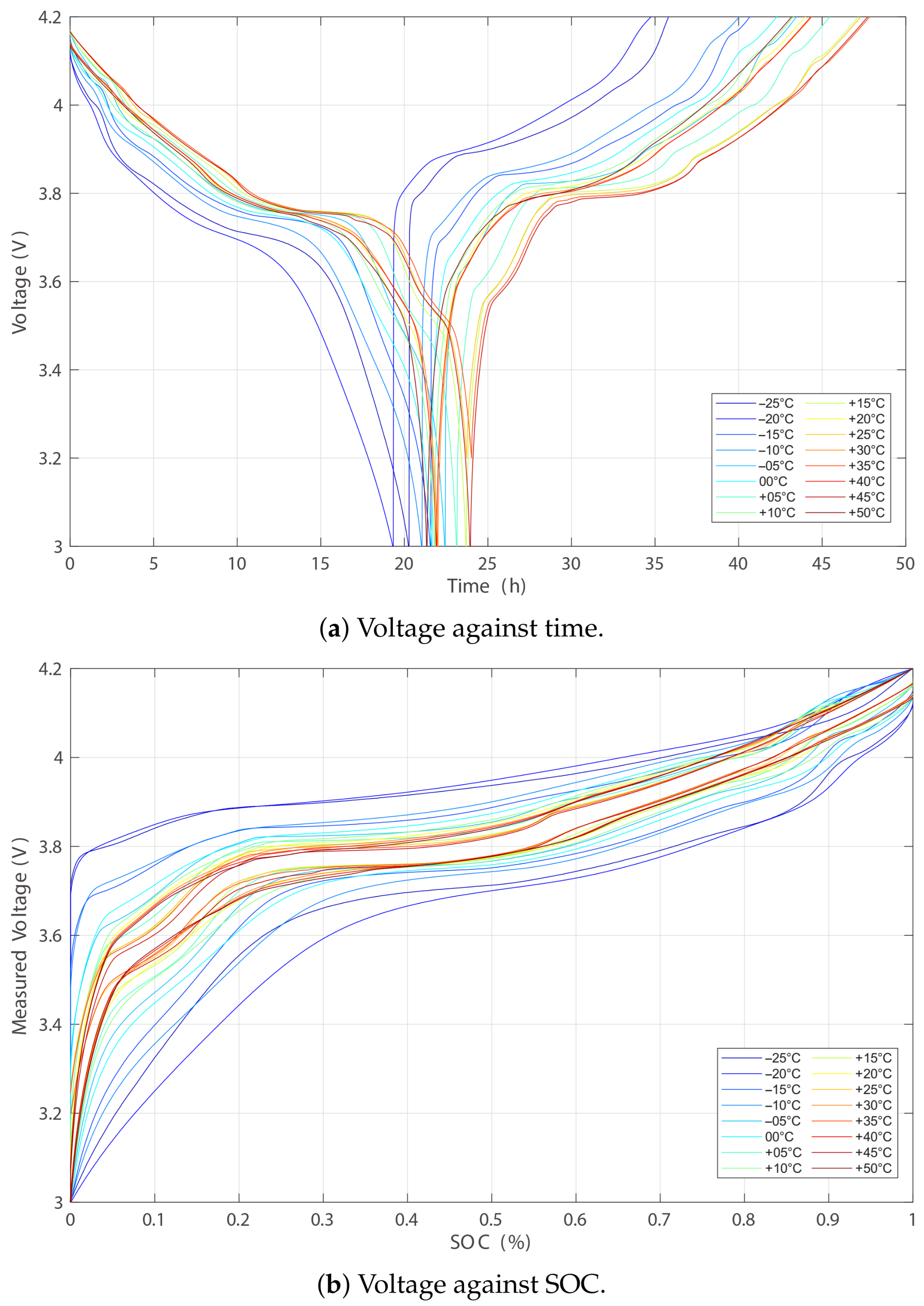

Figure 1a shows the voltage of the battery during the low-rate OCV test, C/30 discharge followed by C/30 charge, at different temperatures. In low-rate OCV modeling, the battery is considered full

when the voltage is at

and it is considered empty

when the voltage is at

Using this fact, the SOC is scaled between 0 and 1 separately during discharging and charging.

Figure 1b shows the measured voltage of the battery against the SOC for sixteen different temperatures.

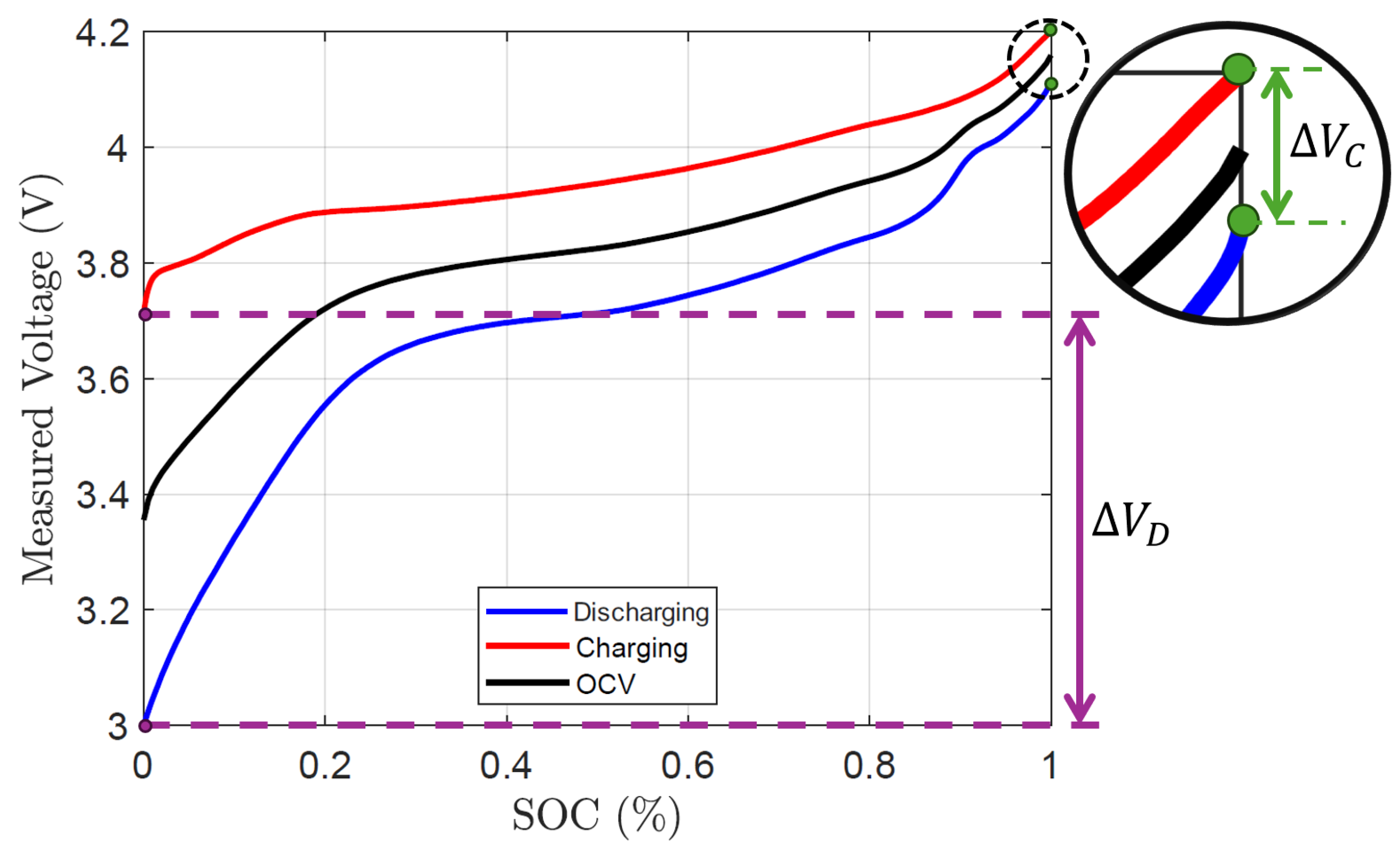

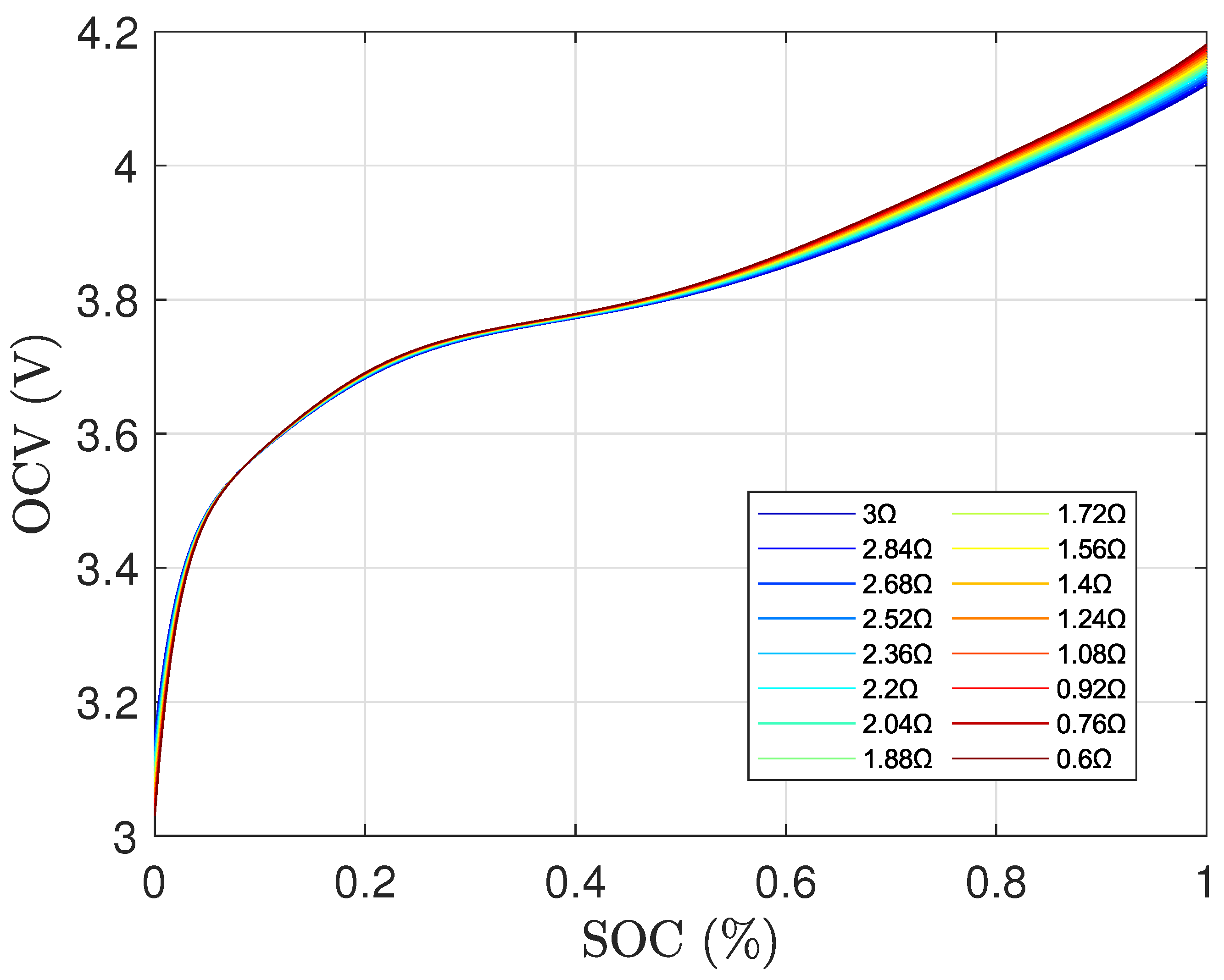

The OCV-SOC curves obtained through the low-rate OCV modeling approach summarized in

Section 1 is shown in

Figure 2.

Here, a significant variance in the OCV values can be noticed. Before investigating the effect of temperature on the OCV-SOC curve, the focus will be placed on removing errors due to the low-rate OCV modeling approach.

Figure 3a shows the total resistance

of the battery. It can be seen that the resistance significantly increases at cold temperatures. Due to the increase in resistance, the charging/discharging activity is prematurely terminated; this can be clearly seen in

Figure 1. Due to premature termination of charging/discharging, the battery capacity is underestimated; this in turn affects the computed SOC that was always scaled between 0 and 1 in the low-rate OCV modeling approach [

14]. It is possible that the computed OCV-SOC curve is affected as a result.

Section 3 details an approach to ease the effect of the resistance in the computed OCV-SOC curve of the battery.

Remark 1. The fluctuations or “zig-zag” pattern observed between the even- and odd-numbered temperature tests can be attributed to battery aging effects. Initially, experiments at the odd-numbered temperatures were performed using new battery cells. By the time the even-numbered temperature tests were conducted, the same cells had undergone some degree of aging. This explains the observed variation, as aged cells typically exhibit reduced capacity and increased internal resistance compared to new ones. Nonetheless, the proposed method was applied successfully to both aged and new cells, demonstrating its robustness across different cell conditions.

3. Proposed Offsetting Approach

Figure 1b shows the measured terminal voltage at each temperature during both discharging and charging with respect to the SOC.

Figure 4 is another representation of

Figure 1b, where the terminal voltages at various temperatures are categorized into charging (indicated in red) and discharging (indicated in blue). Here, represented by the green circles, all test were stopped at 4.2 V when charging and 3 V when discharging. Also, it is observed that for all the temperatures tested, the terminal voltage is lower than the OCV when discharging and higher when charging. Thus, the two terminal voltages for each respective temperature are averaged and is considered as the OCV for each SOC point. This is shown in

Figure 2. From the resulting OCV-SOC curves, none of the temperatures tested ever reached the desired minimum OCV (

= 3 V) when the battery was considered empty (s = 0) and maximum OCV (

= 4.2 V) when the battery is considered full (s = 1). This is a direct consequence of the collected data stopping every test when the terminal voltages reach

= 3 V or

= 4.2 V when discharging and charging, respectively.

Figure 5 shows the most extreme case of this problem where the test temperature was −25 °C. At s = 0, the discharge and charge terminal voltages were 3 V and 3.71 V, respectively. Thus, the OCV value will be 3.3515 V when they are averaged. Similarly, at s = 1, the resulting OCV value through averaging will be 4.1595 V. This process is performed on the entire domain of the SOC,

, and the resulting OCV-SOC curve is represented by the black line. It is clearly seen that the resulting curve does not have the desired

and

when averaged. It is also observed that when we inspect

Figure 2 again, as the temperature decreases, the OCV value when s = 0 and s = 1 is seen to be deviating further away from our desired

and

, respectively. This results in the OCV range becoming more skewed as the temperature decreases. In the remainder of this section, an approach is presented to fix this problem by extending the charge and discharge curve for each temperature by their respective voltage drop. With this approach, all of the OCV-SOC curves will span the same intended OCV range.

From

Figure 5, the distance between the charge and discharge curve is calculated as

where

is the charge terminal voltage,

is the discharge terminal voltage,

is the voltage difference when the battery is empty, and

is the voltage difference when the battery is full.

These distances,

and

, are now used to extend the raw discharge and charge curves to offset the voltage differences. In

Figure 6, it is seen that the discharge curve is extended further down by

, represented by the magenta line, and the charge curve is extended further up by

, represented by the green line. When

,

will remain the same and the new

will be the end value of the extended magenta line. Similarly, when

,

will remain the same and the new

will be the end value of the extended green line.

Figure 7 shows how this approach achieves the desired

and

by extending the curves and accounting for the voltage drop. When the battery is empty, the charge and new discharge terminal voltage were 3.71 V and 2.31 V, respectively. Thus, the OCV value computed by averaging will be 3 V. Similarly, when the battery is full, the resulting OCV value will be 4.2 V when averaged.

For extending the charge and discharge curve, a linear extrapolation is used to find the extended data for this approach. In

Figure 6, the final five data points (time and their corresponding terminal voltages) at the end of the raw discharge curve and the first five data points of the beginning of the raw charge curve are taken. Separately, the points from the discharge curve and the charge curve are then each linearly fitted using the least squares method to find the lines that best fit those selected points. The two slopes are then averaged together and the resulting slope, represented by the magenta line, is used to extend the data by the offset voltage difference,

. It is important to note that since the slope of the charge curve will be positive, the negative value will be taken to correctly average the two. Now, 650 data points are taken from the end of the charge curve and the slope, represented by the green line, is found through the least squares method. With this, the slope is extended upward by

. With these offsets, the curves are extrapolated until they reach the point where the voltage will offset the voltage differences.

Figure 7 shows the corrected offset of the charge and discharge curve where now the OCV curve has the desired voltage range.

This offsetting approach is repeated on the remaining temperatures and the OCV-SOC curves for all of them are shown in

Figure 8. In

Figure 2, the

and

are all different for each temperature as a result of the varying voltage drop. This problem was fixed in the OCV-SOC curve obtained from the proposed offsetting approach.

A preliminary version of the offsetting methodology, the Offsetting Approach I (OA-I), was presented in a prior conference publication [

18]. The present work builds upon that foundation by proposing and developing Offsetting Approach II (OA-II). The distinction between OA-I and OA-II is illustrated in

Figure 9, with OA-II serving as the primary method advanced in this study.

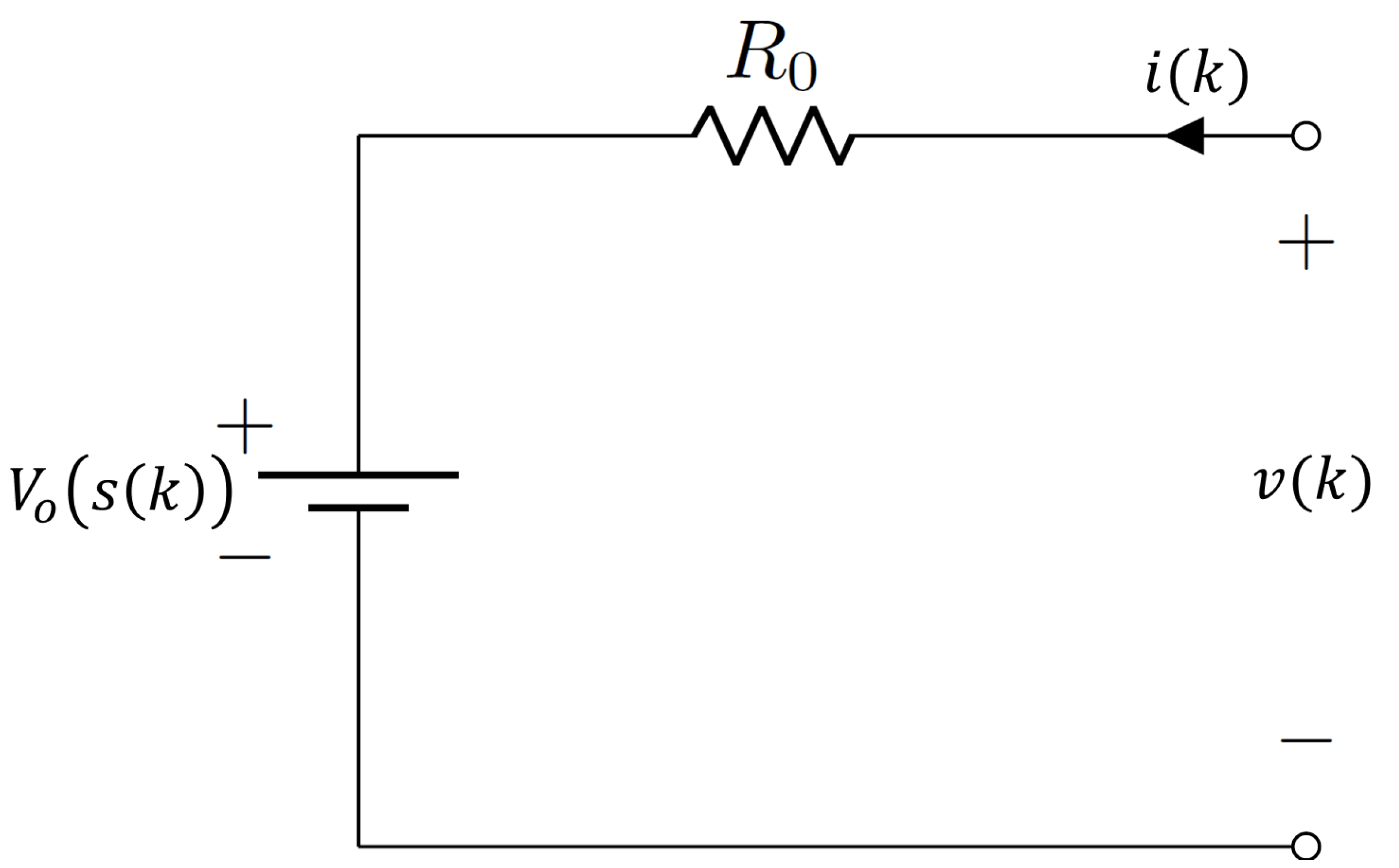

4. Theoretical Simulation Analysis

To further show the effect of the proposed Offsetting Approach on the OCV-SOC curve, a theoretical simulation is conducted using a battery simulator to simulate the low-rate OCV test. The voltage and current measurements are generated using the R-int electrical equivalent circuit model (EECM). The R-int EECM is shown in

Figure 10, where the terminal voltage can be written as

where

is the current measurement through the battery,

is the OCV effect, and

is the resistance.

When considering measurement noise, the measured voltage

and current

are written as

where the voltage and current measurement errors

and

are assumed to be zero-mean with standard deviations

and

, respectively.

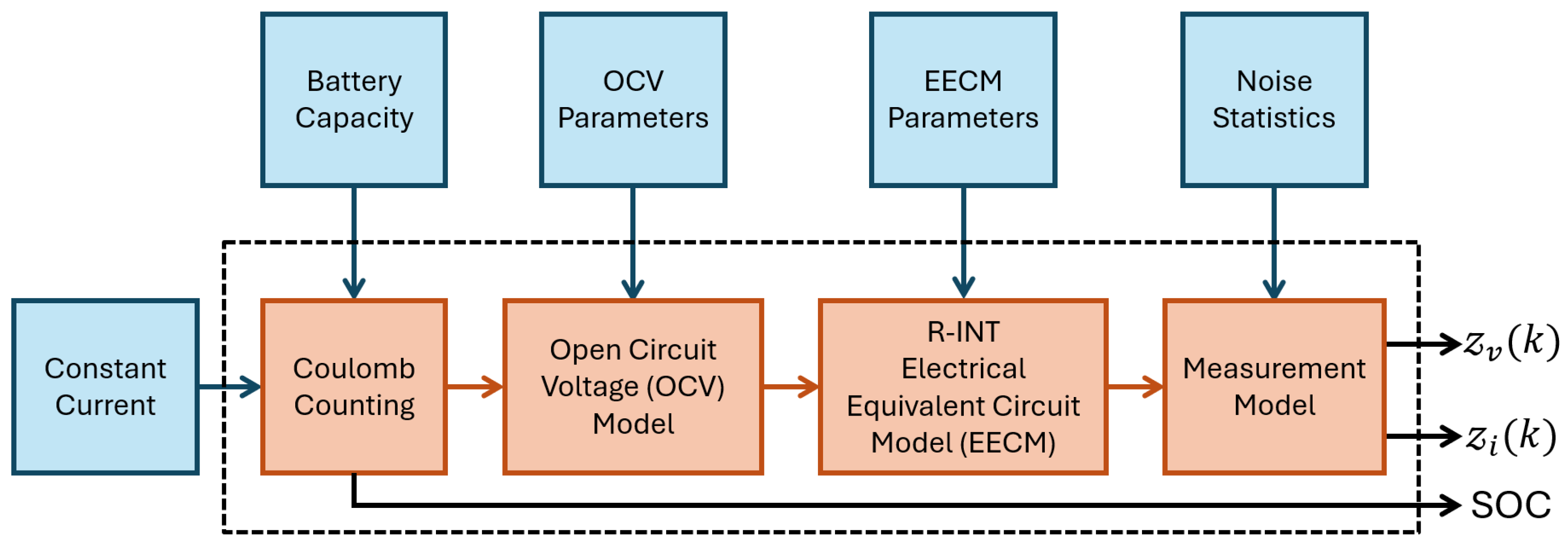

Figure 11 shows the battery simulator representation showing how

,

, and the SOC are generated as explained in the following:

Now, given , when the battery is simulated where it is assumed full at the start, . The battery is then discharged using a constant current of A until it reaches V. Next, the battery is charged using a constant current of until it reaches V.

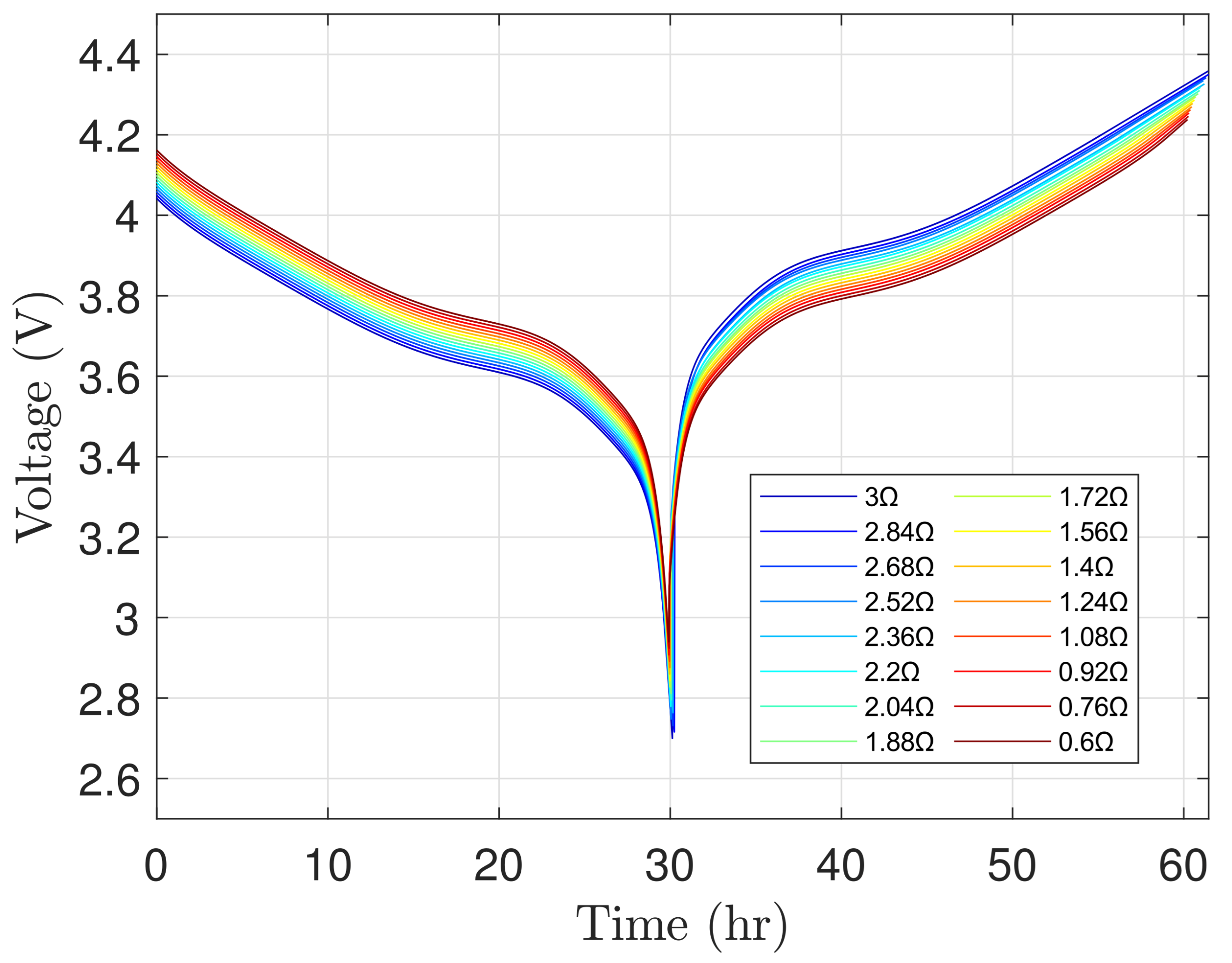

Figure 12 shows the terminal voltage for the varying internal resistances. Similar to the experimental data shown in

Figure 1a, the simulation tests in

Figure 12 are all stopped at

when discharging and

when charging, which underestimates the battery capacity, and consequently, affects the OCV-SOC curve.

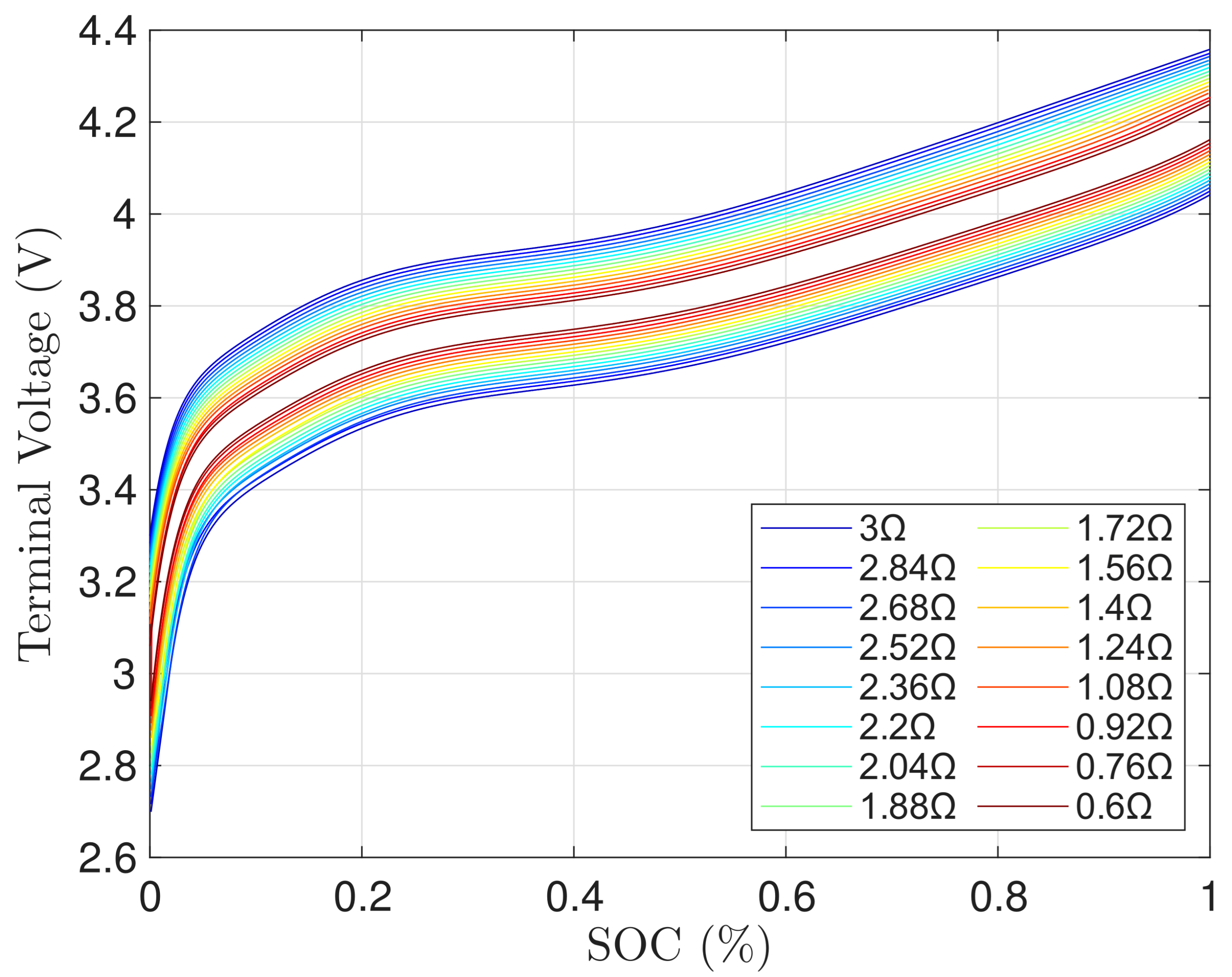

Figure 13 shows the measured voltage of battery against the SOC when assuming the same capacity for every temperature test. It is observed that as a result of the low-rate OCV test procedure, the test is stopped prematurely as the resistance increases. For example, in the figure, when the resistance is set to 3

, which represents a very low temperature, the terminal voltage when charging is seen to only reach about an SOC value of 0.85 since the test needs to be stopped when

is reached. Now, since this traditional approach always scales each curve from 0 to 1 [

14], this results in the charging and discharging curves becoming truncated. This is seen in

Figure 14 where the skewing due to the test procedure becomes evident.

Figure 15 shows the resulting OCV-SOC curves at all resistances or the equivalent temperatures in

Table 1. From this, it is seen that the OCV-SOC curve is affected by the unaccounted for voltage drops, resulting in variation at the high and low end of the SOC.

Figure 16a,b show an enlarged image of the low- and high-end SOC, respectively.

Figure 17 shows the proposed Offsetting Approach presented in

Section 3 where instead of limiting all tests to the same

and

, each test is offset by its respective voltage drop.

Figure 18 shows the terminal voltage of the battery when charging and discharging where it is observed how now, instead of all the temperatures being truncated, the voltages curves for each resistance will now correctly span the whole SOC range due to the proposed Offsetting Approach extrapolating past the voltage cutoffs and accounting for the voltage drop. Now, the OCV-SOC curve is shown in

Figure 19 where all the curves are found to be nearly identical with very little variance. This demonstrates that in theory, using the proposed Offsetting Approach should correctly fix the voltage drop issue allowing for similar OCV-SOC curves regardless of the internal resistance or temperature variations. However, this is clearly not what is happening when the approaches are applied to the real test data especially at lower SOC and very low temperatures. Thus, it is evident that simply representing the temperature by only changing the internal resistance is not entirely accurate.

Remark 2. The minimal variation in the OCV-SOC curves across all temperatures in Figure 19 highlights the robustness of the linear extrapolation approach under simulated conditions. This strong agreement confirms that the proposed method performs effectively even in realistic battery scenarios, given that the simulation parameters were directly extracted from experimental data on actual lithium-ion cells. Therefore, any discrepancies observed in practical applications (as discussed in the next section) are more likely attributable to temperature-dependent electrochemical phenomena, rather than limitations of the extrapolation technique itself. 5. Experimental Results

The battery used for experimental validation is the Samsung EB575152 Li-ion cell (Samsung SDI Co., Ltd., Yongin, Republic of Korea), which has a rated capacity of 1.5 Ah and employs nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) chemistry. Additional details on this battery and the data are provided in the associated Data in Brief (DIB) article [

19]. As noted, both the theoretical simulations and the forthcoming experimental results in this paper are based on the NMC chemistry. While the proposed offsetting approach is expected to be applicable to other chemistries such as lithium iron phosphate (LFP), this study focuses exclusively on NMC cells. Therefore, validation is recommended before applying the method to other battery chemistries.

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed Offsetting Approach mentioned in

Section 3 against the traditional low-rate OCV approach, three metrics are introduced and explained in the remainder of this section.

The OCV curves of all tested temperatures and batteries are summarized by

Table 2. Thus, the OCV curve can be represented by

where

q is a particular battery,

r is a particular test temperature, and

is the number of SOC points. For this paper, the total number of temperatures tested are

, the total number of cells are

, and the number of SOC points

were selected.

5.1. Performance Evaluation Metrics

5.1.1. Low-End and High-End Offset

For the low-end,

, the

for all temperatures is expected to be 3 V. Thus, for a particular temperature,

r, the mean low-end offset

is calculated as

where

j in this case will be

representing SOC = 0 and

is the number of batteries tested.

Similarly, for the high-end

, the

for all temperatures is expected to be

. Thus, for a particular temperature

r, the mean high-end offset

is calculated as

where

j in this case will be

representing SOC = 1 and

is the number of batteries tested.

Thus, the computed

and

for each temperature is represented by

Table 3.

5.1.2. Cell-to-Cell Variation

For a particular temperature

r, the OCV data is chosen from

Table 2 for the number of battery cells,

. For this, two cell-to-cell variation metrics are computed. These are the mean,

, and standard deviation,

, which are computed as

where

denotes the binomial coefficient of all possible number of combinations of pairs for

cells (see Remark 3). So, the OCV data difference between every possible combination of cells is taken and then averaged. It is important to note that the calculated mean in (

9) and standard deviation in (

10) are vectors of length

j which spans the SOC range.

Remark 3. Let us consider the case where four battery cells ( = 4) are tested to evaluate cell-to-cell (C2C) variation. In this case, the total number of combinations of cells is six possible pairings ( = 6) that are unique. We can have cells (1,2), (1,3), (1,4), (2,3), (2,4), and (3,4). Thus, in Equations (9) and (10), the C2C variations are computed by evaluating the difference in OCV values at each SOC point between every possible pair. This ensures that the variation is not biased toward any single cell and will reflect the overall spread in behavior across every tested battery instead. Thus, any cell can be chosen as a reference, as all variations in each cell is taken into account. Thus, the computed

and

for each temperature is be represented in

Table 4.

5.1.3. Temperature Variation

Again, the OCV data is chosen from

Table 2. For a particular temperature,

r, and all battery cells,

, the two temperature error metrics, mean

and standard deviation

, are computed as

where the test number

is chosen to be the reference OCV which the other OCV curves are to be compared against. It is important to note that the calculated mean in (

11) and standard deviation in (

12) are vectors of length

j which spans the SOC-Grid.

Thus, the computed

and

for each temperature is be represented in

Table 5.

5.2. Evaluation Results

In this section, the computation of three metrics, low-end and high-end offset, cell-to-cell variation, and temperature variation, are as explained in

Section 5.1.

5.2.1. Low-End and High-End Offset

For the traditional approach, the mean low-end offset,

, is calculated using Equation (

7). The offsets are tabulated and shown in

Table 6. It is observed how the

of each temperature is affected due to these offsets especially at very low temperatures such as −25 °C where the offset is 0.34758 V off the expected

of

.

The mean high-end offset,

, is calculated using Equation (

8). The offsets are tabulated and shown in

Table 7. Unlike for the low-end offset, all temperatures offset are not too far off of the expected

of

. The highest offset is around

for the lowest temperature, −25 °C.

It is important to note that for the proposed Offsetting Approach, the low-end and high-end offset will be zero for all temperatures since the whole goal of the Offsetting Approach is to remove the effects of low- and high-end offset.

5.2.2. Cell-to-Cell Variation

From computing the mean

in (

9) and standard deviation

in (

10), the cell-to-cell (C2C) variations at every temperature are found for all three approaches and compared. The C2C variation will span the entire SOC range between SOC = 0 and SOC = 1.

Figure 20a,b show the C2C variation at every temperature for the traditional approach and the proposed Offsetting Approach, respectively. The filled-in region for each temperature represents the window of uncertainty where the OCV value can fluctuate around and is between

. Thus, the uncertainty width of a given

j SOC point is

. With this definition, the max value of

for all temperatures spanning the whole SOC is around

. Upon inspection, the uncertainty widths did show some observable patterns for the differences between temperatures. For both approaches, the C2C variations tend to increase at the lower SOC region with the largest being around an uncertainty width of around

at SOC = 0.1. Another observation is that both approaches have peak C2C uncertainty width at the same SOC at the highest temperature range (40–50 °C).

5.2.3. Temperature Variation

For the reference temperature,

, the room temperature 25 °C was chosen as the standard OCV-SOC curve. For the three approaches, the uncertainties in OCV values are calculated for all 16 temperatures for the entire span of the SOC range between SOC = 0 and SOC = 1.

Figure 21a–c show the temperature variations of all three approaches for −25 °C, 10 °C, and 50 °C, respectively. The defined window of uncertainty in which the OCV value can fluctuate around is between

.

While comparing approaches at a very low temperature of −25 °C, it can be observed how large of an uncertainty the traditional approach yields at with an uncertainty width, with of around . For the proposed Offsetting Approach, the uncertainty at will be almost zero as all OCV-SOC curves are made to have the same . However, it can seen that an increase in uncertainty between the low SOC range of 0.05 and 0.3 happened as a result with peak of around . At higher SOC, the offsetting approach shows much lower uncertainty as compared to the traditional approach. Most notably, it is observed how even at the lowest temperature, the uncertainty window decreases compared to the traditional approach.

For 10 °C, it can be seen that there is not much uncertainty with all approaches with the peak uncertainty width, , being around for all approaches at an . This suggests that as the temperature increases to around the room temperature of 25 °C, the OCV-SOC curves become much more similar. It is also observed that even for higher temperatures, the proposed Offsetting Approach still results in lower uncertainty at higher SOC compared to the traditional approach.

Finally, for the highest temperature of 50 °C, the peak value of is larger than 10 °C, with the traditional having and proposed Offsetting Approach having .

Figure 22a,b show the uncertainties of the traditional approach and proposed Offsetting Approach for all temperatures using the computed mean and standard deviation in (

11) and (

12), respectively. Here, we can now see the variations at all temperatures when compared to 25 °C. Comparing these two approaches, the offsetting approach shows a very large

at lower SOC for low temperatures. This is in exchange for the large uncertainty window when SOC = 0 for the traditional approach. It is also observed how at the high SOC region, the uncertainty window for the proposed Offsetting Approach noticeably decreases when compared to the traditional approach.

6. Conclusions

This study identified a critical limitation in the standard low-rate OCV testing method for lithium-ion batteries—its tendency to truncate voltage curves at low temperatures due to elevated polarization. This premature cutoff results in underestimated capacities and skewed OCV–SOC profiles, narrowing the effective SOC window and reducing the accuracy of BMS algorithms.

To mitigate this, we introduced a straightforward offsetting-based correction method. By extrapolating the voltage curves beyond their cutoff limits—based on the observed voltage gap at SOC boundaries—we recovered the full voltage span that would otherwise be lost to temperature-induced polarization. This approach avoids the safety and degradation risks of actual overcharging or overdischarging and is applicable during offline characterization.

Experimental validation was conducted using a Samsung EB575152 cell across a wide temperature range (−25 °C to 50 °C), supported by theoretical simulations using an internal resistance (R-int) model. Results showed that the proposed correction improves the voltage range consistency in the mid-to-high SOC region (SOC ≥ 0.4) and partially recovers lost capacity, particularly in cold-temperature tests. However, the lower SOC region (SOC < 0.4) still exhibits significant variability, suggesting that polarization and capacity loss at low temperatures are not solely governed by internal resistance.

Furthermore, we evaluated both the traditional and proposed methods using three performance metrics: low/high-end offset, C2C variation, and temperature variation. These metrics confirmed that while the offsetting method effectively recovers OCV range and improves consistency in the upper SOC region, it introduces uncertainty in the lower SOC region, especially at low temperatures. The comparative analysis also revealed that cell-to-cell variation remains largely unaffected by the correction, indicating that inherent cell differences are not significantly altered.

In summary, the proposed correction method is a practical and low-risk enhancement to standard OCV testing. It restores lost capacity due to temperature effects, preserves the full usable OCV range, and improves SOC estimation accuracy without requiring additional tests or protocol changes. However, residual errors at low SOC and low temperature suggest that further modeling of non-ohmic behavior is needed for more accurate temperature-aware BMS design. Future work may also explore more advanced extrapolation techniques—such as higher-order polynomial fitting, spline interpolation, or physics-informed regression models—to improve the accuracy of curve reconstruction near the SOC boundaries.