SpectralNet-Enabled Root Cause Analysis of Frequency Anomalies in Solar Grids Using μPMU

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research Gap

2.2. Contribution

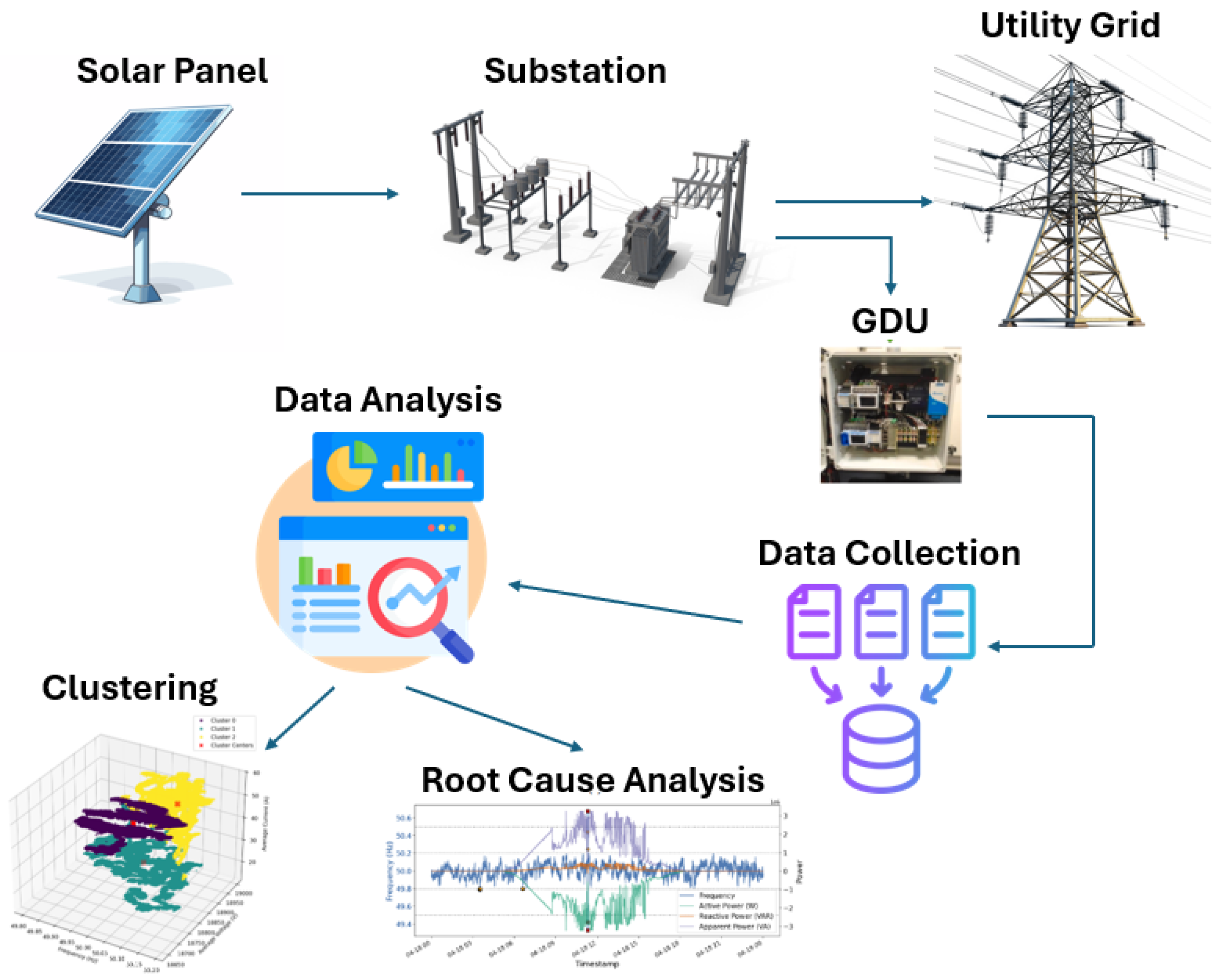

3. Methodology

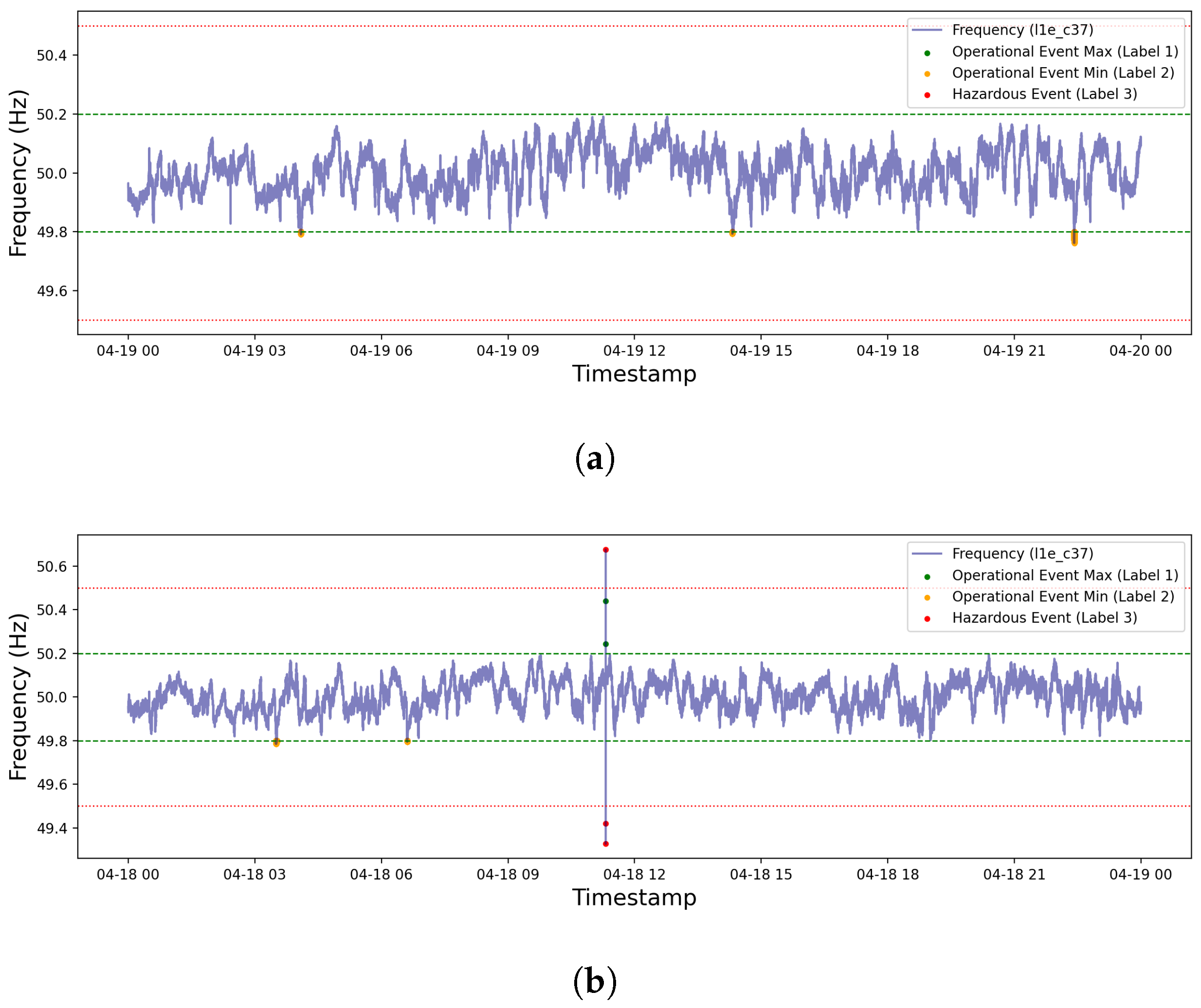

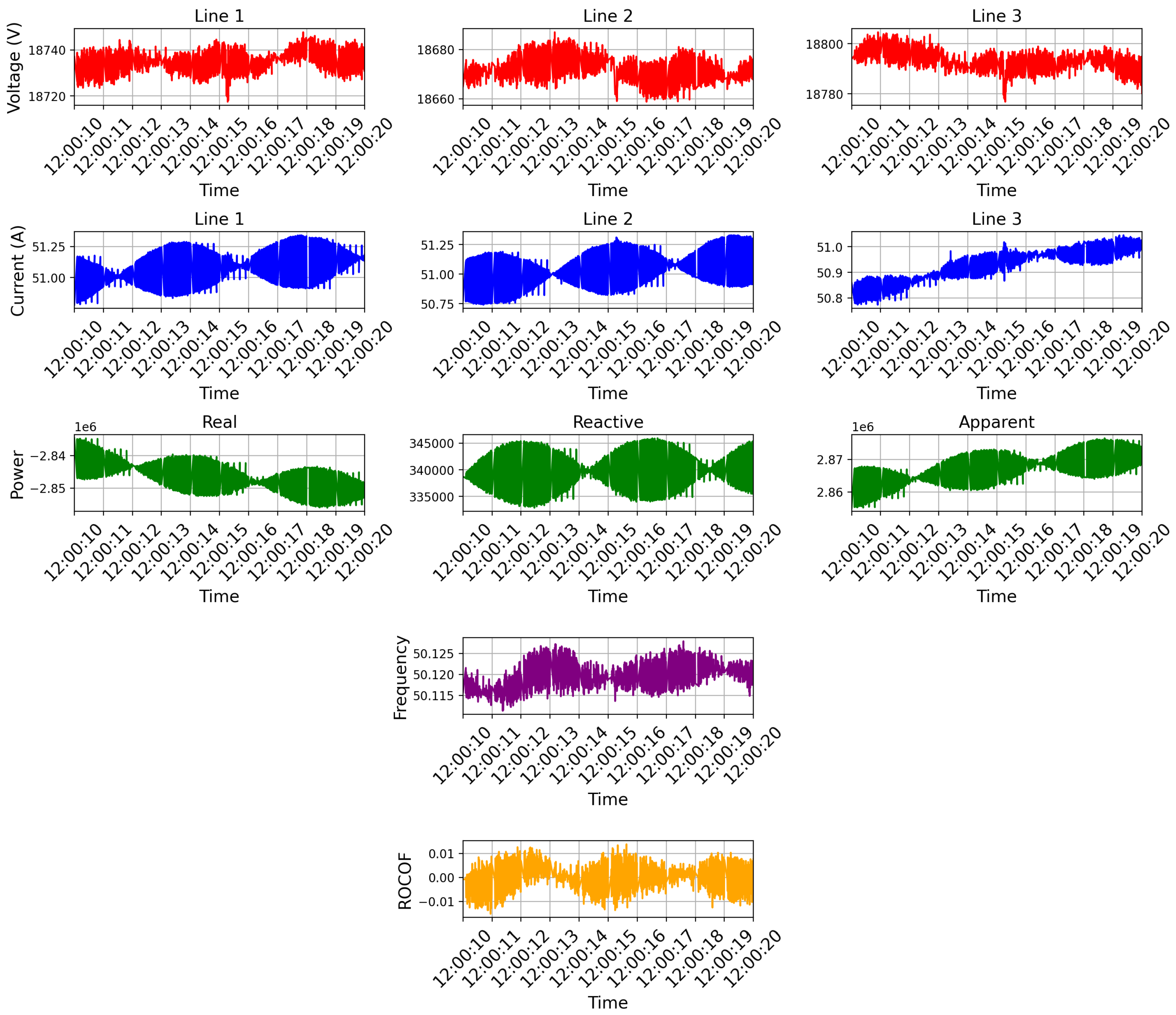

3.1. Data Pre-Processing and Feature Construction

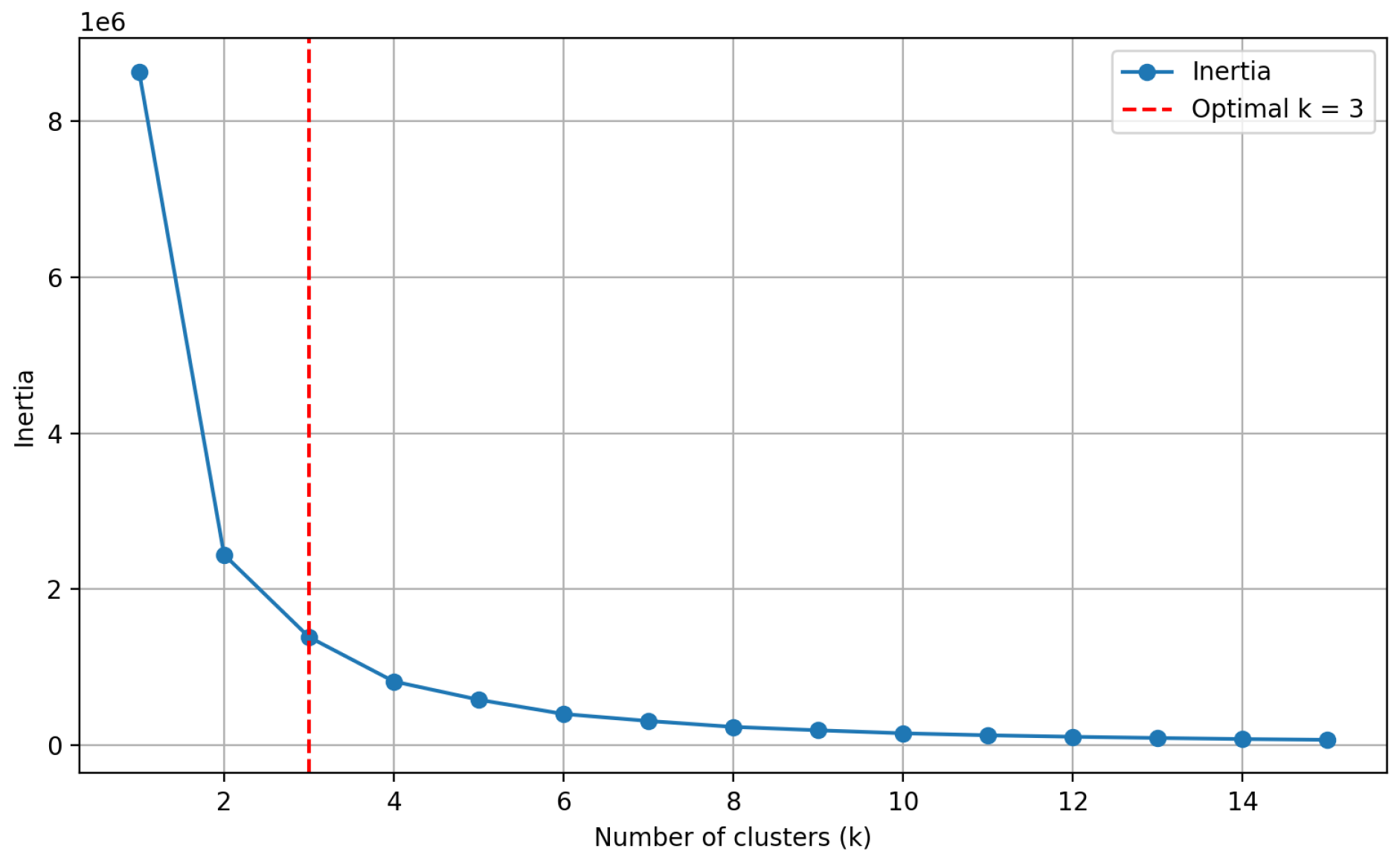

3.2. Clustering-Based Anomaly Detection

3.3. Experimental Design and Setup

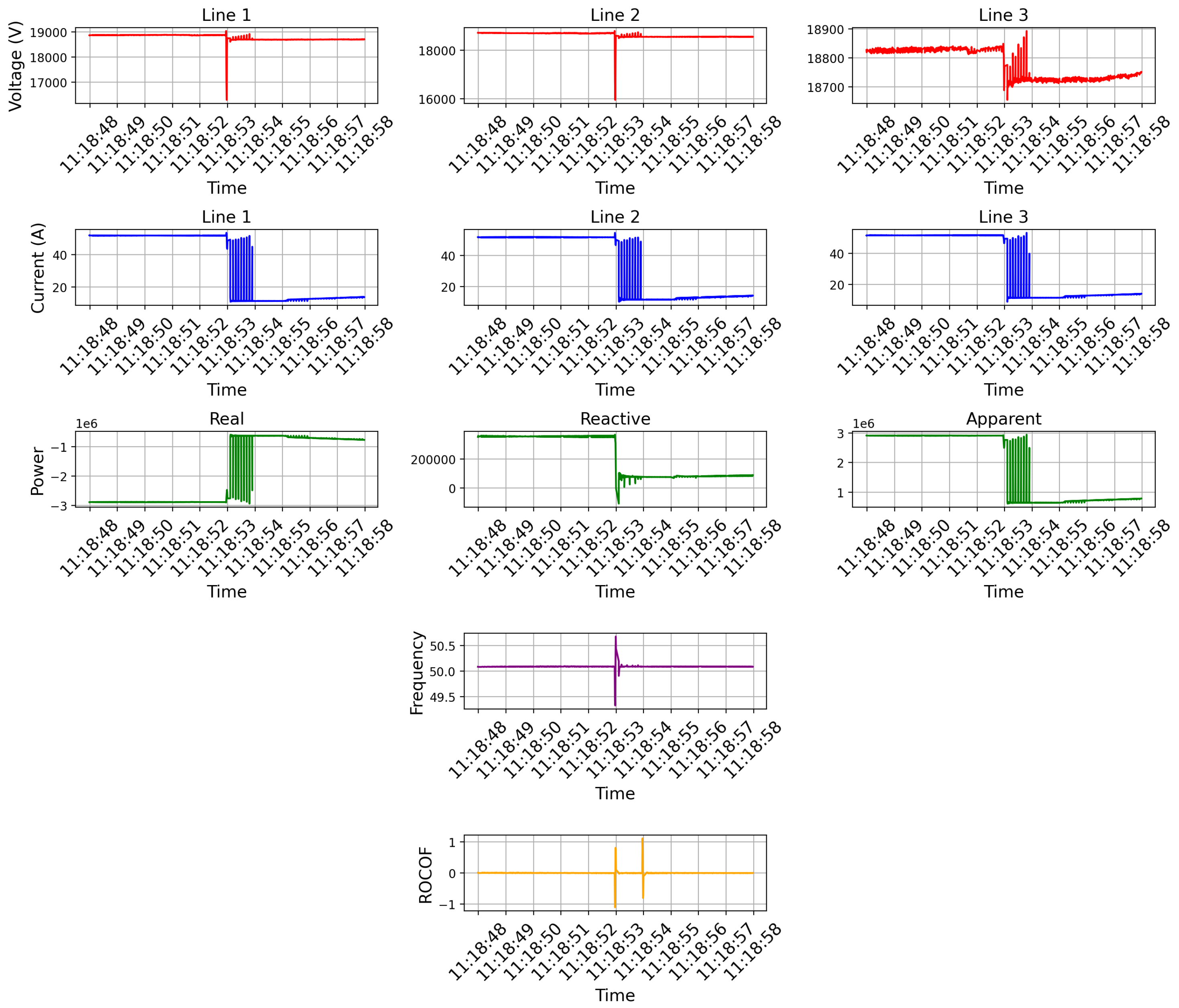

4. Results and Discussion

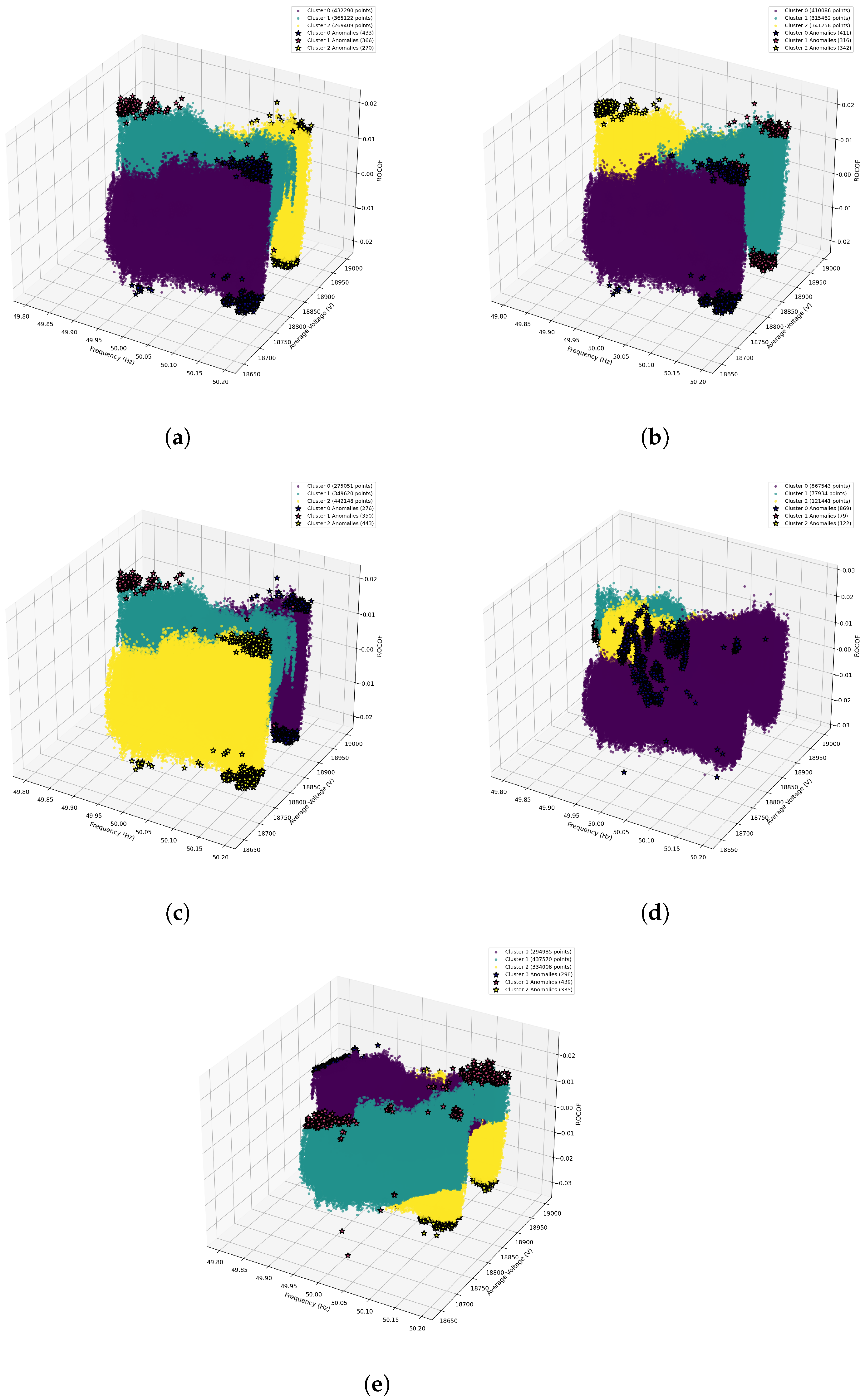

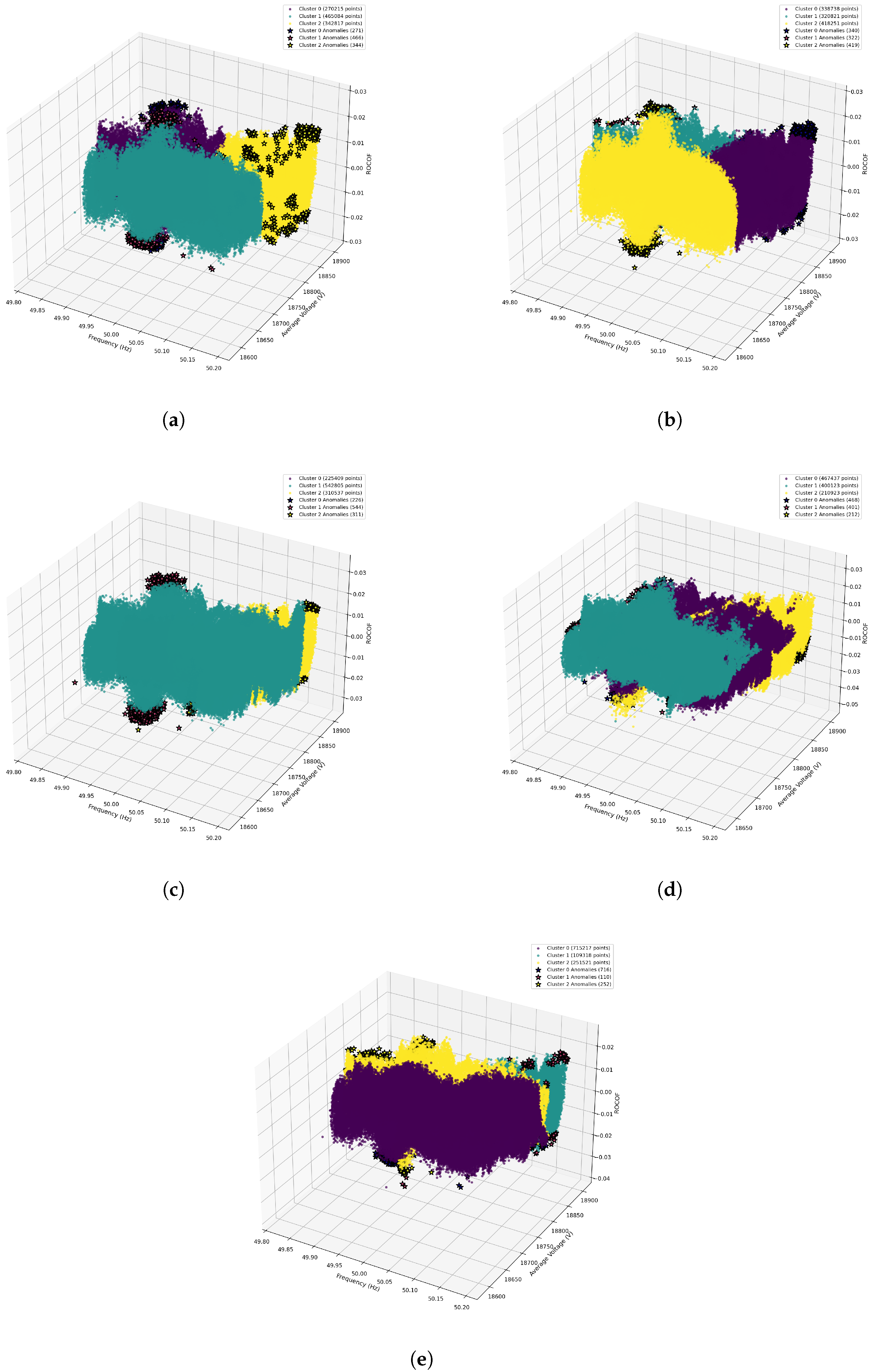

4.1. Clustering Model Comparison

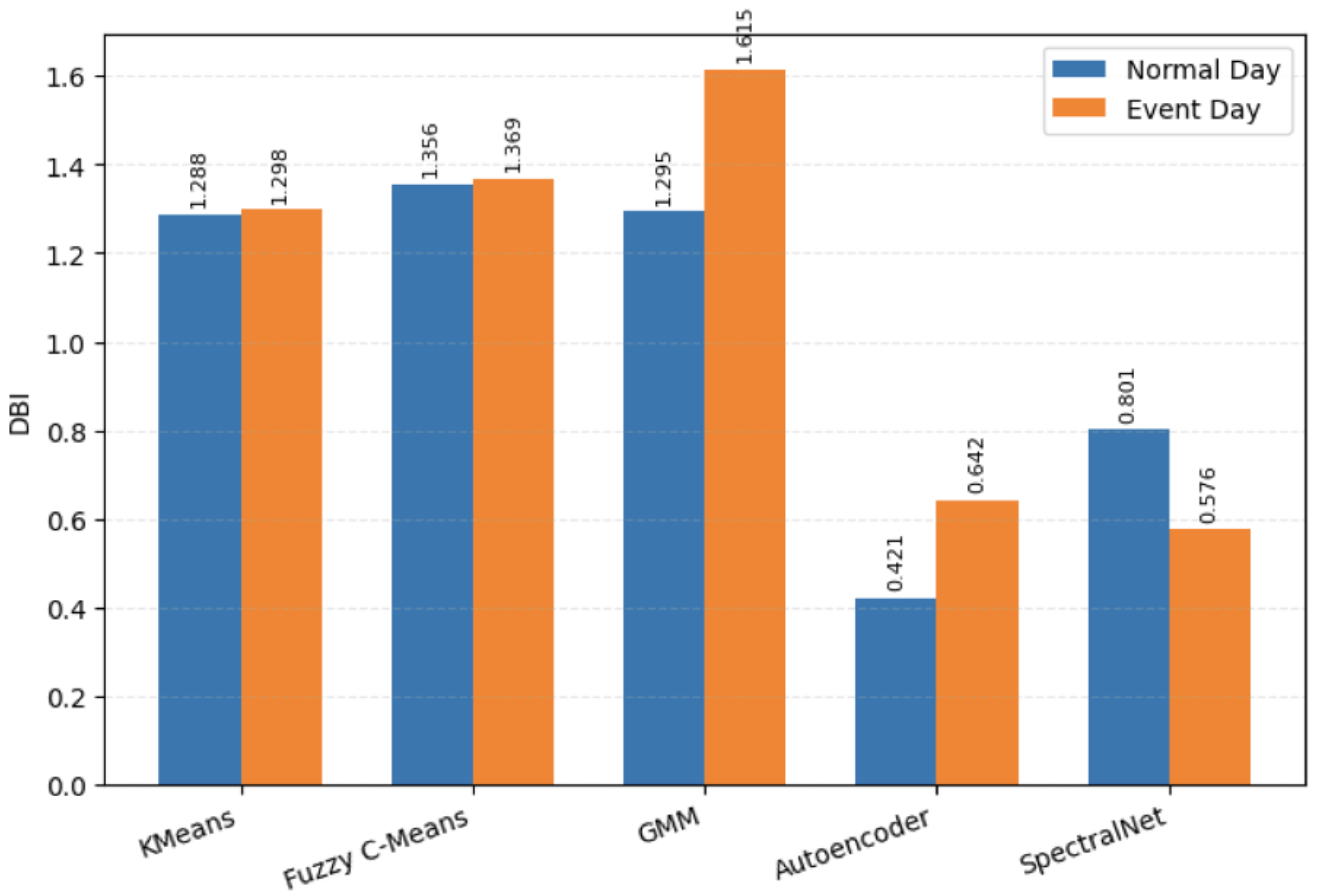

4.2. Model Performance Comparison

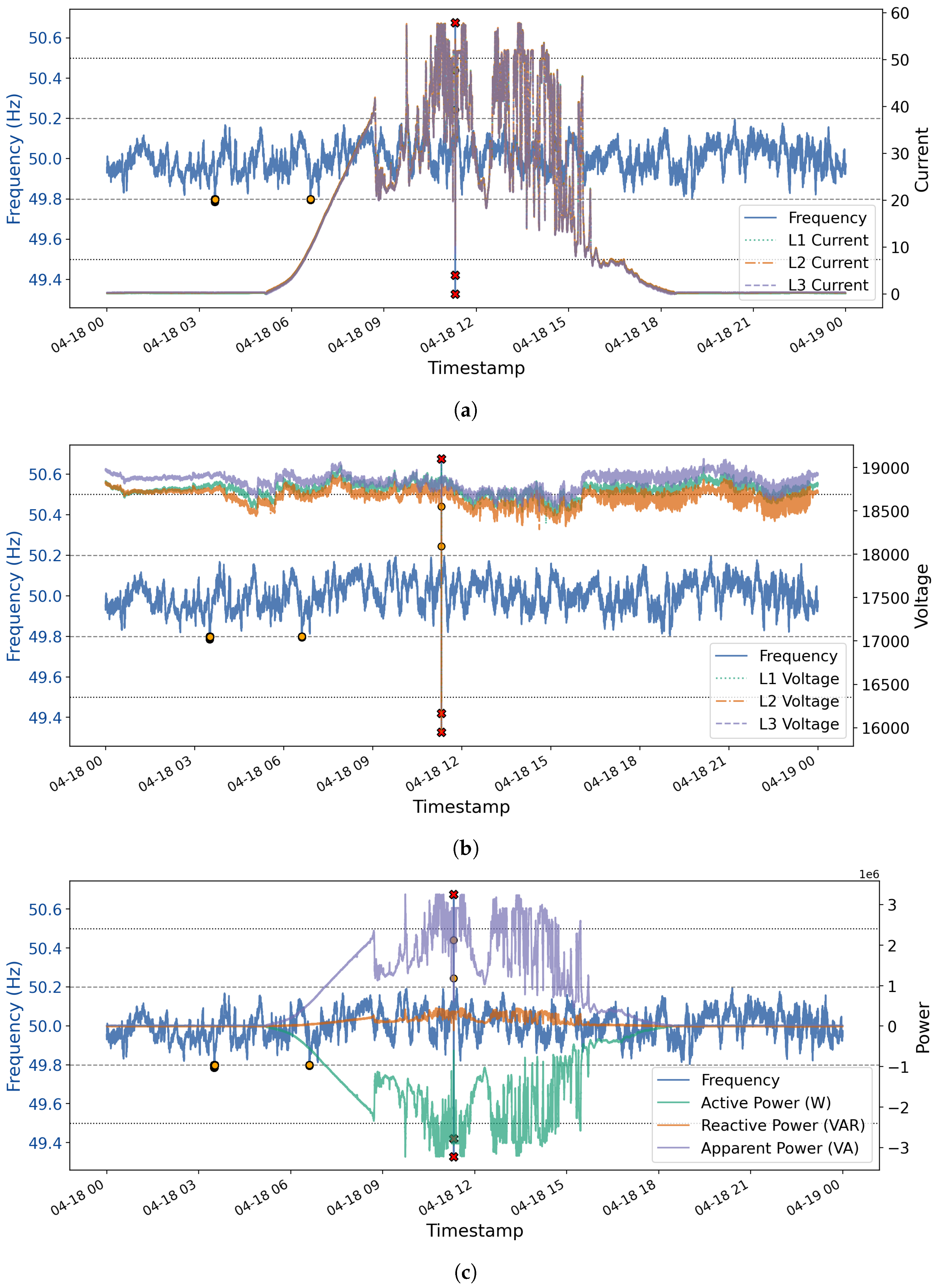

4.3. Root Cause Analysis: Hazardous Frequency Disturbance

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMU | Phasor Measurement Unit |

| PMU | Micro-Phasor Measurement Unit |

| GDU | Grid Data Unit |

| DBI | Davies–Bouldin Index |

| FCM | Fuzzy C-Means |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

| OE | Operational Event |

| HE | Hazardous Event |

| OR | Operational Range |

| HR | Hazardous Range |

| FRVCP | Frequency, ROCOF, Voltage, Current, and Power |

| ROCOF | Rate of Change of Frequency |

References

- Arghandeh, R.; Brady, K. Micro-synchrophasors for power distribution systems. Eng. Technol. Ref. 2016, 2016, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meydani, A.; Shahinzadeh, H.; Nafisi, H.; Gharehpetian, G.B. Synchrophasor Technology Applications and Optimal Placement of Micro-Phasor Measurement Unit (μPMU): Part II. In Proceedings of the 2024 28th International Electrical Power Distribution Conference (EPDC), Zanjan, Iran, 23–25 April 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, M.D.; Varadarajan, R. A review of machine learning approaches in synchrophasor technology. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 33520–33541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.; Rana, S.P.; Simmons, C.V.; Dudley, S. Solar farm voltage anomaly detection using high-resolution μPMU data-driven unsupervised machine learning. Appl. Energy 2021, 303, 117656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.; Dey, M.; Patel, P. Enabling Grid Stability: Harnessing μPMU Data for Data-Driven Analysis of Grid Frequency Events. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Frontiers of Intelligent Computing: Theory and Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, T.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Leao, B.; Fradkin, D. Unsupervised power system event detection and classification using unlabeled PMU data. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT Europe), Espoo, Finland, 18–21 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Guato Burgos, M.F.; Morato, J.; Vizcaino Imacaña, F.P. A review of smart grid anomaly detection approaches pertaining to artificial intelligence. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.B. Analysis of Synchrophasor Measurements for Cybersecurity and Situational Awareness in Power Distribution Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Riverside, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, M.; Nor, N.B.M.; Shiekh, M.A.; Alharthi, Y.Z.; Shutari, H.; Majeed, M.F. A Review on Microgrid Protection Challenges and Approaches to Address Protection Issues. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 175278–175303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, Ê.C.; Simoes, M.G.; Freitas, L.C.G. Anti-islanding techniques for integration of inverter-based distributed energy resources to the electric power system. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 17195–17230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.; Wickramarachchi, D.; Rana, S.P.; Simmons, C.V.; Dudley, S. Power grid frequency forecasting from μPMU data using hybrid vector-output LSTM network. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT EUROPE), Grenoble, France, 23–26 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jamei, M.; Scaglione, A.; Roberts, C.; Stewart, E.; Peisert, S.; McParland, C.; McEachern, A. Anomaly Detection Using Optimally Placed PMU Sensors in Distribution Grids. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 33, 3611–3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aligholian, A.; Shahsavari, A.; Stewart, E.M.; Cortez, E.; Mohsenian-Rad, H. Unsupervised event detection, clustering, and use case exposition in micro-pmu measurements. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 3624–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, D.; Yemula, P.K.; Pal, M. DynamoPMU: A physics informed anomaly detection, clustering, and prediction method using nonlinear dynamics on μ PMU measurements. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 3536309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Ghasemkhani, A.; Livani, H.; Centeno, V.A.; Chen, P.Y.; Zhang, J. Robust event classification using imperfect real-world PMU data. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 7429–7438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Qiu, R. Dimensionality increment of PMU data for anomaly detection in low observability power systems. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.08696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Liu, D.; Alnegheimish, S.; Cuesta-Infante, A.; Veeramachaneni, K. Tadgan: Time series anomaly detection using generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–13 December 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shahsavari, A.; Dubey, A.; Stewart, E.M. Situational Awareness in Distribution Grid Using Micro-PMU Data: A Machine Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Power & Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT), Washington, DC, USA, 17–20 February 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, N.M.; Janeiro, F.M.; Ramos, P.M. Deep learning for power quality event detection and classification based on measured grid data. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 9003311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrakar, R.; Dubey, R.K.; Panigrahi, B.K. Deep-Learning based Multiple Class Events Detection and Classification using Micro-PMU Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Green Energy and Applications (ICGEA), Singapore, 14–16 March 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Moazzen, F.; Hossain, M. Multivariate deep learning long short-term memory-based forecasting for microgrid energy management systems. Energies 2024, 17, 4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, Y.; Ishikawa, H. Handling concept drift in data-oriented power grid operations. Meas. Energy 2025, 7, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaledian, P.; Aligholian, A.; Mohsenian-Rad, H. Event-based analysis of solar power distribution feeder using micro-PMU measurements. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Power & Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT), Washington, DC, USA, 16–18 February 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, M.; Rana, S.P.; Wylie, J.; Simmons, C.V.; Dudley, S. Detecting power grid frequency events from μPMU voltage phasor data using machine learning. In Proceedings of the IET Conference Proceedings CP811; IET: London, UK, 2022; Volume 2022, pp. 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Aligholian, A.; Mohsenian-Rad, H. GraphPMU: Event clustering via graph representation learning using locationally-scarce distribution-level fundamental and harmonic PMU measurements. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 14, 2960–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, N.; Aminifar, F.; Mohsenian-Rad, H. Convolutional autoencoder anomaly detection and classification based on distribution PMU measurements. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2022, 16, 2816–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, A.C.; Zaidi, S.A.R.; McLernon, D. Autoencoder and incremental clustering-enabled anomaly detection. Electronics 2023, 12, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Kang, S.; Hwang, S.; Yoon, M.; Jang, G. Probabilistic optimal power flow-based spectral clustering method considering variable renewable energy sources. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 909611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Systems Catapult. Neuville Grid Data: Network Monitoring; Energy Systems Catapult: Birmingham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P. Comprehensive Guide to K-Means Clustering. 2019. Available online: https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2019/08/comprehensive-guide-k-means-clustering/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Cebeci, Z.; Yildiz, F. Comparison of K-Means and Fuzzy C-Means Algorithms on Different Cluster Structures. J. Agric. Inform. 2015, 6, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeeksforGeeks. Gaussian Mixture Model. GeeksforGeeks. Available online: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/machine-learning/gaussian-mixture-model/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Autoencoder, 2025. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autoencoder (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Tomar, A. Elbow Method in K-Means Clustering: Definition, Drawbacks, vs. Silhouette Score. GeeksforGeeks, 5 July 2025. Available online: https://builtin.com/data-science/elbow-method (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- GeeksforGeeks. Davies–Bouldin Index. GeeksforGeeks. Available online: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/machine-learning/davies-bouldin-index/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

| Category | Model | DBI (Normal Day) | DBI (Event Day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | K-Means | 1.2885 | 1.2985 |

| GMM | 1.2948 | 1.6152 | |

| Fuzzy C-Means | 1.3564 | 1.3689 | |

| Deep Learning | Autoencoder | 0.4208 | 0.6416 |

| SpectralNet | 0.8011 | 0.5755 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Modak, A.; Dey, M.; Patel, P.; Rana, S.P. SpectralNet-Enabled Root Cause Analysis of Frequency Anomalies in Solar Grids Using μPMU. Energies 2026, 19, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010268

Modak A, Dey M, Patel P, Rana SP. SpectralNet-Enabled Root Cause Analysis of Frequency Anomalies in Solar Grids Using μPMU. Energies. 2026; 19(1):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010268

Chicago/Turabian StyleModak, Arnabi, Maitreyee Dey, Preeti Patel, and Soumya Prakash Rana. 2026. "SpectralNet-Enabled Root Cause Analysis of Frequency Anomalies in Solar Grids Using μPMU" Energies 19, no. 1: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010268

APA StyleModak, A., Dey, M., Patel, P., & Rana, S. P. (2026). SpectralNet-Enabled Root Cause Analysis of Frequency Anomalies in Solar Grids Using μPMU. Energies, 19(1), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010268