A New Paradigm for Physics-Informed AI-Driven Reservoir Research: From Multiscale Characterization to Intelligent Seepage Simulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background: Classical Challenges and Digital Revolution in Reservoir Research

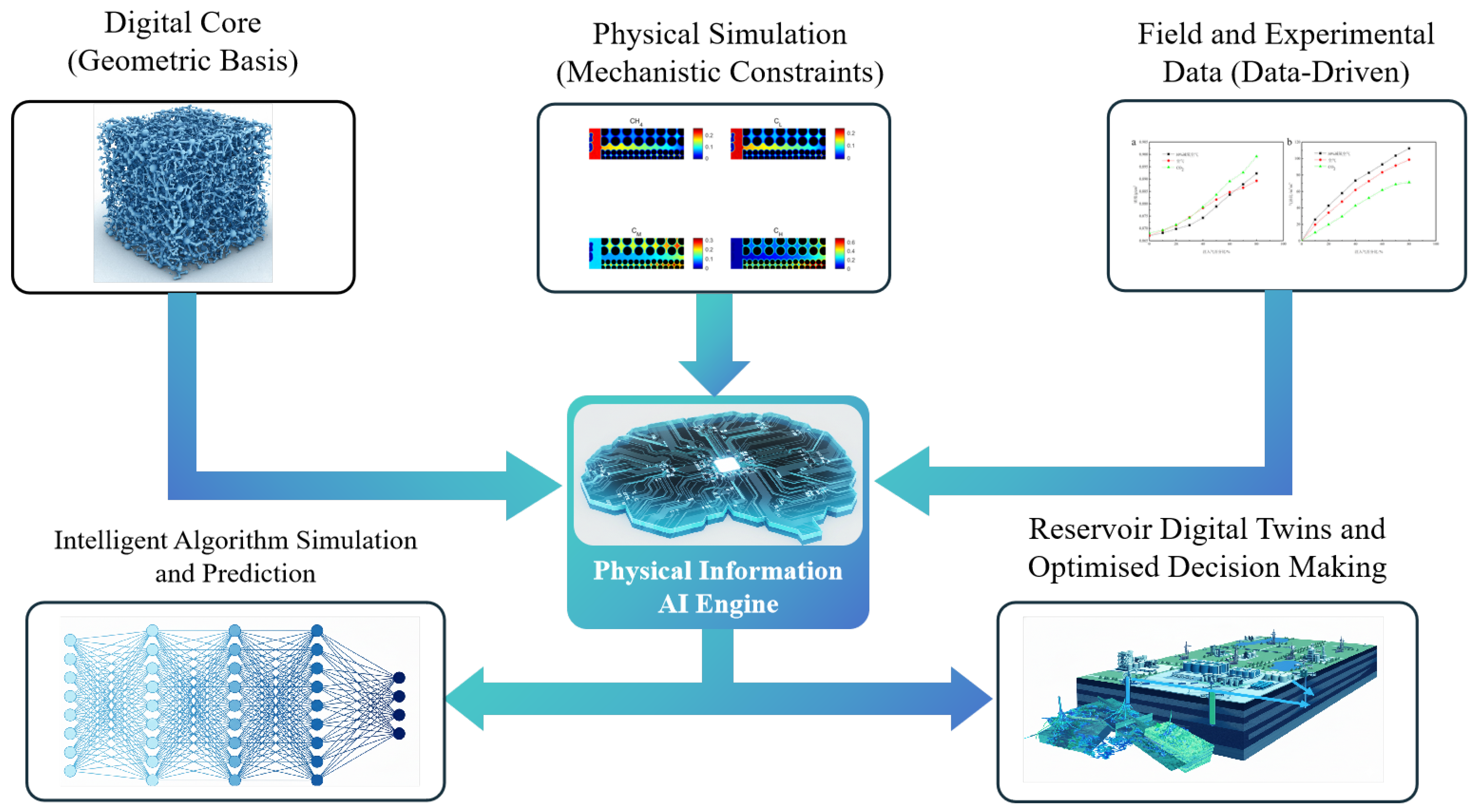

1.2. New Paradigm: The Trinity of Physical Mechanisms Plus Data Intelligence

2. AI-Enabled Multiscale Intelligent Characterization of Digital Cores

2.1. Limitations of Traditional Digital Core Reconstruction Techniques

2.2. AI-Driven Innovation in Core Characterization: From Image Processing to Physical Reality Reconstruction

2.2.1. Intelligent Segmentation and Analysis: 3D-CNN Applications and Topological Challenges

2.2.2. Generative Reconstruction: Application of GAN and Physical Fidelity Challenges

2.2.3. Super-Resolution Reconstruction: Trade-Off Between “Fidelity” and “Illusion” in Scale

3. Physical Mechanism-Driven Seepage Modeling: Sources of Constraints

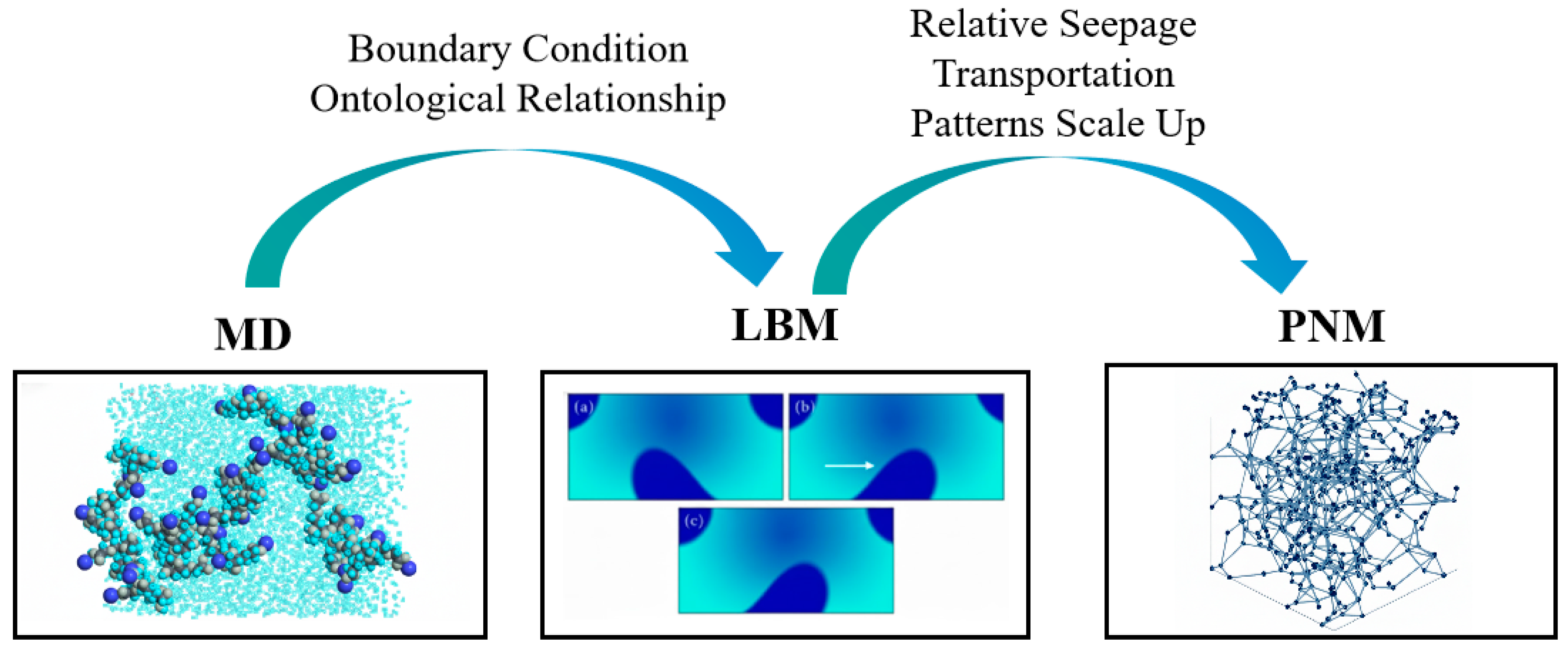

3.1. Core Modeling Approach: From Molecules to Cores

3.2. Physical Constraints, Realization Paths, and Challenges

4. The Core Engine: A Fusion Paradigm and Technology Path for Physics-Informed AI

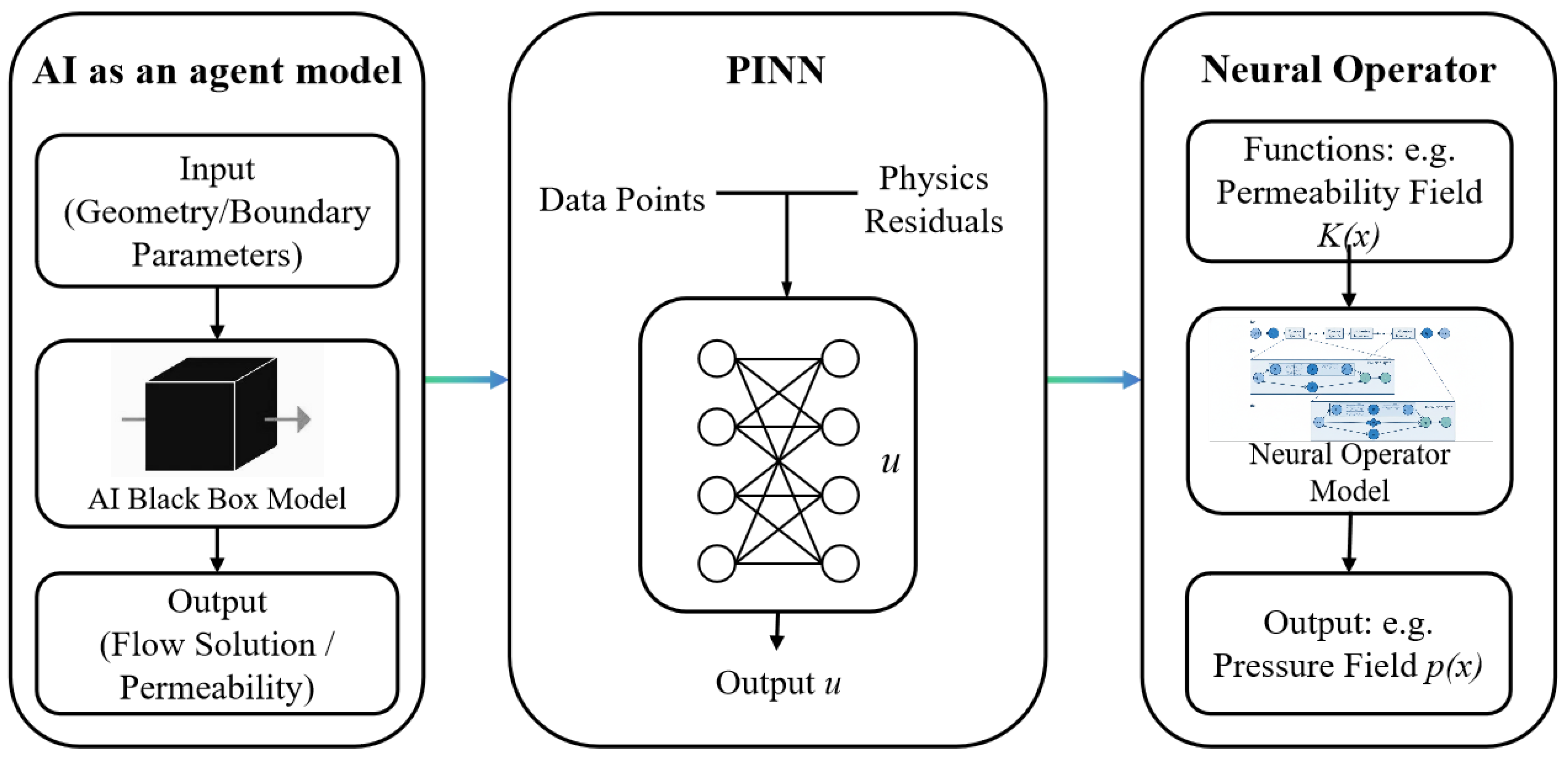

4.1. Methodological Evolution: From Substitution to Fusion to Operator Learning

4.1.1. Phase 1: AI as an Efficient Agent Model

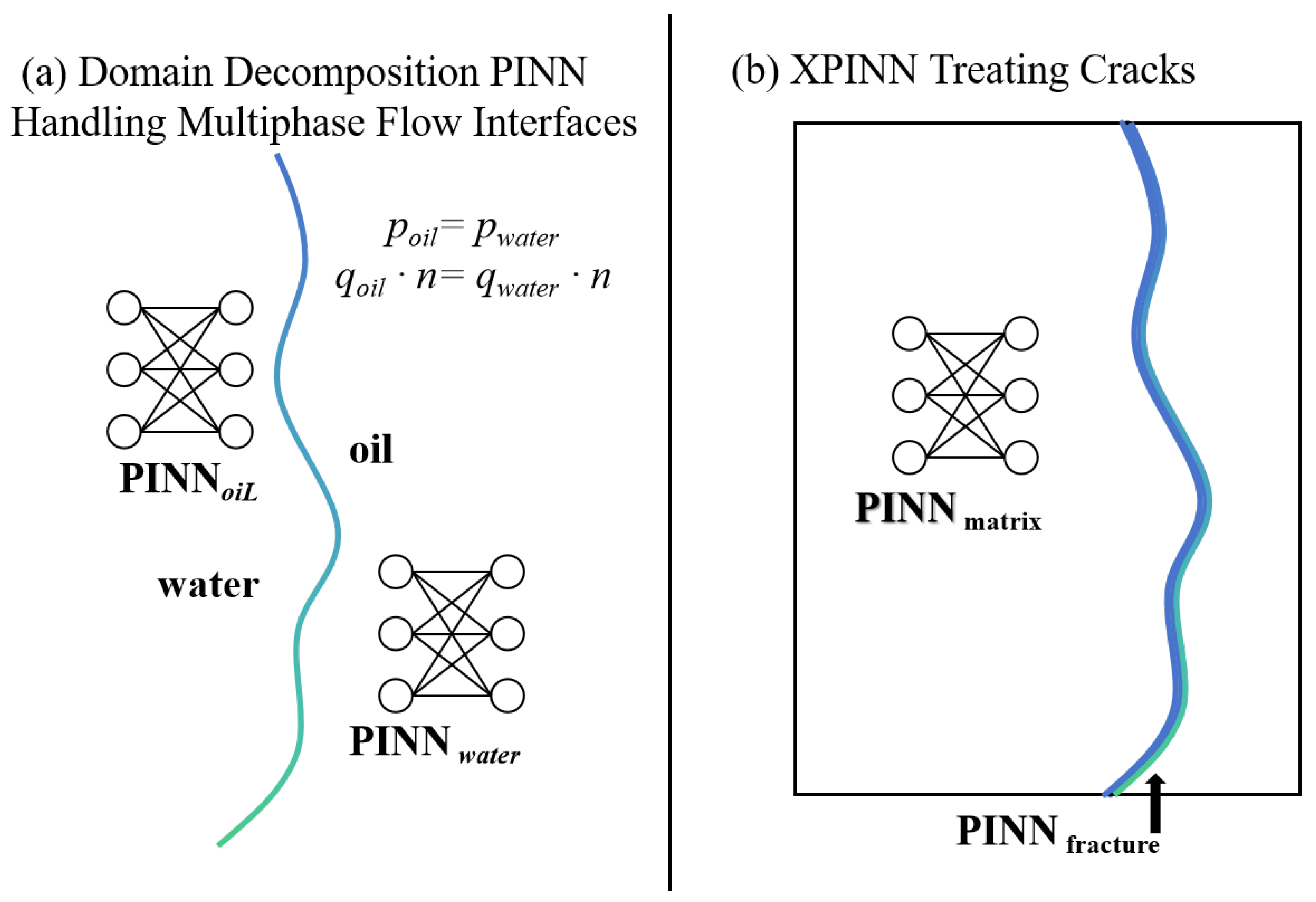

4.1.2. Phase 2: Deep Integration of Data and Physical Mechanisms with PINNs

- Advanced applications and challenges for multiphase flow problems:

- Advanced applications and challenges for cracked media problems:

- Extended PINN (eXtended PINN, XPINN): This method divides the whole simulation region into matrix and crack subdomains, deploys a regular PINN in each matrix subdomain, and uses a low-dimensional PINN to specifically address flow in the cracks. Finally, with the help of a coupling term describing fluid exchange between the matrix and cracks in the total loss function (the form of the coupling term can be found in classical models such as Warren–Root), the two systems are coupled.

- Physical knowledge-enhanced input features: This strategy modifies the input layer of the network by adding spatial coordinates (x, y), as well as one or more a priori features describing geometrical discontinuities, such as a “distance function to the nearest crack,” which help the network identify whether a point is inside the crack, close to it, or in the matrix region away from it. This a priori knowledge can help the network distinguish different physical behavior patterns inside the crack, near the crack, and in the matrix region away from the crack, which can be regarded as an implementation of physics-guided neural networks (PgNNs) [66].

4.1.3. Phase 3: The Revolution from “Data Interpolation” to “Operator Learning” with Neural Operators

4.2. Innovations in Technical Routes and Closed-Loop Systems

4.3. Scientific Validation and Model Credibility

4.4. Data Governance and Missing Parameter Prediction

5. Engineering Applications: From Digital Platform to Digital Twin

5.1. Construction of an Integrated Digital Platform for Exploration and Development

5.2. Toward Real-Time Decision-Making: The Reservoir Digital Twin

6. Current Challenges, Opportunities, and Frontiers

6.1. Key Bottlenecks

6.2. Future Frontier Technology Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CCUS | Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage |

| DNS | Direct Numerical Simulation |

| ES-MDA | Ensemble Smoother with Multiple Data Assimilation |

| FIB-SEM | Focused Ion Beam Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FNO | Fourier Neural Operator |

| FOV | Field of View |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| HR | High-Resolution |

| LBM | Lattice Boltzmann method |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LR | Low-Resolution |

| MD | Molecular Dynamics |

| Micro-CT | X-ray Micro-Computed Tomography |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MRT-LBM | Multiple Relaxation Time Lattice Boltzmann method |

| N-S equations | Navier–Stokes equations |

| NO | Neural Operator |

| PDE | Partial Differential Equation |

| PgNN | Physics-Guided Neural Network |

| PINN | Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| PNM | Pore Network Modeling |

| REV | Representative Elementary Volume |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| SR | Super-Resolution |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TgNN | Theory-Guided Neural Network |

| TL | Transfer Learning |

| TXM | Transmission X-ray Microscopy |

| UHS | Underground Hydrogen Storage |

| XPINN | Extended Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| Variables/Symbols | Definition |

| Permeability field function | |

| Pressure field function | |

| u | Flow velocity or solution variable |

| q | Fluid flux |

| n | Normal vector to the interface |

| Porosity | |

| Pressure of the oil phase | |

| Pressure of the water phase | |

| Coefficient of determination |

References

- Ranjbarzadeh, R.; Sappa, G. Numerical and Experimental Study of Fluid Flow and Heat Transfer in Porous Media: A Review Article. Energies 2025, 18, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazikeh, S.; Mohammadzadeh, O.; Zendehboudi, S. Characterization and Multiphase Flow of Oil/CO2 Systems in Porous Media Focusing on Asphaltene Precipitation: A Systematic Review. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 247, 213554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, H. Numerical Simulation of Multiphase Multi-Physics Flow in Underground Reservoirs: Frontiers and Challenges. Capillarity 2024, 12, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmani, Y.; Anderson, T.; Wang, Y.; Aryana, S.A.; Battiato, I.; Tchelepi, H.A.; Kovscek, A.R. Striving to Translate Shale Physics across Ten Orders of Magnitude: What Have We Learned? Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 223, 103848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Du, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, Z. Research Progress on Micro/Nanopore Flow Behavior. Molecules 2025, 30, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yu, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Chen, P.; Xu, L. Perspectives on Molecular Simulation of CO2/CH4 Competitive Adsorption in a Shale Matrix: A Review. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 15935–15971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negash, B.M.; Yaw, A.D. Artificial Neural Network Based Production Forecasting for a Hydrocarbon Reservoir under Water Injection. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpisheh, M.; Ebrahimpour, B.; Fattahi, A.; Siavashi, M.; Mir, H.; Mashhadimoslem, H.; Abdol, M.A.; Ghorbani, M.; Shokri, J.; Niblett, D.; et al. Leveraging Machine Learning in Porous Media. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 20717–20782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helle, H.B.; Bhatt, A.; Ursin, B. Porosity and Permeability Prediction from Wireline Logs Using Artificial Neural Networks: A North Sea Case Study. Geophys. Prospect. 2001, 49, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, J.; Jia, X.; Xu, S.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Integrating Scientific Knowledge with Machine Learning for Engineering and Environmental Systems. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongqing, S.; Shuyi, D.; Jiulong, W.; Junming, L.; Chiyu, X. Development of digital intelligence fluid dynamics and applications in the oil & gas seepage fields. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2023, 55, 765–791. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.D.; Akbar, M.; Vissapragada, B.; Walkden, G.M. Rock Types and Permeability Prediction from Dipmeter and Image Logs: Shuaiba Reservoir (Aptian), Abu Dhabi. AAPG Bull. 2002, 86, 1709–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonggang, W.; Youxi, Y. Methods of comprehensive geophysical data for prediction of porosity and analysis of its application. Oil Geophys. Prospect. 2001, 36, 707–715. [Google Scholar]

- Saraf, S.; Bera, A. A Review on Pore-Scale Modeling and CT Scan Technique to Characterize the Trapped Carbon Dioxide in Impermeable Reservoir Rocks during Sequestration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanematsu, P.C.; Thompson, K.E.; Willson, C.S. Pore-Scale Modeling of Nanoparticle Transport and Retention in Real Porous Materials. Comput. Geosci. 2019, 127, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmani, A.; Verma, R.; Prodanovic, M. Pore-Scale Modeling of Carbonates. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 114, 104141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishola, O.; Vilcaez, J. Augmenting X-ray Micro-CT Data with MICP Data for High Resolution Pore-Scale Simulations of Flow Properties of Carbonate Rocks. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 239, 212982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Liu, J.; Cui, M. A New Method to Reconstruct Structured Mesh Model from Micro Computed Tomography Images of Porous Media and Its Application. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 109, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Tian, S.; Xue, H.; Lu, S.; Liu, B.; Erastova, V.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y. A Novel Method for Automatic Quantification of Different Pore Types in Shale Based on SEM-EDS Calibration. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2025, 173, 107278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, C.; Enzmann, F.; Kersten, M. Pore Scale Modelling of Calcite Cement Dissolution in a Reservoir Sandstone Matrix. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 98, 05010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lu, B.; Yuan, Z.; Zhou, W.; Liu, B.; Jiang, K. Prediction of Both Diffusive and Hydraulic Conductance in the Pore Network Model Extracted from 3D Images Using Deep Learning. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 33, 025022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Blunt, M.J.; Armstrong, R.T.; Mostaghimi, P. Deep Learning in Pore Scale Imaging and Modeling. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 215, 103555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Shabaninejad, M.; Armstrong, R.T.; Mostaghimi, P. Deep neural networks for improving physical accuracy of 2D and 3D multi-mineral segmentation of rock micro-CT images. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 104, 107185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidian, M.; Miri, R.; Fazeli, H. Generative adversarial network-based super-resolution of subsurface rock images: Visual, petrophysical, and flow simulation assessment. Adv. Water Resour. 2026, 207, 105184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Qiao, R. Physics-constrained deep learning for data assimilation of subsurface transport. Energy AI 2021, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.R.; Kumawat, V.; Ganguly, S. Convolutional Neural Network Based Prediction of Effective Diffusivity from Microscope Images. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 131, 214901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shen, T.; Dong, Y.; Du, Y. 3D-FGAN: A 3D Stochastic Reconstruction Method of Digital Cores. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 233, 212590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Hou, Z.; Liu, Q.; Fu, F. Reconstruction of Three-Dimension Digital Rock Guided by Prior Information with a Combination of InfoGAN and Style-Based GAN. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Bijeljic, B.; Blunt, M.J. Generation of Pore-Space Images Using Improved Pyramid Wasserstein. Adv. Water Resour. 2024, 190, 104748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, F.; Cai, J. 3D Tight Sandstone Digital Rock Reconstruction with Deep Learning. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 207, 109020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, K.M.; Anderson, T.I.; Creux, P.; Kovscek, A.R. Reconstructing Porous Media Using Generative Flow Networks. Comput. Geosci. 2021, 156, 104905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Wang, Y.D.; Mostaghimi, P.; Swietojanski, P.; Armstrong, R.T. An Innovative Application of Generative Adversarial Networks for Physically Accurate Rock Images with an Unprecedented Field of View. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL089029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chang, B.; Prodanovic, M.; Pyrcz, M.J. AI-based Digital Rocks Augmentation and Assessment Metrics. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR037939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Ruan, L.; Xiang, Z.; Hu, X. Permeability Prediction of Complex Porous Materials by Conjugating Generative Adversarial and Convolutional Neural Networks. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 238, 112942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M. Enhancing Digital Rock Analysis through Generative Artificial Intelligence: Diffusion Models. Neurocomputing 2024, 587, 127676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.T.; Liao, Q.Z.; Yan, Z.T.; You, S.H.; Song, X.Z.; Tian, S.C.; Li, G.S. Stable Diffusion for High-Quality Image Reconstruction in Digital Rock Analysis. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2024, 12, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiff, D.; Schaeffer, B.P.; Pires, G.; Stojkovic, D.; Rapstine, T.; Ramos, F. Controlled Latent Diffusion Models for 3D Porous Media Reconstruction. Comput. Geosci. 2026, 206, 106038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; He, X.; Teng, Q.; Wu, X.; Cui, J.; Dong, X. PM-ARNN: 2D-TO-3D Reconstruction Paradigm for Microstructure of Porous Media via Adversarial Recurrent Neural Network. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 264, 110333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Saxena, N.; Hofmann, R.; Pradhan, C.; Hows, A. Enhancing Resolution of Micro-CT Images of Reservoir Rocks Using Super Resolution. Comput. Geosci. 2023, 170, 105265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslin, A.; Marsh, M.; Piche, N.; Provencher, B.; Mitchell, T.R.; Onederra, I.A.; Leonardi, C.R. Processing of Micro-CT Images of Granodiorite Rock Samples Using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Part I: Super-resolution Enhancement Using a 3D CNN. Miner. Eng. 2022, 188, 107748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Armstrong, R.T.; Mostaghimi, P. Enhancing Resolution of Digital Rock Images with Super Resolution Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 182, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, Q.; Yang, J.; Shang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Recent Advances in Multiscale Digital Rock Reconstruction, Flow Simulation, and Experiments during Shale Gas Production. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 2475–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.J.; Niu, Y.; Manoorkar, S.; Mostaghimi, P.; Armstrong, R.T. Deep Learning of Multiresolution X-ray Micro-Computed-Tomography Images for Multiscale Modeling. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2022, 17, 054046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizhani, M.; Ardakani, O.H.; Little, E. Reconstructing High Fidelity Digital Rock Images Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, V.R.; Gupta, U.; Rapole, S.R.; Saxena, N.; Hofmann, R.; Day-Stirrat, R.J.; Prakash, J.; Yalavarthy, P.K. Siamese-SR: A Siamese Super-Resolution Model for Boosting Resolution of Digital Rock Images for Improved Petrophysical Property Estimation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 3479–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, S.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, M.; Cao, X.; Wang, X. Ultrahigh-Resolution Reconstruction of Shale Digital Rocks from FIB-SEM Images Using Deep Learning. SPE J. 2024, 29, 1434–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.I.; Vega, B.; McKinzie, J.; Aryana, S.A.; Kovscek, A.R. 2D-to-3D Image Translation of Complex Nanoporous Volumes Using Generative Networks. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, N.; Huysmans, M.; Swennen, R. Computed Tomography 3D Super-Resolution with Generative Adversarial Neural Networks: Implications on Unsaturated and Two-Phase Fluid Flow. Materials 2020, 13, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiribocchi, A.; Durve, M.; Lauricella, M.; Montessori, A.; Tucny, J.M.; Succi, S. Lattice Boltzmann Simulations for Soft Flowing Matter. Phys. Rep.-Rev. Sect. Phys. Lett. 2025, 1105, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunt, M.; Jackson, M.; Piri, M.; Valvatne, P. Detailed physics, predictive capabilities and macroscopic consequences for pore-network models of multiphase flow. Adv. Water Resour. 2002, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Xu, H.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H.; Micheal, M.; Yuan, X.; Wu, H. Fast Prediction of Methane Adsorption in Shale Nanopores Using Kinetic Theory and Machine Learning Algorithm. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdes, C.; Petit, C.; Mejia, A.; Muller, E.A. Combined Experimental, Theoretical, and Molecular Simulation Approach for the Description of the Fluid-Phase Behavior of Hydrocarbon Mixtures within Shale Rocks. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 5750–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleini, M.M.; Badizad, M.H.; Kargozarfard, Z.; Ayatollahi, S. Interactions between Rock/Brine and Oil/Brine Interfaces within Thin Brine Film Wetting Carbonates: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 7983–7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiguo, X.; Jie, C.; Jiahui, S.; Dawei, C.; Zhihua, C. Progress of discrete Boltzmann study on multiphase complex flows. Acta Aerodyn. Sin. 2021, 39, 138–169. [Google Scholar]

- Erskine, A.N.; Jin, J.; Lin, C.L.; Miller, J.D.; Wang, S. 3D Imaging of Leach Columns from Rochester Mine for Pore Network Characteristics and Permeability Simulated by the Lattice Boltzmann Method. Hydrometallurgy 2024, 228, 106365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, T. Modeling Snap-Off during Gas-Liquid Flow by Using Lattice Boltzmann Method. Energies 2024, 17, 4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ju, Y.; Wang, N.; Xi, G.; Zhang, Y. Lattice Boltzmann Modeling of Contact Angle and Its Hysteresis in Two-Phase Flow with Large Viscosity Difference. Phys. Rev. E 2015, 92, 033306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, F.; Del Carro, L.; Moqaddam, A.M.; Kang, Q.; Brunschwiler, T.; Derome, D.; Carmeliet, J. Study of Non-Isothermal Liquid Evaporation in Synthetic Micro-Pore Structures with Hybrid Lattice Boltzmann Model. J. Fluid Mech. 2019, 866, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibbaro, S.; Costa, E.; Dimitrov, D.I.; Diotallevi, F.; Milchev, A.; Palmieri, D.; Pontrelli, G.; Succi, S. Capillary Filling in Microchannels with Wall Corrugations: A Comparative Study of the Concus-Finn Criterion by Continuum, Kinetic, and Atomistic Approaches. Langmuir 2009, 25, 12653–12660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golsanami, N.; Jayasuriya, M.N.; Yan, W.; Fernando, S.G.; Liu, X.; Cui, L.; Zhang, X.; Yasin, Q.; Dong, H.; Dong, X. Characterizing Clay Textures and Their Impact on the Reservoir Using Deep Learning and Lattice-Boltzmann Simulation Applied to SEM Images. Energy 2022, 240, 122599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.T.; McClure, J.E.; Berrill, M.A.; Rucker, M.; Schlueter, S.; Berg, S. Beyond Darcy’s Law: The Role of Phase Topology and Ganglion Dynamics for Two-Fluid Flow. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 94, 043113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Qin, F.; Derome, D.; Carmeliet, J. Simulation of Quasi-Static Drainage Displacement in Porous Media on Porescale: Coupling Lattice Boltzmann Method and Pore Network Model. J. Hydrol. 2020, 588, 125080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchi, D.; Battiato, I. The Impact of Pore-Scale Flow Regimes on Upscaling of Immiscible Two-Phase Flow in Porous Media. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 6683–6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Helland, J.O.; Jettestuen, E. Dynamic Capillary Pressure Curves from Pore-Scale Modeling in Mixed-Wet-Rock Images. SPE J. 2013, 18, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcato, A.; Boccardo, G.; Marchisio, D. From Computational Fluid Dynamics to Structure Interpretation via Neural Networks: An Application to Flow and Transport in Porous Media. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 8530–8541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faroughi, S.A.; Pawar, N.M.; Fernandes, C.; Raissi, M.; Das, S.; Kalantari, N.K.; Kourosh Mahjour, S. Physics-Guided, Physics-Informed, and Physics-Encoded Neural Networks and Operators in Scientific Computing: Fluid and Solid Mechanics. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2024, 24, 040802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.; Li, Z.; Azizzadenesheli, K.; Anandkumar, A.; Benson, S.M. U-FNO-An enhanced Fourier neural operator-based deep-learning model for flow. Adv. Water Resour. 2022, 163, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcato, A.; Santos, J.E.; Boccardo, G.; Viswanathan, H.; Marchisio, D.; Prodanovic, M. Prediction of Local Concentration Fields in Porous Media with Chemical Reaction Using a Multi Scale Convolutional Neural Network. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455, 140367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitska, M.; Cassola, S.; Schmidt, T.; Duhovic, M.; Basok, B.; May, D. Microscale Domain Permeability Prediction of Fiber Reinforcement Structures Based on the Lattice Boltzmann Method and Machine Learning. J. Porous Media 2025, 28, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, M.; Chen, B.; Wang, J.; Xiao, D.; Luo, M.; Evans, B. A Data-Driven Framework for Permeability Prediction of Natural Porous Rocks via Microstructural Characterization and Pore-Scale Simulation. Eng. Comput. 2023, 39, 3895–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, I.; Tripathi, B.K.; Singh, A. Velocity Field Prediction for Digital Porous Media Using Attention-Based Deep Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 314, 121825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalamanchi, P.; Gupta, S.D. Estimation of Pore Structure and Permeability in Tight Carbonate Reservoir Based on Machine Learning (ML) Algorithm Using SEM Images of Jaisalmer Sub-Basin, India. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akmal, F.; Nurcahya, A.; Alexandra, A.; Yulita, I.N.; Kristanto, D.; Dharmawan, I.A. Application of Machine Learning for Estimating the Physical Parameters of Three-Dimensional Fractures. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 12037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Mao, S.; Carbonero, A.; Srikishan, B.; Creasy, N.; Chellal, H.; Mehana, M. Deep Learning-Based Surrogate Modeling for Underground Hydrogen Storage. Adv. Water Resour. 2025, 203, 105014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Chen, B.; Malki, M.; Chen, F.; Morales, M.; Ma, Z.; Mehana, M. Efficient Prediction of Hydrogen Storage Performance in Depleted Gas Reservoirs Using Machine Learning. Appl. Energy 2024, 361, 122914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Xia, X.; Tian, Z.; Qin, X.; Cai, J. Lattice Boltzmann Prediction of CO2 and CH4 Competitive Adsorption in Shale Porous Media Accelerated by Machine Learning for CO2 Sequestration and Enhanced CH4 Recovery. Appl. Energy 2024, 370, 123638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yu, H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Hong, X.; Wu, H. Fast and Accurate Calculation on CO2/CH4 Competitive Adsorption in Shale Nanopores: From Molecular Kinetic Theory to Machine Learning Model. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraireh, M. Enhancing Unsteady Heat Transfer Simulation in Porous Media through the Application of Convolutional Neural Networks. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 015516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhu, H.; Qu, Z. Constraint-Incorporated Deep Learning Model for Predicting Heat Transfer in Porous Media under Diverse External Heat Fluxes. Energy AI 2024, 18, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R.; Wang, H.; Xiao, L. Reservoir Evaluation Using Petrophysics Informed Machine Learning: A Case Study. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 2024, 5, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Takbiri-Borujeni, A.; Takbiri, S.; Kazemi, A. Physics-Informed Data-Driven Model for Fluid Flow in Porous Media. Comput. Fluids 2023, 264, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Xia, Y.; Cai, J. Single Phase Flow Simulation in Porous Media by Physical-Informed Unet Network Based on Lattice Boltzmann Method. J. Hydrol. 2024, 639, 131501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Jadidi, M.; Mahmoudi, Y. Hidden Field Discovery of Turbulent Flow over Porous Media Using Physics-Informed Neural Networks. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 125158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zhang, C.; Ma, H.; Hou, M. Research on physical information neural network method for reservoir performance prediction. Petrochem. Ind. Appl. 2023, 42, 11–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Jiang, A.; Faulder, D.; Cladouhos, T.T.; Jafarpour, B. Physics-Guided Deep Learning for Prediction of Energy Production from Geothermal Reservoirs. Geothermics 2024, 116, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Liu, Z.; Kang, Z.; Pang, Y. Data-Driven Optimization Study of the Multi-Relaxation-Time Lattice Boltzmann Method for Solid-Liquid Phase Change. Appl. Math. Mech.-Engl. Ed. 2023, 44, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Saleem, S.; Ghaderi, M. Using Artificial Neural Network to Optimize the Flow and Natural Heat Transfer of a Magnetic Nanofluid in a Square Enclosure with a Fin on Its Vertical Wall: A Lattice Boltzmann Simulation. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021, 145, 2261–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Chung, T.; Armstrong, R.T.; Mostaghimi, P. ML-LBM: Predicting and Accelerating Steady State Flow Simulation in Porous Media with Convolutional Neural Networks. Transp. Porous Media 2021, 138, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yan, B.; Aslam, B.; Kang, Q.; Harp, D.; Pawar, R. Deep Learning Accelerated Inverse Modeling and Forecasting for Large-Scale Geologic CO2 Sequestration. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2025, 144, 104383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Qin, G.Y.; Zhang, L.M.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Y.F.; Yao, J.; Wang, J.L.; Dai, Q.Y.; Wu, D.W. A Dual-Porosity Flow-Net Model for Simulating Water-Flooding in Low-Permeability Fractured Reservoirs. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 240, 213069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanin, E.; Garipova, A.; Boronin, S.; Vanovskiy, V.; Vainshtein, A.; Afanasyev, A.; Osiptsov, A.; Burnaev, E. Combined Mechanistic and Machine Learning Method for Construction of Oil Reservoir Permeability Map Consistent with Well Test Measurements. Pet. Res. 2025, 10, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasianakis, N.I.; Haller, R.; Mahrous, M.; Poonoosamy, J.; Pfingsten, W.; Churakov, S.V. Neural Network Based Process Coupling and Parameter Upscaling in Reactive Transport Simulations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2020, 291, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabipour, I.; Raoof, A.; Cnudde, V.; Aghaei, H.; Qajar, J. A Computationally Efficient Modeling of Flow in Complex Porous Media by Coupling Multiscale Digital Rock Physics and Deep Learning: Improving the Tradeoff between Resolution and Field-of-View. Adv. Water Resour. 2024, 188, 104695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, A.; Babaei, M. Hybrid Pore-Network and Lattice-Boltzmann Permeability Modelling Accelerated by Machine Learning. Adv. Water Resour. 2019, 126, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Xia, L.; Xu, H.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Cremaschi, L. Effect of Internal Structure on Dynamically Coupled Heat and Moisture Transfer in Closed-Cell Thermal Insulation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 185, 122391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Li, J.; Wu, K.; Chen, Z.; Gao, Y.; Feng, D.; Zhang, S.; Li, F. A data-driven flow surrogate model based on a data-driven and physics-driven method. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2023, 30, 104–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuwei, L.; Zijian, L.; Lifei, S.; Fuchun, T.; Jizhou, T. A new physics-informed method for the fracability evaluation of shale oil reservoirs. Coal Geol. Explor. 2023, 51, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Krokos, V.; Bordas, S.P.A.; Kerfriden, P. A Graph-Based Probabilistic Geometric Deep Learning Framework with Online Enforcement of Physical Constraints to Predict the Criticality of Defects in Porous Materials. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2024, 286, 112545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, A.; Cheng, L.; Aghighi, M.A.; Masoumi, H.; Roshan, H. A Novel Workflow Based on Physics-Informed Machine Learning to Determine the Permeability Profile of Fractured Coal Seams Using Downhole Geophysical Logs. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 131, 105171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Feng, W.; Yu, J.; Chen, F.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, S.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y. Recent Advances in Geological Storage: Trapping Mechanisms, Storage Sites, Projects, and Application of Machine Learning. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 10087–10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mudhafar, W.J.; Hasan, A.A.; Abbas, M.A.; Wood, D.A. Machine Learning with Hyperparameter Optimization Applied in Facies-Supported Permeability Modeling in Carbonate Oil Reservoirs. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Kong, Q.; Morris, J.P. Multi-Fidelity Fourier Neural Operator for Fast Modeling of Large-Scale Geological Carbon Storage. J. Hydrol. 2024, 629, 130641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Zhu, M.; Xi, Z.; Wang, K.; Yuan, Y.O.; Lu, L. Efficient and Generalizable Nested Fourier-DeepONet for Three-Dimensional Geological Carbon Sequestration. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2024, 18, 2435457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Gong, Z.; Kang, X.; Yao, W. Multi-Fidelity Prediction of Fluid Flow Based on Transfer Learning Using Fourier Neural Operator. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 077118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevicius, G.; Jonkus, K.; Pal, M. Advancing Darcy Flow Modeling: Comparing Numerical and Deep Learning Techniques. Processes 2025, 13, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; He, C.; Wei, N.; Jiang, R.; Zhu, P.; Hao, Z.; Hussain, W.; Ashraf, U. Optimizing Seismic-Based Reservoir Property Prediction: A Synthetic Data-Driven Approach Using Convolutional Neural Networks and Transfer Learning with Real Data Integration. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 58, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques Junior, A.; de Souza, E.M.; Muller, M.; Brum, D.; Zanotta, D.C.; Horota, R.K.; Kupssinsku, L.S.; Veronez, M.R.; Gonzaga, L.; Cazarin, C.L. Improving Spatial Resolution of Multispectral Rock Outcrop Images Using RGB Data and Artificial Neural Networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Perdikaris, P. Adversarial Uncertainty Quantification in Physics-Informed Neural Networks. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 394, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Sun, H.; Fan, D.; Zhang, L.; Imani, G.; Fu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yao, J. Flow Prediction of Heterogeneous Nanoporous Media Based on Physical Information Neural Network. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 125, 205307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Barajas-Solano, D.; Tartakovsky, G.; Tartakovsky, A.M. Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Multiphysics Data Assimilation with Application to Subsurface Transport. Adv. Water Resour. 2020, 141, 103610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, N.; Chang, H. Deep Learning of Two-Phase Flow in Porous Media via Theory-Guided Neural Networks. SPE J. 2022, 27, 1176–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashefi, A.; Mukerji, T. Prediction of Fluid Flow in Porous Media by Sparse Observations and Physics-Informed PointNet. Neural Netw. 2023, 167, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, L.; Liu, H.; Ren, Y.; Luo, K.; Shi, M.; Su, J.; Li, X. Application and Development Trend of Artificial Intelligence in Petroleum Exploration and Development. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitrievsky, A.N.; Eremin, N.A.; Safarova, E.A.; Stolyarov, V.E. Implementation of Complex Scientific and Technical Programs at the Late Stages of Operation of Oil and Gas Fields. Socar Proc. 2022, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topor, T. An Integrated Workflow for MICP-based Rock Typing: A Case Study of a Tight-Gas Sandstone Reservoir in the Baltic Basin (Poland). Nafta-Gaz 2020, 76, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinkia, M.; Amraeiniya, A.; Behboud, M.M.; Mehrad, M.; Bajolvand, M.; Gandomgoun, M.H.; Gandomgoun, M. A Novel Approach to Pore Pressure Modeling Based on Conventional Well Logs Using Convolutional Neural Network. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 211, 110156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Cui, L.; Su, J.; Wu, L.; Akter, S.; Kumar, A. Digital Servitization in Digital Enterprise: Leveraging Digital Platform Capabilities to Unlock Data Value. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 278, 109434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, Z.; AbouRizk, S. Automating Common Data Integration for Improved Data-Driven Decision-Support System in Industrial Construction. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2022, 36, 04021037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, E.B.M.; de Souza, D.G.B.; Copetti, A.; Sobral, A.P.B.; Silva, G.V.; Tammela, I.; Cardoso, R. Tools, Technologies and Frameworks for Digital Twins in the Oil and Gas Industry: An In-Depth Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 6457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovich, T.; Dron, E. Data Quality and Digital Twins in Decision Support Systems of Oil and Gas Companies. Adv. Intell. Syst. Res. 2020, 174, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.Y.; Zhao, X.G.; Xie, C.Y.; Zhu, J.W.; Wang, J.L.; Yang, J.S.; Song, H.Q. Data-Driven Production Optimization Using Particle Swarm Algorithm Based on the Ensemble-Learning Proxy Model. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 2951–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A. Data Driven-Based Model for Predicting Pump Failures in the Oil and Gas Industry. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 145, 107019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orru, P.F.; Zoccheddu, A.; Sassu, L.; Mattia, C.; Cozza, R.; Arena, S. Machine Learning Approach Using MLP and SVM Algorithms for the Fault Prediction of a Centrifugal Pump in the Oil and Gas Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhizkar, T.; Hogenboom, S.; Vinnem, J.E.; Utne, I.B. Data Driven Approach to Risk Management and Decision Support for Dynamic Positioning Systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 201, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essenfelder, A.H.; Larosa, F.; Mazzoli, P.; Bagli, S.; Broccoli, D.; Luzzi, V.; Mysiak, J.; Mercogliano, P.; dalla Valle, F. Smart Climate Hydropower Tool: A Machine-Learning Seasonal Forecasting Climate Service to Support Cost-Benefit Analysis of Reservoir Management. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleiti, A.K.; Al-Ammari, W.A.; Vesely, L.; Kapat, J.S. Carbon Dioxide Transport Pipeline Systems: Overview of Technical Characteristics, Safety, Integrity and Cost, and Potential Application of Digital Twin. J. Energy Resour. Technol.-Trans. ASME 2022, 144, 092106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, H.; Bao, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, D. Intelligent Risk Prognosis and Control of Foundation Pit Excavation Based on Digital Twin. Buildings 2023, 13, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahlot, A.P.; Orozco, R.; Yin, Z.; Bruer, G.; Herrmann, F.J. An Uncertainty-Aware Digital Shadow for Underground Multimodal CO2 Storage Monitoring. Geophys. J. Int. 2025, 242, ggaf176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, F.I.; Muther, T.; Dahaghi, A.K.; Neghabhan, S. CO2 EOR Performance Evaluation in an Unconventional Reservoir through Mechanistic Constrained Proxy Modeling. Fuel 2022, 310, 122390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Ma, M.; Viswanathan, H.; Pawar, R.; Jha, B.; Chen, B. Deep Learning-Assisted Multiobjective Optimization of Geological CO2 Storage Performance under Geomechanical Risks. SPE J. 2025, 30, 2073–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Al-Alawi, A.; Nikoo, M.R.; Elzain, H.E. Sensitivity Analysis of a Dual-Continuum Model System for Integrated CO2 Sequestration and Geothermal Extraction in a Fractured Reservoir. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 72, 104053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, K.; Tian, Y. Deep Graph Learning-Based Surrogate Model for Inverse Modeling of Fractured Reservoirs. Mathematics 2024, 12, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingaro, G.; Ardakani, S.H.; Gracie, R.; Leonenko, Y. Deep Learning Assisted Monitoring Framework for Geological Carbon Sequestration. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2025, 144, 104372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wei, X.; Liu, Q.; Sun, W.; Ma, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, C. Lattice Boltzmann Method and Back-Propagation Artificial Neural Network-Based Coke Mapping of Solid Acid Catalyst in Fructose Conversion. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 9862–9878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, K.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Fu, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y.; Sun, H.; et al. Deep Bayesian Surrogate Models with Adaptive Online Sampling for Ensemble-Based Data Assimilation. J. Hydrol. 2025, 694, 132457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Hamon, F.P.; Wen, G.; Kanfar, R.; Araya-Polo, M.; Tchelepi, H.A. Learning CO2 Plume Migration in Faulted Reservoirs with Graph Neural Networks. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 193, 105711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhang, D.; Wang, N. Uncertainty Quantification and Inverse Modeling for Subsurface Flow in 3D Heterogeneous Formations Using a Theory-Guided Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Network. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.W.; Sun, W.Y.; Jeong, H.; Liu, J.R.; Zhou, W.X. Efficient Deep-Learning-Based Surrogate Model for Reservoir Production Optimization Using Transfer Learning and Multi-Fidelity Data. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 1736–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J. A Novel Hybrid Recurrent Convolutional Network for Surrogate Modeling of History Matching and Uncertainty Quantification. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 210, 110109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Fu, Q.; Li, H. A Novel Deep Learning-Based Automatic Search Workflow for CO2 Sequestration Surrogate Flow Models. Fuel 2023, 354, 129353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefzadeh, R.; Ahmadi, M. Well Trajectory Optimization under Geological Uncertainties Assisted by a New Deep Learning Technique. SPE J. 2024, 29, 4709–4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Shi, L.; Zhao, T.S. Accelerated Lattice Boltzmann Simulation Using GPU and OpenACC with Data Management. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 109, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Wu, X.; Si, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Duan, X. Seismic Foundation Model: A next Generation Deep-Learning Model in Geophysics. Geophysics 2025, 90, IM59–IM79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Yao, J.; Yokoya, N.; Li, H.; Ghamisi, P.; Jia, X.; et al. SpectralGPT: Spectral Remote Sensing Foundation Model. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 5227–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbagh, V.B.; Lima, C.B.C.; Xexeo, G. Comparative Analysis of Single and Multiagent Large Language Model Architectures for Domain-Specific Tasks in Well Construction. SPE J. 2024, 29, 6869–6882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, H.P.; Syamlal, M.; Crawford, S.E.; Lee, Y.L.; Shugayev, R.A.; Lu, P.; Ohodnicki, P.R.; Mollot, D.; Duan, Y. Quantum Computing and Simulations for Energy Applications: Review and Perspective. ACS Eng. Au 2022, 2, 151–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubomir, B. Quantum Algorithm for the Navier-Stokes Equations by Using the Streamfunction-Vorticity Formulation and the Lattice Boltzmann Method. Int. J. Quantum Inf. 2022, 20, 2150039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitan, F. Finding Solutions of the Navier-Stokes Equations through Quantum Computing-Recent Progress, a Generalization, and Next Steps Forward. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2021, 4, 2100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budinski, L. Quantum Algorithm for the Advection-Diffusion Equation Simulated with the Lattice Boltzmann Method. Quantum Inf. Process. 2021, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak, D.; Winter, J.; Schmidt, S.; Indinger, T.; Janssen, C.F.; Schramm, U.; Adams, N.A. A Quantum Algorithm for the Lattice-Boltzmann Method Advection-Diffusion Equation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2025, 306, 109373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X. Performance Study of Variational Quantum Linear Solver with an Improved Ansatz for Reservoir Flow Equations. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 047104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanaro, A.; Pallister, S. Quantum Algorithms and the Finite Element Method. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 93, 032324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moawad, Y.; Vanderbauwhede, W.; Steijl, R. Investigating Hardware Acceleration for Simulation of CFD Quantum Circuits. Front. Mech. Eng. 2022, 8, 925637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, T.; Budinski, L.; Niemimaeki, O.; Lahtinen, V.; Liebelt, H.; Li, R. Utilizing Classical Programming Principles in the Intel Quantum SDK: Implementation of Quantum Lattice Boltzmann Method. ACM Trans. Quantum Comput. 2025, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Ma, Z.; Zong, Z.; Shang, S. Review of fracture prediction driven by the seismic rock physics theory (II): Fracture prediction from five dimensional seismic data. Geophys. Prospect. Pet. 2022, 61, 373–391. [Google Scholar]

| Feature Dimension | Phase 1: Surrogate Model | Phase 2: Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) | Phase 3: Neural Operator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Idea | Train AI to learn the end-to-end mapping between the “input–output” of a complex physical system to replace high-cost physical modeling. | Embed the partial differential equations (PDEs) of the control system into the loss function of the neural network as a physical constraint. | Learn the solution operator for solving PDEs itself, that is, learn the mapping from function to function. |

| Learning Goal | A specific solution under specific parameters. (Mapping relationship: parameters → solution) | A specific solution under specific parameters. Solved through regularization with physical equations. | The operator of the problem itself. Mapping relationship: function (e.g., permeability field) → function (e.g., pressure field) |

| Main Advantages | Extremely high inference efficiency: Prediction speed can be thousands to millions of times faster than traditional numerical solutions, suitable for uncertainty quantification and solution optimization. | Reduced data dependency: The introduction of physical constraints improves the model’s generalization ability and reduces the reliance on massive labeled data. | “Train once, use multiple times”. Can achieve “zero-cost” instantaneous prediction for new parameters, with disruptive efficiency advantages in tasks such as uncertainty analysis. |

| Core Challenges | 1. Lack of physical consistency: Prediction results may violate physical laws. 2. Reliance on massive data: Model performance heavily depends on large-scale datasets that ensure the generation of true solution data. | 1. Training difficulty: The weights of the loss function are difficult to balance, and the optimization process is unstable. 2. “Rigid” solution: Once the parameters are changed, the network theoretically needs to be retrained, which is not suitable for optimization tasks that require repeated solving. | 1. Limited generalization ability: For new problems outside the training set (out-of-distribution), the accuracy may drop significantly. 2. High training cost: In the early stage, a large amount of high-precision numerical solution data is still required to train the operator. |

| Applicable scenarios | Scenarios that require a large number of repetitive and rapid predictions for a fixed physical model, such as preliminary sensitivity analysis, parameter optimization, etc. | Solving forward and inverse problems where data is sparse but the physical equations are known. For example, inferring the complete flow field from sparse observation points. | Scenarios that require exploring system responses under a large number of different parameters (e.g., different permeability fields), such as oil reservoir development plan optimization, real-time decision support, etc. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liang, J.; He, L.; Chai, W.; Jia, N.; Liu, R. A New Paradigm for Physics-Informed AI-Driven Reservoir Research: From Multiscale Characterization to Intelligent Seepage Simulation. Energies 2026, 19, 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010270

Liang J, He L, Chai W, Jia N, Liu R. A New Paradigm for Physics-Informed AI-Driven Reservoir Research: From Multiscale Characterization to Intelligent Seepage Simulation. Energies. 2026; 19(1):270. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010270

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Jianxun, Lipeng He, Weichao Chai, Ninghong Jia, and Ruixiao Liu. 2026. "A New Paradigm for Physics-Informed AI-Driven Reservoir Research: From Multiscale Characterization to Intelligent Seepage Simulation" Energies 19, no. 1: 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010270

APA StyleLiang, J., He, L., Chai, W., Jia, N., & Liu, R. (2026). A New Paradigm for Physics-Informed AI-Driven Reservoir Research: From Multiscale Characterization to Intelligent Seepage Simulation. Energies, 19(1), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010270