1. Introduction

The relationship between energy efficiency and energy poverty is complex and multidimensional, involving economic, social and environmental factors. Improving energy efficiency is widely recognised as an effective solution to reducing expenditure on energy needed to meet basic needs and alleviating energy poverty [

1,

2,

3]. It is pointed out that through better insulation of homes, efficient appliances and optimised heating systems, energy consumption can be reduced and energy bills made more affordable for households, especially those on low incomes [

4,

5,

6]. These elements are also highlighted in the EU’s Energy Efficiency Directive, which explicitly links energy poverty to poor energy efficiency and urges Member States to consider energy poverty when designing policy instruments to meet national energy saving obligations [

1,

7].

Renovating buildings to improve energy efficiency, especially in social and affordable housing, is a key strategy promoted by the European Commission, although, as practice shows, funding for such initiatives is often limited and short-term [

2,

7]. However, the literature points to many barriers to improving energy efficiency in order to reduce energy poverty. These include, among others, initial investment costs [

3], limited access to capital and efficient technologies [

8], and financial inclusion [

9].

Countries with a long tradition of addressing energy poverty, such as France and the UK, have more integrated policies that connect social and energy policy through energy efficiency measures [

4]. However, not everywhere has a tradition of implementing policies directly aimed at reducing energy poverty [

10,

11], and energy consumption preferences among end-users can vary greatly [

12], which hinders the effectiveness of any measures to reduce energy poverty.

The literature recognises technological changes, rather than structural changes, as the main factor influencing the reduction in energy intensity in the economy (and thus the increase in energy efficiency) [

13], which may indicate the key role of industrial sectors here. The question is whether the increase in energy efficiency in industry and the decrease in energy intensity in the industrial economy lead to a reduction in energy poverty in EU Member States.

The literature to date is poor in examining this relationship, which constitutes a research gap. Most often, energy efficiency in industry is seen as a promising way to solve problems related to climate change [

14,

15]. In addition, it is pointed out that energy intensity in industry can increase productivity and support economic growth in the long term [

13], which can already be linked to the impact on energy poverty, or that low-carbon energy transition mitigates energy poverty [

16]. Thus, in the literature, there are links between energy efficiency (or energy intensity) and energy poverty, but there is a lack of direct analysis of the relationship between the two phenomena, especially with regard to changes in industry, which the authors attempt to explore.

Industrial energy intensity is theoretically justified as a key determinant of energy poverty because it represents a systemic measure of how efficiently energy is transformed into economic value within the production structure of an economy, with implications that extend beyond the industrial sector itself. From the perspective of the energy–economy nexus, reductions in industrial energy intensity reflect technological upgrading, process optimisation, and improved resource allocation, all of which lower aggregate energy demand per unit of output and reduce cost pressures across the entire energy system. In economies where industry constitutes a substantial share of final energy consumption, efficiency gains at this level contribute to greater stability of energy supply, reduced exposure to price volatility, and lower marginal costs of energy generation and distribution, thereby indirectly improving affordability for households. Moreover, industrial energy intensity is closely linked to labour productivity and capital modernisation, which influence income generation, employment stability, and fiscal capacity for social and energy policies.

Unlike household-level efficiency indicators, industrial energy intensity captures these macro-structural dynamics and long-run adjustment processes, making it a theoretically appropriate variable for analysing energy poverty as a socio-economic outcome embedded in broader production, pricing, and institutional systems rather than solely in household consumption behaviour.

The aim of this study is to assess, using panel data models, the impact of improved energy efficiency (decreased energy intensity) in industry on the level of energy poverty in European Union countries, taking into account the macroeconomic environment (income, social, energy and labour market) in EU economies. Since EU economies are diverse and develop at different rates, as does production efficiency, and since the literature indicates that higher labour productivity is associated with improved energy efficiency and lower CO

2 emissions, especially in industry [

17,

18,

19], and there are dynamic interactions between investment expenditure and deployed renewable capacity [

20], this paper additionally assumes the potential endogeneity of energy intensity in industry relative to labour productivity.

The following research questions were formulated:

RQ1: Does a reduction in industrial energy intensity lead to a statistically significant decrease in household energy poverty across European Union Member States?

RQ2: To what extent does the strength of the relationship between industrial energy efficiency and energy poverty differ across EU countries?

RQ3: Are countries characterised by lower industrial energy intensity systematically associated with lower average levels of energy poverty?

RQ4: Does industrial energy efficiency (EE) reduce energy poverty (EP) indirectly through the stabilisation of electricity prices for household consumers?

RQ5: Do macroeconomic and social conditions—specifically income levels, social expenditure, and labour costs—moderate the impact of industrial energy efficiency on energy poverty?

RQ6: Does higher labour productivity in industry indirectly reduce energy poverty by improving industrial energy efficiency?

The following research hypotheses (Hs) were adopted in the paper:

H1: Reducing the energy intensity of industry in European Union countries leads to a statistically significant reduction in energy poverty.

H2: The impact of improved energy efficiency in industry on household energy poverty varies between EU countries and depends on their macroeconomic and social conditions (GDP per capita, labour productivity, expenditure on social benefits, and labour cost in industry).

H3: Countries with lower energy intensity in the industrial sector show a lower average level of energy poverty.

H4: Improvements in energy efficiency in industry, measured by a decrease in energy intensity in industry, indirectly reduce energy poverty by stabilising electricity prices.

H5: The scale of the impact of energy intensity in industry on energy poverty is modified by income levels, social support levels and wages in the labour market.

H6: Higher real labour productivity in industry indirectly reduces energy poverty by improving energy efficiency in industry (decrease in energy intensity in industry).

The contribution of this paper is threefold. First, an analysis of the impact of energy efficiency on energy poverty in EU countries will be conducted. As indicated in the research gap, the existing literature is scarce in examining this relationship, and there is a lack of direct analyses of the link between the two phenomena. It has most often been analysed in the context of the link between energy efficiency in industry and decarbonisation processes [

14,

15]. However, the link with energy poverty has only been made indirectly, by pointing to the role of economic development [

13]. Secondly, analyses of the direct links between energy efficiency and energy poverty have only been carried out for selected countries or Asian countries [

16]. Thirdly, the panel models used here will allow us to capture the relationships for the EU as a whole and the differences between Member States. This will be achieved by analysing the impact of the decline in energy intensity in industry, and thus the improvement in energy efficiency, on the level of energy poverty in European Union countries, taking into account the macroeconomic environment (income, social, energy and labour costs) in EU economies. In addition, the potential endogeneity of energy efficiency in industry with respect to labour productivity is assumed.

The structure of the paper is as follows. After the introduction, the authors will present the theoretical background of the analysed relationships, followed by the research methodology, i.e., the conceptual model and the research methods used. The authors will then present the research results, followed by a discussion of the results and conclusions from the paper, enriched by recommendations.

3. Materials and Methods

The aim of this study is to assess the impact of energy efficiency in industry on the level of energy poverty in European Union countries, taking into account the macroeconomic environment in EU economies. To achieve this objective, the analysis will be carried out using panel data models, controlling for key economic and social conditions (real GDP per capita, expenditure on social benefits, electricity prices, labour costs) and taking into account potential endogeneity using an instrumental variable, i.e., the impact of labour productivity in industry on energy efficiency in industry. The inclusion of such control variables stems from the fact that, as the literature indicates, energy efficiency can mitigate energy poverty by reducing energy demand and expenses, making energy more affordable for vulnerable populations [

3,

5,

6,

70]. As the literature indicates, energy poverty is influenced by a mix of low household income, poor household energy efficiency, and high energy prices [

71]. Furthermore, improving energy efficiency can reduce energy prices, which may translate into energy poverty [

72], and energy poverty itself is largely due to climate and energy policies that affect energy prices [

73]. This justifies the inclusion of GDP per capita and electricity prices for end-users. In addition, energy poverty is sensitive to the social policy of the state and mainly affects the poorest, hence the model also includes labour costs and expenditure on social benefits [

50]. The endogenous variable is justified by the fact that the vast majority of the literature indicates that in industry in most countries, higher labour productivity is associated with improved energy efficiency [

19,

74,

75,

76]. Only a few studies suggest that labour productivity does not always ensure improving energy efficiency or may have a limited [

77,

78], or even negative effect on energy efficiency [

74].

The paper analyses the impact of energy efficiency on energy poverty. Therefore, the following variables are adopted in the model:

Y—energy poverty of households, measured by the indicator of inability to keep home adequately warm (% of total households)

X1—energy intensity of industry as a measure of energy efficiency (EEff = 1/X1),

X2—real GDP per capita (2015 = constant; in EUR/Ma),

X3—expenditure on social benefits (as % of GDP);

X4—electricity prices for household consumers (EUR/kWh);

X5—nominal unit labour cost based on hours worked by industry (2015 = 100);

X6—real labour productivity per person in industry (2015 = 100)—endogenous variable affecting X1.

The source of data for all variables is Eurostat, which ensures methodological comparability of data. Sources for particular parameters:

Sources for X1—Eurostat, Simplified energy balances,

https://doi.org/10.2908/NRG_BAL_S (11 November 2025); [

80], Eurostat, Gross value added and income by detailed industry (NACE Rev.2) (11 November 2025) [

81].

The analytical framework on which the research is based presumes that energy poverty is a macro-social phenomenon that depends on structural attributes of the production system and broader economic factors. A core variable within the framework is industrial energy intensity (X1), which belongs to a proxy variable for industry energy efficiency and represents the main transmission mechanism that might affect energy deprivation within households as a consequence of production-side technological changes (H1). The analytical framework presumes that as a result of lowering industrial energy intensity, there would be an improvement in process efficiency and industry organisational improvements that affect energy demands positively and reduce cost pressures associated with energy production. Accordingly, it lays a foundation for testing the impact associated with energy poverty and reduced energy intensity within specific Member States within the European Union.

As foreseen by hypotheses H2 and H3, it is specified within the model that there may be country-specific heterogeneity, taking into account fixed effects that embody national traits. Examples of these traits include housing stock quality, weather, institutional settings, and energy market organisation. Unobserved variables should thus affect energy poverty on a conditional level as well as interactions with industrial energy efficiency. Moreover, aiming at hypothesis H6 and correcting for endogeneity because of energy intensity within industry, a covariate included as an instrument within the model as per hypothesis H6 would be labour productivity within industry, represented as variable X6. Productivity per se would be a measure reflecting technological advancements as well as capital. It would thus be assumed within theoretical stands that it would act as an assist mechanism that would reduce energy usage per value added without any influence on energy poverty. At last, as suggested by hypotheses H4 and H5, the model accounts for the set of macro variables that comprise real GDP per capita (X2), expenditure on social benefits (X3), and prices for residential electricity consumption (X4), as well as unit labour costs within industry (X5). It should be noted that these variables correspond to alternative explanatory factors, taking into account income capabilities, redistribution factors, price sensitivities, and production costs. By incorporating these elements into a comprehensive framework, it becomes possible for this model to offer a structured empirical representation equivalent to those outlined within the Introduction.

Table 2 provides a structured overview of all variables employed in the empirical analysis and clarifies their role within the research framework. It distinguishes the dependent variable capturing household energy poverty from the key explanatory variable representing industrial energy efficiency, as well as from macroeconomic and social control variables that account for income capacity, redistribution mechanisms, price exposure, and cost conditions. In addition, the table explicitly identifies real labour productivity in industry as an instrumental variable, highlighting its function in addressing the potential endogeneity of industrial energy intensity. By specifying the definition, unit of measurement, analytical objective, data source, and variable type for each indicator, the table enhances methodological transparency and ensures that the selection and interpretation of variables are theoretically grounded and empirically traceable.

The conceptual model used in the study is that labour productivity in industry (X6), i.e., technological innovations, better production organisation and modernisation of machinery, contribute to a decrease in energy intensity in industry (X1), i.e., lower energy consumption per unit of value added in industry, and thus to an improvement in energy efficiency in industry (1/X1). In this way, X6 indirectly affects Y through X1. On the other hand, a decrease in energy intensity in industry, i.e., an improvement in the energy efficiency of industrial production, means lower energy costs across the economy, less pressure on energy prices, higher competitiveness and higher incomes, which determines the level of energy poverty in households (Y). The logic of the model is that energy poverty is a function of both macroeconomic factors (represented by variables X2-X5) and energy intensity parameters on the industrial side. Among the control variables, macroeconomic factors are expected to increase the ability of households to finance energy expenditure and encourage investment in energy efficiency (buildings, appliances, etc.) and a decrease in the level of energy poverty (Y). Higher social expenditure (X3) is expected to mean stronger redistribution and social protection mechanisms, which may compensate for high energy costs for the most vulnerable households and a decrease in Y. Electricity prices for household consumers (X4), meanwhile, are a direct determinant of energy costs in household budgets. Therefore, higher X4 is expected to contribute to higher Y. The last variable is nominal unit labour cost in industry (X5), where higher unit labour costs in industry are expected to drive up production costs, contribute to higher prices of goods and indirectly to the cost of living, including energy, and ultimately have a positive impact on Y.

Taking all these assumptions into account, we used two models for analysis in our work: (1) the Fixed Effects (FE) model controlling for country and year effects, and (2) the Instrumental Variables (IV) approach using Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) to address potential endogeneity of labour productivity in industry. The FE model was chosen to control for country and year heterogeneity, and this was performed on the basis of the Hausman test [

87,

88,

89]. The IV model, on the other hand, is an econometric technique designed to address endogeneity issues in regression analysis [

90,

91]. The estimation of this model was performed using the two-stage least squares (2SLS) method [

92,

93,

94]. To ensure methodological correctness, robustness checks were additionally performed, which included heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation tests, followed by HAC correction. This approach is consistent with the assumptions of fixed effects regression and increases the robustness of statistical inference [

6,

95,

96].

Description of parameters in the IV (2SLS) model

Y—household energy poverty indicator; dependent variable measuring the share of households unable to keep their dwelling adequately warm.

X1—industrial energy intensity; endogenous explanatory variable representing energy efficiency in industry.

X1^ (predicted X1)—fitted value of industrial energy intensity obtained from the first-stage regression; captures exogenous variation in X1 driven by labour productivity.

X6—real labour productivity in industry; instrumental variable reflecting technological progress and production efficiency, assumed to affect energy poverty only indirectly through X1.

X2—real GDP per capita; control variable capturing overall income level and economic development.

X3—expenditure on social benefits; control variable representing redistributive and social protection mechanisms.

X4—electricity prices for household consumers; control variable testing the price-related transmission channel affecting energy affordability.

X5—nominal unit labour costs in industry; control variable capturing production cost conditions and structural economic characteristics.

μᵢ (country fixed effects)—unobserved, time-invariant national characteristics such as housing stock quality, climate, institutional framework, and industrial structure.

γₜ (time fixed effects)—common temporal shocks affecting all countries, including energy crises, macroeconomic disturbances, and policy changes.

εᵢₜ (error term)—idiosyncratic, time-varying disturbances not explained by the model.

The Fixed Effects (FE) model was chosen to account for unobserved, time-invariant characteristics of countries that could bias the estimates if ignored. By including country and year dummies, the FE model controls for these constant factors; it ‘removes’ the influence of these constant characteristics in order to focus on variability over time, thus isolating the effect of X1 on Y within each country over time. This approach is appropriate when the primary concern is heterogeneity across entities that does not change over time. This prevents the erroneous attribution of the impact of variables when differences between countries are significant but not measured in the data. In contrast, the Instrumental Variables (IV) model is a method used when we suspect endogeneity, i.e., a situation where the explanatory variable is correlated with the model error, which could lead to erroneous conclusions. To address this, we use labour productivity as an instrument for energy efficiency in industry. The instrument satisfies two key conditions: firstly, relevance, i.e., in our model, labour productivity in industry is strongly correlated with energy efficiency in industry, and second, exogeneity, namely, labour productivity does not directly affect the dependent variable (energy poverty level), but allows us to obtain the ‘purified’ effect of X1 on Y, free from the problem of endogeneity.

This paper analyses the impact of energy efficiency in industrial processes on energy poverty levels using a panel data set covering all 27 European Union countries over the years 2003–2023. The research period is limited by the availability of statistical data but covers the entire period of the new Member States’ presence in the EU structures. Each observation represents a country-year pair, including the dependent variable (Y), the main explanatory variable (X1), macroeconomic controls (X2–X5), and an instrumental variable (X6). Panel data allows us to capture both cross-sectional and time-series variation, which is essential for understanding dynamic relationships and controlling for unobserved heterogeneity.

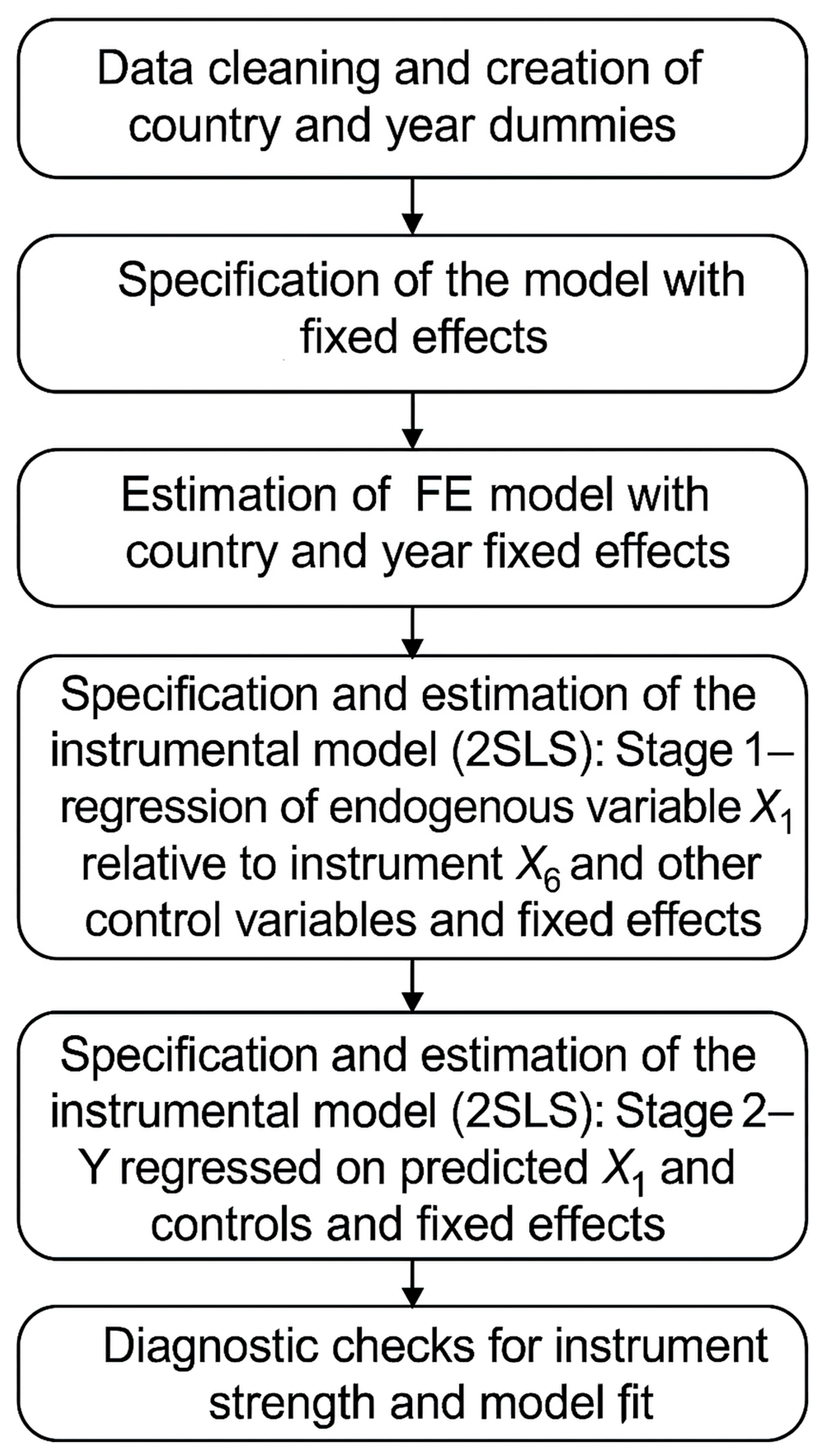

The Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) method is applied: Stage 1 predicts X1 using X6 and controls; Stage 2 regresses Y on the predicted X1 and controls. This approach provides consistent estimates of the causal effect of X1 on Y.

Thus, six stages of the research model used can be distinguished in the study (see

Figure 1).

According to this research procedure, the basic fixed effects (FE) panel model for the country and year will be estimated according to the following equation (second stage—Y regressed):

where

i—country, i = 1, …, 27;

t—year;

μi—fixed effects, unobservable country-specific effects (country fixed effects);

γt—time dummy (dummy for the year), controls for time dummies common to all countries, which allows for the elimination of unobservable structural differences and common shocks (e.g., COVID-19, the 2022 energy crisis, the 2008–2009 financial crisis);

εit—random component;

Yit—dependent variable,

X1it, …, X5it—independent variables, where X1it is the main independent variable, and X2it-X5it are macroeconomic control variables.

The selection of the FE model will be verified using Hausman’s test comparing fixed (FE) and random effects (RE) estimators. Student’s t-statistics will be used to assess the significance of the parameters.

The Instrumental Variables model (IV model), on the other hand, will be modelled according to the equation (first stage—regression of endogenous variable):

The relevance of instrument X6 for energy intensity (X1) will be assessed on the basis of the instrument relevance test (F-statistic) and the coefficients of determination R-squared and adjusted R-squared for model fit evaluation. The Breusch-Pagan test will be used, robust standard errors (HC3) will be applied to account for heteroscedasticity, and autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity will be jointly corrected using the Newey-West HAC correction, which will allow for a comparison of the results obtained with different covariance matrix specifications.

Significance tests for coefficients (p-values) will also be calculated to confirm the statistical relevance of X1 and controls. FE estimation is performed using the least squares method with the use of the robust HC3 covariance matrix and the Newey-West HAC correction (HAC).

4. Results

4.1. Correlation Analysis

First, Hausman’s statistic was calculated (for variables X1–X6): χ

2 = 28.077, df = 6,

p = 0.0000878. These results indicate that the use of a random effects (RE) model should be rejected and confirm that a fixed effects (FE) model is the correct choice, as the unobservable fixed characteristics of countries are correlated with the regressors (

Table 3).

Next, in order to identify the interdependencies, strength and direction of linear relationships between variables, including between energy intensity in industry sectors and real labour productivity in industry, the correlation matrix was used.

The correlation analysis indicates that higher energy intensity is strongly positively correlated with energy poverty (r = 0.54), and corr(X1, X6) = −0.393, which indicates a correlation between these variables, i.e., higher real labour productivity in industry leads to lower energy intensity of industry. In addition, the possibility of multicollinearity between independent variables was found.

4.2. Diagnostic Model

In the next stage, the authors proceeded to diagnose and evaluate the FE model. As part of this stage, the existence of heteroscedasticity, autocorrelation and collinearity was checked. The results of these tests are shown in

Table 4.

The results suggest the presence of strong heteroscedasticity, indicating the need to apply HAC correction, which indicates that cluster-robust standard errors are necessary or heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation consistent (HAC), which was performed in the model. Additionally, it was found that there is no strong autocorrelation. The above results indicated the validity of using the FE-IV (2SLS) model with HAC correction.

Next, the FE–IV model was diagnosed, and first-stage diagnostics (IV model) tests were calculated to assess whether instrument X6 is relevant and predicts X1 well. The results of these calculations are shown in

Table 5.

The results show that variable X6 is a very powerful and relevant instrument. Therefore, the FE–IV model diagnostics (second stage), i.e., heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation, were performed (

Table 6 and

Table 7).

These results indicate that there is a positive correlation between energy intensity in industry (X1) and energy poverty (Y). It can therefore be concluded that a decrease in energy intensity in industry has a statistically very significant impact on reducing the level of energy poverty among households and that this impact is very strong. It was also found that the effect, after controlling for endogeneity, is even stronger and still significant.

Answering the first hypothesis (H1), it was found that a reduction in the energy intensity of industry (X1) leads to a statistically significant reduction in the level of energy poverty (Y). In the FE model, the X1 coefficient is positive and highly significant (33.6; p < 0.001). In contrast, in the FE–IV model, the coefficient for the X1_impl. variable is even higher and indicates a statistically significant strong positive effect after endogeneity correction (73.1; p ≈ 0.00005). Thus, H1 is strongly confirmed positively (both in the FE model and after endogeneity correction in the FE–IV model), which means that a decrease in the energy intensity of industry significantly reduces energy poverty in the EU.

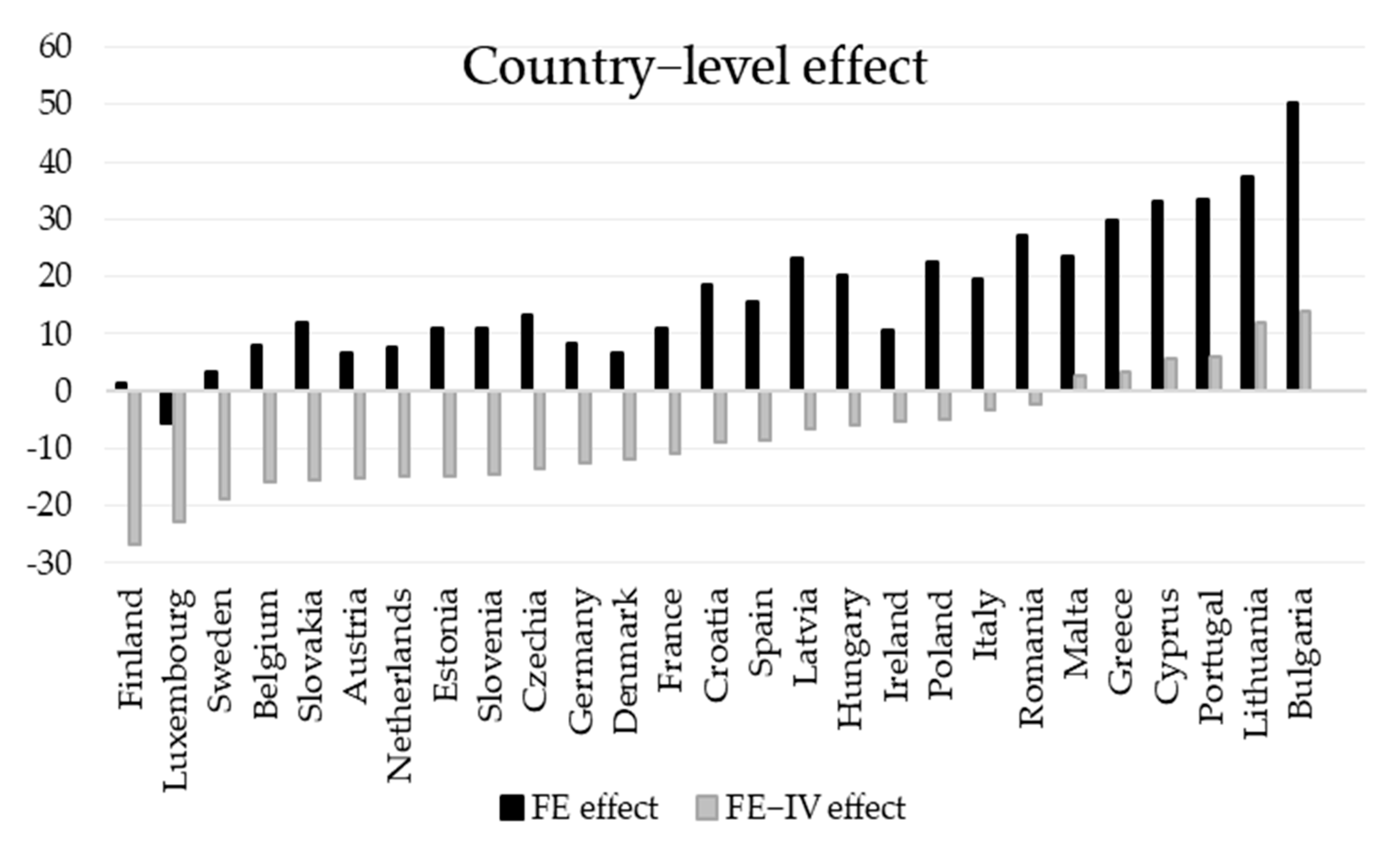

Next, we checked whether the fixed effects across EU countries are homogeneous or heterogeneous. The results of the country-level effects before and after endogeneity correction are shown in

Figure 2.

The results indicate strongly differentiated country fixed effects (FE model) and even stronger differentiation after correction for endogeneity X1 (FE-IV model). The results showed that the minimum FEs are for Luxembourg (−5.64) and the maximum for Bulgaria (50.64), which means that the spread between countries is as high as 55.98 points. After endogeneity correction (FE-IV effects), these spreads still exist, with the minimum value for Finland (−26.63) and the maximum for Bulgaria (13.79), which means a spread of 40.42 points. This indicates that EU countries differ structurally in terms of energy poverty levels and have persistent determinants that are not observed in the model. The reasons for these differences may lie in differences in housing policies, varying building infrastructure efficiency, climatic differences or different electricity prices. After X1 instrumentation, national effects shift by as much as several to several dozen points, which means that in different countries the impact of the decline in energy intensity in industry on the decline in energy poverty varies in strength. This confirms that there is causal heterogeneity, which is direct empirical evidence to support hypothesis H2.

4.3. Correlation Analysis

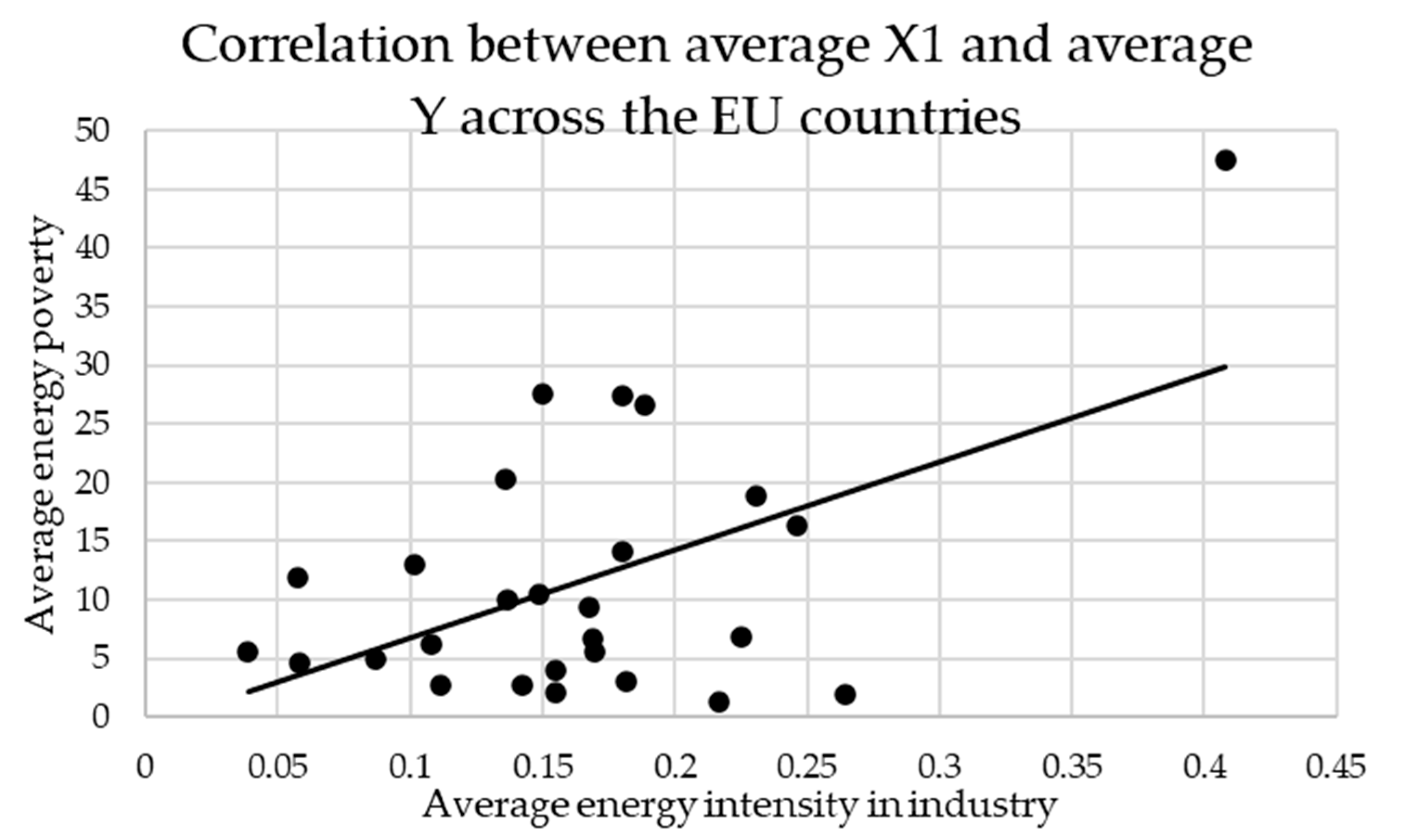

The differences between countries are also confirmed by the varying correlation between energy intensity (X1) and energy poverty (Y) among EU countries (see

Figure 3).

As the analysis data show (

Figure 3), the correlation for the EU as a whole is positive and strong, indicating that the higher the energy intensity of industry, the greater the risk of energy poverty in society. However, across countries, this correlation varies greatly.

These results also reinforce the conclusions on the significance of hypotheses H3 and H4. In the context of H3, this confirms that countries with lower energy intensity of industry show lower levels of energy poverty. The correlation between the mean X1 and the mean Y across countries is strong, at 0.52. The value of p = 0.0054 (<0.01) indicates high statistical significance.

In the next step, verifying hypothesis H4, it was checked whether the decrease in energy intensity in industry (X1) reduces energy poverty (Y) indirectly through the stabilisation of electricity prices (X4). For this purpose, an indirect effect analysis (X1 → X4 → Y) was verified, i.e., four regression equations:

- -

second model, where

- -

third model for fixed effects:

- -

and, fourth model for FE-IV/2SLS:

The results of this analysis are presented in

Table 8.

Analysis of the first model indicates that the variable describing the energy intensity of industry (X1) does not have a statistically significant impact on electricity prices (X4). This means that in the panel data set under study, fluctuations in energy intensity do not translate into noticeable price dynamics for households. In the second model, a positive but still insignificant relationship was observed between X4 and the scale of energy poverty (Y), suggesting that energy prices, although theoretically capable of affecting the level of energy deprivation, are not in themselves a sufficient predictor of its intensity in panel terms.

Estimates within the fixed effects model (Model 3) confirm a clear and statistically significant strong relationship between X1 and Y, emphasising the dominance of the direct channel. At the same time, the lack of significance of the coefficient at X4 suggests that the indirect mechanism based on the impact of energy prices does not play a relevant role in this context. After applying a two-stage estimation (Model FE-IV), which corrects the endogeneity of X1 using an instrument based on labour productivity (X6), the strength of the impact of X1 on Y is further reinforced. However, in this case, the impact of X4 on energy poverty is statistically significant. After adjusting for the endogeneity of X1 (instrument X6) and controlling for X2–X5 and country fixed effects, X4 has a positive, marginally significant relationship with Y. However, it was found that X1 does not affect X4. Thus, hypothesis 4 cannot be confirmed. As a result, it can be concluded that the indirect mechanism assumed in hypothesis H4, although theoretically justified and consistent with economic intuition, is not clearly confirmed empirically in the analysed panel data for EU countries.

The hypothesis that energy prices might serve as a mediating variable on the relationship between industrial energy intensity and energy poverty was based on traditional energy-economic theory, implying that enhancements in energy efficiency upstream would result in a decrease in aggregate energy consumption and correspondingly lead to declines in wholesale and retail energy prices due to market forces. According to traditional energy-economic reasoning, it is assumed that enhancements in energy efficiency within energy-intensive industrial segments would help reduce stress on generation capacities and energy sources as well as on consumptions via networks. As a result, it would reduce stress on energy prices, impacting end-use sectors, including households. The highly regulated structure of electricity markets within the European Union and the various associated cost components and considerations make it somewhat difficult for any enhancements due to industrial energy efficiency gains to be transmitted directly within wholesale and retail energy sector price signals. The empirical findings contained within the current study, therefore, do not refute but instead highlight institutional factors leading to industrial efficiency gains and the subsequent impact on retail factors within the current EU institutional framework, effectively saying that institutional factors have led to a decoupling effect on retail energy prices.

To verify hypothesis H5, we examined whether the strength of the impact of industry energy intensity (X1) on energy poverty (Y) may vary depending on selected macroeconomic characteristics of countries, such as GDP per capita (X2), expenditure on social benefits (X3) or labour costs in the industrial sector (X5). In order to assess the validity of this assumption, the moderation tests were conducted for potential differentiating variables, namely X2, X3 and X5. For this purpose, for each moderating variable Z (Z∈{X2,X3,X5}), the following was estimated:

First, three separate moderation tests were performed in the FE model (which acts as a diagnostic model) to check whether the moderation mechanism exists at all. The results of the analysis are shown in

Table 9.

The results of the estimates indicate that only variable X3 (expenditure on social benefits) shows a statistically significant moderating effect in the relationship X1 → Y, i.e., the impact of energy intensity of industry on the level of energy poverty. Analogous interactions with variables X2 and X5 are not statistically significant and therefore do not meet the empirical criterion for moderation of this effect. Since this moderating effect was only found for variable X3, in the next stage the moderating effect for the FE-IV model was calculated only for this variable. Thus, the endogenous variables are X1 and X1 × X3, and the instruments are X6 and X6 × X3. The results of the moderation analysis with instrumentation X1 and X1 × X3 are shown in

Table 10.

The results of the analysis indicated that the value of coefficient X1, and thus its impact on energy poverty, remains statistically significant even after adding X2 as a key variable (although the significance would decrease—the standard error would increase). GDP per capita, despite being included in the model as a key variable, does not provide structural information and remains statistically insignificant as a determinant of energy poverty. Thus, the impact of GDP per capita (X2) is statistically insignificant, and this variable does not play an independent role in determining energy poverty (Y). The same applies to variable X3. Taking into account all the results, it should be concluded that hypothesis H5 is negatively verified. The results show that in the FE-IV model, the impact of energy intensity (X1) on energy poverty (Y) is stronger (which we already know from previous analyses), which is consistent with the endogeneity correction of X1. It was also found that the moderating effect of expenditure on social benefits (X3) is marginal (p = 0.0596), but weakens after instrumentation (in the FE model p = 0.0397). At the same time, the Fe model confirmed that variables X2 and X5 do not moderate the impact of X1 on Y (the p-value is high, which means that both variables are consistently statistically insignificant). The conclusion from hypothesis H4 that variable X4 affects Y (but independently of X1) was also confirmed. Therefore, the final conclusion is that only variable X3 shows an empirically justified role as a moderator of the X1–Y relationship, although this effect decreases after correcting for the endogeneity of X1 in the FE-IV model. Hypothesis H5 is therefore only partially confirmed, as variables X2 and X5 do not show moderating effects of energy intensity on energy poverty.

Hypothesis H6 assumed that an increase in real labour productivity in the industrial sector (X6) may indirectly reduce energy poverty (Y), primarily by reducing the energy intensity of industry (X1). To verify this mechanism, the relationships between X6 and X1 were analysed in the first stage of instrumental estimation, and in the second stage, in which X1 was replaced by forecast values (X1_hat), the results of which are presented in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7.

Table 11 presents the summary results for hypothesis H6.

In the first stage of model IV, in which the energy intensity of industry was explained by a set of economic variables and fixed effects for countries, labour productivity in industry (X6) shows a clearly negative and statistically strong relationship with energy intensity. This result means that economies with higher labour productivity are typically characterised by lower energy consumption per unit of value produced, which is confirmed both by energy economics theories and by many sectoral analyses.

In the second stage of estimation, which examined the impact of energy intensity adjusted for endogeneity on energy poverty, a positive and highly significant coefficient was obtained. This result suggests that the indirect channel of X6’s impact on Y through a decrease in X1 is not only consistent with theoretical intuition but also clearly present in the data. Thus, an increase in productivity translates into a reduction in energy intensity, which in turn correlates with a decrease in energy poverty. This hypothesis has therefore been positively confirmed.

5. Discussion

The empirical results obtained in this study provide strong support for theoretical frameworks describing the relationship between technological efficiency, macroeconomic structure, and household energy deprivation. The robust negative association between industrial energy intensity and energy poverty is consistent with the foundational logic of the energy–economy nexus theory, which posits that improvements in system-wide energy efficiency reduce per-unit energy demand and thereby stabilise aggregate energy expenditures. In classical formulations of this framework, lower primary energy requirements translate into reduced cost pressures for downstream consumers, especially in economies where industrial sectors remain central to national energy balances. The FE and FE-IV estimates indicate that these theoretical expectations hold systematically across European Union Member States and that the mechanism is not merely correlational but reflects a causally meaningful relationship rooted in production-side technological change [

97].

The results further align with the theory of endogenous growth, which emphasises the role of productivity and innovation in shaping long-term economic outcomes. In the present analysis, labour productivity in industry functions as an exogenous driver of improved energy efficiency [

98,

99,

100,

101,

102]. The confirmed X6 → X1 → Y pathway demonstrates that productivity-induced efficiency gains diffuse beyond the industrial sector and help reduce the vulnerability of households to energy deprivation. This is consistent with the argument that technological upgrading within firms produces spillover effects in the broader economy by promoting resource optimisation and reducing structural inefficiencies. The strong significance of the instrumental variable reinforces the proposition, found in earlier theoretical work, that efficient production systems integrate labour-capital complementarities conducive to lower energy intensity.

At the same time, the heterogeneity observed in fixed effects supports socio-technical transition theories, particularly the multilevel perspective. This framework argues that energy systems evolve through interactions between technological regimes, institutional structures and consumer practices [

103,

104,

105,

106]. The wide divergence in baseline energy poverty levels across countries, despite similar directional effects of efficiency gains, confirms that structural features of national housing stock, climatic conditions, welfare institutions or market regulation shape the local manifestation of energy vulnerability. In this context, the study’s finding that macroeconomic variables (income, social benefits and labour costs) do not significantly moderate the primary mechanism suggests that energy poverty is embedded in long-term structural determinants rather than short-term economic fluctuations. This is consistent with theories emphasising path dependency in energy and housing systems.

The absence of a statistically significant indirect effect through electricity prices appears to contradict classical energy price transmission models, which assume that efficiency gains reduce market prices for end-users [

107,

108,

109,

110]. However, this divergence can be explained by institutional price-setting mechanisms, regulated tariffs and the high share of non-energy components in retail electricity bills (taxes and network charges). The results therefore support theoretical approaches that treat energy poverty as a multidimensional socio-economic condition influenced not only by market forces but also by institutional and regulatory constraints. In line with energy justice theory, the study underscores that improving efficiency alone cannot guarantee affordability unless supported by equitable pricing structures and redistributive mechanisms.

Statistically insignificant, the coefficient associated with the labour costs in industry, X5, in

Table 9. It suggests that higher unit labour costs do not go along with high levels of energy poverty. This effect is likely to reflect a structural correlation in which higher labour costs are characteristic of more advanced, high-productivity economies with better technological standards, stronger labour-market institutions, and higher average household incomes. In such contexts, high labour costs tend to go hand in hand with lower industrial energy intensity, greater stability in employment, and fiscal capacity for social and energy-related policies, all factors contributing indirectly to energy poverty being low.

More importantly, this X5 significance does not imply that there is any moderating influence of the correlates on the relationship between industrial energy intensity and energy poverty. This is supported by (a) the fact that its interaction effects are not significant and (b) the stability of the X1 coefficient across specifications, documenting that labour costs do not change the magnitude of the energy-intensity channel but capture broader structural features absorbed by country fixed effects. Therefore, X5 shall be understood as a contextual control reflecting the level of economic development and production structure, rather than an independent policy handle to reduce energy poverty. By clarifying this, the statistical significance of X5 is made consistent with the theoretical framework of this study, eliminating ambiguity in its interpretation.

It was also found that GDP per capita (X2) does not moderate the impact of energy intensity (X1) on energy poverty (Y), but such a moderating effect occurs in the case of social benefits expenditure (X3). The economic rationale for X3 moderating the impact of X1 on Y is that social benefits increase disposable income and thus reduce extreme poverty, as confirmed by the literature [

50,

73]. However, social benefits can simultaneously sustain high levels of energy consumption in households (no pressure to reduce energy consumption) and thus maintain energy demand across the economy during periods of price increases. If X1 increases, i.e., industry consumes more energy per unit of production, cost pressure in the energy sector increases, and with it prices, including energy prices. Households in high-transfer systems maintain their energy consumption for longer, which makes them more exposed to cost increases, which in the long term causes energy poverty to increase across the economy as a whole. This is a classic mechanism from economic theory, whereby transfers stabilise consumption but increase exposure to energy price increases.

The results above can be related to both behavioural and socio-cognitive models of understanding consumption patterns with respect to energy in households [

111,

112,

113,

114]. It has been found that awareness about energy, value for the environment, and energy consumer segments can significantly impact the perception of energy-related forces by households. Thus, the structural parameter estimated in the panel models may be reinforced or moderated by behaviour-driven heterogeneity among the Member States, in line with theoretical frameworks establishing an interplay between economic drivers of energy poverty and household-level awareness and adaptation capabilities. This research can be helpful in creating structures for collaborative cooperation between governments and local institutions during energy transformation. Collaborative models of energy transformation are today the basis for a smooth transition from black energy to green energy at individual levels of society, provided they take into account integrated tools to mitigate the problems of the ongoing transformation [

115].

The results imply that an active industrial policy addressing energy poverty needs to focus on structural changes regarding industrial energy efficiency, with a focus on technological progress in energy-intensive industries, instead of solely addressing price. From a policy perspective, there would be a focus on promoting technological advances and digital transformation in energy-intensive industries and on spreading energy-efficient technologies. Policies would include actions like investment tax credits for energy-saving capital, privileged loans for energy renovation and energy-intensive industries, as well as conditional state aid targeted at energy intensities. Importantly, it will be seen that these measures should be formulated on a structural and longitudinal timetable because these impacts on energy poverty are driven more by productivity and cost stabilisation effects than price.

The large degree of heterogeneity among Member States implies a territorially differentiated and institutionally coordinated approach to industrial policy and related social and energy policies. Within Member States with a large share of households with persistent energy poverty, there should be a consistency between industrial efficiency measures and labour market policies that improve skills and productivity, thus strengthening the indirect link from modernised industries to better welfare for households. Furthermore, because cost savings from energy efficiency do not automatically and necessarily lead to lower energy prices for households within the existing EU regulatory framework, additional policy tools are needed for mutual reinforcement. These additional tools include, inter alia, reinvesting a certain share of fiscal savings within energy systems related to industrial efficiency efforts into targeted support for households, renovation plans, or energy poverty alleviation actions. By taking an integrated policy approach, energy efficiency can be seen as an instrument not merely promoting a low-carbon society but having an intrinsic link with a just energy transition.

A proper limitation of the research would be that it still lacks a considerable amount of empirical analysis on the income mechanism, despite it being understood as the most realistic methodological explanation for changes caused in energy poverty given changes in industrial energy efficiency. As it stands, because it already probes into productivity changes via labour productivity and country characteristics, it does not address changes within income and changes within income distribution due to changes in industrial efficiency. However, as it stands, as a limitation and pertaining to the research methods and data available, there are no consistent sources available within the Member States of the EU regarding changes within disposable household income stratified per energy vulnerability. However, as it stands, it should be determined that the impact of income would be associated with slow-moving structural changes within and due to productivity changes and associated changes within employment and fiscal adjustment, which would be absorbed within and shown within country fixed effects as opposed to marginal structural effects. A subsequent research stream would be applicable with regard to incorporating microdata on income.

6. Conclusions

The aim of the study was to assess, using panel data models, the impact of improving energy efficiency (using the energy intensity decline measure) in industry on the level of energy poverty in European Union countries, taking into account the macroeconomic environment (income, social, energy and labour market) in EU economies. To this end, panel data models were used for all 27 countries for the period 2003–2023. In pursuit of this objective, six research hypotheses were tested, analysing the impact of the decline in energy intensity, and thus the increase in energy efficiency, on the level of energy poverty measured as the percentage of households unable to keep their homes adequately warm. The testing of these hypotheses provided certain findings which also constitute the added value of this work.

The analysis indicated that:

The energy intensity of industry is one of the key factors influencing energy poverty. The FE-IV result confirms that this relationship is not an artefact of endogeneity; on the contrary, after its removal, the impact of X1 becomes even stronger.

High energy prices significantly worsen the situation of households. The stability of the X4 coefficient between models proves that energy pricing policy and amortisation mechanisms are of paramount importance for reducing energy poverty.

Increased labour productivity indirectly reduces energy poverty. X6→X1→Y is an empirically confirmed channel: countries with higher industrial productivity are characterised by lower energy intensity and thus lower levels of energy poverty.

The article also provides recommendations for energy and economic policy. The results suggest that effective reduction in energy poverty should focus on increasing the energy efficiency of industry, supporting technological modernisation (increased labour productivity), stabilising energy prices for households, and investing in energy infrastructure. The variability between countries contained in the FEs indicates that this policy must be adapted to local structural conditions.

The first hypothesis (H1) indicated that a reduction in the energy intensity of industry leads to a statistically significant reduction in the level of energy poverty, which was positively verified. In both models, FE(HAC) and FE-IV, the coefficient of energy intensity is positive and highly statistically significant, showing that improving the energy efficiency of industry can significantly reduce energy poverty in the EU. Similarly, the second hypothesis (H2) was clearly confirmed. The impact of reducing the energy intensity of industry (X1) on energy poverty (Y) varies greatly between EU countries, although it exists in all countries. These differences persist in both the FE and FE-IV models, indicating deep structural national conditions. The endogeneity correction further highlights that the X1 → Y mechanism has different intensities depending on the country. It was also found that the macro variables X2–X5 are not directly significant in the FE–IV models (p-values: 0.94, 0.35, 0.12, 0.79), while their impact appears through fixed differences between countries (FE) and varying levels of energy intensity of industry in EU countries. The impact of energy intensity is modulated by structural national differences, although not directly by significant macroeconomic and social parameters (X2–X5). Another hypothesis (H3) was also positively verified. This is confirmed by the value of the X1 coefficient of 33.61 (p < 0.001) in the FE model and 73.08 (p = 0.003) in the FE-IV model (cleaned of endogeneity). The fourth hypothesis (H4) was only partially confirmed. It was found that the indirect effect of the decline in energy intensity in industry on the reduction in energy poverty indirectly through the stabilisation of electricity prices exists and is economically meaningful but lacks statistical significance in the FE-IV model, even though the direction of the effect is correct. Changes in energy intensity do not translate into a statistically significant effect on electricity prices (after controlling for other factors and country fixed effects), even though the price of electricity has a positive, partially significant impact on energy poverty. There is therefore no confirmation that a decrease in energy intensity in industry reduces energy poverty indirectly through the stabilisation of energy prices. Hypothesis 5 (H5) found that the analysed data does not confirm that differences in the impact of energy intensity in industry on energy poverty are determined by changes in income levels or labour costs but can only be modified by social support. Therefore, they rather result from the social policy pursued by the state and deeper structural conditions specific to individual countries. Finally, hypothesis H6 was empirically confirmed. It was found that high labour productivity contributes to improving the energy efficiency of industry, which, by reducing energy costs and increasing the stability of the energy system, contributes to reducing the scale of energy poverty in the analysed countries.

In summary, it should be noted that improving energy efficiency in industrial sectors by reducing energy intensity may be an effective way to reduce energy poverty among households across the European Union. At the same time, it was found that the macroeconomic and social environment is a factor that differentiates this impact in individual countries, while on a community-wide scale, no statistically significant direct impact was found.

Undoubtedly, due to existing research limitations, there is room for further in-depth research on the subject. It was found that the chosen methodology was appropriate to address research issues and assess the significance of the topics discussed. The FE model controls for unobserved country-specific and time-specific effects, while the IV approach mitigates bias from endogenous regressors. The combination of these methods ensures robust and credible estimates of the impact of energy efficiency on energy poverty in the EU. However, future research could extend this analysis using dynamic panel models or additional instruments for robustness checks.

Various methodological and conceptual constraints apply to the study, which must be borne in mind when analysing the findings. The data used is a panel dataset covering the period 2003–2023, subject to limitations imposed by the Eurostat datasets available, which may fail to reflect the minute fluctuations in energy demand, resilience, and sectoral shock effects on energy intensity for industry.