Economic and Ecological Benefits of Thermal Modernization of Buildings Related to Financing from Aid Programs in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Programs Co-Financing Thermal Modernization of Single-Family Buildings

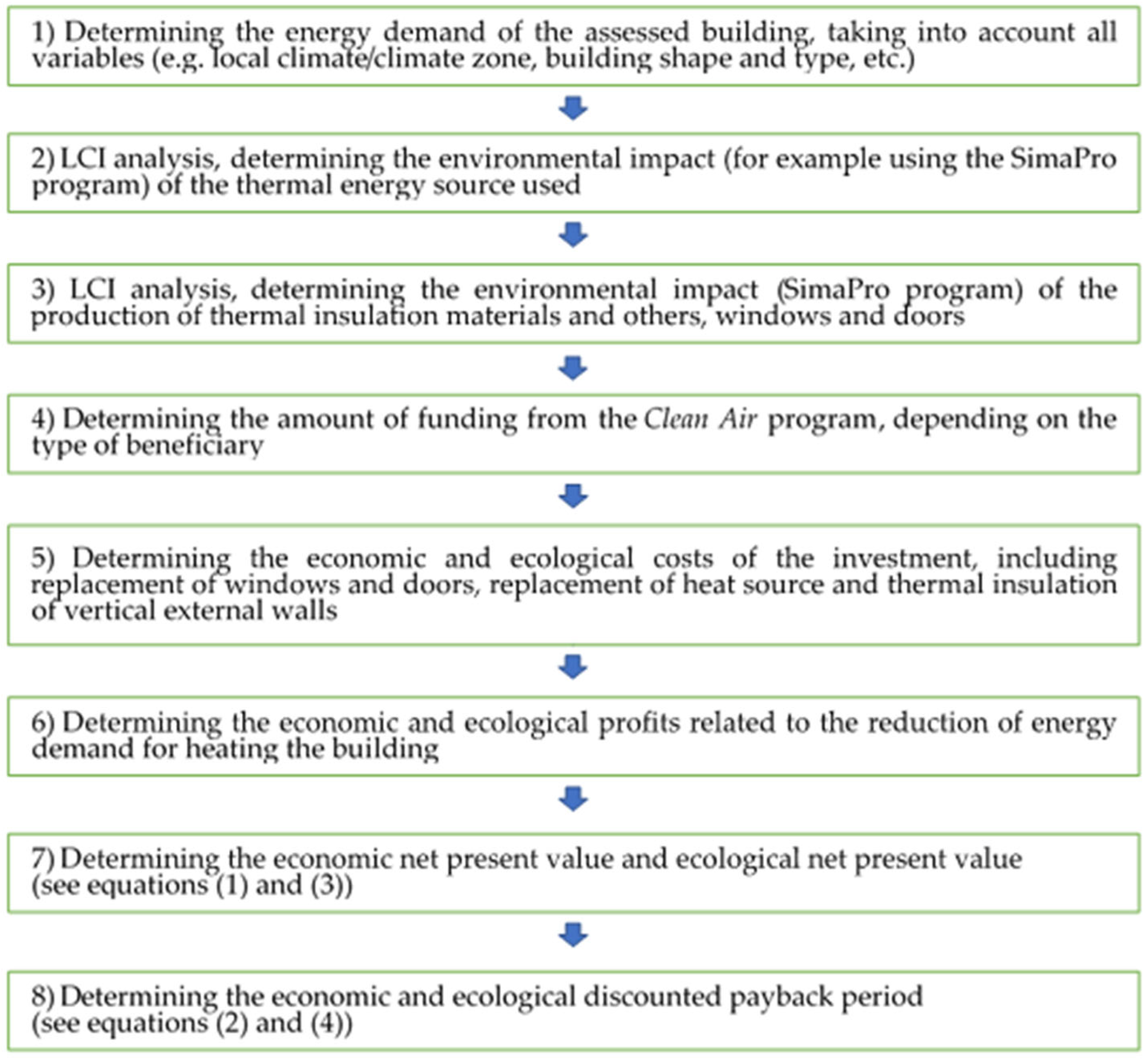

3. Methodology of the Assessment

3.1. Economic Assessment Methodology

3.2. Ecological Assessment Methodology

4. Case Study

4.1. Economic Benefits of the Building’s Thermal Modernization Investment

4.2. Ecological Benefits of the Building’s Thermal Modernization Investment

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

4.4. Economic and Ecological Analysis Depending on the Climate Zone

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Considering environmental aspects, subsidizing thermal modernization investments is entirely justified. Within the first year of a building’s use after completion of the thermal modernization project, the environmental costs are already offset by the benefits resulting from reduced energy demand for heating.

- Subsidies improve the economic viability of the investment and increase investors’ motivation to thermally modernize the building. However, the economic viability of a thermal modernization investment is also determined by external economic factors such as inflation, rising prices, and increased purchasing power. High inflation reduces the value of available financial resources, including those derived from subsidies, which can be a barrier for potential investors. Therefore, it is recommended that the subsidy amount under the Clean Air program (and any other financial investment support program) should be revalued, for example, annually, taking into account the current inflation rate and price dynamics in the construction materials and services market.

- A building’s thermal modernization project, funded by the Clean Air program, can be implemented for a maximum period of 30 months. During this time, the investor is exposed to the risk of rising investment costs, which may lead to the need to abandon the investment and funding. When budgeting for the investment, the investor bases it on current prices. Even if an energy audit is performed before the thermal modernization project begins, there is no guarantee that the specified payback period will be realistic. This risk, borne by the investor, can be relatively reduced by periodic revaluation of the subsidy amount. The above study confirms the proposed change to the Clean Air program, where the high costs of construction materials and services, resulting from high inflation in Poland and geopolitical turmoil, do not guarantee a return on thermal modernization investments, even with program funding (group 2). It should be noted that the primary goal of the Clean Air program is not to provide financial security for investors, but to reduce the environmental pressure of the construction sector.

- Reducing the risk of thermal modernization investment failure by revaluing the subsidy amount is particularly important for beneficiaries with the lowest income levels (groups 4 and possibly 3), where the level of income generated prevents the investment from being implemented.

- State intervention also seems justified, with targeted subsidies directed at various groups of beneficiaries. Investors with high annual incomes are excluded from financial assistance. The subsidy program is aimed at poorer beneficiaries to prevent social exclusion. Despite the demanding requirements for beneficiaries in preparing documentation for the Clean Air program, the assumptions and implementation of this program are socially, ecologically, and economically motivated.

- Implementing a program subsidizing thermal modernization investments aligns with the canon of the sustainable development paradigm.

- From an economic perspective, an investor who does not qualify for subsidies (income exceeding 130,000 PLN) will not receive reimbursement for their costs over a 20-year period. Construction material prices in Poland were on a steady upward trend, with a record 33% increase recorded in 2022. Prices for these materials stabilized only in 2025. The price of fuel for the modernized heating source also impacts the investor’s economic situation.

- The geopolitical situation has significantly impacted energy prices in Poland and globally. Despite the increase in energy prices, investors from groups 1 and 2 will not receive a return on investment within the considered 20-year period of use of thermal insulation.

- Due to the unfavorable energy mix, where “dirty” electricity from coal combustion predominates, the end user is burdened with the consequences of the ETS 1 system, namely the carbon dioxide emission fee. Furthermore, a new ETS 2 system is expected to enter the market, aimed at introducing equality among individual users of heat sources. Social inequality among users of various heat sources results in the fact that owners of single-family buildings using, for example, heat pumps or electric heating pay an additional fee under ETS 1 system when paying for electricity consumption. Other users of boilers fired with coal, gas, heating oil, wood, and pellets do not pay the CO2 emission fee. This situation is expected to change in the coming years. Nevertheless, future changes will not necessarily improve the economic conditions for thermal modernization investments.

- Despite the lack of economic benefits, an investor with a high annual income benefits primarily from thermal comfort through a thermal modernization investment, which improves the quality of life for all building users. Moreover, by using more environmentally friendly heating equipment that emits less carbon dioxide and other pollutants, the investor impacts local and regional air quality, improving the quality of life for their neighbors, both near and far. These aspects are difficult to economically assess and are often overlooked in this type of investment. Furthermore, as demonstrated in the study, a thermal modernization investment is environmentally friendly and environmentally sustainable. A thermal modernization investment is conditioned environmentally, socially, and sometimes economically, which largely depends on the economic situation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Igugu, H.O.; Laubscher, J.; Mapossa, A.B.; Popoola, P.A.; Dada, M. Energy Efficiency in Buildings: Performance Gaps and Sustainable Materials. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1411–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiarz, B.; Krawczyk, D.A.; Siuta-Olcha, A.; Manuel, C.D.; Jaworski, A.; Barnat, E.; Cholewa, T.; Sadowska, B.; Bocian, M.; Gnieciak, M.; et al. Energy Efficiency in Buildings: Toward Climate Neutrality. Energies 2024, 17, 4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzikuć, M.; Piwowar, A.; Szufa, S.; Adamczyk, J.; Dzikuć, M. Potential and Scenarios of Variants of Thermo-Modernization of Single-Family Houses: An Example of the Lubuskie Voivodeship. Energies 2021, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brożyna, J.; Strielkowski, W.; Zpěvák, A. Evaluating the Chances of Implementing the “Fit for 55” Green Transition Package in the V4 Countries. Energies 2023, 16, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, A.; Fura, B.; Zajączkowska, M. Assessment of Energy Efficiency in the European Union Countries in 2013 and 2020. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trębska, P. Wykorzystanie energii przez gospodarstwa domowe w Polsce. Rocz. Nauk. Stowarzyszenia Ekon. Rol. I Agrobiznesu 2018, 20, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Garcia, A.; Guardiola-Víllora, A.; Pérez, G. Building’s eco-efficiency improvements based on reinforced concrete multilayer structural panels. Energy Build. 2014, 85, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Action Progress Report; Country Profile: Poland, 2023; 5p. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/document/download/c87bf87e-3785-46df-b270-4461814adeaa_en?filename=pl_2023_factsheet_en.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Pytliński, Ł. Efektywność Energetyczna Budynków, Instytut Ekonomii Środowiska, 2022. Available online: https://naradaoenergii.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Efektywnoscenergetycznabudynkow23.1.222.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025). (In Polish).

- How Europe Can Fill the Clean Heat Gap, Report, 2024, p. 21. Available online: https://www.solarpowereurope.org/advocacy/position-papers/how-can-europe-fill-the-clean-heat-gap (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Starościcki, J. Report: Heating Device Market in Poland in 2019; Association of Heating Device Manufacturers and Importers: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; Available online: https://instalacje.com/media/ai1ibc1x/heating-device-market-in-poland-in-2019.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Kryszk, H.; Kurowska, K.; Marks-Bielska, R.; Bielski, S.; Eźlakowski, B. Barriers and Prospects for the Development of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland during the Energy Crisis. Energies 2023, 16, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwiazda, M. Strategie rozwoju elektroenergetyki. In Polacy o Źródłach Energii, Polityce Energetycznej i Stanie Środowiska; Gwiazda, M., Ruszkowski, P., Eds.; Opinie i diagnozy nr 34; COBS: Warszawa, Poland, 2016; Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/PL/publikacje/diagnozy/034.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025). (In Polish)

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS). Efektywność Wykorzystania Energii w Latach 2011–2021; Analizy statystyczne; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2023; p. 22. Available online: http://www.stat.gov.pl/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Dańkowska, A.; Stasik, A.; Niedziółka, T.; Dembek, A. Getting warmed up: Challenges to participatory decarbonization of a local residential heating system in Poland. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2025, 55, 100959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciupek, B.; Judt, W.; Gołoś, K.; Urbaniak, R. Analysis of Low-Power Boilers Work on Real Heat Loads: A Case of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Approval of the Content of the Draft Commission Notice Providing Guidance on New or Substantially Modified Provisions of the Recast Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EU) 2024/1275; C(2025) 4132 final; Fossil Fuel Boilers (Article 13, Annex II); Communication to the Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- Eurostat. Minimum Wages, 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00155/default/table (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Podwyżka Płacy Minimalnej: Rada Ministrów Przyjęła Propozycję Ministry Rodziny, Pracy i Polityki Społecznej. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rodzina/podwyzka-placy-minimalnej-rada-ministrow-przyjela-propozycje-ministry-rodziny-pracy-i-polityki-spolecznej (accessed on 21 March 2025). (In Polish)

- Dzikuć, M. Environmental management with the use of LCA in the Polish energy system. Management 2015, 19, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigovskaya, A.; Aleksandrova, O.V.; Bulgakov, B. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) in building materials industry. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 106, 8059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, M.; Rivero-Camacho, C.; Martínez-Rocamora, A.; Alba-Rodríguez, M.D.; Solís-Guzmán, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Industrial Building Construction and Recovery Potential. Case Studies in Seville. Processes 2022, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Liu, P.; Hossain, M.U. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of Building Construction: A Case Study in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, J.; Dylewski, R. Ecological and Economic Benefits of the “Medium” Level of the Building Thermo-Modernization: A Case Study in Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Alam, T.; Khan, M.S.; Blecich, P.; Kamal, M.A.; Gupta, N.K.; Yadav, A.S. Life Cycle Assessment of Embodied Carbon in Buildings: Background, Approaches and Advancements. Buildings 2022, 12, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment-Principles and Framework. European Committee for Standardisation: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment-Requirements and Guidelines. European Committee for Standardisation: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- Program Czyste Powietrze. 2025. Available online: https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/wez-dofinansowanie/dokumenty-programowe/dokumenty-obowiazujace (accessed on 21 March 2025). (In Polish)

- Dzikuć, M.; Dzikuć, M.; Siničáková, M. The social aspects of low emission management in the Nowa Sól district. Management 2017, 21, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórska, M.; Klimkowska, J. Matematyka Finansowa; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- PN-EN 12831-1:2017-08; Charakterystyka energetyczna budynków—Metoda obliczania projektowego obciążenia cieplnego—Część 1: Obciążenie cieplne, Moduł M3-3. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warszawa, Poland, 2017.

- Beck, H.; Zimmermann, N.; McVicar, T.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E. Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TECNALIA. European Climate Zones and Bio-Climatic Design Requirements; Report 1; TECNALIA: Zamudio, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5ac7b5027&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Dylewski, R.; Adamczyk, J. Economic and Ecological Optimization of Thermal Insulation Depending on the Pre-Set Temperature in a Dwelling. Energies 2023, 16, 4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca Reina, J.C.; Toleikyte, A.; Volt, J.; Carlsson, J. Alternatives for upgrading from high-temperature to low-temperature heating systems in existing buildings: Challenges and opportunities. Energy Build. 2024, 323, 114798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasonic, Aquarea Air to Water Heat Pump. Available online: https://www.panasonicproclub.com/uploads/HR/catalogues/EU_AQUAREA_231211.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Fregonara, E.; Ferrando, D. The Discount Rate in the Evaluation of Project Economic-Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likins-White, M.; Tenent, R.C.; Zhai, Z. Degradation of Insulating Glass Units: Thermal Performance, Measurements and Energy Impacts. Buildings 2023, 13, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, Z.; Twardowski, S.; Malinowski, M.; Kubon, M. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and energy assessment of the production and use of windows in residential buildings. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafranko, E. Methodology for assessment of the cost effectiveness of simple energy efficient investments. BoZPE 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Harmsen, R.; Yang, T.; Kramer, G.J. The role of behavior on variation in domestic space heating demand in similar dwellings: What does it mean for the payback period of re-insulation? Energy 2025, 335, 138013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawada, B.; Rucińska, J. Optimization of Modernization of a Single-Family Building in Poland Including Thermal Comfort. Energies 2021, 14, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labanca, N.; Suerkemper, F.; Bertoldi, P.; Irrek, W.; Duplessis, B. Energy efficiency services for residential buildings: Market situation and existing potentials in the European Union. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Poland’s Climate Zones | I | II | III | IV | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building’s usable energy demand EU0 [kWh/(m2Year)] | 133.54 | 144.41 | 143.70 | 166.33 | 178.42 |

| Building’s usable energy demand EU [kWh/(m2Year)] | 74.12 | 81.43 | 80.05 | 95.50 | 104.13 |

| Reducing the demand for usable energy | 44.5% | 43.6% | 44.3% | 42.6% | 41.6% |

| Building location (city) | Szczecin | Zielona Góra | Warszawa | Białystok | Suwałki |

| Type of Beneficiary | (Group 1) Income Above 135,000 PLN/Year | (Group 2) Basic Level Income Below 135,000 PLN/Year | (Group 3) Higher Level Income: 2250 PLN/Person Month or 3150 PLN/Person Month | (Group 4) Highest Level Income: 1300 PLN/Person Month or 1800 PLN/Person Month |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum subsidy for replacing the heat source with an air/water heat pump | No funding | 14,520.00 | 25,410.00 | 36,300.00 |

| Maximum funding for thermal insulation of vertical walls and window replacement | No funding | 26,763.60 | 46,836.30 | 66,909.00 |

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 [PLN] | 103,209.00 | 103,209.00 | 103,209.00 | 103,209.00 |

| D [PLN] | 0.00 | 41,283.60 | 72,246.30 | 103,209.00 |

| Pi [PLN/year] | 2499.84 | 2499.84 | 2499.84 | 2499.84 |

| NPV [PLN] | −62,102.30 | −20,818.70 | 10,144.00 | 41,106.70 |

| Tp [years] | 85 | 35 | 15 | 1 |

| Heat Pump | Thermal Energy Production—Hard Coal (60% Efficiency) | Thermal Energy Production—Heat Pump (SCOP = 3.50) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional unit | 1 pc. | 1 kWh | 1 kWh |

| LCA analysis result [Pt] | 1050 | 0.207 | 0.031 |

| LCA analysis result [kg CO2 eq] | 3600 | 1.78 | 0.30 |

| Total result of the LCA analysis for the building | 1050 Pt | 3972.33 Pt/year 79,446.68 Pt/20 years | 331.34 Pt/year 6626.87 Pt/20 years |

| Acrylic Plaster + Primer Emulsion | Styrofoam Dowels | Fiberglass Mesh | Graphite Styrofoam, 15 cm Thick | Glue for Polystyrene/Mesh | Windows, PVC Doors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional unit | 1 kg | 1 kg | 1 m2 | 1 m2 | 1 kg | 1 m2 |

| LCA analysis result [Pt] | 0.612 | 0.243 | 0.193 | 1.14 | 0.265 | 12.3 |

| LCA analysis result [kg CO2 eq] | 3.05 | 2.36 | 2.28 | 11.1 | 1.48 | 108 |

| Total result of the LCA analysis for the building | 388.62 Pt | 1.458 Pt | 12.06 Pt | 237.36 Pt | 503.50 Pt | 363.22 Pt |

| P0E [Pt] | 2566.22 |

| PiE [Pt/year] | 3640.99 |

| NPVE [Pt] | 70,263.60 |

| TpE [years] | 1 |

| N = 15 years | N = 20 years | N = 25 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | NPV [PLN] | −70,947.46 | −62,102.30 | −54,068.05 |

| Tp [years] | 85 | 85 | 85 | |

| Group 2 | NPV [PLN] | −29,663.86 | −20,818.70 | −12,784.45 |

| Tp [years] | 35 | 35 | 35 | |

| Group 3 | NPV [PLN] | 1298.84 | 10,144.00 | 18,178.25 |

| Tp [years] | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| Group 4 | NPV [PLN] | 32,261.54 | 41,106.70 | 49,140.95 |

| Tp [years] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| - | NPVE [Pt] | 52,058.64 | 70,263.60 | 88,468.55 |

| TpE [years] | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| P0 − 10%P0 [PLN] | P0 [PLN] | P0 + 10%P0 [PLN] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | NPV [PLN] | −51,781.40 | −62,102.30 | −72,423.20 |

| Tp [years] | 67 | 85 | 112 | |

| Group 2 | NPV [PLN] | −14,626.16 | −20,818.70 | −27,011.24 |

| Tp [years] | 30 | 35 | 40 | |

| Group 3 | NPV [PLN] | 13,240.27 | 10,144.00 | 7047.73 |

| Tp [years] | 13 | 15 | 16 | |

| Group 4 | NPV PLN] | 41,106.70 | 41,106.70 | 41,106.70 |

| Tp [years] | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| P0E − 10%P0E [PLN] | P0E [Pt] | P0E + 10%P0E [PLN] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPVE [Pt] | 70,519.22 | 70,263.60 | 70,007.98 |

| TpE [years] | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| s = 2% | s = 3% | s = 4% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | NPV [PLN] | −65,814.61 | −62,102.30 | −57,922.81 |

| Tp [years] | - | 85 | 53 | |

| Group 2 | NPV [PLN] | −24,531.01 | −20,818.70 | −16,639.21 |

| Tp [years] | 45 | 35 | 29 | |

| Group 3 | NPV [PLN] | 6431.69 | 10,144.00 | 14,323.49 |

| Tp [years] | 16 | 15 | 14 | |

| Group 4 | NPV [PLN] | 37,394.39 | 41,106.70 | 45,286.19 |

| Tp [years] | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Poland’s Climate Zones | I | II | III | IV | V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | NPV [PLN] | −64,436.05 | −62,102.30 | −61,673.42 | −56,963.94 | −54,690.02 |

| Tp [years] | 99 | 85 | 82 | 65 | 60 | |

| Group 2 | NPV [PLN] | - | −20,818.70 | −20,389.82 | −15,680.34 | −13,406.42 |

| Tp [years] | - | 35 | 34 | 30 | 28 | |

| Group 3 | NPV [PLN] | - | 10,144.00 | 10,572.88 | 15,282.36 | 17,556.28 |

| Tp [years] | - | 15 | 15 | 13 | 12 | |

| Group 4 | NPV [PLN] | - | 41,106.70 | 41,535.58 | 46,245.06 | 48,518.98 |

| Tp [years] | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| - | NPVE [Pt] | 64,878,40 | 70,263.60 | 69,985.30 | 81,177.78 | 87,126.73 |

| TpE [years] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Adamczyk, J.; Dylewski, R. Economic and Ecological Benefits of Thermal Modernization of Buildings Related to Financing from Aid Programs in Poland. Energies 2026, 19, 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010260

Adamczyk J, Dylewski R. Economic and Ecological Benefits of Thermal Modernization of Buildings Related to Financing from Aid Programs in Poland. Energies. 2026; 19(1):260. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010260

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamczyk, Janusz, and Robert Dylewski. 2026. "Economic and Ecological Benefits of Thermal Modernization of Buildings Related to Financing from Aid Programs in Poland" Energies 19, no. 1: 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010260

APA StyleAdamczyk, J., & Dylewski, R. (2026). Economic and Ecological Benefits of Thermal Modernization of Buildings Related to Financing from Aid Programs in Poland. Energies, 19(1), 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010260