Energy-Efficient Operation of Industrial Induction Motors Exposed to Multiple Power Quality Disturbances

Abstract

1. Introduction

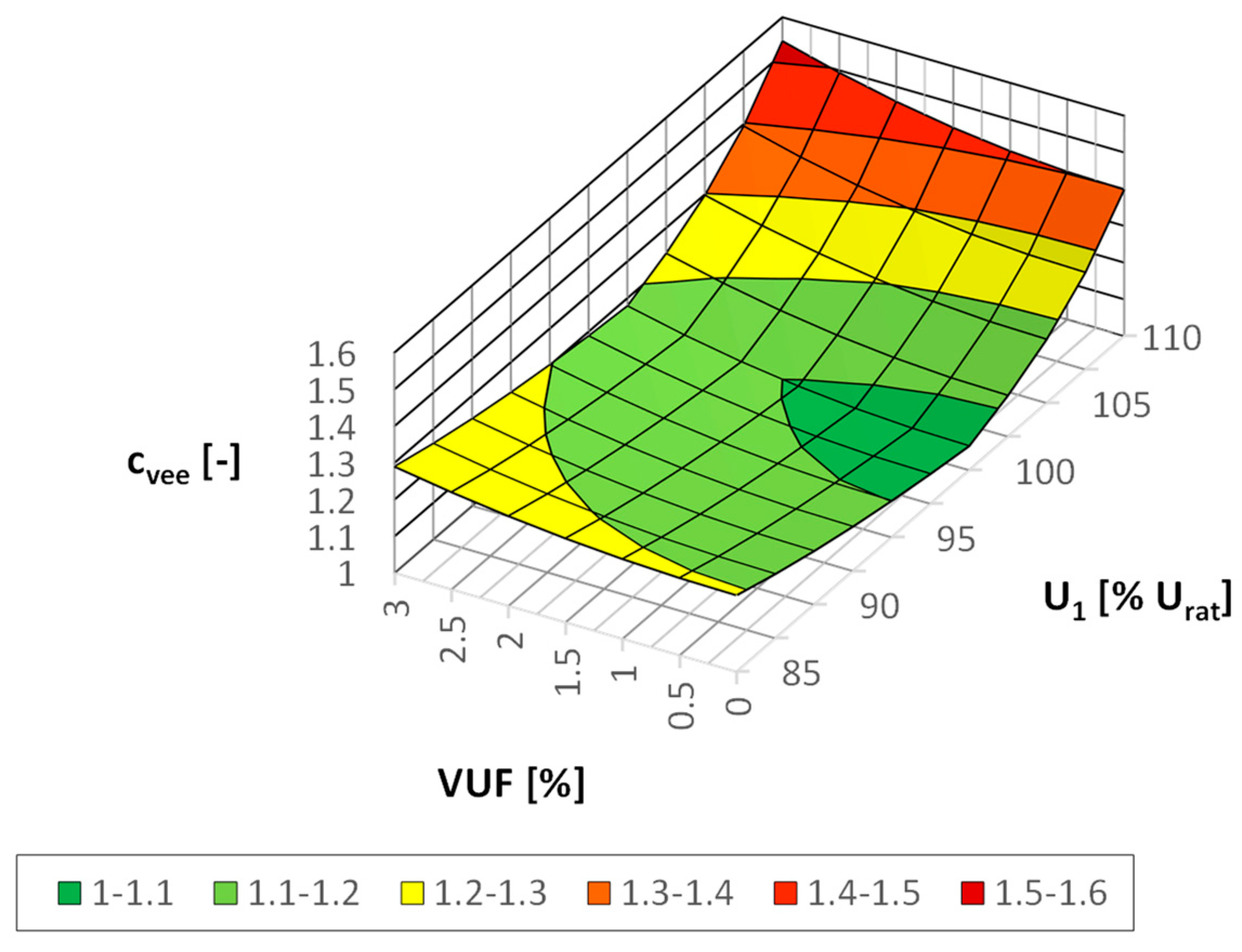

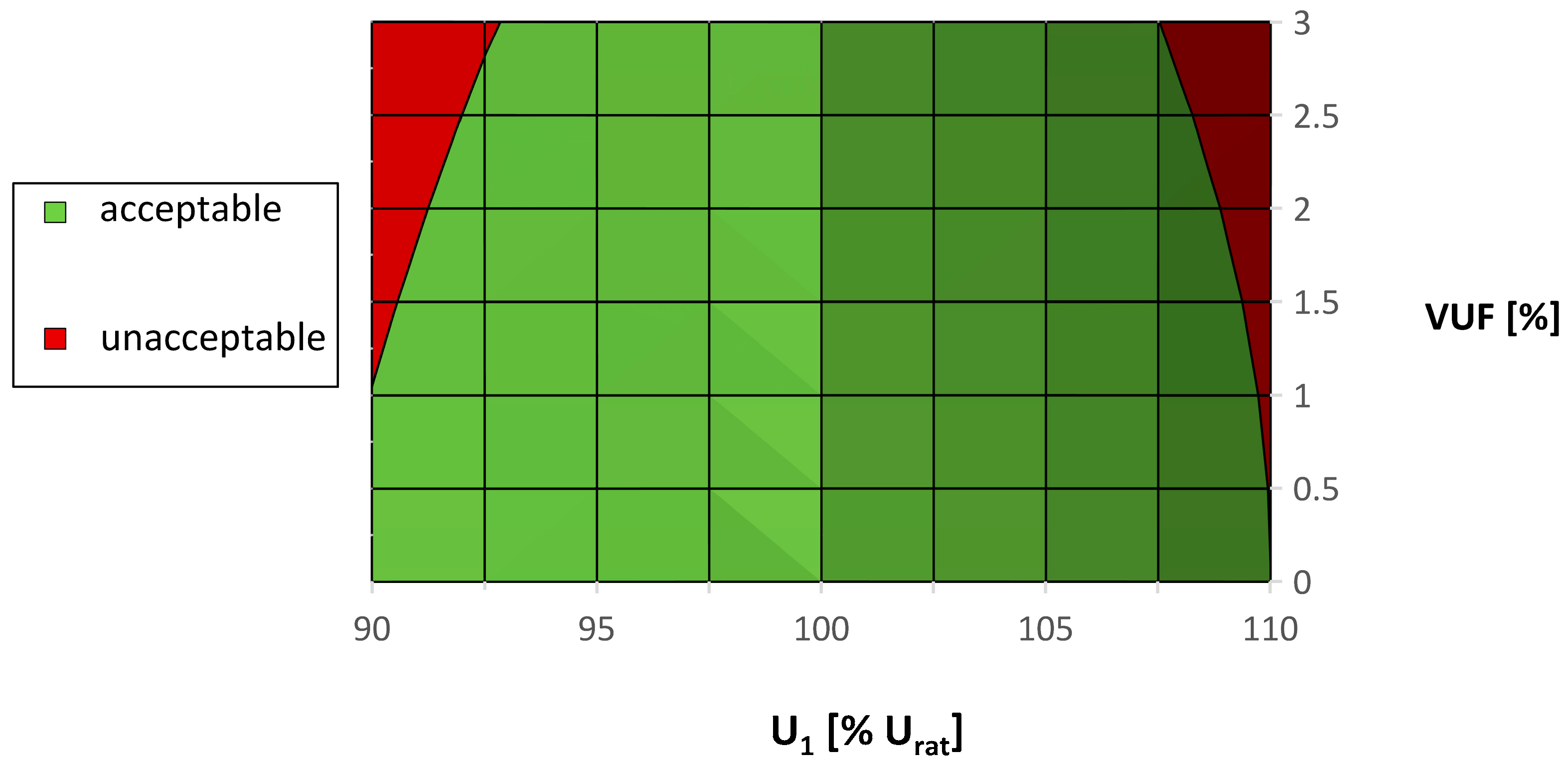

2. Coefficient of Voltage Energy Efficiency and Power Quality Assessment

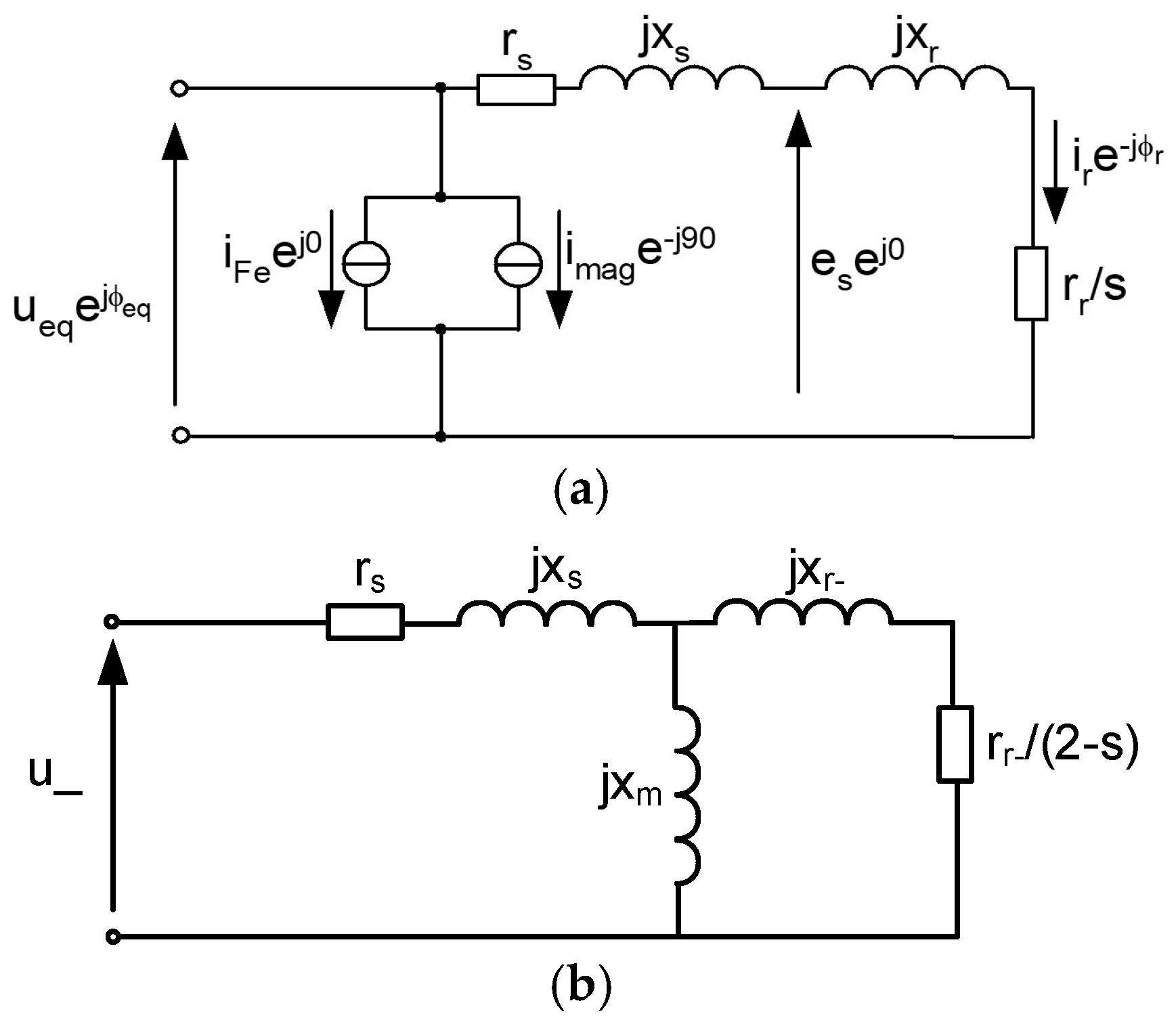

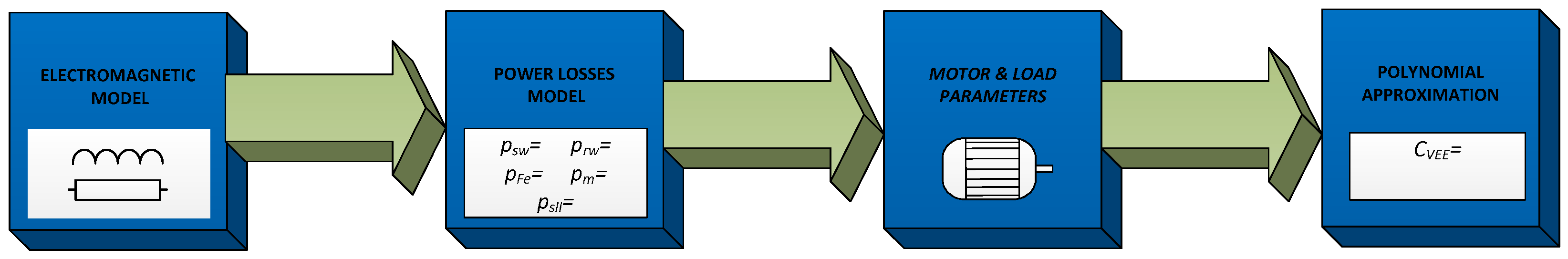

2.1. Derivation of the Coefficient of Voltage Energy Efficiency

2.2. Coefficient of Voltage Energy Efficiency as a Power Quality Index

3. Possible Levels of the Coefficient of Voltage Energy Efficiency in Land Power Systems

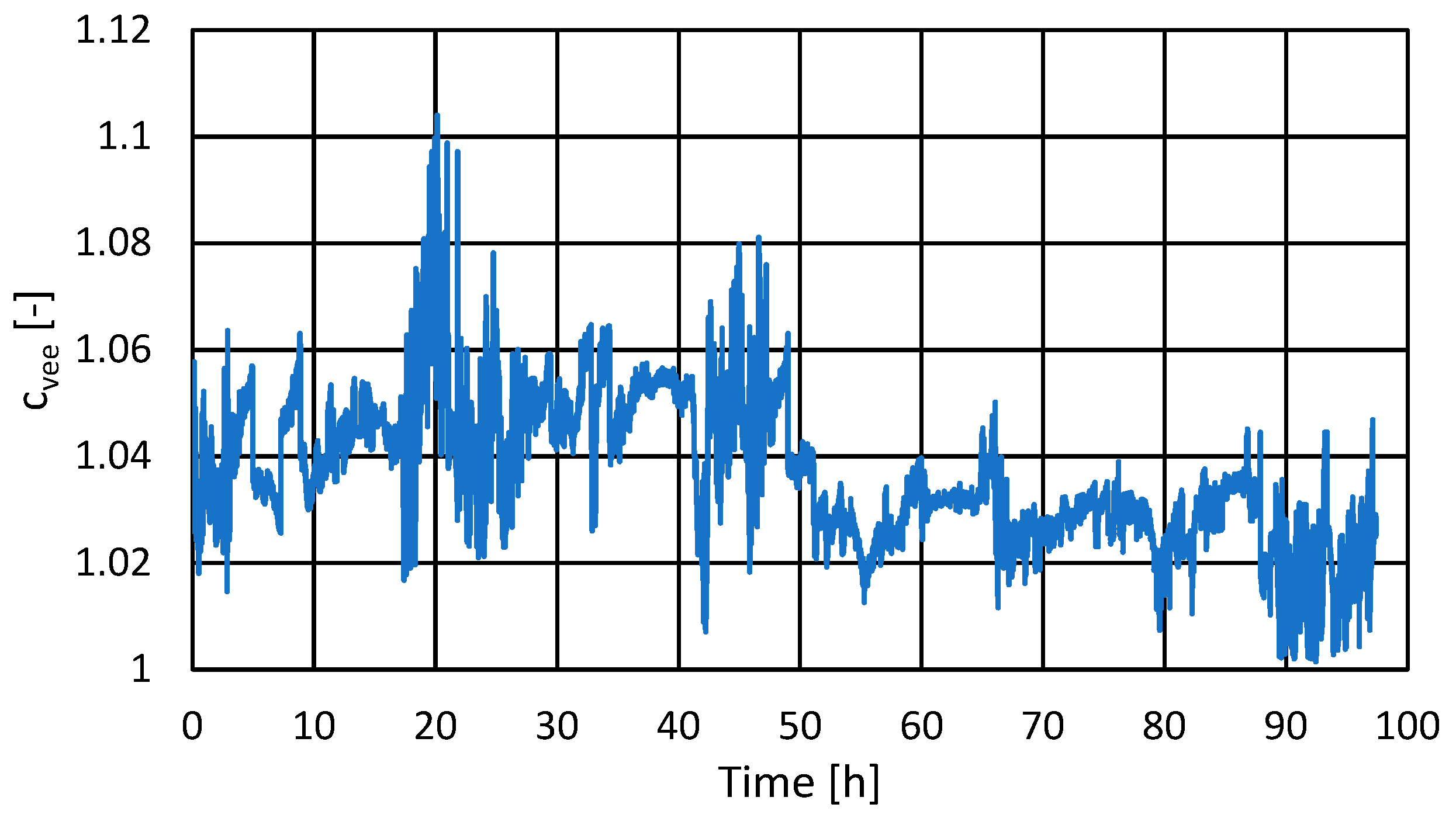

4. Coefficient of Voltage Energy Efficiency in a Real Power System

4.1. Methodology of Measurement

4.2. Results of Power Quality and cvee Coefficient Monitoring

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beleiu, H.G.; Pavel, S.G.; Birou, I.M.; Miron, A.; Darab, P.C.; Sallah, M. Effects of voltage unbalance and harmonics on drive systems with induction motor. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2022, 16, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN-IEC 60034-30-1:2014; Rotating Electrical Machines—Part 30-1: Efficiency Classes of Line Operated AC Motors (IE Code). International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Huang, S.; Xiong, L.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, F.; Jia, Q.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Khan, M.W. Robust distributed fixed-time fault-tolerant control for shipboard microgrids with actuator fault. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 11, 1791–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, S.; Peyghami, S.; Parniani, M.; Blaabjerg, F. Power management strategies based on propellers speed control in waves for mitigating power fluctuations of ships. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 3247–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donolo, P.; Pezzani, C.; Bossio, G.; de Angelo, C.; Donolo, M. Vibration magnitude analysis on induction motors of different efficiency classes due to voltage unbalance. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 2913–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S.H.; Seifossadat, S.G.; Saniei, M.; Moosapour, S.S. Derating factor determination of the three-phase induction motor under unbalanced voltage using pumping system. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2024, 18, 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadir, B.; Azzeddine, D.; Ahmed, B.; Issam, A. Exploring the effects of overvoltage unbalances on three phase induction motors: Insights from motor current spectral analysis and discrete wavelet transform energy assessment. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 117, 109242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.J.T.E.; Alberto, J.M.; de Almeida, A.T. Assessment of induction motor tolerance to supply voltage unbalance for different dual-winding configurations. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaier, A.A.; Flah, A.; Kraiem, H.; Enany, M.A.; Elymany, M.M. Novel technique for precise derating torque of induction motors using ANFIS. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beleiu, H.G.; Miron, A.; Pavel, S.G.; Cziker, A.C.; Niste, D.F.; Darab, P.C. Impact of voltage unbalance and harmonics on induction motor efficiency. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference and Exposition on Electric and Power Engineering (EPEi), Iasi, Romania, 17–19 October 2024; pp. 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, S.X.; Kagan, N. A power-quality index to assess the impact of voltage harmonic distortions and unbalance to three-phase induction motors. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2010, 25, 1846–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnaciński, P. Effect of power quality on windings temperature of marine induction motors: Part I: Machine model. Energy Convers. Manag. 2009, 50, 2463–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnacinski, P.; Mindykowski, J.; Peplinski, M.; Tarasiuk, T.; Costa, J.D.; Assuncao, M.; Silveira, L.; Zakharchenko, V.; Drankova, A.; Mukha, M.; et al. Coefficient of voltage energy efficiency. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 75043–75059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnacinski, P.; Tarasiuk, T. Energy-efficient operation of induction motors and power quality standards. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2016, 135, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnaciński, P.; Tarasiuk, T.; Mindykowski, J.; Pepliński, M.; Górniak, M.; Hallmann, D.; Piłlat, A. Power quality and energy-efficient operation of marine induction motors. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 152193–152203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnacinski, P. Windings temperature and loss of life of an induction machine under voltage unbalance combined with over-or undervoltages. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2008, 23, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.D.; Ferreira Filho, A.D.L. An alternative methodology for quantifying voltage unbalance based on the effects of the temperatures and efficiency of induction motors. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 83567–83579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN Standard 50160; Voltage Characteristics of Electricity Supplied by Public Distribution Network. CELENEC: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- EN-IEC 61000-2-4:2024; Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)-Part 2-4: Environment-Compatibility Levels in Power Distribution Systems in Industrial Locations for Low-Frequency Conducted Disturbances. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Rozal Filho, E.O.; Tabora, J.M.; Tostes MEde, L.; de Matos, E.O.; Soares, T.M.; Bezerra, U.H.; Manito, A.R. Harmonic classifier for efficiency induction motors using ANN. Rev. Contemp. 2023, 3, 17660–17678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laadjal, K.; Amaral, A.M.; Sahraoui, M.; Cardoso, A.J.M. Machine learning based method for impedance estimation and unbalance supply voltage detection in induction motors. Sensors 2023, 23, 7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, M.; Singh, A.K. A global power quality index for assessment in distributed energy systems connected to a harmonically polluted network. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2025, 47, 8331–8357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, G.R.; dos Santos Pereira, G.M.; Biasuz Block, P.A.; Riboldi, V.B.; Ji, T.; Chen, X. Unified power quality index method using AHP for consumers sensitivity evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE PES Transmission & Distribution Conference and Exhibition-Latin America (T&D LA), Montevideo, Uruguay, 28 September–2 October 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, Z.; Weng, X.; He, M.; Zhang, G.; Yuan, D.; Jin, T. A novel approach for evaluating power quality in distributed power distribution networks using AHP and S-transform. Energies 2024, 17, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, D.L.; Ghatpande, O.A.; Nazir, M.; Heredia, W.G.B.; Feng, W.; Brown, R.E. Energy and power quality measurement for electrical distribution in AC and DC microgrid buildings. Appl. Energy 2022, 308, 118308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xu, P.; Shao, X. Comprehensive evaluation of power quality of coal mine power grid based on equilibrium empowerment and improved grey relational projection method. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1680–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsotohy, A.M.; Ali, M.H.; Adail, A.S.; Eisa, A.A.; Othman, E.S.A. Developing a dynamic combined power quality index for assessing the performance of a nuclear facility. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasinski, M.; Sikorski, T.; Kaczorowska, D.; Kostyla, P.; Leonowicz, Z.; Rezmer, J.; Janik, P.; Bejmert, D. Global power quality index application in virtual power plant. In Proceedings of the 2020 12th International Conference and Exhibition on Electrical Power Quality and Utilisation-(EPQU), Cracow, Poland, 14–15 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, J.; Hao, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Qin, L. A Grid-wide comprehensive evaluation method of power quality based on complex network theory. Energies 2024, 17, 3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.T.; Fang, X.L.; Lin, Y.; Lan, J.C.; Zhang, Z.G. Comprehensive evaluation of power quality based on AHM-CRITIC method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2355, 012053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.J.; de Almeida, A.T. Method for in-field evaluation of the stator winding connection of three-phase induction motors to maximize efficiency and power factor. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2006, 21, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61000-4-30; Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)—Part 4–30: Testing and Measurement Techniques—Power Quality Measurement Methods. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- IEC 61000-4-7; Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)—Part 4-7: Testing and Measurement Techniques—General Guide on Harmonics and Interharmonics Measurements and Instrumentation for Power Supply Systems and Equipment Connected Thereto. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Dogaru, V.G.; Dogaru, F.D.; Năvrăpescu, V.; Constantinescu, L.M. From the photovoltaic effect to a low voltage photovoltaic grid challenge—A review. Rev. Roum. Sci. Tech. Série Électrotech. Énergétique 2024, 69, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistical Parameter | Pfund Value | Phar Value | Punbal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | 1.141 | 0.013 | 0.002 |

| Mean | 1.049 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Standard deviation | 0.031 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Statistical Parameter | Pfund Value | Phar Value | Punbal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | 1.089 | 0.031 | 0.001 |

| Mean | 1.034 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Standard deviation | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Statistical Parameter | Pfund Value | Phar Value | Punbal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | 1.057 | 0.011 | 0.010 |

| Mean | 1.027 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Standard deviation | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gnaciński, P.; Gorniak, M.; Tarasiuk, T. Energy-Efficient Operation of Industrial Induction Motors Exposed to Multiple Power Quality Disturbances. Energies 2026, 19, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010026

Gnaciński P, Gorniak M, Tarasiuk T. Energy-Efficient Operation of Industrial Induction Motors Exposed to Multiple Power Quality Disturbances. Energies. 2026; 19(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleGnaciński, Piotr, Mariusz Gorniak, and Tomasz Tarasiuk. 2026. "Energy-Efficient Operation of Industrial Induction Motors Exposed to Multiple Power Quality Disturbances" Energies 19, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010026

APA StyleGnaciński, P., Gorniak, M., & Tarasiuk, T. (2026). Energy-Efficient Operation of Industrial Induction Motors Exposed to Multiple Power Quality Disturbances. Energies, 19(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010026