Optimal Design Guidelines for Efficient Energy Harvesting in Piezoelectric Bladeless Wind Turbines

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Backgrounds

1.2. Research Objectives

- (a)

- To integrate the mechanical and electrical modeling of the BWT structure and piezoelectric elements and to identify key design parameters;

- (b)

- To develop a design methodology that achieves optimal power generation at a given rated wind speed;

- (c)

- To verify the proposed optimum design criteria using both simulations based on existing models and experimental results.

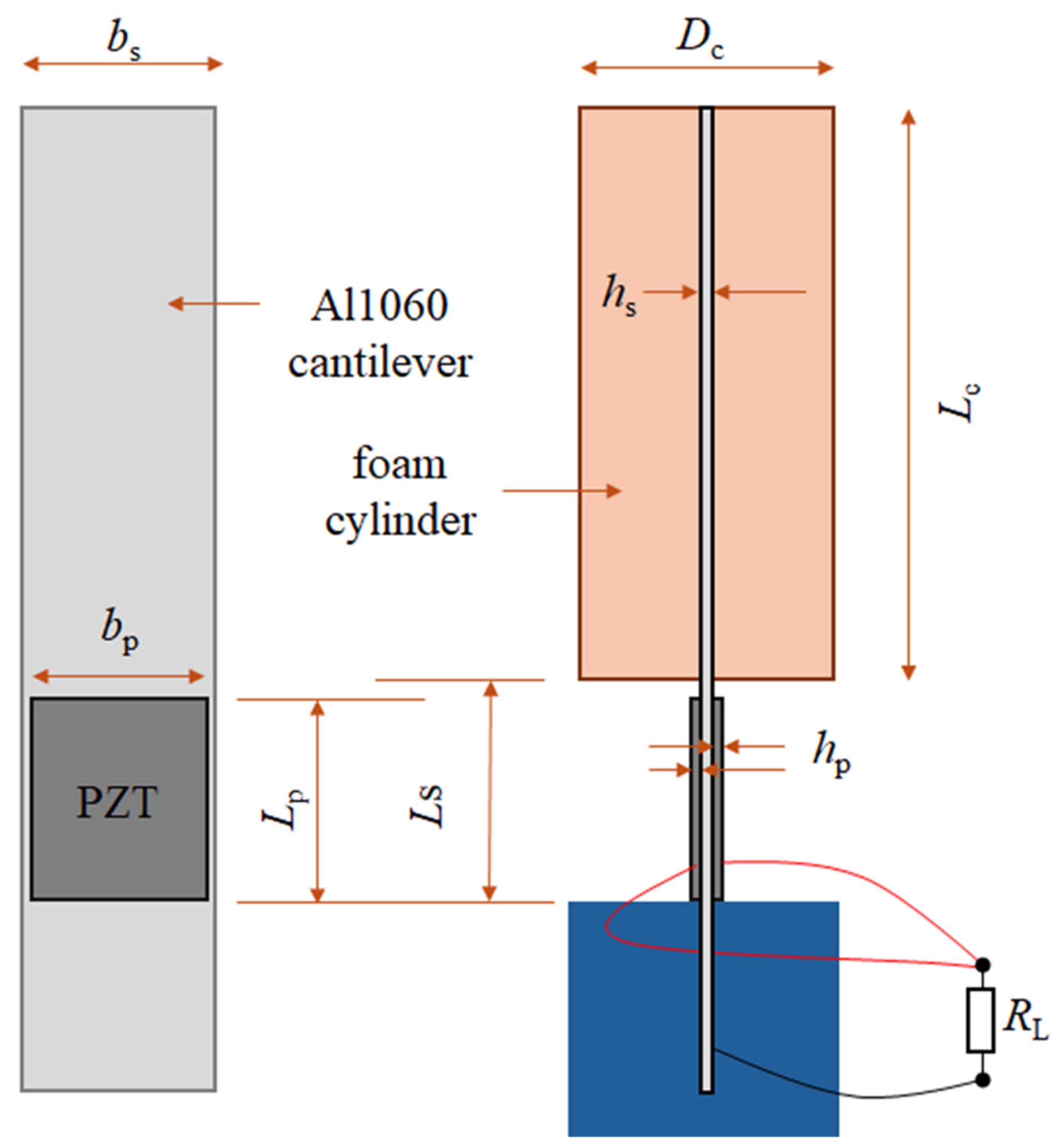

2. Mathematical Model for BWT Energy Harvester

2.1. System Concept and Assumptions for BWT

2.1.1. Main Assumptions for Analysis

- (a)

- The cantilever is assumed to vibrate only in its first bending mode, which dominates the system response.

- (b)

- The cantilever beam is thin relative to its length and is modeled as an Euler–Bernoulli beam; Axial deformations are neglected.

- (c)

- Deformation of the foam cylinder, and the cantilever section where the cylinder is attached is neglected.

- (d)

- Additional damping effects due to clamping, cylinder bending, or other factors are not modeled. Instead, the damping ratio for the resonance mode is determined experimentally.

- (e)

- The incoming wind is assumed to be laminar.

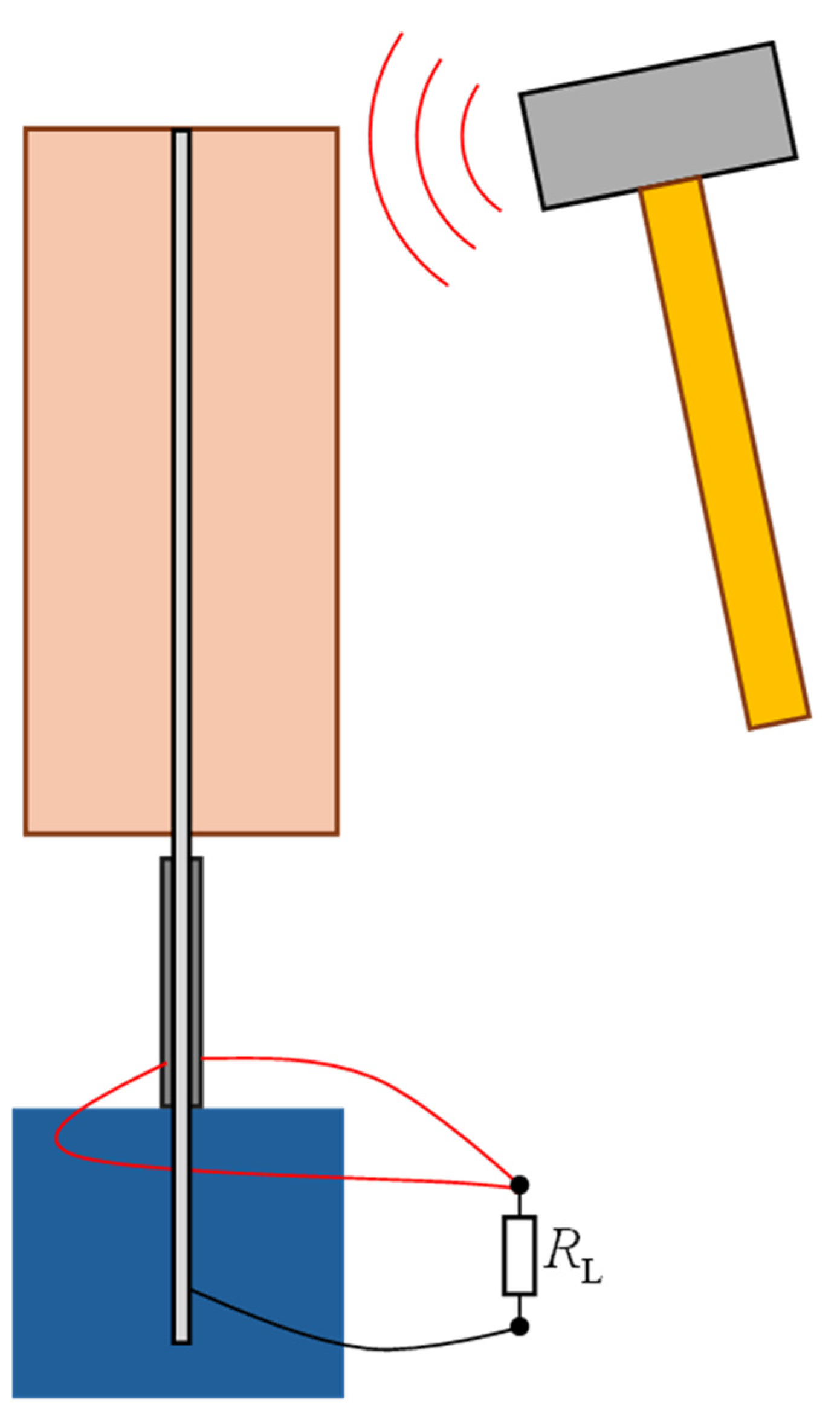

2.1.2. Basic Working Principles of BWT System

- (a)

- Vortex-Induced Vibration (VIV):

- (b)

- Coupled Vibration of Cylinder and Cantilever:

- (c)

- Piezoelectric Energy Conversion:

2.2. Mathematical Model

2.2.1. Vibrational Behavior of Cantilever Beam

2.2.2. Electrical Behavior of Piezoelectric Energy Harvester

2.2.3. Vibrational Behavior of Karman Vortex

3. Optimal Design Method

3.1. Derivation of Optimal Design Rule

- (a)

- Optimal energy harvesting is achieved when the natural frequency of the structure matches the vortex shedding frequency.

- (b)

- For the direct resistive load configuration, the generated current primarily flows through the load resistance under optimal conditions.

- (c)

- The solution of the van der Pol equation is assumed to be a sinusoidal wave with constant angular frequency and constant amplitude under the optimal operating condition, with a default amplitude value of .

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

3.2. Optimal Design Execution

3.2.1. Cantilever Design

3.2.2. PZT Design

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Free Vibration of the Structure

4.2. PZT Output Voltage at 4 m/s Wind Speed

4.3. Power Output vs. Wind Speed

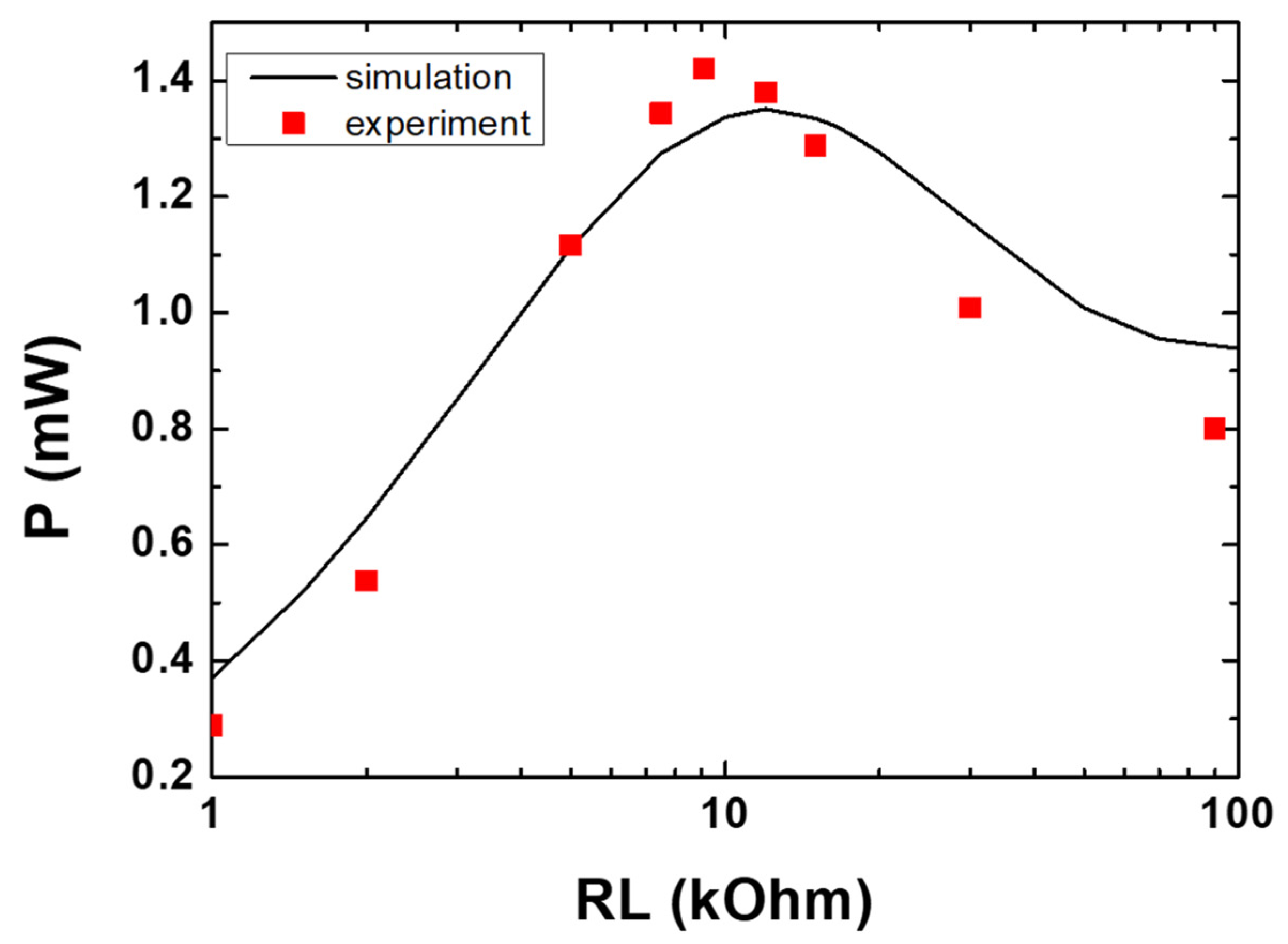

4.4. Power Output vs. Load Resistance

5. Conclusions

- (a)

- Tuning the structural natural frequency to match the vortex shedding frequency for resonance;

- (b)

- Designing the load resistance such that the non-dimensional load resistance equals to 1;

- (c)

- Selecting piezoelectric materials and load resistance that ensure the value of remains sufficiently smaller than unity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Premalatha, M.; Abbasi, T.; Abbasi, S.A. Wind energy: Increasing deployment, rising environmental concerns. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 31, 270–288. [Google Scholar]

- Lucena, J.d.A.Y. Recent advances and technology trends of wind turbines. Recent Adv. Renew. Energy Technol. 2021, 1, 177–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Shi, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, M.; Tang, Y.; Liu, S. Current Status and Future Trends in Installation, Operation and Maintenance of Offshore Floating Wind Turbines. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Krauland, A.K.; Permien, F.H.; Enevoldsen, P.; Jacobson, M.Z. Onshore wind energy atlas for the United States accounting for land use restrictions and wind speed thresholds. Smart Energy 2021, 3, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everaert, J.; Stienen, E.W. Impact of Wind Turbines on Birds in Zeebrugge (Belgium). In Biodiversity and Conservation in Europe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 7, pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.; Zhu, Y. The state of the art of wind energy conversion systems and technologies: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 88, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, W.; Liao, W.H.; Zhou, S. Enhanced wind energy harvesting via 2DOF vortex-induced vibration and wake-galloping interaction. Energy Convers. Manag. 2026, 347, 120533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, D.Y.; Vortex Bladeless SL. VIV Resonant Wind Generators; Vortex Bladeless SL: Ávila, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiar, S.; Khan, F.U.; Fu, H.; Hajjaj, A.Z.; Theodossiades, S. Fluid Flow-Based Vibration Energy Harvesters: A Critical Review of State-of-the-Art Technologies. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, S.; Umesh, V.; Shivakumar, S. Design and analysis of vortex bladeless wind turbine. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 5584–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Seok, J. A novel self-tuning wind energy harvester with a slidable bluff body using vortex-induced vibration. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 205, 112472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, E.; Yáñez, D.J.; Del Pozo, S.; Lagüela, S. Optimizing Bladeless Wind Turbines: Morphological Analysis and Lock-In Range Variations. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.D.; Chang, C.C.W.; Bhuiyan, M.A.S.; Nisa’Minhad, K.; Ali, K. Advancements of wind energy conversion systems for low-wind urban environments: A review. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 3406–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foisal, A.R.M.; Hong, C.; Chung, G.S. Multi-frequency electromagnetic energy harvester using a magnetic spring cantilever. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2012, 182, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Scully, B.; Shestani, J.; Zhou, Y. Design and characterization of an electromagnetic energy harvester for vehiclesuspensions. Smart Mater. Struct. 2010, 19, 045003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lee, C.; Xiang, W.; Xie, J.; He, J.H.; Kotlanka, R.K.; Low, S.P.; Feng, H. Electromagnetic energy harvesting from vibrations of multiple frequencies. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 2009, 19, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeby, S.P.; Torah, R.N.; Tudor, M.J.; Glynne-Jones, P.; O’Donnell, T.; Saha, C.R.; Roy, S. A micro electromagnetic generator for vibration energy harvesting. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 2007, 17, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kook, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.K. A novel small-scale bladeless wind turbine using vortex-induced vibration and a discrete resonance-shifting module. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yang, Y. An impact-based broadband aeroelastic energy harvester for concurrent wind and base vibration energy harvesting. Appl. Energy 2018, 212, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Song, R.; Fan, M.; Deng, J.; Xie, T. A novel method for improving the energy harvesting performance of piezoelectric flag in a uniform flow. Ferroelectrics 2016, 500, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Song, R.; Liu, B.; Xie, T. Novel energy harvesting: A macro fiber composite piezoelectric energy harvester in the water vortex. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, S763–S767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Shan, X.; Xie, T.; Chen, W. Modeling and improvement of a cymbal transducer in energy harvesting. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2010, 21, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.L.; Abdelkefi, A.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L. Orientation of bluff body for designing efficient energy harvesters from vortex-induced vibrations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 053902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Shan, X.; Upadrashta, D.; Xie, T.; Yang, Y.; Song, R. Modeling and analysis of upright piezoelectric energy harvester under aerodynamic vortex-induced vibration. Micromachines 2018, 9, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero-Gil, A.; Pindado, S.; Avila, S. Extracting energy from vortex-induced vibrations: A parametric study. Appl. Math. Model. 2012, 36, 3153–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.L.; Abdelkefi, A.; Wang, L. Theoretical modeling and nonlinear analysis of piezoelectric energy harvesting from vortex-induced vibrations. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2014, 25, 1861–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, M.; de Langre, E.; Biolley, F. Coupling of structure and wake oscillators in vortex-induced vibrations. J. Fluids Struct. 2004, 19, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Luo, L.; Yurchenko, D.; Hu, G. Equivalent circuit analysis of a nonlinear vortex-induced vibration piezoelectric energy harvester using synchronized switch technique. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 72, 4865–4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Gao, F.P. Wall-Proximity Effects on Strouhal Number for the Circular Cylinder in a Shear Flow. In Proceedings of the ISOPE International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, Cupertino, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2021; p. ISOPE-I-21-3217. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Sang, Y.; Lv, Z.; Wu, K.; Lai, Z. Dynamic response analysis of wind turbine tower with high aspect ratio: Wind tunnel tests and CFD simulation. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 211, 113113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Part | Parameter | Description | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foam cylinder | Length | 160 mm | |

| Diameter | 50 mm | ||

| Density | 55 kg/m3 | ||

| Cantilever substrate | Length | 55 mm | |

| Width | 42 mm | ||

| Thickness | 0.6 mm | ||

| Density | 2700 kg/m3 | ||

| Young’s modulus | 69 GPa | ||

| Piezo layers | Length | 51 mm | |

| Width | 38 mm | ||

| Thickness | 0.2 mm | ||

| Density | 7650 kg/m3 | ||

| Young’s modulus | 87 GPa | ||

| Dielectric constant | 1050 | ||

| Electromechanical coupling coefficient | 9.85 C/m2 |

| Value | Experiment | Simulation | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural frequency | 15.93 Hz | 16.15 Hz | 1.4% |

| Damping ratio | 0.0049 | 0.0049 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bae, J.; Simanjuntak, A.P.; Lee, J.Y. Optimal Design Guidelines for Efficient Energy Harvesting in Piezoelectric Bladeless Wind Turbines. Energies 2026, 19, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010025

Bae J, Simanjuntak AP, Lee JY. Optimal Design Guidelines for Efficient Energy Harvesting in Piezoelectric Bladeless Wind Turbines. Energies. 2026; 19(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleBae, Joohan, Armanto Pardamean Simanjuntak, and Jae Young Lee. 2026. "Optimal Design Guidelines for Efficient Energy Harvesting in Piezoelectric Bladeless Wind Turbines" Energies 19, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010025

APA StyleBae, J., Simanjuntak, A. P., & Lee, J. Y. (2026). Optimal Design Guidelines for Efficient Energy Harvesting in Piezoelectric Bladeless Wind Turbines. Energies, 19(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010025