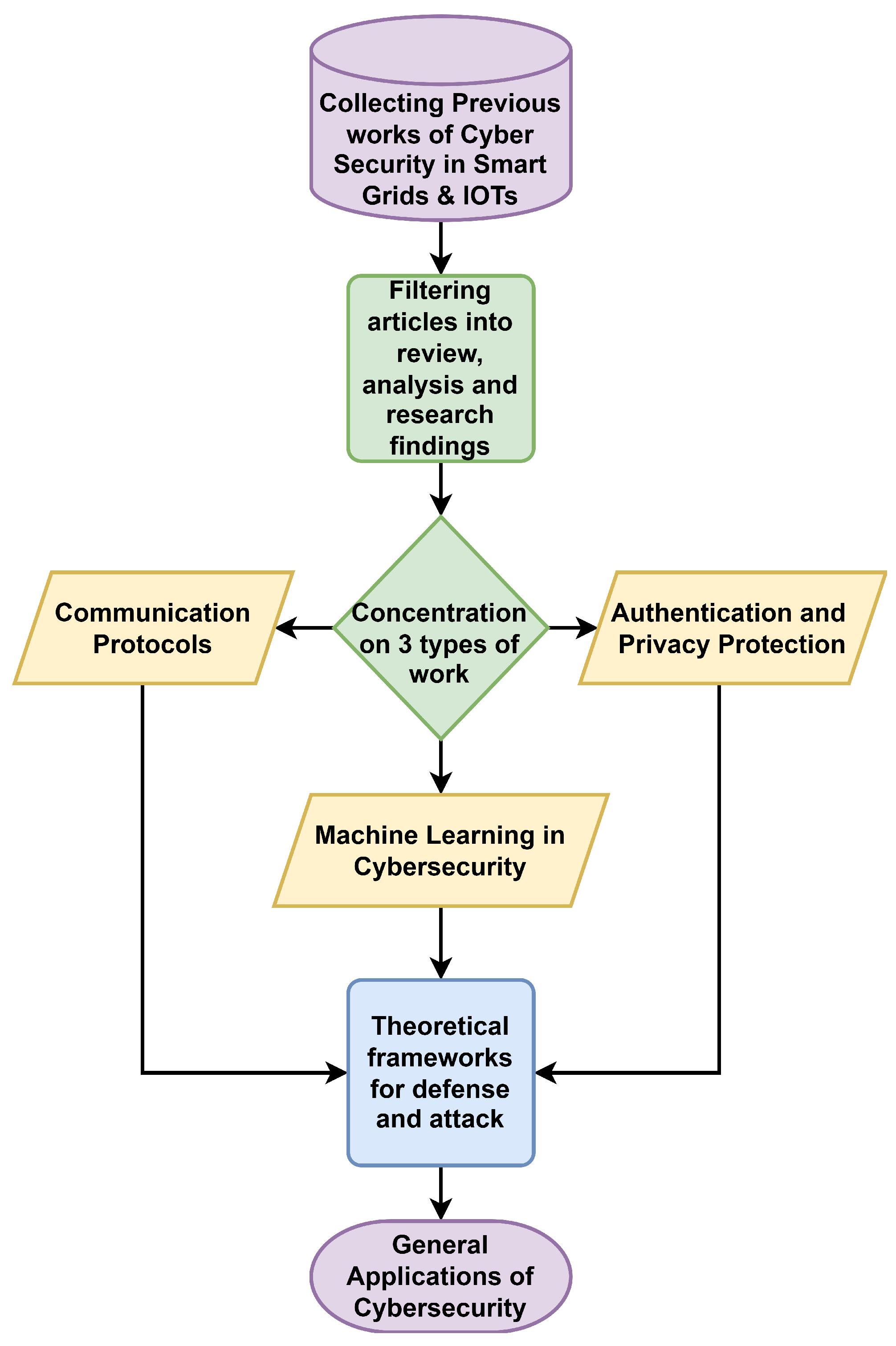

3. Review, Analysis and Research Findings

This section summarizes research, scientific papers, review articles, and analyses of the most critical problems and solutions discussed in the field of CS in smart network (SN). In addition, other networks will be reviewed to benefit from them in collecting the most significant possible amount of appropriate content within this field [

14,

15,

16].

A critical challenge in SG CS is the prioritization of limited defense resources against a vast landscape of potential threats. To provide a clear framework for readers and practitioners, a taxonomy for threat prioritization based on two key risk factors were proposed: Potential Impact (on grid safety, reliability, and stability) and Likelihood (the ease with which an attack can be successfully executed). This matrix, presented in

Table 1, synthesizes findings from the reviewed literature to categorize common attack vectors and guide mitigation strategies. High-priority threats, such as FDI and coordinated DoS attacks, demand immediate and robust defensive measures due to their catastrophic potential and relatively higher probability.

The taxonomy presented in

Table 1 is designed to synthesize findings from the reviewed literature into a practical framework for prioritizing cyber threats. The rankings for Potential Impact and Likelihood (Ease of Exploit) are based on a qualitative analysis of attack consequences and prerequisites, derived from consensus views in the academic and industry sources cited throughout this review. The scales are defined as follows:

These criteria allow for a reasoned distinction between threat levels. For example, an FDI attack on state estimation is rated Catastrophic/Medium because its impact is potentially immense, but its execution requires specific topological knowledge, making it less likely than a simple DoS attack. This methodology provides a transparent basis for the prioritization that follows.

Various attempts and incidents in past years have implicated phase measurement units (PMU) [

17], digital fault recorders, intelligent electronic devices, supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA), cyber communications components, and advanced measurement infrastructure (AMI), all of them are vulnerable to CAs. They must be protected against hacks and CAs.

Rajaa Vikhram Yohanandhan et al. [

18] studied Cyber Physical Power System (CPPS) networks and found that their heterogeneous nature necessitated conducting multidisciplinary tests to evaluate new CAs and discover vulnerabilities and threats to CPPS. Using this CPPS testing framework, it can detect different types of CAs and evaluate the detection algorithm used, which in turn helps develop sustainable CS defenses for the CPPS environment. They reviewed the CPPS test layers from different angles, such as the physical PS layer, communication layer, sensor layer, application layer, control layer, test platforms, and research objectives with the integration of cyber and physical systems. They also reviewed the physical power infrastructure of CPPS, CPPS protocols, communications networks in CPPS, Cloud Computing (CC) and data analytics, software tools for modeling and simulation of CPPS, CAs in CPPS, failure cascade analysis of CPPS, CS and privacy in CPPS, and resilience and reliability analysis of CPPS. They provided an overview of CPPS networks, architecture, assessment, and description of the necessity of CA testing and sustainable CS analysis in CPPS [

19].

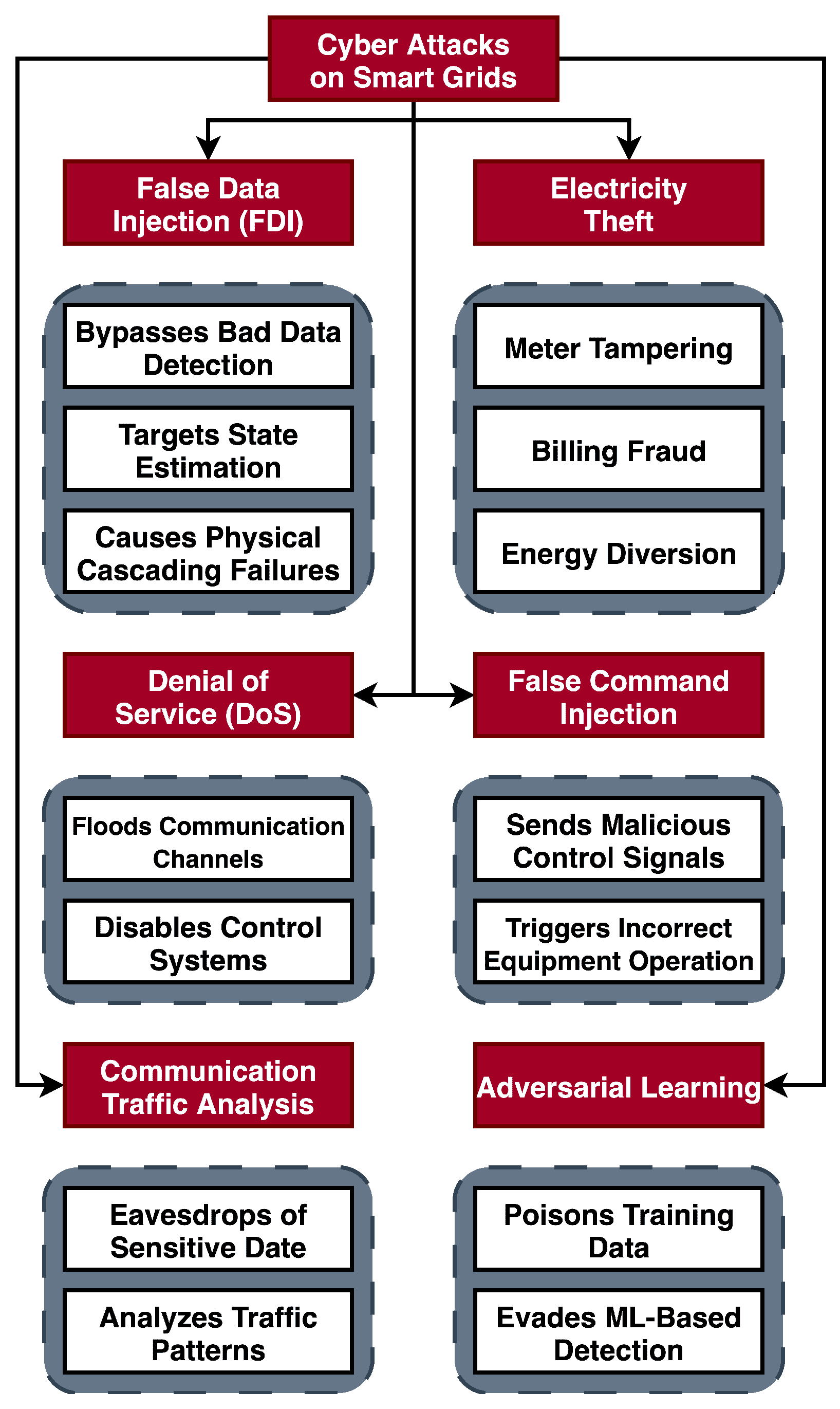

Figure 2 gives a quick overview of the classifications of cyber attacks in smart grids.

Based on the analysis of ubiquitous electric IoT network development trends and technical requirements, another work proposes smart meters (SMs) and suitable acquisitions of SG information acquisition systems in addition to a lightweight two-way device authentication protocol [

20]. The protocol is based on two main elements: a shared security key and random numbers to verify the identity of both parties to the communication. They proposed using the security key embedded in the device chip to determine the legitimacy of the identity of the access device, avoiding the use of third-party services such as certificates, and effectively preventing frequent man-in-the-middle attacks. Some experiments have shown that the time for lightweight XOR data decryption is 1/2 the time of a typical Data Encryption Standard (DES) algorithm and 1/900 the time of an Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA) algorithm. The obtained efficiency was much better than DES and RSA, which is consistent with industrial control systems (ICSs). They collected possible general incident patterns and worked out CA classifications and application scenarios for ubiquitous energy IoT network attacks.

In [

21,

22], the performance effects of False Data Injection (FDI) attacks on cascading failures of a CPPS were studied through a set of steps: First, the power flow characteristics of the power network and the monitoring and control functions of the cyber network were taken into account. Second, a proposed model of the energy CPS was created. Third, the false data attack (FDA) and its impact on decision-making processes and control of communications operations in the cyber network were studied. Fourth, a successive failure analysis process for the CA environment was proposed. Fifth, an indicator was proposed to evaluate the network’s vulnerability from two perspectives, the first of which is the operating characteristics of the power network and the second of which is the structure’s integrity.

A dynamic Bayesian game-theoretic approach is proposed to analyze FDI attacks with incomplete information [

23]. In this approach, according to a proposed bi-level optimization model, players’ payoffs are identified, and based on history profiles and relationships between measurements, the prior belief of the attacker’s type is constantly updated. It is proven that the type belief and Bayesian Nash equilibrium (NE) are convergent. By the law of large numbers and the central limit theorem, the stability and reliability of this approach can be guaranteed. By using the dynamic Bayesian game-theoretic approach, the defender can efficiently allocate resources to at-risk load measurements [

24].

Jinsoo Shin et al. [

25] investigated safety and security perspectives when conducting risk analysis for nuclear facilities by adopting the System-Theoretic Process Analysis (STPA)-SafeSec methodology to know the impacts on safety through CAs against digital information and control systems. They applied this methodology to a test bed system that simulates a condensing water system in a nuclear power plant (NPP). They described the development of mitigation strategies and the implementation process in detail.

A. Vaccaro et al. [

26] analyzed the enabling methodologies related to SG computing, monitoring, and control. Accordingly, they proposed research into designing more flexible and scalable solution models based on decentralized, comprehensive, proactive, and self-organizing computing. This, in turn, is reflected in strengthening the procedures for operating sensor networks (SNs) and developing their work with a set of information services that help discover knowledge and extract data.

In [

27], all the standards required by CS that were actually applied to SNs were collected and identified. Based on these reviews, seventeen criteria were described and identified. Additionally, focus was placed on SC requirements and related evaluation criteria [

28]. The relationships between the standards were also analyzed and studied to identify points of overlap in the standards and points of independence.

A valuable review of SGs considering wireless communications technologies (WCTs) comprehensively reviewed [

29,

30]. Different network attributes were studied to compare communication technologies in the context of an SG, such as Internet Protocol support, power usage, data rate, etc. taken into consideration. They also discussed some technologies, such as 6LoWPAN, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, ZigBee, and Z-Wave, which are suitable for Home Area Networks (HANs). They then compared these technologies in the context of network characteristics and consumer interests. Also, in the context of public utility concerns for WCTs for Neighborhood Area Networks (NANs), a similar approach was adopted, including cellular standards based on GSM and Worldwide Interoperability for Microwave Access (WiMAX).

In another work [

31], they addressed and analyzed the problem of FDI attack, where they found that this attack can bypass bad data detection mechanisms in estimating the state of the power system (PS). They worked to distinguish between the attack and normal patterns to propose an unsupervised method.

Sandeep Pirbhulal et al. [

32] conducted a study aimed at conducting a comprehensive systematic literature review on the subject of developing techniques, protocols, methodologies, RAMS analysis tools, and models for various applications. They collected 1513 records that were published between 2011 and 2020. A comparative analysis of existing solutions has been done based on various aspects such as developed methodologies and architectures, targeted applications, implementation scenarios, performance evaluation mechanisms, protection aspects of applied Critical Infrastructures (CIs) associated with RAMS, and pros and cons. They show that RAMS analysis of CIs with applications such as CC, PG stations, maritime transportation, CPSs, and ICSs is an emerging research area.

In [

33], the information security (IS) threats facing the Energy Internet were reviewed. Then, the flaws in these networks were classified, and ways to protect the security of information related to power plants were studied. According to the network security characteristics, the research also studied the system architecture of the distributed power station in the energy Internet environment, analyzed the counter-protection measures to protect the IS of such stations, and worked to build a network security framework for these stations and to analyze and provide the IS of the distributed power station [

34].

In [

35], a hybrid framework based on a physical model was proposed to estimate non-technical power losses in distribution networks. Non-technical energy loss is defined as energy received by the consumer but not invoiced. Contemporary solutions to this issue typically utilize either data-driven approaches or physical models. However, data-based solutions alone have proven inadequate, necessitating the adoption of analytical solutions grounded in physical models.

Engineering assessments and expert judgments are among the methods for assessing cyber risks [

36]. One of the difficulties facing these assessment methods is that no database is available for NPPs containing potential CTs. Therefore, they adopted operational experience analysis to estimate the frequencies of CTs. First, they grouped running experiments according to their characteristics to propose a list of CTs. Second, through Bayesian updates, the frequency of each CT is calculated in two stages.

Mohab Aly et al. [

37] presented an interesting article on understanding IoT security issues. They comprehensively described the security challenges and threats facing networks across the different layers of the IoT systems architecture [

38]. They then presented countermeasures and proposed solutions to these security challenges and threats.

Refs. [

39,

40] presented another method for assessing SC risks, which includes new communications concepts, information technology, and old systems. Two paths of analysis can be used to identify risks associated with the architectural concept of the SG. The first is an analysis at the conceptual level that attempts to understand the risks to which SG components cannot be implemented. The second is an implementation-level analysis that works on current prototypes and legacy systems and shows their role in the candidate SG architecture.

In [

41], a comprehensive review of the most significant research works in SNs, focusing on IoT applications, was conducted. The review highlighted numerous innovative methods in SNs and the IoT and discussed their applications across various fields.

In [

42], the role of sonification and its usefulness in a network traffic sonification system to represent network attacks was analyzed and evaluated. In this system, data was represented as sound. Accordingly, network security information and network attacks were converted into audio signals. The results showed that participants could accurately and efficiently detect attacks by listening to audio network data and could even identify types of attacks.

In [

43], classification and identification of weak and critical links of traffic networks, two new methodologies based on the Fisher information matrix, eigenvectors and eigenvalue analysis, were presented to identify and classify weak and critical links of traffic networks. Traffic variables, such as network flow and travel time, are used to identify.

In [

44], an analytical formula was presented to evaluate system reliability in SGs based on the availability of the central remote control system and the impact of the weakness of the CPS. It is expected that the protection system will be developed towards the use of remotely controlled circuit breakers, which in turn will help overcome this weakness and move towards a CPS that works according to protection schemes based on remote-controlled switches.

In [

45], a comprehensive summary of CAs targeting ICSs and approximately forty-three attacks that caused severe damage to critical national infrastructure was provided. They documented previous ICS-focused CAs, analyzed them, and documented their evolution to understand better the threat actors, attack vectors, and targeted sites and sectors. A reliability assessment technique for CPPSs in the field of SC was presented in [

46]. The technique is based on analyzing non-normal random variables with non-linear dependencies. Bidirectional Encryption Representations from Adapters were used to analyze their textual description and predict the severity of cyber vulnerabilities. This model allows manual text entry describing threats to predict the probability of cyber vulnerability. A Bayesian attack graph was used to simulate attack paths. A Markov model was used to explain the consequences of CAs.

In other analytical research, they analyzed and evaluated the SC risks associated with aggregating distributed energy resources (DER) or an edge device and developed an approach that limits or mitigates these risks [

47]. In [

48], a method for monitoring a connected network’s managed security measure, the Seamless Security Application Method, was presented. The advantage includes the lifespan of managed security measures by checking and exploiting vulnerability levels. The case-based analysis process adapts Q-learning to identify and update the case and work on the necessary security measures. This procedure provides continuous support for operating applications and reduces premature termination of the security procedure, which reflects positively on the efficient exploitation of sustainable energy resources.

In [

49], a comprehensive solar Photovoltaic (PV) technology comparison of four decision tree (DT) algorithms for static security evaluation and classification was performed using the C4.5 approach. A four-step process was proposed to build a binary classifier: selecting the best classifier and evaluating performance, data collection, technique comparison, pre-processing, and feature selection. The study was applied to five (5) photovoltaic power generators producing a total power of 40 MW on the IEEE 30 bus system.

In [

50] discusses criteria for evaluating SG SC. The results of the systematic analysis were presented by identifying criteria that provide sound guidance for a security assessment to solve the problem of the presence of many criteria and the inability to combine them. This study showed that there are six criteria for SG or energy systems that provide security assessment and can be applied to substations, IACS, or all SG components.

The hostile goals of attackers: firmware modification attacks through which attackers attempt to switch and control input modification attacks targeting the microgrid (MG) system using inverter-based distributed generation (DG) were analyzed [

51]. The use of hardware performance counters with time series classifiers has been proposed.

In [

52], a framework was proposed to model the SG as complex interconnected networks, and then the structural weaknesses that could be vulnerable to attacks were investigated. These attacks are considered a severe electronic, physical threat. One type of FDI attack is a load redistribution attack (LRA). A new approach was presented to identify cascade attack targets based on the intelligent attack mechanism and the node’s importance, as the attack can lead to the collapse of the entire PS [

53]. The effectiveness of the proposed strategy was verified on the IEEE 39 bus and the actual district core network.

In [

54], a bibliometric survey of research papers on the security aspects of SGs supported by the IoT was presented. This survey concludes that SG systems’ complexity and threats’ diversity call for intelligent and comprehensive security approaches. The survey also expects future publications to focus on increasing the computational speed of security algorithms with a low rate of false alarms and maintaining high detection accuracy. The survey also revealed a research gap: most research papers focus on detecting CTs and how to prevent them. However, few focus on mitigating the CTs that affect SGs.

Ref. [

55] presented a comprehensive review of vulnerabilities identified in distribution substations, particularly from the attacker’s perspective. It delineated the vulnerabilities that potential attackers could exploit and subsequently discussed countermeasures against these CAs. The key elements necessary for a comprehensive SC solution for electrical substations were also identified.

The modern SG is evolving beyond a traditional, centralized grid into a complex Cyber-Physical System (CPS) that deeply integrates Distributed Energy Resources (DERs), Electric Vehicles (EVs) and their charging infrastructure, and smart buildings. While this integration enhances flexibility and sustainability, it profoundly reshapes the cybersecurity landscape by dramatically expanding the attack surface and introducing novel vulnerability vectors [

56].

Expanded Attack Surface through Interdependencies: The interconnection of previously isolated systems creates a web of cyber-physical interdependencies. For instance, an attacker compromising a cloud-based platform managing a fleet of DERs can inject false data to cause local voltage violations or frequency instability [

56]. Similarly, EV charging stations, particularly public and residential “smart” chargers, represent a massive and often poorly secured entry point. A coordinated attack on a fleet of EVs (a “Demand-Response Attack”) could be orchestrated to simultaneously start drawing high power, creating a significant, sudden load on the distribution grid that could trigger instability or even blackouts [

57]. The compromise of one system component (e.g., an EV telematics unit) can thus serve as a pivot point to attack the broader energy infrastructure.

New Vulnerabilities from Bidirectional Data Flows: Integration is enabled by continuous, bidirectional data exchange. Unlike traditional one-way meter reading, integrated systems rely on two-way communication for functions like vehicle-to-grid (V2G) services, where EVs feed power back to the grid. This creates new attack vectors. For example, False Data Injection (FDI) attacks can manipulate pricing signals or control commands sent to DERs and EVs, leading to inefficient energy dispatch, financial fraud, or physical damage. Furthermore, the privacy risks are magnified; detailed consumption data from EVs and smart inverters can reveal sensitive information about user behavior and occupancy patterns.

Zhang et al. [

57] further elaborate on the cyber vulnerabilities of EV battery chargers, discussing both attack impacts and latest hardware/software-based detection techniques. Securing this integrated ecosystem requires a holistic approach that moves beyond protecting the core grid to encompass the entire supply chain of connected devices and the communication protocols that bind them together.

4. Authentication Methods and Privacy Protection

In this section, there will be a brief review of the works and research that dealt with the topics of authentication approaches and privacy protection in protection systems in general and SC in particular, with their applications in SNs and others.

Table 2 summarizes authentication approaches and privacies, the table also includes methods involving secure key management (KM), blockchain (BC)-based solutions, lightweight authentication protocols, intrusion detection, and privacy-preserving mechanisms applied in various domains such as healthcare, CC, and smart homes (SHs). Each entry summarizes the major contribution, output, and year of publication, offering a broad insight into the latest trends and solutions in the field. Zhitao Guan et al. proposed a solution to the problem of trading based on BC technology, as most face the problem of privacy disclosure [

58]. They proposed ciphertext Policy Attribute-Based Encryption as the basic algorithm for reconstructing the transaction model. This idea works by building a public model for distributed transactions called PP-BCETS (Privacy Preserving BC Energy Trading System). Arbitrating transactions in the ciphertext form can achieve fine-grained access control. In this way, the protection of private information can be increased, and the reliability and security of the transaction model can be greatly improved.

In another work, an SC-assisted authentication method for SGs is proposed to overcome the flow of false data [

59]. This method relies on estimating the energy requirements of the meters in advance based on information obtained previously. Then, according to these previously provided parameters of the distribution method or rated power requirement, authentication-based security is provided. At the same time, the monitoring process continues for differences in SG data to allocate power based on the network and end-user consumption at the current time of connection. Thus, power distribution is enhanced without stagnation or overload. In [

60] examined the issue of application layer protocols for the IoT, as these protocols are considered by their nature not equipped with sufficient security guarantees, such as the Message Queue Telemetry Transport Protocol and the Constrained Applications Protocol [

61]. Then, they proposed a solution suitable for critical IoT-based applications: a three-factor authentication framework based on a digital signature, identity, and password system. This framework takes advantage of Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) and computationally low hash chains because it uses the publish-subscribe pattern. The results have proven that this framework resists different types of cryptographic attacks. They used the Scyther tool to perform automated verification of any of these requirements to ensure no cryptographic attacks in the proposed framework on any of the mentioned claims. For further discussion on ECC-based communication protocols, please refer to Section of Communication Protocols.

Table 2.

Cyber security in the Smart Grid: Authentication.

Table 2.

Cyber security in the Smart Grid: Authentication.

| Work Area | Summary | Ref. | Year |

|---|

| Smart PGs Capabilities | Critical SG challenges surveyed | [30] | 2016 |

| CPS Security | Risk assessment, Physical Unclonable Function (PUF) role | [14] | 2017 |

| Fog-based SCADA | IDS classification, privacy/authentication review | [62] | 2020 |

| Device Authentication Protocols | Lightweight mutual authentication using keys | [20] | 2020 |

| User Authentication | Authentication based on energy need; improves false data detection | [59] | 2021 |

| ECC-based Framework | 3-factor Authentication using identity, password, and digital signature | [60] | 2022 |

| ITS Privacy | PC switching using CPC improves pseudonym changes | [63] | 2023 |

| SG Key Services | Smart scheduling, attack surface control with executor mgmt | [64] | 2021 |

| Anonymity in Authentication | Group blind signature and HE for integrity | [65] | 2020 |

| ECC Mutual Authentication | Lightweight ECC system with session key phase | [66] | 2021 |

| Key Agreement | Anonymous, lightweight AK protocol for DR | [67] | 2021 |

| BC Keyless Sig. | Decentralized keyless sig. via BC, secure access control | [68] | 2019 |

| Fission Computing | Trust/privacy via edge-crowd model | [69] | 2019 |

| EPPS in AMI | FDIA resistance via GMM and MSE-based learning | [70] | 2021 |

| ICS Networks | Steady-state CPS correction under attacks | [71] | 2021 |

| Security Frameworks | SMG in MICIE & CockpitCI bridges CS and control theories | [72] | 2018 |

| Hybrid MGs | Modified SCA + BC for AC-DC trading | [73] | 2021 |

| Authentication in SG Net. | Lightweight AK protocol, no key escrow, random oracle-secured | [74] | 2021 |

| RFID Security | Lightweight RFID Authentication for IoT, ensures secrecy | [75] | 2018 |

| IoT + Cloud Authentication | Lightweight cloud-Authentication for IoT with minimal overhead | [76] | 2019 |

| FDI Protection | MILP model for blackout-aimed cyberattack detection | [77] | 2021 |

| Bidirectional DB | Enhances query speed and reduces attack vector | [78] | 2018 |

| SCADA Vulns | Access control model derivation method | [79] | 2021 |

| IoT-Wireless Authentication | Secure AK protocol for WSNs; improves smart card handling | [80] | 2019 |

| W3C-Prov Authentication | Standardized model unifies all Authentication factors | [81] | 2017 |

| IEC 62351 Fix | Secure protocol using hash + key; avoids GOOSE/SV issues | [82] | 2020 |

| Cloud Authentication | Improved cloud-SM Authentication via TA | [83] | 2020 |

| IoT Smart Cities | Trusted sensing model using digital certificates | [84] | 2023 |

| DRN-KeyGen | DL-based Authentication for LTE IoT; re-Authentication with low overhead | [85] | 2024 |

| BC IoT Authentication | BlendCAC for smart contract-based access control | [86] | 2023 |

| RFID-SAM | SAM protocol boosts tag-read Authentication | [87] | 2020 |

| Gesture Authentication | Gesture typing on mobile; superior features | [88] | 2019 |

| Authentication Techniques Review | Review of total Authentication methods (SFA & MFA) | [89] | 2018 |

| BC SH | BC + fog solves cross-domain Authentication | [90] | 2024 |

| Healthcare IoT | LMDS-based secure medical IoT Authentication | [91] | 2021 |

| Activity-Based Authentication | User Authentication via activity sensor patterns | [92] | 2018 |

| Roaming Authentication | Lightweight Authentication with session keys | [93] | 2024 |

| IoD Security | Lightweight protocol using dynamic IDs | [94] | 2023 |

| Fog-IoT Authentication | Multi-factor scheme using BC + light-chain | [95] | 2024 |

| Mag-PUFs | Electromagnetic Authentication with MAG-PUFs | [96] | 2024 |

| PUF in Med-IoT | GIFT-COFB + PUF for secure SHS | [97] | 2024 |

| LoRaWAN | MAB-based resource allocation | [98] | 2024 |

| Post-Quantum Authentication | Post-quantum secure Authentication for cloud health apps | [99] | 2024 |

| Vehicular Cloud | A3C+Dropout model for delay/energy reduction | [100] | 2024 |

In [

63], they examined the issue of data transfer in cooperative intelligent transportation systems, where users’ privacy must be protected, especially when their locations are hidden, and every message must be authenticated. Authentication is done by signing messages with a private key associated with a pseudonym certificate provided by a trusted authority (TA). For the recipients to authenticate the messages, a computer is delivered with the messages, and to ensure privacy and protection from trackers from obtaining information regarding the drivers’ locations, for example, computers are changed several times during the trip. So, in this work, they proposed a new method to manage computer switching intervals between vehicles. The method relies on having a shared computer as an intermediary before switching to a new computer. So that all vehicles use this shared computer to sign their messages during this period. Other work examined the topic of edge computing and the security and risks it can bring to the SG [

64]. They proposed a heterogeneous polymorphic security architecture (SA) for edge-enabled networks. The proposed architecture provides intelligent executor scheduling based on dynamic heterogeneous redundancy architecture, attack surface management, executor cleaning and rebuilding, and intelligent arbitration of multi-instance service response.

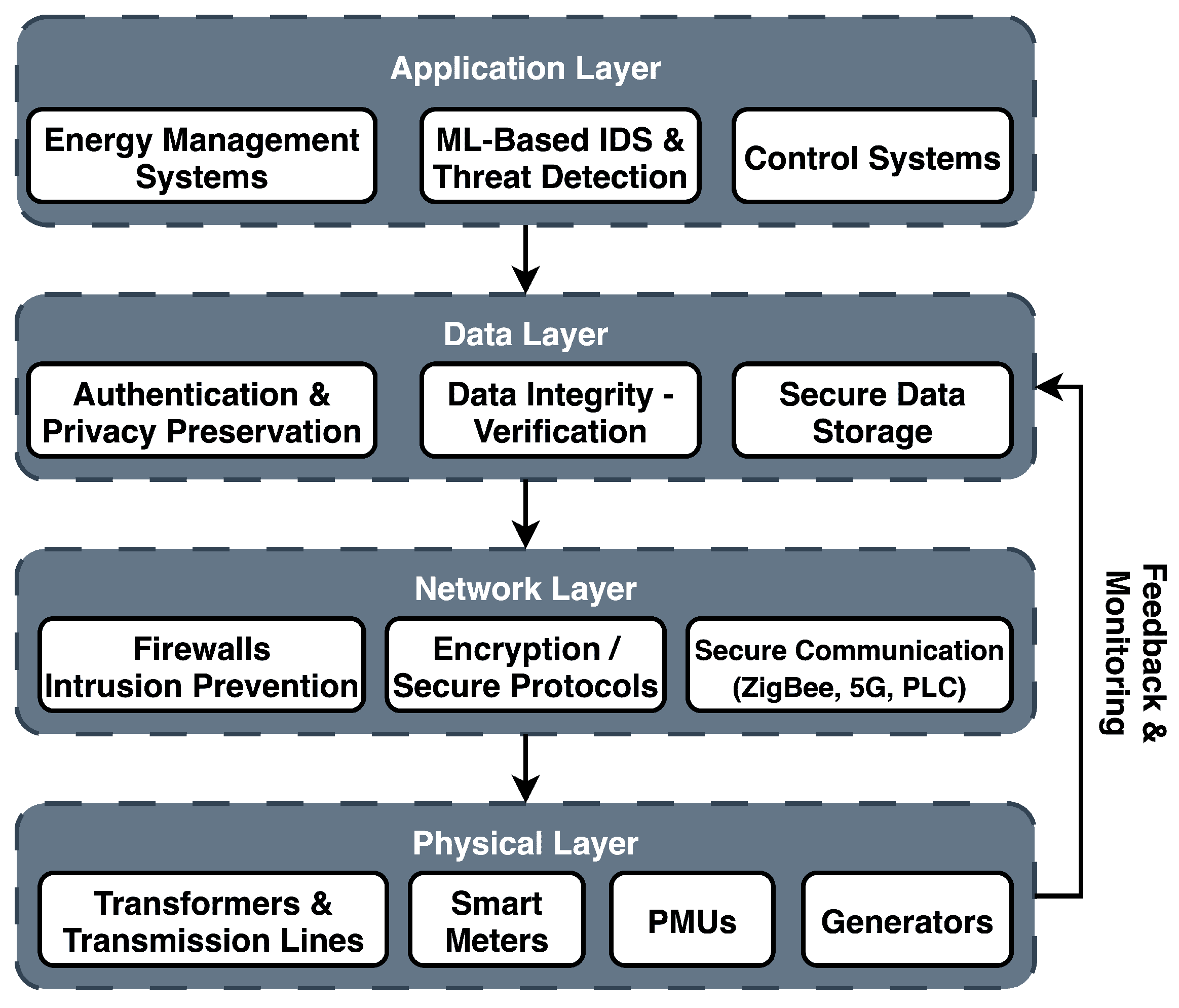

Figure 3 shows the layered security architecture for SG CS. To decide, modify, process, schedule, migrate, clean up, rebuild, and recover, they created a closed-loop core control process. To solve the problem of unidentifying the malicious user in the case of anonymous authentication (AA) and to achieve conditional anonymity, a collective blind signature system in the SG is proposed in [

65]. It takes place in four stages: First After the CC creates the system parameters, the SMs and Security Servers (SSs) finish the registration. Second: Using the Schnorr ID, the SMs authenticate anonymously with the SSs, and with the SMs to verify the integrity of the data, homogeneous tags are created. Third, A blind signature of the group is generated by the SS for the data from the authenticated SM. Fourth, The integrity of the data and the validity of the signature are verified by CC. Threats facing the SG include CTs to send messages, network control, and information, and the possibility of harming consumers’ privacy in the SG environment were studied in [

66]. One of the solutions provided for these threats is to establish a secure connection between the consumer and the service provider (SP) and perform Mutual Authentication (MA) between them. In another work, a MA scheme was proposed based on elliptic curve encryption of substations and consumers with simple operations for a SG environment to protect them from STs. One of its advantages is that it provides a significant negotiation phase for the session, reflecting positively on providing a secure connection and reducing communication costs.

Also, a trusted and secure key agreement system is crucial in SNs, and various studies have been done in this regard [

67]. In this work, a protocol is proposed to address the limitations and drawbacks of a previously proposed protocol. The proposed protocol is a lightweight, anonymous, authenticated key agreement for intelligent network-based demand response management. Its features are that it supports privacy, withstands various security attacks, and supports MA. The proposed protocol was tested using automated ProVerif simulation and Burrows Abadi Needham logic analysis. KM between SPs and SMs is crucial in SGs [

68]. This is done by trusted third parties but becomes insecure if the Trusted Third Party (TTP) fails. Since the providers of these services are centralized, there is a single point of failure. This paper proposed a decentralized keyless signing scheme based on BC consortium to achieve more secure and efficient KM. Using the BC network for data transfers, the SM sends requests and receives responses. A secure, decentralized consensus mechanism is designed to turn the BC into an automated manager that does not require a TTP or trust anchor, which controls access. SPs can also monitor each other using BC according to the proposed model. In a similar area, trust and privacy in Social IoT are essential for operating and exchanging information with edge devices [

69]. Current solutions rely on a single central server and a trust scoring system. These registration systems are vulnerable to tampering. So, this work proposes a new approach in the form of fission computing. The proposed approach relies on edge integration with the crowd to maintain privacy rules in S-IoT and maintain trust. This is done by modeling entropy to determine trust between entities and using crowdsourcing as mini-edge servers. Fission Managers are responsible for maintaining the privacy rules for each S-IoT application. Another work proposed an “End User Privacy Protection System” [

70]. The system enables SMs to report the correct reading during an False Data Injection Attack (FDIA) [

101,

102]. In this proposed technique, the actual measurement secret interval against FDI and data protection capability are evaluated based on the statistical ML method by clustering mean square error and Gaussian mixture models (GMMs). In [

71], the control transformation strategy for the physical information network was analyzed and studied in light of the dynamic data attack (DA) in the ICS. A relevant mathematical model of CPSs was created for analysis to stabilize the CPS. An innovative algorithm has also been proposed to correct the steady state of CPSs to achieve good control performance under the dynamics of DAs. This is done by successfully transforming the problem of system stability into the problem of control strategy flexibility.

In Industrial Control and Automation Systems, other research has examined security challenges that require evaluating security strategies and new risk assessment [

72]. To respond to threats promptly and manage vulnerabilities properly, a security framework and advanced tools have been proposed. This strategy has been implemented in the ATENA architecture, designed as an innovative solution for protecting critical assets. An initial version of the secure brokerage gateway was designed in the Mission Critical Information Infrastructure Protection (MICIE) project and optimized in the CockpitCI framework. Even in grid-connected hybrid AC-DC MG systems, the systems also need to achieve safety and reliability since any changes in them can affect the power management of the entire system. So, in further research for power management of the entire system, the modified sine cosine algorithm was developed [

73]. In addition, BC technology has been used to increase the security of energy trading within these hybrid MGs connected to the AC-DC grid. Random convection flow, based on copula mode, was used to create a realistic model. An SG key agreement protocol and a lightweight AA key for SG communications are proposed [

74]. A security analysis was presented based on the random oracle model, which proved the security of the proposed protocol. The security of the proposed protocol was verified using a tool from the AVISPA program. Some security features of this proposed protocol have been proven, such as message authentication, replay attacks, SP anonymity, man-in-the-middle attacks, anonymity, impersonation attacks, key freshness, session key agreement, and non-traceability; in addition, communication and accounting costs are much lower. In RFID-based authentication systems, many authentication systems are designed using lightweight cryptographic tools [

75]. Many of these designs fail to meet the required safety and functionality requirements. Another research has presented an authentication architecture for RFID-based IoT applications for future smart city (SC) environments. Then, a lightweight authentication scheme was introduced to provide a more reasonable implementation time than existing schemes based on RFID. This system features forward secrecy, RFID tag untraceability, anonymity, and secure translation. A new authentication scheme is proposed for IoT-enabled device-based environments combined with cloud servers [

76]. They adopted lightweight encryption modules to achieve the best efficiency. Examples of cryptographic modules that have been adopted include one-way and exclusive hash functions or run. The advantage of this proposed system is that it is suitable for resource-limited environments, such as IoT devices or sensors, and one of its advantages is that it removes the computation burden. Proverif has verified its effectiveness. To confront CAs that cause power outages in large-scale networks and target bypassing multiple transmission lines, a bi-level mixed integer linear programming model was developed to accurately model FDIs [

77]. It has been demonstrated that an FDI attack can be detected using a detection framework based on weighted least squares (WLSs) estimation instead of classical WLS estimation.

In the context of data, it is necessary to talk about a two-way data transformation methodology with common language data representation to overcome updating problems related to data and metadata. The updated information has different data types and formats. It thus reduces the ability of devices and databases to prepare to investigate the information due to this difference and lack of similarity. A new approach was presented that allows data to be mapped and helps to understand their differences at the level of data representation [

78]. This mapping is made using Extensible Markup Language (XML)-based data structures as an intermediate data provider. Using XML, data can be converted bidirectionally from traditional data format and Resource Description Framework without data loss and with improved remote data availability. The vulnerabilities and STs of the SCADA system are discussed, with a comprehensive methodology proposing appropriate security mechanisms [

62,

79,

103]. The methodology is based on extracting the appropriate structure after defining security policies and models, identifying security needs and objectives, and implementing security mechanisms that protect against risks and meet needs. A new access control model named CI-OrBAC has been proposed. Stream Control Transmission Protocol (SCTP) was proposed as a transport protocol between the control and command planes. The Hash-Based Message Authentication Code (HMAC) field included in the ModbusSec message verifies hardware authentication and data integrity in the area between the control and command planes [

104]. An evaluation of lightweight two- or three-factor authentication protocols showed that they are weak to strong replay attacks and do not provide complete confidentiality [

80,

105]. Therefore, a key agreement protocol for wireless sensor networks (WSNs) and secure and lightweight IoT-based authentication is proposed. A simulation of the proposed protocol was performed using the AVISPA tool to verify the security. The results show that the proposed protocol is secure against active and passive attacks. Other work within this context focuses on notions of pragmatic social validation based on the nature, quality, and length of prior encounters [

81]. Using previous interactions, the basic similarity of the authentication factors is determined. Based on the W3C Provenance Working Group model, a unified representation model of secure interaction resources is presented. The paper also presents formal security proposals for defining secure interaction source schemes. A fuzzy control logic was implemented for the interaction source logs to create a new authentication and threshold-based access control model. The research also presents a protocol for registering and authenticating the interaction source and implementing the proof of concept.

Bera and Sikdar have proposed a security protocol for post-quantum communications in SG applications that ensures resilience against both classical and quantum attacks [

106]. In [

107], Gharavi et al,. have looked at the different types of PQC and their recent standard primitives to determine whether they can enable security for BC-based IoT applications. This study shows how post-quantum BCs are being developed and how it can be used to create security mechanisms for different IoT applications. And also, this study explores the main challenges and potential research directions that arise from integrating quantum-resistance BCs into IoT ecosystems. In [

108], Najet Hamdi proposes a FL-based intrusion detection for SCADA systems where clients have different attacks. The impact of having missing attacks in local datasets on the performance of FL-based classifier were classified. Also, a hybrid learning method that combines centralized and federated learning was proposed. Lazzarini et al., evaluate the use of federated learning (FL) as a method to implement intrusion detection in IoT environments. When compared against a centralized approach, results have shown that a collaborative FL IDS can be an efficient alternative, in terms of accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score, making it a viable option as an IoT IDS. Additionally, the alternative aggregation algorithms, namely FedAvgM, FedAdam and FedAdagrad were evaluated in same settings. The results show that the FedAvg and FedAvgM tend to perform better compared to the two adaptive algorithms, FedAdam and FedAdagrad [

109]. Alqahtani and Kumar comprehensively explores cybersecurity challenges, including cyber-physical threats, privacy vulnerabilities, and supply chain risks and investigates artificial intelligence (AI)-driven solutions to bolster EnFV cybersecurity. The study begins with an overview of EnFV cybersecurity issues, emphasizing the increasing complexity of threats in digital transportation systems [

110]. Ronanki and Karneddi provide an overview of the latest research contributions regarding the evolution of battery charger architectures, control methods, EV supply equipment (EVSE), charging protocols, communication channels, and their compliance from the perspective of cyber security. Furthermore, the potential impacts of sabotage cyber-attacks on various popular battery chargers are explored. In addition, the latest hardware and software-intensive cyber-attack detection and countermeasure techniques are discussed [

111].

While blockchain technology offers a decentralized and tamper-resistant ledger ideal for applications like energy trading and access log auditing, its adoption in SGs faces significant practical barriers that are often understated. The core operational requirements of a SG frequently conflict with the inherent characteristics of many blockchain implementations.

First, the issue of high latency is paramount. Consensus mechanisms, particularly Proof-of-Work (PoW), can require several minutes to achieve transaction finality. This is incompatible with real-time grid operations such as frequency regulation, fault protection, or even rapid demand response, which require decision-making in milliseconds to seconds.

Second, the energy consumption of PoW-based blockchains is substantial, creating a paradoxical situation where securing the grid’s data transactions consumes an excessive amount of the very resource the grid manages. Although alternative consensus mechanisms like Proof-of-Stake (PoS) are more energy-efficient, they often introduce other trade-offs like potential for centralization.

Finally, scalability limitations present a major hurdle. Throughput in large, permissionless blockchains is typically limited to tens of transactions per second, while a fully deployed AMI with millions of SMs can generate a continuous, high-frequency stream of data points. Storing every meter reading on-chain is currently impractical and prohibitively expensive.

Therefore, blockchain is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Its application is best suited for non-real-time, high-value transactions where decentralization and auditability are critical, such as settling financial energy trades between utilities, managing renewable energy certificates (RECs), or maintaining tamper-proof logs of critical configuration changes. For real-time control and massive data collection, hybrid architectures or alternative technologies are more appropriate.

While the surveyed authentication schemes show significant promise, several challenges remain for widespread SG deployment. Lightweight cryptographic protocols often face a trade-off between security and functionality, sometimes sacrificing perfect forward secrecy for reduced computational overhead. Blockchain-based solutions, as discussed in this Section, difficulties with scalability and latency. Furthermore, many proposed schemes are validated in isolated testbeds and lack evaluation under real-world SG constraints, such as network congestion during fault conditions or the presence of legacy devices that cannot be easily upgraded. A key unresolved issue is the development of agile authentication frameworks that can dynamically adapt their security parameters based on real-time threat levels without disrupting grid operations.

5. Communication Protocols

This section provides a review of research publications that focus on communication systems in SNs. It includes reviews of the most notable systems employed and an analysis of their advantages, disadvantages, and the issues they encounter.

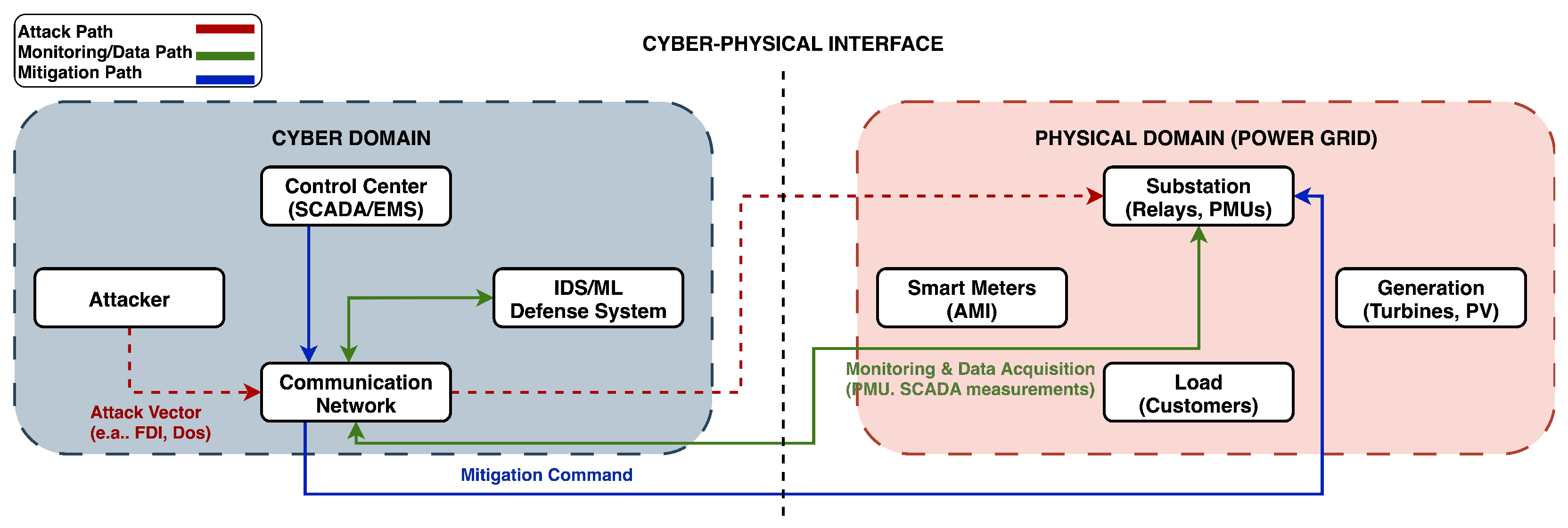

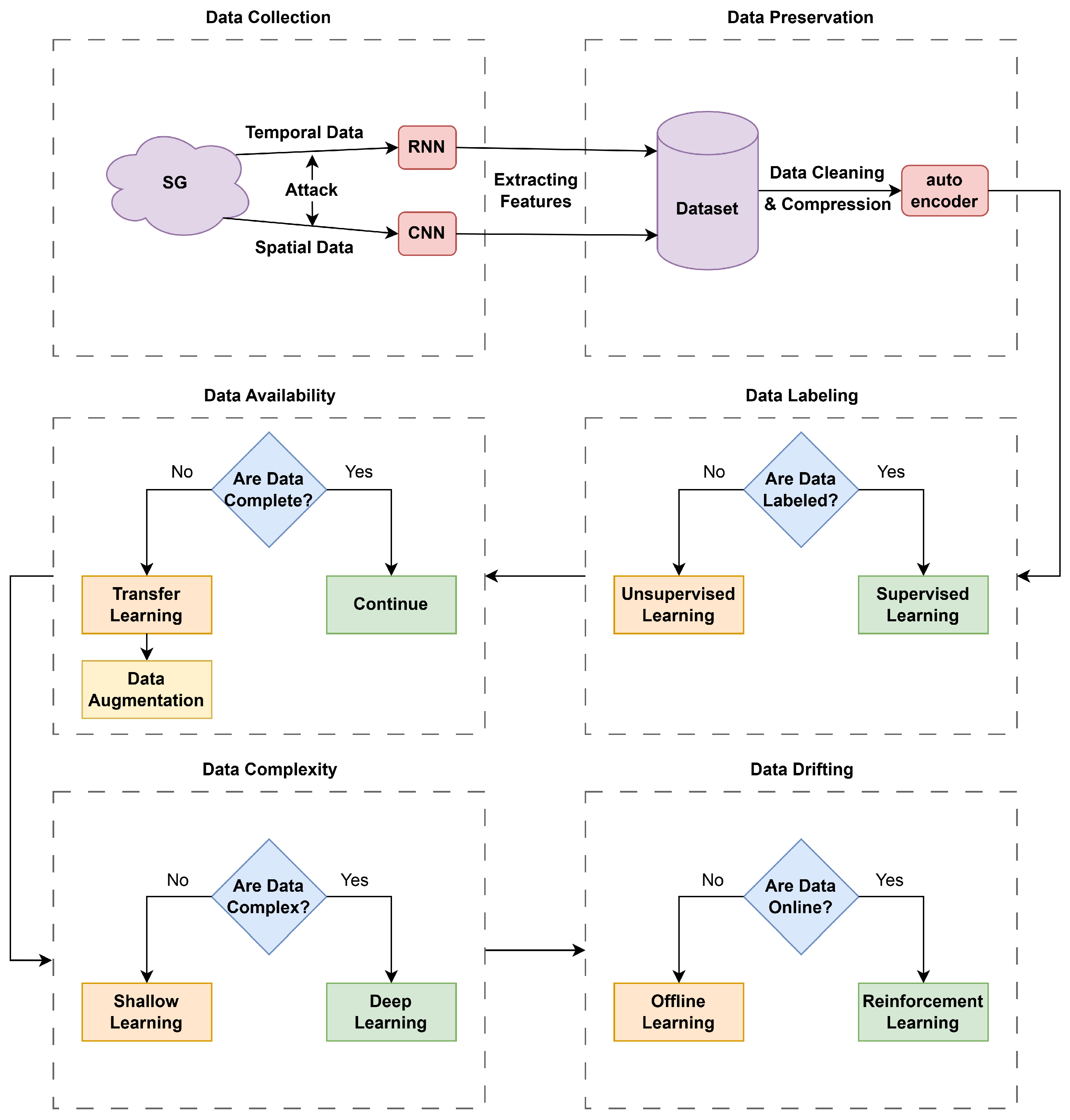

Figure 4 illustrates cyber-physical attack & defense framework in smart grids.

An IoT-based EM system by adopting a cloud communication channel for networked devices in smart local areas was proposed [

112]. This type of connectivity provides the data privacy, interoperability, redundancy, flexibility, and real-time features needed for EM. The proposed technology is based on global and local communication layers that rely on HTTP TCP/IP and MQTT protocols for cloud interactions. The communication infrastructure of the SG was analyzed, the protocols used in communications were verified, and the system’s vulnerabilities to CAs were identified [

82].

A secure communication protocol based on time, hash, and private vital constraints has also been proposed using the Sample Value protocol and the General Object Oriented Substation Events protocol. The proposed protocol creates a secure session key and then verifies it via authentication. The proposed protocol was implemented using the AVISPA tool, and its security was verified. A hybrid energy-efficient dynamic scheduling MAC protocol is proposed and is used for traffic-adaptive WSNs [

113]. The proposed protocol consists of group or cluster formation and data transfer. In the cluster formation stage, the Variable Step Size Firefly Algorithm is proposed to generate energy-aware clusters by optimal selection of cluster heads. Its main function is to reduce the cost of determining the optimal placement of key nodes in the cluster. The following criteria: residual energy, node degree, number of possible group vertices, and distance within the group are considered criteria for selecting the objective function. Delay, latency, and overhead are reduced and controlled by data communication during the data transfer phase. The proposed approach has proven to help users reduce power consumption, extend network lifetime, and reduce overall overhead. A detailed SG Communications Network survey was presented [

114]. The requirements of architecture, communications networks, applications, and technologies were studied.

A new scalable and flexible SGCN using cognitive radio (CR) technology is proposed. The proposed approach uses multiple layers through which the communication spectrum is divided into Wide Area Network, Neighborhood Area Network, and HAN. To facilitate the key agreement between the cloud server and the smart card/user via a TA, an improved and secure authentication scheme was proposed [

83]. The proposed system was applied to the cloud server and SM. The proposed system is resistant to known attacks, which leads to a slight increase in communication and computation costs. Using formal analysis supported by a discussion of security features, the security of the proposed system is verified. The Robust Cramer Shoup (RCS) Delay Optimized Fully Homomorphic system was proposed for privacy-preserving and secure data transfer for deep learning (DL) [

115]. The proposed approach is based on three steps: First, use the Kullback–Leibler divergence in the RCS decoding mechanism to reduce the communication burden and time. Second: The Delay Full Homomorphic Encryption mechanism is designed to reduce data access time and network delay. Third: To transfer data securely and preserve privacy, privacy-preserving DL using RCS Delay and Delay Optimized Fully Homomorphic Encryption is used.

A methodology is proposed to obtain accountability metrics in the cloud. The proposed methodology consists of three stages [

116]. First, a conceptual analysis of these features is conducted to analyze the features of accountability into concrete mechanisms and practices. Second: Relevant control frameworks are analyzed to guide the implementation of security and privacy mechanisms related to the practices and mechanisms identified from the first step and used to identify measurable factors. The Cloud Control Matrix, privacy controls from NIST SP 800-53, and the Generally Accepted Privacy Principles were used for this analysis. Third: Specific measures (either quantitative or qualitative) for these factors are extracted. To encrypt information and enhance the security of IoT communications while maintaining ease of use. An asymmetric ECC algorithm is proposed [

117]. The role of ECC in lightweight authentication mechanisms is discussed in Section Authentication Methods and Privacy Protection. As for the process of storing information, compressed sensing has been proposed. Data compression is reconstructed using BCs to improve the speed of data storage in the IoT.

Using the Web of Objects and cloud architecture, an interoperable IoT platform for SHs is proposed [

118]. The platform provides SH data in the cloud to benefit from SPs’ applications and analytics. Through the platform, home appliances can be controlled from anywhere. First, to interoperate between different communication technologies and protocols and various old home devices, a gateway based on Raspberry PI was proposed. Second: Through the Representational State Transfer framework, SH devices are uploaded to the web and made available. Third: To store home data, a cloud server is provided for SHs, and data is provided and analyzed by various application SPs. A new hybrid communication approach based on Enterprise Service Buses (ESBs) was proposed [

119]. This approach adds limited delay tolerance to strict real-time communication. This is done using additional fault-tolerant features that extend the core mechanism by adding failover behavior to the ESB-based connection. The proposed approach allows the system to continue running even when messages are violated and also allows fault isolation for timing violations to be available. Using Monte Carlo simulations, the introduced fault tolerance features are analyzed. With two direct methods for hard real-time communications, the throughput of the resulting data is compared. Attacks targeting different network layer functions in CR networks were classified [

120]. Attacks found in traditional wireless networks were also analyzed, and their feasibility in CR network was studied. Based on the specifications of some attacks, it is detailed that they can only occur in the CR network, such as primary user activity and spectrum availability. Current mitigation techniques for each attack are also presented. Attention was paid to a wireless communication system with energy harvesting and error correction codes [

121]. The optimization algorithm for transmission power, code rate, and modulation scheme is jointly studied. The goal is to maximize the actual average information transfer rate. The method for determining the Raptor code coding rate is first given within the known SN rates. The formula for the actual transmission rate is deduced using a specific coding and modulation rate. An optimization problem is created to maximize the actual average transmission rate. Using the Lyapunov optimization framework, the original long-run optimization problem is transformed into a single problem per time period. Through simulation, the proposed algorithm was verified.

A review of power line communications (PLC) for the SG was done [

122]. The status, progress, challenges, and opportunities were discussed. PLC-based solutions/systems for renewable energy (RE) integration are reviewed in terms of Distributed PS and DERs monitoring/control and management modules. A detailed review of standards for the use of PLC in the field of SG has been carried out [

123]. A study was also conducted on using PLC technologies in SG applications to determine the extent of PLC compatibility. To improve the problems related to PLC, the advantages and disadvantages of PLC for SG applications were analyzed. Proposed new standards and protocols for PLC were reviewed to standardize possible solutions. To reduce the processing time and network traffic while maintaining the privacy of each user, a data communication system for the AMI network was proposed [

124]. The proposed system helps reduce the burden of encryption, as the assembly and encryption processes are carried out in a hybrid manner, which enhances the applicability of various SG applications. The results show that the proposed system has less coding overhead, especially when the number of SMs per capacitor is very large. A global resilience measure has been demonstrated in the context of synchronous Communication Network (CN) [

125]. The resilience measure expresses the system’s ability to return to an operational state after a failure. An evaluation methodology for SC network plasticity has also been proposed. The ubiquitous sensor network of the International Telecommunication Union was studied and applied to the SG [

126]. The technologies needed for secure and resilient communication using the ubiquitous sensor network’s schematic layers are demonstrated. The weaknesses of the mentioned system and challenges were studied, as well as the pros and cons. Factors that can influence the choice of communication techniques are discussed. Possible communication technologies at different USN layers have been proposed. To address the problems of interoperability and scalability, the USN middleware system is discussed.

The comparative analysis of communication protocols in

Table 3 is synthesized from the technical specifications, performance benchmarks, and vulnerability assessments reported in the reviewed literature on SG communications. The ratings for characteristics like latency, data rate, and susceptibility are relative comparisons based on typical operating conditions for each protocol. For instance, the high jamming susceptibility of ZigBee and Wi-Fi is a well-documented consequence of their operation in the crowded, unlicensed 2.4 GHz ISM band, while LoRaWAN’s long range and low jamming susceptibility are due to its spread spectrum technique.

The comparative analysis in

Table 3 highlights critical trade-offs for SG deployments. For instance, while ZigBee and Wi-Fi offer low latency suitable for real-time HAN applications, their operation in crowded ISM bands makes them highly susceptible to jamming and interference, a significant security concern. In contrast, LoRaWAN and NB-IoT, designed for Wide Area Networks (WANs), offer long range and better resistance to jamming (especially NB-IoT on licensed spectrum) but incur higher latency, making them suitable for non-critical meter data collection rather than real-time control. PLC provides a unique alternative using existing infrastructure but is vulnerable to noise on the power lines, which can be intentionally created as a DoS attack. Therefore, protocol selection is a critical security decision: HAN protocols prioritize speed but require additional security layers against jamming, while WAN protocols prioritize range and reliability for data aggregation but are ill-suited for time-sensitive protection schemes.

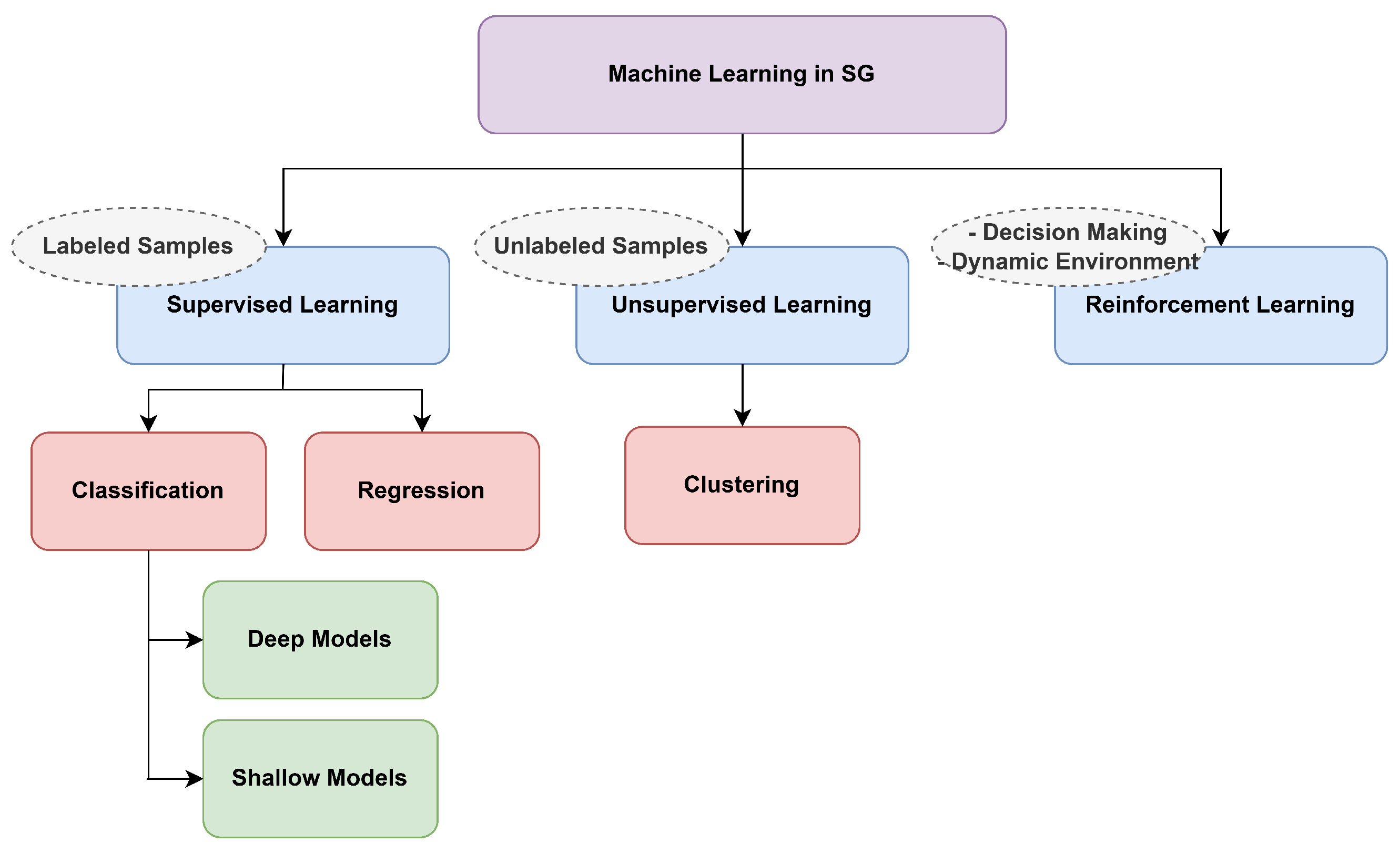

6. Machine Learning in Cybersecurity

ML techniques, such as Support Vector Machine (SVMs), XGBoost SVMs, DTs, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and others, are currently being used to enhance protection against CAs and detect intrusions in SGs [

127], as shown in

Figure 5. This section will examine the research papers and studies on this subject.

Table 4 shows the ML techniques for detecting CAs in the SG. Some of these works have been mentioned in other sections because they are relevant to the topic. For example, a comprehensive survey was conducted to demonstrate the various ML-based methods for detecting CAs on SNs [

128].

A demand-side management (DSM) employs ML to protect the IoT from CAs [

129]. DSM protects efficient energy use. A specific resilience factor model is proposed to manage SG’s SG incursion and DSM. ML classifiers are used to predict fraudulent companies. A processing unit is introduced in the DSM engine to process energy data produced by the IoT-enabled HAN to optimize energy usage. The concepts of smart cities, their connection to SC, and how to employ them in this field were summarized and explained [

130]. Many DL models were reviewed, such as Deep Belief Network (DBN), generative adversarial networks (GANs), Boltzmann machines, constrained Boltzmann machines, convolutional neural networks (CNN), and recurrent NNs. DBN processes data and transforms it into low-dimensional data while retaining essential features. For a security system with high accuracy and analytical ability, Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) is more suitable for classification than CNN. RNN-based functions, such as RNN-IDS, are essential factors in improving the accuracy of IDSs in SC [

131]. While traditional Line-Commutated Converter (LCC) HVDC systems are generally regarded as having relatively low CS risk due to their simpler control structure and limited reliance on wide-area communication, the transition to multi-terminal LCC DC grids brings new vulnerabilities. These grids incorporate multiple inverter stations and require coordinated control over extensive communication networks—making them susceptible to cyber-physical attacks. Coordinated cyberattacks targeting multiple inverter nodes could disrupt stability or initiate cascading failures. Liu et al. [

132] present grid-forming techniques and fault ride-through strategies based on fault current limiters in LCC-type DC grids, highlighting resilience at the control level. However, their work does not address CS attack surfaces or threat mitigation in such grid architectures. Thus, while these control strategies bolster operational robustness, further research is urgently needed to identify and defend against emerging cyber-attack vectors in high-capacity, multi-inverter DC infrastructures.

To effectively detect malicious attacks, a new interval state predictor is proposed [

133]. The outer bounds of the state variables are formulated as a two-level optimization problem. Accordingly, any case outside the estimated limits can be considered an anomaly. To predict electrical loads, a DL algorithm has been applied that helps significantly improve prediction accuracy, called DBN. The effectiveness of the proposed system was verified on IEEE 14 and 118 bus systems. A new protection framework for cyber and physical systems of SGs based on DL was proposed [

134,

135]. The proposed technique detects and addresses the CA using a set of techniques specifically designed for SG CS. Because SG CS datasets are asymmetric, this proposal creates new symmetric presentations for asymmetric risk management datasets. As in the proposed attack detection (AD) model, deep NNs and DT classifiers are used.

Table 4 provides a descriptive summary of the machine learning techniques discussed in the reviewed literature, mapping specific models to the types of attacks they were designed to detect and the datasets or systems used for validation. It is important to note that this table catalogs the reported applications and findings from the primary studies; it does not represent a direct, quantitative performance ranking of the models, as such a comparison would require a uniform benchmark across all studies, which is not available.

Table 4.

Machine learning techniques for detecting cyberattacks in smart grid.

Table 4.

Machine learning techniques for detecting cyberattacks in smart grid.

| Ref. | Description | Attack | Model | Dataset/System |

|---|

| [126] | Protecting IoT from fraudulent companies | CAs | DSM | Realistic data from IoT-enabled HAN |

| [129] | Investigating the CS in SC | Not mentioned | DBN—GAN—CNN—RNN | Not mentioned |

| [130] | Anomaly-based detection using optimized interval state predictor | Malicious attacks | DBN | Realistic data from IEEE 14/18 bus system |

| [133] | Protecting cyber and physical systems of SG based on DL | CAs | Deep Neural Network (DNN)—DT | SG CS datasets |

| [134] | Reducing the computational cost by applying a small-scale ML model | Not mentioned | NAHL | EL-NAHL |

| [136] | Using IAI technique to classify anomalies | DoS—FDI | MSVM | Real-time digital simulator OPAL-RT |

| [137] | Detecting the FDI attack in SG using three independent methods | FDI | FDIDT—FDILR—FDILRT | Not mentioned |

| [138] | Investigating the efficiency of a multi-layer anti-attack defense framework | Typical passive attacks | Deep Autoencoder—Ensemble DNN | ns-3, FNCS and GridLAB-D simulators |

| [139] | Identifying the type of attacks in network communication channels | Physical layer attacks | Set of ML models | Simulated SG dataset |

| [140] | Investigating the CS in SCADA FOR ICS networks | malicious attacks | DBN—SVM | Not mentioned |

| [141] | Evaluating the performance of ML models in CAs detection | BOT-IoT | Set of ML models | Iot intrusion and

anomaly identification dataset |

| [142] | Investigating the efficiency of SituRepair for critical infrastructure protection | mutation fault (MF) | Automated Program Repair (APR) | Code4Bench |

| [143] | Evaluating the performance of SML-DM model in SGCPN) | Cyber intrusions | SRS—DPE | Wireless sensor dataset |

| [144] | Utilizing IWP-CSO method to optimize HNA-NN in SCADA networks | Cyber intrusions | HNA-NN | Simulated SG dataset |

| [145] | Developing Smart Hybrid Technique (SHT) model to detect Deep Learning Algorithm (DIA) attacks in the hybrid MGs | DIA | SHT | HMG according to the IEEE standard system |

A small-scale ML algorithm was proposed in SC to reduce computational costs [

136]. The methodology is based on algorithmic complexity, imbalance, data complexity, and real threat scenarios. The proposed algorithm relies on an NN with an augmented hidden layer (NAHL) to accomplish learning quickly and efficiently. A label autoencoder (AE) approach is also introduced to solve the problem of data complexity concerning rapid change and dynamism. The encryption approach is based on embedding labels into the NAHL structure (EL-NAHL) to take advantage of the spread of labels when separating sparse data.

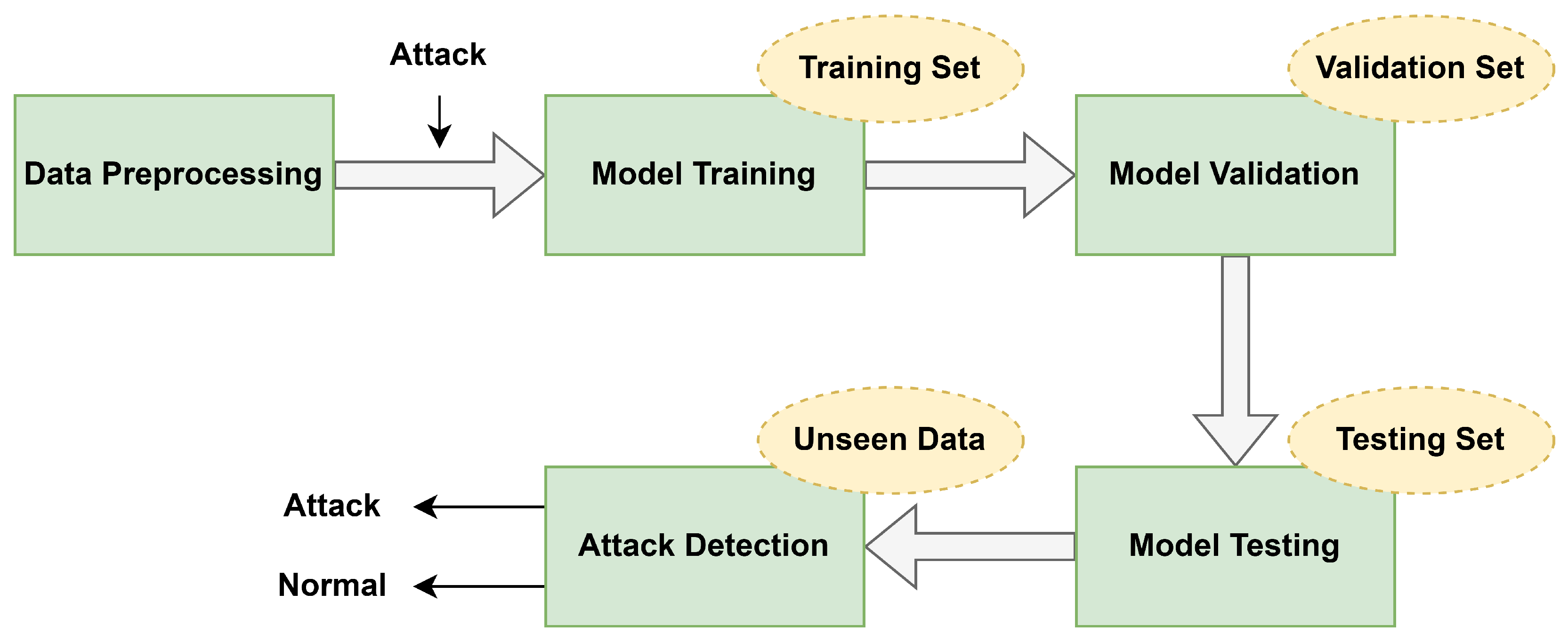

An intelligent anomaly identification technique was proposed in distributed control-based cooperative MG AC systems [

137].

Figure 6 shows data preprocessing and selection of learning types. The technology is based on data-driven AI tools, which use multi-class SVMs to classify anomalies such as Denial of Service (DoS) attacks, FDI attacks, etc. [

146]. Optimal statistical features extracted from the measurements are used to train the Multi-class Support Vector Machine (MSVM). The proposed technique was validated on a real-time digital simulator OPAL Real-Time Technologies (OPAL-RT) by comparing it with Naive Bayes (NB) classification and Artificial Neural Network (ANN).

To confront the FDI attack in SGs, three independent techniques were proposed [

138]. First: delta thresholding, linear regression, and linear regression with a timestamp. In addition, an algorithm is proposed to predict missing data. The strength of the proposed attack algorithms has been confirmed through the latest defense technologies.

Similarly, using different potential attack scenarios, a Q-Learning-based deep FDI attack generator was developed and configured with typical passive attacks [

139]. Next, a multi-layer AD defense framework was created using the Deep Auto Encoder Network and Snapshot Ensemble Deep NN to detect known and unknown threats. The proposed model is verified using a combination of ns-3, FNCS, and GridLAB-D simulators.

An intelligent model for detecting and identifying attacks was proposed [

140]. This model can classify the type of attack at the physical layer based on a set of machine-learning methods. In order to mitigate the impact of the attack on CNs, the proposed model converts the error or attack into specific measurements or features in the system. Unlike traditional ML algorithms, the proposed model adopts feature sorting based on hit probability. This sorting is verified by a chi-square test that ranks those features based on their association with each label. The proposed algorithm was tested on a SG dataset with 36 attack and fault scenarios simulated by Oak Ridge National Laboratories and using F1-Score and MCC classification.

A secure SCADA architecture was proposed for an ICSs network to protect the network from malicious attacks [

141]. The proposed architecture is based on developing two detection model algorithms: a DBN and SVMs. The advantage of the proposed architecture is that it uses the payload feature and the network traffic feature for the detection model. DBNs detect attacks by forming Restricted Boltzmann Machines. For the SCADA network, batch methods for DBN have also been proposed. Different DBN structures are combined to create a set of DBNs for final detection.

A hybrid algorithm and framework model are proposed to solve the problem of choosing the effective ML algorithm among different algorithms to help the system detect CAs [

142]. The proposed algorithm works by applying the IoT intrusion and anomaly identification dataset, and from several features of the ML algorithm, the 44 effective features are selected [

147].

Figure 7 explains the methodology of AD in the SG. Then, five practical ML algorithms are selected to determine the most common ML algorithm performance evaluation metrics and identify attack traffic Bot-IoT. The binary soft ensemble approach and algorithm are applied to determine practical ML algorithms. An APR technique developed to repair Multiple Failure software was presented in [

143]. Its purpose is critical infrastructure protection. The proposed model relies on ML to predict the type and status of error within the given program. The effectiveness of SituRepair has been verified through extensive experiments within Code4Bench.

A statistical ML defense mechanism is proposed to protect smart cyber-physical networks from cyber intrusion [

144]. The proposed mechanism uses a mixture model of wireless sensor data with an embedded Gaussian. Two new indicators were proposed to evaluate the defense mechanism’s performance. The first is the Sensor Reliability Score, which evaluates the reliability status of wireless sensors. Second, Data Prediction Error calculates actual and expected data errors during a CA.

Cuckoo search optimization techniques based on weighted particle and hierarchical neuron structure-based NN are proposed [

145]. The proposed technique aims to detect and classify intrusions in a SCADA network to improve the network lifetime [

148]. This technique works by providing an input grid dataset as input, where selected features are arranged for further processing. Then, the features are improved using the proposed technique by reducing the dimensions of the features, which can effectively improve the accuracy. Finally, using the HNA-NN classification technique, the best-selected features are classified, which in turn classify intrusions into the network.

The impact of data integrity attack on the performance of hybrid MGs was studied [

149]. A sequential hypothesis testing methodology has also been developed to detect these intrusions. The analysis statistic is calculated using a binary sample using the proposed approach. Then, a comparison is made with two thresholds to choose from among the three options. Real simulation work is performed in Hybrid Microgrid according to the IEEE standard system.

Despite their promising performance were showed, the deployment of DL models for cybersecurity in SGs faces several significant challenges. A primary concern is their data dependency; DL models require massive volumes of high-quality, labeled training data, which can be difficult and costly to obtain for rare but critical cyber-attack scenarios in operational grid environments.

Furthermore, the computational complexity of training and inferencing with deep networks (e.g., CNNs, LSTMs) may be prohibitive for resource-constrained edge devices like field sensors or relays, necessitating a cloud or fog computing architecture that introduces latency.

The black-box nature of many DL models also poses a critical problem for grid operators who require explainability to understand why an alarm was triggered and to take trustworthy corrective actions.

Finally, DL models are themselves vulnerable to adversarial attacks, where an attacker can craft subtle perturbations to input data that can fool the model into making incorrect classifications, thereby bypassing the detection system. These limitations necessitate a careful cost-benefit analysis and often lead to hybrid approaches that combine the pattern recognition power of DL with the transparency and reliability of traditional methods.

Table 5 gives critical comparison of which algorithms perform best under what circumstances.

7. Theoretical Frameworks for Defense and Attack

In this section, summaries of some scientific research and works that dealt with theories of defense or attack in the field of SC in SGs, particularly networks of other systems, such as the IoT, will be mentioned.

Table 6 can Summarize the CAs in the SG. The

Table 7 also Compares between shallow and DL for security objectives in the SG.

Yingmeng Xiang and Lingfeng Wang worked on developing an optimal budget allocation strategy and theoretical interaction between attack and defense to prevent LR attacks, where attack and defense interactions were integrated into the two-level modeling of these attacks [

150]. An optimal budget allocation strategy is developed to defend critical substations to minimize the expected load loss subject to the attacker’s capability. Strategies for enhancing SC were studied using game theory-based methods for different attack scenarios. Using simulation on an IEEE test system, the proposed strategies are tested. A method for creating and solving a game theory model to address SC problems was presented [

151]. The game theory approach can be applied to manufacturing to measure system reliability and analyze different defense policies to counter CAs. The proposed method offers a unique approach to determining the contents of the game payoff matrix. This approach is achieved by integrating sustainment, recovery from attacks, production losses, and defense strategies, three characteristics of manufacturing systems, into the cost function that represents reality in manufacturing systems. The lower bound method was also used to calculate NE and universal utility.

A practical approach for power transmission planners has been developed to secure PGs from CAs [

152]. The approach is based on proposing a three-level multi-objective methodology between the defender (the system planner), the rational attacker, and the operator. A commonly used reinforcement strategy for network protection is also proposed. A new type of resource has been introduced within the concept of deception, which is considered an effective tool to mislead the attacker in strategic planning. In the model based on shared perception, the defender’s deception is mathematically modeled by releasing false information about the defender’s plan. In the event of deception failure, the risk of damage is reduced by programming preventive objectives to prioritize a reinforcement strategy. The benefits of deception to the system are also shown, which is called situational value. With three-level mixed integer linear programming, the problems are formulated. The method of generating the constraint and column was solved. Simulations of the proposed approach have been performed on WSCC 9-bus and IEEE 118-bus systems.

A framework was proposed called “Decepti-SCADA” [

153]. The proposed framework applies deception as a technique to improve the SC posture of a network. The proposed model uses decoys to obfuscate the network, making it difficult for the attacker to find the real components. The proposed framework has two parts: the publishing side is represented by Decepti-Box, and ELKSUR represents the monitoring side. A Decepti-Visual graphical user interface has also been created to facilitate the performance of security tasks using the Decepti-SCADA framework.

Relying on data for cyber-physical SG systems, a new method for evaluating the time delay (TD) of Wide Area Measurement System was proposed [

154]. It is a random-based quantitative model that studies TD attacks. Using M/M/1 queuing theory and signal avoidance methods, the probability distribution function of multiple arrival times in the spatial sequence is depicted, considering the transmitted process of the data packet in the cyber layer. Sklar’s and copula theorem combine distribution functions with multiple delays into a new quantitative model of delay. According to the reason for generating the TD, it is divided into two parts: first, delay resulting from network attacks, and second, delay inherent. The delay caused by the first section is detected using the connectivity principle and likelihood ratio. The simulation was done on an IEEE 39 bus system. Application and case studies were performed on a ten-machine PS in New England. A solution to the FDIA problem was reviewed [

155,

156]. An efficient implementation methodology for identifying precise intrusion points in real-time based on DL was proposed [

157]. Traditional bad data detectors work with DL models to identify FDIs within a measurement set [

158]. The methodology uses multi-layer perceptual models, CNN, CNN-LSTM, CNN-BiLSTM, and a DT. The DL models used in the proposed methodology also capture inconsistency with simultaneous dependency on potential attack vectors. Network operators can also detect attacks in real-time without any initial statistical assumptions of the network through these models. The simulation was done on a standard IEEE test. A vulnerability indicator was proposed to counter FDIA [

159]. The proposal works to secure the meters most at risk. The attacker works to corrupt the output of the state estimator by normalizing the meter readings. The proposed methodology is based on identifying a set of attack vectors called important attack vectors [

160]. All attack vectors with lower costs will be avoided if important attack vectors with lower costs are avoided. The proposed methodology can classify counters based on the number of attack vectors attacking a device using significant attack vectors. An algorithm has also been proposed to determine which counters to secure. The proposed index was simulated using the IEEE test system. An algorithm was proposed to detect the moment when an attack on a CPS begins [

161]. The algorithm is based on the principle of retrospective research, not real-time. Via the back-end and back-of-the-observer approach, a batch-type detection algorithm for the attack moment is proposed. The proposed algorithm addresses the problem of “temporarily hidden” sensing attacks for polynomial types. These are types of attacks that traditional anomaly detectors can hardly detect the moment of attack in real-time.

A resilience-based grid recovery scheme is proposed to restore the SG after successful CAs on substations [

162]. The proposed scheme is based on a measure developed to capture: First: energy-side resilience (PsR). This includes available spare capacity, load, reliability, and available line capacity, and these four characteristics are used to evaluate the resilience status of the SG through the proposed recovery measure (CPARM). Second: Cyber flexibility (CsR). The one that calculates the resilience of the physical side based on immediate damage is PsR. CsR calculates the resilience of the cyber side based on the potential damage to the system. Various SG constraints and capabilities such as automatic generator control (AGC) capability, transient stability, ramp rate, multi-stage attacks, and load changes during the recovery phase are incorporated to achieve a more realistic model. The proposed methodology has been applied to a 39-bus New England test system and a 30-bus IEEE test case.

Analysis and design of security of networked control systems based on an attack space based on the corresponding adversary model description, adversary model knowledge, disruption resources, and disclosure was proposed [

163]. The proposed methodology analyzed various CAs, such as replay attacks, DoS attacks, bias injection attacks, and zero dynamics. Using the concept of secure clusters, the attack impact of each scenario is characterized, and the attack policy is described. A defense strategy was developed that considers distributed generators to increase the PG’s reliability against coordinated attacks [

164,

165]. A robust three-level optimization model was developed to enhance defense strategies against cyber-attacks in SGs [