1. Introduction

The global energy sector stands at a critical juncture, facing the dual imperative of meeting escalating global energy demand while carrying out urgent decarbonization efforts to combat climate change. This transition is characterized by unprecedented complexity. The large-scale integration of intermittent renewable energy sources (RESs), such as solar and wind, introduces significant variability and uncertainty into power generation. Simultaneously, the proliferation of distributed energy resources (DER)—such as rooftop solar, battery storage, and electric vehicles—transforms consumers into prosumers, creating bidirectional energy flows that challenge traditional grid management [

1,

2]. Compounding this are dynamic demand-side patterns driven by new technologies and changing consumer behavior, rendering conventional forecasting and control paradigms inadequate. This challenge is particularly acute in developing regions, where AI can play a pivotal role in managing decentralized microgrids and improving energy access, thereby fostering sustainable development.

In response to this multifaceted challenge, artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a technology that is both indispensable and capable of gradual improvement [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. It has the capability to manage the inherent complexity of modern energy systems, moving beyond static, rule-based control to dynamic, data-driven optimization. Integrating AI technologies into core energy systems—including smart grids, microgrids, and building energy management—can unlock unprecedented capabilities in real-time optimization, autonomous control, predictive analytics, and enhanced security [

8,

9]. Recent technological advances have already demonstrated quantifiable improvements across multiple energy system domains, addressing critical challenges from the predictive maintenance of vital infrastructure to the autonomous control of complex, interconnected networks [

10,

11].

Given the critical challenge faced by the global energy sector to meet rising energy demands and facilitate decarbonization, this paper argues that AI is an essential tool for managing the complexity of energy systems. This paper comprises a detailed review and demonstration of the capabilities of key AI domains—including neural networks, reinforcement learning, and fuzzy logic—to improve energy system efficiency, reliability, and autonomy. Furthermore, this paper presents a unified technical implementation framework to overcome the significant technical and ethical challenges associated with AI integration, providing a path through which more resilient and sustainable energy grids can be built.

This article adopts a narrative review approach, synthesizing evidence from high-impact research in the literature, published primarily between 2020 and 2025. The analysis prioritizes AI subdomains—specifically neural networks, Evolutionary Algorithms, and reinforcement learning—based on their demonstrated maturity, scalability, and disruptive potential in real-world energy applications. The selection criteria focused on peer-reviewed studies, underscoring the need for the Unified Implementation Framework proposed in

Section 4.

2. Key AI Domains and Their Transformative Applications

2.1. Neural Network Systems: From Prediction to Stability

Deep Learning, a subfield of machine learning that utilizes artificial neural networks, has become a cornerstone of modern AI applications in the energy sector. Its strength lies in identifying intricate patterns and nonlinear relationships within vast datasets. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), in particular, are revolutionizing classification and detection tasks. A compelling application is in power system fault classification, which is a critical function for maintaining grid reliability. A comprehensive study of the IEEE-30 bus system demonstrated that a CNN-based model achieved an average fault classification accuracy of 99.27% [

12]. This system directly processes raw voltage and current signals, eliminating the need for complex preprocessing and enabling real-time fault detection and classification. This results in drastically reduced response times and mitigates the risk of cascading failures.

Beyond fault detection, neural network-based Power System Stabilizers (PSSs) offer potential advantages over conventional controllers through adaptive parameter adjustment [

13]. Multi-layer feedforward networks, utilizing inputs such as a generator’s real power, reactive power, and terminal voltage, can effectively adapt parameters in real time. The adaptive capability of these controllers enables dynamic parameter adjustments based on system loading conditions, with training methodologies employing gradient descent back-propagation [

13].

Additionally, Cieślik et al.’s [

14] results demonstrate that artificial neural networks (ANNs) can reliably generalize beyond their training data, accurately predicting compact heat exchanger outlet temperatures even under untested operating conditions. This capability directly supports the vision that ANN-based energy systems can adapt to variability and uncertainty where conventional thermal modeling methods fail.

At the same time, training neural networks with a modified loss function augments data patterns and information via statistical constraints, improving the model’s generalization capability [

15,

16]. In this regard, active research is underway to enforce linear and nonlinear constraints within the neural network architecture, ensuring domain-consistent predictions. Constraint satisfaction enables neural networks to produce feasible predictions [

17], which is beneficial for energy systems, where safety and regulatory requirements are of paramount significance for control applications.

The application of CNNs for fault classification is a prime example of Phase 1 (Algorithm Selection and Design) of the proposed framework, in which a specific AI technique is chosen to solve a critical domain problem (see

Section 4).

2.2. Deterministic and Evolutionary Algorithms: Mastering Multi-Objective Optimization

Mathematical optimization techniques, including linear and nonlinear programming, are frequently employed to determine optimal solutions for single- and multi-objective optimization of techno-economic and environmental objectives [

18,

19]. Optimization solvers include an interior point, CPLEX, SNOPT, CONOPT, etc., which provide theoretical guarantees in determining the optimal solutions [

20]; however, computational complexity and overhead remain a challenge for solving large-scale optimization problems.

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs), particularly Genetic Algorithms (GAs), offer a robust, population-based search strategy for solving complex, multi-objective optimization problems. Unlike traditional methods, which can become trapped in local optima, GAs consistently explore a vast solution space to converge on globally optimal solutions [

20]. This capability is exceptionally valuable in the energy sector, where decisions often involve balancing multiple, frequently conflicting, objectives.

A prime example is in building energy management. Advanced variants, such as the Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), have demonstrated exceptional performance in optimizing energy consumption, occupant thermal comfort, and overall economic performance [

21]. The application of GAs extends to the city scale, where they have been used to develop models for predicting energy consumption in single-family residential buildings, providing a crucial tool for urban planning and utility resource management [

20].

Employing advanced algorithms such as NSGA-II to balance conflicting objectives aligns perfectly with the design principles of Phase 1 of the framework, which emphasize multi-criteria optimization (see

Section 4).

2.3. Reinforcement Learning: The Dawn of Autonomous Energy Management

Reinforcement learning (RL), and its advanced form, Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), represent a paradigm shift toward fully autonomous decision-making in dynamic environments [

22,

23]. DRL agents learn optimal policies through direct interaction with a system, making them ideally suited for the real-time control of complex energy networks [

3,

4,

5,

6].

The impact of DRL is particularly striking in the domain of electric vehicle (EV) energy management. Deep Reinforcement Learning methods are advanced reinforcement learning algorithms that leverage deep neural networks to approximate value functions, policies, or models of the environment. In DRL, an agent interacts with an environment, receives state information, selects actions, and receives rewards, generally aiming to maximize the cumulative expected reward over time. The agent learns optimal behavior via trial-and-error combined with feedback from the environment.

A comprehensive real-world study using an immense dataset of over 60 million kilometers of driving data demonstrated that offline RL agents employing an Actor–Critic and Blended Prioritized Replay (AC-BPR) algorithm could achieve 88% to 98.6% of the theoretical optimum performance after just two training updates [

24].

Actor–Critic with Blended Prioritized Replay builds on standard Actor–Critic methods by employing prioritized experience replay. The actor network learns an optimal policy, while the critic estimates the value function. The Blended Prioritized Replay mechanism improves sample efficiency during training by selectively replaying transitions from memory according to priority criteria.

Furthermore, recent implementations of DRL frameworks, including Deep Q-Networks (DQN), have revealed that model-free controllers can yield up to 12% improvements in overall energy efficiency and extend battery life by 8% compared to rule-based benchmarks [

23].

This makes DRL an ideal technology for Phases 2 (System Integration and Validation) and 3 (Deployment and Continuous Improvement), as autonomous agents must interact with and control physical systems in real time (see

Section 4).

2.4. Fuzzy Logic Control: Handling Uncertainty with Intelligence

Fuzzy logic (FL) control systems provide an elegant and practical framework for managing systems with multiple input sources, complex operational constraints, and inherent uncertainty [

25,

26]. Their ability to operate based on imprecise information makes them exceptionally well-suited for hybrid energy systems.

For instance, a fuzzy-logic-integrated energy management system for commercial loads with a hybrid grid–solar PV/battery system intelligently selects energy sources based on grid energy costs and the battery’s state of charge. This approach resulted in an average daily energy cost reduction of 11.87% and a 7.94% reduction over 20 years [

25]. For off-grid applications, a fuzzy-logic-based model for a standalone solar PV–wind system with battery storage reduced operational costs by 11.87–18.7% and significantly lowered carbon emissions compared to traditional diesel-based systems [

27]. Finally, fuzzy-logic-based approaches have the potential to be used in modeling practical problems that can be formalized using experience rather than strict knowledge of the process [

28]. Thus, fuzzy-logic-based systems utilize expert knowledge to describe the complex behavior of the systems.

3. Upcoming Developments: AI Agents and Quantum Computing

3.1. AI Agents: The Rise in Autonomous and Agentic Systems

The concept of Agentic AI—encompassing autonomous “agents” designed to execute specific tasks and automate workflows—is rapidly gaining traction [

29,

30]. In the energy sector, these intelligent software programs, powered by sophisticated algorithms and machine learning, transform customer relationship management (CRM) platforms into active energy management hubs. These agents analyze vast amounts of data to identify patterns and make informed decisions, enabling energy companies to operate more efficiently and deliver exceptional, personalized services [

30].

3.2. Quantum Computing: Overcoming the Limits of Classical Systems

As the complexity and variability of energy systems continue to grow, classical computational methods are approaching their inherent limits. Quantum Computing and Quantum Machine Learning (QML) offer a revolutionary approach to solving currently intractable problems [

31,

32,

33,

34]. By utilizing quantum bits (qubits), which can exist in multiple states simultaneously, quantum computers can process vast datasets and explore an exponential range of potential solutions far more efficiently than classical systems.

The potential applications in energy are profound and can be categorized into three key areas:

Renewable Energy Forecasting—quantum algorithms can integrate and analyze data from diverse sources—such as weather models, environmental sensors, and historical trends—at a currently unattainable scale [

31].

Optimized Grid Management—quantum computing can rapidly analyze grid conditions to identify potential bottlenecks, optimize power flow, and recommend real-time adjustments [

31].

Energy Storage and Demand Response—QML can optimize the deployment and utilization of energy storage systems and design sophisticated demand–response strategies [

35,

36].

Specific collaborations, such as those between Pasqal and Électricité de France (EDF), are already demonstrating the potential of quantum algorithms to optimize EV charging schedules and enhance the integration of renewable energy [

31]. Furthermore, pioneering research is exploring the use of QML in applications such as Blockchain-Based Quantum Reinforcement Learning (QRL) for secure and efficient peer-to-peer energy trading [

32], quantum algorithms for electricity theft detection [

35], and advanced condition monitoring for wind turbines that overcome the limitations of classical ML [

36]. A recent analysis identified 22 distinct QML use cases in the energy sector and concluded that, while the field is in its early stages, its potential benefits are exceptionally high [

37].

However, conventional quantum methods, especially those based on quantum kernel models (QKM), face significant scalability challenges as qubit counts increase, even though QRL has the potential to handle problems with large state and action spaces efficiently [

32]. This balance is challenged by several serious algorithmic and physical challenges: First, the “Barren Plateau” challenge is central to parameterized quantum circuits (PQCs), where the variance of the cost function gradient has been shown to decrease exponentially with increasing qubit counts, making optimization in larger systems extremely challenging due to vanishing gradients [

37].

Second, naive QKMs degrade in performance as qubit counts increase because the data become “too far apart” in an exponentially large Hilbert space [

34].

Finally, research consistently confirms that current quantum devices operate in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, meaning they have a limited number of qubits and are susceptible to errors caused by environmental noise and imperfect control. Consequently, managing quantum errors (decoherence) remains a significant challenge in the NISQ era [

37]. Thus, while the theoretical advantage is established, practical, fault-tolerant quantum supremacy in optimization remains a near-future milestone rather than an immediate plug-and-play solution.

4. Integration Challenges and a Strategic Implementation Framework

The convergence of AI and modeling energy processes and systems presents significant challenges. Therefore, despite AI’s vast potential, its deployment in the energy sector is hampered by substantial limitations and ethical challenges.

Firstly, many advanced AI techniques and intensive learning methods are characterized by high energy consumption. According to reports from the International Energy Agency (IEA), data centers and AI systems are placing increasing strain on power grids. Therefore, a paradox emerges: AI-based technology devoted to energy use optimization becomes a significant consumer, and more energy-efficient algorithms, falling into the category of so-called Green AI, are critical to develop a sustainable energy transition [

38]. According to the data, increasing ML model complexity results in a significant increase in energy and cooling water consumption. This is especially noticeable in the case of LLMs, which consume large amounts of resources not only during training, but also when handling each query. These facts clearly highlight the need to implement the Green AI paradigm, which is a pivotal approach to enhancing environmental sustainability (e.g., neuromorphic chips). This paradigm includes green-by AI and green-in AI strategies, for eco-friendly practices in other fields and for designing energy-efficient machine learning algorithms and models, respectively [

38].

Secondly, since AI-based systems are only as good as the data they are trained on, latent biases in historical energy data may lead to inequitable or suboptimal behaviors.

Finally, profound ethical questions remain regarding accountability for managing critical infrastructure failures, transparency of decision-making processes, and data security against cyber threats.

All these issues should be addressed, especially considering the increasing autonomy of AI-based solutions.

Therefore, successful deployment requires a strategic approach that addresses data quality, model interpretability, cybersecurity, and seamless system integration [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

29,

39,

40,

41,

42].

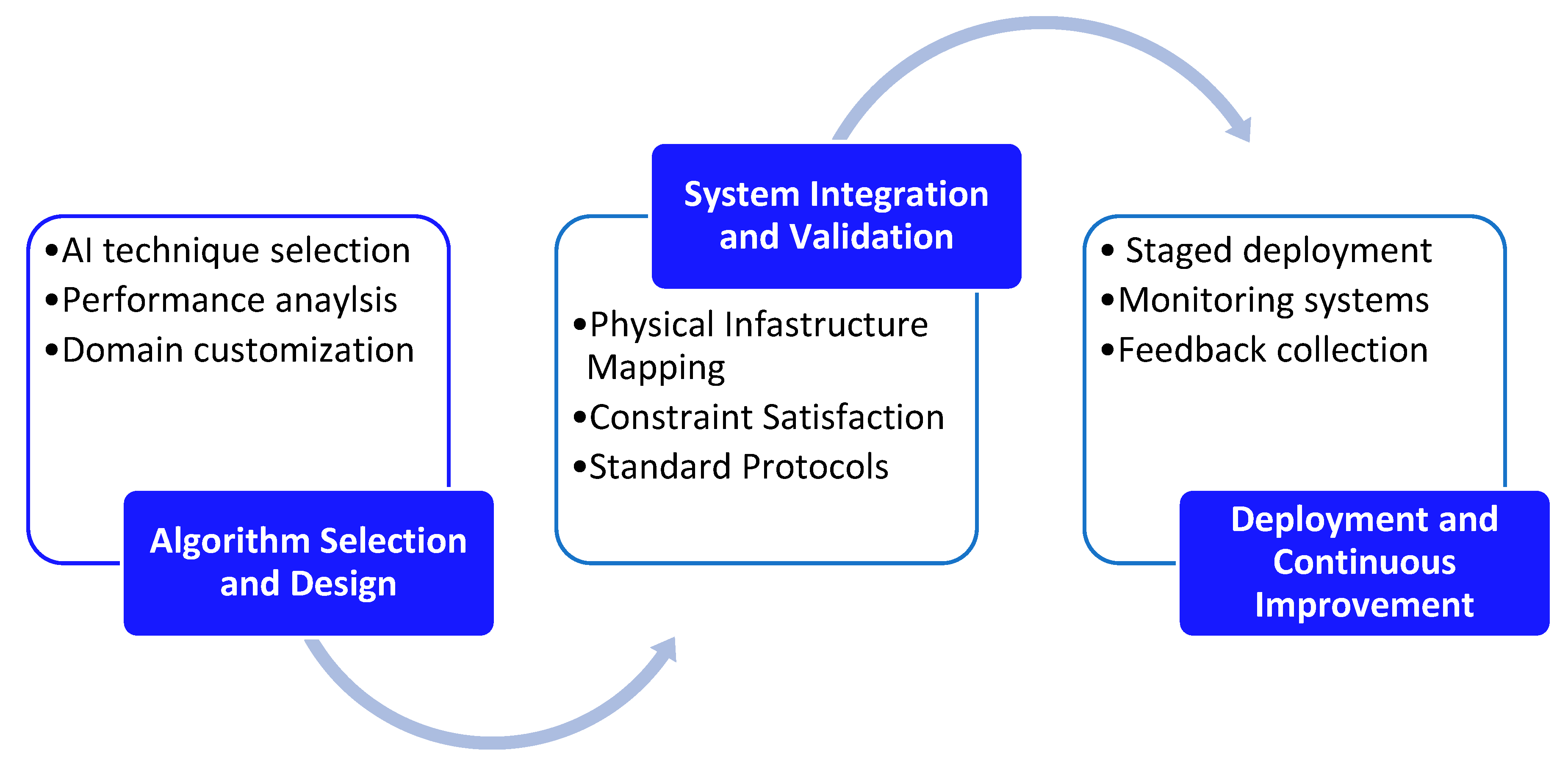

To navigate these complexities, a unified technical implementation framework is proposed (

Figure 1).

Phase 1: Algorithm Selection and Design

This initial phase involves rigorous analysis of performance requirements, selection of appropriate AI techniques, and design of a scalable, robust system architecture [

3,

4,

5,

6]. The domain-customized algorithm design and satisfaction of system constraints remain critical for the strategic implementation of AI systems across the value chains of energy systems, e.g., for the predictive maintenance of DC microgrids [

43,

44,

45]. It is important to remember that AI systems can overcome the shortcomings of classical models [

46,

47,

48].

Phase 2: System Integration and Validation

This phase focuses on seamlessly integrating AI algorithms with existing physical energy infrastructure through standardized protocols, middleware solutions, and APIs [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Phase 3: Deployment and Continuous Improvement

A staged deployment with comprehensive monitoring and feedback systems is crucial [

3,

4,

5,

6,

28].

The novelty of the proposed framework lies in the holistic integration of algorithmic design with physical grid constraints and business-layer deployment—a gap often overlooked in the purely computer-science-focused literature. It serves as a techno-economic bridge, ensuring that the proposed approaches are not only theoretically optimal but also operationally viable.

5. Conclusions

The fusion of artificial intelligence and energy represents a fundamental technological paradigm shift, offering quantifiable benefits across the entire value chain. From the proven performance of neural networks and reinforcement learning to the immense future potential of AI agents and Quantum Computing, AI provides an indispensable toolkit for building more efficient, resilient, and sustainable energy systems. Realizing this vision requires continued interdisciplinary research, robust collaboration between academia and industry, and a strategic commitment to addressing the technical and ethical challenges ahead. The path is set for an energy landscape that is not just connected, but intelligent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K. and A.K.-K.; writing—review and editing, J.K., A.K.-K., A.G., I.I., W.M.A., A.R., J.T. and W.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| AC-BPR | Actor–Critic with Blended Prioritized Replay |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CRM | Customer Relationship Management |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resources |

| DQN | Deep Q-Networks |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| EA | Evolutionary Algorithm |

| EDF | Électricité de France |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| FL | Fuzzy Logic |

| FLC | Fuzzy Logic Control |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| NISQ | Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum |

| NSGA-II | Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II |

| PSS | Power System Stabilizers |

| PQC | Parameterized Quantum Circuits |

| QKM | Quantum Kernel Model |

| QML | Quantum Machine Learning |

| QRL | Quantum Reinforcement Learning |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

References

- Omitaomu, O.A.; Niu, H. Artificial Intelligence Techniques in Smart Grid: A Survey. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 548–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpavalli, M.; Noman, M.; Kumar, S.; Praksh, S.; Memala, W.A.; Bhuvaneshwari, C.; Sivagami, P. AI-Driven Energy Management System for Industrial and Commercial Facilities to Enhance Energy Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Advanced Applications (ICISAA), Pune, India, 25–26 October 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, W.M.; Uddin, G.M.; Kamal, A.H.; Khan, M.H.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmad, H.A.; Ahmed, F.; Hafeez, N.; Sami, R.M.Z.; Arafat, S.M.; et al. Optimization of a 660 MWe Supercritical Power Plant Performance—A Case of Industry 4.0 in the Data-Driven Operational Management. Energies 2020, 13, 5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnowski, M.; Krzywanski, J.; Scurek, R. A Fuzzy Logic Approach for the Reduction of Mesh-Induced Error in CFD Analysis: A Case Study of an Impinging Jet. Entropy 2019, 21, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baszczuk, A.; Krzywanski, J. A Comparison of Fuzzy Logic and Cluster Renewal Approaches for Heat Transfer Modeling in a 1296 t/h CFB Boiler with Low Level of Flue Gas Recirculation. Arch. Thermodyn. 2017, 38, 91–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywanski, J.; Sztekler, K.; Szubel, M.; Siwek, T.; Nowak, W.; Mika, Ł. A Comprehensive, Three-Dimensional Analysis of a Large-Scale, Multi-Fuel, CFB Boiler Burning Coal and Syngas. Entropy 2020, 22, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunde, A.A.; Okwandu, B.A.; Akande, K.O.; Sikhakhane, L.M. Reviewing the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Energy Efficiency Optimization. Energy Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniandi, B.; Maurya, P.K.; Bhavani, C.H.; Kulkarni, S.; Yellu, R.R.; Chauhan, N. AI-Driven Energy Management Systems for Smart Buildings. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukoba, K.; Olatunji, K.O.; Adeoye, E.; Jen, T.-C.; Madyira, D.M. Optimizing renewable energy systems through artificial intelligence: Review and future prospects. Energy Environ. 2024, 35, 3833–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo, P.; Ochoa-Correa, D.; Villa-Ávila, E. Optimizing Microgrid Operation: Integration of Emerging Technologies and Artificial Intelligence for Energy Efficiency. Electronics 2024, 13, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.; Rashid, A.; Biswas, A.; Abdullah, N. AI-Driven Approaches for Optimizing Power Consumption: A Comprehensive Survey. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikariha, A.; Bag, B.N.; Londhe, N.D.; Raj, R. Fault Classification in an IEEE 30 Bus System using Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Recent Developments in Control, Automation & Power Engineering (RDCAPE), Noida, India, 7–9 October 2021; pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbani, A.; Gianto, R. Neural Network and Its Application in Electric Power System Damping Controller: A Review. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Res. 2021, 9, 1–7. Available online: https://www.researchpublish.com (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Cieślik, T.E.; Marcinkowski, M.; Sacharczuk, J.; Ziółkowska, E.; Taler, D.; Taler, J. Generalization challenges in optimizing heat transfer predictions in plate fin and tube heat exchangers using artificial neural networks. Energy 2025, 325, 136092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, W.M.; Dua, V. Data Information integrated Neural Network (DINN) algorithm for modelling and interpretation performance analysis for energy systems. Energy AI 2024, 16, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, T.; Ashraf, W.M. Comparison of Kolmogorov–Arnold Network and Multi-Layer Perceptron models for modelling and optimisation analysis of energy systems. Energy AI 2025, 20, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constante-Flores, G.E.; Chen, H.; Li, C. Enforcing Hard Linear Constraints in Deep Learning Models with Decision Rules. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.13858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindlish, R.; Baldea, M.; Harjunkoski, I.; Zavala, V. Trends and perspectives in computed-aided process operations and control. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2024, 182, 108575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wächter, A.; Biegler, L.T. On the implementation of an interior-point filter line-search algorithm for large-scale nonlinear programming. Math. Program. 2006, 106, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Wang, Y.; Khan, S.; Khan, I.; Sajjad, M. Genetic algorithm-based optimization for power system operation: Case study on a multi-bus network. Int. J. Adv. Electr. Eng. 2024, 5, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiri, E.; Maftouni, N. Multiple objective energy optimization of a trade center building based on genetic algorithm using ecological materials. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahani, E.; Cetin, K.; Cho, I.H. City-scale single family residential building energy consumption prediction using genetic algorithm-based Numerical Moment Matching technique. Build. Environ. 2020, 172, 106667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananganó-Alvarado, G.; Umaña-Morel, I.; Keith-Norambuena, B. Reinforcement learning in electric vehicle energy management: A comprehensive open-access review of methods, challenges, and future innovations. Front. Future Transp. 2025, 6, 1555250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; He, H.; Wei, Z.; Sun, F. Data-driven energy management for electric vehicles using offline reinforcement learning. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, O.; Bakare, M.S.; Amosa, T.I.; Otuoze, A.O.; Owonikoko, W.O.; Ali, E.M.; Adesina, L.M.; Ogunbiyi, O. Development of fuzzy logic-based demand-side energy management system for hybrid energy sources. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2023, 18, 100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghassab, M.A. Fuzzy-based smart energy management system for residential buildings in Saudi Arabia: A comparative study. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 1212–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfred, N.; Guntreddi, V.; Shuaibu, A.N.; Bakare, M.S. A fuzzy logic based energy management model for solar PV-wind standalone with battery storage system. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywanski, J.; Sztekler, K.; Lasek, L.; Kalawa, W.; Grabowska, K.; Sosnowski, M.; Zylka, A.; Skrobek, D.; Nowak, W.; Shboul, B. Performance enhancement of adsorption cooling and desalination systems by fluidized bed integration: Experimental and big data optimization. Energy 2025, 315, 134347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noura, H.N.; Yaacoub, J.P.A.; Salman, O.; Chehab, A. Advanced Machine Learning in Smart Grids: An overview. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2025, 5, 95–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesforce. AI Agents for Energy and Utilities. Available online: https://www.salesforce.com/energy-utilities/artificial-intelligence/ai-agents-for-energy/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- World Economic Forum. See How Quantum Computing Can Revolutionize Energy Forecasting and Optimization. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/01/quantum-computing-energy-forecasting/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Kashyap, P.K.; Dohare, U.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, S. Blockchain and Quantum Machine Learning Driven Energy Trading for Electric Vehicles. Ad Hoc Networks 2024, 165, 103632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nammouchi, A.; Kassler, A.; Theocharis, A. Quantum Machine Learning in Climate Change and Sustainability: A Short Review. Proc. AAAI Symp. Ser. 2024, 2, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Broughton, M.; Mohseni, M.; Babbush, R.; Boixo, S.; Neven, H.; McClean, J.R. Power of data in quantum machine learning. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, E.; Cuéllar, M.P.; Navarro, G. On the Use of Quantum Reinforcement Learning in Energy-Efficiency Scenarios. Energies 2022, 15, 6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ma, X. Quantum machine learning based wind turbine condition monitoring: State of the art and future prospects. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 332, 119694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strata, F.; Migliori, L.; Gebran, N.; Guarino, N.; Colombo, G.C.; Pezzuolo, S.; Luzietti, E. Quantum Machine Learning early opportunities for the energy industry: A scoping review. Front. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2025, 4, 1653104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolón-Canedo, V.; Morán-Fernández, L.; Cancela, B.; Alonso-Betanzos, A. A review of green artificial intelligence: Towards a more sustainable future. Neurocomputing 2024, 599, 128096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywanski, J.; Czakiert, T.; Nowak, W.; Shimizu, T.; Ashraf, W.M.; Zylka, A.; Grabowska, K.; Sosnowski, M.; Skrobek, D.; Sztekler, K.; et al. Towards cleaner energy: An innovative model to minimize NOx emissions in chemical looping and CO2 capture technologies. Energy 2024, 312, 133397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongar, B.; Beloev, H.; Georgiev, A.; Iliev, I.; Kijo-Kleczkowska, A. Optimization of the design and operating characteristics of a boiler based on three-dimensional mathematical modeling. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 55, 153–159. Available online: https://www.bcc.bas.bg/BCC_Volumes/Volume_55_Number_2_2023/bcc-55-2-2023.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kijo-Kleczkowska, A.; Gnatowski, A.; Krzywanski, J.; Gajek, M.; Szumera, M.; Tora, B.; Kogut, K.; Knaś, K. Experimental research and prediction of heat generation during plastics, coal and biomass waste combustion using thermal analysis methods. Energy 2024, 290, 130168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijo-Kleczkowska, A.; Gajek, M.; Krzywanski, J.; Gnatowski, A.; Knaś, K.; Szumera, M.; Nowak, W. Novel insights into co-pyrolysis: Kinetic, thermodynamic, and AI perspectives. Energy 2025, 326, 136301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, W.M.; Dua, V.; Debnath, R. Domain Consistent Industrial Decarbonisation of Global Coal Power Plants. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, W.M.; Keshavarzzadeh, A.H.; Alshehri, A.S.; Jumah, A.B.; Debnath, R.; Dua, V. Domain-Informed Operation Excellence of Gas Turbine System with Machine Learning. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Hossain, M.J.; Li, L. Advanced Deep Learning Based Predictive Maintenance of DC Microgrids: Correlative Analysis. Energies 2025, 18, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskala, W.; Krzywański, J.; Czakiert, T.; Nowak, W. The research of CFB boiler operation for oxygen-enhanced dried lignite combustion. Rynek Energii 2011, 92, 172–176. Available online: https://www.rynek-energii.pl/index.php/pl/node/215 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Muskała, W.; Krzywański, J.; Rajczyk, R.; Cecerko, M.; Kierzkowski, B.; Nowak, W.; Gajewski, W. Investigation of erosion in CFB boilers. Rynek Energii 2010, 87, 97–102. Available online: https://www.rynek-energii.pl/pl/node/89 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Muskała, W.; Krzywański, J.; Sekret, R.; Nowak, W. Model research of coal combustion in circulating fluidized bed boilers. Chem. Process Eng. –Inz. Chem. I Proces. 2008, 29, 473–492. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261712888 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |