Assessing the Pace of Decarbonization in EU Countries Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

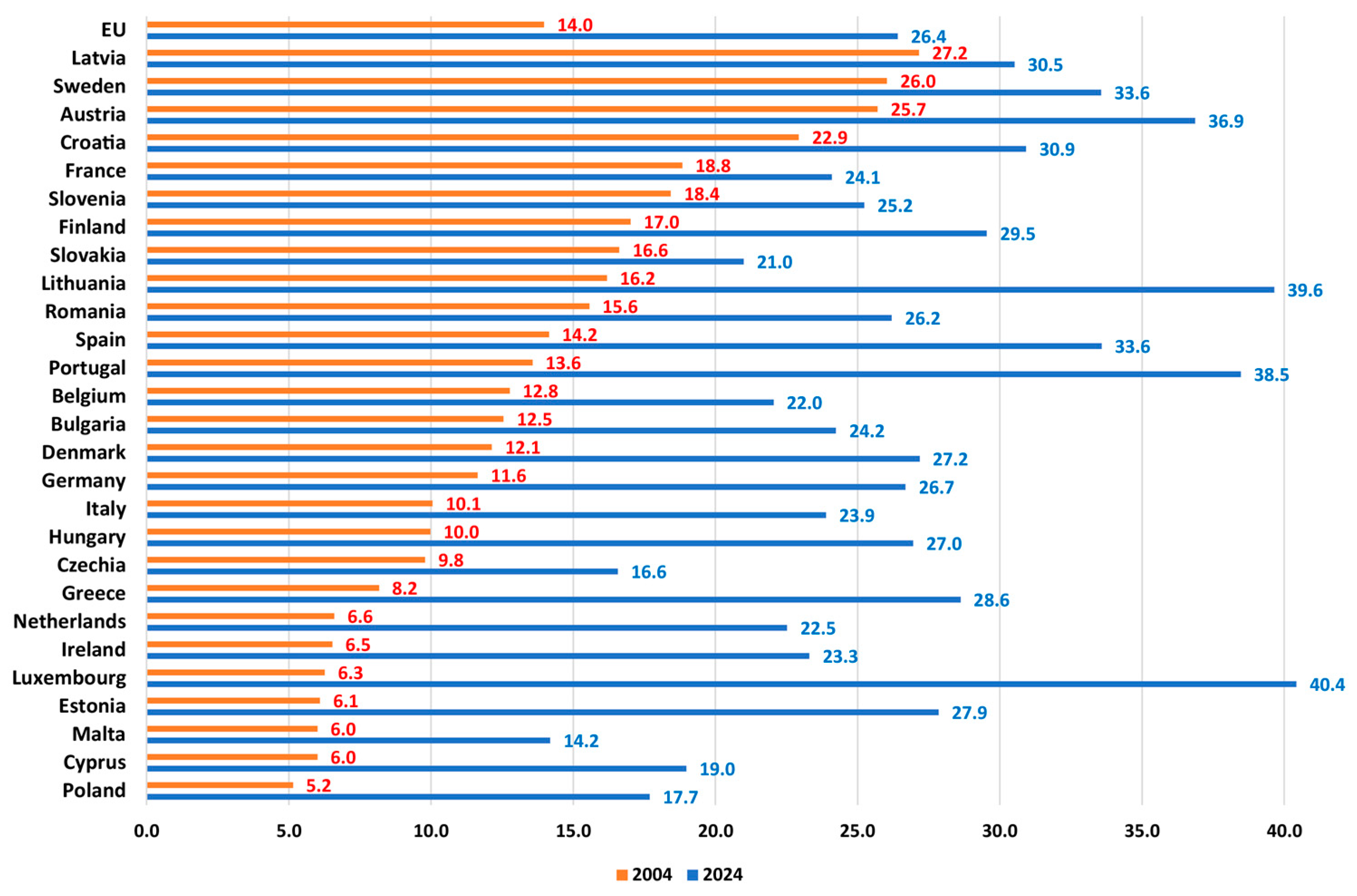

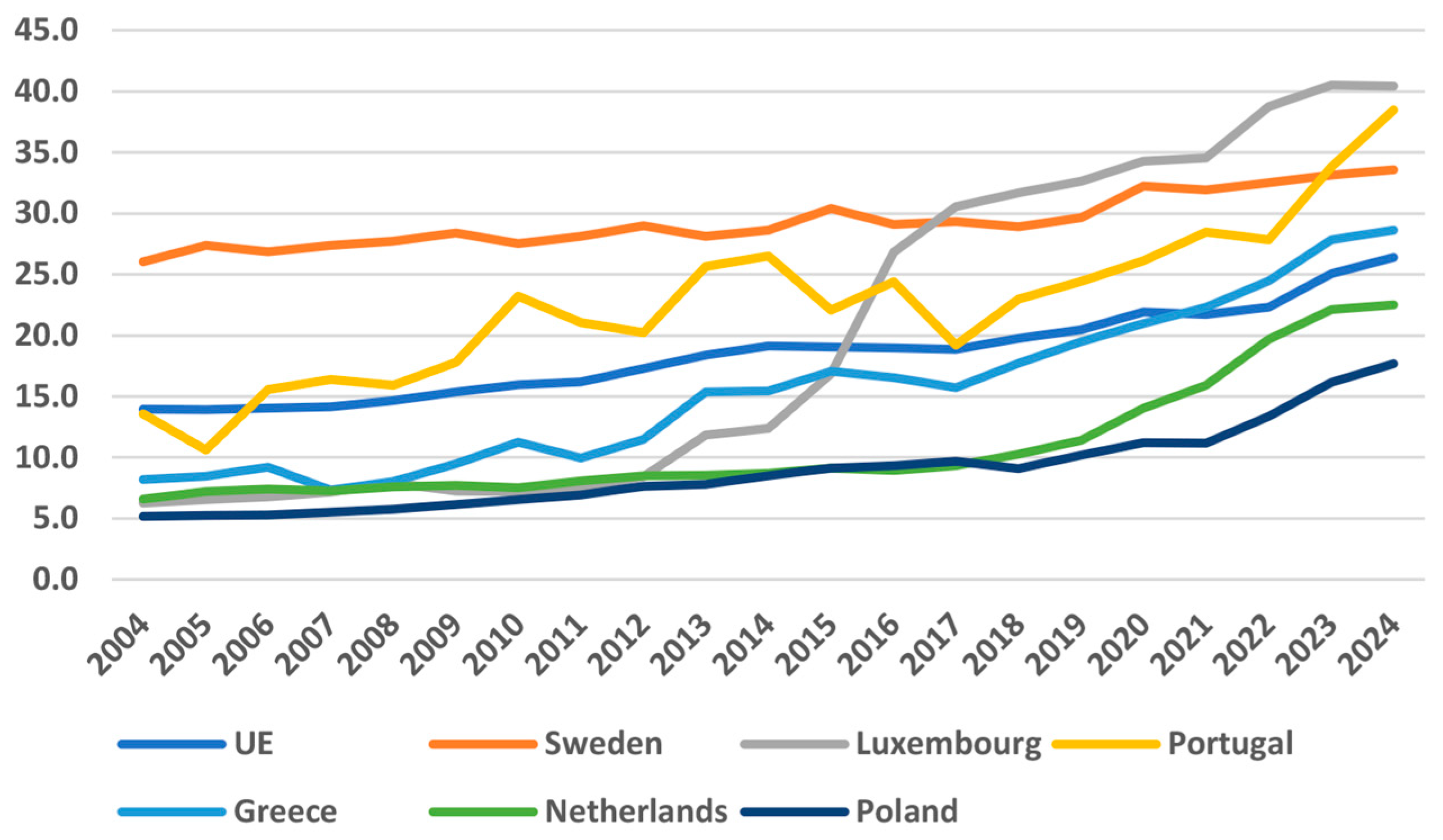

Legislative Measures for Climate Protection

- revision of the emissions trading system to include polluting sectors such as buildings and road transport from 2027 in ETS II (Emission Trading System) and maritime transport [13],

- review of the market stability reserve to address the structural imbalance between supply and demand for allowances in the EU ETS [14],

- implementation of a carbon leakage instrument that sets a greenhouse gas emission charge for imported goods [15],

- a joint effort to reduce emissions among EU countries in transport, agriculture, construction, and waste management—from 29% to 40% by 2030 [16],

- strengthening regulations to increase carbon dioxide absorption in the LULUCF (land use, land use change, and forestry) sector [17],

- revising the transport proposal (net-zero emission passenger cars and vans by 2035 [18],

- changes to aviation emission allowances [19],

- increasing the number of charging and refueling stations for passenger cars and trucks powered by alternative fuels [20],

- requirement to gradually transition to sustainable aviation fuels [19],

- new targets for reducing energy consumption at EU level by 2030 [21],

2. Purpose of the Analysis and Research Methodology

- Identification of criteria for the assessment of electricity generation technologies;

- Construction of a hierarchical model for achieving climate neutrality;

- Estimation and aggregation of weighting factors (expert assessments);

- Construction of a decarbonization index;

- Construction of a cumulative decarbonization index.

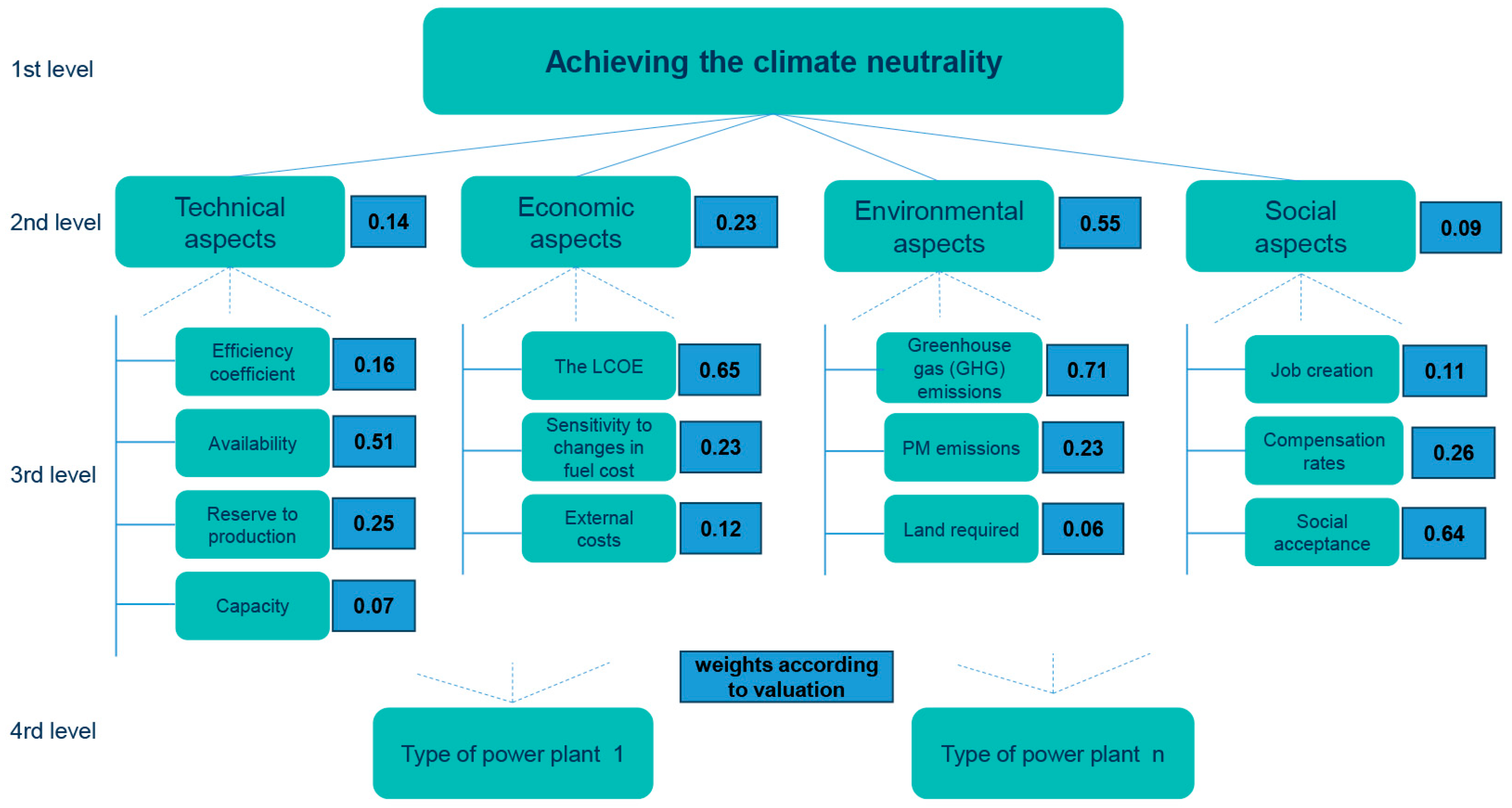

2.1. Criteria for Assessing Electricity Generation Technologies

- Efficiency factor [%] expresses the ratio of output energy to input energy. Efficiency refers to how much useful energy (in this case, electricity) can be obtained from a given energy source.

- Reliability factor [%] is the ability to generate electricity within a specified time. A power plant may experience downtime in energy production due to maintenance, servicing, or weather conditions such as lack of sunlight or wind. It shows the availability and efficiency of the power plant.

- Reserves to production ratio R/P [years]—the R/P ratio indicates the availability (in years) of a specific type of fuel based on current consumption and the annual rate of increase/decrease in consumption of each non-renewable energy source for electricity generation. When assessing fuel quantities, only well-known sources that can be practically exploited are taken into account.

- Capacity [%]—the actual amount of energy generated in a given period of time and the maximum energy that could be generated if the power plant were operating at full capacity during that time.

- Levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) [USD/MWh]—total cost of construction and operation of a power plant, including capital expenditure, operating expenditure, fuel, and disposal costs. This parameter is intended to contribute to the achievement of target 12.c: Rationalize inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption.

- Sensitivity to fuel price changes—the criterion used here is the share of fuel costs in the unit cost of electricity generation.

- External costs—costs incurred in relation to health and the environment. These costs can be measured but are not built into the cost of electricity. External costs are funds paid to restore people’s health and ensure the efficient functioning of ecosystems. They compensate for the side effects of power plant operations.

- Implementing national social protection systems and measures for all (goal 1.3),

- ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all by 2030 (goal 7),

- Increasing the share of renewable energy in the national energy mix by 2030 (goal 7),

- Doubling the national rate of improvement in energy efficiency by 2030 (goal 7),

- Promoting sustainable, inclusive, sustainable, and innovative economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all (goals 8 and 9),

- Ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns, achieving sustainable management of natural resources and their efficient use, ensuring awareness of sustainable development and a lifestyle in harmony with nature (goal 12).

- Gas waste generation—this parameter takes into account greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as CO2 equivalents. It determines the concentration of carbon dioxide whose emission into the atmosphere would have the same effect as a given concentration of a comparable greenhouse gas.

- Particulate matter emissions—this is the emission of fine particulate matter (e.g., PM2.5 and PM10) expressed as the number of particles per unit of energy in the life cycle of a power plant.

- Land management—the impact of power plants on the environment, social structure, and land use. This refers to the land area occupied by energy infrastructure.

- ensuring healthy lives (goal 3),

- by 2030, increase sustainable urbanization and sustainable human settlements management (goal 11),

- by 2030, achieve sustainable management of natural resources and their efficient use (goal 12),

- taking action to combat climate change and its impacts; strengthening human resilience to climate-related hazards; improving education, awareness-raising and human capacity on climate change mitigation (goal 13).

- Job creation—a parameter ensuring the achievement of the goal: To end poverty in all its forms.

- Compensation—compensation for the local community directly affected by the installation and operation of the power plant. Compensation for the deterioration of quality of life due to harmful emissions, landscape destruction, and noise.

- Social acceptance—consent of local residents to the operation of the power plant. Unmeasurable parameter. High acceptance is crucial for the pace of energy transition.

- ending poverty and hunger, creating food security and better nutrition, and promoting sustainable agriculture (goal 2),

- ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being (goal 3),

- ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all; percentage of population using clean fuels and clean energy technologies (goal 7),

- increasing the share of renewable energy in the national energy mix by 2030 (goal 7),

- promoting sustainable, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all (goal 8),

- making cities and human settlements safe and sustainable. By 2030, reduce the negative environmental impact of cities, paying attention to air quality and municipal waste management. Support positive economic, social, and environmental links between urban, suburban, and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning (goal 11),

- ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns; achieve sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources by 2030 (goal 12).

- take urgent action to slow down climate change (goal 13),

- protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, halt and reverse land degradation, and halt biodiversity loss (goal 15).

2.2. Model Structure for Achieving Climate Neutrality

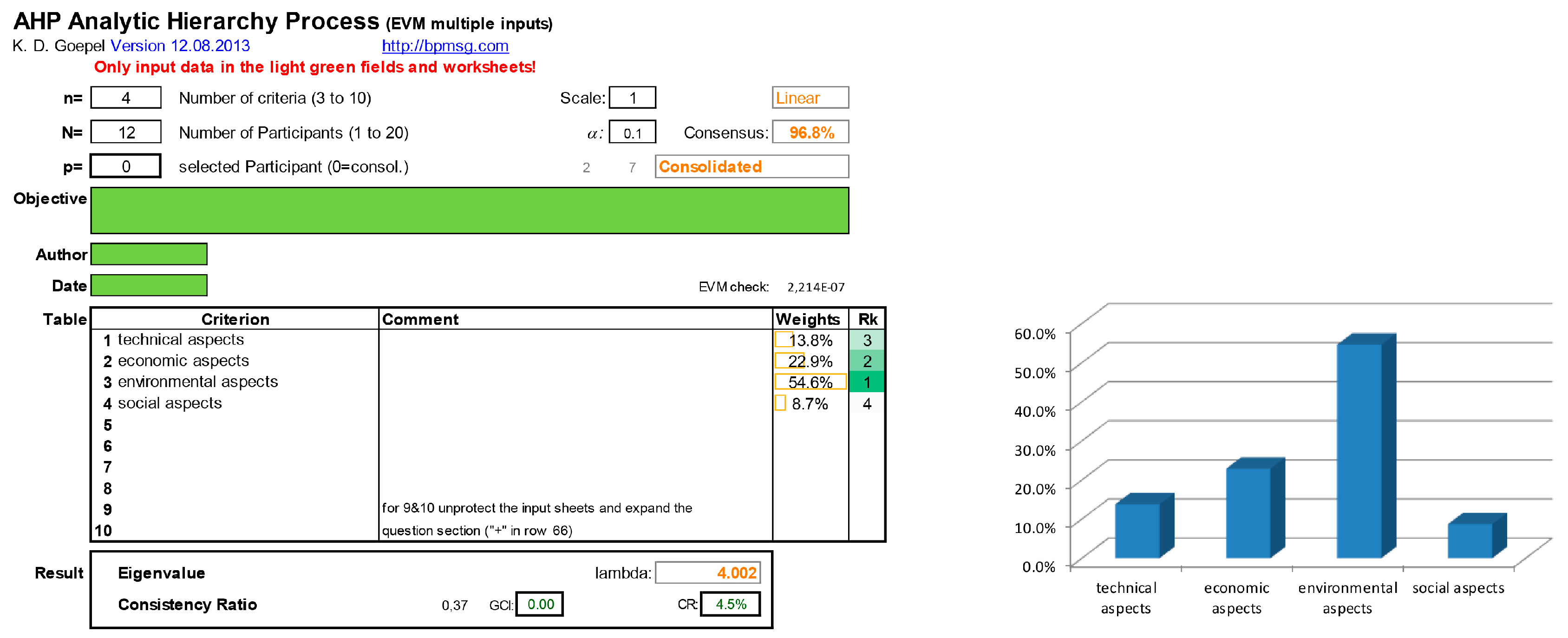

2.3. Assessment of the Priorities of Individual Criteria Forming the Model

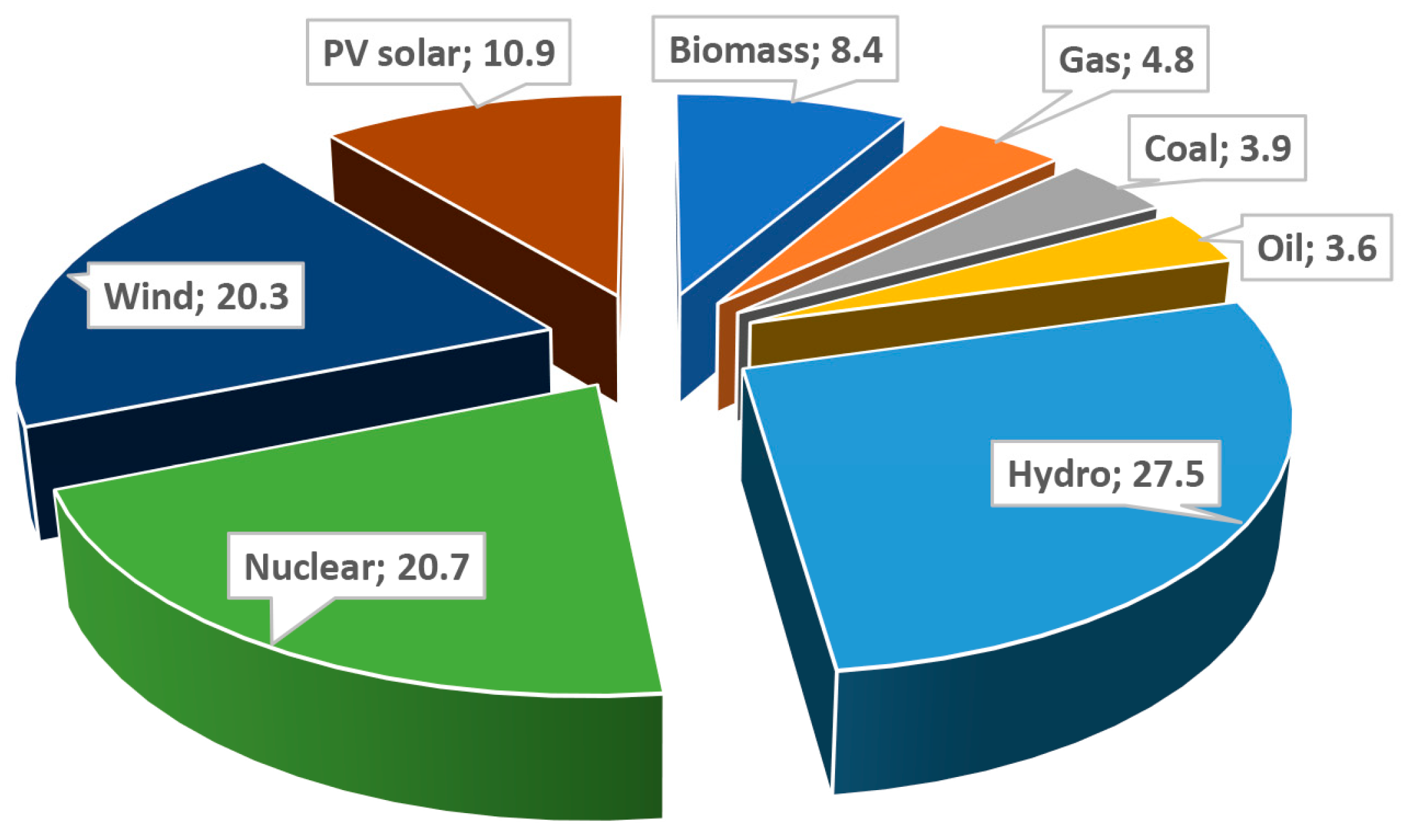

2.4. Construction of the DI Decarbonization Index

- –

- for stimulants:

- –

- for destimulants:

2.5. Cumulative Decarbonization Index

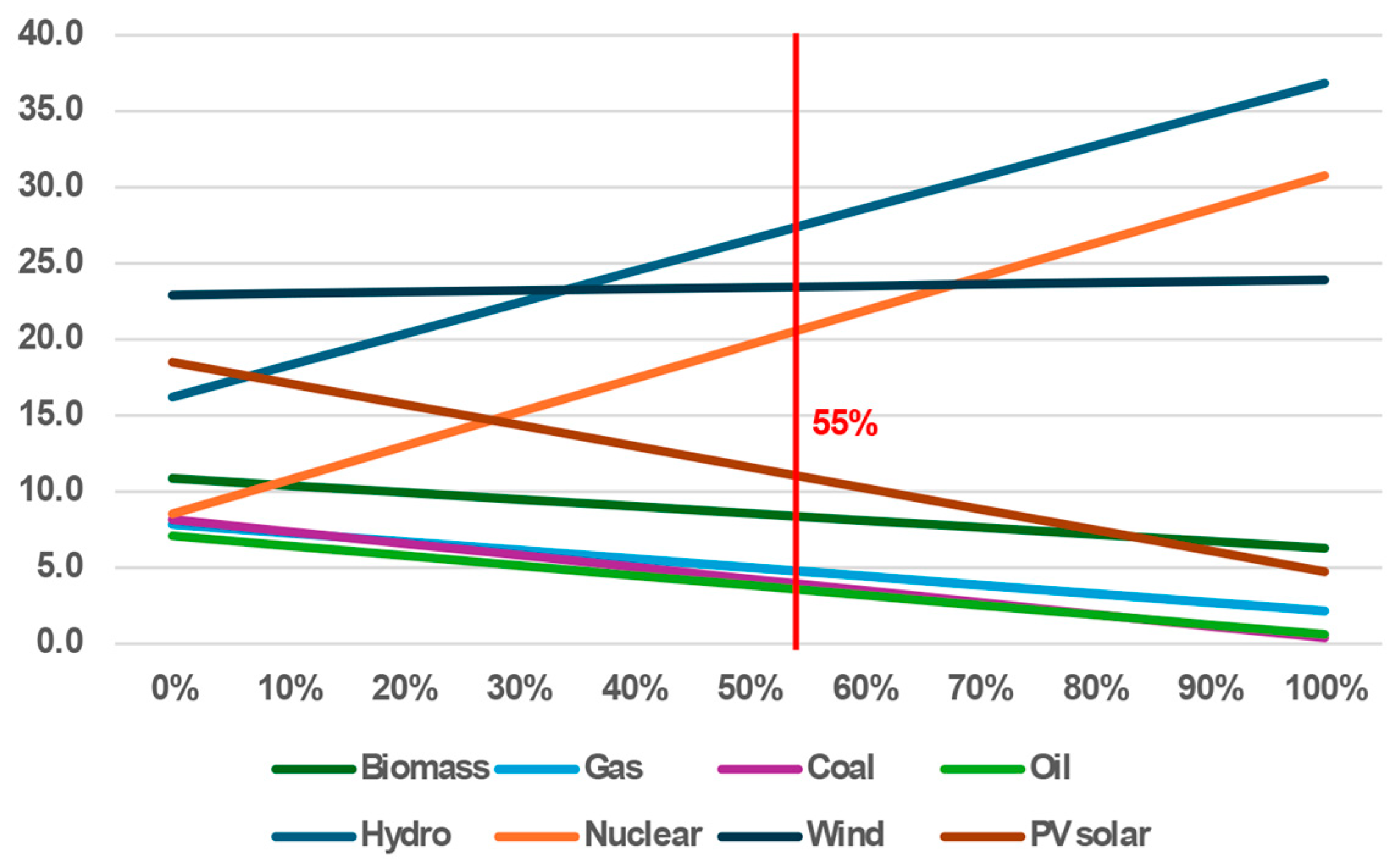

3. Analysis of Results

4. Summary and Final Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. Earth Summit 1992. Organizers: UNCED. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20010405223601/http://www.un.org/geninfo/bp/enviro.html (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetailsIII.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=XXVII-7&chapter=27&Temp=mtdsg3&clang=_en (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Agenda 21. Encyklopedia Zarządzania 2025. Available online: https://mfiles.pl/pl/index.php/Agenda_21 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Convention on Biological Diversity. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-8&chapter=27 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- What Is the Kyoto Protocol? United Nations Climate Change. Available online: https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Corporate Finance Institute. Available online: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/esg/kyoto-protocol (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- COP 21–UNFCCC. Framework Convention on Climate Change. Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Twenty-First Session Held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015. 2016. Available online: https://unfccc.int/event/cop-21 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- United Nations. The Paris Agreement. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/paris-agreement (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Zielony Ład: Klucz do Neutralnej Klimatycznie i Zrównoważonej UE. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pl/article/20200618STO81513/zielony-lad-klucz-do-neutralnej-klimatycznie-i-zrownowazonej-ue (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Europejski Zielony Ład. Aspirowanie do Miana Pierwszego Kontynentu Neutralnego dla Klimatu. Komisja Europejska. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_pl (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Parlament Europejski. Reforma Systemu Handlu Uprawnieniami do Emisji CO2 w Pigułce. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pl/article/20170213STO62208/reforma-systemu-handlu-uprawnieniami-do-emisji-co2-w-pigulce (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Climate Change: Parliament Extends the Market Stability Reserve to 2030. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/pl/press-room/20230310IPR77241/climate-change-parliament-extends-the-market-stability-reserve-to-2030 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Walka z Ucieczką Emisji: Powstrzymywanie Firm Przed Omijaniem Przepisów. Parlament Europejski. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pl/article/20210303STO99110/walka-z-ucieczka-emisji-powstrzymywanie-firm-przed-omijaniem-przepisow (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Ograniczanie Emisji Gazów Cieplarnianych w UE: Krajowe Cele na 2030 r. Rozporządzenie ws. Rocznych Wiążących Ograniczeń Emisji Gazów Cieplarnianych. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pl/article/20180208STO97442/ograniczanie-emisji-gazow-cieplarnianych-w-ue-krajowe-cele-na-2030-r (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Walka ze Zmianą Klimatu: Lepsze Wykorzystanie Lasów UE do Pochłaniania Dwutlenku Węgla. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pl/article/20170711STO79506/zmiana-klimatu-lepsze-wykorzystanie-lasow-ue-do-pochlaniania-dwutlenku-wegla (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Redukcja Emisji CO2 z Samochodów Osobowych i Dostawczych: Wyjaśniamy Nowe Cele. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pl/article/20180920STO14027/redukcja-emisji-co2-z-samochodow-osobowych-i-dostawczych-wyjasniamy-nowe-cele (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Redukcja Emisji z Samolotów i Statków: Działania UE. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pl/article/20220610STO32720/redukcja-emisji-z-samolotow-i-statkow-dzialania-ue (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Alternatywne Paliwa do Samochodów: Jak Zwiększyć Ich Wykorzystanie? Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pl/article/20221013STO43019/alternatywne-paliwa-do-samochodow-jak-zwiekszyc-ich-wykorzystanie (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Oszczędzanie Energii: Działania UE dla Zmniejszenia Zużycia Energii. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pl/article/20221128STO58002/oszczedzanie-energii-dzialania-ue-dla-zmniejszenia-zuzycia-energii (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Jak UE Wspiera Energię Odnawialną? Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pl/article/20221128STO58001/jak-ue-wspiera-energie-odnawialna (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Saaty, T.L. Fundamentals of Decision Making and Priority Theory with the Analytic Hierarchy Process, 2nd ed.; RWS Publications: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Prusak, A.; Stefanów, P. Badania nad właściwościami operacyjnymi metody AHP. Folia Oeconomica Cracoviensia 2011, 52, 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bascetin, A. The study of decision making tools for equipment selection in mining engineering operations. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. 2009, 25, 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sobczyk, E.J. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Multivariate Statistical Analysis (MSA) in Evaluating Mining Difficulties in Coal Mines. New Challenges and Visions for Mining. In Proceedings of the 21st World Mining Congress and Expo, Cracow (Congress), Katowice, Poland, 7–11 September 2008; CRC Press: London, UK, 2008; p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- Sobczyk, E.J.; Galica, D.; Kopacz, M.; Sobczyk, W. Selecting the optimal exploitation option using a digital deposit model and the AHP. Resour. Policy 2022, 78, 102952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczyk, E.J.; Kaczmarek, J.; Fijorek, K.; Kopacz, M. Efficiency and financial standing of coal mining enterprises in Poland in terms of restructuring course and effects. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. 2020, 40, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwanek-Bąk, B.; Sobczyk, W.; Sobczyk, E.J. Support for Multiple Criteria Decisions for Mineral Deposits Valorization and Protection. Resour. Policy 2020, 68, 107795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malanchuk, Y.; Moshynskyi, V.; Khrystyuk, A.; Malanchuk, Z.; Korniyenko, V.; Zhomyruk, R. Modelling mineral reserve assessment using discrete kriging methods. Min. Miner. Depos. 2024, 18, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M. Adaptive AHP: A review of marketing applications with extensions. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 872–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wind, Y.; Saaty, T.L. Marketing applications of the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Manag. Sci. 1980, 26, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberatore, M.J.; Nydick, R.L. The analytic hierarchy process in medical and health. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2008, 189, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedrawa, A.; Sobczyk, W. AHP—Komputerowe wspomaganie podejmowania złożonych decyzji. Rocz. Nauk. Eduk.-Tech. Inform. 2010, 1, 285–291. [Google Scholar]

- Sobczyk, W.; Kowalska, A.; Sobczyk, E.J. Wykorzystanie wielokryterialnej metody AHP i macierzy Leopolda do oceny wpływu eksploatacji złóż żwirowo-piaskowych na środowisko przyrodnicze doliny Jasiołki. Miner. Resour. Manag. 2014, 30, 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Adamus, W.; Łasak, P. Zastosowanie metody AHP do wyboru umiejscowienia nadzoru nad rynkiem finansowym. Bank. Kredyt 2010, 41, 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Pohekar, S.D.; Ramachandran, M. Application of multi-criteria decision making to sustainable energy planning—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2004, 8, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afgan, N.H.; Carvalho, M.G. Multi-criteria assessment of new and renewable Energy power plants. Energy 2002, 27, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipto, A.S.; Al Bari, M.A.; Nabil, S.T. Sustainability Analysis of Different Types of Power Plants Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Methods. J. Eng. Adv. 2020, 01, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M.; Scheffran, J.; Böhner, J.; Mohamed, S.; Elsobki, M.S. Sustainability Assessment of Electricity Generation Technologies in Egypt Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Energies 2018, 11, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzimouratidis, A.I.; Pilavachi, P.A. Multicriteria evaluation of power plants impact on the living standard using the analytic hierarchy process. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 1074–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promentilla, M.A.B.; Aviso, K.B.; Tan, R.R. A fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (FAHP) approach for optimal selection of low-carbon energy technologies. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2015, 45, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwiec, D.; Pacana, A. Analiza emisji zanieczyszczeń sektora energetyczno-przemysłowego z wykorzystaniem rozmytego analitycznego procesu hierarchicznego i metody TOPSIS. Stud. Mater. 2020, 2, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczyk, E.J.; Kulpa, J.; Kopacz, M.; Salamaga, M.; Sobczyk, W. Sustainable management of hard coal resources implemented by identifying risk factors in the mining process. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. 2024, 40, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Dua, R.; Almutairi, S.; Bansal, P. Emerging energy economics and policy research priorities for enabling the electric vehicle sector. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 1836–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goepel, K.D. Implementing the Analytic Hierarchy Process as a Standard Method for Multi-Criteria Decision Making in Corporate Enterprises—A New AHP Excel Template with Multiple Inputs. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Analytic Hierarchy Process, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 23–26 June 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/ (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Available online: https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.oecd-nea.org/lcoe/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.statista.com (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Available online: https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/energy-outlook/bp-energy-outlook-2024.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- European Electricity Review 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Electricity_and_heat_statistics (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Available online: https://ember-energy.org/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Available online: https://enmin.lrv.lt/en/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Tokarski, S. Suwerenność energetyczna w polityce europejskiej i krajowej. Energetyka Rozproszona 2023, 9, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polityka Energetyczna Polski (PEP). Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/polityka-energetyczna-polski (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Available online: https://naukaoklimacie.pl/ (accessed on 16 August 2025).

| Technical Aspects | Economic Aspects | Environmental Aspects | Social Aspects | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency Coefficient | Availability | Reserve to Production | Capacity | The LCOE | Changes in Fuel Cost | External Costs | Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions | PM Emissions | Land Required | Job Creation | Compensation Rates | Social Acceptance | |

| [%] | [%] | [Years] | [%] | USD/MWh | AHP Estimate | Eurocents/ kWh | kg CO2/MWh | mgCO2eq/kWh | km2/kW | Employees/ 500 MW | EUROcents/ kWh | AHP Estimate | |

| Biomass | 28 | 80 | ∞ | 59 | 61 | 0.34 | 2.65 | 30 | 269 | 5.2 | 36 | 2.65 | 10.9 |

| Gas | 39 | 91 | 47 | 14.7 | 92 | 0.43 | 2.00 | 640 | 34 | 0.04 | 2460 | 2.00 | 7.0 |

| Coal | 39.4 | 85.4 | 131 | 42.6 | 74 | 0.34 | 8.40 | 960 | 347 | 0.4 | 2500 | 8.40 | 4.4 |

| Oil | 37.5 | 92 | 55 | 8.5 | 95 | 0.43 | 6.75 | 690 | 128 | 0.4 | 2500 | 6.75 | 4.4 |

| Hydro | 80 | 50 | ∞ | 34.5 | 61 | 0 | 0.56 | 6 | 5 | 0.13 | 2500 | 0.56 | 14.6 |

| Nuclear | 33.5 | 96 | 70 | 92.3 | 110 | 0.23 | 0.49 | 15 | 2 | 0.01 | 2500 | 0.49 | 2.4 |

| Wind | 35 | 38 | ∞ | 34.3 | 42 | 0 | 0.16 | 11 | 20 | 0.79 | 5635 | 0.16 | 32.1 |

| PV solar | 17 | 20 | ∞ | 23.4 | 49 | 0 | 0.24 | 45 | 101 | 0.12 | 5370 | 0.24 | 24.1 |

| Technical Aspects | Economic Aspects | Environmental Aspects | Social Aspects | Decarbonization Index–DI | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency Coefficient | Availability | Reserve to Production | Capacity | The LCOE | Changes in Fuel Cost | External Costs | Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions | PM Emissions | Land Required | Job Creation | Compensation Rates | Social Acceptance | ||

| Weights | ||||||||||||||

| Level 2 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.55 | 0.09 | ||||||||||

| Level 3 | 0.16 | 0.51 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.65 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.71 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.64 | |

| Global weights | 0.023 | 0.073 | 0.035 | 0.010 | 0.046 | 0.052 | 0.028 | 0.388 | 0.126 | 0.033 | 0.009 | 0.022 | 0.055 | |

| Biomass | 28 | 80 | ∞ | 59 | 61 | 0.34 | 2.65 | 30 | 269 | 5.2 | 36 | 2.65 | 10.9 | 8.4 |

| Gas | 39 | 91 | 47 | 14.7 | 92 | 0.43 | 2.00 | 640 | 34 | 0.04 | 2460 | 2.00 | 7.0 | 4.8 |

| Coal | 39.4 | 85.4 | 131 | 42.6 | 74 | 0.34 | 8.40 | 960 | 347 | 0.4 | 2500 | 8.40 | 4.4 | 3.9 |

| Oil | 37.5 | 92 | 55 | 8.5 | 95 | 0.43 | 6.75 | 690 | 128 | 0.4 | 2500 | 6.75 | 4.4 | 3.6 |

| Hydro | 80 | 50 | ∞ | 34.5 | 61 | 0 | 0.56 | 6 | 5 | 0.13 | 2500 | 0.56 | 14.6 | 27.5 |

| Nuclear | 33.5 | 96 | 70 | 92.3 | 110 | 0.23 | 0.49 | 15 | 2 | 0.01 | 2500 | 0.49 | 2.4 | 20.7 |

| Wind | 35 | 38 | ∞ | 34.3 | 42 | 0 | 0.16 | 11 | 20 | 0.79 | 5635 | 0.16 | 32.1 | 20.3 |

| PV solar | 17 | 20 | ∞ | 23.4 | 49 | 0 | 0.24 | 45 | 101 | 0.12 | 5370 | 0.24 | 24.1 | 10.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sobczyk, E.J.; Sobczyk, W.; Olkuski, T.; Ciepiela, M. Assessing the Pace of Decarbonization in EU Countries Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Energies 2026, 19, 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010243

Sobczyk EJ, Sobczyk W, Olkuski T, Ciepiela M. Assessing the Pace of Decarbonization in EU Countries Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Energies. 2026; 19(1):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010243

Chicago/Turabian StyleSobczyk, Eugeniusz Jacek, Wiktoria Sobczyk, Tadeusz Olkuski, and Maciej Ciepiela. 2026. "Assessing the Pace of Decarbonization in EU Countries Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis" Energies 19, no. 1: 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010243

APA StyleSobczyk, E. J., Sobczyk, W., Olkuski, T., & Ciepiela, M. (2026). Assessing the Pace of Decarbonization in EU Countries Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Energies, 19(1), 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010243