Autoencoder-Based Missing Data Imputation for Enhanced Power Transformer Health Index Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

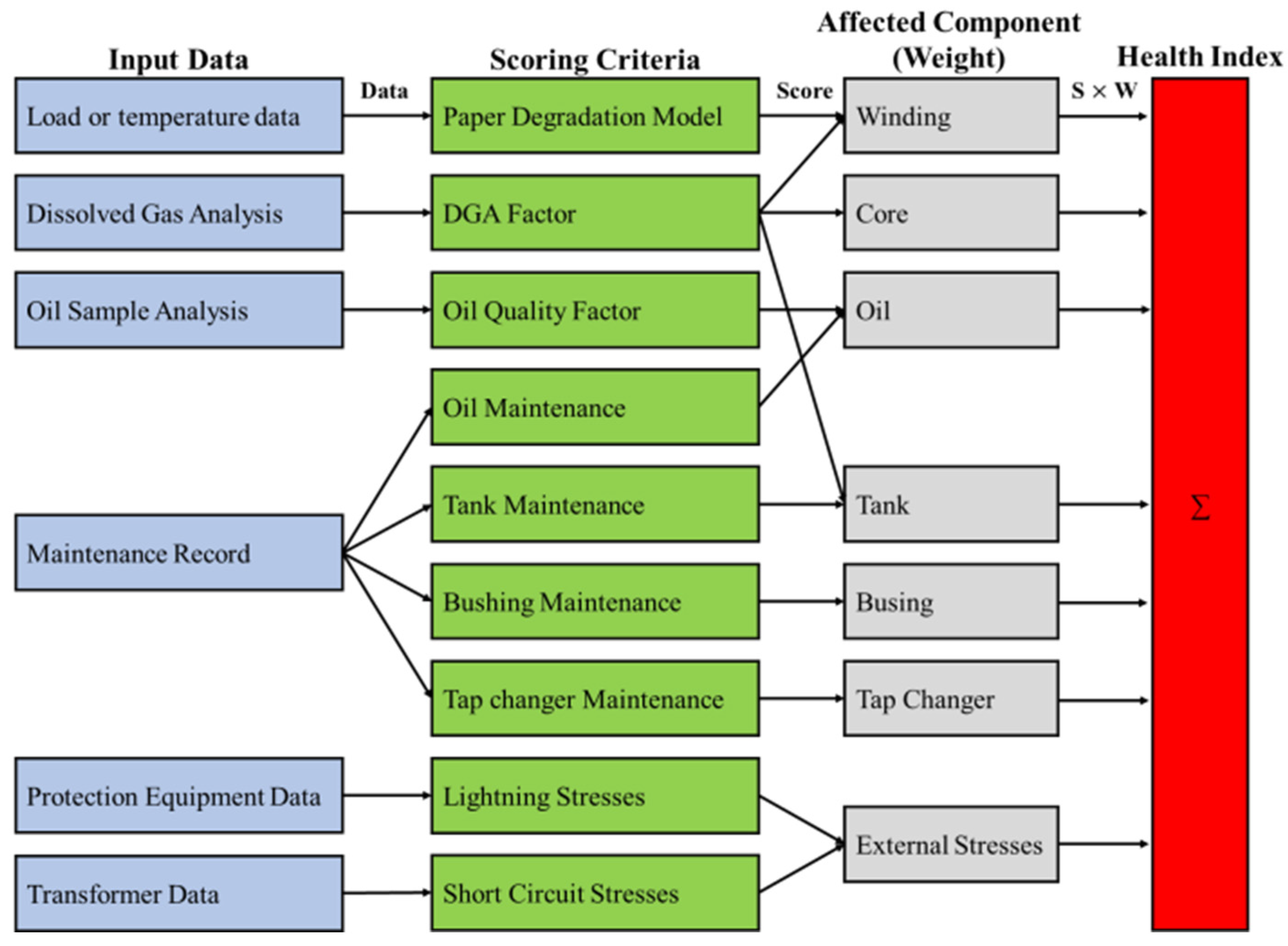

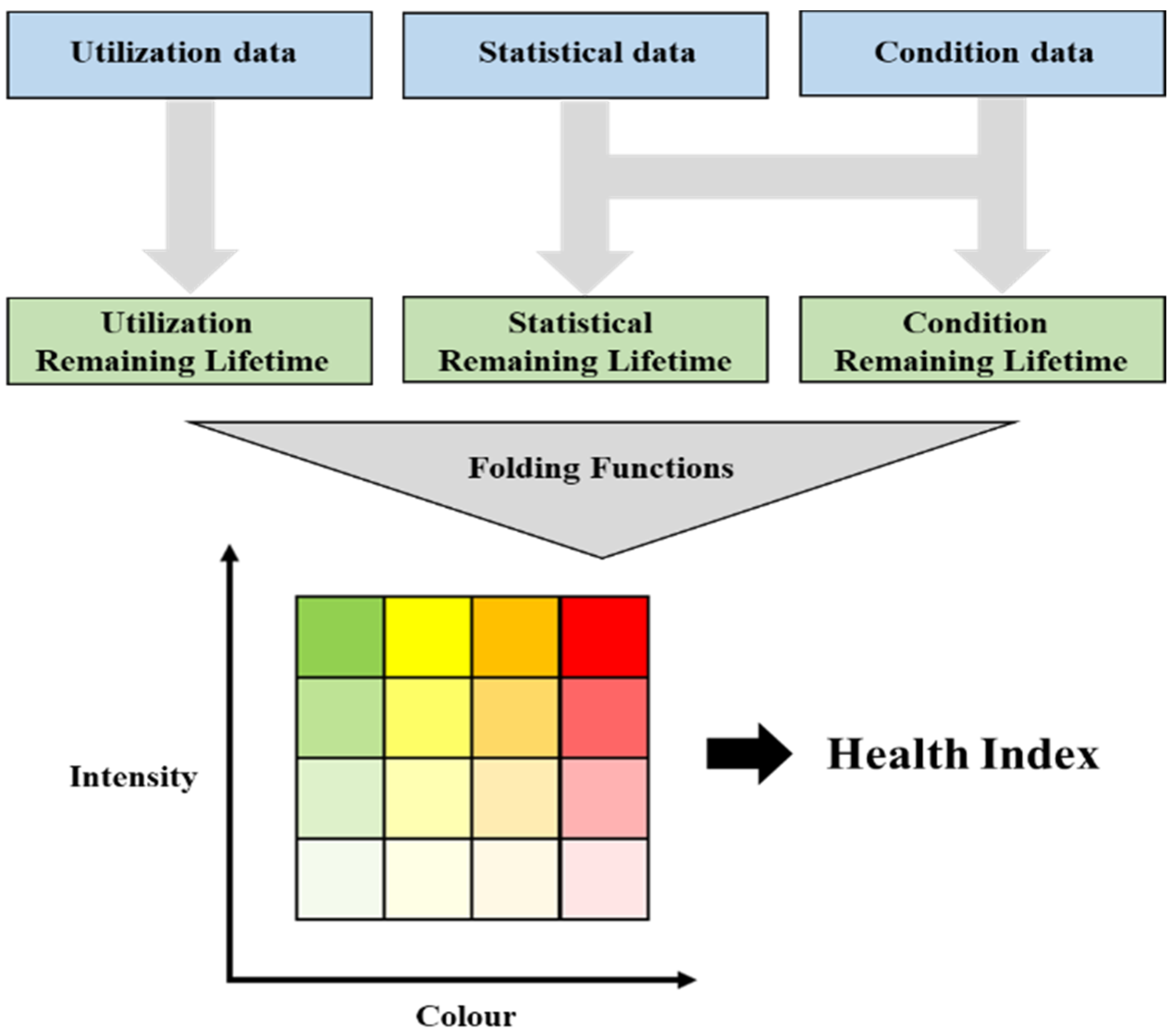

2. Input Parameter Section for the Transformer Evaluation Algorithm

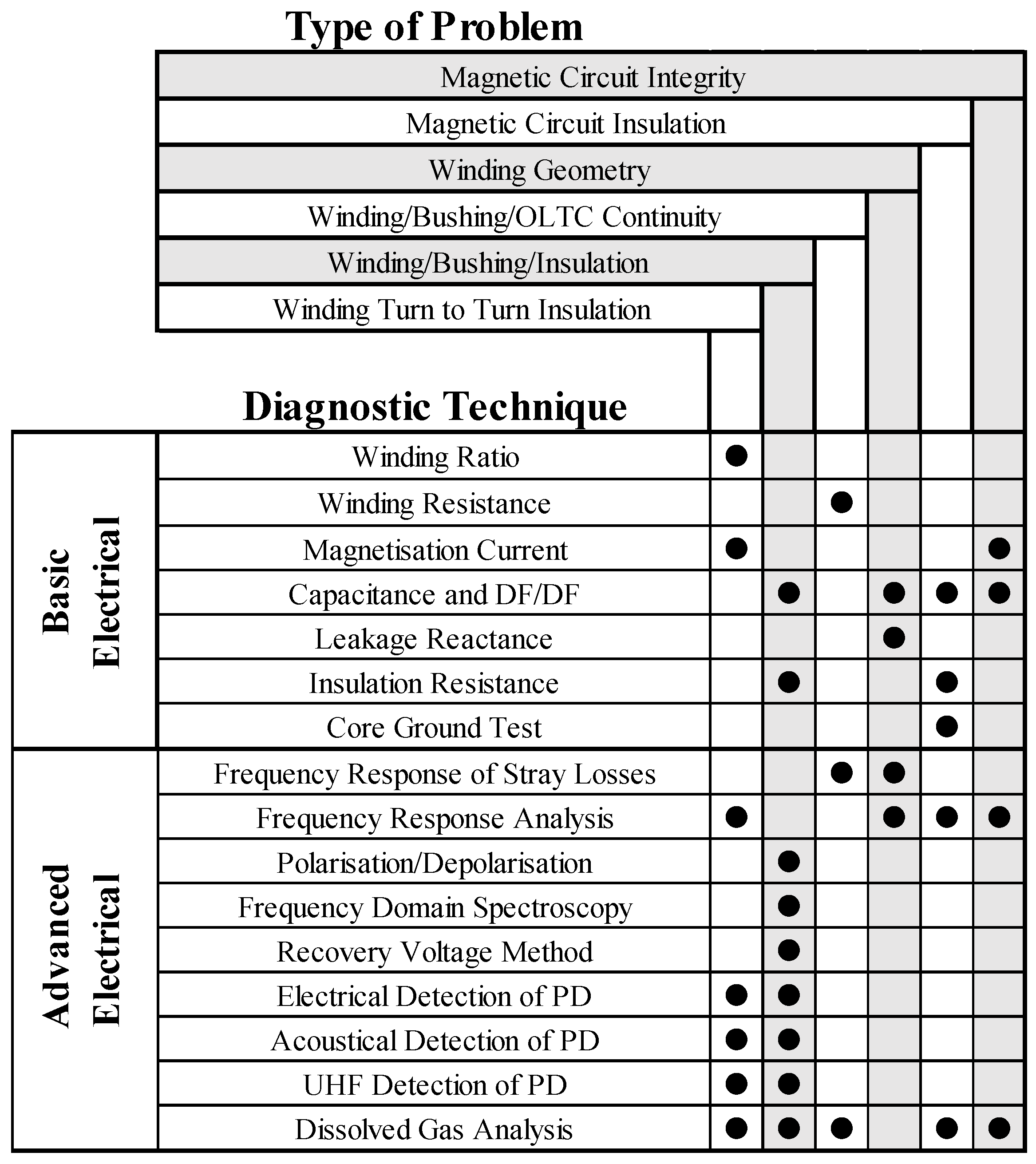

2.1. Power Transformer Failure Mode and Effect Analysis

2.2. Power Transformer Cross Matrix

2.3. Input Parameter Selection for the Proposed Transformer Health Index

3. Power Transformer Health Index Assessment Algorithm Based on Existing Machine Learning Models

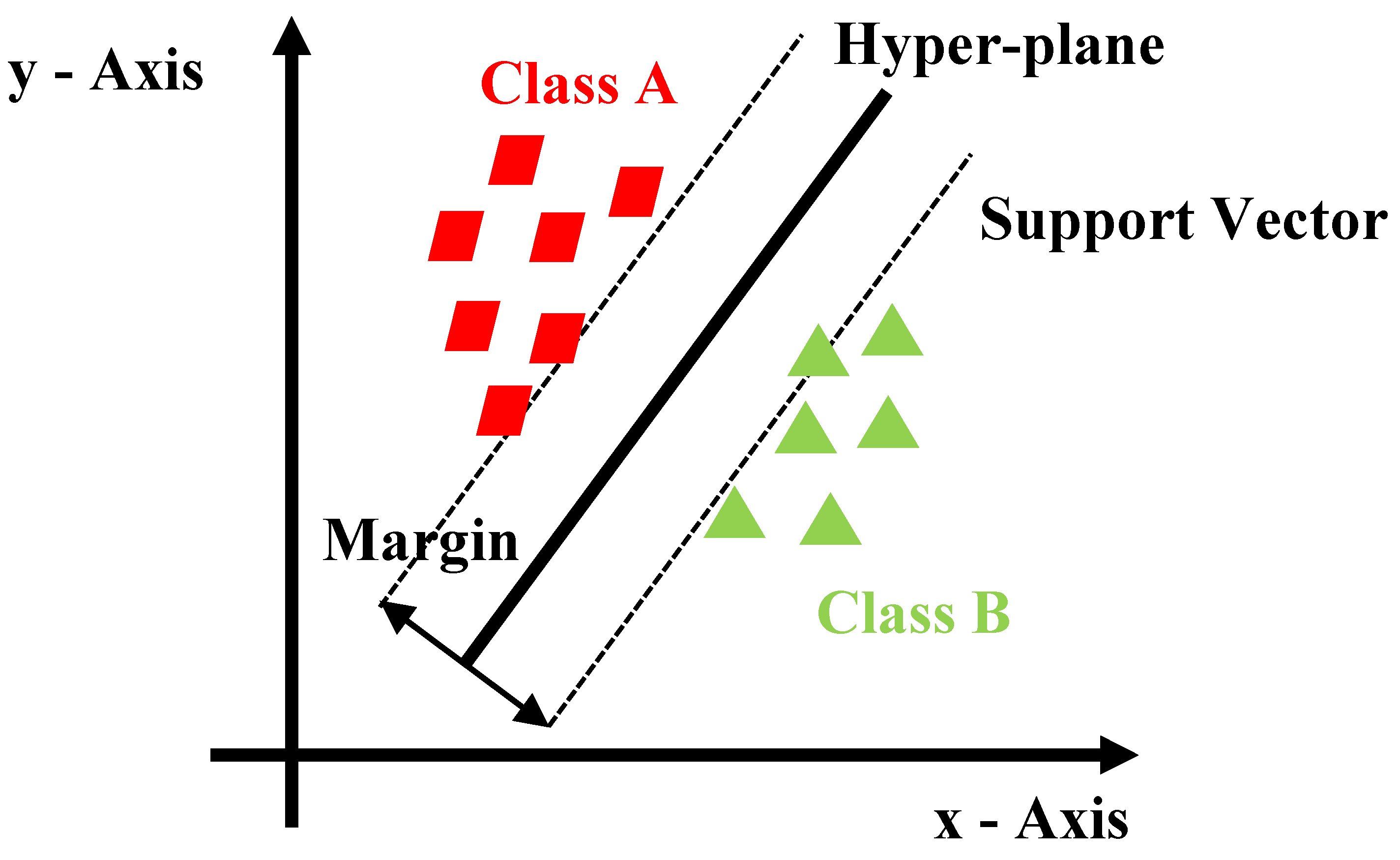

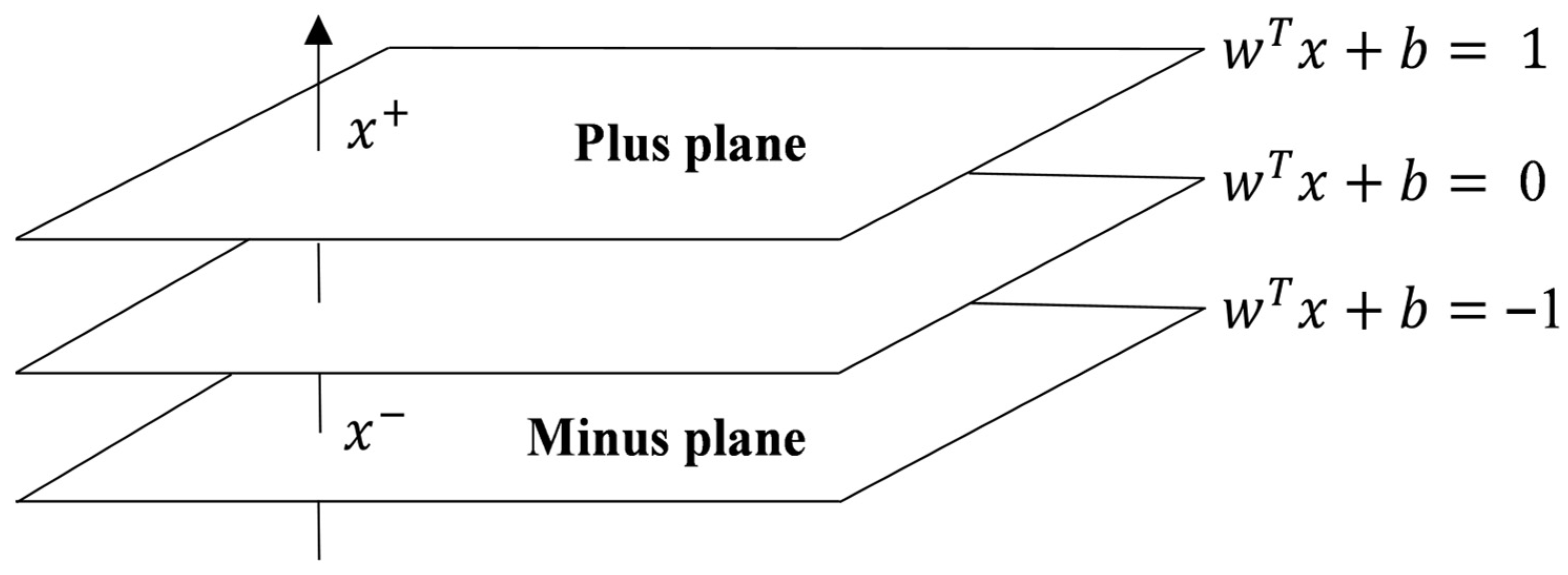

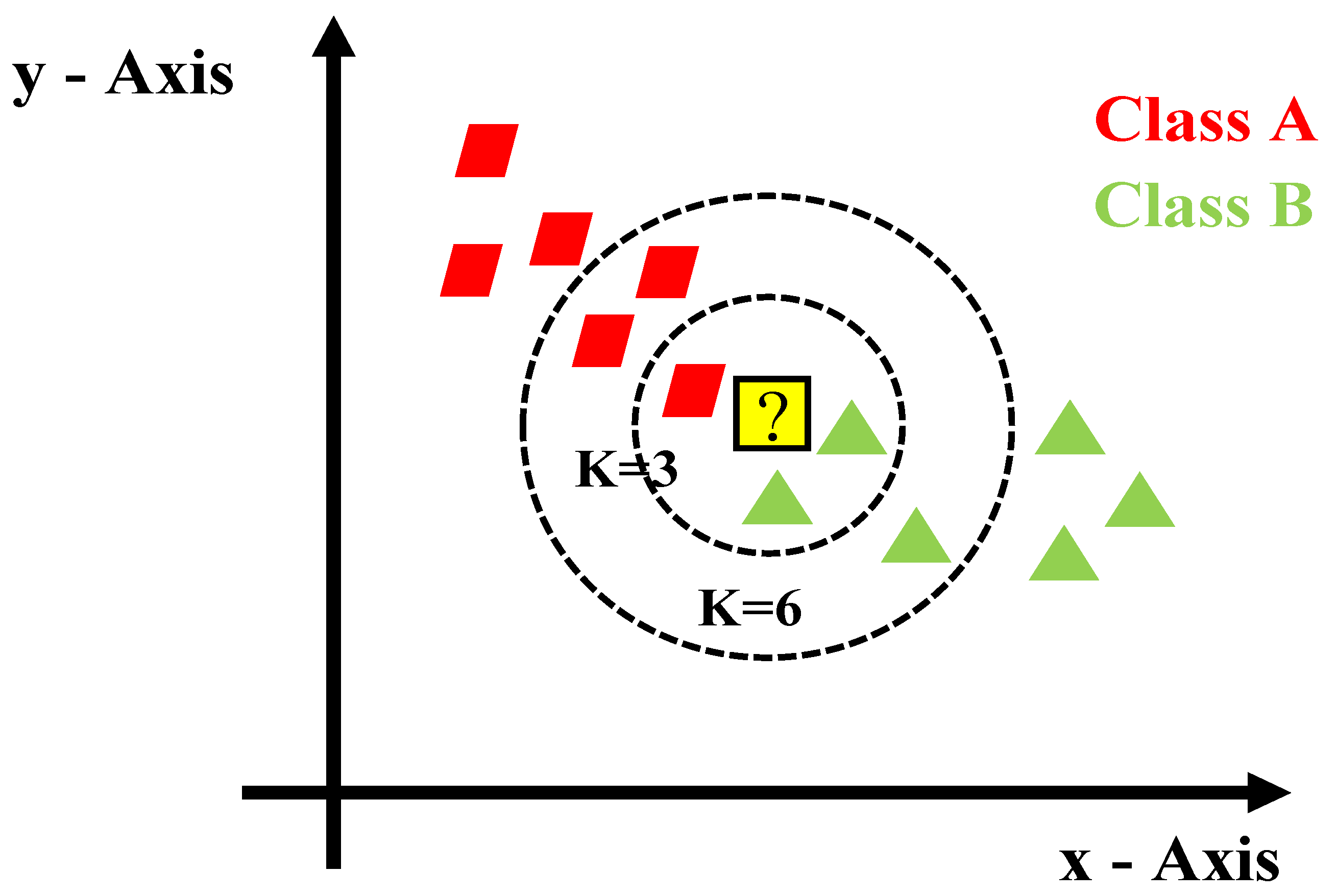

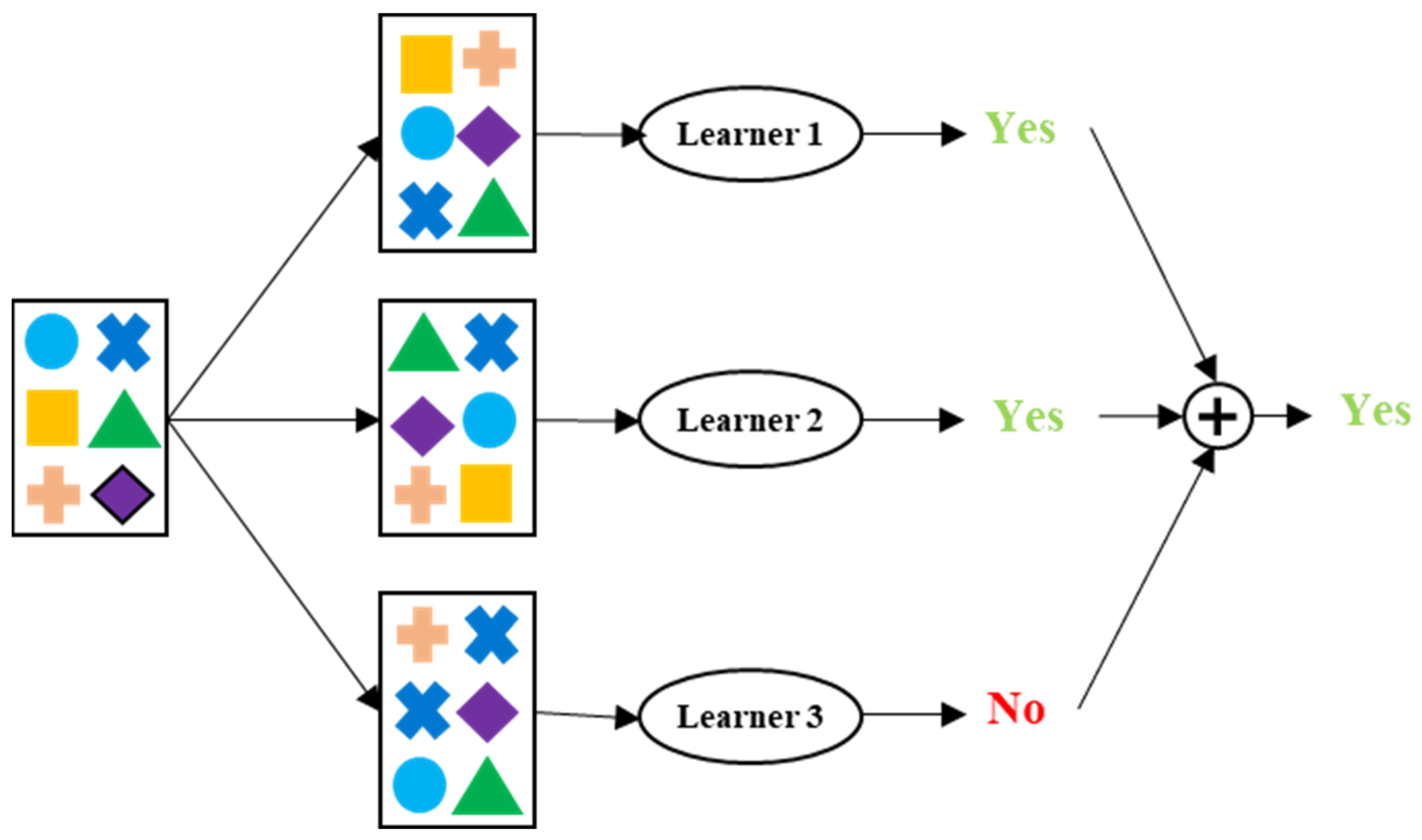

3.1. Machine Learning Model

3.2. Machine Learning-Based Power Transformer Health Assessment Algorithm

4. Effect of Missing Data in Machine Learning-Based Evaluations

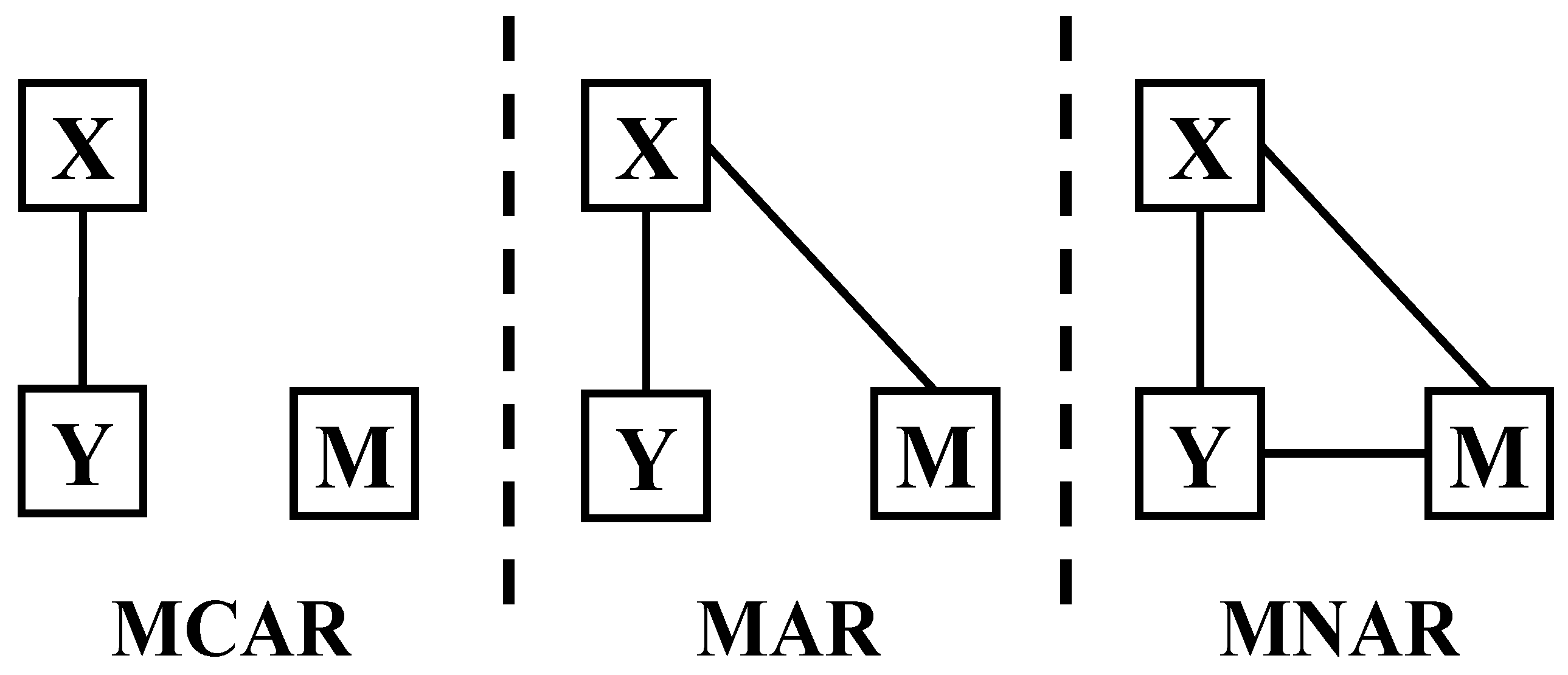

4.1. Missing Data Type

4.1.1. Missing Completely at Random

4.1.2. Missing at Random

4.1.3. Missing Not at Random

4.2. Existing Missing Data Compensation Methods and Performance Evaluation

5. Proposed Missing Data Compensation Method in This Study

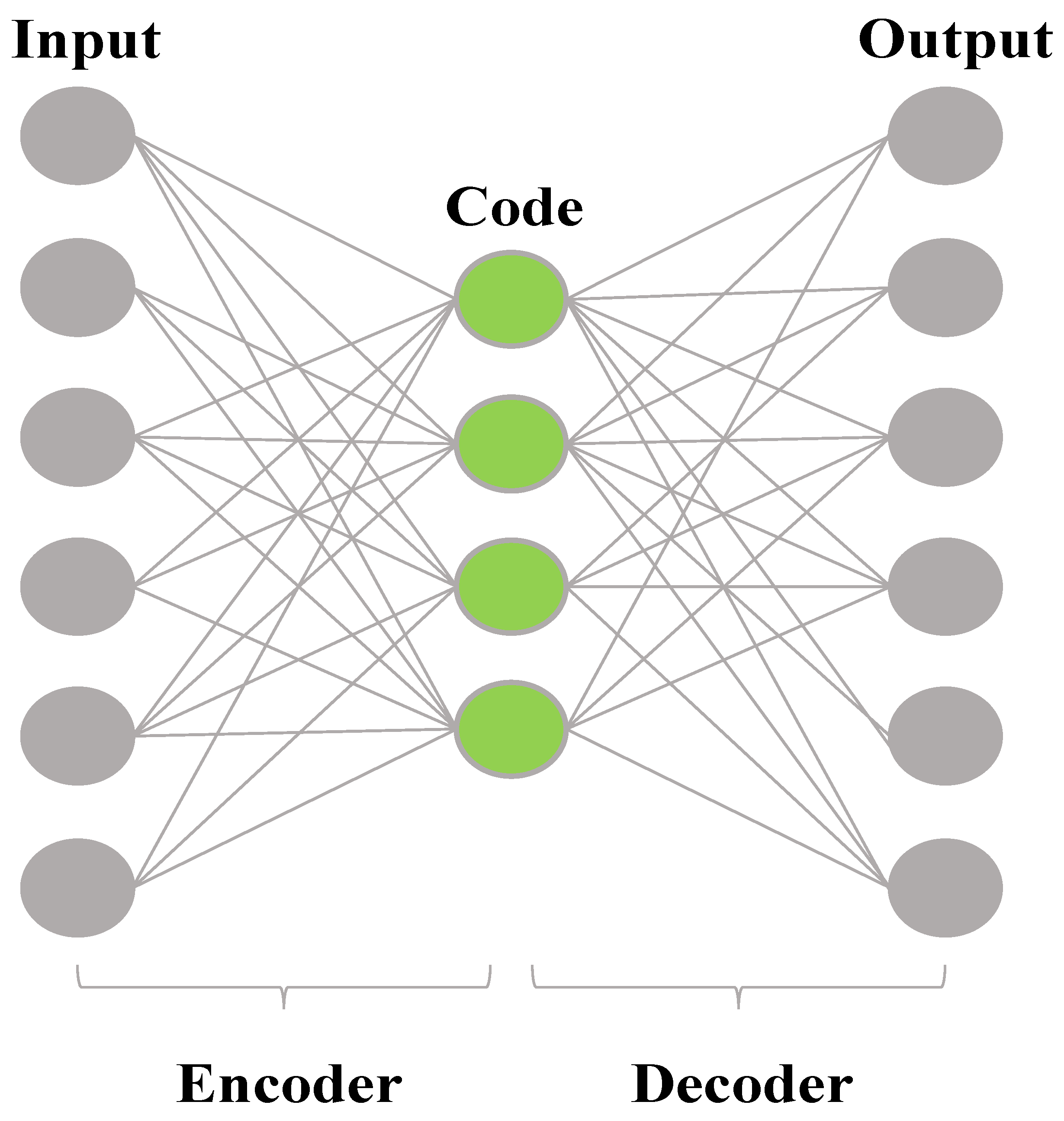

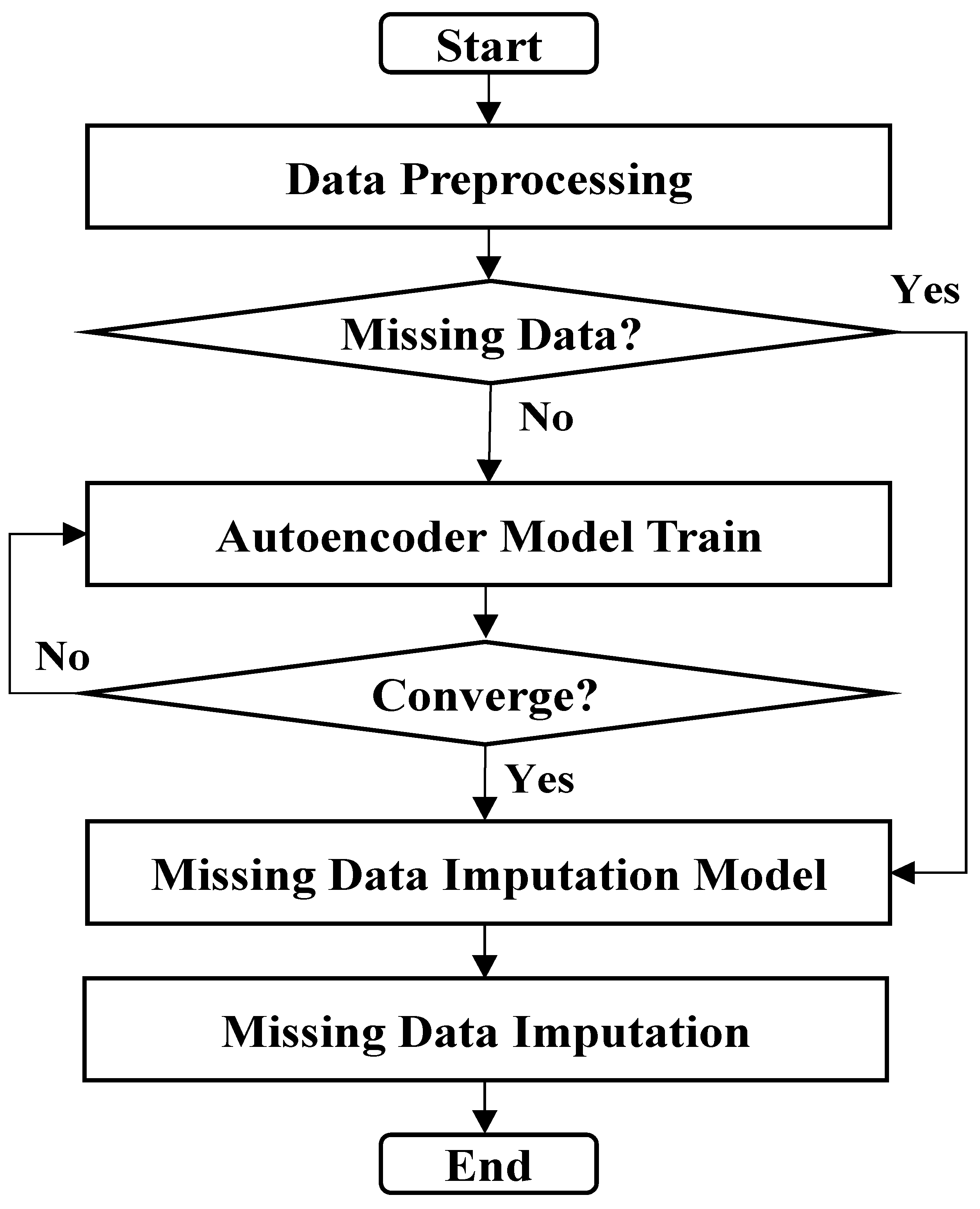

Missing Data Imputation Method and Procedures Using Our Autoencoder Methodology

6. Performance Evaluation of Missing Data Imputation Methods

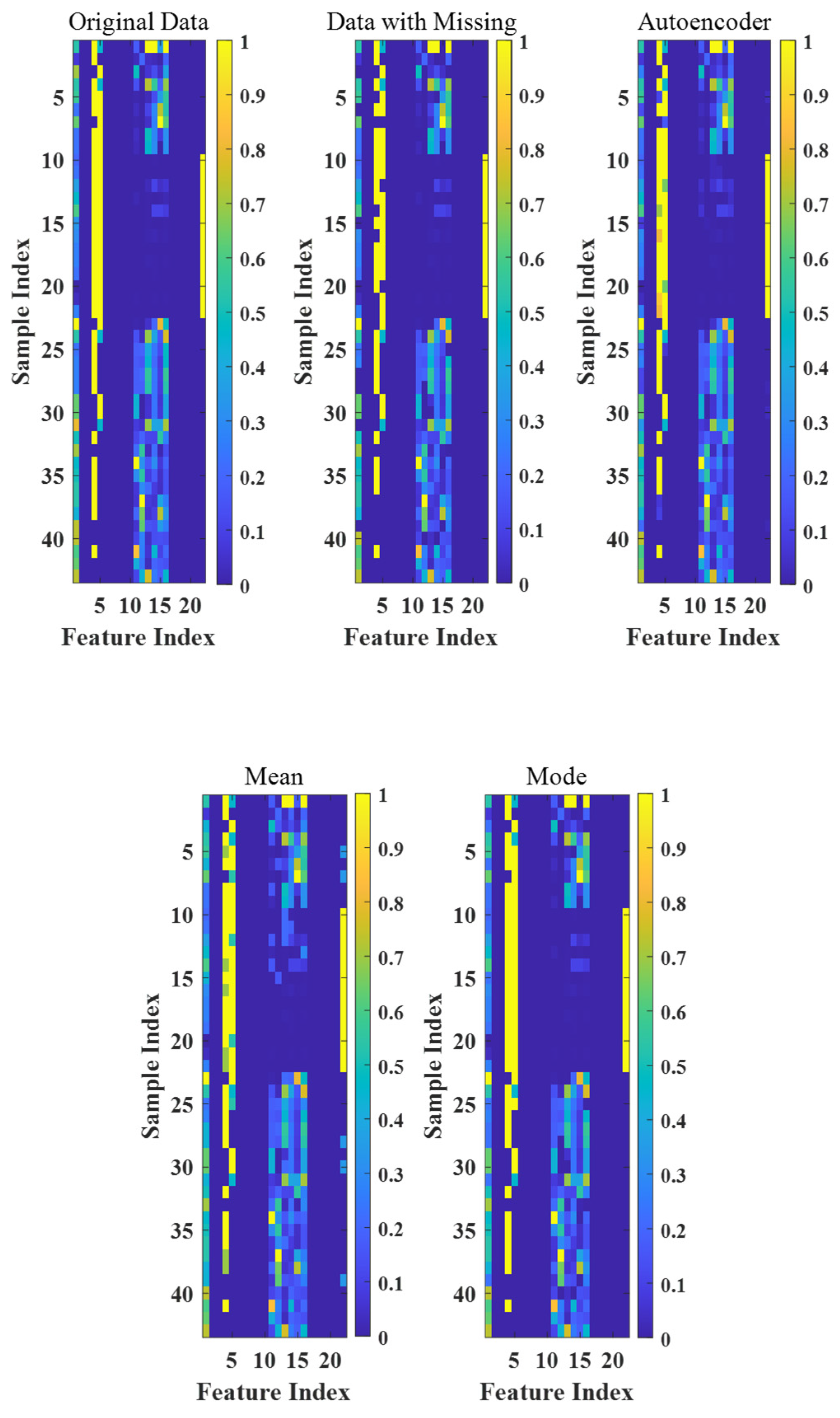

6.1. Data States

6.1.1. Original Data

6.1.2. Data with Missing Values

6.1.3. Autoencoder

6.1.4. Mean/Mode

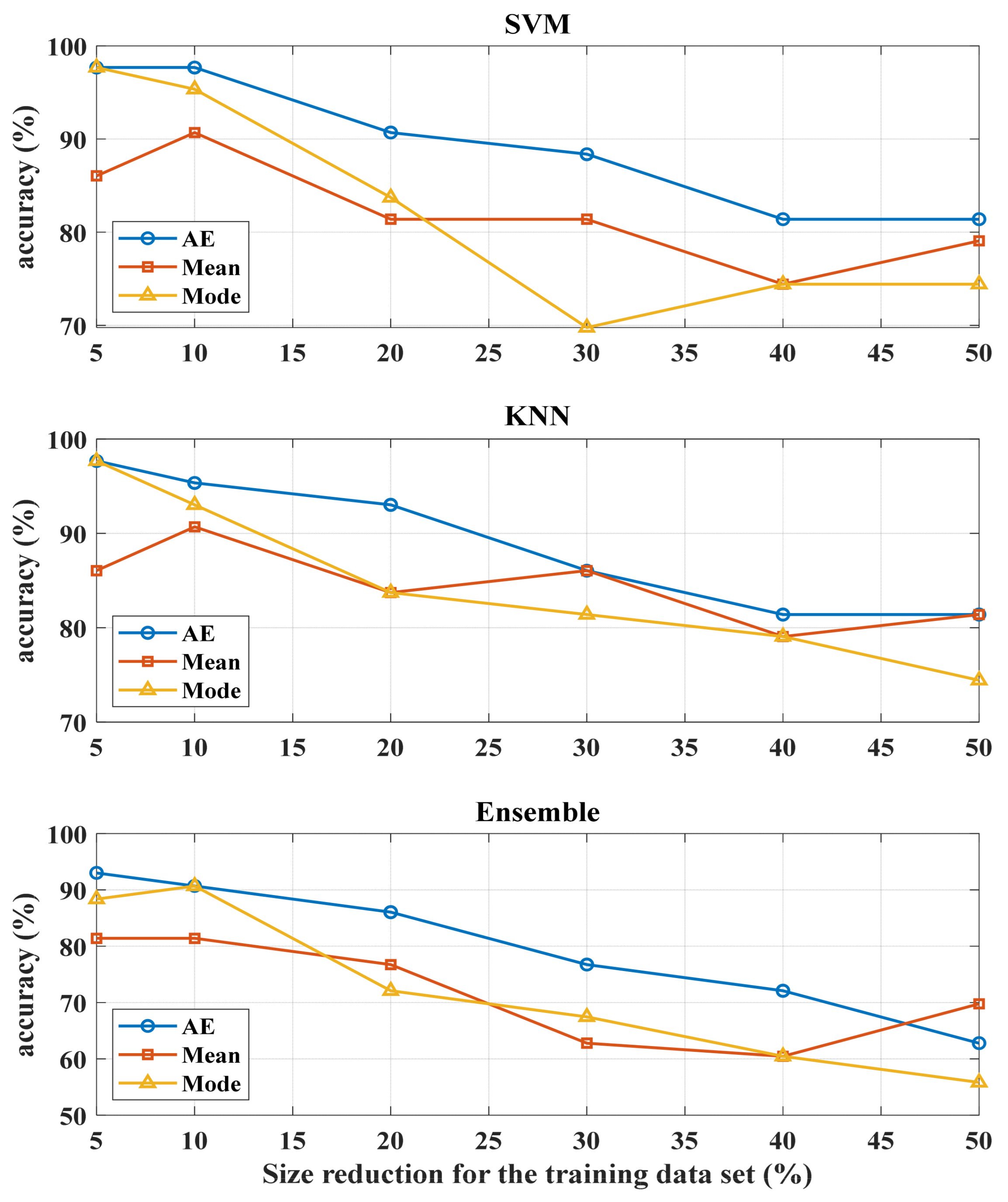

6.2. Results and Performance Analysis

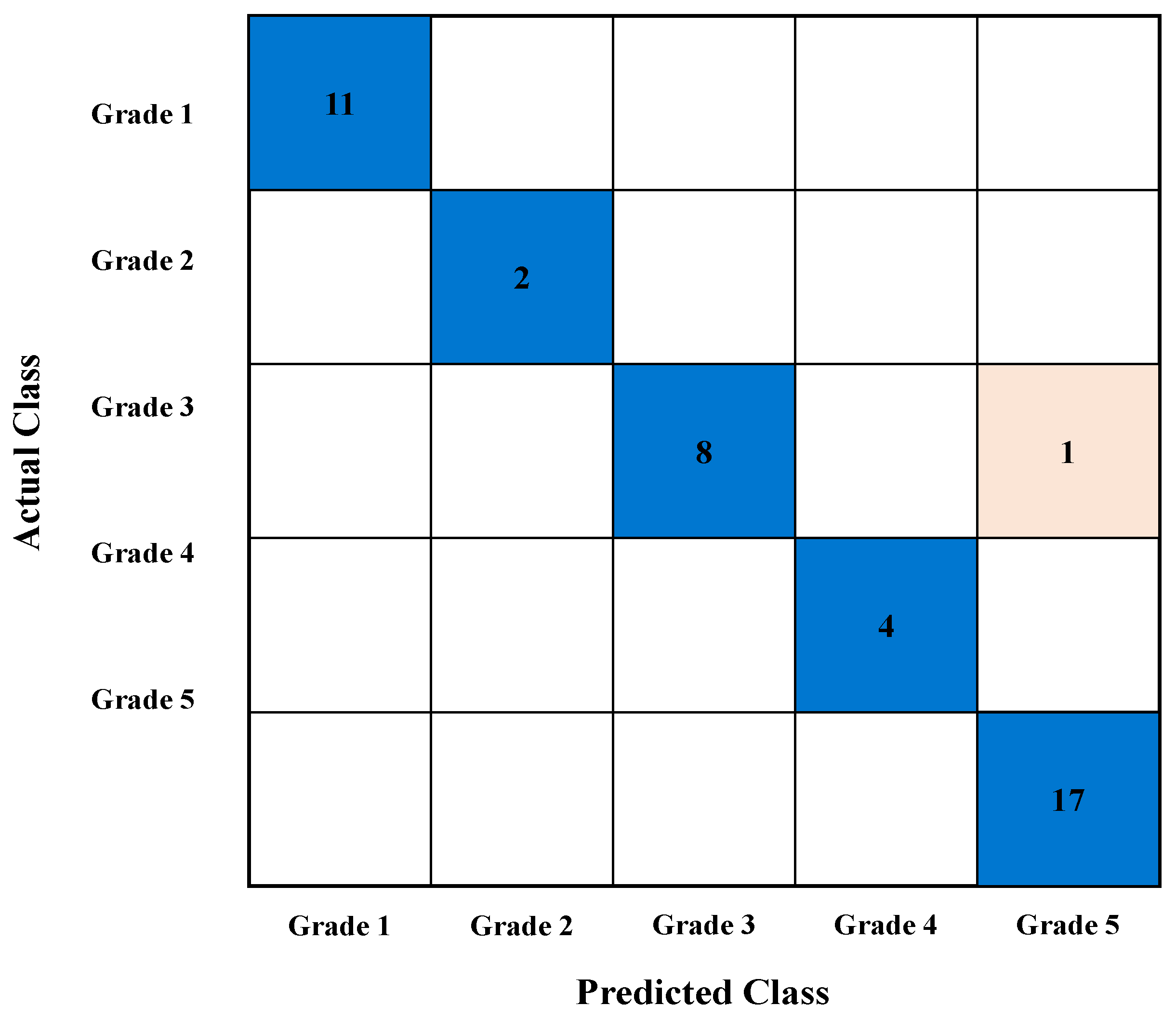

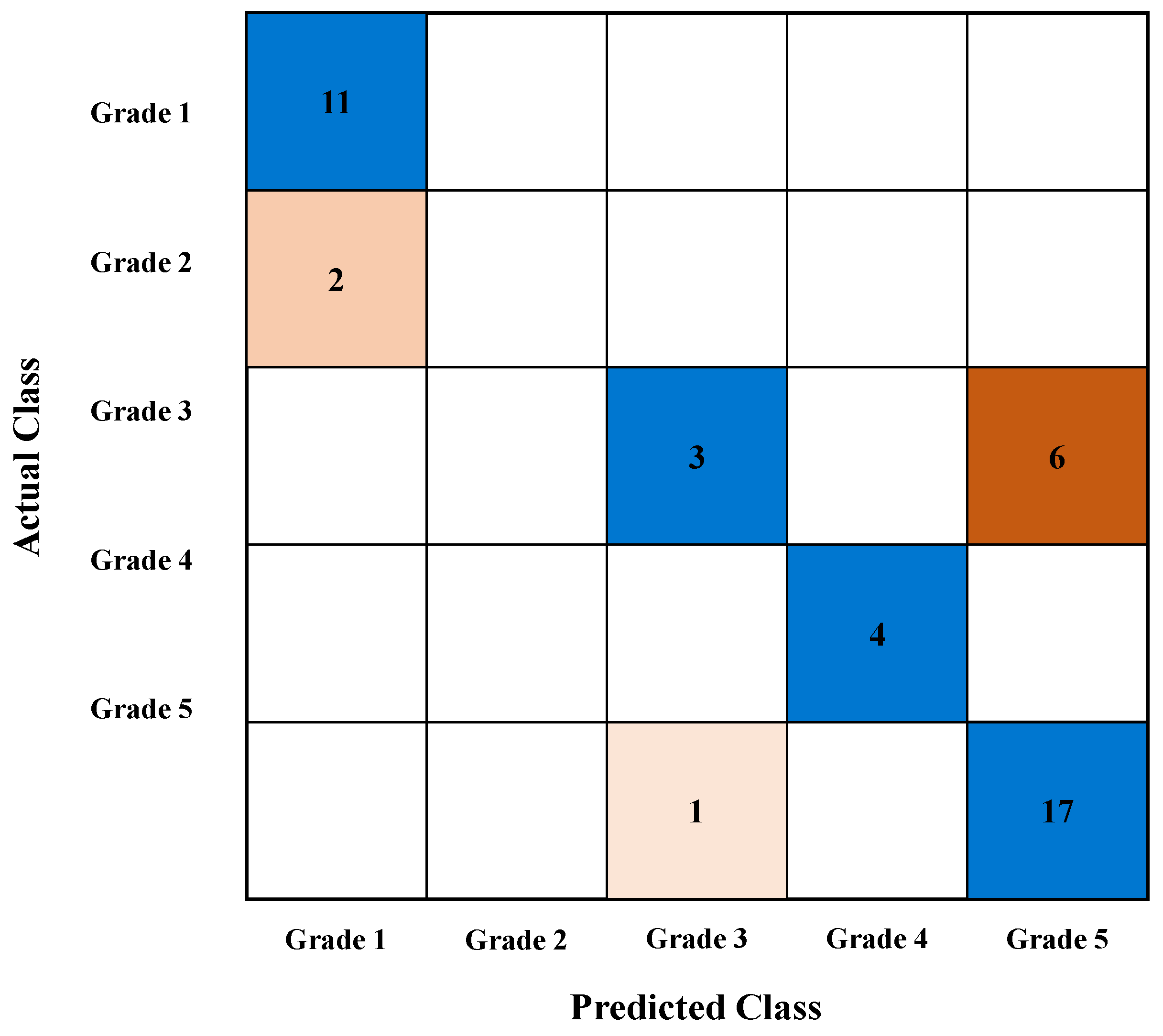

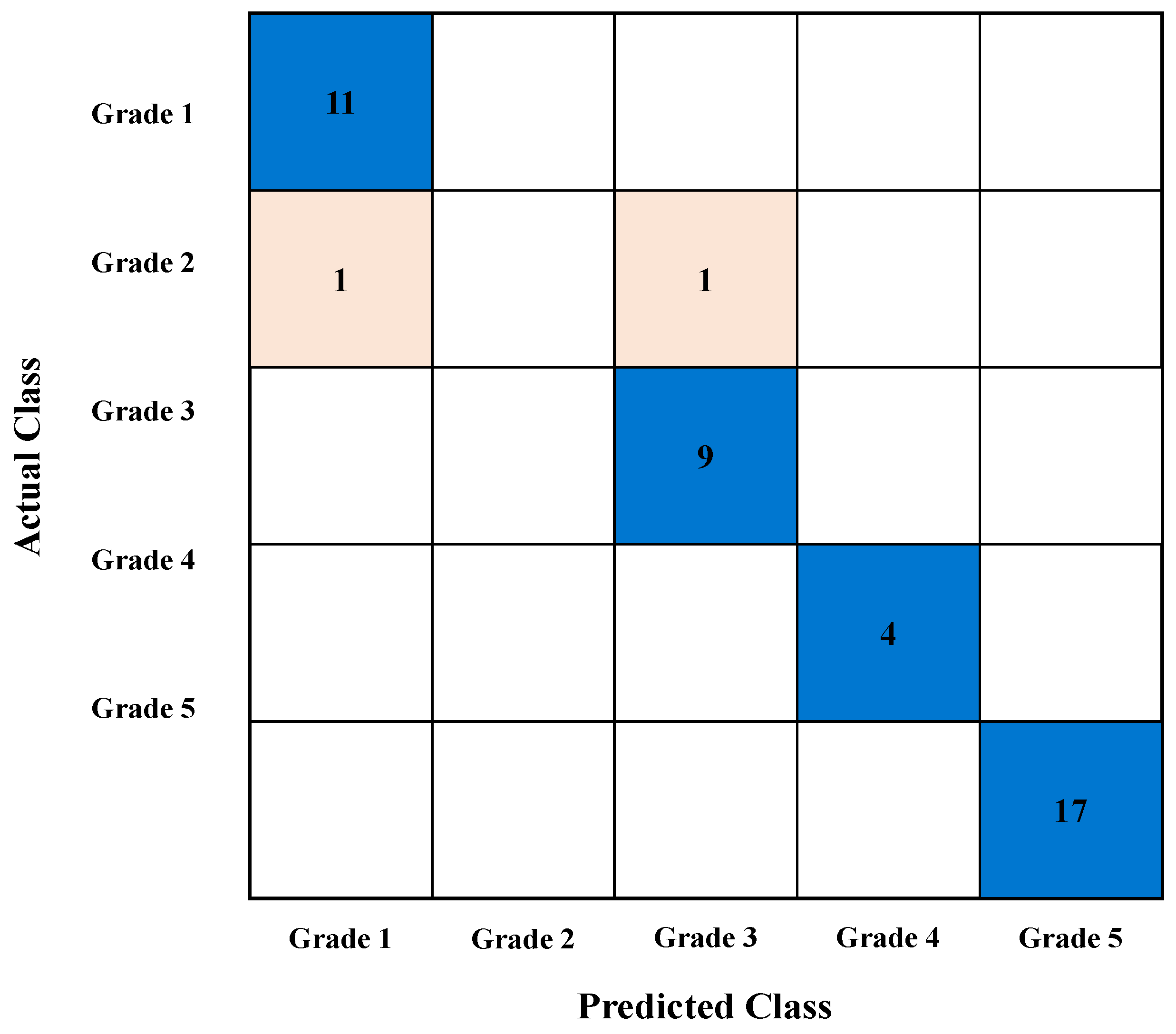

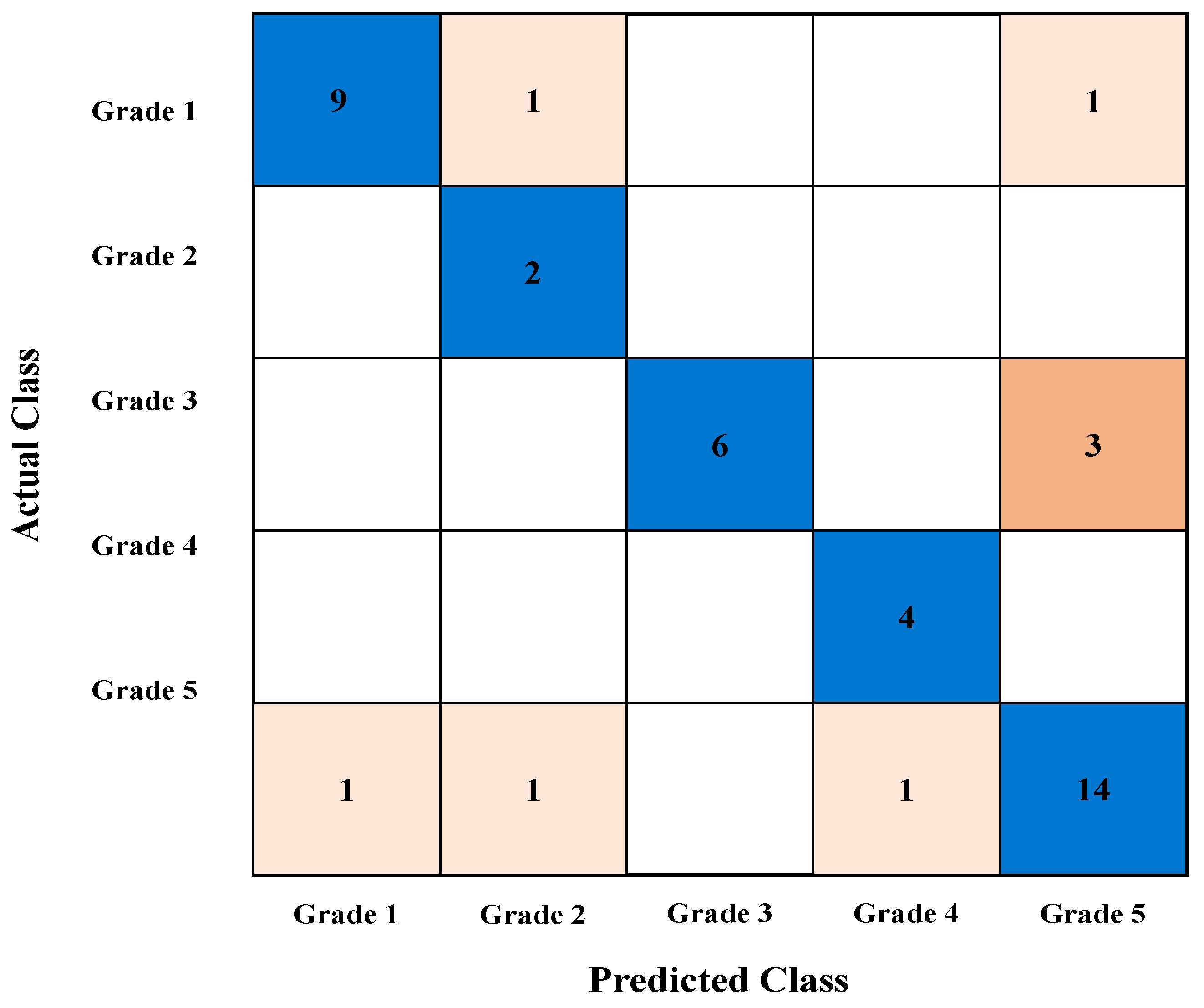

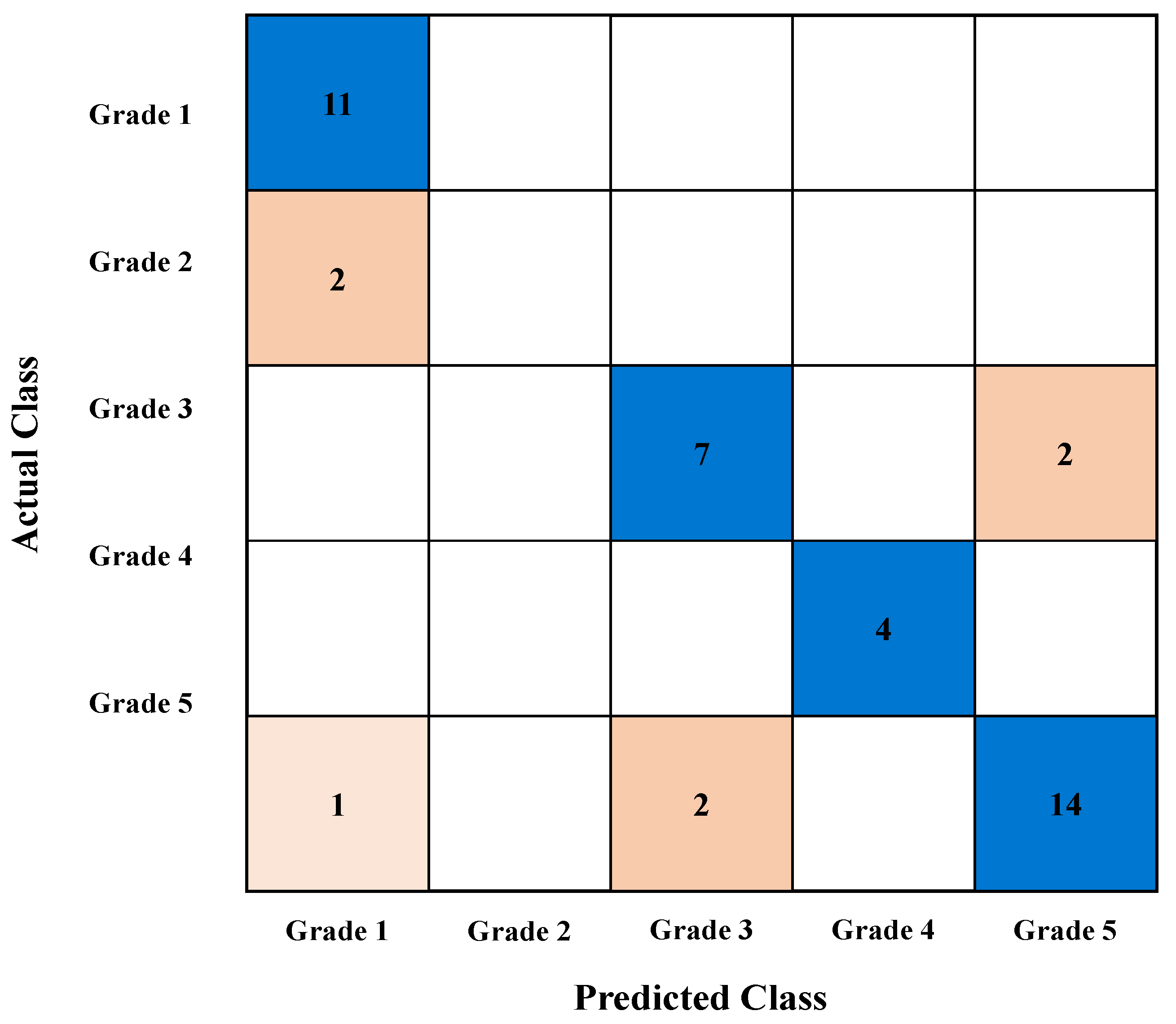

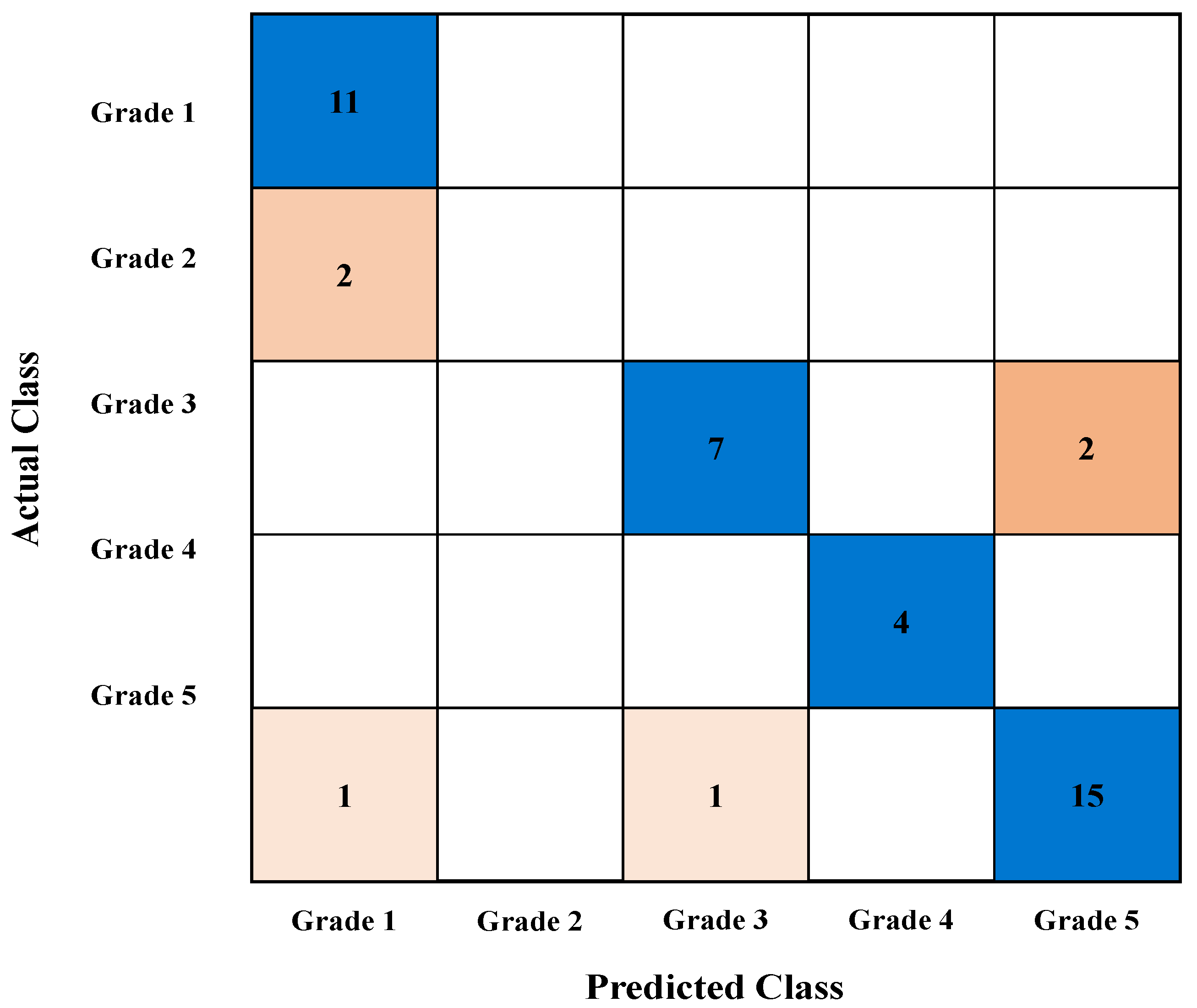

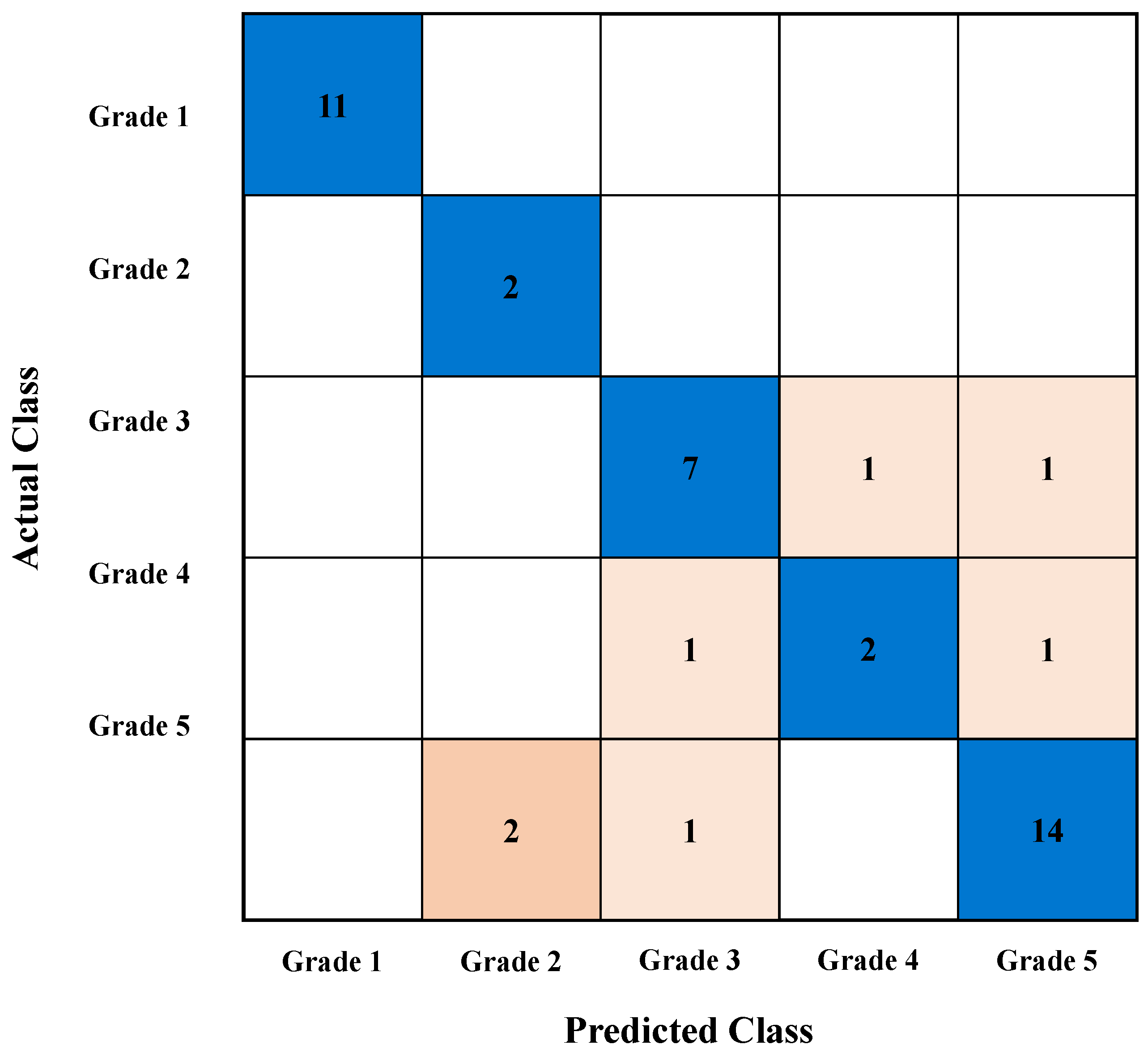

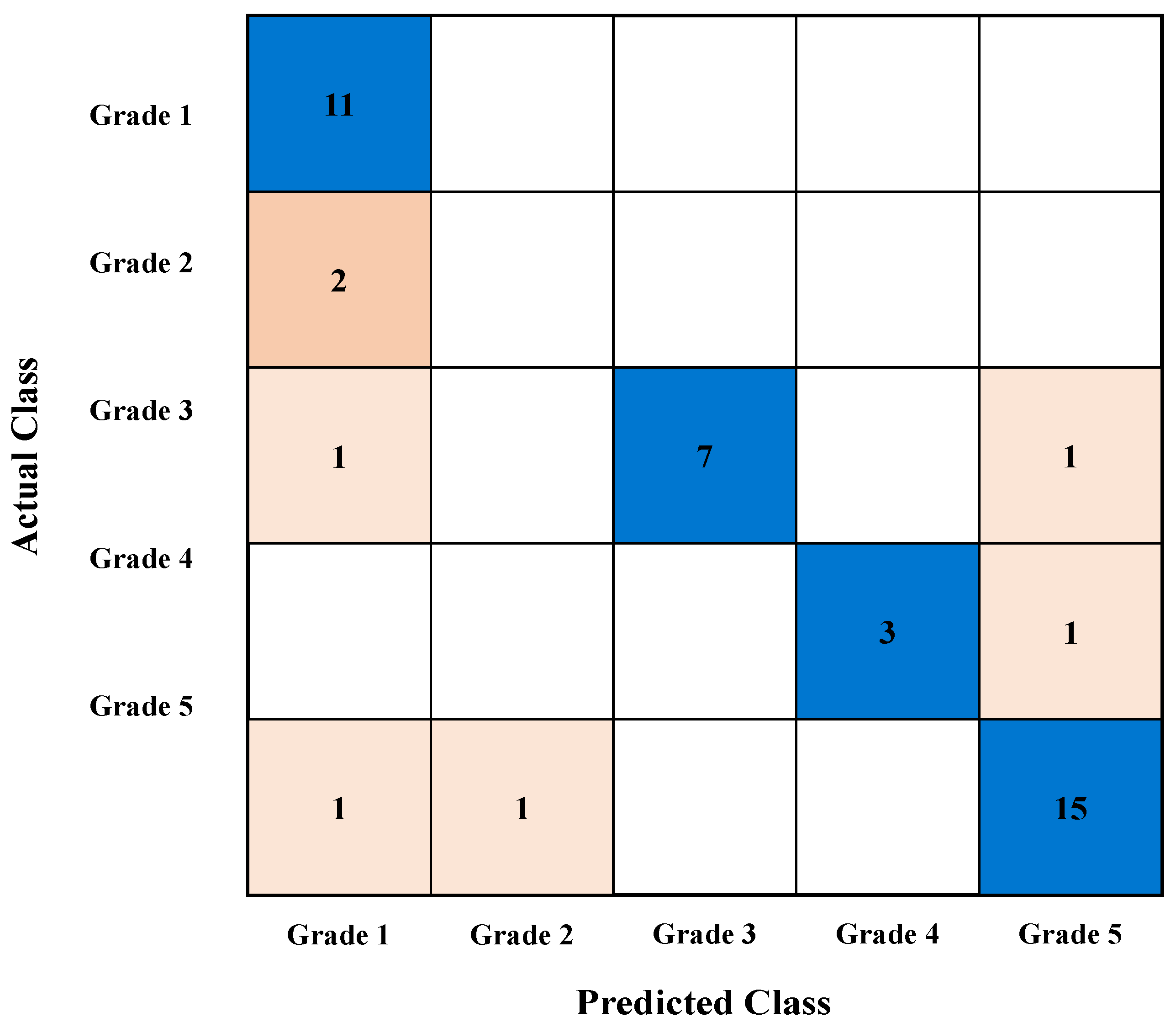

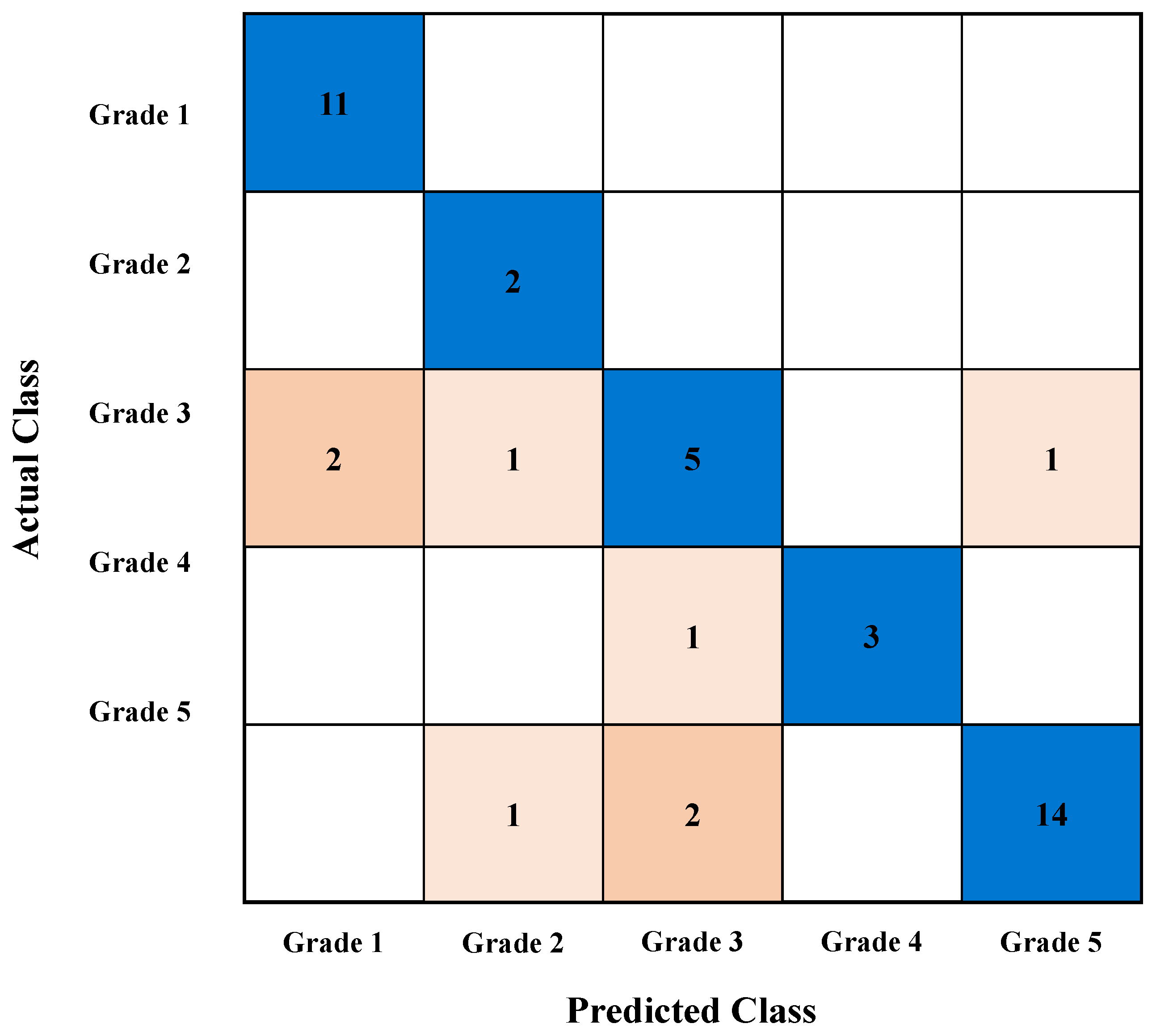

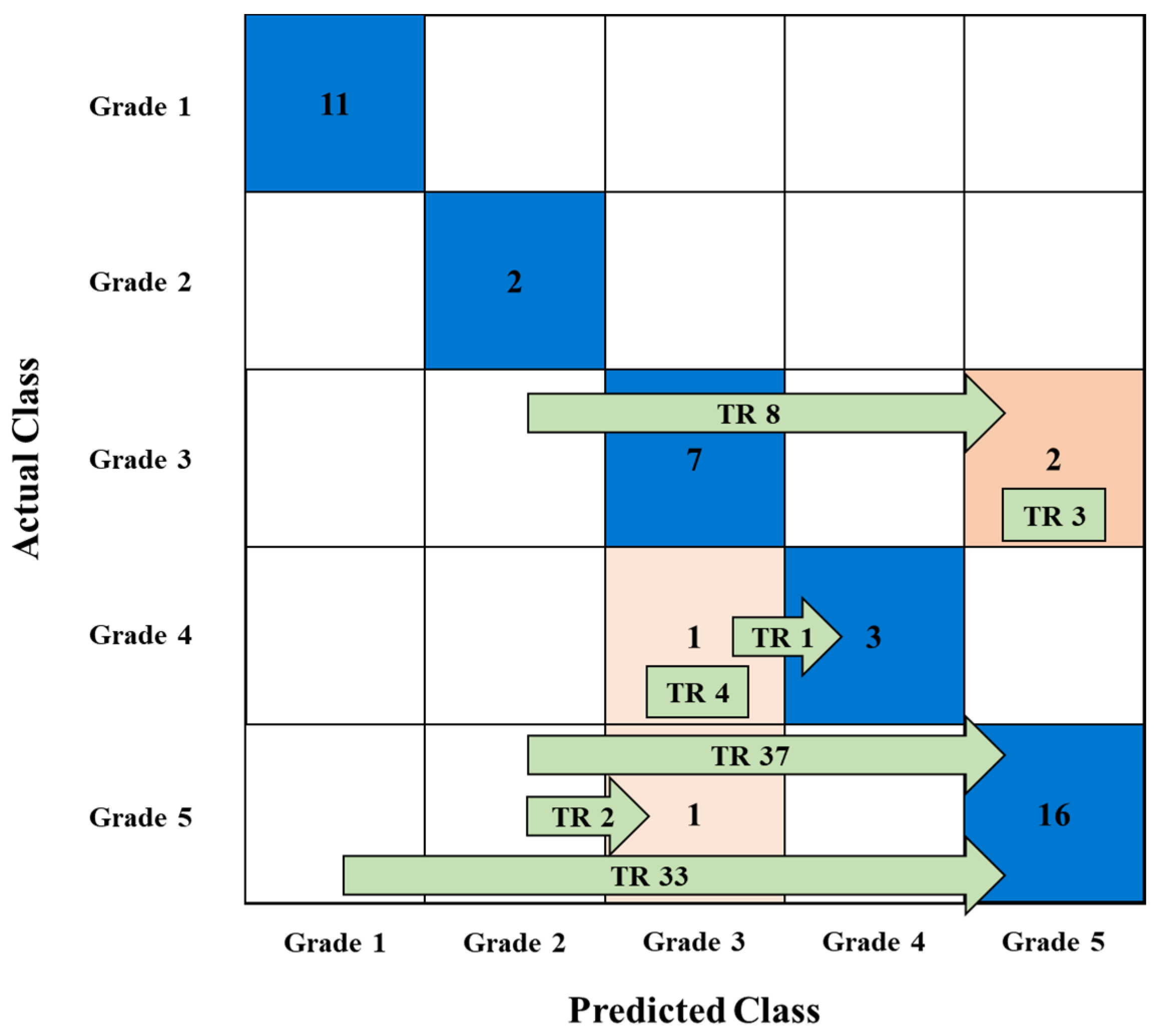

6.3. Representative Case Analysis Using Support Vector Machine (20% Missing Rate)

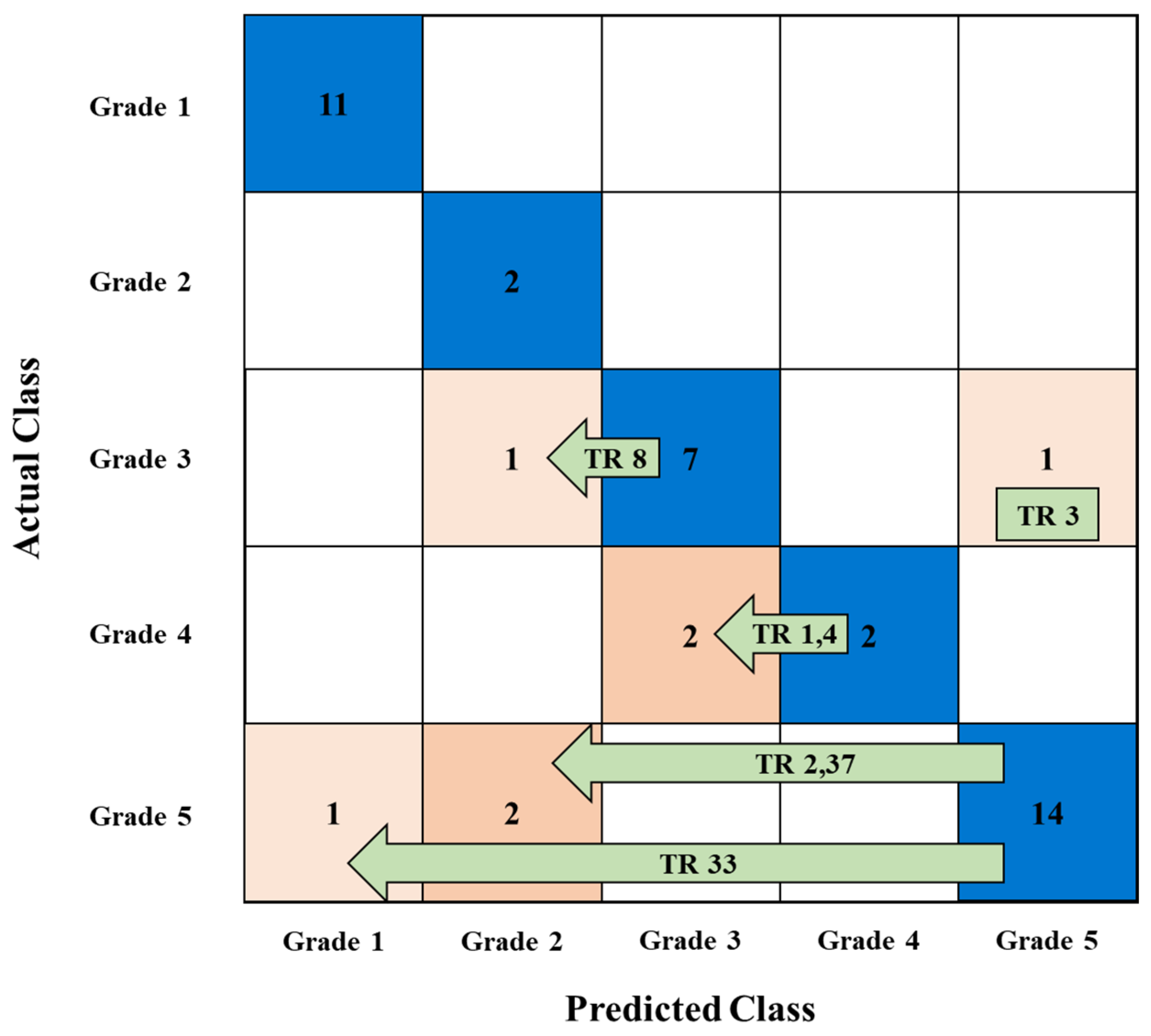

6.4. Verification of the Effectiveness of Missing Value Supplementation Methods Using Actual Failure Case

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE | Autoencoder |

| CIGRE | International Council on Large Electric Systems |

| DGA | Dissolved Gas Analysis |

| DF | Dissipation Factor |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DNV GL | Det Norske Veritas and Germanischer Lloyd |

| EPRI | Electric Power Research Institute |

| FMEA | Failure Mode and Effect Analysis |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| HI | Health Index |

| IEEE | Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| IR | Insulation Resistance |

| kNN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| LOOCV | Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation |

| LpOCV | Leave-p-Out Cross-Validation |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAR | Missing at Random |

| MCAR | Missing Completely at Random |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MNAR | Missing Not at Random |

| OLTC | On-Load Tap Changer |

| PD | Partial Discharge |

| PI | Polarization Index |

| SFRA | Sweep Frequency Response Analysis |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TCG | Total Combustible Gas |

| TR | Power Transformer |

| UHF | Ultra-High Frequency |

References

- Ihendinihu, C.A.; Udofia, K.; Umana, T.I. The Impact of Transformer Failure on Electricity Distribution Network: A Case Study of Aba Area Network. Int. Multiling. J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 8, 6132–6141. [Google Scholar]

- Bartley, W.H. Analysis of Transformer Failures, IMIA Working Group Paper WGP33-03. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual Conference of the International Association of Engineering Insurers (IMIA), Stockholm, Sweden, 15–17 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Cui, Y.; Li, H. Review of Transformer Health Index from the Perspective of Survivability and Condition Assessment. Electronics 2023, 12, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Romaimi, K.; Baglee, D.; Dixon, D. Health Index Assessment for Power Transformer Strategic Asset Management in Electrical Utilities. Int. J. Strateg. Eng. Asset Manag. 2024, 4, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, A.N.; Piercy, R.; Cress, S.; Service, J.R.R.; Wang, F. An Approach to Power Transformer Asset Management Using Health Index. IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 2009, 25, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtzæg, G. Health Indexing of Norwegian Power Transformers. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Taha, I.B.M. Power Transformers Health Index Enhancement Based on Convolutional Neural Network after Applying Imbalanced-Data Oversampling. Electronics 2023, 12, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.T.; Imdad, S.K.; Khan, S.; Khalid, S.; Baig, N.A. Power Transformer Health Index and Life Span Assessment: A Comprehensive Review of Conventional and Machine Learning-Based Approaches. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 139, 109474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.M.; Ali, R.; Yaacob, S.B.; Ananda-Rao, K.; Uloom, N.A. Transformer Health Index by Prediction Artificial Neural Networks Diagnostic Techniques. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2312, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudsi, A.; El-Hag, A. Application of Machine Learning in Transformer Health Index Prediction. Energies 2019, 12, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rashidy, N.; Sultan, Y.A.; Ali, Z.H. Predicting Power Transformer Health Index and Life Expectation Based on Digital Twins and Multitask LSTM–GRU Model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IEEE Standard C57.140-2006; IEEE Guide for the Evaluation and Reconditioning of Liquid Immersed Power Transformers. IEEE Power & Energy Society: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI). Equipment Failure Model and Data for Substation Transformer; EPRI Report 1011989; EPRI: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- CIGRE Working Group A2.37. Transformer Reliability Survey; CIGRE Technical Brochure No. 642; CIGRE: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE Standard C57.152-2013; IEEE Guide for Diagnostic Field Testing of Fluid-Filled Power Transformers, Regulators, and Reactors. IEEE Power & Energy Society: New York, NY, USA, 2013.

- CIGRE Working Group A2.18. Guide for Transformer Maintenance; CIGRE Technical Brochure No. 445; CIGRE: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE Standard C57.104-2019; IEEE Guide for the Interpretation of Gases Generated in Mineral Oil-Immersed Transformers. IEEE Power & Energy Society: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). IEC 60599: Mineral Oil-Impregnated Electrical Equipment in Service—Guide to the Interpretation of Dissolved and Free Gas Analysis; IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. (Ed.) Support Vector Machines: Theory and Applications; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes, J.; Garcia-Lamont, F.; Rodríguez-Mazahua, L.; Lopez, A. A comprehensive survey on support vector machine classification: Applications, challenges and trends. Neurocomputing 2020, 408, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M.; Hart, P.E. Nearest Neighbor Pattern Classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A Decision-Theoretic Generalization of On-Line Learning and an Application to Boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1997, 55, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J.A.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning Internal Representations by Error Propagation. In Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition, Volume 1: Foundations; Rumelhart, D.E., McClelland, J.L., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986; pp. 318–362. [Google Scholar]

- Baldi, P.; Hornik, K. Neural Networks and Principal Component Analysis: Learning from Examples without Local Minima. Neural Netw. 1989, 2, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.A. Nonlinear Principal Component Analysis Using Autoassociative Neural Networks. AIChE J. 1991, 37, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Sub- Component | Failure Mode | Defect Cause | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winding | Conductors | Turn-Turn Fault Ground Fault Lead Fault Magnetic Insulation Fault, etc. | Through Fault Overvoltage Design Flaw, etc. | Overheating, Gassing, Short-Circuit Current, Partial Discharge |

| Lead | ||||

| Insulation | Magnetic Insulation Fault, Short Circuit | Material, Deterioration, Static Electrification, etc. | Overheating, Gassing, Short-Circuit Current, PD, DC Discharge | |

| Core | Steel Insulation | Magnetic Insulation Fault, Short Circuit | Eddy Current Loss Stray-Load Loss Leakage Flux, etc. | Overheating, Gassing, Short-Circuit Current, PD |

| Steel | Casing | Explosions, Flashes and Oil Leaks | Bolt Loosening | Overheating Marks |

| Oil | Oil Leaks | Lack of Antioxidant | Gassing | |

| Bushing | Bushing | Magnetic Insulation Fault, Breakdown, Lightning, etc. | Bolt Loosening, Lack of Maintenance, etc. | Discharge, Short-Circuit, Carbonization |

| OLTC | Diverter | Interphase Contact Discharge, Bonding Discharge, etc. | Bolt Loosening, Wear | Crack, Flashover, Overheating, Discharge, etc. |

| Classification | Inspection Method |

|---|---|

| Basic Electrical | Winding Ratio |

| Winding Resistance | |

| Magnetization Current | |

| Capacitance and Dissipation Factor/Power Factor | |

| Leakage Reactance | |

| Core Ground Test | |

| Frequency Response Analysis | |

| Polarization/Depolarization | |

| Advanced Electrical | Frequency-Domain Spectroscopy |

| Recovery Voltage Method | |

| Electrical Detection of PO | |

| Acoustical Detection of PD | |

| Ultra-High Frequency Detection of PD | |

| Dissolved Gas Analysis (DGA) |

| No. | Input Parameter | No. | Input Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coil Displacement | 12 | C2H4 |

| 2 | Winding Insulation | 13 | CH4 |

| 3 | IR | 14 | C2H6 |

| 4 | Oil Breakdown Voltage Test | 15 | Total Combustible Gas (TCG) |

| 5 | SFRA | 16 | Gas Increase Rate |

| 6 | Double Test | 17 | PD Test |

| 7 | Magnetization Current & Short-Circuit Test | 18 | Damage Position (Insulator) |

| 8 | Angular Displacement | 19 | Degradation |

| 9 | Turn-Ratio Test | 20 | Age |

| 10 | H2 | 21 | Water Content |

| 11 | C2H2 | 22 | IR test on a Bushing Current TR(BCR) |

| TR | Actual HI | Mean | Mode | Missing Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | C2H2 |

| 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | CH4 |

| 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | Age |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | C2H4 |

| 8 | 3 | 5 | 4 | TCG |

| 33 | 5 | 1 | 2 | C2H2, C2H4 C2H6 |

| 37 | 5 | 4 | 3 | TCG |

| TR | Real | Missing Data | AE Imputation | Missing Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | TCG |

| 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | C2H2 |

| 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | Age |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | C2H4 |

| 8 | 3 | 2 | 5 | TCG |

| 33 | 5 | 1 | 5 | CH4, C2H4, C2H6 |

| 37 | 5 | 2 | 5 | TCG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, S.-Y.; Oh, J.-S.; Park, J.-D.; Lee, D.-H.; Park, T.-S. Autoencoder-Based Missing Data Imputation for Enhanced Power Transformer Health Index Assessment. Energies 2026, 19, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010244

Lee S-Y, Oh J-S, Park J-D, Lee D-H, Park T-S. Autoencoder-Based Missing Data Imputation for Enhanced Power Transformer Health Index Assessment. Energies. 2026; 19(1):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010244

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seung-Yun, Jeong-Sik Oh, Jae-Deok Park, Dong-Ho Lee, and Tae-Sik Park. 2026. "Autoencoder-Based Missing Data Imputation for Enhanced Power Transformer Health Index Assessment" Energies 19, no. 1: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010244

APA StyleLee, S.-Y., Oh, J.-S., Park, J.-D., Lee, D.-H., & Park, T.-S. (2026). Autoencoder-Based Missing Data Imputation for Enhanced Power Transformer Health Index Assessment. Energies, 19(1), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010244