1. Introduction

In a regional context, competitiveness is conceptualized differently than in the case of enterprises. Primarily, it is because regions do not function as enterprises, so they compete in an entirely distinct manner. Building the competitive advantage of regions relative to other entities is based on creating an inviting environment for investment, living and future development. This effort should be the primary base for long-term development strategies implementation.

Innovation is consistently regarded as the driving force of the economy and is therefore considered one of the most significant factors contributing to competitiveness in the long run. The development of innovations appears to be closely linked to the advancement of AI models, which generate high energy demand. Therefore, the importance of an access to energy sources is growing. Regions, especially industrialized ones, base their competitiveness not merely on innovation or institutions, but also on social cohesion and the realization of ecological ambitions [

1]. This perspective has begun to function under the term of sustainable competitiveness. With regard to this competitiveness perspective, social investments and ecological ambitions are not treated as costs, but as factors supporting and enhancing the potential of regional competitiveness. The factors related to the utilization of regional resources and clean-tech solutions have therefore become a matter of increasing importance.

In the described context, the perspective of energy production, storage and consumption seems a crucial domain to focus on with regard to sustainable competitiveness of economies and regions. This perspective is also regarded as one critical for shaping future competitive potential [

2]. The main objective of this article is therefore to evaluate the sustainable competitiveness potential of Polish regions from the perspective of energy-related factors, as well as to identify the trends and disparities observed over the past decade. We formulated three basic research questions.

RQ1: Is there measurable growth in sustainable competitiveness potential driven by energy factors, and is this growth characterized by regularity over time?

RQ2: How do energy factors contribute to regional differences in sustainable competitiveness potential?

RQ3: How does sustainable competitiveness potential vary over time in relation to the processes of energy transformation?

There are two main reasons why Poland, as one of European Union (EU) member states, seems to represent a relevant case for addressing this research objective. The first reason pertains to the sustained long-term productivity growth of the Polish economy, which has been evident since the beginning of its economic transformation and has further accelerated following its accession to the EU, exhibiting an average annual GDP growth rate of 3.6% since 2000. The second reason concerns the significant delays in Poland’s energy transformation, reflected in its previously lowest EU ranking in renewable energy use (the share of electricity produced from renewable sources was less than 2% in 2000), so the energy system remained heavily dependent on fossil fuels—factors that raise concerns regarding the long-term sustainability of economic growth.

With regard to energy aspects, the study is potentially broad and constrained only by the scope of a long-term, comparable database. It involves many areas related to resource, economic, environmental and social perspectives, such as the way the energy is produced or obtained, the use of renewable sources, the energy balance, the share of energy consumption in the regional industrial value added, or the level of energy poverty. The study covered all Polish regions in the 10-year period of 2014–2023. STRATEG (

www.stat.gov.pl), which is a publicly accessible database of the Central Statistical Office in Poland, was used to perform the analysis.

Applied methodology involved diagnostic variables adjusted to reflect the described energy issues with regard to sustainable competitiveness, as well as its main barriers. Ultimately, the adopted methods involved using a synthetic measure to capture and interpret the trends observed over the recent decade. As a result of the multidimensional comparative analysis (MCA) performed using an integrated indicator—synthetic measure of potential (SMP)—the regions were ranked according to their level of sustainable competitiveness potential. This approach was additionally complemented by a cluster analysis using Ward’s method to detect structural regularities and classify observations into meaningful groups. The analysis was performed with the use of STATISTICA analytics software Version 13.3.

The outline of this paper is as follows.

Section 2 provides theoretical background by reviewing the literature related to the concept of sustainable competitiveness with special focus on energy perspective. This section also defines the existing research gap.

Section 3 presents the adopted methodological assumptions of the analyses, whereas

Section 4 presents the results of the conducted research. The following section discusses the study’s findings, while the final section presents the main conclusions, outlines the limitations, and identifies fields for future research. It also highlights the key practical implications derived from the results.

2. Literature Reviews

The concept of sustainable competitiveness signifies the ability to create and maintain the well-being and standard of living of the present society without compromising the level of well-being of future generations, so it emphasizes the need to integrate increased productivity with social and environmental factors [

3]. The majority of academic scholars refer to sustainable competitiveness of regions as maintaining the standard of living and the quality of life of the community within a given area [

4,

5]. Hence, the sustainable development of regions is closely related to their socio-economic growth and competitiveness [

6]. In this context, sustainable competitiveness involves improving the productivity of production factors and the resources of an area (country, region) over the long term, while ensuring social development and environmental balance [

7].

High competitiveness also allows regions to adapt more quickly to climate change, which increasingly affects the quality of life [

8]. The synergy of innovation, social cohesion and ecological ambitions is necessary to implement coherent and well-coordinated actions, that stimulate regional and consequently national economic growth without adversely affecting society and nature [

9]. The basis for sustainable competitiveness is therefore related to the aspects of ecological and environmental resources economy, mainly in the areas of clean technologies, pollution, waste management, recycling or reuse [

10,

11].

The sources of competitive advantage depend on the stage of development and are founded on resources, investments and innovations. At the initial stages of building competitive position, the proper utilization of possessed (available) natural resources is paramount. Along with the progress achieved, the investment and technology transfer may further determine the competitive edge, which should ultimately be based on innovations [

12,

13]. Although globalization processes enhance and create sustainable competitive advantage based on innovative activities [

14], the disparities in individual regions’ advancement levels still maintain significant obstacles to sustainable development [

15]. The differences among countries and regions are likely to lessen through the diffusion of knowledge and technologies [

16].

Nevertheless, regional development is still influenced by individual characteristics and an array of factors such as resources, the natural environment, financial capital, the level of science and technology, as well as investment areas [

17]. These factors can vary in importance, overlap, complement each other, and form a more significant whole. Moreover, the presence of numerous complementary factors will not necessarily compensate for the lack of key elements essential for a particular region’s development [

18]. For these reasons, the development potential at the national level may differ from that at regional or local levels and may still vary significantly [

19].

Importantly, as changes occur, the factors influencing those changes may also evolve [

20]. Resources such as natural, human, capital, knowledge, and technology, along with capital in the form of human, social, financial, and material assets, with a suitable socio-cultural, economic, administrative, and political climate, contribute to the region’s attractiveness. This attractiveness, in turn, determines the potential for competitive edge and ultimately leads to its growth in the long term. In this context, economic development should encompass durability, attention to social cohesion, and the condition of the natural environment, i.e., factors that are vital for sustainable development [

21].

Energy access, with primary focus on renewable sources of energy (RES), is especially important for developing emerging economies’ sustainable economic growth in order to draw in foreign investment [

22]. Moreover, the use of RES, such as biomass, solar photovoltaic systems, wind turbines, or concentrated solar power plants, could greatly support the development of a low-carbon sustainable economy [

23,

24]. This is especially important in the current reality of disruptive changes related to the implementation of new technologies supported by AI models’ development, which is driving a rapid increase in energy demand [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Although innovations require large amounts of energy, their implementation enables the development of cleaner and more efficient technologies, so the potential to create innovations and gain competitive edge is therefore directly linked to the ability to obtain energy. A growing body of economic research is examining how induced technological change can drive innovation in the renewable energy sector [

29]. The main issues are associated with factors such as technological spillovers [

30,

31] or environment pollution as a negative externality [

32], so all factors adversely influencing regional sustainability.

Each territory possesses unique characteristics that create competitive potential, including not only the space and resources but also so-called soft factors, such as management methods. With regard to energy, focusing management efforts on promoting clean technologies is essential for advancing the transition toward a carbon-neutral economy. Consequently, the concept of green growth is gaining increasing attention among both scholars and policymakers [

33]. It is thought to shift the perspective from seeing environmental regulations as costly burdens on the economy, to viewing them as valuable opportunities—linking environmental protection, especially in the context of climate change, with job creation, technological advancement, and enhanced competitiveness of domestic industries [

34]. This transition, however, may be seriously delayed, as market mechanisms alone cannot provide the socially optimal amount of clean innovation [

35]. The economy has so far accumulated relatively limited knowledge regarding clean technologies; therefore, green innovations—though vital for sustainable development—are also marked by uncertainty concerning their future returns [

36]. In this context, the importance of energy issues seems growing and critical to shaping the regional sustainable competitiveness in general. It also appears to be far more complex and multidimensional than merely focusing on the use of RES.

Since disaggregated data enhances the understanding of the complex interactions between behavioral and technical components of energy use, many academic scholars have employed disaggregated methods (indicators). Following the release of the Brundtland Report and further the Earth Summit in 1992, the importance of indicators supporting the decisions concerning sustainable development with regard to energy issues was recognized [

37]. Energy indicators were first developed to analyze household energy use, carbon dioxide emissions or energy efficiency in the industry and transport sectors. Energy indicators related to sustainable development could generally be classified in resource, economic, environmental, technical or social dimensions. Various sustainability-related indicators have been developed to address the detailed dimensions of energy sustainability [

38,

39,

40,

41].

Energy indicators were further widely used by the United Nations within Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7), OECD, the EU, organizations such as the International and the European Energy Agency (IEA, EEA) and recently the World Economic Forum (WEF) within the energy transformation framework. Globally used indicators of SDG7 assess the progress towards achieving affordable and clean energy, incorporating metrics related to the universal access to electricity and clean fuels, the proportion of RES within the global energy mix, and enhancements in energy efficiency [

42]. Key indicators are as follows: the proportion of the population with access to electricity; renewable energy share in the total final energy consumption; energy intensity measured in terms of primary energy and GDP; international financial flows to developing countries in support of clean energy research and development and renewable energy production, including in hybrid systems; installed renewable energy-generating capacity in developing and developed countries.

Concerning energy transition readiness, the WEF indicators incorporated within the Energy Transition Index (ETI) framework encompass perspectives on [

2] the following: security (diversification of supplies, grid and power supply reliability, and robust infrastructure); equity (access to energy for all consumers and industries, energy affordability and price stability); sustainability (environmental performance of energy systems to support a low-emissions, resource-efficient, clean energy; lowering per capita energy and emissions footprints; further increasing the share of clean energy in the energy balance).

Utilizing the complete set of indicators offers a comprehensive overview of the energy and sustainable development and therefore can be employed to assess progress towards achieving sustainable competitiveness potential over time. While the disaggregated approach is commonly used for analyzing intercountry energy patterns by the OECD or the EU, the regional perspective concerning transforming economies appears to remain underexplored. The recent regional trends within this domain therefore seem interesting to identify, as they may be decisive for future sustainable development. This is particularly important for the Polish economy, which serves as a strong example of rapid economic growth over the past decade, accompanied by an ongoing transformation of its energy resources, driven by both global disruptions and still continued reliance on a coal-based energy sector.

3. Materials and Methods

In order to evaluate the potential of regional sustainable competitiveness from a complex perspective of energy factors, a multidimensional comparative analysis (MCA) was carried out. The general purpose of MCA is to arrange the analyzed objects from the “best” to the “worst” and thus, with regard to this study, objectives from the “highest” to the “lowest”. For this reason, the foundation of MCA lies in the necessity to clarify the nature of the diagnostic variables selected at the outset [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Consequently, it is important to identify stimulants (variables for which higher values are favorable based on the established general criterion), destimulants (variables where lower values are advantageous for the general criterion), and, if applicable, nominals (variables that possess an optimal level, with both upward and downward deviations viewed negatively). One should have in mind that, in cases where a variable is considered a nominator but determining a nominal level proves challenging, it is categorized as a stimulant.

Various formal and statistical methods can be used, but most often the nature of the variables is determined by the terms of content, which is the definition and meaning of the considered feature, and it usually determines its impact on the general criterion. This approach has a decisive role [

49]. Regardless of the taxonomic methods used subsequently, the final list of diagnostic variables is of decisive importance for the results of the study, and therefore it should be considered the best representative of the given issue. The list is usually created on the basis of a consensus between ambitions in terms of the best substantive description and the limited availability of reliable, complete, and comparable statistical data. This consensus was also reflected in the development of the MCA for the purposes of this study.

Furthermore, diagnostic features should not duplicate information provided by others, and thorough recognition of the described phenomenon, as well as knowledge of previous achievements, own thoughts, experience, expert opinions and common sense, are of paramount importance. Ultimately, the selection of diagnostic variables remains an important methodological challenge [

50]. There is no clear answer to the question whether to be guided by the criterion of variability or correlation when choosing variables, or whether to introduce differentiated weights expressing the relative importance of variables. Each case requires separate assessment and individual, reasonable and well-thought-out decisions [

51]. In practice, most researchers give equal importance to each feature and apply equal weights, and substantive selection seems to have advantage over formal selection.

The described approach was reflected in the development of the MCA used for the purposes of this study. Individual features are carriers of various information about the described issue; thus, their joint assessment did not implicate objections. Equal importance of each variable and equal weights were used. We ultimately defined ten key factors of sustainable competitiveness potential, related to energy issues such as: energy balance reflected by the ratio of electricity production to electricity consumption; share of electricity production from RES in total electricity production; share of energy from RES in gross final energy consumption; heat energy produced in co-generation; total electricity consumption; electricity consumption per unit of GDP, as well as the consumption in the industrial sector per gross value added; share of hard coal and lignite in electricity generation; primary energy consumption; and finally, energy poverty level. Energy poverty level was assessed using the low-income high-cost (LIHC) methodology. In this framework, low income is identified as disposable income falling below the officially established poverty line, while high energy costs are defined as those exceeding the national median. Thus, the final set of applied indicators encompassed resource, economic, environmental, and social dimensions of energy use. All adopted variables—4 stimulants and 6 destimulants with detailed enumeration are presented in

Table A1 in the study

Appendix A.

The proposed set of characteristics was expressed in relative rather than absolute units. This approach allowed them to become independent of the area and population of particular region; thus, the quantities created in this way indicated the structure or intensity of a given phenomenon. Further, the synthetic measure of sustainable competitiveness potential (SMP) was used, multiplied by one hundred arithmetic mean of diagnostic variables, and reduced to comparability through zeroed unitarization, which was mathematically expressed by the formula:

where

—relative potential factor,

—the number of variables taken into account in the study,

—normalized value of the j-th feature in the i-th region, where the algorithm for stimulants is as follows:

—the actual value of the j-th feature in the i-th region in a given year,

min{}—the smallest value of the j-th feature in a given year,

max{}—the highest value of the j-th feature in a given year,

—the range of the j-th feature in a given year, i.e., the difference between the largest and the smallest value of the j-th feature in a given year.

The values of the aggregate SMP determined using Formula (1) may oscillate between zero and one hundred, with a higher value indicating a better place in the ranking. The next step towards the use of specific linear ordering procedures within the MCA was the normalization of variables. Some of the well-known normalization formulas include zeroed unitarization, which makes it possible to bring dissimilar variables to mutual comparability (additivity postulate), and additionally eliminates negative values from the calculations (positivity postulate). After its application, the values of each variable were contained in a mutually closed range from zero to one.

One should have in mind that the methodology of the SMP adopted in this study is widely used in practice and therefore consistent with generally accepted measures such as the UN Human Development Index (HDI) or the Summary Innovation Index (SII) commonly used in the EU nomenclature. It is also worth adding that the proposed formula is a consequence of the evolution of views in this regard under the influence of many critical remarks over time. Although disaggregated indicators often exemplify a compromise between substantive principles and available information, they form the basis for calculating various widely accepted synthetic measures supported by energy efficiency data [

52,

53]. These measures are further computed as an unweighted average of the results from all indicators, normalized using the zero-unitarization method as employed in this study.

In addition to linear ordering, cluster analysis is a methodological procedure frequently employed in MCA-based regional research. It represents an analytical procedure that facilitates the organization of statistical material by partitioning the examined set of objects into groups or clusters that are internally homogeneous with respect to the characteristics used to describe the multidimensional phenomenon under investigation. The initial set of observations is heterogeneous and therefore requires partitioning in such a way that observations assigned to the same group exhibit a high degree of similarity, while those allocated to different clusters are clearly dissimilar. The similarity between objects increases as the differences in the values of the adopted diagnostic variables diminish. Cluster analysis is therefore a multidimensional statistical method which aims at sorting objects into groups in a way that the degree of association between two objects is maximal if they are part of the same group and minimal otherwise [

54].

A wide range of measures may be employed to evaluate the similarity between objects, however distance-based measures are particularly prominent, including the Minkowski metric, as well as the Canberra, Bray–Curtis, Clark, and Jeffreys–Matusita index. Drawing on the theoretical properties of hierarchical agglomeration methods, as well as the findings of simulation studies, it has been demonstrated that the Ward method performs the best, exhibiting greater effectiveness in detecting the true data structure compared to the next most effective approach [

55,

56]. In view of its demonstrated precision in allocating objects to clusters, the Ward method was further applied in the cluster analysis conducted in this study.

At each stage, the method originally sought to minimize the sum of squared distances between emerging groups while cluster identification and interpretation were conducted via a linkage procedure, typically represented graphically as a dendrogram. Other distance measures are also available for selection. These comprise the squared Euclidean distance, Euclidean distance, Manhattan distance, Chebyshev distance, power distance, percent disagreement or Pearson’s 1−r coefficient. The selection of an appropriate distance measure is not unambiguous, and the principal challenge lies in determining the stage at which the agglomeration process should be terminated, so that the resulting partition may be regarded as the final clustering solution for multivariate objects. In applied research, Euclidean distance is frequently employed as a preferred alternative [

57]. Accordingly, this measure was adopted in the empirical analyses, the results of which are presented in the subsequent section of this study.

In Ward’s method, clusters are formed by minimizing the increase in linkage distance at each agglomeration step, ensuring that the resulting groups are as homogeneous as possible. Since no definitive criterion exists for determining the number of groups in the analyzed dataset, no universally applicable indicator can be employed, and the selection of the number of clusters remains largely a subjective decision. To facilitate the analysis, particularly in relation to RQ2 and RQ3, a consistent linkage distance was applied to the results for both 2014 and 2023.

Ultimately, STRATEG which is publicly accessible database of the Central Statistical Office in Poland was used to perform the analysis. All data used to calculate disaggregated variables is available on

www.strateg.stat.gov.pl. The most up-to-date accessible database was used—as of 1 October 2025. The MCA, operationalized through the construction of a Synthetic Measure of Potential (SMP) incorporating all ten presented disaggregated indicators, and supported by cluster analysis based on Ward’s method, was performed using STATISTICA analytical software. Additionally, a classical coefficient was applied to assess the differentiation of both the synthetic and disaggregated measures.

4. Results

All diagnostic variables were calculated for the period of 2014–2023 (recent decade) for each Polish voivodeship, which in this case corresponds to the EU NUTS2 regional classification. As the average values of diagnostic variables adopted as stimulants were concerned, 3 out of 4 indicated an increase in relative values. Only one factor, which was co-generation energy production, remained at similar level. As destimulants were concerned, only 2 out of 6 adopted variables decreased both in nominal and relative values. These were: electricity consumption in the industrial sector per PLN 1 million of gross value added and the share of hard coal and lignite in electricity generation. It should be noted, however, that the relative magnitude of destimulants’ increases was considerably lower than that observed for the stimulants; hence, one considerable exception was identified. This was the energy poverty level based on low-income high-cost approach (LIHC), which increased significantly during the recent decade in the majority of Polish regions (13 out of 16).

As the diagnostic variables were presented both in relative and nominal values, the increase or decrease were presented in relative values. The relative increment of an average value of adopted stimulants in 2023 comparing to 2014 was observed as follows: the share of electricity production from renewable sources in total electricity production by 62.1%; the share of energy from renewable sources in gross final energy consumption by 42.6%, and finally, the ratio of electricity production to electricity consumption by 5.6% The only measure with an observed slight decrease by 0.3% was co-generation energy production.

The adopted destimulant values provided ambiguous results. The relative decrease in an average value in 2023 comparing to 2014 was observed for electricity consumption in the industrial sector per PLN 1 million of gross value added by 42.3% and the share of hard coal and lignite in electricity generation by 24.7% On the contrary, the remaining destimulants provided the following relative increases in the average value: the energy poverty level by 13.8%; primary energy consumption by 4.2% and electricity consumption per PLN 1 million of GDP by 2.6%.

Further, the aggregate SMP was calculated for each region during 2023–2014 and subsequently, ranking positions were established. The detailed results of SMP values are presented in

Table 1.

The average value of SMP for all regions increased by 4.1 from 48.9 in 2014 to 53 in 2023. Regional disparities increased slightly over the study period; however, greater variability was observed in the values of individual indicators. The detailed results of adopted variables are presented in

Table A2 in the study

Appendix A. The development of ranking positions of individual regions is presented in

Table 2.

Three regions (Lubelskie, Warmińsko-Mazurskie, Wielkopolskie and Zachodniopomorskie) have significantly improved their results, whereas one region (Kujawsko-Pomorskie) has deteriorated. The leading regions have generally improved their positions over recent decade. On the contrary, regions with the worst results (regions historically dependent on fossil-fuel-based energy) such as, Opolskie, Śląskie and Dolnośląskie, similarly failed to demonstrate an improvement throughout the research period. As individual results are concerned, the relative increment in 2023 compared to 2014 for the share of electricity production from RES revealed as the most coherent factor of sustainable competitiveness potential. Conversely, energy poverty level provided the most concerning results—only four regions managed to improve their scores during the recent decade, so it appears to be the most problematic issue in terms of the quality of life in the long run. Although there was no visible tendency concerning individual SMP average values during 2014–2023, the improvement towards 2014 was observed mainly deriving from the increasing role of RES and decreasing consumption in the industrial sector towards generated gross value added.

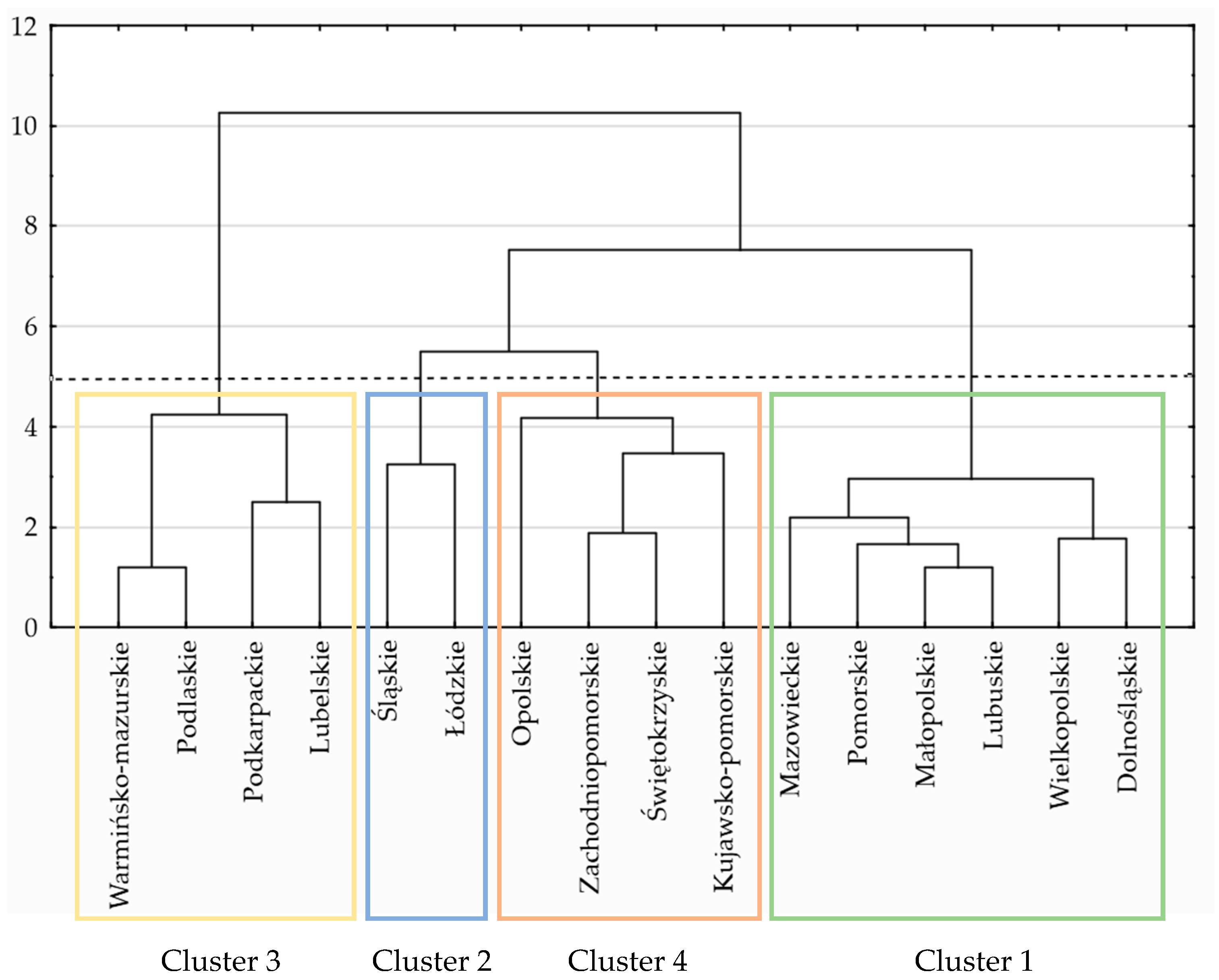

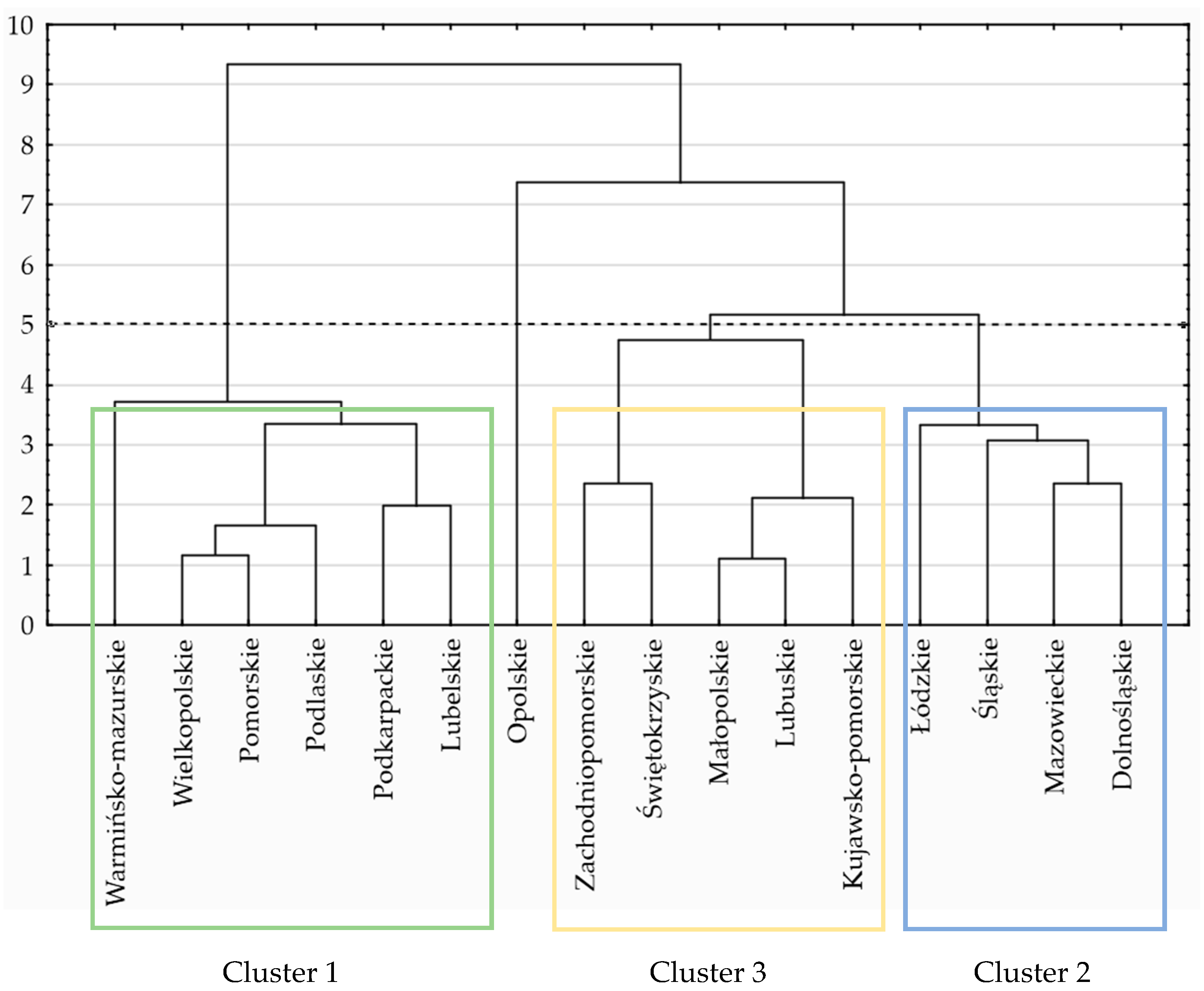

Data on Polish regions for 2014–2023, as previously described, were further used to classify the voivodeship. Following the outlined methodology, variables were normalized via classical standardization, and clustering was conducted using Ward’s method with Euclidean distance. To illustrate regional disparities and assess changes within the context of the energy transition,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 display the cluster dendrograms and corresponding cluster compositions, derived from the ten disaggregated indicators, with the use of a consistent linkage distance for 2014 and 2023, respectively.

Four clusters were identified in 2014, with cluster 1 occupying the leading position, characterized by an average SMP value of 55.4. In contrast, cluster 4 exhibited an average SMP value of 38.7, while clusters 2 and 3 had values approximately ranging from 48 to 49.5. Clusters 1 and 2 comprise regions with well-developed energy infrastructure, predominantly dedicated to hard-coal- and lignite-based energy production. As a result of transition processes, the leading regions enhanced their positions, shifting predominantly from cluster 3 in 2014 to cluster 1 in 2023 (Warmińsko-Mazurskie, Podlaskie, Podkarpackie, Lubelskie). Moreover, only two regions with sufficiently developed infrastructure maintained their positions in 2023. In contrast, several regions that initially exhibited favorable conditions (Mazowieckie, Łódzkie, Dolnośląskie, and Śląskie) demonstrated reduced engagement in energy transition processes and consequently shifted to cluster 2 or 3. As a result, the average SMP value in 2023 amounted to 60.4 for cluster 1, compared with 52 for cluster 3. Although the remaining regions generally improved their SMP values, these gains were insufficient to enable advancement to a higher cluster. An interesting pattern emerged in case of Opolskie, a region largely absent from energy transition processes over the past decade, and therefore not assignable to any cluster in 2023. Notably, it was the only region exhibiting both the lowest RES share (6.2%) and the highest increase in energy consumption (17.3%)—developments that ultimately contributed to the largest rise in energy poverty, from 12.6% in 2014 to 21.8% in 2023.

5. Discussion

The empirical results of this study demonstrate that the potential for regional sustainable competitiveness in terms of energy factors has generally increased in Poland over the past decade. The results obtained align with existing research on regional economic development within the EU, emphasizing the central role of renewable energy factors [

58]. We can therefore partially affirm the first research question (RQ1). The measurable increase in sustainable competitiveness potential, as indicated by the applied energy indicators associated with resource, economic, environmental, and social perspectives, has been confirmed; however, a consistent trend over time was not observed. Furthermore, a noticeable increase in SMP values was evident only during the final years of the examination, specifically in 2022–2023.

The majority of Polish regions revealed an increase in SMP values improving their potential for sustainable competitiveness in the long run (12 out of 16). They ultimately revealed an increase in diagnostic stimulants both in nominal and relative values. The perspective of destimulants provided more ambiguous results; however, the impact of adverse increases was considerably lower, with one notable exception—the rising level of energy poverty. In the EU energy transformation process, the impacts of the shift to RES on energy poverty have become an increasingly important topic of discussion. According to the studies mainly concerning developed EU member states, an increase in the share of RES provides an average decrease in energy poverty [

59]. Conversely, other studies clearly highlight disparities between the developed EU member states and those that joined in 2004 or later. In the “old” EU member states, a moderately positive relationship was identified between RES use and reductions in energy poverty, whereas in the “new” member states, this relationship was very weak or absent [

60].

Regarding regional differences (RQ2), the variation in SMP values measured by the classical coefficient remained consistent, ranging between 22% and 25% throughout the entire research period. The most significant variations were noted for the share of electricity generated from RES within total electricity production. The classical coefficient across all regions decreased from 95.8% in 2014 to 69.5% in 2023. Similarly, the differentiation of electricity production to electricity consumption ratio also experienced a slight decline, from 75.2% to 66.8%. In contrast, the average differences in energy poverty levels increased from 23.9% to 31%. While the overall variation in the SMP concerning all energy factors is relatively low, there are noteworthy regional disparities specifically within certain indicators related primarily to RES or energy balance, despite a slight decrease in differentiation being observed. It is also worth noticing that the transition towards clean energy appears to be linked with greater regional disparities in energy poverty. This is particularly evident in regions that have discontinued or failed to pursue energy transformation efforts.

The results obtained can be viewed from a broader perspective that includes individual EU member states. While the average values of RES indicators for all Polish regions fall below the EU average, several leading regions stand out and can be compared to transition leaders such as Sweden, Portugal, Denmark or Austria (primarily relying on renewable hydro energy). In 2023, the share of electricity generated from RES in Europe’s leading countries ranged from 79.4% to 87.5% [

61], whereas Polish regions assigned to cluster 1 recorded an average share of 66.8%. Within this group, the three highest-performing regions exhibited values between 74.6% and 97.6%. It is important to note that the generation of electricity was primarily driven by the rapid development of large wind and solar farms. In this regard, the utilization of renewable energy potential is closely contingent upon territorial characteristics—such as spatial location and geographic features of the respective units—which is consistent with findings reported in other studies [

62].

Conversely, the regions historically associated with coal or lignite production exhibited RES shares ranging from 6.2% to 10.2% (all regions assigned to cluster 3 recorded an average share of 11.3% in 2023), comparable to the lowest among EU member states such as Luxembourg, Malta, and Czechia. These regions generally exhibited lower levels of energy poverty and a diminished emphasis on energy transition, which contrasts with some existing studies on sustainability related to progress and green technology innovation [

63]. It seems that, although renewable energy promotes long-term growth, the short-term implementation costs may complicate the competitiveness analysis [

64]. Countries or regions with a stronger reliance on fossil fuels often exhibit competitive advantages derived from their established infrastructures [

65], a pattern also observed among cluster 1 regions in 2014 in Poland. Given these circumstances, mobilizing communities to engage in energy transition initiatives and adopt sustainable energy practices remains a challenge, as supported by findings from other studies [

66,

67].

As previously mentioned, we can also affirm that the sustainable competitiveness potential increases over time in relation to energy transformation processes (RQ3), although the most favorable trends were noted for disaggregated indicators, rather than synthetic ones. This generally corresponds with the findings of other studies which reveal significant disparities in the pace and scope of energy transition across member states. Poland, as well as other Central and Eastern European countries, record significantly lower performance of synthetic measures concerning energy transformation in relation to developed EU economies [

68]. It is argued that these differences reflect the varying starting points, policy approaches, and implementation speeds in pursuing energy transition objectives. It is noteworthy, however, that the majority of regions assigned to cluster 1 in 2023 constitute an exception in this regard.

Obtained results appear to contradict studies examining barriers to RES implementation and consumption, which identify administrative and political constraints as the most significant obstacle for the majority of Central and Eastern European member states, including Poland [

69]. Alternatively, this may reflect crucial support from local authorities, particularly concerning approvals or permitting processes, to facilitate regional energy transition initiatives, despite the broader investment reluctance observed at the national level. This factor may be particularly critical, as overly complex regulatory frameworks and low levels of societal awareness are regarded as key bottlenecks to the diffusion of renewable energy technologies in general [

70].

Our study findings additionally highlight the significant regional disparities that generate uneven effects of transformation on national level. The formerly less advantaged regions strengthened their relative standing despite initial deficiencies in energy infrastructure. In contrast, several regions that initially possessed comparatively favorable conditions subsequently exhibited a reduced level of engagement in energy transition processes. Regarding infrastructure-related barriers, insufficient grid capacity to distribute RES-generated energy is attributed to the high costs of connection or limited transparency of connection procedures.

In this context, our findings suggest that regions with initially more favorable conditions for grid connections are not fully leveraging their infrastructural potential. This is particularly evident given that Poland and Portugal exhibit the lowest barrier index for grid regulation and infrastructure across the entire EU [

71]. Furthermore, regions that discontinued transformative activities—particularly those aimed at increasing the share of RES or implementing technologies that reduce energy consumption—have visibly lost their initial competitive potential. These observations align with prior research indicating that the transformation must confront persistent disparities in energy dependence and the uptake of RES, thereby reinforcing the need for more tailored policy approaches targeting specific regions or regional clusters [

72,

73].

Regarding the disaggregated indicators, the most notable progress was observed in the increasing generation of energy from RES, primarily from off-shore wind and photovoltaic farms, which resulted in both increasing share of green energy in the system and decreasing role of hard coal and lignite. Further, significant improvement was also observed for decreasing electricity consumption in the industrial sector per unit of gross value added, and at the same time electricity production to consumption ratio. This suggests that the shift toward RES does not necessarily have a negative impact on industrial efficiency in the long run, as well as confirms that the rise in energy consumption was met by energy generated from RES, while more efficient and less energy-intensive clean technologies were simultaneously implemented in the industrial sector. This also demonstrates proper energy management as an important instrument to decouple industrial growth from fossil energy consumption, particularly for energy-intensive industries [

74].

As we ultimately classified overall energy consumption as a destimulant, patterns similar to those observed in the industrial sector were also identified for households. Regions at the forefront of the shift to RES showed a concurrent reduction in total energy consumption, while those with stronger reliance on fossil fuels displayed a persistent upward trend in energy use. It therefore appears that transformation processes related to energy sources also generate additional effects in terms of more efficient energy use, driven by energy-saving technologies and the growing prevalence of self-consumption, largely resulting from the increasing adoption of solar panels. However, we acknowledge that the opposite approach—considering consumption as a stimulant or nominate—could also be justified in cases where older technologies are replaced by electrically powered ones due to different development stages of each region.

The results align with the experiences of green transitions primarily driven by RES, as observed in an increasing number of countries and regions, including the European Union, China or South Korea [

75]. There is ongoing debate regarding the effectiveness of RES support schemes and the extent to which the additional benefits promised by green growth advocates—particularly in terms of employment, technological advancement, and domestic industry competitiveness—have been realized [

76,

77]. Recently, the substantial investments in renewable energy capacity have been driven at least as much by the competitive “green race” as by concerns for climate change mitigation and sustainability [

33]. Conversely, with regard to heat energy, although analyses indicate that increasing share of natural energy use enhances benefits and boosts competitiveness [

78], our study’s results do not confirm this potential in Polish conditions, as the share of heat energy produced through co-generation has shown almost no change over the past decade.

The mutually reinforcing dynamics of the energy transition are also evident in recent developments in the energy market, where rapid expansion of innovative business models has been observed. Efforts to utilize RES, such as the implementation of photovoltaic, wind or energy storage large-scale projects, are closely linked to the development of microgrids, which have become a key component in enabling efficient management of local energy resources [

79]. As a result, these factors enhance the potential for sustainable competitiveness and conversely, regions with the lowest SMP results clearly postponed or abandoned industrial transformation process due to the lack of proper management focus and ultimately also lost their standing across multiple dimensions.

Although renewable energy technologies were previously considered relatively immature and costly to implement, current developments and future projections often contradict this assumption. The estimation of upfront capital costs represent 84–93% of total project costs for wind, solar, and hydro energy compared to 66–69% and 24–37% for coal and gas, respectively [

80]. In the long term, however, it is expected that the capital expenditures associated mainly with photovoltaic and off-shore wind projects should decrease considerably—from USD 810/kW in 2021 to USD 360/kW in 2050 with respect to photovoltaic, and from USD 3040/kW to USD 1320/kW with respect to off-shore wind projects [

81]. It is argued that despite the initial costs of transition, the use of RES does not hinder growth in the long term. Instead, this process should stimulate economic growth by fostering technological advancements, creating new employment, and attracting substantial investments, ultimately supporting both environmental protection and energy stability [

82].

So far, the findings of our study appear to support the assumption of high implementation costs particularly visible on local societies’ level. The energy poverty level based on low-income high-cost approach (LIHC) increased significantly by 13.8% during the recent decade for the majority of Polish regions (13 out of 16). It should also be noted, however, that for the region which entirely discontinued its energy transition efforts—and consequently could not be assigned to any cluster in 2023—the increase in poverty reached 73%. This finding illustrates that, while the costs associated with the transition are substantial, the consequences of disregarding transformation processes are far more severe. Furthermore, the effects, generally supporting sustainable competitiveness in the long run, are not evenly distributed across regions. This may also be the result of insufficient financial support both on regional and national levels [

83].

6. Conclusions and Implications

This study was directed to evaluate the sustainable competitiveness potential of Polish regions from the perspective of energy-related factors, as well as to identify the trends and disparities observed over the past decade. Our considerations supported by empirical study results lead to several conclusions. Firstly, the measurable growth of sustainable competitiveness potential driven by energy factors was confirmed; however, regularity over time was not observed. Secondly, we also confirmed that certain energy-related factors substantially contribute to regional differences, whereas other indicators exhibit little meaningful variation. The indicators exhibiting the highest degree of differentiation were those associated with the use of RES and the energy balance. Furthermore, an increasing differentiation in energy poverty was observed over time. Finally, we can also affirm that the sustainable competitiveness potential increases over time in relation to energy transformation processes, although the most favorable trends were noted for disaggregated indicators (generation of energy from RES and electricity industrial consumption per unit of gross value added), rather than synthetic ones.

Ultimately, a few limitations of the conducted research should be recognized. The first limitation is mainly deriving from limited continuous data concerning energy factors during 2014–2023, which resulted in reducing the total number of diagnostic variables. The second limitation derives from the geopolitical situation during 2021–2023, which may have influenced the level of poverty due to high energy prices over this period. The final limitation derives from different development stages of some regions. Although the overall situation of Polish regions in 2014 was relatively uniform—each was at the early stage of the energy transition—regions dependent on fossil fuels demonstrated a comparatively advantageous position, largely attributable to their existing infrastructure.

Despite its limitations, this study provides a few interesting practical implications. Firstly, the green transformation, generally increasing the potential for sustainable competitiveness, does not have to imply negative effects on the energy balance on a regional level. Moreover, it appears to enhance or align with both the production-to-consumption ratio improvement and the share of electricity consumption in the industrial value-added creation in the long run. The same pattern is evident for energy consumption in general, as the shift toward RES is associated with more efficient energy use. Secondly, regardless of the identified short-term limitation, local and national authorities should address the uneven economic effects of transformation toward sustainable competitiveness, as these disparities may hinder the development of future potential with regard to local society support.

Additionally, the results of our study indicate that policy and management focus as well as the attitudes towards green transformation play a crucial role in shaping sustainable competitiveness potential—some regions clearly leading, and some still lagging behind the positive trajectory. This is especially important when considering the disparities in transformation effects, which deserve more academic attention, as they may not only depress the overall national performance, but more importantly may lead to regional energy exclusion. In this context, our study provides a comprehensive basis for developing scenarios that incorporate the identified regional disparities and align with the EU’s energy transition targets for 2030 and beyond.