Multifunctional Benzene-Based Solid Additive for Synergistically Boosting Efficiency and Stability in Layer-by-Layer Organic Photovoltaics

Abstract

1. Introduction

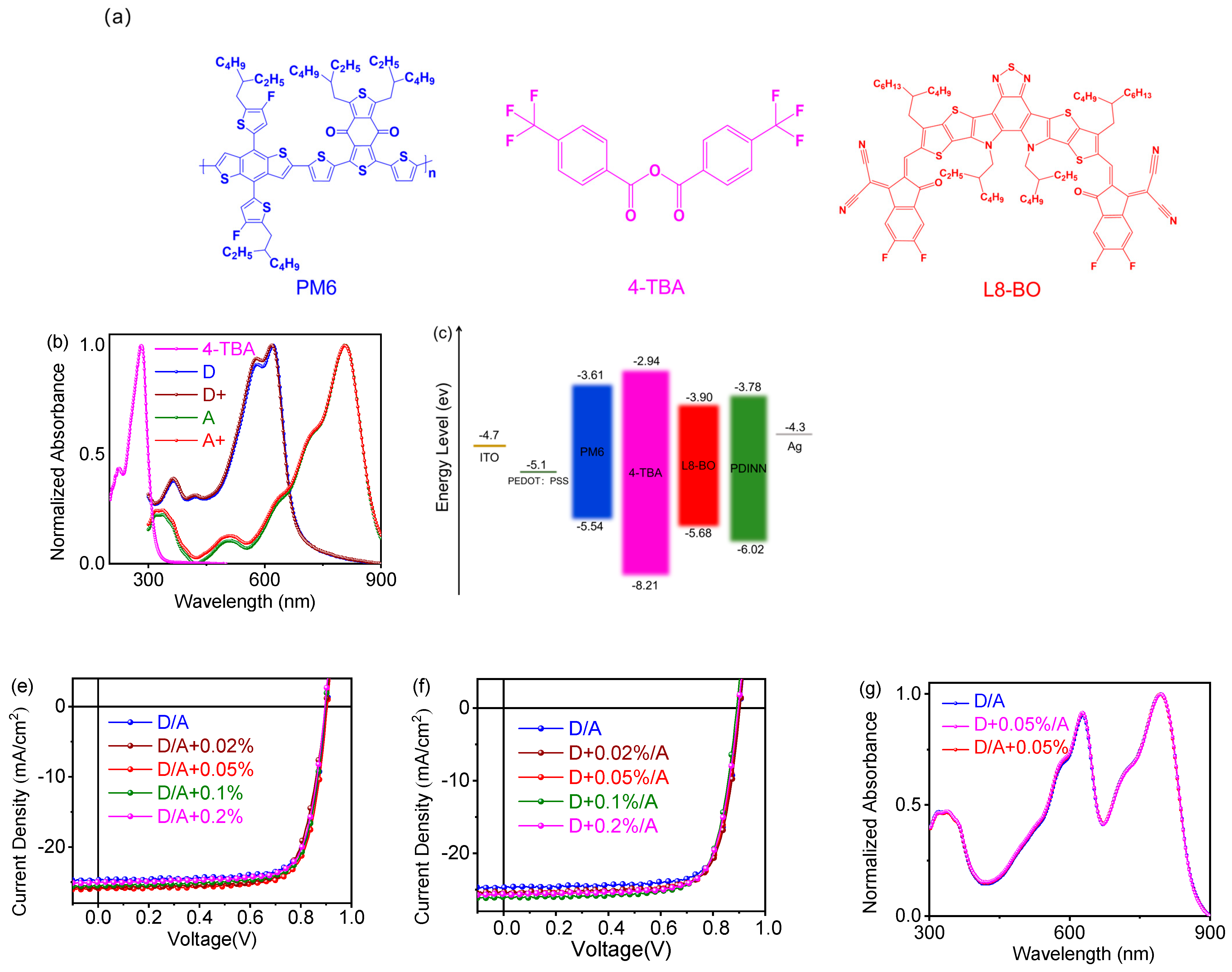

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Processing and Device Fabrication

2.2. Device Characterization

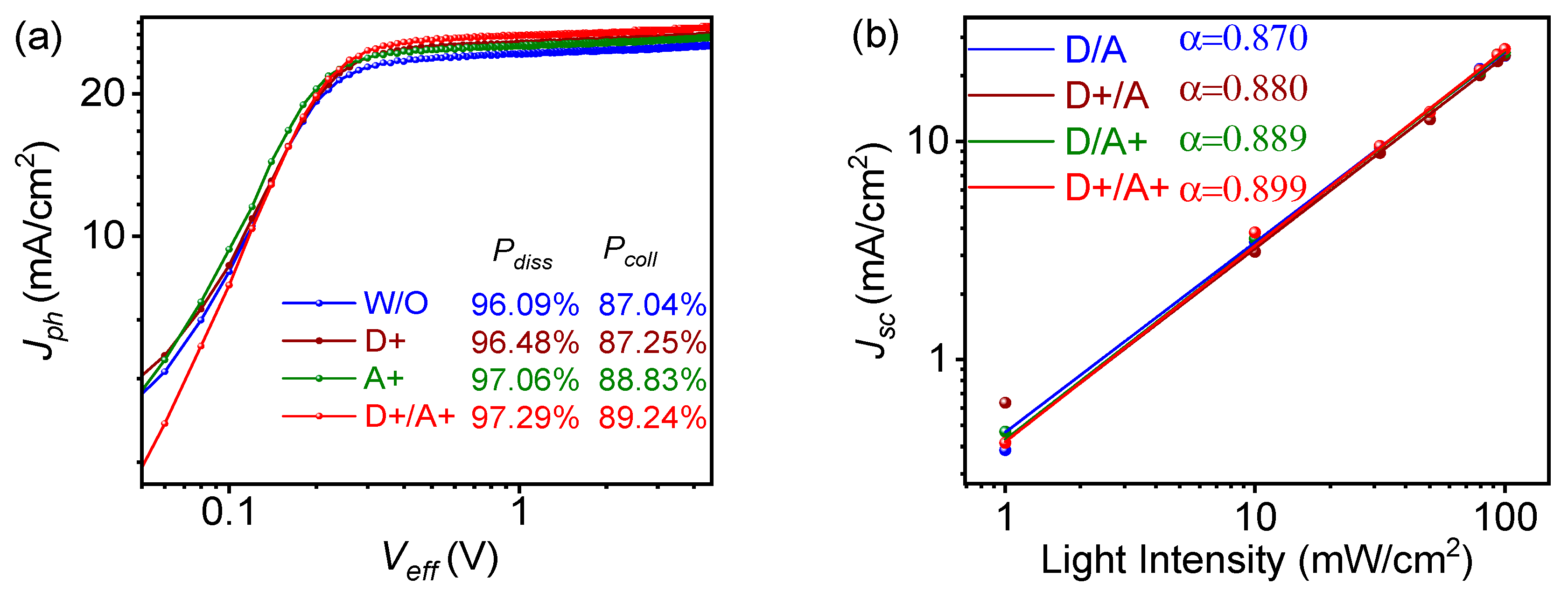

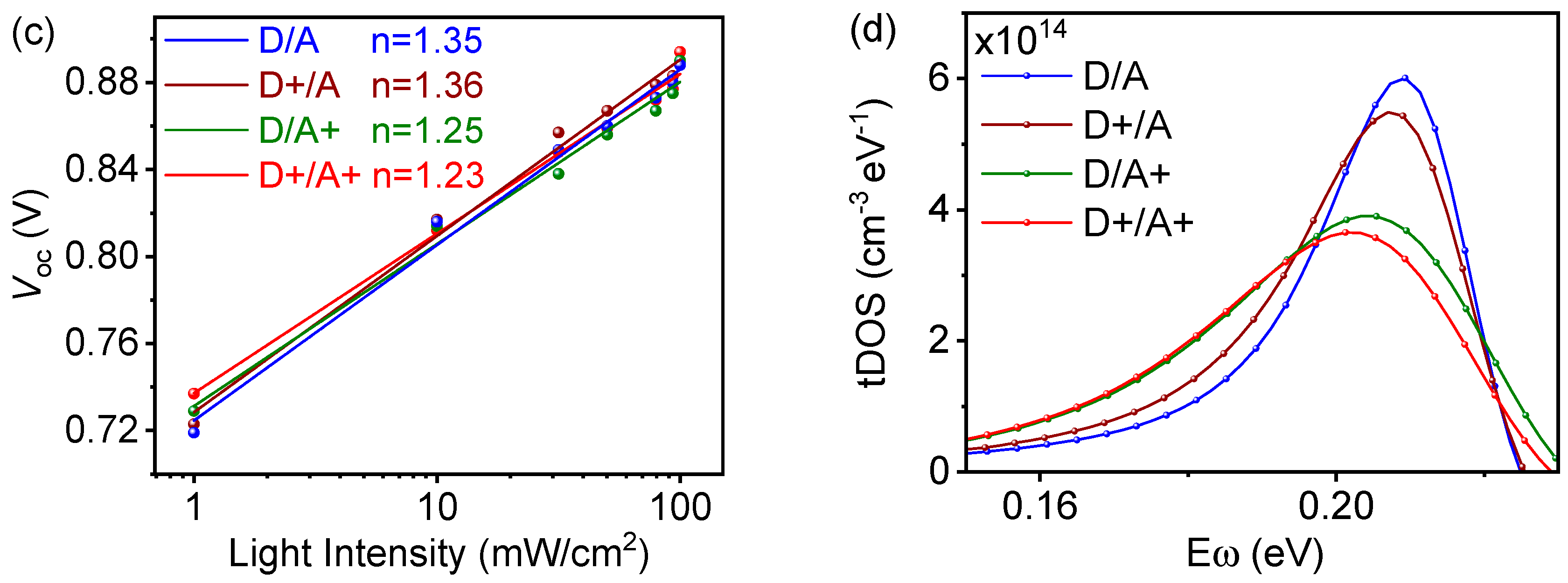

2.3. The Dependence of Jsc and Voc on Plight

2.4. Exciton Dissociation Efficiency (Pdiss) and Charge Collection (Pcoll) Calculation

2.5. The Trapped Density of States (tDOS) Calculation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heeger, A.J. 25th anniversary article: Bulk heterojunction solar cells: Understanding the mechanism of operation. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, J.; Chow, P.C.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Huang, F.; Yan, H. Nonfullerene acceptor molecules for bulk heterojunction organic solar cells. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 3447–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, W.; Zhuang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, X.; Kan, L.; Hao, B. Achieving 20.8% organic solar cells via additive-assisted layer-by-layer fabrication with bulk pin structure and improved optical management. Joule 2024, 8, 3153–3168. Available online: https://www.cell.com/joule/fulltext/S2542-4351(24)00355-6 (accessed on 16 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhu, L.; Xiong, S.; Yu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Tan, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, J.; Kan, L. Boosting Binary Organic Solar Cells Over 20% Efficiency via Synchronous Modulation of Charge Transport and Phase Morphology. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, e04947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Huang, P.; Chen, H.; Fong, P.W.; Dela Peña, T.A.; Li, M.; Lu, X.; Cheng, P. Two-step crystallization modulated through acenaphthene enabling 21% binary organic solar cells and 83.2% fill factor. Nat. Energy 2025, 10, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Xue, J. Recent progress in organic photovoltaics: Device architecture and optical design. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2123–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, L.; Tian, H.; Ni, Y.; Xie, Y.; Jeong, S.Y.; Huang, T.; Woo, H.Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X. Layered All-Polymer Solar Cells with Efficiency of 18.34% by Employing Alloyed Polymer Donors. Small 2025, 21, 2410581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.; Xie, Y.; Xu, W.; Tian, H.; Zhao, X.; Ni, Y.; Jeong, S.Y.; Zou, Y.; Zhu, X. Cascaded energy and charge transfer synergistically prompting 18.7% efficiency of layered organic solar cells with 1.48 eV bandgap. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2404718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; Yip, H.-L.; Hu, B. Self-stimulated dissociation in non-fullerene organic bulk-heterojunction solar cells. Joule 2020, 4, 2443–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Jiang, M.; Mao, P.; Wang, S.; Gui, R.; Wang, Y.; Woo, H.Y.; Yin, H.; Wang, J.L.; An, Q. Manipulating alkyl inner side chain of acceptor for efficient as-cast organic solar cells. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2405718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhuo, Z.; Ma, X.; Tian, H.; Zhao, X.; Xie, Y.; Yang, K.; Lee, B.H.; Zhu, X.; Woo, H.Y. 19.6% efficiency of layer-by-layer organic photovoltaics with decreased energy loss via incorporating TADF materials with intrinsic reverse intersystem crossing. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 9171–9182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhou, H.; Tian, H.; Zhang, L.; Du, J.; Yao, J.; Jeong, S.Y.; Woo, H.Y.; Zhou, E.; Ma, X. Achieving light utilization efficiency of 3.88% and efficiency of 14.04% for semitransparent layer-by-layer organic solar cells by diluting donor layer. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 508, 161148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Jiang, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, B.; Mao, P.; Woo, H.Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, J.-l.; An, Q. Hot-Casting Strategy Empowers High-Boiling Solvent-Processed Organic Solar Cells with Over 18.5% Efficiency. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2305356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Qi, F.; Peng, Z.; Lin, F.R.; Jiang, K.; Zhong, C.; Kaminsky, W.; Guan, Z.; Lee, C.S.; Marks, T.J. Achieving 19% power conversion efficiency in planar-mixed heterojunction organic solar cells using a pseudosymmetric electron acceptor. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2202089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Du, X.; Jeong, S.Y.; Woo, H.Y.; Zhang, F. Over 18.7% efficiency for bulk heterojunction and pseudo-planar heterojunction organic solar cells achieved by regulating intermolecular compatibility. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 24622–24632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Gong, R.; Ni, Y.; Jeong, S.Y.; Zhu, X.; Woo, H.Y.; Ma, X. Over 19.2% Efficiency of Layer-By-Layer Organic Photovoltaics by Ameliorating Exciton Dissociation and Charge Transport. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2422867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhou, C.; Ma, X.; Jeong, S.Y.; Woo, H.Y.; Huang, F.; Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, F. High-Reproducibility Layer-by-Layer Non-Fullerene Organic Photovoltaics with 19.18% Efficiency Enabled by Vacuum-Assisted Molecular Drift Treatment. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2400013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, K.; Yu, H.; Li, J.; Jeong, S.Y.; Woo, H.Y.; Shi, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, X. Improving the Efficiency of Layer-by-Layer Organic Photovoltaics to Exceed 19% by Establishing Effective Donor–Acceptor Interfacial Molecular Interactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 15741–15754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Liao, C.; Duan, Y.; Xu, X.; Yu, L.; Li, R.; Peng, Q. 19.10% Efficiency and 80.5% Fill Factor Layer-by-Layer Organic Solar Cells Realized by 4-Bis (2-Thienyl) Pyrrole-2, 5-Dione Based Polymer Additives for Inducing Vertical Segregation Morphology. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2208279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Sun, S.; Han, T.; Chi, J.; Dong, R.; Han, S.; Zhou, H.; Xu, Y.; Cai, L.; Du, X. Superior charge dynamics via ternary doping layer-by-layer strategy in high-efficiency organic solar cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Kang, H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, K. Effect of processing additives on organic photovoltaics: Recent progress and future prospects. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo, B.; Pérez-Martínez, J.C.; Munoz-Díaz, L.; del Carmen López-González, M.; Martín-Martín, D.; del Pozo, G.; Hernández-Balaguera, E.; Romero, B.; Lamminaho, J.; Turkovic, V. Influence of solvent additive on the performance and aging behavior of non-fullerene organic solar cells. Sol. Energy 2022, 232, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, P.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, J.-l.; An, Q. In-situ volatilization of solid additive assists as-cast organic solar cells with over 20% efficiency. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2025, 165, 101022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chung, S.; Tan, L.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Bai, L.; Lee, H.; Jeong, M.; Cho, K. Molecular order manipulation with dual additives suppressing trap density in non-fullerene acceptors enables efficient bilayer organic solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 2791–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.; Xu, X.; Meng, H.; Xue, J.; Yu, L.; Ma, W.; Peng, Q. Realizing 19.05% efficiency polymer solar cells by progressively improving charge extraction and suppressing charge recombination. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2109516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Zhong, W.; Heumüller, T.; Li, N.; Ying, L.; Brabec, C.J.; Huang, F. Targeted adjusting molecular arrangement in organic solar cells via a universal solid additive. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2205338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Chen, H.; Huang, P.; Yu, Q.; Tang, H.; Chen, S.; Jung, S.; Sun, K.; Yang, C.; Lu, S. Eutectic phase behavior induced by a simple additive contributes to efficient organic solar cells. Nano Energy 2021, 84, 105862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y.; Liang, C.; Xu, Z.; Jing, W.; Xu, X.; Duan, Y.; Li, R.; Yu, L.; Peng, Q. Developing efficient benzene additives for 19.43% efficiency of organic solar cells by crossbreeding effect of fluorination and bromination. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2311512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Ding, K.; Zhuo, H.; Guo, J.; Li, J.; Meng, L.; Ade, H. Introducing a Phenyl End Group in the Inner Side Chains of A-DA’D-A Acceptors Enables High-Efficiency Organic Solar Cells Processed with Nonhalogenated Solvent. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2302946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Xu, X.; Liao, C.; Yu, L.; Li, R.; Peng, Q. Improving cooperative interactions between halogenated aromatic additives and aromatic side chain acceptors for realizing 19.22% efficiency polymer solar cells. Small 2023, 19, 2302127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Bi, P.; Chen, Z.; Qiao, J.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Hao, X. Binary organic solar cells with 19.2% efficiency enabled by solid additive. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2301583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, H.; Xie, J.; Yang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Li, M.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Huang, F. Organic Solar Cell with Efficiency of 20.49% Enabled by Solid Additive and Non-Halogenated Solvent. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2500352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Xie, J.; Bai, Y.; Yang, Z.; Dong, M.; Zhang, K.; Huang, F.; Cao, Y. High Efficiency Non-Halogenated Solvent Processed Organic Solar Cells Through Synergistic Effects of Layer-by-Layer and Solid Additive. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2505226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Li, Y.; Bi, Z.; Lin, Y.; Fu, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, M.; Ma, W.; Xia, J.; Ma, Z. Fine-tuning the hierarchical morphology of multi-component organic photovoltaics via a dual-additive strategy for 20.5% efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xu, J.; Ma, Y.; Ahn, Y.; Du, X.; Yang, E.; Xia, H.; Lee, B.R.; Hangoma, P.M.; Park, S.H. Functional design and understanding of effective additives for achieving high-quality perovskite films and passivating surface defects. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 102, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Du, X.; Ma, Y.; Qiao, J.; Zheng, Q.; Hao, X. Revealing Design Rules for Improving The Photostability of Non-Fullerene Acceptors from Molecular to Aggregation Level. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2308591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TBA in Donor [wt%] | Voc [V] | Jsc [mA/cm2] | FF [%] | PCE (a) [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.900 (0.898 ± 0.003) | 24.71 (24.58 ± 0.15) | 76.65 (76.50 ± 0.51) | 17.05 (16.82 ± 0.23) |

| 0.02 | 0.900 (0.898 ± 0.003) | 25.35 (24.71 ± 0.43) | 76.42 (75.81 ± 0.32) | 17.44 (17.11 ± 0.32) |

| 0.05 | 0.896 (0.896 ± 0.003) | 25.66 (25.05 ± 0.35) | 76.00 (76.06 ± 0.25) | 17.47 (17.29 ± 0.18) |

| 0.1 | 0.890 (0.895 ± 0.004) | 26.03 (24.90 ± 0.34) | 75.12 (74.92 ± 0.34) | 17.40 (17.18 ± 0.13) |

| 0.2 | 0.896 (0.896 ± 0.004) | 25.61 (24.78 ± 0.46) | 75.45 (74.81 ± 0.28) | 17.31 (17.08 ± 0.21) |

| 4-TBA in Acceptor [wt%] | Voc [V] | Jsc [mA/cm2] | FF [%] | PCE (a) [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.900 (0.898 ± 0.003) | 24.71 (24.58 ± 0.15) | 76.65 (76.50 ± 0.51) | 17.05 (16.82 ± 0.23) |

| 0.02 | 0.896 (0.896 ± 0.003) | 25.77 (25.12 ± 0.25) | 75.03 (75.01 ± 0.35) | 17.32 (17.18 ± 0.14) |

| 0.05 | 0.907 (0.898 ± 0.004) | 25.91 (25.33 ± 0.38) | 76.17 (75.58 ± 0.38) | 17.90 (17.55 ± 0.35) |

| 0.1 | 0.896 (0.896 ± 0.003) | 25.52 (25.21 ± 0.25) | 76.67 (76.16 ± 0.41) | 17.53 (17.31 ± 0.21) |

| 0.2 | 0.896 (0.896 ± 0.002) | 24.99 (25.01 ± 0.31) | 76.82 (76.08 ± 0.33) | 17.20 (17.03 ± 0.17) |

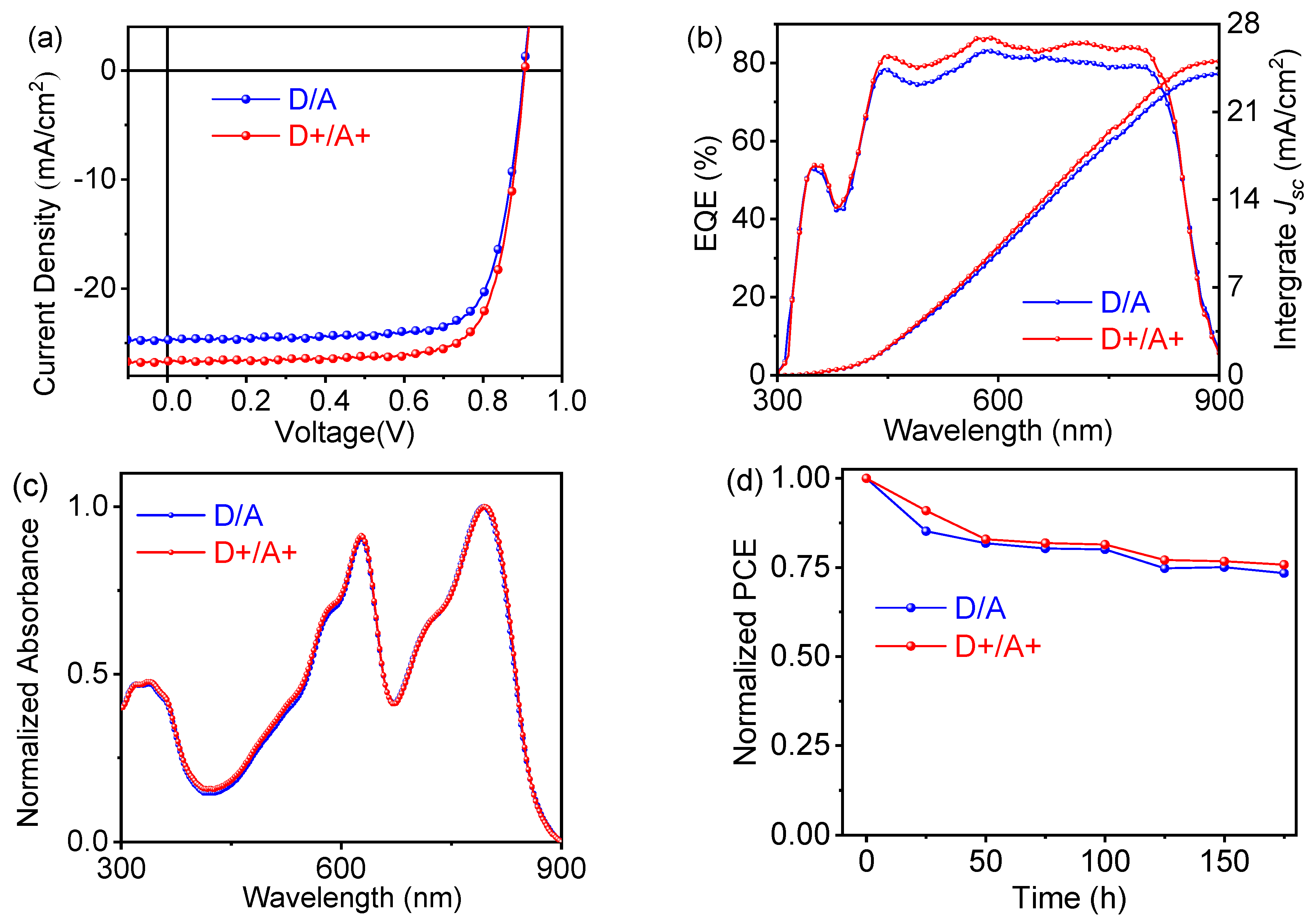

| Active Layer | Voc [V] | Jsc [mA/cm2] | Cal. Jsc [mA/cm2] | FF [%] | PCE (a) [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D/A | 0.900 (0.898 ± 0.003) | 24.71 (24.58 ± 0.15) | 24.02 | 76.65 (76.50 ± 0.51) | 17.05 (16.82 ± 0.23) |

| D+/A+ | 0.907 (0.899 ± 0.005) | 26.65 (25.65 ± 0.44) | 25.04 | 76.51 (75.69 ± 0.44) | 18.49 (18.02 ± 0.30) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, J.; He, P.; Xie, W.; Xie, Y.; Fu, Y.; Huang, S.; Lai, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, X. Multifunctional Benzene-Based Solid Additive for Synergistically Boosting Efficiency and Stability in Layer-by-Layer Organic Photovoltaics. Energies 2026, 19, 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010211

Li J, He P, Xie W, Xie Y, Fu Y, Huang S, Lai G, Wang Z, Zhang F, Zhu X. Multifunctional Benzene-Based Solid Additive for Synergistically Boosting Efficiency and Stability in Layer-by-Layer Organic Photovoltaics. Energies. 2026; 19(1):211. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010211

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Junchen, Peng He, Wuchao Xie, Yujie Xie, Yongquan Fu, Shutian Huang, Guojuan Lai, Zhen Wang, Fujun Zhang, and Xixiang Zhu. 2026. "Multifunctional Benzene-Based Solid Additive for Synergistically Boosting Efficiency and Stability in Layer-by-Layer Organic Photovoltaics" Energies 19, no. 1: 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010211

APA StyleLi, J., He, P., Xie, W., Xie, Y., Fu, Y., Huang, S., Lai, G., Wang, Z., Zhang, F., & Zhu, X. (2026). Multifunctional Benzene-Based Solid Additive for Synergistically Boosting Efficiency and Stability in Layer-by-Layer Organic Photovoltaics. Energies, 19(1), 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010211