Distributionally Robust Game-Theoretic Optimization Algorithm for Microgrid Based on Green Certificate–Carbon Trading Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

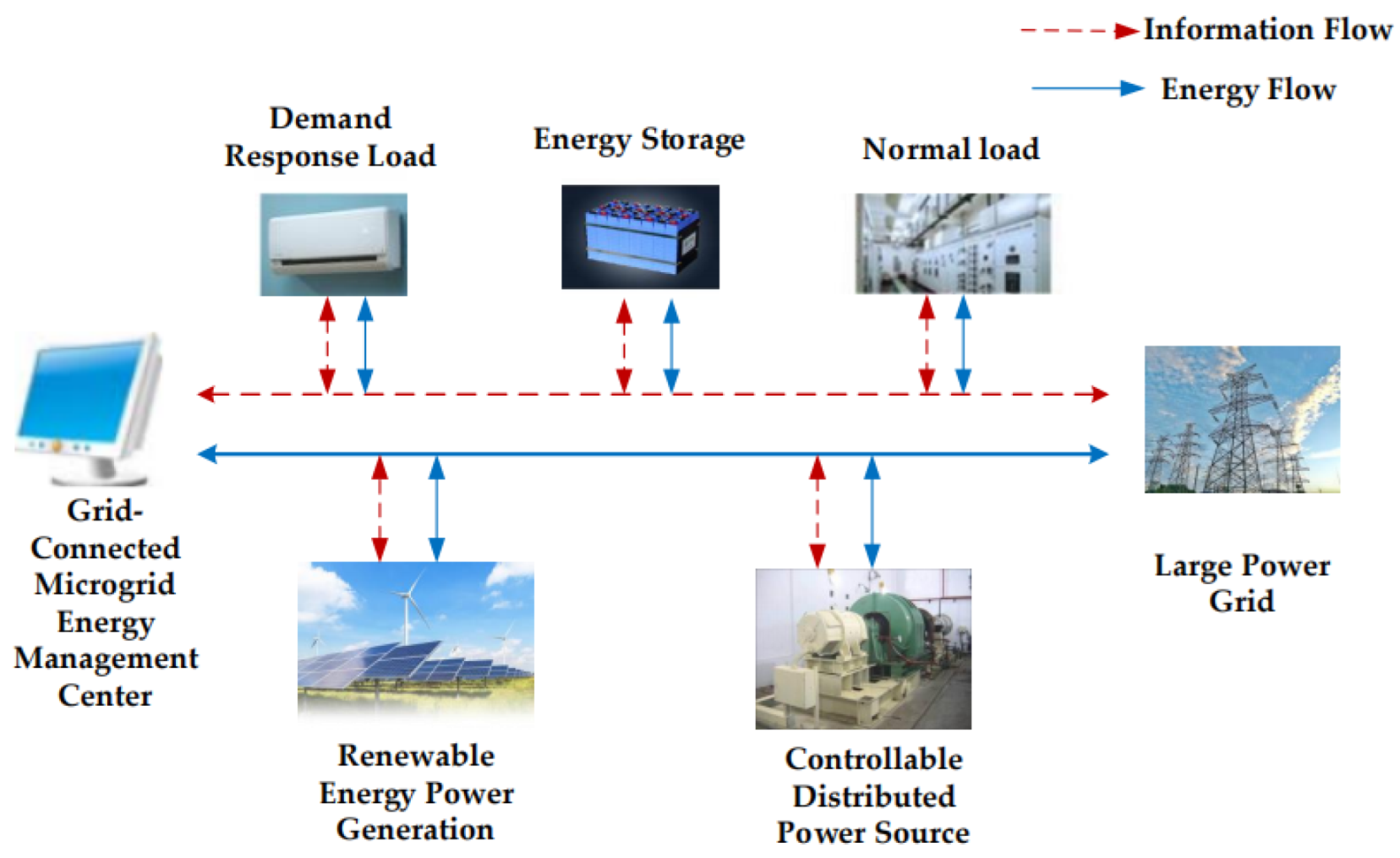

2. Microgrid Model

2.1. The Structure of Microgrid

2.2. Micro Gas Turbine

2.3. Energy Storage Unit

2.4. Demand Response Load

2.5. Power Interaction with Large Grid

2.6. Stepwise Carbon Trading Mechanism

2.7. Green Certificate Trading Mechanism

2.8. Renewable Energy Generator

2.9. Objective Function

3. Distributionally Robust Game-Theoretic Optimization Algorithm for Microgrid Based on Green Certificate–Carbon Trading Mechanism (GCDRGO)

3.1. Construction of Multi-Agent Game Model for Microgrid

3.2. Two-Stage Distribution-Robust Optimization Model

3.2.1. Construction of Probabilistic Fuzzy Sets

3.2.2. Distribution-Robust Optimization Model

3.2.3. Solving Methods of Two-Stage Distribution-Robust Optimization

3.3. Flowchart of GCDRGO Algorithm

4. Simulation and Analysis

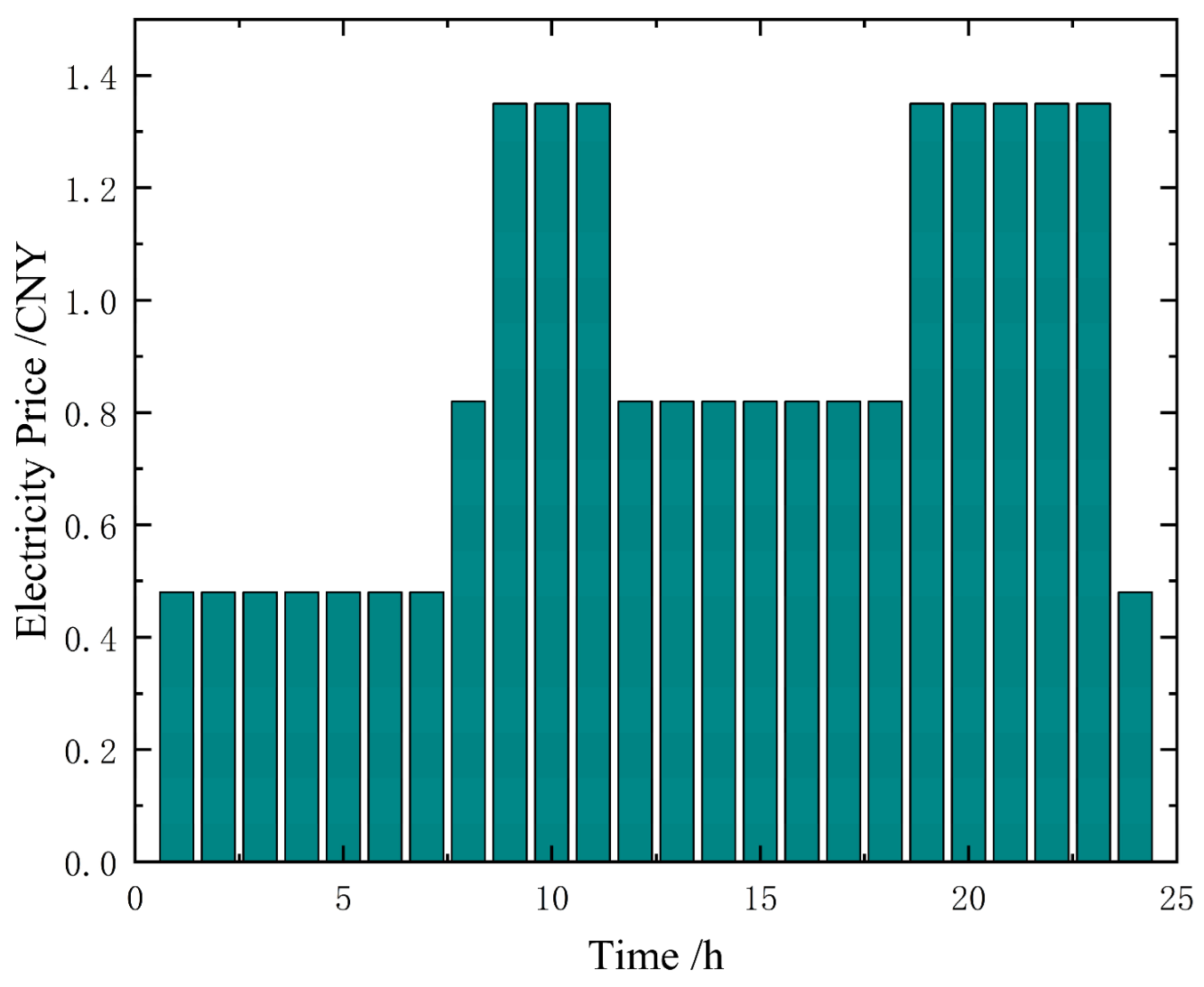

4.1. Parameter Settings

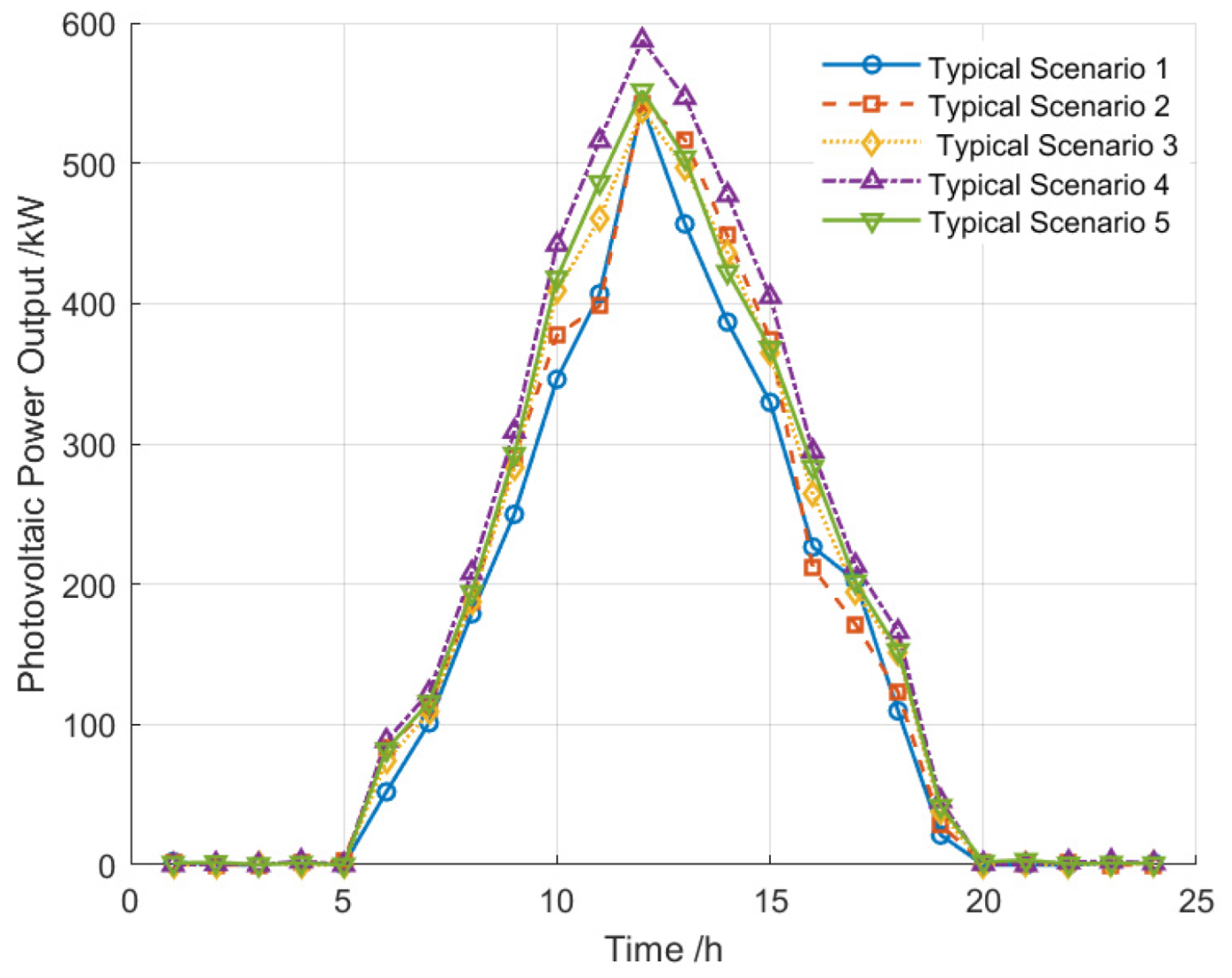

4.2. Analysis of Scenario Generation

4.3. Analysis of Optimization Results

4.3.1. Optimized Dispatch Results for Microgrid

4.3.2. Comparison Analysis of Different Optimization Run Results

4.4. Analysis of the Green Certificate–Carbon Trading Mechanism

4.4.1. Impact Analysis of Different Renewable Energy Quota Coefficients

4.4.2. Impact Analysis of Different Stepwise Carbon Price Growth Rates

4.5. Analytical Comparison of GCDRGO Optimization Models

4.5.1. Comparative Analysis of Scheduling Results at Different Confidence Levels

4.5.2. Analysis of the Impact of Different Numbers of Historical Scenarios on Optimization Results

5. Conclusions

- Through combining kernel density estimation and copula functions, it can generate typical scenarios and probabilistic fuzzy sets that account for wind–solar correlation to enhance the accuracy of probabilistic fuzzy sets.

- The introduction of the green certificate–carbon trading mechanism can enhance microgrid utilization of renewable energy, achieving energy saving and emission reduction. Analyzing the green certificate–carbon trading mechanism shows the impact of changes in the renewable energy quota coefficient and the carbon trading price growth rate on the environmental and economic benefits of the system. Therefore, appropriate parameters for the green certificate–carbon trading mechanism must be established to significantly enhance the microgrid’s low-carbon economic performance.

- This algorithm synthesizes non-cooperative complete information dynamic games with distributional robust optimization for the solution. The Nash equilibrium solution is found by a non-cooperative dynamic game of complete information, and the strategy of each agent is formulated by distributed robust optimization. It can not only effectively utilize historical scenario data to optimize microgrid performance and enhance computational efficiency but also realize the balance of interests among gas turbines, renewable energy generators, and energy storage units.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, J. Two layer method of microgrid optimal sizing considering demand-side response and uncertainties. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2018, 33, 3284–3295. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; Wang, J. Online optimal scheduling of a microgrid based on deep reinforcement learning. Control Decis. 2022, 37, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C.; Tang, Y.; Dai, J.; Wang, C.; Wu, S. Uncertainty modeling of wind power frequency regulation potential considering distributed characteristics of forecast errors. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2021, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thale, S.S.; Wandhare, R.G.; Agarwal, V. A novel reconfigurable microgrid architecture with renewable energy sources and storage. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2015, 51, 1805–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tang, Z.; Lu, J.; Mei, G.; Li, Z.; Shi, C. Research on optimal dispatch of a microgrid based on CVaR quantitative uncertainty. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2021, 49, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, B.; Han, X.; Li, W.; Guo, L.; Yu, H. Multi-time scale stochastic optimal dispatch for AC/DC hybrid microgrid incorporating multi-scenario analysis. High Volt. Eng. 2020, 46, 2359–2369. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, X.; Fu, S. Day-ahead stochastic optimization method of microgrid considering the correlation of wind power. J. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2022, 5, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Xu, X.; Yan, Z.; Wu, J.; Sang, D.; Wang, S. Overview on data-driven optimal scheduling methods of power system in uncertain environment. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2020, 44, 172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, C. Economic dispatch of microgrid based on two stage robust optimization. Proc. CSEE 2018, 38, 4013–4022+4307. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, B.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhu, J.; Wang, R. Two-stage robust optimal scheduling of grid connected microgrid in expected scenario. Proc. CSEE 2020, 40, 6161–6173. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, B.; Peng, J.; Wei, W.; Yao, Y. Two-stage optimal configuration of microgrid based on fuzzy scene clustering. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. 2023, 57, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T.; Wu, L. Distributionally robust scheduling of integrated gas-electricity systems with demand response. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 3791–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.Y.; Lin, S.J.; Liu, W.B.; Liang, W.; Liu, M. Distributionally robust optimal dispatch of offshore wind farm cluster connected by VSC MTDC considering wind speed correlation. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Long, M.; Zhong, J.; Li, Y. Day-ahead economic operation model of microgrid and its solving method based on distributed robust optimization. Proc. CSU-EPSA 2022, 34, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wei, W.; Liu, F.; Mei, S. Distributionally robust hydrothermal-wind economic dispatch. Appl. Energy 2016, 173, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zeng, J.; Liu, J.; Xue, F. Distributionally robust optimization method for grid connected microgrid considering extreme scenarios. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Han, M.; Shahidehpour, M.; Li, J.; Long, C. Data-driven distributionally robust scheduling of community integrated energy systems with uncertain renewable generations considering integrated demand response. Appl. Energy 2023, 335, 120749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yu, S.; Li, L.; Hou, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, W. Low-carbon and economic configuration method for solar hydrogen storage microgrid including stepped carbon trading. High Volt. Eng. 2022, 48, 2523–2533. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, G.; Liu, P.; Jia, X.; Dong, J.; Fang, F. Economic optimal scheduling considering tradable green certificate system. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2021, 42, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Optimization configuration method for hybrid energy storage capacity of electricity-hydrogen-gas for new power system under the green certificate carbon trading mechanism. Distrib. Util. 2024, 41, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, J.; Mei, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, W.; Zhang, L. Optimal scheduling of multi-subject and multi-park cooperative game considering carbon-green certificate. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2024, 44, 129–135+153. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Ren, Y.; Zhu, R.; He, B.; Fang, C.; Pan, Y. Low car bon economic dispatch of IES based on green certificate-carbon trading interaction mechanism and cooperative game theory. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M. Robust optimal scheduling method of multi-scenario source-network-load- energy storage robust-game based on carbon-green certificate trading mechanisms. Power Syst. Technol. 2024. Available online: https://link.oversea.cnki.net/doi/10.13335/j.1000-3673.pst.2024.1387 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Zeng, B.; Zhao, L. Solving two-stage robust optimization problems using a column-and- constraint generation method. Oper. Res. Lett. 2013, 41, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Tao, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Teng, X.; Zhu, H.; Fu, Z. Life cycle optimal charging strategy based on the SOH of power lithiumion battery. J. Electr. Power Sci. Technol. 2022, 37, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Y.; Song, H.; Yang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Lu, G. Charge and discharge characteristics analysis of lithium battery based on second-order RC model. High Volt. Appar. 2023, 59, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Bian, Y.; Xu, Q.; Kong, X. Distributional robust optimal dispatching of microgrid considering risk and carbon trading mechanism. High Volt. Eng. 2024, 50, 3477–3487. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Chen, L.; Mei, S. Typical applications and prospects of game theory in power system. Proc. CSEE 2014, 34, 5009–5017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, J.; Liu, J. Research on optimization algorithm of microgrid energy management system based on non-cooperative game theory. Power Syst. Technol. 2016, 40, 387–395. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Li, H. Typical scene generation of wind and photovoltaic power output based on kernel density estimation and Copula function. Electr. Eng. 2022, 23, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zheng, P.; Qin, H.; Wang, Y. Robust economic optimization of microgrid based on scenario probability distribution un certainty and probability combination scenario performance. J. Electr. Power Sci. Technol. 2024, 39, 187–200. [Google Scholar]

| Equipment | Parameters | Numerical Value |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | ||

| 500 | ||

| Micro gas turbine | 300 | |

| 0.5 | ||

| 0.15 | ||

| 250 | ||

| 900 | ||

| Energy storage unit | 200 | |

| 500 | ||

| 0.38 | ||

| 0.95 | ||

| 35 | ||

| Demand response load | 200 | |

| 1800 | ||

| 0.32 |

| Plan | Total Cost/CNY | Carbon Trading Cost/CNY | Green Certificate Transaction Cost/CNY | Energy Storage Unit Cost/CNY | Carbon Emissions/kg | Renewable Energy Utilization Rate/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRO | 5292.77 | - | - | 708.63 | 45.94 | 34.65 |

| GCDRO | 4853.26 | 344.26 | −457.28 | 524.62 | 33.83 | 72.57 |

| GCDRGO | 4993.57 | 310.28 | −385.46 | 477.31 | 27.46 | 67.37 |

| Total Cost for Different Confidence Levels/CNY | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.20 | 4961.34 | 4993.57 | 5026.55 |

| 0.50 | 4999.74 | 5006.19 | 5052.54 |

| 0.99 | 5012.45 | 5031.79 | 5076.52 |

| Number of Scenarios | Total Cost/CNY |

|---|---|

| 500 | 4993.57 |

| 2000 | 4863.56 |

| 5000 | 4808.78 |

| 10000 | 4787.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, C.; Zheng, P.; Xue, J.; Song, G.; Wang, D. Distributionally Robust Game-Theoretic Optimization Algorithm for Microgrid Based on Green Certificate–Carbon Trading Mechanism. Energies 2026, 19, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010206

Wei C, Zheng P, Xue J, Song G, Wang D. Distributionally Robust Game-Theoretic Optimization Algorithm for Microgrid Based on Green Certificate–Carbon Trading Mechanism. Energies. 2026; 19(1):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010206

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Chen, Pengyuan Zheng, Jiabin Xue, Guanglin Song, and Dong Wang. 2026. "Distributionally Robust Game-Theoretic Optimization Algorithm for Microgrid Based on Green Certificate–Carbon Trading Mechanism" Energies 19, no. 1: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010206

APA StyleWei, C., Zheng, P., Xue, J., Song, G., & Wang, D. (2026). Distributionally Robust Game-Theoretic Optimization Algorithm for Microgrid Based on Green Certificate–Carbon Trading Mechanism. Energies, 19(1), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010206