Demand Response Potential Evaluation Based on Multivariate Heterogeneous Features and Stacking Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To enhance model evaluation performance, multidimensional feature indicators are extracted from users’ historical electricity consumption data and associated external environments, ensuring effective representation of critical information relevant to demand response potential and providing the model with clear learning patterns.

- (2)

- To further expand the model’s information space, typical daily electricity consumption curves are transformed into image-based features and jointly utilized with indicator features in the evaluation process. The incorporation of image features enriches the input data modality and enables the model to more deeply uncover latent behavioral characteristics.

- (3)

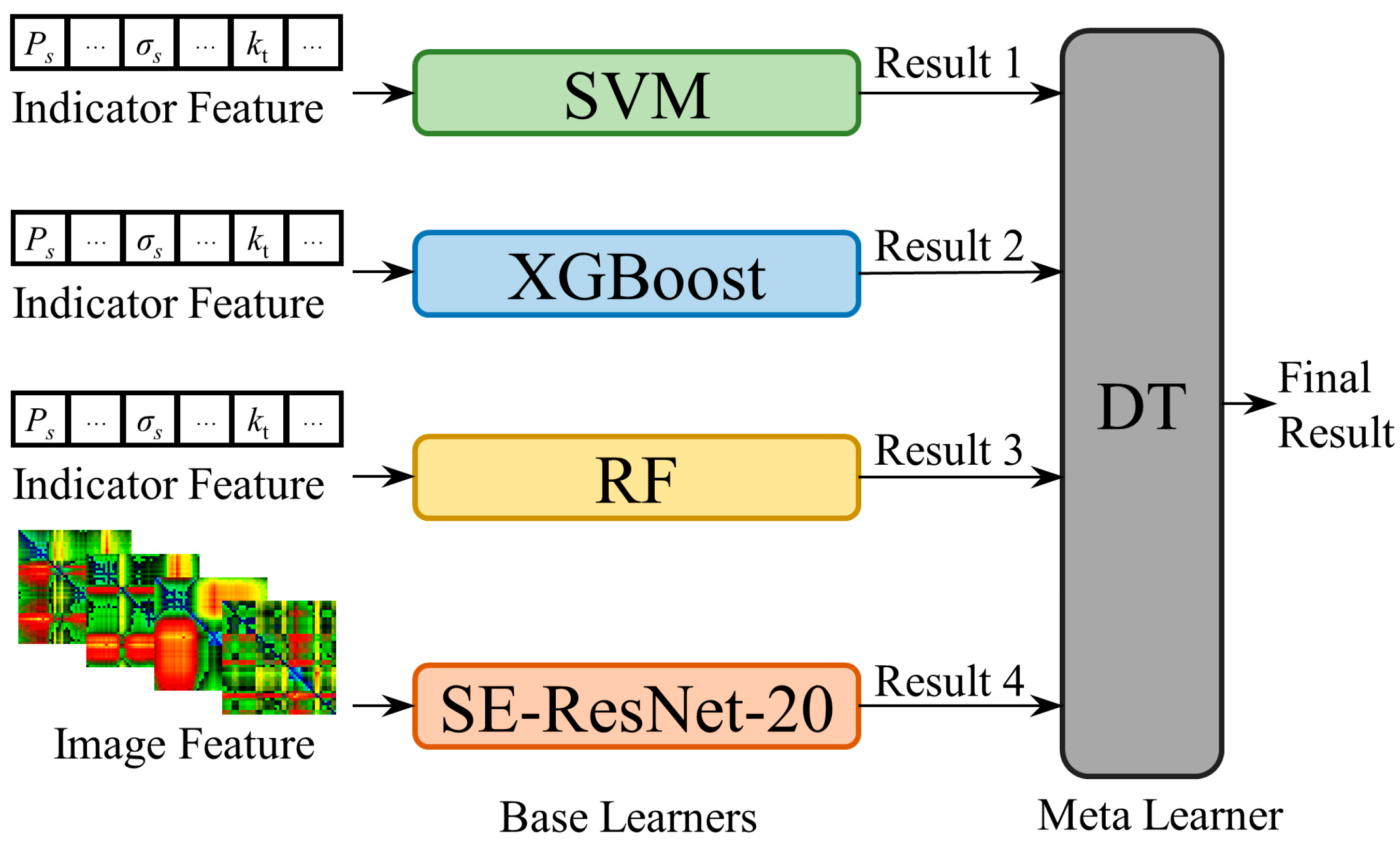

- To address the fusion challenge of heterogeneous features, a differentiated input strategy is proposed. For scalar indicators, multiple classical machine learning models are employed; for image-based features, an SE-ResNet-20 model integrating a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) module is introduced. Finally, a Stacking ensemble mechanism is adopted to effectively integrate the outputs of sub-models, thereby further improving evaluation performance.

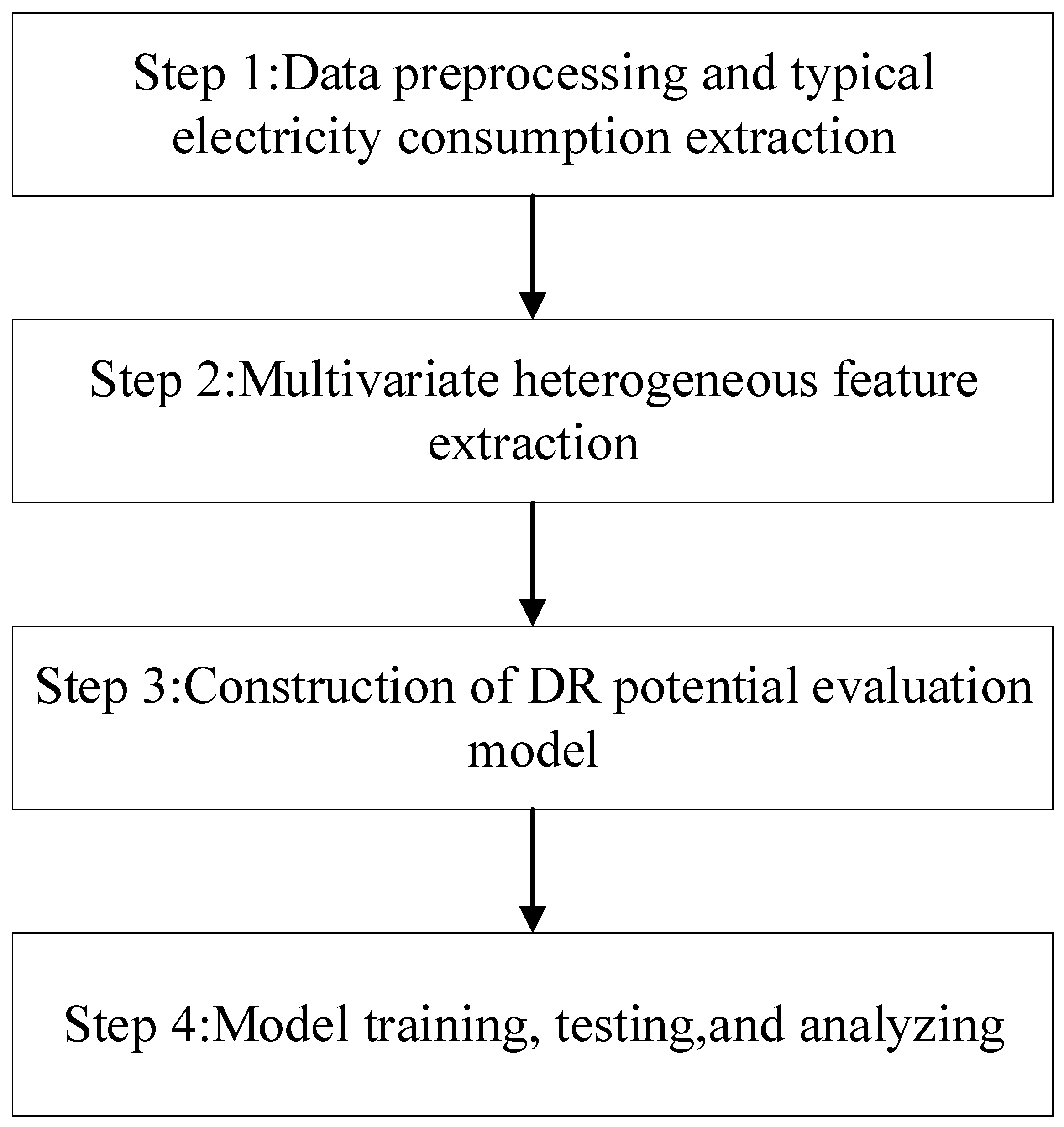

2. Framework for Demand Response Potential Evaluation

- (1)

- Preprocess raw data to obtain typical daily electricity consumption curves for individual users.

- (2)

- Extract multivariate feature indicator features that characterize the demand response potential. Furthermore, the typical daily electricity consumption curve is transformed into image features, which, together with the multivariate indicator features, are used in the evaluation of demand response potential.

- (3)

- Construct the demand response potential evaluation model using Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, and SE-ResNet-20 as base learners, and Decision Tree (DT) as the meta learner. Specifically, image features are input into SE-ResNet-20, while indicator features are input into the other base learners.

- (4)

- Train the demand response potential evaluation model based on both multivariate feature indicators and graphical features, followed by an analysis of the results.

3. Heterogeneous Demand Response Potential Feature Extraction

3.1. Data Preprocessing

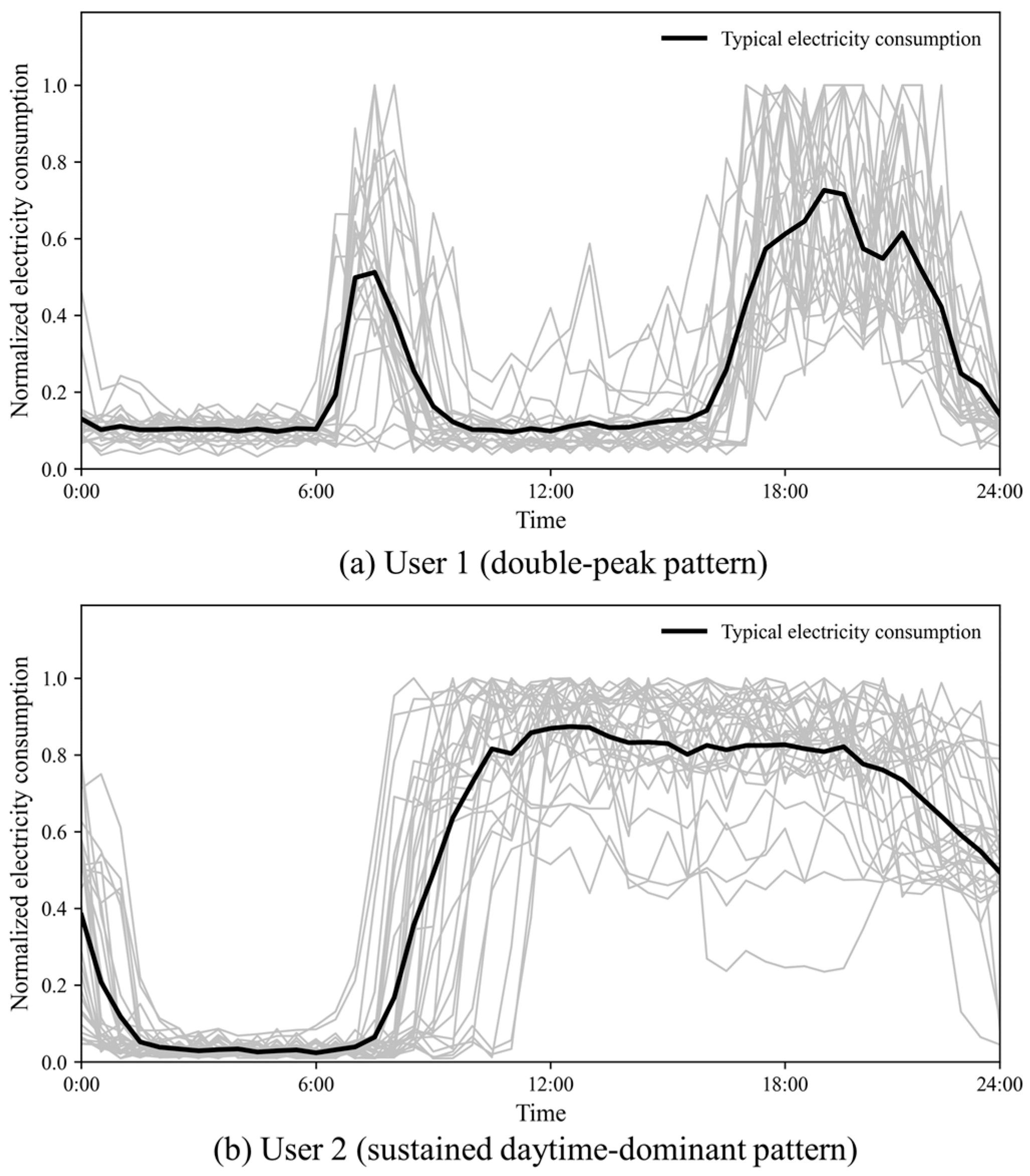

3.2. Acquisition of Typical Daily Electricity Consumption Curves

3.3. Extraction of Multivariate Indicator Feature

- (1)

- Load Shape Features

- (2)

- Load Variability Features

- (3)

- Load Correlation Features

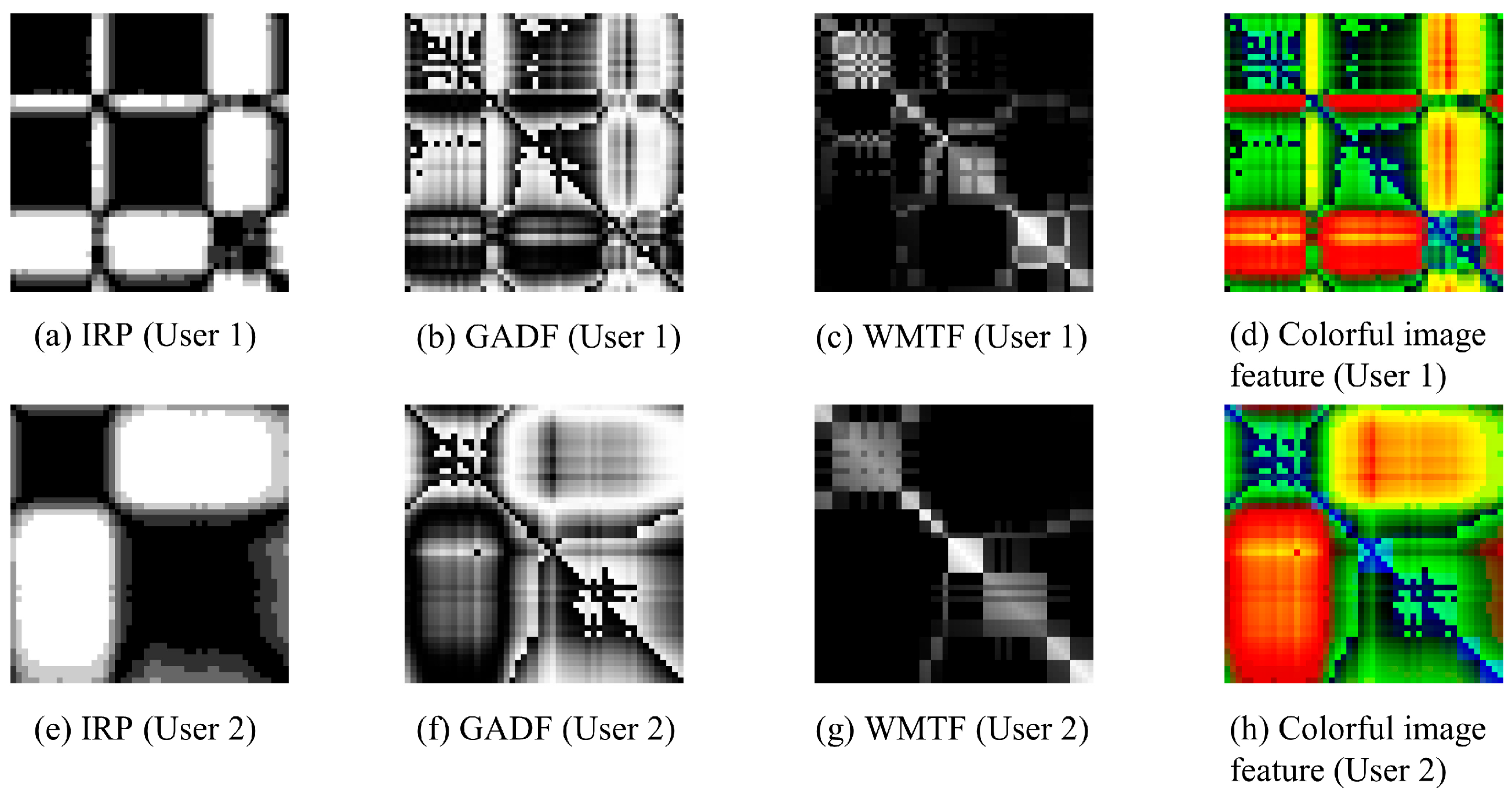

3.4. Image Feature Extraction

- (1)

- Improved Recurrence Plot

- (2)

- Gramian Angular Field

- (3)

- Markov Transition Field

4. Demand Response Potential Evaluation Model Construction

4.1. Traditional Machine Learning Methods

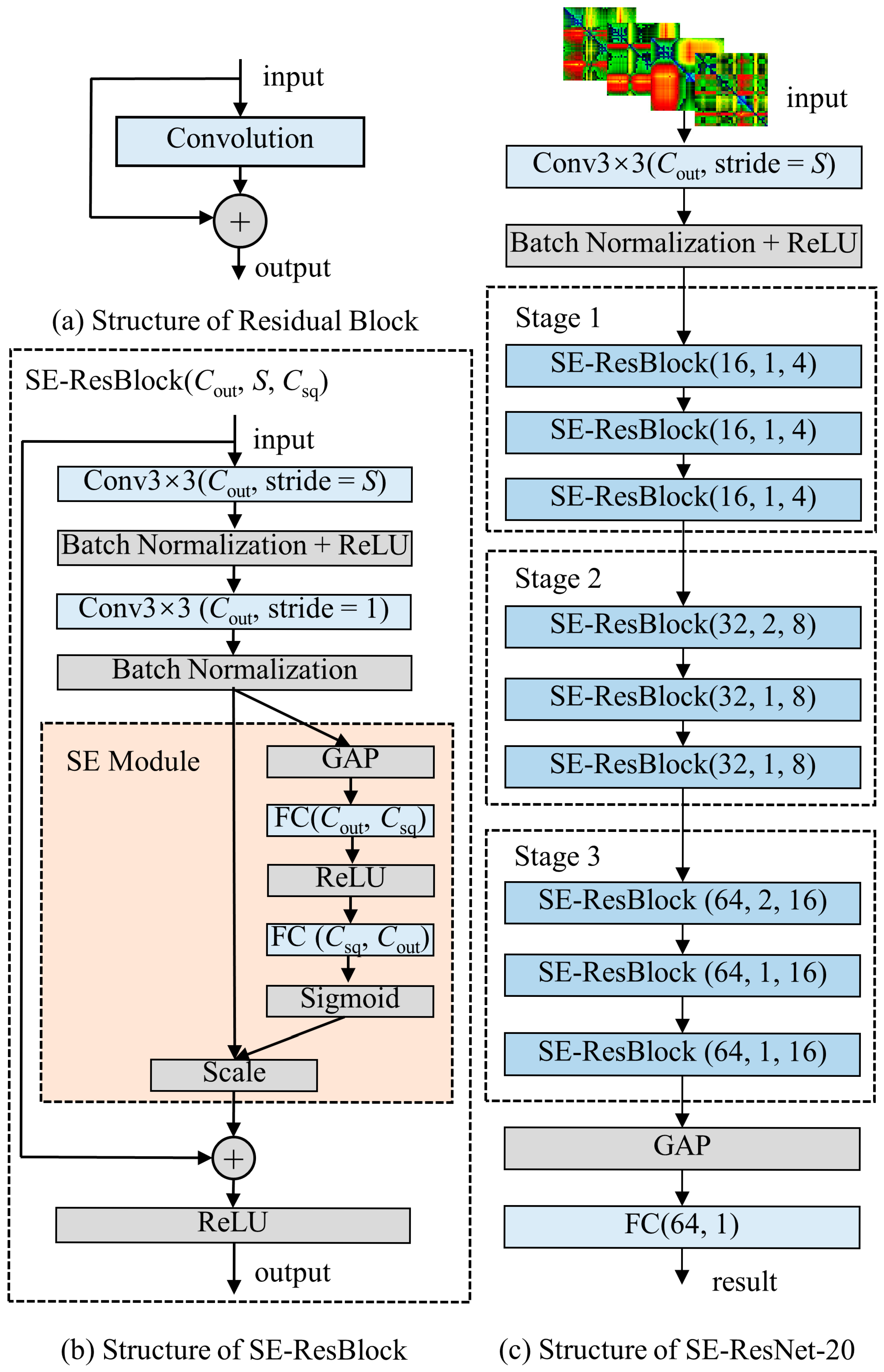

4.2. SE-ResNet Convolutional Neural Network

4.3. Demand Response Potential Evaluation Model Based on Heterogeneous Base Stacking Mechanism

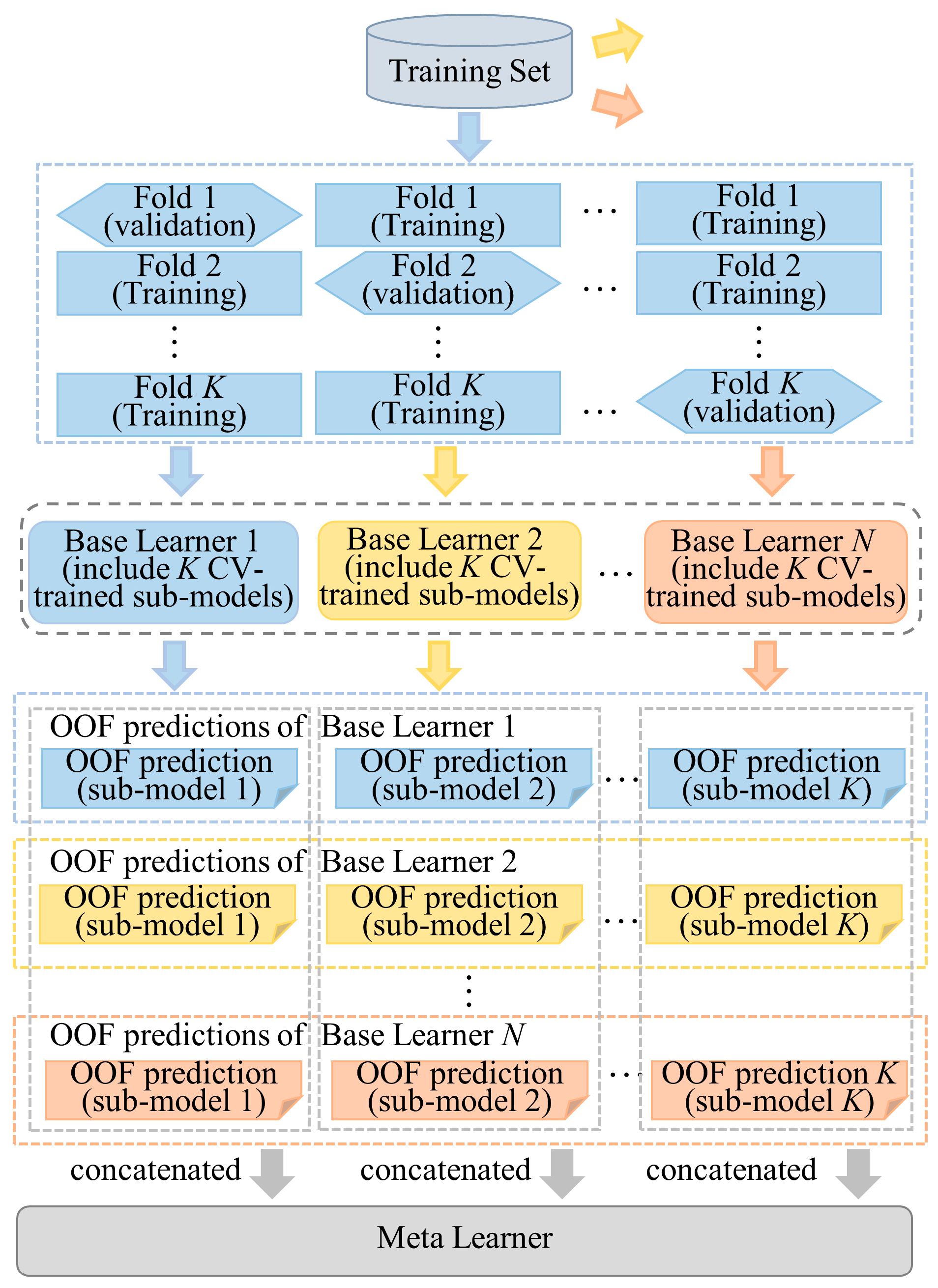

- (1)

- Split the training set into K folds.

- (2)

- Perform K rounds of training for each base learner. In each round, one fold is used as the validation set while the remaining K − 1 folds are used for training. Collect the predictions from the validation set after each training round to obtain the out-of-fold (OOF) predictions for the entire training set.

- (3)

- Repeat the above step for all base learners to gather their respective OOF predictions across the training set. These predictions are then concatenated and used as training samples for the meta learner.

- (4)

- During Inference, each base learner’s K sub-models trained during the cross-validation phase are used to make predictions on the test sample. The average of these predictions forms the final prediction for that base learner. The predictions from all base learners are then concatenated and fed into the meta learner, which outputs the final result.

5. Experimental Result and Discussion

5.1. Dataset and Label Calculation

5.2. Experimental Setup

5.3. Metrics for Model Evaluation

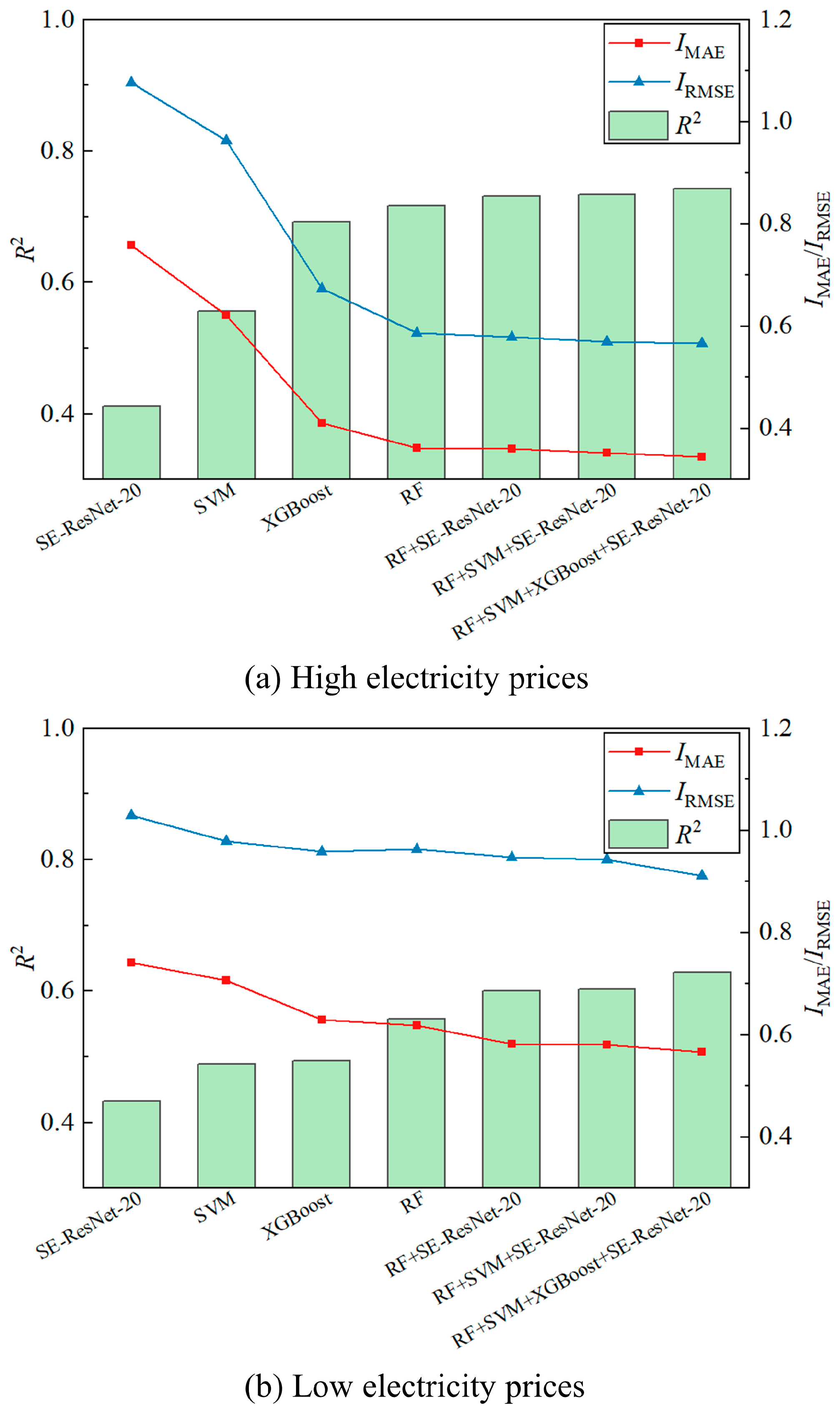

5.4. Comparative Experimental Results

5.5. Stacking Framework Performance Comparison

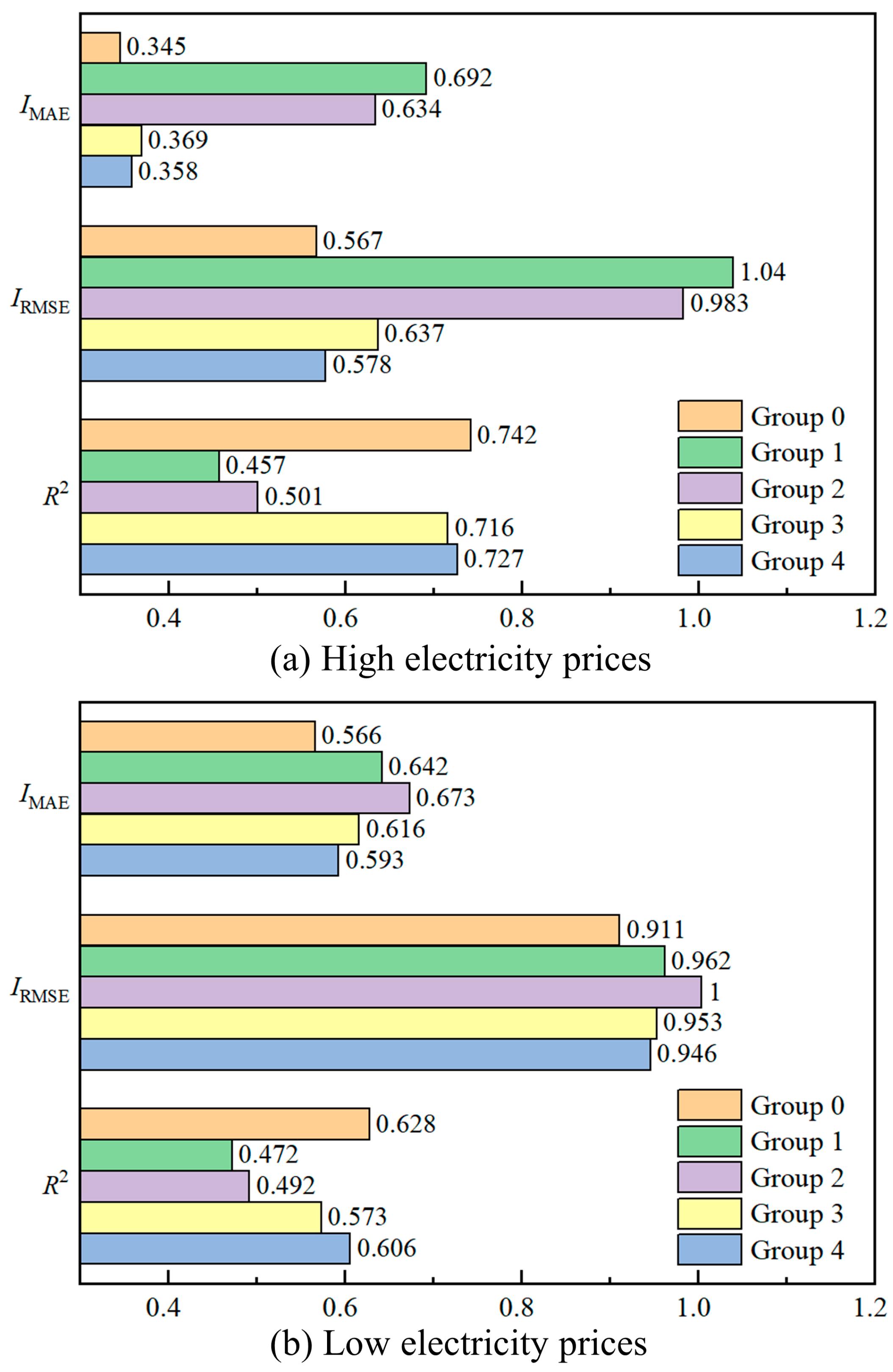

5.6. Ablation Studies

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Further exploration of intrinsic load characteristics and features related to external influencing factors will be conducted. Based on these features, preprocessing strategies will be optimized, and systematic feature evaluation and selection will be performed to identify the most suitable input features for different heterogeneous models.

- (2)

- Lightweight image feature representations or adaptive feature activation mechanisms will be investigated to reduce the computational burden of the models.

- (3)

- The proposed method will be further validated and analyzed in a wider range of real-world scenarios, and insights gained from these results will be used to continuously refine the framework and improve its overall performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prasad, M.B.; Ganesh, P.; Kumar, K.V.; Mohanarao, P.A.; Swathi, A.; Manoj, V. Renewable Energy Integration in Modern Power Systems: Challenges and Opportunities. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2024; Volume 591, p. 03002. [Google Scholar]

- Pinson, P.; Madsen, H. Benefits and challenges of electrical demand response: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, J.; Alizadeh, M.I. Demand response in smart electricity grids equipped with renewable energy sources: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 18, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cheng, B.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; Kong, X. Data-Driven Demand Response Potential Assessment and Adjustable Load Optimization Scheduling. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 25th China Conference on System Simulation Technology and its Application (CCSSTA), Tianjin, China, 21–23 July 2024; pp. 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.B.; Xu, P.; Wang, X.Y. Distributionally robust modeling of demand response and its large-scale potential deduction method. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Wen, Z.C.; Dong, W.J. Model of integrated demand response potential based on portrait of residential users. Renew. Energy Resour. 2020, 38, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Y.; Ai, Q. Demand response estimation method of electricity consumption for residential customer under time of use price. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2023, 43, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Pan, D.B. Research on emergency management capability evaluation method of natural disasters based on set pair analysis. J. Nat. Disasters 2023, 32, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, N.; Cheng, L.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, X. Practical Demand Response Potential Evaluation of Air-Conditioning Loads for Aggregated Customers. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Shao, W.; Ma, Z.; Xu, Z.; Wang, N. Dynamic Optimization of Charging Strategies for EV Parking Lot under Real-Time Pricing. In Proceedings of the 2016 35th Chinese control conference (CCC), Chengdu, China, 27–29 July 2016; pp. 2703–2709. [Google Scholar]

- Karapetyan, A.; Khonji, M.; Chau, S.C.K.; Elbassioni, K.; Zeineldin, H.; El-Fouly, T.H.; Al-Durra, A. A Competitive Scheduling Algorithm for Online Demand Response in Islanded Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 3430–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Ma, J. Data-Driven Resource Planning for Virtual Power Plant Integrating Demand Response Customer Selection and Storage. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 1833–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, T.; Koch, E.; Stluka, P. Automated Demand Response for Smart Buildings and Microgrids: The State of the Practice and Research Challenges. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 726–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Sun, Y.; Qi, B.; Li, B. Incentive-Based Integrated Demand Response Considering S&C Effect in Demand Side with Incomplete Information. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 4465–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Shi, J.; Li, S.; Chen, Z.; Jiao, F.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Z. Data-driven and physical model-based evaluation method for the achievable demand response potential of residential consumers’ air conditioning loads. Appl. Energy 2022, 307, 118017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adika, C.O.; Wang, L. Smart charging and appliance scheduling approaches to demand side management. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2014, 57, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallonetto, F.; De Rosa, M.; Milano, F.; Finn, D.P. Demand response algorithms for smart-grid ready residential buildings using machine learning models. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 1265–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rdusseeun, L.; Kaufman, P. Clustering by means of medoids. In Proceedings of the Statistical Data Analysis Based on the L1 Norm Conference, Neuchatel, Switzerland, 31 August–4 September 1987; Volume 31, p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Nigro, L.; Fränti, P. Two medoid-based algorithms for clustering sets. Algorithms 2023, 16, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Oates, T. Imaging time-series to improve classification and imputation. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 25–31 July 2015; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 3939–3945. [Google Scholar]

- Faustine, A.; Pereira, L. Improved appliance classification in non-intrusive load monitoring using weighted recurrence graph and convolutional neural networks. Energies 2020, 13, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damousis, I.G.; Bakirtzis, A.G.; Dokopoulos, P.S. A solution to the unit-commitment problem using integer-coded genetic algorithm. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2004, 19, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Xiang, W.; Huang, B.; Wang, J.; Fang, J. Optimised extreme gradient boosting model for short term electric load demand forecasting of regional grid system. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Liu, Q.; Gong, L.; Lei, J. Application of a mid-/low-temperature solar thermochemical technology in the distributed energy system with cooling, heating and power production. Appl. Energy 2019, 253, 113491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Lu, N.; Qin, J.; Tang, W.; Yao, L. A deep learning algorithm to estimate hourly global solar radiation from geostationary satellite data. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 114, 109327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z. Ensemble Methods: Foundations and Algorithms; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Liu, D. Power losses prediction based on feature selection and Stacking integrated learning. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2020, 48, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, S. A space prediction method for power outage in a typhoon disaster based on a Stacking integrated structure. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2022, 50, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Data Service. Low Carbon London Project Data. Available online: https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/smartmeter-energy-use-data-in-london-households (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Weather Data services. Weather History for London. Available online: https://www.visualcrossing.com/weather/weather-data-services (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Sauer, T. Numerical Analysis, 3rd ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Target Model | Feature Category | Feature Subcategory | Symbol/ Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE-ResNet-20 | Image feature | / | IRP | Improved Recurrence Plot |

| GADF | Gramian Angular Difference Field | |||

| WMTF | Weighted Markov Transition Field | |||

| SVM RF XGBoost | Indicator feature | Load Shape Feature | P | Average power over the entire day of the typical daily electricity consumption curve (TECC) |

| Ps | Average power over each period of the TECC | |||

| ξp2m | Peak-to-average ratio of the TECC | |||

| ξp2v | Normalized peak-to-valley difference of the TECC | |||

| The upper deviation magnitude from the TECC for each period | ||||

| The lower deviation magnitude from the TECC for each period | ||||

| Load Variability Feature | Variability within daily electricity consumption for each period | |||

| Variability at identical time points across different days for each period | ||||

| Load Correlation Feature | kt | Spearman correlation coefficient between the TECC and temperature | ||

| kh | Spearman correlation coefficient between the TECC of weekdays and holidays |

| Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| General | Image resolution | 48 × 48 |

| IRP | Distance threshold ε | 0.5 |

| Discretization level η | 5 | |

| GADF | - | - |

| WMTF | Number of quantile bins Q | 8 |

| Weight attenuation coefficient γ | 0.05 |

| Feature | Model | IMAE | IRMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TECC | RNN | 0.795 | 1.204 | 0.339 |

| LSTM | 0.823 | 1.106 | 0.341 | |

| TECI | LeNet-5 | 0.781 | 1.225 | 0.298 |

| AlexNet | 0.766 | 1.095 | 0.375 | |

| SE-ResNet-20 | 0.758 | 1.077 | 0.412 | |

| IFDR | MLP | 0.63 | 0.938 | 0.629 |

| SVM | 0.621 | 0.964 | 0.556 | |

| RF | 0.362 | 0.587 | 0.717 | |

| TECI + IFDR (proposed) | Stacking (proposed) | 0.345 | 0.567 | 0.742 |

| Feature | Model | IMAE | IRMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TECC | RNN | 0.887 | 1.225 | 0.308 |

| LSTM | 0.908 | 1.303 | 0.256 | |

| TECI | LeNet-5 | 0.801 | 1.103 | 0.31 |

| AlexNet | 0.779 | 1.098 | 0.366 | |

| SE-ResNet-20 | 0.741 | 1.029 | 0.433 | |

| IFDR | MLP | 0.689 | 0.989 | 0.495 |

| SVM | 0.707 | 0.979 | 0.489 | |

| RF | 0.619 | 0.964 | 0.558 | |

| TECI + IFDR (proposed) | Stacking (proposed) | 0.566 | 0.911 | 0.628 |

| Experimental Group | Description |

|---|---|

| Group 0 | Adopt all the proposed features. |

| Group 1 | Remove load shape features. |

| Group 2 | Remove load variability features. |

| Group 3 | Remove load correlation features. |

| Group 4 | Remove image features. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, C.; Xu, Z.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, J.; Weng, X.; Zhang, H.; Yu, T.; Xiao, W. Demand Response Potential Evaluation Based on Multivariate Heterogeneous Features and Stacking Mechanism. Energies 2026, 19, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010194

Gao C, Xu Z, Cheng R, Zhang J, Weng X, Zhang H, Yu T, Xiao W. Demand Response Potential Evaluation Based on Multivariate Heterogeneous Features and Stacking Mechanism. Energies. 2026; 19(1):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010194

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Chong, Zhiheng Xu, Ran Cheng, Junxiao Zhang, Xinghang Weng, Huahui Zhang, Tao Yu, and Wencong Xiao. 2026. "Demand Response Potential Evaluation Based on Multivariate Heterogeneous Features and Stacking Mechanism" Energies 19, no. 1: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010194

APA StyleGao, C., Xu, Z., Cheng, R., Zhang, J., Weng, X., Zhang, H., Yu, T., & Xiao, W. (2026). Demand Response Potential Evaluation Based on Multivariate Heterogeneous Features and Stacking Mechanism. Energies, 19(1), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010194