Hybrid Nanoparticle Geometry Optimization for Thermal Enhancement in Solar Collectors Using Neural Network Models

Abstract

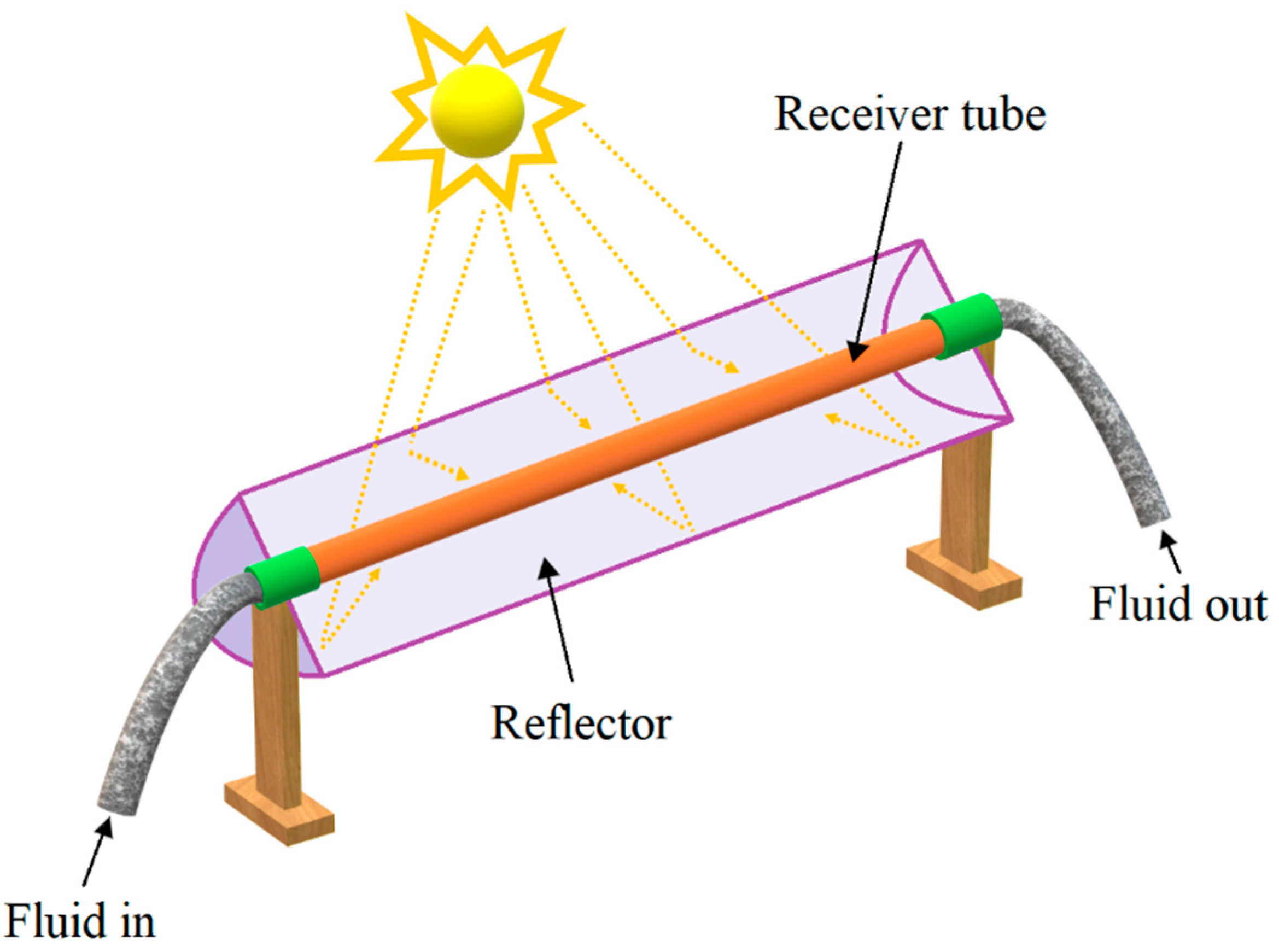

1. Introduction

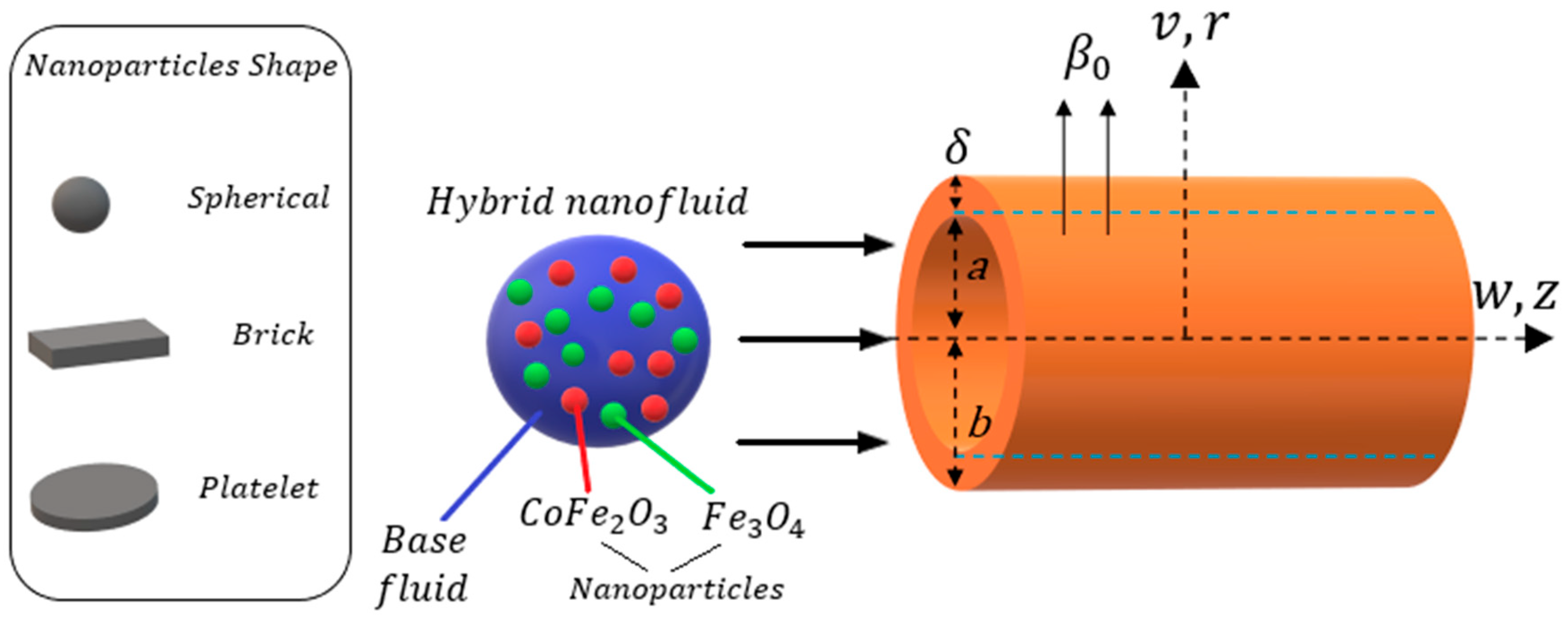

2. Mathematical Analysis

3. Method of Solution

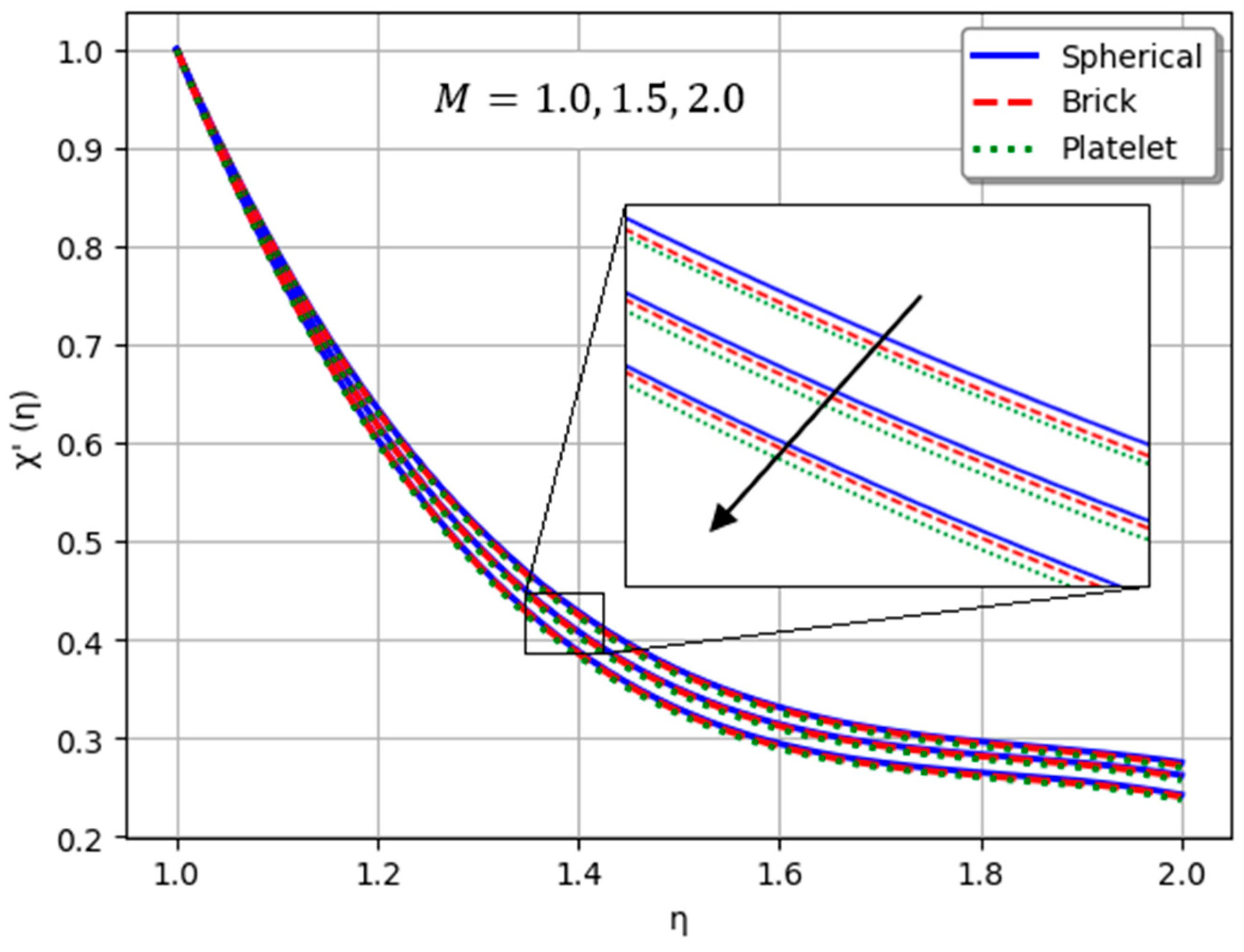

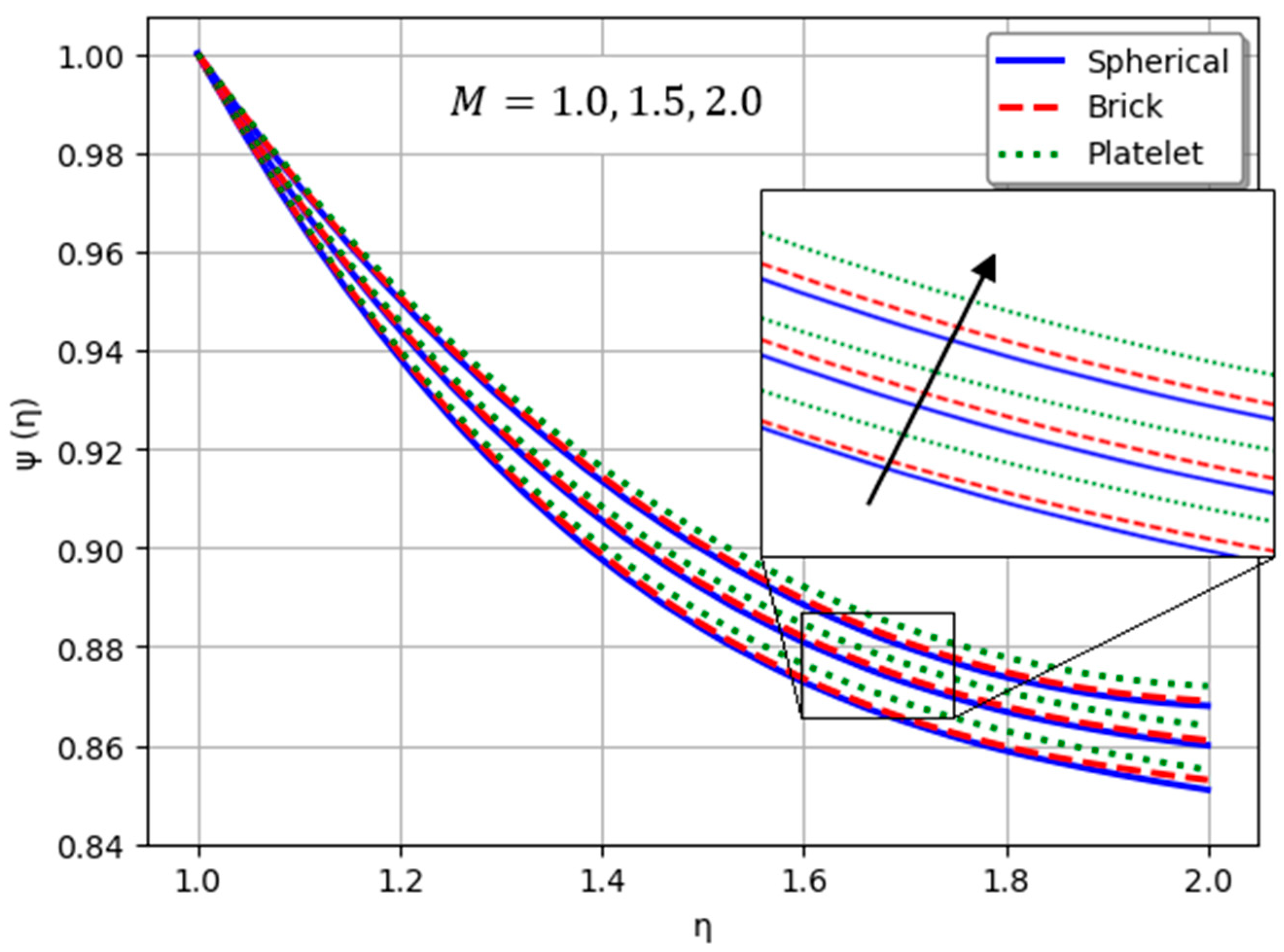

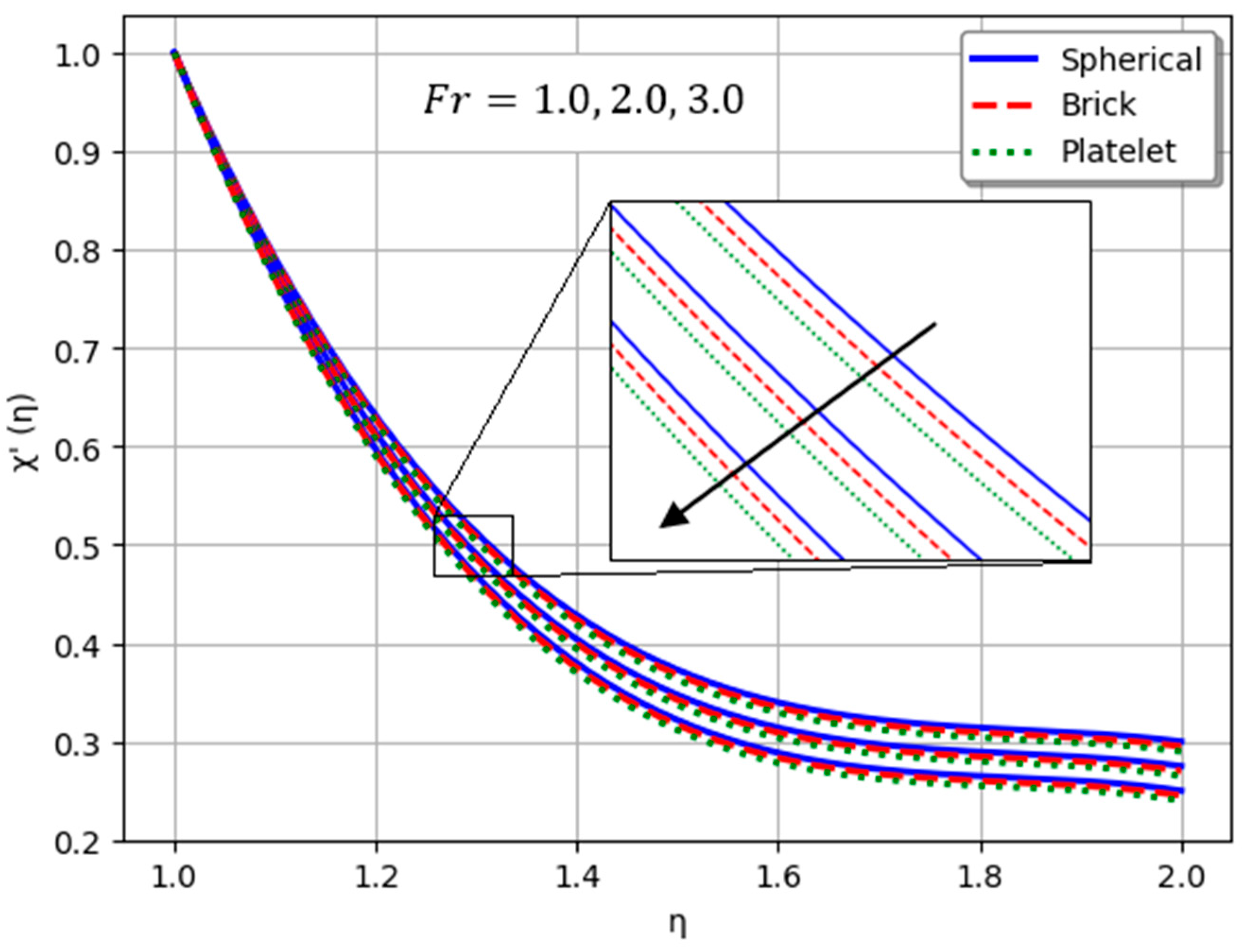

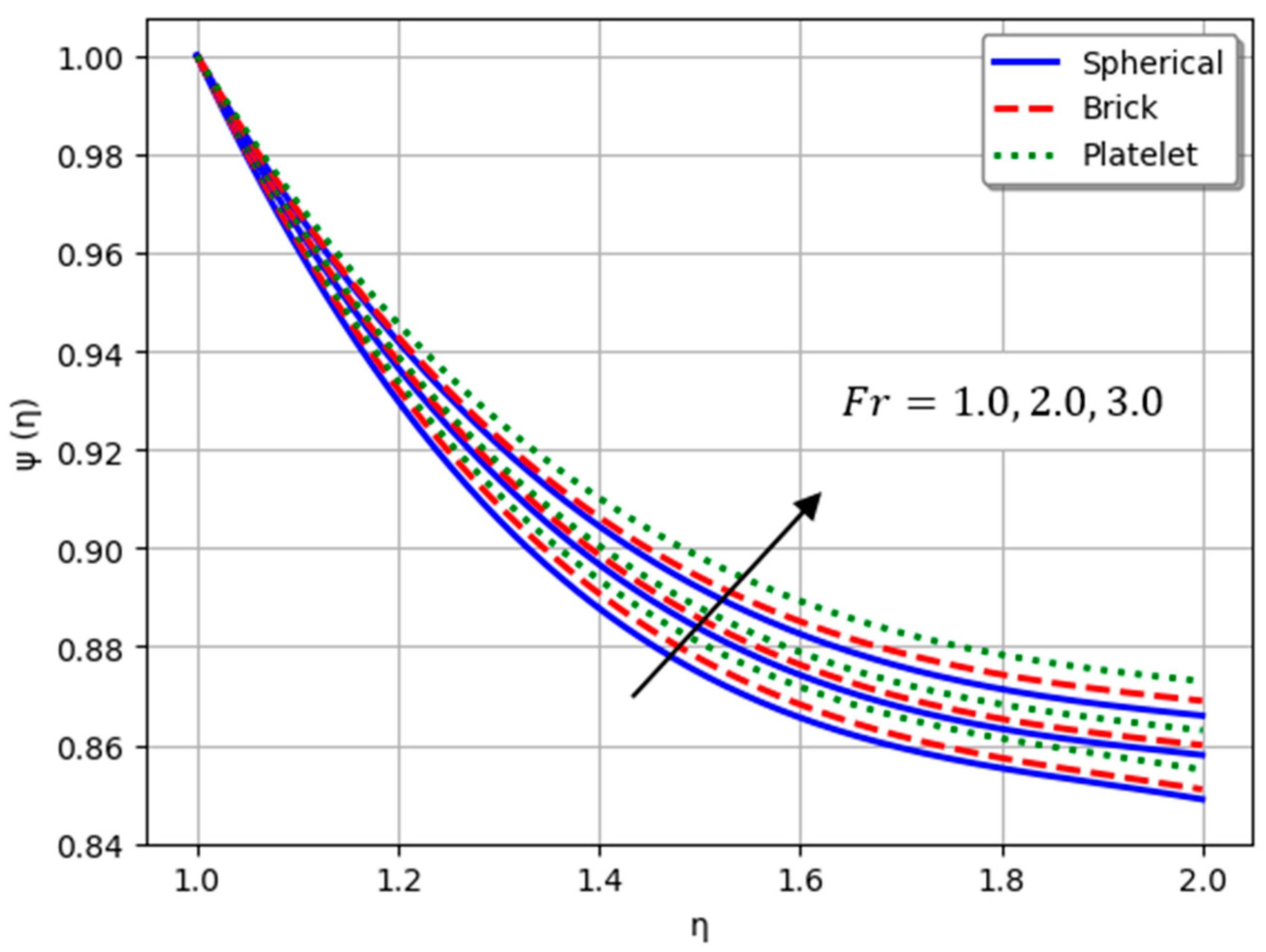

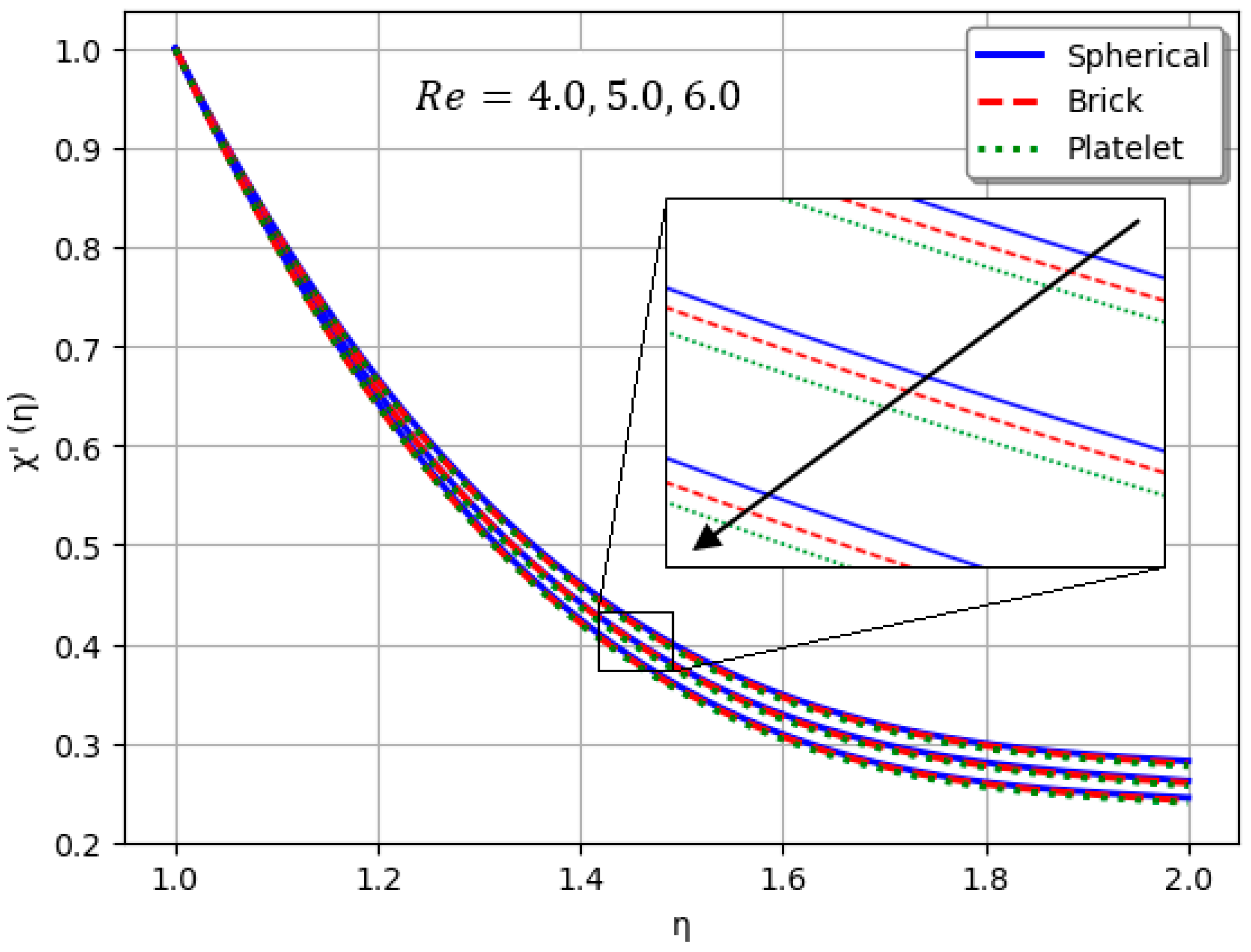

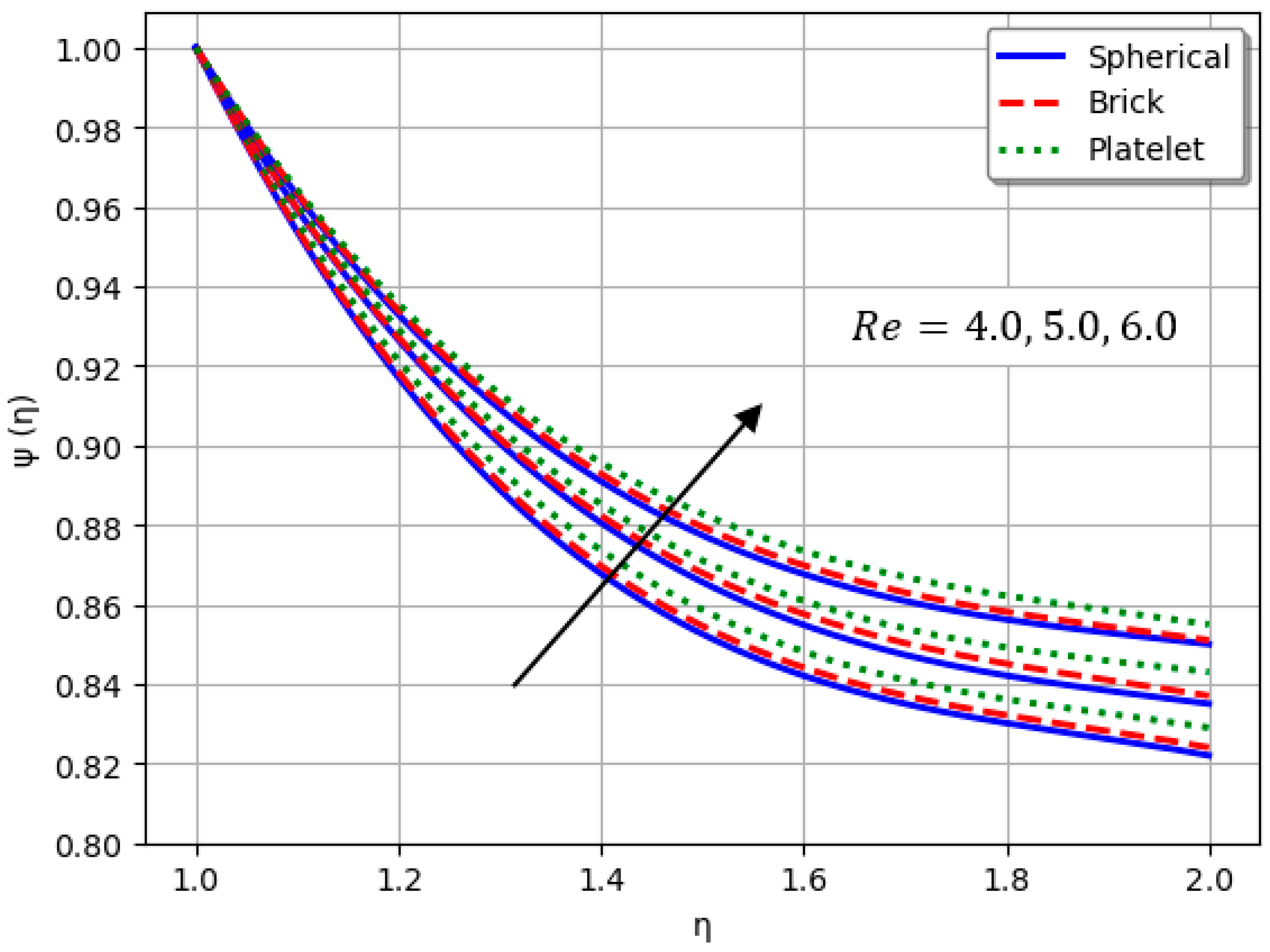

4. Results and Discussions

5. Conclusions

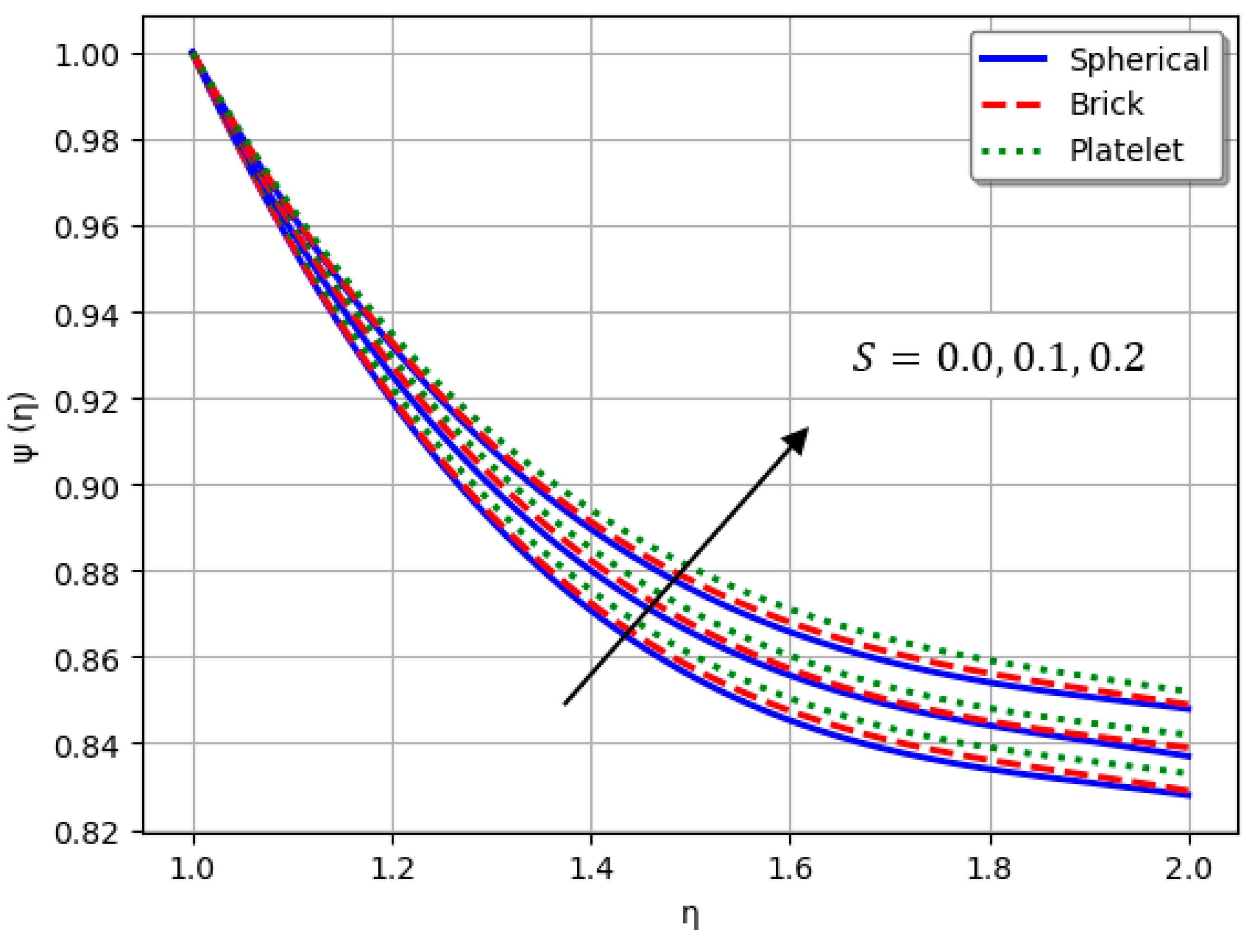

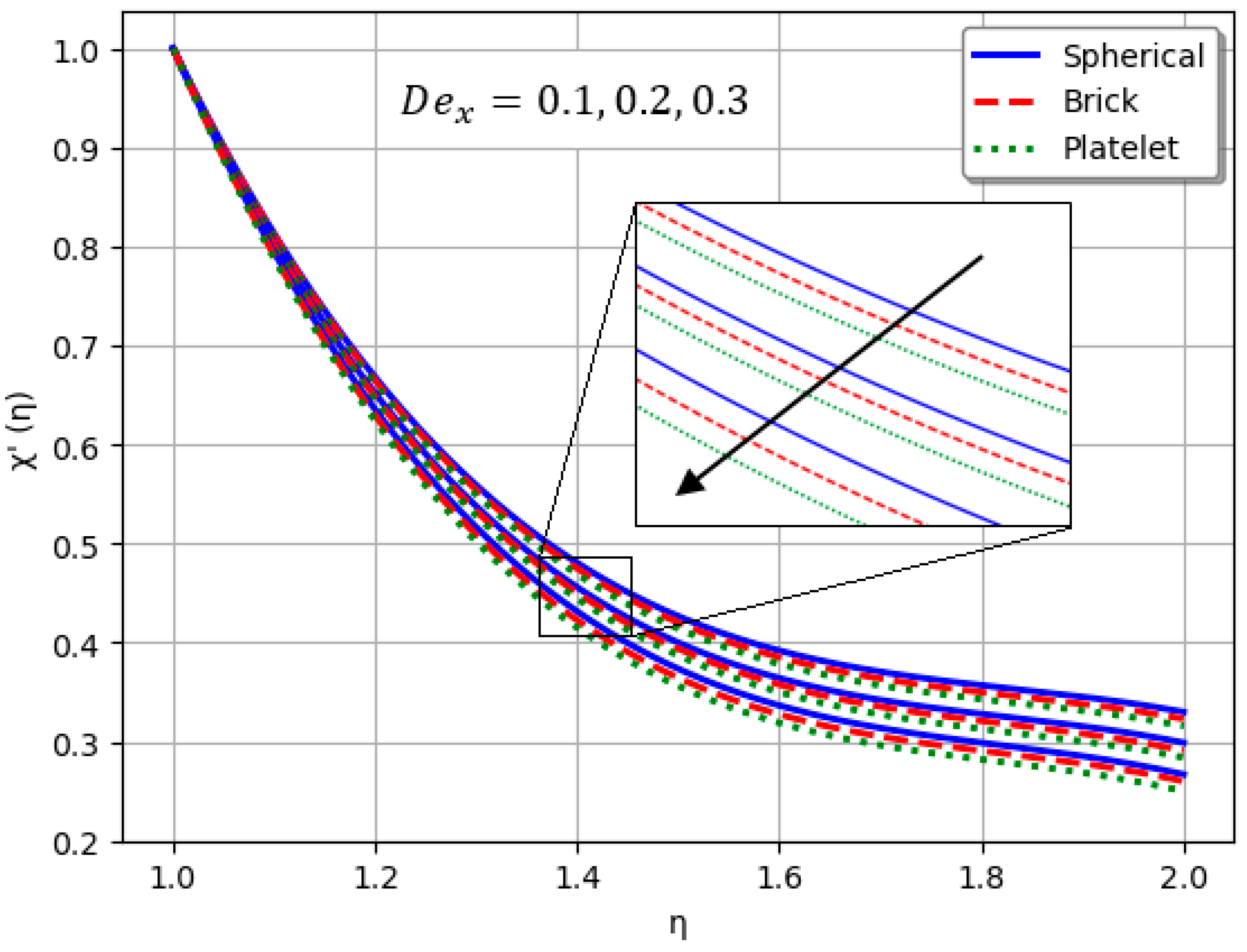

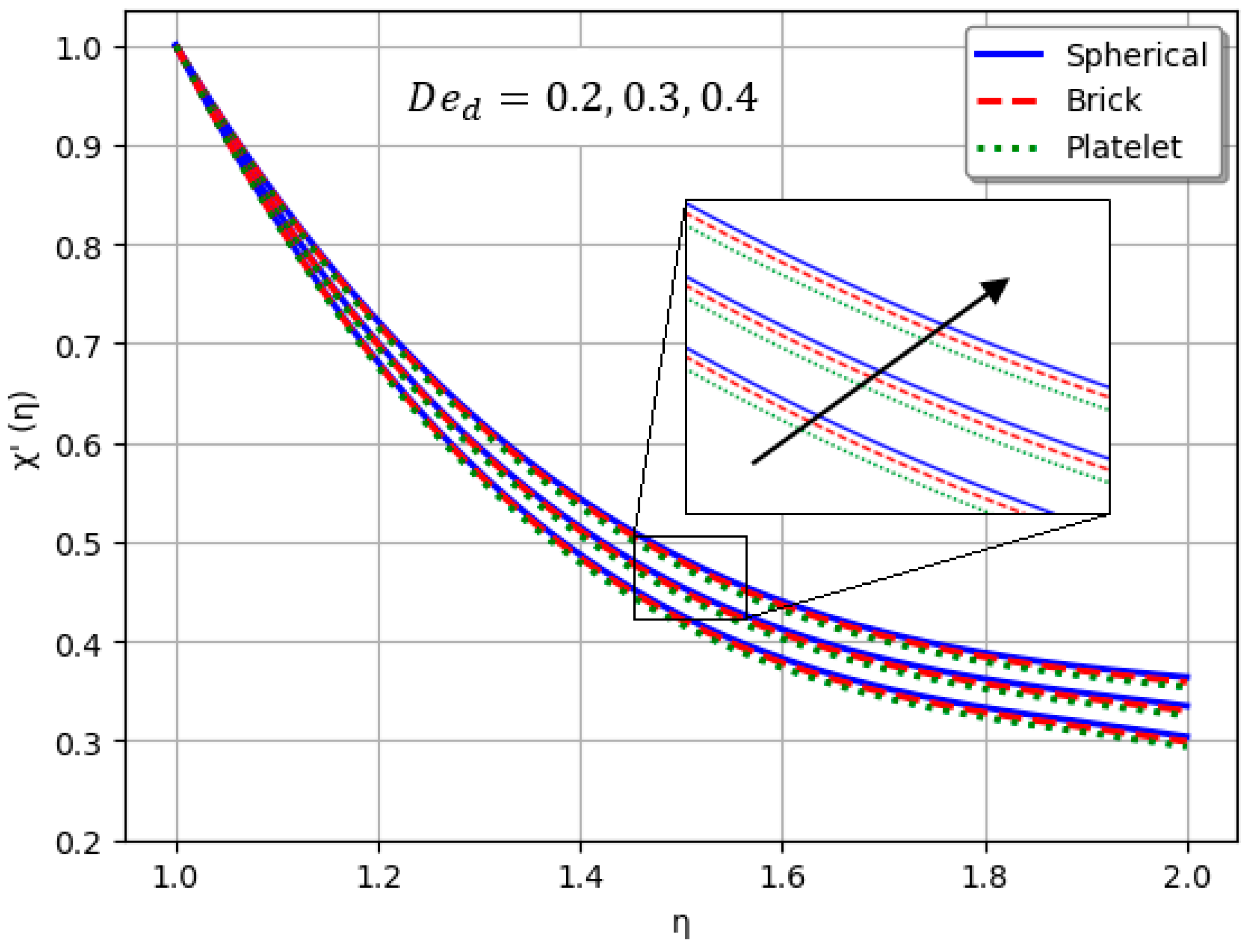

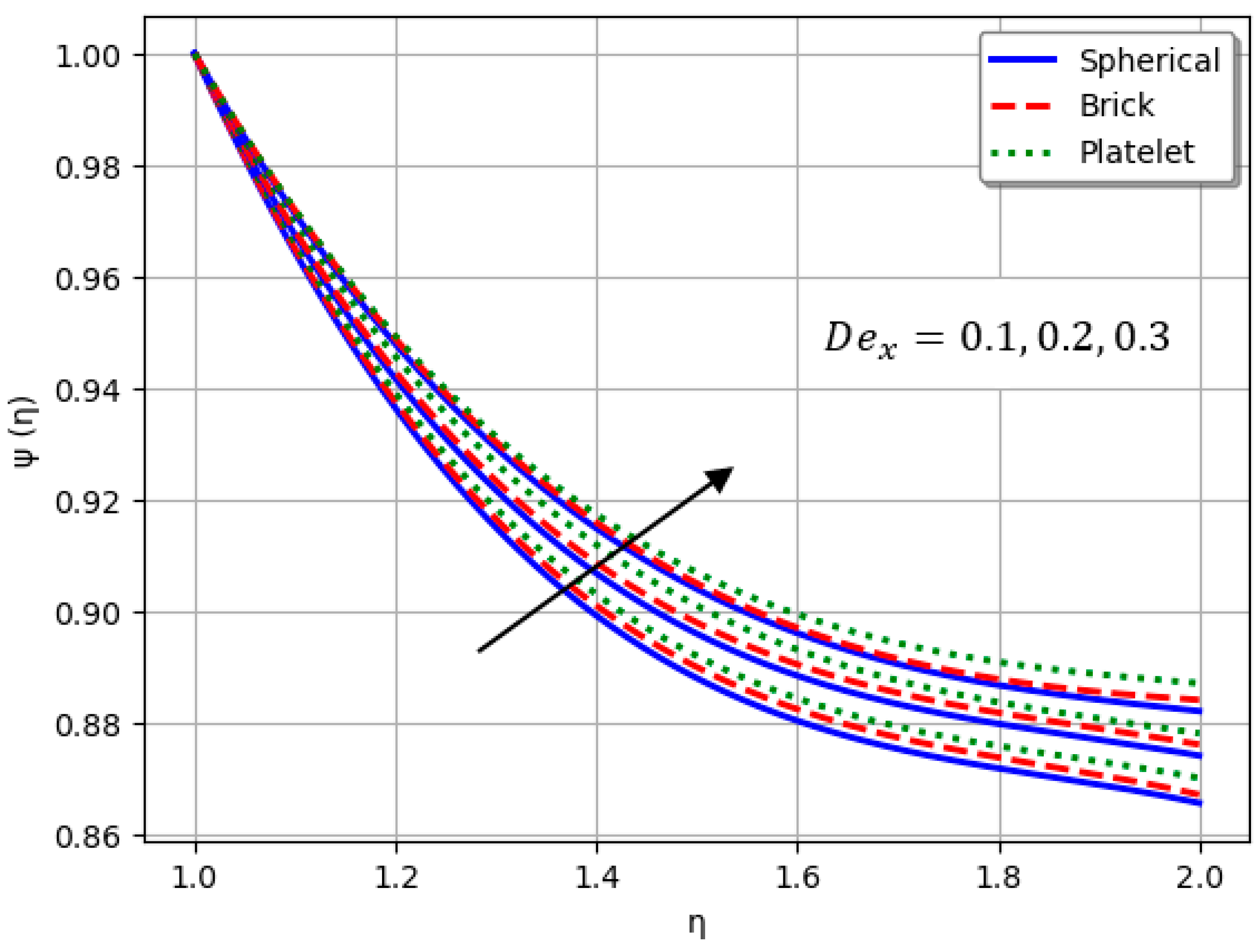

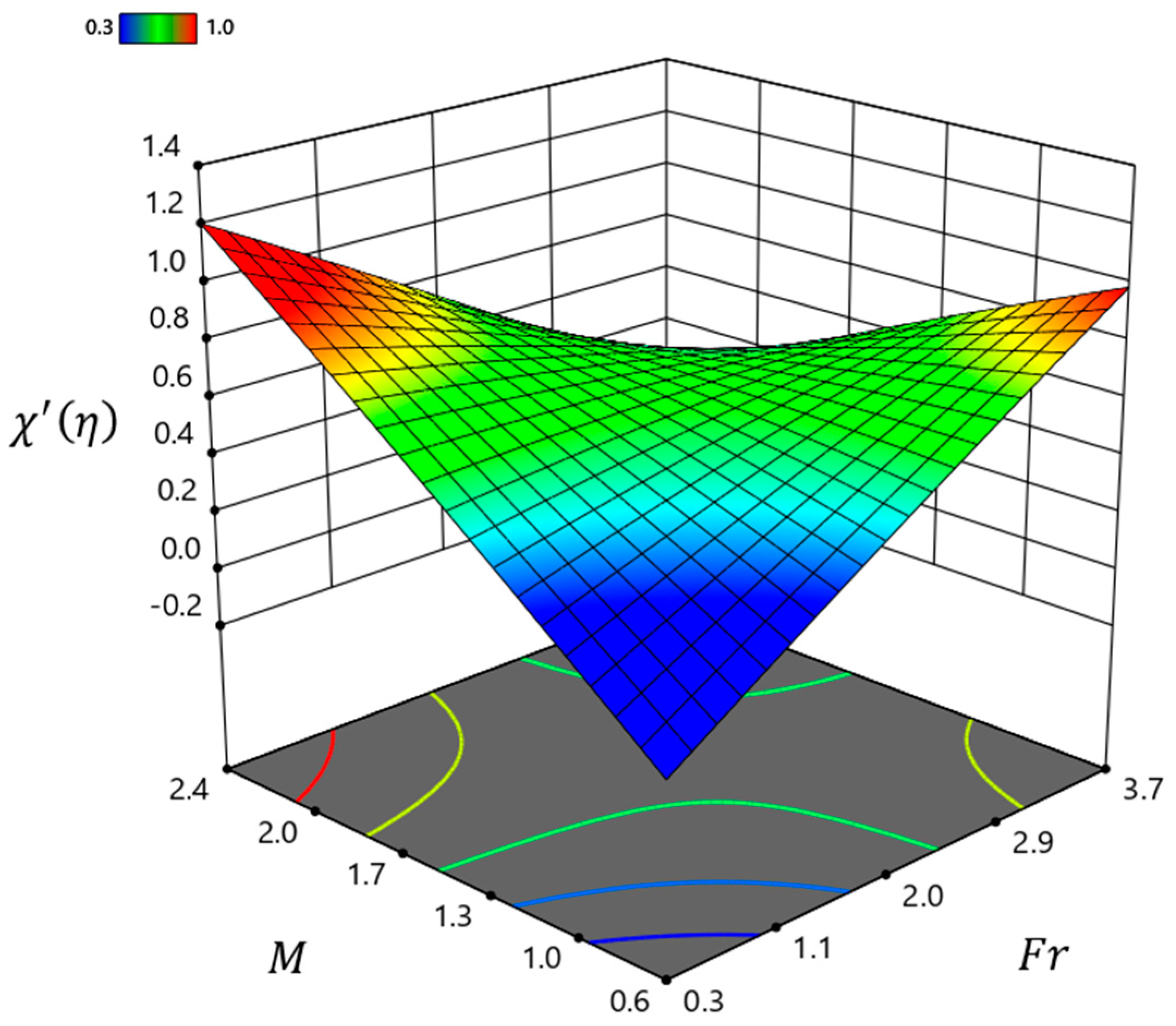

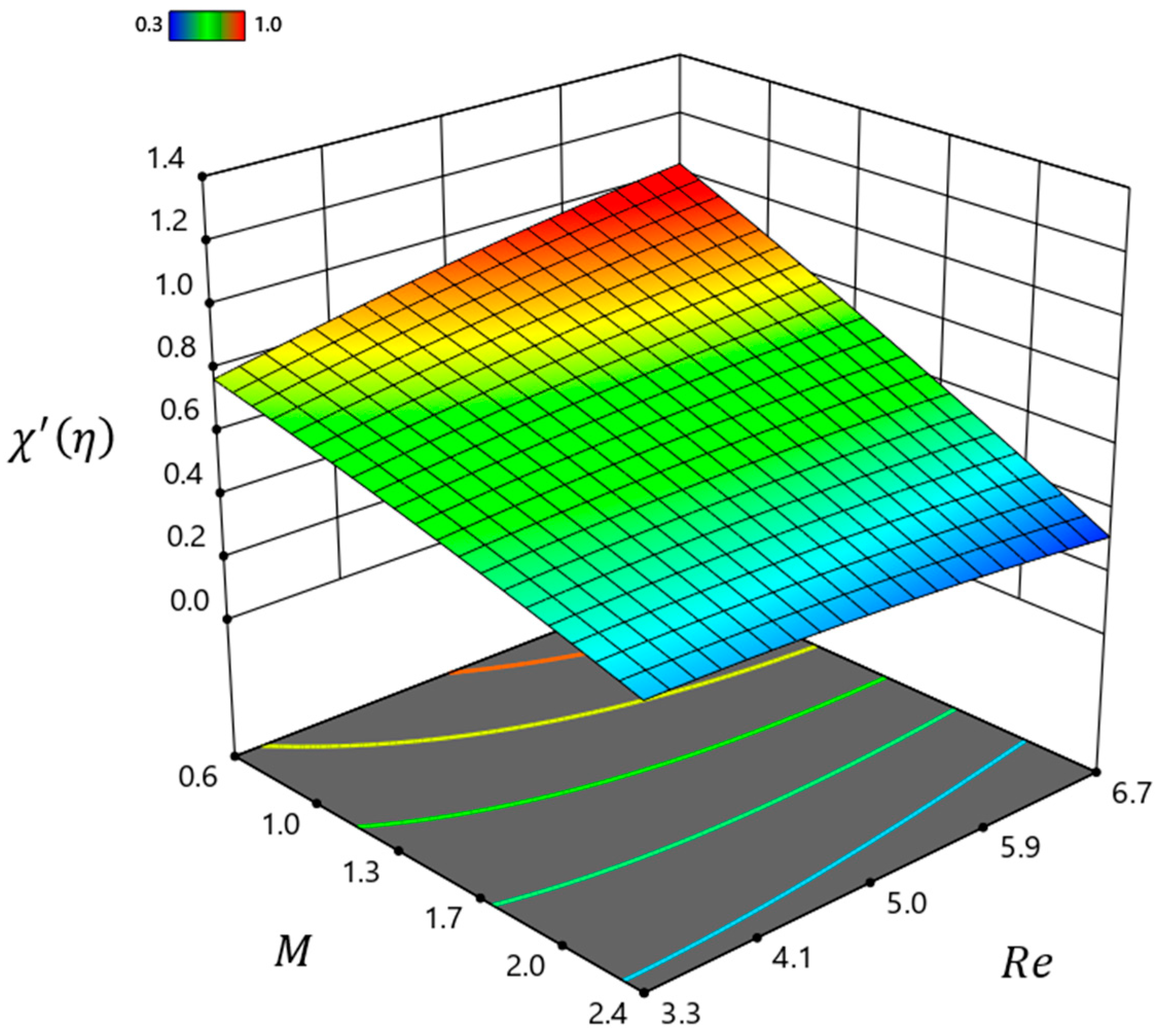

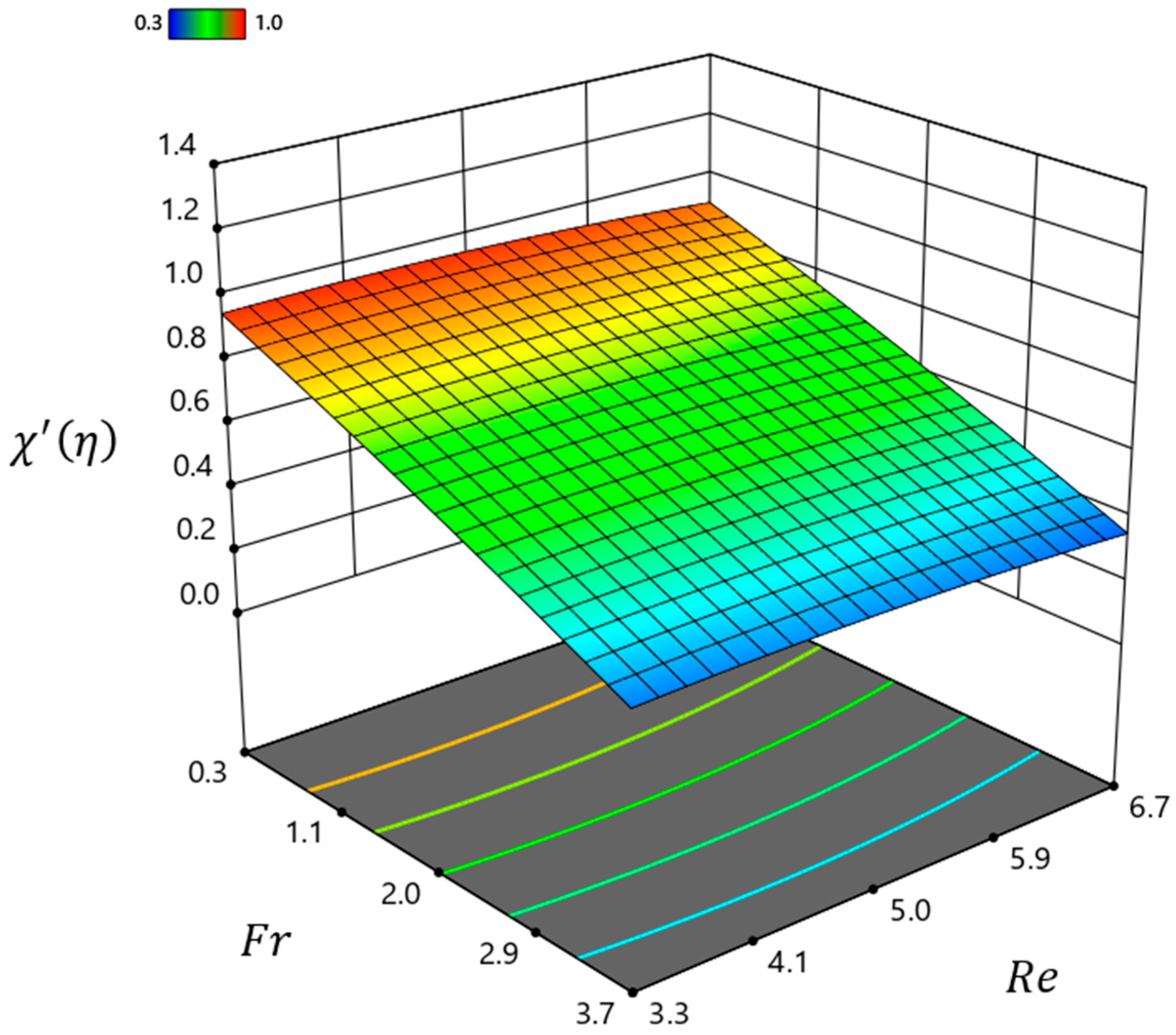

- An increase in intensifies the stress-relaxation effect, leading to a reduction in the velocity profile of the nanofluid.

- The Lorentz force within the system reduced the velocity profile of the fluid while enhancing thermal transport.

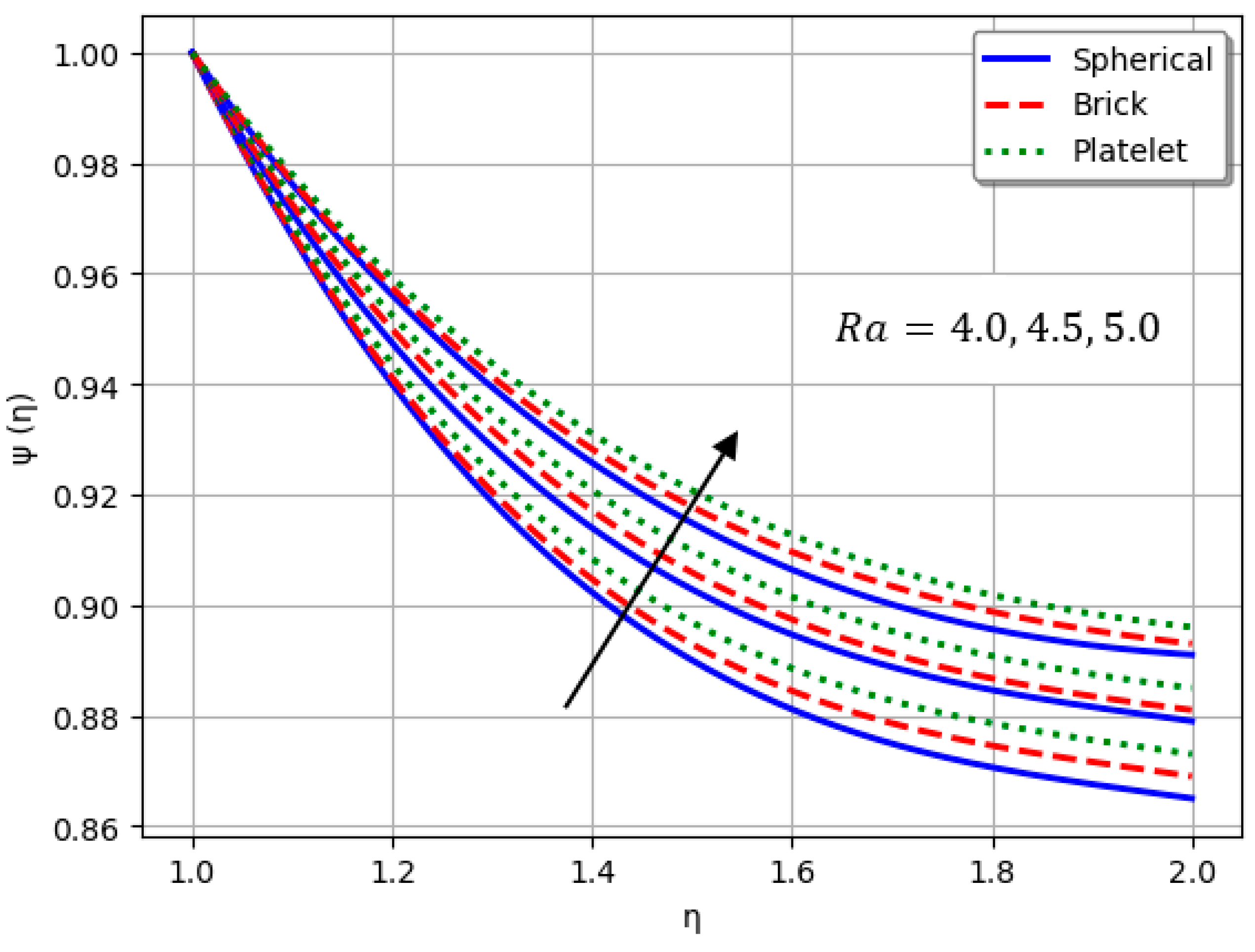

- Nanofluids containing spherical nanoparticles exhibit greater heat transfer performance than those with brick-like or platelet geometries.

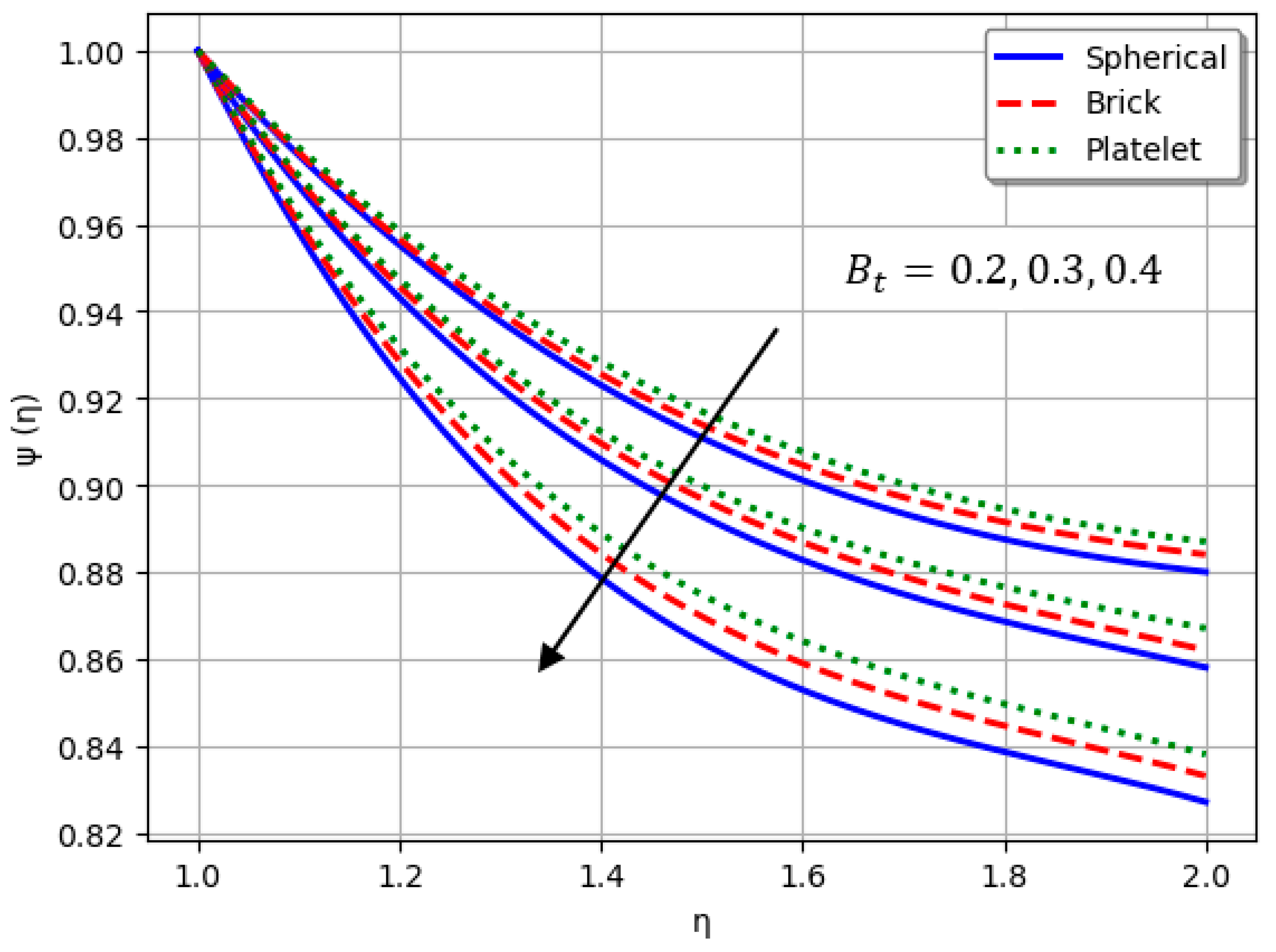

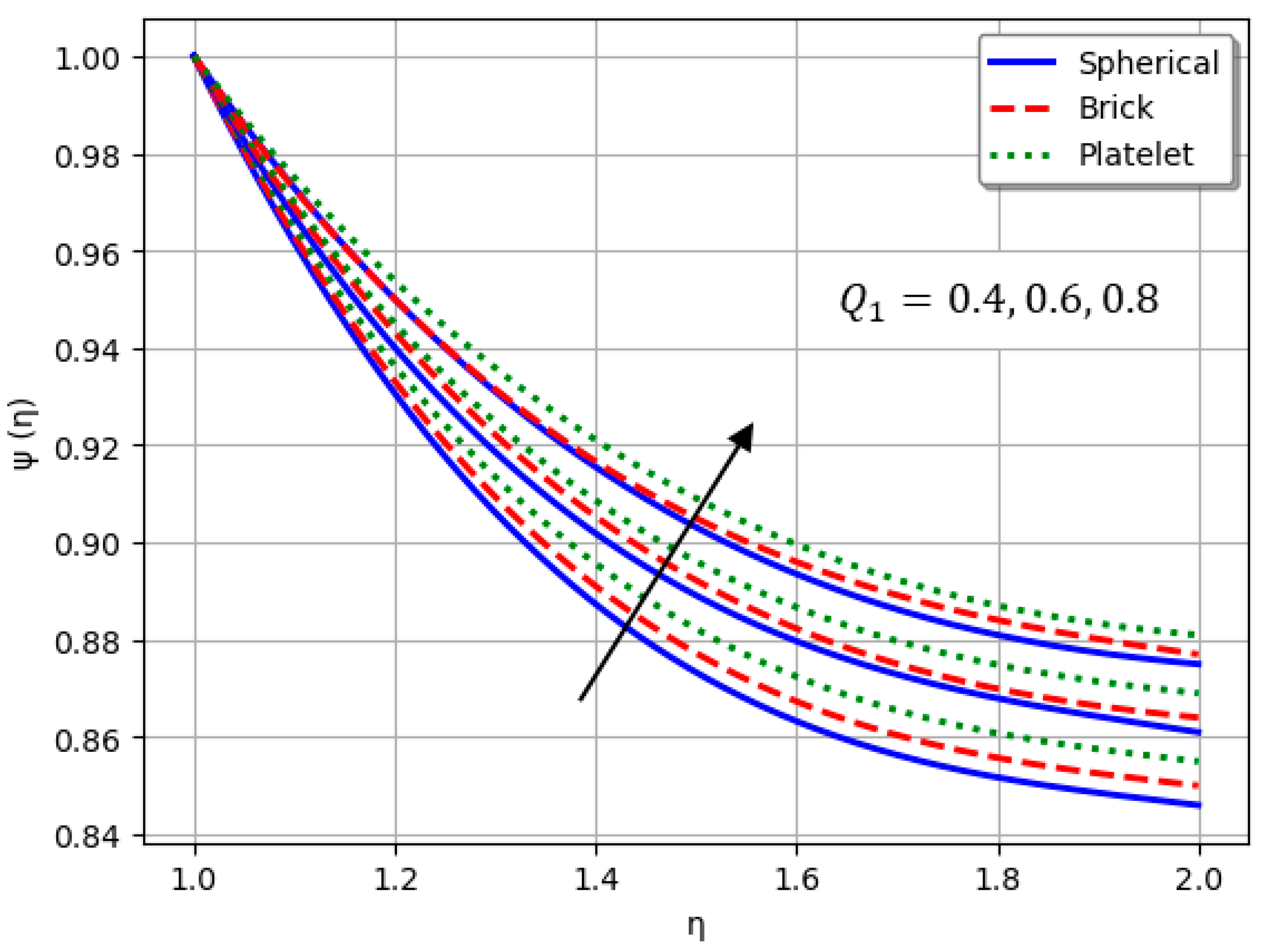

- For and greater than zero, the thermal performance of the hybrid nanofluid improves markedly, especially when using platelet-form nanoparticles.

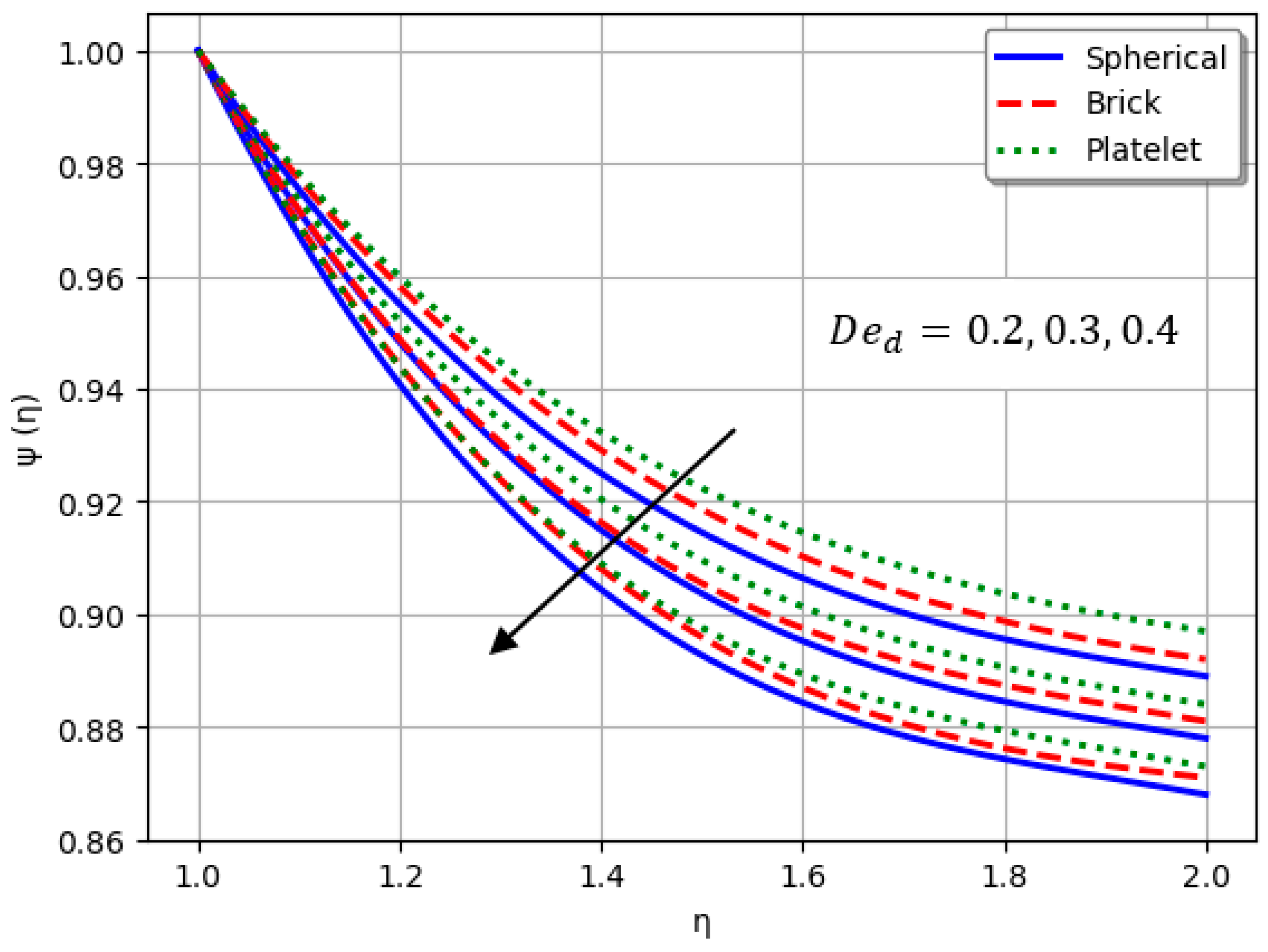

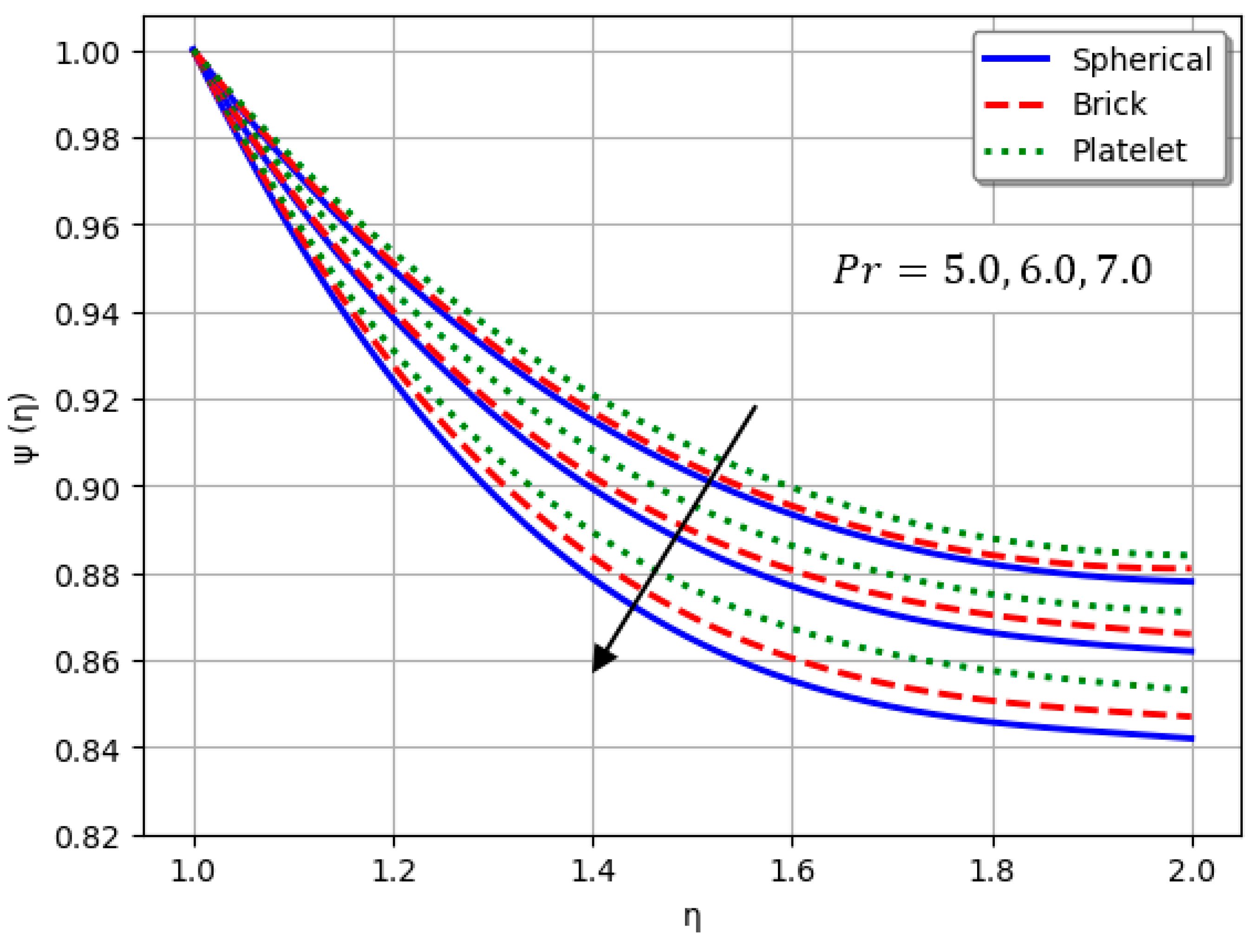

- An increase in led to a decline in heat transport efficiency.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Nomenclature | |

| The parameter of shape | |

| Heat dissipation relaxation factor | |

| Time-based factors define the Deborah values | |

| Instability rate factor | |

| Characteristic of radiation | |

| Scaled profiles of flow velocity and thermal state | |

| Thermal condition at boundary point (b) | |

| Prandtl number | |

| The factor of inertia | |

| Thermal generation or absorption factor | |

| Relaxation of heat dissipation | |

| Magnitude of the flux region | |

| Velocity parameters | |

| The hybrid nanofluid’s density | |

| Heat capacity of hybrid nanofluid | |

| Heat conductivity of hybrid nanofluid | |

| The hybrid nanofluid’s viscosity | |

| Electrical conduction of hybrid nanofluid | |

| Concentration level of nanoparticles | |

| Regional inertia factor | |

| Reynolds number | |

| Similarity factor | |

| Magnetic factor | |

| Reference thermal level | |

| Fluid’s temperature | |

| The factor of drag | |

| Permeability factor | |

| Dissipation and lag periods | |

| The depth of the coating layer | |

| Variable of the heating source | |

| Radial and axial coordinates | |

| The base fluid | |

| Hybrid nanofluid | |

| The nano solid nanoparticles | |

| wall |

References

- Choi, S.; Jeffrey, A. Eastman. Enhancing Thermal Conductivity of Fluids with Nanoparticles; No. ANL/MSD/CP-84938; CONF-951135-29; Argonne National Lab. (ANL): Argonne, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, P.M.; Jalili, P.; Ganji, D.D.; Jalili, B. Computational study of steady micropolar hybrid nanofluid flow between permeable walls: Impact of Reynolds and Peclet numbers using advanced numerical methods. Int. J. Thermofluids 2025, 30, 101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarsana Reddy, P.; Jyothi, K.; Suryanarayana Reddy, M. Flow and heat transfer analysis of carbon nanotubes-based Maxwell nanofluid flow driven by rotating stretchable disks with thermal radiation. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2018, 40, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedevi, P.; Sudarsana Reddy, P. Impact of convective boundary condition on heat and mass transfer of nanofluid flow over a thin needle filled with carbon nanotubes. J. Nanofluids 2020, 9, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevankumar; Sandeep, N. Effect of magnetic induction on EG-water-based composite nanofluid flow across an elongated region: A KB approach. Waves Random Complex Media 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar; Khan, T.S.; Sene, N.; Mouldi, A.; Brahmia, A. Heat and Mass Transfer of the Darcy-Forchheimer Casson Hybrid Nanofluid Flow due to an Extending Curved Surface. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 3979168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, W.; Magdy, M.M. Heat and mass transfer analysis of nanofluid flow based on Cu, Al2O3, and TiO2 over a moving rotating plate and impact of various nanoparticle shapes. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 9606382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, U.; Liang, H.; Ahmad, H.; Abbas, M.; Iqbal, A.; Hamed, Y.S. Study of (Ag and TiO2)/water nanoparticles shape effect on heat transfer and hybrid nanofluid flow toward stretching shrinking horizontal cylinder. Results Phys. 2021, 21, 103812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Yasmin, S.; Waqas, H.; Khan, S.A.; Muhammad, T.; Alshammari, N.; Hamadneh, N.N.; Khan, I. Computational analysis of nanoparticle shapes on hybrid nanofluid flow due to flat horizontal plate via solar collector. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasir, M.; Ahmed, A.; Khan, M.; Alzahrani, A.K.; Malik, Z.U.; Alshehri, A.M. Mathematical modelling of unsteady Oldroyd-B fluid flow due to stretchable cylindrical surface with energy transport. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, A.; Shah, Z. Computational analysis of viscous dissipation and Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium on radioactive hybrid nanofluid. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 30, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, M.; Hameed, M.K.; Nisar, K.S.; Majeed, A.H. Darcy-Forchheimer flow of maxwell nanofluid flow over a porous stretching sheet with Arrhenius activation energy and nield boundary conditions. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 44, 102830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharil, H.A.; Yang, H. Comprehensive thermoparametric analysis of supercritical carbon dioxide in parabolic trough solar collector via an innovative method. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 264, 125434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Chen, W.; Zhang, T.; Ma, L.; Xue, X.; Zhang, X. Thermal analysis and parameter optimization of advanced adiabatic compressed air energy storage with parabolic trough solar collector auxiliary reheating. J. Energy Storage 2025, 110, 115104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huminic, G.; Huminic, A.; Fleacă, C.; Dumitrache, F. Hybrid nanofluids-based direct absorption solar collector: An experimental approach. Int. J. Thermophys. 2025, 46, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazzi, Y.; Ali, A.B.; Alashaari, G.A.A.; Alsheherye, S.; Eladeb, A.; Al Mdallal, Q.; Kolsi, L. Enhanced heat transfer in large-aperture PTSCs with semi-circular absorbers using multi-dipole magnetic field: A numerical study. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 71, 106240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Hua, C.; Lin, Y.; Park, T.S. Numerical investigation of heat transfer enhancement in a rectangular solar collector using TiO2-Cu/water hybrid nanofluid and perforated baffle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 279, 127618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzar, A.; Aghaei, A.; Mohsenimonfared, H.; Joshaghani, A.H. Numerical simulation of a parabolic through solar collector with a novel geometric design equipped with an elliptical absorber tube under the influence of magnetic field. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 8865–8885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donga, R.K.; Ashish Karn, A. Improving the thermal performance of parabolic trough solar collectors by incorporating cylindrical attachments within the absorber tube. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 273, 126587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panja, S.K.; Das, B.; Mahesh, V. Performance evaluation of a novel parabolic trough solar collector with nanofluids and porous inserts. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 258, 124495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalsamy, V.; Shantharaman, P.P.; Karunakaran, R. Exploring performance variations of mono-nanofluid-based parabolic trough solar collectors at various concentrations and mass flow rates: An experimental analysis. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 4261–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.V.; Kanna, P.R.; Balasubramanian, D.; Kale, U.; Kilikevičius, A. Numerical investigation of thermal performances of hybrid nanofluids in solar collectors implementing polygonal rough surfaces. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ru, J.; Wu, D.; Ru, Y.; Alkhalifah, T.; Marzouki, R. Exergy destruction and heat transfer of parabolic trough collector using porous medium: Machine learning algorithms. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 276, 126922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahman, N.; Abbas, Z.; Arslan, M.S.; Rafiq, M.Y. Exploring entropy production in radiative cilia flow of Williamson fluid through a curved channel with viscous dissipation effects. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2025, 18, 101566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, B.; Bahmani, M.; Jalili, P.; Liu, D.; Alderremy, A.A.; Ganji, D.D.; Vivas-Cortez, M. Investigating the influence of square size vanes on heat transfer in porous media: An in-depth Nusselt distribution. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2025, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh, S.; Jalili, P.; Jalili, B.; Ganji, D.D. The new analytical and numerical analysis of 2D stretching plates in the presence of a magnetic field and dependent viscosity. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2024, 16, 16878132231220361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh, S.; Jalili, P.; Jalili, B.; Alam, M.M.; Ali, M.R.; Hendy, A.S.; Ganji, D.D. Innovative binary nanofluid approach with copper (Cu-EO) and Magnetite (Fe3O4-EO) for enhanced thermal performance. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 63, 105191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh, S.; Jalili, P.; Jalili, B.; Ahmad, I.; Shabaan, A.A.; El-Wahed Khalifa, H.A. A novel approach to investigate the effect of hybrid nanofluids in a non-Newtonian Maxwell model on thermal management for medical engineering applications. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2025, 39, 2550140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh, S.; Jalili, B.; Jalili, P.; Ganji, D.D.; Ahmad, H. Influence of flow parameters in incompressible electrically conducting fluid over a stretching plate with a surface condition factor. ZAMM—J. Appl. Math. Mech./Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 2025, 105, e70075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afaynou, I.; Faraji, H.; Choukairy, K.; Djebali, R.; Rezk, H. Comprehensive Analysis and Thermo-Economic Optimization of a Hybrid Phase Change Material-Based Heat Sink for Electronics Cooling. Heat Transf. 2025, 54, 3754–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zuo, Z.; Wang, W.; Jia, B.; Liu, R.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, M. Performance comparison and optimization of thermoelectric generator systems with/without stepped-configuration. Energy 2025, 335, 137924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zuo, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.; Yin, Q.; Liu, R.; Jia, B. Transient modeling and analysis of a stepped-configuration thermoelectric generator considering non-uniform temperature distribution. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Niu, A.; Waktole, D.A.; Jia, B.; Zuo, Z.; Wang, W. A self-powered wireless temperature sensing system using flexible thermoelectric generators under simulated thermal condition. Measurement 2025, 253, 117637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; He, X.; Jia, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Tian, Z. Design of a cylindrical thermal rotary concentrator based on transformation thermodynamics. Materials 2025, 18, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Sha, A.; Lu, Q.; Jiang, W.; Cao, Y.; Hu, K.; Li, C.; Du, P. Solar-to-heat conversion control of pavement through thermochromic coating: Integration of thermal management and visual temperature indication. Energy 2025, 333, 137383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Meng, X.; Li, X.; Liang, B. Influence weights of key parameters and optimization strategies for non-contact thermoelectric generator performance enhancement. Energy 2025, 339, 139120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandeep, N. Computational analysis to examine the role of nanoparticle shape on operative usage of solar energy. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 56, 937–948. [Google Scholar]

| Material | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethylene Glycol () | 1115 | 2430 | 0.253 | 10.7 |

| Cobalt Ferrite () | 4907 | 700 | 3.7 | 1.1 |

| Magnetite () | 5180 | 670 | 9.7 | 0.74 |

| Shape of Nanoparticles | Spherical | Brick | Platelet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shape factor () | 3.0 | 3.7 | 5.7 |

| 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 5.5 | 0.383868 | 0.023061 |

| 5.5 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.870944 | 0.480681 |

| 5.5 | 5.0 | 20.0 | 10.0 | 0.409124 | 0.299285 |

| 10.0 | 0.1 | 10.5 | 1.0 | 0.785210 | 0.263309 |

| 10.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.5 | 1.107229 | 0.275808 |

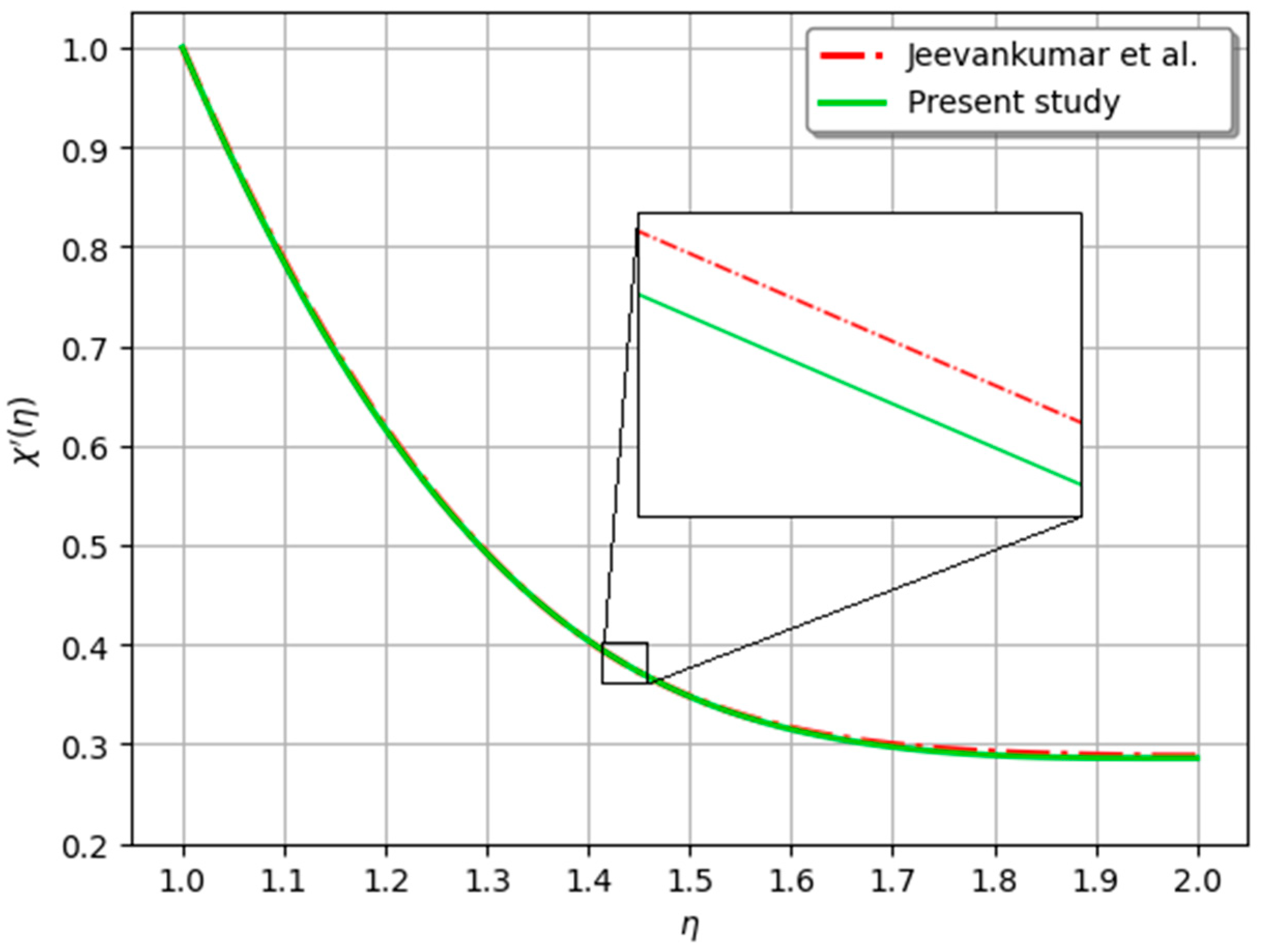

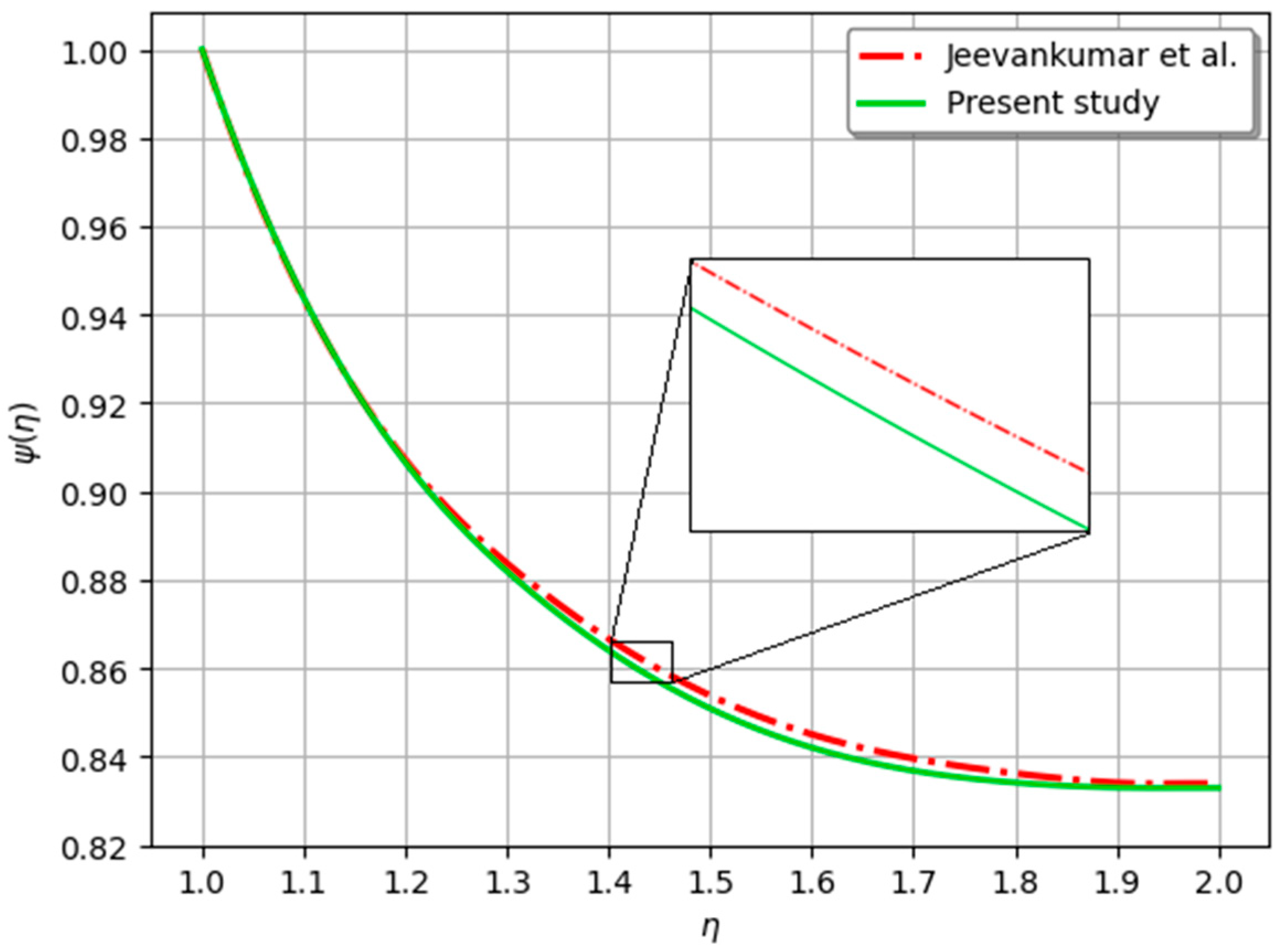

| Jeevankumar et al. [37] | 1.0000 | 0.6142 | 0.3980 | 0.3189 | 0.2894 | 0.2869 |

| Present study | 1.0000 | 0.6140 | 0.3971 | 0.3182 | 0.2892 | 0.2865 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hajizadeh, S.; Jalili, P.; Jalili, B. Hybrid Nanoparticle Geometry Optimization for Thermal Enhancement in Solar Collectors Using Neural Network Models. Energies 2026, 19, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010018

Hajizadeh S, Jalili P, Jalili B. Hybrid Nanoparticle Geometry Optimization for Thermal Enhancement in Solar Collectors Using Neural Network Models. Energies. 2026; 19(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleHajizadeh, Shahryar, Payam Jalili, and Bahram Jalili. 2026. "Hybrid Nanoparticle Geometry Optimization for Thermal Enhancement in Solar Collectors Using Neural Network Models" Energies 19, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010018

APA StyleHajizadeh, S., Jalili, P., & Jalili, B. (2026). Hybrid Nanoparticle Geometry Optimization for Thermal Enhancement in Solar Collectors Using Neural Network Models. Energies, 19(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010018