1. Introduction

The distribution network, as the final stage directly connecting to end-users, plays a critical role in ensuring social welfare and economic stability. The global energy landscape is undergoing a profound transformation driven by industrial expansion and the transition from non-renewable to renewable energy sources [

1]. Consequently, distribution networks are increasingly integrating distributed energy resources (DERs), variable loads, and energy storage systems. While this integration enhances supply reliability and mitigates energy shortages, the operation process of distribution systems introduces greater complexity and operational uncertainty [

2]. Moreover, ongoing electricity market reforms and economic dispatch mechanisms further complicate grid management, making distribution systems more susceptible to unexpected operating conditions [

3].

Distribution System State Estimation (DSSE) provides real-time estimates of system states like node voltages, supporting analysis, control, topology, bad data detection, and device planning for the Distribution Management System (DMS). However, conventional DSSE faces three main challenges: (1) Low observability due to limited deployment of high-precision devices like PMUs; (2) data uncertainty caused by noisy measurements and outdated line parameters; and (3) topological uncertainty due to frequent changes in distribution networks from faults, maintenance, or reconfiguration. These issues hinder traditional estimation methods, making accurate DSSE vital for better grid management, stability, and resilience [

4,

5,

6].

Recent research on distribution network state estimation algorithms primarily concentrates on the Weighted Least Squares (WLS) approach, robust algorithms, and new artificial intelligence techniques. These are typically classified into physics-model-based methods and data-driven approaches that use historical data.

Distribution network state estimation uses static and dynamic methods based on physics models. Static estimation employs current measurement data, with the Weighted Least Squares (WLS) method being the most common, refined over time [

7]. Enhancements to WLS include incorporating measurement correlations [

8], spatiotemporal features [

9], and augmented analysis to improve accuracy [

10]. Some methods reduce measurement data using intermediate variables [

11,

12] or split the network into areas [

13,

14], simplifying calculations at the risk of noise sensitivity and iteration demands [

15,

16]. With DERs, system dynamics can cause WLS methods to fail locally [

17]. To address data issues, alternatives like WLAV and Huber estimators [

18] are used, though they involve complex, slower models, impacting real-time performance.

Dynamic state estimation uses current measurement data and the previous state estimate to infer and predict the next state. While mainly based on Kalman Filtering (KF) for linear systems, solutions for nonlinear systems include algorithms like the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF), Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF), Cubature Kalman Filter, and Particle Filter. Reference [

19] introduced an adaptive interpolation technique to mitigate nonlinear effects on EKF performance by quantifying the nonlinearity of measurement and state equations. To enhance robustness, reference [

20] proposed an improved UKF that adjusts the distribution of Sigma points in real-time via a correction factor, thus increasing estimation accuracy. Reference [

21] applied the H∞ criterion from robust control to manage measurement noise uncertainty, developing an H∞-UKF method. Reference [

22] addressed false data injection attacks with a hybrid KF-based model, enhancing security across various scenarios. Overall, physics-model-based solutions depend on line parameters and measurement data; however, their iterative process is time-consuming, limiting applications amid high uncertainty in distribution network operations.

With the increasing adoption of various machine learning algorithms, applying artificial intelligence techniques to solve complex power system issues, including state estimation, has garnered growing research interest. Data-driven AI methods analyze the nonlinear relationships between measurement vectors and state variables using historical data to develop models tailored to the data. These methods significantly improve the accuracy and robustness of state estimation, making them a popular research area. This field includes directly modeling the relationship between input measurements and output state variables with data-driven models and using these models to support physics-based solutions. For example, Ref. [

18] used historical data and associated states to learn the mapping from current measurements to state variables. By inputting current measurement data into the trained model, an estimate of the current state is obtained. Similarly, Refs. [

23,

24] combined distributed local measurements with polynomial regression to estimate system voltage magnitude and phase angle, requiring a measurable controller in the distributed energy resource system as input. Reference [

25] proposed a fast state estimation method suitable for large systems, where neural networks output node voltage magnitudes and phase angles, with measurements such as branch power, which have strong correlations, serving as inputs selected through correlation analysis. After offline training, the model can generate voltage estimates from measurement data in online operation, although the varying inputs for each node increase the complexity of training. In [

26], a deep ensemble approach was introduced to enhance training stability by combining models with linear regression to reduce uncertainty. Meanwhile, Refs. [

27,

28] employed neural networks to explore the relationship between measurements and state variables, providing initial estimates for Gauss–Newton methods. Given the vast data in distribution network databases, extracting valuable insights and utilizing data-driven methods for state estimation has become a key research focus.

Moreover, the topology of the distribution network changes during real operation, and data for these time-varying topologies are limited, complicating the training of the data-driven models mentioned earlier [

29]. Currently, research on state estimation with dynamic topologies is quite limited. The main approach is to leverage abundant data from other topological structures in the database to offset the lack of sample data for the new topology [

30]. For instance, reference [

31] introduced a model transfer method where the model is initially trained on the original topology, most layers are frozen, and then it is fine-tuned with limited data from the new topology. Similarly, reference [

32] combined artificial neural networks with transfer learning to develop a transfer neural state estimation method, allowing the current distribution network state estimator to adapt to other networks. Overall, using data-driven algorithms for distribution network state estimation is increasingly compatible with smart grid development, though research in the context of dynamic topologies still requires more focused exploration.

This paper addresses limitations of current methods, noting that parameter changes and measurement data uncertainty during operation limit traditional physical methods and reduce accuracy. It proposes i-ResNet, a modified residual neural network, to develop a state estimation model based on data analysis, requiring only small real-time and pseudo-measurements without complex parameters. The method is robust to data errors and improves operational efficiency. Due to frequent topology changes from system optimization, a time-varying topology state estimation based on migration learning is proposed, using historical data from source topologies and small new topology datasets to enhance data-driven effectiveness. Simulations across various networks confirm the approach’s efficacy.

The contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

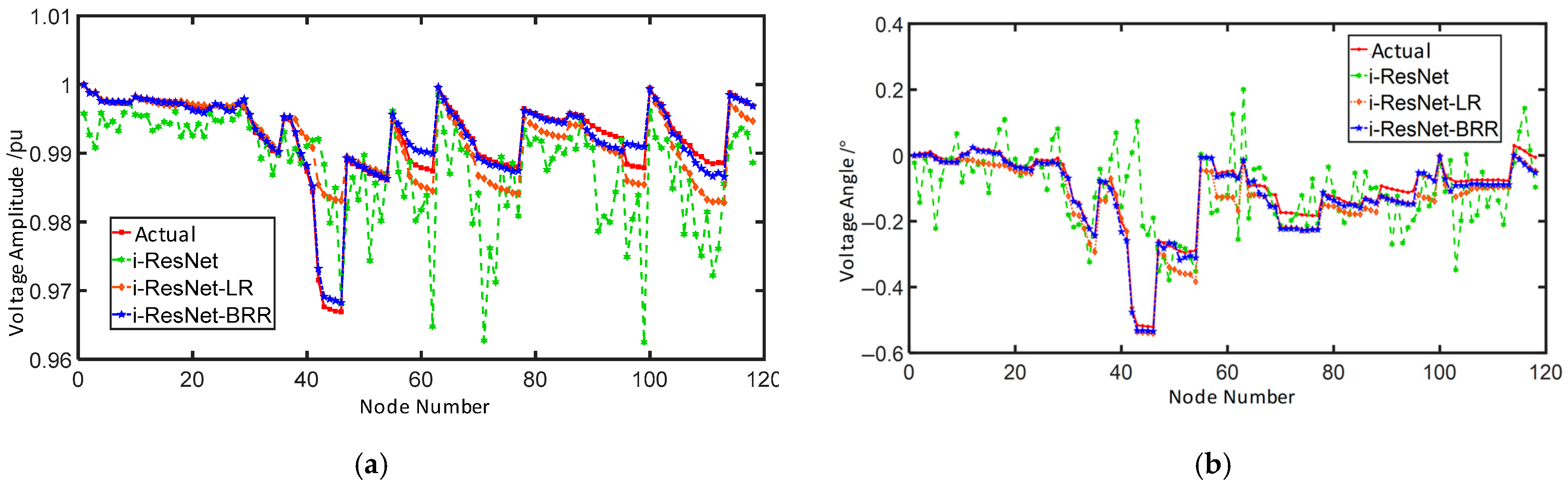

A refined i-ResNet state estimation approach is extended to analyze the influence of measured data and topology uncertainties on the operation state of distribution network. The proposed strategy enhances robustness against measurement noise while significantly improving computational efficiency, thereby meeting both accuracy and speed requirements.

- (2)

Experimental evaluations are performed on the IEEE 33-bus and 118-bus benchmark systems to assess the effectiveness of the proposed approach. The results confirm that the method achieves superior accuracy and faster convergence compared with conventional techniques, maintaining voltage magnitude errors consistently below 1%.

The rest of this article is structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces the i-ResNet model-based approach for state estimation, which considers data uncertainty.

Section 3 explores the impact of topology changes on state estimation outcomes and discusses potential improvements for handling topology uncertainty in practical applications. Case studies are presented in

Section 4. The article concludes with

Section 5.

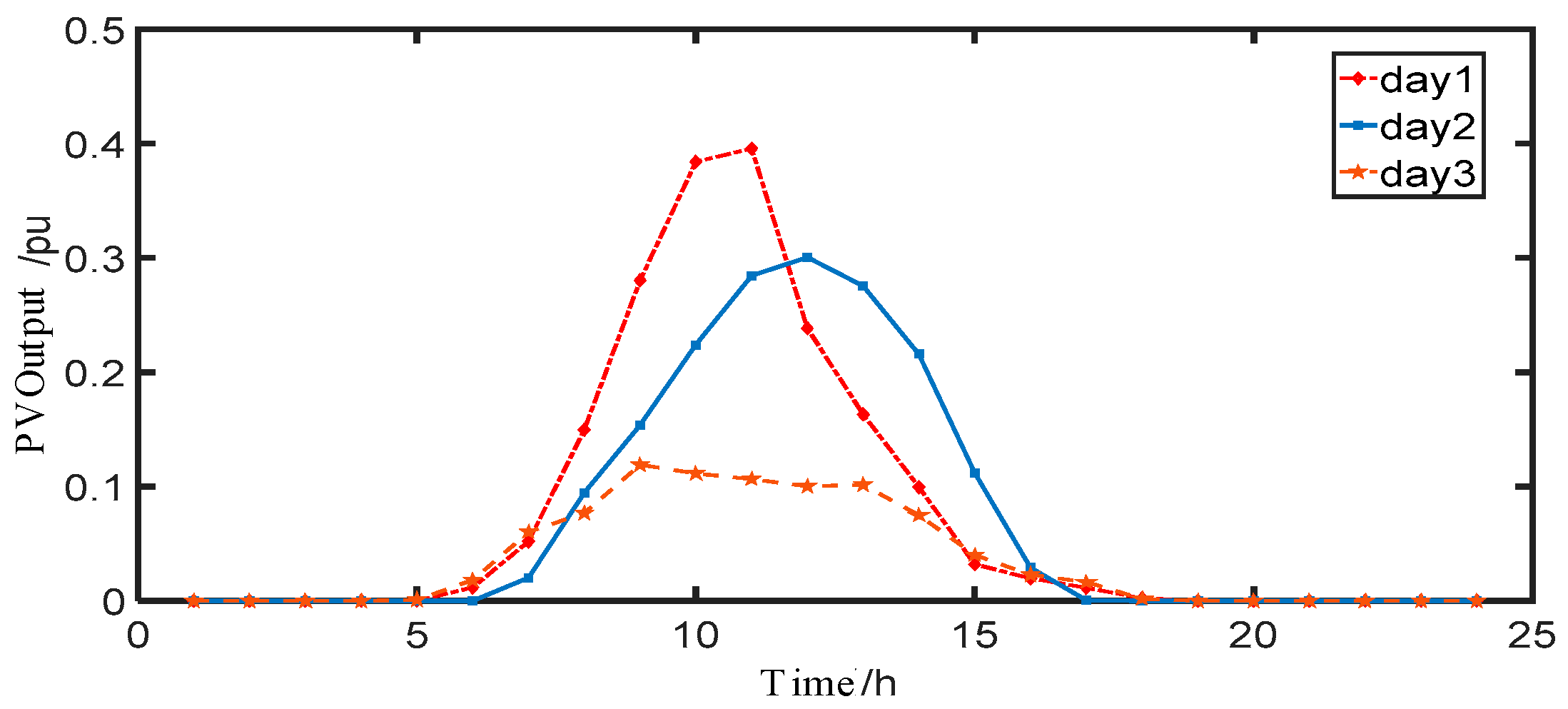

2. Distribution Network State Estimation Considering Data Uncertainty

Traditional distribution network state estimation struggles with practical challenges due to uncertainties in line parameters and measurement data arising from equipment aging, maintenance, and measurement errors. These uncertainties reduce estimation accuracy. Additionally, the iterative nature of standard physical models results in long computation times, making them unsuitable for the quick response needed in modern grids. The widespread integration of distributed energy resources has also changed distribution networks from simple, unidirectional power flow systems to complex, bidirectional ones. This shift introduces voltage volatility caused by renewable energy’s intermittency and peak output, potentially endangering grid stability.

This section introduces a new state estimation model using i-ResNet to overcome issues in line parameter accuracy, measurement reliability, and efficiency. It directly links measurements and state variables via offline training on historical data. During real-time use, the trained model quickly produces state estimates from current measurements, removing reliance on line parameters and showing improved resistance to measurement uncertainties.

2.1. Data-Driven State Estimation Model

Using artificial intelligence for power system monitoring and analysis is essential for developing smart grids. As AI technology progresses, diverse machine learning algorithms are increasingly used in the power sector. Data-driven models examine the spatial and temporal correlations in historical data, converting the distribution network state estimation from a problem based on line parameters and measurements into a process that directly addresses the nonlinear relationship between measurement data z and state variables x.

where

is the measurement matrix;

is the state variable matrix at the current time; and the function

is a nonlinear mapping function containing weights (

), reflecting the relationship between the input measurement values and the output state variables. The task of offline training is to find the weights that minimize the loss between predicted values and the actual states through training.

The AI training usually depends on extensive historical data to capture the nonlinear relationship between measurement and state variables. Distribution network databases hold large amounts of historical data from measurement devices like SCADA and PMUs, satisfying the needs for training data-driven models. Unlike traditional physical models, data-driven models use measurement data as input and state variables as output, eliminating the need for precise topology parameters and directly avoiding issues caused by line parameter uncertainties.

2.2. Variant of Deep Residual Network

This section begins by explaining the principles and benefits of Deep Residual Networks. It then introduces a specialized variant designed for the distribution network state estimation task and concludes by presenting the state estimation model based on this deep residual network.

2.2.1. Deep Residual Network

The Deep Residual Network (ResNet) [

33] is one of the most successful deep learning models in recent years. Building residual learning modules helps resolve problems such as vanishing or exploding gradients that can arise during deep neural network training. A deep residual network consists of a series of blocks, with the fundamental residual block shown in

Figure 1.

A residual block includes weight layers, activation functions, normalization, and identity mapping. The core component is the identity mapping, which helps lower the number of parameters and computational load. Additionally, residual blocks use skip connections to transfer input information quickly. The formula for a residual block is as follows:

where

and

represent the input and output of the current residual block, respectively;

F is the residual function. Each residual unit is a serial connection structure. Based on the above formula, the learned features of the overall residual network are as follows:

where

is the input to the residual neural network;

is the output. The structure of the residual network is shown in

Figure 2.

According to the chain rule, the gradient of the backward process can be obtained as

where

is the gradient reaching the loss function. The “1” in the parentheses indicates that the shortcut mechanism allows gradient propagation without attenuation, while the residual gradient is propagated through the weighted layers, not directly. The residual gradient will not always be −1, and even if the gradient is slight, the shortcut mechanism prevents gradient vanishing. Therefore, residual learning effectively addresses the vanishing/exploding gradient problem, improving efficiency.

For a specific domain, the process of optimizing model parameters can be summarized as the following optimization problem:

where

is the target regression function on the domain;

represents the parameters of this domain; and

represents the actual value.

2.2.2. Variant of Deep Residual Network

A state estimation model utilizing a deep residual neural network can be developed based on the previous discussion. Although deep residual neural networks are mainly used in image recognition and computer vision—areas with different task characteristics from the state estimation task described here—necessary adjustments are made to tailor the network to this study’s environment. This customized network is called i-ResNet, and its architecture is illustrated in

Figure 3.

The i-ResNet architecture includes a reshaping layer, multiple residual blocks, and extended residual blocks. The reshaping layer adjusts the dimension of the intermediate feature space. The extended residual block serves as the central component. Compared to traditional deep residual neural networks, the enhancements and their reasons are outlined as follows:

- (1)

Replacing the convolutional layers in standard residual blocks with fully connected layers improves processing of one-dimensional input data, such as branch active/reactive power and node injection active/reactive power. Fully connected layers effectively model the input-output relationship and help reduce model complexity [

34].

- (2)

Incorporating identity mappings on the left, similar to the traditional deep residual network, combines two residual blocks into a single extended residual block. This structure includes two basic residual blocks with skip connections that transfer feature information across non-adjacent layers, representing an improved version of the deep residual network [

35,

36]. The benefit of this approach is enhanced information flow and reduced information loss, allowing for more effective utilization of the residual network’s optimization potential.

- (3)

The Huber function serves as the loss function because of its robustness to outliers. The ReLU function is selected as the activation function, with its expression provided in Equation (6).

2.2.3. State Estimation Model Based on i-ResNet

Once the i-ResNet model structure is designed, the overall architecture of the proposed i-ResNet-based distribution network state estimation is illustrated in

Figure 4. It consists of several components: data preprocessing, offline training of the i-ResNet model, and online implementation. Each element is explained below.

- (1)

Data Preprocessing Unit

Initially, historical operational data from the distribution network is gathered, and an initial training dataset is created via random sampling. Next, because the data varies greatly in scale across the network, normalization is performed on all data to reduce the effects of differing variable scales during model training. Specifically,

where

represents the normalized data and

and

represent the maximum and minimum values in the dataset X, respectively. After standardization, the data

and is dimensionless. A specific error level is randomly added to the standardized data to simulate the errors of measurement devices in actual operation. Finally, the training set and test set are partitioned.

- (2)

Offline Training Phase

During the offline training phase, measurement data from various time points in the dataset are fed into the model through the input layer. Features are extracted with a reshaping layer, mapped to a high-dimensional space and passed through a series of residual blocks. After processing these residual blocks and another reshaping layer, the model outputs a state estimate and calculates if the accuracy meets the standards. If it does not, the loss function—comparing the estimated results with actual values—is computed, and parameters are updated using the optimizer. The Huber loss function is chosen for its robustness to outliers, combining the benefits of MSE and MAE, as shown in Equation (8). The Adam optimizer is used for training. Once the accuracy criteria are satisfied, the network parameters and the model are saved, and training terminates.

- (3)

Online Application Phase

During the online application phase, the measurement data from the current time step is fed into the trained model to produce the relevant state variable results rapidly. These results help inform the subsequent operation and dispatch of the distribution network.

3. Distribution Network State Estimation Considering Topology Uncertainty

The previously proposed i-ResNet-based model effectively captures the nonlinear relationship between states and measurements using historical data. It removes the need for exact line parameters, offers quick and precise estimates, and is robust against measurement noise. However, in real-world operations, distribution network topologies often change due to dispatch demands or unforeseen events, leading to topological uncertainty. When such changes occur, the lack of sufficient measurement devices often prevents obtaining accurate structural parameters quickly, making traditional physical models unsuitable. Additionally, a new topology’s limited operational history hampers data-driven approaches that depend on extensive historical data for training.

To address the state estimation problem for new topologies, this section introduces a transfer learning-based method. It creates links between source and target topologies, using inductive transfer to harness extensive historical data from source topologies to enhance performance on the target topology.

3.1. Topology Uncertainty in Distribution Networks

Unlike the stable topology of transmission networks, distribution network structures frequently change due to operational scheduling or unexpected events [

37], with modifications happening from weeks to months [

38]. The growing integration of renewable energy sources and variable loads adds more uncertainty, sometimes causing system state changes hourly [

39]. Some adjustments are planned, like network reconfiguration for economic reasons after DER integration [

40], but many are unplanned and challenging to predict, such as line aging or fault outages [

41].

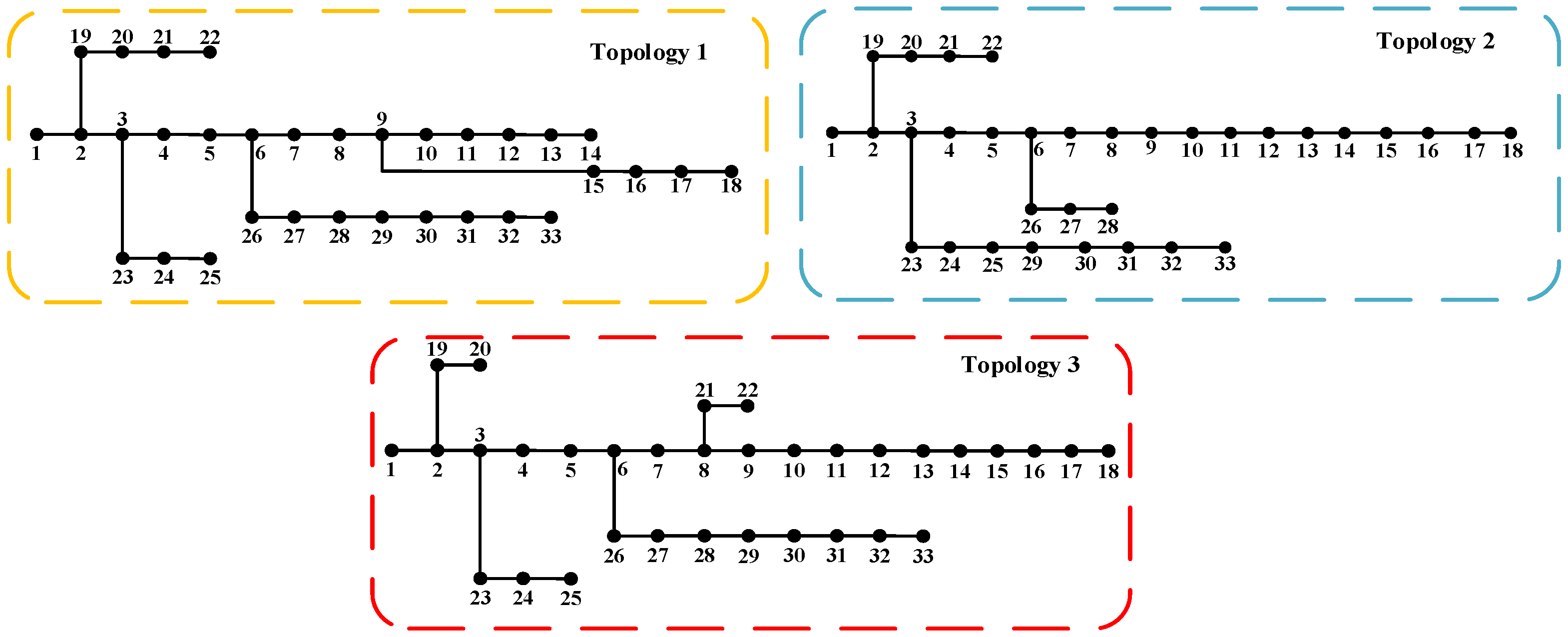

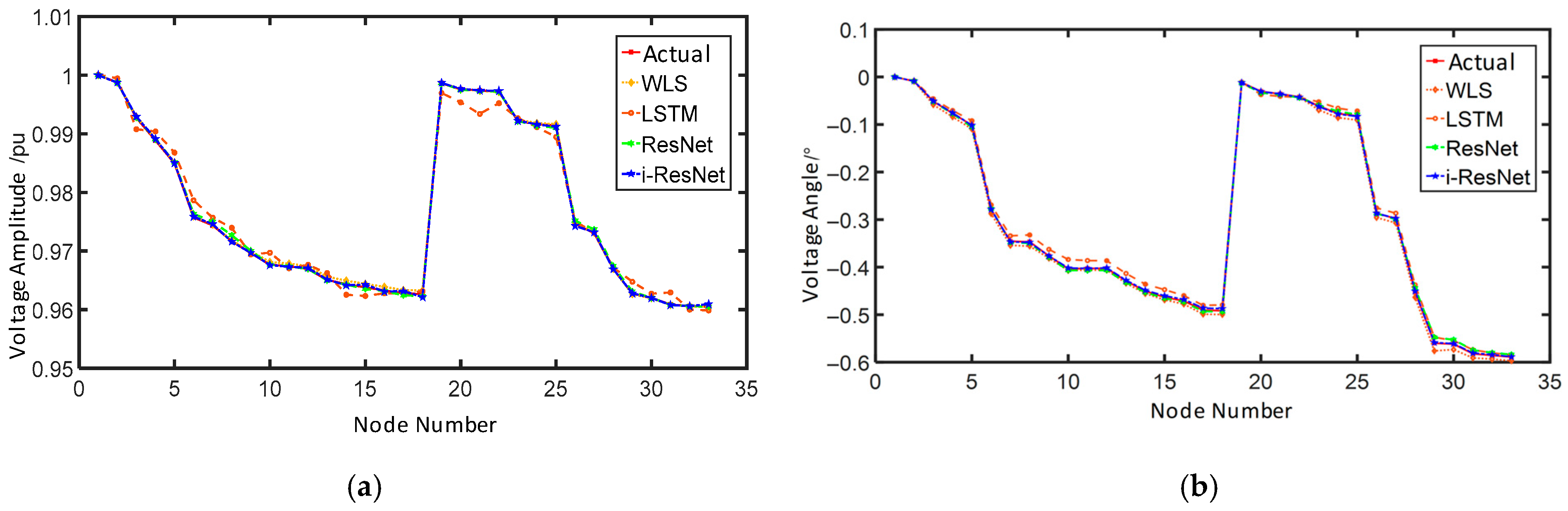

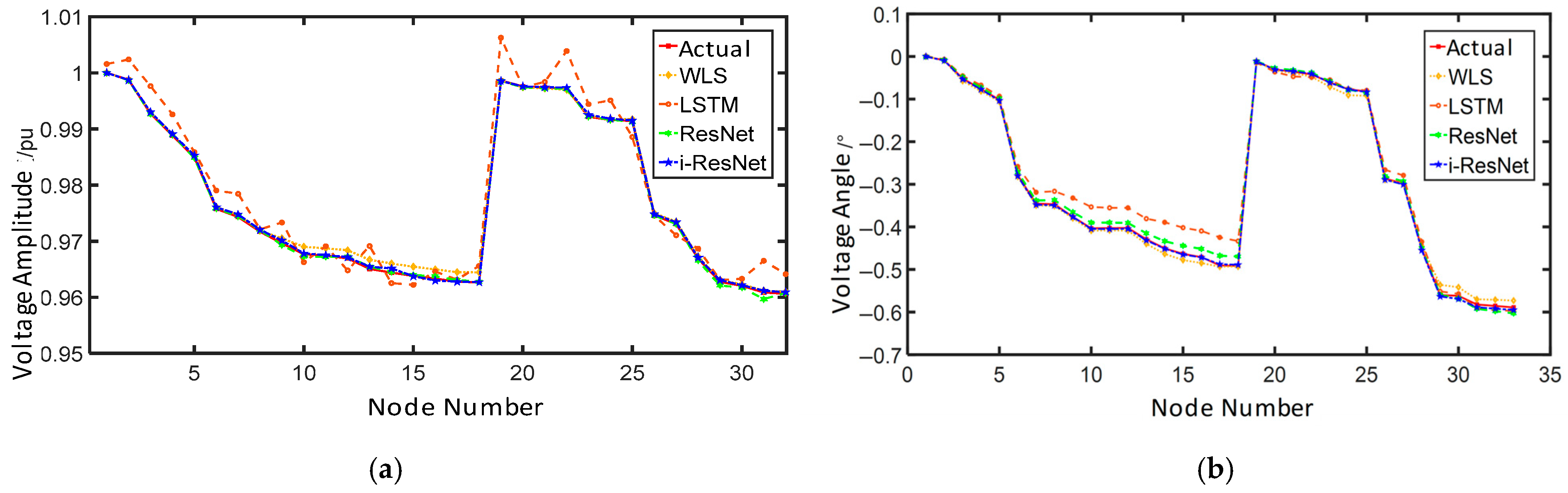

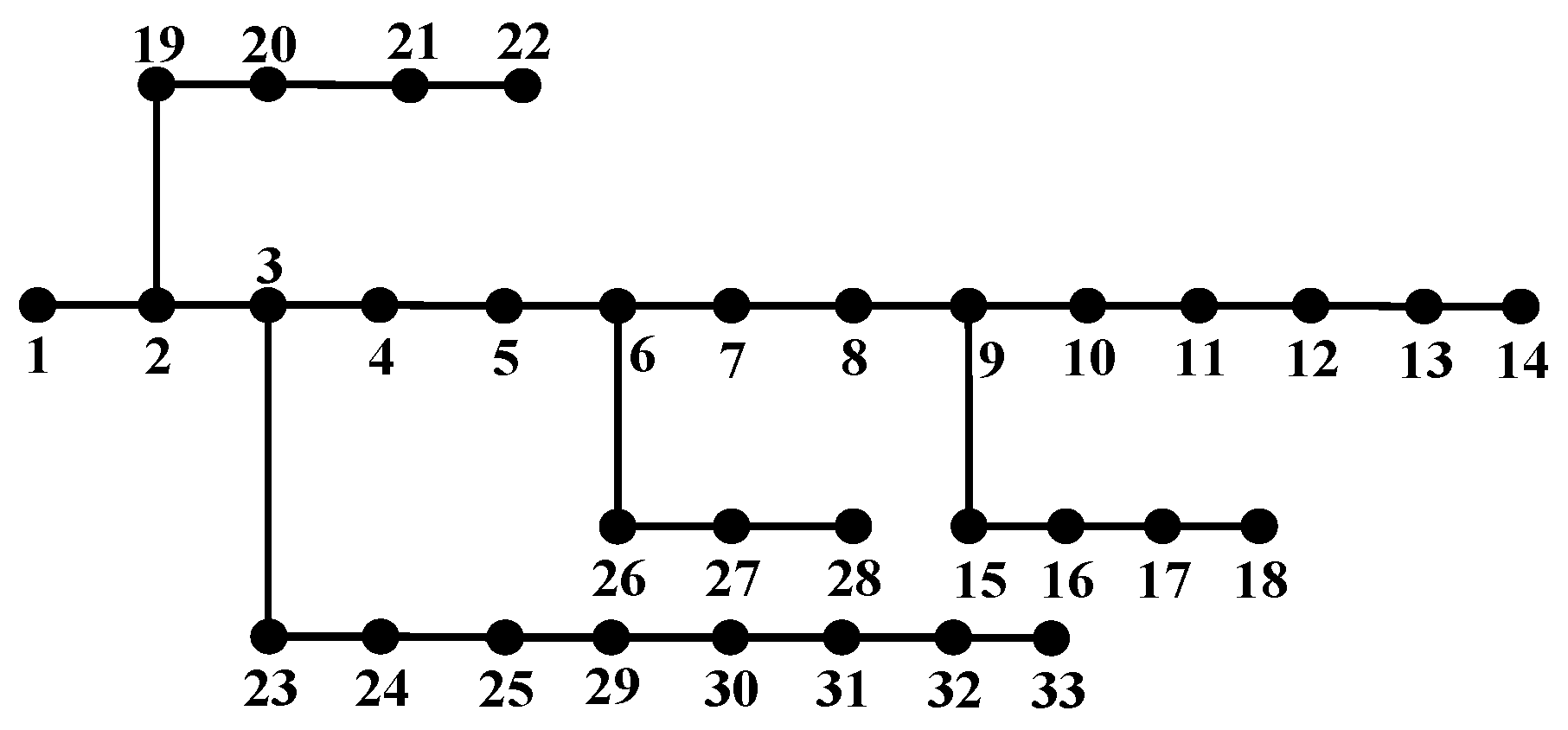

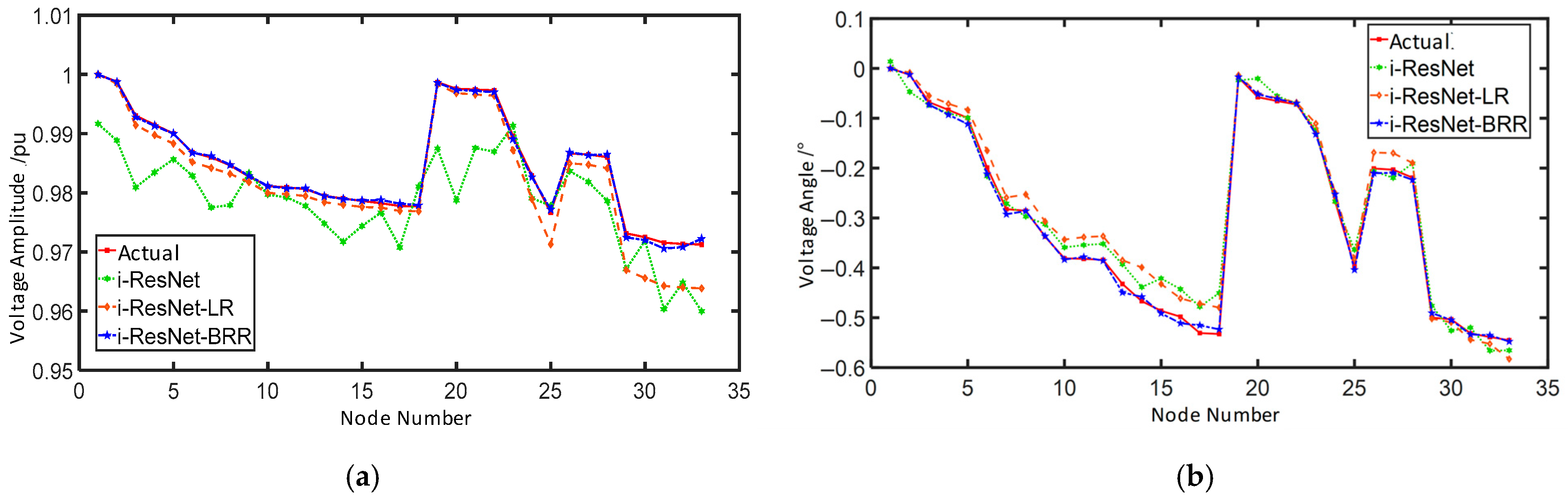

Using the IEEE 33-bus system as an example,

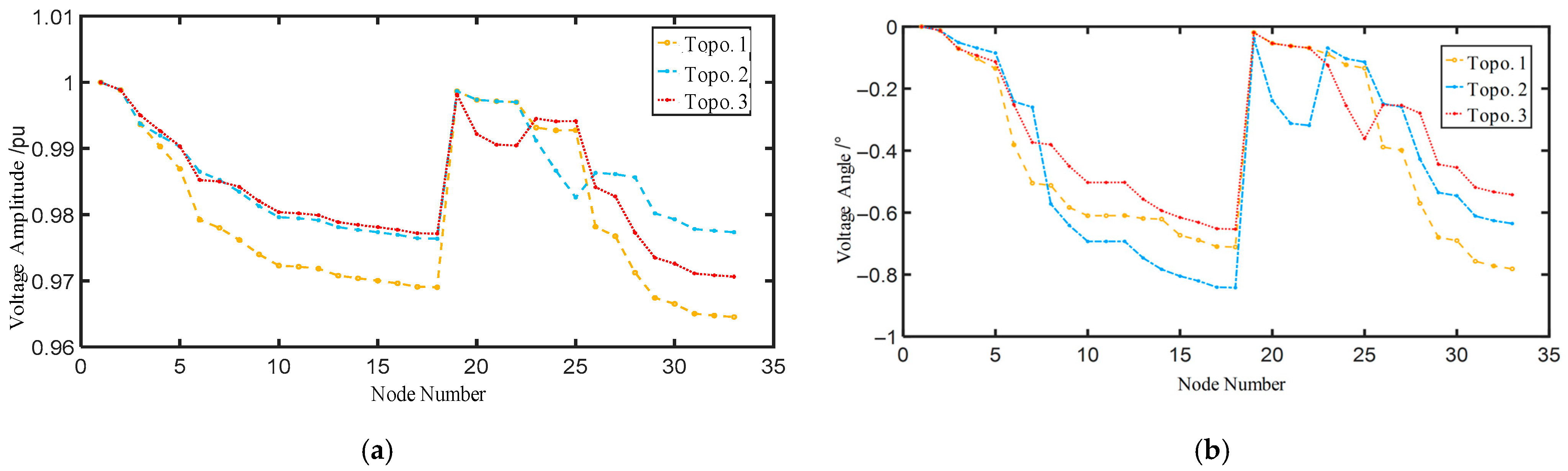

Figure 5 illustrates three distinct topological configurations. At the same time,

Figure 6 compares their operational states—specifically, node voltage magnitudes and phase angles, which are the state variables considered in this work—at a specific moment.

Figure 6 clearly illustrates how changes in the distribution network topology lead to notable variations in voltage magnitude and phase angle profiles. This demonstrates that a state estimation model trained only on the original topology cannot reliably estimate the operational features of a new target topology.

Frequent topological changes and the absence of real-time measurement devices hinder the acquisition of precise and timely line parameters and topology data, limiting the effectiveness of traditional physical models. The i-ResNet model introduced in previous section, which does not rely on topology parameters, faces difficulties due to limited operational data for new topologies, making accurate training impossible. To overcome the issue of topology uncertainty, this section presents a distribution network state estimation model that leverages transfer learning.

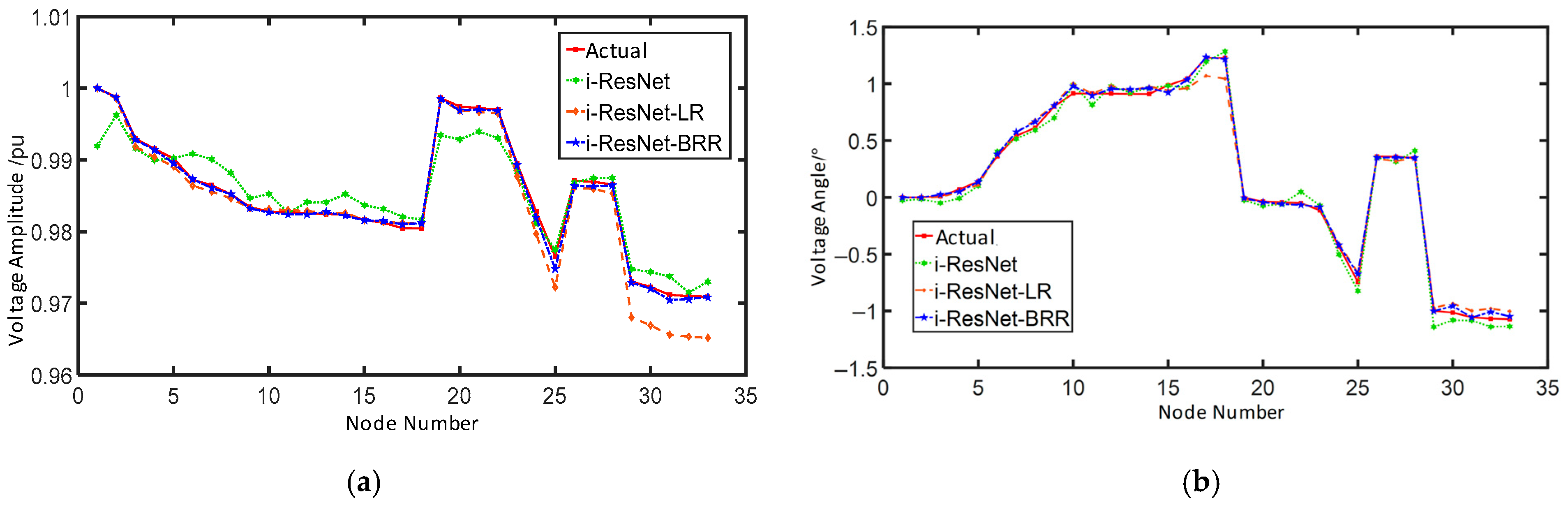

3.2. Transfer Learning-Based State Estimation Model

Based on the analysis in

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2 and using the IEEE 33-bus system as an example, the potential for applying transfer learning to this problem is evident from

Figure 6. While operational states vary significantly across different topologies, certain nodes exhibit similarities. For instance, Topology 2 and Topology 3 show comparable voltage magnitude patterns at nodes 1–18, whereas Topology 1 and Topology 2 are identical at nodes 19–23. Moreover, ample labeled data exists for other topologies, indicating that data from various topologies can compensate for the limited data in a new target topology, making transfer learning highly suitable. For practical purposes, this paper utilizes inductive transfer learning.

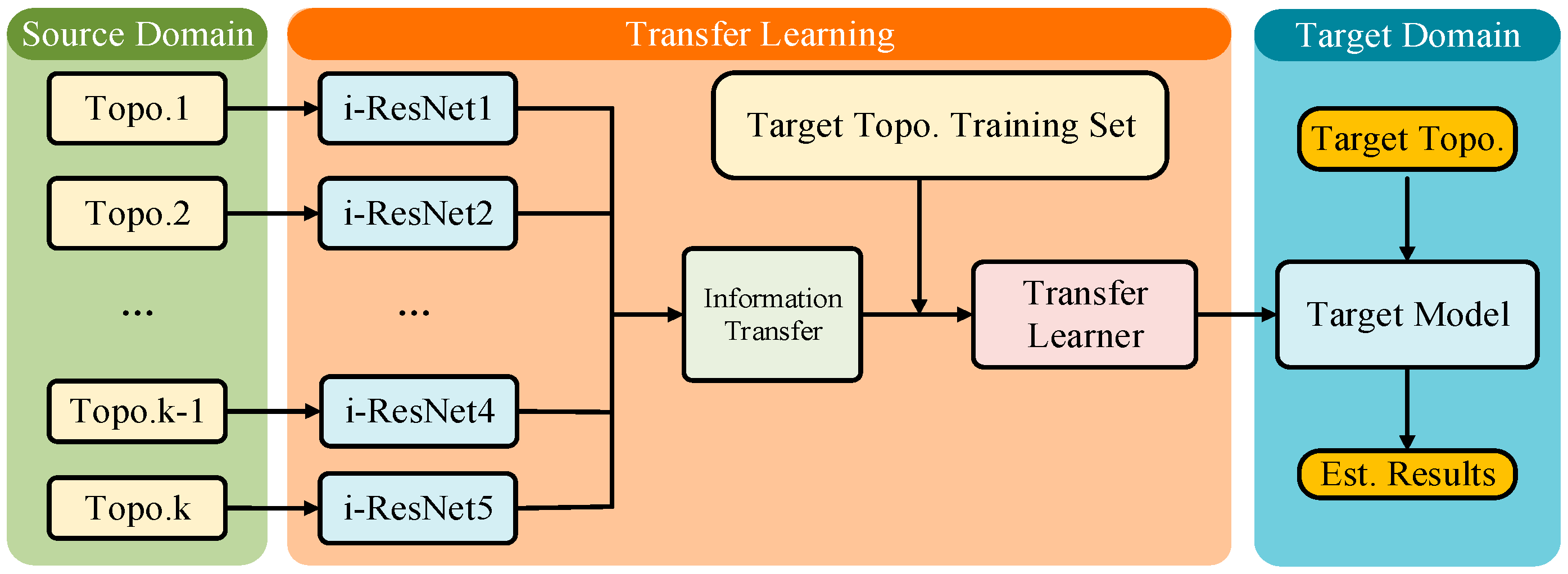

Estimating time-varying topology states involves identifying the recently changed topology as the target domain and linking it to known topologies in a database, which act as source domains. Knowledge transfer is then employed to develop an estimation model for the modified topology. This process is depicted in

Figure 7.

The transfer-combined state estimation model involves several steps: initially, historical measurement data from various source topologies are gathered from the database, and corresponding source topology state estimation models are trained using the i-ResNet model introduced in

Section 2. Next, a small set of measurement data from the new (target) topology is used to combine these source models and determine their respective weights. Finally, the combined model estimates the state of the target topology. Unlike training a dedicated model for each topology as described in

Section 2, this approach primarily leverages pre-trained i-ResNet models from other topologies, which are then combined with limited data from the target topology to create an accurate state estimation model for the current topology. Since the process of generating source domain models with i-ResNet was detailed in the previous section, the following section discusses the model combination strategy.

A traditional linear combination model is often expressed as

The limitation of this method is its reliance on fixed weights wᵢ and the need for a specific causal connection between input and output, which results in subpar performance with nonlinear problems. To overcome this, this paper adopts Bayesian Ridge Regression (BRR) [

42].

According to Bayesian regression theory [

43], the state estimate at time t is assumed to be

where

corresponds to the weight of the

-th source topology model;

represents the estimation result of the

-th model at time t;

is the noise, distinguishing it from linear regression, and

is assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution with zero mean and variance

:

Based on Equation (11), the probability density of the observed data likelihood function can be expressed as

where

represents the target topology dataset and

is the Bayesian model weight vector. Thus, the model combination problem transforms into deriving the conditional distribution of the weights w.

Applying Bayes’ theorem, and assuming a prior distribution for the parameters

N(0,Σ

p), the posterior probability can be derived:

Based on Equation (13), the posterior distribution of w is derived from the likelihood function, observed data, and prior distribution. Hence, the posterior distribution for w is as follows:

where

. Given a test measurement dataset

, the predictive distribution for the state estimate is obtained by averaging over all parameters and the posterior weight distribution:

Bayesian Ridge Regression is a common type of Bayesian regression, which assumes that the prior distribution for the weights w is a spherical Gaussian [

44,

45]:

where the prior parameter λ follows a Gamma distribution. The resulting model is called Bayesian Ridge Regression. During model fitting, the parameters

and λ are estimated jointly.

As a probabilistic model, Bayesian Ridge Regression may produce parameters that slightly differ from those derived using ordinary least squares. Nonetheless, it generally offers greater stability in complex situations. The derivation process also shows that this method can fully utilize data, which makes it especially effective in scenarios with limited operational data, topological uncertainty, and changing topologies, like those encountered in this study. This advantage is similarly observed in other fields where data is challenging to obtain [

46]; for instance, in medical diagnostics, probabilistic models like Naïve Bayes have been successfully applied to migraine classification using limited patient data augmented with synthetic samples [

6].

5. Conclusions

The widespread integration of distributed energy resources and variable loads has introduced significant volatility in distribution networks. To maintain stable grid operation, ensure reliable power supply, and build resilient smart grids, this paper addresses operational uncertainties by focusing on distribution system state estimation, primarily exploring two key areas: measurement systems for distribution networks and state estimation algorithms.

To tackle uncertainties in line parameters and measurement data that hinder the application of physical models, an i-ResNet-based state estimation model has been developed. This model trains on historical measurements and state variables from databases, eliminating the need for line parameters and avoiding errors caused by parameter inaccuracies. Experimental results confirm the method’s high accuracy even with substantial measurement errors, demonstrating strong robustness. Furthermore, this model outperforms traditional physical models in computational efficiency, delivering faster results to dispatch centers for operational decisions.

It should be noted that this study primarily addresses measurement uncertainties and limited observability in conventional distribution system operations. While the proposed method exhibits certain robustness to random errors and anomalous data through the Huber loss function and Bayesian ridge regression ensemble characteristics, we recognize that coordinated false data injection attacks represent a distinct category of cybersecurity threats that require specialized protection mechanisms. This important direction will be a focus of our future research.

For scenarios with limited historical data following topology changes during distribution network operation, a transfer learning-based state estimation model is introduced. This approach leverages correlations between source and target topologies to transfer knowledge from data-rich domains to data-scarce scenarios, effectively overcoming limitations of traditional data-driven training and significantly improving estimation accuracy. Tests across networks of varying scales and configurations validate the model’s enhanced performance and consistent accuracy.

While the methods proposed in this paper demonstrate effectiveness across multiple case studies, certain limitations remain. The transfer learning-based time-varying topology state estimation requires some operational data from the target topology, suggesting the need to explore zero-shot learning scenarios in future work. Although this transfer learning method approximates actual operational states reasonably well, its performance still trails models trained with sufficient samples. Subsequent research will focus on further improving estimation accuracy while considering the integration of cybersecurity protection mechanisms to enhance system resilience against various threats.