Review of Active Distribution Network Planning: Elements in Optimization Models and Generative AI Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- A comprehensive review of key concepts in passive and active distribution system planning, covering time horizons, objectives, decision variables, and technical constraints. This is supplemented by a comparison of different OPF formulations, uncertainty techniques, and flexible planning tools.

- 2.

- A structured review and categorization of generative AI models for power systems, with emphasis on scenario generation, uncertainty modeling, optimization, and decision support, and a focused analysis of their application to planning in ADNs.

2. Elements of the Distribution Network Planning Problem

2.1. Planning Horizons

2.2. Planning Objectives

2.3. Decision Variables

2.3.1. Traditional Planning Strategies

2.3.2. Flexible Planning Strategies

2.4. Planning Constraints

2.5. Type of Planning Variables

2.6. Uncertainty Modelling Techniques

3. Literature Review of OPF Planning Models

3.1. Linear Programming

3.2. Mixed-Integer Linear Programming

3.3. Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming

3.4. Convex Relaxation Methods

3.5. Metaheuristic Methods

3.6. Dynamic OPF Planning Models and Tools with Flexibility

4. ADN Trends: Generative AI Models, Applications and Future Asset Expansions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Alternating Current |

| ADN | Active Distribution Network |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| DC | Direct Current |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resources |

| DG | Distributed Generation |

| DR | Demand Response |

| DSO | Distribution System Operator |

| ESS | Energy Storage System |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| EVCS | Electric Vehicle Charging Station |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| IGDT | Information Gap Decision Theory |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LP | Linear Programming |

| LV | Low Voltage |

| MC | Monte Carlo |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

| MINLP | Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming |

| MV | Medium Voltage |

| NLP | Nonlinear Programming |

| OPEX | Operational Expenditure |

| OPF | Optimal Power Flow |

| Probability Density Function | |

| PEV | Plug-in Electric Vehicle |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| SOC | Second-Order Cone |

| TOTEX | Total Expenditure |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid |

| VAE | Variational Autoencoder |

| VPP | Virtual Power Plant |

References

- Jiang, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Du, Q.; Gao, X.; Qi, S.; Zou, H. Research on an Active Distribution Network Planning Strategy Considering Diversified Flexible Resource Allocation. Processes 2025, 13, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, T.; Zang, S. A Review of Optimization Scheduling for Active Distribution Networks with High-Penetration Distributed Generation Access. Energies 2025, 18, 4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastgou, A. Distribution network expansion planning: An updated review of current methods and new challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 114062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; De, M. Resilience-oriented planning for active distribution systems: A probabilistic approach considering regional weather profiles. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 158, 109976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Chen, W.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, W. Distribution network planning considering active response of EVs and DTR of cables and transformers. High Volt. 2025, 10, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anadón Martínez, V.; Sumper, A.; Saldaña-Gonzalez, A.E.; Gadelha, V. Planning fast-charging stations along highways using probability distribution functions and traffic data. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 82, 104547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña-González, A.E.; Aragüés-Peñalba, M.; Sumper, A. Distribution network planning method: Integration of a recurrent neural network model for the prediction of scenarios. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 229, 110125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distributed Flexibility: Lessons Learned in the Nordics; Nordic Energy Research: Oslo, Norway, 2022.

- Li, R.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, W. A review of optimal planning active distribution system: Models, methods, and future researches. Energies 2017, 10, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borousan, F.; Hamidan, M.A. Distributed power generation planning for distribution network using chimp optimization algorithm in order to reliability improvement. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 217, 109109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, T.D.; Soares, J.; Lezama, F.; Franco, J.F.; Vale, Z. A risk-based planning approach for sustainable distribution systems considering EV charging stations and carbon taxes. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2023, 14, 2294–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, T.D.; Tabares, A.; Arias, N.B.; Franco, J.F. Investment & generation costs vs. CO2 emissions in the distribution system expansion planning: A multi-objective stochastic programming approach. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 131, 106925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wei, R.; Wang, L.; He, H.; Wu, X. Resilience enhancement of distribution network under typhoon disaster based on two-stage stochastic programming. Appl. Energy 2023, 338, 120892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Han, Y.; Chen, S.; Yang, P.; Mahmoud, K.; Darwish, M.M.; Matti, L.; Zalhaf, A.S. A multiple uncertainty-based bi-level expansion planning paradigm for distribution networks complying with energy storage system functionalities. Energy 2023, 275, 127511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Kamel, S.; Hassan, M.H.; Tostado-Véliz, M.; Zawbaa, H.M. An improved wild horse optimization algorithm for reliability based optimal DG planning of radial distribution networks. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 582–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Chakraborty, A.K. Planning of EV charging station with distribution network expansion considering traffic congestion and uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 3810–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.E.; Kazemi-Razi, S.M.; Marzband, M.; Ikpehai, A.; Abusorrah, A. Multi-objective stochastic techno-economic-environmental optimization of distribution networks with G2V and V2G systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 218, 109195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, P.; Dejamkhooy, A.; Davoudkhani, I.F. Efficient expansion planning of modern multi-energy distribution networks with electric vehicle charging stations: A stochastic MILP model. Sustain. Energy, Grids Networks 2024, 38, 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaramaiah, K.; Sujatha, P. Optimal DG unit placement in distribution networks by multi-objective whale optimization algorithm & its techno-economic analysis. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 214, 108869. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Qiu, J.; Tao, Y.; Sun, X. Planning of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations with PV and Energy Storage Using a Fuzzy Inference System. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 10, 5894–5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S.; Sahoo, N.C.; Das, D. Mono-and multi-objective planning of electrical distribution networks using particle swarm optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 2011, 11, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S.; Sahoo, N.; Das, D. Multi-objective planning of electrical distribution systems using dynamic programming. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2013, 46, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y. Second-order cone model for active distribution network expansion planning. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting, Denver, CO, USA, 26–30 July 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, A.; Monsef, H.; Lesani, H. Integrated distribution network expansion planning incorporating distributed generation considering uncertainties, reliability, and operational conditions. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2015, 73, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, P. Active distribution network expansion planning integrating dispersed energy storage systems. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2016, 10, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitizadeh, M.; Vahed, A.A.; Aghaei, J. Multistage distribution system expansion planning considering distributed generation using hybrid evolutionary algorithms. Appl. Energy 2013, 101, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Sun, J.; Ai, S.; Xiong, X.; Wan, Y.; Yang, D. Distribution network planning integrating charging stations of electric vehicle with V2G. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2014, 63, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Sun, Q.; Gu, W.; Chen, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, J. AC/DC hybrid distribution system expansion planning under long-term uncertainty considering flexible investment. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 94956–94967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, P.G.; Papadaskalopoulos, D.; Strbac, G. Co-Optimization of Generation Expansion Planning and Electric Vehicles Flexibility. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 7, 1609–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidpour, H.; Aghaei, J.; Pirouzi, S.; Dehghan, S.; Niknam, T. Flexible, reliable, and renewable power system resource expansion planning considering energy storage systems and demand response programs. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2019, 13, 1862–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.K.; Mukherjee, V.; Yadav, V.K.; Ghosh, S. Constraints for effective distribution network expansion planning: An ample review. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2020, 11, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Hu, Z.; Yang, L.; Wang, J. Expansion planning of active distribution system considering multiple active network managements and the optimal load-shedding direction. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 115, 105451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahman, J.M.; Perić, D.M. Radial distribution network planning under uncertainty by applying different reliability cost models. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 117, 105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadoria, V.S.; Pal, N.S.; Shrivastava, V. Artificial immune system based approach for size and location optimization of distributed generation in distribution system. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2019, 10, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.K.; Yadav, V.K.; Mukherjee, V.; Ghosh, S. A multi-criteria approach for distribution network expansion through pooled MCDEA and Shannon entropy. Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst. 2019, 20, 20190043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugranlı, F. Analysis of renewable generation’s integration using multi-objective fashion for multistage distribution network expansion planning. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 106, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Quevedo, P.M.; Munoz-Delgado, G.; Contreras, J. Impact of electric vehicles on the expansion planning of distribution systems considering renewable energy, storage, and charging stations. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 10, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrjerdi, H. Simultaneous load leveling and voltage profile improvement in distribution networks by optimal battery storage planning. Energy 2019, 181, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo, A.V.; Murta-Pina, J.; Pires, V.F. Multiobjective formulation of the integration of storage systems within distribution networks for improving reliability. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2017, 148, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, A.; Yang, Q. State-of-the-art techniques for modelling of uncertainties in active distribution network planning: A review. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 1509–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aien, M.; Hajebrahimi, A.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M. A comprehensive review on uncertainty modeling techniques in power system studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aien, M.; Rashidinejad, M.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M. On possibilistic and probabilistic uncertainty assessment of power flow problem: A review and a new approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 37, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Moger, T.; Jena, D. Uncertainty handling techniques in power systems: A critical review. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 203, 107633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeed, M.; Aleem, S.H.A. Overview of uncertainties in modern power systems: Uncertainty models and methods. In Uncertainties in Modern Power Systems; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Khator, S.K.; Leung, L.C. Power distribution planning: A review of models and issues. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 1997, 12, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temraz, H.K.; Quintana, V.H. Distribution system expansion planning models: An overview. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 1993, 26, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabirifar, M.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Moeini-Aghtaie, M.; Pourghaderi, N.; Dehghanian, P. A bi-level framework for expansion planning in active power distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 37, 2639–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wu, Q. Many-objective interactive optimization and decision making for distribution network expansion planning. Control Eng. Pract. 2021, 116, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi-Siab, M.; Lesani, H. Distribution expansion planning in the presence of plug-in electric vehicle: A bilevel optimization approach. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 121, 106076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Xiang, Y.; Gu, C.; Liu, J. Optimal planning of distribution systems and charging stations considering PV-Grid-EV transactions. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 16, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, X.; Xu, Y.; Shen, X. Distribution network expansion planning approach for large scale electric vehicles accommodation. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 14, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña-González, A.E.; Sumper, A.; Anadón-Martínez, V.; Aragüés-Peñalba, M. A machine learning approach for EVCS integration in distribution network based on optimal investment actions. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2026, 252, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelha, V.; Bullich-Massagué, E.; Sumper, A. Optimal Power Flow in electrical grids based on power routers. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 234, 110581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelha, V.; Sumper, A.; Bullich-Massague, E. Impact of converter losses in optimal power flow for hybrid AC-DC networks based on power routers. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, B.; Debusschere, V.; Caire, R. Short-term active distribution network operation with convex formulations of power flow. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Manchester PowerTech, Manchester, UK, 18–22 June 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.; Gu, W.; Zhou, S.; Huang, H.; Gao, S.; Han, J.; Wu, Z.; Dou, X. Optimal planning of electric vehicle charging stations comprising multi-types of charging facilities. Appl. Energy 2018, 226, 1087–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh-Roshanagh, R.; Zare, K.; Marzband, M. An a-posteriori multi-objective optimization method for MILP-based distribution expansion planning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 60279–60292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, A.; Elkamel, A.; Mazouz, A. An improved hybrid particle swarm optimization and tabu search algorithm for expansion planning of large dimension electric distribution network. Energies 2019, 12, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bødal, E.F.; Lakshmanan, V.; Sperstad, I.B.; Degefa, M.Z.; Hanot, M.; Ergun, H.; Rossi, M. Demand flexibility modelling for long term optimal distribution grid planning. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2022, 16, 5002–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, M.; Ergun, H.; Rossi, M. FlexPlan. jl-An open-source Julia tool for holistic transmission and distribution grid planning. In Proceedings of the 2023 Open Source Modelling and Simulation of Energy Systems (OSMSES), Aachen, Germany, 27–29 March 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, U.P.; Schachler, B.; Scharf, M.; Bunke, W.D.; Günther, S.; Bartels, J.; Pleßmann, G. Integrated techno-economic power system planning of transmission and distribution grids. Energies 2019, 12, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidler, A.; Thurner, L.; Braun, M. Heuristic optimisation for automated distribution system planning in network integration studies. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2018, 12, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Wang, B.; Sun, Y.; Song, X.; Watada, J. Conditional style-based generative adversarial networks for renewable scenario generation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 38, 1281–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Zhu, R.; Chen, D.; Li, C.; Gu, W.; Qian, X.; Yu, W. A cross-modal generative adversarial network for scenarios generation of renewable energy. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 39, 2630–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hong, T. Generating realistic building electrical load profiles through the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). Energy Build. 2020, 224, 110299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, B.; Yuan, R.; Watada, J. Rolling unit commitment based on dual-discriminator conditional generative adversarial networks. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 205, 107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Jain, A.; Hooi, B. Exgan: Adversarial generation of extreme samples. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 19–21 May 2021; Volume 35, pp. 6750–6758. [Google Scholar]

- Kaselimi, M.; Doulamis, N.; Voulodimos, A.; Doulamis, A.; Protopapadakis, E. EnerGAN++: A generative adversarial gated recurrent network for robust energy disaggregation. IEEE Open J. Signal Process. 2020, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xiong, H.; Chen, Y. Diffcharge: Generating ev charging scenarios via a denoising diffusion model. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 3936–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. Customized load profiles synthesis for electricity customers based on conditional diffusion models. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 4259–4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Mao, Z.; Sun, Y.; Xu, X. Short-term wind power scenario generation based on conditional latent diffusion models. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2023, 15, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wen, Q.; Zhang, C.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y. DiffLoad: Uncertainty quantification in electrical load forecasting with the diffusion model. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 40, 1777–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulaguiem, Y.; Zscheischler, J.; Vignotto, E.; van der Wiel, K.; Engelke, S. Modeling and simulating spatial extremes by combining extreme value theory with generative adversarial networks. Environ. Data Sci. 2022, 1, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razghandi, M.; Zhou, H.; Erol-Kantarci, M.; Turgut, D. Variational autoencoder generative adversarial network for synthetic data generation in smart home. In Proceedings of the ICC 2022-IEEE International Conference on Communications, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 16–20 May 2022; pp. 4781–4786. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y.; Hu, W.; Dong, Y.; Fan, Y.; Dong, L.; Xiao, M. Optimal configuration of concentrating solar power in multienergy power systems with an improved variational autoencoder. Appl. Energy 2020, 274, 115124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.A.; Hammad, A.; Eshraghi, P. Generation of whole building renovation scenarios using variational autoencoders. Energy Build. 2021, 230, 110520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langevin, A.; Carbonneau, M.A.; Cheriet, M.; Gagnon, G. Energy disaggregation using variational autoencoders. Energy Build. 2022, 254, 111623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhu, R.; Li, G.; Song, L. Scenario forecasting for wind power using flow-based generative networks. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Liao, W.; Wang, S.; Bak-Jensen, B.; Pillai, J.R. Modeling daily load profiles of distribution network for scenario generation using flow-based generative network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 77587–77597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, E.; Paeleke, L.; Mitsos, A.; Dahmen, M. Normalizing flow-based day-ahead wind power scenario generation for profitable and reliable delivery commitments by wind farm operators. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2022, 166, 107923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, J.; Wehenkel, A.; Lanaspeze, D.; Cornélusse, B.; Sutera, A. A deep generative model for probabilistic energy forecasting in power systems: Normalizing flows. Appl. Energy 2022, 305, 117871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhenyuan, D.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Z. Probabilistic PV power forecasting by a multi-modal method using GPT-agent to interpret weather conditions. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 19th Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA), Kristiansand, Norway, 5–8 August 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, J.; Zhao, Y. Generative pre-trained transformers (GPT)-based automated data mining for building energy management: Advantages, limitations and the future. Energy Built Environ. 2024, 5, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, P.; Sahu, A.; Graf, P. Buildingsbench: A large-scale dataset of 900k buildings and benchmark for short-term load forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 19823–19857. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.L.; Jain, R.; Emami, P.; Wadsack, K.; Ding, F.; Sun, H.; Gruchalla, K.; Hong, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; et al. eGridGPT: Trustworthy AI in the Control Room; Technical report; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, J. Automated data mining framework for building energy conservation aided by generative pre-trained transformers (GPT). Energy Build. 2024, 305, 113877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Lu, J.; Zhao, Y. Domain-specific large language models for fault diagnosis of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems by labeled-data-supervised fine-tuning. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accurso, J.; Mendy, R.; Torres, A.; Tang, Y. A ChatGPT-like Solution for Power Transformer Condition Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Jacksonville, FL, USA, 15–17 December 2023; pp. 1716–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Zaboli, A.; Choi, S.L.; Song, T.J.; Hong, J. Chatgpt and other large language models for cybersecurity of smart grid applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Seattle, WA, USA, 21–25 July 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, M.; Cui, Z.; Hug, G. Enabling large language models to perform power system simulations with previously unseen tools: A case of daline. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.17215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, P.; Li, Z.; Sinha, S.; Nguyen, T. SysCaps: Language interfaces for simulation surrogates of complex systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.19653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadia, R.S.; Trindade, F.C.; Freitas, W.; Venkatesh, B. On the potential of chatgpt to generate distribution systems for load flow studies using opendss. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 5965–5968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, S.; Liu, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y. Large foundation models for power systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Seattle, WA, USA, 21–25 July 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D.; Chen, X. Large language models as optimizers. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Pensacola, FL, USA, 5–7 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Yin, C.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; She, Y.; Yu, Y. Research on Intelligent Matching Technology of Power Grid Dispatching Automation Emergency Plan Based on Large Model and Small Sample LoRA Fine-Tuning Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE), Shanghai, China, 11–13 April 2024; pp. 1390–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Xu, Y. Real-time optimal power flow with linguistic stipulations: Integrating GPT-agent and deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 39, 4747–4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siino, M.; Tinnirello, I. Gpt prompt engineering for scheduling appliances usage for energy cost optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Measurements & Networking (M&N), Rome, Italy, 2–5 July 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Shen, R.; Jin, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Chen, J.; Jiang, W. Instruction tuning text-to-sql with large language models in the power grid domain. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Control, Robotics and Intelligent System; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, Z. CPGA-BOT: A Customized Power Grid Assistant chatBOT Fine-Tuning in Large Language Model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Information Science, Parallel and Distributed Systems (ISPDS), Guangzhou, China, 31 May–2 June 2024; pp. 597–601. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, C.; Du, K.; Nong, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L.; Yan, B.; Zhang, X. PowerPulse: Power energy chat model with LLaMA model fine-tuned on Chinese and power sector domain knowledge. Expert Syst. 2024, 41, e13513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, J.; Cao, Y.; Yang, C.; Cai, X. A large language model for advanced power dispatch. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, G. Cooperative planning of renewable energy generation and multi-timescale flexible resources in active distribution networks. Appl. Energy 2024, 356, 122429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, M.; Xu, Z.; He, Y. Generative adversarial network assisted stochastic photovoltaic system planning considering coordinated multi-timescale volt-var optimization in distribution grids. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 153, 109307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Passive Distribution Network | Active Distribution Network |

|---|---|---|

| Power flow direction | Unidirectional | Bidirectional |

| Control and monitoring | Limited, mostly manual | Near real-time control |

| Flexibility sources | Almost none | Demand response, EVs, storage, DERs |

| Voltage and congestion control | Network reinforcement | DERs, storage, reactive power control |

| Investment driver | Infrastructure upgrades | Flexibility + selective reinforcement |

| System role | Passive | Active system participant |

| Planning | Horizon | Aim | Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Term | 1 to 4 years | Expansion planning for immediate or near-term needs, operational improvements. | Conductor sizes, number of feeders, transformer sizes, and locations. |

| Long-Term | 5 to 20 years | Developing infrastructure to meet future demand, aligning with medium-term goals. | System design standards, primary and secondary voltage classes, feeder configurations. |

| Horizon-Year | 20+ years | Strategic, cost-effective infrastructure design to meet long-term consumer needs. | Comprehensive system design, integrating primary and secondary systems. |

| Category | Objective and Description |

|---|---|

| Economic [7,10,11,12] |

|

| Technical [13,14,15,16] |

|

| Environmental [17,18,19,20] |

|

| Decision Variable | Description |

|---|---|

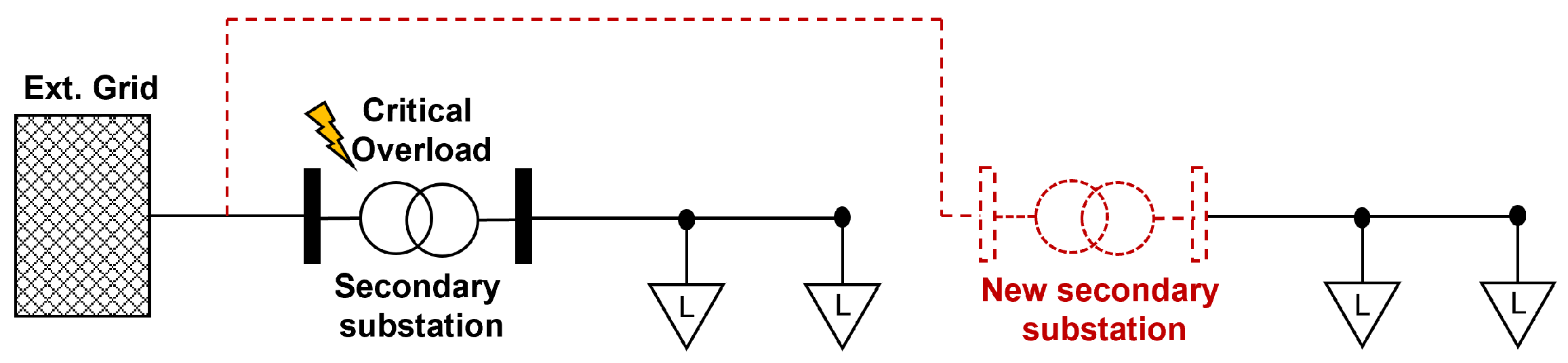

| Locations and sizes of new substations | Optimizes voltage regulation and load distribution. Supports network expansion and enhances reliability [21,22,23,24,25]. |

| Upgrade of existing substations for reinforcement | Upgrades ensure the capacity to handle increased demand [23,24,25]. |

| Locations and sizes of new feeders | Expands network capacity and reduces the load on existing feeders. Placement optimized using GIS and power flow analyses [23,24,25,26]. |

| Upgrade of existing feeders for reinforcement | Prevents overloads as demand grows. Employs sensitivity analysis and cost-benefit analysis [24]. |

| Locations of reserve feeders and interconnection switches | Provides flexibility for re-routing power during contingencies. Enhances system reliability and resilience [24]. |

| Locations, sizes, and types of renewable distributed generations | Manages demand fluctuations, providing operational flexibility. Placement optimized for stability and efficiency [23,24]. |

| Locations of new EV charging stations | Strategically placed to prevent local network strain. Supports efficient load balancing with increasing EV adoption [27]. |

| Locations, sizes, and types of ESS | Stabilizes load by storing excess energy. Assists in peak shaving and integration of renewable sources. |

| Locations and sizes of voltage control devices | Maintains stable voltage levels in high DER penetration areas. Essential for voltage stability and regulatory compliance. |

| Flexible Source | Impact | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PV Generation | Voltage rise, reverse power flow under low load | Hosting capacity analysis, inverter-based voltage regulation, local control schemes |

| ESS | Peak shaving, arbitrage, reliability enhancement | Optimal siting/sizing, cost-benefit trade-offs, multi-period dispatch |

| EVCS and V2G | Rapid changes in load demand, potential feeder overload | EVCS siting, flexible charging strategies (time-of-use, V2G) |

| Demand Response | Demand shifting, improved load factor | Tariff and load control schemes |

| Category | Constraints |

|---|---|

| Technical | Power balance equations, voltage magnitude, voltage angle, feeder/substation thermal limits, Battery state of charge limits, PV generation power, N-1 criterion. |

| Non-Technical | Location of assets, capacity of assets, quantity of assets per location. |

| Time and Investment | Capital expenditure, operational expenditure, static and dynamic states. |

| Variable Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Binary | Installation of new secondary substations, upgrade of secondary substation capacity, installation of new ESS, installation of PV systems, installation of controlled EVCS, installation of parallel feeders, upgrade of feeder capacity, among others. |

| Continuous | Battery state of charge, substation power injection, voltage magnitude, voltage angle, branch power flow, generation power injection, load shedding, among others. |

| Category | Methods |

|---|---|

| Probabilistic |

1. Stochastic optimization 2. Robust optimization |

| Possibilistic | 1. Possibilistic methods |

| Hybrid probabilistic-possibilistic | 1. Combined probabilistic and possibilistic approaches |

| Information Gap Decision Theory | 1. Decision-making under deep uncertainty |

| Monte Carlo simulations | 1. Sequential: Simulation method with iterative updates 2. Pseudo-sequential: Hybrid approach between sequential and non-sequential 3. Non-sequential: Independent Monte Carlo runs without sequential updates |

| Analytical | 1. Fuzzy-Monte Carlo 2. Fuzzy-scenario-based methods |

| Approximation of PDF | 1. Convolution 2. Cumulants 3. Taylor Series Expansion 4. First-Order Second-Moment 5. Point Estimate Method 6. Unscented Transformation |

| Formulation | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Programming |

|

|

| Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

|

|

| Mixed-Integer Non-Linear Programming |

|

|

| Convex Relaxations |

|

|

| Metaheuristic Methods |

|

|

| Category | Type of Generative AI Model | Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAN-based models | cGAN, WGAN-GP, CycleGAN, StyleGAN, ExGAN, BiGAN | Scenario generation (renewable, load, EV), data augmentation, cyber-resilience, fault diagnosis. Synthetic time-series for PV, wind, load, and EVs to support stochastic and long-term planning | [63,64,65,66,67,68] |

| Diffusion-based models | DiffCharge, DiffLoad, ExDiffusion, Conditional Diffusion | EV/load scenario generation, uncertainty quantification, extreme event modeling, resilience analysis. Stress-testing, extreme event simulation, reliability planning. | [69,70,71,72,73] |

| VAE-based models | -VAE, Conditional VAE, BiVAE | Probabilistic forecasting, scenario synthesis, energy efficiency planning, voltage stability assessment. Probabilistic load/price forecasting and OPF optimization under uncertainty. | [74,75,76,77] |

| Flow-based models | RealNVP, Glow, Normalizing Flow | Renewable and load scenario generation, uncertainty modeling, probabilistic OPF, expansion planning. | [78,79,80,81] |

| Transformer-based models | GPT, LLaMA, eGridGPT, CPGA-BOT, PowerPulse | Planning assistants, data mining, simulation automation, energy management, human-in-the-loop decision support. Decision support via Large Language Models (LLMs), planning chatbots, automated data mining, and simulation scripting. | [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Saldaña-González, A.E.; Aragüés-Peñalba, M.; Gadelha, V.; Sumper, A. Review of Active Distribution Network Planning: Elements in Optimization Models and Generative AI Applications. Energies 2026, 19, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010116

Saldaña-González AE, Aragüés-Peñalba M, Gadelha V, Sumper A. Review of Active Distribution Network Planning: Elements in Optimization Models and Generative AI Applications. Energies. 2026; 19(1):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010116

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaldaña-González, Antonio E., Mònica Aragüés-Peñalba, Vinicius Gadelha, and Andreas Sumper. 2026. "Review of Active Distribution Network Planning: Elements in Optimization Models and Generative AI Applications" Energies 19, no. 1: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010116

APA StyleSaldaña-González, A. E., Aragüés-Peñalba, M., Gadelha, V., & Sumper, A. (2026). Review of Active Distribution Network Planning: Elements in Optimization Models and Generative AI Applications. Energies, 19(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010116