Evaluation of HFE-73DE/Ethyl Acetate Mixtures for Use in Minichannel Heat Exchangers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- experimentally characterising the key thermophysical properties of HFE-73DE/ethyl acetate mixtures over a composition range relevant for thermal-engineering applications;

- analysing single-phase laminar heat transfer in a heated minichannel module for a selected base fluid (pure HFE-73DE) under representative operating conditions;

- developing and validating a three-dimensional CFD model that reproduces the experimentally observed thermal and hydraulic behaviours, including conjugate heat transfer and temperature-dependent liquid properties.

2. Selected Binary Mixtures and Property Analysis

3. Experimental Setup

3.1. Experimental Setup Overview

3.2. Minichannel Module

3.3. Experimental Methodology

3.4. Measurement Uncertainty

3.5. Selected Experimental Series

4. Numerical Calculations

4.1. General Information

4.2. CAD Model of the Test Module

4.3. Simcenter STAR-CCM+ Software

4.4. Governing Equations and Material Properties

- the fluid flow in the minichannel is incompressible, with a constant mass flow rate;

- temperature-dependent thermophysical properties of the working fluid are applied based on the experimental data obtained in Section 2;

- the material properties of the solid parts of the test module (copper block, glass cover, insulation) are independent of temperature;

- heat losses from the test module to the surroundings are taken into account through an effective convective boundary condition at the external surfaces.

4.5. Boundary Conditions

4.6. Mesh Independence Study

- = 1.39,

- average observed order s = 0.425,

- average relative error ,

- average .

- = 1.31,

- average observed order s is the same as for the fine–medium pair,

- average relative error ,

- average .

4.7. Simulation Procedure

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. General Information

5.2. Heat Transfer Coefficient Distributions for HFE-73DE/Ethyl Acetate Mixtures

5.3. Flow Velocity and Fluid-Core Temperature at Mid-Depth for HFE-73DE/Ethyl Acetate Mixtures

5.4. Heat Transfer Coefficient Distributions for HFE-73DE

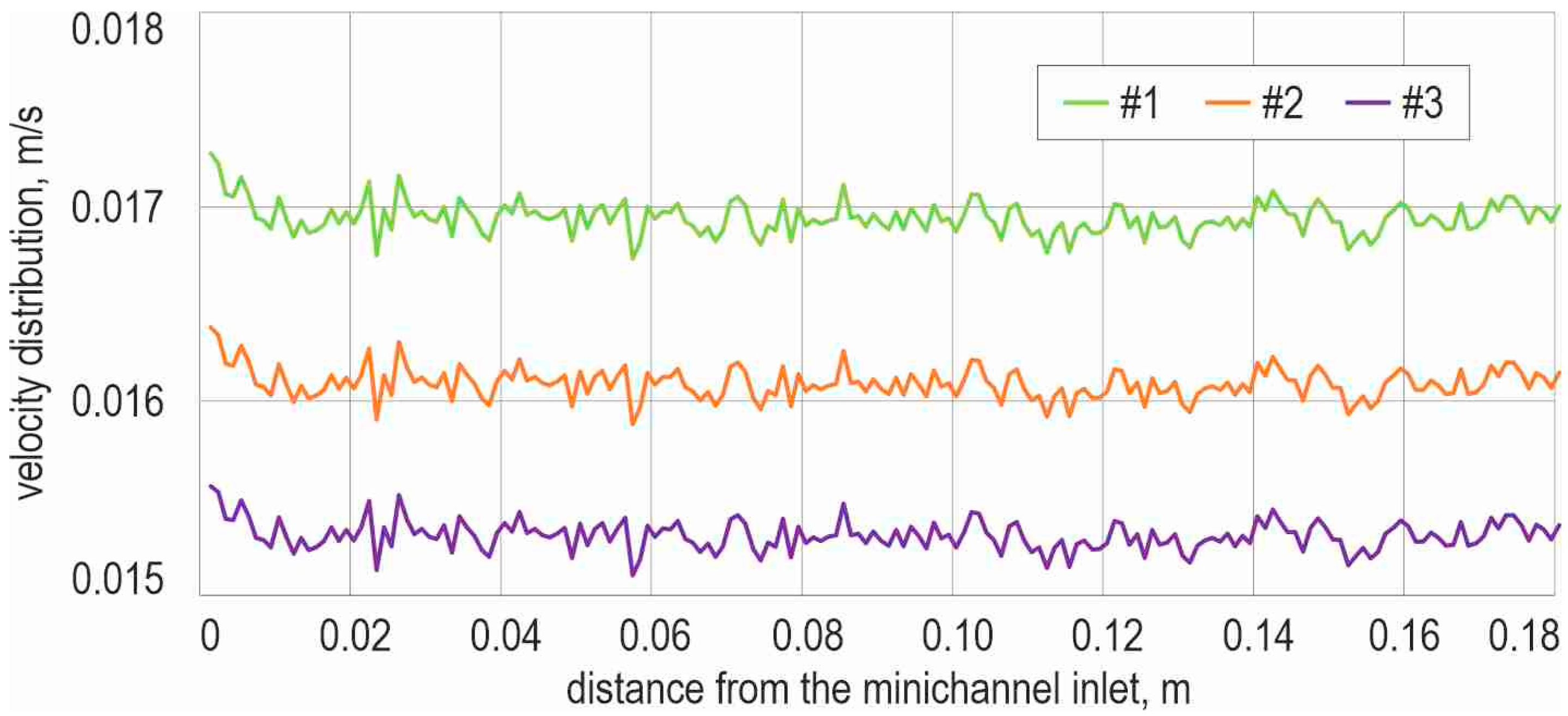

5.5. Flow Velocity and Fluid-Core Temperature at Mid-Depth for HFE-73DE

6. Validation and Verification of the Results

6.1. General Remarks

6.2. Validation of the Numerical Simulations

6.3. Verification of the Results with a Selected Correlation from the Literature

7. Conclusions

- The thermophysical properties of HFE-73DE/ethyl acetate mixtures exhibit a strongly nonlinear dependence on composition. Density increases almost monotonically and kinematic viscosity decreases with increasing HFE-73DE content, whereas thermal conductivity increases by more than a factor of two between the 10/90 and 75/25 mixtures. The specific heat shows a non-monotonic variation, with a minimum near 25/75 and the highest value for the 75/25 mixture, indicating deviations from ideal mixing. These trends directly affect both the hydraulic and thermal performance of the mixtures in minichannel flow and confirm that, for such non-ideal systems, directly measured temperature-dependent cp(T) and k(T) data are needed instead of simple mixing rules.

- Under constant heat-flux conditions, the local heat transfer coefficient in the heated minichannel decreases gradually with distance from the inlet, reflecting the development of the thermal boundary layer and the evolving wall-to-bulk temperature difference. Mixture composition has a pronounced influence on the magnitude of the heat transfer coefficient and on the axial temperature rise in the fluid, with HFE-richer mixtures providing higher heat transfer coefficients and lower fluid-temperature increases.

- A three-dimensional CFD model developed in Simcenter STAR-CCM+, incorporating conjugate heat transfer in the solid parts and temperature-dependent liquid properties, reproduces the experimentally observed behaviour with good accuracy. A mesh-independence study based on the Grid Convergence Index (GCI) confirmed that discretisation errors are small, and comparisons with representative experimental cases show that the predicted temperatures differ from the measurements by less than 0.5% on average. Additional verification against the fully developed laminar Shah and London solution for a 1 × 4 mm rectangular duct demonstrates that the CFD-based mean Nusselt numbers are about 35–42% higher than the theoretical value, highlighting the impact of asymmetric heating and conjugate heat conduction on the effective single-phase heat transfer coefficient.

- Intermediate mixtures with 50/50 and 75/25 mass % HFE-73DE/ethyl acetate provide a favourable compromise between heat-transfer performance and pressure drop. Under the conditions studied, these mixtures yield significantly higher local heat transfer coefficients and smaller fluid-temperature increases along the minichannel than the 10/90 mixture, while avoiding the very low viscosities that could occur in even more HFE-rich compositions.

- The validated CFD framework offers a reliable tool for analysing and optimising minichannel heat exchangers operating with HFE-73DE/ethyl acetate mixtures and, more broadly, other HFE-based binary systems. It can be used to evaluate alternative channel geometries, operating conditions and mixture compositions, and thereby support the tailored design of dielectric cooling systems for power electronics and other compact thermal-management applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| minichannel cross-sectional area, m2 | |

| a,b | channel side lengths, m |

| cp | specific heat, J/(kg·K) |

| Dh | hydraulic diameter, m |

| total energy per unit mass, J/kg | |

| relative error between two successive grids, | |

| body force per unit volume, N/m3 | |

| GCI | Grid Convergence Index, |

| I | identity tensor, |

| thermal conductivity, W/(m·K) | |

| Nu | Nusselt number, |

| outward normal vector, | |

| p | pressure, Pa |

| grid refinement factor, | |

| s | observed order of accuracy, |

| heat flux vector, W/m2 | |

| heating power, W | |

| Pr | Prandtl number, |

| GCI consistency ratio, | |

| Re | Reynolds number, |

| energy source term per unit volume, W/m3 | |

| T | temperature, K |

| shear stress tensor, N/m2 | |

| volume, m3 | |

| velocity vector, m/s | |

| volumetric flow rate, m3/s | |

| ∇ | nabla operator, |

| Greek symbols | |

| α | aspect ratio, defined as the ratio of the smaller side a to the larger side b of the channel |

| average relative difference, % | |

| ρ | density, kg/m3 |

| μ | dynamic viscosity, Pa·s |

| boundary of computational domain, | |

| computational domain, | |

| Subscripts | |

| CFD | from CFD calculations, based on experimental data |

| Cu | copper block |

| exp | from an experiment |

| external | |

| f | fluid |

| g | glass |

| H | heater |

| s | solid |

| sat | saturation |

| T | temperature |

| theor | from a theoretical correlation |

| ambient temperature | |

| Abbreviations | |

| ASME | American Society of Mechanical Engineers |

| CFD | computational fluid dynamics |

| EA | ethyl acetate |

| FVM | finite volume method |

| HFE | hydrofluoroether |

| HTC | heat transfer coefficient |

References

- Munoz-Rujas, N.; Aguilar, F.; Garcia-Alonso, J.M.; Montero, E.A. Thermodynamics of binary mixtures 1-ethoxy-1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,4-nonafluorobutane (HFE7200) + 2-propanol: High pressure density, speed of sound and derivative properties. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2019, 131, 630–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rujas, M.; Bazile, J.P.; Aguilar, F.; Galliero, G.; Montero, E.; Daridon, J.-L. Speed of sound, density and derivative properties of binary mixtures HFE-7500 + diisopropyl ether under high pressure. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2019, 128, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminian, A.; Celný, D.; Mickoleit, E.; Jäger, A.; Vinš, V. Ideal Gas Heat Capacity and Critical Properties of HFE-Type Engineering Fluids: Ab Initio Predictions of Cp, Modelling of Phase Behaviour and Thermodynamic Properties Using Peng–Robinson and Volume-Translated Peng–Robinson Equations of State. Int. J. Thermophys. 2022, 43, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urata, S.; Takada, A.; Murata, J.; Hiaki, T.; Sekiya, A. Prediction of vapour–liquid equilibrium for binary systems containing HFEs by using artificial neural network. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2002, 199, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Wu, Q.; Wang, R. Heat transfer performance of pulsating heat pipe with zeotropic immiscible binary mixtures. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 137, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, H.; Karashima, S.; Takigawa, T.; Murakami, S. Excess molar enthalpies and volumes of binary mixtures of two hydrofluoroethers with hexane, benzene, ethanol, 1-propanol, or 2-butanone at T = 298.15 K. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2003, 35, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, M.S.; Kotb, A.; Liu, L.; Wang, S. The prediction of binary zeotropic mixtures in-tube flow condensation A generalized non-equilibrium heat transfer model. Energy Convers. Manag. 2026, 347, 120562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Pan, Y.; Ren, J.; Li, Q. Exploring structure-property relationships of critical temperatures for binary refrigerant mixtures via group contribution and machine learning. DeCarbon 2025, 9, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Rani, M.; Lee, Y.; Maken, S. Thermophysical properties of binary mixtures of diethyl ether as oxygenate with cyclohexane and aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 387, 122663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-Y.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Lin, L.-C. Transport properties of Alcohol/Water Mixtures: Evaluation of molecular potentials. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 433, 127870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Lopez, A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Mejuto, J.C. Viscosity mixing rules and machine learning-based models for predicting the viscosity of liquid binary mixtures of aliphatic alkanes. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 437, 128401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, R.; Okutucu-Özyurt, T. Numerical simulation of flow boiling from an artificial cavity in a microchannel. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 97, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priy, A.; Ahmad, I.; Khan, M.K.; Pathak, M. Bubble interaction and heat transfer characteristics of microchannel flow boiling with single and multiple cavities. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 2024, 16, 061010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Yu, X.; Lu, Z.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Luo, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Numerical simulation study on stratified flow boiling in rectangular mini-channels. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2026, 194, 105447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3MTM NovecTM 73DE Engineered Fluid, Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/1216212O/3m-novec-73de-engineered-fluid.pdf?&fn=3M-Novec-73DE-Engineered-Fluid-TDS.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ethyl Acetate, Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/PL/en/sds/aldrich/l092004?userType=anonymous (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- ASTM D1250; Standard Guide for Use of the Petroleum Measurement Tables. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- EN ISO 3104:2020; Petroleum Products—Transparent and Opaque Liquids—Determination of Kinematic Viscosity and Calculation of Dynamic Viscosity. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- ASTM D86; Standard Test Method for Distillation of Petroleum Products at Atmospheric Pressure. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- Makomaski, G.; Ciesińska, W.; Zieliński, J. Thermal properties of pitch-polymer compositions and derived activated carbons. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2012, 109, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecchi, M.; Goldfarb, J.L.; Baratieri, M. Hydrothermal carbonization enthalpy using differential scanning calorimetry: Assessing the accuracy of the exhaust sample method. Thermochim. Acta 2022, 718, 179388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.M.M.; El Far, B.; Nayfeh, Y.; Shin, D. Investigation of time–temperature dependency of heat capacity enhancement in molten salt nanofluids. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 22972–22982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, C.J.; Jang, S.P.; Choi, S. U.S. A Review of Thermal Conductivity Data, Mechanisms and Models for Nanofluids. Int. J. Micro-Nano Scale Transp. 2010, 1, 269–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrak, K.; Wiśniewski, T.S. A review of models for effective thermal conductivity of composite materials. J. Power Technol. 2015, 95, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, G.; Chopkar, M.; Manna, I.; Das, P.K. Techniques for measuring the thermal conductivity of nanofluids: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 1913–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska, B.; Hożejowska, S.; Grabowski, M.; Poniewski, M.E. Numerical Analysis of the Boiling Heat Transfer Coefficient in the Flow in Mini-Channels. Acta Mech. Autom. 2023, 17, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, M.; Poniewski, M.E.; Hożejowska, S.; Pawińska, A. Numerical Simulation of the Temperature Fields in a Single-Phase Flow in an Asymmetrically Heated Minichannel. J. Eng. Phys. Thermophys. 2020, 93, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology. JCGM 100: 2008 Evaluation of Measurement Data—Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement. Meas. Jt. Comm. Guid. Metrol. 2008, 1, 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewska, B.; Piasecka, M.; Dadas, N.; Strąk, K. Fluid flow and heat transfer characteristics in minichannels—CFD calculations in Simcenter STAR-CCM+. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 61, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecka, M.; Piasecki, A.; Dadas, N. Experimental Study and CFD Modeling of Fluid Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics in a Mini-channel Heat Sink Using Simcenter STAR-CCM+ Software. Energies 2022, 15, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Fluid Mechanics; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Carslaw, H.S.; Jaeger, J.C. Conduction of Heat in Solids; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/copper-density-specific-heat-thermal-conductivity-vs-temperature-d_2223.html (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Available online: https://www.scientificglass.co.uk/contents/en-uk/d115_Physical_Properties_of_Borosilicate_Glass.html (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Available online: https://www.mohsin-sies.com/sktn3224/notes/Appendix.Incropera%20DeWitt%20-%20Fundamentals%20of%20Heat%20and%20Mass%20Transfer.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Celik, I.B.; Ghia, U.; Roache, P.J.; Freitas, C.J.; Coleman, H.; Raad, P.E. Procedure for estimation and reporting of uncertainty due to discretization in CFD applications. J. Fluids Eng. Trans. ASME 2008, 130, 780011–780014. [Google Scholar]

- Roache, P.J. Perspective: A Method for Uniform Reporting of Grid Refinement Studies. J. Fluids Eng. ASME 1994, 116, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patankar, S.V. Numerical Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow; McGraw-Hill: Washington, DC, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg, H.K.; Malalasekera, W. An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method, 2nd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.K.; London, A.L. Laminar Flow Forced Convection in Ducts: A Source Book for Compact Heat Exchanger Analytical Data; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

| Physical Property | Ethyl Acetate | HFE-73DE |

|---|---|---|

| Density, kg/m3 | 894 | 1520 |

| Kinematic viscosity, mm2/s | 0.463 | 0.403 |

| Thermal conductivity, W/(m·K) | 0.149 | 0.075 |

| Specific heat, J/(kg·K) | 2020 | 1020 |

| Boiling temperature, K | 350.25 | 314.35 |

| Mixture (Mass Fractions) | Density (kg/m3) | Kinematic Viscosity (mm2/s) | Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·K)) | Specific Heat (J/(kg·K)) | Boiling Temperature Tsat (K) Tsat,theor/Tsat,exp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 73DE 10%/EA 90% | 931.0 | 0.5081 | 0.165 | 503.8 | 314.35/348.15 |

| 73DE 25%/EA 75% | 969.0 | 0.5033 | 0.189 | 313.3 | 314.35/342.15 |

| 73DE 50%/EA 50% | 1035.0 | 0.4676 | 0.207 | 444.6 | 314.35/341.15 |

| 73DE 75%/EA 25% | 1169.0 | 0.4218 | 0.344 | 971.5 | 314.35/333.15 |

| Experimental Parameter | Set #1 | Set #2 | Set #3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volumetric flow rate (m3/s) | 5.75 × 10−8 | 5.45 × 10−8 | 5.18 × 10−8 |

| Inlet fluid temperature (K) | 302.74 | 304.62 | 305.76 |

| Outlet fluid temperature (K) | 307.65 | 316.50 | 322.68 |

| Heater section temperature (K) | 312.28; 312.41; 312.35 | 323.44; 323.61; 323.55 | 326.94; 327.04; 326.92 |

| Pressure drop (Pa) | 419.62 | 395.97 | 827.58 |

| Inlet gauge pressure (Pa) | 14,585.0 | 15,660.9 | 15,198.0 |

| Heating power (W) | 3.62 | 15 | 23 |

| Element of the Minichannel Module | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Material parameter | Copper block [33] | Heater [34] | Glass [35] |

| Density [kg/m3] | 8940.0 | 7832.0 | 2500 |

| Specific heat [J/(kg·K)] | 386.0 | 434.0 | 840 |

| Thermal conductivity [W/(m·K)] | 398.0 | 63.9 | 1.4 |

| Set | Re | Pr | (W/(m2·K)) | (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 57.0 | 8.34 | 337.33 | 7.20 |

| #2 | 54.1 | 8.34 | 354.76 | 7.57 |

| #3 | 51.4 | 8.34 | 354.64 | 7.57 |

| Number of Set | #1 | #2 | #3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average relative differences δT [%] | 0.4 | 0.48 | 0.46 |

| Set | [%] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 7.20 | 5.33 | 35 |

| #2 | 7.57 | 5.33 | 42 |

| #3 | 7.57 | 5.33 | 42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Piasecki, A.; Maciejewska, B.; Piasecka, M.; Grabowski, M.; Grabowski, P. Evaluation of HFE-73DE/Ethyl Acetate Mixtures for Use in Minichannel Heat Exchangers. Energies 2026, 19, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010110

Piasecki A, Maciejewska B, Piasecka M, Grabowski M, Grabowski P. Evaluation of HFE-73DE/Ethyl Acetate Mixtures for Use in Minichannel Heat Exchangers. Energies. 2026; 19(1):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010110

Chicago/Turabian StylePiasecki, Artur, Beata Maciejewska, Magdalena Piasecka, Mirosław Grabowski, and Paweł Grabowski. 2026. "Evaluation of HFE-73DE/Ethyl Acetate Mixtures for Use in Minichannel Heat Exchangers" Energies 19, no. 1: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010110

APA StylePiasecki, A., Maciejewska, B., Piasecka, M., Grabowski, M., & Grabowski, P. (2026). Evaluation of HFE-73DE/Ethyl Acetate Mixtures for Use in Minichannel Heat Exchangers. Energies, 19(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010110