1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, the green transition has emerged as a major structural force reshaping European labour markets, influencing employment dynamics and the architecture of required skills [

1,

2]. The expansion of climate policies, ambitious emission reduction targets, and investment shifts toward sustainable sectors have spurred significant transformations in the demand for green skills, the quality of employment, and regional opportunity distribution [

3,

4,

5]. These changes are closely tied to the European energy transition, led by the Green Deal and REPowerEU, which accelerate decarbonization and expand renewable energy systems [

4]. While the transition offers substantial benefits—such as reducing dependence on polluting industries, creating green jobs, and fostering climate neutrality [

6,

7]—it also introduces major challenges: career instability, the pressure to adapt skills rapidly, and increasing social inequalities across countries and regions [

8].

Unlike traditional economic models, sustainability-oriented labour dynamics are highly sensitive to political, technological, and institutional variability [

9]. Factors such as innovation diffusion, digitalization, investment intensity, and professional retraining shape employment levels, job quality, skills distribution, and territorial mobility [

10]. This complexity underlines the need for flexible, cost-effective monitoring tools that capture regional and temporal differences in transition trajectories.

Conventional approaches to monitoring the labour market have relied on centralized reporting, extensive raw data collection, and mostly descriptive analyses. While they have provided rich details about local phenomena, they have involved high infrastructure costs and operational complexity that are difficult to sustain in the long term [

11,

12]. In addition, they have typically relied on pre-established indicators (e.g., a one-off increase in unemployment in a region), which capture only isolated events, without reflecting the spatial and temporal dynamics of the transformations generated by the green transition. In the context of green investments, these limitations are amplified by the need to integrate data on energy infrastructure, green investments, and emissions intensity with employment indicators in order to capture the interdependencies between energy system transformation and labour market dynamics [

13].

The gap between the increasing complexity of labour markets and the limitations of traditional approaches highlights the need for a new analytical architecture, designed to reduce the reliance on large volumes of raw data and improve the detection of structural changes. In this sense, a comparable index across countries and anchored in time and space can provide a solid synthesis and, at the same time, a tool for prioritizing public policy interventions. The development of such a methodology is facilitated by modern digital infrastructures: harmonized European surveys (EU-LFS) [

14], Environmental Goods and Services Sector (EGSS) [

15], occupational platforms such as ESCO [

16], mobility networks (EURES) [

17], administrative databases and tax registers, but also emerging sources such as the aggregation of online job advertisements. Nevertheless, the connection between available resources and comparable readiness indicators is not yet fully formalized, which leaves a methodological gap in differentiated monitoring at the territorial level [

18].

Existing research has made a significant contribution to defining and measuring green jobs, highlighting the importance of skills for the transition, analyzing active employment policies, and studying innovation mechanisms [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Numerous sectoral studies investigate renewable energy (with direct effects on employment, skills, and retraining), sustainable construction, electric mobility, or the circular economy; other works explore professional retraining and adult participation in training or evaluate institutional programmes and national strategies. The example of renewable energy is not only technologically central but also occupational: capacity expansion involves new jobs in installation, operation, and maintenance; retraining for workers in carbon-intensive industries; and regional differences in opportunities, which justifies the use of a comparable index such as the GLMRI.

The systematic link between the variability of the transition—the different intensity of pressures towards decarbonization, the pace of innovation, and the degree of digitalization—and labour market monitoring strategies calibrated to territorial profiles remains insufficiently explored. Not all countries or regions need the same frequency of measurements, the same volume of interventions, or the same policy instruments.

In the absence of an integrative framework that regulates efforts according to an objective indicator of readiness for the green transition, policies risk remaining fragmented and generating limited results. The heterogeneity of the energy transition highlights the need for analytical tools that can calibrate the frequency and intensity of public interventions according to the local pace of decarbonization and occupational reconversion.

A careful analysis of the literature reveals the persistence of a predominantly static and uniform perspective in research dedicated to the readiness of labour markets for the green transition [

23,

24,

25]. Numerous investigations focus on monitoring key indicators in economies with a high share of green sectors but do not differentiate the intensity of public interventions according to the local pace of transformation [

3,

5,

8,

26,

27].

Other authors discuss adaptive training, micro-certification, and lifelong learning mechanisms; however, the connection between these initiatives and the dynamics of the transition—whether regional or temporal—remains insufficiently formalized [

28,

29]. At the same time, cross-national comparisons are still scarce, and studies that integrate a synthetic analytical framework with evolutionary scenarios and a territorial prioritization logic remain isolated exceptions [

1,

22,

30].

The presented research aims to address the identified gaps by developing an adaptive monitoring framework for labour markets’ readiness for the green transition. The approach is based on a territorial classification of countries and, in the medium term, of regions, according to the level of adaptation to the transformation. The central point of the approach is the GLMRI, built to quantify, in a comparable way across countries and regions, the capacity of labour markets to absorb change in relation to economic structure, skills level, infrastructure quality, institutional robustness, and innovative potential. By using the GLMRI, it becomes possible to segment labour markets into three types of readiness: high, moderate, and low.

Each category corresponds to a differentiated monitoring and intervention regime: continuous surveillance and complex active policy packages for areas exposed to rapid transformations or heightened risks, periodic monitoring and calibrated interventions for spaces in an intermediate stage of preparation, and basic surveillance for territories where the transition is already consolidated and the focus is on refining skills and maintaining the quality of employment.

The stated objective is to optimize the allocation of resources for public policies and increase the accuracy of the detection of imbalances without amplifying the volume of processed data. The proposed model favours a governance of the labour market in which statistical data do not remain simple descriptions of the past but become inputs for decision-making in an adaptive process of optimizing interventions. From this perspective, the contribution is not limited to the construction of an analytical tool; an operational logic is also outlined for the design of an intelligent monitoring architecture, in which efficiency and resilience come from the ability to differentiate and anticipate local labour market behaviours in real or near real time.

Methodologically, the construction of the GLMRI is based on five major dimensions: education and skills (share of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) graduates, adult participation in training, digital skills), investment and infrastructure (share of renewable energies in final consumption, public spending on the environment, renewable capacity per capita, infrastructure for electric mobility), policies and institutions (normative frameworks for transition, spending on training and retraining, allocations from European instruments such as Just Transition and Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF)), labour market structure (share of employment in EGSS and dependence on high-emissions-intensive industries) and innovation and competitiveness (green patents, R&D spending, intensity of exports of environmental goods). Indicators are normalized on the interval [0, 1] by min–max transformation, with inversion for variables with an unfavourable meaning (e.g., share of employment in polluting industries). Aggregation by dimension and composite score is initially performed with equal weights, followed by robustness tests based on techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP).

Panel data econometric models with fixed and random effects are employed to examine how external energy-system characteristics, institutional capacity, and macro-structural conditions shape labour-market readiness for the green transition, as captured by the GLMRI. In order to avoid any mechanical overlap between index construction and econometric analysis, the regression framework relies exclusively on explanatory variables that are external to the GLMRI architecture. Control variables—GDP per capita, unemployment rate, and demographic indicators—are included to account for general macroeconomic conditions.

For projections up to 2040, machine learning algorithms that serve different types of data regularities are combined. Random Forest (RF) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithms capture nonlinear relationships and complex interactions among the dimensions and control variables, whereas Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural networks exploit temporal dependencies within the GLMRI time series and dimension scores. Validation is performed through walk-forward procedures, with time windows that avoid information leakage. The quality of predictions is evaluated using standard performance metrics, including the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). Model interpretability is ensured through feature importance analysis and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), which provide valuable insights for dialogue with decision-makers.

The overarching objective of the study is twofold: to enable synthetic measurement and to provide policy guidance. On the one hand, the GLMRI offers a concise representation of a complex and multidimensional reality; on the other hand, its zonal segmentation and predictive scenarios help identify priorities, trajectories, and optimal combinations of policy interventions. Without imposing additional pressure on statistical systems, the framework allows for the early detection of emerging imbalances—such as skill deficits, risks of structural unemployment, or institutional bottlenecks—and facilitates the calibration of targeted action packages, including results-oriented training programmes, smart investment incentives, labour mobility support, and social cohesion measures.

Based on the framework presented, the paper aims to answer four research questions:

RQ1. Can a robust composite index be defined that quantitatively reflects the readiness of labour markets for the green transition in the European Union, with comparability across countries and extensibility at the regional level?

RQ2. Can a segmentation into differentiated readiness areas be achieved based on the index, supporting the efficient allocation of resources and the selection of intervention types?

RQ3. What are the types of policies and combinations of instruments most appropriate for each readiness class, and under what conditions can they produce tangible effects on employment and job quality?

RQ4. What is the impact of implementing the model on the efficiency and accuracy of a system for labour market surveillance, with a focus on the ability to anticipate imbalances up to the horizon of 2040?

The proposed answers are based on a rigorous methodological protocol: motivated selection of indicators and countries, transparent normalization, aggregation with robustness tests, econometric estimates with attention to diagnosis and validations through machine learning techniques. In addition, the scenario architecture gives practical utility to the results, facilitating dialogue with public administrations, social partners, and the private sector. The integration of econometric interpretability with the predictive capabilities of Machine Learning (ML) algorithms enables the framework to deliver both explanatory and forecasting power, mitigating the constraints of single-method approaches.

The normative dimension of the approach is worth emphasizing. Modelling readiness for the green transition does not only aim to confirm already known differences but also to build a governance tool that connects measurement with decision-making. By including skills, investments, institutions, employment structure, and innovation in a single score, the GLMRI allows for an integrated discussion about what needs to be done, where the potential impact is greater, and when changes in pace occur. Segmentation by class helps to prioritize resources and time interventions: some territories will primarily benefit from reconversion and training programmes, others from investment incentives or strengthening administrative capacity, and a third group will mainly need to maintain quality and strengthen innovation.

As a whole, the proposed approach opens a new direction for the practice of labour market monitoring in the context of the green transition, promoting flexibility, localization, and efficiency instead of the uniformity and rigidity of classic systems. Aligning sustainability considerations with the monitoring architecture means integrating environmental responsibility into the very logic of analytical tools, rather than treating it as an external objective. Through this lens, the preparation of labour markets becomes a matter of intelligent institutional design, well-used data, and informed decision-making, capable of transforming the transition into a vector of inclusive and competitive development at the European level.

Importantly, this study does not aim to causally identify independent sources of variation in labour-market readiness. Instead, the econometric analysis complements the composite index by linking observed readiness outcomes to external energy-system constraints, institutional quality, and macro-structural conditions. The added value of the framework lies in showing how labour-market readiness—measured through the GLMRI—is shaped by broader systemic factors and how this readiness conditions the transmission of energy-transition pressures into differentiated employment trajectories and policy needs.

2. Theoretical Framework

The concept of green jobs has gained increasing prominence in economic and social sciences due to growing concerns over sustainable development and the energy transition [

11,

31]. The International Labour Organization (ILO) proposes one of the most widely used definitions, describing green jobs as those activities that contribute to the conservation or restoration of the environment, either by reducing the consumption of energy and raw materials, or by limiting emissions and pollution, or by protecting ecosystems and biodiversity [

32]. In the context of the energy transition, green jobs become a key indicator of the degree of economic decarbonization and the capacity of markets to absorb clean technologies.

The European Union has adopted a broader perspective, including not only occupations in green sectors in the strict sense (renewable energy (solar, wind, and green hydrogen), recycling, and organic agriculture), but also those traditional professions that integrate sustainable practices [

26,

31,

33]. Thus, a construction engineer who applies energy efficiency standards or an IT specialist who develops solutions for intelligent resource management can be classified as having a green job.

In comparison, academic literature emphasizes the difficulty of clearly delineating this occupational category, as the boundary between green and traditional jobs is often fluid. This boundary evolves in response to technological progress and regulatory developments, particularly in sectors like renewable energy, where occupational profiles shift along with the diffusion of new technologies [

6,

10,

34].

Complementing the debate on occupational definitions, the concept of readiness has gained traction in economics and the social sciences. Generally, readiness refers to a system’s capacity to respond effectively to major structural transformations. In the context of the green transition, labour market readiness indicates the ability of the workforce, institutions, and infrastructures to absorb changes induced by climate policies, clean technologies, and new production models—without generating significant social dislocation [

11,

35].

Empirical research highlights that labour market readiness is far from uniform. It depends on a complex interplay of factors—including human capital quality, institutional effectiveness, investment levels, and national economic structures [

13,

23,

36]. Within the European green transition, readiness reflects not only the adaptability of the workforce but also the alignment between energy, employment, and education policies.

A closely related concept to readiness is that of green competences, which designates the set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to support sustainable development in various economic sectors. European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP) defines green competences not only as technical skills (e.g., operating renewable energy technologies) but also as transversal skills, such as critical thinking, complex problem solving, innovation capacity, and resource efficiency orientation. In the recent literature, green competences are seen as a “common language” across sectors, as they enable workforce mobility and facilitate professional retraining [

37].

Conversely, the debate on green competences highlights a tension between the high demand from employers and the limited supply provided by education and training systems. The Eurostat report (2022) shows that only a third of university programmes in EU countries include sustainability components, and adult participation in continuing training courses with a focus on the green transition remains below 15% in most Eastern countries [

38]. This discrepancy confirms that readiness is not only a matter of financial resources or infrastructure, but also of adapting education and training systems.

As a result, the specialized literature has emphasized three key conceptual domains—green jobs, readiness, and green skills—which together provide the theoretical framework necessary to understand the green transition of the labour market. Studies on the role of human capital in the green transition have consistently highlighted the importance of vocational training and education oriented towards STEM and digital skills [

8,

31,

39]. The 2020 CEDEFOP report shows that over 80% of companies in the European Union report difficulties in recruiting workers with the skills necessary to implement clean technologies [

40]. Comparative analyses highlight major gaps: in Sweden, Denmark, or Germany, adult participation in continuous training programmes exceeds 30%, while in Romania, Greece, or Poland, it remains below 10%.

The literature also confirms that education systems are not synchronized with the pace of the transition. Studies by Lee et al. [

41] show that the integration of green skills into university curricula is often partial and uneven, leaving graduates insufficiently prepared for emerging sectors. On the other hand, Eurofound reports show that when dual learning programmes are in place, supported by public–private partnerships, the uptake of green jobs increases significantly [

42].

Research shows that the success of the transition depends not only on economic resources but also on the quality of institutions and the coherence of public policies. Eurofound (2021) [

42] highlights that countries with strong governance implement reconversion programmes more efficiently and make better use of European funds. Germany, France, and Sweden are often presented as positive examples, where national climate strategies are correlated with active employment policies [

42].

In contrast, the literature draws attention to the fact that the lack of social dialogue reduces the effectiveness of policies: in countries where trade unions and employer organizations were involved in the development of strategies, the transition had a less negative social impact [

43]. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [

44] and European Patent Office (EPO) [

45] analyses show that the number of green patents has been steadily increasing in Germany, France, and Sweden, reflecting strong innovation ecosystems. Disparities also explain why the implementation of the energy transition requires differentiated just transition policies and governance adapted to the regional context.

It follows a critical review of the literature, which reveals that, despite the considerable volume of research dedicated to the green transition and labour markets, there are still a number of methodological and conceptual gaps that limit the ability of the academic community and policymakers to understand and manage the ongoing transformations [

33].

First, the existing body of research exhibits a high degree of fragmentation, with most studies concentrating on discrete components of the green transition—such as education, investment, or innovation—rather than adopting a comprehensive analytical lens [

7,

8,

19]. This compartmentalized approach hinders both comparability across contexts and the development of an integrated understanding of national labour market readiness. Moreover, fragmentation extends to the level of analysis, as the literature is often confined either to sectoral case studies or national assessments, while systematic cross-country comparisons remain infrequent and methodologically inconsistent [

10,

24].

Second, there is a lack of an integrated composite index that brings together education, investment, policy, labour market structure, and innovation. Although there are global indices for competitiveness, innovation, or education, none directly capture the readiness of the labour market for the green transition [

30]. The absence of such a tool makes it difficult to assess relative performance, prioritize investments, and guide policy design.

Third, comparative multi-country analyses remain scarce. Most research focuses on national case studies or bilateral comparisons, without covering the full diversity of the European Union [

7,

31,

37]. The differences between Western and Eastern Europe and between North and South are discussed at a theoretical level but rarely quantified through a common methodology. This limitation reduces the Union’s capacity to design cohesion policies and calibrate interventions according to regional realities.

Fourth, few studies adopt a forward-looking, predictive perspective focusing on the current situation or on linear short-term trends [

6,

12]. In a structural transition of the magnitude of the green transition, medium- and long-term forecasts are indispensable, but studies using robust forecasting methods are rare. Even when they do appear, they are based on simple extrapolations, without integrating complex econometric models or machine learning algorithms capable of capturing nonlinear relationships and alternative scenarios.

Finally, the link between diagnosis and policy design remains weak, but the connection between these findings and public policy instruments is often weak or implicit [

11,

18]. There are still no validated models showing, for example, which types of interventions are most effective for low-skilled countries or how educational programmes should be calibrated according to the structural profile of the economy.

A recent and highly relevant contribution to this field is the European Commission’s 2025 report titled Estimating Labour Market Transitions and Skills Investment Needs of the Green Transition—A New Approach [

39]. The report presents a sophisticated sectoral modelling framework, using input–output tables and occupation-specific data to estimate how green transitions affect labour market flows and to project skills investment needs across EU Member States.

While this methodology provides valuable insight into occupational shifts and sectoral dynamics, it does not offer a synthetic readiness metric that enables cross-country comparison or long-term policy calibration. Its projections are largely static, focused on sector-specific transformations, and do not integrate broader institutional, innovation, and governance dimensions that influence the pace and inclusiveness of the transition.

In addition, several recent reports published by the European Commission and affiliated agencies highlight the growing policy relevance of labour market readiness for the green transition. The ESDE Report stresses the need for monitoring tools specifically designed to detect cross-country and regional disparities in green preparedness. Similarly, the Just Transition Country Plans emphasize the pressing necessity of accelerating skills development in structurally vulnerable regions that remain strongly dependent on carbon-intensive activities.

CEDEFOP’s Green Deal Skills Forecast and its series of policy briefings (2021–2023) further emphasize the widening gap between required and available green competences. These institutional reports confirm that while sectoral and regional data exist, there is no integrated composite index to assess labour market readiness across the EU in a comparative and dynamic way. The GLMRI directly addresses this gap by providing a synthetic and forward-looking framework grounded in both theory and policy needs.

To provide a clearer articulation of the GLMRI’s novelty and to address the reviewer’s request for explicit differentiation,

Table 1 presents a comparative overview of the main indicators and monitoring frameworks used in the literature and by European institutions. The table highlights their conceptual scope, methodological focus, limitations, and the specific added value introduced by the GLMRI.

Building on this comparison, the GLMRI developed in this study provides an integrated, multidimensional framework that captures not only education and skills but also investment levels, policy robustness, labour market structure, and innovation capacity. In addition to offering a comparable score across countries, the GLMRI supports dynamic forecasting through the integration of econometric models and machine learning algorithms, enabling scenario-based projections up to 2040.

This dual focus—diagnostic and predictive—represents a methodological advancement over existing tools. Rather than replacing sectoral estimates such as those in the EC report, the GLMRI complements them by providing a systemic, country-level lens for readiness assessment, allowing policymakers to prioritize interventions, allocate resources more efficiently, and track progress over time.

The construction of the GLMRI is based on five dimensions considered fundamental in the specialized literature and validated by international reports: education and skills, investment and infrastructure, policies and institutions, labour market structure, and innovation and competitiveness. The choice of these pillars is not arbitrary but the result of a critical analysis of the way in which the green transition has been approached in previous research and in European strategic documents.

Each component reflects a basic condition for absorbing change and for transforming the theoretical potential of transition into a tangible social and economic process. Together, they constitute an integrative framework that allows for comparisons across countries and, more importantly, provides a basis for prospective scenarios and differentiated policies. The proposed approach is particularly relevant for the analysis of labour markets in the context of the European energy transition, highlighting the interdependencies between energy, innovation, and employment policies in the process of economic transformation.

The originality of the study derives from the integration of theoretical and operational dimensions: it combines a rigorous academic analysis with a practical purpose, providing a comparative, prospective and policy-oriented tool. While previous research has described either education, investment, or innovation, the GLMRI brings together all these components in a common architecture, tested on a set of representative countries and projected into the future through robust scenarios.

Positioning itself at the intersection of literature and practice, the study contributes to the consolidation of a new research direction: assessing the readiness of labour markets for the green transition through synthetic, comparable and predictive tools. This direction responds not only to academic needs for conceptualization and measurement, but also to the requirements of the European Union to have tools to substantiate evidence-based policies.

3. Research Model

3.1. Methodology for Building and Validating the GLMRI

The complexity of the phenomenon creates the need for a synthetic tool that captures the degree of readiness of labour markets for the green transition. Unlike previous economic transformations—such as classical industrialization or digitalization—the green transition simultaneously involves the restructuring of human capital, the reorientation of investment flows, institutional reforms, structural changes in employment, and the accelerated development of innovation. Therefore, the GLMRI is designed as a multidimensional composite index, capable of integrating various perspectives into a single, comparable, and interpretable score. The full list of indicators—along with definitions, units of measurement, data sources, and time coverage—is provided in

Appendix A to ensure transparency and reproducibility. These indicators are used exclusively for the construction of the GLMRI composite index and do not enter the econometric specification.

The construction of the GLMRI starts from two methodological premises. The first is that each dimension of the green transition contributes independently but also complementarily to the degree of readiness of the labour market. For example, investments without adequate human capital produce imbalances, and innovation without a solid institutional framework does not generate sustainable results. The second premise is that the performance of an economy cannot be judged solely by absolute values (GDP, R&D spending, number of STEM graduates) but must be calibrated relative to the performance of other countries and to dynamics over time. GLMRI responds to these needs through normalization, aggregation, and longitudinal comparability.

An important step in constructing the index is the transformation of all variables onto a common scale. The indicators come from different sources and are expressed in heterogeneous units—percentages, monetary values, number of patents, and binary values (for the existence of a policy). To avoid the dominance of the final score by indicators with large absolute values, the min–max normalization method is used, which rescales each value in the interval [0, 1]. The formula used is:

where

is the value of indicator

j for country

i at time

t, but

and

are the extreme values of the indicator over the entire period and over the entire sample of countries.

For variables with negative significance, such as the share of employment in polluting sectors, the inverse transformation is applied:

so that high scores always indicate better performance. Through this convention, the interpretation becomes unified: regardless of the nature of the variable, higher values signal higher readiness.

Normalization by the min–max method also has the advantage of maintaining the relative order between countries and years, which facilitates comparative analysis and tracking evolution over time. Despite that, we also recognize a limitation: the method’s sensitivity to extreme values. To counteract this effect, the data are subjected to a process of winsorization at the 1st and 99th percentiles, reducing the influence of outliers.

After normalization, the indicators are grouped into the five fundamental dimensions. Each dimension has the role of reflecting a pillar of readiness: education and skills (share of STEM graduates, adult participation in training, digital skills), investment and infrastructure (share of renewable energies in final consumption, public spending on the environment, renewable capacity per capita, infrastructure for electric mobility), policies and institutions (normative frameworks for transition, spending on training and retraining, allocations from European instruments such as Just Transition and RRF), market structure (share of employment in EGSS and dependence on high-emissions-intensive industries) and innovation and competitiveness (green patents, R&D spending, intensity of exports of environmental goods).

Indicators are normalized on the interval [0, 1] by min–max transformation, with inversion for variables with an unfavourable meaning (e.g., share of employment in polluting industries). Aggregation by dimension and composite score are initially performed with equal weights, followed by robustness tests based on techniques such as PCA and AHP.

Each component captures not only a structural component of the green transition but also its direct implications on the labour market—from the availability of human capital and occupational retraining to the demand for digital skills and the emergence of green jobs.

For each dimension

d, the score for country

i at time

t is calculated as follows:

where

is the number of indicators belonging to dimension

d, and

are the weights assigned to each item. In the basic formula, all weights are equal, reflecting the assumption that each indicator has the same relative importance.

To strengthen the robustness of the results and avoid excessive dependence on a single methodological option, the analysis was completed by applying alternative weighting schemes. The PCA derives weights directly from the data variance structure, highlighting indicators with a more pronounced contribution to the dynamics of the system. In parallel, the AHP introduces a perspective based on expert judgments and comparative reasoning, through which the relevance of indicators is calibrated according to cognitive and experiential assessments.

The empirical outputs of these procedures confirm the stability of the index. The first three PCA components explain 72.4% of the total variance, with the first component accounting for 48.7%, indicating that innovation-, skills-, and infrastructure-related indicators contribute most strongly to the latent structure of the index. Sensitivity checks using ±10% perturbations of normalized indicators show that country rankings remain stable within a ±5% range.

The AHP consistency ratio (CR = 0.06) falls well below the 0.10 threshold, indicating reliable expert judgments. The resulting weights for the five GLMRI dimensions range narrowly between 0.17 and 0.23, confirming that no single pillar dominates the structure of the composite index and validating the equal-weight baseline specification. These outputs demonstrate that the GLMRI remains robust across alternative weighting schemes.

By combining a statistical method with a cognitive-expert one, the GLMRI results acquire multiple validations, reducing the sensitivity to arbitrary choices of weights and at the same time increasing the consistency and credibility of the scientific approach. The GLMRI for country

i in year

t is calculated as the weighted mean of the dimension scores:

In the standard formula, all dimensions have equal weight (, but the choice reflects the starting assumption that none of the five dimensions can be neglected, all contributing to a comparable extent to readiness. Nonetheless, sensitivity tests are also performed by applying differential weights, obtained either through PCA or by consulting experts.

On top of that, GLMRI values range from 0 to 1. Scores close to 1 indicate high readiness, characterized by adapted human capital, consistent investment, solid institutions, a diversified occupational structure, and a strong innovation ecosystem. Scores close to 0 signal serious vulnerabilities, such as dependence on polluting industries, lack of infrastructure, low administrative capacity, and a shortage of green skills.

A distinct advantage of the index lies in the possibility of supporting a typological classification of states according to their level of readiness, thus providing a nuanced interpretative framework for comparative analysis. The distribution of the resulting scores makes it possible to identify three main clusters. The first category, associated with a high degree of readiness, brings together advanced economies, characterized by robust institutional, technological, and structural foundations, which give them solid premises for a sustainable transition. The second category, corresponding to a moderate level of readiness, includes economies in a transformation process, in which significant strengths coexist with structural vulnerabilities that require corrections. The third category includes economies with a low degree of readiness, marked by increased exposure to systemic risks and the need for massive and coordinated interventions.

Such a stratification has not only descriptive value but also an instrumental function: it allows the articulation of differentiated public policy recommendations. For highly prepared countries, the focus can be on strengthening innovation and technological capabilities; for moderately prepared countries, on accelerating structural reconversion and stimulating investment flows; and for poorly prepared countries, on mobilizing comprehensive support, both domestic and international, capable of reducing vulnerabilities and creating the minimum conditions for transition.

Compared to previous models, the GLMRI brings two novelties. First, it integrates dimensions that have been treated separately in the literature, creating a coherent overall picture. Second, the index is designed not only as a descriptive tool but also as a foundation for predictive analysis by combining it with econometric models and machine learning algorithms. The choice of the data sources was dictated by two fundamental criteria: the availability of comparable data for a consistent number of European Union Member States over a sufficiently long period (2010–2024) and the relevance of the indicators for the five dimensions of the index—education and skills, investment and infrastructure, policies and institutions, labour market structure, and innovation and competitiveness.

A synthetic overview of the empirical foundations of the dataset appears in

Table 2, which reports descriptive statistics for the indicators employed. The values reflect patterns observed across the period 2010–2024 in the nine Member States analyzed and remain consistent with ranges documented by Eurostat, CEDEFOP, OECD, and IEA. This descriptive layer clarifies the scale, variability, and distributional structure of the variables before advancing toward the econometric estimations and machine-learning forecasts.

Prior to estimation, the external explanatory variables employed in the econometric analysis are characterized through descriptive statistics. These statistics, reported in

Table 3, document the scale, variability, and empirical range of the regressors over the 2010–2024 period, together with their units of measurement and data sources, thereby facilitating a transparent interpretation of the regression outcomes.

The dispersion reported in

Table 3 confirms that the selected variables capture heterogeneous energy-system configurations, institutional capacity, and structural labour-market exposure across EU Member States, consistent with their role as external conditioning factors in the subsequent econometric analysis.

3.2. Integrated Methodological Framework for Index Construction and Forecasting

The construction and validation of the Green Labour Market Readiness Index (GLMRI) follow a multi-stage analytical workflow, combining statistical rigour with policy relevance. The process begins with the selection of indicators reflecting five foundational dimensions: education and skills, investment and infrastructure, policies and institutions, labour market structure, and innovation and competitiveness. These indicators are drawn from harmonized and publicly available sources, with the complete list detailed in

Appendix A.

All indicators are normalized to a common [0, 1] scale using min–max transformation, with reverse scaling applied to unfavourable metrics (e.g., employment in polluting sectors). Dimension scores are computed as unweighted arithmetic means of their normalized indicators. A composite GLMRI score is then generated through equal-weight aggregation across dimensions, with subsequent robustness checks using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to validate the weighting structure.

In the second phase, the study applies panel data econometric models to examine how external energy-system characteristics, institutional capacity, and macro-structural conditions are associated with observed variation in GLMRI scores across countries and over time. Fixed-effects (FE) and random-effects (RE) models are estimated, with Hausman tests guiding model selection. Control variables such as GDP per capita, unemployment rate, and demographic dependency ratio are included to capture general macroeconomic conditions.

For forward-looking analysis, the third phase employs machine learning algorithms—Random Forest (RF), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural networks—to forecast GLMRI trajectories under multiple policy scenarios. Each algorithm addresses different modelling needs: RF for interpretability, XGBoost for accuracy, and LSTM for capturing temporal dependencies.

Three scenarios are simulated: optimistic, baseline, and pessimistic, each defined by exogenous adjustments to investment, training, and institutional parameters. The scenario outputs support the construction of a readiness typology—segmenting countries into high, moderate, and low readiness groups—and inform the design of differentiated policy packages. These insights offer a strategic foundation for tailored public interventions, aiming to foster inclusive and resilient labour market transitions.

3.3. Typological Classification and Country Segmentation

One aspect that makes the GLMRI useful beyond its numerical dimension is the possibility of ordering countries into typologies of readiness for the green transition. A simple score—be it 0.58 or 0.62—says little in the absence of an interpretative framework; small differences at the statistical level can correspond to very different institutional and structural situations. By classifying, scores become intelligible, being transformed into a language accessible to decision-makers and converted into applicable guidelines for public policies.

The need for a typology becomes clear when we look at the diversity of the European Union. Northern and western countries, supported by early investments and innovative ecosystems, tend to be placed at the top of the distribution. In contrast, southern and eastern countries face structural difficulties that linear values cannot sufficiently capture. Segmentation brings order to this diversity, bringing together countries with similar features and facilitating differentiated recommendations.

The classification is no longer just a statistical snapshot but becomes a prioritization tool, avoiding misleading interpretations: economies that appear advanced may hide weaknesses, and countries starting from a lower level may record significant progress that deserves to be recognized. In particular, the segmentation of the GLMRI makes it possible to align employment and training policies to the real level of training of each economy, avoiding uniform solutions that do not respond to differences in the labour market.

The methodology applied combines simple steps and more sophisticated techniques. In a first phase, the distribution of GLMRI values was divided into thirds, which allowed the establishment of clear thresholds: above 0.70—high readiness; between 0.55 and 0.70—moderate readiness; below 0.55—low readiness. This rule has the advantage of transparency and replicability. Subsequently, in order not to depend exclusively on a statistical convention, clustering algorithms (k-means and hierarchical clustering) were used, capable of detecting natural groups of countries based on multidimensional similarities. The two procedures provided, in most cases, convergent results, confirming the coherence of the typologies obtained.

Segmentation paves the way for the differentiation of public policies. Highly prepared countries can invest in cutting-edge innovation and the improvement of advanced skills. Moderately prepared countries need mixed policies: additional resources, more robust institutions, and accelerated reconversion. Low-prepared countries require large-scale interventions, including extensive training programmes and the gradual restructuring of economies dependent on polluting industries. This typological segmentation provides not only an analytical classification but also a policy-relevant tool, allowing differentiated policy design across EU member states according to their readiness profile.

3.4. External Determinants of Labour-Market Readiness for the Green Transition

Econometric analysis is conducted using fixed-effects and random-effects panel data models to examine how external energy-system characteristics, institutional capacity, and macro-structural conditions shape labour-market readiness for the green transition, as captured by the GLMRI. Given the composite nature of the index, the analysis does not pursue causal identification but focuses on identifying systematic associations between readiness outcomes and external structural factors. The use of panel specifications allows the exploitation of both longitudinal and cross-sectional variation while accounting for unobservable, time-invariant country-specific effects.

In this approach, the composite GLMRI scores are related to a set of structurally external explanatory variables, capturing energy-system characteristics, institutional capacity, and macro-structural labour-market exposure that are not used in the construction of the index. Cross-country and temporal variation in labour-market readiness is therefore associated with exogenous systemic constraints and enabling conditions of the green transition, rather than with any internal component, dimension score, or aggregation mechanism of the GLMRI.

The European labour market is a spatial and temporal phenomenon with data available for nine member states, covering a period of 15 years (2010–2024). The structure requires the use of panel data regression models, which allow the simultaneous exploitation of cross-sectional variation (differences between countries) and longitudinal variation (evolutions over time). Unlike simple time series or cross-sectional regressions, panel models have the advantage of being able to control for unobservable country-specific factors—such as organizational culture, institutional traditions, or geographical characteristics—that remain constant over time but influence the level of readiness.

The basic model has the following form:

where

-denotes the composite index value for country

i in year

t; the vector of explanatory variables includes energy-system characteristics (renewable electricity share and energy import dependency), institutional capacity indicators (government effectiveness and absorption rate of EU structural funds), and macro-structural labour-market exposure measures (employment share in fossil-fuel–intensive sectors). None of these variables enters the normalization, aggregation, or weighting procedures used to construct the GLMRI;

-vector of control variables (GDP per capita, unemployment rate, demographic indicators);

-unobservable effects specific to each country (constant over time);

-idiosyncratic error term;

α-common intercept term;

-regression coefficients capturing the association between external energy-system indicators, institutional quality measures, and macro-structural labour-market characteristics and the GLMRI;

-coefficient or vector of coefficients for the control variables, which allow the isolation of the estimated relationships from general macroeconomic influences.

It is important to clarify that the GLMRI dimension-level variables reported in

Table 2 are used exclusively for index construction and validation. These dimension scores do not enter the econometric specification in Equation (5), which relies solely on a structurally independent set of external covariates describing energy-system characteristics, institutional quality, and macro-structural labour-market conditions. Mechanical and conceptual circularity is avoided by design, as the econometric specification relies exclusively on explanatory variables external to the construction of the GLMRI, ensuring that the estimated associations do not mechanically reflect, reproduce, or restate the internal structure or arithmetic of the index.

Specifically, the external regressors employed in Equation (5) are neither dimension scores, nor linear transformations, nor aggregations of the indicators used in the construction of the GLMRI. Instead, they capture independent systemic conditions that shape the speed, intensity, and social absorption of the energy transition. Consequently, the econometric analysis cannot be interpreted as a decomposition of the index, but rather as an examination of how exogenous energy-system, institutional, and macro-structural constraints are associated with observed labour-market readiness outcomes.

Two types of panel models were estimated: fixed effects (FE) and random effects (RE). The FE model assumes that differences between countries can be captured by unit-specific intercepts, controlling for fixed characteristics over time. The RE model assumes that these differences are random and uncorrelated with the explanatory variables. The choice between the two specifications was made using the Hausman test, which checks whether the RE estimates are consistent.

In most cases, the data indicate a significant correlation between the unobservable effects and the explanatory variables, which justifies the preference for the FE model. Even so, the RE estimates were kept as an exercise in robustness. All models were estimated using STATA 17, and robustness checks were performed using R 4.3. Both fixed- and random-effects models were tested.

Panel data analyses are sensitive to a number of statistical problems. First, heteroscedasticity—the unequal variation in errors across countries—was checked by the Breusch–Pagan test and corrected by using robust Driscoll–Kraay errors. Second, autocorrelation over time was tested by the Wooldridge test, the results confirming the existence of a serial dependence, which required the adjustment of standard errors. Third, cross-sectional dependence, inevitable in an integrated European Union, was assessed by the Pesaran CD test, and the results showed significant correlations between countries, confirming the need to apply robust corrections.

Attention was also paid to multicollinearity between explanatory variables, tested by the VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) indicator. The results showed acceptable levels, except for some partial overlaps between investment and innovation, which required alternative estimates to verify the stability of the coefficients.

The conceptual and operational validation of the model is carried out through a comparative analysis applied to nine European Union Member States: Germany, France, Sweden, Spain, Italy, Greece, Poland, Romania, and the Czech Republic. The selection of these countries is based on three criteria: (1) the availability of longitudinal and comparable data for the 2010–2024 period across all index dimensions; (2) the representation of geographical and institutional diversity within the EU—covering Northern, Southern, and Eastern regions; and (3) the inclusion of economies at different stages of the green transition, from structurally advanced to more vulnerable or transition-challenged states. This approach ensures a balanced sample for testing the robustness and transnational applicability of the GLMRI framework.

Germany and France represent major Western European economies, each with ambitious climate policies and substantial public investment capacities. Their well-developed infrastructure and institutional frameworks position them as benchmarks for advanced readiness. Sweden exemplifies the Nordic model, combining high levels of innovation, strong digital competencies, and adaptable education systems—traits that support rapid and sustainable transitions. Spain and Italy reflect Southern European profiles. These countries benefit from significant potential in renewable energy (particularly solar) and the modernization of building stock, but continue to face regional inequalities and institutional rigidities that can hinder transition effectiveness.

Greece highlights structural vulnerabilities and the need for differentiated support policies to avoid amplifying social tensions. Poland and Romania belong to the eastern group, where dependence on polluting industries and sensitive industrial segments accentuates the pressure for accelerated reconversion. The Czech Republic offers an intermediate case: a competitive industrial economy, but faced with uneven rates of skills updating and challenges in the field of innovation. Together, these states illustrate the full spectrum of European transition and constitute a suitable terrain for testing and validating a comparable index at a transnational level. While the current selection allows for methodological consistency and regional representativeness, future research could expand the scope to additional Member States as more granular and comparable data become available.

3.5. Forecasting Scenarios Using Machine Learning Techniques

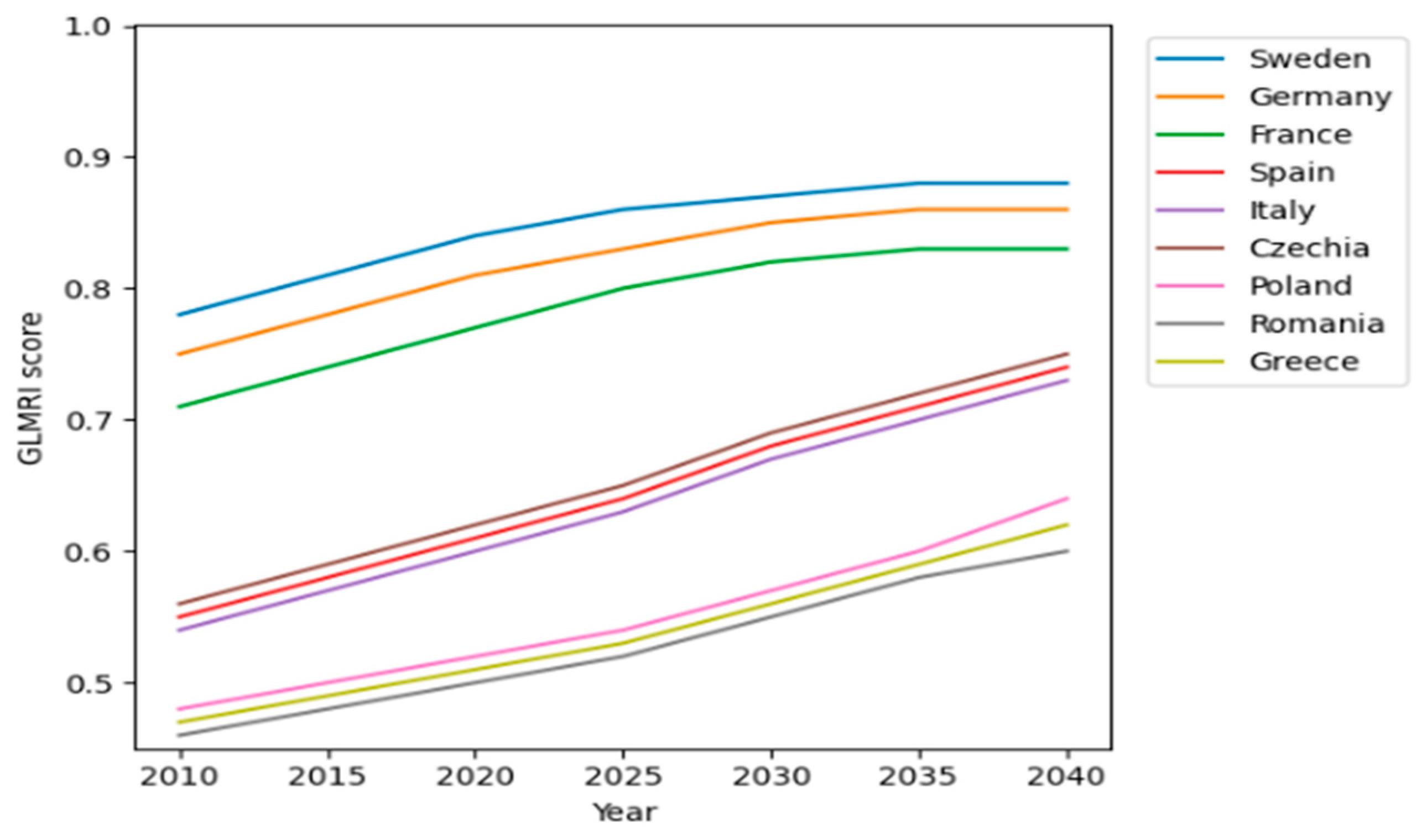

A distinctive element of this study is the scenario architecture. Three trajectories are constructed: an optimistic scenario (acceleration of the Green Deal implementation, increased investments in green infrastructure, expanded training programmes), a baseline scenario (continuation of recent trends without major changes), and a pessimistic scenario (institutional delays, economic shocks, social resilience). The scenarios are not simple narrative exercises; the parameters of the dimensions and context variables are explicitly adjusted, and the ML models project the GLMRI trajectories corresponding to these permutations.

The scenario architecture is anchored explicitly in the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) and in the financial envelopes of the Just Transition Fund (JTF). The baseline trajectory reflects the investment paths, policy commitments, and labour-market adjustments specified in the most recent NECP revisions. The moderate-transition scenario corresponds to partial absorption of JTF resources and mid-range decarbonisation targets, while the accelerated-transition scenario aligns with full utilization of JTF funding and the upper-bound NECP objectives for renewable deployment, energy-efficiency gains, and reskilling requirements in carbon-intensive regions. By grounding each trajectory in quantified policy benchmarks, the scenarios move beyond narrative assumptions and remain consistent with the regulatory and financial architecture of the EU green transition.

The structure of the national energy mix represents a fundamental contextual source of variation for scenario development, as the speed and depth of labour-market adjustments depend on the extent to which countries rely on carbon-intensive or low-carbon energy sources. Economies with a more diversified and renewables-oriented energy mix typically experience smoother transition trajectories, characterized by higher demand for green skills and lower exposure to displacement in fossil-dependent sectors. In contrast, member states with energy systems dominated by coal, oil, or gas face steeper structural adjustments, stronger reskilling requirements, and higher risks of transition-related labour-market disruption. Incorporating these energy-system characteristics into the scenario parameters ensures that the projected GLMRI trajectories reflect not only institutional and economic dynamics, but also the decarbonisation constraints embedded in the underlying energy mix of each country.

The integration of these elements produces a structured segmentation of European labour markets into three levels of readiness for the green transition. The first group—high-readiness economies—includes contexts in which human capital, infrastructure, institutional quality, and innovation capacity jointly facilitate a rapid and effective absorption of transition-driven changes. In such settings, policy priorities focus on refining skills, maintaining employment quality, and supporting internal labour mobility.

The second category, moderate preparedness, brings together economies with strengths but also structural vulnerabilities, where the priorities are professional retraining, investment consolidation, and institutional capacity strengthening; these markets require periodic monitoring mechanisms and triggers for targeted interventions. The third category, low preparedness, includes vulnerable areas dependent on polluting industries and characterized by insufficient infrastructure; here, a continuous and complex intervention regime is needed, focused on professional training, incentives for green investments, public–private partnerships, and active support for occupational transitions.

The selection of nine countries allows testing the model in very different contexts. Germany and France can serve as benchmarks for new standards of training: a combination of high-performance education, modern infrastructure, solid institutions, and innovative ecosystems. Sweden, with a strong focus on research and digitalization, indicates rapid adaptation trajectories. Spain and Italy bring to the fore southern dynamics, where uneven performance between regions requires differentiated approaches. Greece raises issues of structural vulnerability.

Poland and Romania highlight challenges of accelerated, managed modernization, while the Czech Republic offers a case of a competitive industry faced with the need for skill renewal. Beyond comparative results, this distribution supports the external validation of the framework: training classes identified through GLMRI correlate with independent measures of educational performance, innovation, and green investment.

For the projections up to 2040, the study combines complementary machine learning algorithms to capture different data regularities. Random Forest and XGBoost models nonlinear relationships and complex interactions between dimensions and control variables, while LSTM neural networks exploit the temporal dependencies in the GLMRI series. Validation is based on walk-forward procedures that avoid information leakage, and forecast accuracy is assessed using RMSE, MAE, and MAPE. Beyond technical performance, interpretability is ensured by feature importance analysis and SHAP, which support the dialogue with policymakers. In this way, GLMRI serves a dual purpose: it provides a compact synthetic measure of labour market readiness and, through scenario-based forecasts, provides concrete guidance for policymaking, allowing for early detection of skills gaps, structural unemployment risks, and institutional bottlenecks, as well as the calibration of interventions such as targeted training, smart investment incentives, mobility support, and social cohesion measures.

Scenario projections apply the same min–max bounds established for the construction of the historical GLMRI series (2010–2024). No additional rescaling is performed during the forecasting horizon, which ensures full comparability between observed and projected GLMRI values and prevents distortions in the interpretation of scenario dynamics.

In operational terms, each ML procedure receives the multivariate predictor vector:

The dependent variable enters as:

where

records the observed value of the Green Labour Market Readiness Index at time

. The projected readiness level under each scenario is denoted by

which represents the model-generated forecast of the GLMRI value for the subsequent period.

Random Forest generates its forecasts as:

where

denotes the regression function associated with the

k-th tree and

expresses the total number of trees in the ensemble.

XGBoost constructs its output as:

where

represents the

m-th boosted regression tree and

marks the number of boosting iterations. Model complexity in XGBoost is determined by the regularized objective function:

where

denotes the number of leaves in tree

,

represents the associated leaf weights, and the parameters

and

control structural and weight-based regularization.

LSTM networks operate through gated transformations applied sequentially on

. The input gate is:

where

marks the input-weight matrix,

the recurrent-weight matrix,

the gate bias, and

the logistic activation. The output gate takes the form:

where

,

, and

modulate the visible component of the internal state.

Candidate memory content is generated by

where

,

, and

define transformations updating latent memory.

The cell state evolves according with

where

denotes element-wise multiplication.

The hidden state is updated through

where

regulates the range of the internal signal.

The projected value emerges as

where

expresses the dense-layer weights and

the output bias.

All models were trained on the 2010–2024 series through walk-forward validation respecting chronological structure. Hyperparameter selection for the tree-based models relied on grid-based exploration, while the LSTM network employed dropout layers and early stopping. Forecast accuracy was evaluated using three complementary indicators and the root-mean-square error was computed as:

where

denotes the number of observations in the evaluation segment,

the observed GLMRI value, and

the predicted value. RMSE reflects the magnitude of squared deviations and is sensitive to larger errors.

The mean absolute error is defined as:

where

and

retain the same meaning as above. MAE measures the average magnitude of prediction errors without penalizing outliers as strongly as RMSE.

The mean absolute percentage error was computed as:

where the ratio

expresses the relative prediction error. MAPE reports deviations in percentage terms and facilitates cross-country comparability when index magnitudes differ.

The smoothness of scenario trajectories reflects the scenario-driven adjustments to the input variables rather than a smoothing effect imposed by the ML models. When historical volatility is preserved in the inputs, the ML forecasts display proportional variability; monotonicity emerges only under scenario parameters that assume sustained directional change.

Complementarity among the algorithms further strengthens robustness: Random Forest contributes interpretability, XGBoost enhances predictive performance in structured data environments, and LSTM captures dynamic patterns embedded in the temporal evolution of readiness. Their integrated use provides a nuanced representation of labour-market responses under different transition intensities.

The use of ML algorithms is justified by three main arguments. First, the green transition is a nonlinear and context-dependent process in which the evolution of labour markets does not follow simple trajectories but is influenced by multiple factors—from political and investment changes to technological innovations and exogenous shocks. Second, the relationships between the GLMRI dimensions are not always stable: for example, the effect of investments on readiness may be conditioned by the level of skills or the quality of institutions. Third, the labour market is characterized by strong temporal dependencies, which makes it useful to use algorithms that can capture sequential patterns.

The ML models were trained on the basis of the historical series 2010–2024, which includes both the GLMRI scores and the explanatory variables: individual dimensions (education, investment, policies, structure, and innovation) and macroeconomic control variables (GDP per capita, unemployment rate, and demographic dependency ratio).

The data was divided into training and validation sets using the walk-forward validation procedure, which respects the temporal structure and avoids information leakage from the future to the past. Although the sample size is modest, the risk of overfitting was mitigated through walk-forward validation, regularization mechanisms in XGBoost, constrained tree depth in Random Forest, and dropout plus early stopping in LSTM. Sensitivity checks confirmed that the models generalize adequately under out-of-sample evaluation.

The simulation setup involved training ML models on the historical dataset (2010–2024), with a train-test split respecting temporal order (walk-forward validation). For Random Forest and XGBoost, hyperparameter tuning was conducted using grid search (n_estimators, max_depth). LSTM networks were trained using TensorFlow with an input window of 5 years and a batch size of 32, optimizing RMSE. Feature importance for tree-based models was assessed using Gini impurity and SHAP values, while LSTM interpretability relied on gradient-based sensitivity analyses.

In order to make the predictions, three complementary algorithms were selected, each bringing distinct methodological advantages and responding to specific challenges of the analysis. The first is the Random Forest Regressor, an algorithm based on ensembles of decision trees, recognized for its robustness against the phenomenon of overfitting and for the relatively high degree of interpretability it offers [

46]. Through the mechanism of calculating the importance of variables (feature importance), this algorithm allows not only to obtain predictions but also to identify the factors that contribute most to the results. From this perspective, its usefulness goes beyond the purely technical sphere, providing information directly relevant to the substantiation of public policies.

The second algorithm used is XGBoost, established in the specialized literature for its superior performance in modelling tabular data [

47]. Its ability to capture complex interactions between variables and to generate highly accurate predictions explains its spread in numerous competitions and machine learning applications. Its choice in the context of GLMRI is justified by its ability to handle relatively limited data sets in volume but is characterized by a complex internal structure specific to the analyzed socio-economic phenomena.

The last algorithm selected is LSTM, a recurrent neural network architecture developed to capture temporal dependencies in time series [

48]. Unlike tree-based models, LSTM learns from the sequentiality of data, which gives it the ability to anticipate future trajectories based on historical patterns. In the analysis of labour markets, this feature proves to be particularly valuable, as it allows capturing inertia and adjustment rhythms characteristic of transition processes.

By integrating the three algorithms—Random Forest for interpretability, XGBoost for predictive performance, and LSTM for dynamic dimension modelling—the proposed methodology capitalizes on their complementarity, achieving a balance between transparency, accuracy, and sensitivity to the temporal structure of the data.

For enhanced methodological transparency and full reproducibility,

Table 4 summarizes the operational configuration of the machine-learning framework. The table reports the exact predictor set used by each algorithm and the structure of the corresponding output, consistent with the mathematical specifications presented in the methodological section.

The forecasts were developed based on three alternative scenarios, designed to reflect the dynamics of the green transition according to anticipated political and economic developments. In the optimistic version, the transition is accelerated by the rigorous implementation of the European Green Deal, by mobilizing consistent investments in infrastructure and sustainable technologies, by expanding educational programmes oriented towards green skills, and by strengthening the institutional framework. Such a configuration suggests a rapid convergence towards an economic model capable of integrating innovation and sustainability into the structure of the labour market [

49,

50,

51].

The baseline scenario, built by extrapolating recent trends, assumes the maintenance of existing policies and a moderate pace of investments. It represents a useful baseline to assess the degree of progress that can be achieved through continuity, without major public policy interventions. At the opposite end, the pessimistic scenario takes into account significant delays in policy implementation, possible economic or energy crises, and forms of social resistance to change. In such a configuration, the transition would be slow, and structural vulnerabilities would persist or even increase. These scenarios reflect not only general economic trajectories but also the anticipated impact on labour markets—from job creation in green sectors and the need for new skills to the risk of structural unemployment in economies dependent on polluting industries.

The parameters of the three scenarios are operationalized through exogenous adjustments applied to the explanatory variables. The optimistic configuration assumes accelerated expansion of investment and training participation, the baseline variant preserves the continuation of recent trends without systematic alteration, and the pessimistic scenario reflects contractions in these processes.

For enhanced methodological transparency, the magnitude of all scenario adjustments is explicitly quantified and expressed relative to the 2024 baseline. Within the optimistic trajectory, investment-related indicators, participation in training programmes, institutional capacity, and innovation intensity increase by approximately +15% over the projection horizon, while the structural vulnerability component decreases by −10%, consistent with accelerated decarbonisation and sectoral restructuring. The baseline scenario maintains each predictor at its last observed value, without additional perturbation. Under the pessimistic trajectory, investment and training indicators decline by −10%, institutional capacity deteriorates by −8%, and structural vulnerability rises by +12%, reflecting a delayed and uneven transition process.

These calibrated modifications are incorporated directly into the predictor vector and subsequently processed within the machine-learning framework defined by Equations (6)–(16). The explicit quantification of scenario shocks ensures that the resulting GLMRI projections can be clearly attributed to the scenario assumptions rather than to artefacts of algorithmic behaviour.

By integrating statistical procedures with complementary machine-learning techniques, the forecasting architecture provides a coherent and evidence-based platform for informing strategic policy design in the context of the EU green transition.

4. Results

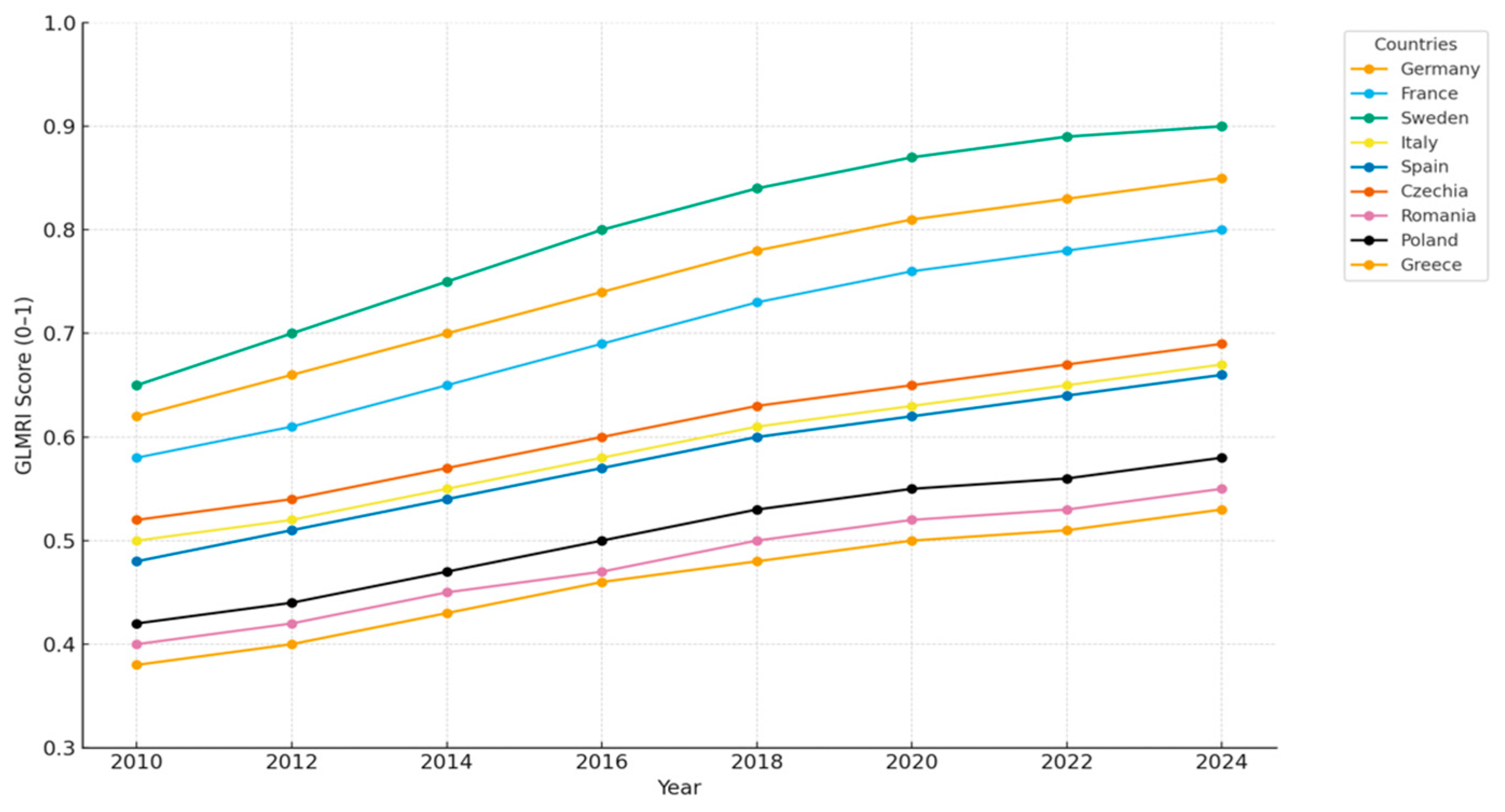

The analysis provides a nuanced picture of the readiness of European labour markets for the green transition, highlighting heterogeneous dynamics across countries and regions. The GLMRI values, computed for the period 2010–2024 and illustrated in

Figure 1, should not be interpreted as mere numerical scores but as synthetic expressions of complex social, economic, and institutional realities.

The longitudinal trajectories in

Figure 1 highlight significant structural differences in the readiness of labour markets for the green transition in the nine member states analyzed between 2010 and 2024. The Nordic and Western economies—in particular Sweden, Germany, and France—consistently rank at higher levels, with values reaching or exceeding the 0.80 threshold in 2024. Their performance is associated with sustained investments in renewable energy, advanced education systems, and institutional robustness, which facilitate the absorption of green jobs and the development of high-level skills.

By contrast, Italy, Spain, and the Czech Republic are in an intermediate zone, with scores between 0.55 and 0.70. The developments indicate gradual progress, but also the persistence of vulnerabilities, such as regional disparities and institutional rigidities, which reduce the pace of adaptation of labour markets to the demands of the green transition.

At the lower end of the distribution, Romania, Poland, and Greece register values below 0.55 throughout the period. Moderate upward trends coexist with major structural challenges: dependence on carbon-intensive industries, limited investment in retraining, and fragile institutional frameworks. The labour markets in these economies remain exposed to risks of structural unemployment and require major interventions, including extensive training programmes and specific support for industrial restructuring. The dynamics observed over the period 2010–2024 indicate not only differences in level but also distinct structural profiles, which can be better captured by segmentation than by individual scores.

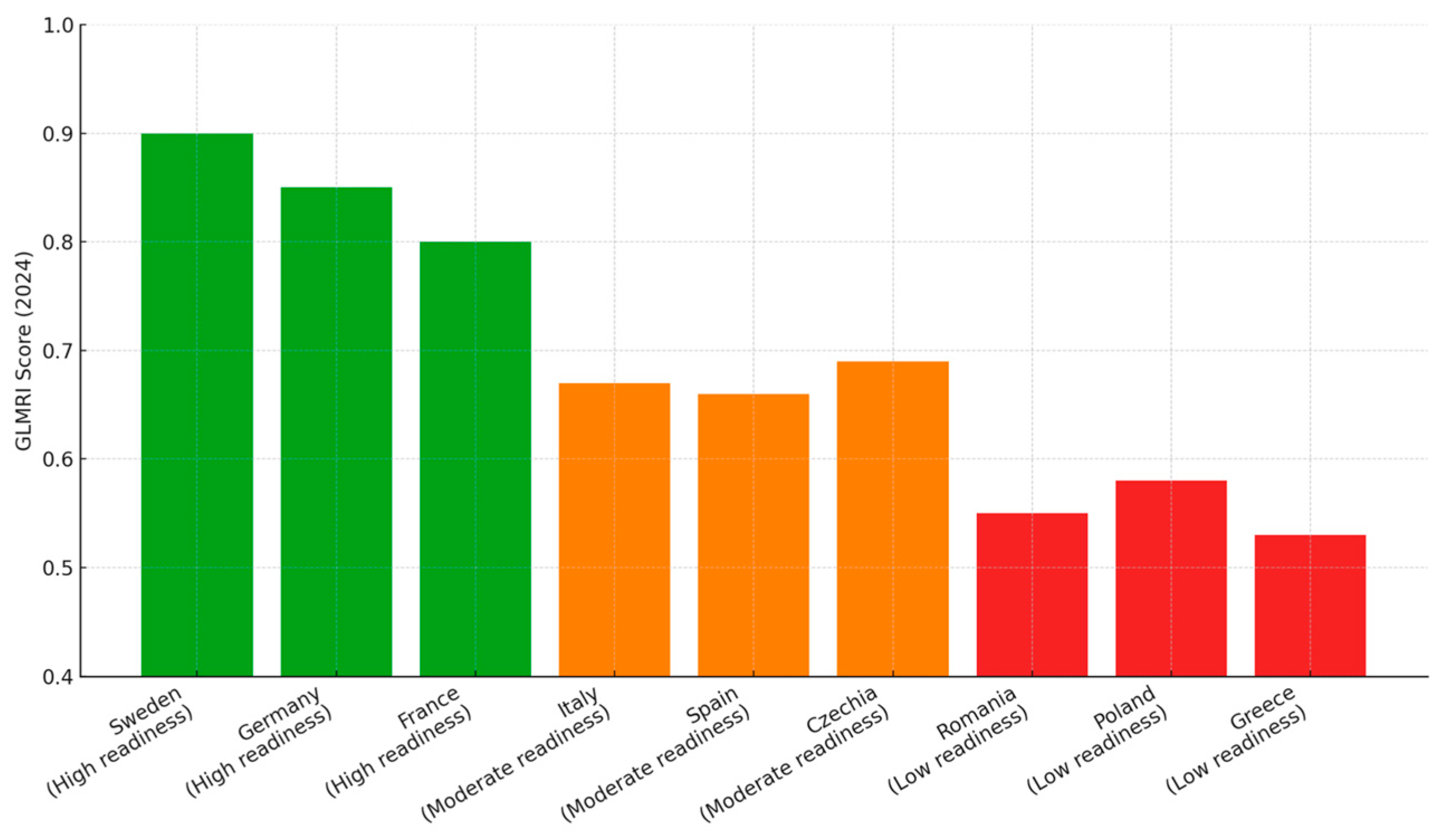

Figure 2 illustrates these configurations, structuring the nine countries analyzed into three clusters of readiness for the green transition. The typology is not a simple statistical exercise but expresses profound occupational differences, with direct implications for professional opportunities, job security, and workforce retraining needs.

The segmentation is not only statistically relevant but also reflects the divergent occupational experiences of millions of workers and maps the opportunities, but also the risks associated with the transition. The high-readiness cluster, represented by Sweden, Germany, and France, highlights consolidated labour markets, characterized by highly qualified human capital, sustainable infrastructures, and robust institutions. In these countries, the green transition translates into the emergence of stable careers, extensive access to continuous training, and the integration of green jobs into innovative ecosystems, which increases job security and reduces social inequalities.

Italy, Spain, and the Czech Republic, included in the intermediate cluster, illustrate a partially consolidated transformation process. Visible progress in areas such as sustainable construction and electric mobility coexists with institutional rigidities and regional disparities. For workers in these economies, the transition offers new occupational opportunities but also the risk of territorial fragmentation, which calls for more ambitious policies for reconversion and adaptation of skills.

At the lower end of the distribution are Romania, Poland, and Greece, where structural vulnerabilities limit the capacity to integrate the green transition. Dependence on carbon-intensive industries, low levels of green skills, and institutional fragility expose labour markets to increased risks of structural unemployment and precariousness. For workers in these countries, the transition is not yet perceived as an opportunity but as a pressure that amplifies professional uncertainty.

The typology confirms the existence of a northwest versus southeast fracture in terms of readiness for the green transition. Beyond the comparative dimension, the figure sends an essential message: the green transition does not generate the same effects for all Europeans. While some benefit from stable careers and access to innovative opportunities, others face increased risks of job loss and the urgent need for institutional support. Differentiated policies thus become the necessary condition for transforming the transition from a vector of polarization into a driver of inclusive development and social cohesion at the European level.

A clear assessment of the predictive behaviour of the machine-learning algorithms appears in

Table 5, which reports out-of-sample accuracy metrics obtained under walk-forward validation. The comparison across RMSE, MAE, and MAPE illustrates the distinct strengths of each method in capturing nonlinear structures, temporal patterns, and cross-country variation in GLMRI dynamics.