Integrating Trend Monitoring and Change Point Detection for Wind Turbine Blade Diagnostics: A Physics-Driven Evaluation of Erosion and Twist Faults

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Trend Monitoring (TM): TM tracks the long-term evolution of statistical features (e.g., energy, mean, kurtosis) to reveal gradual deviations from a healthy operating state [16]. It is effective for identifying slow, wear-related degradation but generally cannot pinpoint the exact moment a fault begins.

- Change Point Detection (CPD): CPD uses statistical methods, such as Cumulative Sum (CUSUM) [17] or Bayesian Online Change Point Detection (BOCPD) [18], to detect the precise time at which the underlying data generation process changes abruptly. These techniques excel at identifying sudden or dynamic fault events [19,20].

- Case 1—Leading-edge erosion: Discrete wavelet transform (DWT), suited for multi-resolution transient analysis, is paired with BOCPD to assess whether advanced CPD methods improve the detection of gradual, surface-level degradation.

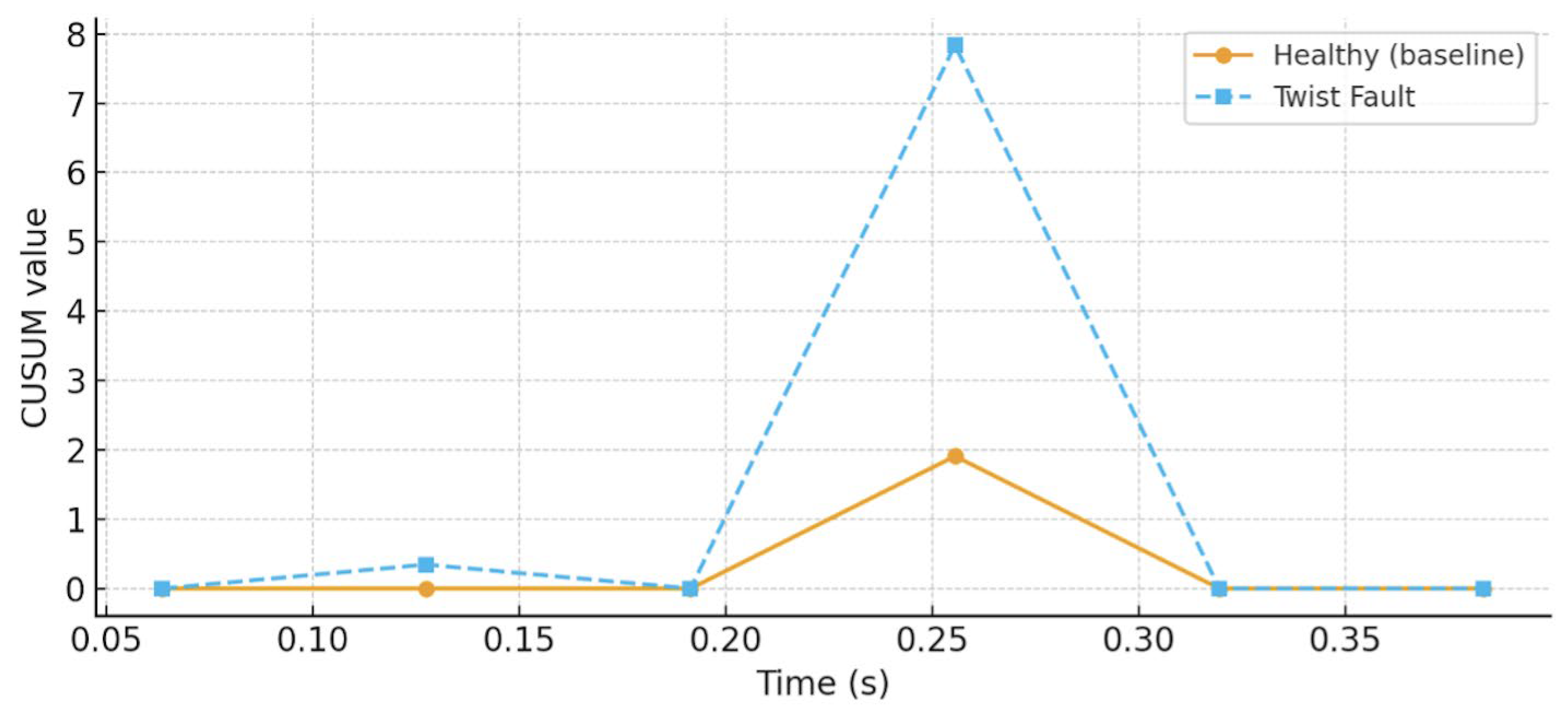

- Case 2—Twist misalignment: The short-time Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), effective for capturing harmonic behavior, is combined with the CUSUM algorithm to identify the spectral redistribution and instability associated with aerodynamic imbalance.

- Methodological integration: We present a unified diagnostic workflow that systematically links time–frequency feature extraction with statistical decision-making tools.

- Physics-informed tool selection: Through experimental evidence, we show that leading-edge erosion introduces a global energy offset—making it best identified through feature-based trend monitoring—whereas twist faults induce spectral redistribution, for which centroid-based CPD is more effective.

- Practical engineering guidelines: We provide a comparative, application-oriented roadmap to help practitioners select appropriate monitoring strategies based on the physical characteristics of the anticipated fault.

- For gradual erosion faults characterized by persistent spectral deviation, does incorporating advanced CPD (e.g., BOCPD) provide additional diagnostic value beyond feature-based trend monitoring?

- For twist-induced aerodynamic instabilities, can the combined use of frequency-domain analysis and the CUSUM algorithm effectively isolate and pinpoint the resulting spectral fluctuations?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.1.1. Dataset Description

2.1.2. Experimental Setup

2.1.3. Measurement Procedure and Fault Scenarios Investigated

2.1.4. Dataset Structure

2.2. Trend Monitoring and Change Point Detection Methods

2.2.1. Trend Monitoring

- (a)

- Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)

- (b)

- Wavelet Transform (WT) and Discrete Wavelet Decomposition (DWT)

2.2.2. Change Point Detection

- (a)

- Bayesian Online Change Point Detection (BOCPD)

- denotes the current run length at time t.

- represents the observed data (e.g., vibration amplitude, temperature).

- is the transition probability, governed by the hazard function.

- is the likelihood of the new observation given the current run length.

- (b)

- Cumulative Sum (CUSUM)

- is the observed value at time .

- represents the baseline mean under normal operating conditions.

- is the drift reference value, typically set to , where is the magnitude of the shift to be detected.

- The max (0, …) function resets the accumulation when the signal remains close to the target, preventing negative drift.

2.3. Proposed TM–CPD Integration

- Leading-edge surface erosion detection using DWT–BOCPD integration: DWT, which provides multi-resolution insight into transient energy variations, is paired with BOCPD. This combination is used to determine whether sophisticated CPD techniques enhance the detection of gradual surface degradation.

- Twist misalignment detection using FFT–CUSUM integration: FFT, well suited for resolving harmonic behavior, is integrated with the CUSUM algorithm to capture the subtle spectral redistribution and instability caused by aerodynamic imbalance.

3. Case Studies and Results

3.1. Case 1—Surface Erosion Fault

3.1.1. DWT Analysis

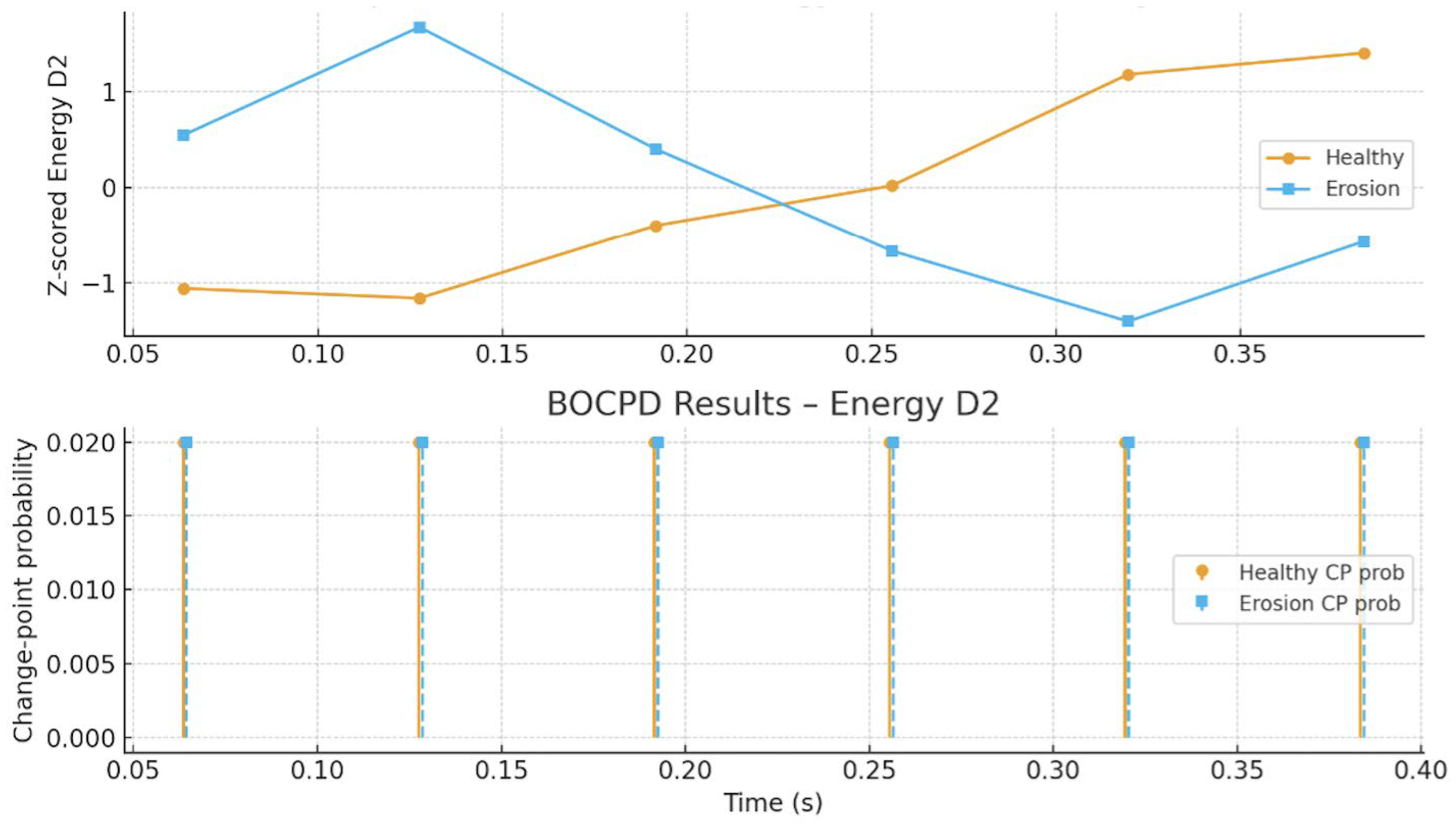

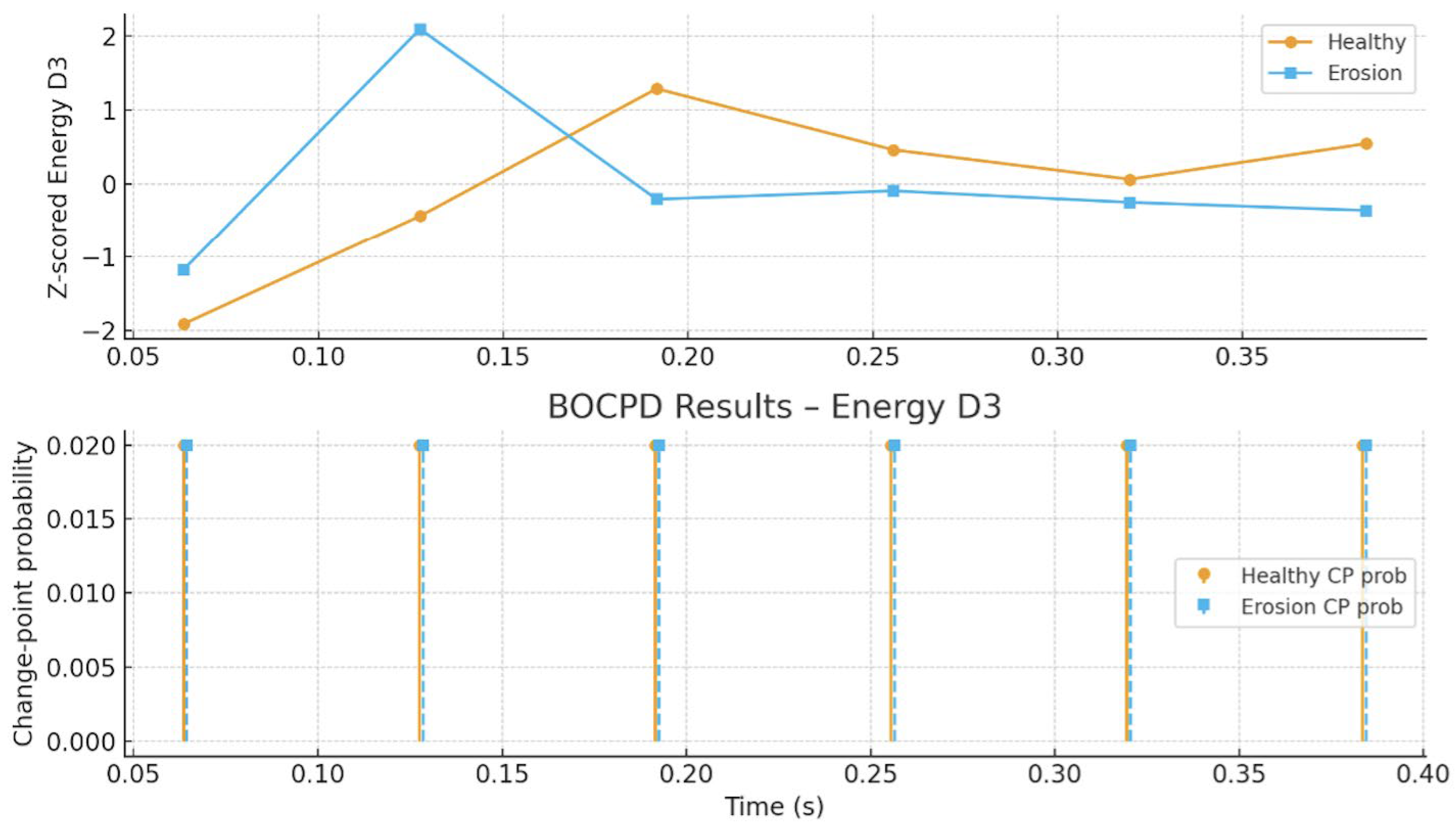

3.1.2. BOCPD Analysis

3.2. Case 2—Twist Fault

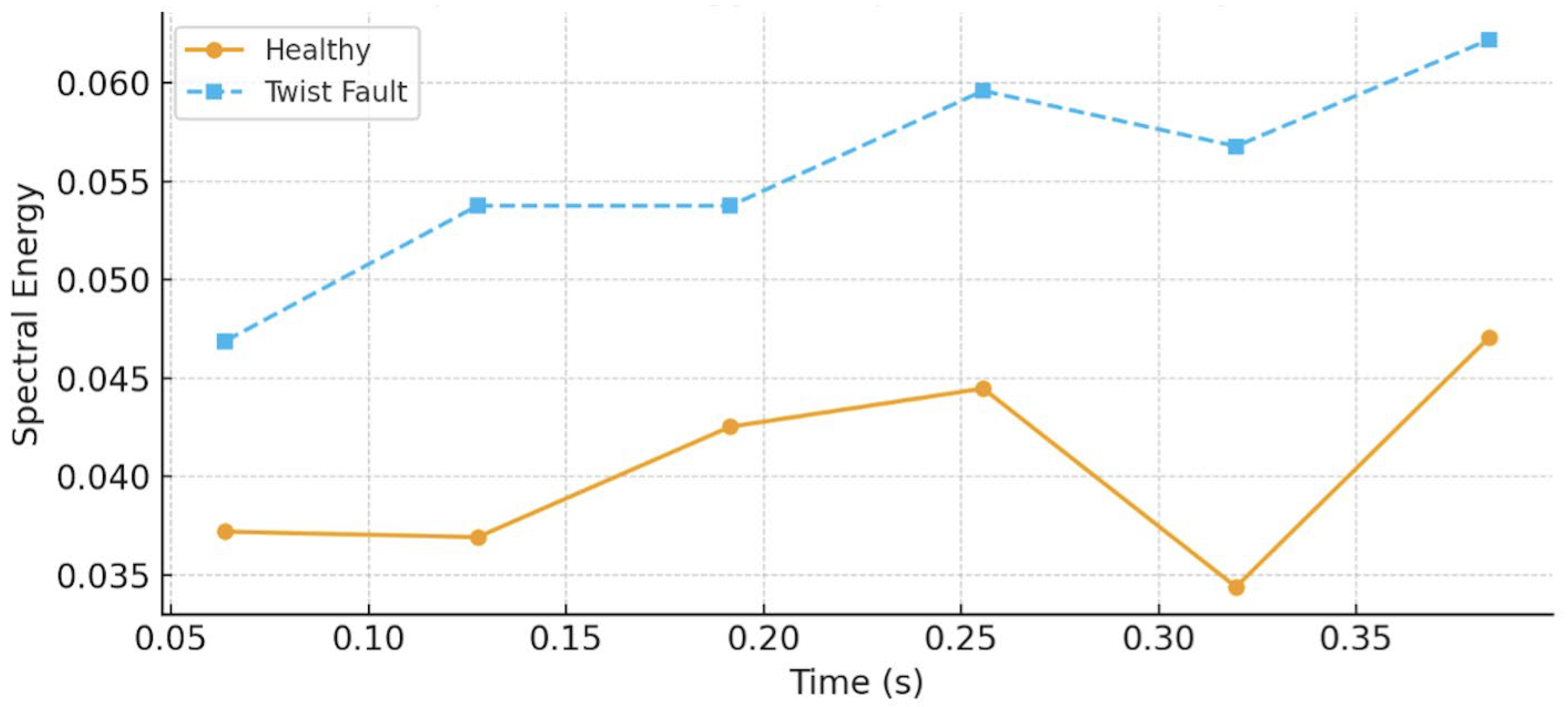

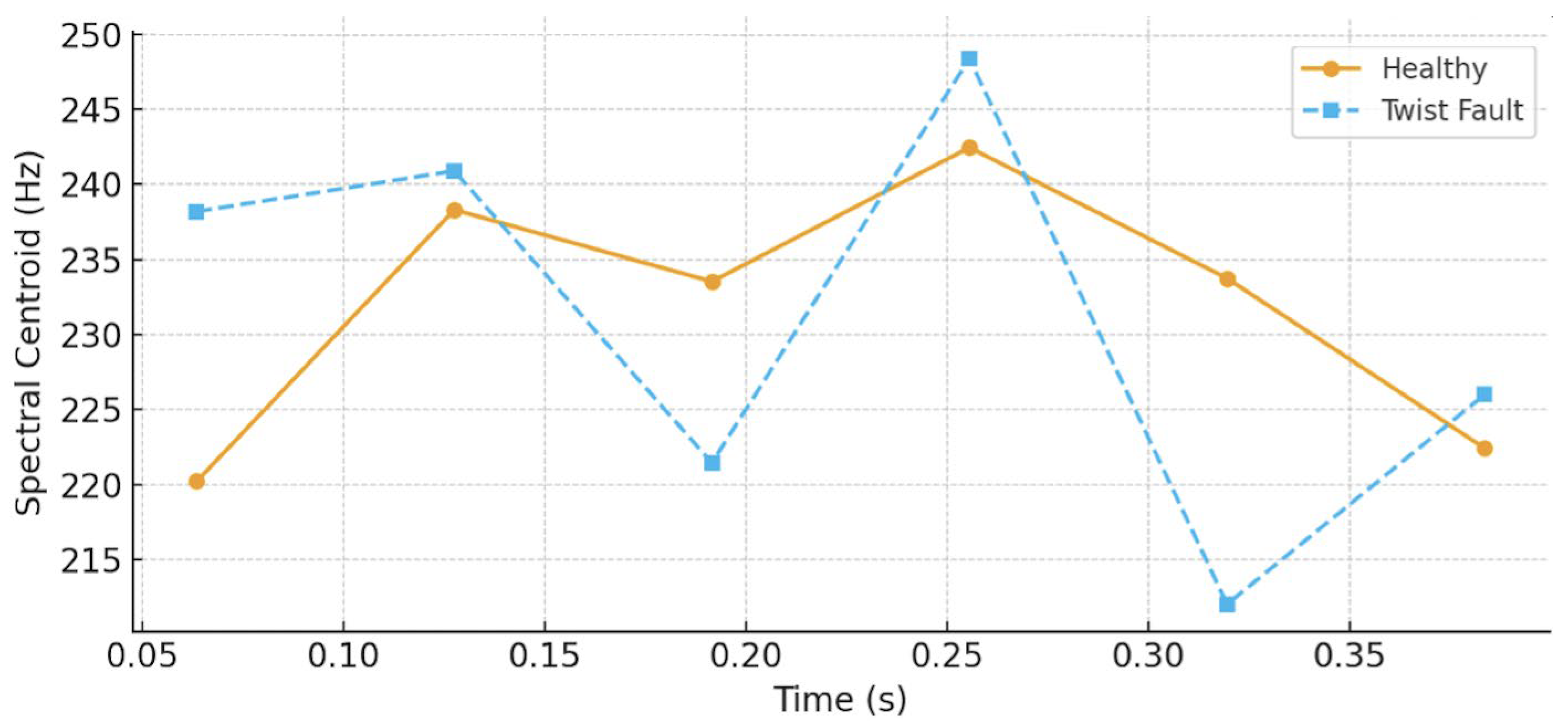

3.2.1. FFT Features

3.2.2. CUSUM Detection Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Case 1: Erosion Fault Detection Using DWT and BOCPD

4.2. Case 2: Twist Fault Detection Using FFT and CUSUM

4.3. Rationale for TM–CPD Selection by Fault Type

5. Conclusions

6. Prospects and Future Applications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| DFT | Discrete Fourier Transform |

| BOCPD | Bayesian Online Change Point Detection |

| DWT | Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| CM | Condition Monitoring |

| TM | Trend Monitoring |

| CPD | Change Point Detection |

| O&M | Operation and Maintenance |

| db4 | Daubechies-4 |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Electricity |

| STFT | Short-Time Fourier Transform |

| FRP | fiber-reinforced polymer |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| WT | Wavelet Transform |

| EEEC | Equipo de Energía Eólica Controlado” (which translates to Computer Controlled Wind Energy Unit) |

| PCB | PicoCoulomB |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| CSV | Comma Separated Values |

| CUSUM | Cumulative Sum |

| AEP | Annual Energy Production |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

References

- IRENA; CPI. Global Landscape of Energy Transition Finance 2025; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2025. Available online: https://www.irena.org/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Bošnjaković, M.; Katinić, M.; Santa, R.; Marić, D. Wind Turbine Technology Trends. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xue, Y.; He, C.; Zhao, Y. Review of the Typical Damage and Damage-Detection Methods of Large Wind Turbine Blades. Energies 2022, 15, 5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.C.; Kolios, A.; Wang, L.; Chiachio, M. A Wind Turbine Blade Leading Edge Rain Erosion Computational Framework. Renew Energy 2023, 203, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthé, G.; Abdallah, I.; Barber, S.; Chatzi, E. Modeling and Monitoring Erosion of the Leading Edge of Wind Turbine Blades. Energies 2021, 14, 7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visbech, J.; Göçmen, T.; Özçakmak, Ö.S.; Meyer Forsting, A.; Hannesdóttir, Á.; Réthoré, P.-E. Aerodynamic Effects of Leading-Edge Erosion in Wind Farm Flow Modeling. Wind Energy Sci. 2024, 9, 1811–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishnaevsky, L.; Hasager, C.B.; Bak, C.; Tilg, A.-M.; Bech, J.I.; Doagou Rad, S.; Fæster, S. Leading Edge Erosion of Wind Turbine Blades: Understanding, Prevention and Protection. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; El-Thalji, I.; Giljarhus, K.E.T.; Delimitis, A. Classification Analytics for Wind Turbine Blade Faults: Integrated Signal Analysis and Machine Learning Approach. Energies 2024, 17, 5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, K.; Stevanovic, N.; Cross, E.J.; Dervilis, N.; Worden, K. Damage detection in operational wind turbine blades using a new approach based on machine learning. Renew. Energy 2021, 168, 1249–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, S.A.; Krawczuk, M. A State-of-the-Art Review of Structural Health Monitoring Techniques for Wind Turbine Blades. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2025, 45, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshuva, A.; Sugumaran, V. A Lazy Learning Approach for Condition Monitoring of Wind Turbine Blade Using Vibration Signals and Histogram Features. Measurement 2020, 152, 107295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, J.W.; Li, F.; Zhai, E. Stall-Induced Vibrations Analysis and Mitigation of a Wind Turbine Rotor at Idling State: Theory and Experiment. Renew. Energy 2022, 187, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, S.; Leoni, J.; Cacciola, S.; Croce, A.; Tanelli, M. A Machine-Learning-Based Approach for Active Monitoring of Blade Pitch Misalignment in Wind Turbines. Wind Energy Sci. 2025, 10, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Correa, J.; Martín-Martínez, S.; Artigao, E.; Gómez-Lázaro, E. Using SCADA Data for Wind Turbine Condition Monitoring: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2020, 13, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letzgus, S. Change-Point Detection in Wind Turbine SCADA Data for Robust Condition Monitoring with Normal Behaviour Models. Wind Energy Sci. 2020, 5, 1375–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Kruger, U.; Gu, F.; Ball, A.; Chen, Q. Monitoring Nonstationary and Dynamic Trends for Practical Process Fault Diagnosis. Control Eng Pract. 2019, 84, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, P.B. A CUSUM-Based Approach for Condition Monitoring and Fault Diagnosis of Wind Turbines. Energies 2021, 14, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.P.; MacKay, D.J.C. Bayesian Online Changepoint Detection. arXiv 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ryck, T.; De Vos, M.; Bertrand, A. Change Point Detection in Time Series Data Using Autoencoders with a Time-Invariant Representation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2021, 69, 3513–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, A. Wavelets in Statistics: A Review. J. Ital. Stat. Soc. 1997, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelofs, C.M.A.; Lutz, M.A.; Faulstich, S.; Vogt, S. Autoencoder-Based Anomaly Root Cause Analysis for Wind Turbines. Energy AI 2021, 4, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, E.S.; Bonacina, F.; Corsini, A. Deep Anomaly Detection in Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines Using Graph Convolutional Autoencoders for Multivariate Time Series. Energy AI 2022, 8, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Q.; He, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, D.; Wang, X. Anomaly Detection of Wind Turbine Driveline Based on Sequence Decomposition Interactive Network. Sensors 2023, 23, 8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Hassan, A.; Dao, P.B. Bridging Data and Diagnostics: A Systematic Review and Case Study on Integrating Trend Monitoring and Change Point Detection for Wind Turbines. Energies 2025, 18, 5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogaili, A.A.F.; Abdulhady Jaber, A.; Hamzah, M.N. Wind Turbine Blades Fault Diagnosis Based on Vibration Dataset Analysis. Data Brief 2023, 49, 109414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, S. Fundamentals of Linear Systems: Analysis and Control. In Instrumentation and Control Systems for Nuclear Power Plants; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 207–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchakoua, P.; Wamkeue, R.; Ouhrouche, M.; Slaoui-Hasnaoui, F.; Tameghe, T.; Ekemb, G. Wind Turbine Condition Monitoring: State-of-the-Art Review, New Trends, and Future Challenges. Energies 2014, 7, 2595–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Court, R.; Jiang, J. Wind Turbine Condition Monitoring by the Approach of SCADA Data Analysis. Renew. Energy 2013, 53, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, C.J.; Zappalá, D.; Tavner, P.J. Survey of Commercially Available Condition Monitoring Systems for Wind Turbines 2014. Available online: https://durham-repository.worktribe.com/output/1632351 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Ismail, A.; Saidi, L.; Sayadi, M. Wind Turbine Power Converter Fault Diagnosis Using DC-Link Voltage Time–Frequency Analysis. Wind Eng. 2019, 43, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalá, D.; Tavner, P.J.; Crabtree, C.J.; Sheng, S. Side-band Algorithm for Automatic Wind Turbine Gearbox Fault Detection and Diagnosis. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2014, 8, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilselvan, P.; Wang, P.; Sheng, S.; Twomey, J.M. A Two-Stage Diagnosis Framework for Wind Turbine Gearbox Condition Monitoring. Int. J. Progn. Health Manag. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeliukstis, R. Continuous Wavelet Transform-Based Method for Enhancing Estimation of Wind Turbine Blade Natural Frequencies and Damping for Machine Learning Purposes. Measurement 2021, 172, 108897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminikhanghahi, S.; Cook, D.J. A Survey of Methods for Time Series Change Point Detection. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2017, 51, 339–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basseville, M.; Nikiforov, I.V. Detection of Abrupt Changes: Theory and Application; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993; 528p, Available online: https://people.irisa.fr/Michele.Basseville/kniga/kniga.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Dao, P.B. Condition Monitoring and Fault Diagnosis of Wind Turbines Based on Structural Break Detection in SCADA Data. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, P.B. On Cointegration Analysis for Condition Monitoring and Fault Detection of Wind Turbines Using SCADA Data. Energies 2023, 16, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, P.B.; Barszcz, T.; Staszewski, W.J. Anomaly Detection of Wind Turbines Based on Stationarity Analysis of SCADA Data. Renew. Energy 2024, 232, 121076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, P.B.; Staszewski, W.J.; Barszcz, T.; Uhl, T. Condition Monitoring and Fault Detection in Wind Turbines Based on Cointegration Analysis of SCADA Data. Renew. Energy 2018, 116, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, F.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Orchard, M.; Guarini, M.; Astroza, R. A Bayesian Approach for Fatigue Damage Diagnosis and Prognosis of Wind Turbine Blades. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 174, 109067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, K. Bayesian Online Change Detection of Multimode Processes with Application to Wind Turbines. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaknaki, I.-Y.; Lillo, F.; Mazzarisi, P. Bayesian Autoregressive Online Change-Point Detection with Time-Varying Parameters. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2025, 142, 108500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratumnopharat, P.; Leung, P.S.; Court, R.S. Wavelet Transform-Based Stress-Time History Editing of Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine Blades. Renew. Energy 2014, 63, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Gao, R.X.; Chen, X. Wavelets for Fault Diagnosis of Rotary Machines: A Review with Applications. Signal Process. 2014, 96, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, A.; Sapre, C.A.; Selig, M.S. Effects of Leading Edge Erosion on Wind Turbine Blade Performance. Wind Energy 2014, 17, 1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergio Campobasso, M.; Castorrini, A.; Ortolani, A.; Minisci, E. Probabilistic Analysis of Wind Turbine Performance Degradation Due to Blade Erosion Accounting for Uncertainty of Damage Geometry. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 178, 113254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korczewski, Z.; Rudnicki, J. Active Diagnostic Experimentation on Wind Turbine Blades with Vibration Measurements and Analysis. Pol. Marit. Res. 2024, 31, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Lu, S.; Zhai, Z.; Jiang, C. Adaptive Fault Detection in Wind Turbine via RF and CUSUM. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2020, 14, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specification Parameter | Metric Value (SI) | Imperial/Standard Value |

|---|---|---|

| Broadband sensitivity | 10.2 mV/(m/s2) | 100 mV/g (±10%) |

| Dynamic range (peak) | ±491 m/s2 pk | ±50 g pk |

| Resolution (broadband) | 0.0016 m/s2 RMS | 16 μg RMS |

| Operational bandwidth | 0.5 Hz–10 kHz | 0.5–10,000 Hz |

| Feature | Healthy Blade | Eroded Blade | Absolute Difference | Percentage Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy D1 | 0.001550 | 0.001700 | +0.000150 | +9.68% |

| Entropy D1 | 3.0841 | 2.7904 | −0.2937 | −9.52% |

| Energy D2 | 0.001065 | 0.001545 | +0.000480 | +45.07% |

| Entropy D2 | 3.5792 | 3.2736 | −0.3056 | −8.54% |

| Energy D3 | 0.002002 | 0.002686 | +0.000684 | +34.17% |

| Entropy D3 | 4.0809 | 4.1865 | +0.1056 | +2.59% |

| Energy D4 | 0.003380 | 0.004125 | +0.000745 | +22.04% |

| Entropy D4 | 4.6143 | 4.8221 | +0.2078 | +4.50% |

| Time Center (s) | Spectral Energy | Spectral Centroid | Spectral Entropy | Dominant Frequency (Hz) | Fs (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0635 | 0.037193 | 220.212941 | 4.698935 | 50.78125 | 1000 |

| 0.1275 | 0.036908 | 238.313912 | 4.712699 | 0.00000 | 1000 |

| 0.1915 | 0.042527 | 233.527067 | 4.704256 | 0.00000 | 1000 |

| 0.2555 | 0.044467 | 242.466711 | 4.680576 | 46.87500 | 1000 |

| 0.3195 | 0.034379 | 233.744984 | 4.624165 | 50.78125 | 1000 |

| 0.3835 | 0.047053 | 222.422595 | 4.732791 | 50.78125 | 1000 |

| Time Center (s) | Spectral Energy | Spectral Centroid | Spectral Entropy | Dominant Frequency (Hz) | Fs (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0635 | 0.046868 | 238.201584 | 4.705423 | 46.87500 | 1000 |

| 0.1275 | 0.053766 | 240.903462 | 4.678903 | 50.78125 | 1000 |

| 0.1915 | 0.053763 | 221.446806 | 4.689938 | 50.78125 | 1000 |

| 0.2555 | 0.059613 | 248.396287 | 4.737508 | 50.78125 | 1000 |

| 0.3195 | 0.056793 | 212.019799 | 4.658341 | 50.78125 | 1000 |

| 0.3835 | 0.062206 | 225.994091 | 4.615763 | 46.87500 | 1000 |

| Aspect | Case 1—Erosion Fault (5 m/s) | Case 2—Twist Fault (5.3 m/s) |

|---|---|---|

| Operating condition | Constant wind speed 5 m/s; early-stage leading-edge surface erosion (uniform sandpaper-induced abrasion) | Wind speed 5.3 m/s; blade angle misalignment (one blade twisted) |

| Fault nature | Surface roughness increases at the leading edge, altering local aerodynamic smoothness | Twist deformation, causing asymmetric aerodynamic loading |

| Signal characteristics | Subtle but persistent global energy increase; nearly overlapping time-domain amplitudes | Clear increase in vibration amplitude and spectral variability compared to healthy |

| Analytical method | DWT (db4) + BOCPD | Short-time FFT + CUSUM |

| Key features used | Wavelet Energy (D2, D3) | Spectral Energy and Spectral Centroid |

| Main plot observations | Stable separation in DWT energy trends; BOCPD shows no distinct internal change points | Energy consistently higher; centroid exhibits sharp local spikes; CUSUM shows clear divergence |

| Detection type | Weak global trend; no distinct faults detected | Strong global elevation (energy) + clear localized anomaly (centroid) |

| Sensitivity focus | Broad-band, low-frequency structural changes | Frequency redistribution and spectral imbalance |

| Strengths | Good for analyzing multi-scale transients; useful for faults with sharp shocks | Excellent at capturing both persistent bias and transient spectral shifts |

| Limitations | Erosion fault too weak; BOCPD not effective with small feature differences | Requires short-time windowing and feature extraction |

| Best suited fault type | Gradual surface degradation and early aerodynamic wear | Twist, misalignment, and aerodynamic imbalance faults |

| Overall finding | DWT + BOCPD fails to reveal erosion signatures at low wind speeds due to minimal feature separation | FFT + CUSUM robustly identifies twist faults via both amplitude increase and centroid-based change-point signatures |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hassan, A.A.; Syed, N.H.R.; Teklemariyem, D.A.; Dao, P.B. Integrating Trend Monitoring and Change Point Detection for Wind Turbine Blade Diagnostics: A Physics-Driven Evaluation of Erosion and Twist Faults. Energies 2026, 19, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010112

Hassan AA, Syed NHR, Teklemariyem DA, Dao PB. Integrating Trend Monitoring and Change Point Detection for Wind Turbine Blade Diagnostics: A Physics-Driven Evaluation of Erosion and Twist Faults. Energies. 2026; 19(1):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010112

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassan, Abu Al, Nasir Hussain Razvi Syed, Debela Alema Teklemariyem, and Phong Ba Dao. 2026. "Integrating Trend Monitoring and Change Point Detection for Wind Turbine Blade Diagnostics: A Physics-Driven Evaluation of Erosion and Twist Faults" Energies 19, no. 1: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010112

APA StyleHassan, A. A., Syed, N. H. R., Teklemariyem, D. A., & Dao, P. B. (2026). Integrating Trend Monitoring and Change Point Detection for Wind Turbine Blade Diagnostics: A Physics-Driven Evaluation of Erosion and Twist Faults. Energies, 19(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010112