Research on Wave Environment and Design Parameter Analysis in Offshore Wind Farm Construction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

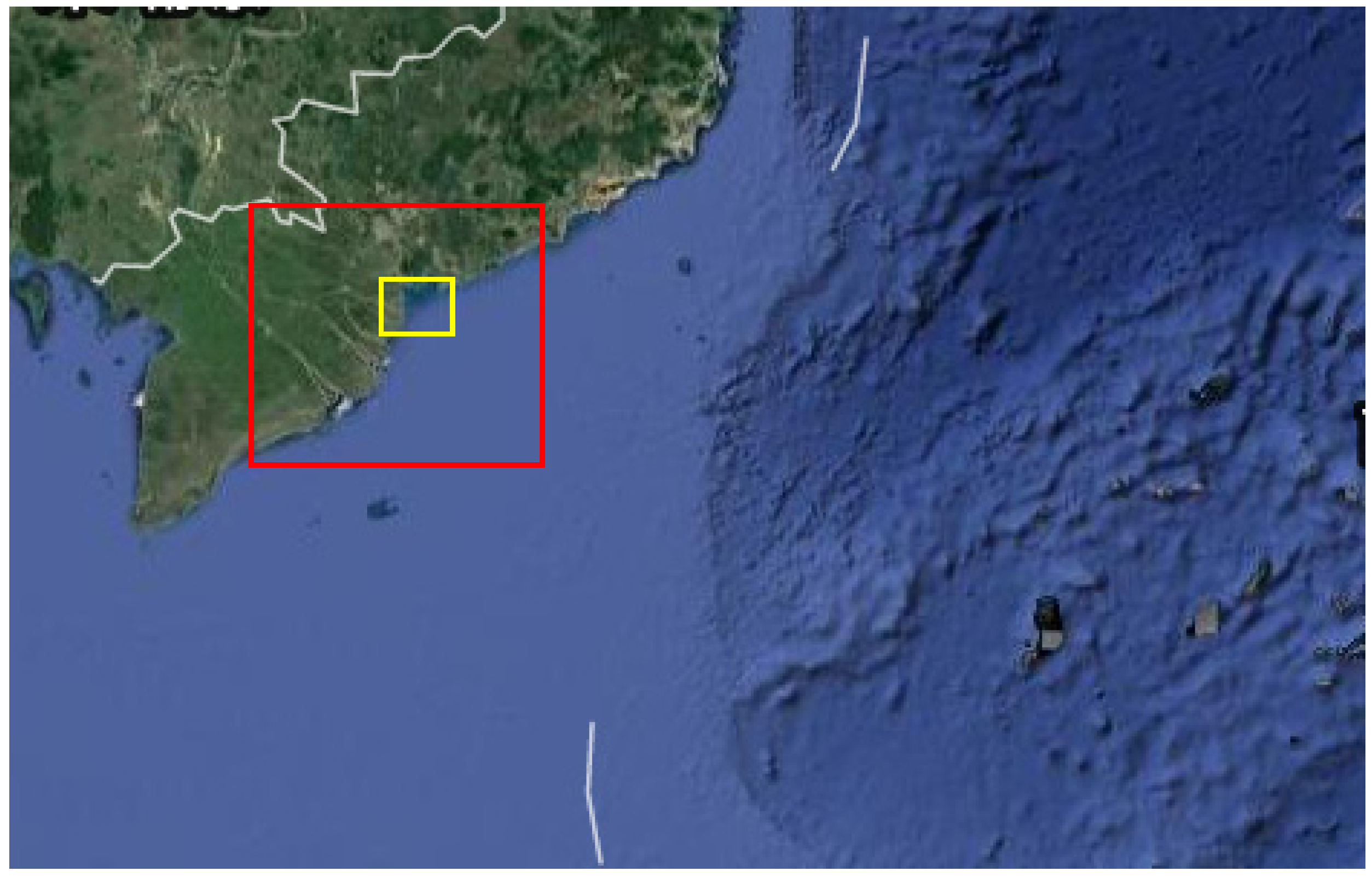

2.1. Study Area Overview

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Numerical Model Setup and Validation

2.3.1. WRF Model Setup and Validation

2.3.2. Wave Model Setup

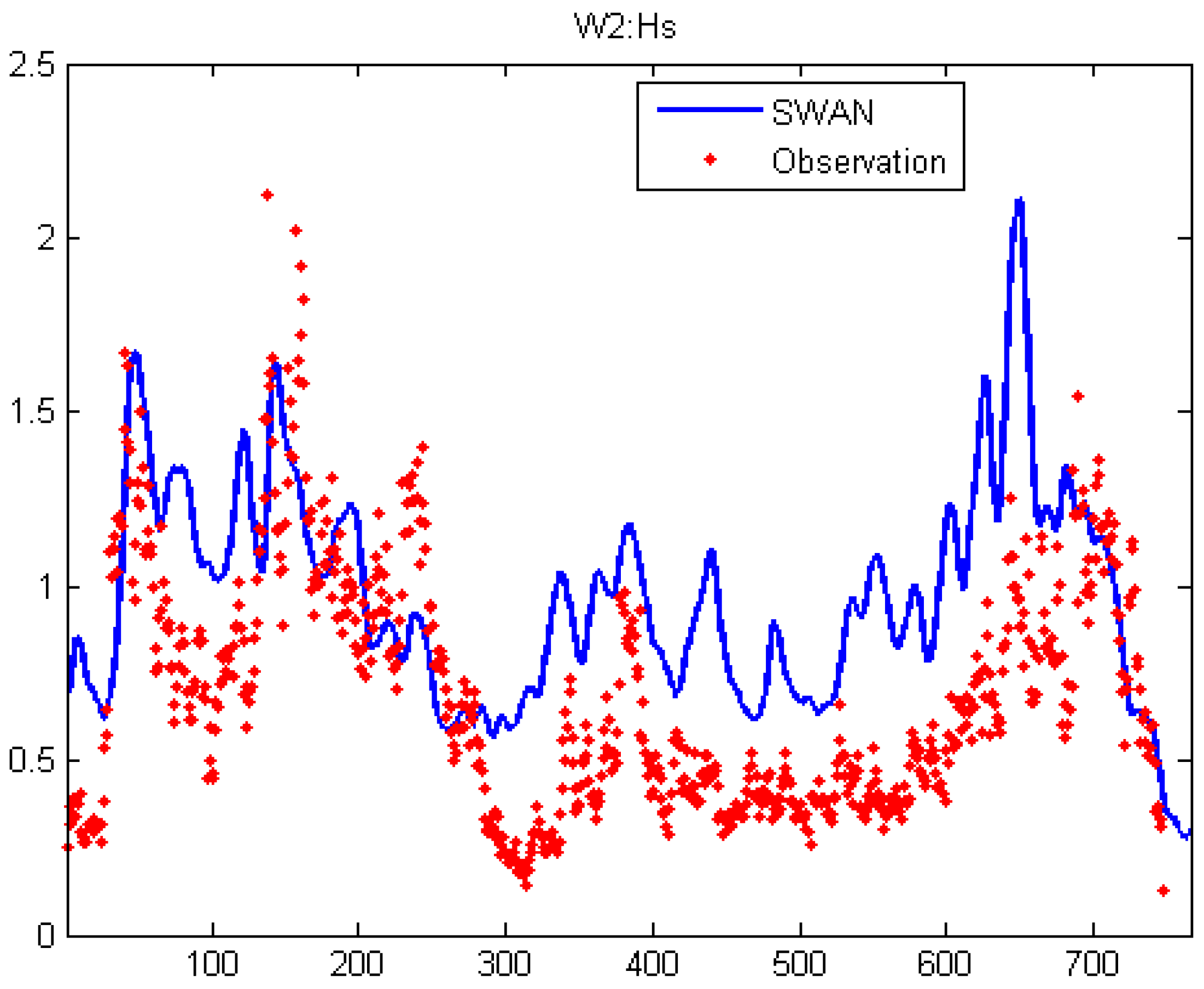

2.3.3. Model Validation

3. Results

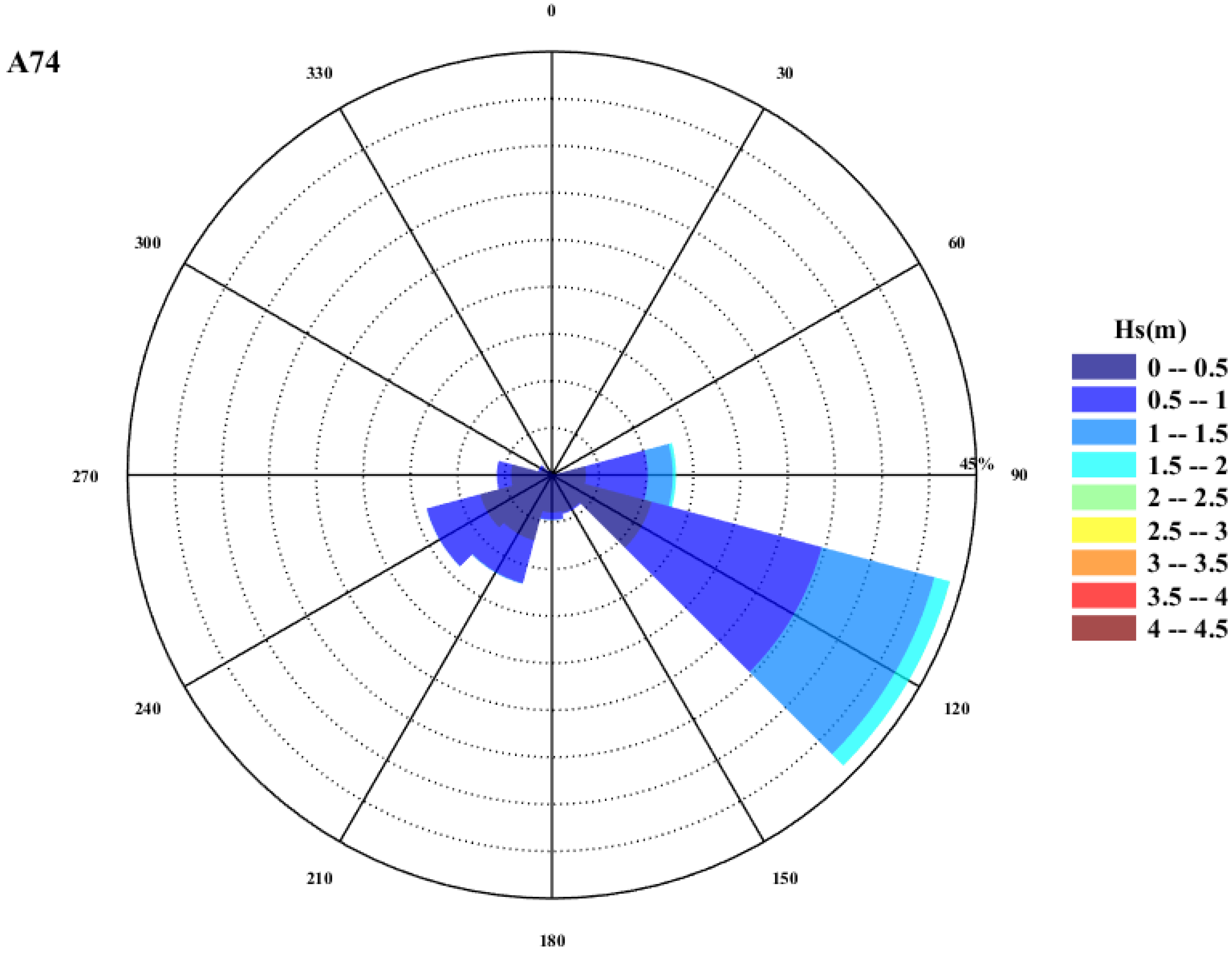

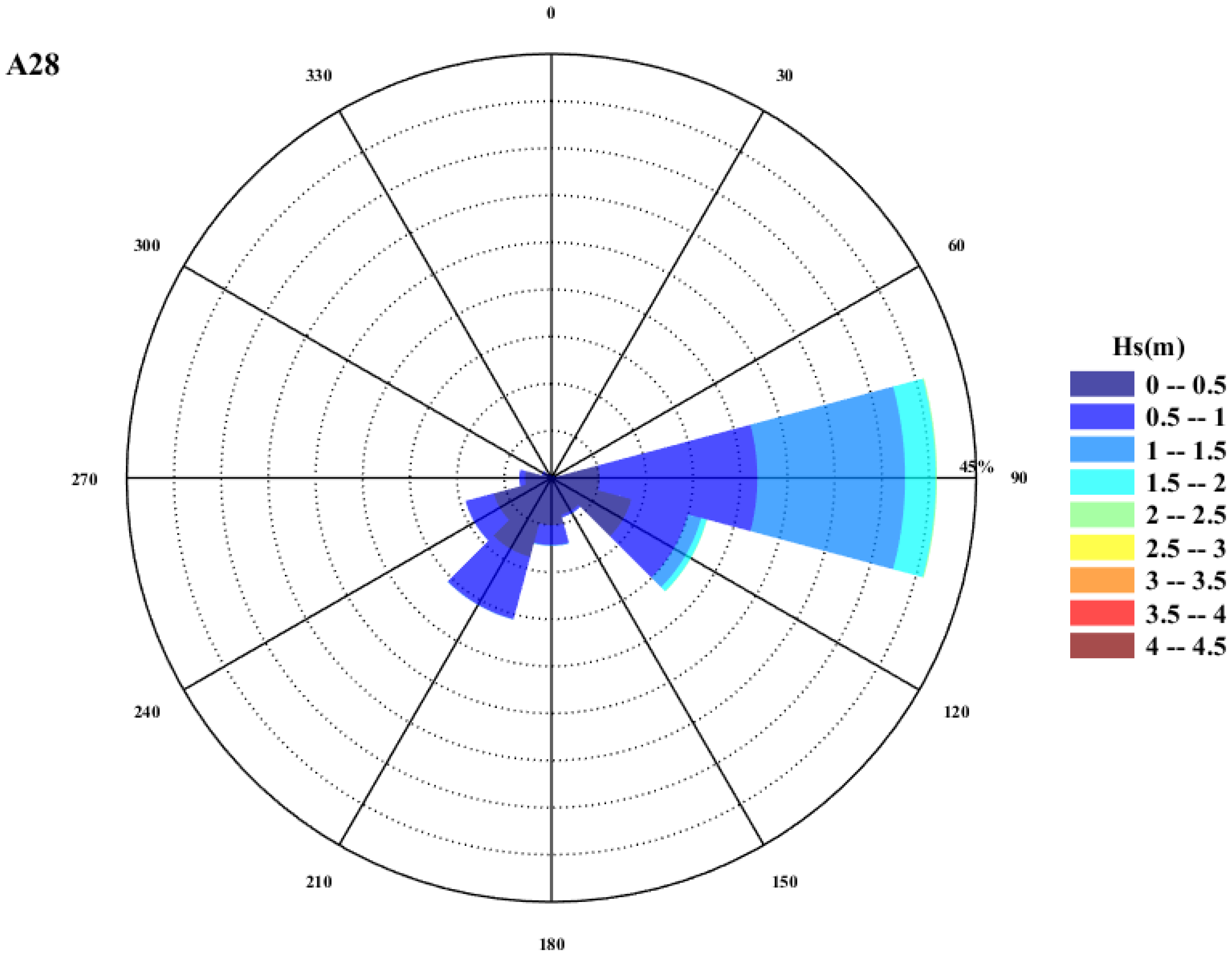

3.1. Wave Rose Analysis

3.2. Wave Characteristics at a Representative Point (A55)

3.2.1. Joint Distribution of Significant Wave Height and Mean Wave Direction

3.2.2. Joint Distribution of Significant Wave Height and Spectral Peak Period

3.2.3. Joint Distribution of Wave Direction and Wind Direction

3.3. Extreme Wave Analysis and Design Parameters

3.3.1. Statistical Analysis and Extreme Value Estimation Method

3.3.2. Extreme Wave Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Reliability and Sensitivity Analysis

4.2. Causes of Extreme Wave Directionality

4.3. Spatial Variability of Design Parameters and Engineering Implications

4.4. Compliance with Standards and Engineering Applicability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GWEC. Global Wind Report 2025; Global Wind Energy Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban, M.D.; Diez, J.J.; Lopez, J.S.; Negro, V. Why Offshore Wind Energy? Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufan, K.; Dalcal, A. Exploring Offshore Wind Energy: Trends, Investments, and Technological Advancements in the Global Energy Outlook. Russ. Electr. Eng. 2025, 96, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghany, G.A.; Soares, C.G. Global Trends and Challenges to Offshore Wind Energy in Vietnam. In Proceedings of the Vietnam Symposium on Advances in Offshore Engineering, Hanoi, Vietnam, 12–14 December 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro Ribeiro, T.; Duailibe Monteiro, P.R.; Zamboti Fortes, M.; Trezza Borges, T. A Comprehensive Review of Offshore Substations: Key Aspects and Trends. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2025, 18, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, M.; Li, W.; Liu, Y. Overview of Offshore Wind Power Technologies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61400-3; Design Requirements for Offshore Wind Turbines. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- DNV-OS-J101; Design of Offshore Wind Turbine. DNV GL: Oslo, Norway, 2016.

- Arany, L.; Bhattacharya, S.; Macdonald, J.; Hogan, S.J. Design of Monopiles for Offshore Wind Turbines in 10 Steps. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 92, 126–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Lian, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Liu, R. Research Progress on Offshore Wind Turbine Foundation Structures and Installation Technologies. Mar. Energy Res. 2025, 2, 10006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanem, E. Long-Term Time-Dependent Stochastic Modelling of Extreme Waves. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2011, 25, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.J.T.; Challenor, P.G. Estimating Return Values of Environmental Parameters. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2007, 107, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongklad, G.; Thanh, N.V.; Pattanaporkratana, A.; Chattham, N.; Jeenanunta, C. A Data-Driven Decision Support System for Wave Power Plant Location Selection. Water 2025, 17, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, P.V.; Thuy, N.B.; Kim, S.; Cuong, N.K.; Ngoc, P.K.; Khiem, M.V.; Hole, L.R. Impact of the Interaction of Surge, Wave, and Tide on the Surge and Wave on the Northern Coast of Vietnam for a Marine Storm Surge and Wave Forecast System. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 87, 104234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.W.; Zhuang, H.; Li, X.; Li, X.Q. Wind Energy and Wave Energy Resources Assessment in the East China Sea and South China Sea. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2012, 55, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Dong, S.; Wu, L.; Li, Z.; Mou, L.; Wang, A. Wind Wave Characteristics and Engineering Environment of the South China Sea. J. Ocean Univ. China 2014, 13, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Tangang, F.; Juneng, L.; Mustapha, M.A.; Husain, M.L.; Akhir, M.F. Wave Climate Simulation for Southern Region of the South China Sea. Ocean Dyn. 2013, 63, 961–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.W.; Pan, J.; Li, J.X. Assessing the China Sea Wind Energy and Wave Energy Resources from 1988 to 2009. Ocean Eng. 2013, 65, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.W.; Li, C.Y. Variation of the Wave Energy and Significant Wave Height in the China Sea and Adjacent Waters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, H.L. User Manual and System Documentation of WAVEWATCH III, Version 3.14; NOAA/NWS/NCEP/MMAB: College Park, MD, USA, 2009.

- Booij, N.; Ris, R.C.; Holthuijsen, L.H. A Third-Generation Wave Model for Coastal Regions 1. Model Description and Validation. J Geophys Res C Oceans 104(C4):7649-7666. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1999, 104, 7649–7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.B.; Barthelmie, R.J.; Pryor, S.C. Hurricane Impacts in the United States East Coast Offshore Wind Energy Lease Areas. Wind Energy Sci. 2025, 10, 2639–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.W.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Chen, H.C. Research on Wave Energy Resources in the Northern South China Sea during Recent 10 Years Using SWAN Wave Model. J. Subtrop. Resour. Environ. 2011, 6, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.S.; Song, Y.F.; Qiu, Z.; Chen, X.H.; Mai, B.Q.; Qiu, Y.W.; Song, L.L. Computation of Wave, Tide and Wind Current for the South China Sea Under Tropical Cyclones. China Ocean Eng. 2003, 18, 505–516. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.Y.; Peng, S.Y. Stress Analyses of the Offshore Wind Turbine Structures Subjected to Ocean Waves. In Proceedings of the 27th International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bredmose, H.; Jacobsen, N.G. Breaking Wave Impacts on Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations: Focused Wave Groups and CFD. In Proceedings of the ASME International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Shanghai, China, 6–11 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Shi, X. Understanding Precipitation Moisture Sources and Their Dominant Factors During Droughts in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duy Vinh, V.; Ouillon, S.; Van Thao, N.; Ngoc Tien, N. Numerical Simulations of Suspended Sediment Dynamics Due to Seasonal Forcing in the Mekong Coastal Area. Water 2016, 8, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Duan, Y. A Dynamical Initialization Scheme for Tropical Cyclones under the Influence of Terrain. Weather Forecast. 2018, 33, 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Z.; Duan, Q.; Shen, C.; Xie, Z. Improving WRF Typhoon Precipitation and Intensity Simulation Using a Surrogate-Based Automatic Parameter Optimization Method. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komen, G.J.; Hasselmann, S.; Hasselmann, K. On the Existence of a Fully Developed Wind-Sea Spectrum. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1984, 14, 1271–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.C.; Qi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, P.; Mao, Q. South China Sea Wind-Wave Characteristics. Part I: Validation of Wavewatch-III Using TOPEX/Poseidon Data. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2004, 21, 1718–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WAVEWATCH III | SWAN | |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | 98.0° E−135.0° E, 8.0° S−27.0° N | 104.7° E−111.0° E, 7.5° N−12.0° N |

| Resolution | 0.1° × 0.1° | 1′ × 1′ |

| Nonlinear Interactions | DIA | DIA + triad |

| Source Terms | JONSWAP | Komen et al. [31] |

| Bottom Friction | JONSWAP | JONSWAP |

| Depth-Induced Breaking | / | Battjes-Janssen |

| Station | Parameter | RMSE | Bias | Scatter Index (SI) | Correlation Coefficient (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W2 | (m) | 0.18 | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.92 |

| W2 | (s) | 0.76 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.87 |

| W1-2 | (m) | 0.21 | −0.07 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| W1-2 | (s) | 0.83 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.85 |

| Wave | 0 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 | 180 | 210 | 240 | 270 | 300 | 330 | SUM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wind | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.58 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 1.12 | |

| 30 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.36 | 1.11 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.59 | |

| 60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 9.66 | 3.33 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 13.14 | |

| 90 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 16.45 | 7.32 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 23.93 | |

| 120 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.03 | 9.25 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 11.63 | |

| 150 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 2.11 | 1.11 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.70 | |

| 180 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.18 | |

| 210 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.47 | 1.97 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.23 | |

| 240 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 3.38 | 12.31 | 0.59 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 17.10 | |

| 270 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.72 | 5.74 | 8.28 | 1.83 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 17.36 | |

| 300 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.80 | 0.62 | 0.15 | 2.92 | |

| 330 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 1.11 | |

| SUM | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 31.79 | 25.26 | 3.74 | 7.30 | 18.64 | 9.16 | 2.66 | 0.71 | 0.27 | 100 | |

| Station | Direction (°) | (m) | (s) | (m) | (s) | Water Depth (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A21 | 120 | 3.14 | 13.61 | 3.04 | 12.20 | 4.89 |

| A54 | 120 | 4.38 | 13.12 | 4.12 | 12.72 | 7.12 |

| A55 | 120 | 4.66 | 13.05 | 4.38 | 12.65 | 7.18 |

| A74 | 120 | 2.72 | 13.63 | 2.68 | 13.15 | 3.33 |

| A37 | 120 | 2.74 | 13.14 | 2.67 | 12.78 | 4.42 |

| A38 | 120 | 3.68 | 13.48 | 3.52 | 13.04 | 5.2 |

| A28 | 120 | 2.7 | 14.37 | 2.6 | 13.85 | 3.15 |

| Distribution | Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Type-III | 156.82 | 162.37 | 0.089 |

| Gumbel | 163.54 | 167.21 | 0.124 |

| Weibull | 161.93 | 166.58 | 0.117 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, G.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, B.; Lai, Y. Research on Wave Environment and Design Parameter Analysis in Offshore Wind Farm Construction. Energies 2026, 19, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010115

Zeng G, Liu Y, Huang X, Wang B, Lai Y. Research on Wave Environment and Design Parameter Analysis in Offshore Wind Farm Construction. Energies. 2026; 19(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Guanming, Yuyan Liu, Xuanjun Huang, Bin Wang, and Yongqing Lai. 2026. "Research on Wave Environment and Design Parameter Analysis in Offshore Wind Farm Construction" Energies 19, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010115

APA StyleZeng, G., Liu, Y., Huang, X., Wang, B., & Lai, Y. (2026). Research on Wave Environment and Design Parameter Analysis in Offshore Wind Farm Construction. Energies, 19(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010115