Perovskite PV-Based Power Management System for CMOS Image Sensor Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework-Solar Cell Models

1.2. Theoretical Framework-Charge Pumps

1.2.1. Charge Pump Operation

1.2.2. Charge Pump Topologies

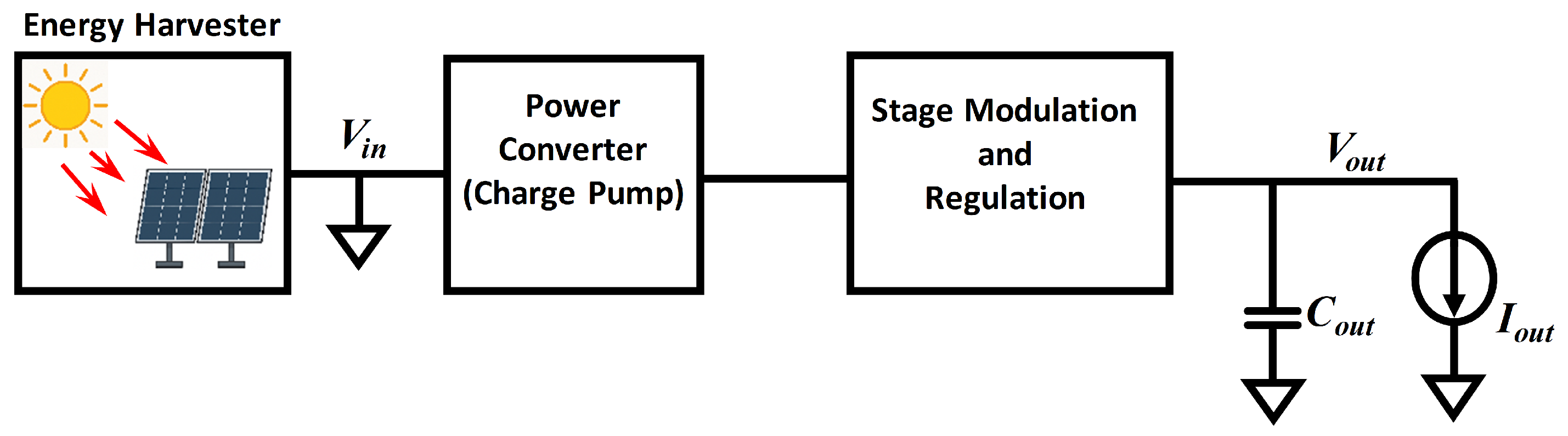

2. System Design

2.1. Solar Cell

2.2. Power Converter

2.3. Clock Generator: Current-Starved Voltage-Controlled Oscillator

2.4. Transmission Gate (TG)-Based 4:1 Multiplexer

3. Method

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.D.; Yoshita, M.; Kopidakis, N.; Bothe, K.; Siefer, G.; Hao, X.; Jiang, J.Y. Solar Cell Efficiency Tables (Version 66). Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2025, 33, 795–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJinno, H.; Shivarudraiah, S.B.; Asbjörn, R.; Vagli, G.; Marcato, T.; Eickemeyer, F.T.; Pfeifer, L.; Yokota, T.; Someya, T.; Shih, C. Indoor Self-Powered Perovskite Optoelectronics with Ultraflexible Monochromatic Light Source. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2304604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, S.O.; Moustafa, A.; Khalid, A.; Ghannam, R. Integration of Capacitive Pressure Sensor-on-Chip with Lead-Free Perovskite Solar Cells for Continuous Health Monitoring. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Demchyshyn, S.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Song, Y.; Hailegnaw, B.; Xu, C.; Yang, Y.; Solomon, S.; Putz, C.; Lehner, L.E.; et al. An autonomous wearable biosensor powered by a perovskite solar cell. Nat. Electron. 2023, 6, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milyutin, D.P.; Parfenova, O.R.; Parfenov, V.A.; Boldyreva, A.G. Temperature-humidity wireless sensor powered by a wide-bandgap perovskite solar cell. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 127, 073902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Kang, J.; Elkhouly, K.; Hamdad, S.; Zhang, X.; Monroy, M.I.P.; Siddik, A.B.; Carolan, P.; Subramaniam, S.; Kuang, Y.; et al. Halide Perovskite Photodiode Integrated CMOS Imager. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 35520–35532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ning, H.; Hu, G.; Li, Y.; Xie, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhuo, C.; Bodepudi, S.C.; Wang, Y.; Yu, B.; et al. A Monolithically Integrated 640 × 512 CMOS-Perovskite Image Sensor. In Proceedings of the European Solid-State Circuits Conference, Bruges, Belgium, 9–12 September 2024; pp. 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Duan, H.; Zeng, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhong, X.; Wu, Z.; Ni, S.; Jiang, Z.; Xie, G.; Lee, J.-Y.; et al. Perovskite retinomorphic image sensor for embodied intelligent vision. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Lew, B.; Srivastava, I.; Liang, Z.; et al. Bioinspired, vertically stacked, and perovskite nanocrystal-enhanced CMOS imaging sensors for resolving UV spectral signatures. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadk3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, A.Y.C.; Hsieh, C.C. A 137 dB Dynamic Range and 0.32 V Self-Powered CMOS Imager With Energy Harvesting Pixels. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2016, 51, 2769–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.H.; Amir, M.F.; Ahmed, K.Z.; Na, T.; Mukhopadhyay, S. A Single-Chip Image Sensor Node with Energy Harvesting from a CMOS Pixel Array. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2017, 64, 2295–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Lajevardi, P.; Wojciechowski, K.; Lang, C.; Murmann, B. An energy harvester using image sensor pixels with cold start and over 96% MPPT efficiency. IEEE Solid State Circuits Lett. 2019, 2, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.T.; Leon-Salas, W.D. An image sensor with joint sensing and energy harvesting functions. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 902–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-T.; Leon-Salas, W.D. High-voltage generation using a CMOS image sensor with dual photo-sensing and energy harvesting capabilities. In Proceedings of the SENSORS, 2013 IEEE, Baltimore, MD, USA, 3–6 November 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadid-Pecht, O.; Hamami, S. CMOS Image Sensors With Self-Powered Generation Capability. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2006, 53, 1210–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenin, S.; Spady, D.; Ivanov, V. A low ripple on-chip charge pump for bootstrapping of the noise-sensistive nodes. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Kos, Greece, 21–24 May 2006; pp. 5319–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanselow, F.; Poongodan, P.; Sakolski, O.; Maurer, L. A New Switching Scheme for High-Voltage Switched Capacitor DC-DC Converter. In Proceedings of the 2021 10th International Conference on Modern Circuits and Systems Technologies, MOCAST 2021, Thessaloniki, Greece, 5–7 July 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, H.; Pokhriyal, M. Integrated Low Power 4-Phase Double Charge Pump Circuit using 45nm Dynamic Threshold Voltage MOSFET (DTMOS). In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Automation and Computational Engineering, ICACE 2018, Greater Noida, India, 3–4 October 2018; pp. 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.H.; Yaseen, M.T. Performance Evaluation of Low-Voltage CMOS Switched-Capacitor Circuit. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Electrical and Electronics Engineering, ICEEE 2021, Antalya, Turkey, 9–11 April 2021; pp. 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Yin, J.; Mak, P.I.; Martins, R.P. A 0.032-mm2 0.15-V Three-Stage Charge-Pump Scheme Using a Differential Bootstrapped Ring-VCO for Energy-Harvesting Applications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2018, 65, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadian, A.; Pourtaherian, A.; Motahari, S. Basic model and governing equation of solar cells used in power and control applications. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition, ECCE 2012, Raleigh, NC, USA, 15–20 September 2012; pp. 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. Evaluating MPPT converter topologies using a Matlab PV Model. J. Electr. Electron. Eng. Aust. 2001, 21, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gow, J.A.; Manning, C.D. Development of a photovoltaic array model for use in power-electronics simulation studies. IEE Proc. Electr. Power Appl. 1999, 146, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballo, A.; Grasso, A.D.; Palumbo, G. Charge Pump Improvement for Energy Harvesting Applications by Node Pre-Charging. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2020, 67, 3312–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.; Alhawari, M.; Mohammad, B.; Saleh, H.; Ismail, M. A Charge Pump Based Power Management Unit with 66%-Efficiency in 65 nm CMOS. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Florence, Italy, 27–30 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballo, A.; Grasso, A.D.; Palumbo, G. A high-performance charge pump topology for very-low-voltage applications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2020, 67, 1304–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, G.; Pappalardo, D. Charge pump circuits: An overview on design strategies and topologies. IEEE Circuits Syst. Mag. 2010, 10, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librado, R.V.A.; Hora, J.A. A 90.9% Efficient 4-phase Interleaved Charge Pump Topology with FBB and Internal Clock Boosting Technique for Energy Harvesting Applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE Region 10 Annual International Conference, Proceedings/TENCON, Hong Kong, China, 1–4 November 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Jiang, Q.; Huang, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. A GaN-Based Hybrid Logic Circuitry With Low Power Consumption and Enhanced Fan-Out Capability. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2025, 72, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B. A Charge-Sharing-Based Half-Bridge Driver Suitable for Any Duty Cycle With No External Component. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2025, 72, 6411–6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidarkhanov, D.; Ren, Z.; Lim, C.-K.; Yelzhanova, Z.; Nigmetova, G.; Taltanova, G.; Baptayev, B.; Liu, F.; Cheung, S.H.; Balanay, M.; et al. Passivation engineering for hysteresis-free mixed perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 215, 110648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Liu, K.; Hu, H.; Gao, X.G.Y.; Fong, P.W.K.; Liang, Q.; Tang, H.; Huang, J.; Zhang, H.; Qin, M.; et al. Room-temperature multiple ligands-tailored SnO2 quantum dots endow in situ dual-interface binding for upscaling efficient perovskite photovoltaics with high Voc. Light Sci. Appl. 2021, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, A.; Ren, Z.; Hu, H.; Fong, P.W.K.; Shen, Q.; Cheung, S.H.; Qin, P.; Lee, J.-W.; Djurišić, A.B.; So, S.K.; et al. A Cryogenic process for antisolvent-free high-performance perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1804402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylnev, M.; Nishikubo, R.; Ishiwari, F.; Wakamiya, A.; Saeki, A. Performance Boost by Dark Electro Treatment in MACl-Added FAPbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2401902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhu, G.; Shao, Y. Improving the power conversion efficiency of perovskite solar cells by adding carbon quantum dots. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 2937–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, G.; Yang, Z.; Dong, T.; Mendes, P.; Wen, Y.; Li, P. 0.13 μm Low-Power CMOS Current Starved VCO for Vibration Energy Harvesters. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2021, 68, 2167–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, N.; Kumar, V.; Yadav, S.; Nath, V. Design and Analysis of a Low Power Current Starved VCO for ISM band Application. Int. J. Microsyst. IoT 2023, 1, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Reverse Scan | Forward Scan |

|---|---|---|

| Open Circuit Voltage, | 1.14 | 1.14 |

| Short Circuit Current, | 1.24 | 1.24 |

| Current Density, | 20.61 | 20.68 |

| Maximum Current, | 0.99 | 1.04 |

| Maximum Voltage, | 0.83 | 0.85 |

| Maximum Power, | 0.82 | 0.88 |

| Fill Factor (%) | 58.13 | 62.22 |

| Efficiency (%) | 13.64 | 14.63 |

| Topology | Output Voltage, | Output Current, | Ripple Voltage, | Leakage Current, |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCP | 3.713 | 1.273 | 72.735 | 6.695 |

| DBCP | 3.711 | 1.581 | 57.009 | 13.099 |

| Select 1 (S1) | Select 0 (S0) | Selected Output |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | A0 |

| 0 | 1 | A1 |

| 1 | 0 | A2 |

| 1 | 1 | A3 |

| Circuit Block | Typical Voltage Rating (V) |

|---|---|

| Image sensor active pixel array | 2.8–3.3 |

| Image sensor analog circuitry (CDS/column amplifiers) | |

| ADC (peripheral/column-parallel)-Analog | |

| Digital control/sequencer | 1.2–1.8 |

| Timing generator/clock driver | 1.8–3.3 |

| Voltage references/on-chip regulators | 1.2/1.8/2.8/3.3 |

| Image Signal Processor (ISP) if integrated | 1.2–1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Onyejegbu, E.; Aidarkhanov, D.; Ng, A.; Marzuki, A.; Hashmi, M.; Ukaegbu, I.A. Perovskite PV-Based Power Management System for CMOS Image Sensor Applications. Energies 2026, 19, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010100

Onyejegbu E, Aidarkhanov D, Ng A, Marzuki A, Hashmi M, Ukaegbu IA. Perovskite PV-Based Power Management System for CMOS Image Sensor Applications. Energies. 2026; 19(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnyejegbu, Elochukwu, Damir Aidarkhanov, Annie Ng, Arjuna Marzuki, Mohammad Hashmi, and Ikechi A. Ukaegbu. 2026. "Perovskite PV-Based Power Management System for CMOS Image Sensor Applications" Energies 19, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010100

APA StyleOnyejegbu, E., Aidarkhanov, D., Ng, A., Marzuki, A., Hashmi, M., & Ukaegbu, I. A. (2026). Perovskite PV-Based Power Management System for CMOS Image Sensor Applications. Energies, 19(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010100