Quantifying Grid-Forming Requirement for Electrolyzer-Based Hydrogen Production in Off-Grid Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Analysis of GFM Control Principles and Strategies for Off-Grid ReP2H Systems

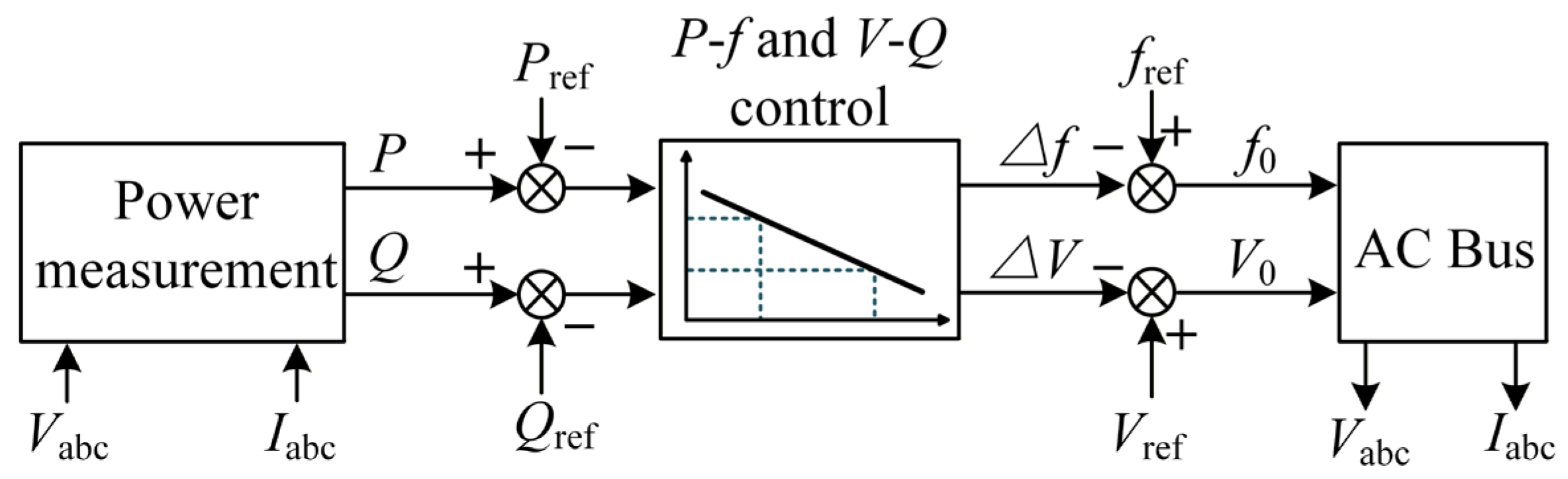

2.1. Principles of Frequency and Voltage Control in Off-Grid ReP2H Systems

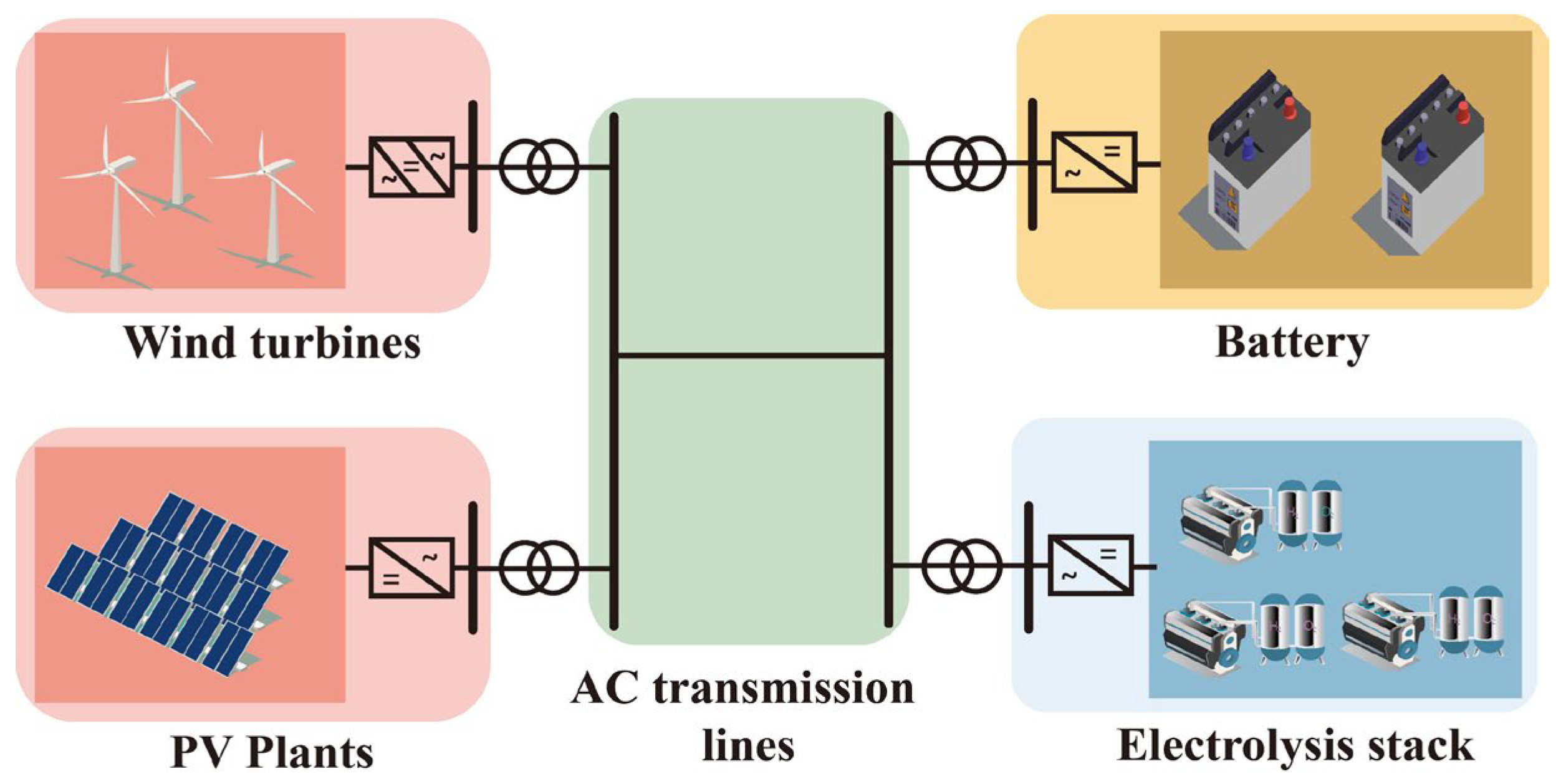

2.2. Solution Based on a Centralized Grid-Forming BESS

2.3. Solution Based on Grid-Forming Electrolyzers

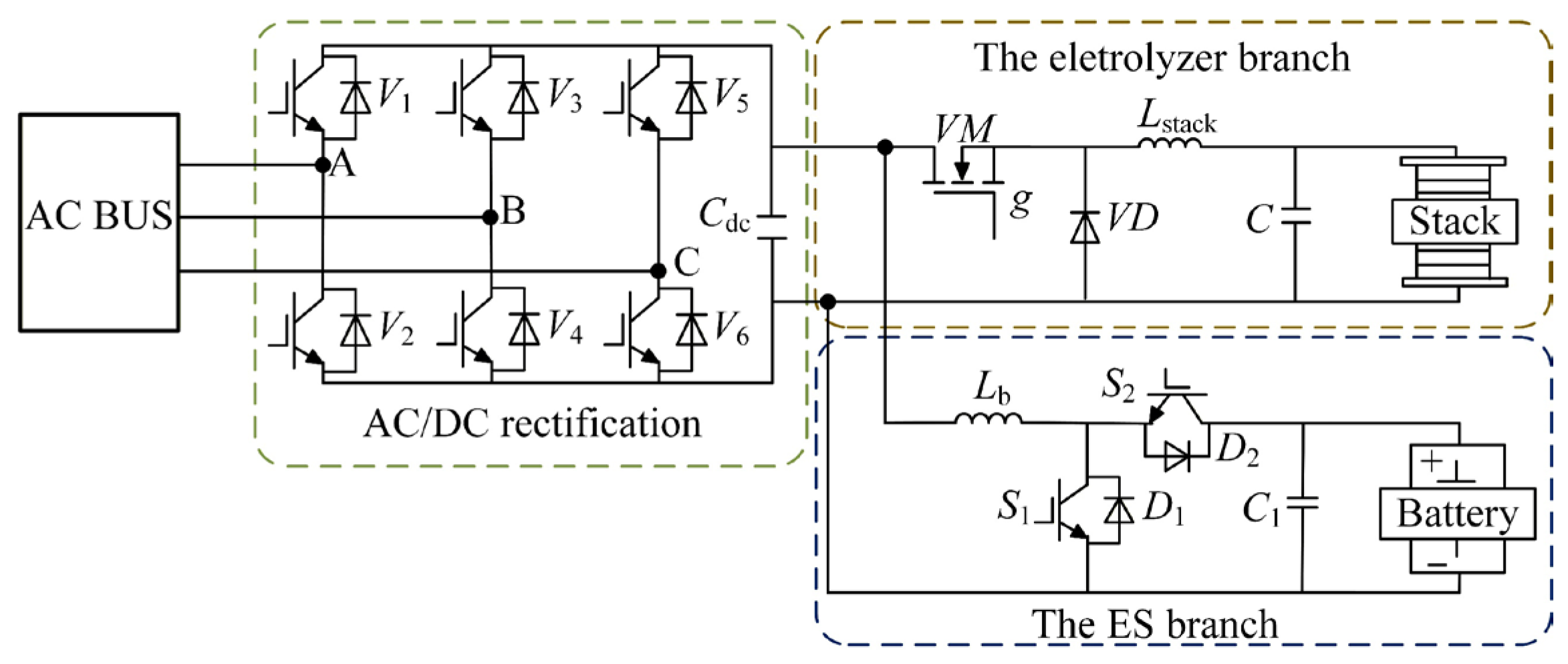

2.4. Composite Multi-Source Coordinated Grid-Forming Strategy

3. Modeling and Optimization of GFM Capability in Off-Grid ReP2H Systems

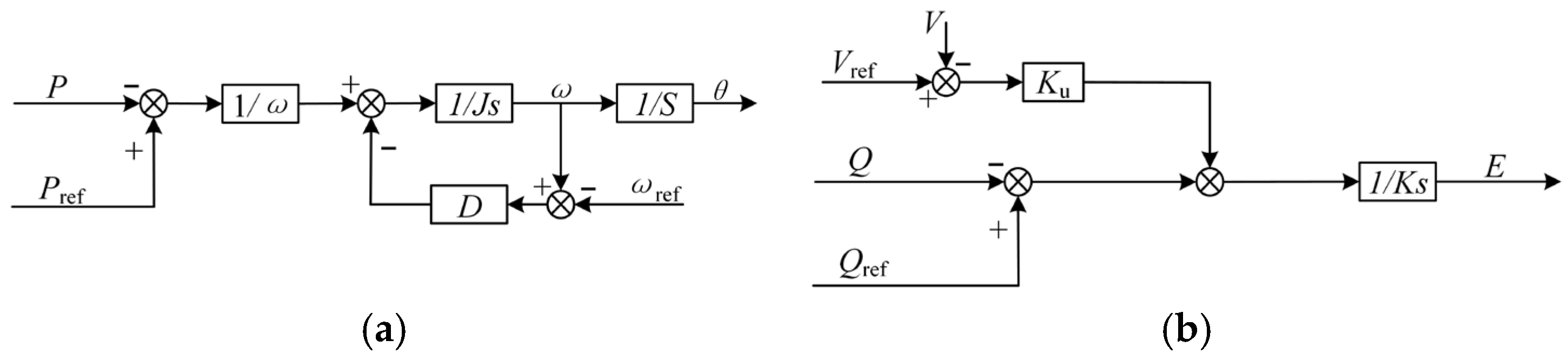

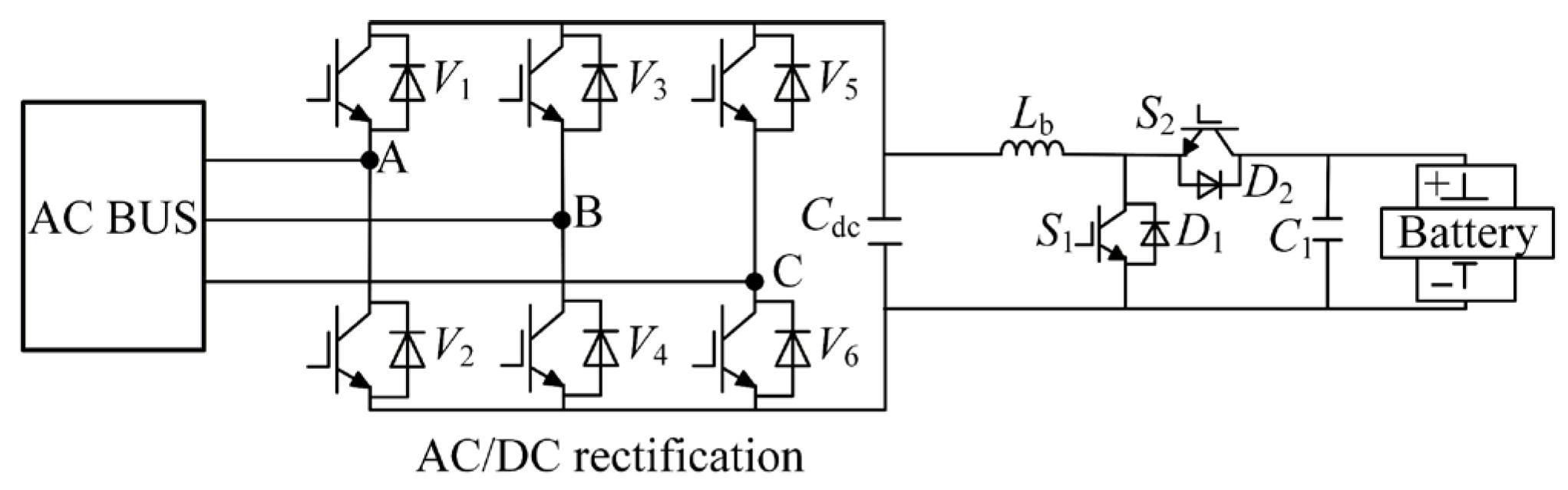

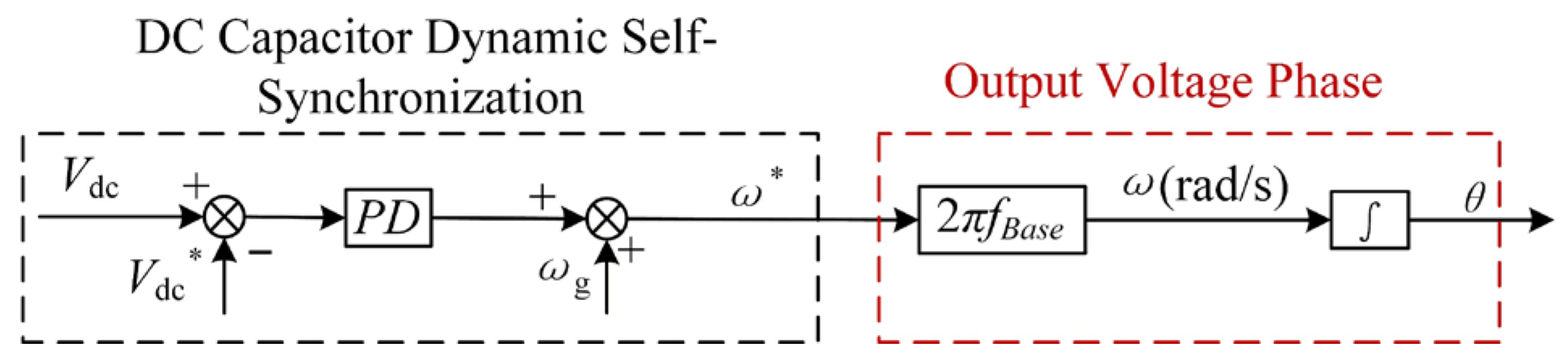

3.1. Modeling of Centralized BESS Grid-Forming Control

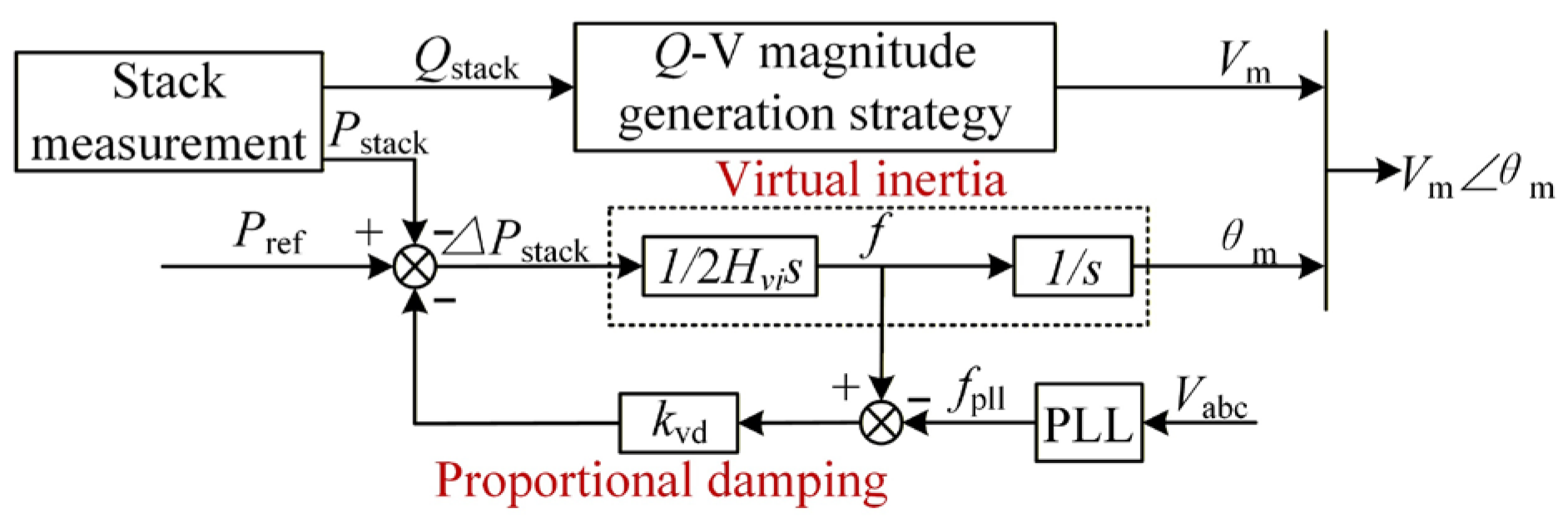

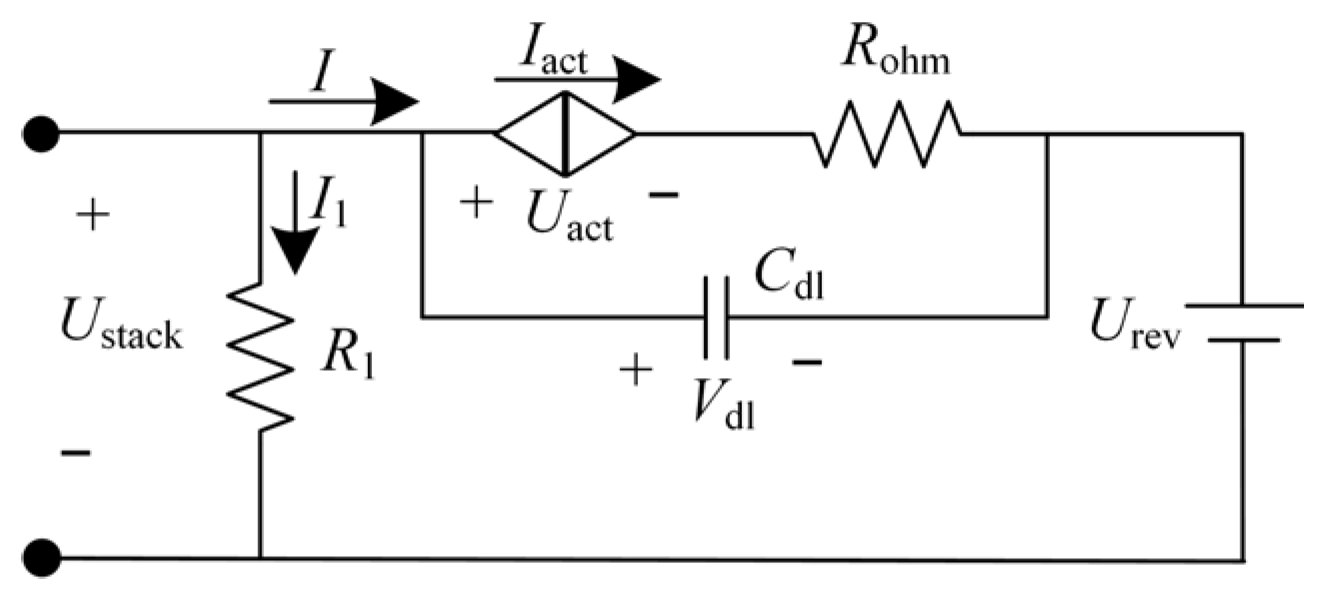

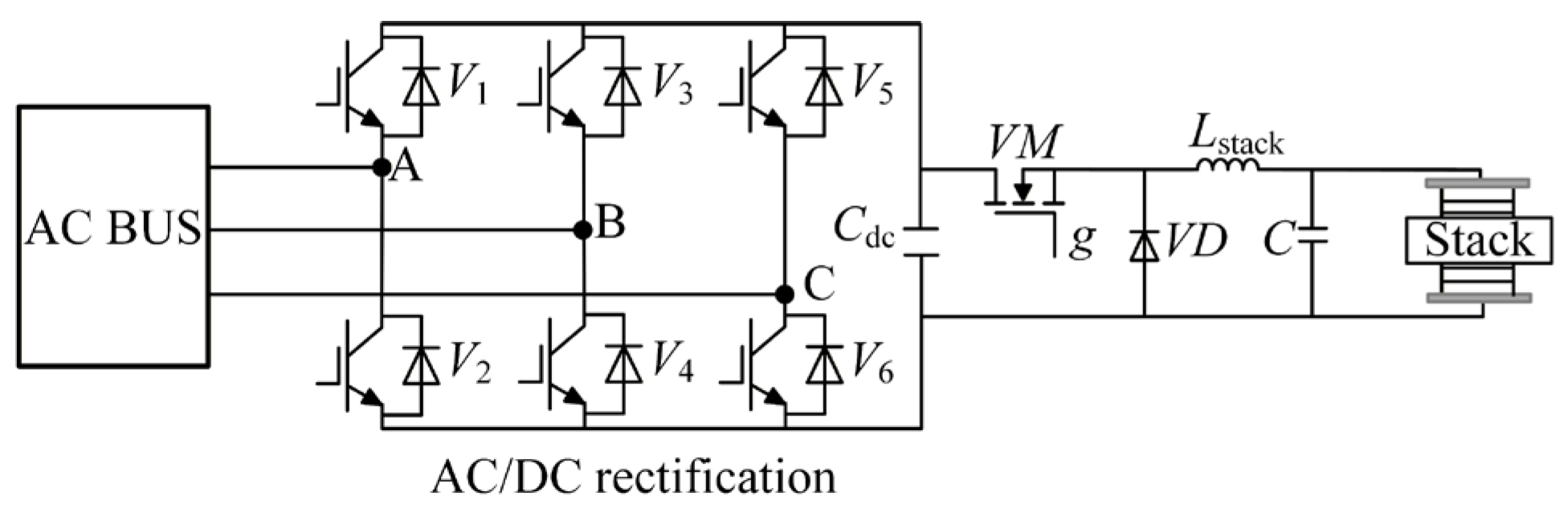

3.2. Modeling of Electrolyzer Grid-Forming Control

3.3. Modeling of Composite Multi-Source Coordinated Grid-Forming Control

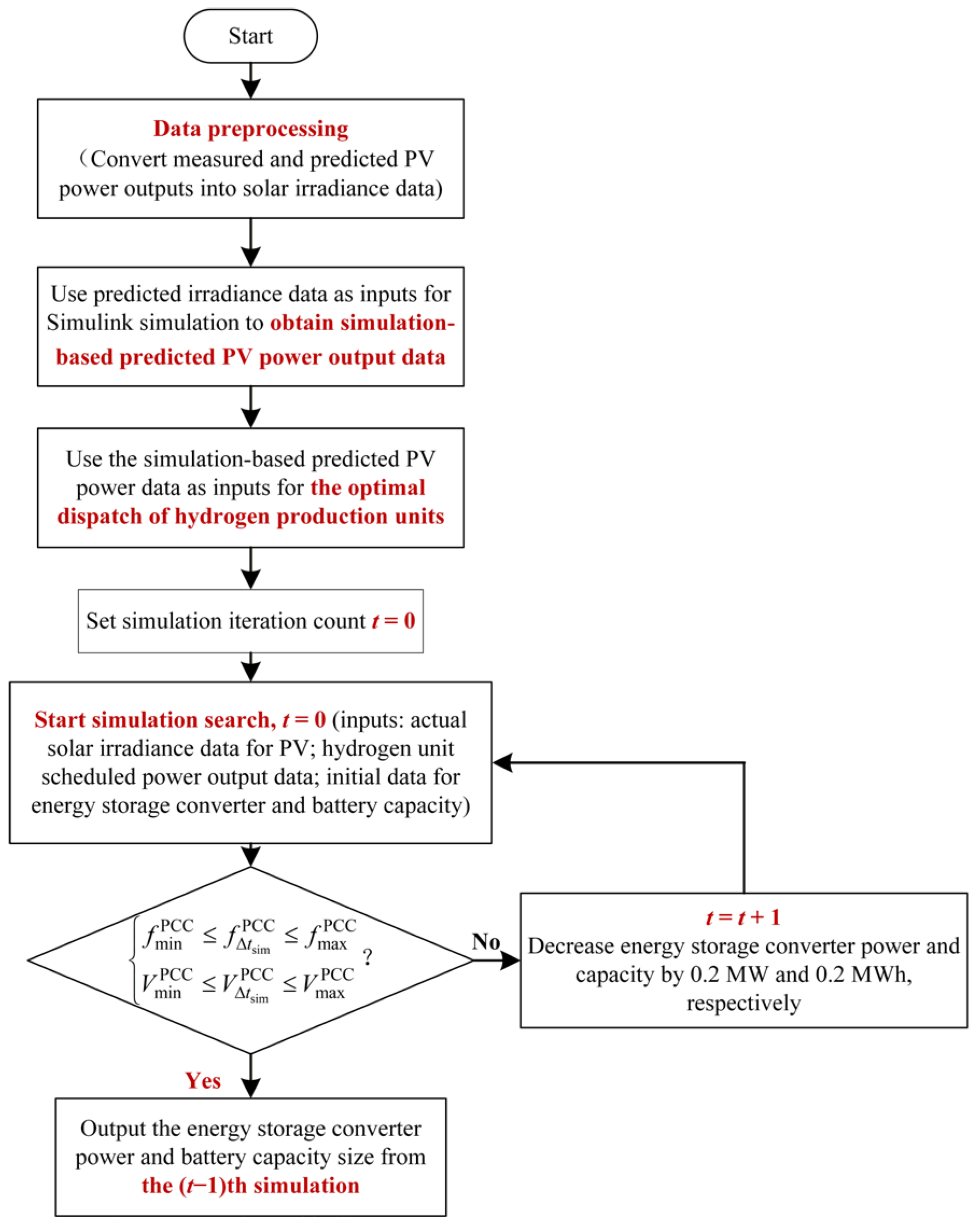

3.4. Optimal Sizing Principles and Feasibility Constraints

4. Comparative Verification Analysis and Optimized Sizing of GFM Strategies

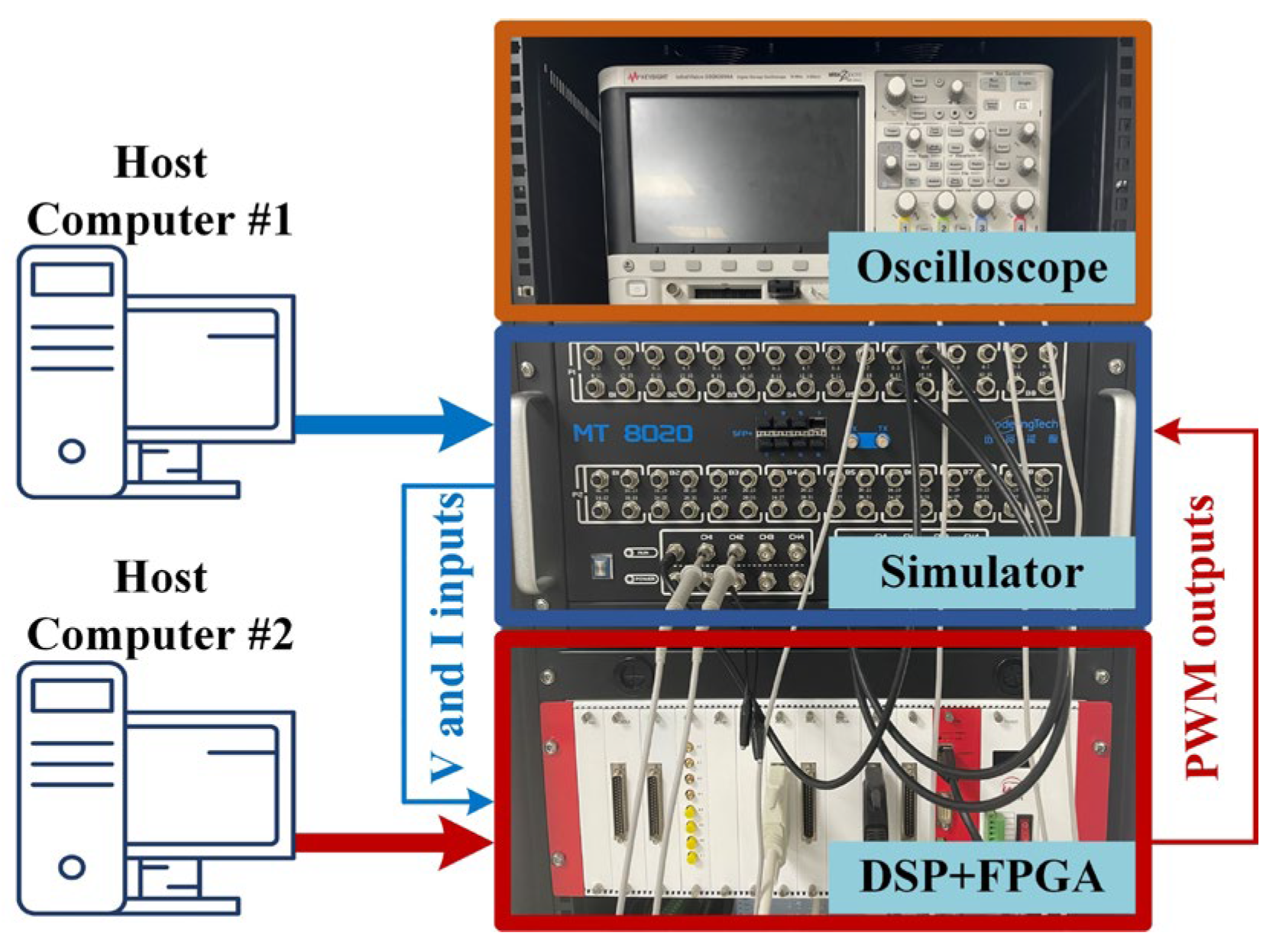

4.1. Simulation Setup and Verification Platform

Electrolyzer Materials and Specifications

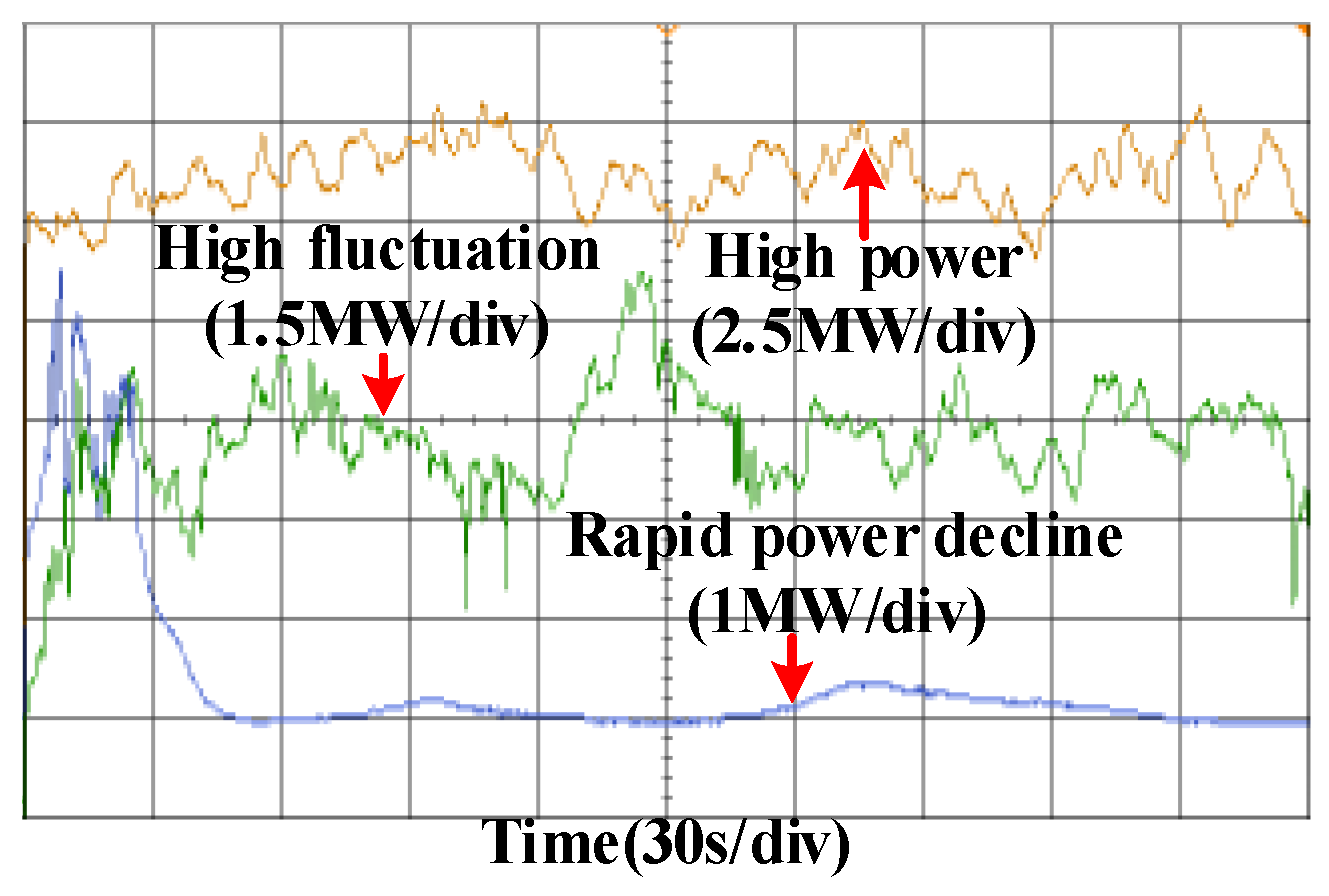

4.2. Comparative Performance of the GFM Strategies

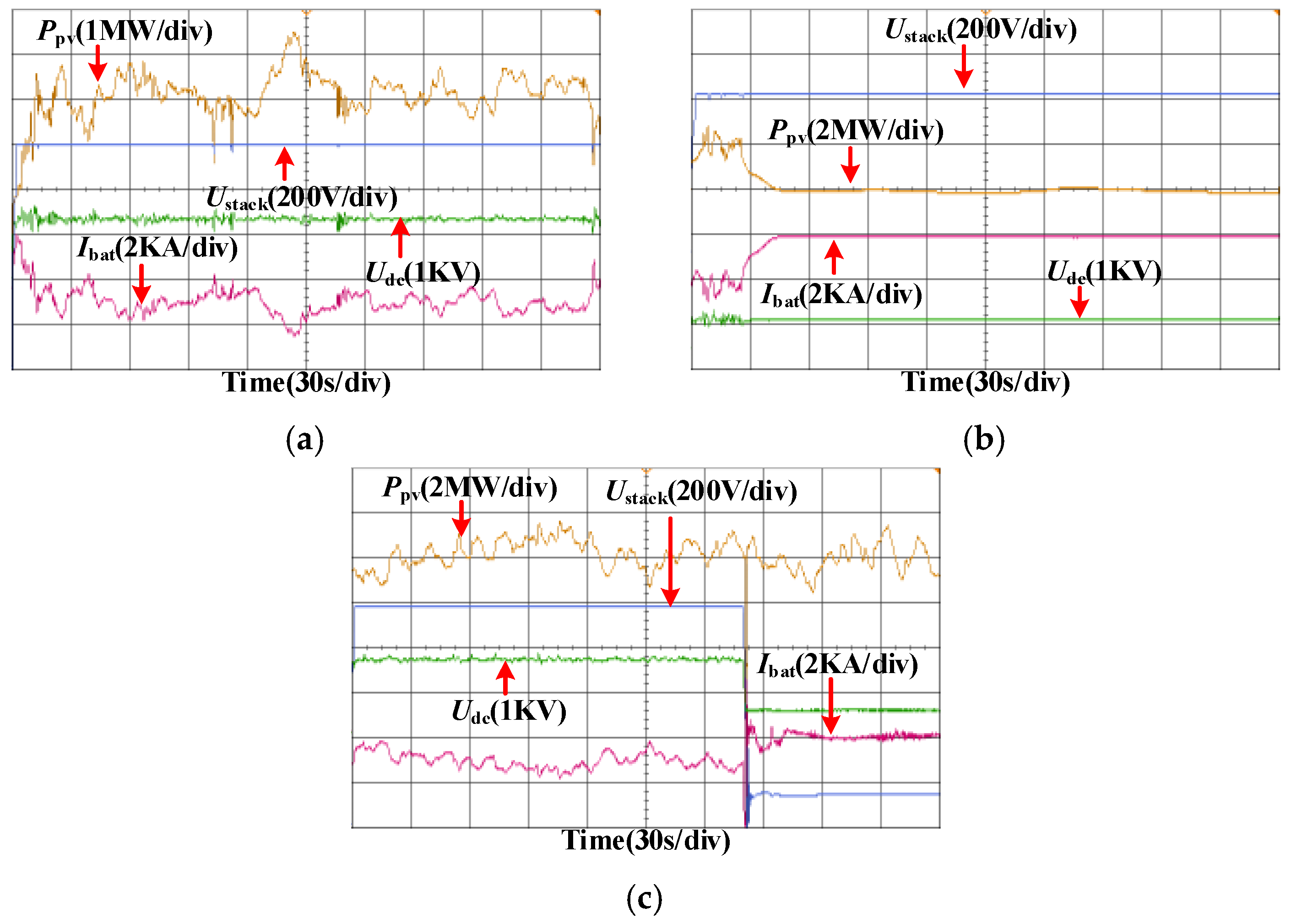

4.2.1. Centralized BESS-Based GFM Solution

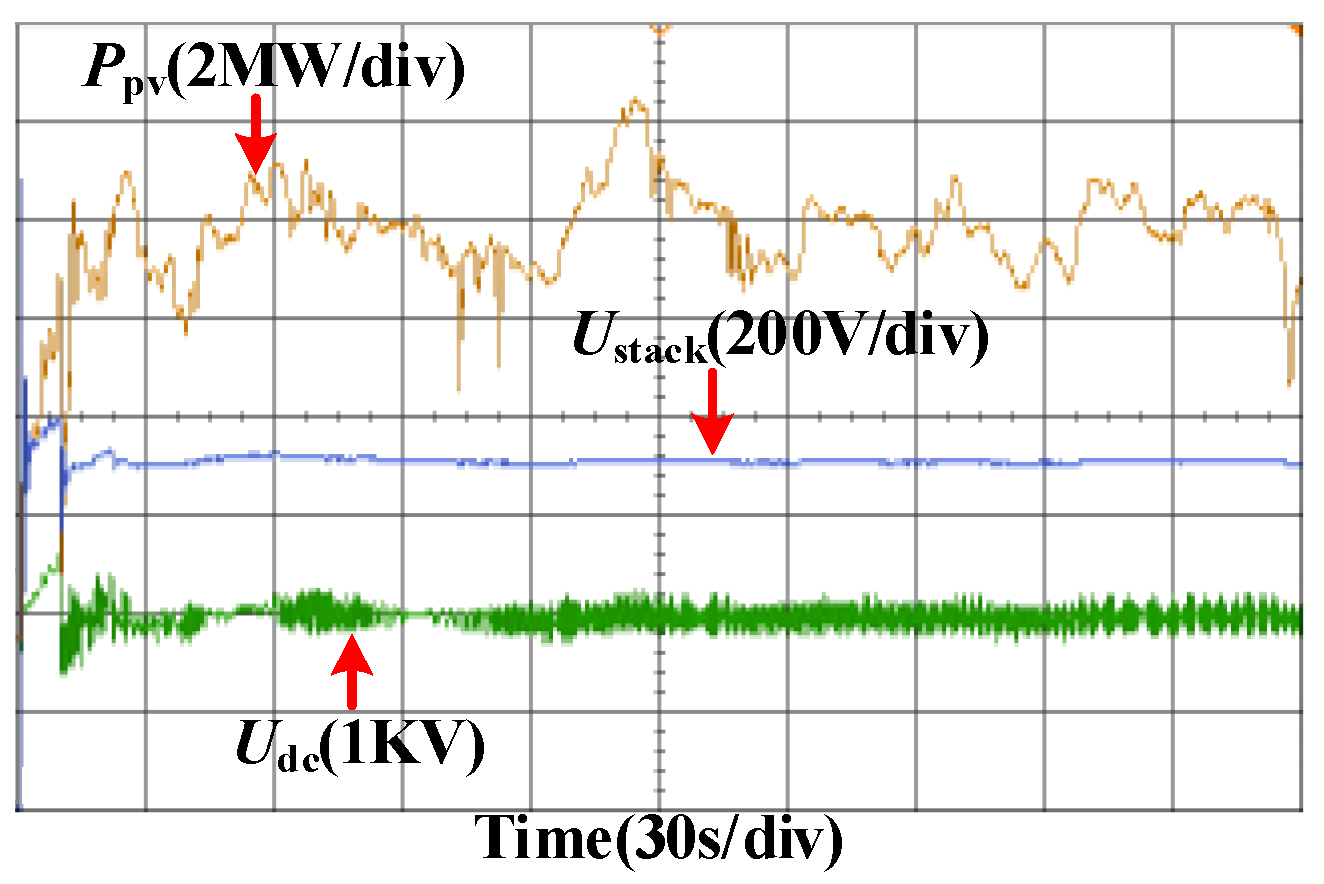

4.2.2. GFM Electrolyzer-Based Solution

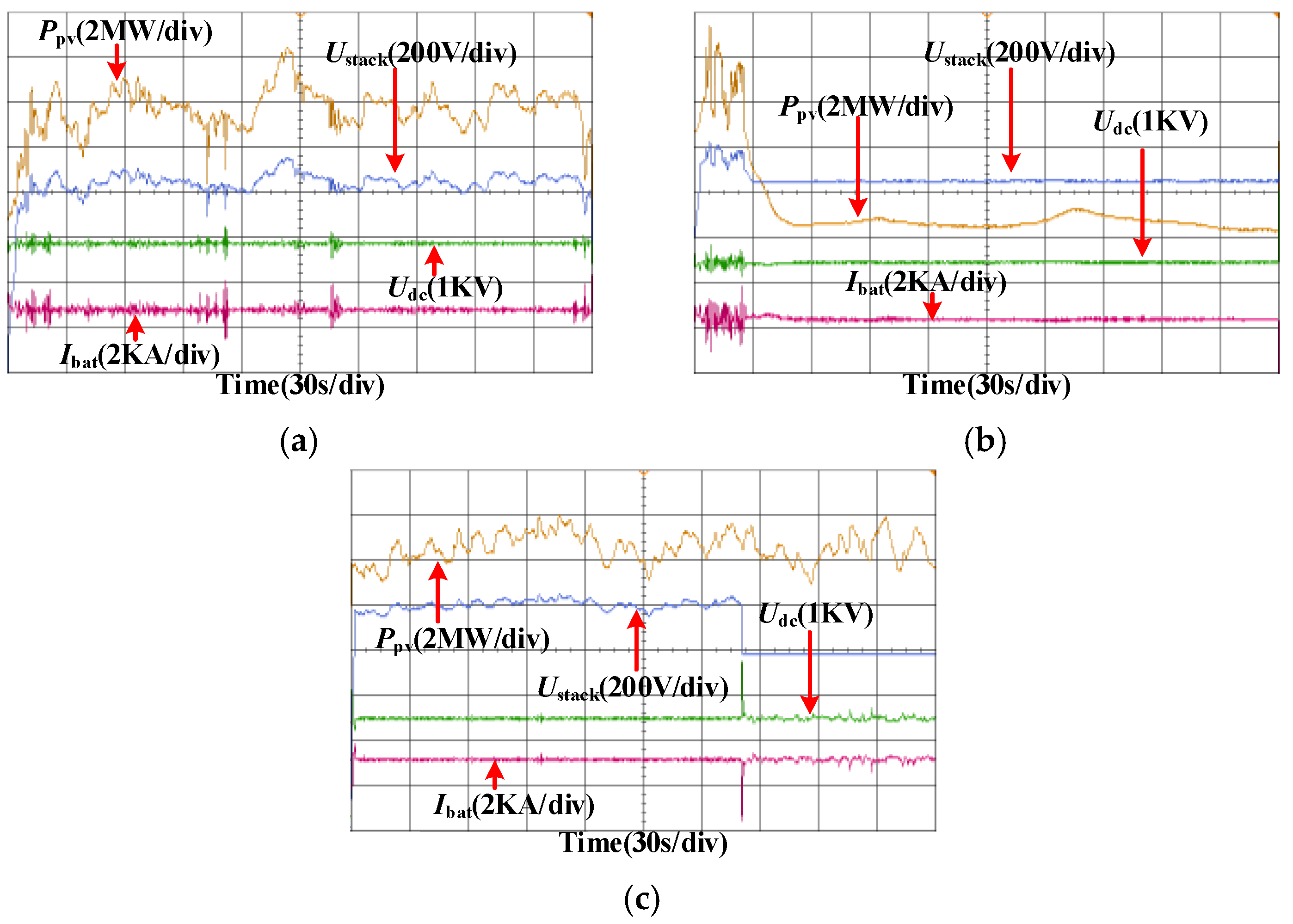

4.2.3. Composite Multi-Source Coordinated GFM Solution

4.3. Optimal ES–HE Capacity Ratio

4.3.1. ES Capacity Requirements

4.3.2. LCOH and Life-Cycle Cost Analysis

5. Conclusions

- The centralized GFM BESS-based approach is straightforward to deploy and commonly used in practice but is vulnerable to single-point failures. Simulations show that it maintains voltage-frequency stability as summarized in Table 3 but requires the largest ES capacity among the three strategies, resulting in an LCOH of 33.212 CNY/kg.

- The GFM electrolyzer-based approach, i.e., using the electrolyzer and VSM dynamics alone for V/F control, simplifies system architecture and reduces ES needs. However, its stability margin is insufficient for sustained hydrogen production and maintaining production efficiency under long-term fluctuations remains an open challenge.

- The composite multi-source coordinated GFM solution provides strong V/F support and robustness while reducing ES capacity and lowering the LCOH to 25.458 CNY/kg. Its drawback lies in the higher complexity of coordinated control and the increased converter capacity required, which partially offsets its economic advantage.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ReP2H | Renewable Energy-to-Hydrogen |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| EDL | Electrical Double Layer |

| HIL | Hardware-in-the-Loop |

| LCOH | Levelized Cost of Hydrogen |

| LCC | Life-cycle Cost |

| CRF | Capital Recovery Factor |

| EENS | Expected Energy not Supplied |

| GFM | Grid-Forming |

| GFL | Grid-Following |

| V/F | Voltage/Frequency |

| PCC | Point of Common Coupling |

| VSM | Virtual Synchronous Machine |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| HE | Hydrogen Electrolyzer |

| AEL | Alkaline Electrolyzer |

| PEMEL | Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer |

| ES | Energy Storage |

References

- Blaabjerg, F.; Chen, Z.; Kjaer, S. Power electronics as efficient interface in dispersed power generation systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2004, 19, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Cui, Y.; Liu, N. The path towards sustainable energy. Nat. Mater. 2016, 16, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeje, S.O.; Marazani, T.; Obiko, J.O.; Shongwe, M.B. Advancing the Hydrogen Production Economy: A Comprehensive Review of Technologies, Sustainability, and Future Prospects. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 78, 642–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koponen, J.; Ruuskanen, V.; Kosonen, A.; Niemelä, M.; Ahola, J. Effect of converter topology on the specific energy consumption of alkaline water electrolyzers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 6171–6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impemba, S.; Provinciali, G.; Filippi, J.; Caporali, S.; Muzzi, B.; Casini, A.; Caporali, M. Tightly Interfaced Cu2O with In2O3 to Promote Hydrogen Evolution in Presence of Biomass-Derived Alcohols. ChemNanoMat 2024, 10, e202400459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impemba, S.; Provinciali, G.; Filippi, J.; Salvatici, C.; Berretti, E.; Caporali, S.; Banchelli, M.; Caporali, M. Engineering the Heterojunction between TiO2 and In2O3 for Improving the Solar-Driven Hydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 63, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diglio, M.; Contento, I.; Impemba, S.; Berretti, E.; Della Sala, P.; Oliva, G.; Naddeo, V.; Caporali, S.; Primo, A.; Talotta, C.; et al. Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid Decomposition Promoted by Gold Nanoparticles Supported on a Porous Polymer Matrix. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 14320–14329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidas, L.; Castro, R. Recent Developments on Hydrogen Production Technologies: State-of-the-Art Review with a Focus on Green-Electrolysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Qiu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, S.; Zang, T.; Zhou, B.; Yu, Z.; Lin, J. Exploring the optimal size of grid-forming energy storage in an off-grid renewable P2H system under multi-timescale Energy Management. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.05086. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Wu, C.; Qiu, Y.; Zang, T.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, Y. Optimal scheduling of multi-electrolyzer power-to-hydrogen clusters considering the temporal uncertainty of photovoltaic power. Electr. Power Constr. 2023, 44, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zou, J.; Long, R.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W. Variable period sequence control strategy for an off-grid photovoltaic-PEM electrolyzer hydrogen generation system. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 119074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhou, B.; Li, J.; Yang, B.; Lin, J. Scheduling multiple industrial electrolyzers in renewable P2H systems: A coordinated active-reactive power management method. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2025, 16, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Xu, L.; Gu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Zhou, B. Optimal investment portfolio of thyristor-and IGBT-based electrolysis rectifiers in utility-scale renewable P2H systems. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy, 2025; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, S.K.; Shah, S.S.; Singh, B.N.; Bhattacharya, S. Vector-based open-circuit fault diagnosis technique for a three-phase DAB converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 8207–8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Meng, J.; Xu, Z.; Xie, H.; Jia, Z.; Quan, H. Modeling and simulation of photovoltaic off-grid hydrogen production system. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Environmental Science and Green Energy (ICESGE), Shenyang, China, 9–11 December 2022; pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babay, M.-A.; Adar, M.; Chebak, A.; Mabrouki, M. Forecasting green hydrogen production: An assessment of renewable energy systems using deep learning and statistical methods. Fuel 2025, 381, 133496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasi, B.; Mazzoni, S. Renewable hydrogen energy communities’ layouts towards off-grid operation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 291, 117293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Ali, S.Q.; Joos, G.; Bouffard, F. Virtual synchronous machine control for low-inertia power system considering energy storage limitation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Baltimore, MD, USA, 29 September–3 October 2019; pp. 6021–6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozein, M.G.; De Corato, A.M.; Mancarella, P. Virtual inertia response and frequency control ancillary services from hydrogen electrolyzers. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 2447–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuinema, B.; Adabi, E.; Ayivor, P.; Garcia Suarez, V.; Liu, L.; Perilla, A.; Ahmad, Z.; Rueda Torres, J.; van der Meijden, M.; Palensky, P. Modelling of large-sized electrolysers for real-time simulation and study of the possibility of frequency support by electrolysers. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 1985–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Qi, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Y. A Coordinated control strategy for a coupled wind power and energy storage system for hydrogen production. Energies 2025, 18, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agredano-Torres, M.; Zhang, M.; Söder, L.; Xu, Q. Decentralized dynamic power sharing control for frequency regulation using hybrid hydrogen electrolyzer systems. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2024, 15, 1847–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agredano-Torres, M.; Xu, Q. Decentralized power management of hybrid hydrogen electrolyzer-supercapacitor systems for frequency regulation of low-inertia Grids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 8072–8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Zhao, W.; Stroe, D.-I.; Iov, F.; Munk-Nielsen, S. Enabling LVRT compliance of electrolyzer systems using energy storage technologies. Batteries 2023, 9, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Teng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ding, F.; Wang, N.; Guo, X.; Hua, C. Fault Diagnosis and fault-tolerant operation strategy for triple-port hydrogen production system. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 11526–11536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, S.D.; Dozein, M.G.; Lacerda, V.A.; Mañe, M.C.; Prieto-Araujo, E.; Mancarella, P.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O. Grid-forming services from hydrogen electrolyzers. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2023, 14, 2205–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaïci, W.; Entchev, E.; Annuk, A.; Longo, M. Optimal design and cost analysis of microgrid hybrid renewable energy systems with hydrogen production and storage and battery. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2023 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/ICPS Europe), Madrid, Spain, 6–9 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Huang, F.; Zhu, Z. Dynamic power balancing control method for energy storage DC/DC parallel supply system with low-frequency pulsed load. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 5766–5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, S.; Song, L.; Yang, F.; Ouyang, M.; Shen, X. Exploration of the configuration and operation rule of the multi-electrolyzers hybrid system of large-scale alkaline water hydrogen production system. Appl. Energy 2023, 331, 120413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xun, Q.; Liserre, M.; Yang, H. Energy management of electric-hydrogen hybrid energy storage systems in photovoltaic microgrids. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 80, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, L.; Lin, J.; Qi, R.; Song, Y. Low-frequency experimental method for measuring the electric double-layer capacitances of multi-cell electrolysis stacks based on equivalent circuit model. J. Power Sources 2023, 579, 233263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Lin, J.; Zhang, M.; Sha, L.; Yang, B.; Liu, F.; Song, Y. Power controller design for electrolysis systems with DC/DC interface supporting fast dynamic operation: A model-based and experimental study. Appl. Energy 2025, 378, 124848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Li, K.; Zeng, L.; Xie, L.; Cheng, M.; He, W. A multi-state rotational control strategy for hydrogen production systems based on hybrid electrolyzers. Energies 2025, 18, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, M.; Qi, R.; Lin, J. Design of a photovoltaic-to-hydrogen system for efficiency and safety under varying conditions. J. Power Sources 2025, 638, 236487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Kong, H.; Wang, H.; Guo, X. Impedance modeling and stability analysis of electrolysis system for hydrogen production under weak grid. Fuel 2024, 374, 132403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, H.; Du, S.; Li, B. A Current ripple suppression strategy of TAB for photovoltaic hydrogen production. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 3758–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M.; Xia, Q.; Tan, C.W.; Li, G. Incentivizing frequency provision of power-to-hydrogen toward grid resiliency enhancement. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 9370–9381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, Z.; Chen, L. Hierarchical control strategy for electric-hydrogen coupled system considering the power distribution of multi-stack fuel cells. Electr. Power Constr. 2024, 45, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, S.; Zang, T.; Zhou, B. Flexibility assessment and aggregation of alkaline electrolyzers considering dynamic process constraints for energy management of renewable power-to-hydrogen systems. Renew. Energy 2024, 235, 121261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xin, H.; Wang, Z.; Wu, K.; Wang, H.; Hu, J.; Lu, C. A Virtual Synchronous Control for Voltage-Source Converters Utilizing Dynamics of DC-Link Capacitor to Realize Self-Synchronization. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2017, 5, 1565–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | System Configuration | Energy Support Provision | Real-Time Energy Balance Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wind | PV | Off-Grid | On-Grid | ES | HE | |||

| 2024 [9] | ● | ● | ● | - | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| 2023 [10] | - | ● | ● | - | - | ● | - | ● |

| 2023 [11] | - | ● | ● | - | - | ● | - | ● |

| 2022 [15] | - | ● | ● | - | - | ● | - | - |

| 2019 [18] | ● | - | ● | - | ● | - | ● | ● |

| 2023 [19] | - | - | - | ● | - | ● | ● | - |

| 2020 [20] | - | - | - | ● | - | ● | ● | - |

| 2025 [21] | ● | - | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| 2024 [22] | - | - | - | ● | - | ● | - | ● |

| 2025 [23] | - | ● | ● | ● | ● | - | ● | |

| 2025 [25] | - | - | ● | - | ●- | ● | - | ● |

| 2023 [26] | ● | ● | ● | - | ● | ● | ● | - |

| 2023 [27] | - | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| 2024 [28] | ● | ● | ● | - | ● | - | ● | ● |

| 2023 [29] | - | - | - | ● | - | ● | - | ● |

| 2024 [30] | - | ● | ● | - | - | ● | - | ● |

| 2023 [31] | - | - | - | ● | - | ● | ● | - |

| 2025 [32] | ● | ● | ● | ● | - | ● | ● | ● |

| 2025 [33] | ● | - | ● | - | - | ● | ● | ● |

| 2024 [35] | ● | ● | - | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| 2025 [36] | - | ● | ● | - | - | ● | ● | ● |

| 2023 [37] | - | - | - | ● | - | ● | ● | - |

| 2024 [38] | - | ● | ● | - | - | ● | - | ● |

| Stack | Value | Unit | Circuit | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cdl | 0.02 | F/cm2 | Vdc | 1000 | V |

| Urev | 1.228 | V | Cdc | 50 | mF |

| Rohm | 1.1918 | Ω/cm2 | fref | 50 | Hz |

| Iexchange | 0.0015 | A/cm2 | Lbuck | 25 | mH |

| Ncell | 445 | - | Vacref | 35/1 | kV |

| area | 15,000 | cm2 | Vdroop | 0.9697 | V |

| Kact | 0.1521 | - | Redge | 0.0009 | Ω |

| Eon | 40 | mJ | |||

| Eoff | 100 | mJ | |||

| Ileak | 5 | mA |

| Type | Voltage Range (p.u.) | Frequency Deviation (Hz) | ES Proportion (%) | LCOH (CNY/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFM BESS strategy | ±6–±12% | ±0.6–±1.1 | 36 | 33.212 |

| GFM electrolyzer strategy | ±9.5–±15% | ±1.1–±1.9 | 20 | 29.750 |

| Composite multi-source coordinated GFM strategy | ±3–±5% | ±0.3–±0.5 | 16 | 25.458 |

| Strategy | Es Capacity Ratio (%) | Max Frequency Deviation (Hz) | Max Voltage Deviation (V) | Stability Check |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFM BESS strategy | 30% | ±1.53 | ±14% | Fail |

| 34% | ±1.15 | ±12.5% | Fail | |

| 36% | ±1.08 | ±12% | Pass | |

| 40% | ±0.92 | ±10% | Pass | |

| GFM electrolyzer strategy | 16% | ±2.15 | ±18% | Fail |

| 18% | ±1.35 | ±16.5% | Fail | |

| 20% | ±1.10 | ±15% | Pass | |

| 22% | ±0.85 | ±12.5% | Pass | |

| Composite multi-source coordinated GFM strategy | 12% | ±0.85 | ±8% | Fail |

| 14% | ±0.62 | ±6% | Fail | |

| 16% | ±0.48 | ±5% | Pass | |

| 18% | ±0.40 | ±4.7% | Pass |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, L.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, S. Quantifying Grid-Forming Requirement for Electrolyzer-Based Hydrogen Production in Off-Grid Systems. Energies 2025, 18, 6440. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246440

Zhou L, Zhang N, Zhou Y, Qiu Y, Chen S. Quantifying Grid-Forming Requirement for Electrolyzer-Based Hydrogen Production in Off-Grid Systems. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6440. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246440

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Lei, Ningbo Zhang, Yi Zhou, Yiwei Qiu, and Shi Chen. 2025. "Quantifying Grid-Forming Requirement for Electrolyzer-Based Hydrogen Production in Off-Grid Systems" Energies 18, no. 24: 6440. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246440

APA StyleZhou, L., Zhang, N., Zhou, Y., Qiu, Y., & Chen, S. (2025). Quantifying Grid-Forming Requirement for Electrolyzer-Based Hydrogen Production in Off-Grid Systems. Energies, 18(24), 6440. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246440