1. Introduction

Global building energy consumption is rising annually; this is a worrying trend, given that buildings are responsible for roughly 40% of global CO

2 emissions. Numerous strategies have been suggested to improve energy use [

1], including integrating renewable energy sources for cleaner energy utilization [

2,

3]. Concepts like smart buildings [

4], green buildings [

5], and net-zero buildings [

6] offer frameworks for boosting energy efficiency and sustainable energy adoption. With the proliferation of Internet-of-Things (IoT) sensors in buildings, researchers are increasingly exploring data-driven solutions. AI solutions have already demonstrated energy savings of around 38% in real-world building applications [

7]. These data-driven approaches, encompassing both traditional statistical methods and machine learning techniques [

8,

9], largely concentrate on optimizing energy load forecasting.

While distributed training is possible for traditional machine learning algorithms like k-nearest neighbor, support vector machines, Bayesian networks, and decision trees, it usually requires sharing raw data, which can compromise user privacy [

10]. To address privacy concerns in machine learning, federated learning has emerged as a decentralized framework [

11,

12,

13]. It allows multiple clients to collaboratively train a model while keeping their local data private [

14]. Each client trains a model locally on their own data and only shares model updates with a central server [

15]. The server then aggregates these updates to refine the global model, enabling collaborative learning without compromising data privacy [

16]. Federated learning (FL) is a versatile framework with applications across diverse industries, leveraging its decentralized architecture to address critical challenges related to data privacy [

12]. In healthcare, FL enables collaborative model training for disease diagnosis, allowing hospitals and research institutions to share model updates while safeguarding sensitive patient data [

17]. In finance, FL facilitates the development of more robust fraud detection models by enabling data sharing across financial institutions while maintaining customer privacy [

13]. The automotive industry can leverage FL for the collaborative development of self-driving algorithms, enabling manufacturers to share driving data without revealing proprietary information [

18].

While the existing building energy forecasting methods are effective, two areas offer potential for further improvement. First, most studies develop individual models for each building, overlooking the potential benefits of collaboration and shared data resources. Federated learning (FL), a privacy-preserving distributed approach, has recently gained significant attention and has seen several applications in the energy sector. For example, FL has been used for probabilistic solar generation decomposition [

19], building heating load forecasting [

20], electricity consumption pattern extraction via clustering [

21], distributed voltage control in power networks using reinforcement learning [

22], and privacy-preserving voltage forecasting with differential privacy [

23]. Additionally, some of the review papers subsequently introduce FL and its variants, including horizontal, vertical, transfer, cross-device, and cross-silo FL, highlighting the crucial role of encryption mechanisms and addressing the associated challenges that have been published [

24]. Traditional machine learning approaches for building energy analysis typically rely on centralized learning with a single dataset, neglecting data privacy and potential data scarcity. Furthermore, the varying energy consumption patterns across different buildings make it difficult to train a robust, generalized model. While personalized federated learning can partially address both data privacy and heterogeneity, its application to building energy analytics remains largely unexplored. In addition to leveraging existing personalized federated learning algorithms, a novel deep learning model based on a mixture of experts to further enhance personalization and handle the diverse data distributions observed in building energy datasets has been proposed [

25,

26].

FL applies model aggregation to improve the global performance of all devices. Many traditional aggregation algorithms have been developed to tackle key challenges in federated learning, especially those concerning communication costs and data privacy. These algorithms often serve as fundamental building blocks within various federated learning frameworks. FedAvg [

27] is a foundational and widely used federated learning algorithm. It operates by randomly selecting a subset of clients for training in each round. The global model is then created by averaging the clients’ model parameters, weighted by the proportion of each client’s local dataset size. FedProx [

28] improves upon FedAvg by tackling the problem of local optima that can arise with stochastic gradient descent (SGD)-based training in federated settings. Unlike FedAvg, adaptive aggregation methods use alternative strategies for updating the global model. For example, the approach described in [

29] employs a temporally weighted aggregation technique that leverages previously trained local models to enhance the global model’s accuracy and convergence. An adaptive weighting technique called inverse distance aggregation (IDA) is presented in [

30]. Adaptive learning algorithms use adjustable parameters (e.g., learning rate) that automatically adapt to changes in data characteristics, available computing power, or other relevant environmental information. These adaptive approaches can lead to faster convergence and better accuracy. The standard stochastic gradient descent (SGD) used in FedAvg may not be ideal for situations where the stochastic gradient noise has a heavy-tailed distribution. To overcome this, adaptive optimization algorithms like Adagrad, Adam, and Yogi have been incorporated into federated learning to update the global model, as demonstrated in [

31].

In contrast to the aforementioned studies, this work employs a fuzzy-logic-based aggregation approach to forecast the electrical power generation from the PV unit problem to overcome the derivative operations in other adaptive structures such as stochastic gradient descent (SGD), eliminate the concepts of homogeneity, and mitigate issues such as drift problems.

The contributions of this paper are fourfold:

The primary contribution is the introduction of a novel, centralized FL framework integrated with a fuzzy-logic-driven aggregation mechanism that is specifically tailored for photovoltaic (PV) power generation forecasting. This paradigm is uniquely designed for independent and identically distributed (IID) data settings, enabling a single, optimally generalized global model architecture that maximizes prediction fidelity and scales efficiently across a large fleet of geographically distributed energy assets.

The research empirically demonstrates that our fuzzy-logic-enhanced aggregation strategy ensures superior parameter stability and significantly accelerated model convergence within the homogeneous FL environment. This methodological enhancement effectively mitigates training volatility induced by system noise and communication heterogeneity, thereby guaranteeing a highly robust and reliable global model that is truly representative of the universal power generation characteristics of the entire network.

The extensive experimental validation confirms that the proposed FL framework achieves significant outperformance in terms of predictive accuracy and training speed when benchmarked against purely local models and standard FedAvg algorithms. These compelling results establish a new state-of-the-art baseline for high-performance, large-scale PV forecasting under the prevalent conditions of data homogeneity.

Beyond the topics already covered, we discuss several other key aspects of implementing federated learning (FL) and fuzzy logic. We also showcase real-world applications where these techniques have proven to be effective and impactful. Finally, we identify and highlight open research questions, presenting exciting opportunities for future work in FL and fuzzy logic. Addressing these open challenges can drive innovation and lead to new directions and advancements in these fields.

The remainder of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 provides an overview of federated learning and its mathematical foundations.

Section 3 details the proposed fuzzy-logic-based aggregation method, FedFZY, within the federated learning (FL) framework. Subsequently,

Section 4 presents the application of FedFZY-enhanced FL for photovoltaic (PV) electrical power generation prediction.

Section 5 analyzes the experimental results obtained across diverse scenarios, evaluating the efficacy of the proposed FL model and presenting comparative analyses of different aggregation methods and variable perturbations. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the concluding remarks of this study.

3. Aggregation Models

To address the key challenges in federated learning, particularly those related to communication overhead and data privacy, a variety of traditional aggregation algorithms have been developed. These algorithms are often used as fundamental computing approaches within various federated learning frameworks.

3.1. FedAvg

FedAvg [

27] is a foundational and widely adopted federated learning algorithm. In each training round, a stochastic subset of clients is selected for participation. During the aggregation phase, the model parameters from each client are aggregated via a weighted average, where the weighting factor is proportional to the size of each client’s local dataset. It is important to note that FedAvg’s implementation can be extended to increase local computation by performing multiple iterations of local model updates before the averaging step. The update mechanism of FedAvg has been given in Equation (5).

3.2. FedProx

FedProx [

28] extends the FedAvg algorithm to address the issue of local objective divergence that is prevalent in stochastic gradient descent (SGD)-based federated learning. The core premise is that extensive local iterative updates within FedAvg can lead clients to prioritize local objective minimization, potentially deviating from the global model convergence objective. To counteract this, FedProx introduces a proximal regularization term into the local objective function. This term acts as a constraint, controlling the degree to which local models can deviate from the global model, thereby enforcing convergence guarantees and mitigating divergence. This term, defined as

, represents the

-norm distance between the local model and the global model. The parameter

µ, where

≥ 0, denotes the penalty constant associated with the proximal term. When

= 0, FedProx reduces to FedAvg. The proximal term’s constraint effectively regularizes the local model, pulling it towards the global model. Subsequent model aggregation and global model update procedures adhere to the standard FedAvg protocol.

3.3. TWA: Temporally Weighted Aggregation

In federated learning, standard aggregation strategies typically assign weights to local models, proportional to the respective client’s local dataset size. To enhance global model accuracy and convergence, a temporally weighted aggregation method, leveraging historical local model parameters, was proposed in [

29]. This method operates under the assumption that local models from earlier training rounds in the (t − i)th time slot, where i = 1, …, t − 1, carry less informational value than those from the most recent round in the tth time slot. This assumption is predicated on the dynamic nature of local training data, where more recent updates reflect the latest data distributions. Consequently, these recently updated local models are assigned higher importance during the global model aggregation. To incorporate this temporal freshness, the global model update is performed according to the following equation:

In this formulation, represents the base of the natural logarithm, employed to model the temporal decay effect. denotes the current global training round. signifies the training round in which the most recent update of the local model parameters, , was performed.

3.4. FedOpt

The standard stochastic gradient descent (SGD) algorithm employed in FedAvg can exhibit suboptimal performance in federated learning scenarios characterized by heavy-tailed distributions of stochastic gradient noise. To mitigate this limitation, adaptive optimization algorithms, including Adagrad, Adam, and Yogi, have been incorporated into the federated learning framework for global model updates, as documented in [

31]. The resulting global model update is performed according to the following equation:

In this context,

represents the set of exponential moving averages (EMAs) of the gradients, specifically

= {

}, corresponding to the FedAdagrad, FedAdam, and FedYogi optimization methods, respectively. The parameter

denotes the learning rate, while

controls the adaptivity level of the algorithm, with smaller

values indicating higher adaptivity. The EMA mechanism assigns greater weight to more recent data points. Details are presented in [

31], and the algorithm of each method can be found in this study.

The FedAdagrad, FedAdam, and FedYogi adaptive optimizers share a common computational flow, involving initialization, client subset sampling, and gradient estimation, and have demonstrated improved accuracy, relative to FedAvg. However, they differ in their operational characteristics. FedAdagrad is primarily optimized for sparse data structures, while FedAdam and FedYogi are applicable to both sparse and dense data distributions. FedAdam is characterized by a tendency towards rapid learning rate amplification, whereas FedYogi implements a controlled learning rate increment, with the formal proof of this behavior provided in [

33]. For the reasons mentioned above, the Fedyogi method has been chosen as a comparison tool in this study.

3.5. FedFZY: Fuzzy Aggregation

Both the aggregation methods described previously and the majority of those present in the literature determine a new update algorithm based on historical data. In contrast to these prior approaches, this work proposes an aggregation method that is analogous to a fuzzy-logic-based controller design.

A fuzzy-logic-based controller design offers a robust and adaptable approach to managing complex systems characterized by uncertainty and imprecision. Unlike traditional control systems that rely on crisp, binary logic, fuzzy logic controllers utilize linguistic variables and fuzzy sets to model human-like reasoning. This allows for the representation of vague or ambiguous information, making it particularly suitable for applications where precise mathematical models are difficult to obtain. A fuzzy logic controller typically consists of three main components: a fuzzification module, a rule-based inference engine, and a defuzzification module. The fuzzification module converts crisp input values into fuzzy sets, while the inference engine applies a set of fuzzy rules to determine the appropriate control actions. Finally, the defuzzification module transforms the fuzzy output back into a crisp value that can be used to control the system. This approach enables the design of controllers that are more resilient to noise, disturbances, and variations in operating conditions, leading to improved performance and stability.

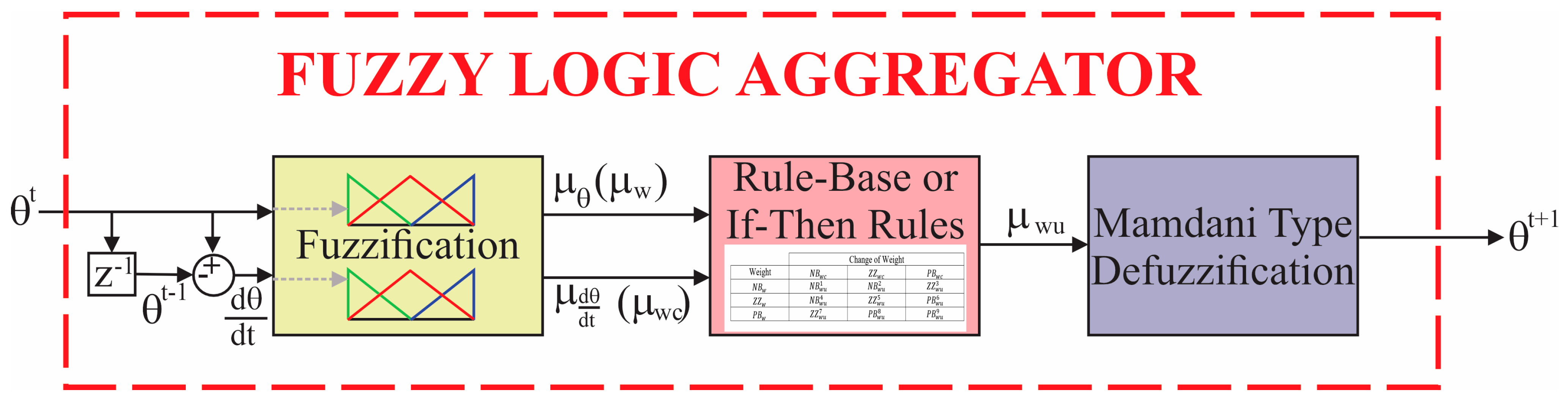

In this study, the new weight value received from each client and the difference between this weight value and the previous weight value have been provided as inputs for the fuzzy controller, and the final amount of weight update of each client has been determined at the output. The architecture for the proposed method has been illustrated, as given in

Figure 1.

In

Figure 1,

represents the zero-order hold or unit-time delay, while

demonstrates the weight value received from each client and

shows the difference between the received weight value and the previous weight value.

The universe of discourse (UoD) for the fuzzy logic controller operates on a [−1, 1] interval. This range allows the controller to either enhance (weight > 0) or partially invert/dampen (weight ≤ 0) client updates. Five (5) triangular membership functions (MFs) that are equally spaced across the UoD have been used, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the output domain.

The weight update value obtained from this process is determined individually for each client at the end of each epoch. The proposed method not only mitigates the client drifting problem but also provides a robust and reliable approach against noise and excessive variations. The proposed method aims to establish a more dynamic architecture by considering both the instantaneous and historical magnitudes of weight changes. Furthermore, this approach eliminates complex mathematical operations, such as derivatives, and designs a predictive aggregation methodology by incorporating the rate of weight change. Specifically, the two inputs, the magnitude of the current client update and its rate of change, allow for the fuzzy inference system to perform implicit regularization. It assigns a lower weight to the following: (1) updates with an unusually large magnitude, as these steps, even in IID settings, may result from high mini-batch noise or local optimization pathologies, potentially destabilizing the global model, and (2) updates that are highly unstable (large rate of change), indicating oscillatory or erratic local behavior.

By moderating these potentially divergent updates, the rule aims to create a smoother, more stable path toward the global minimum, thereby optimizing for faster, more reliable convergence.

The rule-based approaches implemented within this procedure have been tabulated in

Table 1 and

Table 2. The justification for the application of these rule sets is analogous to the conventional methodology utilized in the development of a standard fuzzy-logic-based controller. The rule set for the 9-rule configuration for three membership functions (MFs) has been detailed in

Table 1 and the rule set for the 25-rule configuration for five MFs has been defined in

Table 2. In these tables,

,

,

,

, and

represent negative big, negative small, closure to zero, positive small and positive big, respectively. Subscripts

,

, and

are demonstrating the new weight value received from each client, the change in the weight of it, and the final amount of weight update of each client calculated by fuzzy logic, respectively.

The examination of weight value changes originating from each client resembles a stochastic gradient descent (SGD)-like approach. However, conducting this analysis through membership functions (MFs) obviates the need for complex mathematical operations.

4. Case Studies

To assess the performance of our model in predicting PV-based 24 h electricity power generation for individual buildings, we employed a database collected from PV panels located in 14 buildings across seven districts within Erzurum province. A test case, encompassing all 14 buildings, has been conducted to specifically evaluate the efficacy of the fuzzy-logic-based federated learning (FedFZY) model. The experimental setup may be summarized by the following steps:

(1) Data description: The database collected from PV panels located in 14 buildings across seven districts within Erzurum province has been used for the case study. The dataset comprises energy consumption data from 1596 smart meters, deployed across 14 distinct building typologies within seven districts of Erzurum. Concurrently, it incorporates meteorological data, including module temperature, ambient temperature, wind speed, irradiation level, humidity, and precipitation, alongside electrical measurements from DC and AC ammeters, and active power meters, facilitating output power generation quantification. The dataset spans a three-year period, from 1 January 2022 to 31 December 2024, with a sampling frequency of 15 min. The last six months of the dataset are designated as the test set, while the remaining dataset has been divided into training and validation sets.

The sampling of electrical energy production from each building in this dataset has been conducted from the onset of solar irradiance on the PV panels, signifying the commencement of electrical energy generation until the cessation of energy production at sunset. Data points corresponding to periods without solar irradiance, and consequently no electrical energy generation, have been excluded from the dataset to prevent adverse effects on system training. This exclusion is necessitated by the fact that zero electrical energy production values under otherwise consistent environmental conditions would lead to erroneous training and parameter updates, particularly in artificial neural network-based models.

The input data has been normalized by dividing each feature value by the maximum observed irradiation value, specific to that feature’s range. This scales the inputs consistently between [0, 1].

(2) Evaluation metrics: Three established performance metrics, mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), are utilized to evaluate the predictive accuracy of individual building energy generation.

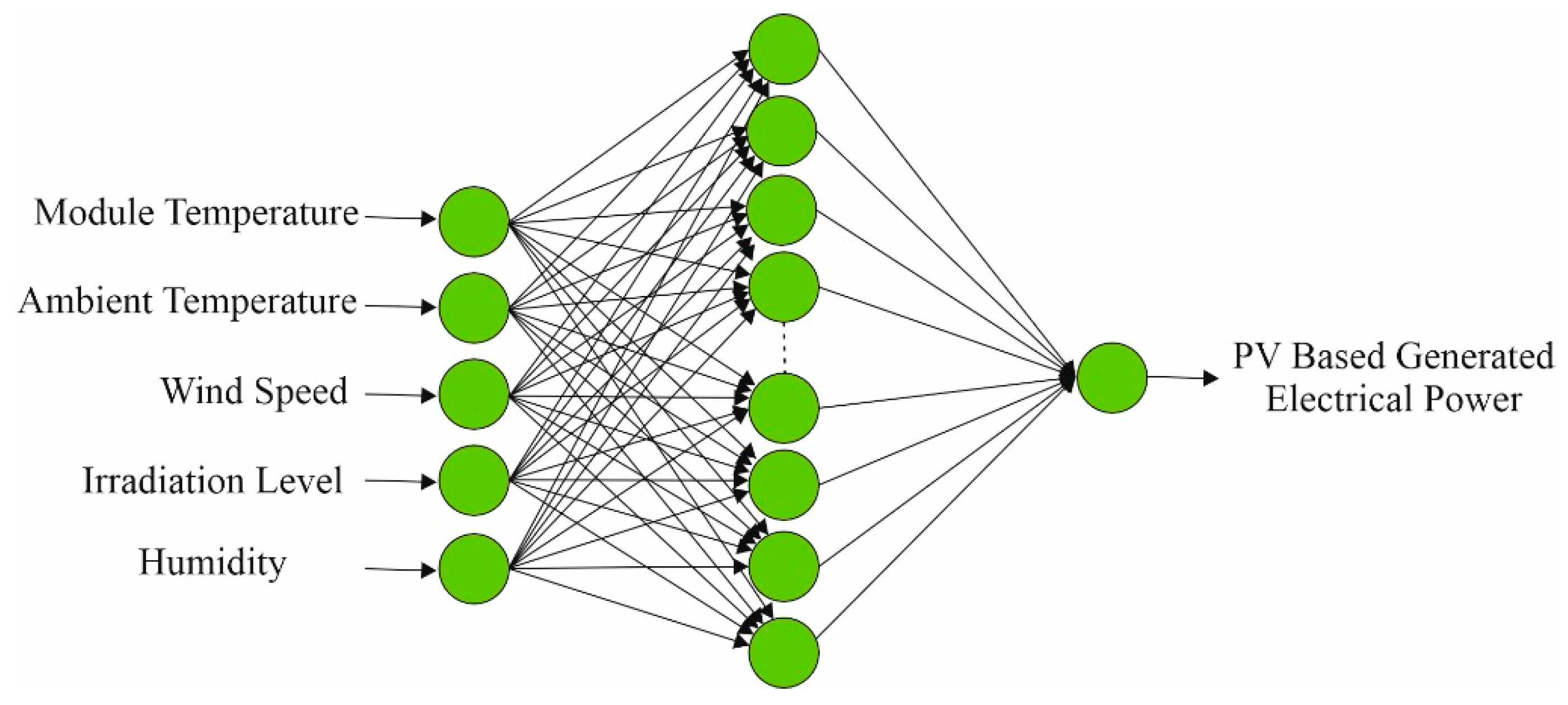

(3) Artificial neural network (ANN) architecture:

Figure 2 illustrates the architecture of the applied neural network, which consists of five input nodes, one hidden layer with 25 hidden neurons, and a single output node. Module temperature, ambient temperature, wind speed, irradiation level, and humidity have been designated as inputs of the selected ANN, while the generated electrical power has been selected as the output of the ANN. The training process utilized the classical back-propagation algorithm, and a logarithmic sigmoid activation function has been employed in the network. The learning rate for the selected ANN topology has been selected as 1 × 10

−6 and the epoch size for the training has been chosen as 100. The selected ANN architectures are the optimal solutions for modeling electrical energy generation, using a PV panel mounted on the roof of each building.

During the determination of the optimal solution for the selection of the ANN structure, coefficient of determination R2, reduced chi-square , and sum squared error, SSE, values have been calculated. Based on these values, an optimal ANN structure has been determined and the determined ANN architecture has been used in this study.

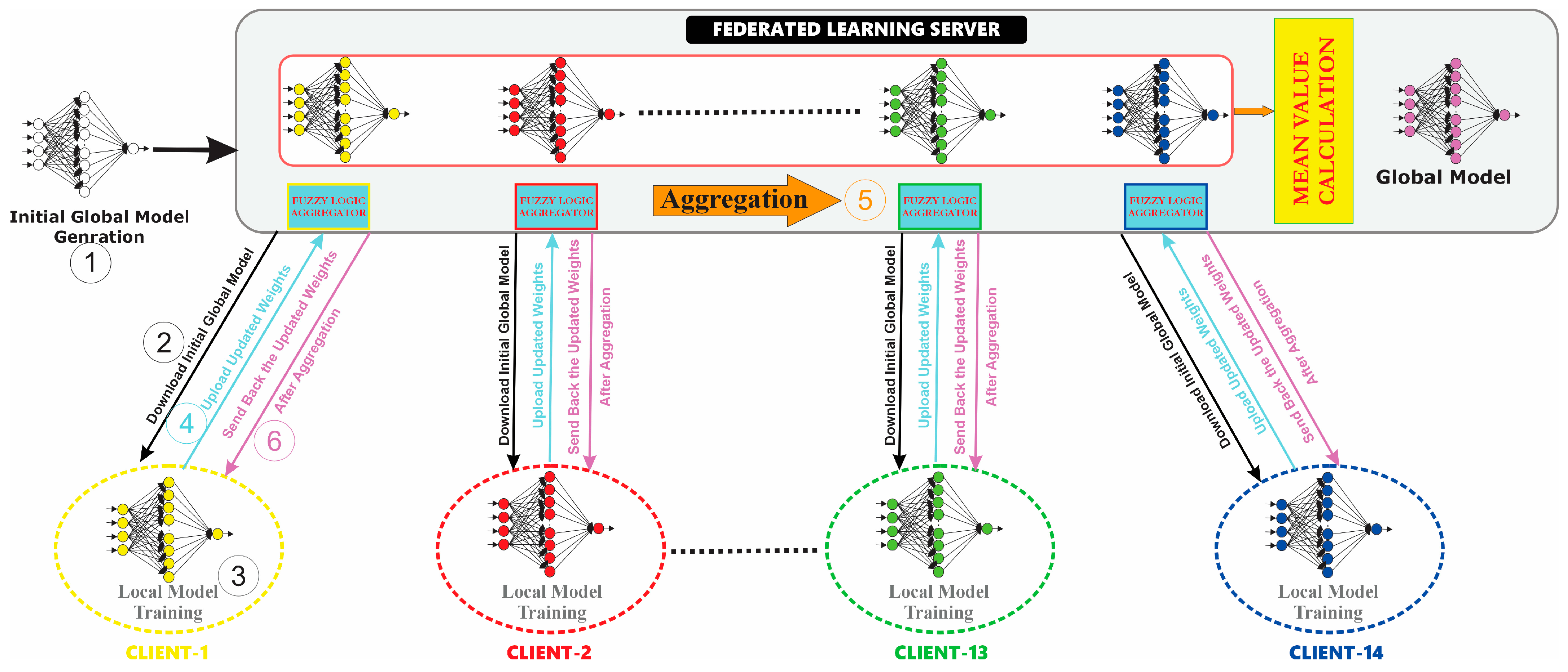

(4) Fuzzy-logic-based federated learning (FedFZY) architecture: In this study, a horizontal federated learning architecture has been used. Horizontal FL, also known as homogeneous FL, represents the scenarios in which the training data of participating clients share the same feature space but have different sample space. The number of clients, , has been selected as 14.

The total number of data coming from the 14 different buildings was 1,950,000, and 1,350,000 pieces of data have been used for the training process of FL. A total of 70% of the total data for each building has been used for training, while 15% of the data are for the test and 15% of the data are for validation. The weights of the network were initialized randomly on the server for each experiment and distributed to the clients with the same properties.

Following the generation of a generalized model within the federated learning construct, a set of 300,000 discrete data records has been utilized for quantitative performance evaluation. The architectural topology of the federated learning network has been depicted in

Figure 3.

(5) Mechanism of federated learning process: The mechanism of an FL process can be summarized as follows:

① Initialization and ② downloading initial model: A preliminary model is sent to each participating electrical energy generation forecasting system from the server. The weights of the artificial neural network have been initialized randomly on the server and distributed to the clients with the same properties.

③ Localized or distributed training: Each electrical energy generation forecasting system uses its local data to train and improves its model, rather than transferring large amounts of sensitive raw data. During local training, clients optimize model parameters using gradient descent algorithms. This iterative process involves adjusting the model parameters to minimize the chosen loss function, typically mean squared error (MSE) for regression tasks, and improve the model’s predictive performance on the local data.

④ Uploading trained model parameters to the server: After each client locally trains its model for the measured data, the trained model parameters are sent to the server for aggregation. Crucially, the upload process does not involve the transmission of raw data to the central server. Instead, only the model parameters, which encapsulate the knowledge learned from the local data, are shared. This approach ensures that the privacy and security of the underlying datasets are maintained while enabling collaborative model training.

⑤ Model aggregation and ⑥ return to each client: Following the compilation of locally trained models, the central server aggregates the models’ updates and synthesizes an improved global model. In this process, the new weight value received from each client and the difference between this received weight value and the previous weight value have been provided as inputs to the fuzzy controller, and the final amount of weight update of each client has been determined for the output.

Following model aggregation, the server distributes the updated global model back to each participating client. This enables each institution to leverage the collective intelligence and knowledge captured within the global model, thereby enhancing their local models and driving further refinement and improvement. This updated model, which incorporates insights from all participating users without requiring access to their raw data, is then distributed back to each user. In this context, the optimal global model,, is achieved by minimizing the aggregated loss function as given in Equation (2), , across all participating clients.

Model update at each client: Upon receiving the aggregated model from the server, each client updates its local model using the received parameters after the aggregation process. Refining and fine-tuning each client’s model will be available based on the insights gained from the collective knowledge of the network. Additionally, updating the process will provide the collaborative training of the models while preserving the privacy of the individual datasets of each client. This means that knowledge sharing and data protection allow for the development of accurate and comprehensive models in a secure and collaborative manner. The proposed FL-aggregator utilizes a non-linear, adaptive control mechanism to dynamically scale the influence of individual client updates. This system is designed with fuzzy rules that aggressively attenuate updates characterized by both large magnitudes and high divergence from the mean update vector. At this point, the update mechanism of the fuzzy-logic-based aggregation process is similar to FedAvg method, as given in Equation (5). The fuzzy-logic-based aggregation results received from each client are averaged, as given in Equation (5), and new updated weight values are obtained and sent back to each client.

Iteration: This cycle repeats until the model reaches an ideal or global state or the required number of iterations has been reached. The FL approach and its hierarchy have been demonstrated in

Figure 3.

A total of 15 computers—14 of them used as clients and 1 of them used as a server—have been used for the FL procedure with the following specifications: Intel Core i7 processor CPU @ 2.40 GHz, 8.00 GB RAM, 512 GB SSD, Windows 10 Pro operating system. All of the training and FL procedures have been executed in MATLAB 2022b environment. Upload and download processes have been performed through an ethernet protocol with a shared router.

5. Results

In order to make a comparison, FedAvg, FedProx, TWA, FedOpt, and the proposed FedFZY aggregation methods have been considered for all clients separately to forecast energy generation characteristics with the designed federated learning architecture. MAE, RMSE, and MAPE values have been calculated for 14 distinct buildings within seven districts of Erzurum. The minimum values of them have been tabulated in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5.

This study provides comparative evaluations of various aggregation methodologies within federated learning frameworks to assess the utility of federated learning for photovoltaic power prediction.

This study proposes a federated learning (FL) approach, designed to achieve a generalized model that is capable of accurate predictions across individual photovoltaic (PV) farms. FL offers enhanced generalizability compared to localized learning paradigms. In contrast to centralized learning, FL maintains data privacy by preventing the pooling of training data from individual PV farms. Instead, the training data remain localized at each client. Model generalizability is assessed through evaluation on unseen data. Specifically, a client holdout strategy is employed, where one client’s data are reserved for testing and the remaining clients’ data are utilized for training. Following training and validation, a separate holdout subset is used to provide a final performance estimate. This client holdout methodology facilitates the development of generalizable models that are applicable to future data acquisitions, beyond the training dataset.

During the experiments, the best MAE, RMSE, and MAPE values have been observed for FedFZY. The values closest to these results have been measured with the FedOpt aggregation method, and, as can be seen in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5, worse results have been obtained with the other aggregation methods examined.

The experiments show that the FedFZY model largely outperforms the other aggregation models by an average improvement of 2.77%, 1.71%, and 3.64% in MAE, RMSE, and MAPE, respectively.

6. Discussion

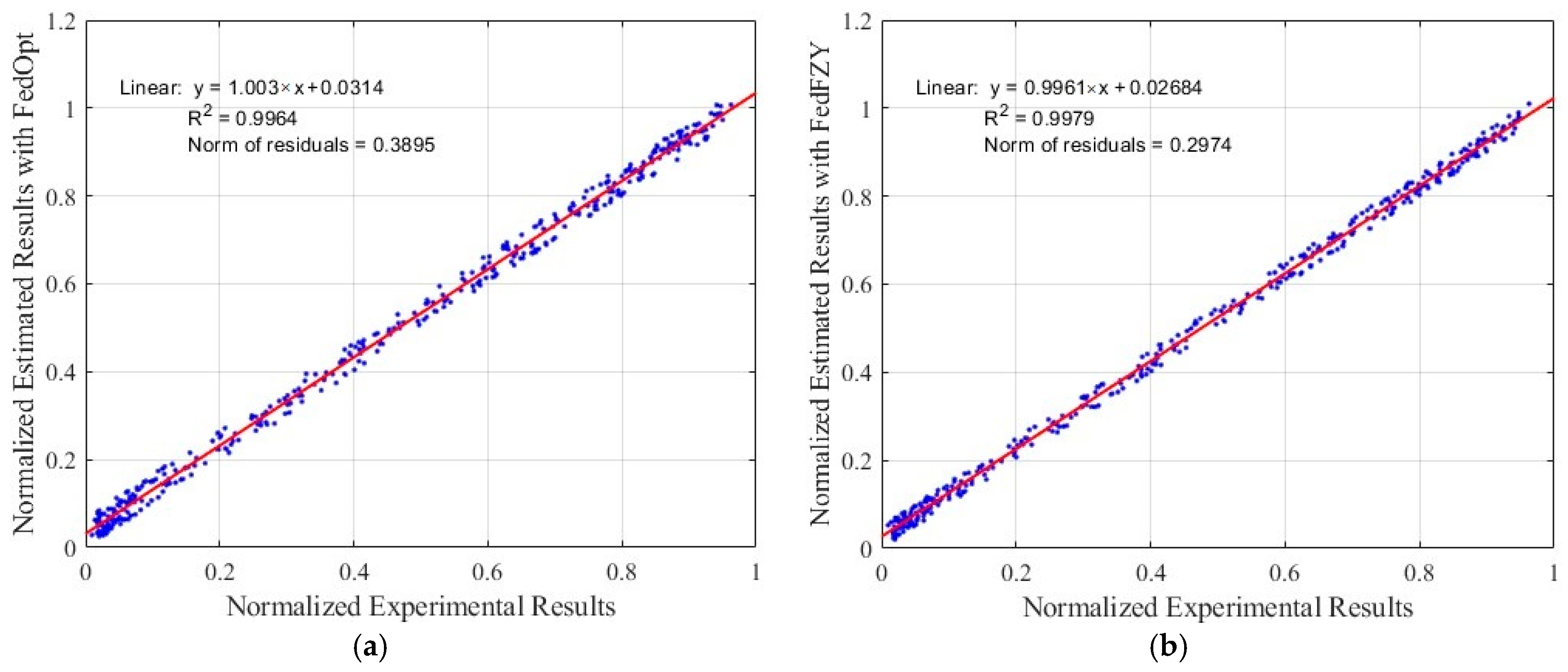

Estimated values with respect to experimental results have been represented in

Figure 4a,b. The difference between the coefficient of determination (R

2) values of FedOpt and FedFZY, which give the best results according to the estimation results, has been presented in

Figure 4. As depicted in

Figure 4b, the coefficient of determination (R

2), a statistical metric quantifying the correlation between predicted and observed outcomes, exhibits an elevated value for FedFZY, indicating an enhanced model fit. Furthermore, the coefficient of determination, R

2, for the convergence trajectory of FedFZY (0.9979) is notably higher than that of FedOpt (0.9964). This result empirically confirms the reduced oscillation and increased predictability imparted by the fuzzy controller’s dynamic, non-linear weighting mechanism, demonstrating superior algorithmic stability.

The primary purpose of running multiple seeds is to measure and control for high-variance/oscillatory behavior. However, the proposed internal analysis already confirms that the superior stability of FedFZY with the coefficient of determination for the FedFZY convergence curve was 0.9979, compared to 0.9964 for FedOpt. This exceptionally high R2 value serves as quantifiable empirical evidence that the fuzzy aggregator successfully dampens stochastic noise, resulting in a significantly more predictable and less volatile convergence trajectory. This demonstrates that the core mechanism of FedFZY inherently reduces the impact of seed-to-seed variance, making the observed performance difference highly robust and statistically significant, even if only a limited number of seeds were used in the reported figures and tables.

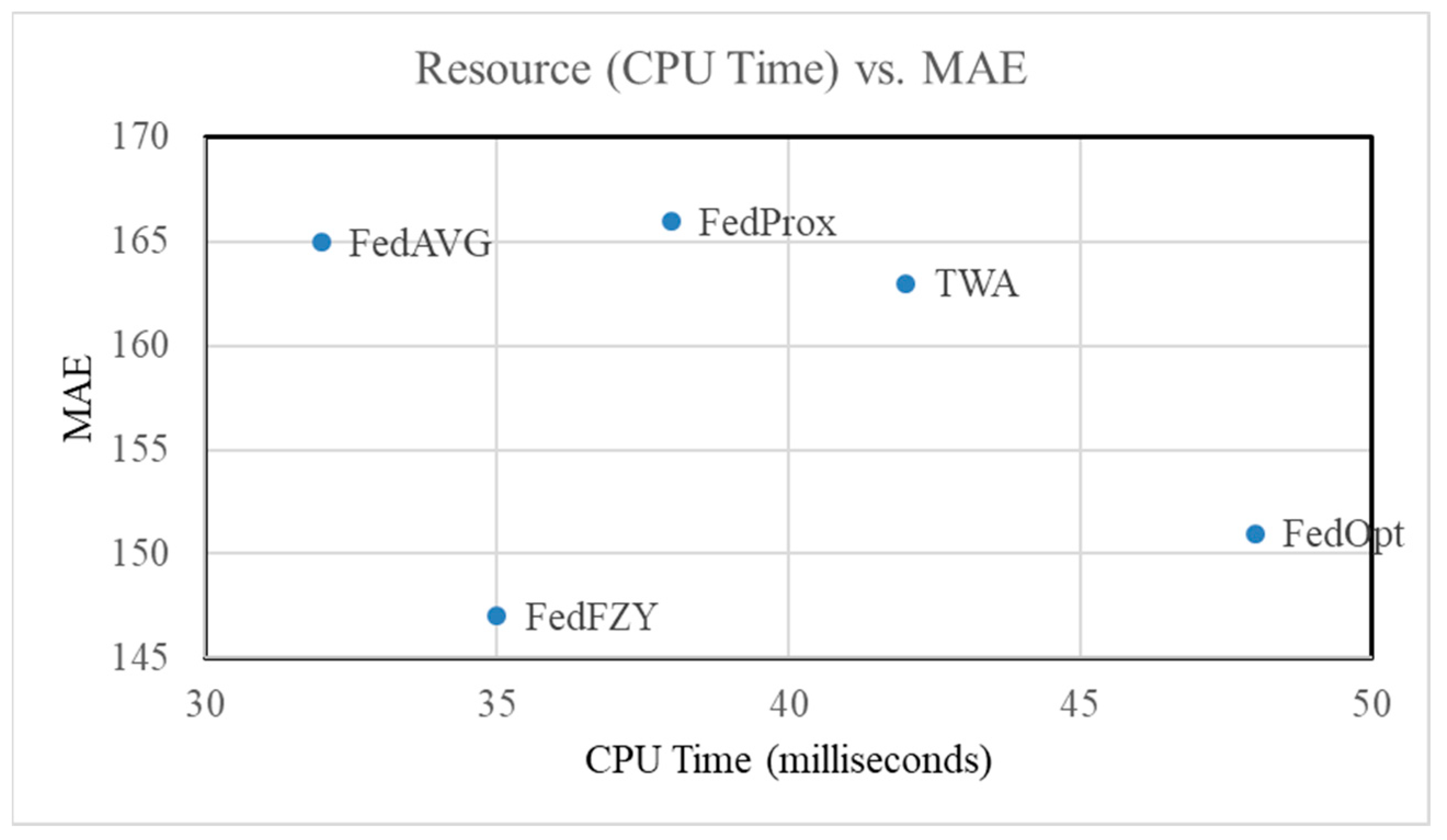

Considering the CPU time required for each aggregation step, the classical FedAvg method, which averages the weight values received from clients, exhibits the lowest CPU time of 32 milliseconds. This is followed by FedFZY at 35 milliseconds, FedProx at 38 milliseconds, TWA at 42 milliseconds, and FedOpt at 48 milliseconds. It is observed that there is no significant temporal disparity between FedFZY and FedAvg. The primary reason for FedFZY’s minimal CPU time requirement is attributed to the utilization of triangular membership functions, which are defined by simple linear relationships, obviating the need for complex mathematical operations.

Table 6 shows the comparisons of CPU time and memory consumption for each district.

Figure 5 shows the CPU time versus MAE. This illustrative figure depicts the expected relationship between the computational resources consumed by the aggregation method (represented by relative aggregation CPU time for each method on the

x-axis) and the resulting model error (MAE on the

y-axis).

Based on the above analysis, given in

Figure 5, the proposed method unequivocally demonstrates that the computational complexity of the fuzzy inference system (FIS) is remarkably low, leading to a highly favorable position on the resource–error curve. This analysis will clearly illustrate that the modest performance improvements (reduction in MAE/RMSE) achieved by the FL-aggregator are realized at a

negligible computational compromise. The concrete data and accompanying figure will visually confirm that the FL-aggregator operates in a highly desirable region of the resource–error curve, where superior accuracy is achieved without demanding significant additional computational resources that would hinder its practical deployment.

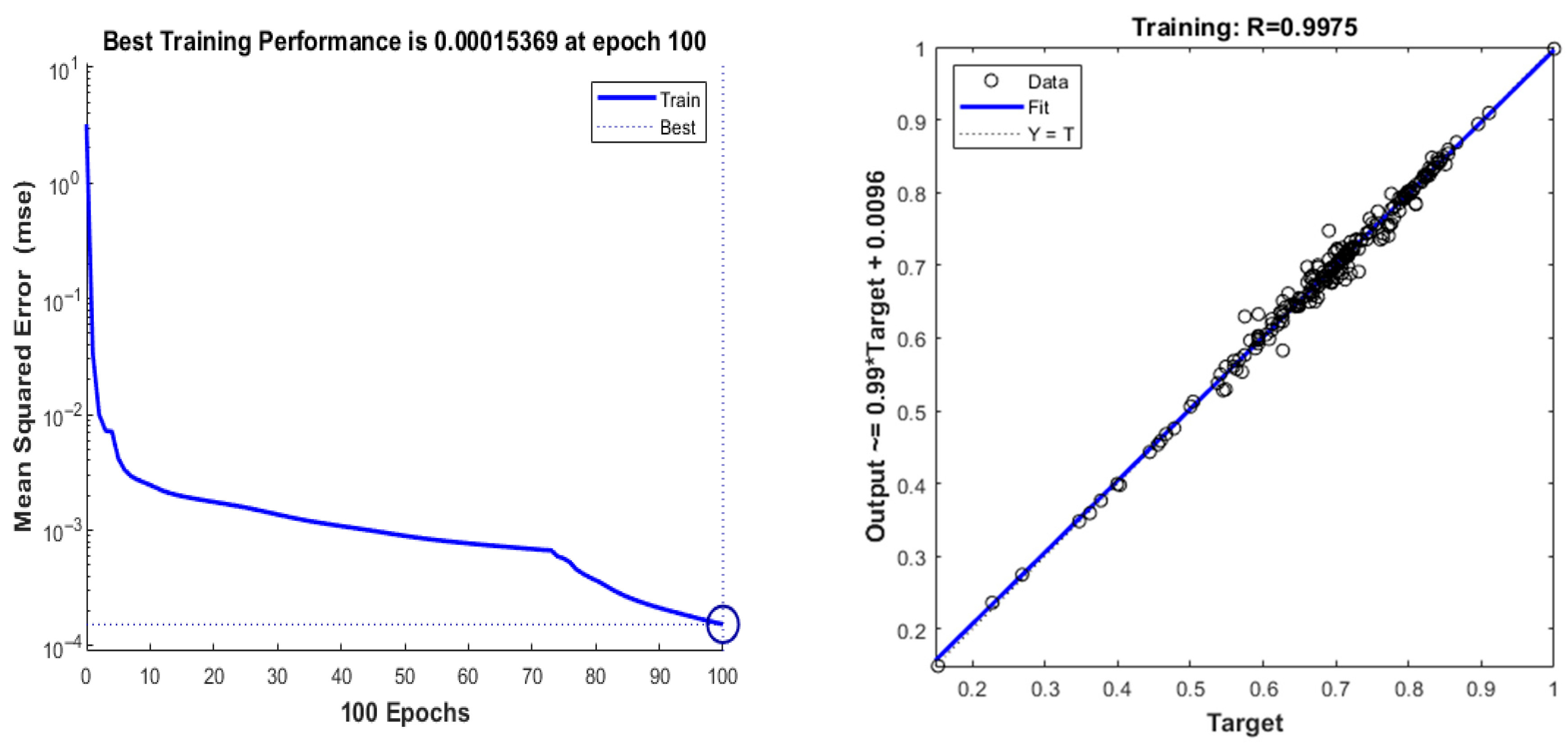

Performance graphs of the training, test, and validation phases of the optimal ANN architecture are given in

Figure 6. According to this curve, the results obtained after 100 epochs, using the classical back-propagation algorithm and the logarithmic sigmoid activation function, have proven to be quite accurate. The circle at the bottom of the graph represents the final value reached as a result of the epochs.

Upon evaluation of the prediction performance concerning the 9-rule-based structure presented in

Table 1 and the 25-rule-based structure presented in

Table 2, it has been observed that the coefficient of determination (R

2) value obtained from the prediction results was 0.9979 for the 9-rule configuration and 0.9980 for the 25-rule configuration. Due to the statistically negligible performance discrepancy, the adoption of the 9-rule formalism instead of the 25-rule or more approach is recommended for achieving augmented computational processing.

The proposed FL-aggregator is designed to optimize maximizing the robustness of the global model update with respect to multicriteria client uncertainty (heterogeneity, noise, and staleness) by implementing a non-linear, interpretable, and continuous soft-thresholding filter. The proposed FL-aggregator method uses a non-linear, adaptive mechanism to regulate the influence of individual client updates on the global model, and utilizes non-linear fuzzy rules to aggressively down-weight updates that are far from the consensus and have large magnitudes.