1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) manufacturing technology, these batteries have become the dominant power source for a wide range of applications, including smartphones, portable electronics, electric vehicles (EVs), and energy storage systems (ESSs) [

1]. Owing to their high energy density, long cyclability, and excellent power capability, LIBs outperform most other secondary batteries and have thus become central to modern energy infrastructure [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

However, the chemical reactivity and flammable electrolyte composition of LIBs pose significant safety concerns. Once a thermal runaway (TR) is triggered, the stored energy is released in a chain reaction involving rapid temperature rise, ignition, explosion, and fire propagation, leading to severe property damage and safety hazards [

8,

9,

10]. Given the accelerating deployment of large-scale battery installations, ensuring the fire safety of LIBs has become one of the most urgent technical challenges in the field of energy storage. Recent studies have focused on understanding the ignition conditions and fire-propagation characteristics of LIBs with different battery types and materials. Existing diagnostic methods can be broadly divided into destructive (ex situ) and non-destructive (in situ) techniques [

11,

12]. Ex situ approaches, such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [

13], transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [

14], and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) [

15], analyze electrode and electrolyte degradation through material characterization but require disassembly of the battery. In contrast, in situ approaches monitor the battery’s electrochemical condition externally using methods such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) [

16], differential voltage analysis (DVA) [

17], and incremental capacity analysis (ICA) [

18]. Although these methods are effective in tracking electrochemical degradation, they are insufficient for detecting early electrical precursors that could indicate internal short circuits or insulation failure.

To address this limitation, this study introduces a time-resolved partial discharge (TRPD)-based diagnostic method that interprets a lithium-ion battery as an electrical insulation system, where the separator acts as the main dielectric medium. This perspective allows the detection of localized discharges caused by defects such as lithium dendrite growth, metallic particle contamination, or separator aging before catastrophic failure occurs. By capturing transient discharge signals and analyzing their temporal and spectral characteristics, the proposed approach enables early identification of micro internal short circuits (MISC)—one of the key initiators of TR in LIBs [

19].

This paper thus contributes a novel cross-domain methodology that bridges conventional insulation diagnostics with battery safety monitoring. Through combined TRPD and fast fourier transform (FFT) analysis, both ex situ and in situ experiments were performed to extract frequency-domain features related to defect events. The findings are expected to support the development of real-time early warning systems for EV and ESS applications, thereby advancing fire prevention strategies for next-generation battery technologies.

2. Methodology

2.1. Time-Resolved Partial Discharge

TRPD analysis is a diagnostic technique used to characterize transient discharge phenomena within electrical insulation systems over time. Originally developed for high-voltage equipment such as transformers and cables, TRPD enables the early detection of microscopic insulation degradation by resolving discharge events in the time domain with high temporal precision [

20,

21,

22].

In this paper, the TRPD concept is extended to LIBs, which can be regarded as complex electrical insulation systems in which the separator acts as the primary dielectric layer between electrodes. Defects such as lithium dendrite formation, metallic particle contamination, and separator aging may initiate localized discharge events that occur before complete insulation breakdown. These discharges appear as high-frequency transient pulses whose amplitude, repetition rate, and waveform shape reflect the characteristics of the internal defect mechanism.

Unlike conventional partial discharge (PD) monitoring, which merely detects the occurrence of discharges, TRPD provides time-resolved quantitative parameters, such as pulse magnitude, phase distribution, occurrence frequency, and energy. By analyzing these parameters, insulation degradation can be identified and localized before catastrophic short-circuit events occur. Therefore, TRPD offers a high-resolution and non-invasive diagnostic framework suitable for early-stage fault detection in LIBs [

23,

24,

25].

Figure 1 illustrates a representative TRPD waveform in the time domain, showing a sharp transient pulse corresponding to the localized discharge event. As shown in

Figure 1, the discharge pulse exhibits a rapid rise and decay with a distinct high-frequency component, indicating the instantaneous release of localized charge within the insulation layer [

26].

2.2. Fast Fourier Transform

The FFT algorithm serves as the core analytical tool for the frequency-domain interpretation of TRPD signals. By transforming discharge waveforms from the time domain to the frequency domain, FFT analysis reveals the dominant frequency components and energy distribution patterns associated with defect electrical activity. The discrete fourier transform (DFT) of an N-sample signal

x(

n) is defined as:

where, x(n) represents the input signal in the time domain, X(k) represents the output components in the frequency domain, and

denotes the complex exponential function components.

Therefore, the FFT is an algorithm that significantly increases computational speed by reducing redundant operations in DFT calculations. When a signal is sampled at uniform time intervals and the sampled time-domain data are transformed into the frequency domain using the FFT algorithm, the frequency components of the signal can be identified. Moreover, FFT serves as a key tool in TRPD analysis. When combined with the TRPD algorithm, it enables frequency spectrum analysis of PD signals; calculation of discharge pulse repetition rate, amplitude, and energy distribution; and noise filtering and feature extraction of the signals. By comparing spectral responses across different sensors—namely the high-frequency current transformer (HFCT) and electromagnetic antennas—distinct high-energy peaks are observed near 3.9 MHz, 11.9 MHz, and 19 MHz, which are characteristic of MISC events [

27,

28].

2.3. Micro Internal Short Circuit (MISC) Phenomenon

A MISC refers to a localized, high-resistance electrical pathway that unintentionally forms between the positive and negative electrodes of a lithium-ion battery [

29]. Unlike a full internal short circuit (ISC), a MISC allows only a minute current to flow—typically in the microampere to milliampere range—making it extremely difficult to detect through conventional voltage or current measurements.

MISCs are induced by structural, mechanical, or electrochemical irregularities, including separator puncture, metallic particle intrusion, lithium plating, or localized overpotential during rapid charging [

30,

31,

32]. Mechanical deformation, vibration, or thermal aging can further deteriorate the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer and reduce insulation resistance, generating leakage currents that may evolve into thermal events.

The progression mechanism of a MISC can be summarized as follows:

Initial defect formation: localized damage to the separator or lithium dendrite growth.

Formation of micro-conductive paths: small leakage current (–) begins to flow.

Localized heating and SEI degradation: micro-temperature rise and interfacial breakdown.

Electrolyte decomposition and gas generation: accelerated degradation and swelling.

Expansion into a full short circuit and TR: rapid temperature escalation and fire risk.

Because these processes evolve gradually, external electrical measurements alone are insufficient for early detection. Therefore, integrating TRPD-based transient signal detection with FFT-based spectral analysis provides a highly sensitive approach for recognizing early MISC-related anomalies. The hybrid diagnostic framework proposed in this paper has the potential for real-time fault monitoring and the implementation of preventive control algorithms within battery management systems (BMSs), significantly enhancing the safety and reliability of LIBs [

33].

3. Experimental

In this paper, both in situ and ex situ experiments were performed to diagnose and prevent fire hazards in LIBs. The experimental configuration was designed to ensure repeatability, accuracy, and safety while measuring transient discharge signals under controlled charge–discharge and mechanical deformation conditions.

3.1. In Situ Experiment

The in situ experiment was conducted to analyze degradation-induced defect signals generated during battery charge–discharge cycling. Cylindrical LIBs were subjected to accelerated degradation tests under two temperature conditions: room temperature (25 °C) and high temperature (60 °C). Charge–discharge cycling was carried out at a 1 C-rate and 2 C-rate using a constant current–constant voltage (CCCV) charging mode (up to 4.2 V) and a constant current (CC) discharging mode (down to 2.5 V). All experiments were conducted using a NEWARE CT-4008 (NEWARE; Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China) charge–discharge tester for precise control of current and voltage.

Table 1 shows the specifications of the cylindrical lithium-ion battery used in this paper. As shown in

Table 1, the test battery was a Samsung INR18650-30Q model (Samsung SDI; Yongin-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea), which provides a nominal voltage of 3.6 V and a nominal capacity of 3000 mAh.

During each degradation test, frequency-domain measurements were acquired using a PicoScope 3000 (Pico Technology; Cambridgeshire, UK) series oscilloscope with a time base of 200 ms/div and a sampling rate of 80 MS/s. The common-mode voltage (CMV) trigger thresholds were set to 250 mV for the HFCT (1–500 MHz) and 2 V for the electromagnetic antennas (0.5–30 MHz and 30–300 MHz). The CMV noise and defect discharge signals obtained during cycling were then compared with those derived from the destructive test conditions.

3.2. Ex Situ Experiment

The ex situ experiment aimed to replicate mechanically induced MISC conditions by applying controlled deformation forces to the exterior of cylindrical batteries. Different test probes—sharp needle, semi-elliptical, and spherical shapes—were used to induce physical defects in a systematic manner. The deformation was applied in 1 mm incremental steps, and at each step, the resulting high-frequency response was recorded using multiple sensors, including wideband electromagnetic wave (EMW) antennas (300–2000 MHz), transient earth voltage (TEV) sensors (0.5–20 MHz), and HFCT sensors (1–500 MHz).

Figure 2 shows the various probe geometries used to apply physical stress during the ex situ test. As shown in

Figure 2, the probes were designed to reproduce different contact areas and stress concentrations, enabling a comparison of frequency-domain responses for distinct deformation types.

Figure 3 illustrates the complete experimental setup for frequency measurement. As shown in

Figure 3a, the test apparatus includes the deformation unit, battery holder, sensors, and safety enclosure.

Figure 3b presents the dedicated lithium-ion battery fire extinguisher system integrated to ensure safety during destructive testing.

Table 2 lists the key test equipment used in this paper, while

Table 3 summarizes the sensors and their operating frequency ranges. These configurations were kept identical to those of the in situ tests to ensure comparability of results.

Figure 4 shows the detailed configuration of the sensors labeled as “No. 6” in

Figure 3. As shown in

Figure 4, each sensor type was mounted in proximity to the battery surface to maximize sensitivity to transient electromagnetic emissions generated during PD and mechanical deformation events.

3.3. Experimental Procedure and Data Validation

To ensure measurement reliability, all tests were repeated three times per condition, and the obtained signals were averaged to eliminate random noise. Environmental factors such as temperature and humidity were carefully controlled. Defect signals were identified when their amplitudes exceeded predefined thresholds (250 mV for the HFCT and 2 V for the electromagnetic antennas), based on the CMV baseline values recorded during steady-state operation.

Both in situ and ex situ datasets were analyzed using the identical FFT and TRPD post-processing procedures described in

Section 2. This consistency enabled direct comparison between the degradation-induced and mechanically induced signal patterns. The resulting spectral data formed the basis for the correlation analysis discussed in

Section 4.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. In Situ Results

In this paper, the degradation behavior of lithium-ion batteries was analyzed under both room-temperature (25 °C) and high-temperature (60 °C) conditions. The battery capacity decreased progressively with cycling, with a more rapid decline under high-temperature and 2C-rate conditions due to accelerated side reactions and SEI decomposition.

Figure 5 shows the capacity variation of the lithium-ion battery during the degradation tests. As shown in

Figure 5, the capacity reduction rate was most pronounced in the high-temperature 2C-rate test, confirming that thermal stress and high current density significantly accelerate battery degradation.

The corresponding defect signal data and CMV noise collected during degradation were analyzed using HFCT or electromagnetic antenna sensors.

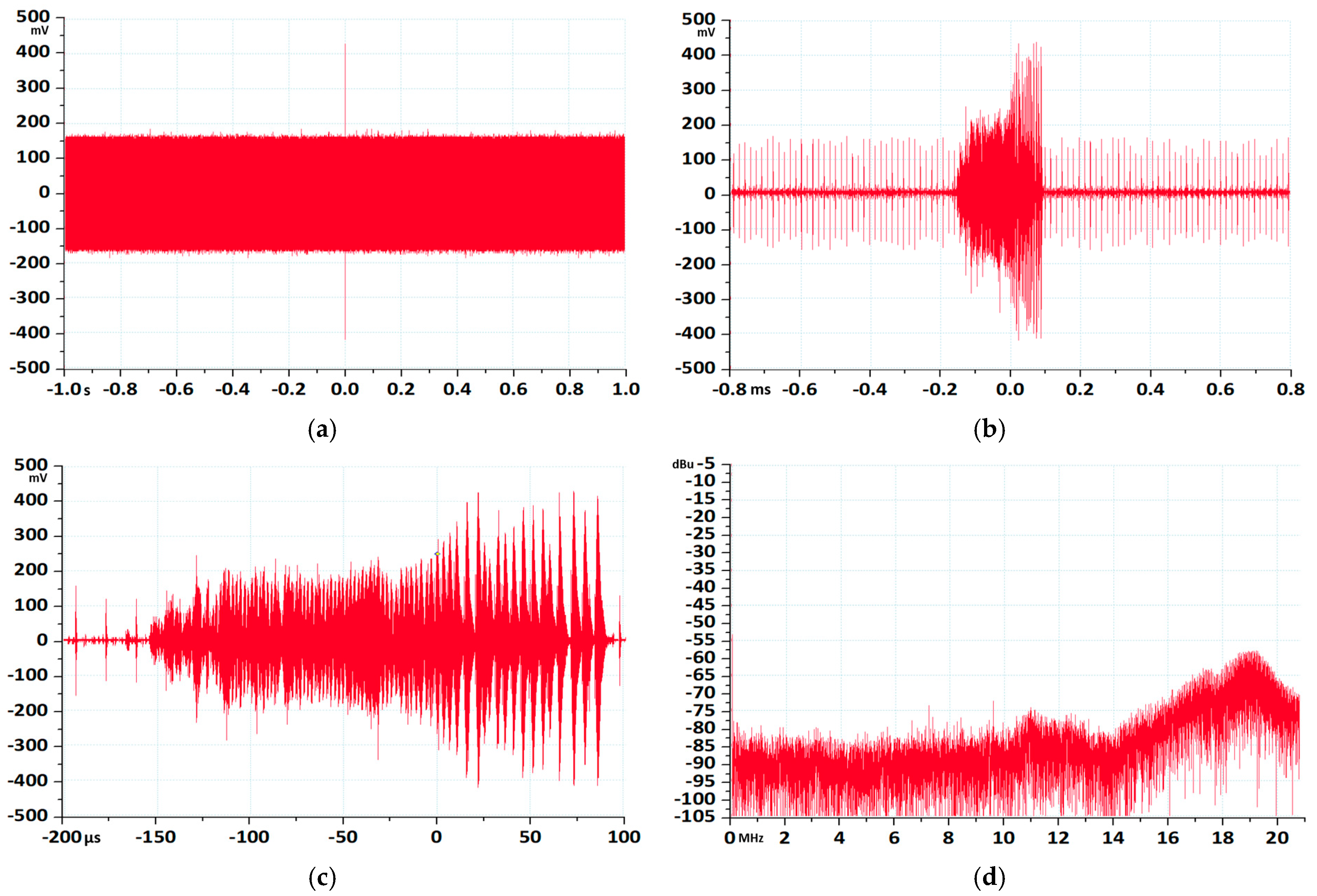

Figure 6 shows the test results under 2C-rate and 60 °C conditions, as well as the defect signal and CMV noise waveforms obtained from the HFCT sensor. As shown in

Figure 6a, the HFCT-detected signals exhibited amplitudes exceeding 250 mV, clearly distinguishable from the CMV noise levels below 200 mV.

Figure 6b,c present magnified views of the transient discharge pulses, while

Figure 6d displays their FFT spectra, revealing a dominant frequency component near 19 MHz.

Similarly,

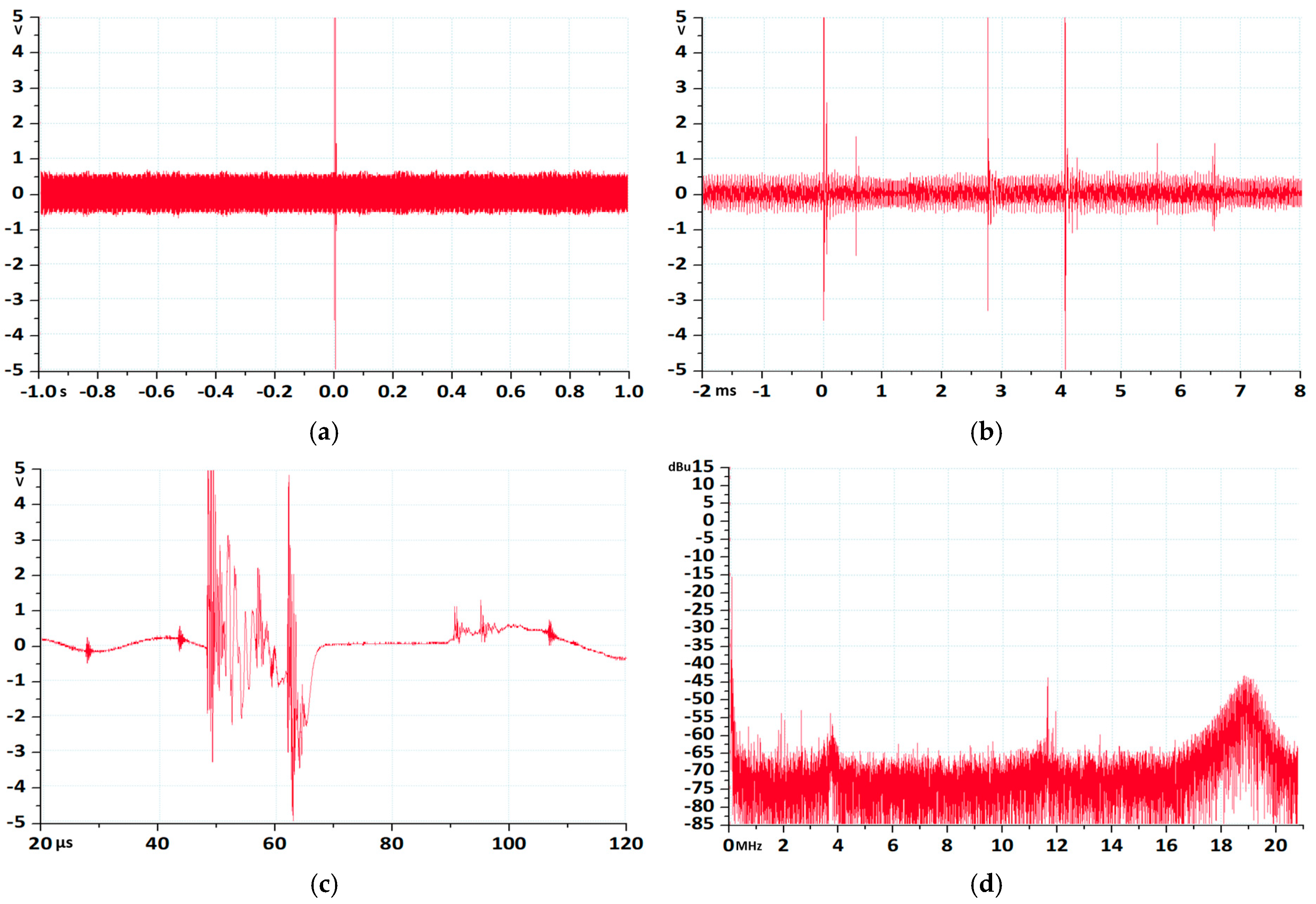

Figure 7 illustrates the results obtained under 2C-rate and 60 °C conditions, using the electromagnetic antenna sensor. As shown in

Figure 7a–c, defect discharge events appear as sharp transients with amplitudes greater than 2 V, well above the CMV noise level of 1 V.

Figure 7d shows the corresponding FFT results, where distinct peaks are observed at 3.9 MHz, 11.9 MHz, and 19 MHz. These frequencies correspond to characteristic MISC-related emissions detected in the high-frequency domain. The consistent occurrence of high-energy peaks across multiple frequency bands confirms that TRPD–FFT-based analysis can effectively isolate early-stage defect discharge phenomena from background electrical noise. The amplitude–frequency relationships suggest that the severity of battery degradation is correlated with increased discharge pulse intensity and spectral density. When using two types of sensors, we confirmed that the frequency of defect signal occurrences was higher under more severe environmental conditions.

4.2. Ex Situ Results

The ex situ experiment aimed to reproduce internal short-circuit phenomena through controlled mechanical deformation of the battery surface. During the test, physical force was incrementally applied to the battery casing using the probes shown in

Figure 2, and the resulting discharge signals were recorded under identical measurement conditions to the in situ setup.

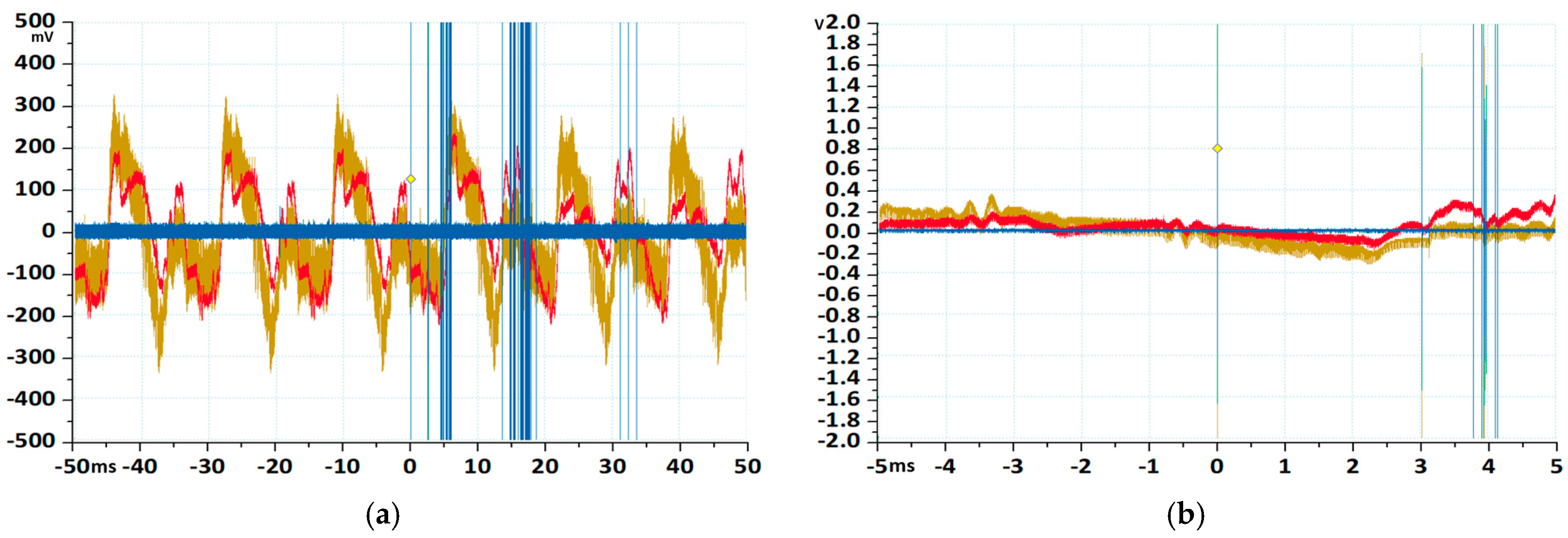

Figure 8 shows the MISC-related defect signals obtained from the HFCT and electromagnetic antenna sensors during the ex situ experiment. As shown in

Figure 8a, the HFCT sensor detected transient pulses with amplitudes exceeding 250 mV, consistent with those observed during degradation-induced MISCs.

Figure 8b indicates that the electromagnetic antenna captured similar defect transients above 2 V, validating that mechanical damage produces spectral patterns analogous to electrochemical degradation. The observed similarity between the ex situ and in situ results demonstrates the reproducibility of TRPD-based detection. In both cases, distinct spectral peaks were found around 3.9 MHz, 11.9 MHz, and 19 MHz, supporting the hypothesis that MISC events generate characteristic discharge frequencies regardless of their origin (mechanical or chemical).

4.3. Comparative Analysis and Discussion

By comparing in situ and ex situ results, it was confirmed that both methods yield similar signal amplitude ranges and frequency-domain characteristics. This indicates that the TRPD–FFT framework can reliably identify internal degradation phenomena even when the external symptoms are minimal.

The following key findings were derived:

Amplitude distinction: Defect discharge signals consistently exceeded the CMV noise threshold (200 mV for HFCT, 1 V for antenna), allowing for clear event detection.

Frequency correlation: Dominant peaks at 3.9 MHz, 11.9 MHz, and 19 MHz appeared repeatedly across both experimental setups, indicating consistent spectral fingerprints of MISC events.

Sensor complementarity: The HFCT sensor showed superior sensitivity to localized current transients, while the electromagnetic antenna was more effective for broader electromagnetic field emissions.

Diagnostic reliability: The correlation between signal intensity and degradation severity suggests that the TRPD–FFT technique can serve as a quantitative diagnostic metric for assessing battery health.

The results confirm that the proposed TRPD–FFT diagnostic method effectively differentiates defect electrical activity caused by MISC from ordinary CMV noise. This capability enables early warning of internal insulation degradation before the onset of TR, providing a foundation for real-time BMS integration in EVs and ESS applications.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a TRPD–based diagnostic approach was proposed to identify early electrical precursors of fire hazards in LIBs. Both in situ and ex situ experiments were conducted to investigate defect discharge signals under electrochemical degradation and mechanical deformation conditions. By integrating FFT analysis with TRPD signal acquisition, the study successfully extracted characteristic frequency-domain features associated with MISC phenomena.

The experimental results demonstrated that defect discharge signals could be clearly distinguished from CMV noise based on amplitude thresholds—250 mV for HFCT and 2 V for electromagnetic antenna sensors. Distinct frequency peaks consistently appeared at 3.9 MHz, 11.9 MHz, and 19 MHz, which correspond to the dominant spectral signatures of MISC events. Furthermore, the similarity between the in situ and ex situ results confirms the reproducibility and reliability of the proposed diagnostic framework.

This paper thus establishes a novel cross-disciplinary connection between electrical insulation diagnostics and battery safety monitoring. The proposed TRPD–FFT method enables early identification of latent insulation degradation before the onset of TR, offering a high-precision and non-invasive diagnostic tool suitable for real-time BMSs in EVs and ESS applications. The method also provides a new foundation for developing predictive maintenance algorithms and safety-oriented monitoring architectures in large-scale battery systems.

Future work should include extended degradation experiments using various battery chemistries and formats (pouch, prismatic, and solid-state batteries) and testing at low-temperature environments (<0 °C) to verify the universality of the observed frequency-domain indicators. Additionally, the incorporation of AI-based classification and pattern-recognition techniques to automate the detection of MISC events and further enhance diagnostic accuracy should be explored.

Author Contributions

Methodology, C.-W.K.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-C.J.; resources, S.-H.L.; formal analysis, K.-M.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.-S.C.; Validation, S.-H.L.; Supervision, K.-M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Jeollanamdo RISE center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Jeollanamdo, Republic of Korea. (2025-RISE-14-004).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who provided valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Chang-Won Kang was employed by the Department of Research Engineering PSD Technologies Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| LIBs | Lithium-ion batteries |

| EVs | Electric vehicles |

| ESSs | Energy storage systems |

| TR | Thermal runaway |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| EIS | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| DVA | Differential voltage analysis |

| ICA | Incremental capacity analysis |

| TRPD | Time-resolved partial discharge |

| MISC | Micro internal short circuit |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transform |

| PD | Partial discharge |

| DFT | Discrete Fourier transform |

| HFCT | High-frequency current transformer |

| ISC | Internal short circuit |

| SEI | Solid electrolyte interphase |

| BMS | Battery management system |

| CCCV | Constant current–constant voltage |

| CC | Constant current |

| CMV | Common mode voltage |

| EMW | Electromagnetic wave |

| TEV | Transient earth voltage |

References

- Karden, E.; Ploumen, S.; Fricke, B.; Miller, T.; Snyder, K. Energy Storage Devices for Future Hybrid Electric Vehicles. J. Power Sources 2007, 168, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y. Lithium Ion Secondary Batteries; Past 10 Years and the Future. J. Power Sources 2001, 100, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issues and Challenges Facing Rechargeable Lithium Batteries—Nature. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/35104644 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Park, G.-T.; Park, N.-Y.; Ryu, J.-H.; Sohn, S.-J.; Yu, T.-Y.; Kim, M.-C.; Baiju, S.; Kaghazchi, P.; Yoon, C.S.; Sun, Y.-K. Zero-Strain Mn-Rich Layered Cathode for Sustainable and High-Energy Next-Generation Batteries. Nat. Energy 2025, 10, 1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lushington, A.; Gao, J.; Li, Q.; Zuo, P.; Wang, B.; Gao, Y.; Ma, Y.; et al. Superior Performance of Ordered Macroporous TiNb2O7 Anodes for Lithium Ion Batteries: Understanding from the Structural and Pseudocapacitive Insights on Achieving High Rate Capability. Nano Energy 2017, 34, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-H.; Shih, J.-Y.; Li, Y.-J.J.; Tsai, Y.-D.; Hung, T.-F.; Karuppiah, C.; Jose, R.; Yang, C.-C. MoO3 Nanoparticle Coatings on High-Voltage 5 V LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 Cathode Materials for Improving Lithium-Ion Battery Performance. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Gao, M.; Pan, H.; Liu, Y.; Yan, M. Lithium Alloys and Metal Oxides as High-Capacity Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 575, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöberl, J.; Ank, M.; Schreiber, M.; Wassiliadis, N.; Lienkamp, M. Thermal Runaway Propagation in Automotive Lithium-Ion Batteries with NMC-811 and LFP Cathodes: Safety Requirements and Impact on System Integration. eTransportation 2024, 19, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Duan, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Q. Experimental Investigation on Thermal Runaway Propagation of Large Format Lithium Ion Battery Modules with Two Cathodes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 172, 121077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yuan, J.; Zhu, X.; Wang, H.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S. Overcharge-to-Thermal-Runaway Behavior and Safety Assessment of Commercial Lithium-Ion Cells with Different Cathode Materials: A Comparison Study. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 55, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.Z.; Jaegers, N.R.; Hu, M.Y.; Mueller, K.T. In Situ and Ex Situ NMR for Battery Research. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2018, 30, 463001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, I.; Morey, J.; Ledeuil, J.B.; Madec, L.; Martinez, H. A Critical Discussion on the Analysis of Buried Interfaces in Li Solid-State Batteries. Ex Situ and in Situ/Operando Studies. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 25341–25368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Kowada, H.; Deguchi, M.; Hotehama, C.; Hayashi, A.; Tatsumisago, M. XPS and SEM Analysis between Li/Li3PS4 Interface with Au Thin Film for All-Solid-State Lithium Batteries. Solid State Ion. 2018, 322, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.M.; Xu, W.; Liu, J.; Choi, D.W.; Arey, B.; Saraf, L.V.; Zhang, J.G.; Yang, Z.G.; Thevuthasan, S.; Baer, D.R.; et al. In Situ Transmission Electron Microscopy and Spectroscopy Studies of Interfaces in Li Ion Batteries: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Mater. Res. 2010, 25, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutthanandan, V.; Nandasiri, M.; Zheng, J.; Engelhard, M.H.; Xu, W.; Thevuthasan, S.; Murugesan, V. Applications of XPS in the Characterization of Battery Materials. J. Electron. Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2019, 231, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Shin, H.-C.; Kim, J.M.; Choi, J.-Y.; Yoon, W.-S. Modeling and Applications of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhu, J.; Lu, D.D.-C.; Wang, G.; He, T. Incremental Capacity Analysis and Differential Voltage Analysis Based State of Charge and Capacity Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy 2018, 150, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anseán, D.; García, V.M.; González, M.; Blanco-Viejo, C.; Viera, J.C.; Pulido, Y.F.; Sánchez, L. Lithium-Ion Battery Degradation Indicators Via Incremental Capacity Analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 2992–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Ouyang, M.; Liu, X.; Lu, L.; Xia, Y.; He, X. Thermal Runaway Mechanism of Lithium Ion Battery for Electric Vehicles: A Review. Energy Storage Mater. 2018, 10, 246–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Madhar, S.; Mráz, P.; Rodrigo Mor, A.; Ross, R. Study of Corona Configurations under DC Conditions and Recommendations for an Identification Test Plan. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 118, 105820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuc, V.C.; Lee, H.S. Partial Discharge (PD) Signal Detection and Isolation on High Voltage Equipment Using Improved Complete EEMD Method. Energies 2022, 15, 5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florkowski, M.; Kuniewski, M.; Zydroń, P. Measurements and Analysis of Partial Discharges at HVDC Voltage with AC Components. Energies 2022, 15, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, L.; Kasper, M.; Kahn, M.; Gramse, G.; Ventura Silva, G.; Herrmann, C.; Kurrat, M.; Kienberger, F. High-Potential Test for Quality Control of Separator Defects in Battery Cell Production. Batteries 2021, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imburgia, A.; Rizzo, G.; Romano, P.; Ala, G.; Candela, R. Time Evolution of Partial Discharges in a Dielectric Subjected to the DC Periodic Voltage. Energies 2022, 15, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florkowski, M. Influence of Insulating Material Properties on Partial Discharges at DC Voltage. Energies 2020, 13, 4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarian Niasar, M. Partial Discharge Signatures of Defects in Insulation Systems Consisting of Oil and Oil-Impregnated Paper; KTH Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, J.W.; Lewis, P.A.W.; Welch, P.D. The Fast Fourier Transform and Its Applications. IEEE Trans. Educ. 1969, 12, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, B.; Bhattacharjee, P.K. Comparison of Discrete Fourier Transform and Fast Fourier Transform with Reduced Number of Multiplication and Addition Operations. Int. J. Appl. Math. Inform. 2020, 14, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, L.; Lu, L.; Feng, X.; Han, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, D.; Liu, X.; Sauer, D.U.; et al. A Review of the Internal Short Circuit Mechanism in Lithium-Ion Batteries: Inducement, Detection and Prevention. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 15797–15831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanagopalan, S.; Ramadass, P.; Zhang, J.Z. Analysis of Internal Short-Circuit in a Lithium Ion Cell. J. Power Sources 2009, 194, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Gao, W.; Han, X.; Feng, X.; Ouyang, M. Micro-Short-Circuit Cell Fault Identification Method for Lithium-Ion Battery Packs Based on Mutual Information. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 4373–4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Kong, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, L.; Lai, X. Real-Time Diagnosis of Micro-Short Circuit for Li-Ion Batteries Utilizing Low-Pass Filters. Energy 2019, 166, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Dominic, J.; Chen, B.; Lai, J.-S. A High-Efficiency Single-Phase Bidirectional AC-DC Converter with Miniminized Common Mode Voltages for Battery Energy Storage Systems. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition, Denver, CO, USA, 15–19 September 2013; pp. 5145–5149. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).