1. Introduction

The environmental advantages of renewable energy sources (RESs) and their potential to displace fossil fuels have garnered considerable attention in recent years. Experts predict that they will play a key role in ensuring that everyone in the globe has access to modern, clean energy [

1]. The global energy sector is undergoing a significant transformation, with renewable energy sources emerging as a crucial solution to mitigate climate change, reduce dependence on fossil fuels, and ensure sustainable energy access. Solar PV is projected to become the largest renewable energy source by 2029 [

2]. The solar panel market is expected to grow at an average yearly growth rate of 11.8% through 2030 due to reduced costs [

3]. Among various renewable technologies, solar photovoltaic (PV) systems have demonstrated remarkable potential due to their scalability, reliability, and rapidly declining costs, making them one of the most promising technologies for urban power generation [

4]. PV systems, wind, and small hydropower are the most efficient renewable energy sources for providing electricity to both on- and off-grid areas. Especially in high-density cities like Dhaka, using rooftops is very environmentally friendly. In

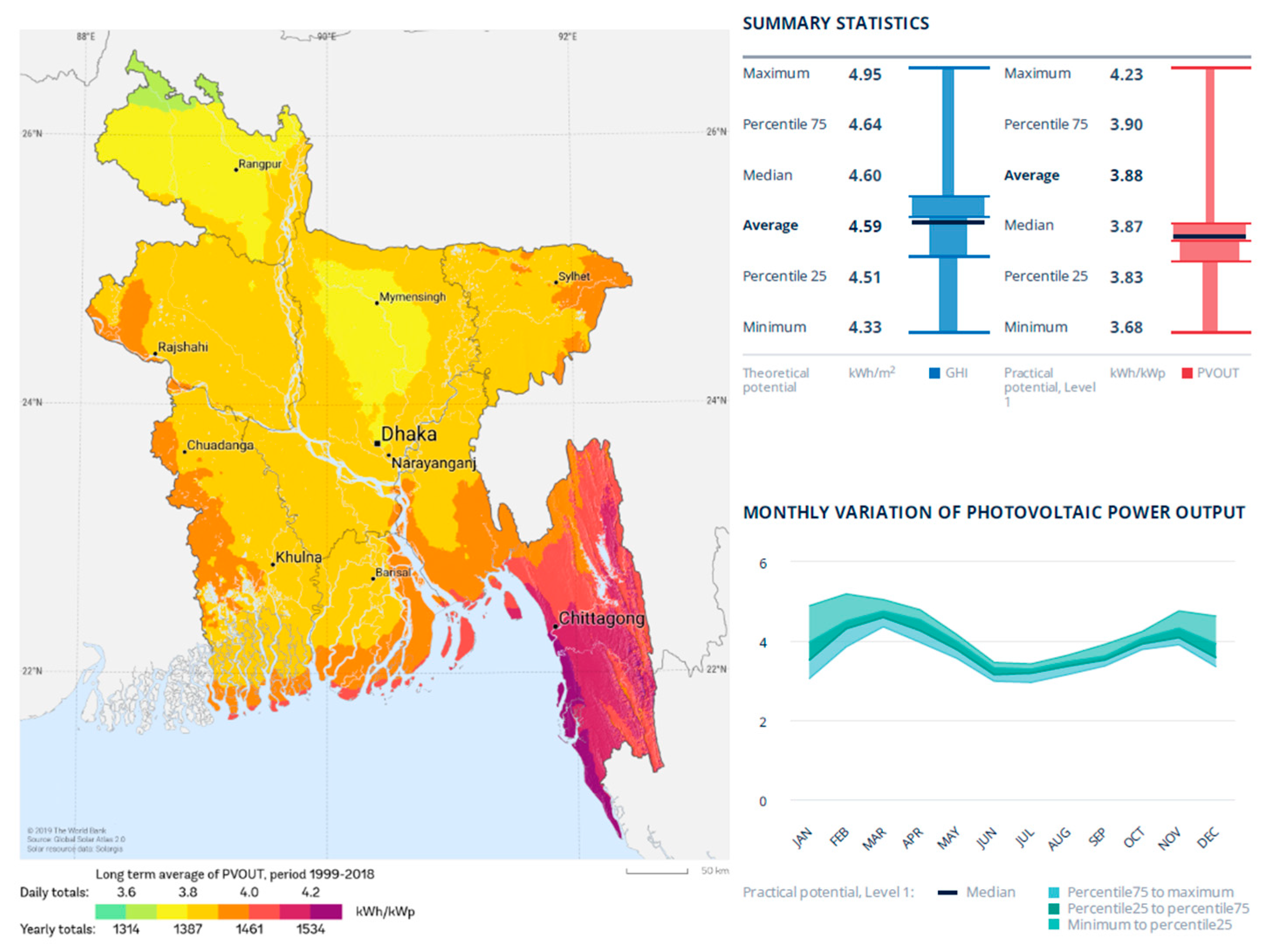

Figure 1, solar PV potential power is shown from a top-down view of Bangladesh. The figure also shows the variation in PV power with respect to the month of the year [

5,

6].

In densely populated regions such as Dhaka, Bangladesh, the adoption of grid-connected PV systems offers a viable pathway to address rising electricity demand while simultaneously lowering carbon emissions. The Government of Bangladesh has already emphasized renewable integration into the national grid, with solar PV positioned as a key contributor to Sustainable Development Goals [

8]. Dhaka, a rapidly growing megacity, faces rising challenges with electricity demand, urban pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions. Rapid urbanization and industrialization require innovative solutions to balance energy security with environmental sustainability. Grid-connected PV systems have gained attention due to their ability to generate clean electricity within limited spaces, including rooftops, building-integrated facilities, and ground-mounted systems [

9]. Such systems also provide economic benefits, reducing grid stress during peak demand periods while ensuring long-term operational savings for consumers [

10].

Furthermore, several studies have been conducted to establish key performance and financial metrics, underscoring the continued importance of assessing the techno-economic viability of PV systems. For example, research has successfully shown that large-scale solar farms in areas with high radiation levels are economically feasible [

11], whereas others have used this approach for BIPV (building-integrated photovoltaics) in urban settings [

12]. Similarly, when evaluating the potential of grid-tied rooftop systems for the residential and commercial sectors, techno-economic analyses have been essential in confirming their financial viability under advantageous policy frameworks [

13,

14]. This body of work consistently highlights the sensitivity of project economics to variables such as initial capital expenditure, solar resource availability, and government-led incentives.

Techno-economic analysis is essential for solar PV, wind, and battery systems since it provides the most suitable, reliable, and cost-effective configurations [

15]. For distribution networks, Reference [

16] conducts a techno-economic analysis of a grid-connected solar PV system with electric vehicles (EVs) and battery energy storage systems (BESSs) using [

17] four optimization algorithms. However, integrating BESS, EVs, and PV systems requires complex coordination and entails an initial capital outlay, which may limit adoption in emerging distribution networks. Reference [

18] proposes photovoltaic (PV) microgrids to address energy constraints in Bangladesh, particularly in Char Jazira, Lalpur, Natore, and Rajshahi. However, for grid-connected solar PV systems in Bangladesh, future work should focus on developing higher-efficiency solar technologies and more affordable, large-capacity energy storage systems to ensure a stable generation supply. Reference [

19] addresses the significant issue of frequent power outages in Bangladesh’s educational institutions by proposing a renewable energy-based microgrid solution for a remote primary school. The system comprises PV, wind turbines (WTs), BESS, and conventional grid integration, analyzed through simulations on HOMER Pro 3.14.2 software. In [

20], a HOMER Pro-optimized technique is used to create a grid-connected solar PV–biogas microgrid for a five-story Rajshahi residential building in Bangladesh. In [

21], four models—PV, biogas, wind, and hydrogen—within a net-metering scheme are analyzed for green transportation in Bangladesh, focusing on their techno-economic viability. Reference [

16] assesses floating solar photovoltaics (FSPVs) in Bangladesh through an integrated techno-economic and multi-criteria decision-making framework, determining that Bergobindopur Lake is the optimal location, offering the highest energy yield at the lowest cost. The findings indicate that FSPVs surpass land-based PV systems across diverse economic scenarios, demonstrating significant profitability, particularly when supported by advantageous tariff structures.

The above discussion indicates that various techno-economic analyses have been proposed to support renewable energy integration in Bangladesh. However, there is still a noticeable lack of thorough techno-economic modeling of PV systems under intricate real-world constraints and integrated with emerging technologies. Real-world constraints include diverse weather changes, sudden blackouts, black-start capability, sudden damage to the panel, and the effect of sudden hail on the panel. In particular, comprehensive techno-economic assessments of PV systems tailored to urban university campuses in densely populated areas of Dhaka are still largely unexplored. BESS is a system that stores excess energy in a battery and provides it when required. A lot of current analyses tend to concentrate on conventional, grid-connected systems without adequately taking into account the integration of battery energy storage systems (BESS), which is becoming more and more important for reliability and energy shifting [

17,

22].

FPV refers to the installation of solar PV panels on floating structures placed on water bodies such as lakes or ponds. Although FPV offers benefits such as land savings and evaporation reduction, there are relatively few comprehensive studies that evaluate its techno-economic trade-offs, including maintenance requirements, installation complexity, and associated costs [

23,

24]. Similarly, BESS technologies present several limitations, including high initial investment, limited lifespan, thermal management challenges, and potential environmental concerns [

25]. FPV systems also face constraints such as complex installation procedures, higher maintenance demands, and risks related to water corrosion [

24]. However, our study focuses specifically on direct roof-to-grid PV integration; therefore, neither battery energy management systems (BESSs) nor floating photovoltaic (FPV) systems are within the scope of our design. Furthermore, many models oversimplify the economic impact of performance loss and degradation rates over a project’s lifetime, which could result in overly optimistic financial returns [

26]. To close these gaps and provide a more reliable and accurate financial prognosis for next-generation PV projects, more complex simulations that fully utilize tools such as PVsyst are needed. These simulations must integrate site-specific externalities, storage cycling losses, and detailed degradation profiles [

22].

Considering these issues at hand, this study evaluates the feasibility of a 27 kWp grid-connected solar PV system designed for a university campus in Green Road, Dhaka, using the PVsyst 7.4 simulation software. A Sunways STT-30KTL (Ningbo, China) inverter and 80 SunPower SPR-MAX2-340 modules (San Jose, CA, USA) are used in the system, which is oriented with a 24° tilt towards the south. Simulation results show an annual energy yield of approximately 36,483 kWh, with a specific production of 1341 kWh/kWp/year and a performance ratio of 82.58%. These findings align with earlier studies highlighting the efficiency of photovoltaic systems under tropical and subtropical climatic situations [

27]. Furthermore, the system is expected to offset around 504 tCO

2 over its lifetime, thereby significantly contributing to climate mitigation efforts. With the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) of 0.06 USD/kWh and a payback period of under five years, the proposed system demonstrates both environmental and economic viability. Our findings offer a framework for comparable situations in high-density areas like Dhaka and elsewhere in Bangladesh, as well as novel insights into the technical, financial, and environmental feasibility of PV for growing communities.

The novelty and academic contribution of this research are summarized below.

Real-world technical and economic modeling of grid-connected PV systems considering shading, losses, degradation, financial uncertainty, and so on.

Optimization of tilt angle considering dense roof architecture applicable for South Asian universities.

Full lifecycle-based CO2 LCA method.

Comprehensive P50-P90 Analysis.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 summarizes the use of rooftop solar PV in higher education institutions. Materials and methods are outlined in

Section 3.

Section 4 provides results and discussion. Future recommendations are listed in

Section 5. Finally, this work is summarized in

Section 6.

2. Rooftop Solar PV in Higher Education Institutions

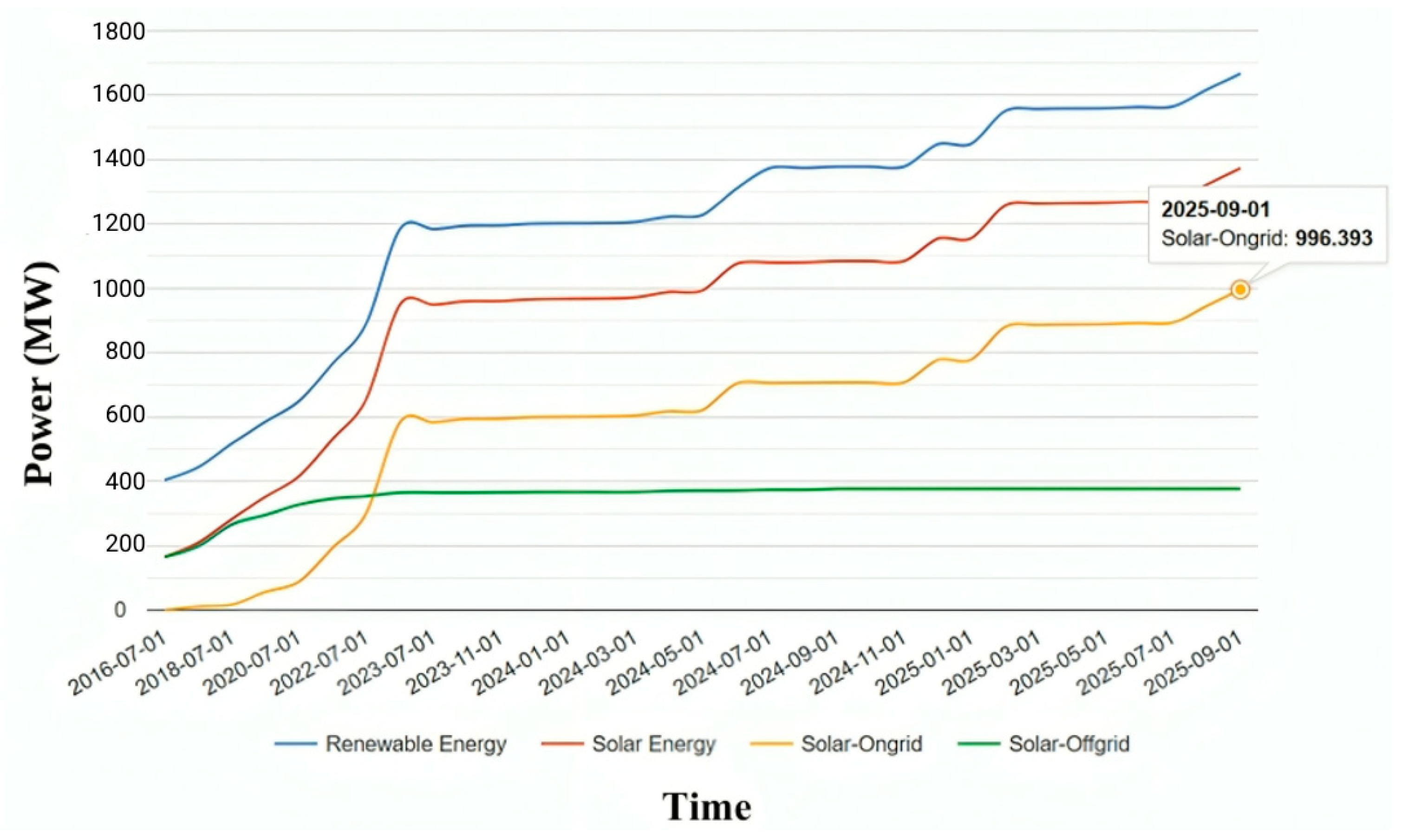

Bangladesh has observed high-level renewable energy integration in recent years, as shown in

Figure 2. To advance the national goal of sustainable energy systems, rooftop solar PV systems are increasingly adopted by higher education institutions. The deployment is aided by universities’ large rooftop areas and commitment to sustainability, allowing real-time power generation and reducing distribution losses. Integrating advanced monitoring systems enables data-driven energy management strategies, while grid-connected inverters that comply with national standards facilitate energy export and optimize electricity billing. Additionally, universities are exploring hybrid configurations with battery energy storage systems to enhance microgrid operation, enabling peak shaving and backup power.

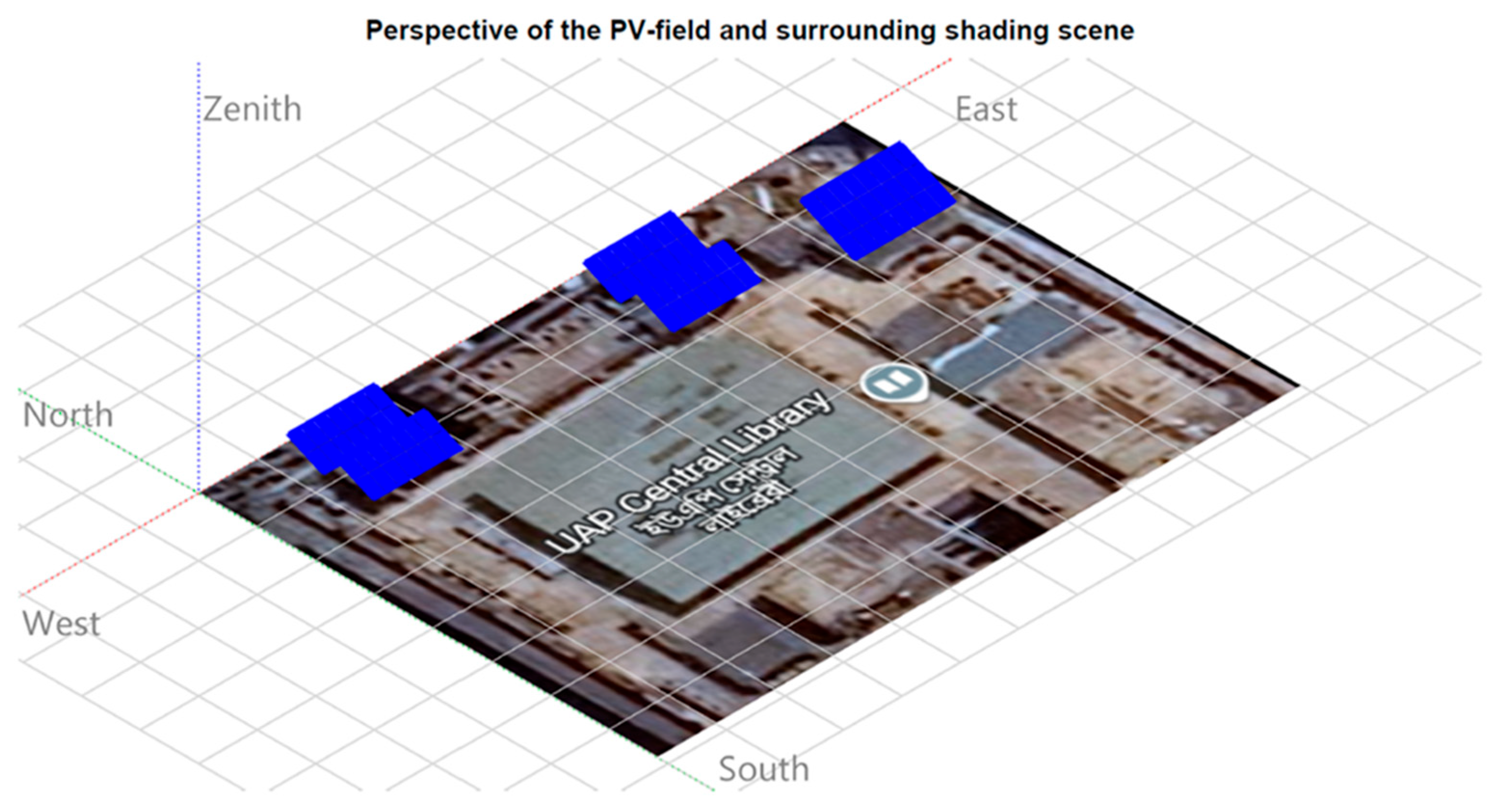

Figure 3 shows the 3D layout of the rooftop PV field at the University of Asia Pacific (UAP) library building. It shows where the panels are placed and how they are shaded. The blue rectangles show the solar PV arrays that are on the roof. The axes show the cardinal directions (north, south, east, and west) and the zenith angle, which makes it easier to understand how to orient the PV panels and how shading might affect them.

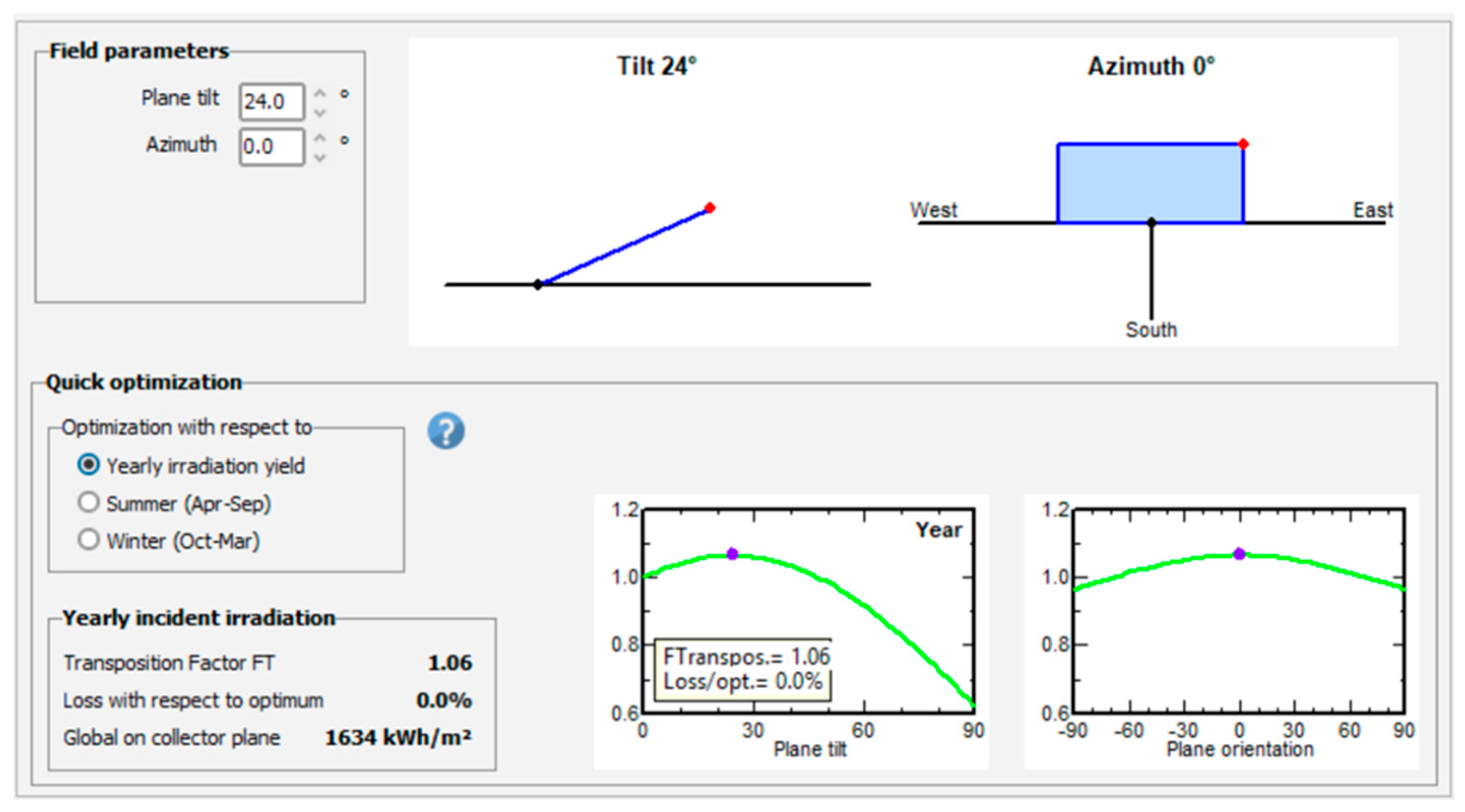

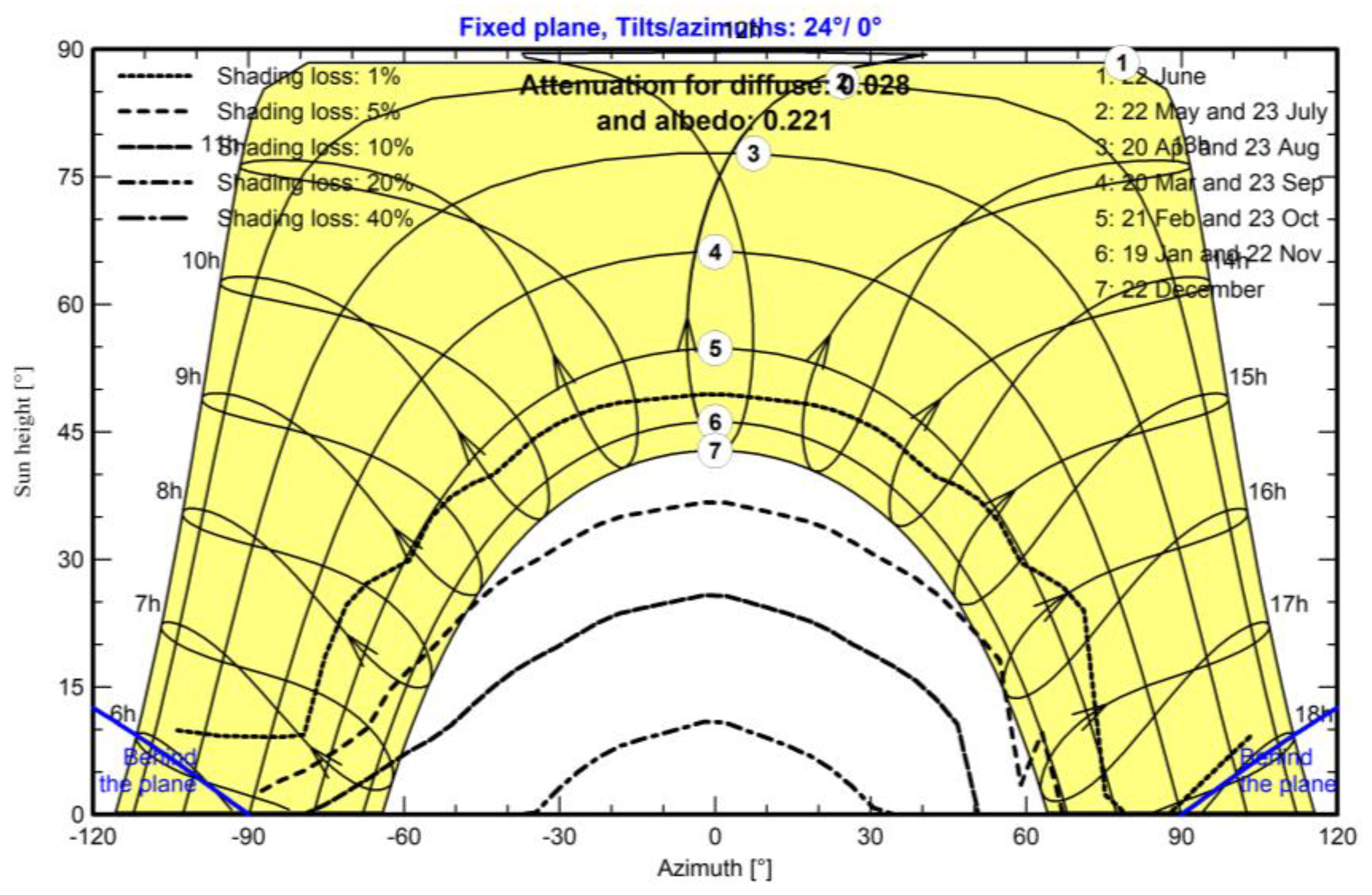

Figure 4 shows the fixed-tilt orientation parameters for the rooftop PV installation at UAP, with a tilt angle of 24° and an azimuth angle of 0°, optimal for maximizing annual energy yield at Dhaka’s latitude. The configuration yields 0.0% deviation from the optimal yearly energy yield, as confirmed by a transposition factor (FT) of 1.06, indicating enhanced irradiance capture. Annual irradiation on the tilted plane is 1634 kWh/m

2, confirming strong solar resource availability. This configuration effectively balances summer and winter generation, making it ideal for year-round operations in Bangladesh and validating the design for optimal PV performance.

Figure 5 illustrates the sun path and shading profile for the UAP rooftop with a fixed-tilt PV array at 24° tilt and 0° azimuth. The highlighted yellow region shows the sun’s annual trajectory, while contour lines represent different shading loss levels, indicating minimal obstruction throughout most hours. Seasonal sun paths (June to December) confirm favorable exposure, ensuring high solar availability and limited shading losses for the installed PV system.

The University of Asia Pacific serves as an example of the substantial potential for solar energy deployment in Bangladeshi higher education institutions, as highlighted in the discussion above. The campus is a suitable location for solar PV panel installation, as indicated by shading diagrams, panel orientation analysis, and 3D rooftop architecture. These site-specific visual evaluations demonstrate that substantial renewable energy generation can be supported by adequate sunlight and minimal shade. The campus may realistically install a solar panel system on its roof to meet a significant portion of its electricity needs, given these promising geometric and physical attributes. However, a full-scale techno-economic analysis is mandatory to identify technical and financial trade-offs and determine the optimal system size, layout, and operating strategy. To assess energy output, investment viability, and the university’s long-term economic benefits, a comprehensive techno-economic analysis is required [

1,

29].

3. Materials and Methods

This section describes the methodical technique used to assess the solar PV system’s technical, environmental, and financial performance at UAP. It represents the datasets, modeling software, simulation process, and analytical methods employed to ensure a precise and reliable evaluation.

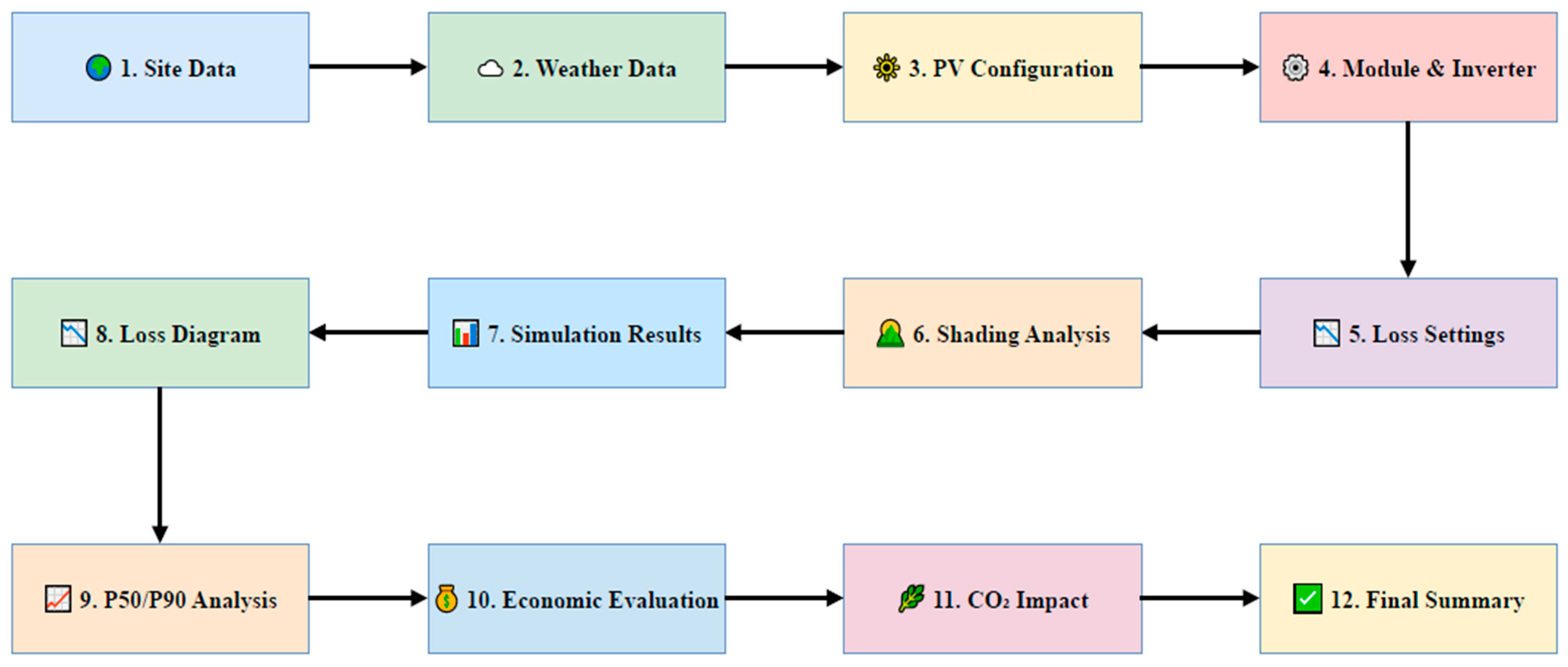

In

Figure 6, the methodology block diagram is given, from the site selection to the final summary of the design basic diagram, which follows the PVSyst simulation design process. Beginning with the gathering of site and meteorological data and continuing through comprehensive PV design, module selection, shading assessment, and loss characterization, the workflow diagram depicts the entire solar PV assessment process. Extensive economic and CO

2 impact studies, loss diagrams, and P50/P90 energy yield estimates are then produced using the simulation outputs. This methodological approach ensures the integration of technical and financial aspects into the assessment of rooftop solar systems’ practical performance. One of the study’s main contributions is the optimization of the UAP campus tilt angle, which improves energy yield accuracy and provides a valuable guideline for optimizing rooftop solar efficiency in crowded urban settings.

3.1. Case Study

The University of Asia Pacific (UAP) is one of the important universities in the capital of Bangladesh, Dhaka. The total power demand of the university is 800 KW. Powering the university continuously is very important because so much engineering work is connected with this university. In addition to preventing all types of emergency situations, using the grid-connected solar power, around 27 kW is installed on the rooftop of UAP. With solar power, the university can save 27 kW of power tariff from the Bangladesh Energy Regulation Commission (BERC). Also, the inverter complies with Bangladesh’s Grid Code. The system data is provided in

Table 1 and

Table 2. A summary of the economic factors taken into account in this study is provided in

Table 3 [

30].

3.2. Resource Data

The proposed site for the solar photovoltaic system is the University of Asia Pacific (UAP) campus, located at 23.7547° N, 90.3895° E. The University of Asia Pacific (UAP) campus is roughly 6–8 m above sea level. This data was obtained from the built-in Meteonorm database from PVsyst using the specific location by satellite data.

3.3. Orientation and Inclination, Tilting

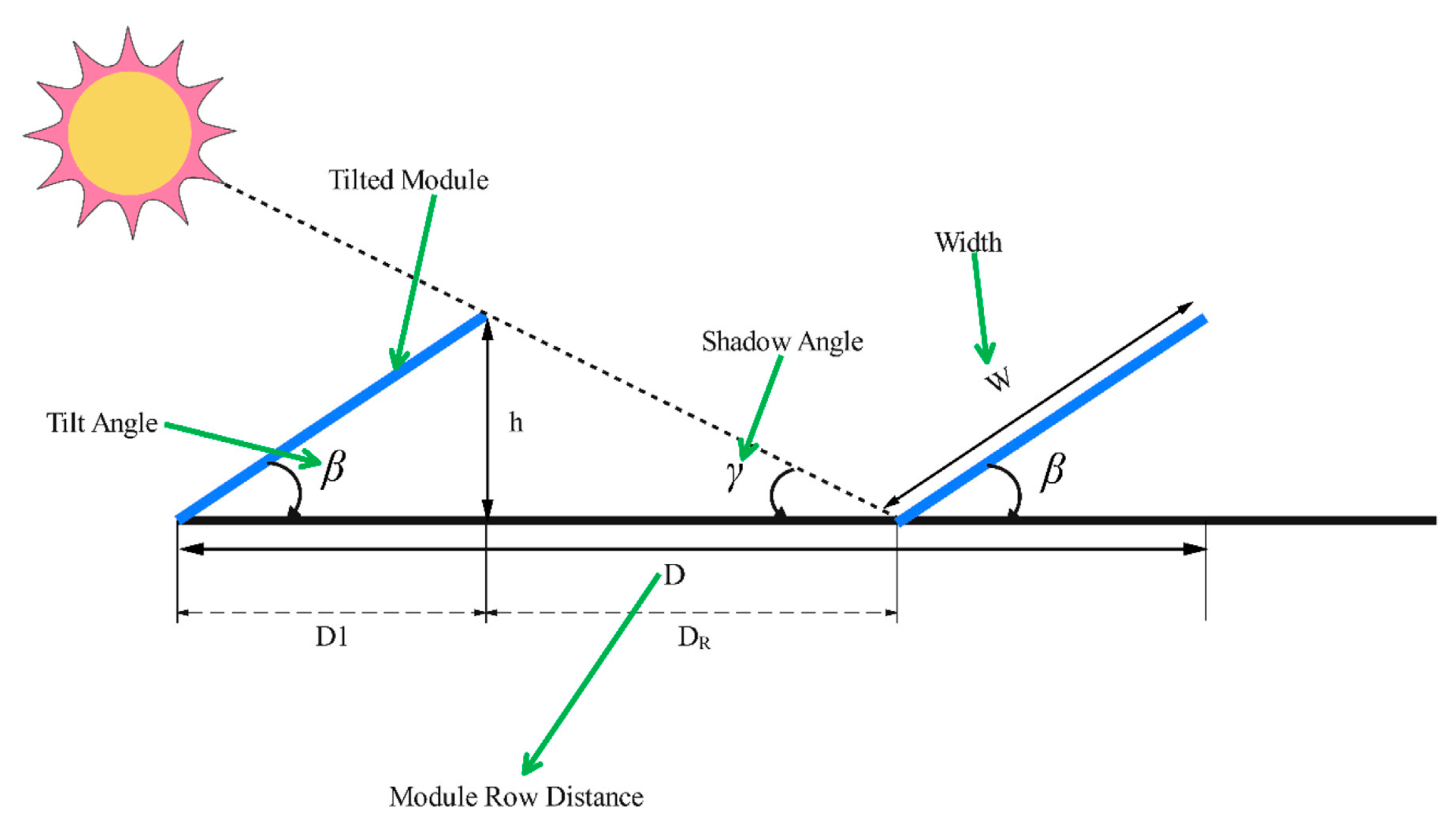

The amount of power a solar PV system can produce depends heavily on how it is set up and tilted. For optimal performance, the system needs to be set up to align with the sun’s path. Satellite data’s first analysis found that the best setup for this location is a tilt angle of 24° and an azimuth orientation of 0°. This will give the most power, and the loss compared to the best setup is 0%. The PV schematic for the space between two adjacent panel lines is visualized in

Figure 7.

3.3.1. Shadow Effect

Solar panel output is significantly reduced by shading; when any portion of a panel is shaded, the array’s overall efficiency is impacted [

31]. Panels with 25.01% and 50.1% shading can experience efficiency reductions of more than 33.72% and 45.11% [

32]. Self-shading and interrow spacing will remain important factors in solar farms, even though land availability is typically less restricted than on rooftops. It is necessary to place panels on the side that minimizes shade and facilitiates maintenance, even though this may require more space between rows and a larger land allocation [

33]. By optimizing row spacing, the examined system aims to minimize shading effects and maximize energy output.

3.3.2. Mitigating the Effects of Shadow

Shadow effects can be reduced by determining the ideal spacing between the panels. The panels should be positioned to avoid shadows from one another during the longest shadow period of the year, which is important for calculating this distance. Finding the optimal tilt angle at which the solar collector receives the most yearly radiation is the first step in this process, which has a significant impact on the PV panel’s efficiency. The height of the panel’s upper edge is then determined using the angle and panel length information from the data sheet, as shown in the following equation:

where

h is the height of the panel’s highest edge (m), adjusting for an extra ground clearance of

G (m), and

k is the panel’s length when oriented horizontally, or double its width when oriented vertically. These values can be extracted from the panel datasheet (m).

β is the tilt angle, which is the location’s latitude. The sun path diagram determines the solar tilt angle, which is then used to determine the ideal row spacing. This formula can be used to determine the spacing between the rows:

where

h is the height of the panels’ highest edge (m),

γ is the lowest solar tilt angle, and

DR is the minimum row-to-row spacing, or the distance between two successive panel rows (m). Due to its wide application in utility-scale and commercial systems in Bangladesh, a fixed-tilt PV configuration was selected for this research. Comparing this design to other tracking systems reveals that it is less expensive, simpler mechanically, and requires less maintenance. The interrow spacing was determined using standard geometric calculations based on solar altitude during the winter season or during an eclipse to minimize shading losses between rows. This method prevents performance loss from self-shading during low-sun-angle seasons while ensuring optimal land efficiency [

34].

3.3.3. Optimal Angle

The angle at which the panel is oriented with respect to the x-axis is the ideal angle. The angle must be chosen to minimize losses and optimize the annual amount of solar energy received, given the system’s fixed properties. Every day, the ideal angle for every geographic coordinate changes. It has been found that altering the tilt angle affects generation and other parameters, even when the tilt angle is changed daily, monthly, and biannually. Perhaps the most beneficial approach is to change the angle twice a year, given the costs associated with changing the system’s size and angle [

35]. A popular and cost-effective strategy is to change the panel angle by fixed degrees over the next six months, after adjusting it for six months [

36]. Maintaining a consistent angle throughout the year is given emphasis in this research because, although altering the angle may boost productivity, it would also raise expenses, particularly through greater maintenance fees and greater initial expenses for purchasing the appropriate surfaces [

37]. Throughout the year, it is customary to set the latitude angle as the panels’ default installation angle [

38].

Three options were considered for the panels’ installation angle: setting up the panels at the optimum annual angle suggested by the software, setting up the panels at their latitude angle, and seasonal installation of the panels. Ten tilt angles were chosen for this study in order to provide three important elements of information that are necessary to determine the best solution: loss with respect to optimum (%), global on collector plane (kWh/m

2), and transposition factor (FT) (software-recommended). Dynamic angle optimization and tracking systems were not considered, even though they could have increased efficiency.

Table 4 provides different orientations and tilt angles. Their greater mechanical complexity, higher capital costs, and restricted suitability for smaller commercial or industrial installations in Bangladesh were the main factors in this decision.

3.4. Proposed System Layout and Design

In UAP, a grid-connected PV system without battery storage (Case A), which is currently in operation, and a grid-connected PV system with battery storage (Case B) are the two suggested system designs. A fixed axis arrangement is used in both variants. Case B adds a battery bank; however, both systems include solar panels, an inverter, and a charge controller. By storing the extra energy generated during the day and delivering it to the loads at night, the battery bank at the University of Asia Pacific (UAP) helps control the variability in solar PV output. To avoid overcharging or deep depletion, the charge controller and inverter control the voltage and current flowing from the PV array to the battery. After that, the inverter converts the DC electricity from the panels into AC power, which may be used for basic appliances as per the university’s requirements. Case A is prioritized because the 27 kWp rooftop PV system covers only a small part of the 800 kW campus load. This makes battery integration unnecessary and not worth the cost. Net metering already provides the best use of solar energy, and the stable grid environment lowers the need for on-site storage. Case B, while better for resilience, comes with a high investment cost and offers little practical benefit given this level of PV capacity. As a result, the grid-connected PV system without battery storage stands out as the most practical, cost-effective, and workable solution for the university campus.

3.5. System Design and Assumptions

Efficiency and cost are the most important criteria when choosing components for a solar PV system, although there are other factors as well. Also, it is important to consider the imported cost of the PV panel and inverter, as well as the installation cost and inflation rate, for a better feasibility test.

3.5.1. PV Array

Available PV panels are usually either monocrystalline or polycrystalline; the former have higher efficiency and generally offer a better balance between cost and performance, while the latter are less expensive. SunPower is the manufacturer of this design, and the model is SPR-MAX2-340. The unit nominal power is 340 Wp, and the total PV module is 80, with the exact specifications.

3.5.2. Inverter

A 30 kW Sunways grid-following inverter, model number STT-30KTL, was selected for this design. The structure uses single inverters to match the 28 kW capacity of the system. The operating voltage is 180–1000 V. The DC/AC Pnom ratio is 0.91.

3.5.3. Land Area Requirement

Since the system is mounted on a university rooftop, it does not require a significant amount of space for installation and easy access during maintenance. Panel model: SunPower PR-MAX2-340.

This is only the module’s face area. Adequate space must be allowed for mounting gaps, tilt/row spacing, BOS (balance of system) clearances, and walkways. To allow for adequate space for installation and maintenance, Dhaka City was estimated using a 0.6 spacing factor.

Therefore, Total Area = 141.42 m2 × 0.6 = = 1529.74 m2.

This spacing is critical to minimize shading and optimize system performance. For better output, it is important to determine the optimal panel angle.

3.5.4. Economic Assumptions

The financial feasibility of energy projects is a major factor in making investment choices. Initial investment costs (IICs), payback time (PB), levelized costs of electricity (LCOE), and net present value (NPV) are important financial metrics. The analysis makes the assumption that all funding is provided by the institution (UAP) itself. The university is a non-profit organization. Feasibility studies, system components (such as PV modules and inverters), installation, and other related expenses are all considered capital costs. Operational and maintenance expenses are also taken into account. The return on investment (ROI) is approximately 138%, and the payback period (PP) is 4.7 years. A 20-year inverter lifespan is assumed in the study.

3.6. Losses

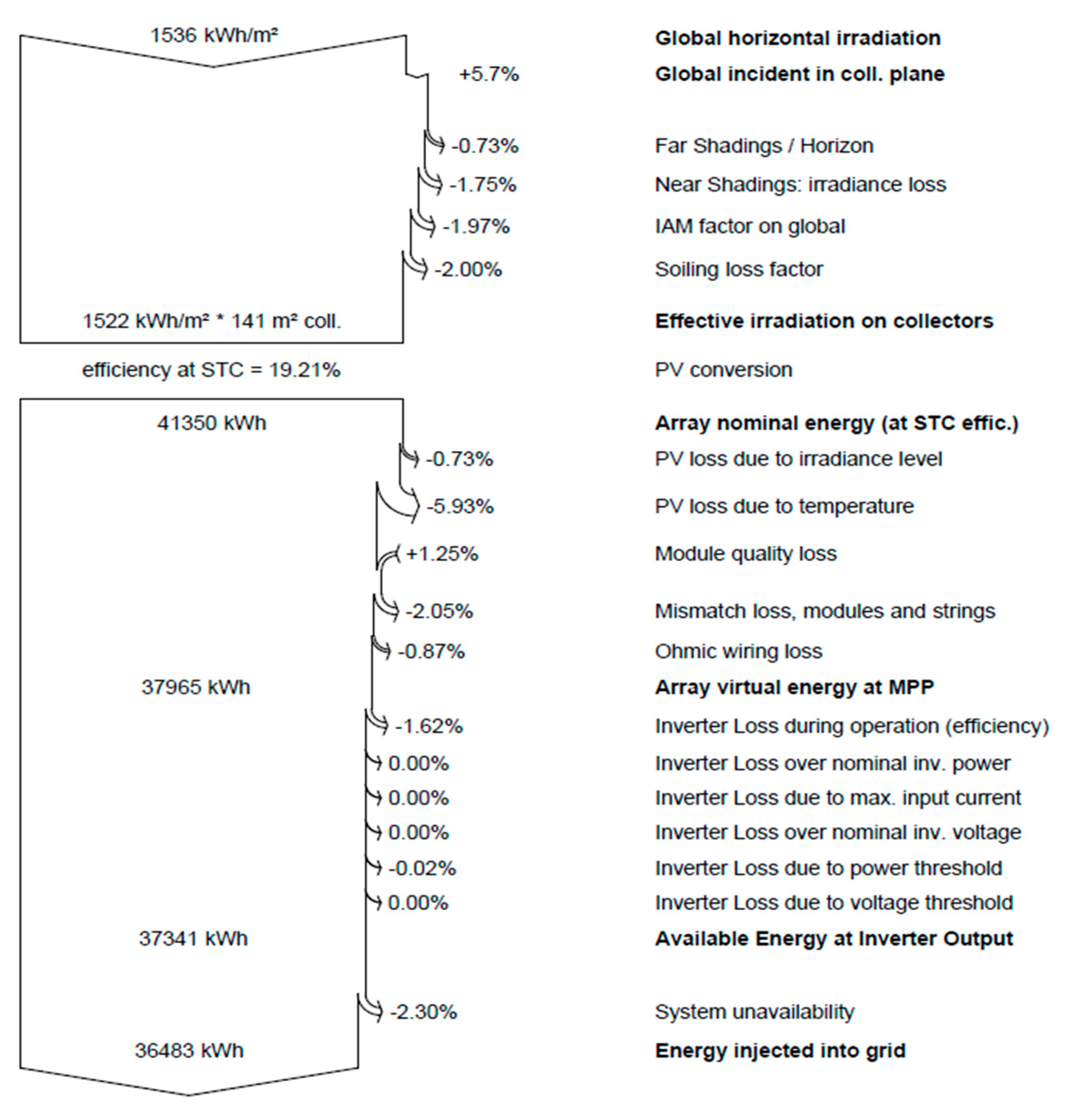

The types of losses chosen for the study were based on how frequently and quantifiably they affect Bangladesh’s typical climate. In cities that are arid or semi-arid, dust accumulation (soiling) is a significant issue. Infrequent rainfall causes dirt to remain on panel surfaces, which can lower energy yield by up to 10% if it remains unchecked. The thermal performance default algorithm in PVsyst, which takes into account efficiency loss at high cell temperatures, was used to model temperature losses. Optimized row spacing was used to reduce shadow losses, and PVsyst was assessed to ensure that there was minimal obstruction all year long. These three categories comprise the most important external loss sources for fixed PV systems in the selected locations. The loss diagram in

Figure 8 shows how shading, soiling, temperature effects, mismatch, wiring losses, and inverter inefficiencies gradually lower the amount of global irradiation that reaches the UAP site before it is added to the grid. It clearly shows the main causes of loss, with temperature and inverter efficiency being the two most important factors affecting how well the system works as a whole.

3.6.1. Dust and Soiling

One major aspect influencing PV panels’ performance is dust collection. As a case study, Iran places its panels at a shallow angle of about thirty degrees, which causes more dust to settle [

39]. According to observational studies, the modules in Tehran experienced 6.09 g/m

3 deposition after just 70 days without precipitation, which led to a 21.47% reduction in efficiency [

40]. Energy balancing costs can exceed 270 USD/MW h due to the extensive dust accumulation on panels in Iran’s southwest and west. Therefore, under such circumstances, regular cleaning is required, ideally once a week.

3.6.2. Temperature Losses

PV panels’ temperature and their surroundings have a significant impact on output energy because they affect voltage reduction, which lowers energy production. A slight increase in current cannot compensate for a large voltage loss [

41]. The efficiency of solar modules is usually measured at 25 °C under normal circumstances; however, temperature variations are common in real-world situations. An efficiency loss of up to 0.5% per °C might occur at temperatures higher than 25 °C [

42].

3.7. Methodological Justification and Comparison

This subsection explains how this modeling approach aligns with academic standards. The method was compared with published techno-economic analyses in the reputed research community. The research papers [

29,

43,

44,

45,

46] do not have a detailed discussion of the P50-P90 analysis, the LCA methodology, the IPCC and IEA-PVPS standards, and other simulation technical parameters. The proposed approach includes the following additional features.

Use of P50 to P90 probabilistic uncertainty following international standards.

Academic LCA methodology based on the IPCC/IEA-PVPS standard.

Scientific justification for using PVsyst 7.4 for modeling shading, losses, degradation, and so on.

Therefore, it can be inferred that this aim is highly rigorous academically and methodologically innovative.

4. Results and Discussion

Implementing the University of Asia Pacific’s (UAP) grid-connected solar PV system design and sizing, a simulation was run to evaluate the system’s performance under different configurations, including PV module, inverter model, tilt angle, etc. In order to assess essential characteristics—such as the energy output of the solar panels, the ISO shading diagram, and overall system efficiency—the system was modeled using PVsyst Version 7.4 in the simulation. The system configuration, statistical information, and basic assumptions formed the basis for the simulation results. We needed a total of 80 modules that covered 1529.74 square meters. We analyzed energy generation, performance ratio, and other system variables.

Table 5 presents monthly irradiation, temperature, and energy production data for the UAP solar PV system, showing how seasonal variations in sunlight and ambient temperature influence array output and grid-injected energy. Overall performance remains stable throughout the year with an annual performance ratio of 0.826, indicating efficient system operation under Dhaka’s climatic conditions.

Table 6 shows the economic performance of the proposed solar PV project. It has a net present value of USD 13,654, a short payback period of 4.7 years, and an internal rate of return of 17.15 percent, which means it is financially sound. The system’s long-term profitability and cost-effectiveness are further supported by the low LCOE of 0.0613 USD/kWh.

4.1. Energy Generation

The solar PV system produced a total of 36.483 MWh each year.

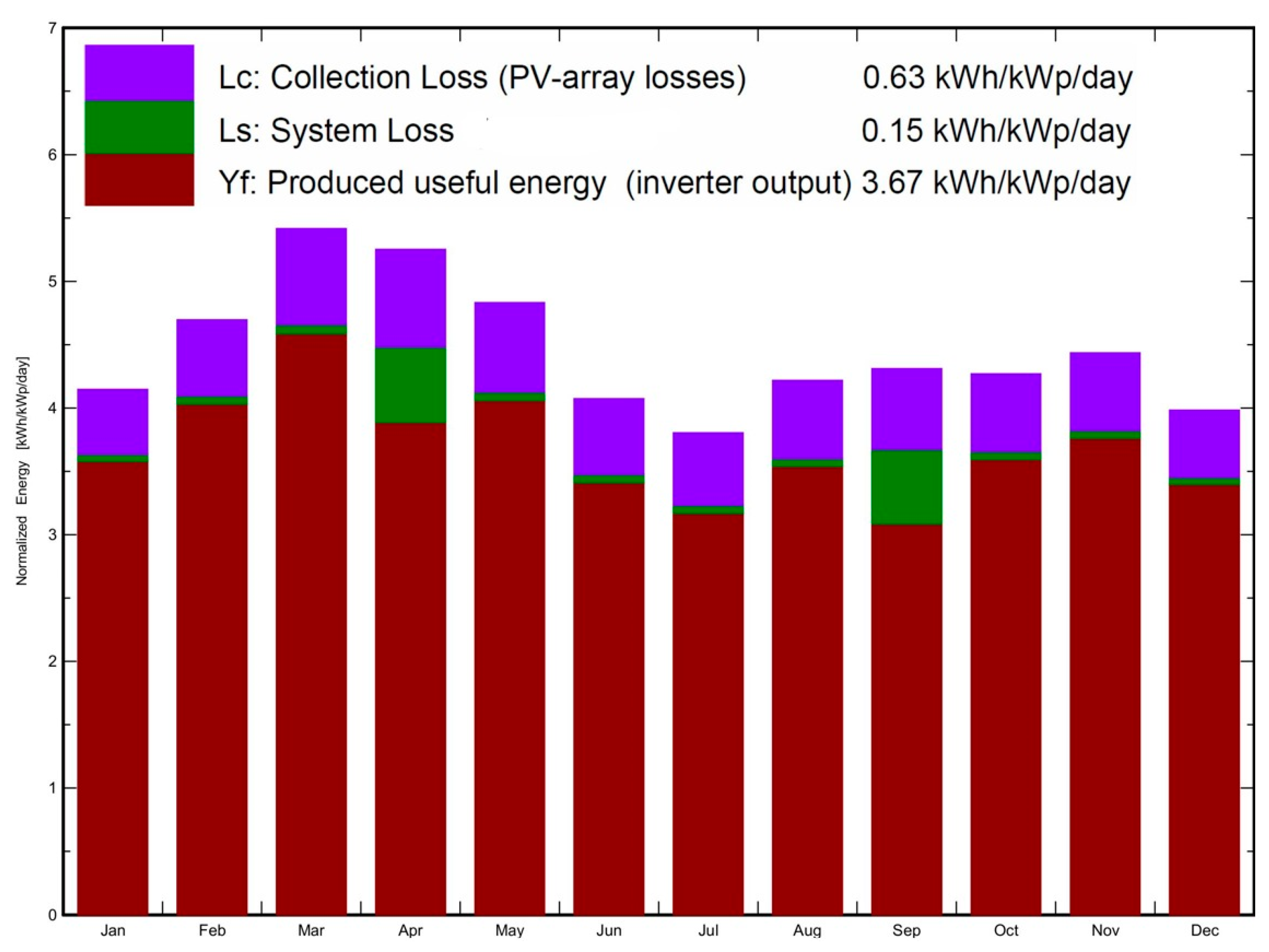

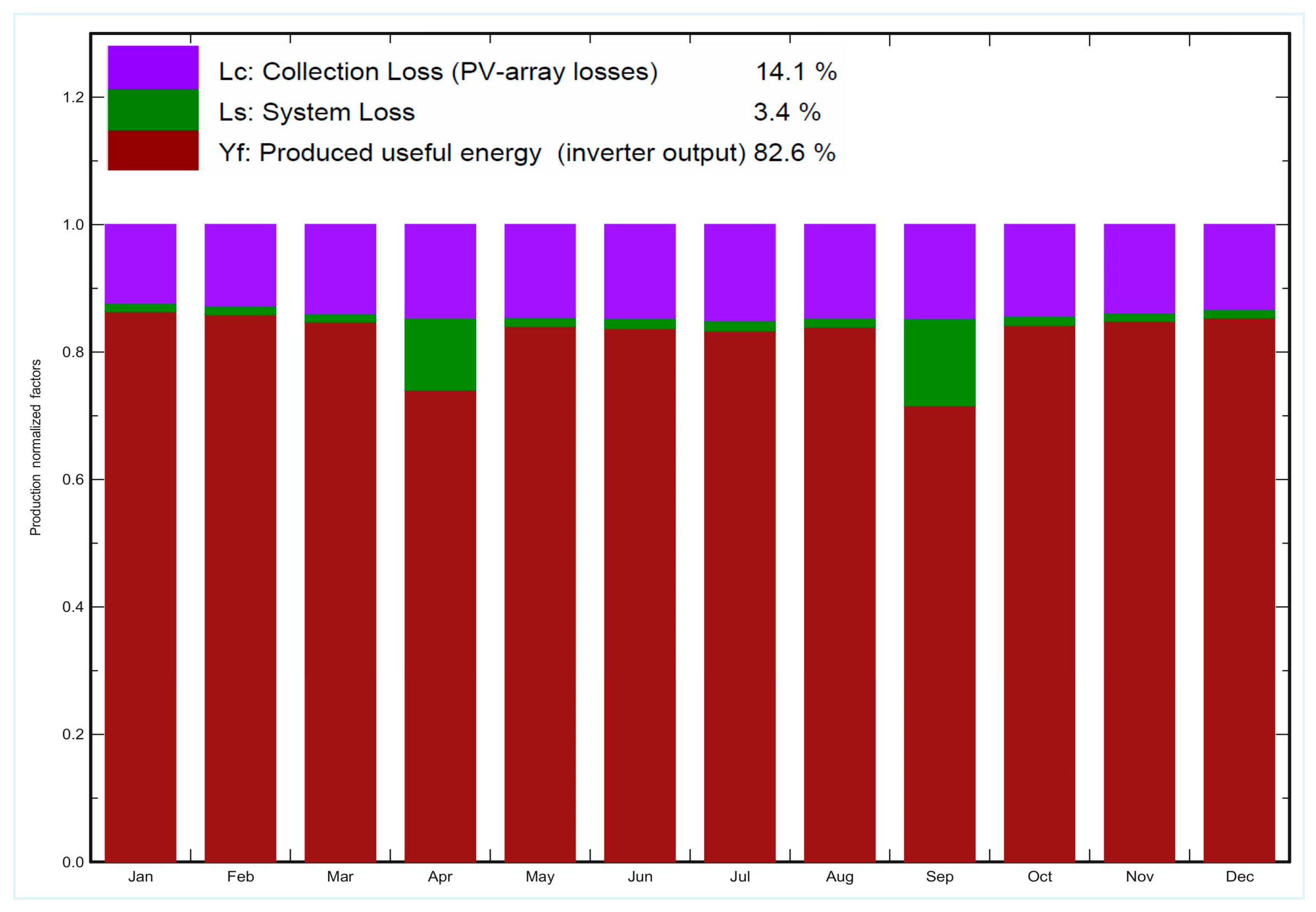

Figure 9 illustrates the monthly normalized energy output of the PV system, separating useful energy (Yf), collection losses (Lc), and system losses (Ls) throughout the year. It shows that while useful energy remains dominant across all months, collection and system losses vary seasonally, contributing to average losses of 0.63 kWh/kWp/day and 0.15 kWh/kWp/day, respectively.

4.2. Performance Ratio

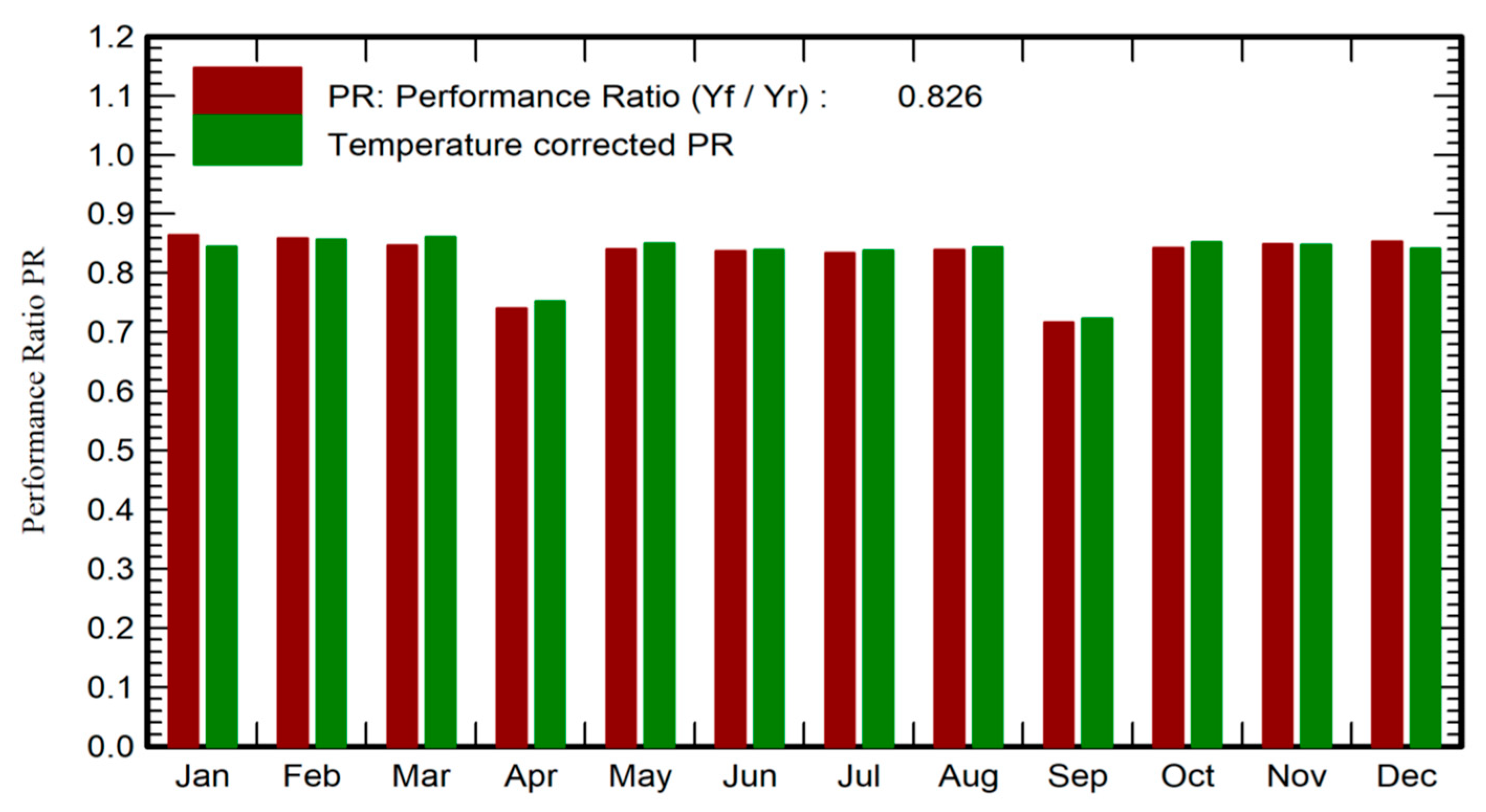

The PR for the designed system is shown in

Figure 10. The University of Asia Pacific (UAP) rooftop PV plant performs well, with an annual average PR of 82.6%. The total system losses amount to 17.42% (losses = 100% − 82.58% = 17.42%) since PR = 82.58%. The loss diagram in

Figure 10 offers a detailed look at these losses.

Table 4 presents the total energy balance and key findings of the designed system.

The system’s actual output, less any losses, is divided by the ideal output to determine the performance coefficient [

47].

where

E_Grid is the PV system’s energy yield for each year when the defined degradation rate (MW h) is taken into account,

GlobInc represents global incident irradiation on the collector plane (kWh/m

2), and

PnomPV is a specified parameter of inverters that can be defined as the PV array’s suggested nominal STC power.

Since the 1980s and 1990s, solar systems’ performance ratio has improved significantly. Performance ratios now often exceed 70%, with high-performing systems achieving 84% to 90% due to improvements in system components and shading reductions [

48]. Despite the fact that many systems reach satisfactory performance coefficients, additional optimization is required to exceed the 90% threshold [

49]. Significant inefficiencies still exist because of conversion losses brought on by temperature and current, even with improvements in solar system design and component quality. Many methods have been implemented to reduce panel temperatures, but although they improve system performance, they come with additional costs. For example, water-sprayed panels can increase power output by up to 7.7% and offer the fastest return on investment [

50]. Water-sprayed panel surfaces have a cooling effect in addition to helping with cleaning, which improves performance even more [

51]. While considering system losses, the performance ratio (PR) shows the relationship between a solar PV system’s theoretical and actual energy output. It is an important point for measuring efficiency. A higher PR as a percentage indicates better system performance. A PR of 80% is usually seen as acceptable [

52].

4.3. CO2 Emission Analysis

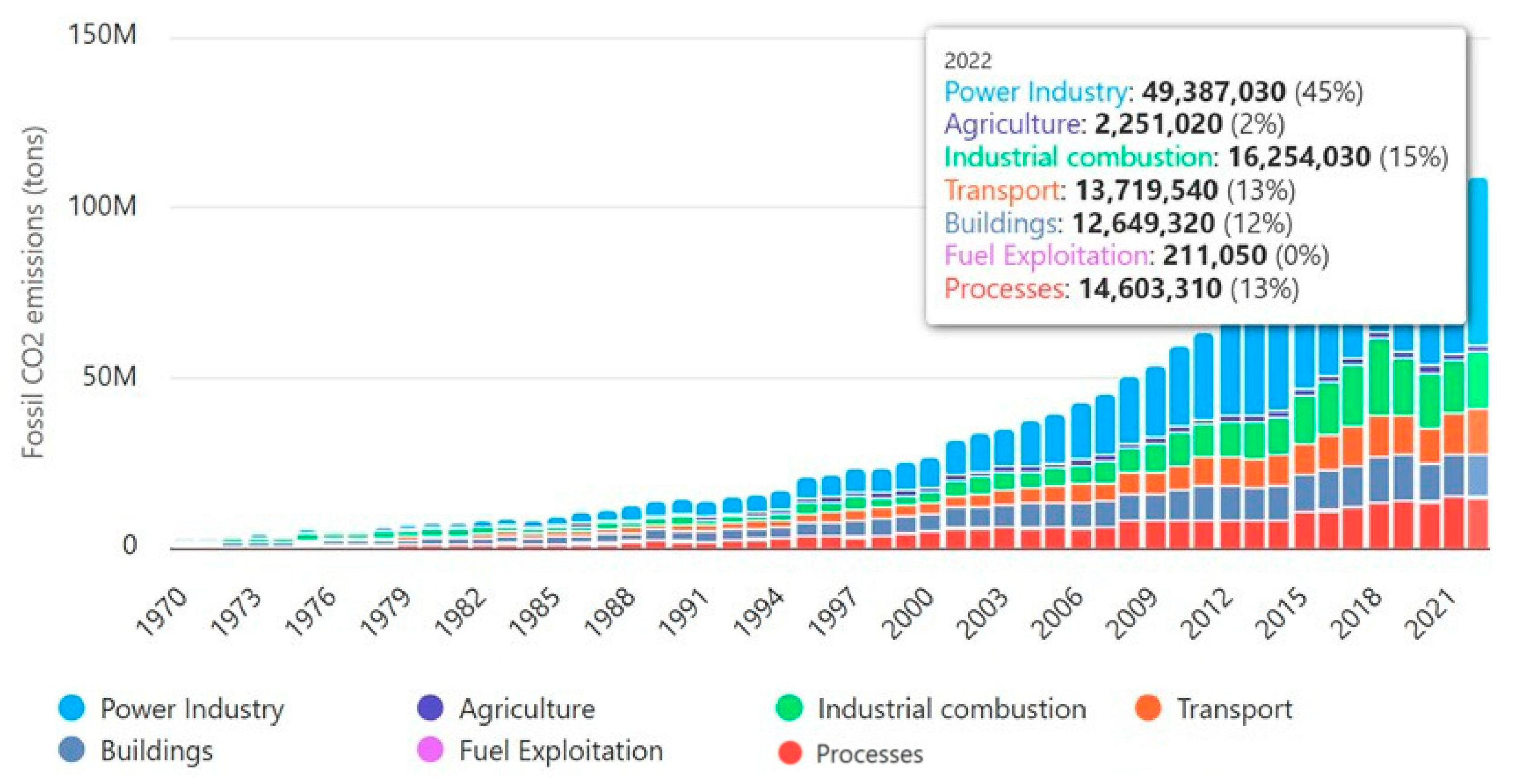

In 2022, Bangladesh emitted 109,075,300 tons of fossil CO

2. With a population of 169,384,897 in 2022, Bangladesh’s CO

2 emissions per capita are equal to 0.64 tons per person [

53], as shown in

Figure 11.

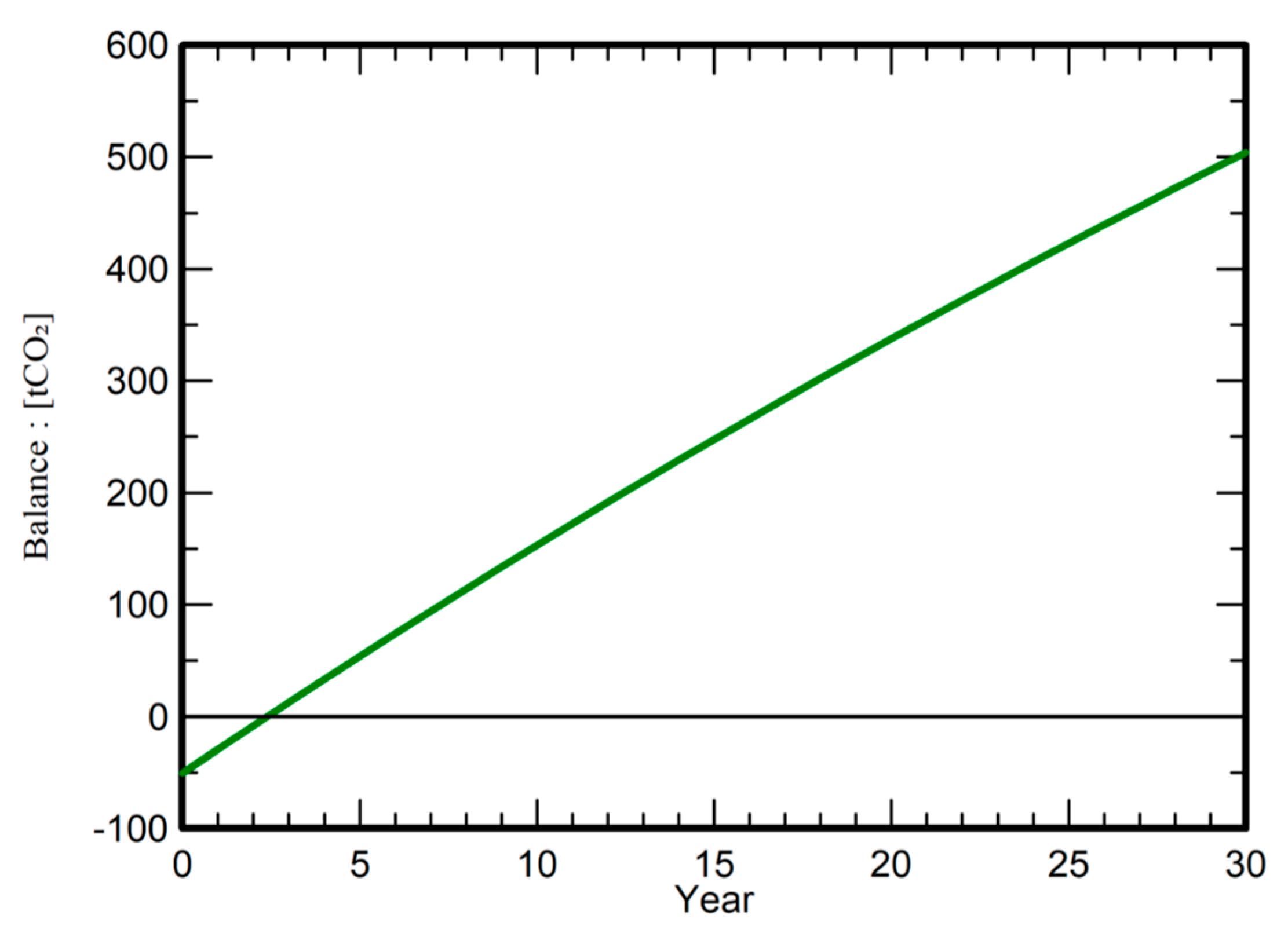

Calculating the expected CO

2 emissions reduction from installing a photovoltaic system requires using the carbon balance tool. This calculation relies on the life cycle emission (LCE) concept. It combines all CO

2 emissions related to a specific amount or type of energy. These emissions are assessed at every stage of the component’s life cycle, including production, use, maintenance, and disposal. The time variations in emissions are plotted in

Figure 12.

Although photovoltaic systems do not emit carbon when in use, they produce CO

2 during component manufacturing, transportation, installation, and maintenance. Photovoltaic systems cannot be categorized as completely carbon neutral (zero emissions) due to these indirect emissions [

54]. However, these technologies significantly reduce dependency on fossil fuels, like those found in thermal power plants [

53], and prevent CO

2 emissions during electricity generation. They also help to significantly reduce emissions of sulfur compounds, heavy metals, and nitrogen oxides [

55]. The average CO

2 emissions for each electrical unit that is injected into the system are denoted by LCE_Grid.

The total CO

2 savings can be calculated as follows:

where

E_Grid is The PV system’s energy yield for each year where the specified degradation rate is taken into account (MWh),

PL is the project’s lifetime (years),

LCE_Grid is the average amount of CO

2 emissions per energy unit for the electricity produced by the grid (gCO

2/kWh), and

LCE_System represents the total amount of CO

2 emissions resulting from the development and operation of the PV installation (tCO

2). Using an emission factor of 584 gCO

2/kWh (Bangladesh grid emission factor), as provided by the International Energy Agency (available in PVSyst), the system has the potential to reduce 51.69 tCO

2 per year. Over a 30-year project lifespan, this translates to approximately 639.2 tCO

2 in total emissions reduction.

However, in the design process, the carbon emissions during the manufacturing, transportation, and decomposition of photovoltaic systems should be considered. Therefore, the lifecycle assessment (LCA) method is used. The LCA methodology assesses and measures the environmental effects at each stage of a product’s life [

56]. This is a systematic method to identify the environmental impact that is connected with a product throughout its entire life, including raw materials collection, processing, manufacturing, transportation, installation, operation, maintenance, and even the recycling process. This is calculated by the international guidelines of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) and IEA-PVPS (International Energy Agency—Photovoltaic Power Systems Program).

This study used an 80-unit SPR-MAX2-340 PV module manufactured by SunPower [

57] and a 1-unit STT-30KTL inverter manufactured by Sunways. From the manufacturer’s data sheet [

57,

58,

59,

60]:

A1–A3 (manufacture): 136.5 kg CO2-eq/module.

A4 (transport): 5.4 kg CO2-eq/module.

A5 (installation): 0.34 kg CO2-eq/module.

C2–C4 (end-of-life, disposal): 0.55 kg CO2-eq/module.

D (recycling credit): −55.2 kg CO2-eq/module.

Net cradle-to-grave (A1–C4 + D) per module: 87.6 kg CO2-eq/module.

For 80 PV modules (80 × 87.6 kg): 7.01 tCO2-eq.

For 1 Inverter: 0.4296 tCO2-eq.

With the full system design evaluated using LCA based on IPCC and IEA-PVPS standards, the total lifecycle emissions amount to 7.44 tCO2-eq. Over a 30-year project lifespan, this corresponds to an overall emissions reduction of approximately 631.76 tCO2.

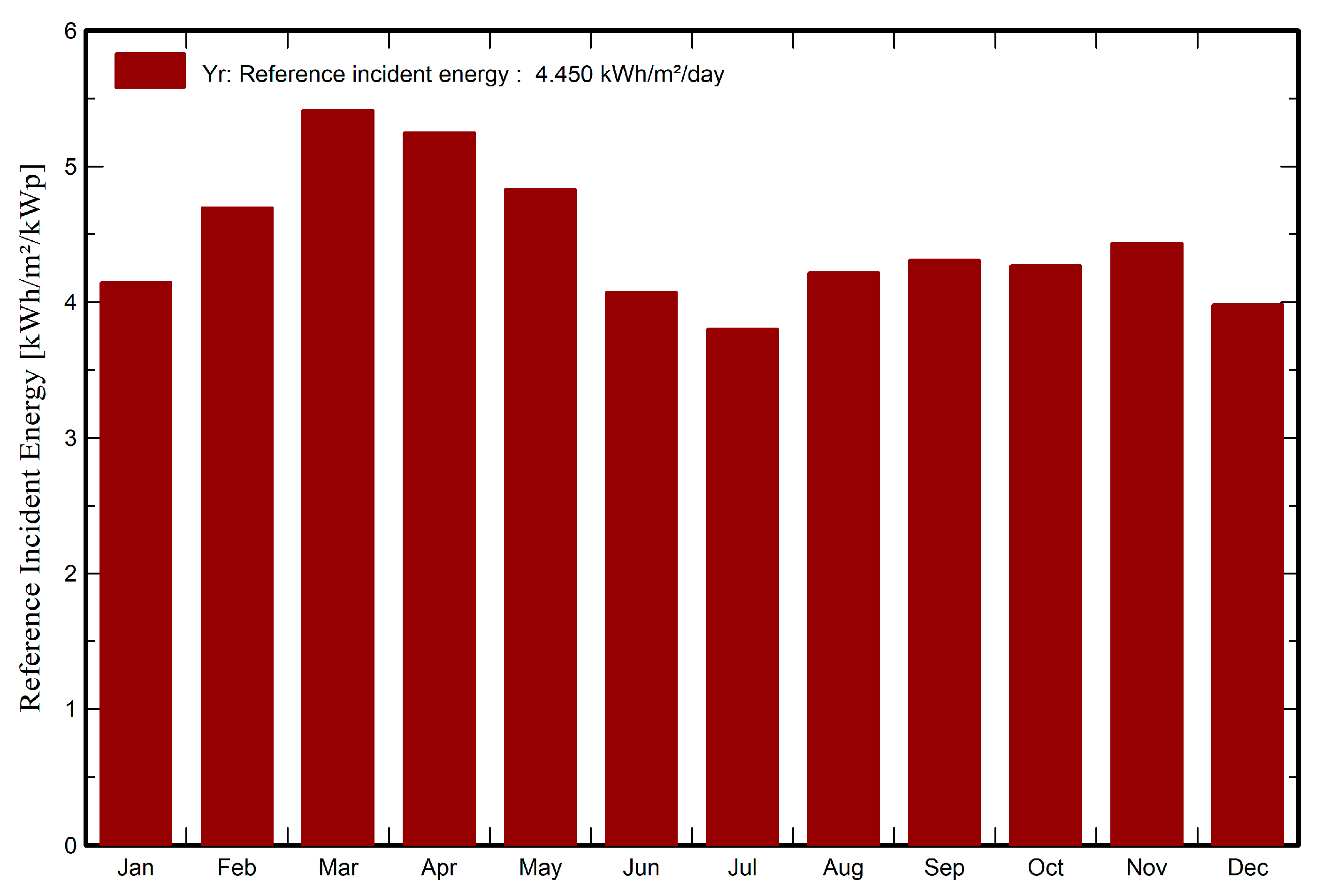

4.4. Reference Incident Energy in Collector Plane (GlobInc [kWh/m2/day])

According to Pnom and the manufacturer, the system reference yield (Yr) is the ideal array yield that is lossless. As shown, one hour is the optimal amount of time for a single incident kWh to produce the Nominal Array Power Pnom. In the array plane, Yr is the incident energy’s numerical equivalent, represented in [kWh/m

2/day] [

9]. The incident reference energy on the plane collector is displayed in

Figure 13. In March, the incident system’s energy in the collector plane was the highest at 5.49 kWh/m

2/day, while in July, it was the lowest at 3.90 kWh/m

2/day. The incident reference energy of the collection plane is 4.450 kWh/m

2/day for the whole year.

4.5. Normalized Production and Loss Factors

Figure 14 shows the normalized production and loss factors as percentages. The array yield (Ya) is the energy production of the array daily, indicated as nominal power (kWh/kWp/day). The nominal power (kWh/kWp/day) is used to express the system’s daily productive energy, or system yield (Yf). The loss of collection (Lc), which is equal to the difference between the incident reference energy in the plane collector (Yr) and the array yield (Ya), is used to calculate the losses of the array, which include temperature, connection, module quality, error and IAM losses, MPP, shading, dirt, losses of regulation, and all additional inefficiencies. System losses (Ls), which are equivalent to the difference between the array yield (Ya) and the system’s daily usable energy, or system yield (Yf), include inverter loss in grid-connected systems and battery inefficiency in standalone systems.

In this case, the loss of collection (Lc) only happens when the system uses the energy that has been generated [

45,

61]. The system losses (Ls) are 3.4%, Lc is 14.1%, and the system energy (Yf), or daily usable energy, is 82.6%. The system’s usable AC energy output, also known as the photovoltaic array’s nominal power, is measured under standard test circumstances of 1000 W/m

2 solar irradiation and 25 °C cell temperature in kWh/kWp/day. We call this the final yield (Yf).

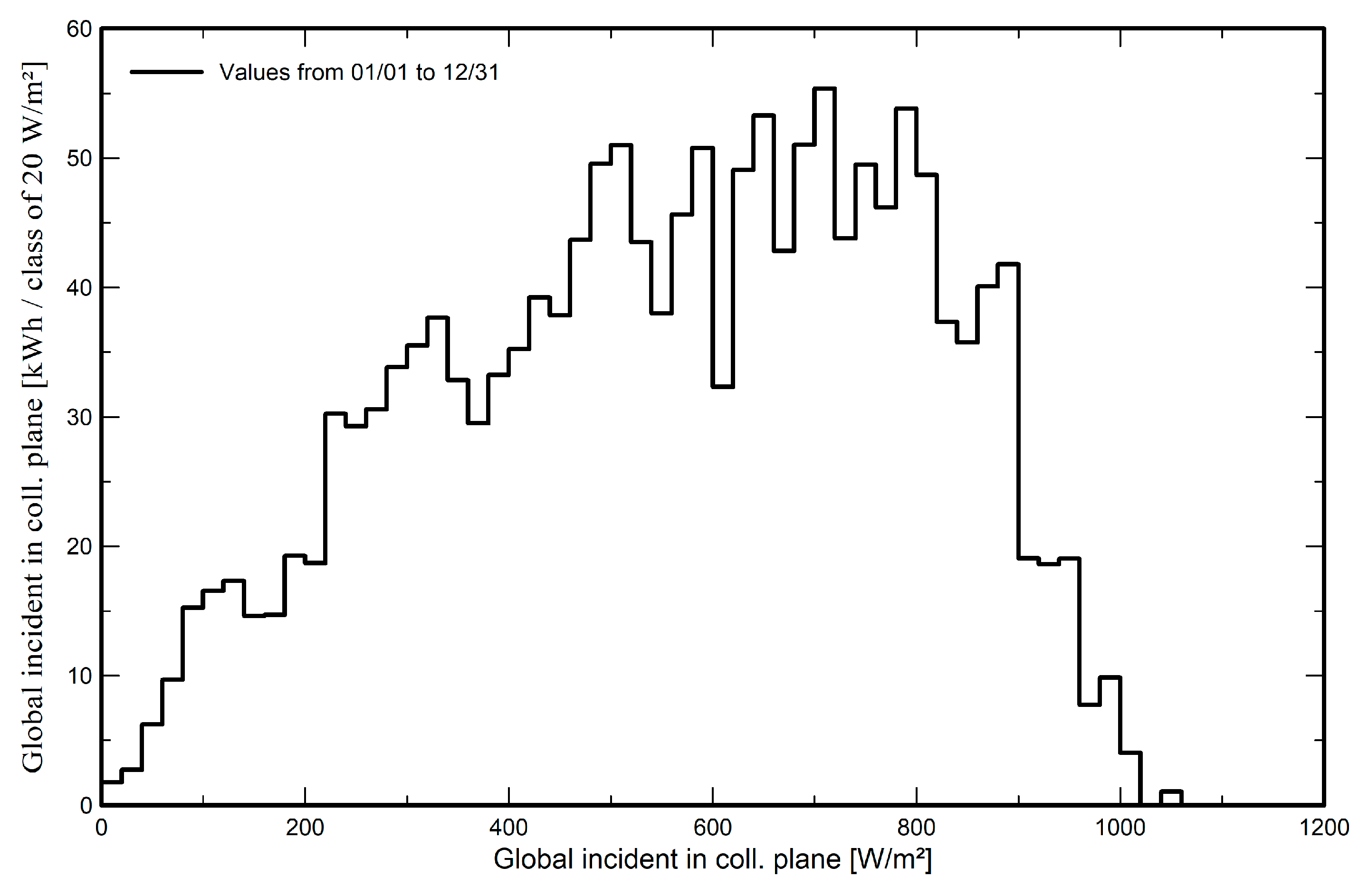

4.6. Incident Irradiation Distribution

Figure 15 shows how incident irradiance is distributed on the PV system collector worldwide. As a measure of incident global energy in the collecting plane (W/m

2), the histogram displays the total cumulative incident global energy in the collection plane (kWh/class of 20 W/m

2).

Under specific operational conditions, this area (incident global irradiance in collecting plane (W/m

2)) stores the accumulated incident global energy in the collection plane (kWh/class of 20 W/m

2) in “bins” (bars/classes). The energy deposited during each time step of simulation, where the incident global on the collection plane (W/m

2) falls between 2 values, say 500 and 520, is known as a bin/class. In this case, the “bin” ranges from 500.0 to 520.0 W/m

2. When the worldwide incident in the collection plane (W/m

2) is between 500.0 and 520.0 W/m

2, its height shows the total energy that hits the plane collection for the year [

18].

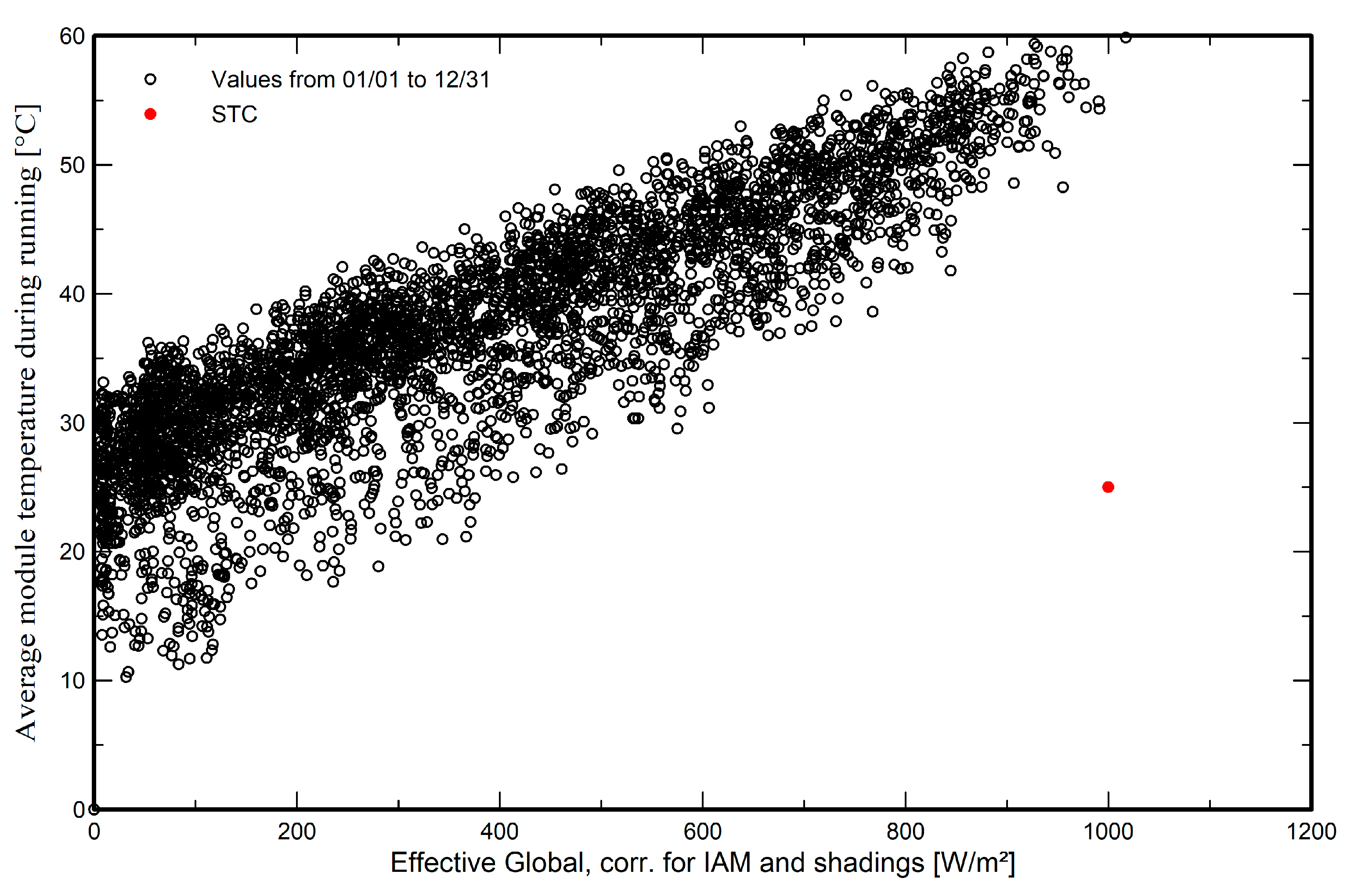

4.7. Array Temperature vs. Effective Irradiance

The array’s temperature changes as the effective irradiance changes, as shown in

Figure 16. The STC values (25 °C at 1000 W/m

2) are not too far away from the array’s temperature, which ranges from 20 to 30 degrees Celsius, but with acceptable variation between winter and summer seasons. However, ensuring the 1000.0 W/m

2 is very challenging. One of the most significant factors affecting solar panel performance is, of course, high temperatures; the STC point (25 °C at 1000 W/m

2) is shown by the red dot.

4.8. Daily Input and Output of Array

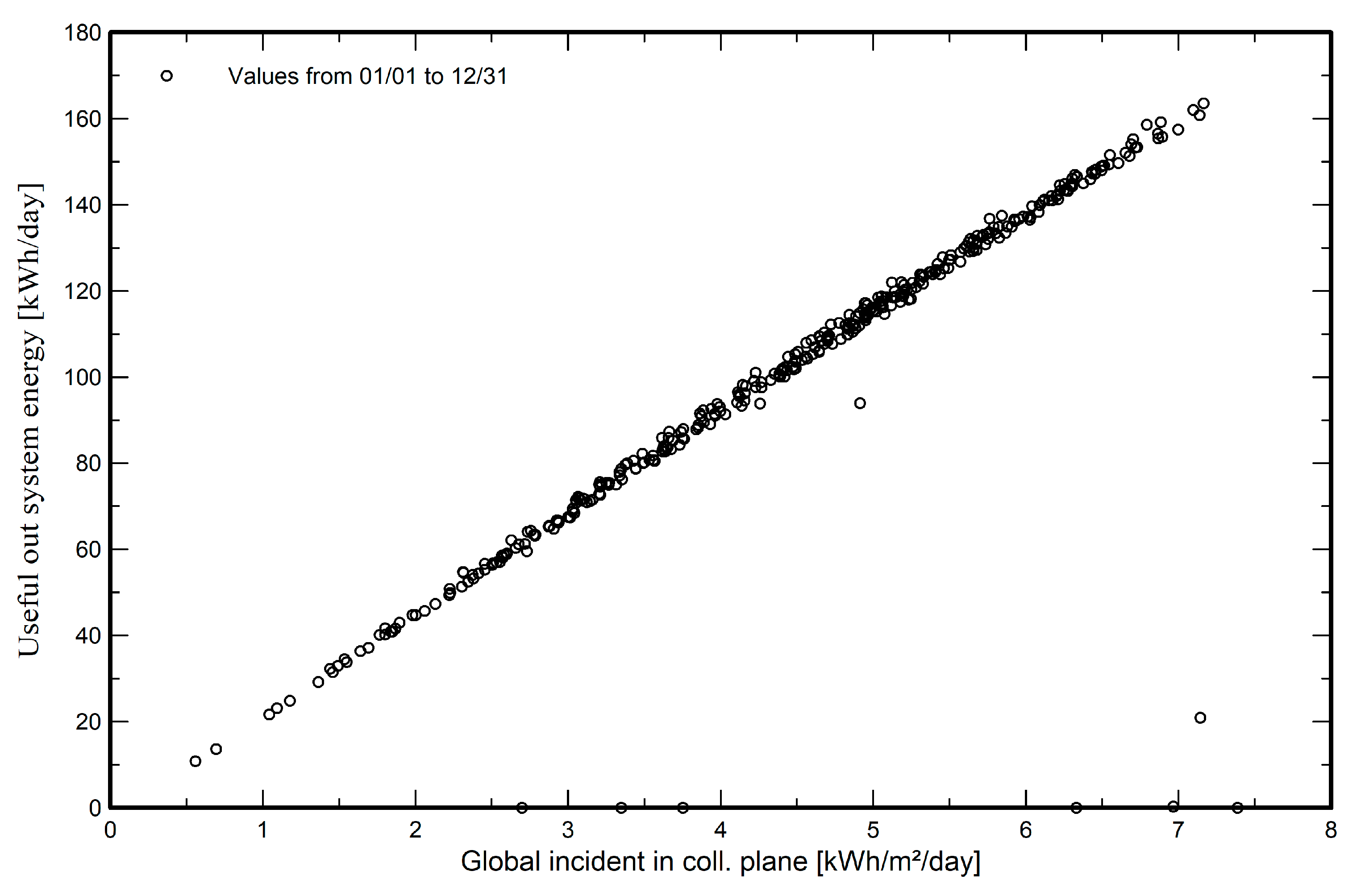

Figure 17 shows the daily input and output diagram. It presents the effective daily energy at the array’s output in kWh/day and the daily irradiance of global incidence in the collection plane in kWh/m

2/day.

Throughout the year, from 1 January to 31 December, the incident global energy in the collection plane ranges from about 1.5 to 7.0 kWh/m2/day. This graphic illustrates the annual pattern of incident global energy in the collector plane. It clearly shows seasonal changes, with peak values in the summer.

4.9. Effective Array Power Distribution

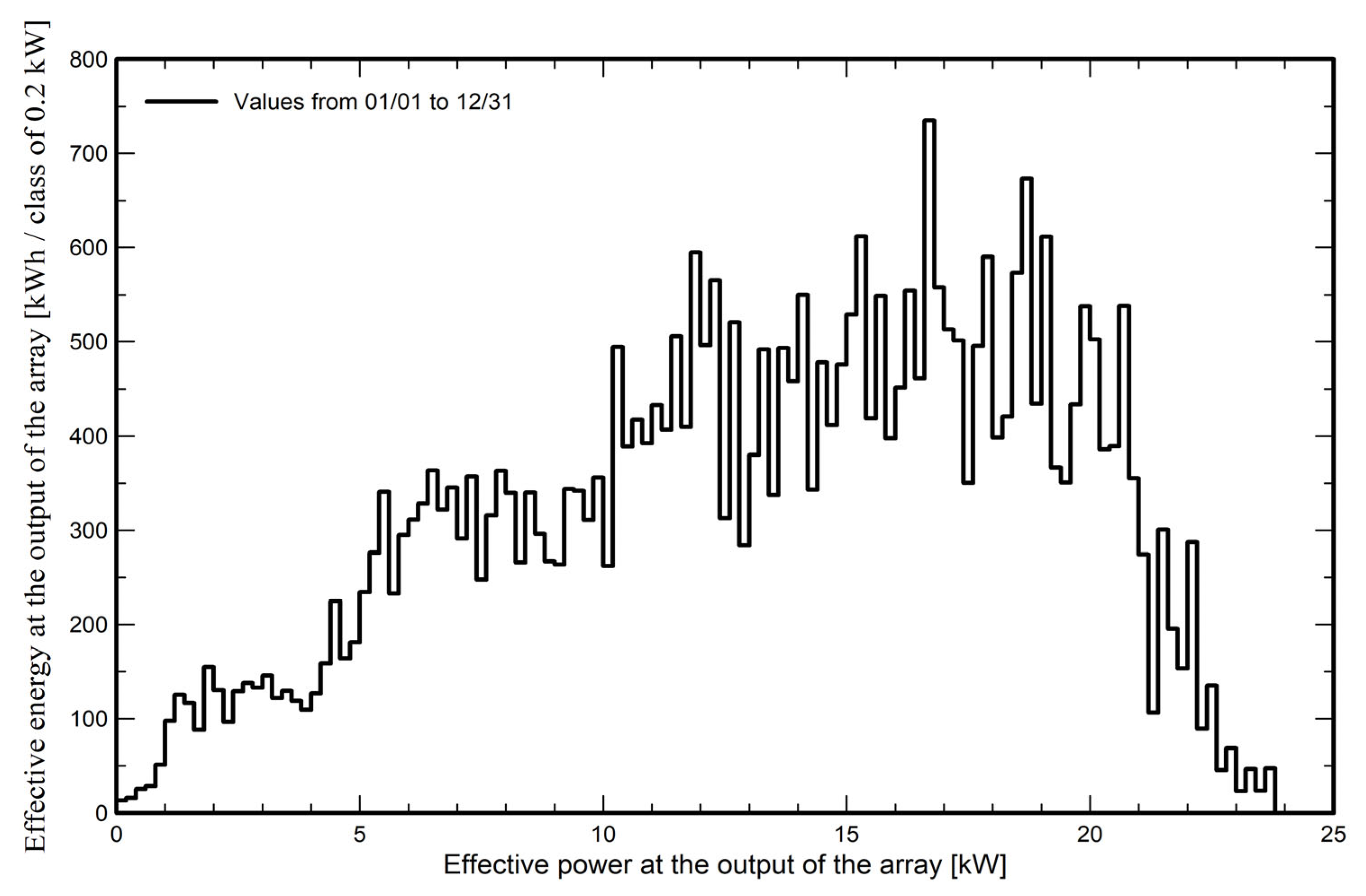

Figure 18 illustrates how a photovoltaic (PV) array’s effective power output is spread over a 12-month period, from 1 January to 31 December. The y-axis displays the corresponding effective energy produced (in kWh) for each class of 0.2 kW, while the

x-axis depicts the effective power at the array output (in kW). The curve peaks around 16 to 17 kW. It shows that most energy production occurs between 10 and 20 kW, indicating this is the range where the system works best. The histogram represents the effective energy distribution at the array’s output (kWh per class of 0.2 kW) based on the array’s effective power (W). This region (effective power at the array’s output, W) stores the accumulated effective energy at the array’s output (kWh per class of 0.2 kW) in “bins” (bars or classes) [

62,

63].

4.10. PV Panel’s P-V, I-V, and Efficiency Analysis

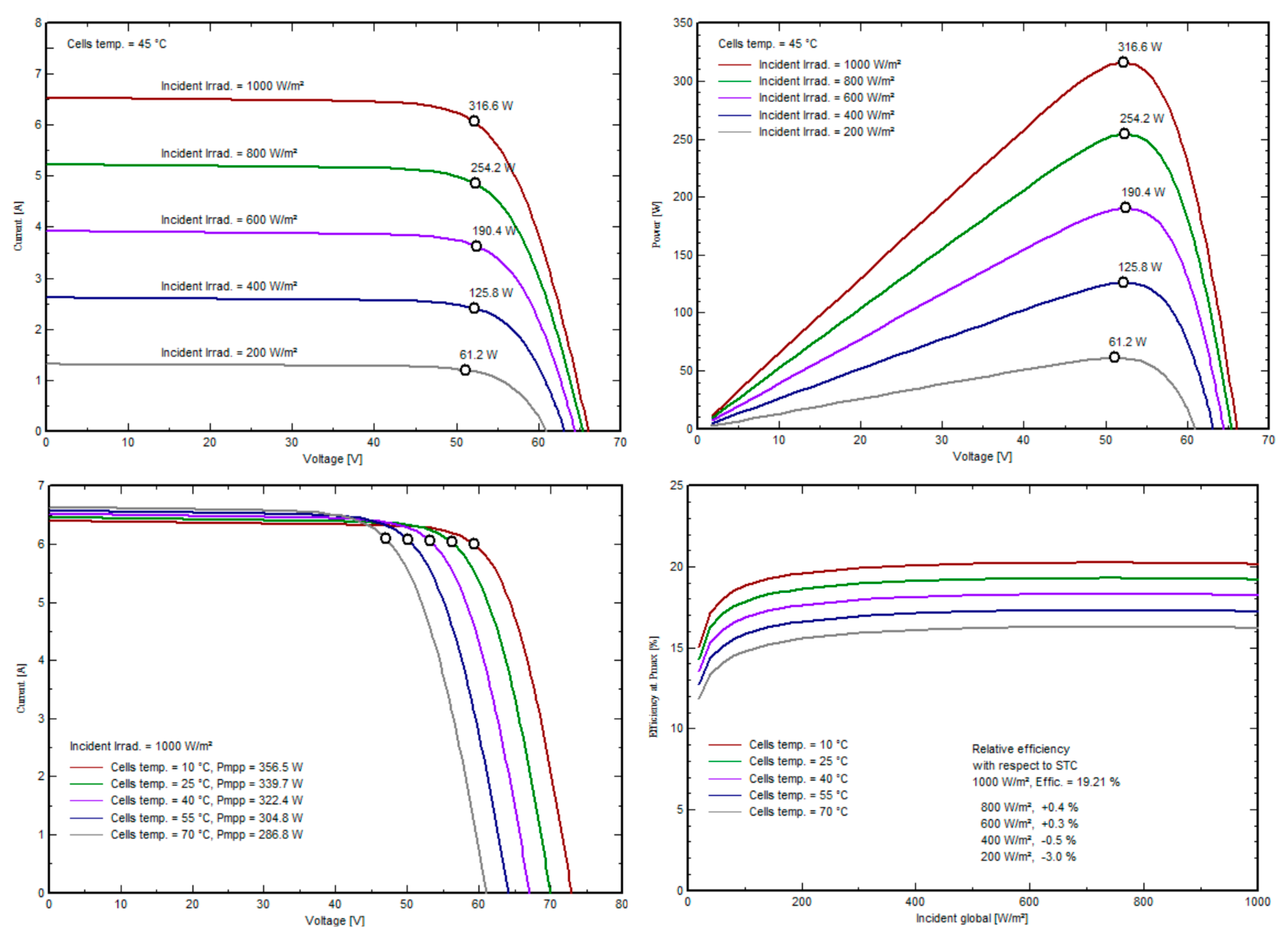

Voltage-current and voltage-power values for a specific STC module (1000 W/m

2, 25.0 °C) are represented by the I-V and P-V curves in

Figure 19. These curves are some of the most important features that show how well a module is working. The I-V and P-V curves can help determine several key numbers, including the maximum power point (Pmax), short-circuit current (ISC), and open-circuit voltage (Voc). The open-circuit voltage (Voc) is the highest value reached when no current flows from the module. The current through the solar PV module is called short-circuit current (Isc) when the voltage across the module is 0 or when the solar cell is short-circuited. The most important values of the linked voltage and current product are called the maximum power point (MPP) [

64]. The PV panel’s P-V, I-V, and efficiency curves at different temperatures and solar radiation levels are shown in

Figure 20. High temperatures negatively affect solar panels. For instance, at 1000.0 W/m

2 of solar radiation and a temperature rise to 70.0 °C, efficiency drops to 15%. In contrast, at 40.0 °C, efficiency increases to 17.5%. This highlights the significant damage that high temperatures inflict on solar energy systems. At 25.0 °C and 1000.0 W/m

2 of solar radiation, the highest power and panel values of efficiency are 316.6 W and 316.6 W, respectively.

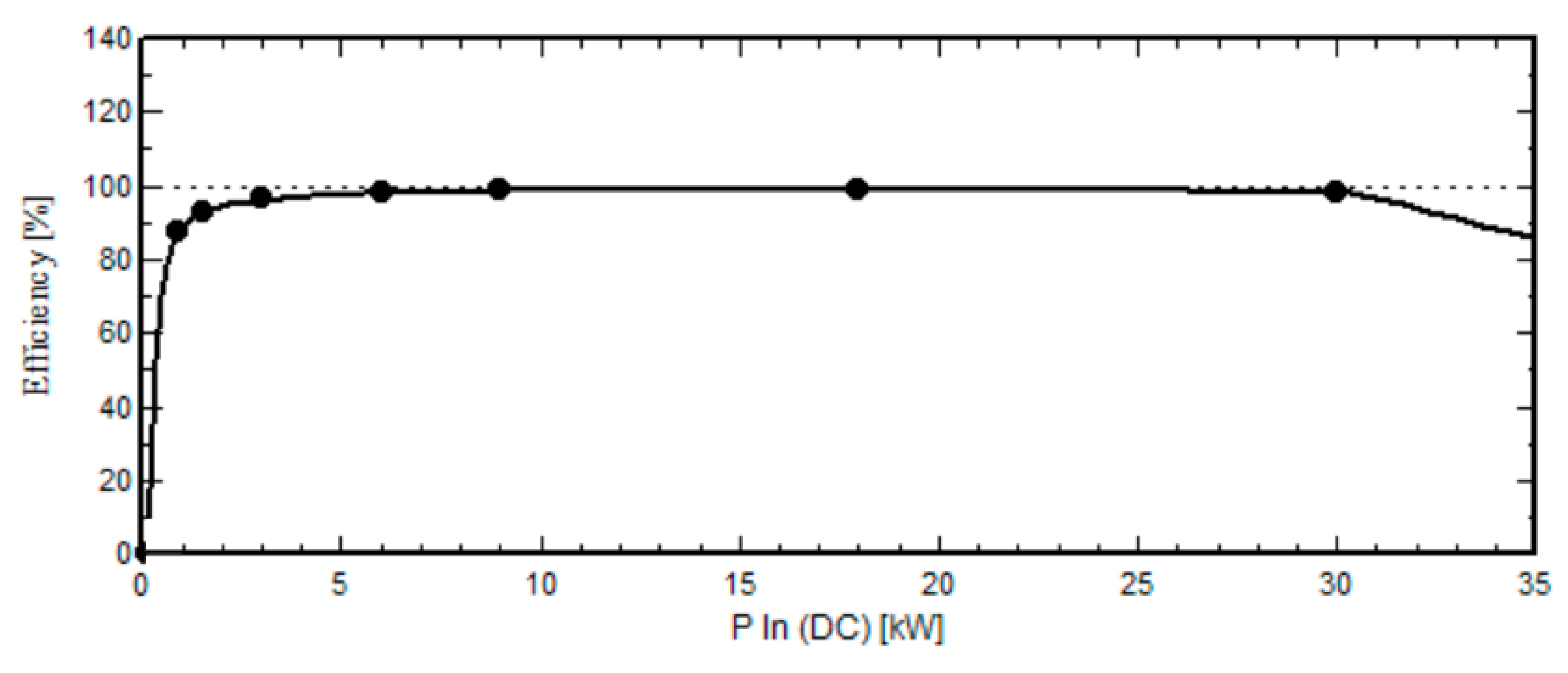

4.11. Inverter Efficiency

Although the inverter serves as an interface between the station’s components and the loads, it is considered one of the most crucial parts of the system. The inverter efficiency is visualized in

Figure 20. In addition to converting direct current to alternating current, it is responsible for charging and discharging batteries in a way that maximizes their lifespan and safety, with an integrated charging controller. The inverter’s efficiency is linearly related to the system’s energy generation.

Therefore, excellent efficiency across the whole power range is necessary for good system performance. The equipment’s voltage input, power input, and load fraction all affect the inverter’s efficiency, which is the percentage of the power input converted to output. The inverter efficiency reaches 97.0%, as shown in

Figure 20, which indicates that the panels and loads the inverter was selected for are appropriate [

65].

4.12. P50-P90 Evaluation

A statistical technique frequently used in photovoltaic (PV) generation evaluations to measure production uncertainties resulting from both technical and meteorological factors is the P50–P90 evaluation. Meteonorm 8.1 data (1991–2012) was used in this study, generating synthetic multi-year monthly averages with a 5.0% year-to-year variability and a 5.3% overall global variability found by the quadratic summation. PV module modeling (1.0%), inverter efficiency (0.5%), soiling and mismatch (1.0%), and degradation (1.0%) are among the simulation-related uncertainties that affect long-term performance projections.

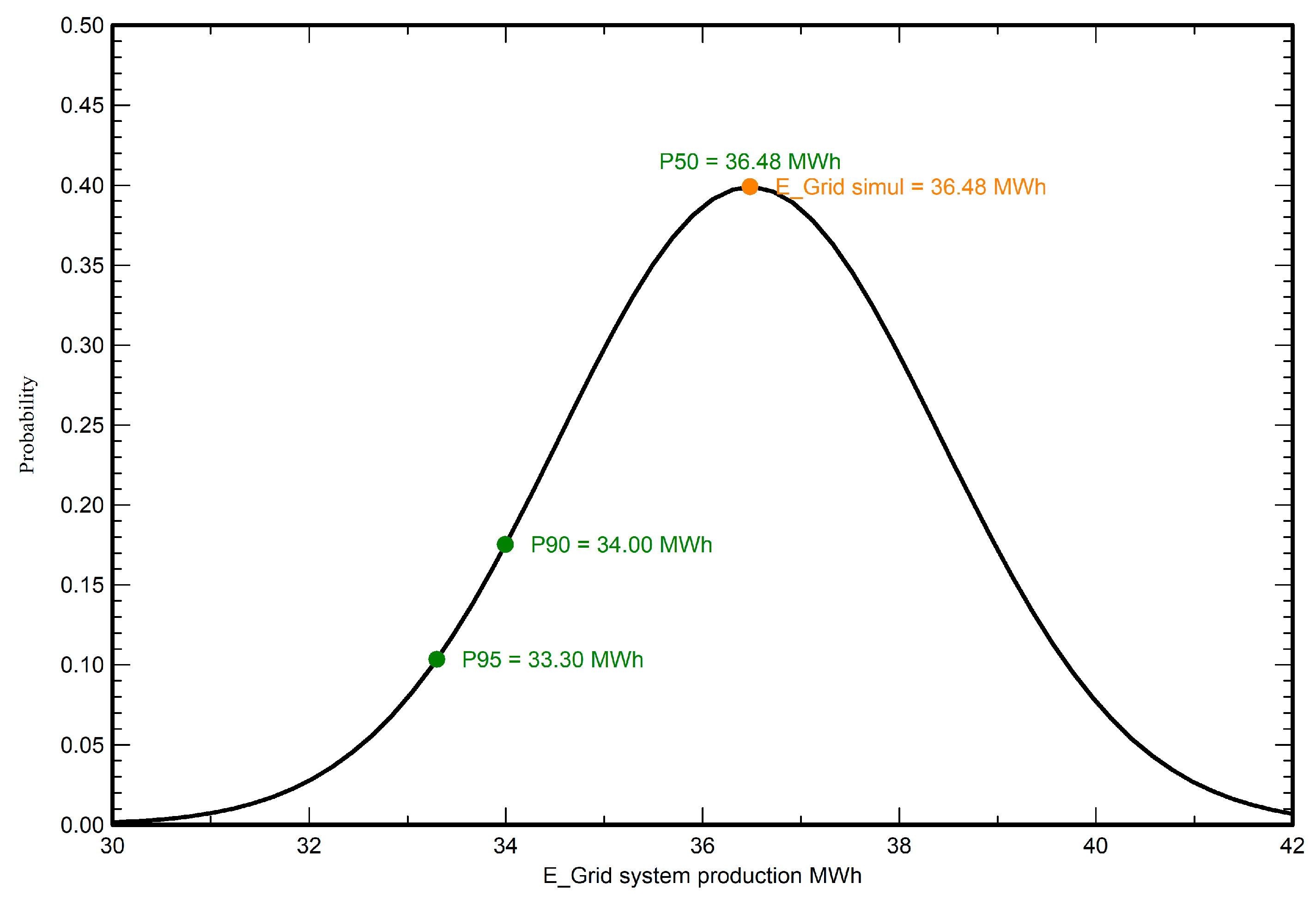

With a standard deviation of expected output of 1.94 MWh between P50 and P90, according to

Figure 21, the annual production probability was found to be 36.48 MWh (P50), 34.00 MWh (P90), and 33.30 MWh (P95). In this case, P90 and P95 offer more optimistic projections with 90% and 95% certainty, respectively, making them particularly useful for financial risk assessments in the development of solar projects, while P50 represents the median production estimate with equal chances of exceeding or underperforming.

4.13. Economic Analysis

Solar panel prices have dropped by about 20% while global capacity has doubled [

66,

67,

68]. The solar tariff of Bangladesh has dropped 38% to 8.2 cents [

69]. In

Table 7 and

Table 8, installation costs with the PV panel, inverter, and other costs are given, along with operating costs, which are not regularly connected to the whole system, such as repair, cleaning, security, and so on. The economic viability of solar is evident in the levelized cost of energy, which is 0.061 USD/kWh. This cost is much lower than the average cost of electricity generation in Bangladesh from fossil fuels. Even without significant subsidies, small- to medium-sized rooftop and grid-tied PV systems can quickly become profitable, with a payback period of 4.7 years.

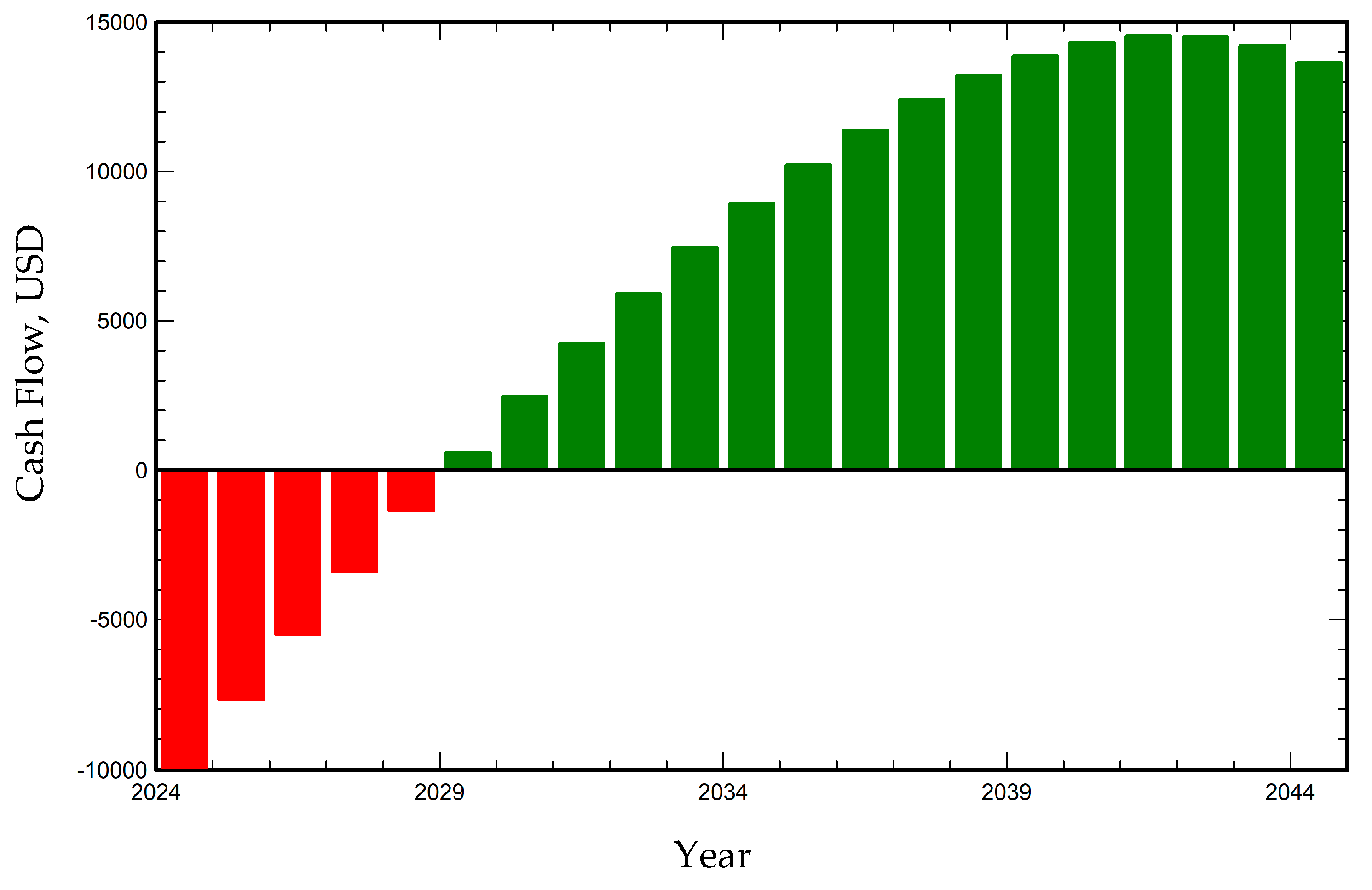

Figure 22 is the cumulative cash flow (USD). Unlike the volatile fossil fuel markets, solar projects offer stable, long-term investment opportunities. The financial statistics show a return on investment of 137.5% and an internal rate of return of 17.15%.

4.14. Sensitivity Analysis

Several significant sensitivities affecting project performance and financial viability are revealed by the PVsyst simulation for the 27.20 kWp grid-connected University of Asia Pacific rooftop system in Dhaka. A 5.3% combined uncertainty leads to a P90 estimate of 33,997 kWh. This shows that the yearly energy yield of 36,483 kWh (P50) is highly sensitive to annual weather conditions. Even the higher-order effects of parameter changes are captured by the total Sobol sensitivity index. For local coordinated operation and plant-level control of the solar PV plant, we employed PSSE.

A techno-economic analysis of a hybrid renewable energy system is introduced in [

70]. Renewable energy sources are becoming more popular in Bangladesh [

71]. Loss considerations greatly affect productivity. Thermal loss and soiling rate are two important parameters of sensitivity analysis. The drop of PV module efficiency due to the increase in temperature in the PV module with respect to STC 25 degrees Celsius is known as thermal loss. Thermal loss is calculated by the manufacturer’s given specifications. Thermal loss varies with different temperatures in different regions [

72]. The soiling rate, which is the loss due to the dust, dirt, and pollution on the PV module surface, reduces the power output because it does not absorb sunlight properly [

73]. The soiling rate is considered or calculated by the geological location and other weather parameters. A key sensitivity is a 2% soiling loss. Higher dust accumulation, common in Dhaka, can significantly reduce yield and emphasize the need for a strict cleaning program. Thermal losses worsen due to the system’s high operating temperatures, which reduce efficiency. For nighttime power supply, such as a low-consuming load of a university, the power can be provided by a BESS (battery energy management system). However, the BESS has some constraints, such as the high cost of the battery, maintenance, monitoring, and so on. There are also some institutional barriers, such as a lack of straightforward policies, delays in approval, limited internal technical expertise, utility-side delays, and a lack of interest in large-scale PV projects. However, as a solution to emphasize the PV power projects, a multi-energy trading market can be introduced, where users can utilize the power from different sources, like the conventional grid or sustainable PV power. Using a hierarchical reinforcement learning algorithm, the energy conversion is matched to different energy types [

74]. It means breaking a complex task into smaller sub-tasks to improve efficiency of work and sustainability. Inflation and operating expenses significantly affect the economic outcome. The projected 9% inflation rate increases OPEX, extending the 4.7-year payback period and increasing the LCOE to USD 0.061/kWh.

To more accurately reflect actual financial circumstances, we also performed a sensitivity analysis by varying the discount rates by different percentages from 0% to 10%. These findings make it evident how LCOE and NPV vary depending on the discount rate. This increases the validity and dependability of our economic outcomes. The results are given in

Table 9.

The estimated 639.2 tons of CO2 savings over 30 years are subject to long-term risks from component degradation and parameter uncertainty. Sensitivity studies help determine how a system responds when key parameters—such as temperature, capacitance, inductance, duty ratio, and insolation—change.

6. Conclusions

This study evaluated the financial viability and feasibility of installing a grid-connected solar PV system at the University of Asia Pacific, Green Road, Dhaka, Bangladesh. An 80-module, 27.2 kWh fixed-tilt system can inject 36.48 MWh of energy annually into the Bangladesh National Grid, based on modeling and simulation. With a levelized cost of energy of 0.061 USD/kWh, the system generates power at a competitive rate compared to Bangladesh’s typical electricity rates. It has a payback period of 4.7 years and an internal rate of return of 17.15%. The system has an average performance ratio of 82.6% and saves over 16.8 tCO2 each year. The proposed system helps Dhaka city reduce carbon emissions and provides a reliable, long-term power supply. However, its effectiveness may vary depending on where it is used, such as in certain areas or under specific partial shading conditions. Dhaka receives a substantial amount of sunlight each year, around 1536 kWh/m2. Because of this, it is a suitable location for solar PV systems, whether on rooftops or on the ground. Incorporating new module technologies, improving spacing, or adding monitoring systems to the design could also significantly boost energy output and profits.

Although the study mainly relies on PVsyst 7.4 simulated data, we included real-world constraints to improve the analysis. These constraints include measured campus load profiles, location-specific weather data, actual PV module and inverter specifications, shading conditions, the inverter efficiency curve, installation tilt and azimuth, and local economic factors. These practical inputs help ensure that the simulated results accurately reflect real operational behavior. In future work, on-site performance monitoring will be added to further confirm the findings. In summary, installing solar PV systems for urban and community loads in Bangladesh offers a viable way to provide low-carbon, sustainable, and reasonably priced access to electricity.