A Monotonic and Continuous Frequency Control Method Covering Constant-Current and Constant-Voltage Charging Processes for Series-Series WPT Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Additional DC/DC converters can be used in the WPT system to regulate the output voltage/current [4], which is a simple method in terms of control but will increase power conversion stages.

- (2)

- Phase-shift modulation or pulse density modulation can be applied to the inverter for output regulation. As a basic control method, phase-shift control [5] is widely used in WPT systems. However, it is challenging to maintain soft-switching in the whole charging process and under various coupling conditions for phase-shift control. Pulse density modulation is used to regulate the output power of a WPT system in [6]. However, pulse density modulation tends to introduce low-order harmonics and eventually may lead to large fluctuations in the output current.

- (3)

- Active rectifier can be used to regulate output power [7], and it can achieve a fast response compared to passive rectifier [8]. This can address the delay issue caused by the wireless communication between the transmitter side and the receiver side. However, synchronization between the two sides will increase the complexity of the control system, which may degrade the robustness of the system operation.

- (4)

- Variable parameters (usually inductance [9], capacitance [10], or the combination of inductance and capacitance [11]) and variable topology [12] are introduced to adjust the output characteristics of WPT systems for different charging conditions. However, this kind of method suffers from extra switches and also high voltage/current stresses of the additional switches.

- (5)

- Frequency control is another widely adopted method for realizing output regulation [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] for WPT systems, especially for series-series (SS) compensated WPT systems. Compared with other methods, frequency control requires no additional devices and may achieve zero-voltage switching (ZVS) in the whole charging process and in a wide coupling range.

- (1)

- The WPT system is designed to avoid frequency splitting. Thereby, a non-monotonic control is also avoided. For example, frequency splitting is avoided in [16] by limiting the inductance and the receiving coil. While this method ensures that frequency splitting will not occur in the strong coupling region, it will also weaken the coupling, which will eventually lead to a higher voltampere rating of the inverter and lower power transfer efficiency.

- (2)

- Restricting the operating frequency below the lower splitting frequency or above the higher splitting frequency. Since operating below the lower splitting frequency usually results in hard switching of the inverter, restricting the frequency above the higher splitting frequency is preferred [17,18]. However, as the equivalent load resistance decreases, the splitting frequencies move farther away from the resonant frequency of the resonators, inevitably leading to a significant amount of reactive power transfer between the primary and secondary sides. Therefore, even though a monotonic control with ZVS is achieved through the whole charging process and in the coupling range, the power transfer efficiency of the CC mode (low equivalent load resistance) is degraded when using this approach.

- (3)

- Restricting the operating frequency between the lower splitting frequency and the resonant frequency of the resonator [19,20]. Within this range, the output power varies monotonically with the operating frequency while maintaining ZVS for the inverter. However, the minimum achievable output power in this frequency range increases as the coupling weakens. This means that, at weaker coupling positions, CV charging under light load conditions may not be realized through frequency control alone. Additional inverter phase shift modulation or pulse width modulation is required, and this results in the loss of ZVS.

- (4)

- The CC/CV charging process transitions from the region between two splitting frequencies to the frequency-splitting-free region [21,22]. At the beginning of the CC mode, both the equivalent load resistance and the load voltage are low, and the operating frequency is set between the two splitting frequencies to achieve higher transfer efficiency. As the equivalent load resistance and load voltage increase, the system working region gradually transitions from the frequency-splitting region to the frequency-splitting-free region [21], theoretically deriving the condition to avoid frequency splitting under the constant-voltage load condition, thereby preventing non-monotonic control. However, only the case with identical primary and secondary resonant frequencies is considered. In practice, the primary resonant frequency is usually slightly lower than the secondary resonant frequency to facilitate ZVS, which is adopted in [22]. In [22], a transition from the region between two splitting frequencies to the frequency-splitting-free region is achieved in the CV mode. However, both [21,22] do not provide enough information for designing a system to ensure CC charging can be realized in the operating frequency range between two splitting frequencies and, at the same time, to ensure ZVS of the inverter.

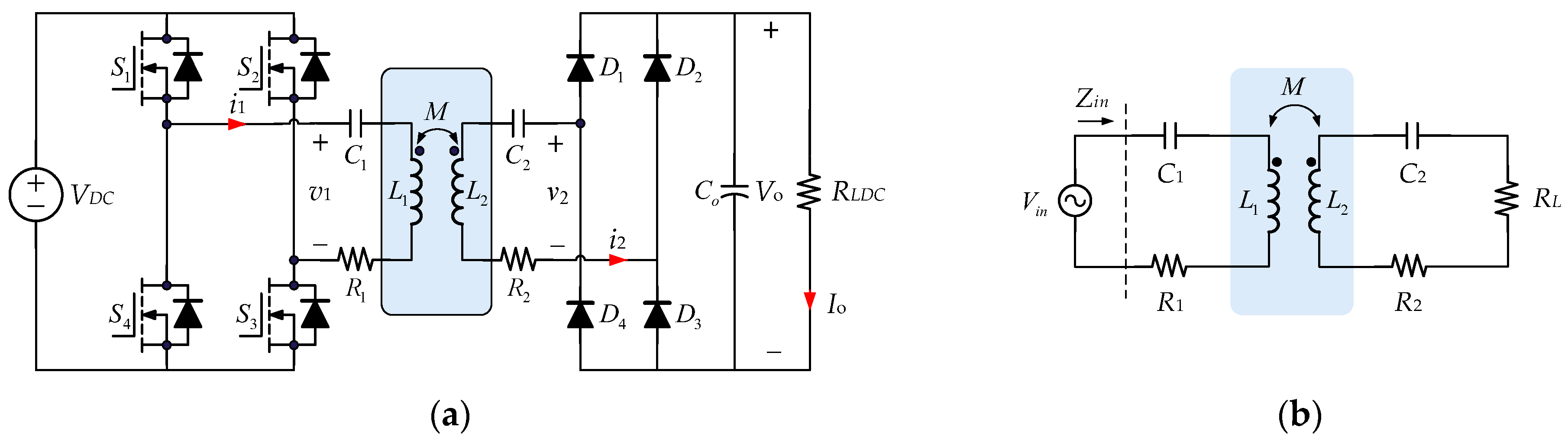

2. Zero-Phase Angle and Power Characteristics

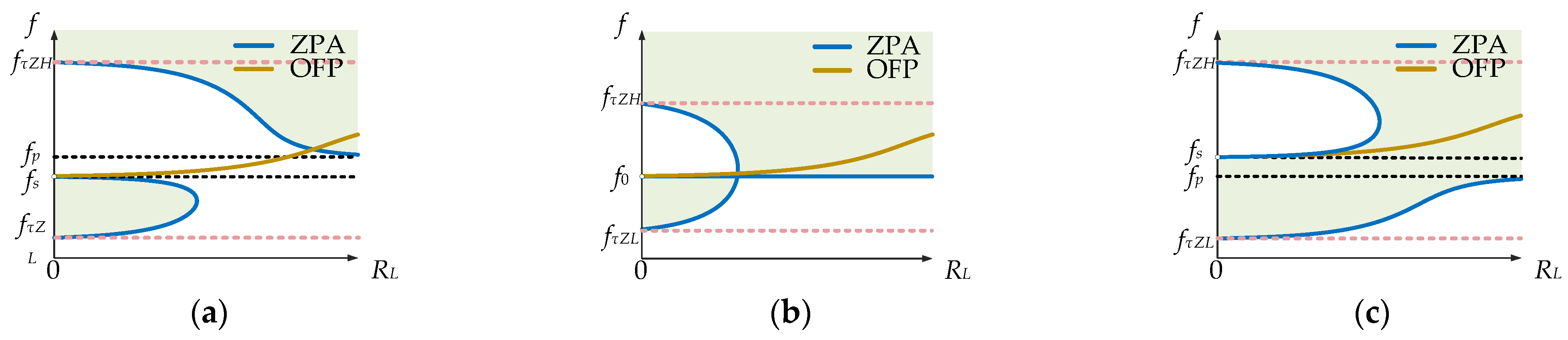

2.1. Zero-Phase Angle of Different τc

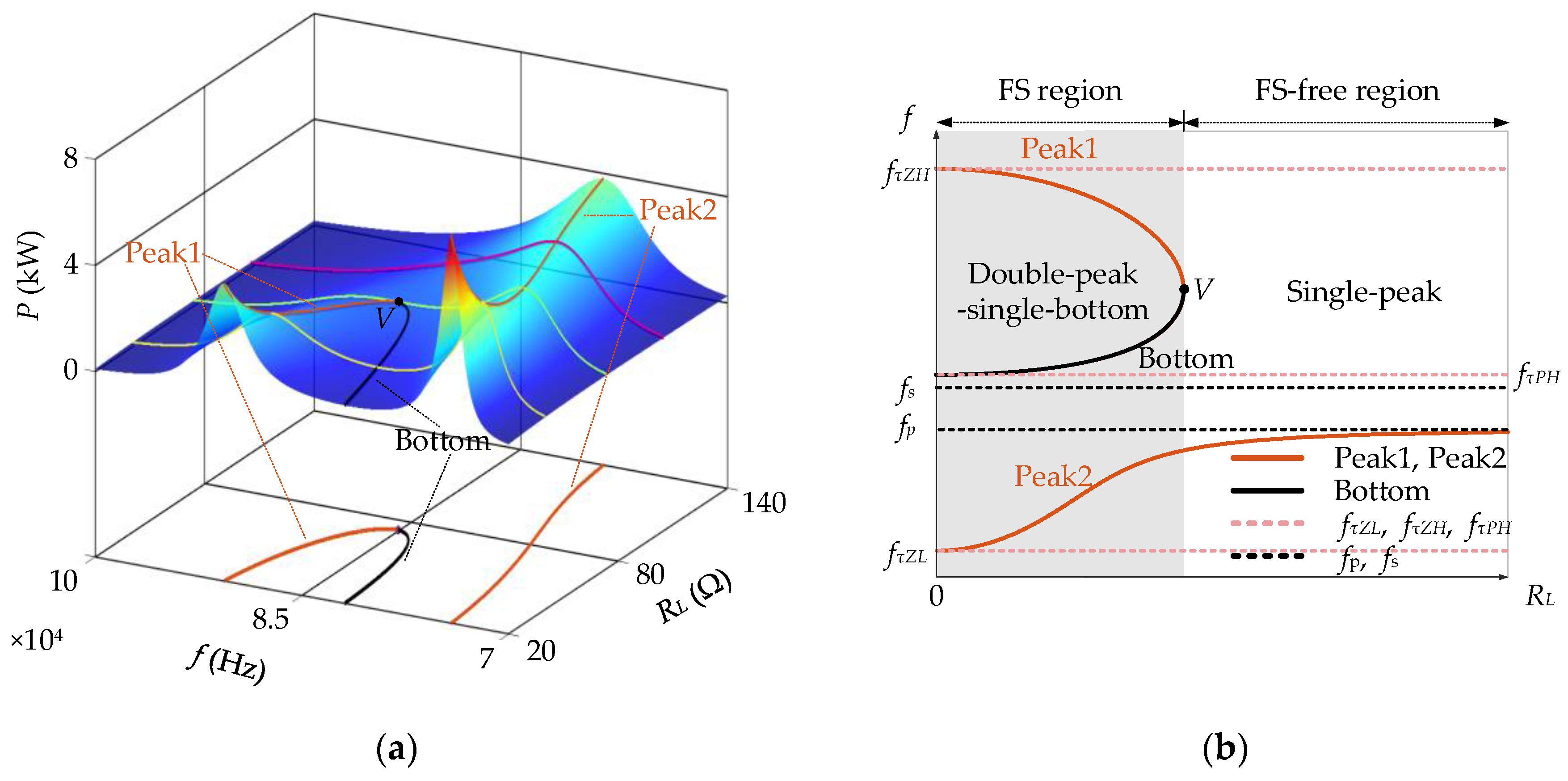

2.2. Power Variation with τc > 1

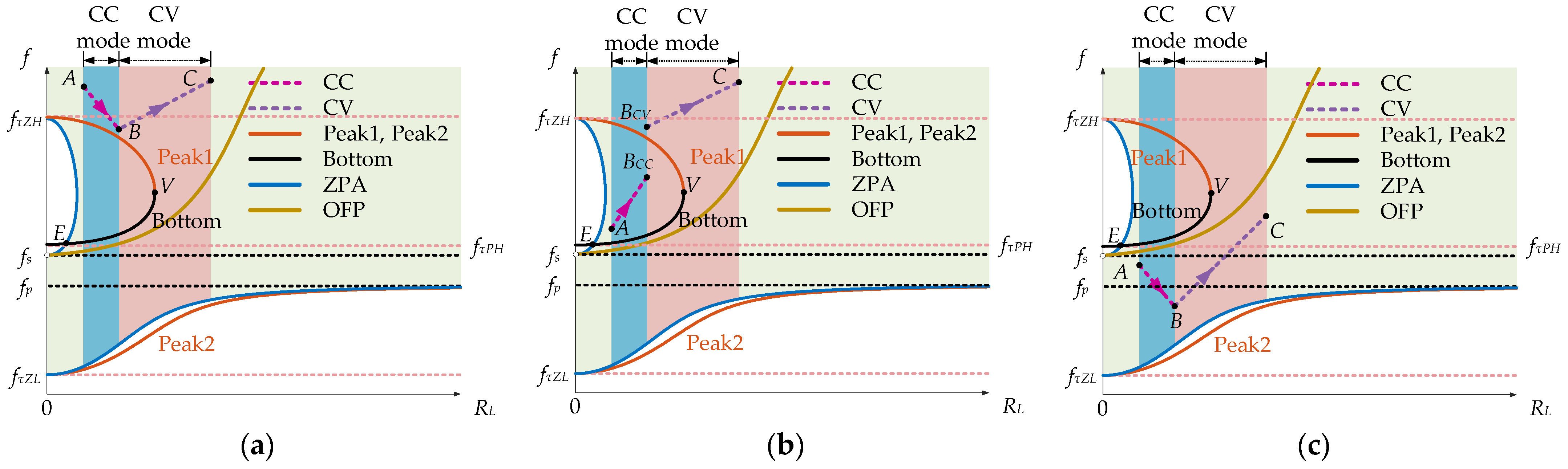

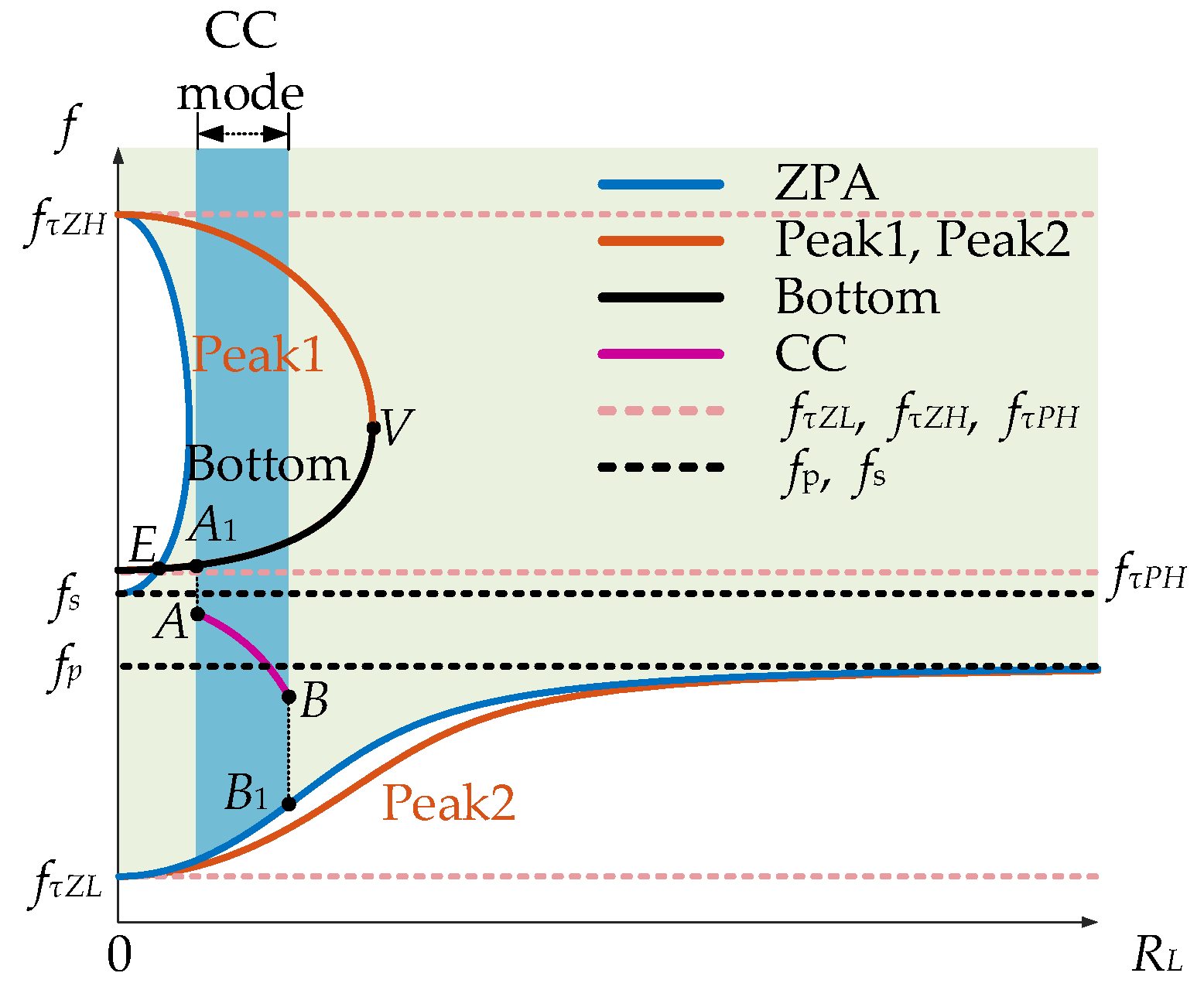

2.3. The Possible Charging Frequency Paths

2.4. CC f-RL Path of Charging Frequency Path

- (1)

- PA1 ≤ Pstart, where PA1 means the output power at point A1, which is the minimum output power that can be achieved by the system at RA; Pstart means the required output power at the start point of the CC mode.

- (2)

- PB1 ≥ Prated, where PB1 means the output power at point B1, which is the maximum output power that can be achieved by the system at RB; Prated means the required output power (i.e., the rated power) at the end of the CC mode.

- (3)

- RA ≥ RV.

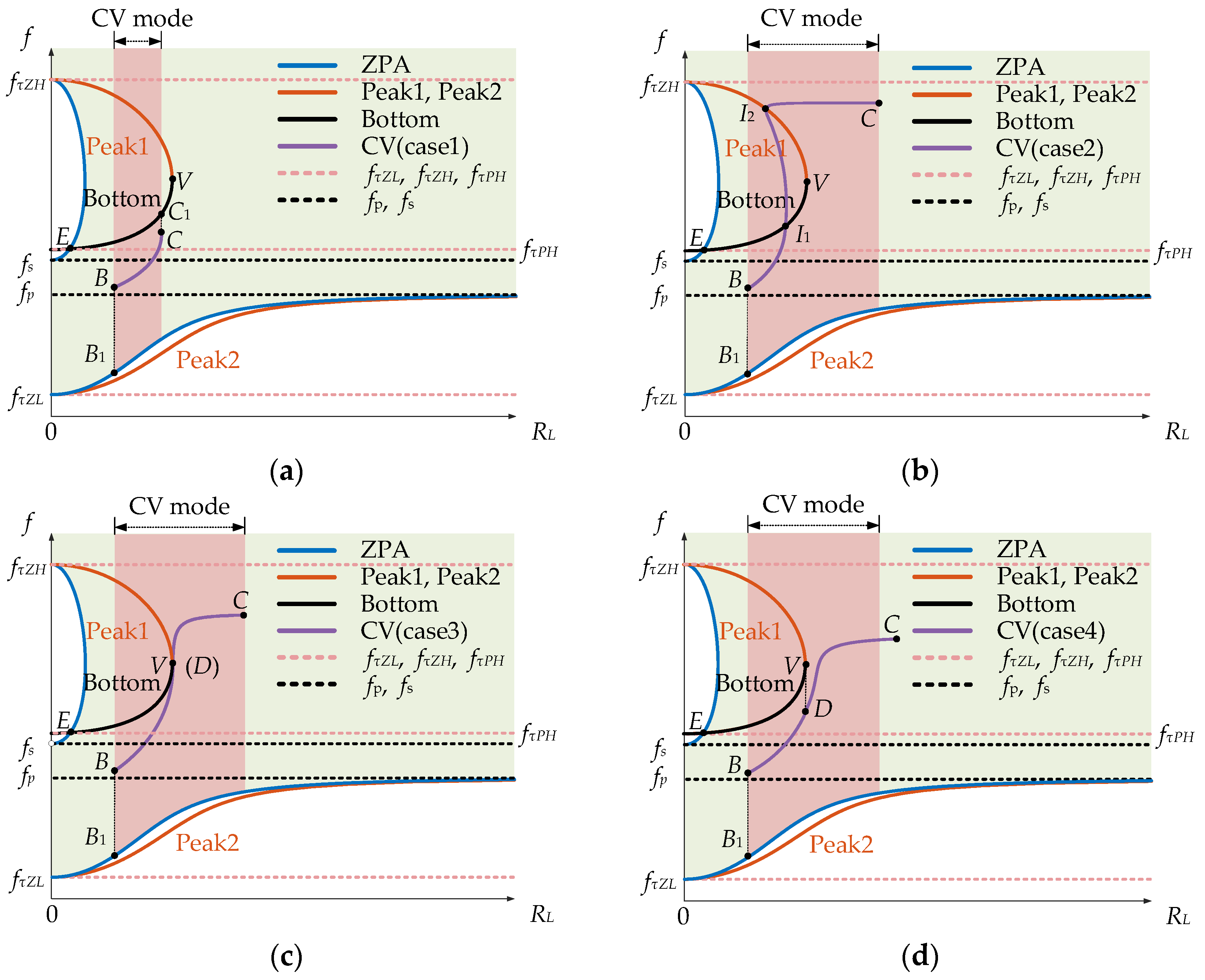

2.5. CV f-RL Path of Charging Frequency Path

- When RC < RV, the possible f-RL curve is given in Figure 6a. In this case, the CV f-RL curve lies between the Bottom curve and the Peak2 curve, and the power decreases as the frequency increases. Then, the constraints can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- fC ≤ fC1.

- (2)

- PC1 ≤ Pend, where PC1 means the output power of the system at point C1, which is the minimum achievable power of the system at RC; Pend means the required output power at the end of the CV mode (i.e., at point C).

- When RC ≥ RV, there are three possible CV f-RL curves:

- (1)

- For case2 (Figure 6b), the f-RL curve penetrates the Peak1, which implies a continuous control is not possible.

- (2)

- In summary, when RC ≥ RV, there is only one requirement to meet to realize monotonic and continuous frequency control, which is fD ≤ fV.

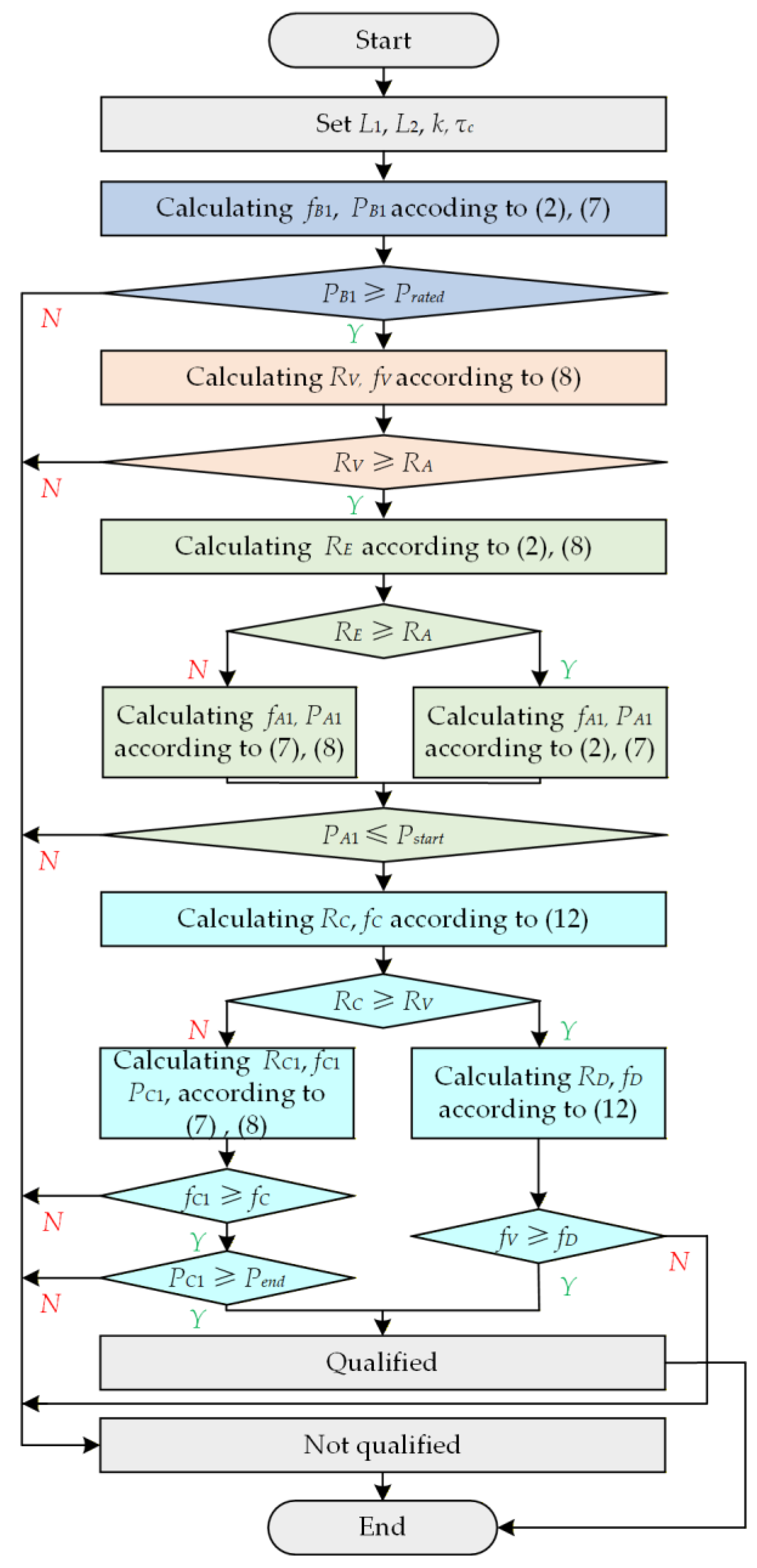

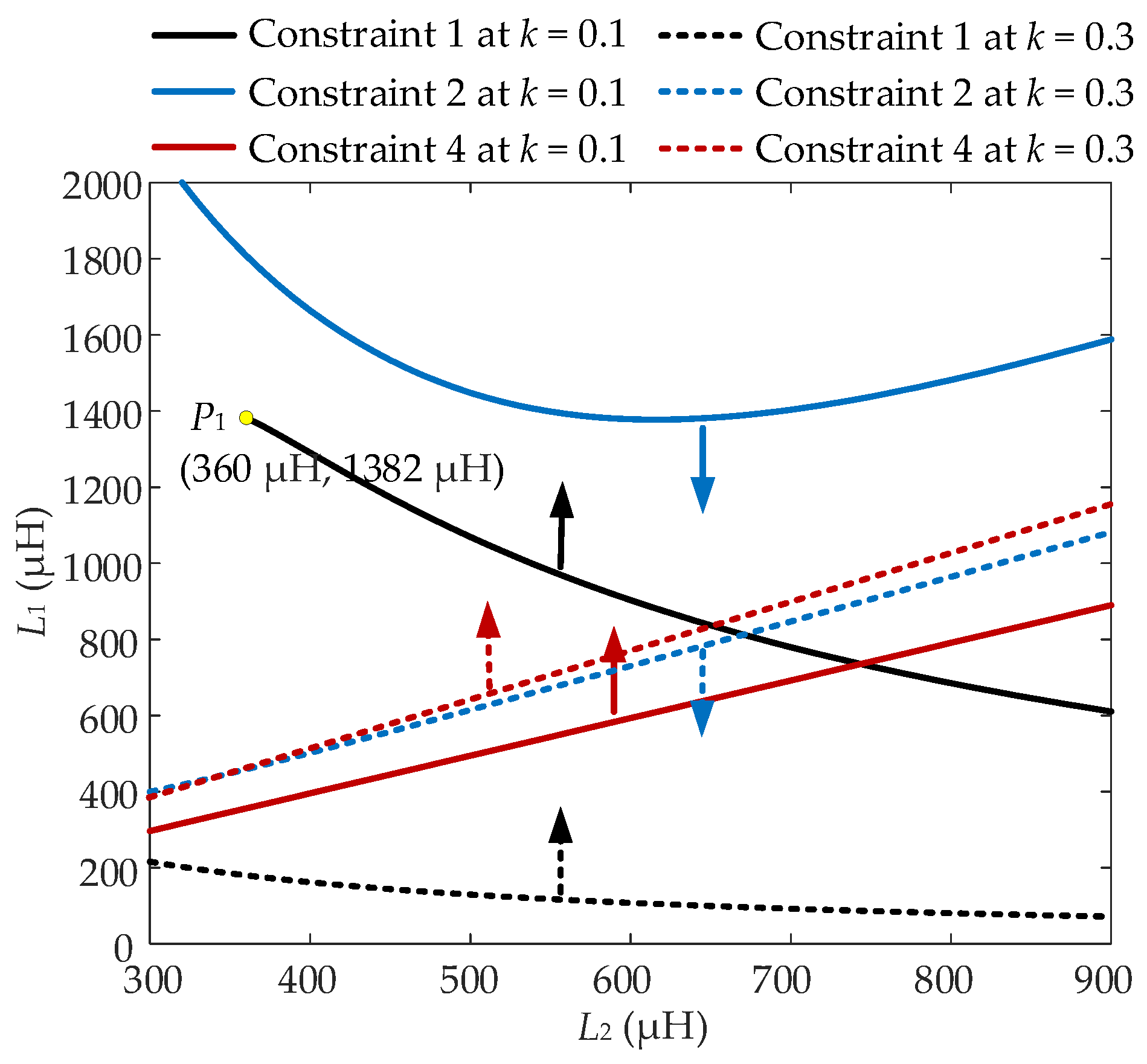

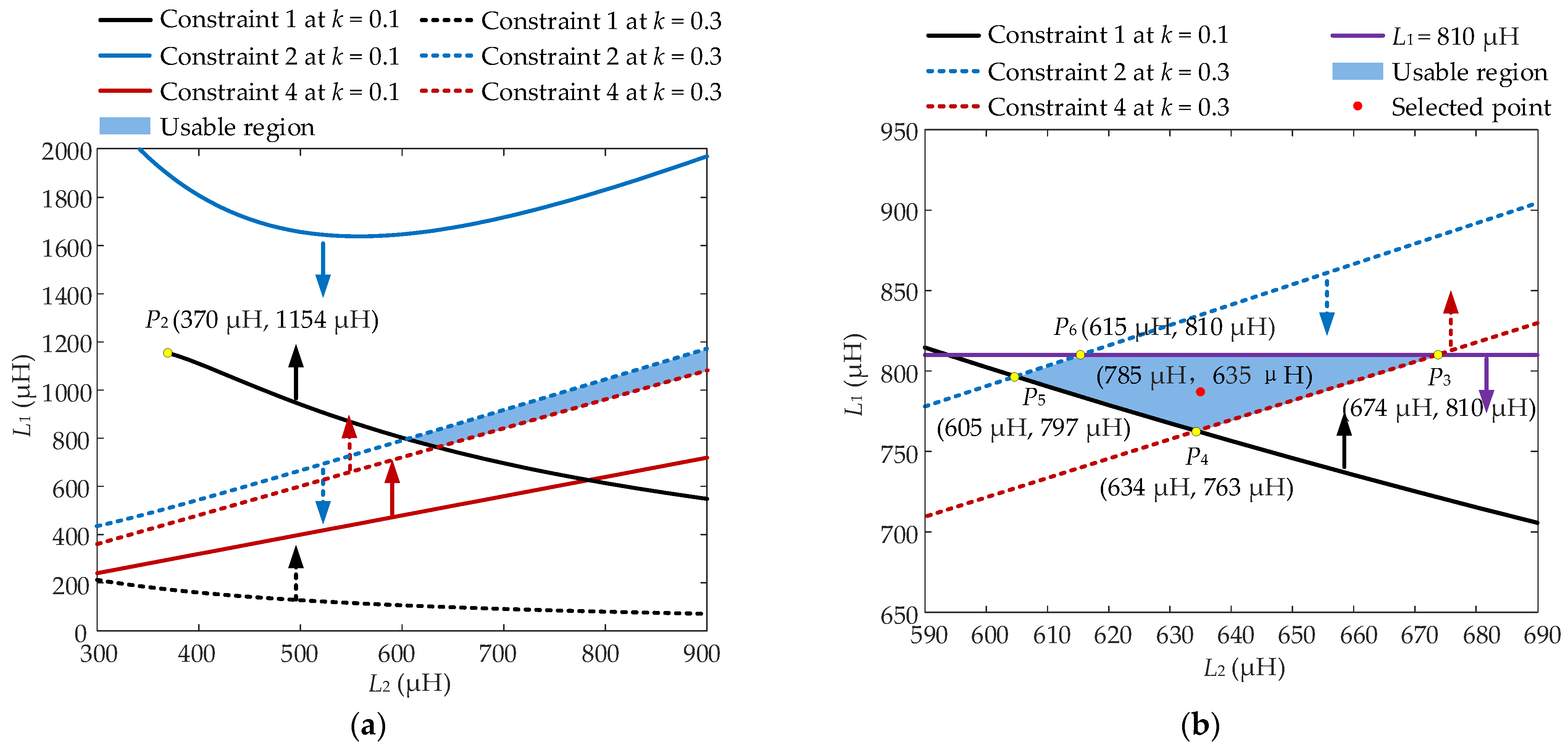

3. Parameter Design

- (1)

- PA1 ≤ Pstart.

- (2)

- PB1 ≥ Prated.

- (3)

- RA ≤ RV.

- (4)

- PC1 ≤ Pend when RC < RV or fD ≤ fV when RC ≥ RV.

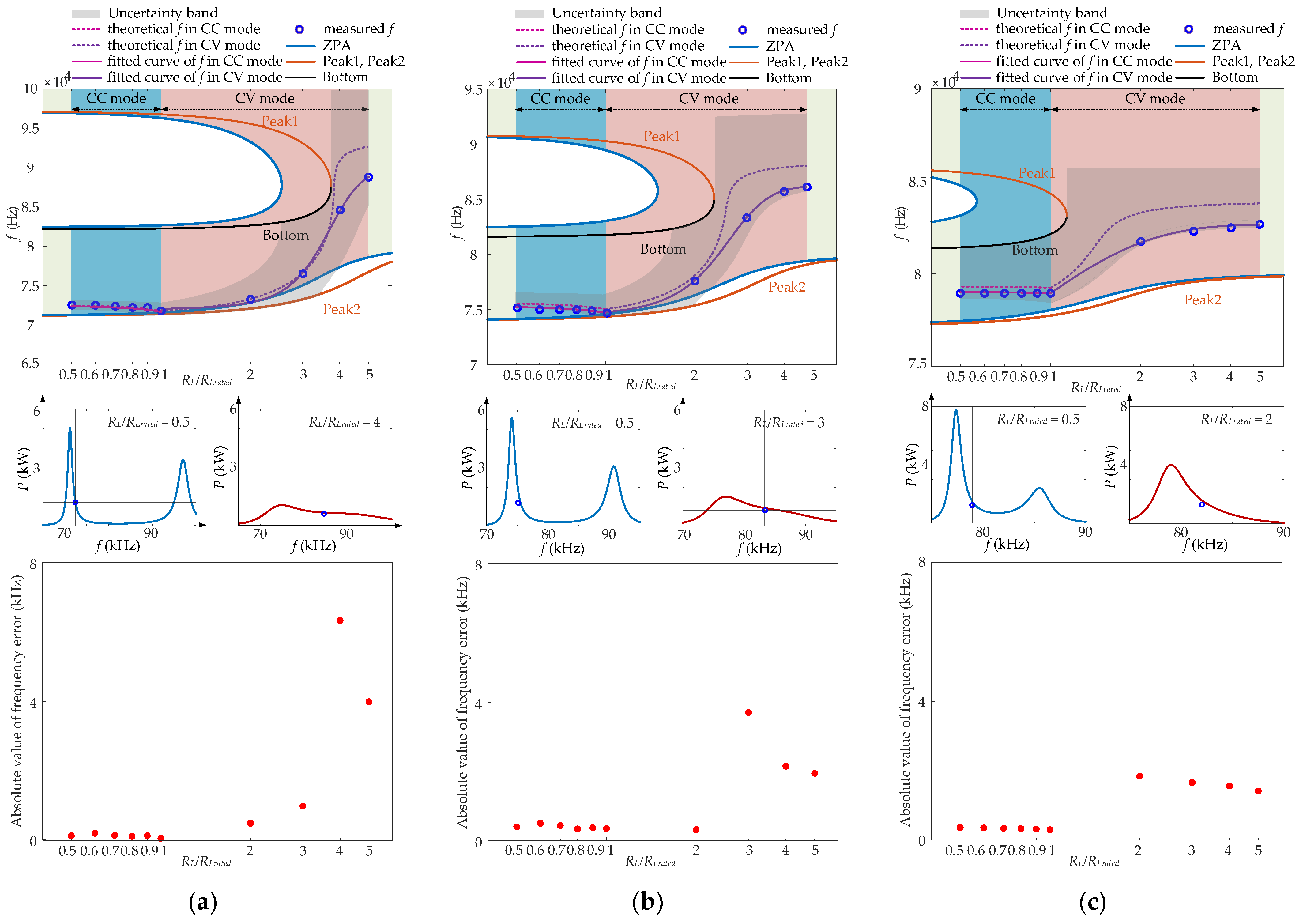

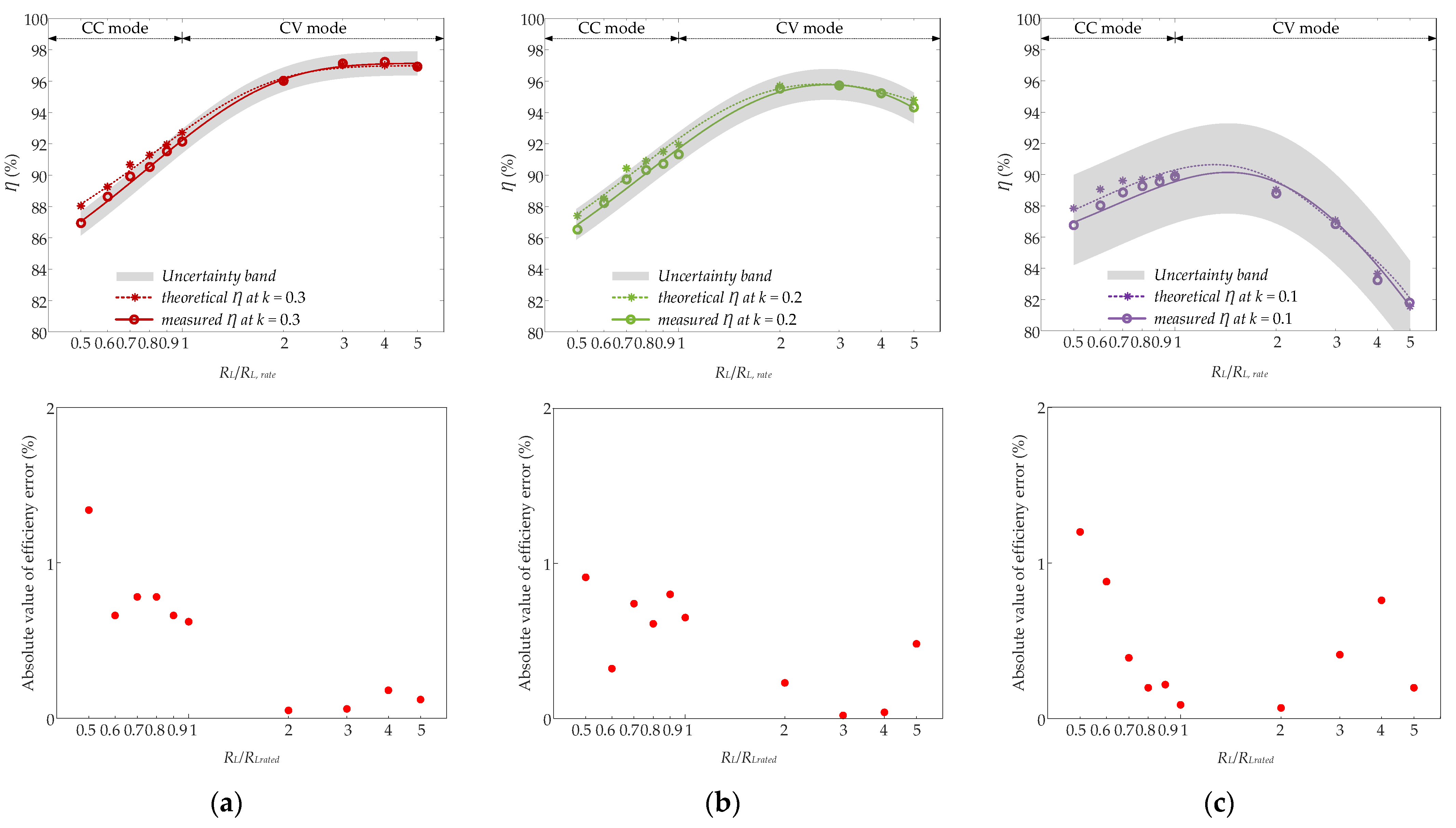

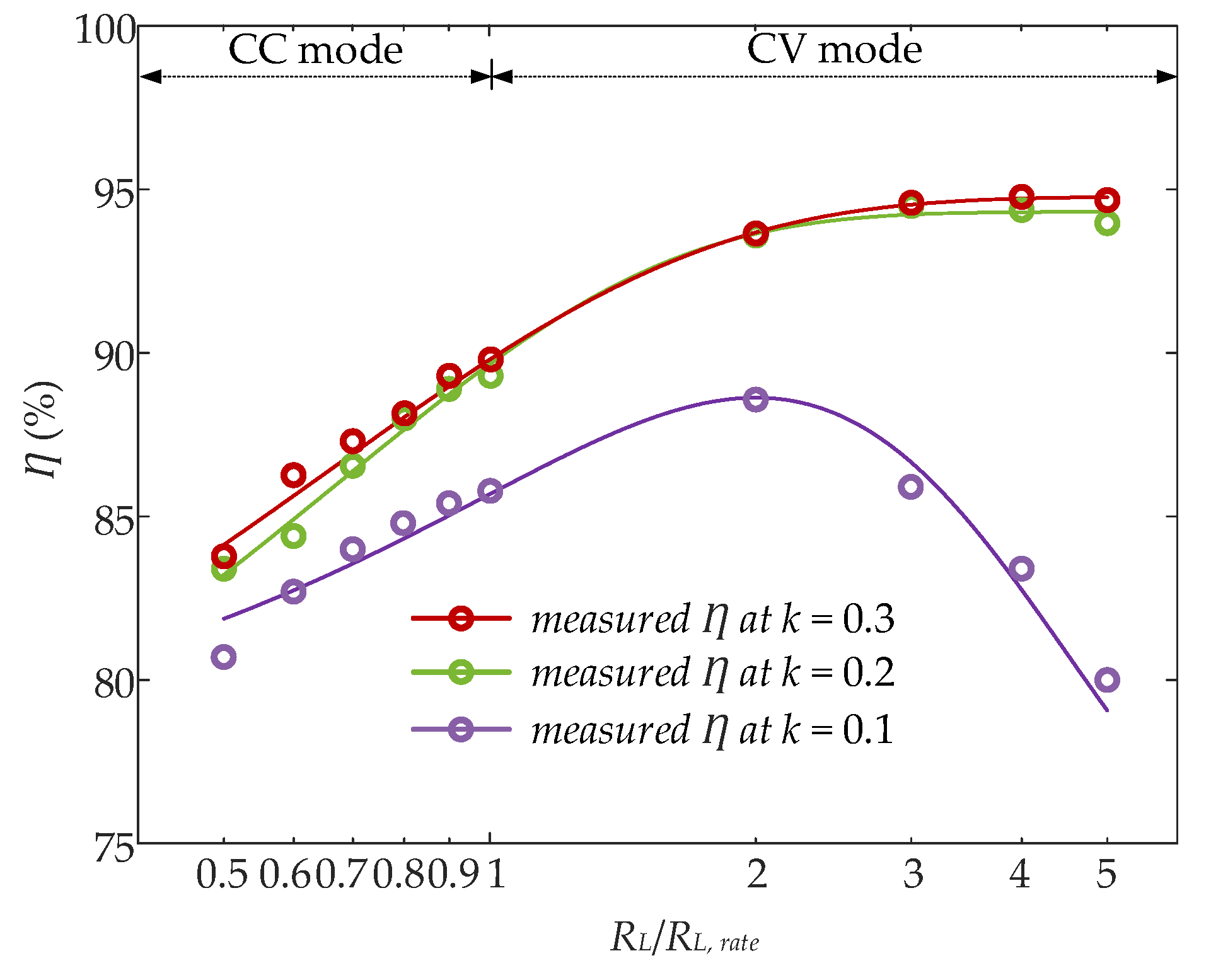

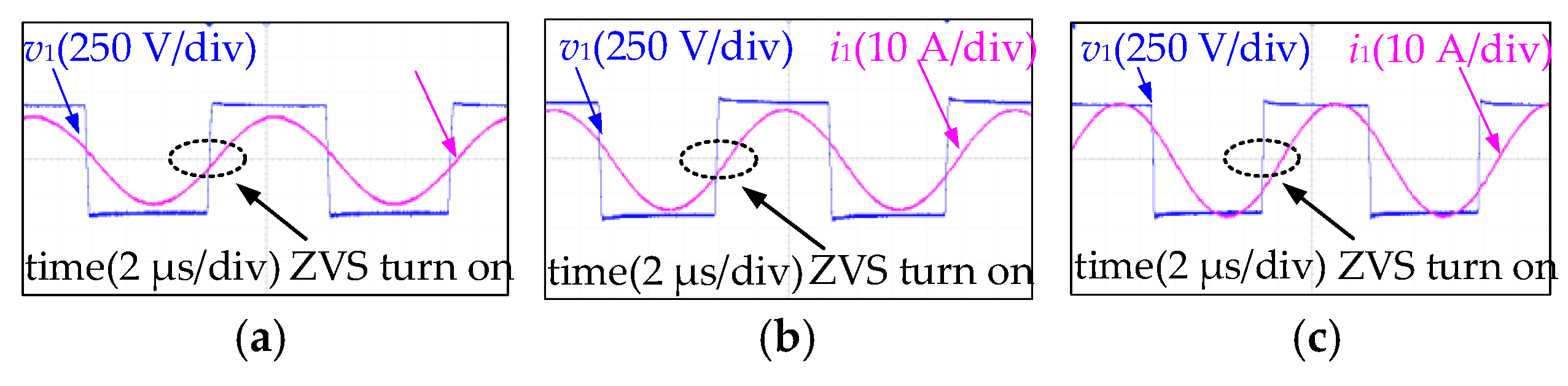

4. Experimental Verification

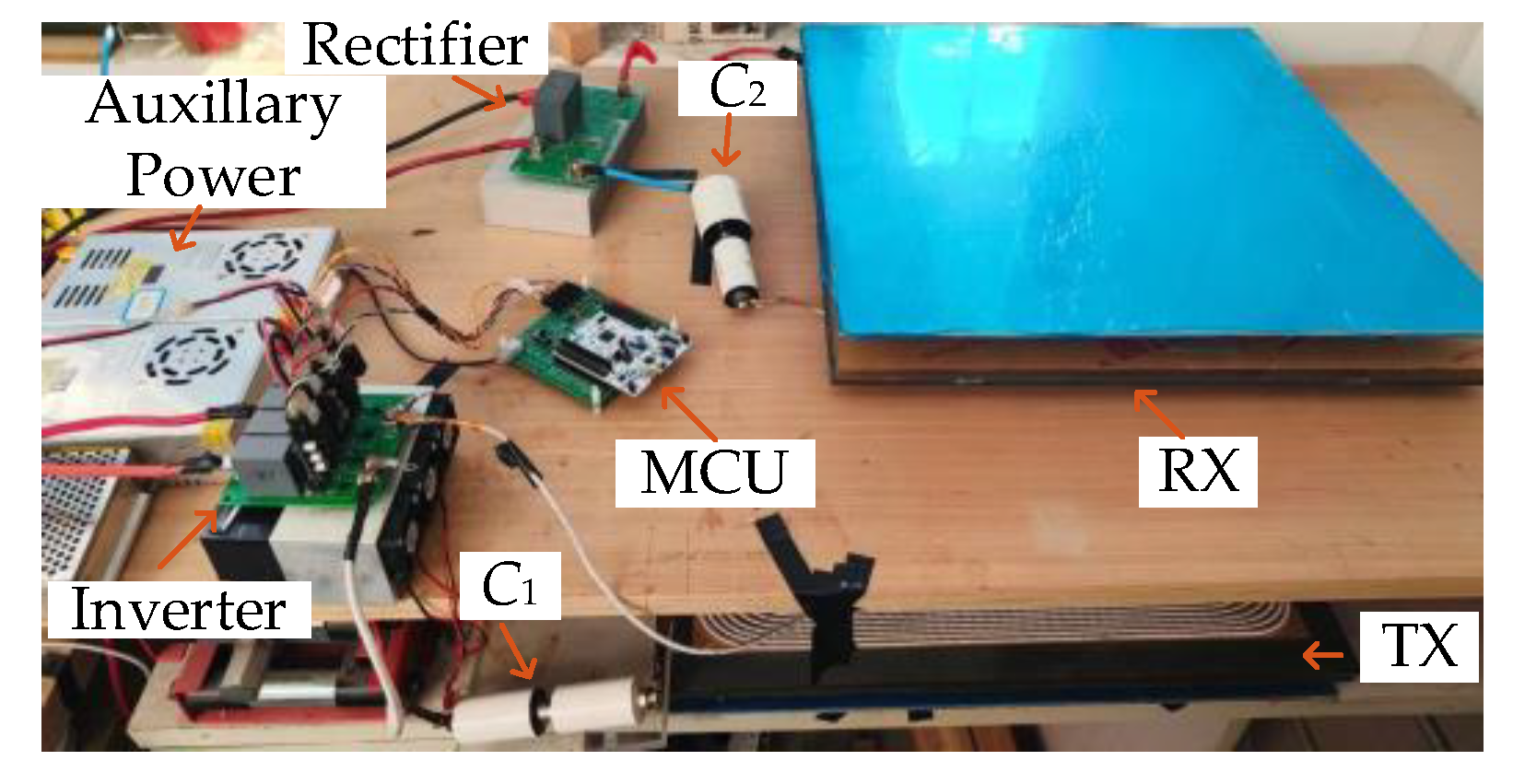

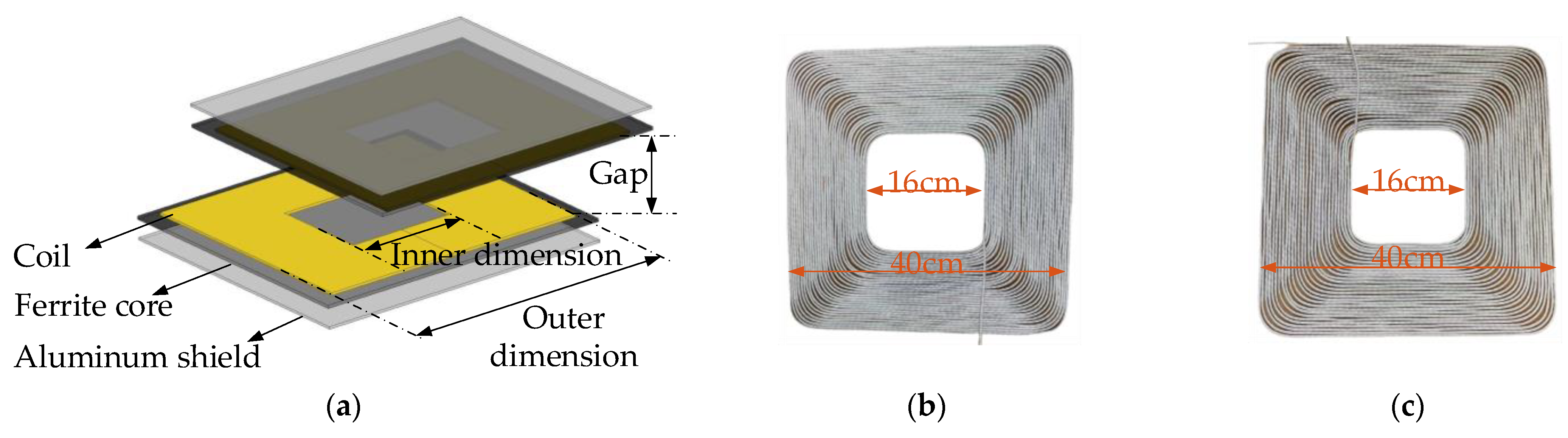

4.1. Description of the Prototype

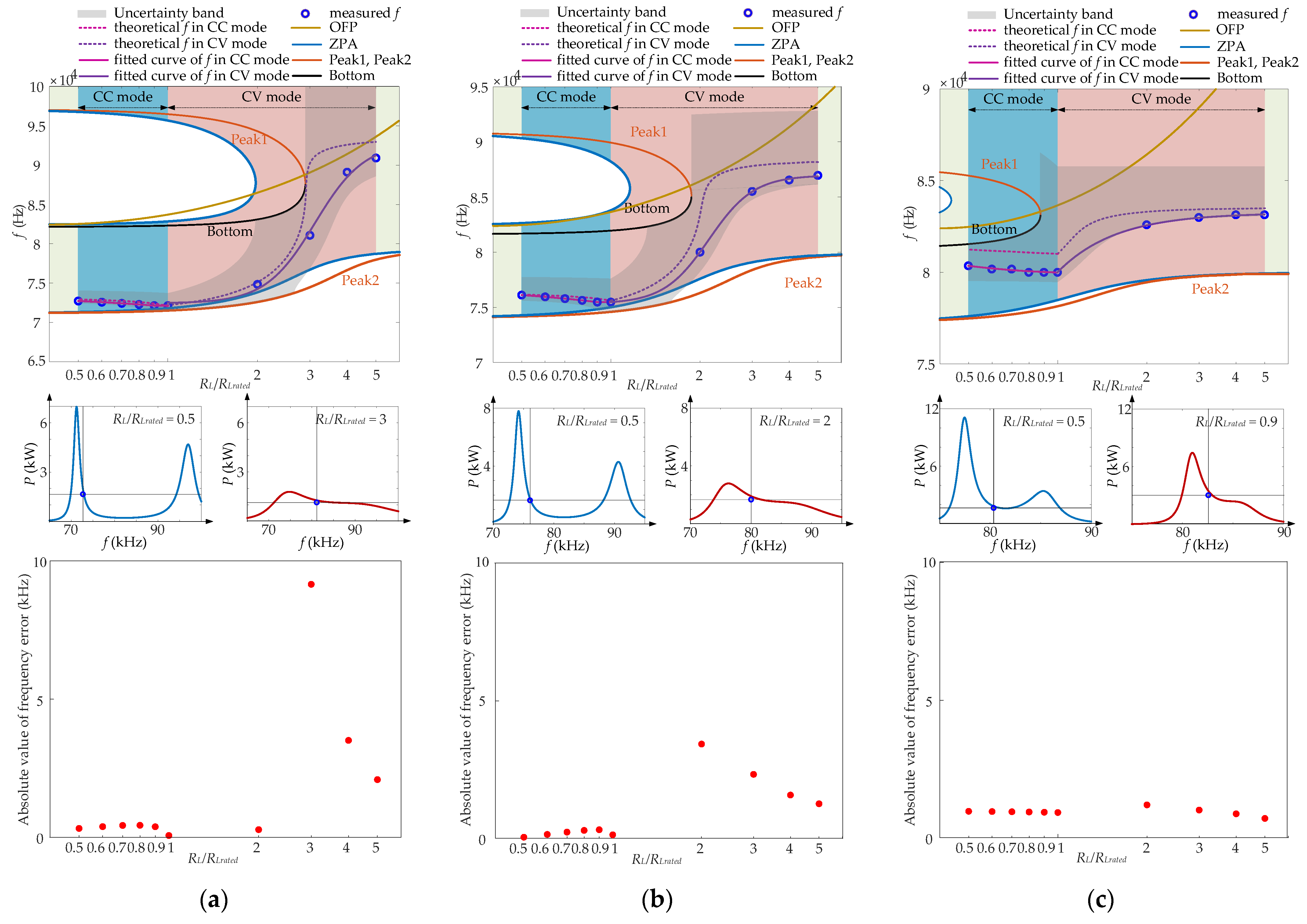

4.2. Experimental Results

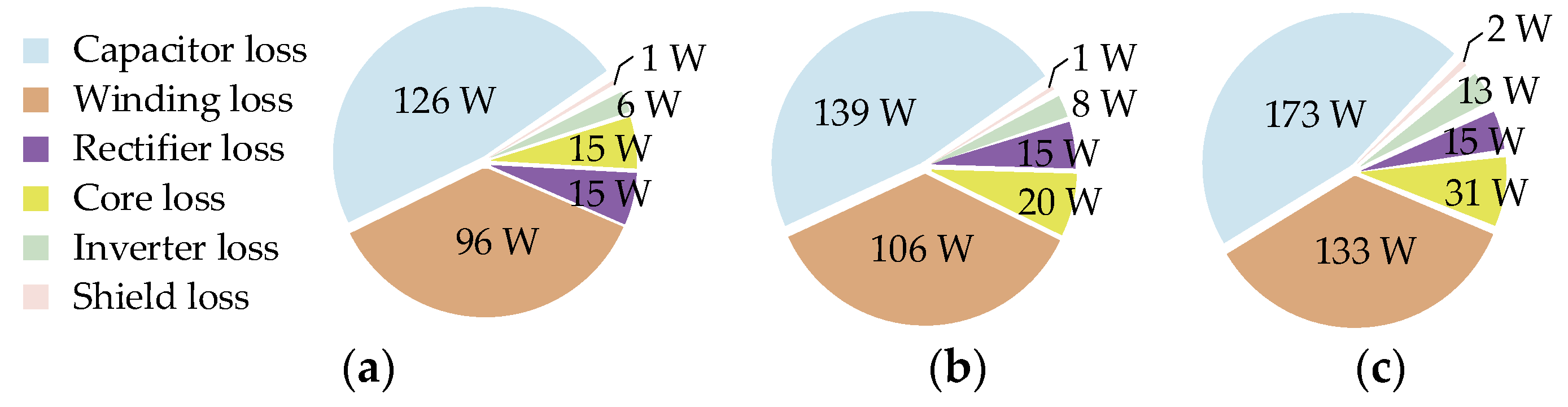

4.3. Loss Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Si, P.; Hu, A.P.; Malpas, S.; Budgett, D. A Frequency Control Method for Regulating Wireless Power to Implantable De-Vices. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2008, 2, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanamoorthi, R.; Juliet, A.V.; Chokkalingam, B. Frequency Splitting-Based Wireless Power Transfer and Simultaneous Propulsion Generation to Multiple Micro-Robots. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 5566–5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panhwar, I.H.; Mekhilef, S.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Soon, T.K.; Mokhlis, H.; Stojcevski, A. Digital Phase Synchronization and Wireless Communication in a Bidirectional SS-Compensated Wireless Power Transfer System for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 13619–13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.X.; Hui, S.Y.R. Maximum Energy Efficiency Tracking for Wireless Power Transfer Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 4025–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Fang, J.; Li, R.; Han, R.; Wang, Y. A High-Efficiency ZVS Wireless Power Transfer System for Electric Vehicle Charging with Variable Angle Phase Shift Control. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Power Electron. 2021, 9, 2356–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fang, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, K.; Tang, Y. Pulse Density Modulation for Maximum Efficiency Point Tracking of Wireless Power Transfer Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 5492–5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Chen, F.; Li, Z.; He, Z.; Mai, R. Dual-Phase-Shift Control Scheme with Current-Stress and Efficiency Optimization for Wireless Power Transfer Systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Reg. Pap. 2018, 65, 3110–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Ki, W.-H.; Lu, Y.; Yim, T.-S. Adaptive On/Off Delay-Compensated Active Rectifiers for Wireless Power Transfer Systems. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2016, 51, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshram, V.S.; Corti, F.; Solimene, L.; Musumeci, S.; Ragusa, C.S.; Reatti, A. Variable Inductor Control Strategy in LCC-S Compensated Wireless Power Transfer Application. In Proceedings of the 2023 AEIT International Annual Conference (AEIT), Rome, Italy, 5–6 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, C.-M.; Hsu, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, M.-Z.; Zheng, T.-Z. A High-Efficiency Wireless Power Transfer System with Variable Capacitor Technique for Compensating Coil Misalignment. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Wireless Power Technology Conference and Expo (WPTCE), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 4–7 June 2024; pp. 688–692. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, S.; Liao, J.; Chen, Q.; Luo, P.; Zhang, G. Variable-inductance/capacitance-based Control Strategy for on-road EV with Constant Power Wireless Charging. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE PELS Students and Young Professionals Symposium (SYPS), Nanjing, China, 5–6 August 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, R.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, G.; He, Z. Inductive Power Transfer for Massive Electric Bicycles Charging Based on Hybrid Topology Switching with a Single Inverter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 32, 5897–5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample, A.P.; Meyer, D.T.; Smith, J.R. Analysis, Experimental Results, and Range Adaptation of Magnetically Coupled Resonators for Wireless Power Transfer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.-Q.; Chu, J.-X.; Gu, W.; Shen, A.-D. Exact Analysis of Frequency Splitting Phenomena of Contactless Power Transfer Systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Reg. Pap. 2013, 60, 1670–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Ma, H.; Lai, J.; Zhang, P. High-Efficiency Contactless Power Transfer System for Electric Vehicle Battery Charging Application. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Power Electron. 2015, 3, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onai, M.; Ojo, O. Performance Analysis and Design of Frequency Controlled Series-Series Compensated Inductive Power Transfer System for Electric Vehicle Battery Charging. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Su, H. Analysis and Design of Wireless Charging Systems Without Extra Components for Load-Independent Constant Current and Voltage Battery Charging. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Power Electron. 2024, 12, 3200–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, K.; Williamson, S.S. Design Guidelines to Avoid Bifurcation in a Series–Series Compensated Inductive Power Transfer System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 3973–3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulfovich, A.; Kuperman, A. Design Space of Sub-Resonant Frequency-Controlled Series–Series-Compensated Inductive Wireless Power Transfer Links Operating With Constant Output Current Under Frequency Constraints. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Power Electron. 2022, 10, 5414–5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulfovich, A.; Kuperman, A. Increasing tolerable coupling coefficients range of series-series compensated inductive wireless power transfer systems operating in restricted sub-resonant frequency region with constant current output. Energy 2024, 292, 130572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jiang, C.Q.; Ma, T.; Guidi, G.; Zhang, X.; Suul, J.A. Comprehensive Analysis of Bifurcation and Frequency Splitting Phenomena in Inductive Battery Charging Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 15329–15341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, Q.; Hu, J.; Wang, L.; Tang, C.S. Minimizing Current in Inductive Power Transfer Systems with an Asymmetrical Factor for Misalignment Tolerance and Wide Load Range. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 9886–9896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, G.; Suul, J.A. Minimizing Converter Requirements of Inductive Power Transfer Systems With Constant Voltage Load and Variable Coupling Conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 6835–6844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wong, S.; Tse, C.K. Design methodology of a series-series inductive power transfer system for electric vehicle battery charger application. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 14–18 September 2014; pp. 1778–1782. [Google Scholar]

- Steigerwald, R.L. A Comparison of Half-Bridge Resonant Converter Topologies. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 1988, 3, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhong, W. Small-Signal Modeling and Decoupling Control Method of Modular Wireless Power Transfer Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 7863–7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Coupling Range | Rated Power | Efficiency | Charging Range | The fs-fp Relationship | The Key Condition for Monotonic Frequency | System Parameters Design Guideline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14] | 0.194 | 1 kW | - | CC and CV | fs = fp | yes | no |

| [15] | 0.3–0.48 | 288 W | - | CC | fs = fp | no | yes |

| [19] | 0.15–0.25 | 250 W | 70–90.51% | CC and CV | fs > fp | no | yes |

| [20] | 0.23–0.41 | 288 W | 92.1–93.2% | CC | fs = fp | no | yes |

| This work | 0.1–0.3 | 3.3 kW | 81.8–97.2% | CC and CV | fs > fp | yes | yes |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Rated power | Prated | 3.3 kW |

| Initial power | Pstart | 1.7 kW |

| Primary resonant frequency | fp | 80 kHz |

| Input voltage | VDC | 400 V |

| Output voltage (i.e., charging voltage) | Vo | 200–400 V |

| Output current (i.e., charging current) | Io | 1.7–8.3 A |

| Load range | RLDC | 24–242 Ω |

| Coupling coefficient | kmin–kmax | 0.1–0.3 |

| fp | τc | k | L2C-V | L2A-V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80 kHz | 1.01 | 0.1 | 3310 μH | 340 μH |

| 0.3 | 1070 μH | 110 μH | ||

| 1.02 | 0.1 | 3530 μH | 360 μH | |

| 0.3 | 1090 μH | 110 μH | ||

| 1.03 | 0.1 | 3630 μH | 370 μH | |

| 0.3 | 1100 μH | 110 μH |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Primary coil inductance | L1 | 785 μH |

| Secondary coil inductance | L2 | 635 μH |

| Primary coil turns | N1 | 32 |

| Secondary coil turns | N2 | 29 |

| Primary resonant capacitance | C1 | 5.04 nF |

| Secondary resonant capacitance | C2 | 5.875 nF |

| Asymmetrical factor | τc | 1.03 |

| Parameter | Transmitting Side | Receiving Side |

|---|---|---|

| Litz wire | ϕ1 mm × 800 | ϕ1 mm × 800 |

| Outer dimension (mm) | 450 × 450 | 450 × 450 |

| Inner dimension (mm) | 180 × 180 | 180 × 180 |

| Ferrite dimension (mm) | 500 × 500 × 5 | 500 × 500 × 5 |

| Aluminum dimension (mm) | 500 × 500 × 4 | 500 × 500 × 4 |

| dcf (mm) | 2 | 2 |

| daf (mm) | 30.16 | 30.16 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Rated power | Prated | 2.4 kW |

| Initial power | Pstart | 1.2 kW |

| Primary resonant frequency | fp | 80 kHz |

| Input voltage | VDC | 300 V |

| Output voltage (i.e., charging voltage) | Vo | 150–300 V |

| Output current (i.e., charging current) | Io | 1.6–8 A |

| Load range | RLDC | 19–188 Ω |

| Coupling coefficient | kmin–kmax | 0.1–0.3 |

| Parameter | RL/RL,rated | kmax | kmid | kmin | RL/RL,rated | kmax | kmid | kmin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | 0.5 | 54° | 53° | 37° | 0.6 | 47° | 45° | 35° |

| Measured | 49° | 50° | 43° | 40° | 42° | 42° | ||

| Theoretical | 0.7 | 39° | 38° | 33° | 0.8 | 30° | 30° | 32° |

| Measured | 32° | 36° | 40° | 23° | 29 | 38° | ||

| Theoretical | 0.9 | 20° | 21° | 30° | 1 | 7° | 14° | 30° |

| Measured | 15° | 21° | 37° | 8° | 15° | 34° | ||

| Theoretical | 2 | 7° | 20° | 61° | 3 | 24° | 52° | 70° |

| Measured | 8° | 21° | 60° | 17° | 47° | 68° | ||

| Theoretical | 4 | 45° | 61° | 75° | 5 | 54° | 67° | 78° |

| Measured | 38° | 56° | 70° | 48° | 63° | 72° |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| The equivalent series resistance of primary coil | RL1 | 0.6 Ω |

| The equivalent series resistance of secondary coil | RL2 | 0.5 Ω |

| The equivalent series resistance of primary capacitor | RC1 | 0.76 Ω |

| The equivalent series resistance of secondary capacitor | RC2 | 0.69 Ω |

| MOSFET conduction resistance | RDS(ON) | 27.6 mΩ |

| Reverse recovery charge | Qrr | 897 nC |

| Anti-parallel diode voltage at kmax | VDM | 3.02 V |

| Anti-parallel diode voltage at kmid | VDM | 3.19 V |

| Anti-parallel diode voltage at kmin | VDM | 3.60 V |

| The dead time | tdead | 450 ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Lin, M.; Yue, K.; Zhong, W. A Monotonic and Continuous Frequency Control Method Covering Constant-Current and Constant-Voltage Charging Processes for Series-Series WPT Systems. Energies 2025, 18, 6489. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246489

Liu Y, Lin M, Yue K, Zhong W. A Monotonic and Continuous Frequency Control Method Covering Constant-Current and Constant-Voltage Charging Processes for Series-Series WPT Systems. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6489. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246489

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yinchao, Minshen Lin, Kang Yue, and Wenxing Zhong. 2025. "A Monotonic and Continuous Frequency Control Method Covering Constant-Current and Constant-Voltage Charging Processes for Series-Series WPT Systems" Energies 18, no. 24: 6489. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246489

APA StyleLiu, Y., Lin, M., Yue, K., & Zhong, W. (2025). A Monotonic and Continuous Frequency Control Method Covering Constant-Current and Constant-Voltage Charging Processes for Series-Series WPT Systems. Energies, 18(24), 6489. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246489