The Integration of Passive and Active Methods in a Hybrid BMS for a Suspended Mining Vehicle

Abstract

1. Introduction

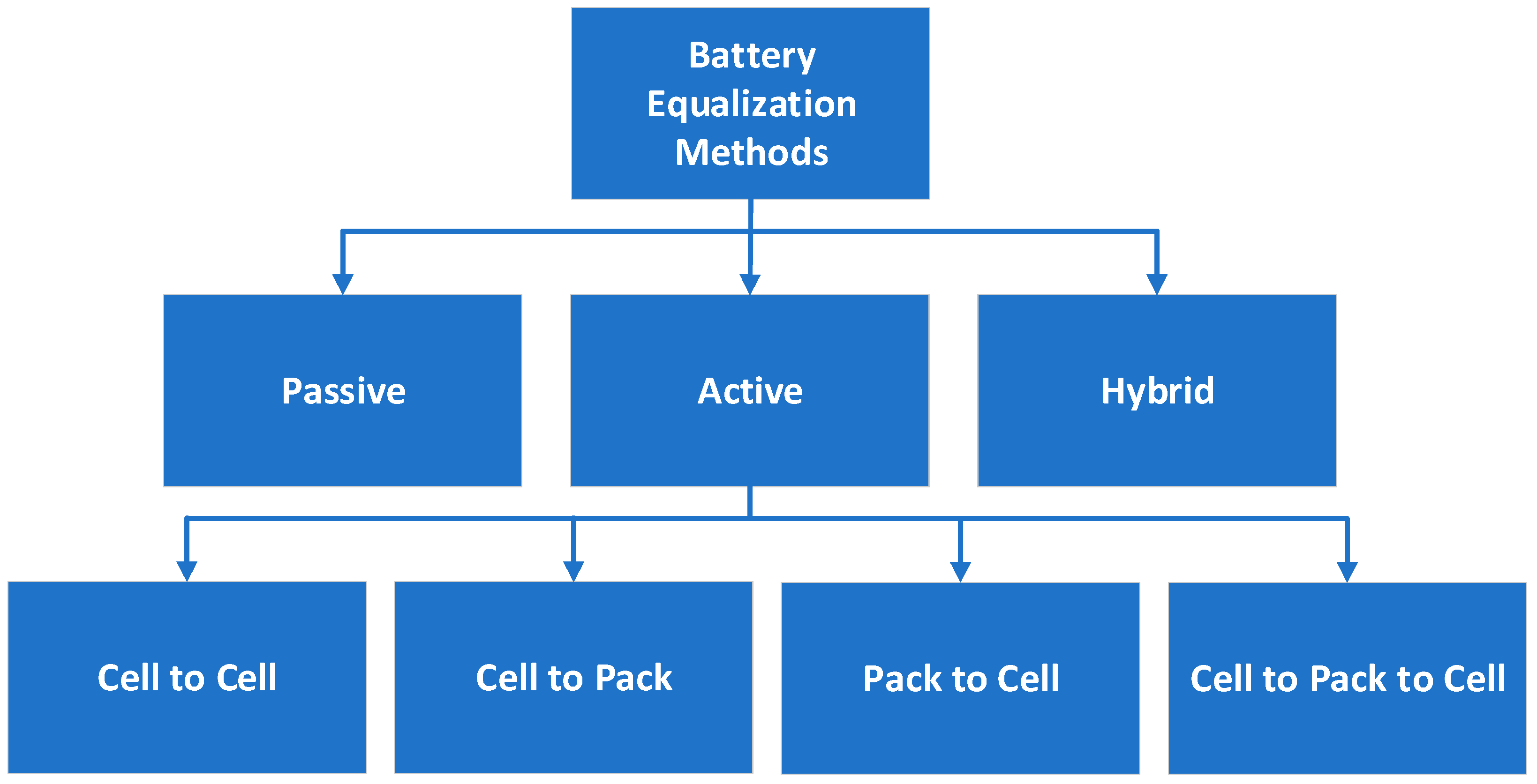

2. Cell Balancing Methods

- Passive—consisting of dissipating excess energy into heat using the appropriately selected resistors, impedances, and/or transistors;

- Active—consisting of an external system balancing the energy stored in cells by transferring energy between the cells (less commonly used);

- Hybrid—combining the features of active and passive systems, involving the active transfer of energy between cells and passive protection against overcharging during the charging process.

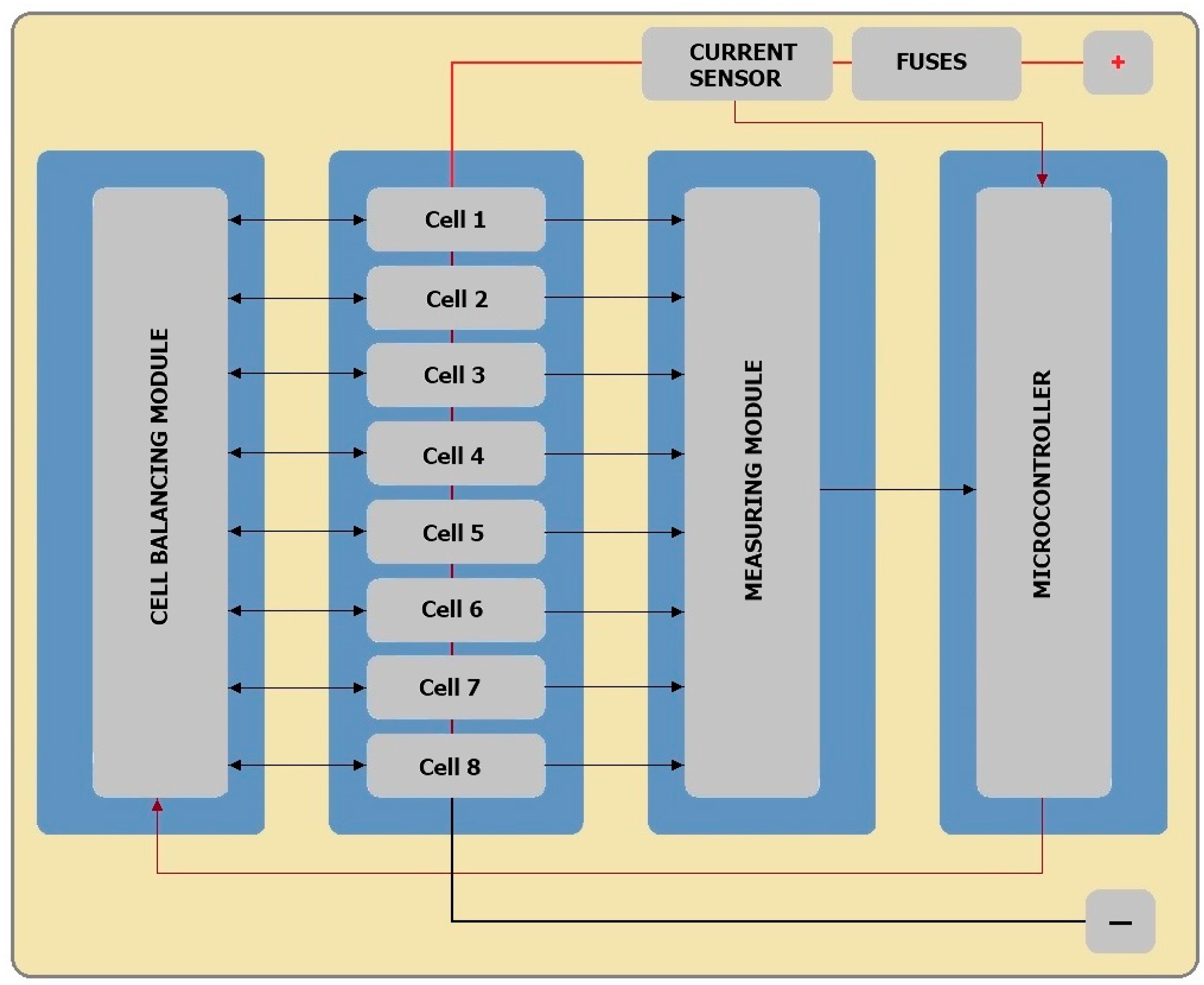

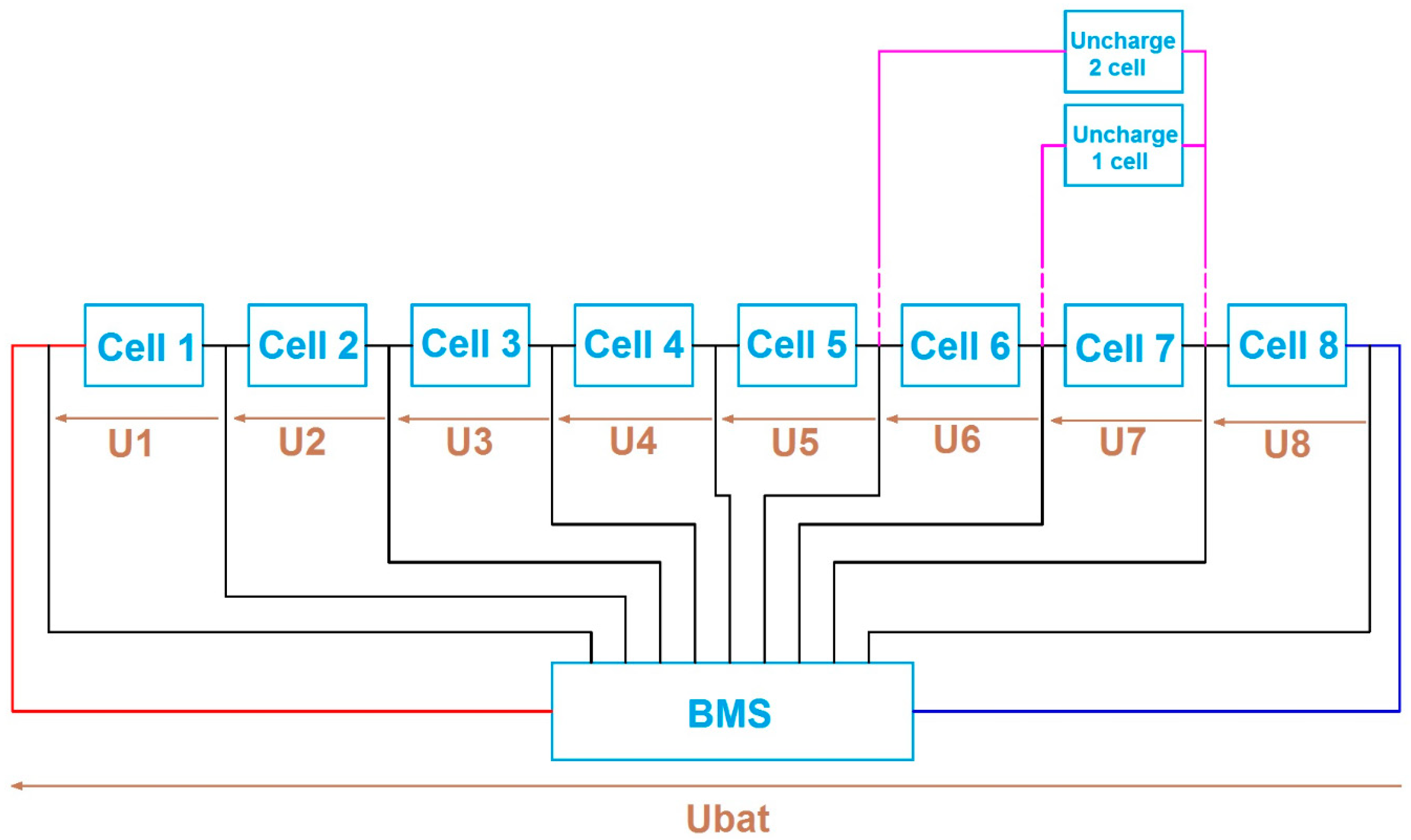

3. Hybrid BMS

- Measurement and control module—responsible for monitoring the voltage and temperature of the cells and controlling the entire system;

- Passive balancing system module—based on resistors connected in parallel to each cell, which dissipates the excess energy as heat;

- Active balancing system module—enables the transfer of the energy to the lowest-capacity cells, increasing the efficiency of the battery pack.

3.1. Measuring Module

3.2. Active Balancing Module

3.3. Passive Balancing Module

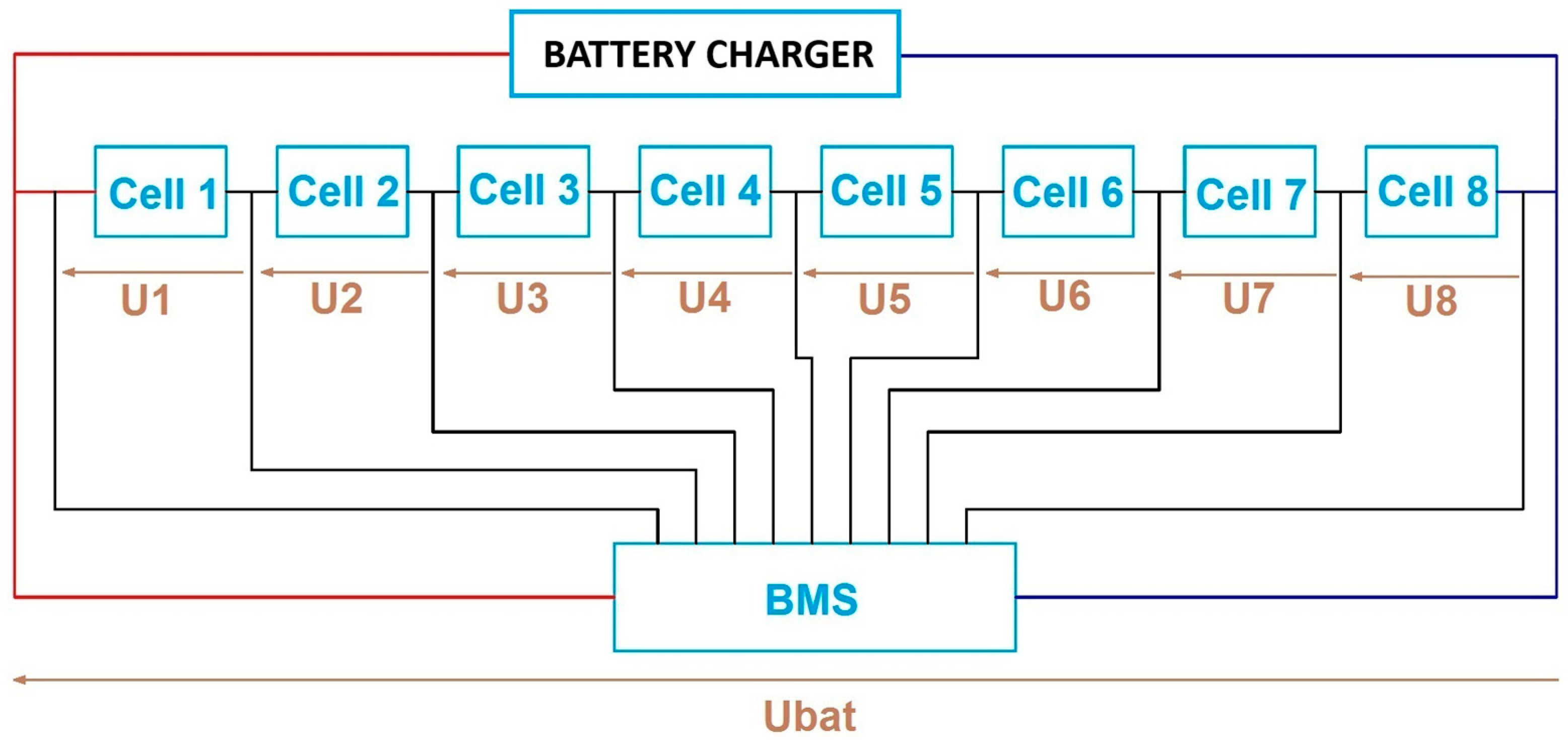

3.4. Hybrid BMS Operation

- In the discharge mode, e.g., during the operation of a machine powered by a lithium battery, when the voltage drops below a specified threshold (e.g., U/Un = 0.94; 3.0 V), the active balancing system is activated. The passive balancing system then remains inactive. The process of equalizing the voltages continues until they are unified or until one of the cells reaches the minimum permissible voltage.

- In the charging mode, both balancing systems are activated. The active system transfers energy to the lowest-capacity cell, while the passive system dissipates excess energy in the cells of the highest capacity. However, if the voltage of any cell approaches the maximum allowed by the manufacturer and the passive energy dissipation capabilities are exceeded, the system disconnects the charger and switches to voltage monitoring mode. When, in turn, the voltages drop down below the fixed threshold, the charger is switched on again, together with the appropriate balancing modules. If the voltages for all cells are close to the maximum, the system switches off the active balancing system and leaves only passive ones in operation.

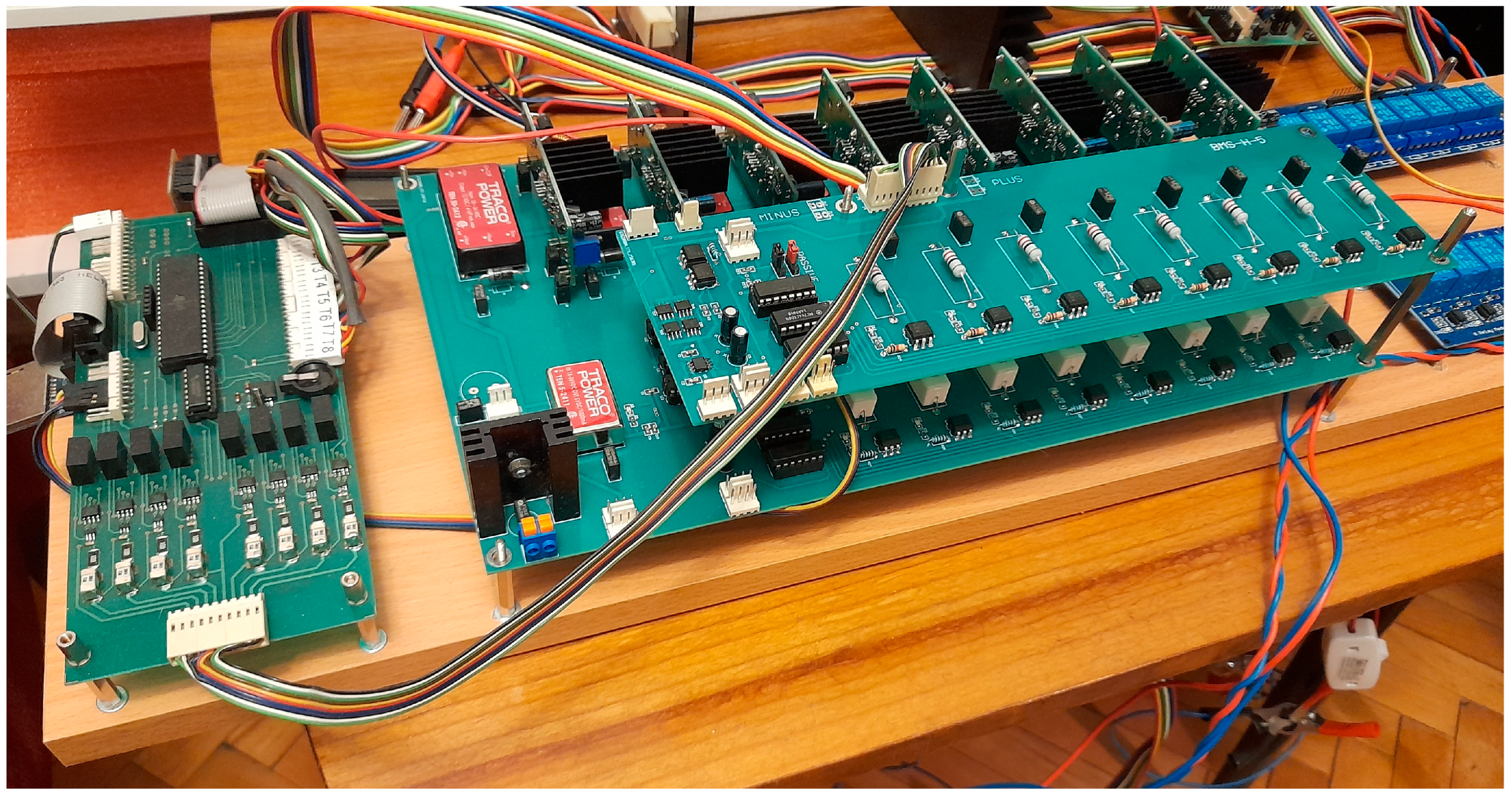

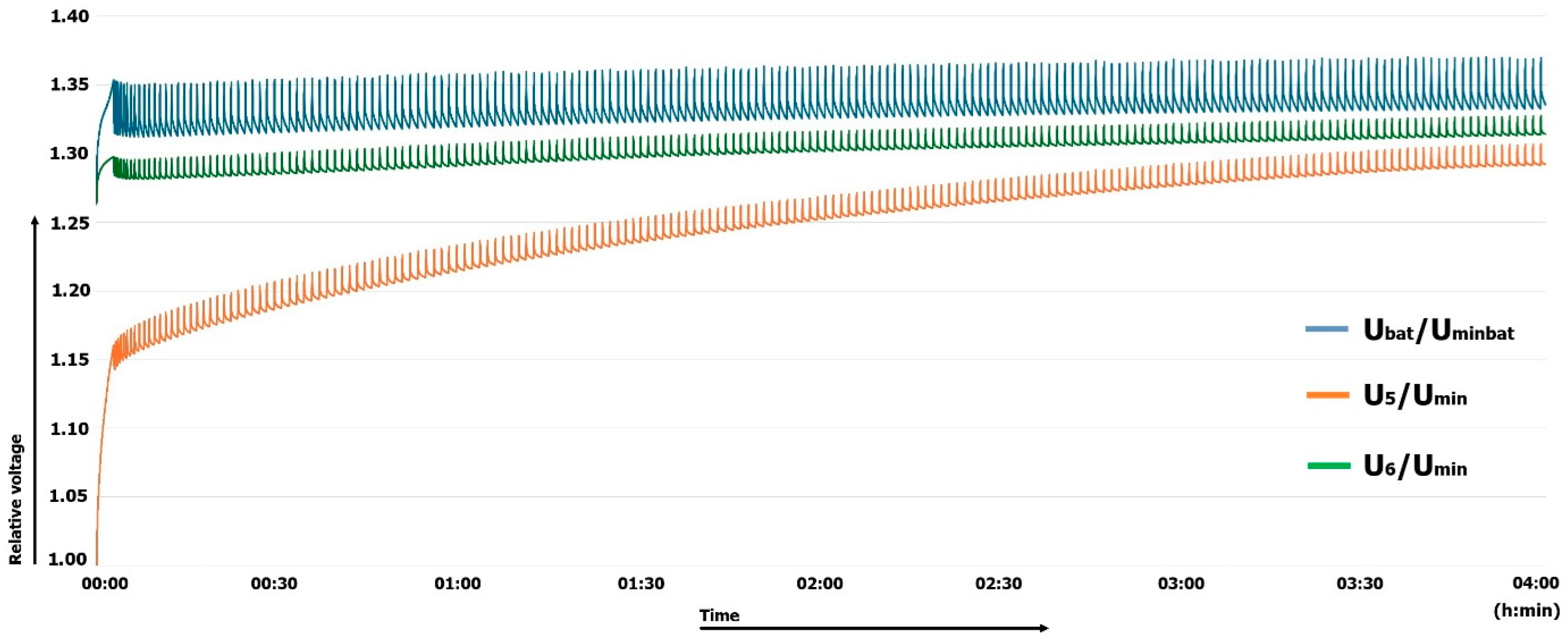

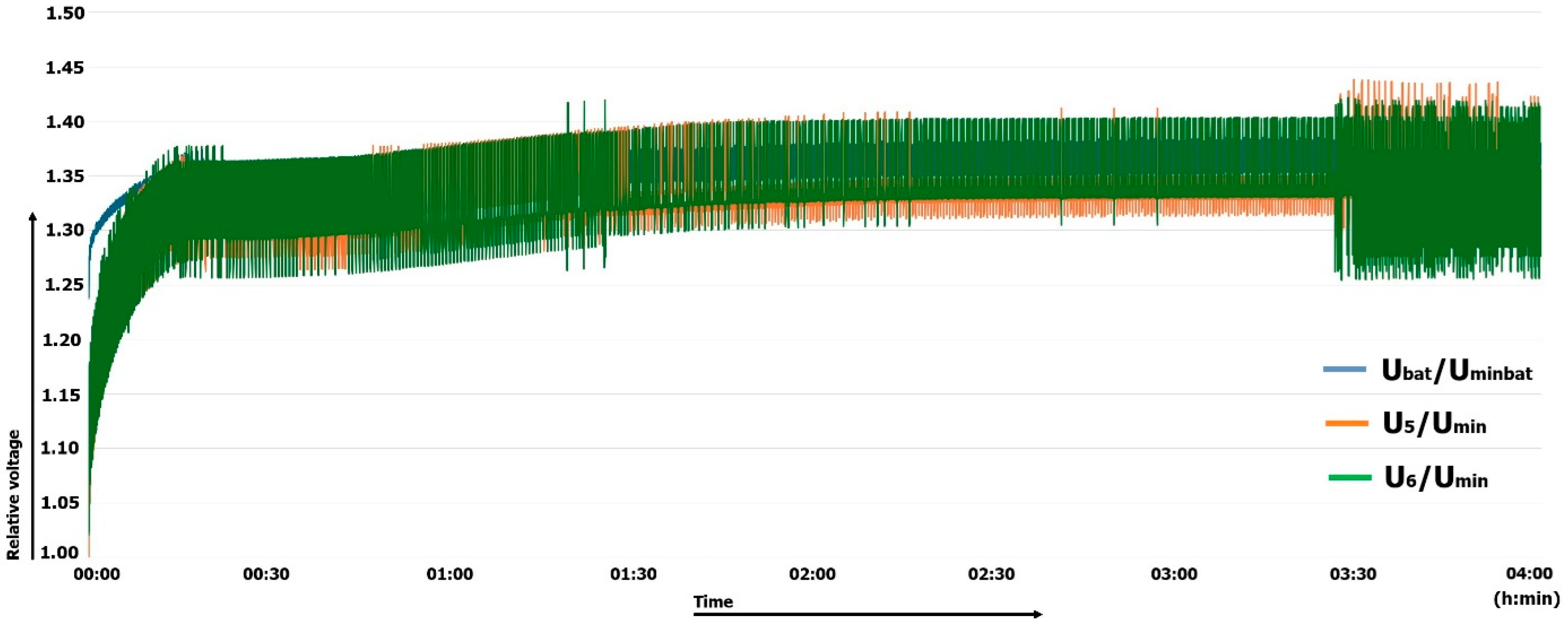

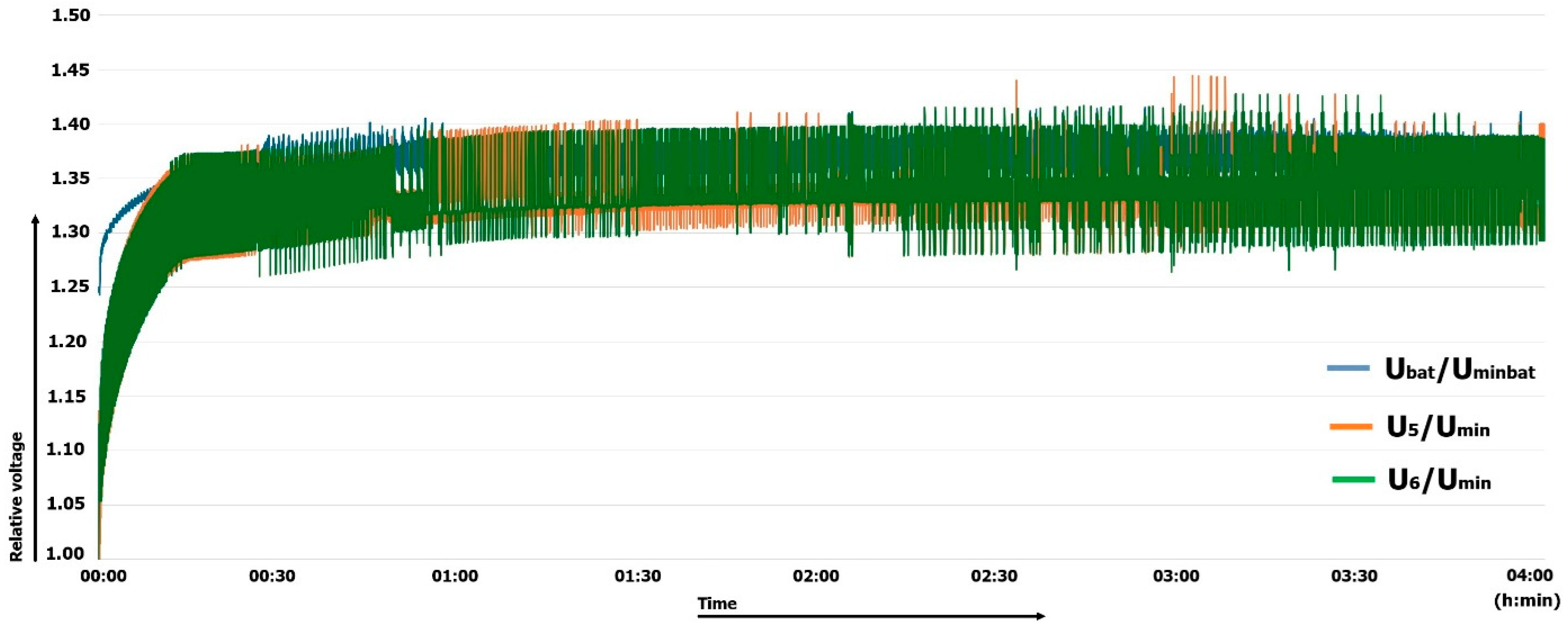

4. Hybrid BMS Experimental Results

4.1. Scope of Tests

4.2. Investigated Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, X.; Wang, Z.; Yin, B.; Shi, B.; Chen, J. Combustion characteristics of gases released from thermal runaway batteries under methane atmosphere. Energy 2025, 30, 136983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubaniewicz, T.H.; Barone, T.L.; Brown, C.B.; Thomas, R.A. Comparison of thermal runaway pressures within sealed enclosures for nickel manganese cobalt and iron phosphate cathode lithium-ion cells. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2022, 76, 104739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.Y.; Wang, G.F.; See, K.W.; Wang, Y.P.; Zhang, Y.; Zang, C.Y.; Li, S.; Xie, B. Explosion characteristic of CH4–H2-Air mixtures vented by encapsulated large-scale Li-ion battery under thermal runaway. Energy 2023, 278, 127816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisbona, D.; Snee, T. A review of hazards associated with primary lithium and lithium-ion batteries. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2011, 89, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carkhuff, B.G.; Demirev, P.A.; Srinivasan, R. Impedance-based battery management system for safety monitoring of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 6497–6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Schofield, N.; Emadi, A. Battery Balancing Methods: A Comprehensive Review. In Proceedings of the IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference, VPPC, Harbin, China, 3–5 September 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S. Cell Balancing Buys Extra Run Time and Battery Life. Analog. Appllcation J. 2009, 10, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jamasmie, C. Miners Should Adopt Next Generation Values to Battle Reputation Crisis. Mining.com. 2020. Available online: https://www.mining.com/miners-need-to-adopt-next-generation-values-to-battle-reputation-crisis-says-anglo-american-boss/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Battery University. Lithium-Ion Safety Concerns. 2016. Available online: https://batteryuniversity.com/article/lithium-ion-safety-concerns (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Ziegler, A.; Oeser, D.; Arndt, B.; Ackva, A. Comparison of Active and Passive Balancing by a Long Term Test Including a Post-Mortem Analysis of all Single Battery Cells. In Proceedings of the 2018 International IEEE Conference and Work Shop in Óbuda on Electrical and Power Engineering (CANDO-EPE), Budapest, Hungary, 20–21 November 2018; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vishwakarma, V.K.; Srivastava, S.; Mishra, V. Strategies of battery management systems in electric vehicles: A review. Int. J. Model. Simul. 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, K.; Xiao, P.; Li, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Guo, D.; Richard, Y.K.; Lu, Y. Killing two birds with one stone strategy inspired advanced batteries with superior thermal safety: A comprehensive evaluation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugumaran, G.; Amutha, P.N. An improved bi-switch flyback converter with loss analysis for active cell balancing of the lithium-ion battery string. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2024, 2024, 5556491. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, O.S.; Chinchwade, A.S.; Yetekar, S.N.; Jawale, S. Passive Cell Balancing using PI Controller. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Intelligent Technologies (CONIT), Bangalore, India, 21–23 June 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, S.L.; Kanawade, M.A.; Ankushe, R.S. An effective passive cell balancing technique for lithium-ion battery. Next Energy 2025, 8, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmi, M.A.M.M.; Yusoff, S.H.; Gunawan, T.S.; Zabidi, S.A.; Hanifah, M.S.A. Battery management system employing passive control method. Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst. (IJPEDS) 2025, 16, 35–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelin, D.; Brandis, A.; Kovačević, M.; Halak, F. Design and testing of a multimode capable passive battery management system. Energies 2022, 15, 4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnaudov, D.; Kishkin, K.; Dimitrov, V. Studying Convertors for Voltage Equalization in Energy Storage System with Active BMS. In Proceedings of the PCIM Europe 2024; International Exhibition and Conference for Power Electronics, Intelligent Motion, Renewable Energy and Energy Management, Nürnberg, Germany, 11–13 June 2024; VDE: Madrid, Spain, 2024; pp. 2263–2267. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Ma, K.; Xu, L.; Song, L.; Li, X.; Li, Y. A Joint Estimation Method Based on Kalman Filter of Battery State of Charge and State of Health. Coatings 2022, 12, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhulu, N.; Krishnam Naidu, R.S.R.; Falkowski-Gilski, P.; Divakarachari, P.B.; Roy, U. Energy management for PV powered hybrid storage system in electric vehicles using artificial neural network and aquila optimizer algorithm. Energies 2022, 15, 8540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpiel, W.; Polnik, B.; Orzech l Lesiak, K.; Miedzinski, B.; Habrych, M.; Debita, G.; Zamłynska, M.; Falkowski-Gilski, P. Influence of operation conditions on temperature hazard of lithium-iron-phosphate (LiFeP04) cells. Energies 2021, 14, 6728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpiel, W.; Deja, P.; Polnik, B.; Skóra, M.; Miedzinski, B.; Habrych, M.; Debita, G.; Zamłynska, M.; Falkowski-Gilski, P. Performance of passive and active balancing system of lithium batteries in onerous mine environment. Energies 2021, 14, 7624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpiel, W.; Polnik, B.; Miedzinski, B.; Habrych, M.; Debita, G. Lithium-iron-phosphate battery performance controlled by an active BMS based on the battery-to-cell method. Elektron. Ir Elektrotechnika 2022, 28, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpiel, W. Research on balancing BMS systems in a climatic chamber. Min. Mach. 2020, 53–63. Available online: https://www.komag.eu/images/maszynygornicze1/MM2020/MiningMachines3-2020/MM_3_2020_art6.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Specification of the LiFePO4 Battery of 3.2 V. Headway LFP38120(S) 10,000 mAh LiFePO4—Sklep BTO.pl. Available online: https://bto.pl/akumulatory/przemyslowe/akumulatory-lifepo4/843,headway-lfp38120-s-10000mah-lifepo4?utm_source=ceneo&utm_medium=referral&ceneo_cid=8b15804c-66f5-779a-0cc1-53dc157e5af0 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Kurpiel, W.; Miedziński, B.; Polnik, B. The Influence of the Balancing System on the Durability and Operational Safety of Lithium Cell Batteries in a Selected Mining Machine Power Supply System; Monograph: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025; p. 152. Available online: https://www.komag.eu/images/maszynygornicze1/monografie/MonografieNaukowe/Monografia_W_Kurpiel/Monografia_Nr_59_open.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025). (In Polish)

| Average Discharge Time [h:min] | Average Time to Charge Level (1.3Un on the Graph) During Charging and Balancing After the Load Shutdown [h:min] | Maximum Cell Temperature During Charging [°C] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passive BMS | 1:30 | 4:00 | 27 |

| Hybrid BMS | 2:25 | 1:30–1:45 | 28 |

| Parameter | Passive | Active | Hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating principle | Excess cell energy is dissipated as heat through a resistor. | Energy is transferred between cells (via DC–DC converters, capacitive or inductive charge shuttling). | Combination: active transfer for larger imbalances, passive balancing for protection. |

| Response speed (balancing time) | Slow—equalization of large differences can take hours (often active only in the final charging phase). | Fast—can equalize hundreds of mV within minutes to hours (depending on converter power). | Typically faster than passive—the active path quickly eliminates large imbalances; the passive path refines the final charging stage. |

| Balancing power per channel | Typically 0.5–5 W per channel during active balancing. | From ~0.5 W up to several tens of watts per channel (high-power topologies). | Active path usually limited (e.g., a few watts) + passive balancing (0.5–5 W). |

| Energy efficiency (energy recovery) | 0%—energy is lost as heat. | High—depending on topology, 70–95% (energy transferred to other cells or back to the system). | Intermediate—partial energy recovery (depending on active path share), typically 30–90%. |

| Thermal impact/heat losses | High local heat dissipation—module heating may be problematic in hot environments. | Lower cell losses (heat generated mainly in power components); converter cooling required depending on current levels. | Lower local losses than passive; total thermal load distributed between active and passive components. |

| Effect on cell lifetime | May accelerate cell degradation at elevated temperatures (imbalances persist longer). | Generally beneficial—better equalization reduces stress on lower-capacity cells. | Beneficial—combines improved equalization (less degradation) with lower local heating. |

| System complexity | Low—simple resistors, MOSFETs, and a basic controller. | High—converters, transformers/capacitors, power controllers. | Medium to high—requires integration of both paths and switching logic. |

| Wiring/isolation requirements | Simple voltage sensing—many measurement wires needed for large cell counts. | Additional power, converter wiring, galvanic isolation required. | Combination of both—modular design can reduce high-voltage wiring needs. |

| Communication/bus load | Low—simple telemetry gates. | High—more data, synchronization and power control required. | Medium—additional logic for coordinating active and passive operation. |

| EMI (Electromagnetic Interference) and EMC | Low—little power switching activity. | Higher EMI risk due to switching converters. | Medium—active elements generate EMI, but lower active power simplifies filtering. |

| Diagnostics and monitoring (EIS—Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy) | Limited—basic voltage and temperature measurements. | Advanced—enables dynamic measurements and integration with EIS/diagnostic systems. | Good diagnostic potential (depending on active circuit implementation). |

| Algorithm flexibility (aging adaptation) | Low—static thresholds, minimal adaptability. | High—dynamic strategies and adaptive algorithms to compensate for aging. | High—active path enables adaptation; passive path ensures safety. |

| Service/maintenance cost | Low—simple components. | Higher—specialized power components, module replacement costs. | Medium—active path maintenance is costlier, but passive path reduces total service effort. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurpiel, W.; Polnik, B.; Habrych, M.; Miedzinski, B. The Integration of Passive and Active Methods in a Hybrid BMS for a Suspended Mining Vehicle. Energies 2025, 18, 6465. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246465

Kurpiel W, Polnik B, Habrych M, Miedzinski B. The Integration of Passive and Active Methods in a Hybrid BMS for a Suspended Mining Vehicle. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6465. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246465

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurpiel, Wojciech, Bartosz Polnik, Marcin Habrych, and Bogdan Miedzinski. 2025. "The Integration of Passive and Active Methods in a Hybrid BMS for a Suspended Mining Vehicle" Energies 18, no. 24: 6465. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246465

APA StyleKurpiel, W., Polnik, B., Habrych, M., & Miedzinski, B. (2025). The Integration of Passive and Active Methods in a Hybrid BMS for a Suspended Mining Vehicle. Energies, 18(24), 6465. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246465