Evaluating Fuel Properties of SAF Blends: From Component-Based Estimation to Molecular Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

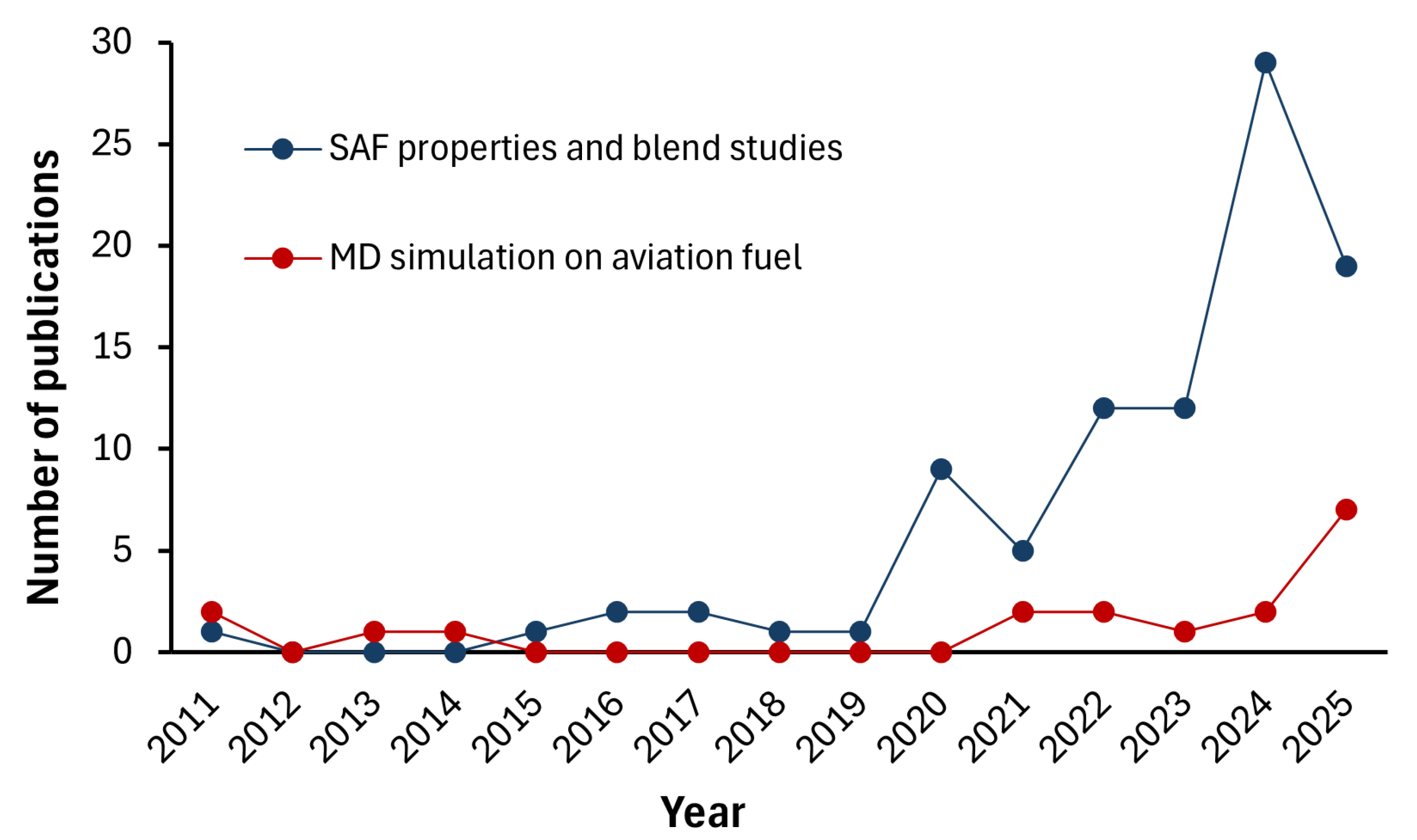

Recent Advances in SAF Blend Studies

2. SAF and Fuel Properties

2.1. SAF and Its Approved Production Pathways

- Lowers the net lifecycle of CO2 emissions from aviation operations.

- Improves aviation sustainability by outperforming petroleum-based jet fuel in economic, environmental and social impacts.

- Allows flexibility to produce drop-in jet fuel from numerous feedstocks and conversion technologies, without any modification in the existing engine and aircraft fuel systems, storage facilities or distribution infrastructure. As a result, SAF can be blended with traditional jet fuels.

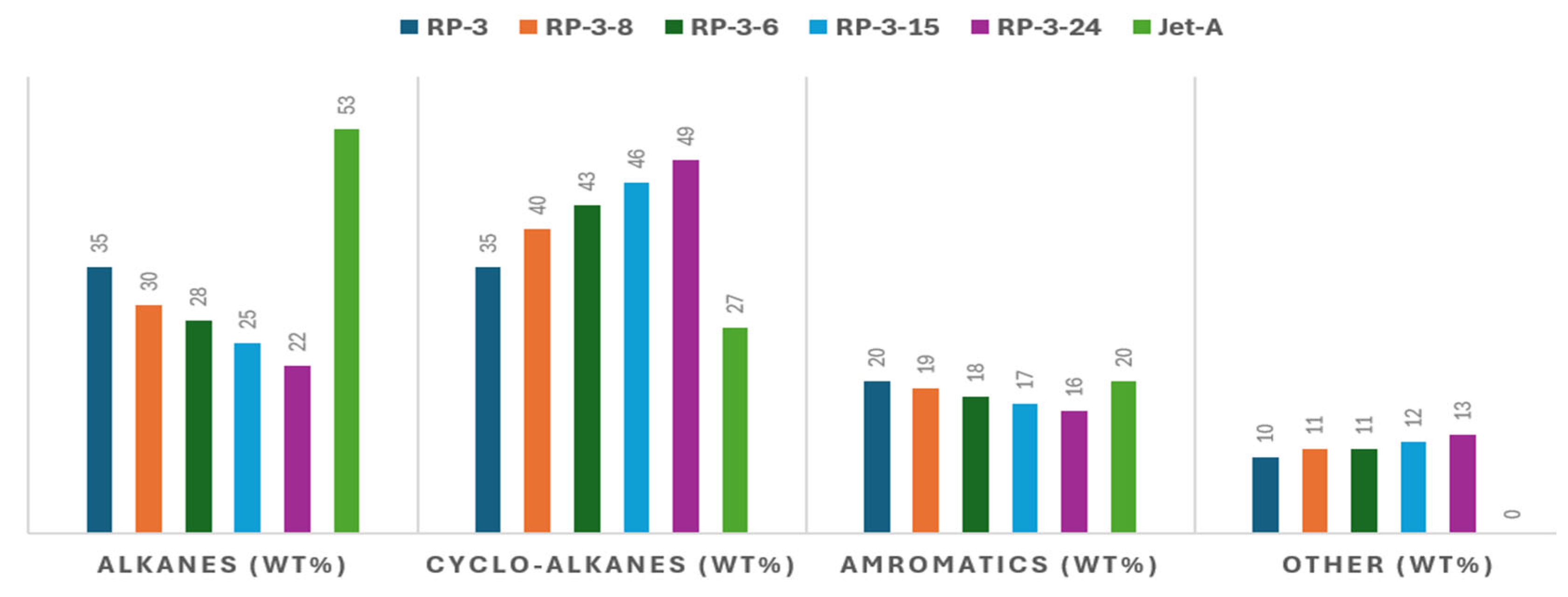

2.2. Fuel Properties

2.2.1. Density

2.2.2. Viscosity

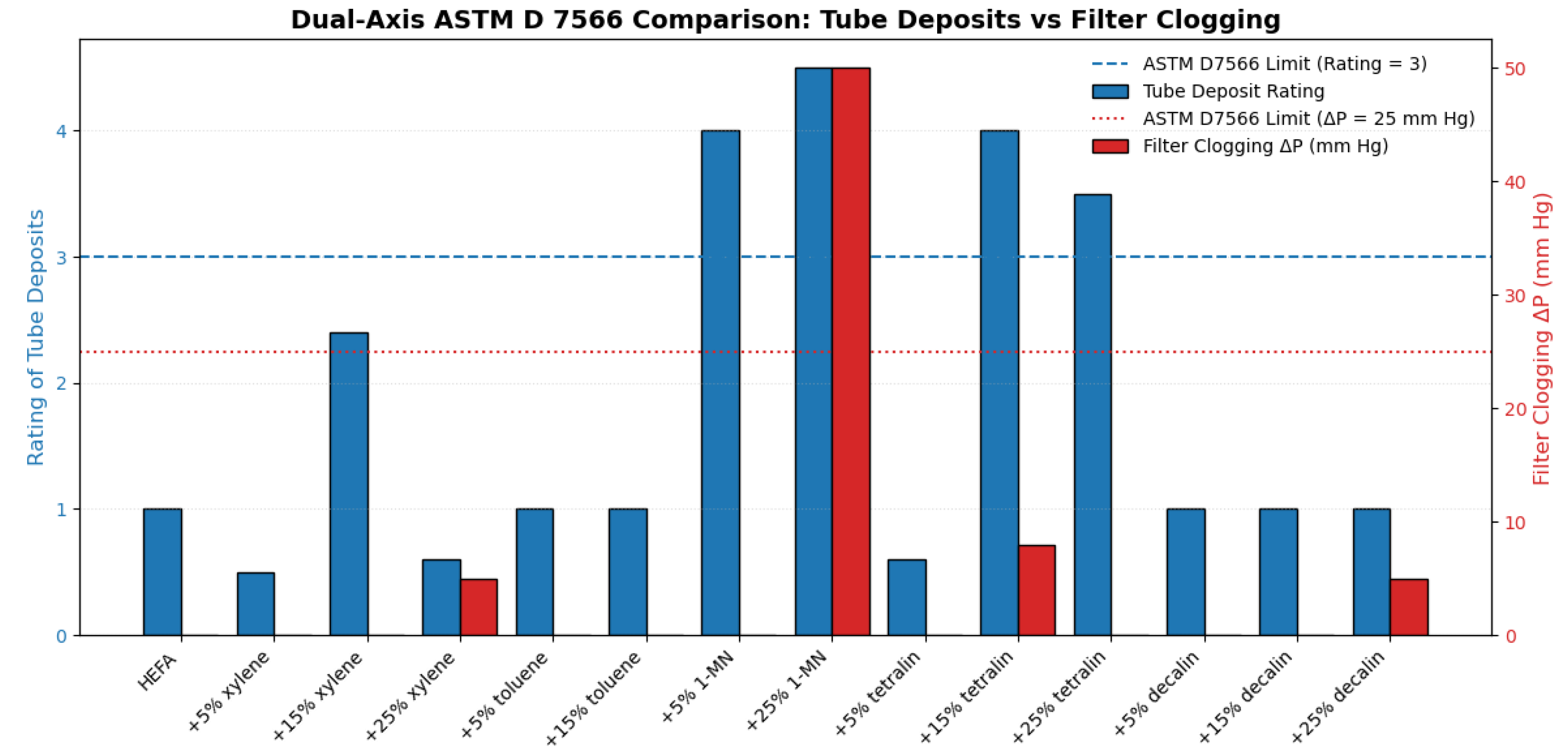

2.2.3. Thermal Stability

2.2.4. Energy Density and Specific Energy

2.2.5. Flash Point

3. MD Simulation for Hydrocarbon Fuel Properties

3.1. MD Software for Hydrocarbon Fuel Simulation

3.2. Force Fields for Hydrocarbon Fuel Applications

3.2.1. OPLS FFs

3.2.2. COMPASS FF

3.2.3. ReaxFF

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, B.; Ting, Z.J.; Zhao, M. Sustainable aviation fuels: Key opportunities and challenges in lowering carbon emissions for aviation industry. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, N.; Lis, T. The future of sustainable aviation fuels. Combust. Engines 2022, 61, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, H. Sustainable Aviation Fuel Implementation Strategies for European Airports. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, A.; Kousoulidou, M.; Lonza, L.; Weindorf, W. Considerations on GHG emissions and energy balances of promising aviation biofuel pathways. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Rijal, D. Sustainable Aviation Fuels for Clean Skies: Exploring the Potential and Perspectives of Strained Hydrocarbons. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 4904–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-Y.; Gao, J.-J.; Lu, Y.-Z.; Meng, H.; Li, C.-X. Acylation desulfurization of heavy cracking oil as a supplementary oil upgrading pathway. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 130, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IATA Association. Resolution on Net-Zero Carbon Emissions by 2050; IATA: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021; Available online: https://www.iata.org/contentassets/dcd25da635cd4c3697b5d0d8ae32e159/iata-agm-resolution-on-net-zero-carbon-emissions.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Australian Government, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Energy, the Environment and Water. International Climate Action. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/international-climate-action (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Forum, W.E. Quadrupling Clean Fuels by 2035: COP30 Pledge to Scale Sustainable Aviation Fuels. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/11/quadrupling-clean-fuels-by-2035/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Epstein, C. IATA Report Urges SAF Policy Changes: SAF Output Still Not Enough to Meet Needs. 2025. Available online: https://www.ainonline.com/aviation-news/aerospace/2025-06-10/iata-report-urges-saf-policy-changes (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Boeing. Boeing Makes Its Largest Purchase of Blended Sustainable Aviation Fuel. Available online: https://investors.boeing.com/investors/news/press-release-details/2024/Boeing-Makes-its-Largest-Purchase-of-Blended-Sustainable-Aviation-Fuel/default.aspx (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Airbus. Pioneering Sustainable Aerospace. 2025. Available online: https://www.airbus.com/sites/g/files/jlcbta136/files/2025-04/2025_Airbus_Pioneering_sustainable_aerospace_publication.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Yang, Z.; Bell, D.C.; Cronin, D.J.; Boehm, R.; Heyne, J.; Ramasamy, K.K. Volatility Measurements of Sustainable Aviation Fuels: A Comparative Study of D86 and D2887 Methods. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 7414–7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doliente, S.S.; Narayan, A.; Tapia, J.F.D.; Samsatli, N.J.; Zhao, Y.; Samsatli, S. Bio-aviation fuel: A comprehensive review and analysis of the supply chain components. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonti, D. Sustainable Aviation Fuels: The challenge of decarbonization. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 1202–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caceres-Martinez, L.E.; Lopez, J.S.; Dagle, R.A.; Gillespie, R.; Kenttämaa, H.I.; Kilaz, G. Influence of blending cycloalkanes on the energy content, density, and viscosity of Jet-A. Fuel 2024, 358, 129986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pérez, M.A.; Serrano-Ruiz, J.C. Catalytic production of jet fuels from biomass. Molecules 2020, 25, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Gong, S.; Pan, L.; Deng, C.; Zou, J.-J.; Zhang, X. Impact of deep hydrogenation on jet fuel oxidation and deposition. Fuel 2020, 264, 116843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, O.R.; Tao, L.; Abdullah, Z.; Talmadge, M.; Milbrandt, A.; Smolinski, S.; Moriarty, K.; Bhatt, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ravi, V. Sustainable Aviation Fuel State-of-Industry Report: Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids Pathway; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Calderon, O.R.; Tao, L.; Abdullah, Z.; Moriarty, K.; Smolinski, S.; Milbrandt, A.; Talmadge, M.; Bhatt, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ravi, V. Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) State-of-Industry Report: State of SAF Production Process; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, M.; Wang, F. Fuelling a clean future: A systematic review of Techno-Economic and Life Cycle assessments in E-Fuel Development. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Fernandez, E.V.; Santos, J.L.; Alsaadi, D.K.; Bavykina, A.; Gallo, J.M.R.; Gascon, J. Potential pathways for CO 2 utilization in sustainable aviation fuel synthesis. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 530–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosir, S.; Heyne, J.; Graham, J. A machine learning framework for drop-in volume swell characteristics of sustainable aviation fuel. Fuel 2020, 274, 117832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijal, D.; Vasilyev, V.; Wang, F. Machine Learning for High Energy Density Hydrocarbons for Sustainable Aviation Fuel. ChemRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzawska, P. Overview of Sustainable Aviation Fuels including emission of particulate matter and harmful gaseous exhaust gas compounds. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 59, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service, I.R. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA)—Sustainable Aviation Fuel Credit Guidance; U.S. Department of the Treasury: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Holladay, J.; Abdullah, Z.; Heyne, J. Sustainable Aviation Fuel: Review of Technical Pathways; Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE): Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, K.; Kvien, A. US Airport Infrastructure and Sustainable Aviation Fuel; National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, B.; Johnson, D.; Thompson, T.; Rosenberg, F.L.; Driver, J.; Biscardi, G.P.; Mohtadi, M.K.; Mohtadi, N.J. R&D Control Study: Plan for Future Jet Fuel Distribution Quality Control and Description of Fuel Properties Catalog; Federal Aviation Administration. Office of Environment and Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, J.; Suspes, A.; Roa, S.; González, C.; Castro, H. Total petroleum hydrocarbons by gas chromatography in Colombian waters and soils. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 8, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, T.; Winter, E.; Grote, U. Economic impacts of power-to-liquid fuels in aviation: A general equilibrium analysis of production and utilization in Germany. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 23, 100632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.; Machado, P.; Da Silva, A.; Saltar, Y.; Ribeiro, C.; Nascimento, C.; Dowling, A. Sustainable aviation fuel technologies, costs, emissions, policies, and markets: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yu, X. An Overview of the Sustainable Aviation Fuel: LCA, TEA, and the Sustainability Analysis. Eng. Proc. 2024, 80, 3. [Google Scholar]

- IEA Bioenergy Task 39. Progress in Commercialization of Biojet/Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF): Technologies and Policies; IEA Bioenergy: Wellington, New Zealand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wandelt, S.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Sustainable aviation fuels: A meta-review of surveys and key challenges. J. Air Transp. Res. Soc. 2025, 4, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, M.; Narappa, A.B.; Namboodiri, T.; Chai, Y.; Babu, M.; Jennings, J.S.; Gao, Y.; Tasneem, S.; Lam, J.; Talluri, K.R. Forging a sustainable sky: Unveiling the pillars of aviation e-fuel production for carbon emission circularity. IScience 2024, 27, 109154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporan, E.; Edwards, T.; Shafer, L.; DeWitt, M.J.; Klingshirn, C.; Zabarnick, S.; West, Z.; Striebich, R.; Graham, J.; Klein, J. Chemical, thermal stability, seal swell, and emissions studies of alternative jet fuels. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, M.J.; Corporan, E.; Graham, J.; Minus, D. Effects of aromatic type and concentration in Fischer−Tropsch fuel on emissions production and material compatibility. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 2411–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.P.; Han, Y.; Kramlich, J.; Garcia-Perez, M. Chemical Composition and Fuel Properties of Alternative Jet Fuels; Federal Aviation Administration. Center of Excellence for Alternative Jet Fuels and Environment: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blakey, S.; Rye, L.; Wilson, C.W. Aviation gas turbine alternative fuels: A review. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2011, 33, 2863–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). ASA–DLR Study Finds Sustainable Aviation Fuel Can Reduce Contrails. NASA. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/news-release/nasa-dlr-study-finds-sustainable-aviation-fuel-can-reduce-contrails/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Billingsley, M.; Edwards, T.; Shafer, L.; Bruno, T. Extent and impacts of hydrocarbon fuel compositional variability for aerospace propulsion systems. In Proceedings of the 46th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Nashville, TN, USA, 25–28 July 2010; p. 6824. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Jia, T.; Pan, L.; Liu, Q.; Fang, Y.; Zou, J.-J.; Zhang, X. Review on the relationship between liquid aerospace fuel composition and their physicochemical properties. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2021, 27, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, C.A.; Roets, P.N. Properties, characteristics, and combustion performance of sasol fully synthetic jet fuel. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power. 2009, 131, 041502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7566-18; Standard Specification for Aviation Turbine Fuel Containing Synthesized Hydrocarbons. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM D1655-18; Standard Specification for Aviation Turbine Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- The Engineering ToolBox. Hydrocarbons, Linear Alcohols and Acids–Densities. Available online: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/density-alkane-alkene-benzene-carbon-number-alcohol-acid-alkyl-alkyne-d_1939.html (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Feldhausen, J.; Bell, D.C.; Yang, Z.; Faulhaber, C.; Boehm, R.; Heyne, J. Synthetic aromatic kerosene property prediction improvements with isomer specific characterization via GCxGC and vacuum ultraviolet spectroscopy. Fuel 2022, 326, 125002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Bell, D.C.; Feldhausen, J.; Rauch, B.; Heyne, J. Quantifying isomeric effects: A key factor in aviation fuel assessment and design. Fuel 2024, 357, 129912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Li, G.; Guo, Y.; Xu, L.; Fang, W. Excess molar volume along with viscosity, flash point, and refractive index for binary mixtures of cis-decalin or trans-decalin with C9 to C11 n-alkanes. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2013, 58, 2224–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Li, G.; He, G.; Guo, Y.; Xu, L.; Fang, W. Impacts of hydrogen to carbon ratio (H/C) on fundamental properties and supercritical cracking performance of hydrocarbon fuels. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Astrath, N.G.; Pedreira, P.R.; Guimarães, F.B.; Gieleciak, R.; Wen, Q.; Michaelian, K.H.; Fairbridge, C.; Malacarne, L.C.; Rohling, J.H. Correlations among thermophysical properties, ignition quality, volatility, chemical composition, and kinematic viscosity of petroleum distillates. Fuel 2016, 163, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Tobar, M.; Cabrera Ojeda, O.; Crespo Montaño, F. Impact of Oil Viscosity on Emissions and Fuel Efficiency at High Altitudes: A Response Surface Methodology Analysis. Lubricants 2024, 12, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, A.; Benjumea, P.; Cortés, F.B.; Ruiz, M.A. Chemical composition and low-temperature fluidity properties of jet fuels. Processes 2021, 9, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.; Xu, C. Quantitative structure–property relationship model for hydrocarbon liquid viscosity prediction. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 3290–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zéberg-Mikkelsen, C.K.; Baylaucq, A.; Barrouhou, M.; Boned, C. The effect of stereoisomerism on dynamic viscosity: A study of cis-decalin and trans-decalin versus pressure and temperature. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 1547–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D445-12; Standard Test Method for Kinematic Viscosity of Transparent and Opaque Liquids (and Calculation of Dynamic Viscosity). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- Morris, R.E.; Hammond, M.H.; Cramer, J.A.; Johnson, K.J.; Giordano, B.C.; Kramer, K.E.; Rose-Pehrsson, S.L. Rapid fuel quality surveillance through chemometric modeling of near-infrared spectra. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 1610–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.A.; Morris, R.E.; Rose-Pehrsson, S.L. Use of genetic algorithms to improve partial least squares fuel property and synthetic fuel modeling from near-infrared spectra. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 5560–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, S.H.; Azamifard, A.; Hosseini, S.-A.; Shamsoddini, M.-J.; Alizadeh, N. Toward a predictive model for predicting viscosity of natural and hydrocarbon gases. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2014, 20, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnecki, J.; Gawron, B. A method of assessing the tendency of aviation fuels to generate thermal degradation products under the influence of high temperatures. J. KONES 2017, 24, 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J.; Sadat, Y.; Dwyer, M.; Ghali, P.; Khandelwal, B. Thermal stability and impact of alternative fuels. In Aviation Fuels; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 149–218. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Eser, S.; Schobert, H.H.; Hatcher, P.G. Pyrolytic degradation studies of a coal-derived and a petroleum-derived aviation jet fuel. Energy Fuels 1993, 7, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. A Parametric Study of Jet Fuel Thermal Stability; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

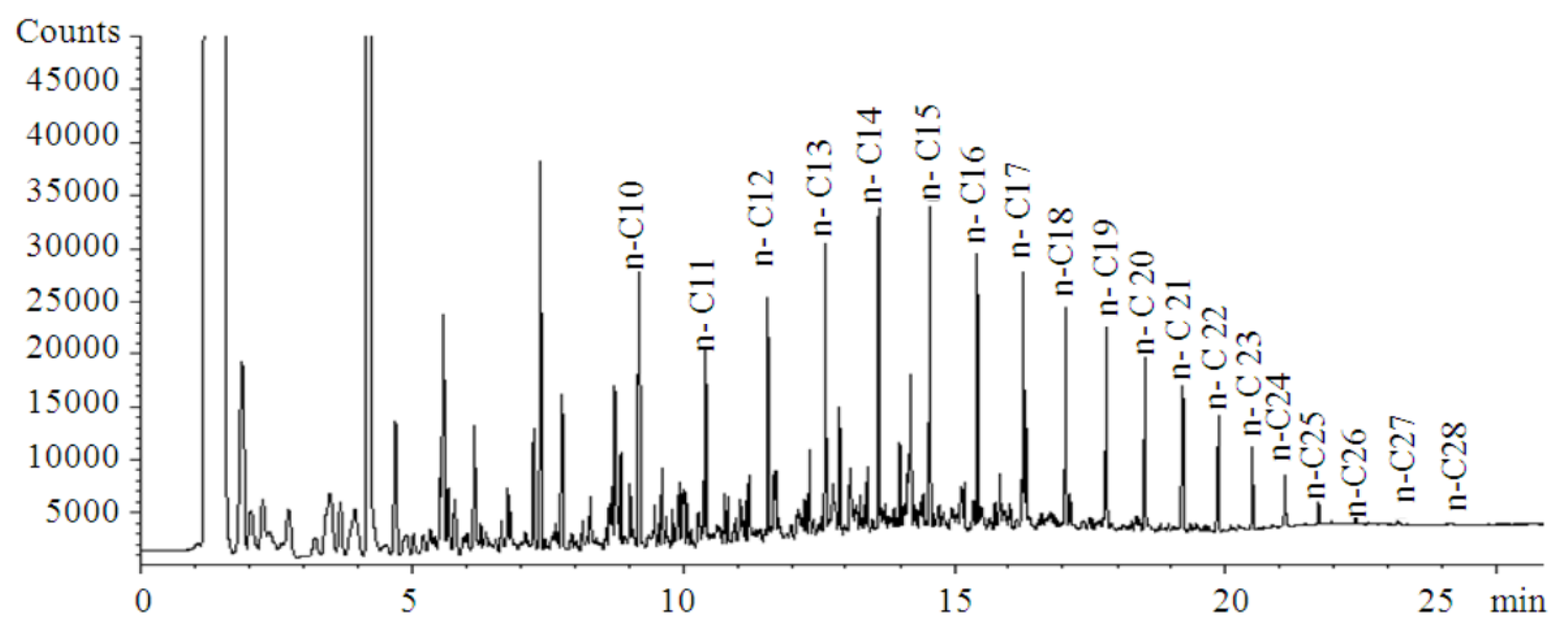

- van der Westhuizen, R.; Ajam, M.; De Coning, P.; Beens, J.; de Villiers, A.; Sandra, P. Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography for the analysis of synthetic and crude-derived jet fuels. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 4478–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzięgielewski, W.; Gawron, B. Problem stabilności termicznej współczesnych paliw do turbinowych silników lotniczych–badania wstępne. J. KONBIN 2012, 21, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xin, Z.; Corscadden, K.; Niu, H. An overview on performance characteristics of bio-jet fuels. Fuel 2019, 237, 916–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, M.J.; West, Z.; Zabarnick, S.; Shafer, L.; Striebich, R.; Higgins, A.; Edwards, T. Effect of aromatics on the thermal-oxidative stability of synthetic paraffinic kerosene. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 3696–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, A.B.; Kaoubi, S.; Starck, L. Toward an optimal formulation of alternative jet fuels: Enhanced oxidation and thermal stability by the addition of cyclic molecules. Fuel 2016, 173, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yin, L.; Ling, L.; Zhang, R.; Yan, G.; Wang, J.; Lu, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, B. The prediction and assessment of properties for high energy density fuel–Adamantane derivatives: The combined DFT and molecular dynamics simulation. Fuel 2023, 343, 127975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hileman, J.I.; Stratton, R.W.; Donohoo, P.E. Energy content and alternative jet fuel viability. J. Propuls. Power 2010, 26, 1184–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S. Life Cycle Analysis of the Production of Aviation Fuels Using the CE-CERT Process; UC Riverside: Riverside, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Company, C.P. Aviation Fuels—Technical Review; Chevron Products Company: San Ramon, CA, USA, 2007; Available online: https://www.chevron.com/-/media/chevron/operations/documents/aviation-tech-review.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

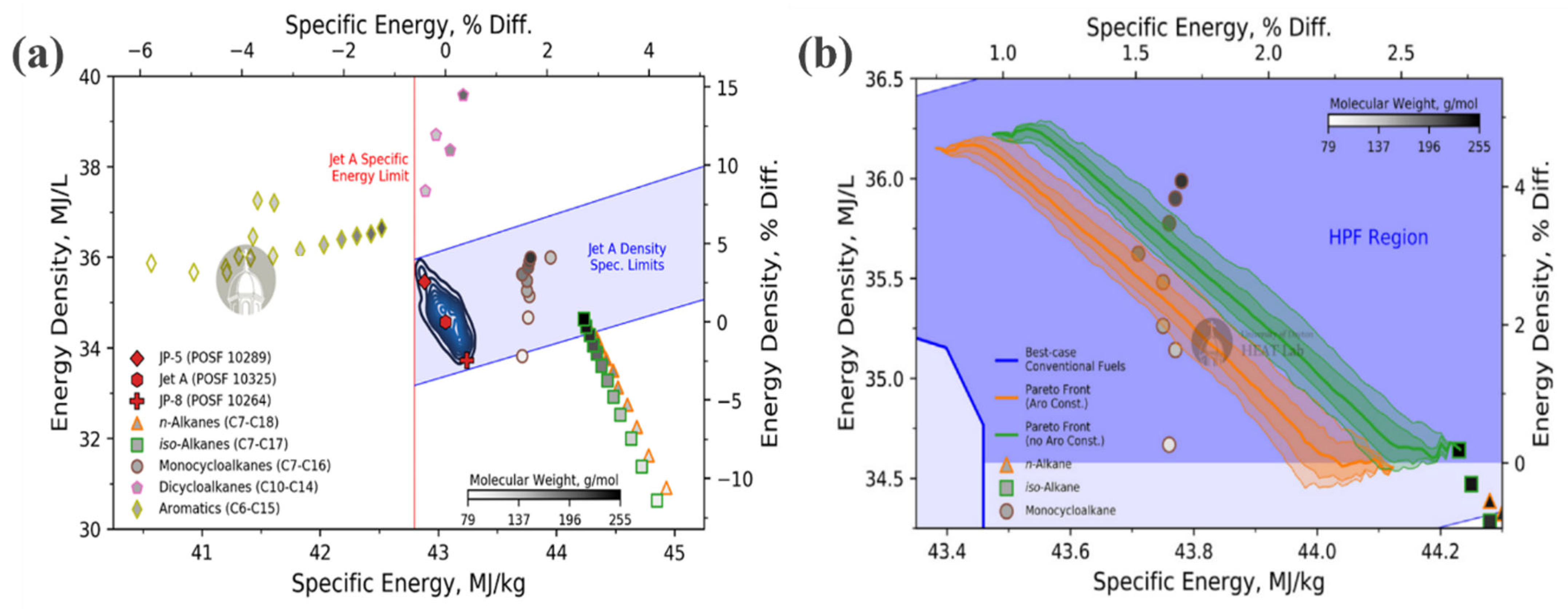

- Kosir, S.; Stachler, R.; Heyne, J.; Hauck, F. High-performance jet fuel optimization and uncertainty analysis. Fuel 2020, 281, 118718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoon, L.Y.; Mustaffa, A.A.; Hashim, H.; Mat, R. A review of flash point prediction models for flammable liquid mixtures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 12553–12565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, T.; Moghaddam, A.Z. Measurement and calculation of flash point of binary aqueous–organic and organic–organic solutions. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2011, 312, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J.; Nuyt, C.; Lee, J.; Woodrow, J. Flash Point and Chemical Composition of Aviation Kerosene (Jet A); Report FM99-4; Graduate Aeronautical Laboratories California Institute of Technology Pasadena, Explosion Dynamics Laboratory: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Do Nascimento, D.C.; Carareto, N.D.D.; Neto, A.M.B.; Gerbaud, V.; da Costa, M.C. Flash point prediction with UNIFAC type models of ethylic biodiesel and binary/ternary mixtures of FAEEs. Fuel 2020, 281, 118717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakzian, K.; Liaw, H.-J. Flash point study of ternary mixtures comprising binary constituents that exhibit maximum flash point behavior and minimum flash point behavior. Thermochim. Acta 2022, 713, 179246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7566-19; Standard Specification for Aviation Turbine Fuel Containing Synthesized Hydrocarbons. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Chuck, C.J.; Donnelly, J. The compatibility of potential bioderived fuels with Jet A-1 aviation kerosene. Appl. Energy 2014, 118, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ToolBox, T.E. Hydrocarbons—Autoignition Temperatures and Flash Points. Available online: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/flash-point-autoignition-temperature-kindling-hydrocarbons-alkane-alkene-d_1941.html (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Elmalik, E.E.; Raza, B.; Warrag, S.; Ramadhan, H.; Alborzi, E.; Elbashir, N.O. Role of hydrocarbon building blocks on gas-to-liquid derived synthetic jet fuel characteristics. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 1856–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, M. Estimation of the flash points of saturated and unsaturated hydrocarbons. Indian J. Eng. Mater. Sci. 2012, 19, 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, X. Insight of low flammability limit on sustainable aviation fuel blend and prediction by ANN model. Energy AI 2024, 18, 100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagawa, H.; Kitamura, K. An introduction of molecular dynamics simulation. J. Synth. Org. Chem. 1997, 55, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, D. Molecular dynamics simulation. Comput. Sci. Eng. 1999, 1, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G. Computational Materials Science: An Introduction; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.P.; Aktulga, H.M.; Berger, R.; Bolintineanu, D.S.; Brown, W.M.; Crozier, P.S.; In’t Veld, P.J.; Kohlmeyer, A.; Moore, S.G.; Nguyen, T.D. LAMMPS-a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2022, 271, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LAMMPS Molecular Dynamics Simulator. Sandia National Laboratories. Available online: https://www.lammps.org (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Berendsen, H.J.; van der Spoel, D.; van Drunen, R. GROMACS: A message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995, 91, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.; Kutzner, C.; Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, U.; Gogoi, R.; Sethi, S.K.; Verma, A. Introduction to materials studio software for the atomistic-scale simulations. In Forcefields for Atomistic-Scale Simulations: Materials and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, B.R.; Brooks, C.L., III; Mackerell, A.D., Jr.; Nilsson, L.; Petrella, R.J.; Roux, B.; Won, Y.; Archontis, G.; Bartels, C.; Boresch, S. CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 1545–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomon-Ferrer, R.; Case, D.; Walker, R. An overview of the Amber biomolecular simulation package. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2013, 3, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannozzi, P.; Baroni, S.; Bonini, N.; Calandra, M.; Car, R.; Cavazzoni, C.; Ceresoli, D.; Chiarotti, G.L.; Cococcioni, M.; Dabo, I. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: A modular and open-source software project for quantumsimulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2009, 21, 395502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, T.D.; Iannuzzi, M.; Del Ben, M.; Rybkin, V.V.; Seewald, P.; Stein, F.; Laino, T.; Khaliullin, R.Z.; Schütt, O.; Schiffmann, F. CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package-Quickstep: Efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 194103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindon, C.; Harris, S.; Evans, T.; Novik, K.; Coveney, P.; Laughton, C. Large-scale molecular dynamics simulation of DNA: Implementation and validation of the AMBER98 force field in LAMMPS. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2004, 362, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowthaman, S. A review on mechanical and material characterisation through molecular dynamics using large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS). Funct. Compos. Struct. 2023, 5, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Qing, S.; Luo, Z.; Liu, Y. Investigation of nanoparticles shape that influence the thermal conductivity and viscosity in argon-based nanofluids: A molecular dynamics simulation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 207, 124031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

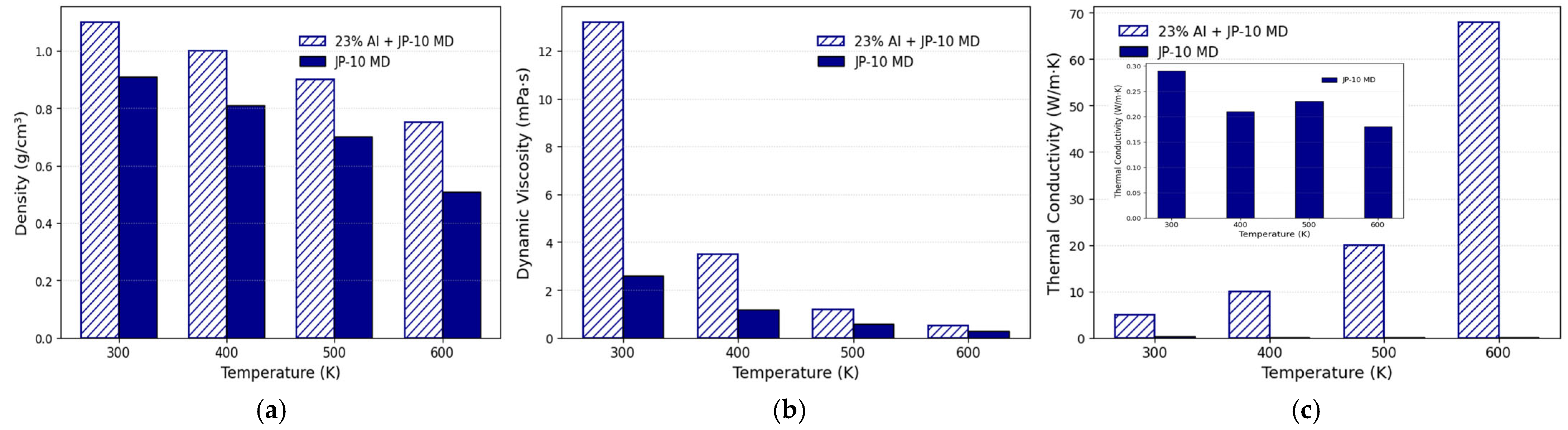

- Wen, M.; Jin, H.; Wang, S.; Fan, J. Molecular dynamics simulation study on the dynamic viscosity and thermal conductivity of high-energy hydrocarbon fuel Al/JP-10. Fuel 2025, 386, 134236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Mandal, A. Overview of LAMMPS. In Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Nanocomposites Using BIOVIA Materials Studio, Lammps and Gromacs; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Tao, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Cao, B. Molecular dynamics simulation of thermophysical properties of binary RP-3 surrogate fuel mixtures containing trimethylbenzene, n-decane, and n-dodecane. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 359, 119258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

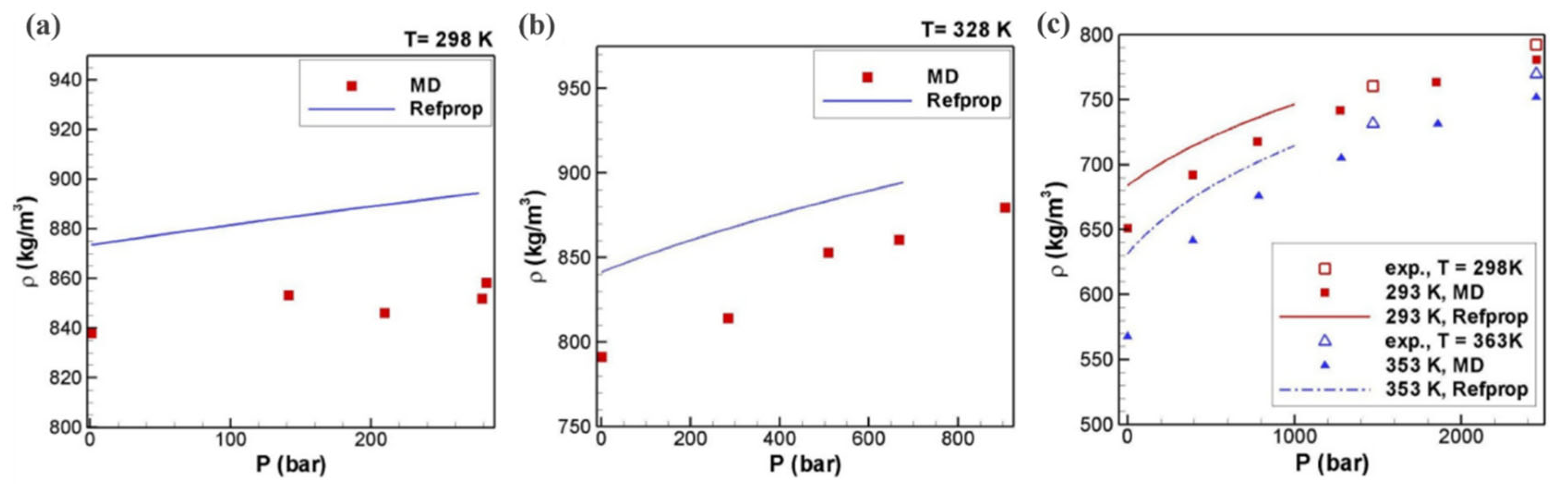

- Wang, Y.; Gong, S.; Li, L.; Liu, G. Sub-to-supercritical properties and inhomogeneity of JP-10 using molecular dynamics simulation. Fuel 2021, 288, 119696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratyuk, N.; Nikolskiy, V.; Pavlov, D.; Stegailov, V. GPU-accelerated molecular dynamics: State-of-art software performance and porting from Nvidia CUDA to AMD HIP. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl. 2021, 35, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, J.; Nguyen, T.D.; Anderson, J.A.; Lui, P.; Spiga, F.; Millan, J.A.; Morse, D.C.; Glotzer, S.C. Strong scaling of general-purpose molecular dynamics simulations on GPUs. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2015, 192, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R.P.; Hünenberger, P.H.; Tironi, I.G.; Mark, A.E.; Billeter, S.R.; Fennen, J.; Torda, A.E.; Huber, T.; Krüger, P.; van Gunsteren, W.F. The GROMOS Biomolecular Simulation Program Package. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 3596–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mermelstein, D.J.; Lin, C.; Nelson, G.; Kretsch, R.; McCammon, J.A.; Walker, R.C. Fast and flexible gpu accelerated binding free energy calculations within the amber molecular dynamics package. J. Comput. Chem. 2018, 39, 1354–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaus, J.W.; Pierce, L.T.; Walker, R.C.; McCammon, J.A. Improving the efficiency of free energy calculations in the amber molecular dynamics package. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 4131–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, N.R.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.K.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI multicomponent assembler for modeling and simulation of complex multicomponent systems. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 529a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, A.; Hussain, A.; Cervantes, L.F.; Lai, T.T.; Brooks III, C.L. Exploring the limits of the generalized CHARMM and AMBER force fields through predictions of hydration free energy of small molecules. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 4089–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croitoru, A.; Kumar, A.; Lambry, J.-C.; Lee, J.; Sharif, S.; Yu, W.; MacKerell Jr, A.D.; Aleksandrov, A. Increasing the Accuracy and Robustness of the CHARMM General Force Field with an Expanded Training Set. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2025, 21, 3044–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikitin, A.M.; Milchevskiy, Y.V.; Lyubartsev, A.P. A new AMBER-compatible force field parameter set for alkanes. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashurin, O.V.; Kondratyuk, N.D.; Lankin, A.V.; Norman, G.E. Force field comparison for molecular dynamics simulations of liquid membranes. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 416, 126347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. COMPASS: An ab initio force-field optimized for condensed-phase applications overview with details on alkane and benzene compounds. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 7338–7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodda, L.S.; Cabeza de Vaca, I.; Tirado-Rives, J.; Jorgensen, W.L. LigParGen web server: An automatic OPLS-AA parameter generator for organic ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W331–W336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; De Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell Jr, A.D. CHARMM36m: An improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggimann, B.L.; Sunnarborg, A.J.; Stern, H.D.; Bliss, A.P.; Siepmann, J.I. An online parameter and property database for the TraPPE force field. Mol. Simul. 2014, 40, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenoweth, K.; Van Duin, A.C.; Goddard, W.A. ReaxFF reactive force field for molecular dynamics simulations of hydrocarbon oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 1040–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioupis, L.I.; Maginn, E.J. Rheology, dynamics, and structure of hydrocarbon blends: A molecular dynamics study of n-hexane/n-hexadecane mixtures. Chem. Eng. J. 1999, 74, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, R.S.; Lima, A.P.; Chen, C.; Rochinha, F.A.; Mira, D.; Jiang, X. Towards predicting liquid fuel physicochemical properties using molecular dynamics guided machine learning models. Fuel 2022, 329, 125415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, C.E.; Joseph, A. Evaluation of the OPLS-AA force field for the study of structural and energetic aspects of molecular organic crystals. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 3023–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Amin, K.S.; Schneider, M.; Lim, C.; Salahub, D.; Baldauf, C. System-Specific Parameter Optimization for Nonpolarizable and Polarizable Force Fields. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024, 20, 1448–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rego, T.; Silva, G.M.; Goldmann, M.; Filipe, E.J.; Morgado, P. Optimized all-atom force field for alkynes within the OPLS-AA framework. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2022, 554, 113314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, A.; Pasenkiewicz-Gierula, M.; Cramariuc, O.; Vattulainen, I.; Rog, T. Refined OPLS all-atom force field for saturated phosphatidylcholine bilayers at full hydration. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 4571–4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Luo, H.H.; Tieleman, D.P. Modifying the OPLS-AA force field to improve hydration free energies for several amino acid side chains using new atomic charges and an off-plane charge model for aromatic residues. J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, S.W.; Pluhackova, K.; Böckmann, R.A. Optimization of the OPLS-AA force field for long hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremanpour, M.M.; Tirado-Rives, J.; Jorgensen, W.L. Refinement of the Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations Force Field for Thermodynamics and Dynamics of Liquid Alkanes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 5896–5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, L.Q.; Lander, H.; Edwards, T.; Harrison Iii, W. Advanced aviation fuels: A look ahead via a historical perspective. Fuel 2001, 80, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prak, D.J.L.; Trulove, P.C.; Cowart, J.S. Density, viscosity, speed of sound, surface tension, and flash point of binary mixtures of n-hexadecane and 2, 2, 4, 4, 6, 8, 8-heptamethylnonane and of algal-based hydrotreated renewable diesel. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2013, 58, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luning Prak, D.J.; Cowart, J.S.; Hamilton, L.J.; Hoang, D.T.; Brown, E.K.; Trulove, P.C. Development of a surrogate mixture for algal-based hydrotreated renewable diesel. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T. “Kerosene” Fuels for Aerospace Propulsion-Composition and Properties. In Proceedings of the 38th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 7–10 July 2002; p. 3874. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, B.L.; Morrow, B.H.; Van Nostrand, K.; Luning Prak, D.; Trulove, P.C.; Morris, R.E.; Schall, J.D.; Harrison, J.A.; Knippenberg, M.T. Elucidating the properties of surrogate fuel mixtures using molecular dynamics. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyanitsky, A.; Kazakov, A.F.; Bruno, T.J.; Huber, M.L. Mass Diffusion of Organic Fluids: A Molecular Dynamics Perspective; NIST Technical Note 2013; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shateri, A.; Yang, Z.; Xie, J. Machine learning-based molecular dynamics studies on predicting thermophysical properties of ethanol–octane blends. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 1070–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadiya, P.; Adhikari, J. Prediction of thermodynamic properties of m-cresol: Comparison of TraPPE-UA and OPLS-AA force fields. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 425, 127211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratek, M.; Wójcik-Augustyn, A.; Kania, A.; Majta, J.; Murzyn, K. Condensed phase properties of n-pentadecane emerging from application of biomolecular force fields. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2020, 67, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lide, D.R. Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, Internet Version; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y. Molecular dynamics investigation on structural and interfacial characteristics of aerosol particles containing mixed organic components. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 319, 120305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Ghahremanpour, M.M.; Saar, A.; Tirado-Rives, J. OPLS/2020 force field for unsaturated hydrocarbons, alcohols, and ethers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 128, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabpour, A.; Abbasi, M. Thermodynamic Properties of Monatomic, Diatomic, and Polyatomic Gaseous Natural Refrigerants: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Heat Mass Transf. Res. 2021, 8, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

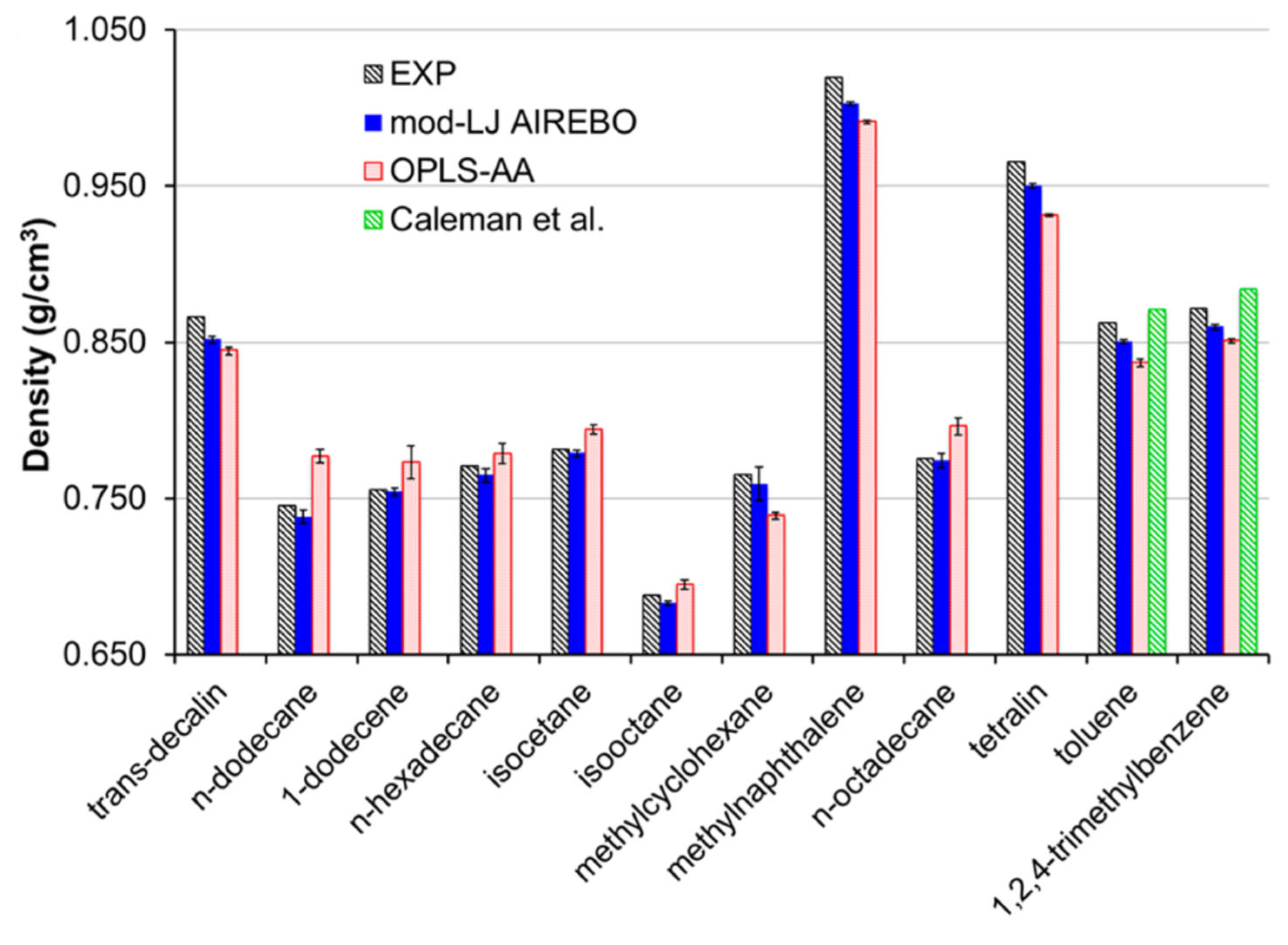

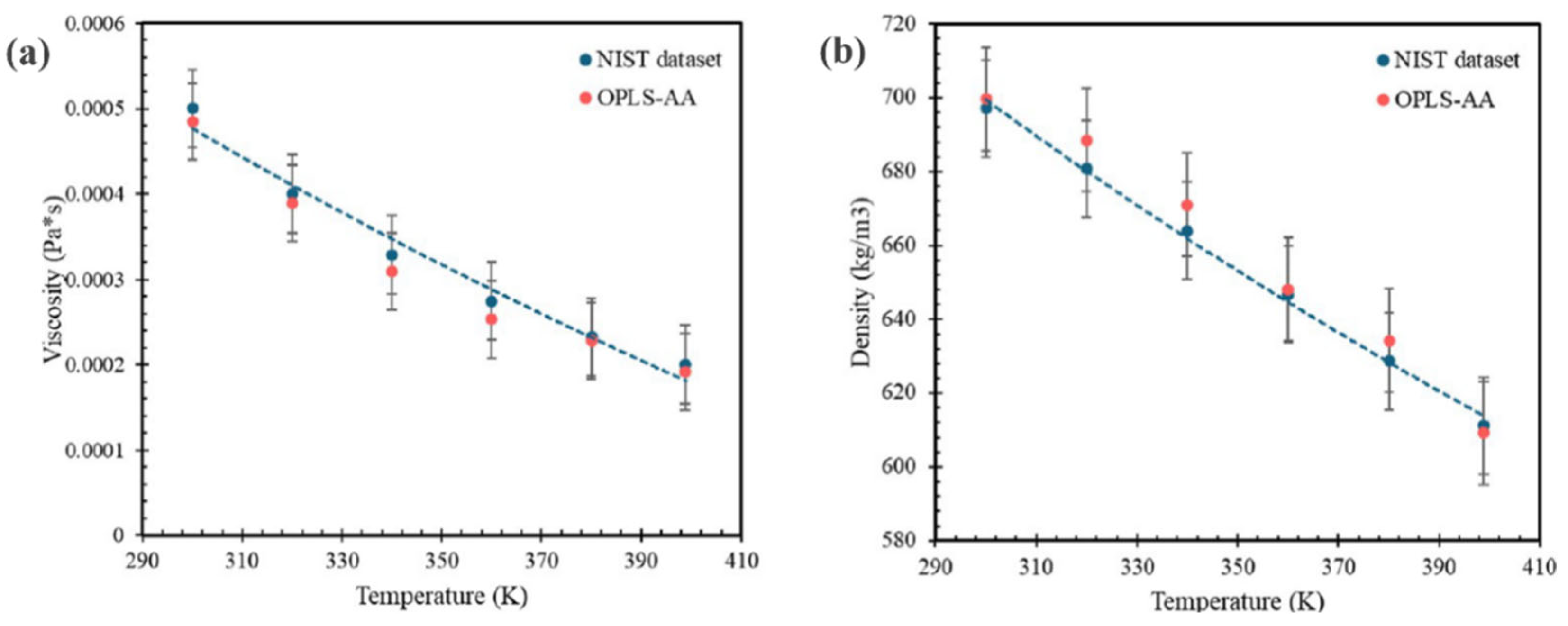

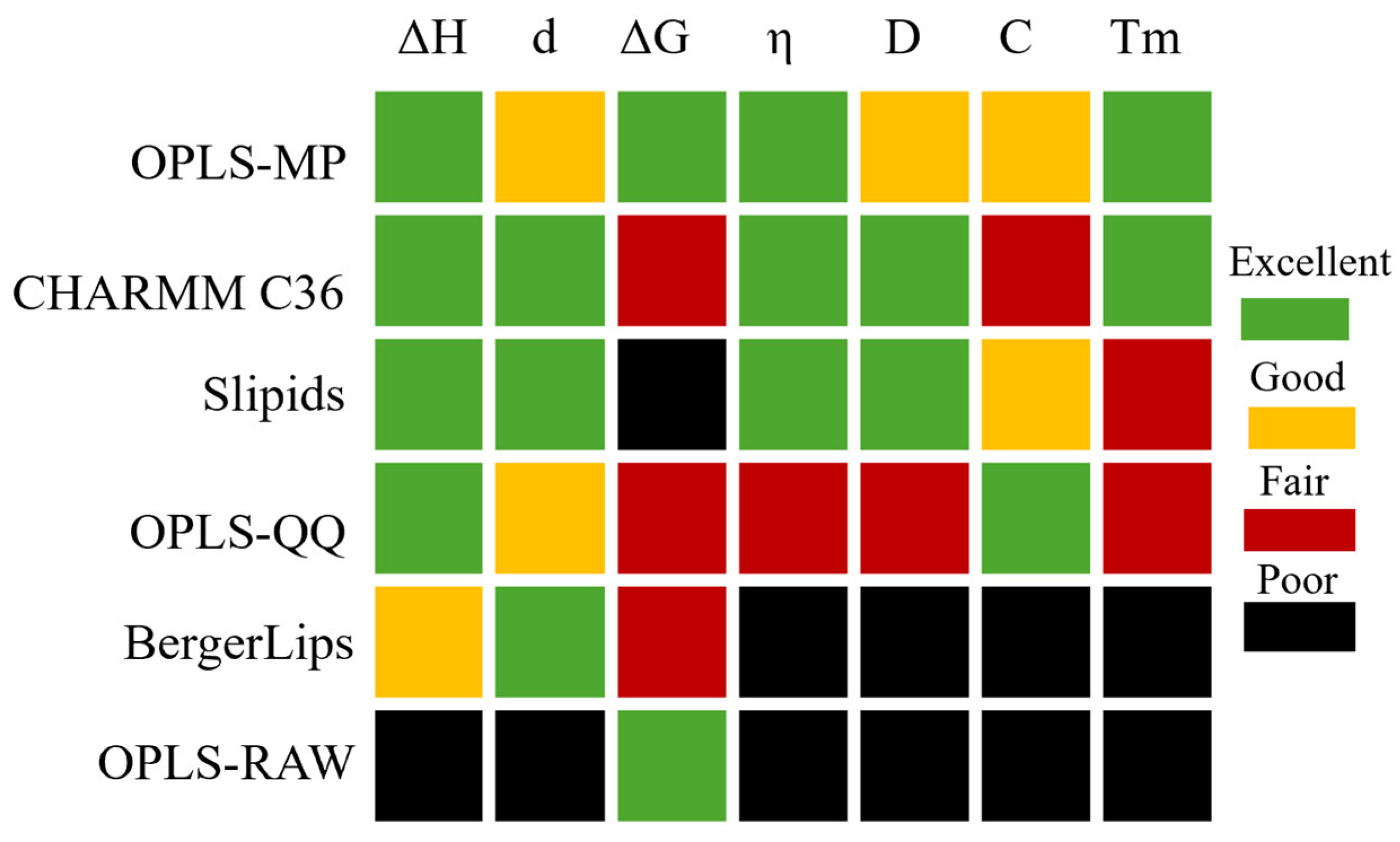

- Morrow, B.H.; Harrison, J.A. Evaluating the ability of selected force fields to simulate hydrocarbons as a function of temperature and pressure using molecular dynamics. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 3742–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Ren, P.; Fried, J. The COMPASS force field: Parameterization and validation for phosphazenes. Comput. Theor. Polym. Sci. 1998, 8, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, R.; Saha, K.; Subramanian, K. Molecular dynamics simulation of the transport and structural properties for methanol-octane blends at engine-relevant conditions. Int. J. Green Energy 2025, 60, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

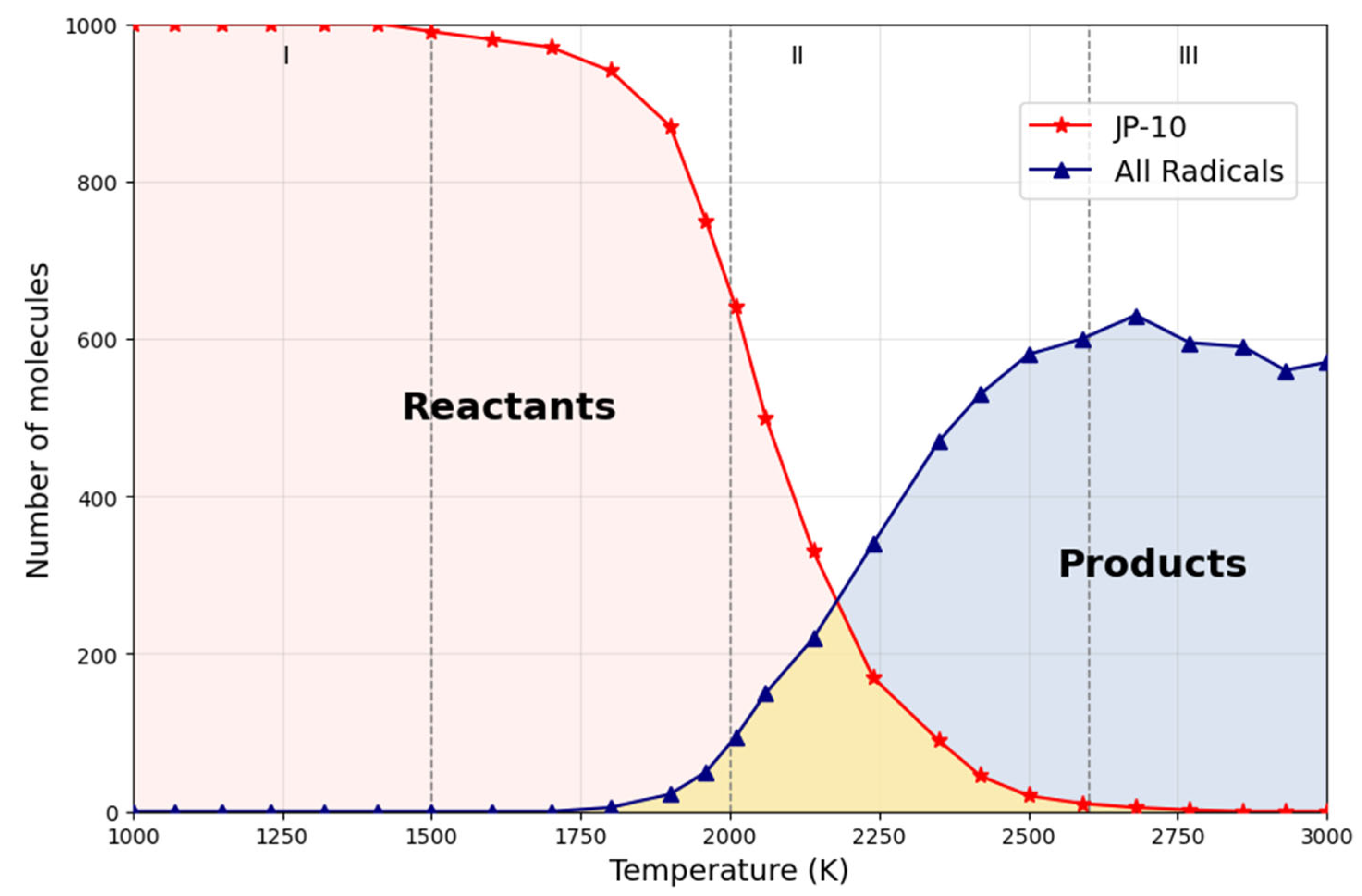

- Chenoweth, K.; Van Duin, A.C.; Dasgupta, S.; Goddard Iii, W.A. Initiation mechanisms and kinetics of pyrolysis and combustion of JP-10 hydrocarbon jet fuel. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.-D.; Wang, J.-B.; Li, J.-Q.; Tan, N.-X.; Li, X.-Y. Reactive molecular dynamics simulation and chemical kinetic modeling of pyrolysis and combustion of n-dodecane. Combust. Flame 2011, 158, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, M.; Ren, C.; Guo, L. ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulations of thermal reactivity of various fuels in pyrolysis and combustion. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 11707–11739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.-R.; Van Duin, A.C.; Thompson, A.P. Development of a ReaxFF reactive force field for ammonium nitrate and application to shock compression and thermal decomposition. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zybin, S.V.; Guo, J.; Van Duin, A.C.; Goddard, W.A., III. Reactive dynamics study of hypergolic bipropellants: Monomethylhydrazine and dinitrogen tetroxide. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 14136–14145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Li, P.; Si, T.; Guo, X. ReaxFF simulations of the synergistic effect mechanisms during co-pyrolysis of coal and polyethylene/polystyrene. Energy 2021, 218, 119553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojwang, J.; Van Santen, R.; Kramer, G.J.; Van Duin, A.C.; Goddard, W.A. Predictions of melting, crystallization, and local atomic arrangements of aluminum clusters using a reactive force field. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 129, 244506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Choi, S.-H.; Van Duin, A.C. Molecular dynamics simulations of stability of metal–organic frameworks against H2O using the ReaxFF reactive force field. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 5713–5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; He, Q.; Xiao, B.; Zhai, D.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Goddard, W.A., III. Detailed Reaction Kinetics for Hydrocarbon Fuels: The Development and Application of the ReaxFFCHO-S22 Force Field for C/H/O Systems with Enhanced Accuracy. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 5065–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Song, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, F.-Q.; Xu, S.-Y.; Ju, X.-H. Reactive molecular dynamics simulations of multicomponent models for RP-3 jet fuel in combustion at supercritical conditions: A comprehensive mechanism study. Chem. Phys. 2023, 573, 112008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, H.; Zhu, Q.; Ren, H.; Li, X. Soot formation of n-decane pyrolysis: A mechanistic view from ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 760, 137983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liang, J.; He, R.; Li, X.; Zheng, M.; Ren, C.; An, G.; Xu, X.; Zheng, Z. Overall mechanism of JP-10 pyrolysis unraveled by large-scale reactive molecular dynamics simulation. Combust. Flame 2022, 237, 111865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Han, Y. Recent ReaxFF MD studies on pyrolysis and combustion mechanisms of aviation/aerospace fuels and energetic additives. Energy Adv. 2023, 2, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

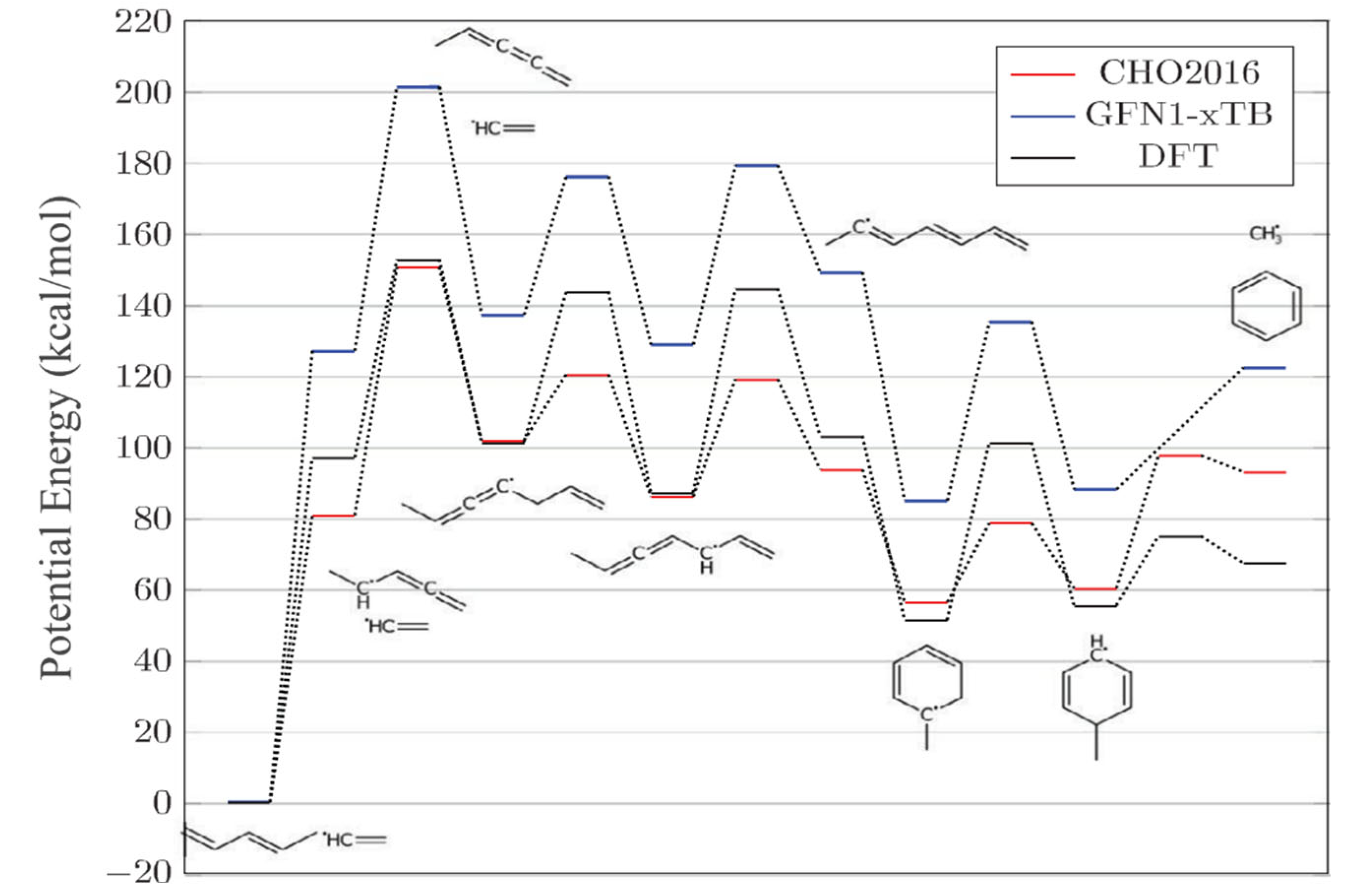

- Schmalz, F.; Kopp, W.A.; Goudeli, E.; Leonhard, K. Reaction path identification and validation from molecular dynamics simulations of hydrocarbon pyrolysis. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 2024, 56, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Li, X.; Guo, L. Algorithms of GPU-enabled reactive force field (ReaxFF) molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2013, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.; Yang, M.; Gao, Y.; Cheng, L.; Ren, H. Molecular dynamics simulations coupled with machine learning for investigating thermophysical properties of binary surrogate aviation kerosene. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 424, 127170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnamoun, A.; Kaymak, M.C.; Manathunga, M.; Götz, A.W.; Van Duin, A.C.; Merz Jr, K.M.; Aktulga, H.M. ReaxFF/AMBER—A framework for hybrid reactive/nonreactive force field molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16, 7645–7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.C.; Silva, G.M.; Tavares, F.W.; Fleming, F.P.; Horta, B.A. Are all-atom any better than united-atom force fields for the description of liquid properties of alkanes? 2. A systematic study considering different chain lengths. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 354, 118829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference Documentation | Technology | Blending Ratio | Feedstock | MSP (USD/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASTM D7566 Annex 1 | FT-SPK | 50% | Biomass, coal, natural gas, | 2.08 [32] |

| ASTM D7566 Annex 2 | HEFA-SPK | 50% | Bio-oils, animal fat, recycled oil | 1.12 [32] |

| ASTM D7566 Annex 3 | SIP | 10% | Biomass used for sugar production | 3.99 [33] |

| ASTM D7566 Annex 4 | FT-SPK/A | 50% | Biomass, natural gas, coal and sawdust, | 2.08 [32] |

| ASTM D7566 Annex 5 | ATJ-SPK | 50% | Biomass from ethanol or isobutanol production | 1.69 [32] |

| ASTM D7566 Annex 6 | CHJ | 50% | Triglycerides such as soybean, carinata, tung, jatropha, and camelina oil | 1.30 [32] |

| ASTM D7566 Annex 7 | HC-HEFA-SPK | 10% | Algae | 1.12 [33] |

| ASTM D7566 A8 | ATJ-SKA | 50% | Alcohol from biomass | 1.7–2.5 & |

| ASTM D1655 | Co-processing | 5% | Fats, oils, greases from petroleum refining | 1.00–1.80 & |

| ASTM D7566 | PtL or e-Fuels | Up to 50% | CO2 (captured) with renewable electricity | 2.7–4.02 [34] |

| Fuel | (H/C)/M0.1 | Density (g/cm3) | D (Exp − Fit) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref [51] * | Fitted # | |||

| Decalin | 1.10 | 0.880 | 0.877 | 0.003 |

| Fuel 1 | 1.14 | 0.845 | 0.852 | −0.007 |

| Fuel 2 | 1.16 | 0.835 | 0.839 | −0.004 |

| Fuel 3 | 1.18 | 0.820 | 0.824 | −0.004 |

| JP-8 | 1.15 | 0.810 | 0.846 | −0.036 |

| JP-7 | 1.25 | 0.805 | 0.784 | 0.021 |

| ECH | 1.24 | 0.790 | 0.790 | 0.0 |

| Fuel 4 | 1.24 | 0.790 | 0.792 | −0.002 |

| Fuel 5 | 1.27 | 0.785 | 0.772 | 0.013 |

| n-paraffin (C9-C13) | 1.28 | 0.760 | 0.766 | −0.006 |

| 1.29 | 0.750 | 0.76 | −0.010 | |

| 1.32 | 0.742 | 0.744 | −0.002 | |

| 1.34 | 0.732 | 0.732 | 0.0 | |

| 1.38 | 0.720 | 0.705 | 0.015 | |

| Fuel | (H/C)/M0.5 | Viscosity (mPa·s) | D (Exp − Fit) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref. [51] * | Fitted # | |||

| Decalin | 0.154 | 2.5 | 2.47 | 0.03 |

| Fuel 3 | 0.153 | 2.15 | 2.5 | −0.35 |

| Fuel 2 | 0.154 | 2.05 | 2.47 | −0.42 |

| Fuel 1 | 0.160 | 1.87 | 2.23 | −0.36 |

| C13 | 0.158 | 1.82 | 2.32 | −0.50 |

| C12 | 0.165 | 1.58 | 2.02 | −0.44 |

| Fuel 5 | 0.167 | 1.50 | 1.97 | −0.47 |

| Fuel 4 | 0.169 | 1.42 | 1.9 | −0.48 |

| C11 | 0.174 | 1.20 | 1.72 | −0.52 |

| C10 | 0.184 | 0.95 | 1.39 | −0.44 |

| ECH | 0.188 | 0.85 | 1.28 | −0.43 |

| C9 | 0.196 | 0.75 | 1.09 | −0.34 |

| Fuel | Typical Energy Content | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravimetric | Volumetric | |||

| MJ/kg | Btu/lb | MJ/L | Btu/gal | |

| Aviation Gasoline Jet Fuel | 43.71 | 18,800 | 31.00 | 112,500 |

| Wide-cut | 43.54 | 18,720 | 33.18 | 119,000 |

| Kerosine | 43.28 | 18,610 | 35.06 | 125,800 |

| Fuel | (H/C) | Net Heating Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Energy (MJ/kg) | Energy Density (MJ/L) | ||

| Decalin | 1.8 | 42.65 | 37.5 |

| Fuel 1 | 1.89 | 42.75 | 36.2 |

| Fuel 2 | 1.94 | 43.00 | 36.0 |

| Fuel 3 | 1.97 | 43.20 | 35.5 |

| ECH | 2.00 | 43.50 | 34.2 |

| Fuel 4 | 2.075 | 43.65 | 35.3 |

| Fuel 5 | 2.10 | 43.70 | 34.7 |

| JP-8 | 1.91 | 43.25 | 35.1 |

| JP-7 | 2.08 | 43.48 | 34.4 |

| n-paraffin (C9–C13) | 2.15 | 44.10 | 33.4 |

| 2.17 | 44.15 | 33.0 | |

| 2.18 | 44.20 | 32.7 | |

| 2.21 | 44.30 | 32.3 | |

| 2.23 | 44.40 | 31.8 | |

| Fuel | (H/C)/M2 * | Flash Point (°C) | D (Exp − Fit) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref. [51] * | Fitted # | |||

| C13 | 0.000063 | 79.0 | 75.84 | 3.16 |

| Fuel 2 | 0.000078 | 75.0 | 66.43 | 8.57 |

| C12 | 0.000077 | 74.0 | 67.04 | 6.96 |

| Fuel 3 | 0.00007 | 68.0 | 70.56 | −2.56 |

| Fuel 5 | 0.00008 | 68.0 | 65.21 | 2.79 |

| C11 | 0.00009 | 65.5 | 59.00 | 6.50 |

| JP-7 | 0.000072 | 60.5 | 69.35 | −8.85 |

| Decalin | 0.000093 | 56.0 | 57.13 | −1.13 |

| Fuel 1 | 0.00009 | 55.0 | 59.00 | −4.00 |

| JP-8 | 0.000085 | 52.5 | 61.9 | −9.40 |

| C10 | 0.00011 | 45.0 | 46.57 | −1.57 |

| Fuel 4 | 0.00009 | 40.0 | 59.00 | −19.00 |

| C9 | 0.000136 | 32.0 | 30.44 | 1.56 |

| ECH | 0.000159 | 21.0 | 16.23 | 4.77 |

| Software | Hydrocarbon/SAF Focus | Force-Field Supported | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS (10 September 2025) | Hydrocarbons, SAF surrogates, reactive simulations of large systems | OPLS-AA, ReaxFF, COMPASS, CHARMM, AMBER | [89,90] |

| GROMACS (2025.4) | Liquid hydrocarbons, thermodynamic studies, mixture properties | OPLS-AA, GROMOS, AMBER, CHARMM | [91,92] |

| Materials Studio (2024) | Commercial MD with GUI, fuel molecule modeling, property prediction | COMPASS, PCFF, OPLS-AA, ReaxFF | [93] |

| CHARMM (c47b2, 2024) | Hydrocarbon–interface systems, structural MD | CHARMM, OPLS-AA, AMBER | [94] |

| AMBER (AmberTools25 & Amber24) | Biomolecules, some hydrocarbon with QM/MM; reactive MD (ReaxFF/AMBER) | AMBER, OPLS-AA | [95] |

| Quantum ESPRESSO (7.3) | Ab initio MD for reaction pathways, adsorption | Plane-Wave Pseudopotentials | [96] |

| CP2K (2024.1) | Hybrid QM/MM for hydrocarbon reactivity, MD + DFT | Hybrid Gaussian and Plane-Wave | [97] |

| Temperature (K) | OPLS-AA Density (g cm−3) | TraPPE-UA Density (g cm−3) | Δρ (g cm−3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 525 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.000 |

| 550 | 0.020 | 0.030 | −0.010 |

| 575 | 0.040 | 0.050 | −0.010 |

| 600 | 0.055 | 0.065 | −0.010 |

| 612 | 0.060 | 0.070 | −0.010 |

| 626 | 0.072 | 0.090 | −0.018 |

| 635 | 0.082 | 0.100 | −0.018 |

| 634 | 0.634 | 0.620 | +0.014 |

| 626 | 0.653 | 0.640 | +0.013 |

| 610 | 0.690 | 0.670 | +0.020 |

| 600 | 0.715 | 0.700 | +0.015 |

| 575 | 0.755 | 0.740 | +0.015 |

| 550 | 0.790 | 0.780 | +0.010 |

| 526 | 0.820 | 0.800 | +0.020 |

| Paper Name | Year | Key Findings | Journal Name | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular dynamics simulation study on the dynamic viscosity and thermal conductivity of high-energy hydrocarbon fuel Al/JP-10 | 2025 | OPLS force field used for precisely modeling the thermal behavior of high-energy hydrocarbon fuels under elevated temperature conditions. | Fuel | [101] |

| Machine Learning-Based Molecular Dynamics Studies on Predicting Thermophysical Properties of Ethanol–Octane Blends | 2024 | MD and ML approaches are applied to estimate thermophysical properties of ethanol octane blends. The OPLS-AA force field was applied to precisely predict molecular interactions. | Energy Fuels | [137] |

| Molecular dynamics investigation on structural and interfacial characteristics of aerosol particles containing mixed organic components | 2024 | MD is used to investigate the interfacial and structural properties of mixed organic compounds. | Atmospheric Environment | [141] |

| System-Specific Parameter Optimization for Non-Polarizable and Polarizable Force Fields | 2023 | Introduced a tool for system-specific parameterization of OPLS-AA and polarizable force fields enhancing simulation accuracy for complex systems. | Journal of chemical theory and computation vol. | [125] |

| OPLS/2020 Force Field for Unsaturated Hydrocarbons, Alcohols, and Ethers | 2023 | OPLS-AA/2020, an advancement in OPLS force field, is utilized to improve the accuracy for organic and biomolecular simulations. | The Journal of Physical Chemistry B | [142] |

| Refinement of the OPLS Force Field for Thermodynamics and Dynamics of Liquid Alkanes | 2022 | OPLS-AA parameters are used for better replication of liquid-phase properties of alkanes, including densities and heats of vaporization. | The Journal of Physical Chemistry B | [130] |

| Thermodynamic Properties of Monatomic, Diatomic, and Polyatomic Gaseous Natural Refrigerants: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation | 2021 | OPLS-AA force fields are employed to simulate the behavior of polyatomic hydrocarbon refrigerants such as methane and ethane gas | Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer Research | [143] |

| Evaluating the Ability of Selected Force Fields to Simulate Hydrocarbons as a Function of Temperature and Pressure Using Molecular Dynamics | 2021 | OPLS-AA and ReaxFF force fields are used to simulate pure hydrocarbon fluids at variant temperature conditions. | Energy & Fuels | [144] |

| Molecules | Expt (Hv) (kcal/mol) | Cal. (Hv) (kcal/mol) | Hv% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclohexane | 7.96 | 7.99 | 0.4 |

| Ethane | 3.51 | 3.25 | −7.4 |

| Isopentane | 6.01 | 6.12 | 1.8 |

| Propane | 4.49 | 4.3 | −4.2 |

| 2-methylheptane | 9.49 | 9.36 | −1.4 |

| 2,5-dimethylhexane | 8.93 | 8.82 | −1.2 |

| 2,2-dimethylhexane | 8.93 | 8.77 | −1.8 |

| 2,2,4-trimethylpentane | 8.42 | 8.24 | −2.1 |

| Butene | 5.28 | 5.39 | 2.1 |

| Ethylene | 3.23 | 3.21 | −0.6 |

| Propene | 4.42 | 4.41 | −0.2 |

| Benzene | 8.09 | 8.18 | 1.1 |

| Toluene | 9.09 | 9.08 | −0.1 |

| Ethanol | 10.20 | 10.36 | 1.6 |

| Methanol | 9.01 | 8.98 | −0.3 |

| Phenol | 13.36 | 13.29 | −0.5 |

| Property | COMPASS (%) * | TraPPE (%) * | OPLS (%) * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol Density | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Octane Density | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1 |

| Methanol Viscosity | 4.2 | 5.3 | 6.8 |

| Octane Viscosity | 3.4 | 6.1 | 8.5 |

| 1000/T (K−1) * | ln(k) (Exp) * | ln(k) (Fit) | Residual (Exp − Fit) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.285 | −2.50 | −2.49 | −0.01 |

| 0.306 | −2.85 | −2.88 | +0.03 |

| 0.332 | −3.25 | −3.36 | +0.11 |

| 0.363 | −3.90 | −3.91 | +0.01 |

| 0.400 | −4.70 | −4.57 | −0.13 |

| Author and Year | Fuel/System | Method | Main Focus | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liao et al., 2025 | Binary surrogate aviation kerosene | MD + ML | Thermophysical properties | MD + ML accurately predicted mixture density/viscosity; reduced computational cost. | [162] |

| Shateri et al., 2025 | Ethanol–octane blends | ML + MD | Thermophysical property prediction | ML captured MD-derived displacements/velocities with less than 2.5% error. | [137] |

| Kashyap et al., 2025 | Methanol–octane fuel blends | Classical MD | Transport and structure | MD showed that viscosity and diffusivity depend strongly on temperature and blend composition; micro-structural ordering observed. | [146] |

| Kapadiya and Adhikari, 2025 | m-Cresol | MD (TraPPE-UA vs. OPLS-AA) | Force-field comparison | OPLS-AA performed better for thermodynamic predictions. | [138] |

| Wen et al., 2025 | Al/JP-10 high-energy fuel | MD | Viscosity and thermal conductivity | Nanoparticles strongly modified transport properties of JP-10. | [101] |

| Schmalz et al., 2024 | Hydrocarbon pyrolysis | Reactive MD (ReaxFF) | Reaction-path identification | MD developed automated pyrolysis pathway mapping. | [160] |

| Wang et al., 2024 | C/H/O fuel systems | ReaxFFCHO-S22 | Force-field development | MD with updated FF improved accuracy for hydrocarbon oxidation; validated vs. experiments. | [155] |

| Kashurin et al., 2024 | Liquid membranes | MD (multi-FF) | Structure and transport | Compared FFs; identified large differences in predicted membrane behavior. | [116] |

| Hu et al., 2024 | Organic compounds | Classical MD | Force-field accuracy testing | MD validated improved reproduction of liquid densities and diffusion using optimized FF parameters. | [125] |

| Zhang et al., 2024 | Organic aerosols | Classical MD | Interfacial and structural properties | Linked molecular composition to the structure of aerosol. | [141] |

| Yu et al., 2023 | RP-3 jet fuel (multi-component) | Reactive MD | High-T combustion | MD provided decomposition mechanism for RP-3 under supercritical conditions. | [156] |

| Chen et al., 2023 | Aviation and aerospace fuels | ReaxFF MD Review | Pyrolysis and combustion | Recent reactive MD studies: bond cleavage, ring opening, radical pathways were summarized for energetic fuels. | [159] |

| Yang et al., 2022 | RP-3 surrogate mixtures | Classical MD | Thermophysical properties | MD predicted composition-dependent density, cp, viscosity, for non-ideal mixture. | [103] |

| Freitas et al., 2022 | Liquid fuels (alkanes) | MD + ML (GP/Generative) | Property surrogate models | MD provided accurate density/PVT curves under different conditions for ML surrogate training. Achieved R2 > 0.99 for density; demonstrated multi-fidelity learning. | [123] |

| Liu et al., 2022 | JP-10 | Large-scale ReaxFF MD | Pyrolysis mechanism | JP-10 decomposition: ring opening → chain growth → PAH precursor formation under engine-like temperatures. | [158] |

| Silva et al., 2022 | Alkanes (chain-length study) | Classical MD | FF performance | Evaluated six FFs for long-chain liquids: UA models—GROMOS in particular reproduced most accurate density, Hvap, surface tension, and viscosity, while some AA FFs showed premature solidification. | [164] |

| Li et al. (2021) | Various fuels | ReaxFF MD | Pyrolysis and combustion | MD evaluated thermal reactivity of different fuels. | [149] |

| Wang et al., 2021 | JP-10 (sub/supercritical) | Classical MD | Phase behavior near critical region | MD revealed micro-inhomogeneities and phase-transition behavior under supercritical conditions. | [104] |

| Morrow and Harrison (2021) | Hydrocarbons | Classical MD | Property predictions | Benchmarked common FFs for hydrocarbon modeling. | [144] |

| Liu et al., 2020 | n-Decane | Reactive MD | Soot precursor formation | PAH growth pathways under pyrolysis conditions were identified. | [157] |

| Bratek et al., 2020 | n-Pentadecane | MD using biomolecular FFs | Condensed-phase properties | FF selection strongly influenced predicted transport properties. | [139] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Batool, F.; Vasilyev, V.; Wang, J.; Wang, F. Evaluating Fuel Properties of SAF Blends: From Component-Based Estimation to Molecular Dynamics. Energies 2025, 18, 6401. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246401

Batool F, Vasilyev V, Wang J, Wang F. Evaluating Fuel Properties of SAF Blends: From Component-Based Estimation to Molecular Dynamics. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6401. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246401

Chicago/Turabian StyleBatool, Fozia, Vladislav Vasilyev, James Wang, and Feng Wang. 2025. "Evaluating Fuel Properties of SAF Blends: From Component-Based Estimation to Molecular Dynamics" Energies 18, no. 24: 6401. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246401

APA StyleBatool, F., Vasilyev, V., Wang, J., & Wang, F. (2025). Evaluating Fuel Properties of SAF Blends: From Component-Based Estimation to Molecular Dynamics. Energies, 18(24), 6401. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246401