Transient Modeling of a Radiantly Integrated TPV–Microreactor System (RITMS) Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

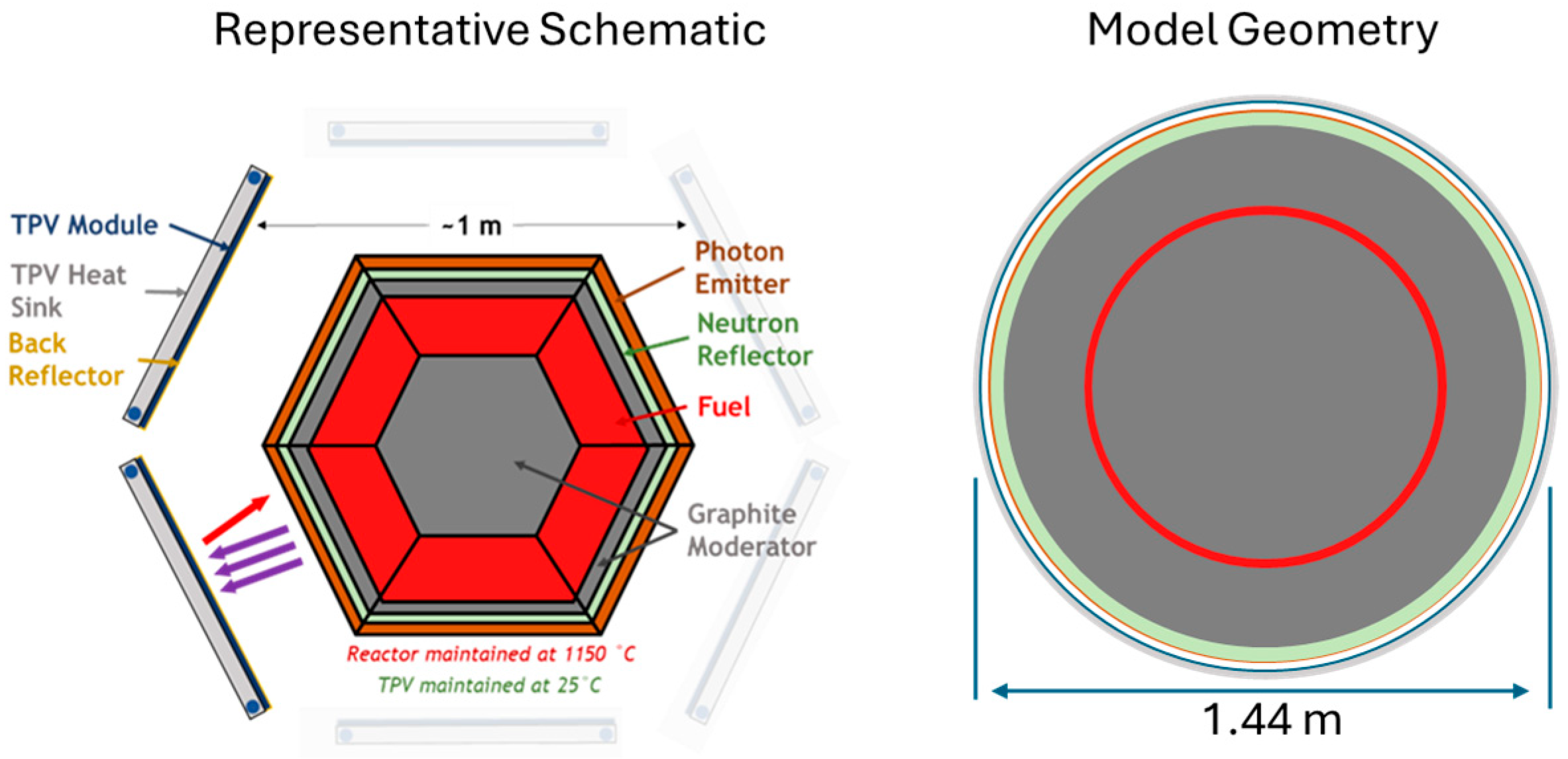

2. Reference Design

3. Codes and Methods

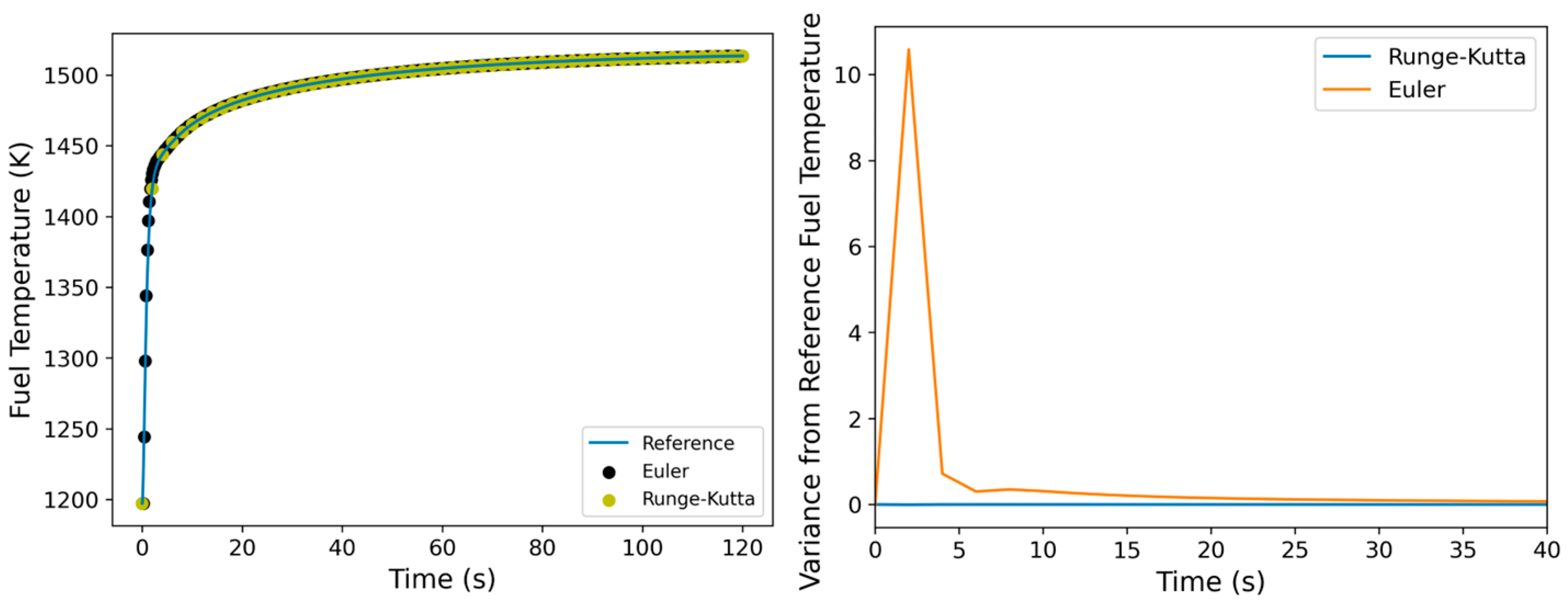

3.1. Solution Method

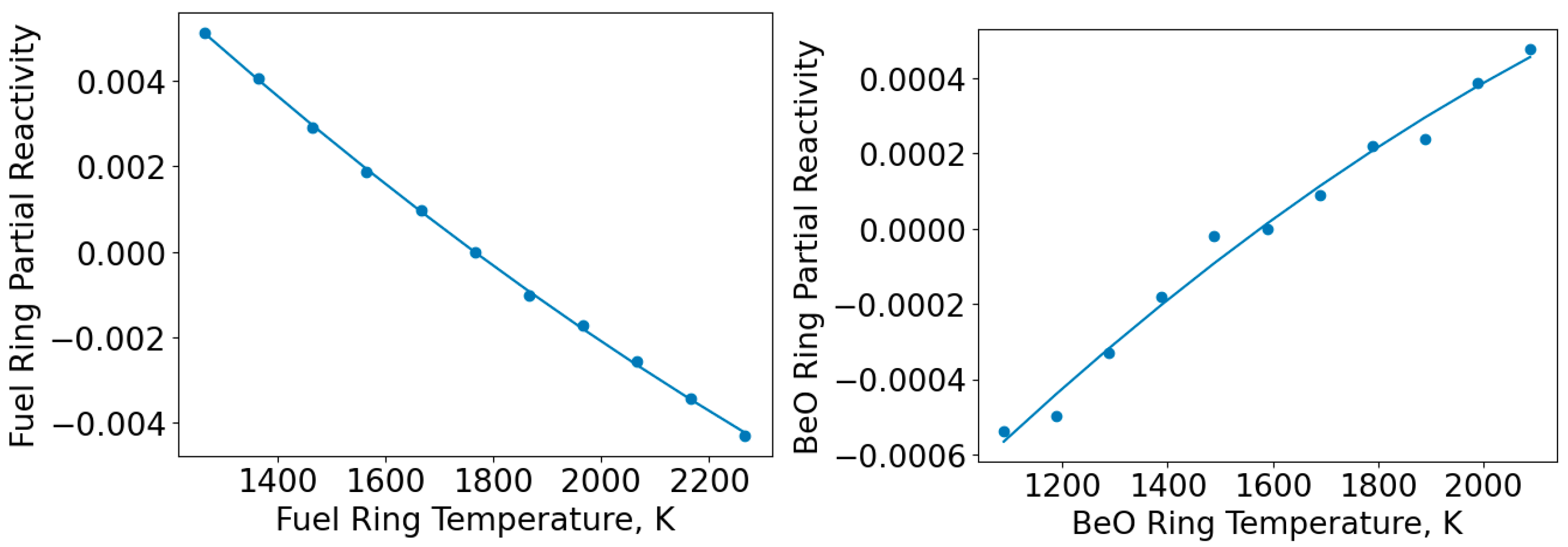

3.2. Neutronic Modeling and Reactivity Feedback

3.3. Power Variance Through Point-Kinetic Equations

3.4. Solid-Ring Transient Conduction

3.5. Reactor Surface Boundary Condition

3.6. TPV Power Balance

3.7. Validation Problems

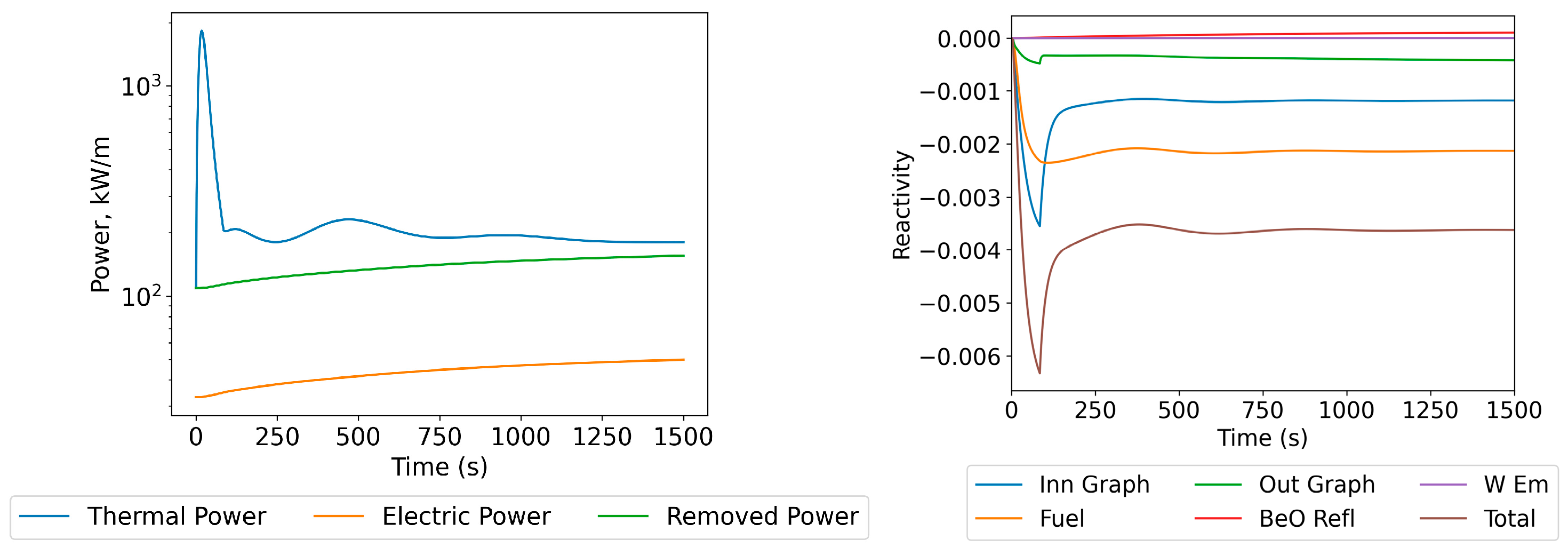

4. Results

4.1. Peripheral Transient Scenarios

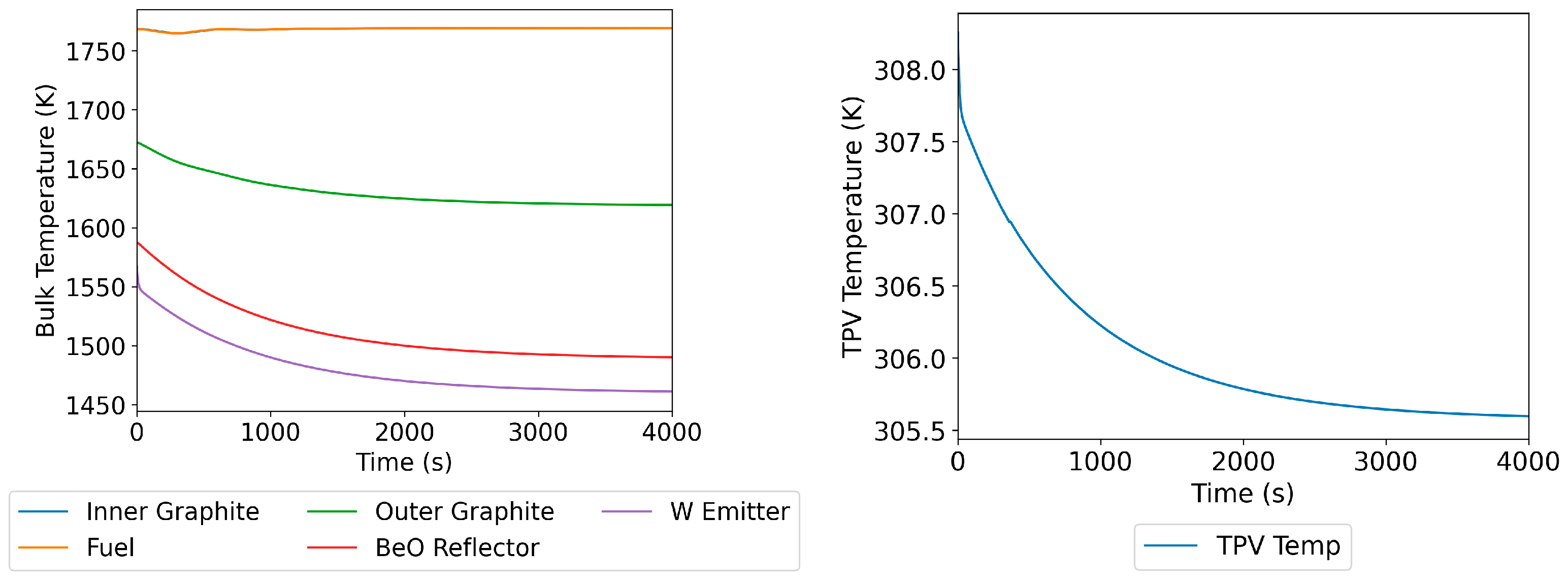

4.1.1. Loss of Vacuum

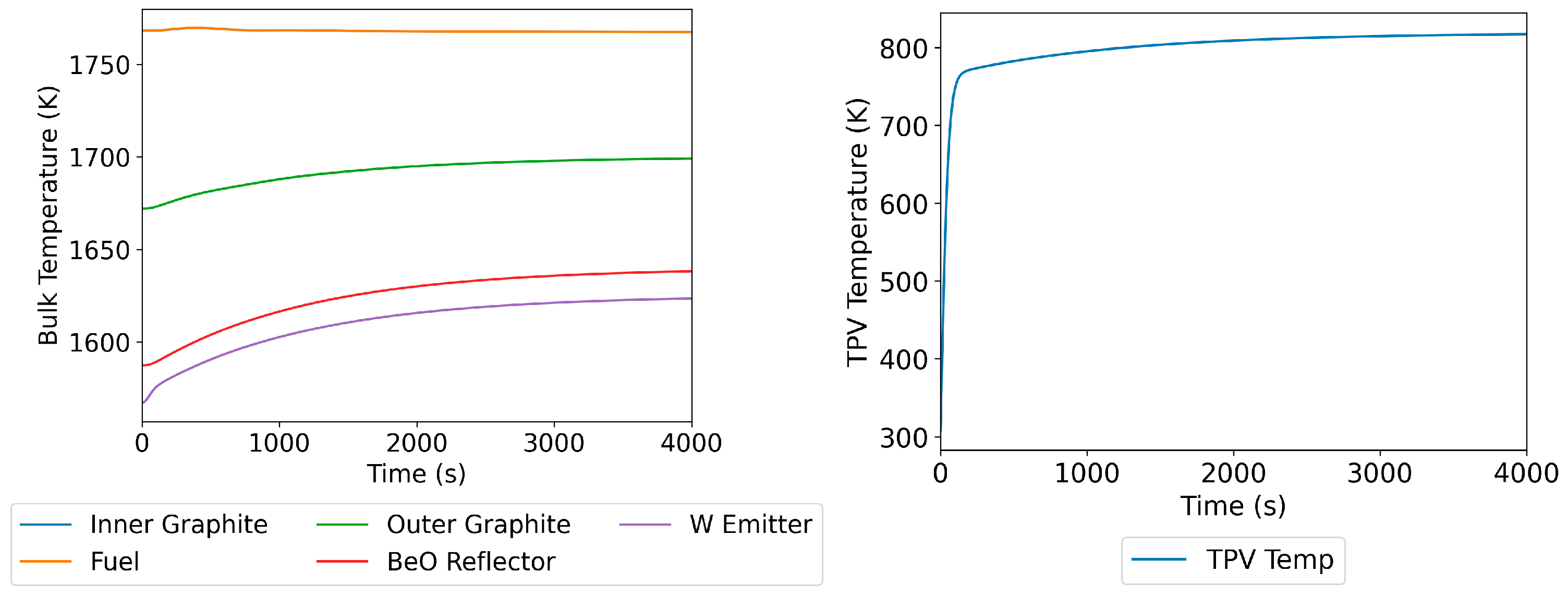

4.1.2. Loss of TPV Coolant Pump

4.2. Core Transient Scenarios

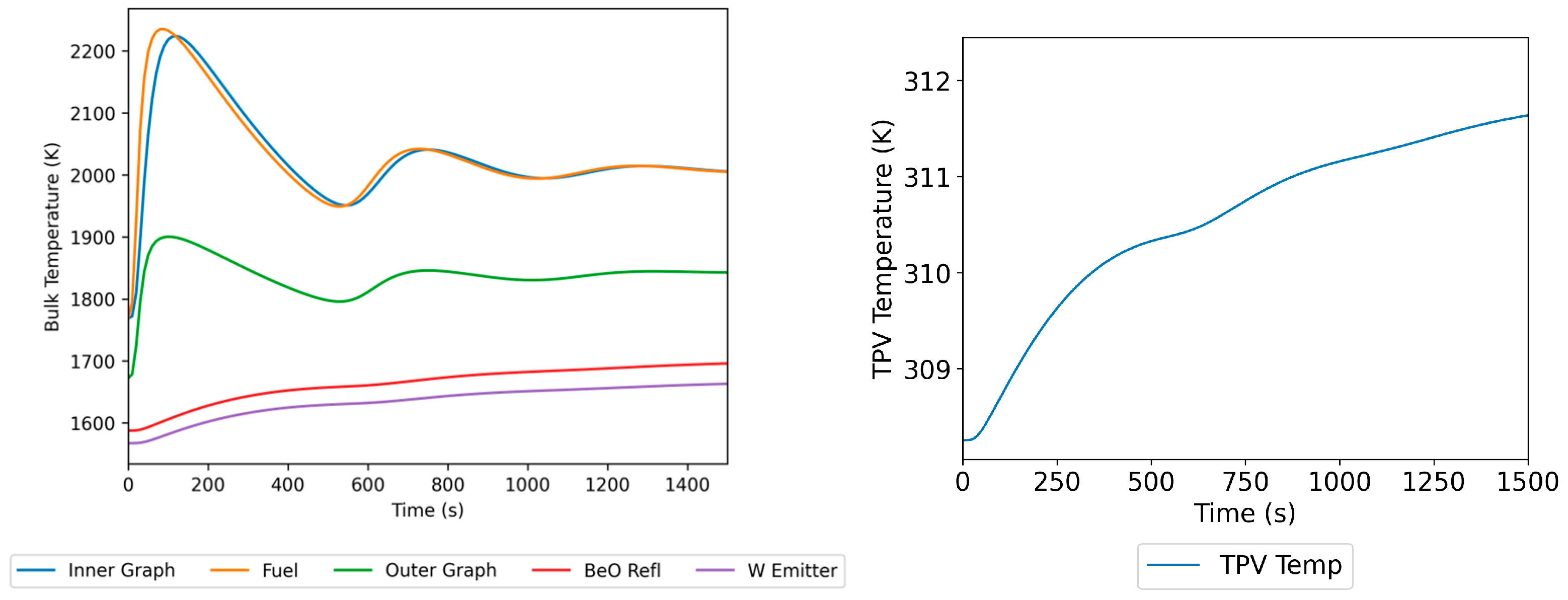

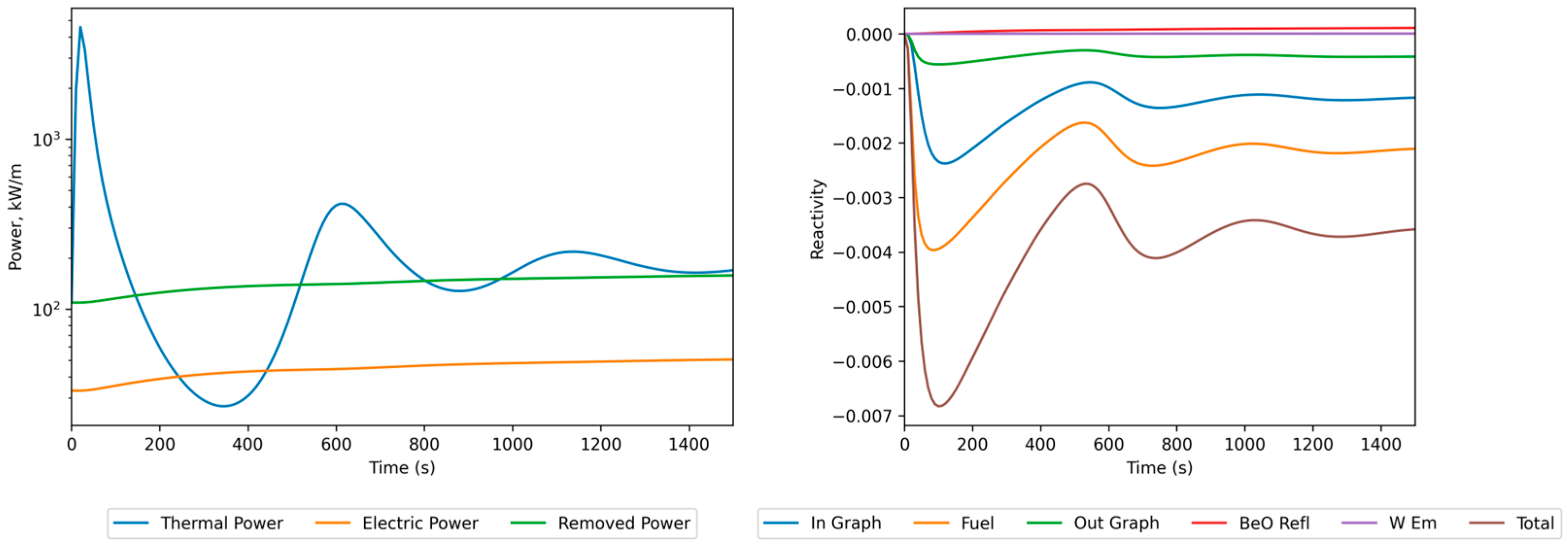

4.2.1. Sub-Prompt Positive Reactivity Insertion

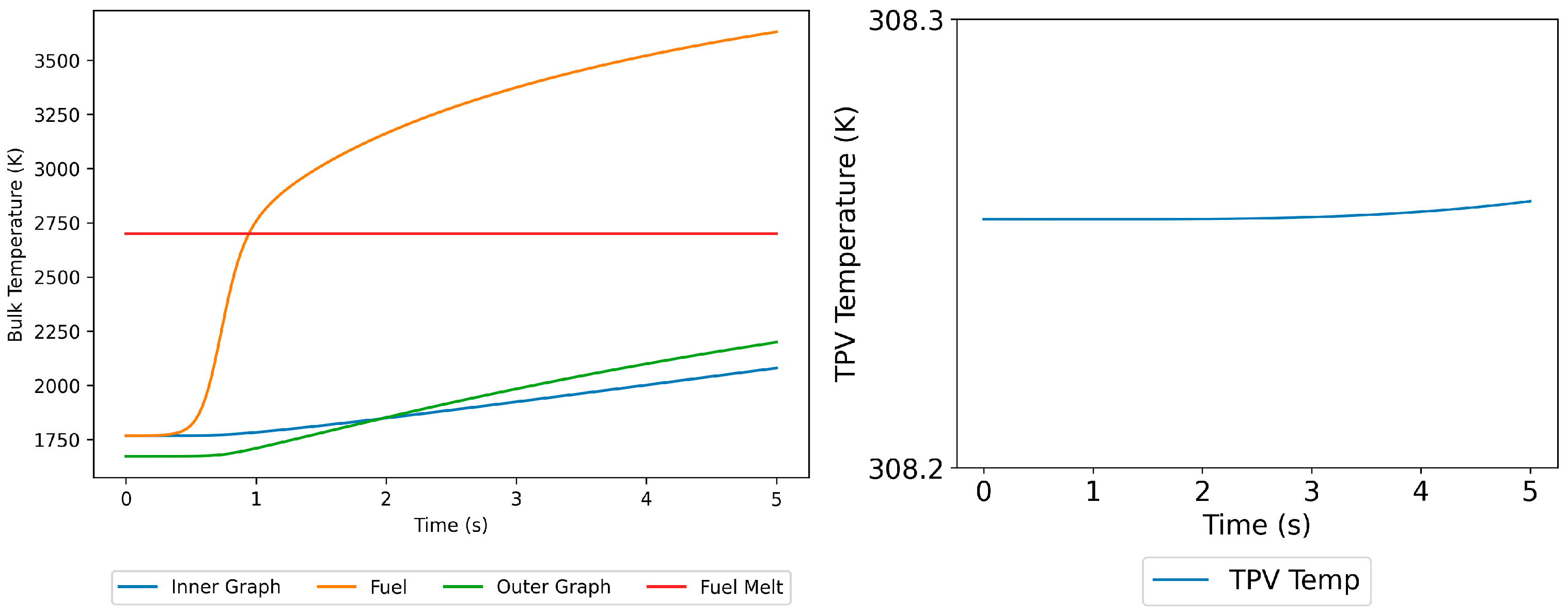

4.2.2. Prompt Positive Reactivity Insertion

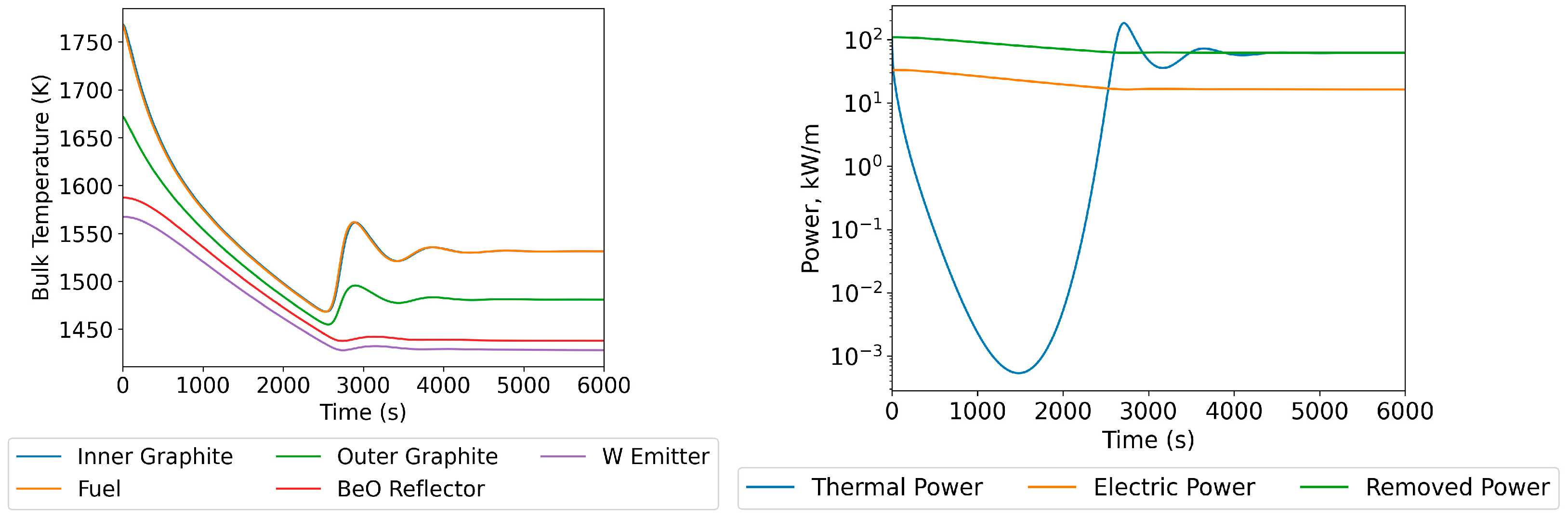

4.2.3. Negative Reactivity Insertion

5. Discussion and Design Response

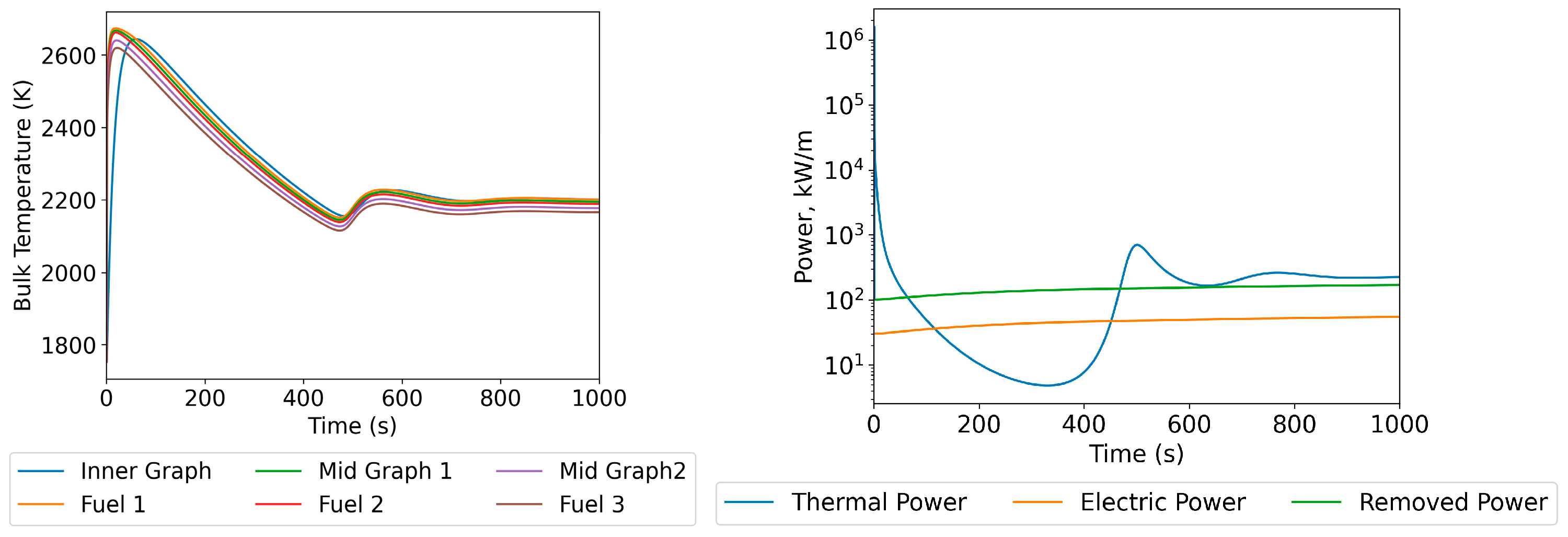

5.1. Adjusting the Number of Fuel Regions

5.2. Active Intervention with Joule Heating

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

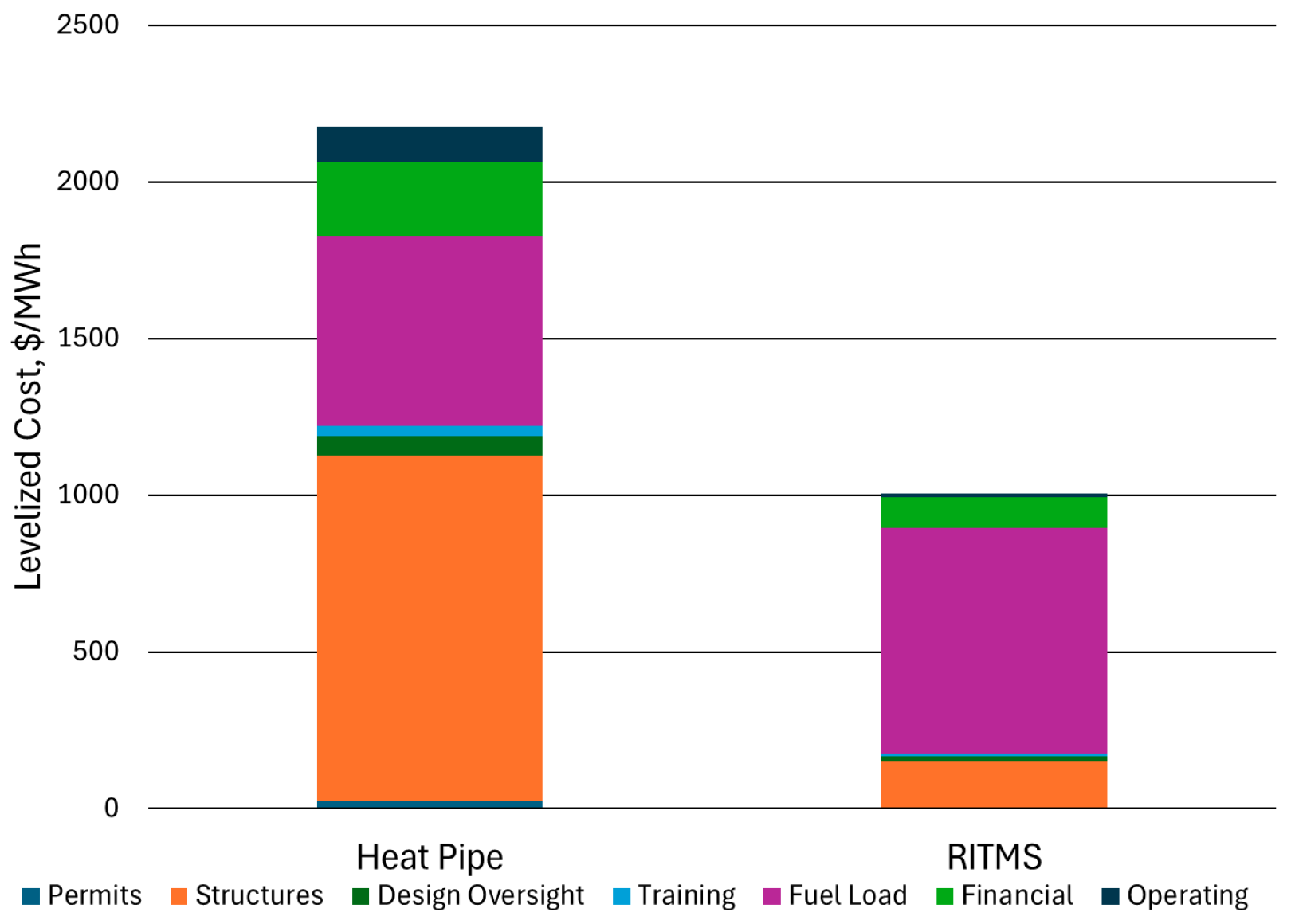

- Kaffezakis, N.; Kotlyar, D. Trade-Off Studies of a Radiantly Integrated TPV-Microreactor System. Energies 2025, 18, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licenses, Certifications, and Approvals for Nuclear Power Plants 10 CFR Part 52 [Online]. 2007. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-10/chapter-I/part-52 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Shimizu, M.; Kohiyama, A.; Yugami, H. Evaluation of thermal stability in spectrally selective few-layer metallo-dielectric structures for solar thermophotovoltaics. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2018, 212, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Jaoude, A.; Arafat, Y.; Foss, A.; Dixon, B. An Economics-by-Design Approach Applied to a Heat Pipe Microreactor Concept; INL: Idaho Falls, ID, USA, 2021.

- Jones, E.; Oliphant, T.; Peterson, P. SciPy: Open Source Scientific Tools for Python. 2001. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/213877848_SciPy_Open_Source_Scientific_Tools_for_Python (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Dormand, J.R.; Prince, P.J. A family of embedded Runge-Kutta formulae. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1980, 6, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, W. Nuclear Reactor Physics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Leppänen, J.; Pusa, M.; Viitanen, T.; Valtavirta, V.; Kaltiaisenaho, T. The Serpent Monte Carlo code: Status, development and applications in 2013. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2015, 82, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, H. Measurements of thermal diffusivities of fine-grained isotropic graphites from room temperature to 2000 by laser flash method. Netsu Sokutei 2000, 17, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.-W.; Tang, Y.-P.; Lu, Z.-M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B. Nuclear graphite for high temperature gas-cooled reactors. New Carbon Mater. 2017, 32, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Hickman, R.R.; Shah, S. Solid Solution Carbides Are the Key Fuels for Future Nuclear Thermal Propulsion; American Nuclear Society: Monterey, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevamurthy, G.; Nelson, A.T. Uranium carbide properties for advanced fuel modeling—A review. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 558, 153145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Zhou, X.; Liu, B. Beryllium oxide utilized in nuclear reactors: Part I: Application history, thermal properties, mechanical properties, corrosion behavior and fabrication methods. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2022, 54, 4393–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceram Research. Beryllium Oxide—Beryllia; AZO Network: Sydney, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, J.A.; Charit, I. Analytical determination of thermal conductivity of W-UO2 and W-UN CERMET nuclear fuels. J. Nucl. Mater. 2012, 427, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolias, P. Analytical expressions for thermophysical properties of solid and liquid tungsten relevant for fusion applications. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2017, 13, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F. The Engineering Properties of Tungsten and Tungsten Alloys; Defense Metals Information Center: North Canton, OH, USA; Battelle Memorial Institute: Aberdeen, MD, USA, 1963; Volume 191. [Google Scholar]

- Levinshtein, M.; Shur, M. Handbook Series on Semiconductor Parameters; World Scientific: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wu, S.; Cao, S.; Cai, Q.; Ye, Q.; Liu, X.; Wul, X. Transient performance of a nanowire-based near-field thermophotovoltaic system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 192, 116918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldasaro, P.; Raynolds, J.E.; Charache, G.; Depoy, D.; Ballinger, C.; Donovan, T.; Borego, J. Thermodynamic analysis of thermophotovoltaic efficiency and power density tradeoffs. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 89, 3319–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, J. Heat Transfer; Mcgraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Cengel, Y.; Ghajar, A. Heat and Mass Transfer: Fundamentals and Applications; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, T.; Clemens, J.; Eades, M.; Pearson, B. Reflector and Control Drum Design for a Nuclear Thermal Rocket. In Proceedings of the Nuclear and Emerging Technologies for Space 2015, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 23–26 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, D.; Bryan, C. High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR); Oakridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2021.

| Ring | Outer Radius, cm | Material | Bulk Temperature, K |

| 1 | Graphite | ||

| 2 | Uranium Carbide | ||

| 3 | Graphite | ||

| 4 | Beryllium Oxide | ||

| 5 | Emitter | ||

| TPV | InGaAs | ||

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

| Efficiency | 30.4% | Thermal Power | 660 kW |

| Unit Length | 8 m | Unit Mass | 26.1 MT |

| Fuel Enrichment | 7% | Maximum Life | 20 yr |

| Levelized Cost | 1040 $/MWh | Capital Cost | $25.5 mil |

| Variable | Description | ODE |

|---|---|---|

| T1 [K] | Center Ring Temperature | |

| T1<i<N [K] | Ring Temperature i > 1 | |

| TN [K] | Emitter Ring Temperature | |

| Tt [K] | TPV Temperature | |

| QTot [W] | Total Fission Power | |

| Ci [W] | Power from Delayed Neutrons | |

| Partial Reactivities |

| Region | |

|---|---|

| Ring 1 (Moderator) | |

| Ring 2 (Fuel) | |

| Ring 3 (Moderator) | |

| Ring 4 (Reflector) | |

| Ring 5 (Emitter) |

| Group | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 3 | 0.0011 | 0.110 |

| 4 | ||

| 5 | 0.0010 | |

| 6 | 0.0003 | |

| Total | 0.0072 | 0.00003 |

| Material | Thermal Conductivity, W/m/K | Heat Capacity, J/kg/K | Density, kg/m3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graphite [9,10,11] | |||

| UC [12] | |||

| BeO [13,14] | |||

| Tungsten [15,16,17] | |||

| InGaAs [18] |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel Mass | 40,000 kg | Fuel Heat Capacity | |

| Moderator Mass | 7000 kg | Moderator Heat Capacity | |

| Fuel TRC | Moderator TRC | ||

| Heat Transfer Coefficient | Initial Power | ||

| Inlet Temperature | Mass Flow | ||

| Initial Fuel Temp | 1200 K | Initial Bulk Fluid Temp | 573 K |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rod Diameter | 5 cm | Rod Initial temperature | |

| Rod Density | Rod Heat Capacity | ||

| Rod Conductivity | Thermal Diffusivity | ||

| Heat Transfer Coefficient | Bulk Temperature |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaffezakis, N.; Kotlyar, D. Transient Modeling of a Radiantly Integrated TPV–Microreactor System (RITMS) Design. Energies 2025, 18, 6361. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236361

Kaffezakis N, Kotlyar D. Transient Modeling of a Radiantly Integrated TPV–Microreactor System (RITMS) Design. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6361. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236361

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaffezakis, Naiki, and Dan Kotlyar. 2025. "Transient Modeling of a Radiantly Integrated TPV–Microreactor System (RITMS) Design" Energies 18, no. 23: 6361. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236361

APA StyleKaffezakis, N., & Kotlyar, D. (2025). Transient Modeling of a Radiantly Integrated TPV–Microreactor System (RITMS) Design. Energies, 18(23), 6361. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236361